1. Introduction

The disease caused by dengue virus (DENV) is endemic in more than 100 countries in tropical and subtropical regions [

1]. There has been a drastic increase in the incidence of dengue fever in the Americas from 2003 to 2013 [

2]. The introduction of the Zika virus in 2016 elicited a meaningful reduction in DENV transmission [

3]. Nevertheless, in 2019 DENV reappeared, and its transmission was similar to the outbreak in 2013 [

4].

Dengue disease tends to be a self-limiting febrile illness. However, hospitalized patients have a 5-10% risk of progression to severe dengue, then up to 5% of cases may be fatal [

1,

5]. The severe form of the disease is characterized by plasma leakage, hemorrhaging, and shock [

6]. Risk factors of severe DENV include serotype, secondary infections, and some individual conditions, like comorbidities and genetics factors [

6,

7]. Currently, it is unclear which patients may develop complications. Therefore, it is crucial to explore early prognostic biomarkers of severe dengue. Prognostic biomarkers at the first hours of the disease could facilitate more efficient and preventative management of patients with a higher risk of developing the severe disease.

The oxidative stress generated during the acute phase has been associated with the pathogenesis of various diseases, including viral infections [

8]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation could stimulate the secretion of proinflammatory mediators and trigger apoptosis in endothelial cells [

9,

10]; however, this and other effects are mainly counter-regulated by antioxidants such as catalase, glutathione, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) [

11]. The imbalance between ROS and the antioxidant molecules can potentially increase vascular permeability, a hallmark of severe dengue [

10,

12].

Observational studies conducted in patients with dengue have reported alterations in oxidative activity [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. These include changes in the activity of glutathione peroxidase (GPX), the concentration of superoxide dismutase (SOD), and total antioxidant status (TAS); however, these results are not conclusive. Considering the relationship between oxidative stress and vascular permeability, we aimed to evaluate the role of SOD, GPx, and TAS as prognostic biomarkers of dengue hypotensive and hemorrhagic complications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a nested case-control study within a cohort of febrile patients with no apparent infectious focus after undergoing a physical examination. Participants were enrolled in ambulatory health care services in five cities with high DENV transmission in Colombia (Bucaramanga, Piedecuesta, Floridablanca, Palmira, and Barranquilla), from May 2009 to April 2011. Those municipalities have reported average incidence rates between 147.3 and 559.9 per 100.000 inhabitants in the last decade [

18]. Eligible participants of the cohort were ≥5 years of age and were diagnosed with dengue acute disease of <96 hours of symptoms’ onset before enrolment. We excluded patients with a history of cancer, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, chronic kidney disease, cardiac disease, or hematologic disorders; those who used corticosteroids in the last 8 days, had major bleeding (hematemesis, hematuria, hematochezia or melena) or clinical signs of plasma leakage (pleural effusion, ascites, and hypotension) at enrollment; and those recruited in inpatient services.

Trained physicians obtained demographic and clinical data at enrolment. Acute and convalescent (7-15 days) blood samples were collected to determine a complete blood count (enrolment) and to perform diagnostic tests. Participants were followed daily until the seventh day of the disease to collect clinical information (symptoms and signs) and to determine the microhematocrit. We defined a confirmed dengue case according to a diagnostic algorithm, which included IgM/IgG seroconversion (shift from negative to positive or a titer increase ≥4) in paired sera, a positive NS1 protein result or viral genome amplification per RT-PCR in acute serum (<96 hours post onset of fever) with the use of methods previously described [

19]. Patients with a positive result of IgM in any sample (acute or convalescent) were considered presumptive cases of dengue. Additionally, we considered primary DENV infections to be those with a negative IgG result in the acute sample. IgM and IgG antibodies were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), specifically Dengue IgM/G Capture ELISA PanBio®. The NS1 antigen was quantified with the ELISA NS1 Dengue PanBio®. To detect the viral genome, we extracted the RNA with the QIAamp Viral RNA kit (Qiagen) and then performed a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) based on a previously established method [

20].

2.2. Case-Control Definition

We adopted the dengue case classification suggested by WHO in 2009 [

21]: incident cases were patients with dengue infection (presumptive or confirmed) who developed hypotension or severe bleeding during follow-up. Hypotension was defined as the finding of tachycardia and pulse pressure (PP) lower than 20 mmHg, low mean arterial pressure (MAP) for the age, or low systolic blood pressure (SBP) for the age [

22]. We considered hematemesis, hematuria, hematochezia, and melena as cases of severe bleeding. Controls were randomly selected among patients with presumptive or confirmed dengue infection who did not develop hypotension or severe bleeding during the follow-up [

21].

