1. Introduction

A form of computer science, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is computational intelligence that can see and process information in a way that solves problems and makes decisions, and often beyond the capabilities of human and non-human minds [

1]. AI has transformed the life sciences industry and created new possibilities and continued improvement. AI is a system that includes two main parts, software and hardware. It has algorithms like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) or Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) in the software and hardware is responsible for executing the algorithms. For example, neural network (NN) algorithms let machines such as smartphones engage with the world [

2].

In healthcare, deep-learning algorithms improved diagnosis and procedures by a wide margin. Pathology and medical imaging are just two applications of AI to better analyse, process and reconstruct images, thereby achieving better disease detection [

3]. The other notable use of AI is in imaging genome information that can be vital for healthcare professionals studying genetic disorders and drug resistance [

3]. Also, ML and CNNs have been used in Protein Structure Prediction which is a key task in modelling protein folding and structure in drug design [

4].

In epidemiology and public health, AI assists with disease transmission predictions and implements favourable control measures [

5]. Geospatial AI improves data resolution and processing to better understand environmental drivers of disease propagation and surveillance [

6]. The administration of the hospital also benefits from AI, with pharmaceutical logistics, staff scheduling, and space allocation being simplified [

7]. Companies such as IBM Watson Health offer doctors AI-enabled instruments, so that they can give the individual the medical attention he needs based on his history and genes. These are solutions that save diagnostic costs and unneeded tests [

8].

Secondly, AI-enabled household and wearable devices (known as “Telehealth”) have widened access to care for the elderly and the differently-abled. They facilitate remote monitoring of health metrics, from dietary consumption to mental health [

9]. The same technologies are present in the area of fitness and sports, “Smart Fitness,” where watches track bodily activity and health metrics [

10].

Figure 1, The multiple uses of biomedical engineering in healthcare.

AI is now part of Biomedical Engineering – an interdisciplinary discipline that integrates engineering with biology to solve problems in medicine. Such as in the design of prostheses, biosensors and medical imaging [

11].

Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Healthcare Still, the research on Artificial Intelligence (AI) in healthcare is very much underway. There are examples such as the use of AI to discover three-dimensional biomolecules like proteins in the biotechnology industry. The production of drugs and chemicals can also be optimised with AI’s drug and chemical manufacturing. AI can help in drug search detection and targeting of target structures in microbiota engineering for exciting new era of immunology and pharmacology [

12]. Ai is also useful in pathogen detection and cluster detection of antimicrobial resistant pathogens, which is a key domain for the world’s health [

13]. Artificial Intelligence, fundamentally, involves the replication of human intelligence within machines, enabling them to perform tasks that traditionally require human cognition and decision-making capabilities.

2. Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a multidisciplinary field encompassing computer and data science, aimed at developing synthetic intelligence in machines that mimics human capabilities such as sensory perception, recognition, reasoning, communication, and learning [

14]. Early milestones in AI include programs like the Logical Theory Machine, created by Newell and Simon [

15], and the logic programming system developed by Christopher Strachey in the 1950s. These pioneering efforts inspired generations of researchers to explore the vast potential AI holds for various domains.

The study of AI is broadly categorized into six core areas: Machine Learning, Deep Learning, Neural Networks, Cognitive Computing, Natural Language Processing, and Computer Vision.

3. Machine Learning

Machine Learning is the field which tries to make the machine efficient and can work with any amount of data. It allows computers to work independently of explicit code to read and process information [

16]. Because of this flexibility, Machine Learning is today a common tool in applications that have large-scale complex data. Machine programming techniques that scientists use are Supervised Learning (SL), Unsupervised Learning (UL) and Semi-Supervised Learning (SSL).

Machines are programmed in Supervised Learning to make predictions from given input data but need prior instructions from the programmers. The popular use of Linear Support Vector Machines (SVMs) in biology [

17] is a case in point. Unsupervised Learning, on the other hand, is without any previous programming to guide the machine. Rather, the machine is autonomous, and it chooses to maximise good outcomes as it sees fit. These are algorithm like K-means Clustering, Principal Component Analysis, etc. [

18].

Semi-Supervised Learning is both Supervised and Unsupervised Learning. It relies on self-training and Transductive Support Vector Machines (TSVMs) to reach a middle ground between guided and autonomous learning.

4. Natural Language Processing

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is a mix of technology and language to comprehend speech and non-speech. Through statistical and probabilistic techniques, NLP guesses the words or speech and pinpoints context [

19]. Developments in this area has resulted in the AI powered chatbots such as “Siri” and “Alexa”.

