3.1. Assessment of the Influence of the Main Parameters on the Low-Temperature Pressure Oxidation of Pyrite and Chalcopyrite in Their Mixture

According to literature data, the catalytic effect of adding pyrite on copper extraction from chalcopyrite is already observed under atmospheric conditions at a temperature of 85°C. The method of mathematical experimental design with an orthogonal central-compositional second-order design was used to study the combined effect of oxygen pressure, initial sulfuric acid concentration, iron (III) ion and copper (II) ion concentrations, and duration on the oxidation of pyrite and chalcopyrite during their combined leaching [

31]. The variable parameters were oxygen pressure (X

1), initial concentrations of sulfuric acid (X

2), iron (III) ion concentration (X

3), copper (II) ion concentration (X

4), and oxidation duration (X

5). The constant leaching parameters were a temperature of 100°C, a liquid:solid ratio of 10:1, and a pyrite:chalcopyrite ratio of 1:1.

Two parameters at five levels were considered as independent variables, their central values (zero levels) were as follows: X

1 = 0.5 MPa, X

2 = 45 g/L, X

3 = 6 g/L, X

4 = 4.5 g/L, X

5 = 140 min. The experimental data were processed to obtain mathematical models and diagrams using Statgraphics software. The influence of oxygen pressure, initial sulfuric acid concentration, iron (III) ion concentration, copper (II) ion concentration and duration on the oxidation of chalcopyrite and pyrite was assessed using software data and graphical optimization tools [

32].

3.1.1. Effect of Parameters on the Oxidation of Chalcopyrite Mixed with Pyrite

Chalcopyrite may interact with sulfuric acid in the presence of oxygen and iron (III) ions according to the following reactions:

According to the presented reactions, the sulfide sulfur of chalcopyrite may be oxidized by oxygen to form elemental sulfur and sulfate ion (reactions 7–9). Iron (III) ions may also act as an oxidizer, with sulfide sulfur being converted into elemental sulfur (reaction 10), and iron (II) ions interacting with oxygen to form iron (III) ions.

The resulting mathematical model of chalcopyrite dissolution in a mixture with pyrite, depending on the effect of oxygen pressure, initial concentration of sulfuric acid, concentrations of iron (III) and copper (II) ions and duration, can be described by an equation presented below in dimensional scale:

The statistical significance of each coefficient of the equation was assessed by comparing the mean square against the experimental error estimate. According to the data obtained, the coefficients of X12, X1X2, X1X3, X3X4, X52, X4X5, X3X5, X1X5, X1X4 and X2X3 are statistically insignificant and therefore excluded from the general equation.

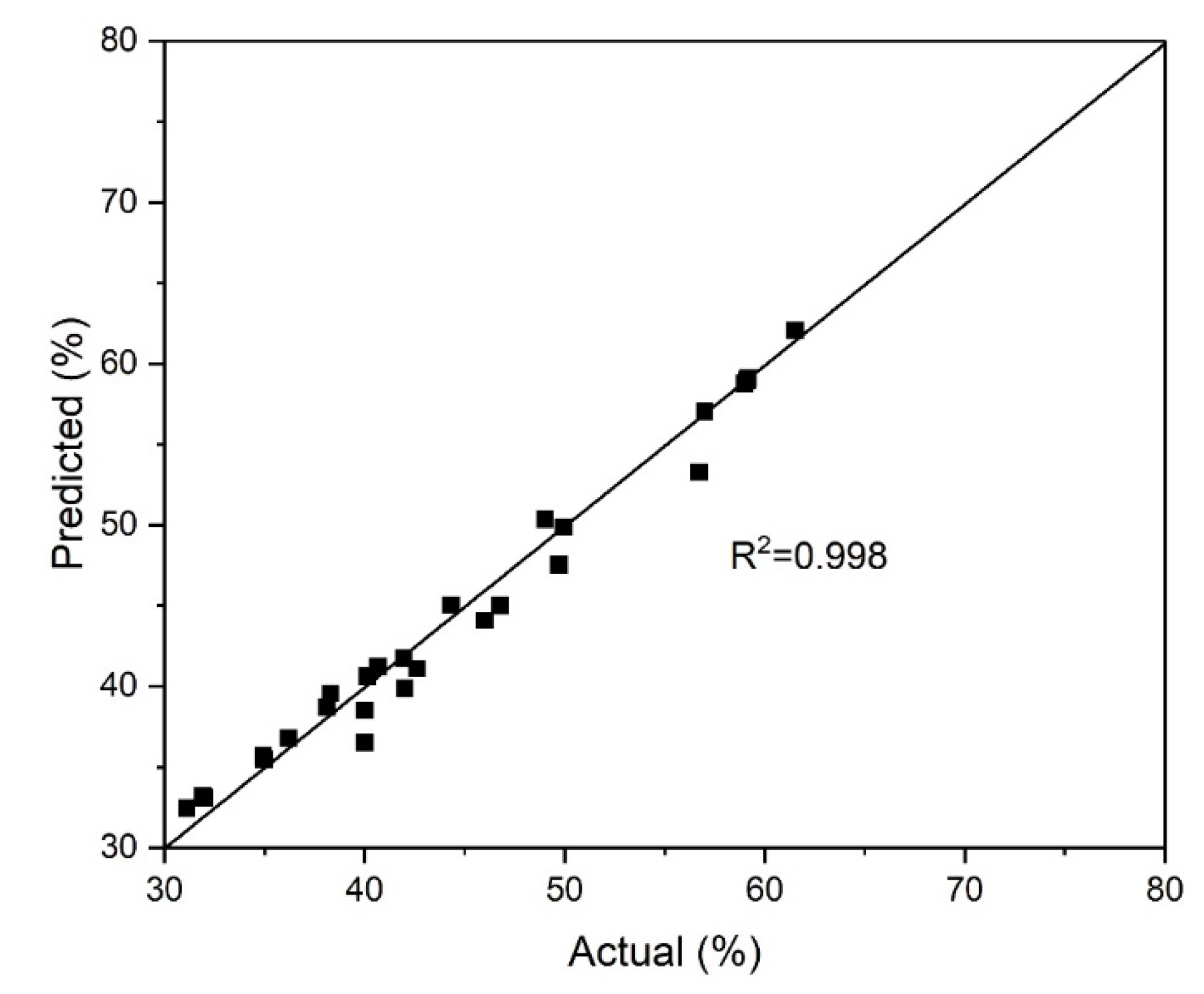

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the actual values of the arsenic precipitation degree and those predicted by the model. The reliability of the selected model (Equation (1)2) was confirmed due to the close values of the predicted and actual data.

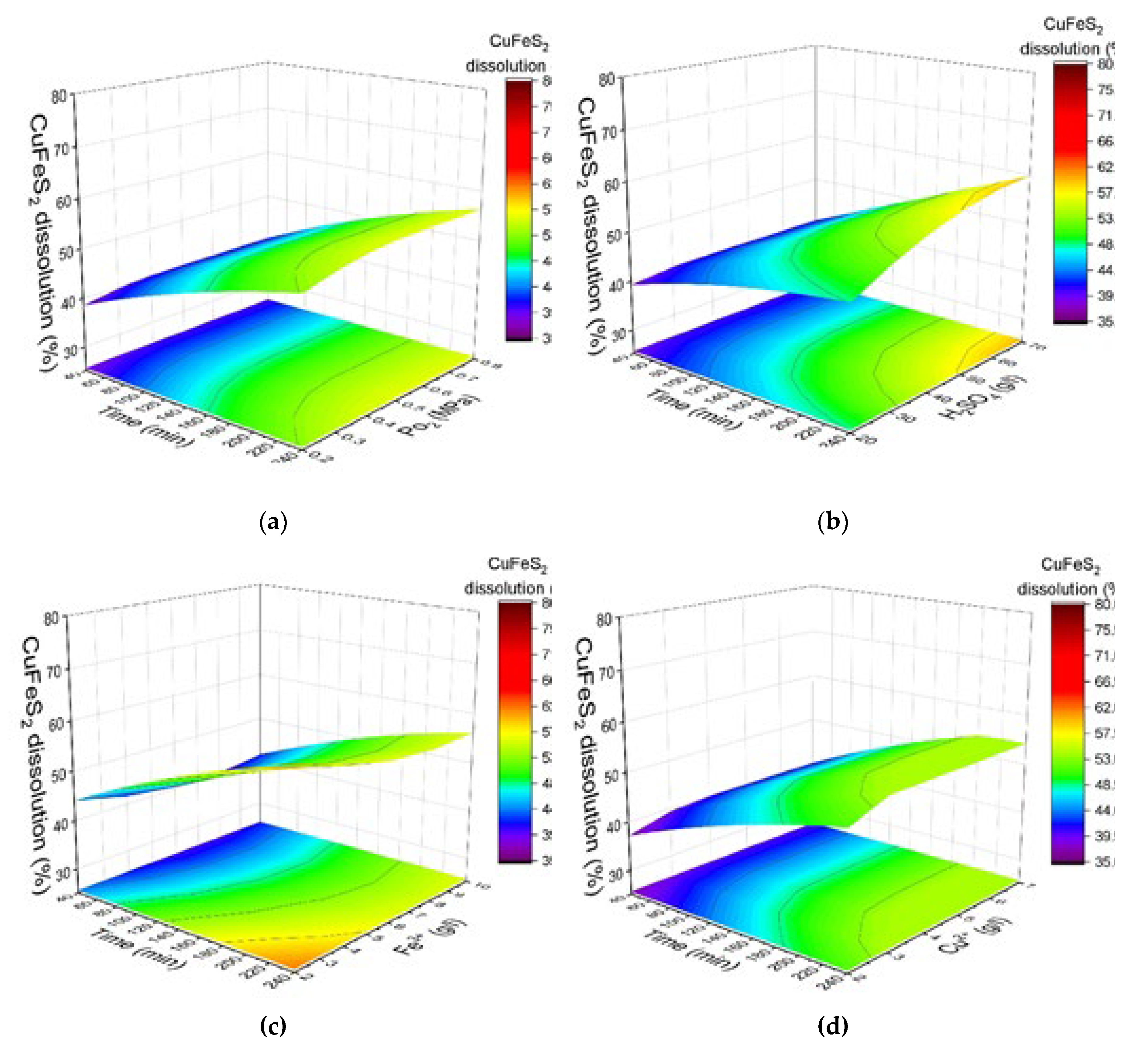

Figure 4 shows the response surfaces predicted by the model for the degree of chalcopyrite dissolution, depending on the oxygen pressure, the initial concentration of sulfuric acid, the concentrations of iron (III) and copper (II) ions and the duration. When changing one of the parameters, the others were fixed at the average value in the selected range.

Analysis of the obtained results demonstrates that all parameters varied in the selected range have a statistically significant effect on the process of chalcopyrite dissolution in its mixture with pyrite.

According to the data presented in

Figure 4a, an increase in oxygen pressure from 0.2 up to 0.8 MPa has an insignificant effect on the dissolution of chalcopyrite in its mixture with pyrite. Over 240 min of oxidation, the chalcopyrite dissolution degree increases from 53% to 56% with an increase in oxygen pressure from 0.2 MPa up to 0.8 MPa.

As can be seen from

Figure 4b, the positive effect of increasing the initial concentration of sulfuric acid is maintained throughout the process. With an increase in the initial acid concentration from 20 g/L up to 70 g/L, the chalcopyrite dissolution degree increases from 49% to 59% in 240 min.

Similarly, the initial concentration of copper (II) ions also has a positive effect on oxidation (

Figure 4c). Its increase from 1 g/L up to 3 g/L contributes to an increase in the chalcopyrite dissolution degree from 51% to 54% in 240 min.