2.4. Biomarkers Assays

We performed biomarker assays in acute serum samples (stored at -80°C) using Cayman® assay kits (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI) in the Multiskan microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). We measured glutathione peroxidase activity (GPx. Catalog no. 703102), superoxide dismutase concentration (SOD. Catalog no. 709002), and total antioxidant status (TAS, Catalog no. 709001) as antioxidant biomarkers.

Glutathione peroxidase: GPx assay is based on a previously established method [

23], that measures the activity indirectly by a coupled reaction with glutathione reductase. The oxidation of NADPH to NADP+ is accompanied by a decrease in absorbance at 340 nm. The rate of decline in the absorbance is directly proportional to the GPx in the sample. One unit of GPx is defined as the amount of enzyme that causes the oxidation of 1 nmol of NADPH to NADP+ per minute at 25ºC.

Superoxide dismutase: We performed the SOD measurement according to the protocol previously established [

24]. The assay utilizes a tetrazolium salt to detect superoxide radicals generated by xanthine oxidase and hypoxanthine. One unit of SOD is defined as the amount of enzyme needed to produce 50% dismutation of superoxide radical. We measured the absorbance at 450 nm and expressed the concentration in U/mL.

Total antioxidant status: We quantified TAS concentration following the ABTS method [

25]. The assay relies on antioxidants' ability to inhibit metmyoglobin's oxidation of ABTS to ABTS+. We measured the amount of ABTS+ at 750 nm and expressed its concentration in mM.

2.5. Data Analysis

We calculated a total sample size of 132 patients (1:2 case-control ratio) to detect a difference equal to or greater than 20% in the concentration of GPx between groups based on absolute concentrations previously reported in patients with dengue [

13] with a statistical power of 80% and a type I error of 5%. We described continuous variables by estimating the mean and standard deviation (SD) or the median and interquartile range [IQR] for those not normally distributed, according to the Shapiro-Wilk test. We calculated their absolute and relative frequencies (percentages) for discrete variables. We contrasted means and medians between groups using a student’s t-test and the Kruskal-Wallis test, respectively, and differences in proportions using the chi-square test and, alternatively, the Fisher’s exact test whenever the expected counts in contingency tables were less than five. We explored the shape of the functional relationship between each biomarker and the case-control status using locally weighted regression to identify inflection points. Then, we conducted multiple logistic regression with and without piecewise (using the cut-points previously determined) and estimated odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI), forcing the adjustment for age but conditioning it by sex, disease duration at enrollment, or infection type (primary versus secondary) only if these covariates were associated to the case-control status at a significance level of ≤10% in the bivariate analysis. There was no further adjustment for warning signs as they could mediate the associations under study. We evaluated the goodness of fit of the models using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (HL) and selected among them using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Data analysis was conducted using the statistical software Stata/IC, version 14.2.

3. Results

The median age of the 132 subjects was 19.0 years (IQR: 13.0, 35.0 years) of whom 67 (58.2%) were males. Cases were younger than controls (medians: 15.0 versus 24.5 years, p=0.007); however, both groups were similar regarding sex distribution, disease duration, and type of infection (Table 1). In terms of warning signs, cases were more likely to report persisting vomiting and mucosal bleeding than controls at baseline: 6.8% versus 0.0% (p=0.035) and 20.5% versus 0.0% (p<0.001), respectively. TAS and SOD were higher among cases than controls, and the opposite was observed for GPx; however, none of these contrasts reached statistical significance (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of dengue patients, by case-control status.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of dengue patients, by case-control status.