NLP is also being applied to the accessibility and functionality of Electronic Health Record (EHR) platforms in healthcare [

20]. They use patient information, like symptoms from across clinical areas, to mine, categorise, analyze and deliver data appropriately [

21]. In the biomedical space, NLP is used in computational life sciences and medical science research as a tool of bioinformatics [

22].

5. Neural Networks

Neural networks structure computational systems to mimic the processing patterns observed in biological organisms, including humans. Among the many types of neural networks, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are the most notable. CNNs are primarily employed to solve problems by identifying patterns within input data, while ANNs are designed to tackle more complex challenges that require approximation and adaptive learning capabilities. Neural networks form the foundation of both machine learning and deep learning. Most machine learning methodologies utilize neural networks, whereas deep learning networks represent an advanced form, consisting of multiple interconnected neural network layers (three or more) working in tandem [

23]. In healthcare, neural networks power a range of smart applications, including wireless body sensors [

22], mobile health applications, accelerator chips [

24], as well as tools for decision-making and disease prediction [

25].

6. Deep Learning

Deep learning enables machines to comprehend abstract and complex concepts, such as social cues, traffic regulations, and human conversations. Notable deep learning frameworks include Deep Belief Networks and Deep Boltzmann Machines, both of which are built upon Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM) neural networks.

This field has played a critical role in advancing other domains. For instance, its integration with Computer Vision Technology has significantly enhanced capabilities such as facial and object recognition, position estimation, and imaging precision [

26].

7. Cognitive Computing

Cognitive computing, a subset of artificial intelligence, empowers computing systems to emulate human intelligence for problem-solving [

27]. Unlike autonomous problem-solving, cognitive machines, primarily driven by AI, are designed to assist humans in performing tasks.

Advancements in this field have enabled devices to interpret and respond to human emotions [

28], opening up commercial opportunities for AI applications in sectors like healthcare and hospitality. In healthcare, cognitive computing has facilitated the development of AI-based Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSSs), which play a crucial role in aiding diagnosis, treatment [

29], and surgical procedures [

30].

8. Computer Vision

Computer vision focuses on improving a computer’s ability to identify and recognize visual images. By incorporating techniques from fields like deep learning and machine learning, it analyzes image data to achieve highly accurate results in detection and interpretation.

In biology, computer vision holds significant potential for advancing medical diagnostics. Its applications are particularly promising in microscopy, where it can be used to study cell morphology [

31], detect pathogens such as malaria [

32], and even identify microscopic cancers [

33].

9. Advances in Artificial Intelligence in the Medical Sciences

The adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) in medicine has brought about astronomical improvements to patient care, diagnostic and therapeutic tools and personalised medicine. It’s the kind of use of AI that continues to drive innovations in medical sciences as research scales to realise its potential in these areas.

Deep learning has also made diagnostic devices like Computer Tomography and Ultrasonography accurate, make it easier to understand the results and allows less invasive testing [

34,

35]. These innovations make patients easier to diagnose. Machine learning algorithms, for example, have identified biomarkers for disorders such as Acute Renal Failure (ARF), which allows early diagnosis and earlier treatment [

36]. Further innovations come from the use of nanotechnology and AI with deep-learning powered biosensors for disease biomarkers. It allows for early, even at-home diagnosis, the “Hospital-on-a-Chip” model [

37].

In pharmacology, machine learning optimizes Computer-AI Synthesis Planning (CASP) to develop new medical formulations [

38]. Additionally, these algorithms predict Drug-Drug Interactions (DDIs), and combining multiple such algorithms has demonstrated superior accuracy compared to individual systems. This is particularly beneficial for managing complex disorders like osteoporosis and Paget’s disease [

39].

AI also shows promise in augmenting patient care by assisting nursing professionals. Although current studies have not conclusively affirmed the integration of AI into nursing workflows [

40], AI nurse assistants could help mitigate the effects of understaffing, a persistent challenge in recent years [

41]. By sharing the workload, AI systems could potentially improve patient survival rates [

42]. Moreover, efforts are underway to merge robotics with AI to create surgical assistants. While these systems are primarily limited to non-invasive procedures like laparoscopies [

43,

44,

45], they raise ethical concerns regarding patient data privacy and the possibility of robots replacing surgeons, leading to hesitation among physicians about using AI in operating rooms [

46]. Nonetheless, AI could alleviate the workload of surgeons, particularly in the post-COVID healthcare environment.

