Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

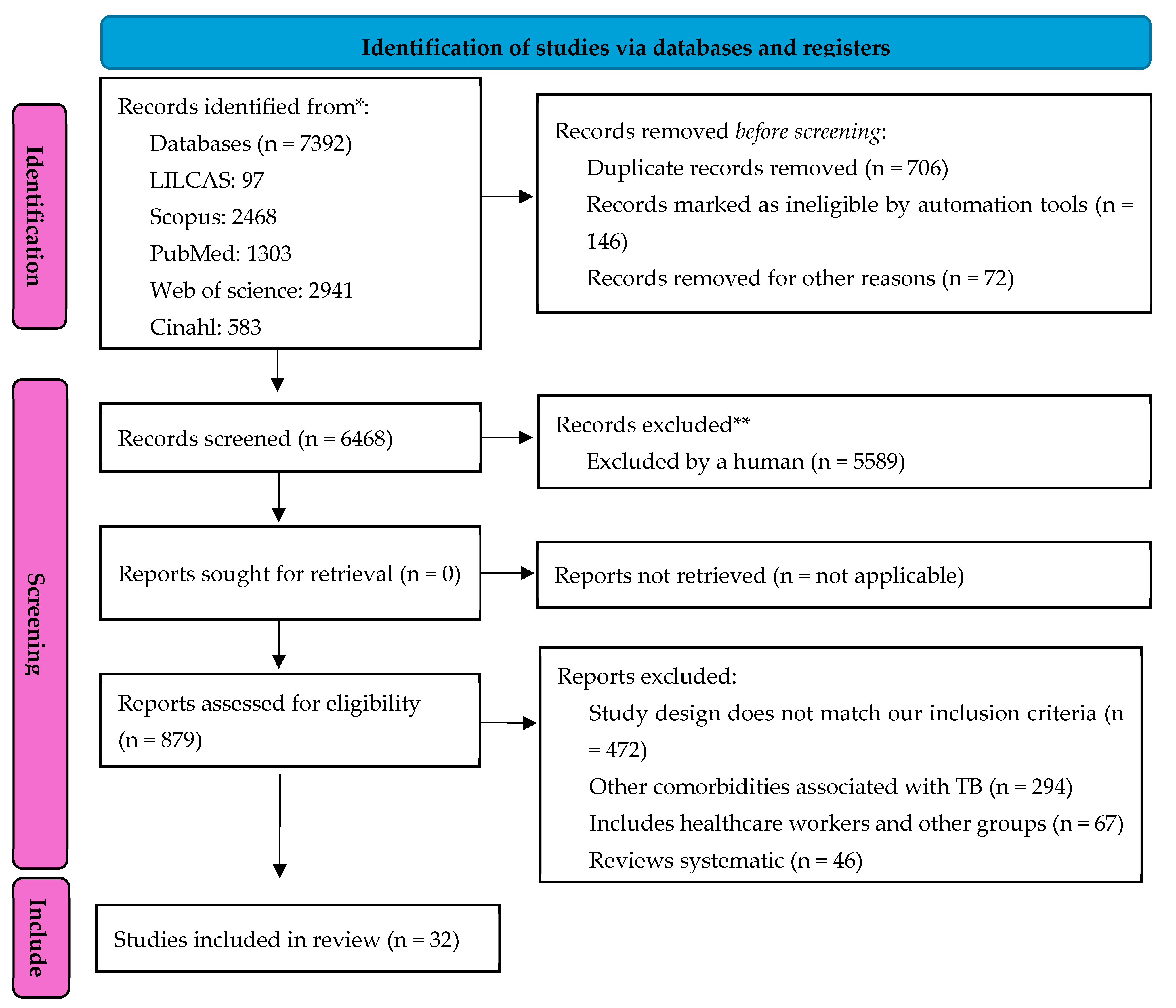

2. Materials and Methods

Protocol and Registration

Research Question and Eligibility Criteria

Data Source Search

Search Strategy

Study Selection Process

Data Extraction, Processing, and Analysis Process

Evaluation of Methodological Quality

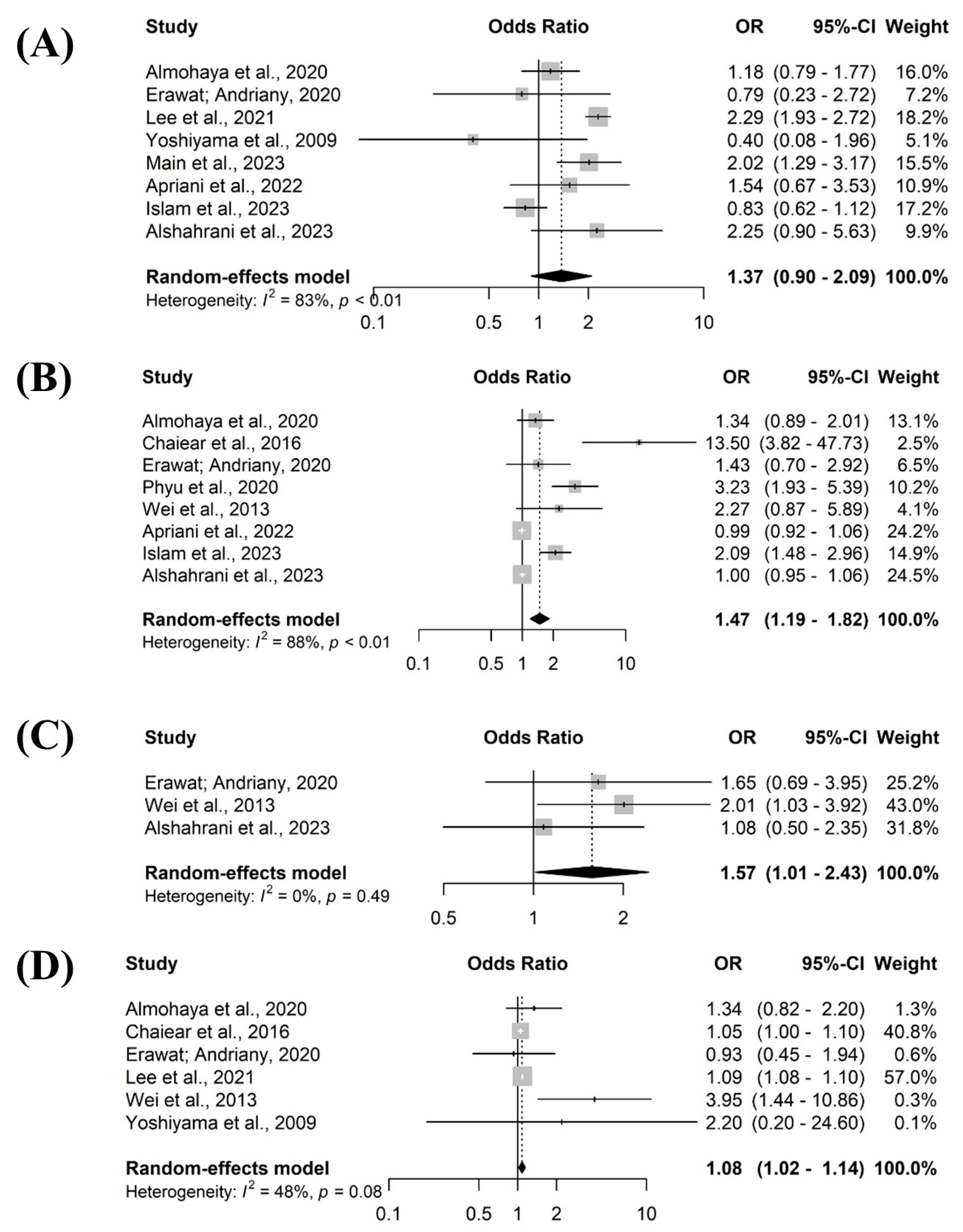

Meta-Analysis

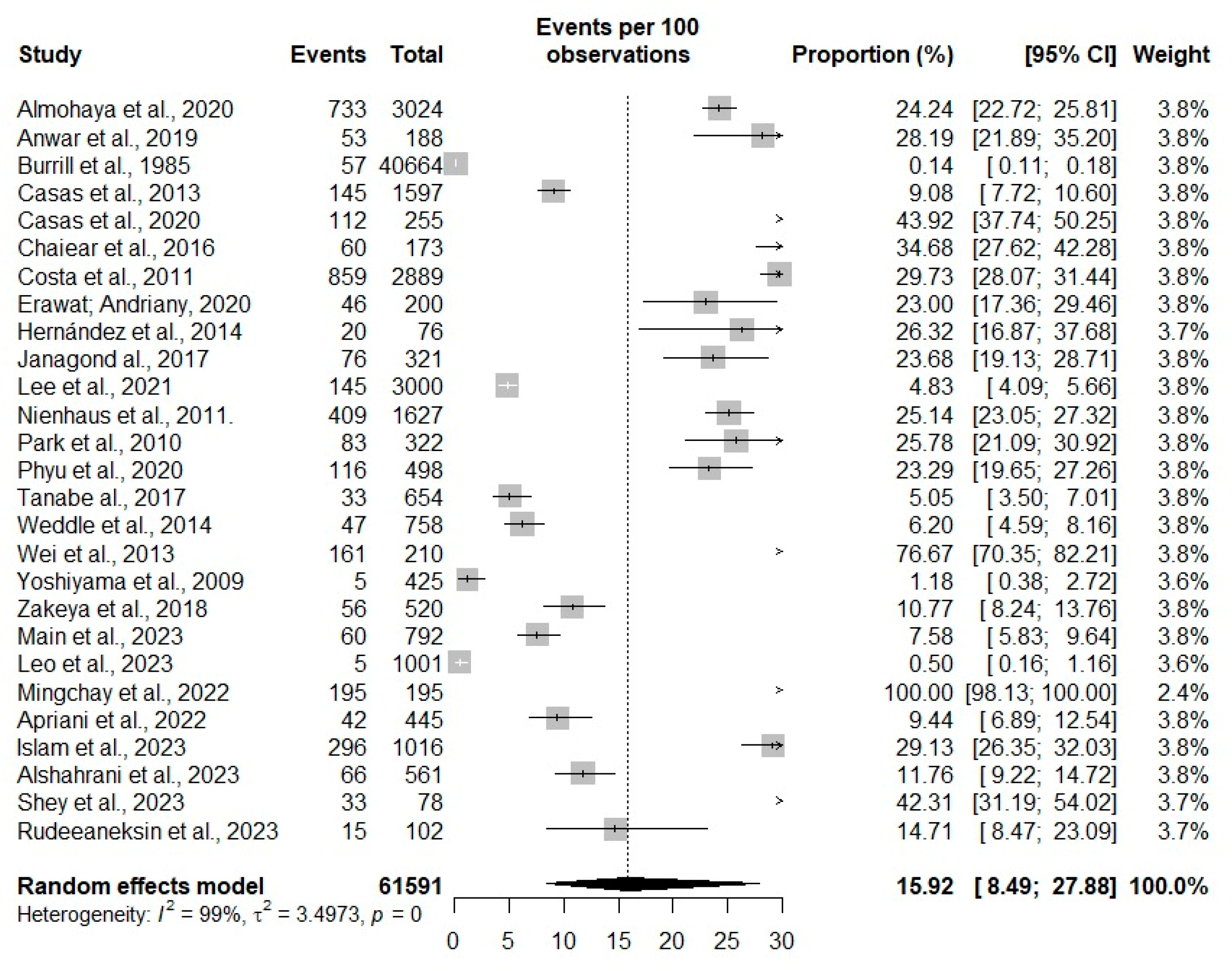

3. Results

Descriptive Characteristics and Quality of Included Studies

Prevalence of Tuberculosis Among Healthcare Workers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lv H, Zhang X, Zhang X, et al. Global prevalence and burden of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis from 1990 to 2019. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1):243. [CrossRef]

- Silva TC, Pinto ML, Orlandi GM, et al. Tuberculosis from the perspective of men and women. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2022;56:e20220137. [CrossRef]

- Amare D, Getahun FA, Mengesha EW, et al. Effectiveness of healthcare workers and volunteers training on improving tuberculosis case detection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18(3):e0271825. [CrossRef]

- Chitwood MH, Alves LC, Bartholomay P, et al. A spatial-mechanistic model to estimate subnational tuberculosis burden with routinely collected data: An application in Brazilian municipalities. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2(9):e0000725. [CrossRef]

- Ryuk DK, Pelissari DM, Alves K, et al. Predictors of unsuccessful tuberculosis treatment outcomes in Brazil: an analysis of 259,484 patient records. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1):531. [CrossRef]

- Żukowska L, Zygała-Pytlos D, Struś K, et al. An overview of tuberculosis outbreaks reported in the years 2011-2020. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):253. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Tuberculosis: Epidemiological Bulletin. 1st ed. Brazil: Ministry of Health, 2022.