The increase in the concentration of iron (III) ions has a negative effect on chalcopyrite oxidation throughout the process (

Figure 4d). An increase in their concentration from 2 up to 10 g/L leads to a decrease in the chalcopyrite dissolution degree from 60 to 56% in 240 min.

The negative effect of increasing the initial concentration of iron (III) ions is possibly due to an increase in the oxidation state of sulfide sulfur to elemental sulfur, which in turn shields the surface of chalcopyrite [

33].

3.1.2. Effect of Parameters on the Oxidation of Pyrite Mixed with Chalcopyrite

Pyrite interaction with sulfuric acid in the presence of oxygen and iron (III) ions may occur according to the following reactions:

According to the presented reactions, pyrite sulfide sulfur may be oxidized by oxygen to form elemental sulfur and sulfate ion (reactions 13 and 14). Iron (III) ions may also act as an oxidizer, with sulfide sulfur passing into an elemental state (reaction 15), and iron (II) ions interacting with oxygen to form iron (III) ions (reaction 17).

The mathematical model describing pyrite dissolution in its mixture with chalcopyrite depending on the influence of oxygen pressure, the initial concentration of sulfuric acid, the concentrations of iron (III) and copper (II) ions, as well as the duration of the process, can be represented by the following equation:

The statistical significance of each coefficient of the equation was assessed by comparing the mean square against the experimental error estimate. According to the data obtained, the coefficients of X12, X1X2, X1X3, X1X4, X3X4, X2X3, X3X5 and X4X5 were statistically insignificant; therefore, they were excluded from the general equation.

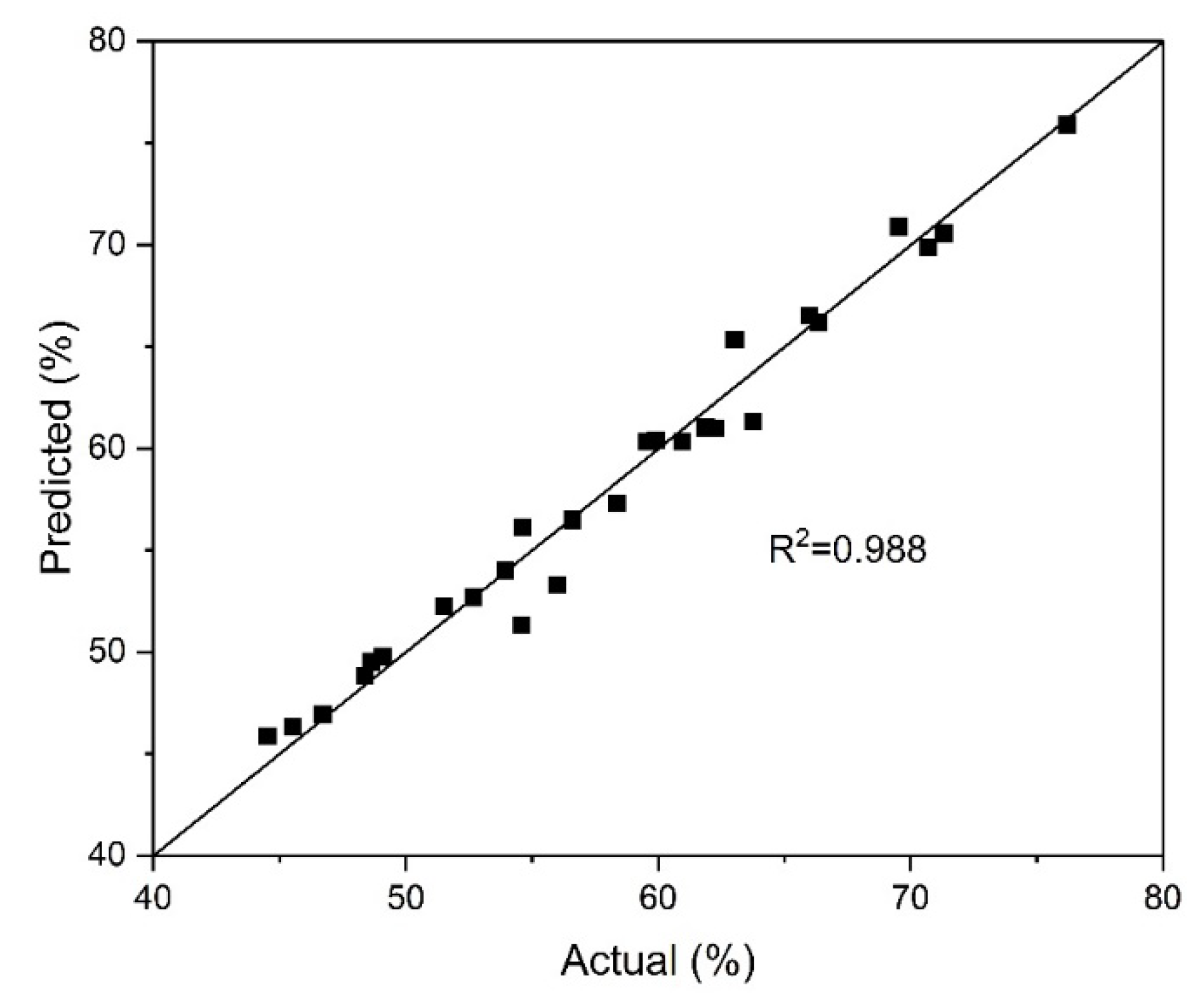

Figure 5 illustrates the correlation between the actual indicators of the pyrite dissolution degree and the values predicted by the model. The closeness of the predicted and actual data confirms the reliability of the selected model (Equation (18)).

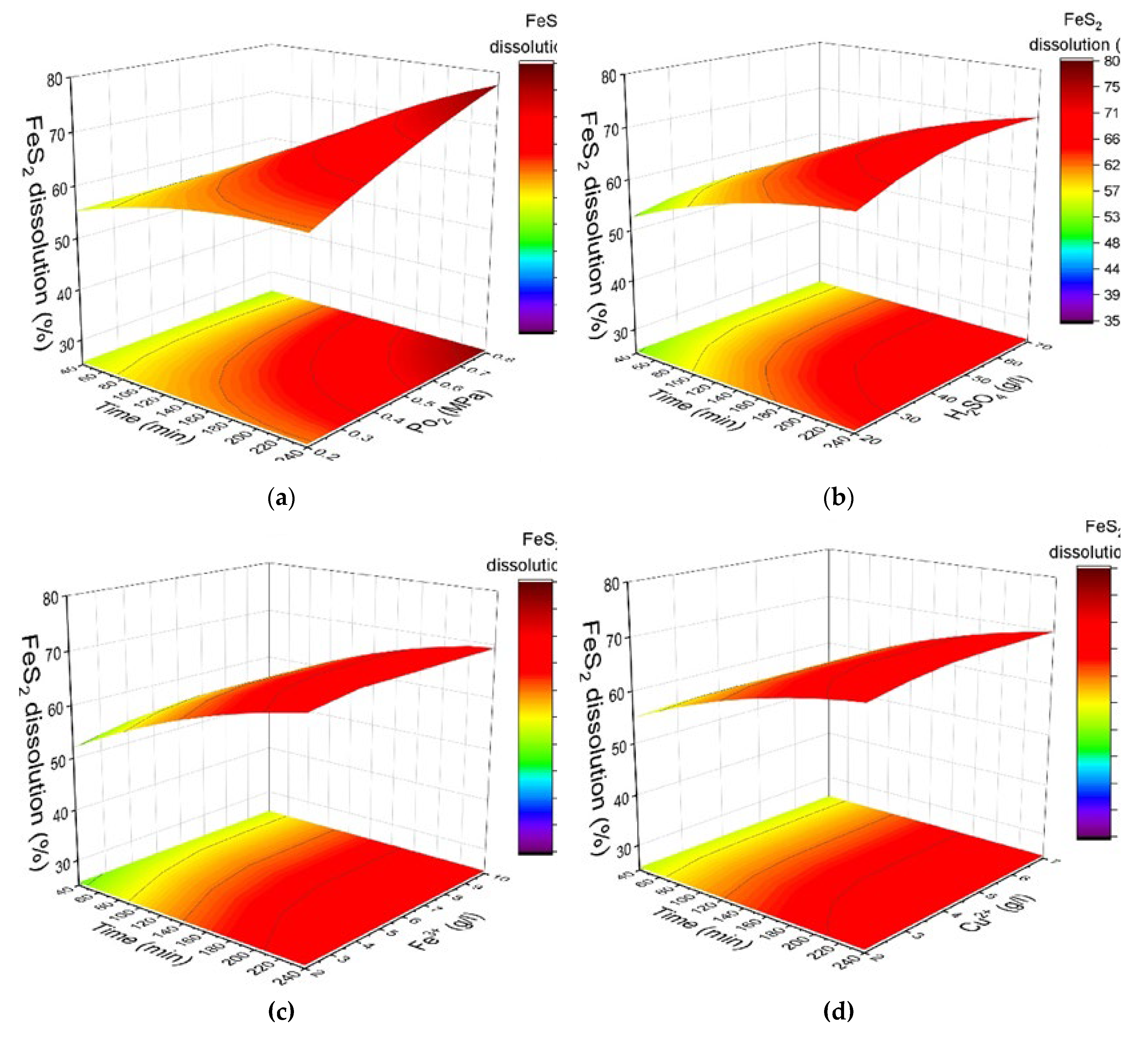

Figure 6 shows the response surfaces predicted by the obtained model for the pyrite dissolution degree, depending on the oxygen pressure, the initial concentration of sulfuric acid, the concentration of iron (III) and copper (II) ions and duration. When changing one of the parameters, the others were fixed at the average value inside the range selected.

Analysis of the results shows that all the parameters that varied in the selected range have a statistically significant positive effect on the pyrite dissolution process in the mixture with chalcopyrite.

Increasing the oxygen pressure from 0.2 up to 0.8 MPa has the most significant positive effect on pyrite dissolution in its mixture with chalcopyrite (

Figure 6a). This positive effect was observed throughout the entire process of pressure low-temperature oxidation. With an increase in oxygen pressure from 0.2 MPa up to 0.8 MPa, the dissolution of pyrite during 240 min of the process increases from 62% to 78%.

The initial concentration of sulfuric acid also has a noticeable positive effect on the dissolution of pyrite in its mixture with chalcopyrite (

Figure 6b). When the initial concentration of acid increases from 20 g/L up to 70 g/L, the pyrite dissolution degree increases from 64% to 71% over the same period of 240 min. The positive effect of sulfuric acid is probably due to the reduction in the formation of iron hydroxides and oxides on the surface of pyrite particles. These compounds may shield the mineral surface, hindering access for reagents [

34].

Iron (III) ions also have a slight positive effect on the oxidation of pyrite in its mixture with chalcopyrite throughout the oxidation process. When the concentration of iron (III) ions increases from 2 up to 7 g/L, the pyrite dissolution degree increases from 67% to 69% in 240 min. A subsequent increase in concentration up to 10 g/L has almost no additional effect (

Figure 6c).

The initial concentration of copper (II) ions demonstrates a minor but statistically significant positive effect on the pyrite dissolution process in a mixture with chalcopyrite throughout the oxidation period (

Figure 6d). With an increase in the concentration of copper (II) ions from 1 up to 2 g/L, an increase in the pyrite dissolution degree is observed from 74.9% to 78.5% in 240 min. A further increase in the concentration up to 3 g/L has virtually no effect on the result.