Despite challenges in fully integrating AI into the responsibilities of doctors and nurses, its effectiveness in streamlining healthcare processes is evident. For example, a Natural Language Processing-enhanced conversational agent was successfully employed for post-operative follow-ups with orthopedic surgery patients, demonstrating performance comparable to that of human staff [

47]. While such solutions may not be necessary for smaller clinics, they can be invaluable for large hospitals with heavy patient loads. AI has also shown promise in identifying Surgical Site Infections (SSIs), which, although rare in sterile environments, can lead to severe complications like sepsis. Immediate detection of SSIs can facilitate timely follow-up care and minimize surgery risks [

48].

Furthermore, AI contributes to post-operative care beyond physical health by addressing psychological well-being. For instance, a study utilizing social media data, including user photos and metadata from Instagram, demonstrated that AI could identify depression with higher accuracy than unassisted practitioners [

49]. This innovative application of Computer Vision and Machine Learning holds immense potential for improving mental health screening processes. Beyond depression, these tools could be applied to conditions such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, postpartum depression, and psychosis.

In conclusion, artificial intelligence (AI) exhibits remarkable functionality, enabling its application across virtually all healthcare sectors. However, its integration with medicine remains at an intermediate stage and has yet to fully align with the immense potential AI offers. Advancing this integration requires further research, informed collaboration with medical professionals, and careful consideration of ethical implications. These steps are essential for unlocking the transformative capabilities of AI in healthcare. The advantages of integrating AI into medical practice are summarized in

Figure 3.

10. Reasons for Using Artificial Intelligence in Biomedical Sciences

Late disease detection and the absence of early treatment and adequate healthcare facilities contribute significantly to complications and mortality. Accurate disease diagnosis often requires substantial time and testing, which can be prohibitively expensive, placing a financial strain on patients and their families [

50]. Additionally, prescribed medications may not always be tailored to the patient’s specific needs or conditions. To address these challenges, Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) tools have been leveraged to develop cost-effective and efficient disease diagnosis models. For instance, Machine Learning-Based Disease Diagnosis (MLBDD) systems are designed to streamline diagnostics. In the case of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), MLBDD systems analyze heart echocardiogram datasets to detect abnormal heart conditions. In biomedical sciences, AI significantly reduces diagnostic errors, thereby minimizing risks during treatment [

51,

52].

In omics research, the vast and complex datasets generated can be effectively analyzed using AI and Machine Learning-based tools. These tools are instrumental in interpreting and identifying genomic data, with the goal of improving prognosis, diagnosis, and treatment methods for various disorders. By training ML models to identify promoter sequences, enhancer sequences, splice sites within transcribed RNAs, mutation sites, and genetic variants, researchers can detect patterns of gene expression, particularly in cancer cells [

53].

Drug discovery, traditionally a time-intensive and laborious process, involves identifying therapeutic compounds through clinical trials—a process fraught with challenges in predicting drug activity. AI and ML tools have revolutionized this field by expediting the prediction of bioactive compounds’ behavior and properties with high accuracy. By training algorithms on extensive datasets covering toxicity, drug-drug interactions, drug-target interactions, and potential adverse reactions, AI enables the development of personalized medicine tailored to individual patients [

54,

55,

56].

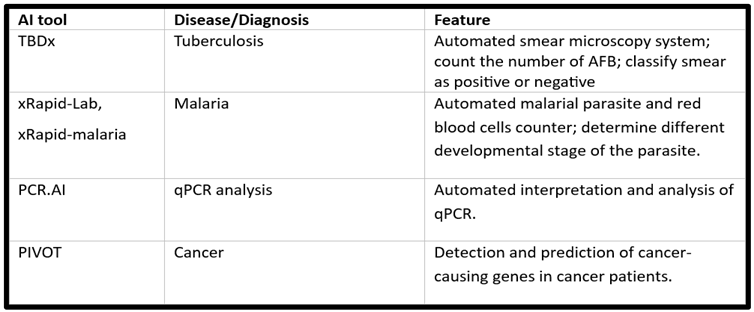

11. Diagnostic Artificial Intelligence Tools

Traditional pathological tests for disease diagnosis are often time-consuming, labor-intensive, and require specialized expertise to interpret results. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI)-based tools has transformed disease detection, making the process more efficient and accessible. Below are examples of automated platforms and tools enhancing diagnostics:

TBDx: This automated smear microscopy system facilitates tuberculosis diagnosis by automating slide preparation and analysis. Prepared slides are placed on the fluorescence microscope stage, magnified at 40X, and digitally imaged. AI algorithms then classify sputum smears as positive or negative by counting acid-fast bacilli (AFB) [

57,

58]. Applications of AI and computer vision in biomedicine, as shown in Figure 6, highlight their impact on such tools.

xRapid-Lab and xRapid-Malaria: These iOS-based mobile applications detect malaria using computer vision algorithms to analyze blood smear images obtained through a digital microscope. These tools provide real-time data on parasite counts and red blood cell (RBC) levels, achieving over 98% accuracy [

58,

59].

