1. Introduction

Earth’s surface is covered by 71% of water, 97% ocean water (Perlman, 2016). Additionally, 99% of the ocean floor and 95% of the oceans in the world remain uncharted (Board & Council, 2003). Marine vehicles have garnered increasing attention in the corporate world and academic circles because they promise to deliver secure and economically efficient substitutes for human involvement in marine engineering endeavors. Dynamic positioning control of marine vehicles is widely used in underwater monitoring, maintenance, operation, rescue, aquaculture, and scientific investigation. Small Autonomous Surface/Underwater Vehicles (S-ASUV) are gradually attracting attention from related fields due to their small size, low energy consumption, and flexible motion (Ahmed et al.,2023; Yang et al., 2024).

The motivation for this study arises from complex challenges associated with achieving accurate and fast dynamic positioning for autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) in unpredictable underwater environments. The other inspiration for this work stems from addressing the nonlinearities, intricate hydrodynamic coefficients, and model uncertainties inherent in AUVs (Cui et al.,2016). Traditionally, DP functionality refers to a vehicle's ability to achieve and maintain a desired position and orientation solely through active thrusters. The recent study tends to incorporate all low-speed movement in its definition. Many control methods have been proposed to tackle DP problems, such as classical proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control, modern model predictive control (MPC), etc.(Cui et al.,2017; Veksler et al.,2016; Zarkasi et al.,2020). The DP control strategy using MPC attracts the increased attention of researchers, which integrates positioning control and thrust allocation into a single MPC algorithm, aiming for a theoretically near-optimal controller output.

MPC is a closed-loop optimal control strategy that offers a systematic approach to handle input and state constraints. These constraints, arising from physical or security restrictions, are typical in all control systems. MPC stands out among control methods because it can explicitly encompass constraints while undergoing the controller design process due to its optimization-based feature in the time domain (Li & Shi, 2017; Mayne et al., 2000). One major challenge in MPC control design is to ensure closed-loop stability, especially for nonlinear systems like AUVs. It is important to note that closed-loop system stability is not solely dependent on optimality. According to traditional MPC design guidelines, additional terminal constraints and local linearization are required to create a local stabilizing control law for closed-loop stability, as Shen et al. (2016) demonstrated. Consequently, this approach introduces significant conservatism, and only local stability can be guaranteed. According to a study by Zheng et al. (2020), two robust DP approaches are proposed for autonomous surface vessels, addressing scenarios with full measurable states and partial states available with measurement errors. However, their reliance on tube-based MPC may lead to computational complexity and challenges in real-time implementation, particularly for systems with three-dimensional state spaces and fast dynamics. Additionally, the performance of the output feedback robust DP controller may be limited by the accuracy of state estimation using the Luenberger observer, especially in scenarios with significant measurement errors.

Besides the MPC DP method, some other approaches have been investigated recently. Li et al. (2022) addressed the finite-time adaptive dynamic positioning control problem for unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) under challenging conditions, such as time-varying disturbances, unknown model parameters, and input saturation. Using a fuzzy supervisory approach, they introduced a model-free prescribed performance DP controller and a saturated-command-deviation-based compensation law. Despite its effectiveness in specific scenarios, however, it may suffer from limitations in handling complex dynamics and uncertainties. Fu et al. (2023) presented a discrete-time adaptive predictive sliding mode trajectory tracking control strategy for dynamic positioning, addressing challenges such as model uncertainties, environmental disturbances, and input saturation. Stability analysis confirms system stability, with S-ASUV’s digital experiment results verifying its effectiveness. However, its complexity and reliance on disturbance observers may pose implementation challenges and sensitivity to model inaccuracies.

To address the problem of ordinary MPC, some new research results involving two-dimensional (2D) trajectory tracking have been achieved for AUVs. Shen et al. (2017) built a 2D dynamic model of trajectory tracking with position x, y, and heading . Based on the 2D dynamic model, the study proposed a Lyapunov-based model predictive control (LMPC) scheme with a PD secondary controller. It connects the state-of-the-art optimization technique and the conventional PID control theory, enabling a direct integration of online optimization into the control system design to improve control performance. Nevertheless, the proposed scheme solely utilized the PD law, not fully exerting PID's capabilities. For the nonlinear control system model, a new LMPC strategy was developed for an underwater vehicle's two-dimensional(2D) trajectory tracking control (Shen et al., 2018). This framework addresses practical constraints such as actuator saturation and tackles the thrust allocation subproblem concurrently with controller design. Closed-loop stability is theoretically guaranteed by incorporating a nonlinear backstepping tracking secondary control law and a contraction constraint. The above two modern control strategies were elaborately summarized in (Shi et al., 2023). But the use of backstepping control law is limited in practicality due to the inevitable but dramatic model uncertainties of AUVs. The LMPC has shown its attractive virtue in trajectory tracking for AUVs. Unfortunately, those studies are constrained to 2D trajectory tracking.

To sum up, on the one hand, it is well-known that PID is a widely recognized control scheme for the DP problem for ships, while MPC attracts increased attention in the field of DP control because of its online receding optimization and robustness. The combination of MPC and PID would be a very perfect methodology for modern control solutions to the DP problem. On the other hand, improving the control response’s rapidity and robustness is very significant for the DP problem of marine vehicles in complex dynamic environments. However, the DP control problem in 3D space remains to be investigated comprehensively and becomes a challenging research topic.

To effectively handle the chronic restrictions of the DP control mentioned above, this study proposes a novel LBMPC DP method to materialize both the position and pose control in 3D space. According to the authors’ knowledge, the 3D DP problem with 3D position and 3D pose control of AUVs, especially S-ASUVs, was studied very little before. Unlike the mentioned LMPC techniques, the LBMPC method first uses the multi-variable PID controller as the secondary law, significantly refining the accuracy and rapidity of the DP control responses. The designed PID secondary law also introduces the disturbance and model uncertainties, providing a theoretical explanation for the ability to resist disturbances and uncertainties. The proposed strategy uses a predictive model employing the multi-variable PID secondary law to optimize three-dimensional DP trajectories over a future time horizon into the multi-rotor-driven system of S-ASUV. Another significant advantage of LBMPC is its capability to directly integrate the thrust distribution from the propellers into the optimal 3D DP control problem, eliminating the necessity for a TA subproblem. 3D dynamic positioning control is more complex due to managing six degrees of freedom (surge, sway, heave, roll, pitch, yaw) compared to four DOFs (surge, sway, roll, and yaw) in 2D where one of the DOFs considered is mainly neglected and only three are fully utilized. Coupling effects between different degrees of freedom are more pronounced, requiring sophisticated algorithms. Environmental disturbances, such as currents, waves, and wind, affect the vehicle in multiple directions simultaneously. Accurate 3D positioning also necessitates the integration of advanced sensors and actuators capable of providing thrust in multiple directions. Additionally, the dynamics of an S-ASUV operating in 3D space are inherently nonlinear and more challenging to model accurately, making the control problem significantly more complex.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- 1)

A new 3D dynamic positioning control methodology, i.e., LBMPC, is proposed for S-ASUV, providing a useful solution to the challenging problem of 3D DP control. A multi-variable PID controller is first used in the secondary law and synchronously considers external disturbances and uncertainties, performing dramatic advantages over the current approaches, including both classical and modern techniques.

- 2)

Both the recursive feasibility of the designed LBMPC algorithm and closed-loop system stability are proved rigorously. The dynamic positioning control system using LBMPC can guarantee the continuous stability of the required equilibrium point.

- 3)

A series of experiments using S-ASUV’s model under diverse conditions demonstrate the proposed method's advantages over existing controllers, affirming its robustness and rapidity for precise 3D dynamic positioning in complex environments.

The remaining parts of this paper are arranged as follows.

Section 2 presents the S-ASUV system model used.

Section 3 describes the LBMPC control strategy, examining the LBMPC design and stability analysis combined with an introduced PID secondary controller. The results are presented in

Section 4, and the research is concluded in

Section 5.

2. S-ASUV Modeling

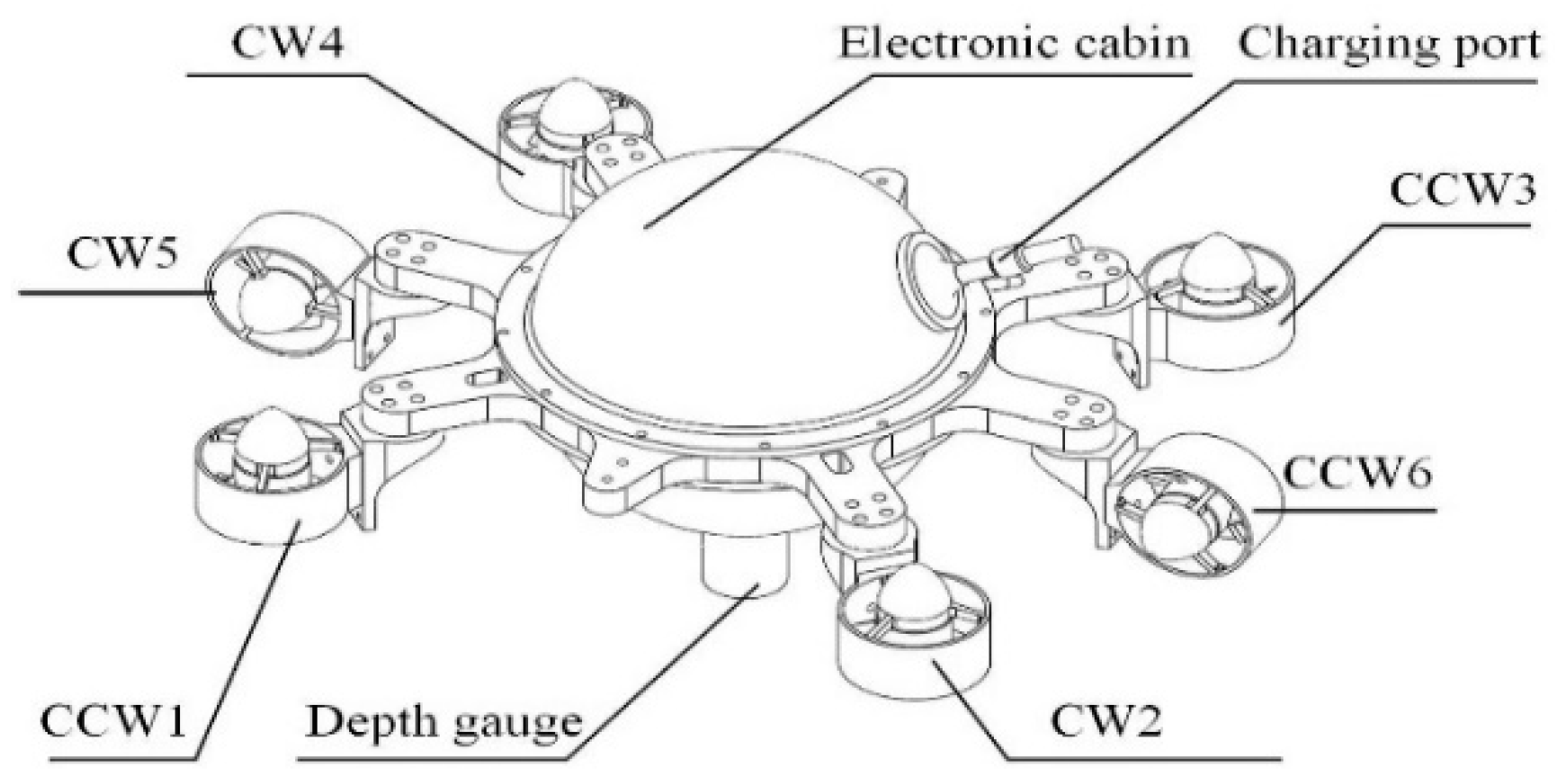

The structure of the S-ASUV described in this paper is shown in

Figure 1, which comprises a spherical module and six propellers. The main physical parameters of the S-ASUV are shown in

