Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

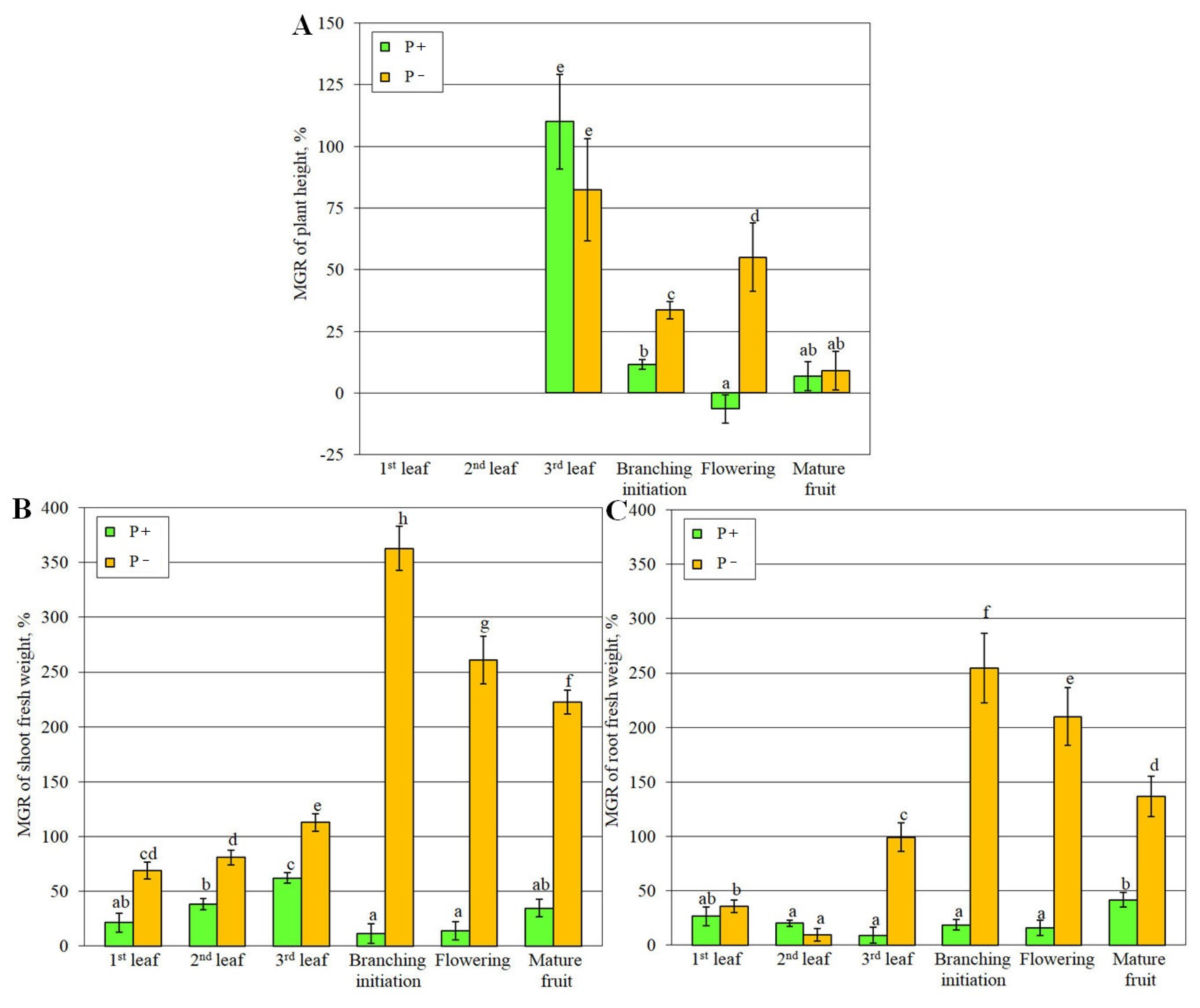

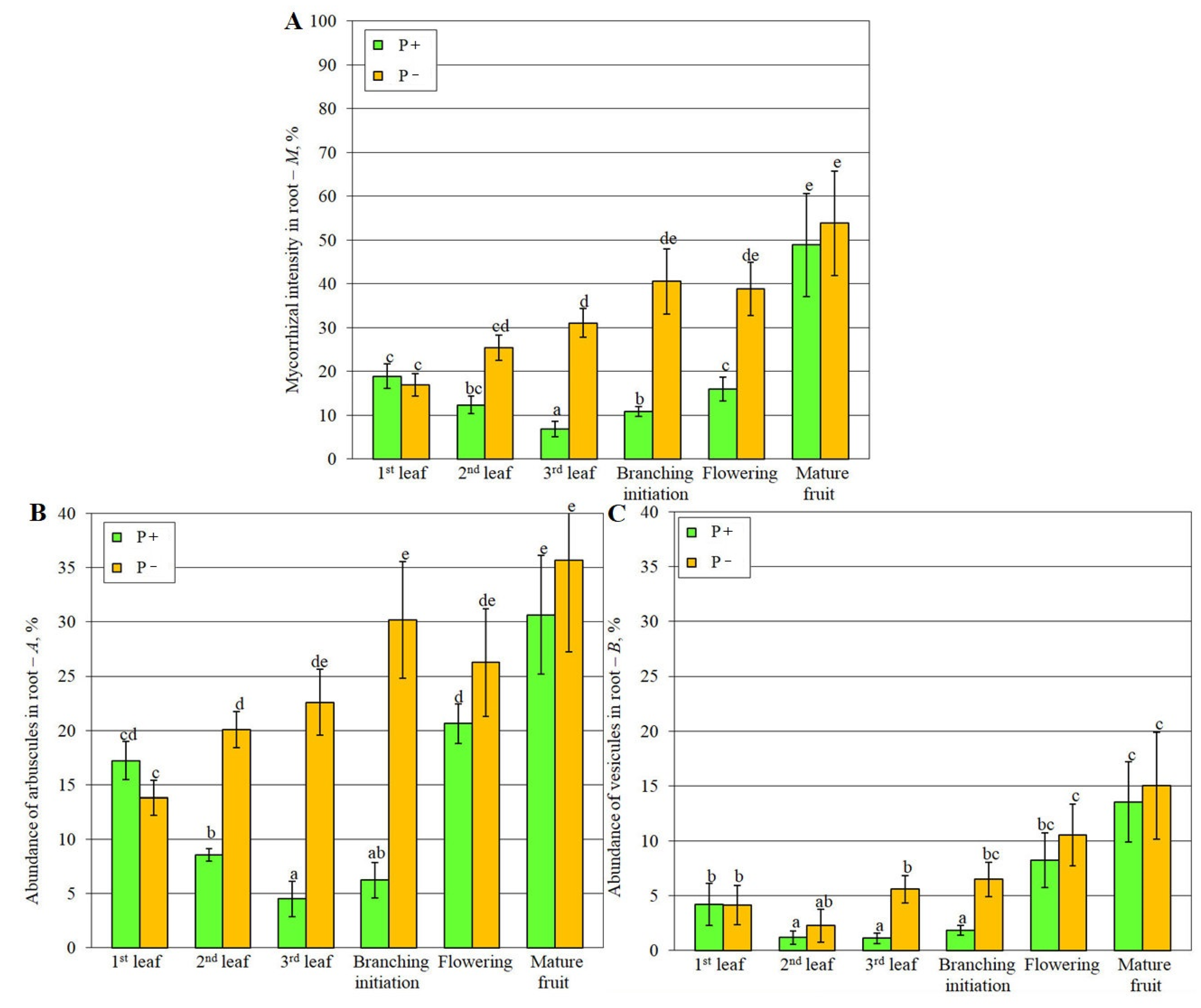

2.1. Medicago lupulina MlS-1 Line Plant Development Under Low and High Phosphorus Levels

2.2. General Characteristics of Metabolic Profiles

2.3. Changes in the Root Metabolome During Plant Development

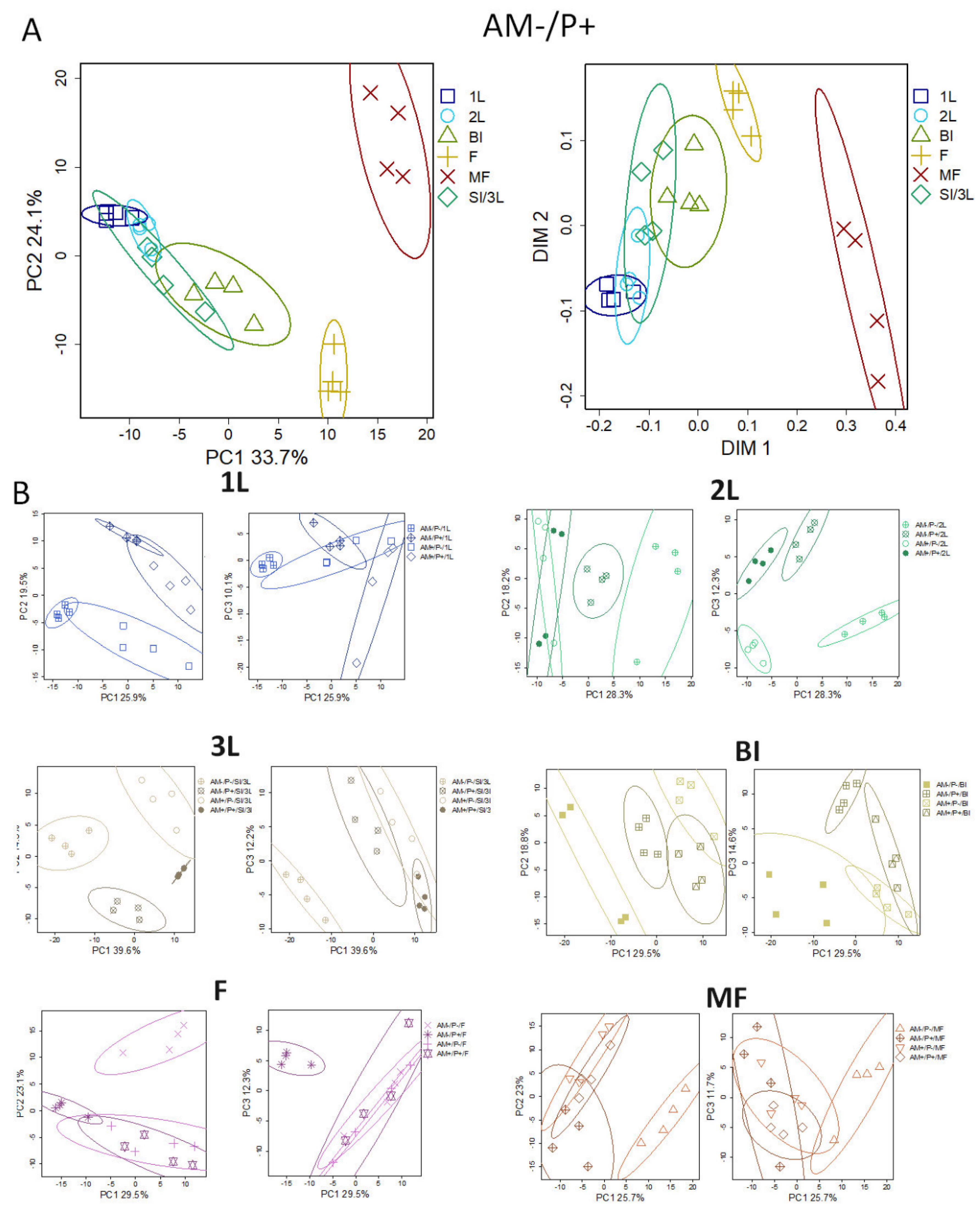