Unlike chalcopyrite dissolution, the oxidation degree of pyrite in the mixture increases significantly. Under the conditions t = 100°C, PO2 = 0.8 MPa, [H2SO4] = 50 g/L, [Cu2+] = 3 g/L, [Fe3+] = 7 g/L, duration 240 min, the oxidation degree of pyrite in its mixture with chalcopyrite is 80.3%, while the chalcopyrite dissolution under these conditions reaches 56.4%.

3.2. Kinetic Analysis of the Dissolution of Sulfide Minerals

Since chalcopyrite and pyrite dissolution may proceed with the formation of an insoluble product (elemental sulfur) on the particle surface, their dissolution may occur in the diffusion region; the reaction rate on the surface may also be the rate-limiting stage, due to the insignificant effect of oxygen pressure on chalcopyrite dissolution.

The contracting core model (SCM) is used to describe the kinetics of heterogeneous reactions, which assumes that the interaction of a substance with an external reagent goes on the surface of a particle only. The reaction zone gradually moves into the particle, leaving behind the converted product and the particle’s inert part. The particle core containing the active, unreacted component gradually decreases during the reaction. This model assumes that the process rate is limited either by the diffusion of the reagent to the surface through the diffusion layer, or diffusion through the product layer (film diffusion through the surface layer of a decreasing sphere), or the chemical reaction for particles of constant or decreasing size. Thus, the SCM not only determines which region the process proceeds in, due to the ability to determine the main kinetic characteristics, but also shows the mechanism of the process. The slowest stage with the greatest resistance is rate-limiting, and its intensification allows for an increase in the efficiency of leaching.

To determine the reaction mode and calculate the kinetic characteristics of pyrite and chalcopyrite dissolution, the contracting core model (SCM) was used as in our previous researches [

35,

36].

Table 2 shows the main equations describing the SCM stages.

3.2.1. Kinetic Analysis of Chalcopyrite and Pyrite Dissolution During Low-Temperature Pressure Leaching without Mixing

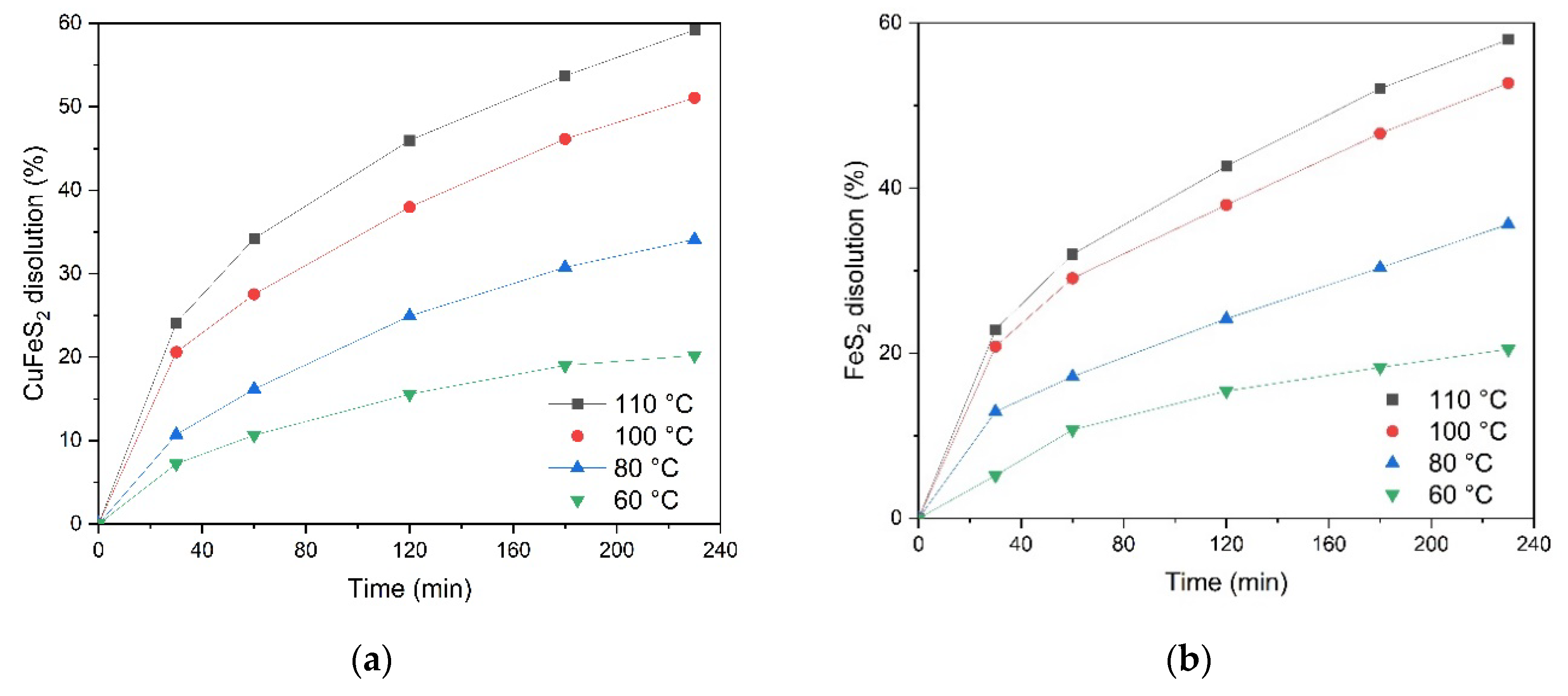

The effect of temperature on the process of low-temperature pressure oxidation of chalcopyrite and pyrite separately from each other is shown in

Figure 7.

According to

Figure 7a, temperature has a significant effect on chalcopyrite dissolution over the entire studied time range. At 110℃, up to 59.2% of chalcopyrite is oxidized in 230 min of the process. A decrease in temperature down to 60℃ leads to a decrease in the dissolution degree down to 20.2% over a similar duration.

An increase in the leaching duration from 20 up to 240 min contributes to an increase in the chalcopyrite dissolution degree, and the positive effect of temperature is preserved over the entire time range of oxidation.

Based on the data in

Figure 7b, temperature significantly affects the process of pyrite dissolution over the entire studied time interval. E.g., at a temperature of 110°C, the pyrite oxidation degree reaches 57.9% after 230 min. A decrease in temperature down to 60°C reduces the dissolution degree to 20.5% over the same period of time.

Increasing the leaching time from 20 up to 240 min increases the pyrite dissolution degree, while the positive effect of increasing the temperature is preserved at all oxidation time stages.

Table 3 provides the correlation coefficients (R

2) obtained when modeling the process of chalcopyrite and pyrite leaching separately from each other with sulfuric acid solutions using the SCM equations.