Table 3, where

m and

γ are the mass and radius, respectively,

l is the distance between the rotation axis and the propellers,

B is the buoyancy,

G is the force of gravity, (

xg,

yg,

zg) is the coordinates of the center of gravity, and (

Ix,

Iy,

Iz) is the moment of inertia.

2.1. Frames of Reference

The dynamic models of AUVs are widely recognized for their non-linear, strongly coupled, time-varying nature and Multiple Input Multiple Output (MIMO) system attributes. These models encompass various hydrodynamic loads that are rarely constant over time. These loads are contingent on factors like speed, acceleration, and the size of the S-ASUV represented through hydrodynamic coefficients. These coefficients, detailed in

Table 1, comprise the added mass and drag coefficients, delineating the vehicle's dynamic behavior during acceleration and uniform motion, respectively (Fossen, 2011).

Table 2 shows the S-ASUV 's force/torque, linear/angular velocity, and position/Euler angle in six DOFs.

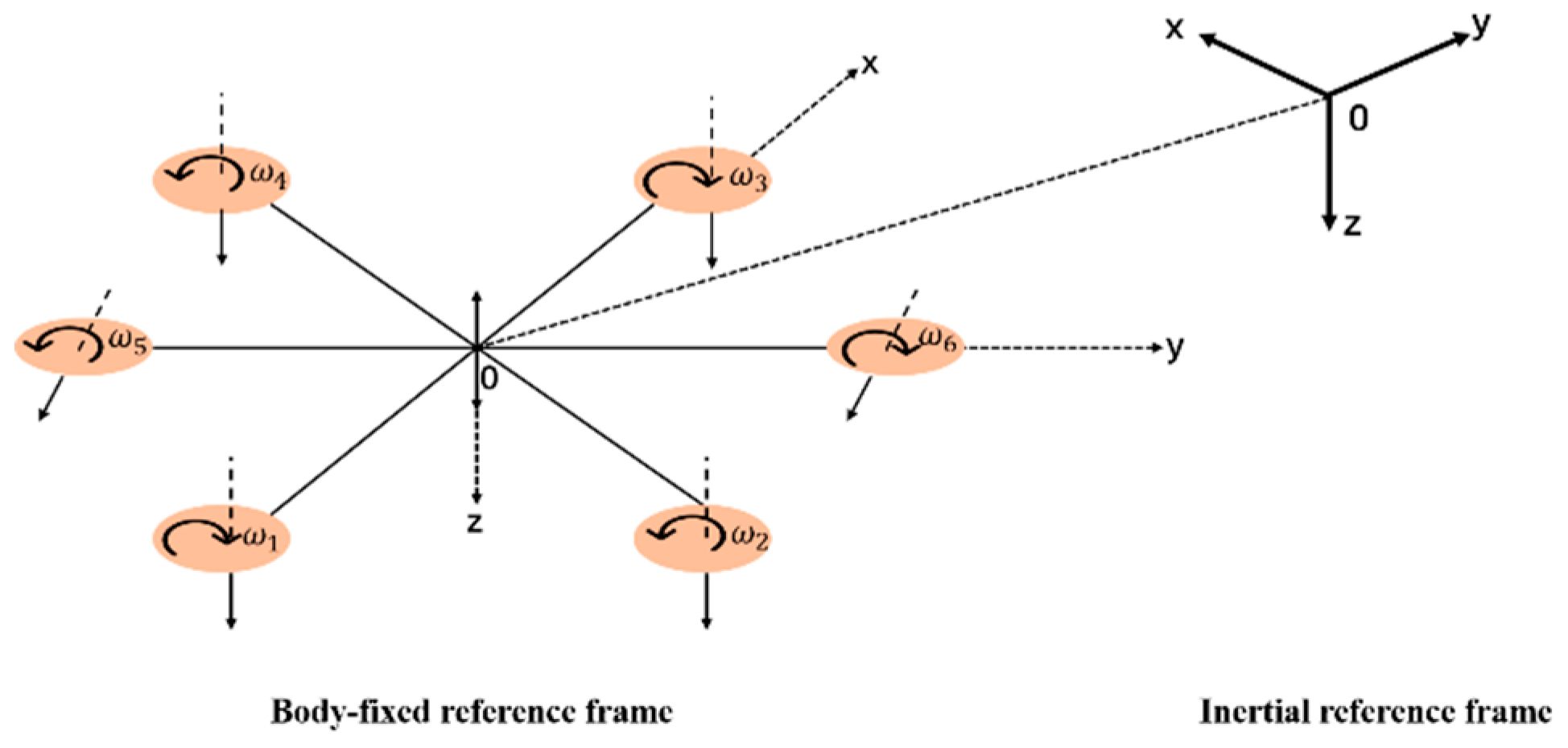

To facilitate mathematical analysis, we establish two frames of reference. The body reference frame (BRF) is attached to the vehicle and aligned with its center of gravity (CG). Using this configuration, we can analyze the vehicle's movement regarding the BRF relative to an inertial reference frame (IRF) that tracks the vehicle's position and orientation globally. The thrusters are arranged in a cross shape, where the first and third propellers move clockwise with angular velocities of ω1 and ω3, generating thrusts downward. In contrast, the second and fourth propellers make the counterclockwise motion with angular velocities of ω2 and ω4, generating downward thrusts.

Figure 2.

S-ASUV reference system.

Figure 2.

S-ASUV reference system.

2.2. Kinematic and Dynamic Model

The complete kinematic and dynamic model of the S-ASUV can be seen in section 2 of Ji et al. (2023).

We introduce the subsequent vectors as defined below:

where

η is the vector of position

and pose

, i.e., Euler angle,

V is the velocity vector.

The kinematics equations of the AUV can be expressed as:

in which the conversion equations of the linear velocity and angular velocity are given as follows, where

s = sin,

c = cos, and

t = tan

Table 3.

Main Parameters of S-ASUV.

Table 3.

Main Parameters of S-ASUV.

| Parameters |

Description |

|

m (kg) |

4.99 |

|

G (N) |

48.902 |

|

B (N) |

50.406 |

|

γ (m) |

0.0975 |

|

l (m) |

0.211 |

| (xg, yg, zg) (mm) |

(0, 0, 11.15) |

| (Ix, Iy, Iz) (kg m2) |

[0.01426, 0.01426, 0.01426] |

2.3. Modeling of Dynamic Positioning Problem

The objective of this paper is to develop and implement a robust LBMPC framework for achieving precise DP of the multi-rotor dynamics of S-ASUV in varying environmental conditions. The goal is to design a control system that ensures the S-ASUV maintains its desired position and orientation accurately and efficiently while mitigating disturbances and uncertainties inherent in underwater operations using LMPC techniques.

We consider the motion of the vehicle in the local level plane. Two mild assumptions can be satisfied for the low-speed motion of S-ASUV: (i) The vehicle has three planes of symmetry; and (ii) the mass distribution is homogeneous to simplify the mathematical model, reduce computational complexity, and focus on dominant horizontal motions. As a result, for the motion control in the local level plane, the system matrices presented by Ji et al. (2023) can be simplified. The inertia matrix becomes

where

are the inertia terms including added mass. The restoring force is neglected

, and the damping matrix is

where

are linear drag coefficients and

are the nonlinear drag coefficients. The Coriolis and centripetal matrix become:

In the local level plane, the velocity vector encloses the surge, sway, and yaw velocities, and the position and orientation vector includes the position and heading of the vehicle.

By introducing the disturbances and uncertainties, the dynamic model of S-ASUV can be formulated as:

where

denotes the generalized thrust forces and moments.

denotes the disturbance force/torque of water flow environment and

denotes uncertain hydrodynamic forces/moments. The assumption is that the six propellers, denoted as

within the local horizontal plane, collectively generate the generalized thrust force. It is important to note that these propellers are intentionally designed to remain fixed for simplicity, resulting in the representation of thrust allocation

in which

represents the thrust allocation matrix.

The kinematic equations (3) can also be simplified as follows:

where

Define the system state as

and the generalized control input as

. The generalized control input

is the resulting force of the thrusters. For S-ASUV, the experimental platform, six thrusters are effective in the local level plane. From (3) and (11), the dynamic model for the 3D DP problem with the position and pose control is established as below:

where the state vector

. The DP model in (13) of S-ASUV reveals the dynamics from the thrusters to the position and pose in 3D space, facilitating the 3D DP control using LBMPC. The hydrodynamic coefficients for S-ASUV in (13) are summarized in

Table 4.

For the model (13), the following essential properties can be easily explored and will be exploited in the controller design:

P-1: The inertia matrix is positive definite and upper bounded: 0 < M = MT ≤< ∞.

P-2: The Coriolis and centripetal matrix is skew-symmetric: C(V) = −CT(V).

P-3: The inverse of rotation matrix satisfies:, and it preserves length

.

P-4: The damping matrix is positive definite: D(V) > 0.

P-5: The input matrix satisfies that SST is nonsingular.