- Santos MNA, Sá AMM, Quaresma JAS. Meanings and senses of being a health professional with tuberculosis: an interpretative phenomenological study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e035873. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Brazil Free of Tuberculosis: National Plan to End Tuberculosis as a Public Health Problem. Ministry of Health, Secretariat of Health Surveillance, Department of Communicable Disease Surveillance. – Brasília: Ministry of Health, 2017.

- Pustiglione M, Galesi VMN, Santos LAR, et al. Tuberculosis in health care workers: a problem to be faced. Rev Med 2020;99(1):16-26. [CrossRef]

- Monroe LW, Johnson JS, Gutstein HB, et al. Preventing spread of aerosolized infectious particles during medical procedures: A lab-based analysis of an inexpensive plastic enclosure. PLoS One. 2022;17(9):e0273194. [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw MB, Sinishaw MA, Amare D, et al. Prevalence of active tuberculosis disease among healthcare workers and support staff in healthcare settings of the Amhara region, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0253177. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2019. Geneva: WHO, 2019.

- Caruso E, Mangan JM, Maiuri A, et al. Tuberculosis Testing and Latent Tuberculosis Infection Treatment Practices Among Health Care Providers - United States, 2020-2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(44):1183-1189. [CrossRef]

- Silva EH, Lima E, Santos TR, et al. Prevalence and incidence of tuberculosis in health workers: A systematic review of the literature. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50(7):820-827. [CrossRef]

- Sossen B, Richards AS, Heinsohn T, et al. The natural history of untreated pulmonary tuberculosis in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(4):367-379. [CrossRef]

- Ismail H, Reffin N, Wan Puteh SE, et al. Compliance of Healthcare Worker’s toward Tuberculosis Preventive Measures in Workplace: A Systematic Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(20):10864. [CrossRef]

- Klayut W, Srisungngam S, Suphankong S, et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Result Features in the Detection of Latent Tuberculosis Infection in Thai Healthcare Workers Using QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus. Cureus. 2024;16(5):e60960. [CrossRef]

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence — JBI manual for evidence synthesis—JBI Global Wiki. 2020.

- Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evidence Synthesis 18(10):p 2127-2133. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical appraisal tools—critical appraisal tools | JBI. 2020.

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer G. General package for meta-analysis. 4.19–1. 2021.

- Silva EH, Lima E, Santos TR, Padoveze MC. Prevalence and incidence of tuberculosis in health workers: A systematic review of the literature. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50(7):820-827. [CrossRef]

- Meregildo-Rodriguez ED, Yuptón-Chávez V, Asmat-Rubio MG, et al. Latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) in health-care workers: a cross-sectional study at a northern Peruvian hospital. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1295299. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Ren Y, Liu K, et al. Large gap between attitude and action in tuberculosis preventive treatment among tuberculosis-related healthcare workers in eastern China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:991400. [CrossRef]

- Main S, Triasih R, Greig J, et al. The prevalence and risk factors for tuberculosis among healthcare workers in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0279215. [CrossRef]

- Pustiglione M, Galesi VMN, Santos LAR, et al. Tuberculosis in health care workers: a problem to be faced. Rev Med (São Paulo). 2020;99(1):16-26. [CrossRef]

- Alsayed SSR, Gunosewoyo H. Tuberculosis: Pathogenesis, Current Treatment Regimens and New Drug Targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5202. [CrossRef]

- Azeredo ACV, Holler SR, Almeida EGC, et al. Tuberculosis in Health Care Workers and the Impact of Implementation of Hospital Infection-Control Measures. Workplace Health & Safety. 2020;68(11):519-525. [CrossRef]

- Verbeek JH, Rajamaki B, Ijaz S, et al. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5(5):CD011621. [CrossRef]

- Baral MA, Koirala S. Knowledge and Practice on Prevention and Control of Tuberculosis Among Nurses Working in a Regional Hospital, Nepal. Front Med. 2022;8:788833. [CrossRef]

- Danielle P, Maria-Catarina M, Fabiana S, et al. Occupational tuberculosis: document analysis of a university hospital in Rio de Janeiro. Rev. Cubana Enfermer. 2015; 31 (4). http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-03192015000400002&lng=e.