2.4. The effect of Mycorrhization by AM Fungus and Phosphorus on the Metabolic Profile of Roots. Exploratory Analysis

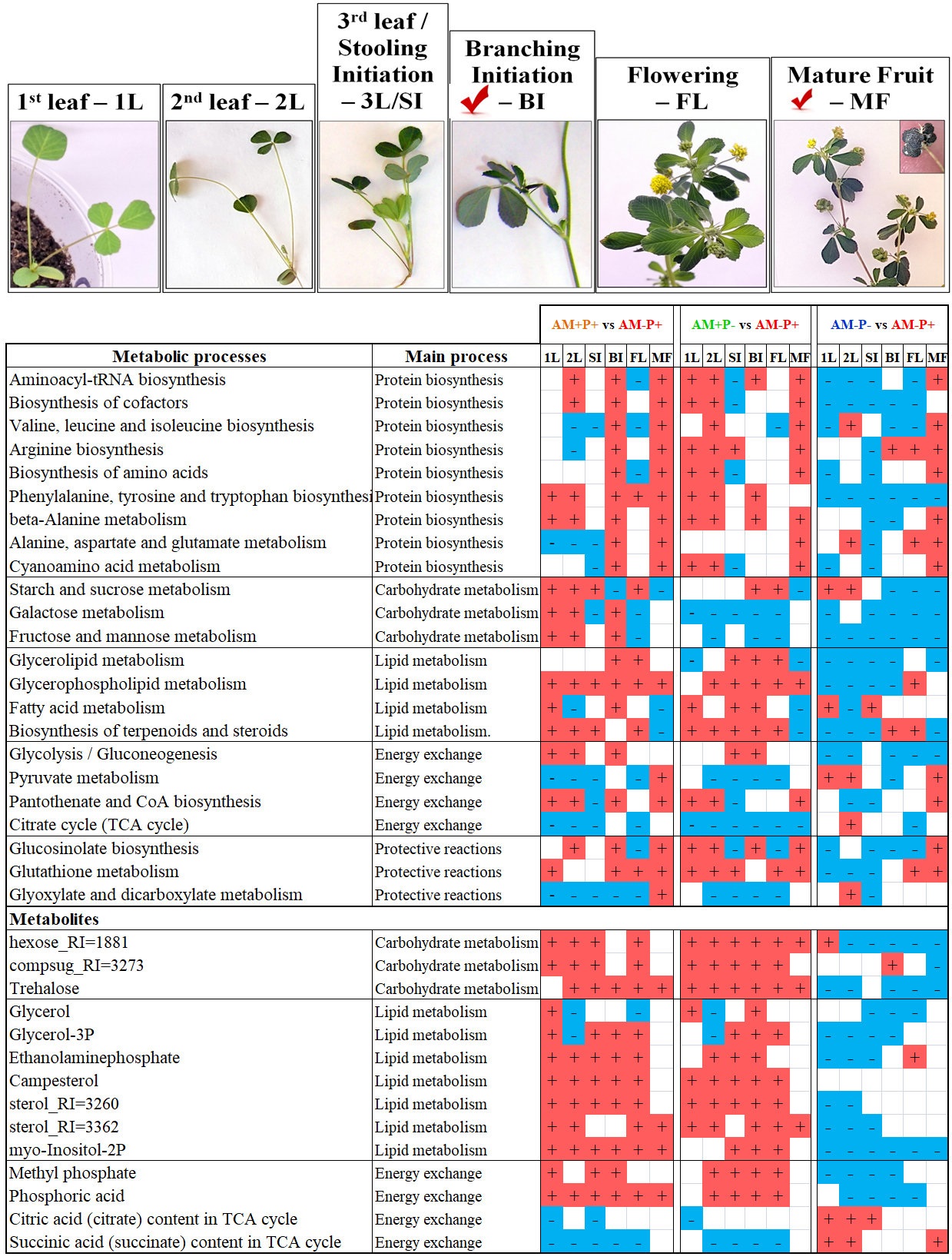

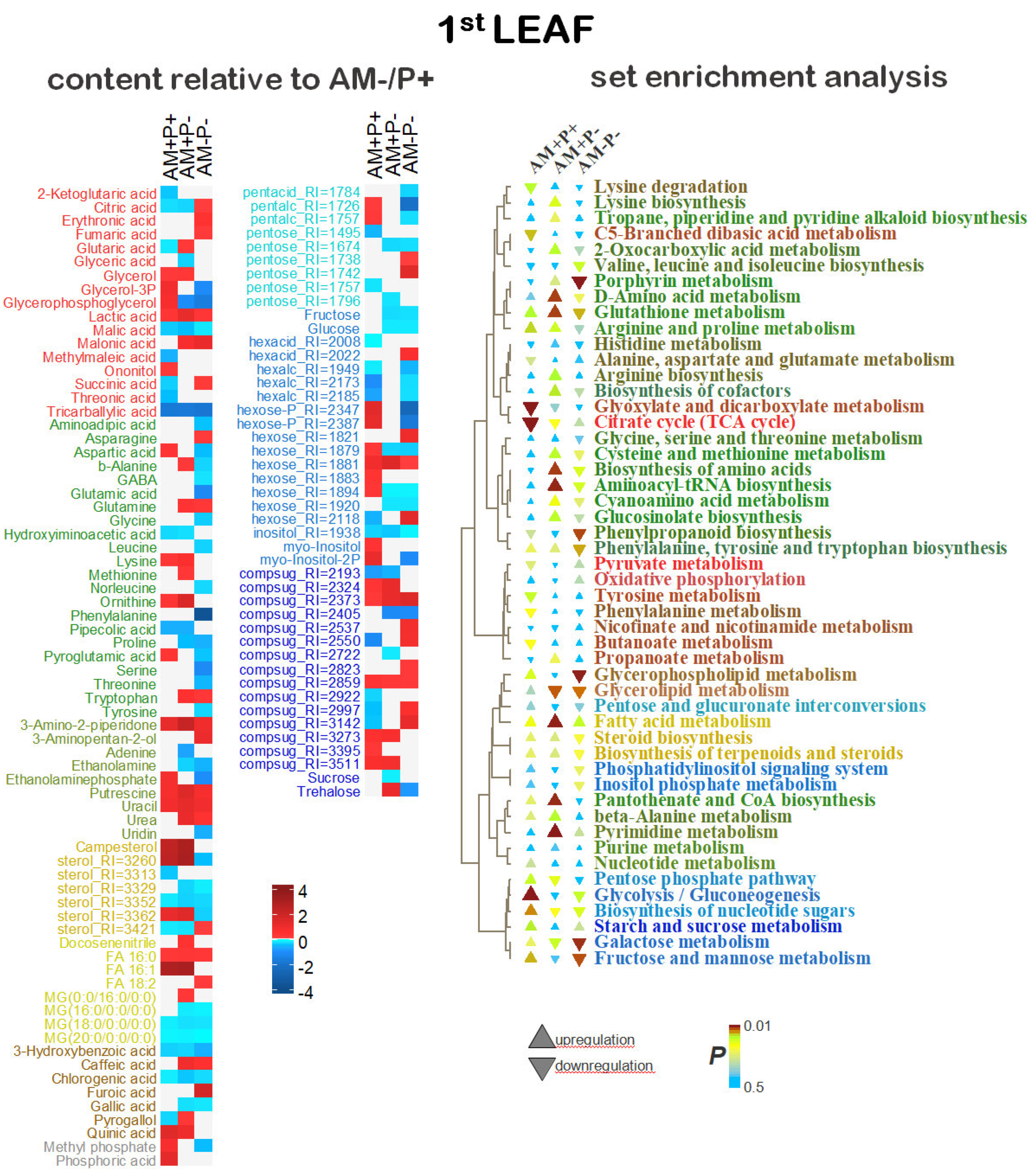

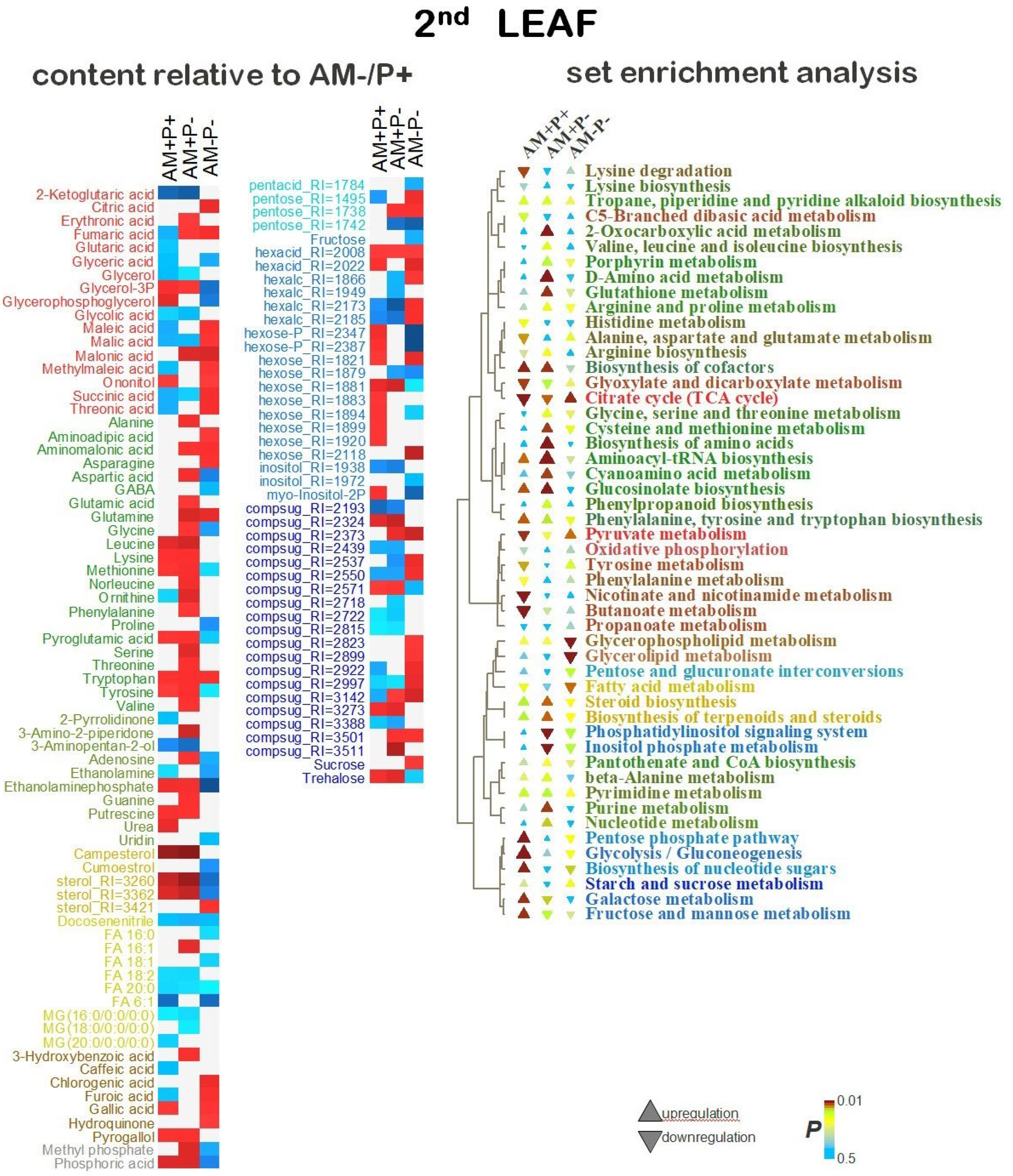

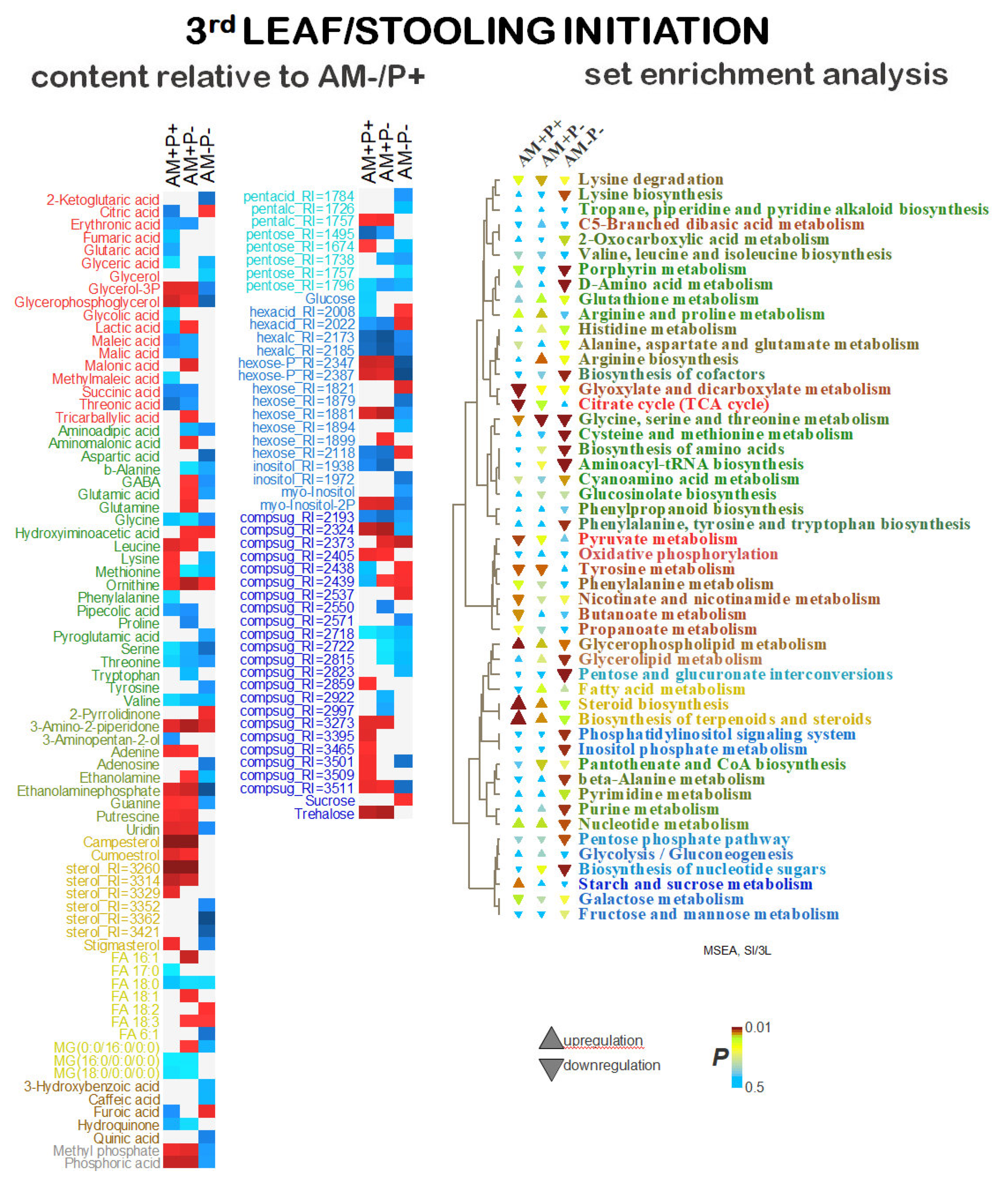

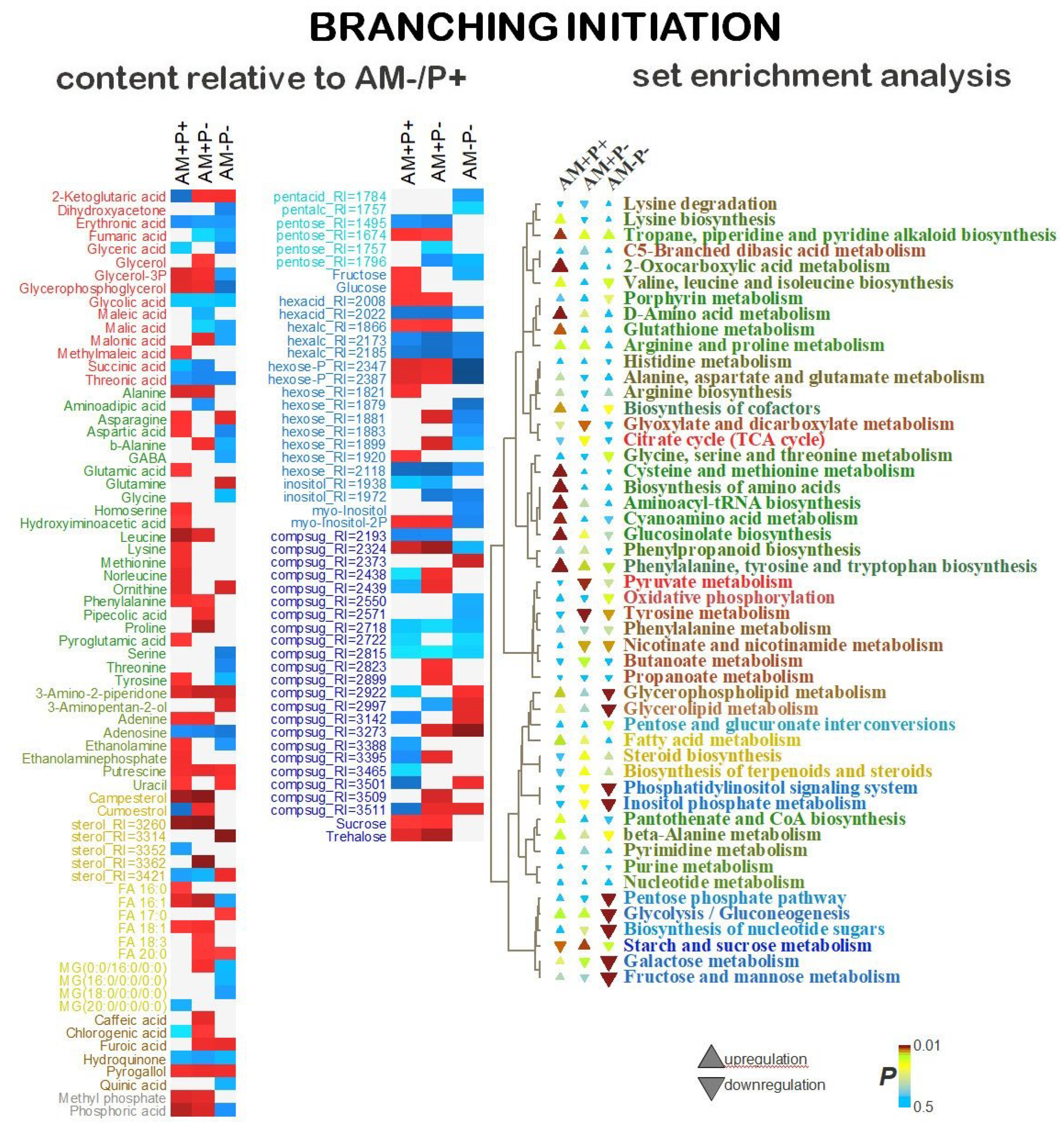

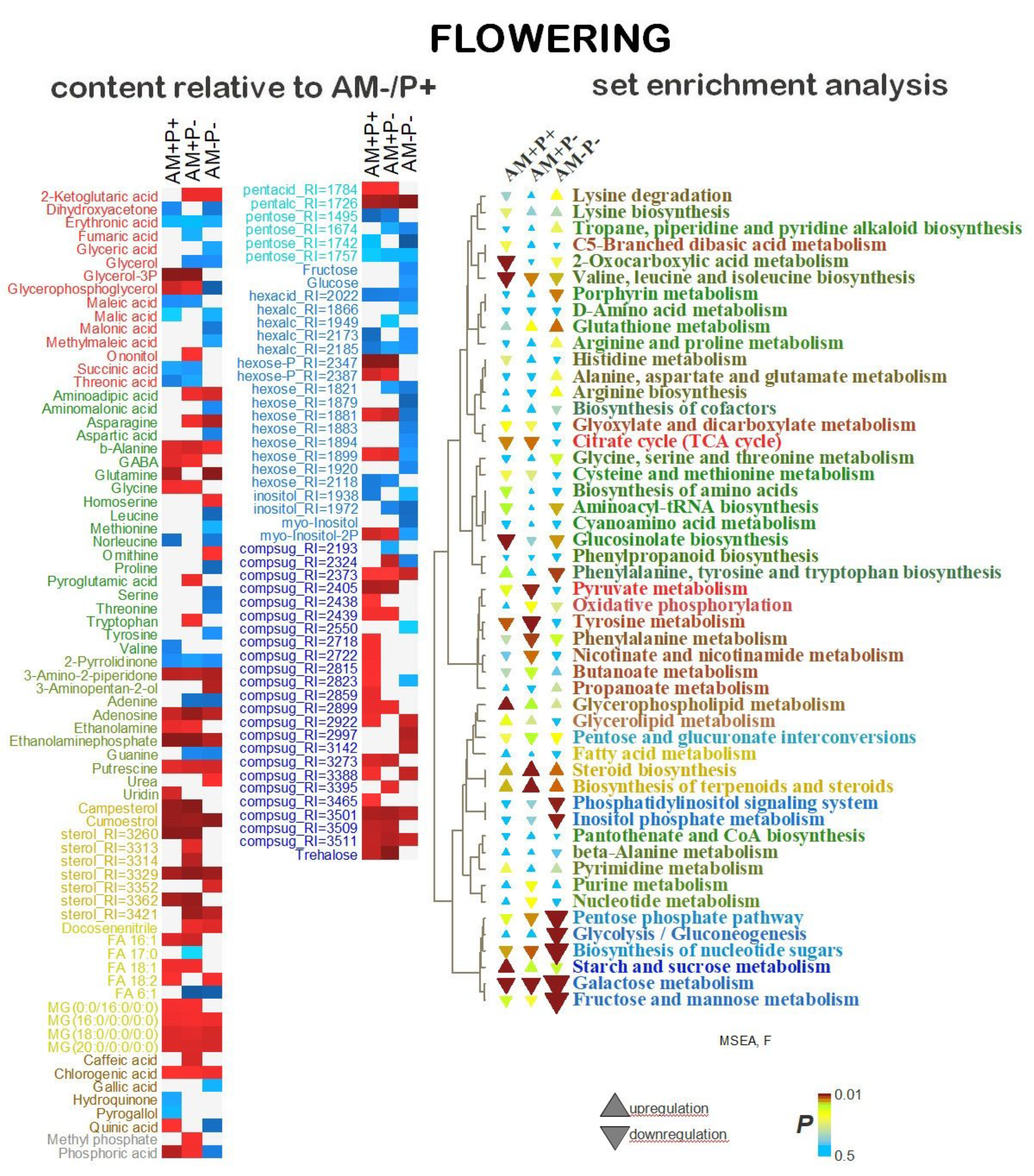

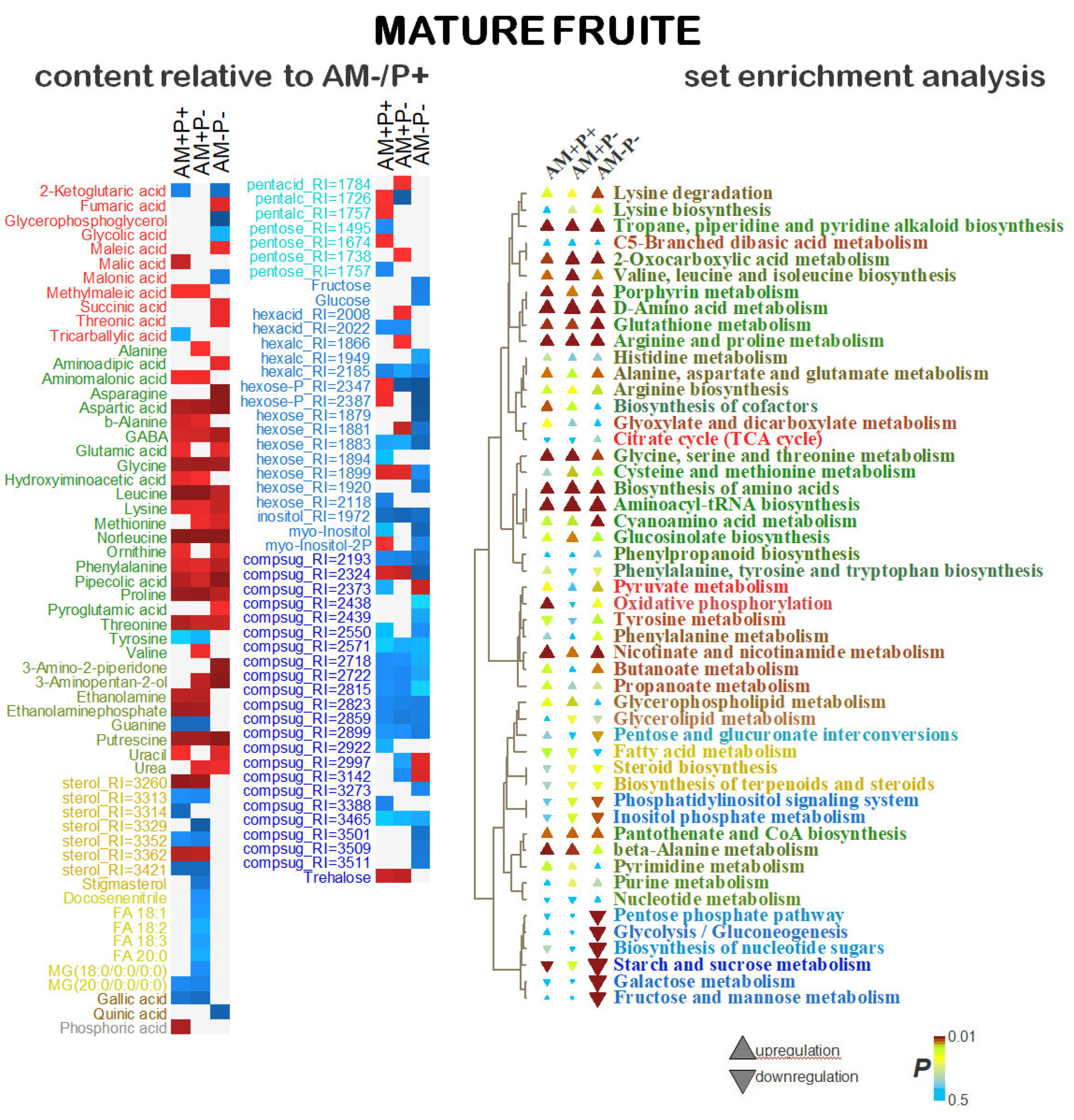

