Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Laboratory Studies

2.3. Data Processing

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Apparent diffusion coefficient |

| aPTT | Activated partial thromboplastin time |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| bGSH | Blood glutathione (reduced) |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| CE-UV | Capillary electrophoresis – ultraviolet detection |

| CT | Computer tomography |

| Cys | Cysteine |

| CysS | Cystine |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| CβS | Cystathionine beta-synthase |

| GLT-1 | Glutamate transporter-1 |

| GPx4 | GSH peroxidase 4 |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSNO | Nitrosoglutathione |

| GSSG | Glutathione disulfide (blood) |

| Hcy | Homocysteine |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HS | Hemorrhagic stroke |

| ICH | Intracerebral hemorrhage |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| mRS | Modified Rankin Scale |

| NAC | N-acetyl-L-cysteine |

| NIHSS | National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| OS | Oxidative stress |

| rCys | Reduced cysteine |

| rGSH | Reduced glutathione (plasma) |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| RR | Relative risk ratio |

| SAH | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| T1 | First tertile |

| T3 | Third tertile |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| tGSH | Total glutathione |

| tHcy | Total homocysteine |

| TOAST | Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment |

| WBCs | White blood cells |

| xc− | Cystine/glutamate transporter |

References

- GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 795–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananth, C.V. , Brandt, J.S., Keyes, K.M., Graham, H.L., Kostis, J.B., Kostis, W.J. Epidemiology and trends in stroke mortality in the USA, 1975-2019. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 52, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaño, A. , Hanley, D.F., Hemphill, J.C. 3rd. Hemorrhagic stroke. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2021, 176, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J. , Dai, X., Yv, X., Zheng, L., Zheng, J., Kuang, B., Teng, W., Yu, W., Li, M., Cao, H., Zou, W. The role of potential oxidative biomarkers in the prognosis of intracerebral hemorrhage and the exploration antioxidants as possible preventive and treatment options. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1541230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayer, R.E. , Zhang, J.H. Oxidative stress in subarachnoid haemorrhage: significance in acute brain injury and vasospasm. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2008, 104, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D. , Cao, Z., Li, Z., Gu, H., Zhou, Q., Zhao, X., Wang, Y. Homocysteine and Clinical Outcomes in Intracerebral Hemorrhage Patients: Results from the China Stroke Center Alliance. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2022, 18, 2837–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. , Zhang, L., Nie, K., Yang, J., Lou, H., Wang, J., Huang, S., Gu, C., Yan, M., Zhan, R., Pan, J. Admission Homocysteine as a Potential Predictor for Delayed Cerebral Ischemia After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Front. Surg. 2022, 8, 813607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D. , Sun, Y., Liu, C., Xing, H., Wang, B., Qin, X., Liu, X., Li, A. Association of Glasgow Coma Scale with Total Homocysteine Levels in Patients with Hemorrhagic Stroke. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 75, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandapani, S. , Goudihalli, S., Mukherjee, K. K., Singh, H., Srinivasan, A., Danish, M., Mahalingam, S., Dhandapani, M., Gupta, S. K., Khandelwal, N., Mathuriya, S. N. Prospective study of the correlation between admission plasma homocysteine levels and neurological outcome following subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case for the reverse epidemiology paradox? Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 2015, 157, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C. The role of glutathione peroxidase 4 in neuronal ferroptosis and its therapeutic potential in ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Brain Res. Bull. 2024, 217, 111065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.V. , Alexandrin, V.V., Paltsyn, A.A., Nikiforova, K A., Virus, E.D., Luzyanin, B.P., Maksimova, M.Y., Piradov, M.A., Kubatiev, A.A. Plasma low-molecular-weight thiol/disulphide homeostasis as an early indicator of global and focal cerebral ischaemia. Redox Rep. 2017, 22, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, Y. , Aratake, T., Shimizu, T., Shimizu, S., Saito, M. Protective Role of Glutathione in the Hippocampus after Brain Ischemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H. , Zhang, D.M., Chen, H.L., Lin, Y.X., Hang, C.H., Yin, H.X., Shi, J.X. N-acetylcysteine suppresses oxidative stress in experimental rats with subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 16, 684–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabuki, Y. , Fukunaga, K. Oral administration of glutathione improves memory deficits following transient brain ischemia by reducing brain oxidative stress. Neuroscience 2013, 250, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.C. Glutathione synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013, 1830, 3143–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C. , Håkansson, N., Wolk, A. Dietary cysteine and other amino acids and stroke incidence in women. Stroke 2015, 46, 922–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dringen, R. , Arend, C. Glutathione Metabolism of the Brain-The Role of Astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimova, M.Y.; Ivanov, A.V.; Virus, E.D.; Nikiforova, K.A.; Ochtova, F.R.; Suanova, E.T.; Kruglova, M.P.; Piradov, M.A.; Kubatiev, A.A. Impact of glutathione on acute ischemic stroke severity and outcome: Possible role of aminothiols redox status. Redox Rep. Commun. Free Radic. Res. 2021, 26, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, A.V. , Alexandrin, V.V., Paltsyn, A.A., Virus, E.D., Nikiforova, K.A., Bulgakova, P.O., Sviridkina, N.B., Svetlana Alexandrovna Apollonova, Kubatiev, A.A. Metoprolol and Nebivolol Prevent the Decline of the Redox Status of Low-Molecular-Weight Aminothiols in Blood Plasma of Rats During Acute Cerebral Ischemia. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2018, 72, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brott, T.; Adams, H.P.; Olinger, C.P.; Marler, J.R.; Barsan, W.G.; Biller, J.; Spilker, J.; Holleran, R.; Eberle, R.; & Hertzberg, V. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: A clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989, 20, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulter, G.; Steen, C.; De Keyser, J. Use of the Barthel index and modified Rankin scale in acute stroke trials. Stroke 1999, 30, 1538–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimova, M.Y. , Ivanov, A.V., Virus, E.D., Alexandrin, V.V., Nikiforova, K.A., Bulgakova, P.O., Ochtova, F.R., Suanova, E.T., Piradov, M.A., Kubatiev, A.A. Disturbance of thiol/disulfide aminothiols homeostasis in patients with acute ischemic stroke stroke: Preliminary findings. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2019, 183, 105393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.V.; Popov, M.A.; Aleksandrin, V.; Pudova, P.A.; Galdobina, M.P.; Metelkin, A.A.; Kruglova, M.P.; Maslennikov, R.A.; Silina, E.V.; Stupin, V.A.; et al. Simultaneous determination of cysteine and other free aminothiols in blood plasma using capillary electrophoresis with pH-mediated stacking. Electrophoresis 2024, 45, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, A.V. , Popov, M.A., Aleksandrin, V.V., Kozhevnikova, L.M., Moskovtsev, A.A., Kruglova, M.P., Vladimirovna, S.E., Aleksandrovich, S.V., Kubatiev, A.A. Determination of glutathione in blood via capillary electrophoresis with pH-mediated stacking. Electrophoresis 2022, 43, 1859–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.V.; Popov, M.A.; Metelkin, A.A.; Aleksandrin, V.V.; Agafonov, E.G.; Kruglova, M.P.; Silina, E.V.; Stupin, V.A.; Maslennikov, R.A.; Kubatiev, A.A. Influence of Coronary Artery Bypass Grafts on Blood Aminothiols in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Metabolites 2023, 13, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human IL-6. Platinum ELISA. In Product Information &Manual; BenderMedSystems GmbH Campus Vienna Biocenter 2: Vienna, Austria. 2012. Available online: http://www.ulab360.com/files/prod/manuals/201305/15/376695001.