Mobile Apps for Disease Diagnosis: Recent developments include mobile applications for diagnosing and predicting diseases such as COVID-19, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes. These apps employ Machine Learning models pre-trained on disease-specific datasets. User inputs are analyzed in real-time, with diagnostic results displayed directly on the app [

60].

PCR.AI: This automated tool interprets and analyzes qPCR amplification curves for detecting diseases and pathogens. It offers improved accuracy at reduced costs compared to manual qPCR analysis [

61].

PIVOT: This AI and Machine Learning-based platform predicts cancer-related genes, such as oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes (e.g., TP53, PIK3CA, SOX9). Trained on multi-omics datasets—including mutation, gene expression, and variation data—PIVOT identifies genetic abnormalities and provides personalized treatment recommendations for cancer patients [

62].

For further details on diagnostic AI tools, see

Table 1.

12. Active Surveillance and Disease Detection

The accuracy and reliability of traditional diagnostic methods have been significantly enhanced through artificial intelligence (AI) analysis, leveraging extensive genomic, radiomic, phenomic, and pathogenic databases [

63]. AI also offers the potential to reduce dependency on biopsy-based diagnostics, paving the way for non-invasive techniques. By facilitating the development of advanced tools that detect diseases through chemical, vocal, and visual indicators—such as biosensors—AI enhances diagnostic capabilities and supports long-term disease surveillance. These tools help determine prognoses and inform treatment options.

Modern biosensors are highly compact and capable of detecting biomarkers from various body fluids, including blood [

64], sweat [

65], saliva [

66], tears [

67], and other in vivo sources [

68]. Ingestible biosensors integrated into pills can wirelessly collect and transmit patient data to physicians [

69,

70]. Enhancing these biosensors with Machine Learning (ML) capabilities would not only improve their sensitivity but also enable the identification of novel biomarkers. AI-driven biosensors provide opportunities for monitoring internal organs, particularly in patients with critical illnesses. This surveillance can track disease progression, such as tumor formation and metastasis, at a chemical level.

Figure 5.

Simplified model of artificial intelligence-based disease control.

Figure 5.

Simplified model of artificial intelligence-based disease control.

Recent innovations in diagnostic techniques for COVID-19 have accelerated the development of AI-based tools that use vocal biomarkers for diagnosis. These algorithms, in conjunction with behavioral indicators, can also detect neurodegenerative and psychological disorders. However, vocal biomarkers are not limited to these applications. Researchers have identified their presence in various diseases affecting other systems, such as Rheumatoid Arthritis [

71]. For example, a Convolutional Neural Network-based sound classifier demonstrated 90% accuracy in diagnosing COVID-19 through vocal biomarkers [

72]. Rapid identification of abnormalities in voice patterns by AI algorithms provides an efficient method for analyzing diseases’ social, epidemiological, and psychological dimensions in a digitalized context.

Genetic Disorders

The use of AI in Bioinformatics can help detect and determine the risk of rare genetic disorders in patients. A study testing a ML-based algorithm’s ability to diagnose Disorders of Sexual Development (DSD), a group of genetic congenital disorders, found that the algorithms was able to diagnose cases with an accuracy of 94.1% [

73]. Supervised Learning models have shown promising results in diagnosing β-thalassemia in antenatal women in studies held in Vietnam [

74], Turkey [

75] and India [

76].

13. Discussion

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a rapidly advancing field that has revolutionized biomedical engineering and healthcare in recent years, leading to significant improvements in patient outcomes and the efficiency of healthcare systems. This article reviews studies on AI and its role across various scientific disciplines, including medicine, bioengineering, and healthcare.

Our findings highlight that AI is now applied in numerous subfields of health, such as imaging, diagnosis, segmentation, and even robotic surgery. These advancements are achieved through tools like machine learning, computer vision, and neural networks. Additionally, emerging applications of AI are being developed in areas like gastroenterology, pulmonary diseases, and immunology.

