Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

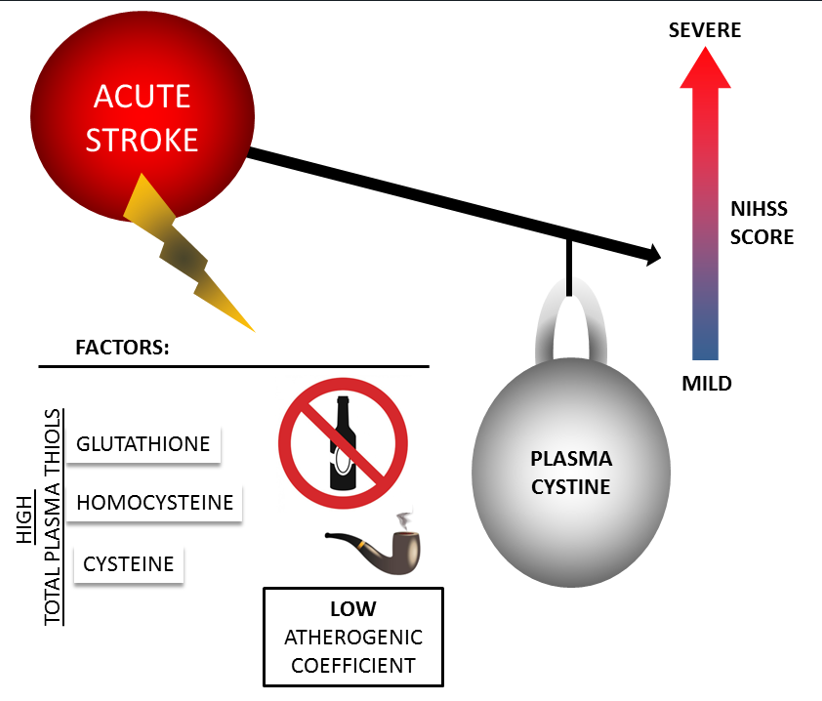

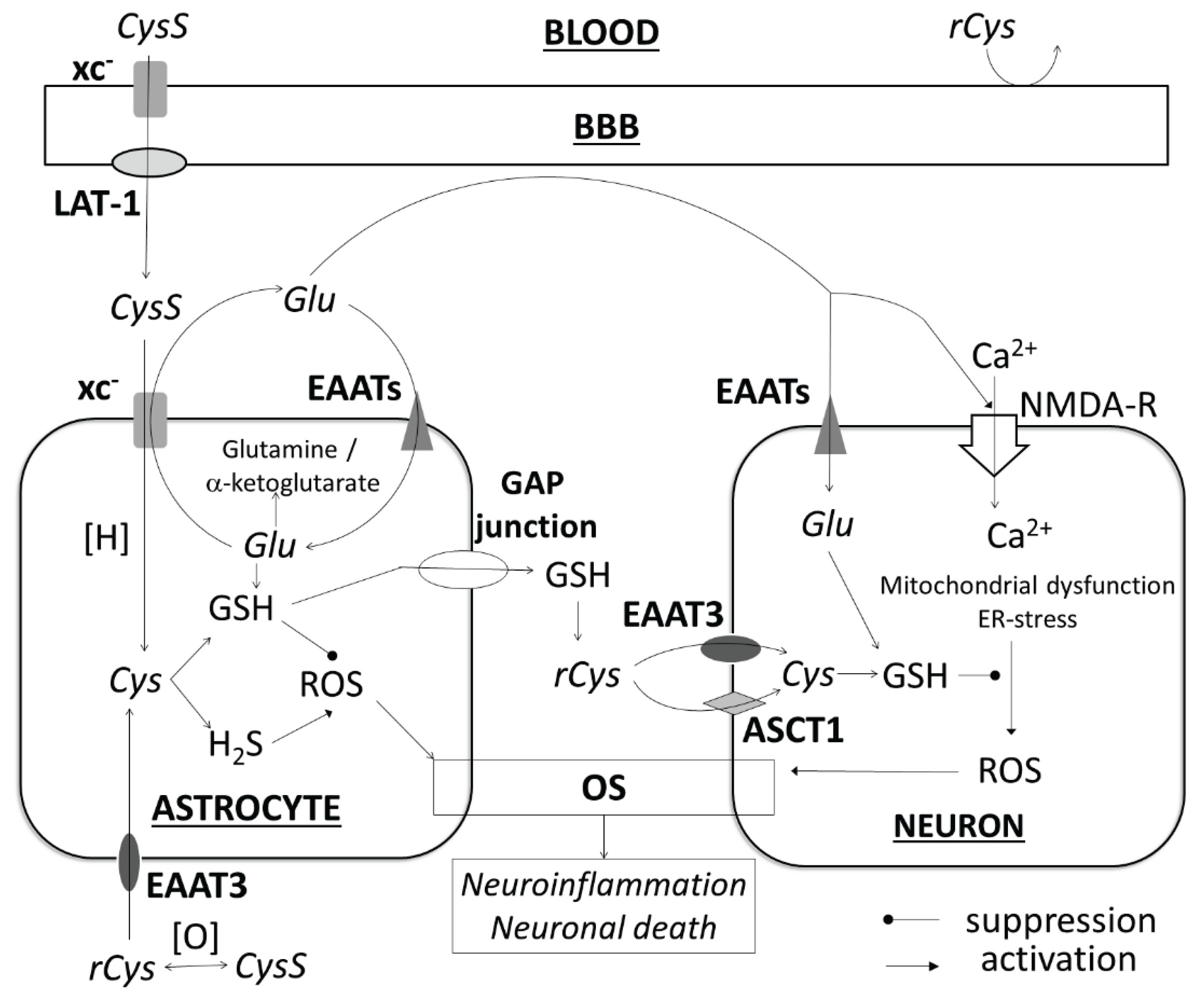

Background/Objectives: The amino acid cysteine (Cys) plays an important role in the neuronal injury process in stroke. Cys is present in blood plasma in various forms. The relationship between Cys and its forms and the severity of acute stroke has not been sufficiently studied. We investigated the total Cys and the levels of two of its forms (reduced Cys and its disulfide (cystine, CysS)) in blood plasma and the influence on stroke severity in patients at admission. Methods: A total of 210 patients (39-59 years old) with ischemic stroke and intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage were examined. The content of the different forms of Cys was determined in the first 10–72 h. Stroke severity was estimated using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and the modified Rankin Scale (mRs). Results: CysS levels < 54 μM were associated with severe (NIHSS>13) neurological deficit (ischemic stroke: RR=5.58, p=0.0021; hemorrhagic stroke: RR=3.56, p=0.0003). Smoking and high levels of total Cys and other thiols (glutathione and homocysteine) appear to be factors determining this relationship. Conclusions: Low CysS levels may act as a potential biomarker of acute stroke severity.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

- Men and women aged up to 60 years inclusive;

- The time from the onset of stroke symptoms to the inclusion in the study was not more than 72 hours;

- Patients who suffered their first stroke, as verified by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/ computer tomography (CT) scan of the brain;

- Signing and dating an informed consent form by the patient or a disinterested witness (if the patient was unable to sign due to physical limitations).