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Kaneva, A.M. , Potolitsyna, N.N., Bojko, E.R. Range of values for lipid accumulation product (LAP) in healthy residents of the European north of Russia. Obesity and metabolism 2020, 17, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A. , Lindgren, A., Hultberg, B. Effect of thiol oxidation and thiol export from erythrocytes on determination of redox status of homocysteine and other thiols in plasma from healthy subjects and patients with cerebral infarction. Clin. Chem. 1995, 41, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.H. , Maggiore, J.A., Reynolds, R.D., Helgason, C.M. Novel approach for the determination of the redox status of homocysteine and other aminothiols in plasma from healthy subjects and patients with ischemic stroke. Clin. Chem. 2001, 47, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carru, C. , Deiana, L., Sotgia, S., Pes, G. M., Zinellu, A.Plasma thiols redox status by laser-induced fluorescence capillary electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 2004, 25, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katrusiak, A.E. , Paterson, P.G., Kamencic, H., Shoker, A., Lyon, A.W. Pre-column derivatization high-performance liquid chromatographic method for determination of cysteine, cysteinyl-glycine, homocysteine and glutathione in plasma and cell extracts. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 2001, 758, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H. , Kiyohara, Y., Kato, I., Kitazono, T., Tanizaki, Y., Kubo, M., Ueno, H., Ibayashi, S., Fujishima, M., Iida, M. Relationship between plasma glutathione levels and cardiovascular disease in a defined population: the Hisayama study. Stroke 2004, 35, 2072–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyol, M.E. , Demir, C., Görken, G. Investigation of Oxidative Stress Level and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Operated and Nonoperated Patients with Spontaneous Intracerebral Hematoma. J. Neurol. Surg. A Cent. Eur. Neurosurg. 2024, 85, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.L. , Klaidman, L.K., Adams, J.D. The effects of oxidative stress on in vivo brain GSH turnover in young and mature mice. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 1997, 30, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guégan, C. , Ceballos-Picot, I., Nicole, A., Kato, H., Onténiente, B., Sola, B. Recruitment of several neuroprotective pathways after permanent focal ischemia in mice. Exp. Neurol. 1998, 154, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarocka-Karpowicz, I. , Syta-Krzyżanowska, A., Kochanowicz, J., Mariak, Z.D. Clinical Prognosis for SAH Consistent with Redox Imbalance and Lipid Peroxidation. Molecules 2020, 25, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, C. , Winnefeld, K., Streck, S., Roskos, M., Haberl, R.L. Antioxidant status in acute stroke patients and patients at stroke risk. Eur. Neurol. 2004, 51, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaetani, P. , Pasqualin, A., Rodriguez y Baena, R., Borasio, E., Marzatico, F. Oxidative stress in the human brain after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. 1998, 89, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygul, R. , Demircan, B., Erdem, F., Ulvi, H., Yildirim, A., Demirbas, F. Plasma values of oxidants and antioxidants in acute brain hemorrhage: role of free radicals in the development of brain injury. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2005, 108, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolescu, B. N. , Berteanu, M., Oprea, E., Chiriac, N., Dumitru, L., Vladoiu, S., Popa, O., Ianas, O. Dynamic of oxidative and nitrosative stress markers during the convalescent period of stroke patients undergoing rehabilitation. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2011, 48, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkul, A. , Akyol, A., Yenisey, C., Arpaci, E., Kiylioglu, N., & Tataroglu, C. Oxidative stress in acute ischemic stroke. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 14, 1062–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frassetto, S.S. , Schetinger, M.R., Webber, A., Sarkis, J.J., Netto, C.A. Ischemic preconditioning reduces peripheral oxidative damage associated with brain ischemia in rats. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1999, 32, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizui, T. , Kinouchi, H., Chan, P.H. Depletion of brain glutathione by buthionine sulfoximine enhances cerebral ischemic injury in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1992, 262, H313–H317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilo, F.J. , Bilger, S., Halfens, R.J., Schols, J.M., Hahn, S. Involvement of the end user: exploration of older people's needs and preferences for a wearable fall detection device - a qualitative descriptive study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016, 11, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, F. , Hager, C., Taufik, H., Wiesmann, M., Hasan, D., Reich, A., Pinho, J., Nikoubashman, O. Seeing the good in the bad: actual clinical outcome of thrombectomy stroke patients with formally unfavorable outcome. Neuroradiology 2022, 64, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.D. , Yoon, S.S., Chang, H. Association of hospital arrival time with modified rankin scale at discharge in patients with acute cerebral infarction. Eur. Neurol. 2010, 64, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.P. , Wu, N., Chen, X.J., Chen, F.L., Xu, H.S., Bao, G.S. NIHSS-the Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score mismatch in guiding thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 1515–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastani, A. , Rajabi, S., Daliran, A., Saadat, H., Karimi-Busheri, F. Oxidant and antioxidant status in coronary artery disease. Biomed Rep. 2018, 9, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musthafa, Q.A. , Abdul Shukor, M.F., Ismail, N.A.S., Mohd Ghazi, A., Mohd Ali, R., M Nor, I.F., Dimon, M.Z., Wan Ngah, W.Z. Oxidative status and reduced glutathione levels in premature coronary artery disease and coronary artery disease. Free Radic. Res. 2017, 51, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadhan, S. , Venkatachalam R., Perumal S.M., Ayyamkulamkara S.S. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress Parameters and Antioxidant Status in Coronary Artery Disease Patients. Arch. Razi. Inst. 2022, 77, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.S.; Ghasemzadeh, N.; Eapen, D.J.; Sher, S.; Arshad, S.; Ko, Y.A.; Veledar, E.; Samady, H.; Zafari, A.M.; Sperling, L.; et al. Novel Biomarker of Oxidative Stress Is Associated With Risk of Death in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation 2016, 133, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, P.G. Lyon, A.W., Kamencic, H., Andersen, L.B., Juurlink, B.H. Sulfur amino acid deficiency depresses brain glutathione concentration. Nutr. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 213–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janáky, R.; Varga, V.; Hermann, A.; Saransaari, P.; Oja, S.S. Mechanisms of L-cysteine neurotoxicity. Neurochem. Res. 2000, 25, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.E.; Coody, T.K.; Jeong, M.Y.; Berg, J.A.; Winge, D.R.; Hughes, A.L. Cysteine Toxicity Drives Age-Related Mitochondrial Decline by Altering Iron Homeostasis. Cell 2020, 180, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagov, A.; Postnov, A.; Sukhorukov, V.; Popov, M.; Uzokov, J.; Orekhov, A. Significance of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Biosci. Landmark Ed. 2024, 29, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Wang, L.; Hu, Q.; Liu, S.; Bai, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, T.; Bo, S.; Gao, X.; Wu, S.; et al. Neuroprotective Roles of l-Cysteine in Attenuating Early Brain Injury and Improving Synaptic Density via the CBS/H2S Pathway Following Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y. , Duan, X., Li, H., Dang, B., Yin, J., Wang, Y., Gao, A., Yu, Z., Chen, G. Hydrogen Sulfide Ameliorates Early Brain Injury Following Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 3646–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.Z. , Wu, C.W., Shen, S.L., Zhang, J.Y., Li, L. Neuroprotective Effects of Early Brain Injury after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats by Calcium Channel Mediating Hydrogen Sulfide. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 41, 1707–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S. , Zhu, P., Yu, X., Chen, J., Li, J., Yan, F., Wang, L., Yu, J., Chen, G. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates brain edema in early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats: Possible involvement of MMP-9 induced blood-brain barrier disruption and AQP4 expression. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 621, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.J.; Chai, C.; Lim, T.W.; Yamamoto, M.; Lo, E.H.; Lai, M.K.; Wong, P.T. Cystathionine β-synthase inhibition is a potential therapeutic approach to treatment of ischemic injury. ASN Neuro. 