In biomedical engineering, AI addresses complex challenges and enhances patient care. AI algorithms analyze medical images to detect disease patterns, such as early signs of cancer. They also contribute to developing innovative medical devices and technologies, including surgical robots, and facilitate personalized medicine by tailoring treatments to individual genetic profiles.

AI’s impact on healthcare is multifaceted. It improves medical devices and technologies, enhances patient outcomes, and reduces healthcare costs. One crucial application is the identification and prediction of disease development, enabling early intervention and prevention. For instance, AI automates tasks like maintaining medical records, scheduling appointments, and analyzing health data, streamlining healthcare system operations.

The other real-world application of AI would be in predicting emerging and chronic diseases based on past, biomarkers, imaging, etc. This ability is especially needed in countries where so much of healthcare funding is spent on chronic diseases that can be prevented, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. These diseases can be predicted and shortened through AI, both for patients and healthcare systems.

That is why medicine and engineering need to work in interdisciplinary teams. These partnerships allow for easy to use tools that enhance patient care and help healthcare become more efficient. Adding advanced technology into healthcare infrastructure has immediate implications in terms of time and money savings, but also more reach for everyone.

14. Conclusions

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) has proven to be highly promising in many aspects of healthcare. It also helps clinicians and patients, making the diagnosis, decision-making, treatment and surgery of disease simpler. In addition, AI reduces hospital bills – an ease that’s not always accessible to patients.

But access to care is still skewed, especially in poorer neighborhoods far from cities, where hospitals and medical personnel tend to be stacked together. Such a difference could be overcome through the development of AI-based health systems that are simple, affordable and readily available. This kind of systems would help the world in fulfilling the Sustainable Development Goal of promoting healthy living for all.

The prevention of disease potential of AI is especially exciting. Through early detection and forecasting, AI can prolong lives, decrease the rate of illness and avoid death. These discoveries can also help patients pay less for healthcare long term, by not treating them, but preventing them.

AI could transform biomedical engineering and medicine, by optimizing medical devices, technologies, outcomes and efficiency – at a fraction of the cost. AI has some limitations, but the algorithmic and technical advancements will soon fix these issues and AI systems will be safe, trustworthy and morally designed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the School of Health Sciences at UPES for equipping us with the knowledge and confidence to pursue scientific writing.

References

- Hopfield, JJ. Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1982 Apr;79(8):2554–8. [CrossRef]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-Term Synaptic Plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002 Mar;64(1):355–405. [CrossRef]

- Mandal S, Greenblatt AB, An J. Imaging Intelligence: AI Is Transforming Medical Imaging Across the Imaging Spectrum. IEEE Pulse. 2018 Sep;9(5):16–24. [CrossRef]

- AlQuraishi, M. Machine learning in protein structure prediction. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2021 Dec;65:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González A, Zanin M, Menasalvas-Ruiz E. Public Health and Epidemiology Informatics: Can Artificial Intelligence Help Future Global Challenges? An Overview of Antimicrobial Resistance and Impact of Climate Change in Disease Epidemiology. Yearb Med Inform. 2019 Aug 16;28(01):224–31. [CrossRef]

- VoPham T, Hart JE, Laden F, Chiang YY. Emerging trends in geospatial artificial intelligence (geoAI): potential applications for environmental epidemiology. Environmental Health. 2018 Dec 17;17(1):40. [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, CD. AI planning and scheduling in the medical hospital environment. Artif Intell Med. 2000 Oct;20(2):101–11. [CrossRef]

- Kohn MS, Sun J, Knoop S, Shabo A, Carmeli B, Sow D, et al. IBM’s Health Analytics and Clinical Decision Support. Yearb Med Inform. 2014 Aug 5;23(01):154–62. [CrossRef]

- Kuziemsky C, Maeder AJ, John O, Gogia SB, Basu A, Meher S, et al. Role of Artificial Intelligence within the Telehealth Domain. Yearb Med Inform. 2019 Aug 25;28(01):035–40. [CrossRef]

- Farrokhi A, Farahbakhsh R, Rezazadeh J, Minerva R. Application of Internet of Things and artificial intelligence for smart fitness: A survey. Computer Networks. 2021 Apr;189:107859. [CrossRef]

- Bronzino, JD. Biomedical Engineering Handbook 2. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Springer Science & Business Media, 2000; 2000.

- Kumar P, Sinha R, Shukla P. Artificial intelligence and synthetic biology approaches for human gut microbiome. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022 Mar 20;62(8):2103–21. [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick F, Doherty A, Lacey G. Using Artificial Intelligence in Infection Prevention. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2020 Jun 19;12(2):135–44. [CrossRef]

- Let’s talk about artificial intelligence | United Nations Development Programme [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.undp.org/blog/lets-talk-about-artificial-intelligence.