| Characteristic |

Controls

(n=88) |

Cases

(n=44) |

p |

| Age (years) |

24.5 [14.0 - 37.0] |

15.0 [10.0 - 21.5] |

0.007 |

| Age group |

|

|

0.078 |

| 5-14 years |

16 (27.3) |

15 (43.2) |

|

| ≥15 years |

64 (72.7) |

25 (56.8) |

|

| Male |

46 (52.3) |

21 (47.7) |

0.713 |

| Disease onset |

|

|

0.389 |

| 48 hours |

18 (20.5) |

5 (11.4) |

|

| 72 hours |

31 (35.2) |

19 (43.2) |

|

| 94 hours |

39 (44.3) |

20 (45.4) |

|

| Primary infection |

44 (52.4) |

21 (47.7) |

0.851 |

| Warning signs* |

|

|

|

| Persisting vomiting |

0 (0.0) |

3 (6.8) |

0.035 |

| Abdominal pain |

32 (36.4) |

24 (54.5) |

0.561 |

| Clinical fluid accumulation |

22 (25.0) |

6 (13.6) |

0.181 |

| Mucosal bleeding |

0 (0.0) |

9 (20.5) |

<0.001 |

| Lethargy or restlessness |

45 (51.1) |

29 (65.9) |

0.137 |

| Hepatomegaly |

6 (6.8) |

1 (2.3) |

0.423 |

| Laboratory |

|

|

|

| Hemogram |

|

|

|

| Hematocrit (%) |

41.0 (3.5) |

40.8 (3.7) |

0.354 |

| Leukocytes (per/mL) |

3,290 [2,600 - 3,800] |

3,290 [2,600 - 3,800] |

0.940 |

| Platelets (per/mL) |

146,255 (44,709) |

139,180 (46,713) |

0.534 |

| CRP (mg/dL) |

9.6 [1.4 - 20.8] |

11.9 [10.6 - 16.4] |

0.407 |

Table 2.

Oxidative stress biomarkers measured in serum during the acute phase of dengue, by case-control status.

Table 2.

Oxidative stress biomarkers measured in serum during the acute phase of dengue, by case-control status.