P-6: The restoring force g(η) is bounded:

While we initially assumed in section 2.2 for simplicity, we recognize and acknowledge in subsequent sections (P-6 and Assumption 2) that exists within defined bounds. This acknowledgment ensures that our model accounts for the bounded and modest influence of the restoring force, aligning with physical constraints and operational scenarios.

Table 4.

Hydrodynamic coefficient summary.

Table 4.

Hydrodynamic coefficient summary.

| Inertia term |

Linear drag |

Nonlinear drag |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This research focuses on achieving precise three-dimensional dynamic positioning for S-ASUV while maintaining robustness in complex underwater environments. To this end, this work integrates the multivariable PID into the LMPC scheme with Lyapunov stability analysis, enhancing control performance and stability. The study conducts rigorous feasibility and stability analyses, ensuring robustness to external disturbances and model uncertainties.

3. Dynamic Positioning Based on LBMPC

3.1. Formulation of Optimization Problem

DP control refers to the implementation of feedback control techniques in S-ASUV, and the goal is to maintain a desired position and orientation through the adjustment of propeller thrust alone. Numerous existing DP controllers have been devised using the Lyapunov direct method, boosting global stability attributes. Explicitly incorporating these controllers allows us to formulate the LMPC problem for DP control (Shi et al.,2023). Considering the preferred location and orientation indicated by

, the nonlinear optimization problem(

) of DP for S-ASUV can be formulated as :

where

stands for the planned trajectory of the AUV's state, using the system’s model to evolve;

represents the error state where

;

represents a collection of piece-wise constant functions based on the sampling period

.

indicates the forecasting horizon,

X,

Y, and

Z, represent the weighting matrices and are guaranteed to maintain positive definiteness. It is noted that

(·) conventionally denotes the PD controller, while herein, for LBMPC, we propose the PID secondary controller, which is demonstrated in Subsection 3.2. At the same time,

W (·) signifies the corresponding Lyapunov function.

3.2. PID Secondary Control Law

Unlike the modern LMPC techniques (Shen et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2023), which employ a PD secondary control law, the multi-variable PID controller is used as the secondary law, enhancing the rapidity and accuracy of the DP control. For the theoretical explanation, the designed PID secondary law also introduces the disturbance and model uncertainties, playing a role in resisting disturbances and uncertainties. The used multi-variable PID control law is considered as:

where

, then one can easily obtain

. The user defines the control gain matrices

which should be diagonal and positive definite. It is important to note that

were not directly implemented in the control algorithm. Instead, they were adjusted through parameters in the digital experiments to represent real-life disturbances. This unconventional approach was adopted to evaluate the robustness and performance of the PID control law under various disturbance scenarios.

The proposed choice for the Lyapunov function is the following:

When computing the time derivative of W along the trajectory of the closed-loop system, Using the product rule and noting that

are constant matrices, we differentiate each term separately. Combining these results, we obtain:

Substituting (11), (12), (19), and (20) into (22) yields

where

. Considering

for all V, we have

the gain parameter

is positive. Following Khalil (1996), LaSalle’s theorem indicates that the closed-loop system, influenced by the nonlinear PID controller, exhibits global asymptotic stability relative to the equilibrium point

.

The comprehensive description of the contraction constraint (18) associated with the use of nonlinear PID control follows:

To ensure recursive feasibility, it is worth noting that the PID controller, remains viable for the LBMPC (14), (15), (16), (17) ,and (18) as long as we can satisfy the condition .

The following uses several logical and realistic assumptions to simplify calculations.

Assumption 1: The maximum capacity of the propellers is the same, i.e., . Note that Assumption 1 is plausible and frequently accurate in real-world situations.

The proposition that follows is then;

Proposition 1: Consider the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse implementation when allocating thrust, that is,

and signify the highest generalized thrust force possible by

with

. if this relationship holds:

where

, then it is always possible to allocate the thrust., that is,

.

Proof: If we take the infinity norm on either side of (26) we get

In light of (27) and Assumption 1, (28) results in

Assumption 2: The restoring force

is limited in magnitude and relatively modest, such that

where

denotes the input bound.

The second assumption is likewise a valid one. Sine and cosine function combinations are included in the comprehensive definition of . Therefore, we can ensure that the restoring force remains within certain bounds. Moreover, it is worth noting that the upper bound is considerably smaller in magnitude compared to the maximum allowable thrust force . Failing to meet this condition would render the feedback control, which is not considered in this study, infeasible.

3.3. Stability Analysis

In this subsection, the feasibility and stability of the proposed LBMPC are both proved rigorously, guaranteeing the closed-loop stability of the DP control system.

Theorem 1: Assume that the control gains

are each equal to

. Let

,

and

represent the greatest elements in

, respectively, and suppose assumptions one and two can hold and define

. If the relationship shown below can hold:

where

denotes the initial error and

adheres to equation (27), the LBMPC problem (

) recognizes recursive feasibility. In other words,

Proof: By applying the infinity norm to both sides of equation (19), we obtain:

Since

From (12) and (20), we have

As (18) is fulfilled, it allows for

. Consequently, we can conclude that

. Considering

, we arrive at;

Together with (32), we have

If we can meet condition (31), then the subsequent relationship is valid.

With (27), we can guarantee that remains satisfied consistently, thereby concluding the proof.

We observe that it is straightforward to fulfill condition (31) by assigning as arbitrarily small positive values. The size of the region of attraction can be flexible as the assurance of closed-loop stability is provided through recursive feasibility.

Theorem 2: Suppose that both Assumptions 1 and 2 are met. In that case, the LBMPC dynamic positioning control will ensure the continuous stability of the required equilibrium point . Additionally, by employing sufficiently small control gains the region of attraction can be significantly expanded.

Proof: The proof first shows that the equilibrium is asymptotically stable and then demonstrates that you can adjust the size of the region where the system's trajectories will converge to the equilibrium as needed. Applying the reverse Lyapunov theorem (Khalil, 1996), given that we have already identified a continuously differentiable and unbounded Lyapunov function

in (21), continuously differentiable and radically unbounded by converse Lyapunov theorems (31), there exist functions such as

belonging to the class

satisfy the subsequent inequalities:

Considering (18) and the fact that each sampling period will only use the first component of

, we obtain

We affirm that employing common Lyapunov arguments, the closed-loop system under LBMPC

is asymptotically stable and possesses a region of attraction using common Lyapunov arguments (such as Theorem 4.8 in Khalil (1996)).

where

represents the error state.

We choose the control gains

meeting the arbitrary big initial error condition

, therefore satisfying

Therefore, the closed-loop system exhibits stability, affirming the solvability of the LBMPC problem. The extent of the region of attraction can be adjusted as needed as long as there are sufficient small control gains to satisfy (41) because there are no other restrictions on .

Remark 1: The magnitude of the control gains impacts the PID controller's control performance, despite the fact that asymptotic stability relies solely on the control gain matrices being positively definite. A slower rate of convergence will result from smaller control gains. Nevertheless, although significantly small control gains are chosen to attain a broad region of attraction in the proposed LBMPC DP control, the optimization procedure allows the system to effectively leverage its thrust capability to achieve optimal control performance consistent with the objective function (14).

3.4. LBMPC DP Control Algorithm

The LBMPC DP control algorithm can be followed by a list of steps that describe how the algorithm will be executed below:

(i) At the current sampling instant t0, taking into account the system's present state , we address the optimal control problem (P0); let represent the sub-optimal solution;

(ii) the S-ASUV applies for just a single sampling interval: ;

(iii) At the subsequent sampling instant , a fresh measurement of the system's state is incorporated as feedback, then, (P0) is solved once more, starting anew with the fresh initial condition . The process iterates, recommencing from step (i).

4. Experiments and Discussion

In this section, the primary purpose lies in validating and verifying the peformance of the proposed method, ensuring accuracy and effectiveness. The dynamic model of the S-ASUV, established using the data in Ji et al. (2023) is employed in this part. To testify the advantages of the proposed method, the classical PD (Bayusari et al., 2021), modern controllers including MPC (Beklan et al., 2023) and LMPC (Shi et al., 2023) were used in a series of experiments for comprehensive comparison.

4.1. Selection of Parameters

We have set the target position, represented by, , to be situated at the origin of the IRF, and this decision was made to maintain simplicity without compromising generality. According to experimental data in (Ji et al., 2019), the actual maximum force output for each propeller is 8N. In order to tackle the LBMPC problem formulated in equation (14) to (18), we utilize a discretization strategy coupled with Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) to obtain a solution. This can be followed by a list of the variables that were chosen.

Sampling period ,

Prediction horizon ,

Weighting matrices:

,

,

Control gains for nonlinear PID control: ,

Starting state :,

,

The thrust allocation matrix

.