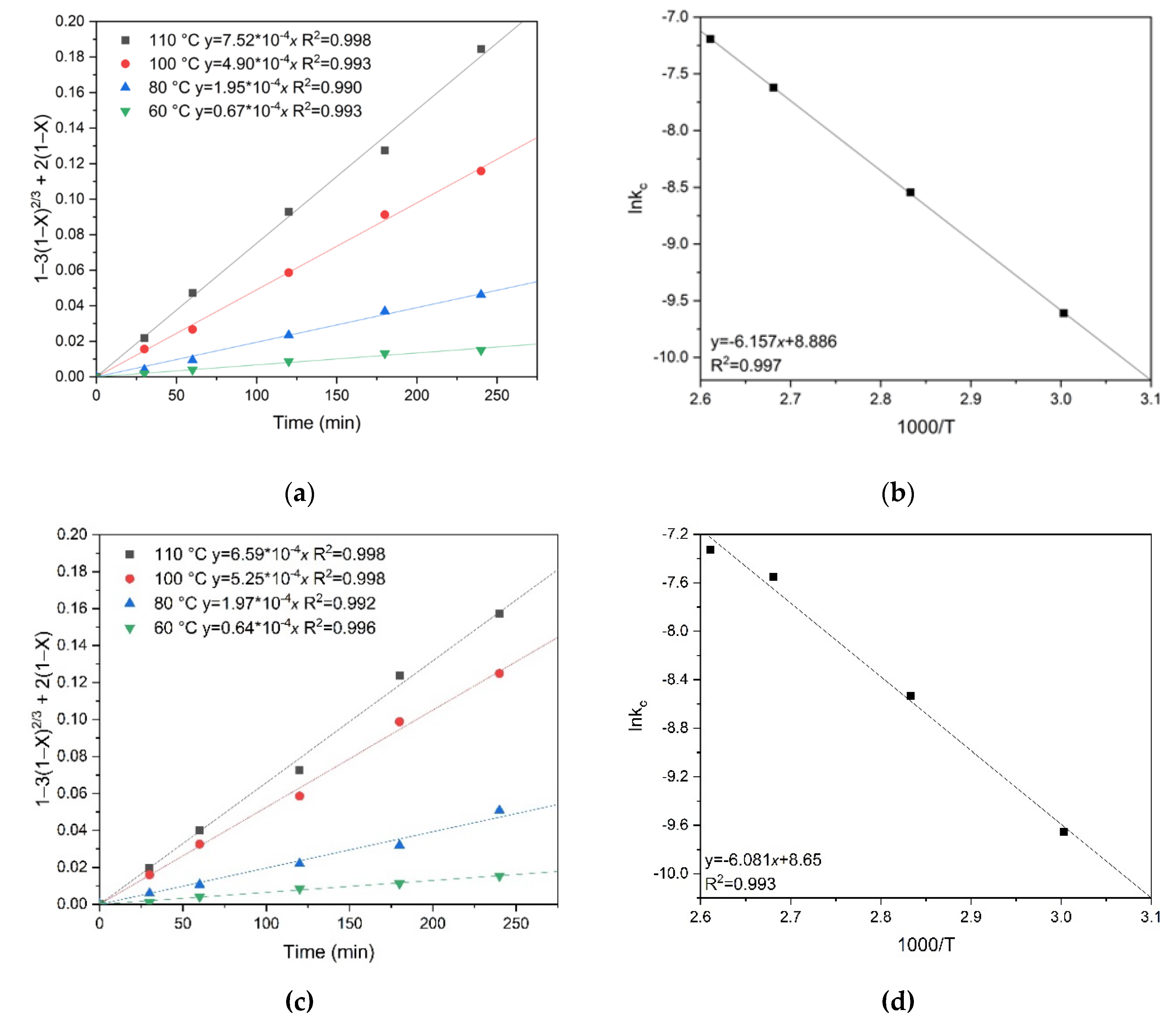

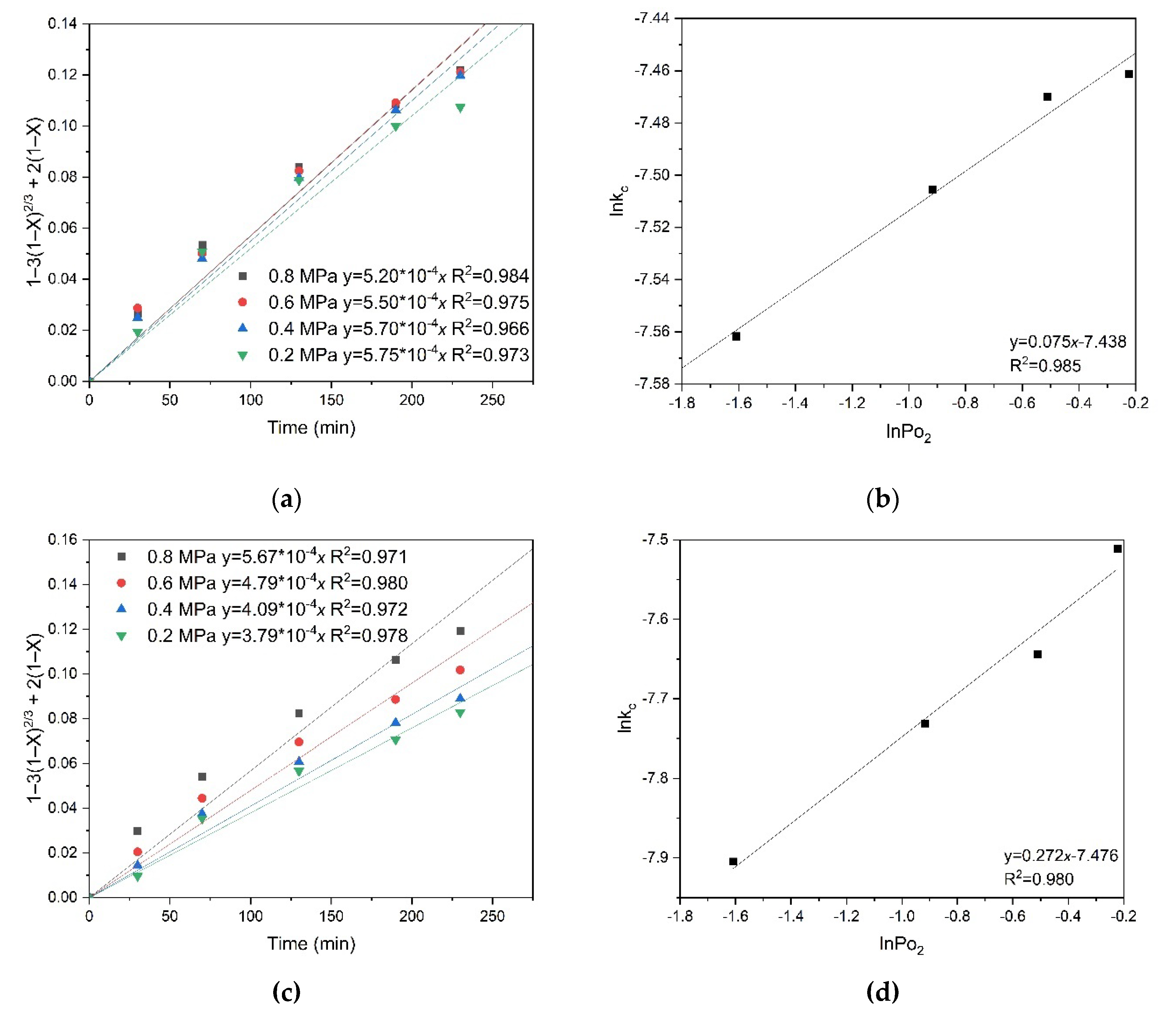

According to the data provided, Equation (1) describes the obtained dependences better than all others and has the highest correlation coefficients (R2) for the studied temperatures, which confirms that chalcopyrite and pyrite oxidation occurs in the intra-diffusion region. The process is limited by the diffusion of reagents through the solid reaction product layer.

To calculate the activation energy, graphs of the dependence of ln k

c vs. 1/

T were plotted, where k

c is the angular coefficient obtained from

Figure 8a,c. The coefficient

a calculated when constructing the straight line

y=

ax+

b in these coordinates determines the slope of the curve. According to Equation (20) derived from the Arrhenius law, the apparent activation energy was estimated from the slope of the straight line, which was 51.2 kJ/mol for chalcopyrite and 50.6 kJ/mol for pyrite, respectively.

Taking into account all the slope coefficients k

c, the dependence of lnk

c on 1/T was plotted and the apparent activation energy was calculated. As a result, an empirical partial order for oxygen pressure of 0.272 for pyrite and 0.075 for chalcopyrite, respectively, was obtained. These low empirical partial orders for oxygen pressure also confirm the internal diffusion limitations during the oxidation processes of pyrite and chalcopyrite (

Figure 9). Based on the values of the empirical partial orders, it can be concluded that oxygen pressure has virtually no effect on chalcopyrite dissolution, unlike pyrite, which may indicate the formation of a denser film of products on the surface of its particles and, as a consequence, more serious internal diffusion limitations.

Also, when plotting graphs of the dependences of ln

kc vs. ln(Cu)/ln(Fe)/ln(H

2SO

4), empirical partial orders for the initial concentration of copper (II) and iron (III) ions, and sulfuric acid were calculated for chalcopyrite and pyrite, where

kc is the slope calculated in a similar way. As a result, empirical partial orders 0.14, 0.12, and −0.31 were obtained for chalcopyrite by the initial concentration of copper (II) ions, iron (III) ions, and sulfuric acid, respectively. The negative effect of increasing the initial concentration of sulfuric acid, according to literature data, is associated with an increase in the oxidation state of chalcopyrite sulfide sulfur to elemental one (reaction 7) and screening of the surface of its particles [

30,

34,

35].

Similarly, the empirical partial orders for the initial concentration of copper (II) and iron (III) ions, and sulfuric acid were calculated for pyrite, which were 0.13, 0.14, and 0.27, respectively.

By substituting the Arrhenius equation into Equation (1), which describes the diffusion of reagents through the product layer, Equation can be obtained:

where

n is the empirical partial order for the component.

According to the previously obtained results, the following generalized equations can be derived for low-temperature pressure oxidation of chalcopyrite and pyrite (Equations (21) and (22), respectively):

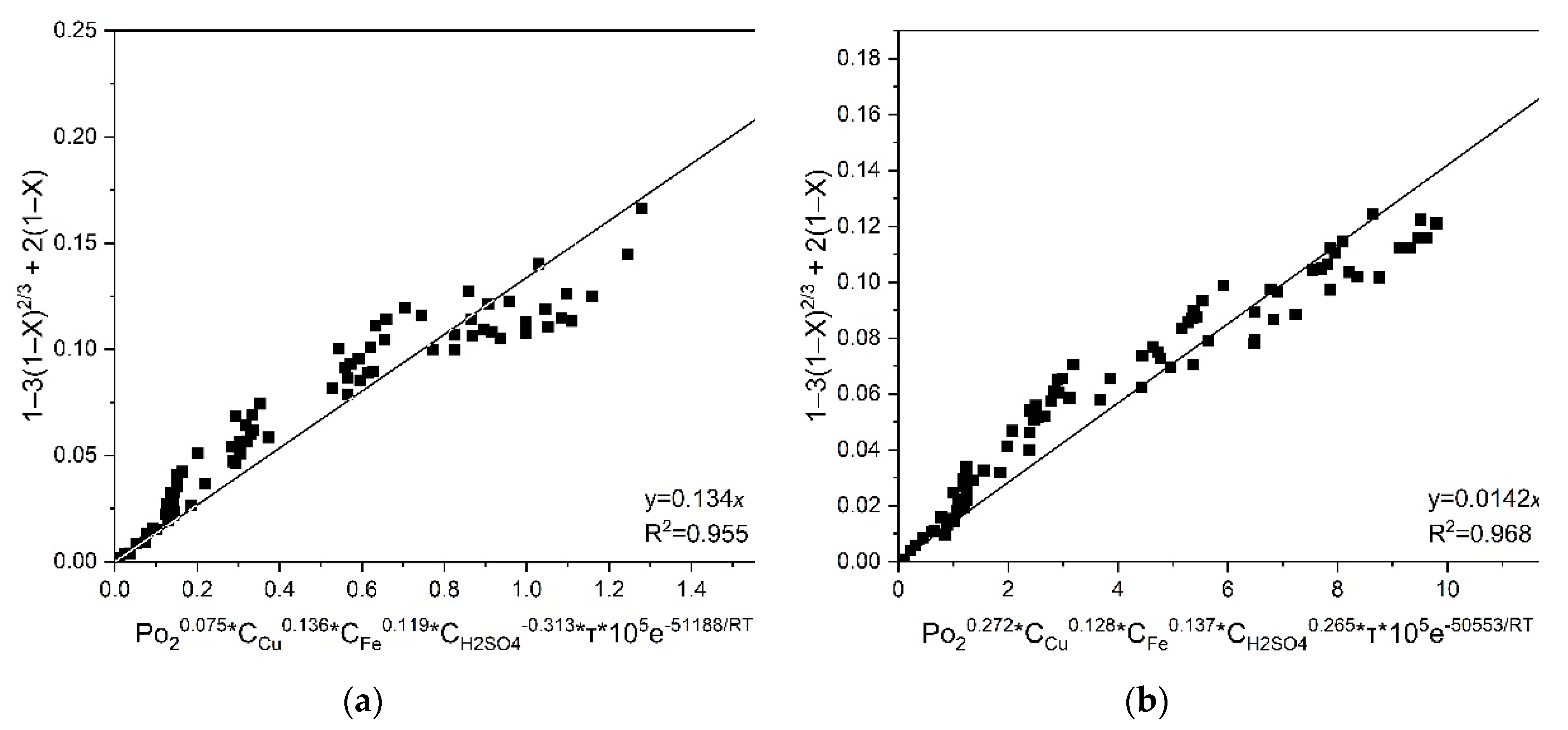

Then, graphs were plotted for all temperatures, initial concentrations of copper (II) and iron (III), sulfuric acid, which made it possible to estimate a fixed slope for chalcopyrite and pyrite

a = 0.134·10

5 and 0.142·10

5, respectively. The values of

a obtained by the graphical method and the corresponding value of the correlation coefficient R

2 are shown in

Figure 10. The obtained value of the coefficient

a corresponds to

k0.

According to the data obtained from

Figure 10, the general kinetic equations for chalcopyrite and pyrite have the following form (Eqs 23 and 24, respectively):

According to the data provided, the oxidation process of chalcopyrite and pyrite proceeds with intra-diffusion limitations. The process is limited by the diffusion of reagents through the solid reaction product layer. During low-temperature pressure oxidation, the surface of chalcopyrite and pyrite particles is passivated by an elemental sulfur film according to reactions 7, 14, thereby limiting the access of reagents to the reaction zone, which is also confirmed by other researchers [

28,

30,

34]. The low empirical partial orders for oxygen pressure also confirm intra-diffusion limitations during the oxidation processes of pyrite and chalcopyrite. The negative effect of increasing the initial concentration of sulfuric acid on chalcopyrite oxidation, according to literature data, is associated with an increase in the oxidation degree of sulfide sulfur to elemental one (reaction 8) and screening of the surface of its particles [

30].