| Characteristic |

Controls

(n=88) |

Cases

(n=44) |

p |

| TAS (mM)* |

1.7 [1.2 - 2.3] |

2.1 [1.8 - 2.6] |

0.057 |

| SOD (U/ml)* |

6.0 [5.0 - 7.1] |

6.7 [5.6 - 7.8] |

0.091 |

| GPx (mmol/min/ml) |

133.7 (24.1) |

128.1 (20.2) |

0.190 |

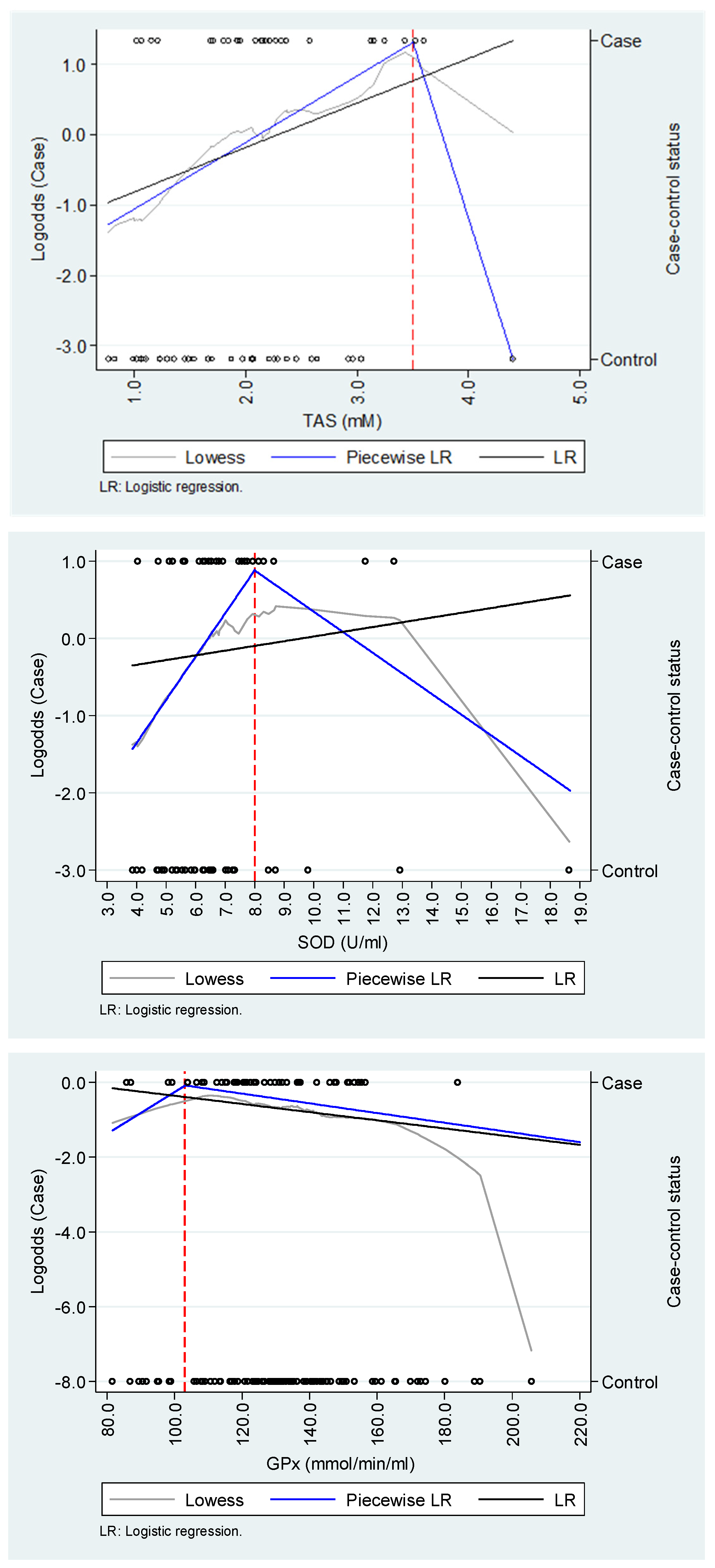

We found evidence of non-linear relationships between TAS and SOD and dengue hypotension or severe bleeding in the explorative analysis; however, they seemed to be highly sensitive to a biologically plausible outlier observation among controls (Figure 1). For TAS and SOD, logistic regression models using a piecewise approach were more parsimonious than those that did not implement it, but the opposite occurred for GPx (Table 3). TAS and SOD were associated with the likelihood of hypotension or severe bleeding up to 3.5 mM (OR=2.46; 95%CI: 1.10 - 5.53) and 8.0 U/mL (OR=1.69; 95%CI: 1.01 - 2.83), respectively; however, we did not find evidence of a relationship for any of those biomarkers above those cut-points. In any regression model, GPx did not show an association with hypotension or severe bleeding.

Figure 1.

Exploration of the functional relationship between oxidative stress biomarkers and dengue complications.

Figure 1.

Exploration of the functional relationship between oxidative stress biomarkers and dengue complications.

Table 3.

Association between oxidative stress biomarkers and dengue complications*.

Table 3.

Association between oxidative stress biomarkers and dengue complications*.

| Biomarker |

Piecewise Logistic regression

OR (95%CI) |

Logistic regression

OR (95%CI) |

| TAS (mM)† |

|

1.80 (0.89 - 3.64) |

| TAS<3.5 |

2.46 (1.10 - 5.53) |

… |

| TAS≥3.5 |

0.01 (0.00 - 406.3) |

… |

| Age |

0.99 (0.96 - 1.02) |

0.98 (0.95 - 1.02) |

| HL / AIC‡ |

0.351 / 82.2 |

0.349 / 83.2 |

| |

|

|

| SOD (U/mL)† |

|

1.04 (0.84 - 1.30) |

| SOD<8.0 |

1.69 (1.01 - 2.83) |

… |

| SOD≥8.0 |

0.77 (0.50 - 1.18) |

… |

| Age |

0.99 (0.96 - 1.02) |

0.98 (0.95 - 1.02) |

| HL / AIC |

0.335 / 83.5 |

0.360 / 85.9 |

| |

|

|

| GPx (mmol/min/ml) |

|

0.99 (0.98 - 1.01) |

| GPx<103.0 |

1.06 (0.94 - 1.19) |

… |

| GPx≥103.0 |

0.99 (0.97 - 1.01) |

… |

| Age |

0.97 (0.95 - 1.00) |

0.97 (0.95 - 1.00) |

| HL / AIC |

0.343 / 167.8 |

0.357 / 167.1 |

| * Hypotension or severe bleeding. † Cases/controls: n=27/32. ‡ HL: P-value corresponding to the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test; AIC: Akaike information criterion. |

4. Discussion

In this nested case-control study, we observed evidence that oxidative stress induction during the acute phase of dengue infection was associated with the incidence of hypotensive and hemorrhagic complications. Specifically, higher levels of the total antioxidant status (TAS) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) but not of glutathione peroxidase (GPx) were associated with a higher likelihood of dengue complications; however, those relationships were exclusively observed for concentrations below 3.5 mM and 8.0 U/mL, respectively.