4.2. Performance Comparison and Analysis

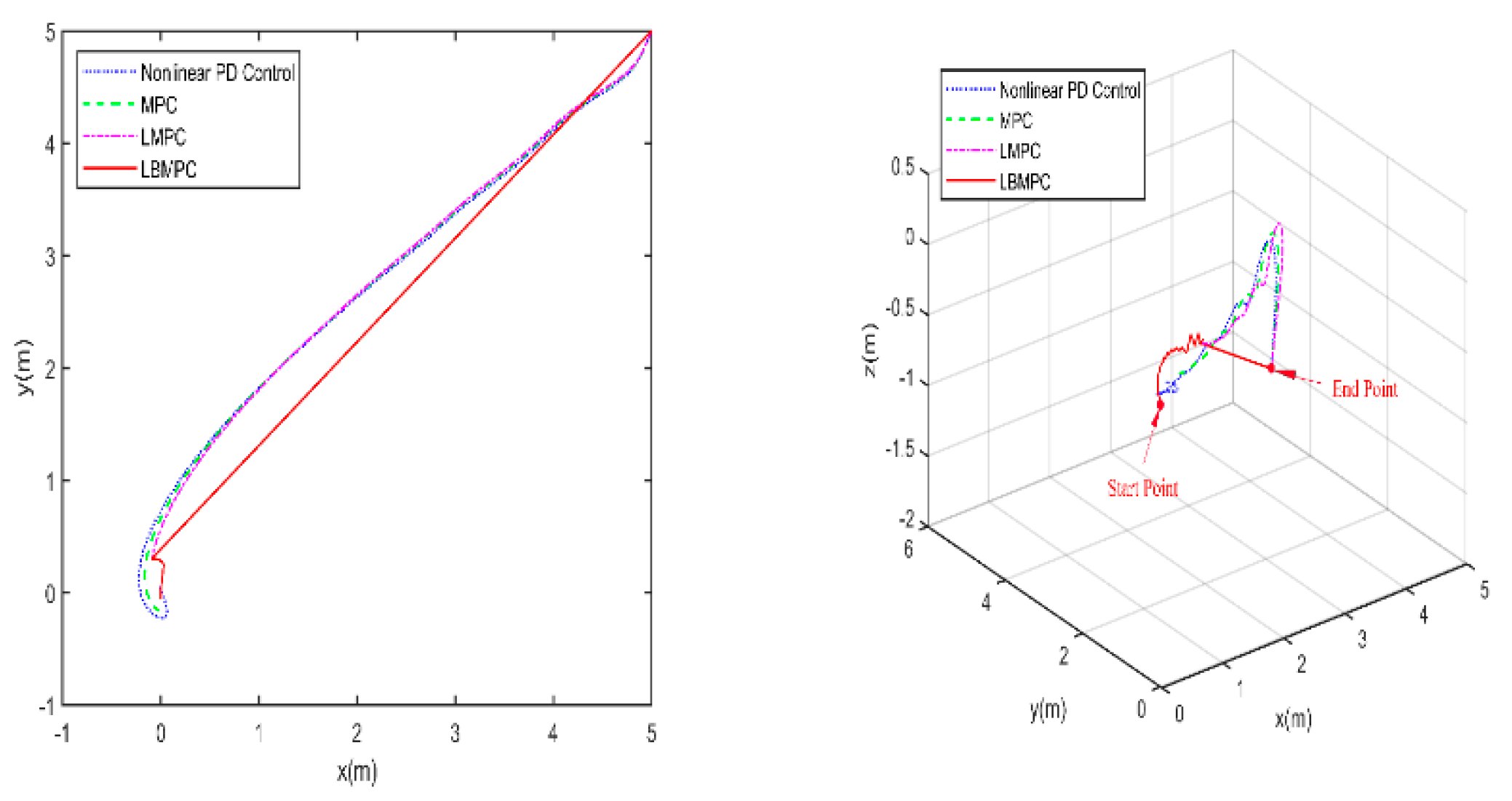

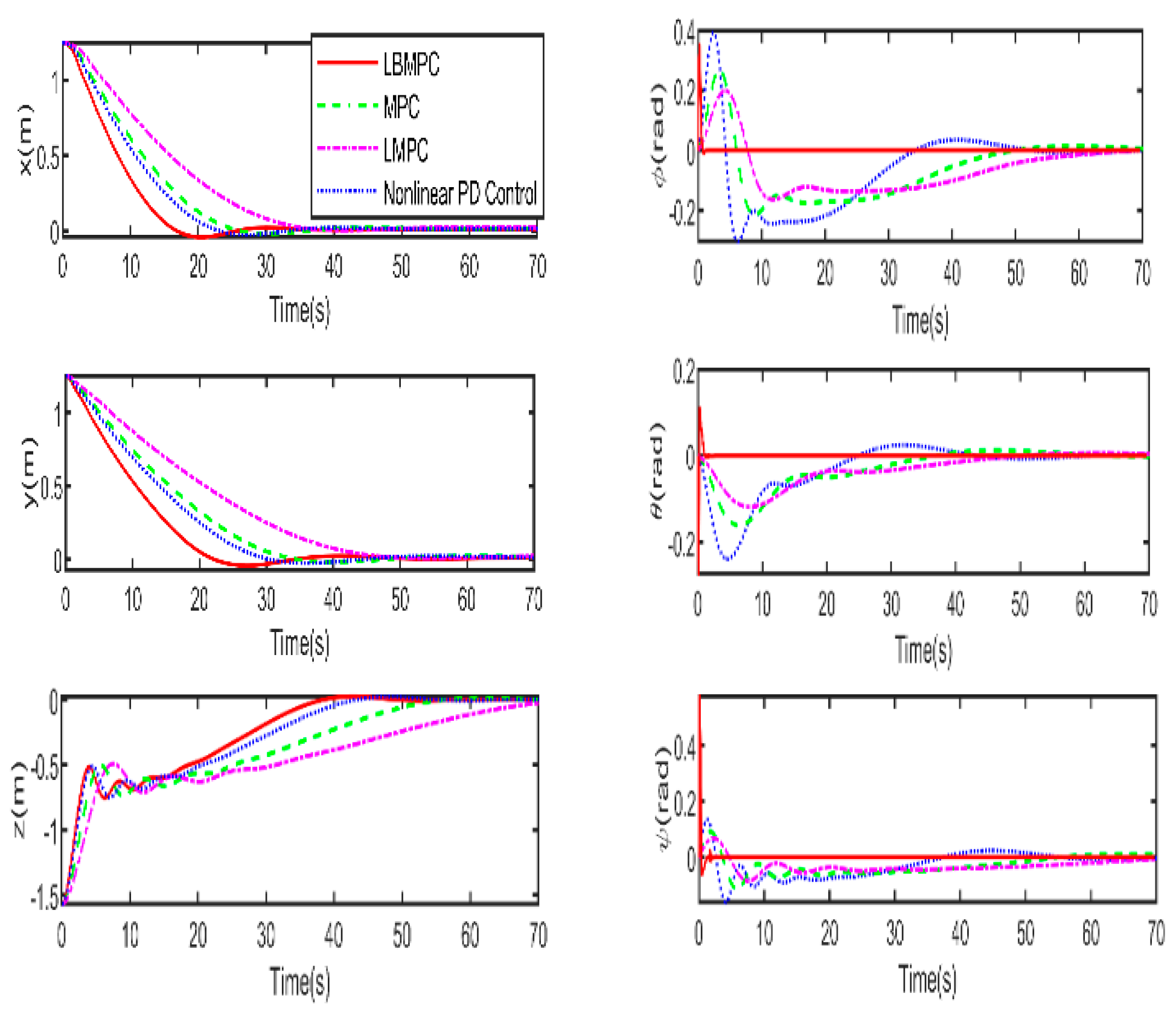

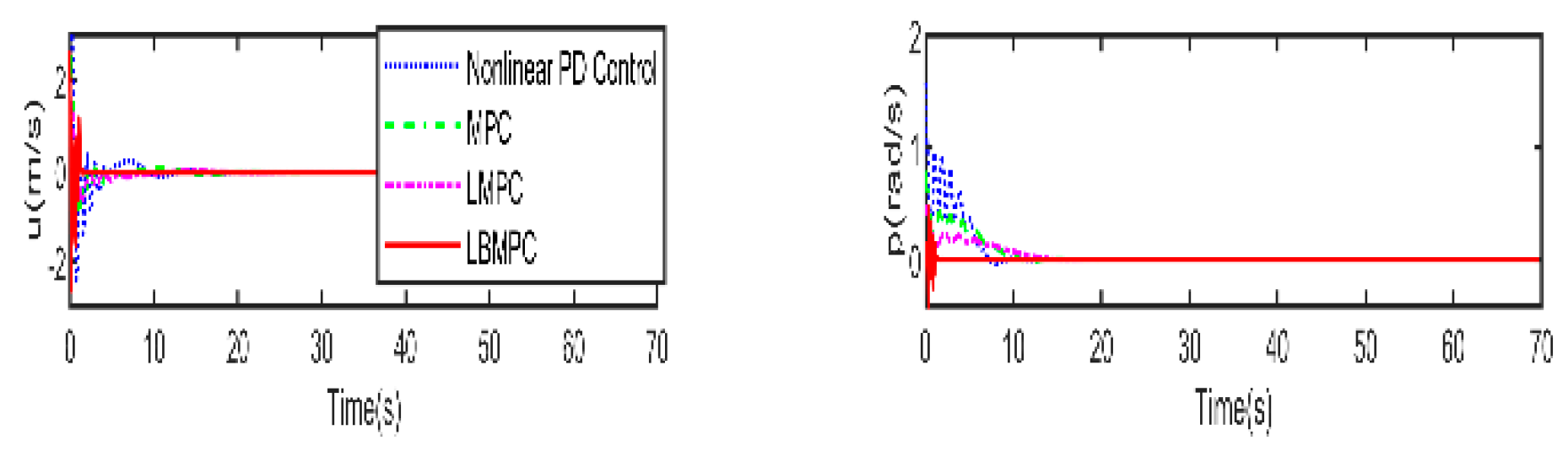

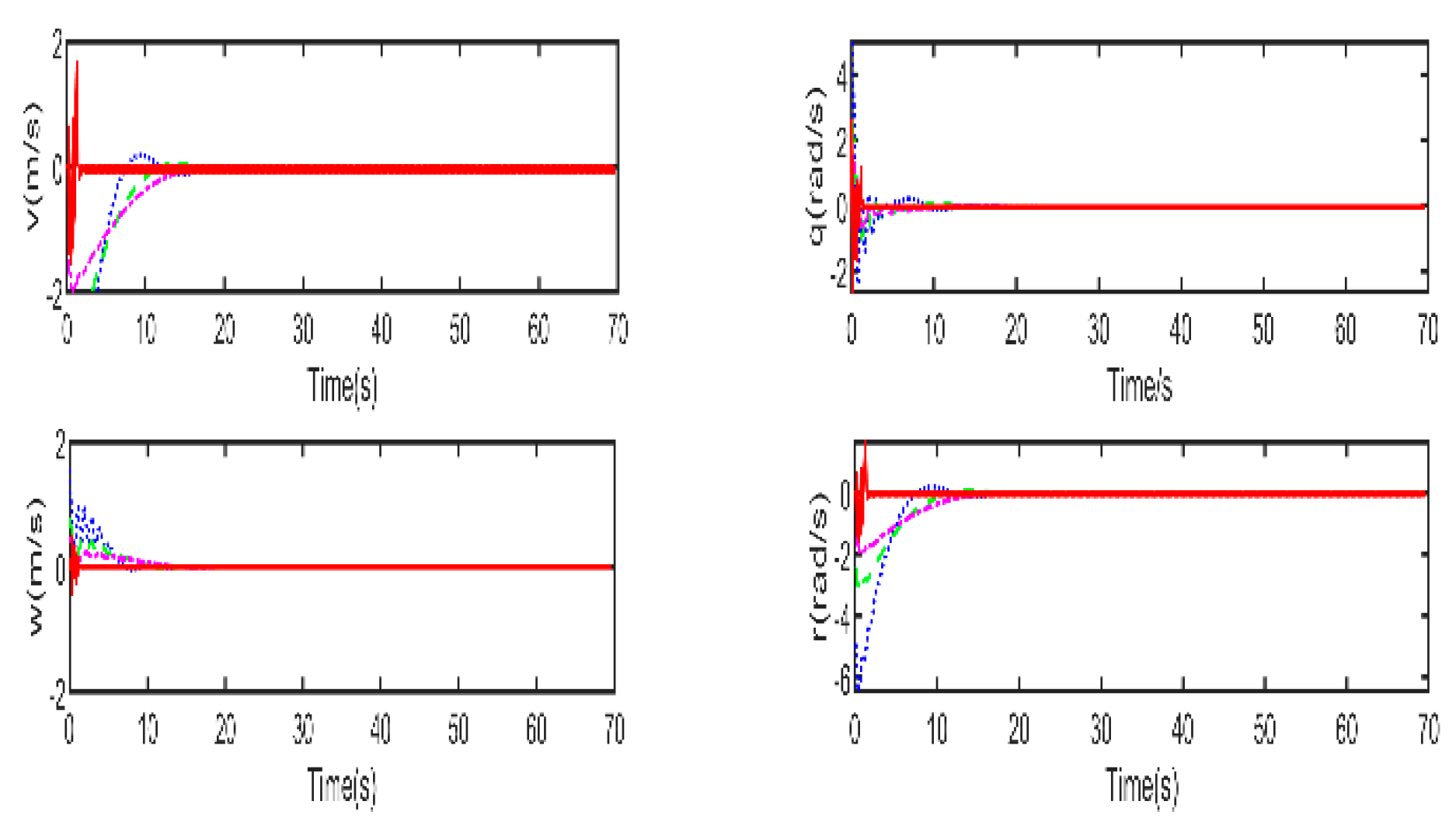

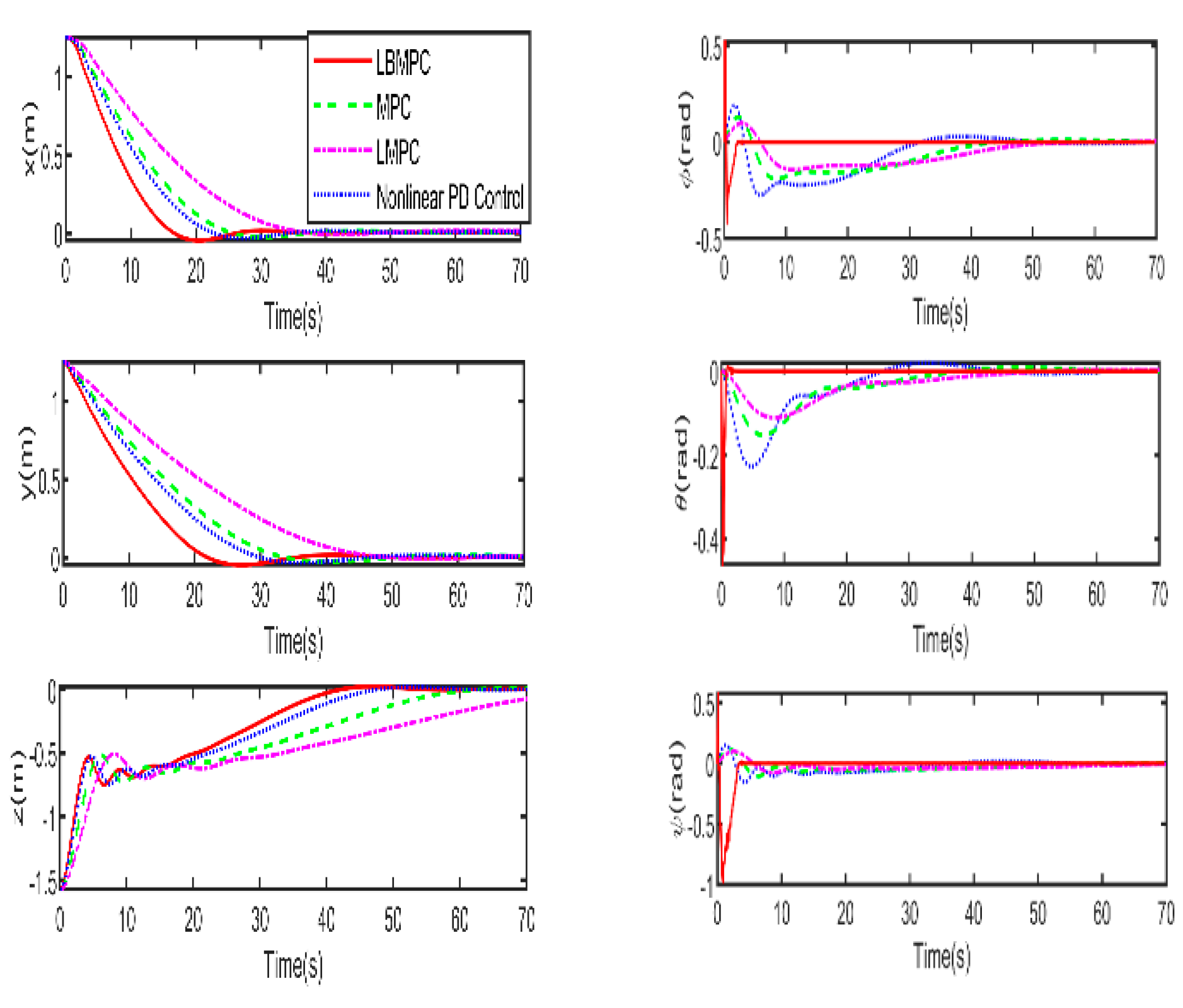

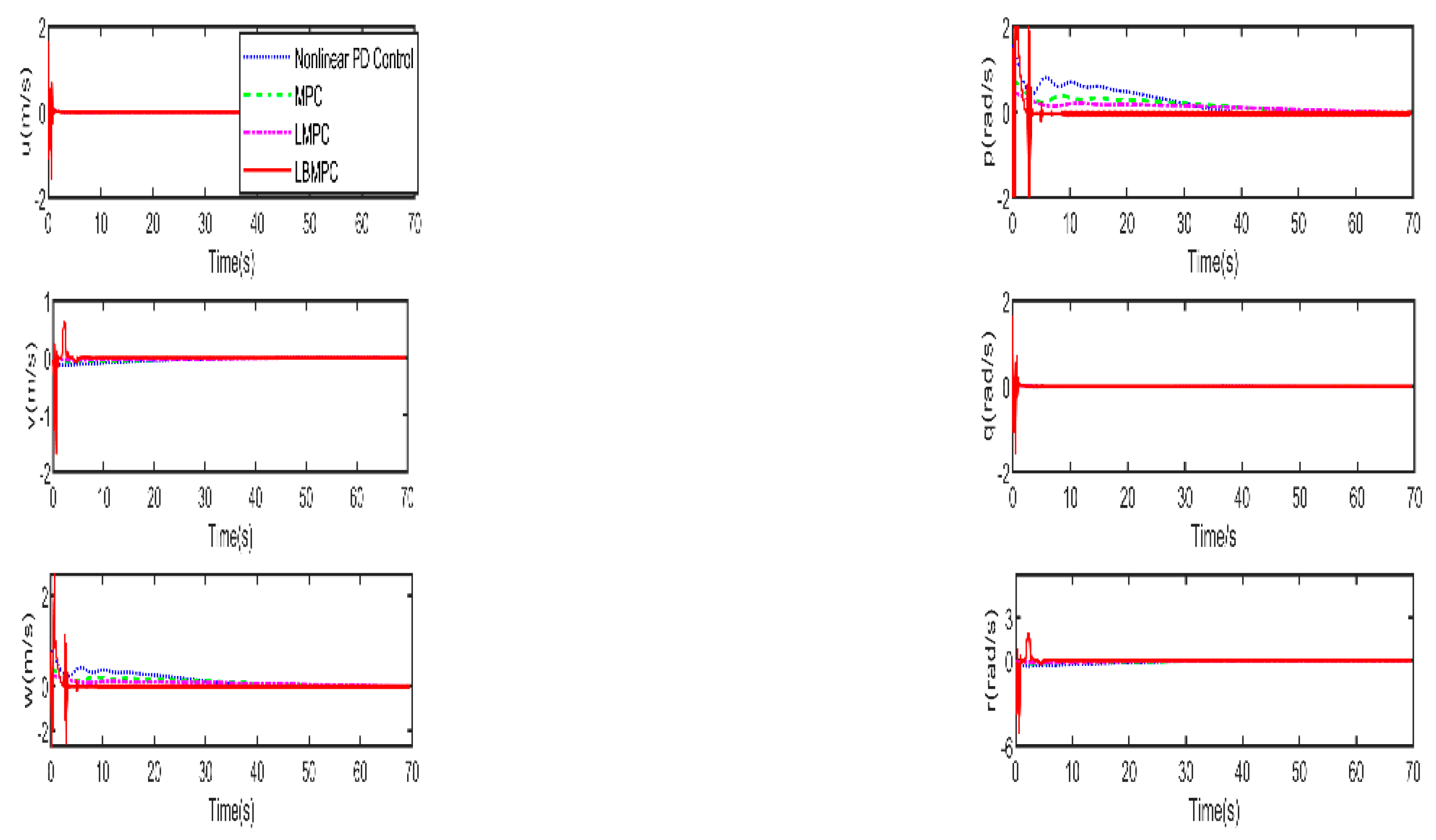

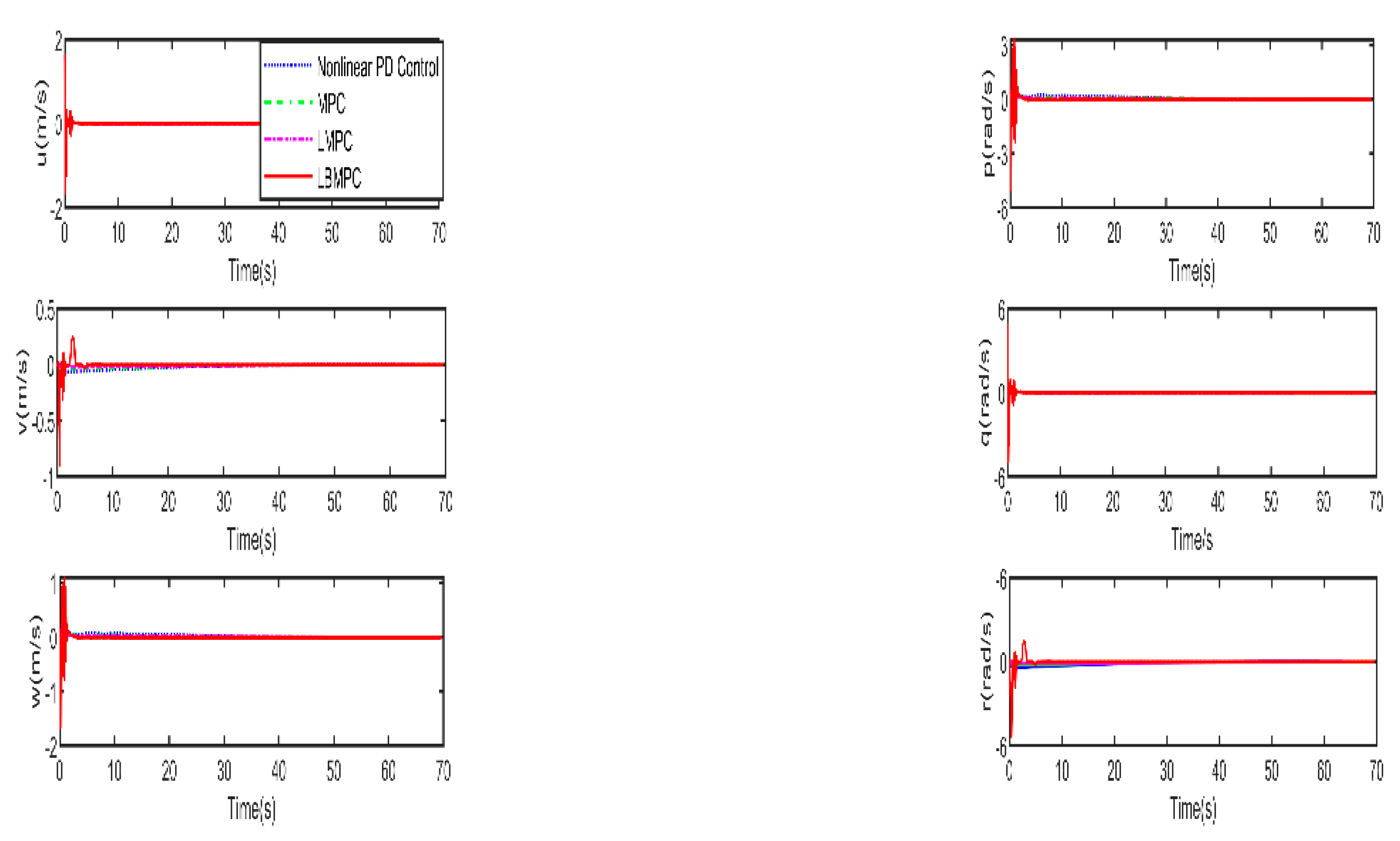

The first experiment is conducted without disturbances and uncertainties to observe the behavior of the proposed controller under ideal conditions. The trajectories towards the origin of the S-ASUV in 2D(left) and 3D(right) are shown in

Figure 3, and

Figure 4 illustrates the responses involving the position x ,y ,z and, pose

of the vehicle. The corresponding linear and angular velocities

are given in

Figure 5. As shown in

Figure 6, which displays the thrust forces generated by individual propellers, it is confirmed that each control input stays within the designated permissible range as intended.

As shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, it is clear that the LBMPC controller achieves a stable DP within the first 30 seconds, significantly quicker than the PD, MPC controller, and LMPC controller, which typically takes around 45 to 55 seconds on average. The experiment results vividly demonstrate how real-time optimization has improved the performance of DP control. The results show that incorporating multi-variable PID secondary law has led to a considerable enhancement in the convergence rate for DP control when utilizing the LBMPC method. This improvement is noticeable throughout a broad range of attractions.