2015, 7, 1759091415578711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechpammer, M. , Tran, Y.P., Wintermark, P., Martínez-Cerdeño, V., Krishnan, V. V., Ahmed, W., Berman, R. F., Jensen, F.E., Nudler, E., Zagzag, D. Upregulation of cystathionine β-synthase and p70S6K/S6 in neonatal hypoxic ischemic brain injury. Brain Pathol. 2017, 27, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omorou, M.; Liu, N.; Huang, Y.; Al-Ward, H.; Gao, M.; Mu, C.; Zhang, L.; Hui, X. Cystathionine beta-Synthase in hypoxia and ischemia/reperfusion: A current overview. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 718, 109149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K. , Chen, C.P., Halliwell, B., Moore, P.K., Wong, P.T. Hydrogen sulfide is a mediator of cerebral ischemic damage. Stroke 2006, 37, 889–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.; Qu, K.; Chimon, G.N.; Seah, A.B.; Chang, H.M.; Wong, M.C.; Ng, Y.K.; Rumpel, H.; Halliwell, B.; Chen, C.P. High plasma cyst(e)ine level may indicate poor clinical outcome in patients with acute stroke: Possible involvement of hydrogen sulfide. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2006, 65, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCune, C.D.; Chan, S.J.; Beio, M.L.; Shen, W.; Chung, W.J.; Szczesniak, L.M.; Chai, C.; Koh, S.Q.; Wong, P.T.; Berkowitz, D.B. “Zipped Synthesis” by Cross-Metathesis Provides a Cystathionine β-Synthase Inhibitor that Attenuates Cellular H2S Levels and Reduces Neuronal Infarction in a Rat Ischemic Stroke Model. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheid, S. , Goeller, M., Baar, W., Wollborn, J., Buerkle, H., Schlunck, G., Lagrèze, W., Goebel, U., Ulbrich, F. Hydrogen Sulfide Reduces Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury in Neuronal Cells in a Dose- and Time-Dependent Manner. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M. , Liu, D., Qiu, J., Yuan, H., Hu, Q., Xue, H., Li, T., Ma, W., Zhang, Q., Li, G., Wang, Z. Evaluation of H2S-producing enzymes in cerebrospinal fluid and its relationship with interleukin-6 and neurologic deficits in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 123, 109722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrix, P. , Foreman, P.M., Harrigan, M.R., Fisher, W S., Vyas, N.A., Lipsky, R.H., Lin, M., Walters, B.C., Tubbs, R S., Shoja, M.M., Pittet, J.F., Mathru, M., Griessenauer, C.J. Association of cystathionine beta-synthase polymorphisms and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 128, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grobelny, B.T. , Ducruet, A.F., DeRosa, P.A., Kotchetkov, I.S., Zacharia, B.E., Hickman, Z.L., Fernandez, L., Narula, R., Claassen, J., Lee, K., Badjatia, N., Mayer, S A., Connolly, E.S., Jr. Gain-of-function polymorphisms of cystathionine β-synthase and delayed cerebral ischemia following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 115, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, K.; Nakaki, T. Impaired glutathione synthesis in neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 21021–21044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdo, J.; Dargusch, R.; Schubert, D. Distribution of the cystine/glutamate antiporter system xc− in the brain, kidney, and duodenum. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2006, 54, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massie, A.; Boillée, S.; Hewett, S.; Knackstedt, L.; Lewerenz, J. Main path and byways: Non-vesicular glutamate release by system xc− as an important modifier of glutamatergic neurotransmission. J. Neurochem. 2015, 135, 1062–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Hewett, S.J. The Cystine/Glutamate Antiporter, System xc−, Contributes to Cortical Infarction After Moderate but Not Severe Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Mice. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 821036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.J.; Jun, H.O.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.H. Astrocytic cystine/glutamate antiporter is a key regulator of erythropoietin expression in the ischemic retina. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 6045–6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Cui, Y.; Dong, S.; Kong, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wan, Q.; Wang, Q. Treadmill Training Reduces Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Inhibiting Ferroptosis through Activation of SLC7A11/GPX4. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 8693664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heit, B.S.; Chu, A.; McRay, A.; Richmond, J.E.; Heckman, C.J.; Larson, J. Interference with glutamate antiporter system xc− enables post-hypoxic long-term potentiation in hippocampus. Exp. Physiol. 2024, 109, 1572–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.H.; Lin, Y.J.; Chen, W.L.; Huang, Y.C.; Chang, C.W.; Cheng, F.C.; Liu, R.S.; Shyu, W.C. HIF-1α triggers long-lasting glutamate excitotoxicity via system xc− in cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion. J. Pathol. 2017, 241, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, F.N.; Pérez-Samartín, A.; Martin, A.; Gona, K.B.; Llop, J.; Szczupak, B.; Chara, J.C.; Matute, C.; Domercq, M. Extrasynaptic glutamate release through cystine/glutamate antiporter contributes to ischemic damage. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 3645–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G. , Berk, M., Campochiaro, P.A., Jaeschke, H., Marenzi, G., Richeldi, L., Wen, F Q., Nicoletti, F., Calverley, P.M.A. The Multifaceted Therapeutic Role of N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) in Disorders Characterized by Oxidative Stress. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2021, 19, 1202–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabetghadam, M. , Mazdeh, M., Abolfathi, P., Mohammadi, Y., Mehrpooya, M. Evidence for a Beneficial Effect of Oral N-acetylcysteine on Functional Outcomes and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 1265–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppagounder, S.S. , Alin, L., Chen, Y., Brand, D., Bourassa, M.W., Dietrich, K., Wilkinson, C.M., Nadeau, C.A., Kumar, A., Perry, S., Pinto, J.T., Darley-Usmar, V., Sanchez, S., Milne, G.L., Pratico, D., Holman, T.R., Carmichael, S.T., Coppola, G., Colbourne, F., Ratan, R.R. N-acetylcysteine targets 5 lipoxygenase-derived, toxic lipids and can synergize with prostaglandin E2 to inhibit ferroptosis and improve outcomes following hemorrhagic stroke in mice. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 84, 854–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X. , Zhou, Z., Xiang, W., Jiang, Y., Tian, N., Tang, X., Chen, S., Wen, J., Chen, M., Liu, K., Li, Q., Liao, R. Glutathione alleviates acute intracerebral hemorrhage injury via reversing mitochondrial dysfunction. Brain Res. 2020, 1727, 146514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.Q. , Mou, R.T., Feng, D.X., Wang, Z., Chen, G. The role of nitric oxide in stroke. Med. Gas. Res. 2017, 7, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. , Sakakima, H., Dhammu, T. S., Shunmugavel, A., Im, Y. B., Gilg, A. G., Singh, A. K., Singh, I. S-nitrosoglutathione reduces oxidative injury and promotes mechanisms of neurorepair following traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. , Dhammu, T.S., Sakakima, H., Shunmugavel, A., Gilg, A.G., Singh, A.K., Singh, I. The inhibitory effect of S-nitrosoglutathione on blood-brain barrier disruption and peroxynitrite formation in a rat model of experimental stroke. J. Neurochem. 2012, 123, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan M, Dhammu TS, Matsuda F, et al. Blocking a vicious cycle nNOS/peroxynitrite/AMPK by S-nitrosoglutathione: implication for stroke therapy. BMC Neurosci. 2015, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.K. , Ahmed, F., Alkhatabi, H., Hoda, M.N., Al-Qahtani, M. Nebulization of Low-Dose S-Nitrosoglutathione in Diabetic Stroke Enhances Benefits of Reperfusion and Prevents Post-Thrombolysis Hemorrhage. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehba, F.A. , Ding, W.H., Chereshnev, I., Bederson, J.B. Effects of S-nitrosoglutathione on acute vasoconstriction and glutamate release after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 1999, 30, 1955–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S. , Zheng, H., Yu, W., Ramakrishnan, V., Shah, S., Gonzalez, L.F., Singh, I., Graffagnino, C., Feng, W. Investigation of S-Nitrosoglutathione in stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of literature in pre-clinical and clinical research. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 328, 113262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramanti, E. , Angeli, V., Mester, Z., Pompella, A., Paolicchi, A., D'Ulivo, A. Determination of S-nitrosoglutathione in plasma: comparison of two methods. Talanta 2010, 81, 1295–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Whole cohort | ICH | SAH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 64 | 12 | 52 |