- Ministry of Health. Guidelines for the prevention and diagnosis of tuberculosis in healthcare professionals. Brasília: Ministry of Health, 2021. 36 p.

- Kim JY, Jung J, Jung KJ, et al. Frequency of and risk factors for reversion of QuantiFERON test in healthcare workers in an intermediate-tuberculosis-burden country. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021 ;27(8):1120-1123. [CrossRef]

- Qader GQ, Seddiq MK, Rashidi KM, et al. Prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection among health workers in Afghanistan: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252307. [CrossRef]

- Zielinski N, Stranzinger J, Zeeb H, et al. Latent Tuberculosis Infection among Health Workers in Germany-A Retrospective Study on Progression Risk and Use of Preventive Therapy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):7053. [CrossRef]

- Aldhawyan NM, Alkhalifah AK, Kofi M, et al. Prevalence of Latent Tuberculosis Infection Among Nurses Working in Critical Areas at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2024;16(2):e53389. [CrossRef]

- Tudor C, Walt MLV, Margot B, et al. Occupational Risk Factors for Tuberculosis Among Healthcare Workers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 May 15;62 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S255-61. [CrossRef]

- Prado TN, Galavote HS, Brioshi AP, et al. Epidemiological profile of reported cases of tuberculosis among health professionals at the University Hospital in Vitória (ES) Brazil. J bras pneumol. 2008;34(8):607-13. [CrossRef]

- Aksornchindarat W, Yodpinij N, Phetsuksiri B, et al. T-SPOT®.TB test and clinical risk scoring for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection among Thai healthcare workers. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2021;54(2):305-311. [CrossRef]

- Vega V, Cabrera-Sanchez J, Rodríguez S, et al. Risk factors for pulmonary tuberculosis recurrence, relapse and reinfection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2024;11(1):e002281. [CrossRef]

| ID | AUTHOR (DATE) | 1. Is the sampling frame appropriate to address the target population? | 2. Were study participants sampled appropriately? | 3. Was the sample size adequate? | 4. Were the participants and study design described in detail? | 5. Was data analysis performed with sufficient sample coverage? | 6. Were valid methods used to identify the condition? | 7. Was condition measured in a standardized and reliable manner? | 8. Was there appropriate statistical analysis? | 9. Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed correctly? | Final score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 78 | Main et al., 2023 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 9 |

| 570 | Leo et al., 2023 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (I) | (I) | (+) | 7 |

| 6321 | Islam et al., 2023 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (-) | (+) | (I) | (-) | (+) | 5 |

| 6323 | Alshahrani et al., 2023 | (+) | (-) | (+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 6 |

| 6330 | Shey et al., 2023 | (I) | (I) | (I) | (-) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 3 |

| 6337 | Rudeeaneksin et al., 2023 | (I) | (I) | (I) | (-) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 4 |

| 6298 | Apriani et al., 2022 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 9 |

| 574 | Mingchay et al., 2022 | (I) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 4 |

| 1372 | Phyu et al., 2020 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (I) | 8 |

| 1376 | Casas et al., 2020 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 9 |

| 1417 | Erawat; Andriany, 2020 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 7 |

| 1448 | Janagond al., 2017 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (I) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 7 |

| 1455 | Anwar et al., 2019 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 8 |

| 1490 | Zakeya et al., 2018 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 9 |

| 1572 | Raitio et al., 2003 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (I) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 9 |

| 2020 | Costa et al., 2011 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 8 |

| 2234 | Casas et al., 2013 | (+) | (-) | (I) | (-) | (I) | (+) | (I) | (+) | (+) | 4 |

| 2491 | Lee et al., 2021 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 8 |

| 3784 | Chaiear et al., 2016 | (+) | (-) | (+) | (-) | (I) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (+) | 3 |

| 4075 | Wei et al., 2013 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (I) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 7 |

| 4225 | Nienhaus et al., 2011. | (+) | (-) | (+) | (-) | (I) | (+) | (I) | (+) | (+) | 5 |

| 4271 | Park et al., 2010 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (I) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 8 |

| 4336 | Yoshiyama et al., 2009 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 8 |

| 4478 | Drobniewski et al., 2007 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 9 |

| 4572 | Gopinatha et al., 2003 | (-) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 5 |

| 5481 | Weddle et al., 2014 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 7 |

| 5503 | Burrill et al., 1985 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 7 |

| 5829 | Costa et al., 2009 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 9 |