The literature suggests that oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathogenesis of dengue fever [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

26,

27,

28,

29]. During the acute phase of the infection, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced due to the release of proinflammatory cytokines [30]. In this scenario, an imbalance between ROS generation and the antioxidant defense system leads to oxidative stress and cellular damage [

11,

13]. The evidence consistently shows a down-regulation of genes that encode endogenous enzymatic antioxidants and a lower expression of their products in patients with dengue infection as compared to healthy controls; however, the results from the studies are conflicting when contrasting patients across the spectrum of disease severity [

26,

27]. Further, most of the studies have a case-control design and quantified biomarkers concurrently with the identification of complications, which precludes them from being considered prognostic factors.

Our results show that measured early in the course of the disease, higher levels of the TAS increased the likelihood of progression toward hypotensive and hemorrhagic manifestations. This finding is in alignment with previous observations of higher concentrations of malondialdehyde (MDA), a biomarker of the oxidative stress response, in complicated than uncomplicated dengue patients [

17,

28,

29]; however, it seems to conflict with the report of no difference in TAS between those groups early in the course of the disease but lower TAS in complicated patients evaluated at longer disease duration [

28]. An explanation for this discrepancy might be that prospectively evaluated, as in our study, patients whose disease onset is characterized by a more intense induction of ROS express a higher TAS as a counterregulatory mechanism, a response that declines during follow-up, leading to complications.

We also quantified the concentration of SOD and GPx, two endogenous enzymatic antioxidants that contribute to the TAS. While the concentration of SOD showed a similar predictive value for dengue hypotensive and hemorrhagic complications as the TAS, GPx was not associated with the likelihood of progression. The first finding is novel and partially supported by the observation of a slightly higher SOD gene expression reported by Cherupanakkal et al. in severe as compared to non-severe cases of dengue [

26]. Three more studies have evaluated the concentration of SOD in complicated and uncomplicated dengue patients without finding evidence of statistically significant differences between groups[

13,

15,

17]; however, in at least one, the absolute difference was of a similar magnitude as that we observed in our study [

13]. Regarding GPx, our results are consistent with those previously reported by Rojas et al. from a cohort study conducted in Colombia [

16]. To our knowledge, this is the only longitudinal study that has approached this issue. In addition to the strength derived from its prospective nature, this study showed that a higher baseline concentration of GPx increased the likelihood of spontaneous bleeding at follow-up; however, such a relationship became non statistically significant after adjustment for relevant covariates.

Taken together, our findings are biologically plausive, considering that the dengue virus induces the release of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF-α in infected cells (monocytes, dendritic cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes CD4+ and CD8+), which play a role as pro-oxidants during the acute phase of the disease [31,32]. Furthermore, a positive correlation between TNF-α and MDA, a product of polyunsaturated lipid degradation by ROS, has been reported in complicated but not uncomplicated cases of dengue [30]. The ROS generated during the infection triggers the release of antioxidants molecules, including SOD, GPx, catalase, albumin, ceruloplasmin, ferritin, ascorbic acid, α-tocopherol, β-carotene, reduced glutathione, uric acid, and bilirubin, all of which are included in the measurement of TAS [33]. Considering our results, we propose that the antioxidant response may become overwhelmed and insufficient to control the release of ROS induced by the strong proinflammatory cytokine cascade during the acute phase of dengue in cases that will progress to the severe form of the disease. Moreover, TAS provides a general overview of the antioxidant barrier in plasma, making both TAS and SOD potential prognostic biomarkers of dengue hypotensive and hemorrhagic complications.

Our study has some strengths worth mentioning. First, it is a case-control study nested in a cohort of patients with a diagnosis of dengue, which implies, on the one hand, that cases of hypotensive and hemorrhagic complications were prospectively ascertained (i.e., incident cases) and, on the other, that controls were chosen from the same population that cases which minimizes the risk of selection bias. Secondly, the adjudication of outcomes was performed by trained clinicians blinded to the concentration of the biomarkers of antioxidant status, minimizing the risk of information bias. Thirdly, we tested for and adjusted the associations under study by biologically and clinically relevant confounders. This study also has limitations. We exclusively measured biomarkers of the antioxidant response at the time of admission of participants to the study, which limits our understanding of the dynamic interplay between pro-oxidants and antioxidants as the disease progresses. Although cases and controls were similar regarding the prevalence of primary versus secondary infections, we did not determine the serotype of the index infection, which, if unevenly distributed, could have biased our estimates of association. Finally, there was an outlier observation among the controls that tended to underestimate the strength of the associations; however, it was deemed biologically plausible and, therefore, included in all the statistical models.