3.2.2. Kinetic Analysis of Chalcopyrite and Pyrite Dissolution During Low-Temperature Pressure Leaching in a 1:1 Mixture

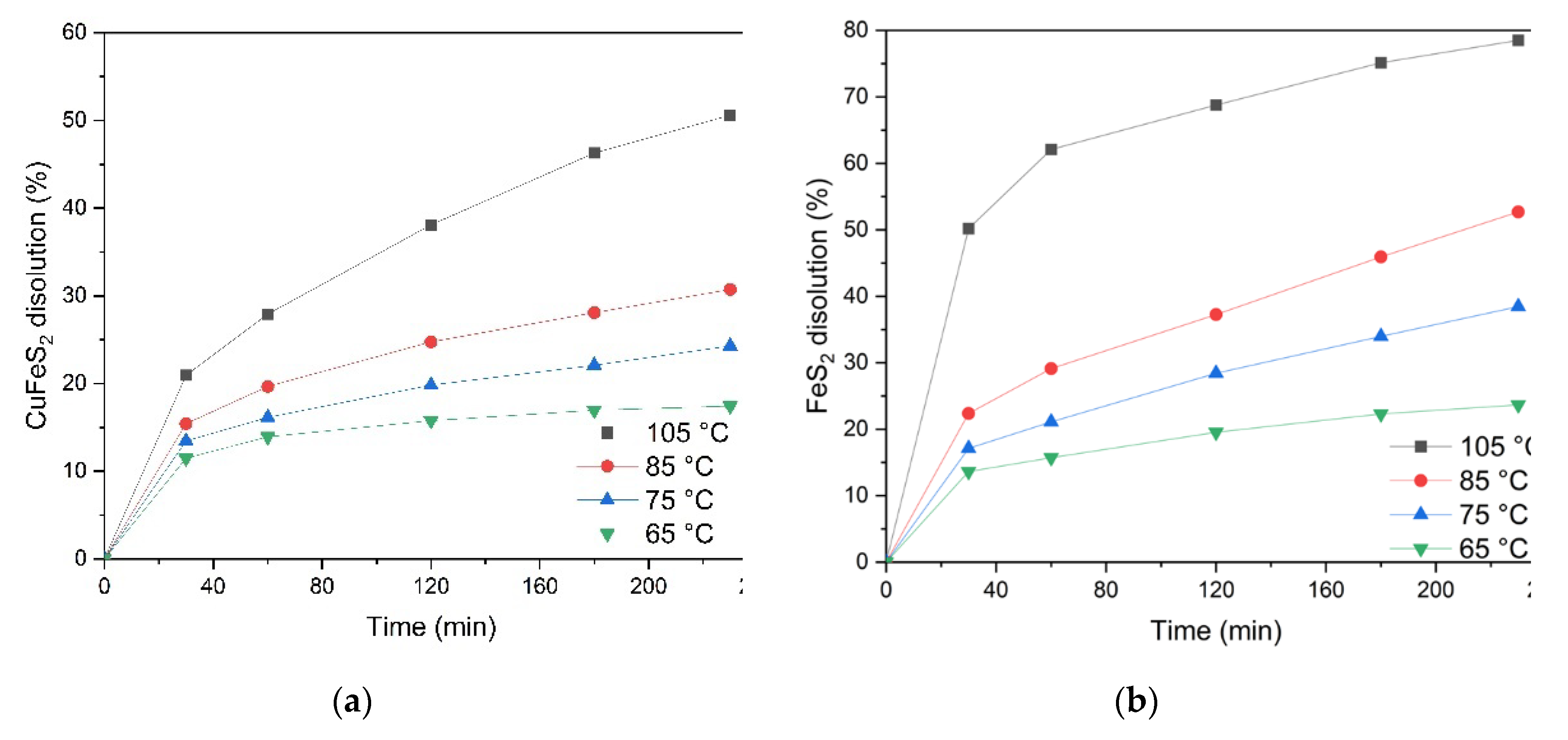

The effect of temperature on the process of low-temperature pressure oxidation of chalcopyrite and pyrite in a 1:1 mixture is shown in

Figure 11.

Based on the data presented in

Figure 11a, it can be concluded that temperature has a significant effect on the process of chalcopyrite dissolution throughout the time range studied. At a temperature of 110℃, up to 50.6% of chalcopyrite is oxidized in 230 min of the process. A decrease in temperature down to 60℃ leads to a decrease in the mineral dissolution degree down to 17.4% over a similar period of time.

Increasing the leaching time from 20 up to 240 min increases the chalcopyrite dissolution degree, while the positive effect of temperature is maintained throughout the entire oxidation time range.

According to the data presented in

Figure 11b, temperature has a significant effect on the process of pyrite dissolution during the time interval studied. E.g., at a temperature of 110°C, the pyrite oxidation degree reaches 78.5% after 230 min. Reducing the temperature down to 60°C reduces the dissolution degree down to 23.6% over the same period of time.

Increasing the duration of the leaching process from 20 up to 240 min leads to an increase in the pyrite dissolution degree. Increasing the temperature has a positive effect at all time stages of oxidation.

The correlation coefficients (R

2) obtained while modeling the process of chalcopyrite and pyrite leaching in a mixture with copper sulfate solutions using the SCM equations are given in

Table 4.

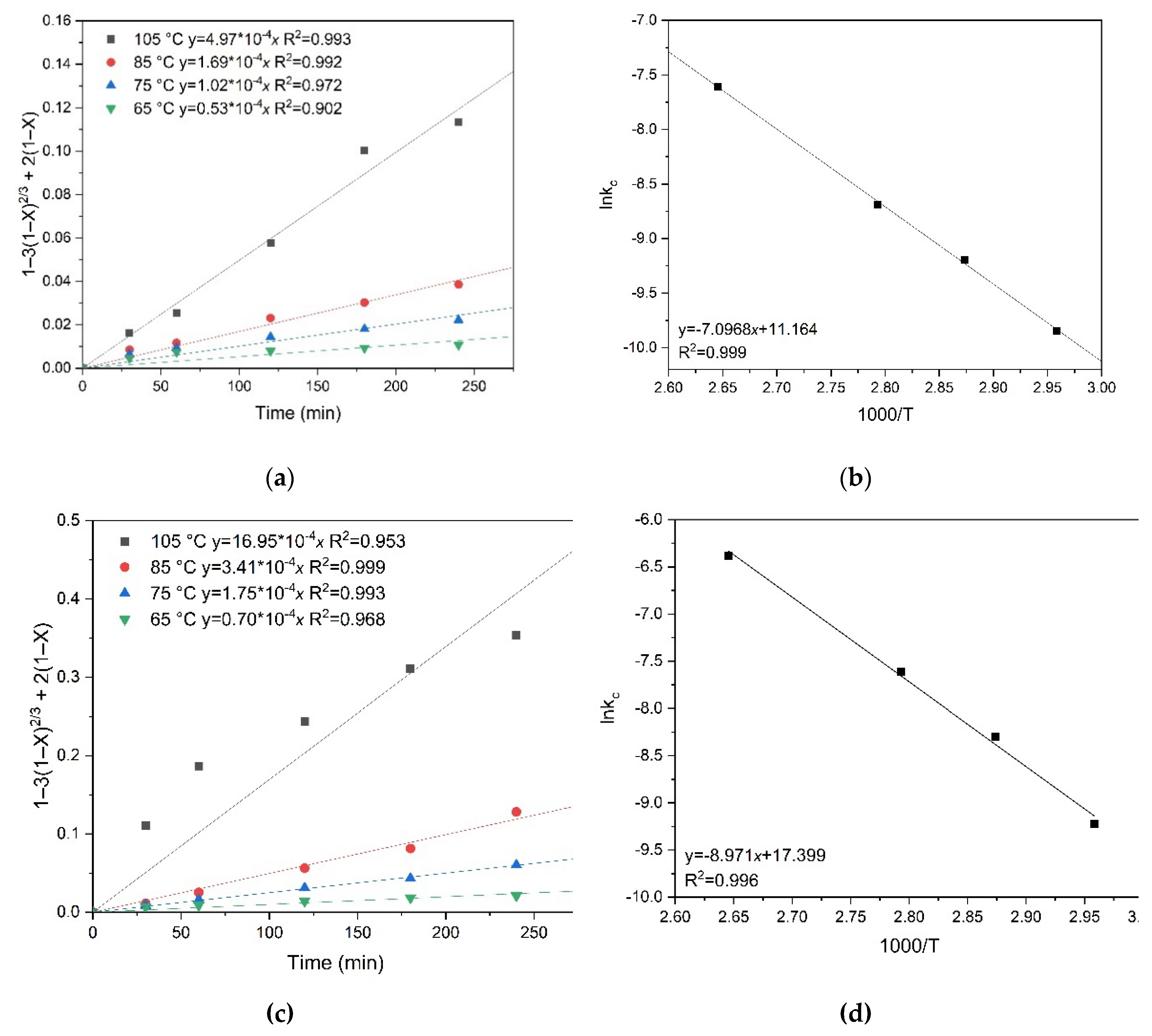

Based on the data presented, it can be concluded that Equation (1) most accurately describes the obtained dependences and has the highest correlation coefficients (R²) for the studied temperatures. This confirms that chalcopyrite and pyrite oxidation proceeds in the region of internal diffusion. The process is limited by the diffusion of reagents through the solid reaction product layer.

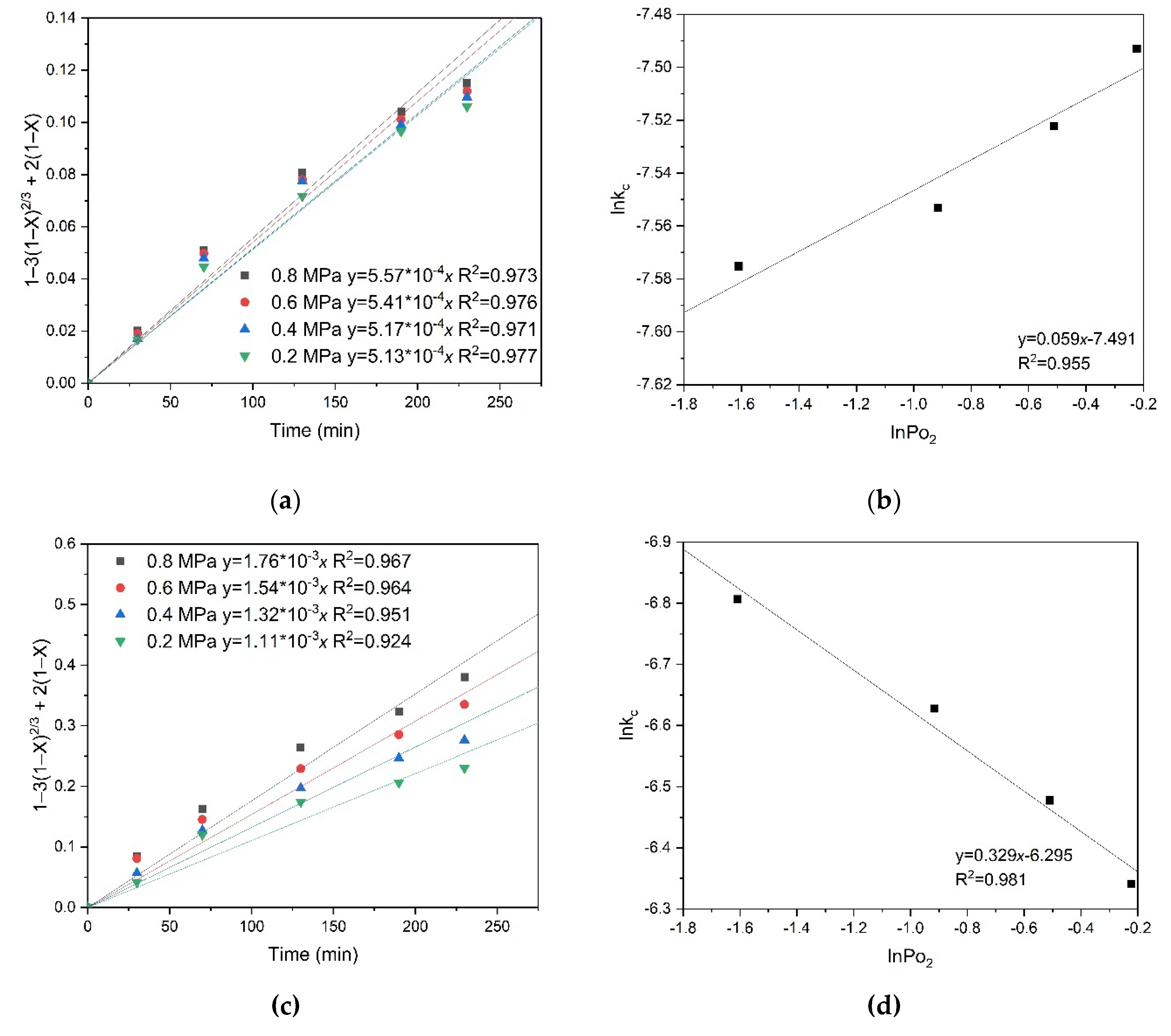

To calculate the activation energy, graphs were plotted for the dependence of the natural logarithm of the slope kc on the inverse temperature T, similar to the previous calculations.