| Age, years | 55 (49; 58) | 50.5 (47; 55) | 55.5 (49.3; 58) |

| Man (%) | 51 (79.7) | 10 (83.3) | 41 (78.8) |

| NIHSS | 8.5 (7.0; 15.5) | 9.0 (6.25; 16) | 8.0 (7.0; 13.3) |

| mRS | 3 (2;3) | 3 (2; 3.75) | 3 (2; 3) |

| Risk factors | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 36 (56.3) | 6 (50) | 30 (57.7) |

| CAD, n (%) | 34 (53.1) | 9 (75) | 25 (48.1) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 36 (56.3) | 6 (50) | 30 (57.7) |

| High atherogenic coefficient, n (%) | 35 (54.7) | 5 (41.7) | 29 (55.8) |

| Current cigarette smoking, n (%) | 57 (89.1) | 9 (75) | 48 (92.3) |

| Alcohol drinker, n (%) | 34 (53.1) | 8 (66.7) | 26 (50) |

| Hyperhomocysteinemia (Hcy > 15 μM), % | 20.3 | 25 | 19.2 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Total cholesterol, mM | 3.5 (1.5; 3.9) | 3.5 (1.7; 3.6) | 3.5 (1.5; 4.0) |

| TG, mM | 2.1 (1.7; 2.7) | 1.95 (1.1; 2.68) | 2.1 (1.85; 2.7) |

| HDL-C, mM | 1.2 (1.1; 1.4) | 1.35 (1.2; 1.7) | 1.2 (0.98; 1.3) |

| LDL-C, mM | 2.4 (2.1; 3.4) | 2.05 (1.9; 2.4) | 2.4 (2.2; 3.6) |

| Glucose, mM | 4.8 (4.7; 5.1) | 4.8 (4.8; 5.75) | 4.8 (4.7; 5.1) |

| aPTT, s | 33 (27; 35) | 32 (27; 36.5) | 33 (27; 35) |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 3.9 (3.7; 3.9) | 3.9 (3.83; 3.9) | 3.8 (3.7; 3.9) |