- Newell A, Simon H. The logic theory machine--A complex information processing system. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 1956 Sep;2(3):61–79. [CrossRef]

- Batta, M. Machine Learning Algorithms - A Review. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR). 2020 Jan;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman JH. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, Second Edition (Springer Series in Statistics). 2nd ed. Springer; 2009. [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani, Z. Unsupervised Learning. In 2004. p. 72–112. [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni PM, Ohno-Machado L, Chapman WW. Natural language processing: an introduction. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2011 Sep 1;18(5):544–51. [CrossRef]

- Köhler S, Carmody L, Vasilevsky N, Jacobsen JOB, Danis D, Gourdine JP, et al. Expansion of the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) knowledge base and resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019 Jan 8;47(D1):D1018–27. [CrossRef]

- Koleck TA, Dreisbach C, Bourne PE, Bakken S. Natural language processing of symptoms documented in free-text narratives of electronic health records: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2019 Apr 1;26(4):364–79. [CrossRef]

- Gu Y, Tinn R, Cheng H, Lucas M, Usuyama N, Liu X, et al. Domain-Specific Language Model Pretraining for Biomedical Natural Language Processing. ACM Trans Comput Healthc. 2022 Jan 31;3(1):1–23. [CrossRef]

- What is Deep Learning? | IBM [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/topics/deep-learning.

- Pustokhina IV, Pustokhin DA, Gupta D, Khanna A, Shankar K, Nguyen GN. An Effective Training Scheme for Deep Neural Network in Edge Computing Enabled Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) Systems. IEEE Access. 2020;8:107112–23. [CrossRef]

- Azghadi MR, Lammie C, Eshraghian JK, Payvand M, Donati E, Linares-Barranco B, et al. Hardware Implementation of Deep Network Accelerators Towards Healthcare and Biomedical Applications. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst. 2020 Dec;14(6):1138–59. [CrossRef]

- Voulodimos A, Doulamis N, Doulamis A, Protopapadakis E. Deep Learning for Computer Vision: A Brief Review. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2018;2018:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Gupta S, Kar AK, Baabdullah A, Al-Khowaiter WAA. Big data with cognitive computing: A review for the future. Int J Inf Manage. 2018 Oct;42:78–89. [CrossRef]

- Chen M, Herrera F, Hwang K. Cognitive Computing: Architecture, Technologies and Intelligent Applications. IEEE Access. 2018;6:19774–83. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Lu C, Huang H, Zhu D, Yang Q, Liu J, et al. Cognitive Computing-Based CDSS in Medical Practice. Health Data Science. 2021 Jan 22;2021. [CrossRef]

- Kenngott HG, Apitz M, Wagner M, Preukschas AA, Speidel S, Müller-Stich BP. Paradigm shift: cognitive surgery. Innov Surg Sci. 2017 Jun 6;2(3):139–43. [CrossRef]

- Danuser, G. Computer Vision in Cell Biology. Cell. 2011 Nov;147(5):973–8. [CrossRef]

- Tek FB, Dempster AG, Kale I. Computer vision for microscopy diagnosis of malaria. Malar J. 2009 Dec 13;8(1):153. [CrossRef]

- Saba, T. Computer vision for microscopic skin cancer diagnosis using handcrafted and non-handcrafted features. Microsc Res Tech. 2021 Jun 5;84(6):1272–83. [CrossRef]

- Goto O, Kaise M, Iwakiri K. Advancements in the Diagnosis of Gastric Subepithelial Tumors. Gut Liver. 2022 May 15;16(3):321–30. [CrossRef]

- Papandrianos NI, Apostolopoulos ID, Feleki A, Moustakidis S, Kokkinos K, Papageorgiou EI. AI-based classification algorithms in SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging for cardiovascular diagnosis: a review. Nucl Med Commun. 2023 Jan 15;44(1):1–11. [CrossRef]

- Xiao Z, Huang Q, Yang Y, Liu M, Chen Q, Huang J, et al. Emerging early diagnostic methods for acute kidney injury. Theranostics. 2022;12(6):2963–86. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary V, Khanna V, Ahmed Awan HT, Singh K, Khalid M, Mishra YK, et al. Towards hospital-on-chip supported by 2D MXenes-based 5th generation intelligent biosensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 2023 Jan;220:114847. [CrossRef]