The apparent activation energy was determined graphically (

Figure 12). It was 59.0 kJ/mol for chalcopyrite and 74.6 kJ/mol for pyrite, respectively.

Figure 13 shows the results of calculating the empirical partial orders for oxygen pressure. The following values were obtained: 0.330 for pyrite and 0.059 for chalcopyrite, respectively. These low empirical partial orders for oxygen pressure confirm intra-diffusion limitations during the oxidation of pyrite and chalcopyrite (

Figure 13). Based on the values of the empirical partial orders, it can be concluded that oxygen pressure has almost no effect on the dissolution of chalcopyrite, unlike pyrite. This may indicate the formation of a denser film of products on the surface of chalcopyrite particles and, as a consequence, more serious intra-diffusion limitations.

Empirical partial orders for low-temperature pressure leaching of chalcopyrite and pyrite in a 1:1 mixture were calculated by the initial concentration of copper (II) and iron (III) ions, and sulfuric acid. As a result, for chalcopyrite, empirical partial orders of 0.30, −0.17 and 0.36 were obtained for the initial concentration of copper (II) and iron (III) ions, and sulfuric acid, respectively. Unlike chalcopyrite monosulfide oxidation, in a mixture with pyrite, an increase in the initial concentration of iron (III) ions has a negative effect, which is possibly due to an increase in the oxidation state of sulfide sulfur to elemental one, which, in turn, screens the chalcopyrite surface of [

33].

The empirical partial orders for the initial concentration of copper (II) and iron (III) ions, and sulfuric acid were calculated for pyrite by the same method. The obtained values were 0.13, 0.14, and 0.27, respectively.

The empirical partial orders for the initial concentration of copper (II) and iron (III) ions, and sulfuric acid were calculated for pyrite in a similar way, which were 0.13, 0.14, and 0.27, respectively.

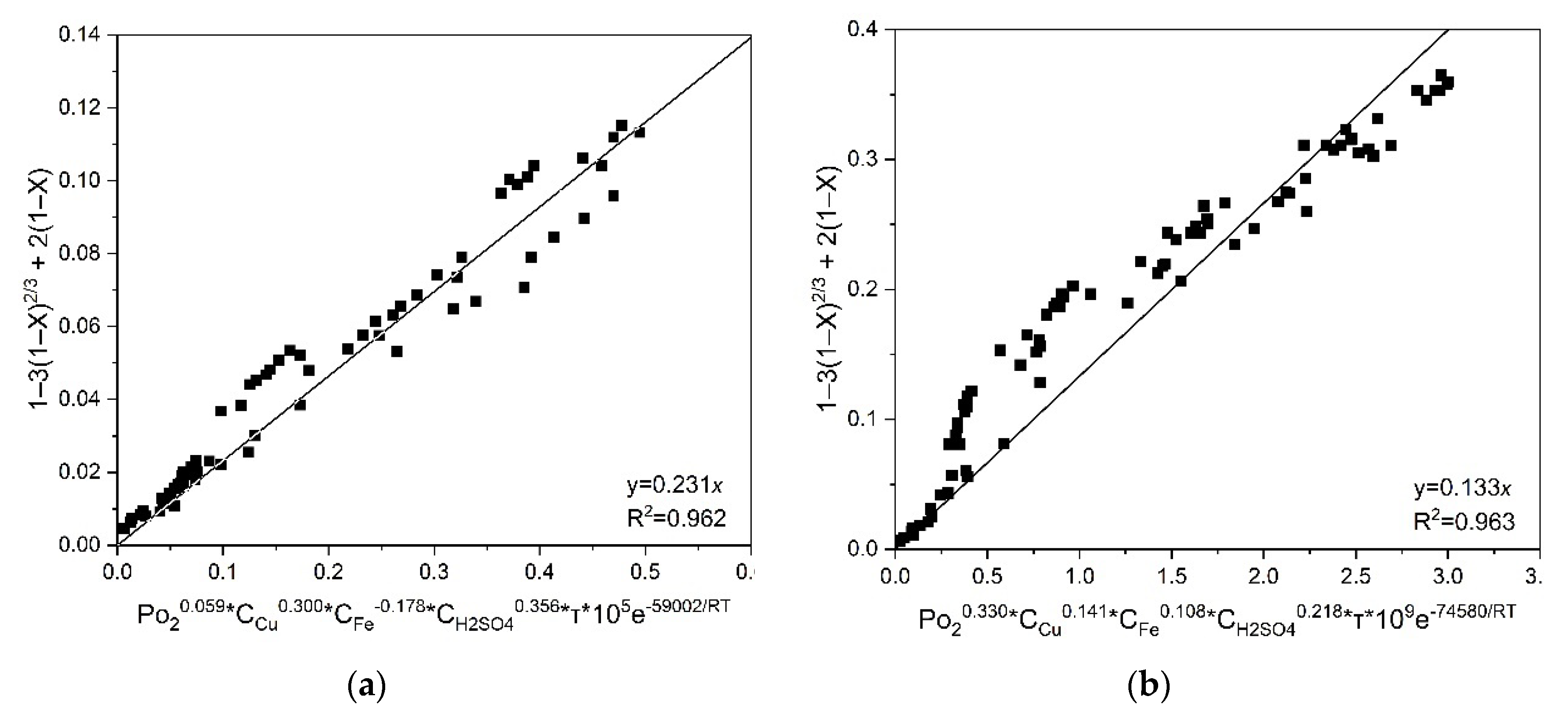

To derive generalized kinetic equations, the coefficients

ko were determined graphically, similarly as described earlier. Graphs were plotted for all temperatures, initial concentrations of copper (II) and iron (III) ions, and sulfuric acid. The values of

a obtained graphically and the corresponding value of the correlation coefficient R

2 are shown in

Figure 14.

According to the data in

Figure 14, the general kinetic equations for chalcopyrite and pyrite have the following form (Equations 25 and 26, respectively):.

According to the data provided, the oxidation process of chalcopyrite and pyrite in a 1:1 mixture proceeds with internal diffusion limitations. The process is limited by the diffusion of reagents through the solid reaction product layer. During low-temperature pressure oxidation, the surface of chalcopyrite and pyrite particles is passivated by a film of elemental sulfur according to reactions 7,13, thereby limiting the access of reagents to the reaction zone, which is also confirmed by other researchers [

34].

The initial concentration of sulfuric acid in the process of chalcopyrite dissolution not in the mixture had a pronounced negative effect with an empirical reaction partial order of −0.313. Addition of pyrite in a ratio of 1:1 contributed to a change in the empirical partial order to a positive one 0.356. The change in the nature of the influence of the initial concentration of sulfuric acid on the behavior of chalcopyrite upon the addition of pyrite indicates their interaction in the mixture and a change in the oxidation mechanism.

When dissolving chalcopyrite monosulfide, an increase in the initial concentration of iron (III) ions had a positive effect with an empirical partial order of 0.12. When adding pyrite in a ratio of 1:1, an increase in the concentration of iron (III) ions has a negative effect, and the empirical partial order changes to −0.18, which is possibly associated with an increase in the oxidation state of sulfide sulfur to elemental sulfur, screening the chalcopyrite surface [

30].

In the case of pyrite, an increase in the initial concentrations of copper (II) and iron (III) ions, and sulfuric acid had a positive effect on pyrite dissolution both in a mixture with chalcopyrite and without its addition.

Analysis of the data allows us to conclude that the oxidation mechanism of chalcopyrite and pyrite in their mixture has changed. This is evidenced by the increase in the activation energy values: from 51.2 up to 59.0 kJ/mol for chalcopyrite and from 50.6 up to 74.6 kJ/mol for pyrite, respectively. This indicates an increase in the effect of temperature on the oxidation process of minerals in their 1:1 mixture. This effect is especially noticeable for pyrite, namely: with the addition of chalcopyrite, the activation energy increases by 24 kJ/mol and reaches a value of 74.6 kJ/mol. The greatest positive effect of temperature was observed in the initial period of the mineral oxidation process: during the first 30 minutes (Figs 7 and 11). The change in the nature of the curves for pyrite was more pronounced. For chalcopyrite, the addition of pyrite had a noticeable effect only in the first 30 minutes of dissolution. After this, the graphs almost reach a plateau, whereas during the oxidation of an individual sulfide, the dissolution degree increases throughout the process. The total dissolution degree of chalcopyrite in its mixture with pyrite decreases over the entire temperature range in 230 min.

3.3. Analysis of the Cakes from Low-Temperature Pressure Dissolution of Chalcopyrite and Pyrite

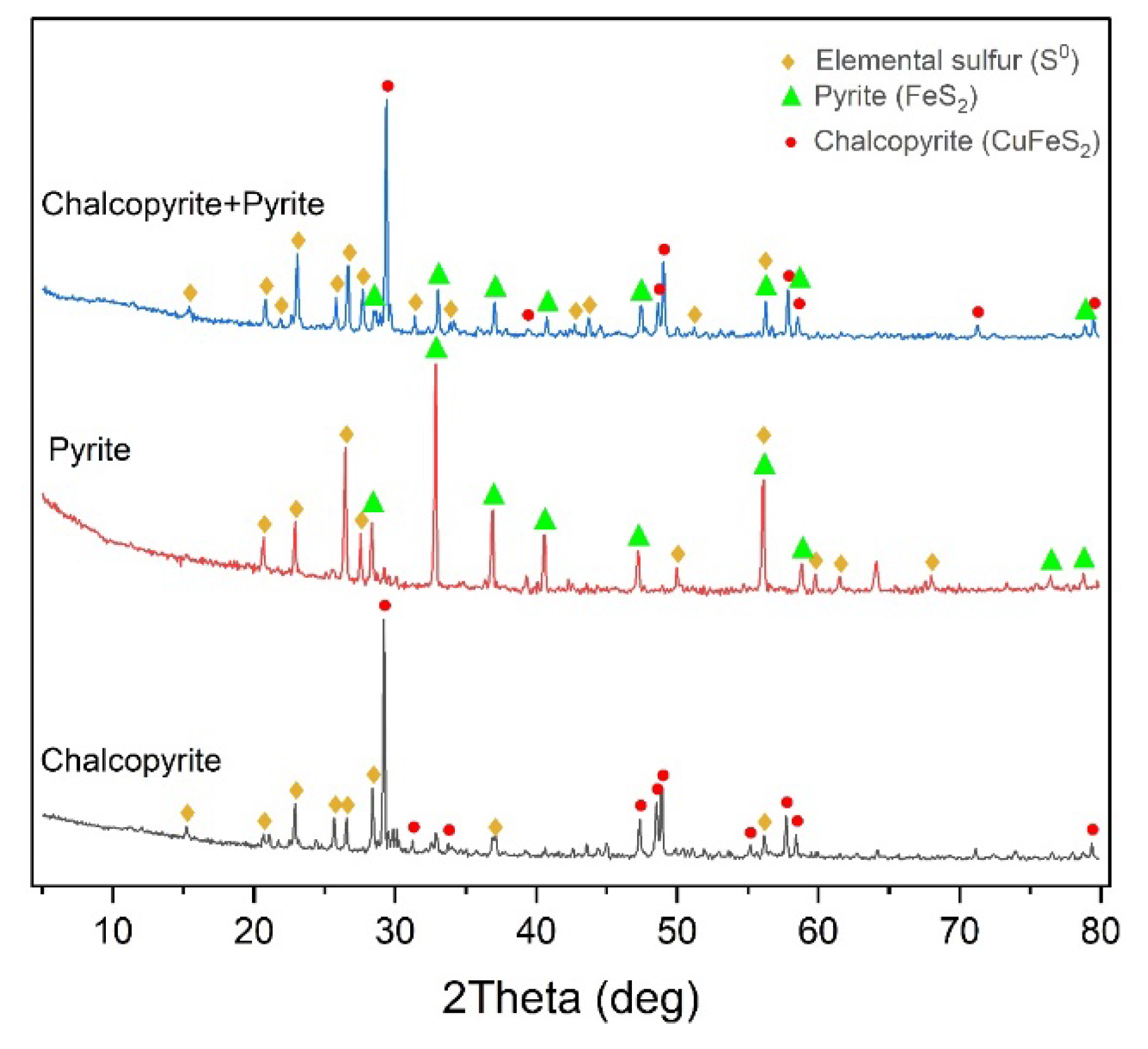

X-ray phase analysis of the cakes after low-temperature pressure oxidation of chalcopyrite and pyrite and their mixture in a 1:1 ratio are shown in

Figure 15.