| WBC,109/L | 7 (6; 8) | 7 (7; 9.5) | 7 (6; 8) |

| PLT,109/L | 278 (234; 311) | 278 (278; 300) | 278 (234; 311) |

| Ferritin, μg/L | 75 (45; 80) | 75 (39; 76.5) | 75 (45; 82.5) |

| Hcy, μM | 9.8 (7.5; 14.6) | 8.7 (6.2; 15.0) | 10.1 (7.8; 14.5) |

| Free plasma thiols | |||

| rCys, μM | 15.1 (7.4; 18.7) | 13.8 (8.1; 17.4) | 15.6 (6.3; 19.0) |

| CysS, μM | 51.1 (36.5; 63.1) | 57.3 (37.2; 66.8) | 50.2 (35.7; 62.1) |

| rGSH, μM | 1.04 (0.33; 2.00) | 0.79 (0.34; 1.96) | 1.09 (0.33; 2.04) |

| Blood GSH | |||

| bGSH, μM | 827 (689; 994) | 812 (739; 984) | 846 (678; 994) |

| GSSG, μM | 3.35 (2.12; 4.38) | 2.57 (2.18; 4.18) | 3.41 (2.03; 4.43) |

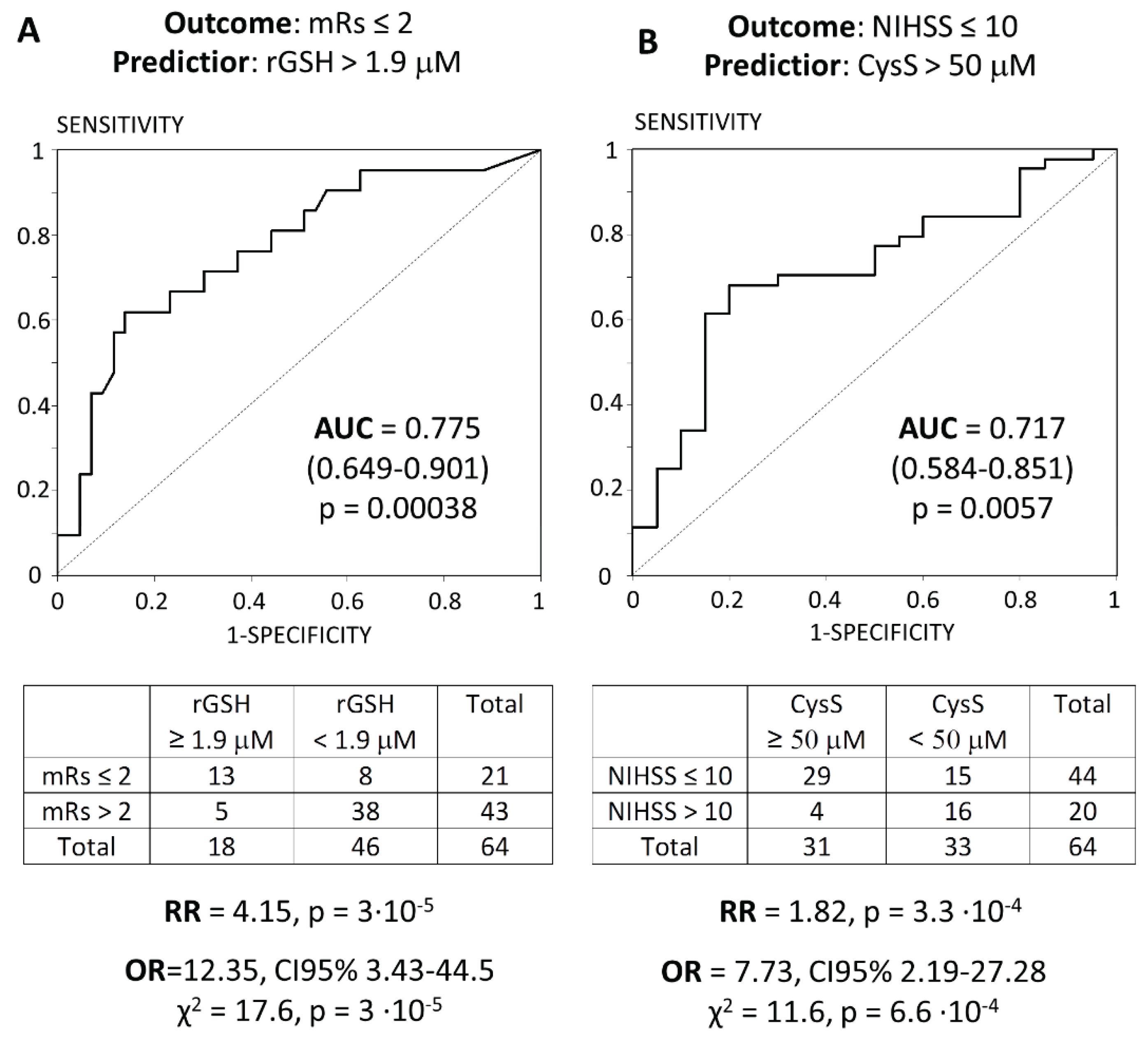

| Indicator | mRS ≤ 2 (N=21) | mRS > 2 (N=43) | pMann-U |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 55 (49; 58) | 55 (49; 57) | > .05 |

| Man (%) | 17 (81) | 34 (79.1) | > .05 |

| rGSH, μM | 2.06 (0.93; 3.24) | 0.61 (0.16; 1.34) | 0.0026 |

| GSSG, μM | 2.78 (2.24; 4.00) | 3.35 (1.79; 4.37) | > .05 |

| bGSH, μM | 804 (690; 936) | 839 (689; 1003) | > .05 |

| CysS, μM | 56.8 (45.7; 64.6) | 44.3 (32.5; 59.4) | > .05 |

| rCys, μM | 15.4 (8.6; 21.9) | 14.7 (7.4; 18.1) | > .05 |

| Indicator | NIHSS ≤ 10 (N=44) | NIHSS > 10 (N=20) | pMann-U |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 55 (49; 57) | 55 (49.5; 58) | > .05 |

| Man (%) | 36 (81.8) | 15 (75) | > .05 |

| CysS, μM | 54.7 (41.3; 64.6) | 43.0 (32.6; 49.4) | .011 |

| rGSH, μM | 1.12 (0.32; 2.08) | 0.59 (0.33; 1.83) | > .05 |

| GSSG, μM | 3.36 (2.06; 4.26) | 3.28 (1.98; 4.53) | > .05 |

| bGSH, μM | 839 (701; 994) | 817 (611; 877) | > .05 |

| rCys, μM | 16.5 (7.8; 19.1) | 10.8 (5.9; 17.5) | > .05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).