| 5839 | Tanabe al., 2017 | (+) | (I) | (+) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 7 |

| 6145 | Almohaya et al., 2020 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 9 |

| 6329 | Ringshausen et al 2011 | (I) | (+) | (I) | (-) | (I) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 5 |

| 6436 | Hernández et al., 2014 | (I) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (I) | 3 |

| ID | Title | Authors/years | Journal | Location | Study design | Level of care | Workers investigated | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 78 | The prevalence and risk factors for tuberculosis among healthcare workers in Yogyakarta, Indonesia | Main et al., 2023 | Plos One | Indonesia | Cross-sectional | Primary care And Medium complexity |

Doctor, nurse, dentist, nutritionist, and pharmacist. | 792 |

| 570 | Active case finding for tuberculosis among health care workers in a teaching hospital, Puducherry, India | Leo et al., 2023 | Indian J Occup Environ Med. | India | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Doctor, nurse, and laboratory yechnician | 1001 |

| 6321 | Prevalence and incidence of TB infection among healthcare workers in chest diseases hospitals, Bangladesh: Putting infection control into context. | Islam et al., 2023 | Plos One | Bangladesh | Prospectivo | High complexity | Doctor, nurses, pharmacists, administrative staff, laboratory team, and auxiliary workers | 1.016 |

| 6323 | The Risk of Latent Tuberculosis Infection Among Healthcare Workers at a General Hospital in Bisha, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. | Alshahrani et al., 2023 | Cureus | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Doctor, nurses and Other technicians | 561 |

| 6330 | Mycobacterial-specific secretion of cytokines and chemokines in healthcare workers with apparent resistance to infection with Mycobacterium TB. | Shey et al., 2023 | Front Immunol | South Africa | Cross-sectional | Primary care And Medium complexity |

Healthcare professionals | 78 |

| 6337 | QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus and QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-tube assays for detecting latent TB infection in Thai healthcare workers. | Rudeeaneksin et al., 2023 | Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo | Thailand | Cross-sectional | Medium complexity | Healthcare professionals | 102 |

| 574 | Tuberculosis at a university hospital, Thailand: A surprising incidence of TB among a new generation of highly exposed health care workers who may be asymptomatic | Mingchay et al., 2022 | Plos One | Thailand | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Healthcare professionals | 195 |

| 6298 | Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and disease in healthcare workers in a tertiary referral hospital in Bandung, Indonesia. | Apriani et al., 2022 | J Infect Prev | Thailand | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Doctor, nurses, nutritionists, pharmacists, midwives, and dentists | 445 |

| 2491 | Decreased annual risk of TB infection in South Korean healthcare workers using interferon-gamma release assay between 1986 - 2005 | Lee et al., 2021 | BMC Infectious Diseases | South Korea | Cross-sectional retrospective | High complexity | Doctors, nursing staff, pharmacists, physiotherapists, administrative staff, and cleaners | 3.233 |

| 1372 | Comparison of Latent Tuberculosis Infections among General versus Tuberculosis Health Care Workers in Myanmar | Phyu, et al., 2020 | Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease | Asia | Cross-sectional | Medium complexity | Nursing staff, doctors, pharmacists, administrative staff | 500 |

| 1376 | Serial testing of health care workers for TB infection: A prospective cohort study | Casas, et al., 2020 | Plos One | Spain | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Nursing staff, doctors, pharmacists, administrative staff | 255 |

| 1417 | The Prevalence and Demographic Risk Factors for Latent TB Infection Among Healthcare Workers in Semarang, Indonesia | Erawat; Andriany, 2020 | J Multidiscip Healthc | Indonesia | Cross-sectional | Primary care | Nursing staff, doctors, pharmacists, administrative staff, and cleaners | 195 |

| 6145 | Latent tuberculosis infection among health-care workers using Quantiferon-TB Gold-Plus in a country with a low burden for TB: prevalence and risk factors | Almohaya et al., 2020 | ASM Annals of Saudi Medicine | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional and case control | High complexity | Doctors, nurses, laboratory technicians, and radiology technicians | 3.024 |

| 1455 | Screening for Latent TB among Healthcare Workers in an Egyptian Hospital Using Tuberculin Skin Test and QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube Test | Anwar et al., 2019 | Indian Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine | Egypt | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Nursing staff, doctors, pharmacists, administrative staff, and cleaners | 153 |