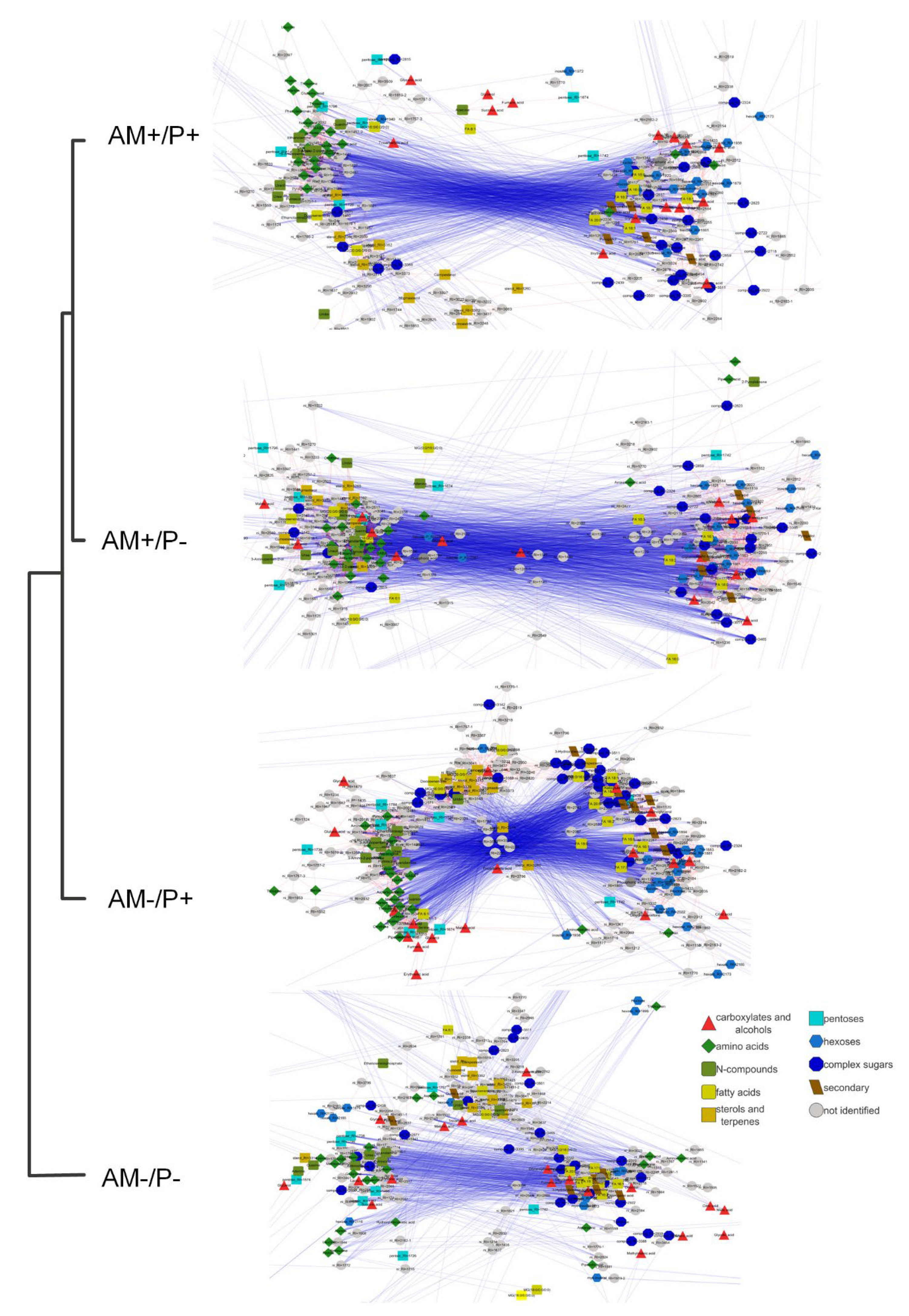

2.5. Identification of Differentially Accumulating Metabolites

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant and Fungus Biomaterials

4.2. Experimental Design and Plant Growth Conditions

4.3. Evaluation of Mycorrhization Parameters

4.4. Evaluation of Mycorrhizal Growth Response – AM Symbiotic Efficiency

4.5. GC-MS Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schachtman, D.P.; Reid, R.J.; Ayling, S.M. Phosphorus Uptake by Plants: From Soil to Cell. Plant Physiology 1998, 116, 447–453. [CrossRef]

- Holford ICR (1997) Soil phosphorus: its measurement, and its uptake by plants. Aust J Soil Res 35: 227–239.

- Marschner H (1995) Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Harnett D.C., Wilson G.W.T. The role of mycorrhizas in plant community structure and dynamics: lessons from grasslands. Plant and Soil 2002, 244, 319-331. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008.

- Schüßler A., Scwarzott D., Walker C. A New Fungal Phylum, the Glomeromycota: Phylogeny and Evolution. Mycological Research 2001, 105, 1413–1421. [CrossRef]

- Schüßler A. Glomeromycota phylogeny. http://www.amf-phylogeny.com. Accessed and last updated 04 Apr 2024.