- Vijayan RSK, Kihlberg J, Cross JB, Poongavanam V. Enhancing preclinical drug discovery with artificial intelligence. Drug Discov Today. 2022 Apr;27(4):967–84. [CrossRef]

- Hung TNK, Le NQK, Le NH, Van Tuan L, Nguyen TP, Thi C, et al. An AI-based Prediction Model for Drug-drug Interactions in Osteoporosis and Paget’s Diseases from SMILES. Mol Inform. 2022 Jun 22;41(6). [CrossRef]

- von Gerich H, Moen H, Block LJ, Chu CH, DeForest H, Hobensack M, et al. Artificial Intelligence -based technologies in nursing: A scoping literature review of the evidence. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022 Mar;127:104153. [CrossRef]

- Nursing shortage ‘the greatest threat to global health’, says ICN | Nursing in Practice [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.nursinginpractice.com/latest-news/nursing-shortage-the-greatest-threat-to-global-health-says-icn/.

- Glette MK, Aase K, Wiig S. The Relationship between Understaffing of Nurses and Patient Safety in Hospitals—A Literature Review with Thematic Analysis. Open J Nurs. 2017;07(12):1387–429. [CrossRef]

- Kitaguchi D, Takeshita N, Hasegawa H, Ito M. Artificial intelligence-based computer vision in surgery: Recent advances and future perspectives. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2022 Jan 8;6(1):29–36. [CrossRef]

- Haidegger T, Speidel S, Stoyanov D, Satava RM. Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Surgery—Surgical Robotics in the Data Age. Proceedings of the IEEE. 2022 Jul;110(7):835–46. [CrossRef]

- Mascagni P, Vardazaryan A, Alapatt D, Urade T, Emre T, Fiorillo C, et al. Artificial Intelligence for Surgical Safety. Ann Surg. 2022 May;275(5):955–61. [CrossRef]

- Cobianchi L, Piccolo D, Dal Mas F, Agnoletti V, Ansaloni L, Balch J, et al. Surgeons’ perspectives on artificial intelligence to support clinical decision-making in trauma and emergency contexts: results from an international survey. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2023 Jan 3;18(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Bian Y, Xiang Y, Tong B, Feng B, Weng X. Artificial Intelligence–Assisted System in Postoperative Follow-up of Orthopedic Patients: Exploratory Quantitative and Qualitative Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020 May 26;22(5):e16896. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins BS, Mazmudar A, Driscoll C, Svet M, Goergen J, Kelsten M, et al. Using artificial intelligence (AI) to predict postoperative surgical site infection: A retrospective cohort of 4046 posterior spinal fusions. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020 May;192:105718. [CrossRef]

- Reece AG, Danforth CM. Instagram photos reveal predictive markers of depression. EPJ Data Sci. 2017 Dec 8;6(1):15. [CrossRef]

- Ahsan MM, Luna SA, Siddique Z. Machine-Learning-Based Disease Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Review. Healthcare. 2022 Mar 15;10(3):541. [CrossRef]

- Ahsan MM, Siddique Z. Machine learning-based heart disease diagnosis: A systematic literature review. Artif Intell Med. 2022 Jun;128:102289. [CrossRef]

- Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Genomics [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/educational-resources/fact-sheets/artificial-intelligence-machine-learning-and-genomics.

- Blanco-González A, Cabezón A, Seco-González A, Conde-Torres D, Antelo-Riveiro P, Piñeiro Á, et al. The Role of AI in Drug Discovery: Challenges, Opportunities, and Strategies. Pharmaceuticals. 2023 Jun 18;16(6):891. [CrossRef]

- Hansen K, Biegler F, Ramakrishnan R, Pronobis W, von Lilienfeld OA, Müller KR, et al. Machine Learning Predictions of Molecular Properties: Accurate Many-Body Potentials and Nonlocality in Chemical Space. J Phys Chem Lett. 2015 Jun 18;6(12):2326–31. [CrossRef]

- Jang HY, Song J, Kim JH, Lee H, Kim IW, Moon B, et al. Machine learning-based quantitative prediction of drug exposure in drug-drug interactions using drug label information. NPJ Digit Med. 2022 Jul 11;5(1):88. [CrossRef]

- Olveres J, González G, Torres F, Moreno-Tagle JC, Carbajal-Degante E, Valencia-Rodríguez A, et al. What is new in computer vision and artificial intelligence in medical image analysis applications. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2021 Aug;11(8):3830–53. [CrossRef]

- Lewis JJ, Chihota VN, van der Meulen M, Fourie PB, Fielding KL, Grant AD, et al. “Proof-Of-Concept” Evaluation of an Automated Sputum Smear Microscopy System for Tuberculosis Diagnosis. PLoS One. 2012 Nov 29;7(11):e50173. [CrossRef]

- Pollak JJ, Houri-Yafin A, Salpeter SJ. Computer Vision Malaria Diagnostic Systems—Progress and Prospects. Front Public Health. 2017 Aug 21;5. [CrossRef]

- xRapid-Lab: the malaria parasite counter - Free download and software reviews - CNET Download [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 15]. Available from: https://download.cnet.com/xrapid-lab-the-malaria-parasite-counter/3000-2129_4-78389013.html.