In conclusion, our work advanced the understanding of the role of the antioxidant response in patients with dengue through a methodologically robust study design, highlighting the potential of such biomarkers as prognostic factors for developing hypotensive and hemorrhagic complications.

Author Contributions

A.L.P.: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. V.H.: Conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. L.Á.V.: Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, supervision, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, Colciencias (No. 0037 de 2012), Zambon Colombia S.A, Universidad Industrial de Santander and Centro de Atención y Diagnóstico de Enfermedades Infecciosas (CDI), Fundación INFOVIDA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethical Review Committee of the Universidad Industrial de Santander approved the study protocol (Acta No. 09, 25 April 2014).

Informed Consent Statement

We obtained written informed consent from each adult participant. In the case of children, we obtained their assent and informed consent from their parents or legal guardians.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. Due to privacy and ethical restrictions, the data cannot be made publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We thank the AEDES Project (Grant no. 102-459-2156) for providing this study's samples and linked data. We also acknowledge Carolina Villacreses for her support in the laboratory work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Dengue and Dengue Severe Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/.

- Pan American Health Organization. Five-Fold Increase in Dengue Cases in the Americas over the Past Decade Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/29-5-2014-five-fold-increase-dengue-cases-americas-over-past-decade (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Halstead, S. Recent Advances in Understanding Dengue. F1000Research 2019 8:1279 2019, 8, 1279. [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. Dengue Fever Cases in The Americas Available online: https://www3.paho.org/data/index.php/en/mnu-topics/indicadores-dengue-en/dengue-nacional-en/252-dengue-pais-ano-en.html?start=1 (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Alexander, N.; Balmaseda, A.; Coelho, I.C.B.; Dimaano, E.; Hien, T.T.; Hung, N.T.; Jäenisch, T.; Kroeger, A.; Lum, L.C.S.; Martinez, E.; et al. Multicentre Prospective Study on Dengue Classification in Four South-East Asian and Three Latin American Countries. Trop Med Int Health 2011, 16, 936–948. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.P.; Farouk, F.S.; St. John, A.L. Risk Factors and Biomarkers of Severe Dengue. Curr Opin Virol 2020, 43, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Sangkaew, S.; Ming, D.; Boonyasiri, A.; Honeyford, K.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Yacoub, S.; Dorigatti, I.; Holmes, A. Risk Predictors of Progression to Severe Disease during the Febrile Phase of Dengue: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2021, 21, 1014–1026. [CrossRef]

- Akaike, T.; Noguchi, Y.; Ijiri, S.; Setoguchi, K.; Suga, M.; Zheng, Y.M.; Dietzschold, B.; Maeda, H. Pathogenesis of Influenza Virus-Induced Pneumonia: Involvement of Both Nitric Oxide and Oxygen Radicals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1996, 93, 2448–2453. [CrossRef]

- Arango Rincón, J.C.; Gómez Díaz, L.Y.; López Quintero, J.Á. Sistema NADPH Oxidasa: Nuevos Retos y Perspectivas NADPH Oxidase System: New Challenges and Perspectives. Iatreia 2010, 23, 362–372.

- Meuren, L.M.; Prestes, E.B.; Papa, M.P.; de Carvalho, L.R.P.; Mustafá, Y.M.; da Costa, L.S.; Da Poian, A.T.; Bozza, M.T.; Arruda, L.B. Infection of Endothelial Cells by Dengue Virus Induces ROS Production by Different Sources Affecting Virus Replication, Cellular Activation, Death and Vascular Permeability. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 810376. [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.B.; Muthuraman, K.R.; Mariappan, V.; Belur, S.S.; Lokesh, S.; Rajendiran, S. Oxidative Stress Response in the Pathogenesis of Dengue Virus Virulence, Disease Prognosis and Therapeutics: An Update. Arch Virol 2019, 164, 2895–2908. [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Talukder, M.A.H.; Gao, F. Oxidative Stress and Microvessel Barrier Dysfunction. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 504567. [CrossRef]

- Gil, L.; Martínez, G.; Tápanes, R.; Castro, O.; González, D.; Bernardo, L.; Vázquez, S.; Kourí, G.; Guzmán, M.G. Oxidative Stress in Adult Dengue Patients. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2004, 71, 652–657, doi:71/5/652 [pii].