- Zhu Y.-G., Cavagnaro T.R., Smith S.E. Backseat driving? Accessing phosphate beyond the rhizosphere-depletion zone. Trends Plant Sci. 2001, 6, 194-195. [CrossRef]

- Smith S.E., Smith F. A., Jakobsen I. Mycorrhizal Fungi Can Dominate Phosphate Supply to Plants Irrespective of Growth Responses. Plant Physiology 2003, 133, 16–20. [CrossRef]

- Xie X., Lai W., Che X., Wang S., Ren Y., Hu W., Chen H., Tang M. A SPX domaincontaining phosphate transporter from Rhizophagus irregularis handles phosphate homeostasis at symbiotic interface of arbuscular mycorrhizas. New Phytologist 2022, 234, 650–671. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Versaw,W.K.; Pumplin, N.; Gomez, S.K.; Blaylock, L.A.; Harrison, M.J. Closely related members of the Medicago truncatula PHT1 phosphate transporter gene family encode phosphate transporters with distinct biochemical activities. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 24673–24681. [CrossRef]

- Voß, S.; Betz, R.; Heidt, S.; Corradi, N.; Requena, N. RiCRN1, a crinkler effector from the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus irregularis, functions in arbuscule development. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2068. [CrossRef]

- Krajinski, F.; Courty, P.E.; Sieh, D.; Franken, P.; Zhang, H.; Bucher, M.; Gerlach, N.; Kryvoruchko, I.; Zoeller, D.; Udvardi, M.; et al. The H+-ATPase HA1 of Medicago truncatula is essential for phosphate transport and plant growth during arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. The Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1808–1817. [CrossRef]

- Bagyaraj, D. J., Sharma, M. P., Maiti, D. Phosphorus nutrition of crops through arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Current Science. 2015 108, 1288–1293, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24905490.

- Priyadharsini, P.; Muthukumar, T. The Root Endophytic Fungus Curvularia Geniculata from Parthenium Hysterophorus Roots Improves Plant Growth through Phosphate Solubilization and Phytohormone Production. Fungal Ecology 2017, 27, 69–77. [CrossRef]

- Qi S., Wang J., Wan L., Dai Z., da Silva Matos D.M., Du D., Egan S., Bonser S.P., Thomas T., Moles A.T. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi contribute to phosphorous uptake and allocation strategies of Solidago canadensis in a phosphorous-deficient environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 831654. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Smith, F.A.; Jakobsen, I. Functional diversity in arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbioses: The contribution of the mycorrhizal P uptake pathway is not correlated with mycorrhizal responses in growth or total P uptake. New Phytologist 2004, 162, 511–524. [CrossRef]

- Bucher, M. Functional biology of plant phosphate uptake at root and mycorrhiza interfaces. New Phytologist 2007, 173, 11–26. [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Y., Smith, S. E., Holloway, R. E., Zhu, Y. G., Smith, F. A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi contribute to phosphorus uptake by wheat grown in a phosphorus-fixing soil even in the absence of positive growth responses. New Phytologist 2006, 172, 536–543. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-Y.; Grønlund, M.; Jakobsen, I.; Grotemeyer, M.S.; Rentsch, D.; Miyao, A.; Hirochika, H.; Kumar, C.S.; Sundaresan, V.; Salamin, N.; et al. Nonredundant Regulation of Rice Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis by Two Members of the PHOSPHATE TRANSPORTER1 Gene Family. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 4236–4251. [CrossRef]

- Watts-Williams, S.J.; Emmett, B.D.; Levesque-Tremblay, V.; MacLean, A.M.; Sun, X.; Satterlee, J.W.; Fei, Z.; Harrison, M.J. Diverse Sorghum bicolor accessions show marked variation in growth and transcriptional responses to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Cell & Environment 2019, 42, 1758–1774. [CrossRef]

- Olalde-Portugal, V.; Cabrera-Ponce, J.L.; Gastelum-Arellanez, A.; Guerrero-Rangel, A.; Winkler, R.; Valdés-Rodríguez, S. Proteomic Analysis and Interactions Network in Leaves of Mycorrhizal and Nonmycorrhizal Sorghum Plants under Water Deficit. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8991. [CrossRef]

- Goddard, M.-L.; Belval, L.; Martin, I.R.; Roth, L.; Laloue, H.; Deglène-Benbrahim, L.; Valat, L.; Bertsch, C.; Chong, J. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis Triggers Major Changes in Primary Metabolism Together with Modification of Defense Responses and Signaling in Both Roots and Leaves of Vitis vinifera. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 721614. [CrossRef]

- Schliemann, W.; Ammer, C.; Strack, D. Metabolite profiling of mycorrhizal roots of Medicago truncatula. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 112–146. [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, R.; Baier, M.C.; Persicke, M.; Müller, C. High specificity in plant leaf metabolic responses to arbuscular mycorrhiza. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 3886. [CrossRef]

- Pedone-Bonfim, M.V.; A Lins, M.; Coelho, I.R.; Santana, A.S.; Da Silva, F.S.B.; Maia, L.C. Mycorrhizal technology and phosphorus in the production of primary and secondary metabolites in cebil (Anadenanthera colubrina (Vell.) Brenan) seedlings. J Sci Food Agric 2013, 93, 1479–1484. [CrossRef]

- Rivero, J.; Gamir, J.; Aroca, R.; Pozo, M.J.; Flors, V. Metabolic transition in mycorrhizal tomato roots. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

- Tavarini, S.; Passera, B.; Martini, A.; Avio, L.; Sbrana, C.; Giovannetti, M.; Angelini, L.G. Plant Growth, Steviol Glycosides and Nutrient Uptake as Affected by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Phosphorous Fertilization in Stevia Rebaudiana Bert. Industrial Crops and Products 2018, 111, 899–907. [CrossRef]

- Shtark, O.Y.; Puzanskiy, R.K.; Avdeeva, G.S.; Yurkov, A.P.; Smolikova, G.N.; Yemelyanov, V.V.; Kliukova, M.S.; Shavarda, A.L.; Kirpichnikova, A.A.; Zhernakov, A.I.; et al. Metabolic Alterations in Pea Leaves during Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Development. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7495. [CrossRef]

- Shtark, O.; Puzanskiy, R.; Avdeeva, G.; Yemelyanov, V.; Shavarda, A.; Romanyuk, D.; Kliukova, M.; Kirpichnikova, A.; Tikhonovich, I.; Zhukov, V.; et al. Metabolic Alterations in Pisum Sativum Roots during Plant Growth and Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Development. Plants 2021, 10, 1033. [CrossRef]

- Yurkov, A.P.; Puzanskiy, R.K.; Avdeeva, G.S.; Jacobi, L.M.; Gorbunova, A.O.; Kryukov, A.A.; Kozhemyakov, A.P.; Laktionov, Y.V.; Kosulnikov, Y.V.; Romanyuk, D.A.; et al. Mycorrhiza-Induced Alterations in Metabolome of Medicago Lupulina Leaves during Symbiosis Development. Plants 2021, 10, 2506. [CrossRef]

- Andrino, A.; Guggenberger, G.; Sauheitl, L.; Burkart, S.; Boy, J. Carbon Investment into Mobilization of Mineral and Organic Phosphorus by Arbuscular Mycorrhiza. Biol Fertil Soils 2021a, 57, 47–64. [CrossRef]

- Andrino, A.; Guggenberger, G.; Kernchen, S.; Mikutta, R.; Sauheitl, L.; Boy, J. Production of Organic Acids by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Their Contribution in the Mobilization of Phosphorus Bound to Iron Oxides. Front. Plant Sci. 2021b, 12, 661842. [CrossRef]

- Yurkov, A.P.; Puzanskiy, R.K.; Kryukov, A.A.; Gorbunova, A.O.; Kudriashova, T.R.; Jacobi, L.M.; Kozhemyakov, A.P.; Romanyuk, D.A.; Aronova, E.B.; Avdeeva, G.S.; et al. The Role of Medicago Lupulina Interaction with Rhizophagus Irregularis in the Determination of Root Metabolome at Early Stages of AM Symbiosis. Plants 2022, 11, 2338. [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Su, J.; Yang, T.; Liu, B.; Ma, B.; Ma, F.; Li, M.; Zhang, M. Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Reveal Effect of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Growth and Development of Apple Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1052464. [CrossRef]

- Chialva, M.; Patono, D.L.; De Souza, L.P.; Novero, M.; Vercellino, S.; Maghrebi, M.; Morgante, M.; Lovisolo, C.; Vigani, G.; Fernie, A.; et al. The Mycorrhizal Root-shoot Axis Elicits Coffea Arabica Growth under Low Phosphate Conditions. New Phytologist 2023, 239, 271–285. [CrossRef]

- Saia, S.; Ruisi, P.; Fileccia, V.; Di Miceli, G.; Amato, G.; Martinelli, F. Metabolomics Suggests That Soil Inoculation with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Decreased Free Amino Acid Content in Roots of Durum Wheat Grown under N-Limited, P-Rich Field Conditions. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129591. [CrossRef]

- Pu, C.; Yang, G.; Li, P.; Ge, Y.; Garran, T.A.; Zhou, X.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chen, M.; Huang, L. Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Alters the Nutritional Requirements in Salvia Miltiorrhiza and Low Nitrogen Enhances the Mycorrhizal Efficiency. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 19633. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Hao, Z.; Yu, M.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, A.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, B. Improved Phosphorus Nutrition by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis as a Key Factor Facilitating Glycyrrhizin and Liquiritin Accumulation in Glycyrrhiza Uralensis. Plant Soil 2019, 439, 243–257. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Lu, W.; Ma, C. Response of Alfalfa Growth to Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria under Different Phosphorus Application Levels. AMB Expr 2020, 10, 200. [CrossRef]