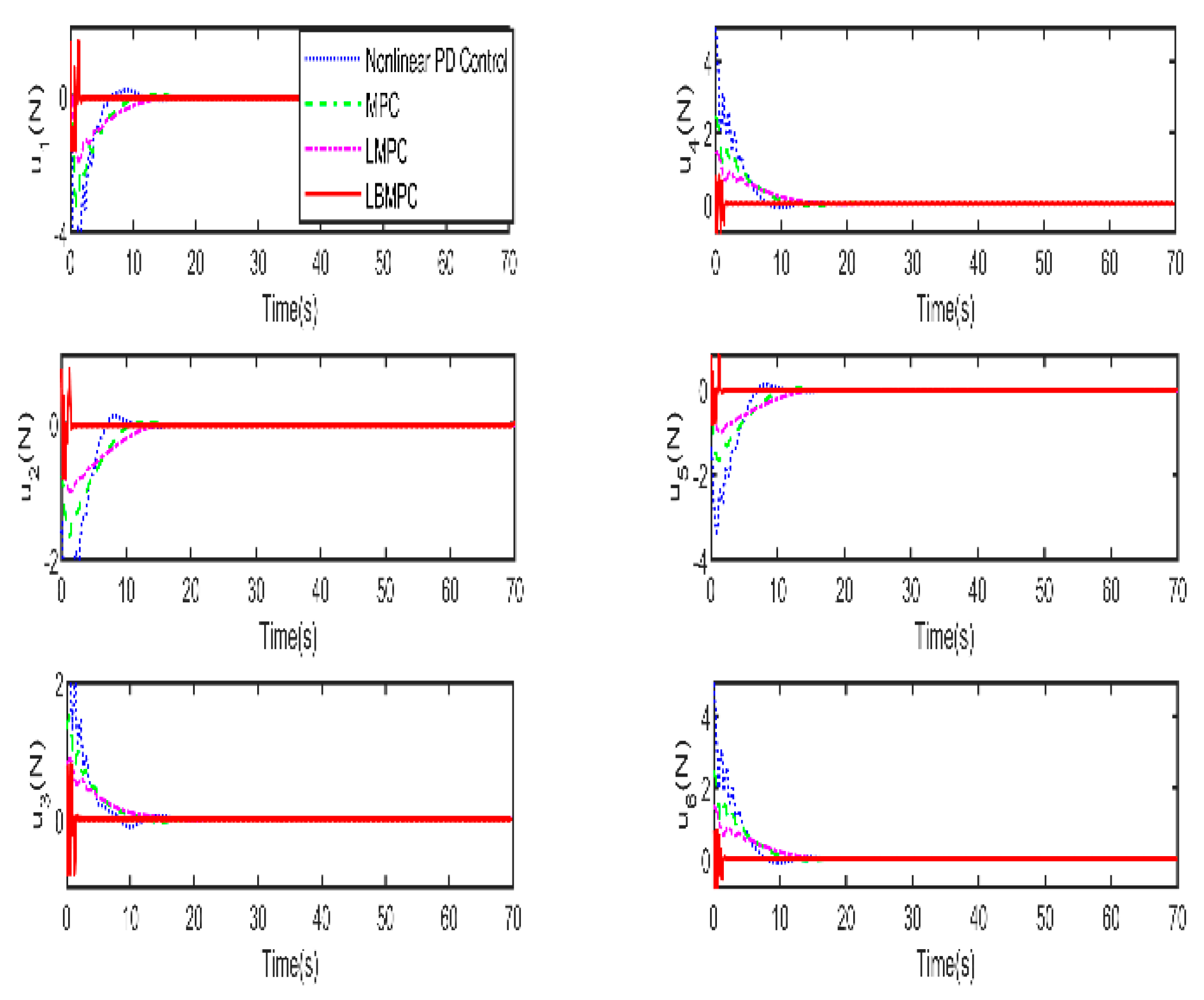

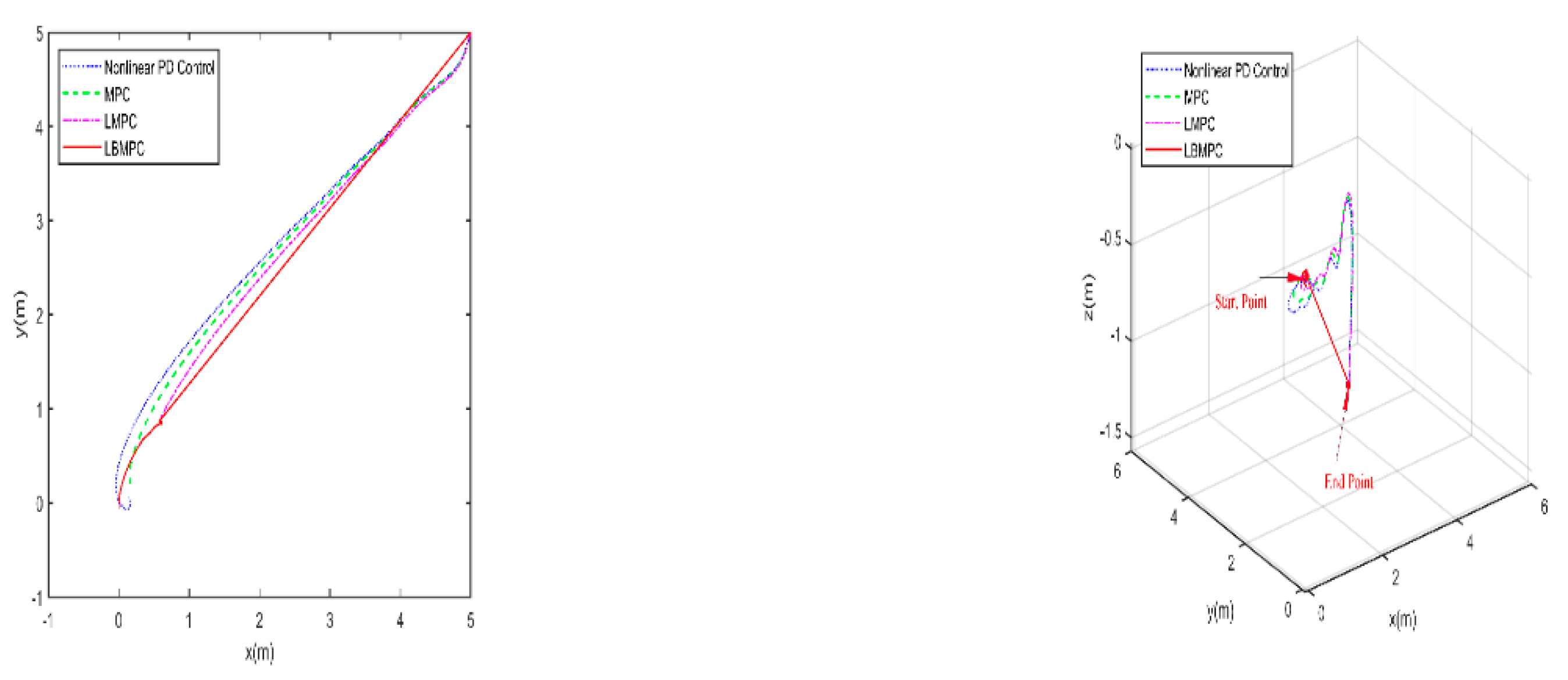

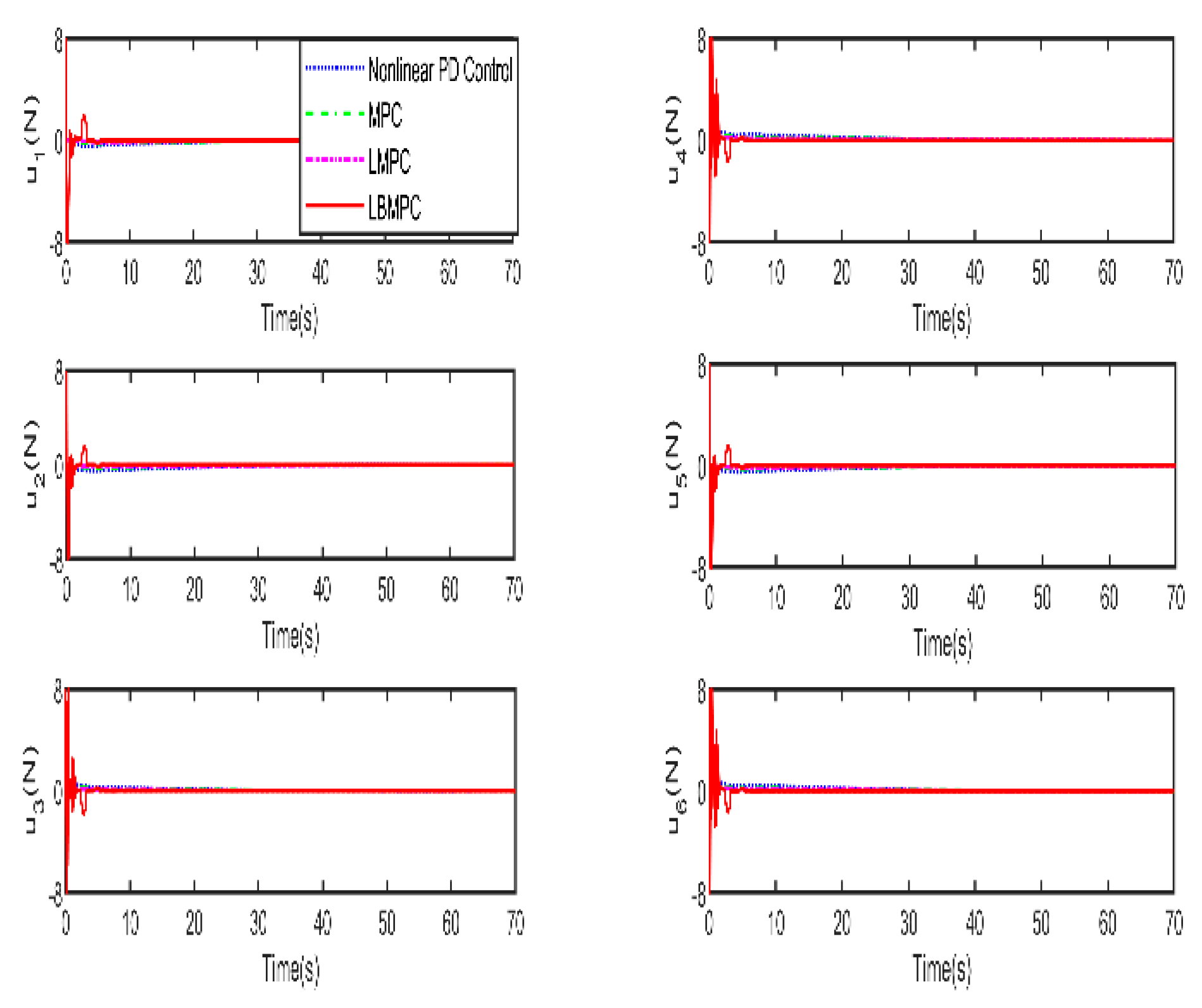

In the second experiment, depicted in

Figure 7 to 10, this study aimed to enhance the robustness of LBMPC. To emulate an irrotational ocean current, which exerts a consistent force on the vehicle, we introduced a disturbance index with a magnitude of

. Moreover, we included a 20% system model error to further assess the controller’s ability to cope with such intricate situations.

As shown in

Figure 7 to 10, which depict the outcomes under moderate disturbances and model uncertainties, the LBMPC controller maintains the robustness. In

Figure 7, using the proposed method reaches the origin in the shortest route, while using the other controllers need longer way. Looking at

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, the proposed method performs even better, achieving DP within 40 seconds, surpassing the PD, MPC and LMPC controllers, which take much more time to accomplish this task. The overall deviation of using LBMPC towards the origin along the time is the smallest among the methods. It becomes clear that the LBMPC DP control not only achieves convergence to the desired target location but also improves the overall perfromances including robustness, accuracy and rapidity of the DP control system.