According to the data presented in

Figure 15, all cakes contain under-oxidized minerals and elemental sulfur. Its content in the cakes is 24.8 % for chalcopyrite, 11.3 % for pyrite and 19.2 % for their mixture. It can also be noted that the pyrite peaks in the X-ray diffraction pattern of the leaching cake of the mineral mixture have a much lower intensity than the chalcopyrite peaks.

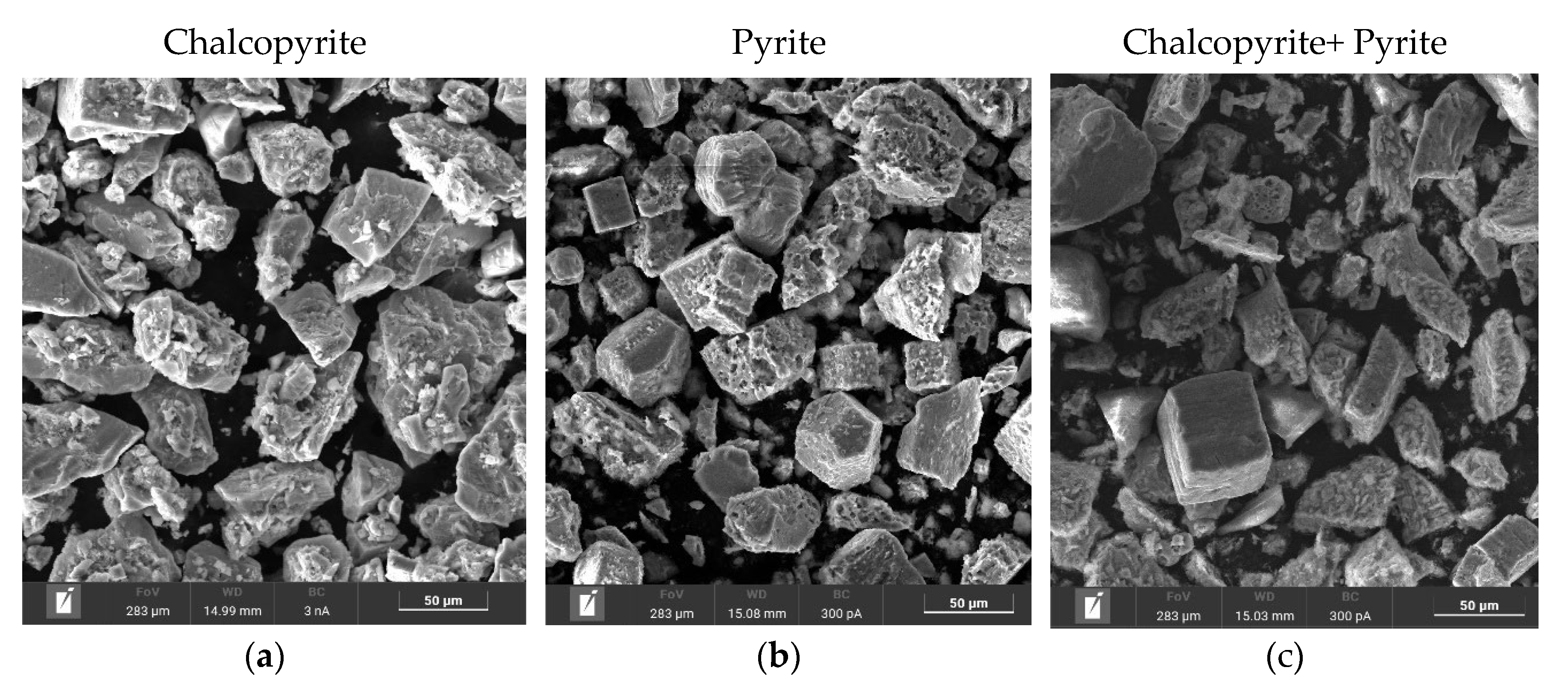

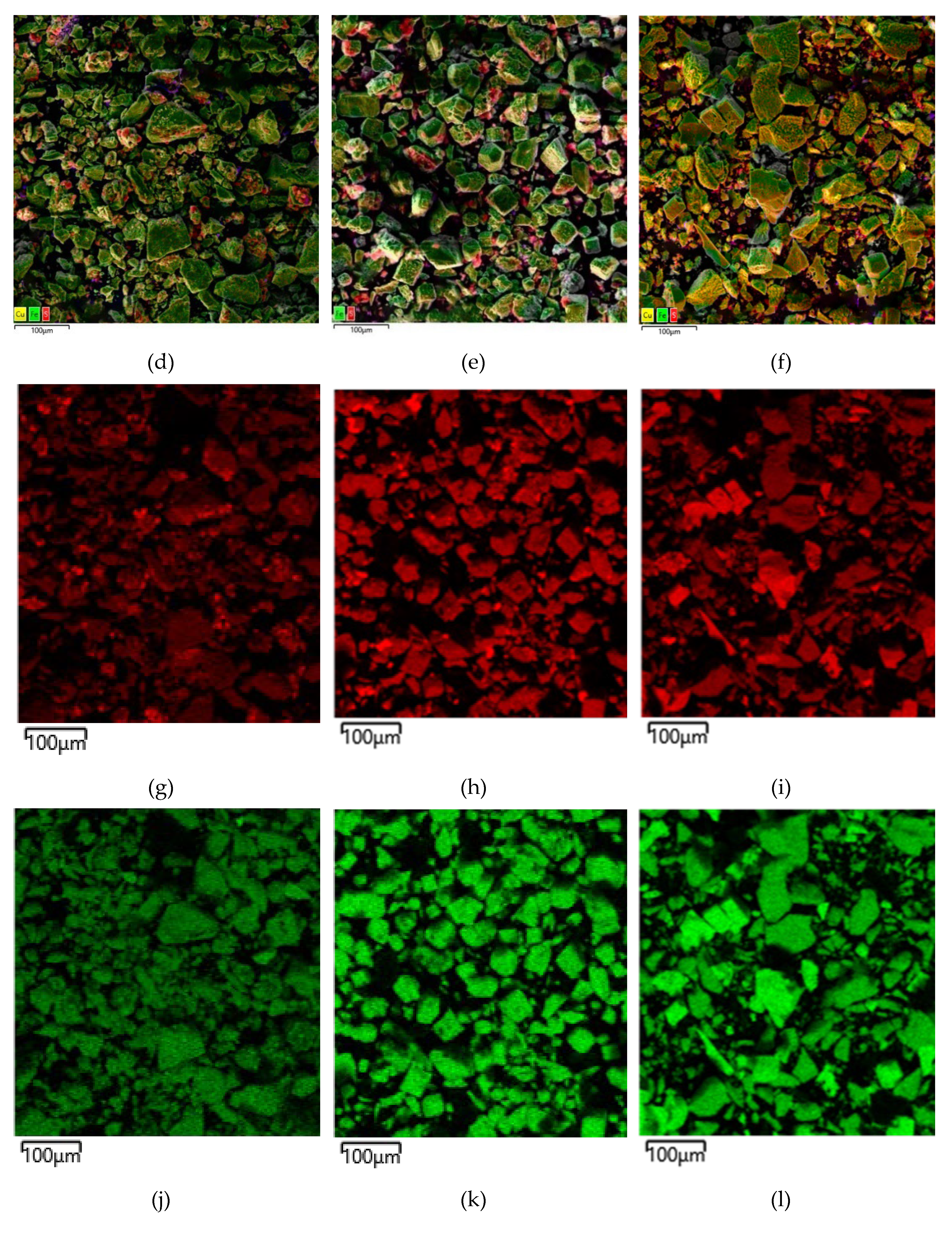

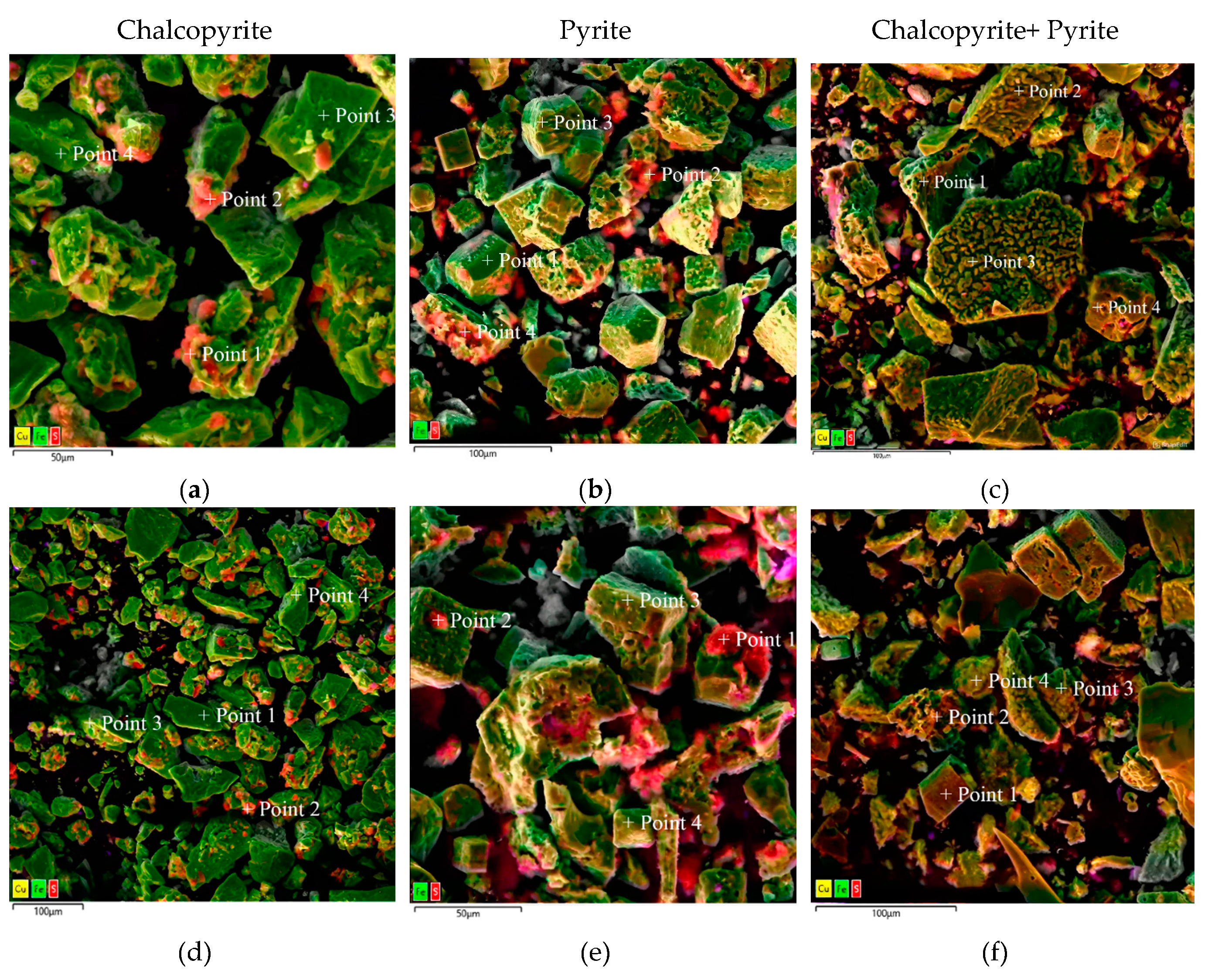

Micrographs and EDX mapping for the low-temperature oxidation cakes of chalcopyrite, pyrite and their mixture in a 1:1 ratio are shown in