| 1490 | Screening of latent TB infection among health care workers working in Hajj pilgrimage area in Saudi Arabia, using interferon gamma release assay and tuberculin skin test | Zakeya et al., 2018 | ASM Annals of Saudi Medicine Saudita | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional prospective | High complexity | Nursing staff and doctors | 520 |

| 1448 | Screening of health-care workers for latent tuberculosis infection in a Tertiary Care Hospital | Janagond al., 2017 | International Journal of Mycobacteriology | India | Prospective | High complexity | Nursing staff, doctors, pharmacists, administrative staff, and cleaners | 2.290 |

| 5839 | The Direct Comparison of Two Interferon-gamma Release Assays in the TB Screening of Japanese Healthcare Workers | Tanabe al., 2017 | Internal Medicine | Japan | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Doctors, nursing staff, pharmacists, physiotherapists, administrative staff, and cleaners | 654 |

| 3784 | Age is associated with latent tuberculosis in nurses | Chaiear et al., 2016 | Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease | Thailand | Comparative study | High complexity | Nurses and nursing assistants | 213 |

| 5481 | QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube Testing for Tuberculosis in Healthcare Professionals | Weddle et al., 2014 | Oxford Academic | United States | Cohort | High complexity | Doctors, nursing staff, pharmacists, physiotherapists, administrative staff and cleaners | 758 |

| 6436 | Latent TB infection screening in healthcare workers in four large hospitals in Santiago, Chile | Hernández et al., 2014 | Revista Chilena de Infectologia | Chile | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, technologists, technical, and administrative assistants | 76 |

| 2234 | Incidence of tuberculosis infection among healthcare workers: risk factors and 20-year evolution | Casas et al., 2013 | Medicina Respiratória | Spain | Prospective cohort | High complexity | Doctors, nursing staff, pharmacists, physiotherapists, administrative staff. and cleaners | 614 |

| 4075 | Prevalence of latent TB infection among healthcare workers in China as detected by two interferon-gamma release assays | Wei et al., 2013 | Journal of Hospital Infection | China | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Doctors, nursing staff, pharmacists, physiotherapists, administrative staff and cleaners | 210 |

| 2020 | Screening for tuberculosis and prediction of disease in Portuguese healthcare workers. | Costa et al., 2011 | Journal of occupational Medicine and Toxicology | Portugal | Cohort | Medium complexity | Nursing staff, doctors, pharmacists, administrative staff, and cleaners | 2.889 |

| 4225 | The prevalence of latent tuberculosis infections among health-care workers - A three-country comparison | Nienhaus et al., 2011 | Pneumologie | Germany | Cohort | High complexity | Doctors, nursing staff, pharmacists, physiotherapists, administrative staff, and cleaners | 2.028 |

| 6329 | Within-Subject Variability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-Specific Gamma Interferon Responses in German Health Care Workers | Ringshausen et al 2011 | CVI Clinical and Vaccine Immunology | Germany | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Doctors, nursing staff, pharmacists, physiotherapists, administrative staff, and cleaners | 35 |

| 4271 | Interferon-γ release assay for TB screening of healthcare workers at a Korean tertiary hospital | Park et al., 2010 | Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases | South Korea | Clinical trial | High complexity | Doctors and nurses | 322 |

| 4336 | Estimation of incidence of tuberculosis infection in health-care workers using repeated interferon-γ assays | Yoshiyama et al., 2009 | Epidemiology E Infection | Japan | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Doctors, nursing staff, pharmacists, physiotherapists, administrative staff, and cleaners | 425 |

| 5829 | TB screening in Portuguese healthcare workers using the tuberculin skin test and the interferon-gamma release assay | Costa et al., 2009 | European Respiratory Journal | Portugal | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Doctors, nursing staff, pharmacists, physiotherapists, administrative staff, and cleaners | 4.735 |

| 4478 | Rates of latent tuberculosis in health care staff in Russia | Drobniewski et al., 2007 | Plos Medicine | Russia | Cross-sectional | Primary care and High complexity | Doctors, nursing staff, pharmacists, physiotherapists, administrative staff, cleaners, nursing, and medical students | 630 |

| 1572 | Is the risk of occupational tuberculosis higher for young health care workers? | Raitio et al., 2003 | The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease | Finland | Cross-sectional | High complexity | Equipe de Enfermagem, Médicos e funcionários administrativos. | 447 |