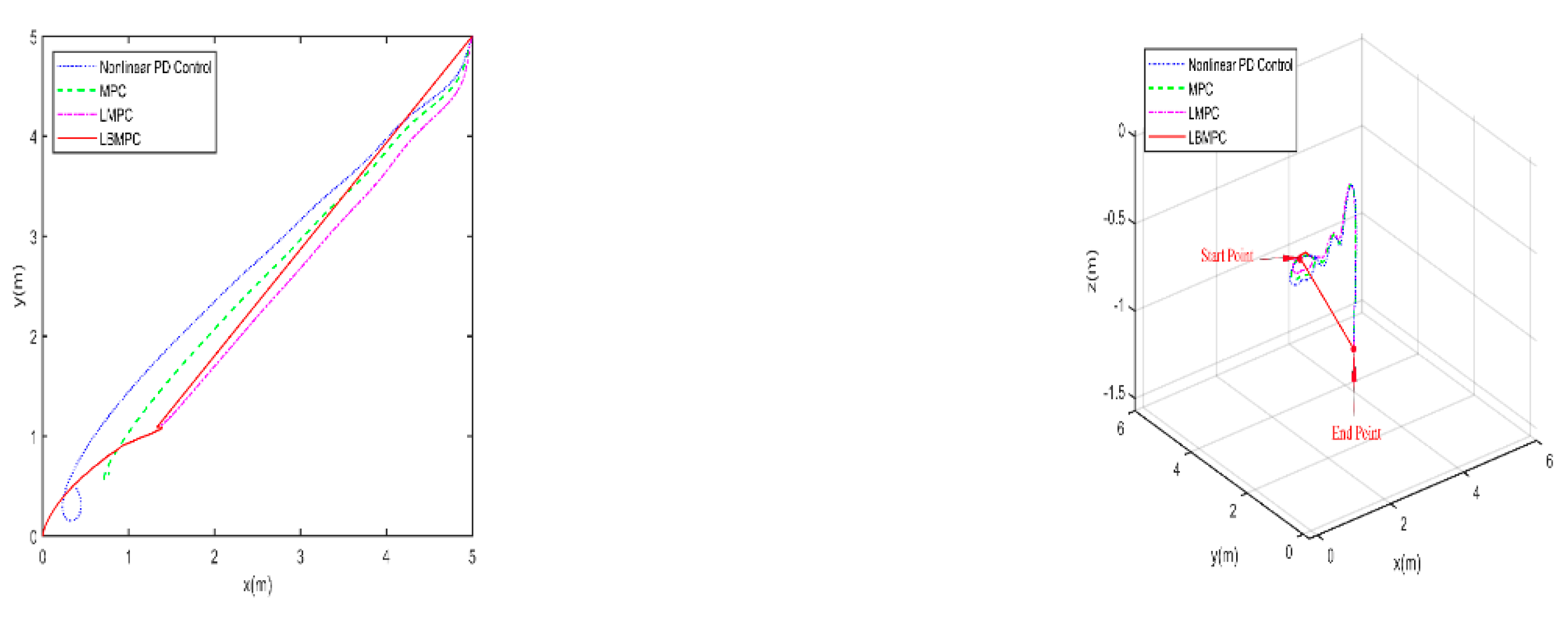

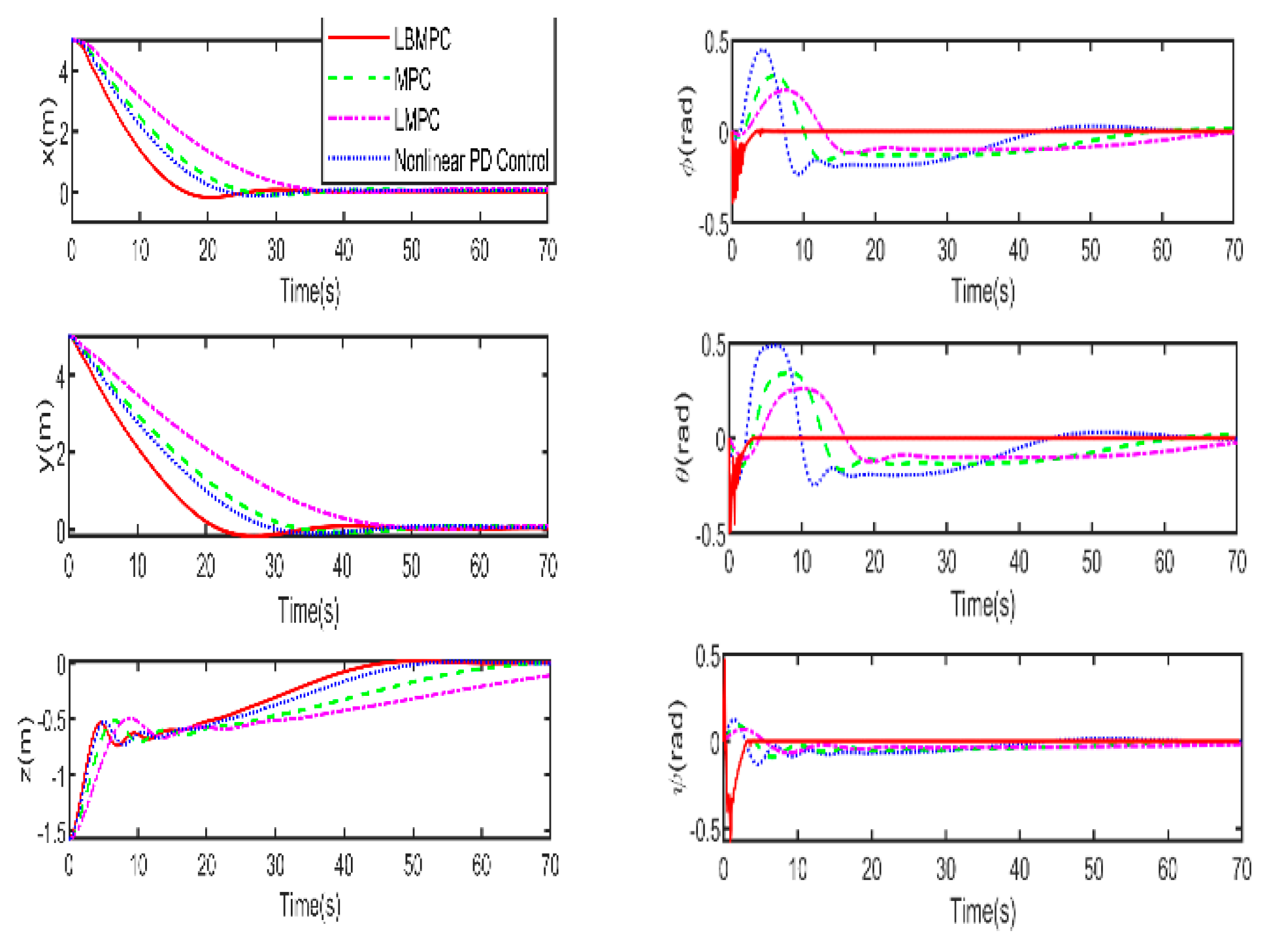

In the last experiment depicted in

Figure 11 to 14, this work sought to reaffirm the robustness of the proposed controller. Introducing a heavy disturbance index of

magnitude, we deliberately incorporated a +20% system model error and a -20% variation in the damping matrix to replicate the most demanding scenario. This was undertaken to assess the controller's effectiveness in managing the heavy scenarios and complex situations.

In the trajectory responses shown in

Figure 11, the proposed controller LBMPC consistently outperforms other controllers by reaching convergence in the shortest route. This trend is further highlighted in

Figure 12, where the proposed controller achieves DP significantly fastest within 30 seconds. Additionally, control inputs depicted in

Figure 14 remain within the designated permissible range. Comparing the first two experiments, it is evident that the proposed control method performs best among the three different conditions.

5. Discussion

This inherent robustness is a notable advantage of LMPC and renders it an attractive option, particularly in marine control systems (Pannocchia et al., 2011). In the experiment results, the LBMPC controller demonstrates sustained robustness. It not only achieves convergence to the desired target location but also enhances the overall robustness of the DP control system, even under the most challenging scenarios. As mentioned earlier, the dynamic response’s rapidity and robustness are significant for the DP problem of marine vehicles. By incorporating the designed PID feedback into the closed-loop system, the proposed LBMPC improves the accuracy and rapidity of the DP control responses significantly compared to both the conventional LMPC and commonly used approaches, improving the DP control performance of marine vehicles, including S-ASUV in complex dynamic environments.

Beyond validation, the experiments using S-ASUV’s model offers cost and time efficiencies, allowing extensive testing and scenario exploration in a virtual environment, thereby mitigating risks associated with actual operations. It enables iterative refinement of the proposed control method, rapidly incorporating improvements to enhance the S-ASUV’s performance while collecting comprehensive data for in-depth analysis of system behavior and informed decision-making. Ultimately, the series of experiments serve as a vital tool, optimizing and validating the proposed LBMPC framework, critical for precise motion control in complex underwater environments.

This study acknowledges several limitations that need to be addressed for a comprehensive understanding and application of the proposed methods. Firstly, the digital experiments were conducted under idealized conditions that may not fully replicate real-world environments, necessitating future testing in more varied and challenging scenarios to validate the robustness of the control strategies. Hydrodynamic modeling relies on specific assumptions about environmental forces and vehicle dynamics, which may not hold true in all operational contexts and potentially affect control system performance. The practicality of the proposed control law is limited by its inclusion of terms for environmental disturbances and uncertain hydrodynamic forces, which are not directly measurable in real-world applications, indicating a need for additional estimation or compensation methods. While the digital experiment results are promising, they do not substitute for field tests; actual deployment on autonomous underwater vehicles in various operational conditions is necessary to evaluate the system's effectiveness and reliability thoroughly. Additionally, the control system's performance may be sensitive to the tuning of specific parameters, requiring a systematic study of parameter sensitivity and the development of robust tuning methods to ensure consistent performance. Lastly, the study does not address the long-term stability and adaptability of the control system in dynamic and unpredictable environments, highlighting the need for future work on adaptive control mechanisms that can adjust to changing conditions over extended periods.

6. Conclusions

In the research, a novel LBMPC method tailored specifically is introduced for the DP challenge faced by the S-ASUV, providing a useful solution to the 3D DP control problem. The three dimensional DP control problem is established with an MPC formulation. To effectively handle the chronic restrictions of the current DP control approaches, this study proposes a novel LBMPC DP method. The multi-variable PID control and the contraction constraint are incorporated into the LBMPC problem. The designed PID secondary law also introduces the disturbance and model uncertainties. The feasibility and stability are both proved rigorously. A series of S-ASUV’s digital experiments under diverse conditions demonstrate the proposed method's superior performances over existing controllers, affirming the position and pose control in the 3D space in complex dynamic environments. The proposed LBMPC helps control performance in terms of accuracy and rapidity, which is suitable for S-ASUVs and other marine vehicles like deep sea autonomous remoted vehicles (ARV), providing a balanced perspective on its contributions and outline directions for future research.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by This work was supported in part by National Key R&D Program Projects under Grant 2023YFC2813000, Grant 2023YFC2813003 and the earmarked fund for the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-45).

References

- Ahmed, F., Xiang, X., Wang, H., Zhang, J., Xiang, G., & Yang, S. (2023). Nonlinear dynamics of novel flight-style autonomous underwater vehicle with bow wings, Part I: ASE and CFD based estimations of hydrodynamic coefficients, Part II: Nonlinear dynamic modeling and experimental validations. Applied Ocean Research, 141:103739.

- Bayusari, I., Alfarino, A. M., Hikmarika, H., Husin, Z., Dwijayanti, S., & Suprapto, B. Y. (2021). Position Control System of Autonomous Underwater Vehicle using PID Controller. International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Informatics (EECSI), 2021-October, 139–143. [CrossRef]

- Beklan, ibrahim, Jimoh, I. A., Yue, H., & Küçükdemiral, I. B. (2023). Autonomous underwater vehicle positioning control-a velocity form LPV-MPC approach Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Positioning Control-a Velocity Form LPV-MPC Approach ⋆. https://edshare.gcu.ac.uk/id/eprint/5179.

- Board, O. S., & Council, N. R. (2003). Exploration of the Seas: Voyage into the Unknown. National Academies Press.

- Cui, R., Yang, C., Li, Y., & Sharma, S. (2017). Adaptive Neural Network Control of AUVs with Control Input Nonlinearities Using Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, 47(6), 1019–1029.

- Cui, R., Zhang, X., & Cui, D. (2016). Adaptive sliding-mode attitude control for autonomous underwater vehicles with input nonlinearities. Ocean Engineering, 123, 45–54.

- Fossen, T. I. (2011). Handbook of marine craft hydrodynamics and motion control. Wiley.

- Fu, M., Zhang, G., Xu, Y., Wang, L., & Dong, L. (2023). Discrete-time adaptive predictive sliding mode trajectory tracking control for dynamic positioning ship with input magnitude and rate saturations. Ocean Engineering, 269: 113528.

- Ji, D., Cheng, H., Zhou, S., & Li, S. (2023). Dynamic model based integrated navigation for a small and low cost autonomous surface/underwater vehicle. Ocean Engineering, 276: 114091.

- Ji, D., Zhou, S., Ren, J., & Sun, M. (2019). A prototype of newly dynamic underwater vehicle using fuzzy PID control. 2019 IEEE 28th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), 1121–1126.

- Khalil, H. K. (1996a). Adaptive output feedback control of nonlinear systems represented by input-output models. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 41(2), 177–188.

- Li, H., & Shi, Y. (2017). Robust receding horizon control for networked and distributed nonlinear systems. Springer.

- Mayne, D. Q., Rawlings, J. B., Rao, C. V, & Scokaert, P. O. M. (2000). Survey constrained model predictive control: Stability and optimality. Automatica (Journal of IFAC), 36(6), 789–814.

- Pannocchia, G., Rawlings, J. B., & Wright, S. J. (2011). Inherently robust suboptimal nonlinear MPC: theory and application. 2011 50th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control and European Control Conference, 3398–3403.

- Perlman, H. (2016). How much water is there on, in, and above the Earth. How Much Water Is There on Earth, from the USGS Water Science School, 2.

- Shen, C., Shi, Y., & Buckham, B. (2017). Lyapunov-based model predictive control for dynamic positioning of autonomous underwater vehicles. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS), 588–593.

- Shen, C., Shi, Y., & Buckham, B. (2018). Trajectory Tracking Control of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Using Lyapunov-Based Model Predictive Control. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 65(7), 5796–5805.

- Veksler, A., Johansen, T. A., Borrelli, F., & Realfsen, B. (2016). Dynamic positioning with model predictive control. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, 24(4), 1340–1353.

- Yang, K., Zhang, Z., Cui, R., & Yan, W. (2024). Acoustic-optic assisted multisensor navigation for autonomous underwater vehicles. Ocean Engineering, 297:117139.

- Y. Shi, C. Shen, H. Wei, and K. Zhang(2023). Advanced Model Predictive Control for Autonomous Marine Vehicles. in Advances in Industrial Control. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Zarkasi, A., Darmawan Yudi, E., Ravi, M. Al, & Angkotasan, J. (2019). Design Depth and Balanced Control System of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle with Fuzzy logic. Sriwijaya International Conference on Information Technology and Its Applications (SICONIAN 2019).

- Zheng, H., Wu, J., Wu, W., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Robust dynamic positioning of autonomous surface vessels with tube-based model predictive control. Ocean Engineering, 199: 106820.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).