Figure 16. They were obtained at

t = 100°C, P

O2 = 0.8 MPa, [H

2SO

4] = 50 g/L, [Cu

2+] = 3 g/L, [Fe

3+] = 10 g/L, and duration 230 min.

According to the data presented in

Figure 16a,d, after low-temperature pressure leaching, chalcopyrite particles are characterized by both smooth and loose, non-uniform surfaces. In

Figure 16d, the red zones correspond to the distribution of sulfur, the green zones correspond to iron, and the yellow zones correspond to copper (

Figure 16g,j,m). Chalcopyrite is represented by a combination of these zones. The presence of elemental sulfur is also noticeable as bright red growths on the chalcopyrite surface

Figure 16d. The distribution of sulfur on the chalcopyrite surface is non-uniform and leads to the formation of conglomerates.

According to the data presented in

Figure 16 b,e, pyrite particles after low-temperature pressure leaching have both a smooth and a loose, non-uniform surface. Small conglomerates were found on the surface of rectangular particles (

Figure 16 b,e). In

Figure 16 e,h,k the red zones correspond to the distribution of sulfur, and the green zones correspond to iron. A mixture of these zones means pyrite. It is evident from

Figure 16e that elemental sulfur covers the surface of pyrite as bright red growths. This is especially noticeable on particles with a developed surface. Small particles consist almost entirely of elemental sulfur. On large grains with a smooth surface, elemental sulfur is formed in uneven areas.

From

Figure 16 c,f it is clear that the cake is represented by two types of particles with different shapes. The first type, pyrite, has a smooth surface in places with pits and caverns, eaten away during the oxidation reaction (

Figure 16 c,f). The second type, chalcopyrite, is represented by particles with a non-uniform surface with pronounced defects which inclusions of various shapes have formed on (

Figure 16 c,f). At the same time, unlike the dissolution of individual minerals, there are no conglomerates on the surface of the particles (

Figure 16 c,f). Elemental sulfur was distributed more evenly in the case of leaching of a mixture of pyrite and chalcopyrite. The red zones in correspond to the distribution of sulfur, the green zones are responsible for iron, the yellow ones for copper (

Figure 16 i,l,n).

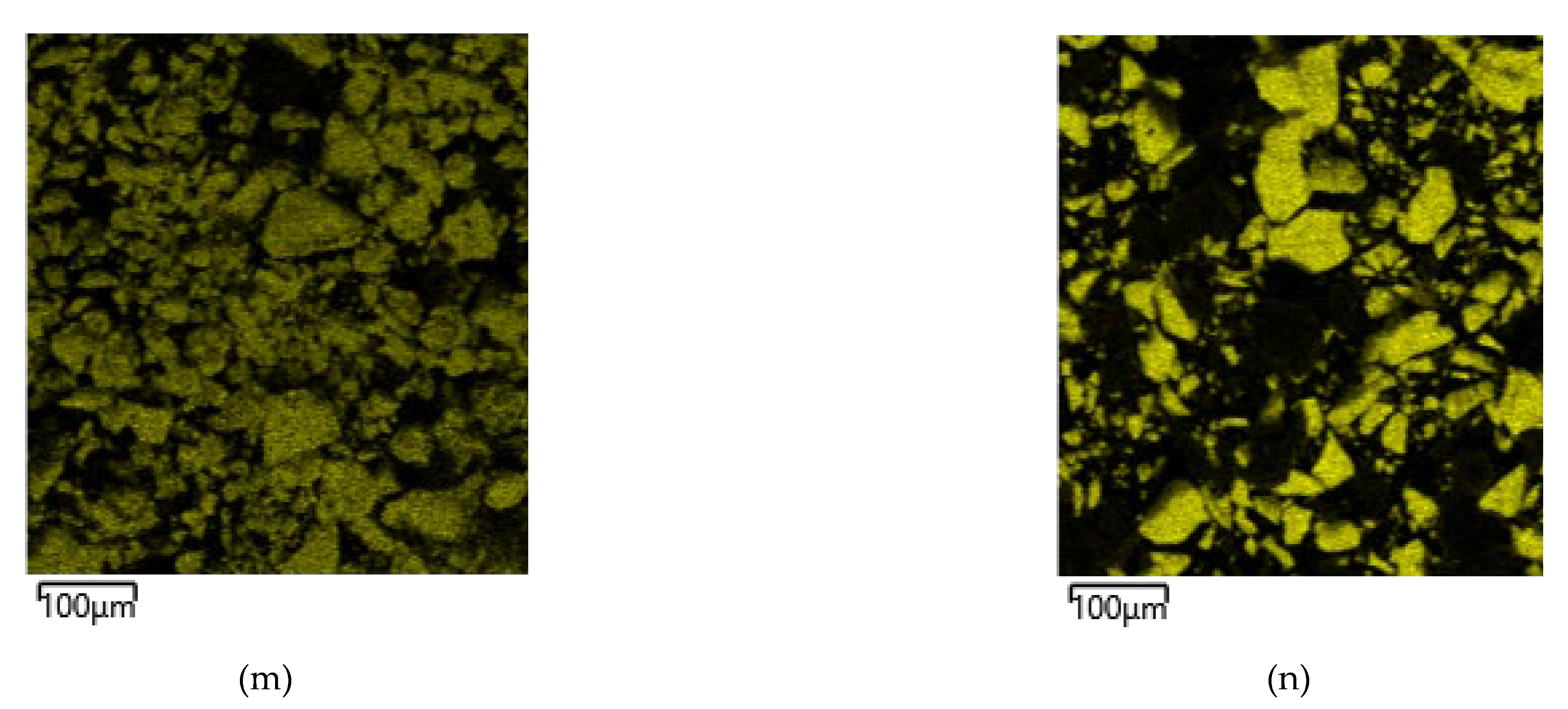

Micrographs of the cakes after low-temperature pressure oxidation of individual minerals and their mixture in a 1:1 ratio with composition determination points are shown in

Figure 17, the element contents are presented in

Table 5.

When oxidizing chalcopyrite not in a mixture, elemental sulfur conglomerates were also found on its surface (

Figure 17a,d). The total content of elemental sulfur on the surface is 7.4 – 73.6 % (

Figure 17c point 2,3, рисунoк 17f point 4). When oxidizing chalcopyrite in its mixture with pyrite, its surface contains np conglomerates, but has pronounced defects and inclusions of various shapes. Elemental sulfur is also evenly distributed over all particles, and its total content decreases up to 5.1-9.4 % (

Figure 17c point 2,3,

Figure 17f point 4).

The obtained data show that during low-temperature pressure leaching of pyrite not in a mixture, elemental sulfur conglomerates are formed on the surface of the particles. The total content of elemental sulfur on its surface is 2.3-72.6 % (

Figure 17 b,e). When pyrite is oxidized in its mixture with chalcopyrite, its surface contains no conglomerates. Elemental sulfur is distributed evenly over all particles and its total content decreases down to 0.1 – 1.9 % (

Figure 17c point 1,4,

Figure 17f point 1 - 3).

According to the data obtained from our kinetic analysis of low-temperature pressure oxidation of chalcopyrite and pyrite, it can be concluded that the increase in the dissolution degree of pyrite with the addition of chalcopyrite is not associated with an increase in the concentration of copper (II) and iron (III) ions during oxidation, since their effect on the degree of opening of minerals was insignificant, including for the mixture. The obtained empirical partial orders confirm this, their values almost do not change during oxidation in a mixture or separately.

According to literature data, pyrite may form galvanic bonds with other sulfides exhibiting semiconductor properties. It is an effective source of an alternative surface for oxidation reactions in electrochemical contact. Its oxidation occurs almost without the formation of elemental sulfur, especially in the initial period of the process [

37].

The positive effect on the oxidation degree of pyrite in its mixture with chalcopyrite can be explained by the formation of an electrochemical bond between the minerals. This phenomenon is widely described by other researchers. When an electrochemical pair is formed between pyrite and chalcopyrite in the presence of strong oxidizers (oxygen, iron (III) ions), dissolution is limited by the transfer of electrons through the passivating film between the minerals [

38], therefore, unlike the Galvanox™ process, pyrite is also oxidized under low-temperature pressure oxidation conditions[

39].

This theory is confirmed by the change in the oxidation mechanism of chalcopyrite and pyrite in their mixture. This is indicated by the increase in the activation energy values during oxidation of minerals in the mixture: from 51.2 up to 59.0 kJ/mol for chalcopyrite and from 50.6 up to 74.6 kJ/mol for pyrite. This means that the effect of temperature increases during oxidation of minerals in the mixture, which is observed in the initial period of the process, during the first 30 minutes (Figs 7 and 11). In this case, the change in the nature of the curves is more pronounced for pyrite. For chalcopyrite, the addition of pyrite has a positive effect in the first 30 minutes of dissolution only, and then it has a negative effect, since the curves almost reach a plateau, whereas during oxidation of individual sulfides, the dissolution degree increases during the entire duration. The total oxidation degree of chalcopyrite in the mixture decreases for the entire temperature range over 230 min.

The presence of such a bond is also indicated by the change in the effect of the initial concentration of sulfuric acid and iron (III) ions on the oxidation state of chalcopyrite in its mixture with pyrite, which follows from the obtained values of empirical partial orders.

The positive effect of the chalcopyrite additive is associated with a decrease in elemental sulfur formation on the pyrite surface, which is confirmed by the data of microphotographs and EDX mapping. The elemental sulfur content decreases up to 5.1-9.4 % on the chalcopyrite surface, while for pyrite its content decreases up to 0.1 – 1.9 %. The elemental sulfur distribution on minerals becomes more uniform with no formation of conglomerates, which also confirms their interaction with each other.

In the initial period, pyrite and chalcopyrite oxidation occurs at the maximum rate. Then chalcopyrite dissolution slows down sharply due to the passivation of its surface with elemental sulfur. The oxidation rate of pyrite also begins to slow down, but not as sharply as in the case of oxidation with no addition of chalcopyrite. During this period, its surface also begins to be passivated with elemental sulfur.