| 4572 | Tuberculosis among healthcare workers in a tertiary-care hospital in South India | Gopinatha et al., 2003 | The Journal of Hospital Infection | India | Cohort | High complexity | Doctors, Nursing Staff, Pharmacists, Physiotherapists, Administrative Staff | 125 |

| 5503 | TB in female nurses in british-columbia - implications for control programs | Burrill et al., 1985 | Canadian Medical Association Journal | Canada | Cross-sectional | Medium complexity | Nurses | 57 |

| ID | Factors associated with tuberculosis |

|---|---|

| 1372 | The risk factors for ILTB included: education level below higher education, 10 or more years of service, insufficient knowledge about regular TB screening, and teaching cough etiquette to TB patients. |

| 1376 | The factors associated with a positive TT or IGRA test were: BCG vaccination status and the degree of occupational exposure to tuberculosis. |

| 1417 | Healthcare workers with current diseases (DM and hepatitis) were more susceptible to LTBI (OR = 3.39, 95% CI: 0.99–11.62, p = 0.04), and midwives were at higher risk of LTBI than other healthcare professions. |

| 1448 | The factors were high exposure to TB patients in the absence of TB control measures. Furthermore, the analysis suggested that age, years of service, literacy, and working in wards/ICU were associated with TB infection. |

| 1455 | Among the participants with a positive test, all had more than 10 years of professional experience, a history of BCG vaccination, were diabetic, and were active smokers. |

| 1490 | The average age and duration of employment were significantly higher in the positive participants. |

| 1572 | Among nurses, nursing assistants, and doctors, the incidence rate was higher in the 20-39 age group. |

| 2020 | Age (50 years or older) and the number of years working in healthcare services increase the likelihood of positive TST and IGRA results (higher OR of 2.5 for working 20 years or more in healthcare). Repeated BCG vaccination was associated with a reduced likelihood of a positive IGRA. |

| 2234 | The cumulative incidence was higher among healthcare workers working in high-risk areas during the periods from 1990 to 1995. The majority were women, with an average age of 31 years. |

| 2491 | The multivariate analysis indicated that advanced age, healed TB lesions on chest X-ray, and male sex were risk factors for positive IGRA, while working in high-risk TB departments was not. |

| 3784 | Advanced age, male sex, longer duration of employment, having BCG scars, family history of TB, TB in the past year, prevention by any methods, and the use of surgical masks. |

| 4075 | Age >30 years and working in a chest hospital for more than five years were significantly associated with a positive QFT-GIT result and TB. Furthermore, in the multivariate analysis, age >30 years and working as a nurse were associated with a positive QFT-GIT result and TB. |

| 4225 | Age over 55 years, family history of TB, migration from a country with high TB incidence, prolonged contact (>40 hours) with a sputum-positive index case (OR = 18.6). |

| 4271 | History of BCG vaccination was significant for TB. |

| 4336 | Staff working in TB isolation wards were more likely to have a positive QFT-G response (OR 8.6, 95% CI 1.4–54). |

| 4478 | The proportion of people diagnosed with ILTB was higher among doctors and nurses in primary care compared to the low-exposure medical student group, and among doctors and nurses compared to primary healthcare workers or medical students. |

| 4572 | They occurred in individuals under 32 years of age, with a higher incidence among nurses (25.6%) and nursing students (19.2%). |

| 5481 | The risk factors associated with TB were living in a country where TB is endemic and receiving the BCG vaccination. |

| 5503 | Female sex and caregiving occupations, as well as those whose tuberculin test results were negative but who were not vaccinated, had twice the likelihood of contracting TB. |

| 5829 | The likelihood of a positive IGRA increased with the diameter of the TT induration, age, and years spent as a healthcare professional. A positive IGRA was less likely when ≤ 10 years had passed since the last vaccination. |

| 5839 | Having a previous chest X-ray and/or IGRA abnormalities, a history of TB treatment, comorbidities associated with immunodeficiency, and a history of TB exposure. |

| 6145 | Higher risk of ILTB was present in healthcare professionals over 50 years of age, working as nurses and radiology technicians, and working in the emergency department or intensive care unit. |

| 6329 | Age was significantly associated with IGRAs (P < 0.05). |

| 6436 | A higher proportion of latent TB infection was found in older age. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).