- Balzergue, C.; Puech-Pagès, V.; Bécard, G.; Rochange, S.F. The Regulation of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis by Phosphate in Pea Involves Early and Systemic Signalling Events. Journal of Experimental Botany 2011, 62, 1049–1060. [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, U.; Du Toit, L.J.; Hajibabaei, M.; McDonald, M.R. Influence of Plant Species, Mycorrhizal Inoculant, and Soil Phosphorus Level on Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Communities in Onion and Carrot Roots. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1324626. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Campbell, B.J.; Suseela, V. Root Metabolome of Plant–Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis Mirrors the Mutualistic or Parasitic Mycorrhizal Phenotype. New Phytologist 2022, 234, 672–687. [CrossRef]

- Davey, M.P.; Burrell, M.M.; Woodward, F.I.; Quick, W.P. Population-specific Metabolic Phenotypes of Arabidopsis Lyrata ssp. Petraea. New Phytologist 2008, 177, 380–388. [CrossRef]

- Bertram, H.C.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Jensen, C.S.; Pedersen, M.G.; Didion, T.; Petersen, B.O.; Duus, J.Ø.; Larsen, M.K.; Nielsen, J.H. Seasonal Changes in the Metabolic Fingerprint of 21 Grass and Legume Cultivars Studied by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance-Based Metabolomics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 4336–4341. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Saifullah; Khan, S.; Wilson, E.G.; Kricun, S.D.P.; Meissner, A.; Goraler, S.; Deelder, A.M.; Choi, Y.H.; Verpoorte, R. Metabolic Classification of South American Ilex Species by NMR-Based Metabolomics. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 773–784. [CrossRef]

- Miyagi, A.; Takahashi, H.; Takahara, K.; Hirabayashi, T.; Nishimura, Y.; Tezuka, T.; Kawai-Yamada, M.; Uchimiya, H. Principal Component and Hierarchical Clustering Analysis of Metabolites in Destructive Weeds; Polygonaceous Plants. Metabolomics 2010, 6, 146–155. [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, R.; Müller, C. Leaf Metabolome in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2015, 26, 120–126. [CrossRef]

- Yurkov, A.P.; Jacobi, L.M.; Gapeeva, N.E.; Stepanova, G.V.; Shishova, M.F. Development of Arbuscular Mycorrhiza in Highly Responsive and Mycotrophic Host Plant–Black Medick (Medicago Lupulina L.). Russ J Dev Biol 2015, 46, 263–275. [CrossRef]

- Yurkov, A.; Kryukov, A.; Gorbunova, A.; Sherbakov, A.; Dobryakova, K.; Mikhaylova, Y.; Afonin, A.; Shishova, M. AM-Induced Alteration in the Expression of Genes, Encoding Phosphorus Transporters and Enzymes of Carbohydrate Metabolism in Medicago Lupulina. Plants 2020, 9, 486. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, S.; Hu, W.; Xiao, L.; Tang, M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus irregularis increased potassium content and expression of genes encoding potassium channels in Lycium barbarum. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Yurkov, A.P.; Kryukov, A.A.; Gorbunova, A.O.; Kudriashova, T.R.; Kovalchuk, A.I.; Gorenkova, A.I.; Bogdanova, E.M.; Laktionov, Y.V.; Zhurbenko, P.M.; Mikhaylova, Y.V.; et al. Diversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Distinct Ecosystems of the North Caucasus, a Temperate Biodiversity Hotspot. JoF 2023, 10, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Suseela, V. Unraveling Arbuscular Mycorrhiza-Induced Changes in Plant Primary and Secondary Metabolome. Metabolites 2020, 10, 335. [CrossRef]

- Kryukov, A.A.; Gorbunova, A.O.; Kudriashova, T.R.; Ivanchenko, O.B.; Shishova, M.F.; Yurkov, A.P. SWEET Transporters of Medicago Lupulina in the Arbuscular-Mycorrhizal System in the Presence of Medium Level of Available Phosphorus. Vestn. VOGiS 2023, 27, 189–196. [CrossRef]

- Cartabia, A.; Tsiokanos, E.; Tsafantakis, N.; Lalaymia, I.; Termentzi, A.; Miguel, M.; Fokialakis, N.; Declerck, S. The Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Rhizophagus Irregularis MUCL 41833 Modulates Metabolites Production of Anchusa Officinalis L. Under Semi-Hydroponic Cultivation. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 724352. [CrossRef]

- Metwally, R.A.; Soliman, S.A.; Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Abdelhameed, R.E. The Individual and Interactive Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Trichoderma Viride on Growth, Protein Content, Amino Acids Fractionation, and Phosphatases Enzyme Activities of Onion Plants Amended with Fish Waste. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 214, 112072. [CrossRef]

- Douds, D.D., Jr.; Pfeffer, P.E.; Shachar-Hill, Y. Carbon partitioning, cost and metabolism of arbuscular mycorrhizas. In Arbuscular Mycorrhizas: Physiology and Function; Kapulnik, Y., Douds, D.D., Jr., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000, 107–130. [CrossRef]

- Rivero, J.; Álvarez, D.; Flors, V.; Azcón-Aguilar, C.; Pozo, M.J. Root metabolic plasticity underlies functional diversity in mycorrhiza-enhanced stress tolerance in tomato. New Phytologist 2018, 220, 1322–1336. [CrossRef]

- Kameoka, H.; Gutjahr, C. Functions of Lipids in Development and Reproduction of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Plant and Cell Physiology 2022, 63, 1356–1365. [CrossRef]

- Brands, M.; Dörmann, P. Two AMP-Binding Domain Proteins from Rhizophagus Irregularis Involved in Import of Exogenous Fatty Acids. MPMI 2022, 35, 464–476. [CrossRef]

- Luginbuehl, L.H.; Oldroyd, G.E.D. Understanding the arbuscule at the heart of endomycorrhizal symbioses in plants. Current Biology 2017, 27, R952–R963. [CrossRef]

- Luginbuehl, L.H., Van Erp, H., Cheeld, H., Mysore, K.S., Wen, J., Oldroyd, G.E., et al. Plants export 2-monopalmitin and supply both fatty acyl and glyceryl moieties to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kameoka, H.; Tsutsui, I.; Saito, K.; Kikuchi, Y.; Handa, Y.; Ezawa, T.; Hayashi, H.; Kawaguchi, M.; Akiyama, K. Stimulation of Asymbiotic Sporulation in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi by Fatty Acids. Nat Microbiol 2019, 4, 1654–1660. [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, Y.; Akiyama, R.; Tanaka, S.; Yano, K.; Kameoka, H.; Marui, S.; Saito, M.; Kawaguchi, M.; Akiyama, K.; Saito, K. Myristate Can Be Used as a Carbon and Energy Source for the Asymbiotic Growth of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 25779–25788. [CrossRef]

- Bravo, A.; Brands, M.; Wewer, V.; Dormann, P.; Harrison, M.J. Arbuscular mycorrhiza-specific enzymes FatM and RAM2 fine-tune lipid biosynthesis to promote development of arbuscular mycorrhiza. New Phytologist 2017, 214, 1631–1645. [CrossRef]

- Lohse, S.; Schliemann, W.; Ammer, C.; Kopka, J.; Strack, D.; Fester, T. Organization and Metabolism of Plastids and Mitochondria in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Roots of Medicago Truncatula. Plant Physiology 2005, 139, 329–340. [CrossRef]

- Fester T, Fetzer I, Buchert S, Lucas R, Rillig MC, Härtig C. 2011. Towards a systemic metabolic signature of the arbuscular mycorrhizal interaction. Oecologia 2011, 167, 913–924. [CrossRef]

- Sharma K., Kapoor R. Arbuscular mycorrhiza differentially adjusts central carbon metabolism in two contrasting genotypes of Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek in response to salt stress. Plant Science 2023, 332, 111706. [CrossRef]

- Kogel, K.-H.; Voll, L.M.; Schäfer, P.; Jansen, C.; Wu, Y.; Langen, G.; Imani, J.; Hofmann, J.; Schmiedl, A.; Sonnewald, S.; et al. Transcriptome and Metabolome Profiling of Field-Grown Transgenic Barley Lack Induced Differences but Show Cultivar-Specific Variances. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 6198–6203. [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, K.O.; Wilson, G.W.T.; Rinella, M.J. Predicting Plant Responses to Mycorrhizae: Integrating Evolutionary History and Plant Traits. Ecology Letters 2012, 15, 689–695. [CrossRef]