- Klassen, P.; Biesalski, H.K.; Mazariegos, M.; Solomons, N.W.; Fürst, P. Classic Dengue Fever Affects Levels of Circulating Antioxidants. Nutrition 2004, 20, 542–547. [CrossRef]

- Ray, G.; Kumar, V.; Kapoor, a K.; Dutta, a K.; Batra, S. Status of Antioxidants and Other Biochemical Abnormalities in Children with Dengue Fever. J Trop Pediatr 1999, 45, 4–7.

- Rojas, E.M.; Díaz-quijano, F.A.; Coronel-ruiz, C.; Martínez-vega, R.A.; Rueda, E.; Villar-centeno, L.A. Correlación Entre Los Niveles de Glutatión Peroxidasa, Un Marcador de Estrés Oxidativo, y La Presentación Clínica Del Dengue. Revista Médica Chile 2007, 135, 743–750.

- Hartoyo, E.; Thalib, I.; Sari, C.M.P.; Budianto, W.Y.; Suhartono, E. A Different Approach to Assess Oxidative Stress in Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever Patients Through The Calculation of Oxidative Stress Index. J Trop Life Sci 2017, 7, 237–242. [CrossRef]

- Padilla, J.C.; Rojas, D.P.; Sáenz-Gómez, R. Dengue En Colombia. Epidemiologia de La Reemergencia a La Hiperendemia; Primera ed.; 2012; ISBN 978-958-46-00661-7.

- Villar-Centeno, L.A.; Diaz-Quijano, F.A.; Martinez-Vega, R.A. Biochemical Alterations as Markers of Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008, 78, 370–374, doi:78/3/370 [pii].

- Lanciotti, R.S.; Calisher, C.H.; Gubler, D.J.; Chang, G.J.; Vorndam, A. V. Rapid Detection and Typing of Dengue Viruses from Clinical Samples by Using Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction. J Clin Microbiol 1992, 30, 545–551. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control. Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases 2009, 147, doi:WHO/HTM/NTD/DEN/2009.1.

- Goldstein, B.; Giroir, B.; Randolph, A. International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference: Definitions for Sepsis and Organ Dysfunction in Pediatrics*. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2005, 6, 2–8. [CrossRef]

- Paglia, D.E.; Valentine, W.N. Studies on the Quantitative and Qualitative Characterization of Erythrocyte Glutathione Peroxidase. J Lab Clin Med 1967, 70, 158–169.

- Sun, Y.; Oberley, L.W.; Li, Y. A Simple Method for Clinical Assay of Superoxide Dismutase. Clin Chem 1988, 34, 497–500.

- Miller, N.J.; Rice-Evans, C.; Davies, M.J.; Gopinathan, V.; Milner, A. A Novel Method for Measuring Antioxidant Capacity and Its Application to Monitoring the Antioxidant Status in Premature Neonates. Clin Sci (Lond) 1993, 84, 407–412.

- Cherupanakkal, C.; Ramachadrappa, V.; Kadhiravan, T.; Parameswaran, N.; Parija, S.C.; Pillai, A.B.; Rajendiran, S. A Study on Gene Expression Profile of Endogenous Antioxidant Enzymes: CAT, MnSOD and GPx in Dengue Patients. Indian J Clin Biochem 2017, 32, 437–445. [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.; Pinzón, H.S.; Alvis-Guzman, N. A Systematic Review of Observational Studies on Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress Involvement in Dengue Pathogenesis. Colombia Médica : CM 2015, 46, 135. [CrossRef]

- Soundravally, R.; Sankar, P.; Bobby, Z.; Hoti, S.L. Oxidative Stress in Severe Dengue Viral Infection: Association of Thrombocytopenia with Lipid Peroxidation. Platelets 2008, 19, 447–454. [CrossRef]

- Soundravally, R.; Hoti, S.L.; Patil, S.A.; Cleetus, C.C.; Zachariah, B.; Kadhiravan, T.; Narayanan, P.; Kumar, B.A. Association between Proinflammatory Cytokines and Lipid Peroxidation in Patients with Severe Dengue Disease around Defervescence. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2014, 18, 68–72. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).