- Kumar N, Narayan Das N, Gupta D, Gupta K, Bindra J. Efficient Automated Disease Diagnosis Using Machine Learning Models. J Healthc Eng. 2021 May 4;2021:1–13. [CrossRef]

- MacLean AR, Gunson R. Automation and standardisation of clinical molecular testing using PCR.Ai – A comparative performance study. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2019 Nov;120:51–6. [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar M, Rengaswamy R, Raman K. Multi-Omic Data Improve Prediction of Personalized Tumor Suppressors and Oncogenes. Front Genet. 2022 May 10;13. [CrossRef]

- Thomasian NM, Kamel IR, Bai HX. Machine intelligence in non-invasive endocrine cancer diagnostics. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022 Feb 9;18(2):81–95. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Gao W. Wearable and flexible electronics for continuous molecular monitoring. Chem Soc Rev. 2019;48(6):1465–91. [CrossRef]

- He X, Xu T, Gu Z, Gao W, Xu LP, Pan T, et al. Flexible and Superwettable Bands as a Platform toward Sweat Sampling and Sensing. Anal Chem. 2019 Apr 2;91(7):4296–300. [CrossRef]

- Seshadri DR, Li RT, Voos JE, Rowbottom JR, Alfes CM, Zorman CA, et al. Wearable sensors for monitoring the physiological and biochemical profile of the athlete. NPJ Digit Med. 2019 Jul 22;2(1):72. [CrossRef]

- Yu L, Yang Z, An M. Lab on the eye: A review of tear-based wearable devices for medical use and health management. Biosci Trends. 2019 Aug 31;13(4):308–13. [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Liu C, Xu T, Su L, Zhang X. Artificial intelligence biosensors: Challenges and prospects. Biosens Bioelectron. 2020 Oct;165:112412. [CrossRef]

- Mimee M, Nadeau P, Hayward A, Carim S, Flanagan S, Jerger L, et al. An ingestible bacterial-electronic system to monitor gastrointestinal health. Science (1979). 2018 May 25;360(6391):915–8. [CrossRef]

- Salim A, Lim S. Recent advances in noninvasive flexible and wearable wireless biosensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 2019 Sep;141:111422. [CrossRef]

- Fagherazzi G, Fischer A, Ismael M, Despotovic V. Voice for Health: The Use of Vocal Biomarkers from Research to Clinical Practice. Digit Biomark. 2021 Apr 16;5(1):78–88. [CrossRef]

- Usman M, Gunjan VK, Wajid M, Zubair M, Siddiquee KN e alam. Speech as a Biomarker for COVID-19 Detection Using Machine Learning. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022 Apr 18;2022:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ning D, Zhang Z, Qiu K, Lu L, Zhang Q, Zhu Y, et al. Efficacy of intelligent diagnosis with a dynamic uncertain causality graph model for rare disorders of sex development. Front Med. 2020 Aug 17;14(4):498–505. [CrossRef]

- Tran DC, Dang AL, Hoang TNL, Nguyen CT, Dinh TNM, Tran VA, et al. PREVALENCE OF THALASSEMIA IN THE VIETNAMESE POPULATION AND BUILDING A CLINICAL DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEM FOR PRENATAL SCREENING FOR THALASSEMIA. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2023 Apr 28;15(1):e2023026. [CrossRef]

- Ayyıldız H, Arslan Tuncer S. Determination of the effect of red blood cell parameters in the discrimination of iron deficiency anemia and beta thalassemia via Neighborhood Component Analysis Feature Selection-Based machine learning. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 2020 Jan;196:103886. [CrossRef]

- Das R, Saleh S, Nielsen I, Kaviraj A, Sharma P, Dey K, et al. Performance analysis of machine learning algorithms and screening formulae for β–thalassemia trait screening of Indian antenatal women. Int J Med Inform. 2022 Nov;167:104866. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).