- Brundrett, M.C. Coevolution of Roots and Mycorrhizas of Land Plants. New Phytologist 2002, 154, 275–304. [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.; Son, H.; Baek, J.-H. Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle Intermediates: Regulators of Immune Responses. Life 2021, 11, 69. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Thokchom, S.D.; Kapoor, R. Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Fungus Alleviates Arsenic Mediated Disturbances in Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle and Nitrogen Metabolism in Triticum Aestivum L. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2023, 197, 107631. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.; Tang, M.; Zhang, F.; Huang, Y. Influence of Arbuscular Mycorrhiza on Organic Solutes in Maize Leaves under Salt Stress. Mycorrhiza 2011, 21, 423–430. [CrossRef]

- Che-Othman, M.H.; Jacoby, R.P.; Millar, A.H.; Taylor, N.L. Wheat Mitochondrial Respiration Shifts from the Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle to the GABA Shunt under Salt Stress. New Phytologist 2020, 225, 1166–1180. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Peng, J.T.; Klair, A.; Dickinson, A.J. Non-Canonical and Developmental Roles of the TCA Cycle in Plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2023, 74, 102382. [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.M.; Robinson, L.A.; Abdul-Sada, A.; Vanbergen, A.J.; Hodge, A.; Hartley, S.E. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Plant Chemical Defence: Effects of Colonisation on Aboveground and Belowground Metabolomes. J Chem Ecol 2018, 44, 198–208. [CrossRef]

- Johny, L.; Cahill, D.M.; Adholeya, A. AMF Enhance Secondary Metabolite Production in Ashwagandha, Licorice, and Marigold in a Fungi-Host Specific Manner. Rhizosphere 2021, 17, 100314. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Geng, Y.; Liu, K.; Shao, X. Cooperation With Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Increases Plant Nutrient Uptake and Improves Defenses Against Insects. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 833389. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Yang, F.; Tao, S.; Yan, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Improve the Growth and Performance in the Seedlings of Leymus Chinensis under Alkali and Drought Stresses. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12890. [CrossRef]

- Kose, F.; Weckwerth, W.; Linke, T.; Fiehn, O. Visualizing Plant Metabolomic Correlation Networks Using Clique–Metabolite Matrices. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 1198–1208. [CrossRef]

- Camacho, D.; De La Fuente, A.; Mendes, P. The Origin of Correlations in Metabolomics Data. Metabolomics 2005, 1, 53–63. [CrossRef]

- Steuer, R. Review: On the Analysis and Interpretation of Correlations in Metabolomic Data. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2006, 7, 151–158. [CrossRef]

- Rosato, A.; Tenori, L.; Cascante, M.; De Atauri Carulla, P.R.; Martins Dos Santos, V.A.P.; Saccenti, E. From Correlation to Causation: Analysis of Metabolomics Data Using Systems Biology Approaches. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 37. [CrossRef]

- Morgenthal, K.; Weckwerth, W.; Steuer, R. Metabolomic Networks in Plants: Transitions from Pattern Recognition to Biological Interpretation. Biosystems 2006, 83, 108–117. [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, A.; Kusano, M.; Redestig, H.; Arita, M.; Saito, K. Metabolomic Correlation-Network Modules in Arabidopsis Based on a Graph-Clustering Approach. BMC Syst Biol 2011, 5, 1. [CrossRef]

- Weckwerth, W.; Wenzel, K.; Fiehn, O. Process for the Integrated Extraction, Identification and Quantification of Metabolites, Proteins and RNA to Reveal Their Co-regulation in Biochemical Networks. Proteomics 2004, 4, 78–83. [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, J.; Jozefczuk, S.; Nikoloski, Z.; Selbig, J.; Nikiforova, V.; Catchpole, G.; Willmitzer, L. Stability of Metabolic Correlations under Changing Environmental Conditions in Escherichia Coli – A Systems Approach. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7441. [CrossRef]

- Kotze, H.L.; Armitage, E.G.; Sharkey, K.J.; Allwood, J.W.; Dunn, W.B.; Williams, K.J.; Goodacre, R. A Novel Untargeted Metabolomics Correlation-Based Network Analysis Incorporating Human Metabolic Reconstructions. BMC Syst Biol 2013, 7, 107. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Tombor, B.; Albert, R.; Oltvai, Z.N.; Barabási, A.-L. The Large-Scale Organization of Metabolic Networks. Nature 2000, 407, 651–654. [CrossRef]

- Puzanskiy, R.; Romanyuk, D.; Shishova, M. Coordinated Alterations in Gene Expression and Metabolomic Profiles of Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii during Batch Autotrophic Culturing. BioComm 2018, 63, 87–99. [CrossRef]

- Min Lee, J.; Gianchandani, E.P.; Eddy, J.A.; Papin, J.A. Dynamic Analysis of Integrated Signaling, Metabolic, and Regulatory Networks. PLoS Comput Biol 2008, 4, e1000086. [CrossRef]

- Sergaliev, N.Kh.; Yurkov, A.P.; Tlepov, A.S.; Dzhaparov, R.Sh.; Volodin, M.A.; Amenova, R.K. Influence of arbuscular mycorhiza fungus (Glomus intraradices) on the productivity of spring durum wheat in dark-chestnut soil under the dry-steppe zone conditions of Priuralie. Novosti nauki Kazahstana 2013, 3(117), 149–154.

- Yurkov, A.P.; Jacobi, L.M.; Stepanova, G.V.; Shoshova, M.F. Symbiotic efficiency and mycorrhization indices for ten strains of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in black medic under conditions of different phosphorus levels in soil. Nat Tech Sci 2016, 12(102), 67–74.

- Yurkov, A.P.; Kryukov, A.A.; Jacobi, L.M.; Kozhemyakov, A.P.; Shishova, M.F. Identification, symbiotic efficiency and activity of collection strains of arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi. Curr Biotechnol 2017, 2(21): 270–274.

- Yurkov, A.P.; Kryukov, A.A.; Yacobi, L.M.; Kozhemyakov, A.P.; Shishova, M.F. Correlations of activity and efficiency charachteristics for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi with different origin. Tavričeskij vestnik agrarnoj nauki (TVAN) 2017, 4(12): 31–41.

- Kryukov, A.A.; Yurkov, A.P. Optimization procedures for molecular-genetic identification of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in symbiotic phase on the example of two closely kindred strains. Mikol. Fitopatol. 2018, 52, 38–48.

- Klechkovsky V.M., Petersburgsky A.V. Agrochemistry. Moscow: Kolos Publ., 1967.

- Phillips, J.M.; Hayman, D.S. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 1970, 55, 158-IN18. [CrossRef]

- Trouvelot, A.; Kough, J.L.; Gianinazzi-Pearson, V. Mesure du taux de mycorhization VA d’un système radiculaire. Recherche de méthodes ayant une signification fonctionnelle. In Physiological and Genetical Aspects of Mycorrhizae; Gianinazzi-Pearson, V., Gianinazzi, S., Eds.; INRA-Press: Paris, France, 1986, 217–221.

- Vorobyev, N.I.; Yurkov, A.P.; Provorov, N.A. Certificate N2010612112 about the Registration of the Computer Program “Program for Calculating the Mycorrhization Indices of Plant Roots” (Dated 2 December 2016); The Federal Service for Intellectual Property: Moscow, Russia, 2016.

- Johnsen, L.G.; Skou, P.B.; Khakimov, B.; Bro, R. Gas chromatography – mass spectrometry data processing made easy. Journal of Chromatography A 2017, 1503, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Hummel, J.; Selbig, J.; Walther, D.; Kopka, J. The Golm Metabolome Database: A Database for GC-MS Based Metabolite Profiling. In Metabolomics; Nielsen, J., Jewett, M.C., Eds.; Topics in Current Genetics; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; Vol. 18, pp. 75–95 ISBN 978-3-540-74718-5.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2020. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Komsta, L. Outliers: Tests for Outliers. 2011. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=outliers (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Narasimhan, B.; Chu, G. Impute: Imputation for Microarray Data. R Package Version 1.60.0. 2019. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/impute.html (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Stacklies, W.; Redestig, H.; Scholz, M.; Walther, D.; Selbig, J. pcaMethods-a bioconductor package providing PCA methods for incomplete data. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1164–1167. [CrossRef]

- Thévenot, E.; Roux, A.; Xu, Y.; Ezan, E.; Junot, C. Analysis of the human adult urinary metabolome variations with age, body mass index, and gender by implementing a comprehensive workflow for univariate and OPLS statistical analyses. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 3322–3335. [CrossRef]

- Korotkevich, G.; Sukhov, V.; Sergushichev, A. Fast gene set enrichment analysis. BioRxiv 2021, 060012. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 2019. 28, 1947–1951. [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, D.; Maintainer, B. KEGGREST: Client-Side REST Access to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). R Package Version 1.36.3. 2022. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/KEGGREST.html (accessed on 19 July 2024). https://doi.org/10.18129/B9.bioc.KEGGREST.

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).