- The criteria for non-inclusion of patients from the study were as follows:

- The time from the onset of acute stroke symptoms to the inclusion in the study was more than 72 hours;

- Patients with contraindications to CT/MRI (installed pacemaker/neurostimulator/pacemaker; inner ear prosthesis, ferromagnetic or electronic middle ear implants, hemostatic clips, prosthetic heart valves and any other metal-containing structures, ferromagnetic fragments; insulin pumps) or inability to undergo the CT/MRI procedure (pronounced claustrophobia, etc.);

- The presence of any neuroimaging (CT/MRI) signs of a brain tumor, arteriovenous malformation, brain abscess, cerebral vascular aneurysm, or edema of the infarct zone, leading to the dislocation of brain structures (malignant course of cerebral infarction);

- Repeated ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, or a history of unspecified stroke;

- Traumatic brain injury within the past 6 months before screening;

- Patients with a history of surgical intervention on the brain or spinal cord;

- Patients with a history of epilepsy or severe cognitive impairment.

- The criteria for exclusion of patients from the study were as follows:

- Positive blood tests for HIV, syphilis, or hepatitis B and/or C detected at the start of the study;

- The appearance of any diseases or conditions during the study that worsened the patient's prognosis, and made it impossible for the patient to continue participating in the clinical trial;

- Violation of the study protocol such as incorrect inclusion of patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria, use of prohibited therapy, or other significant protocol violations according to the investigator’s opinion;

- Patient's refusal to continue participating in the study.

2.2. Laboratory Studies

2.3. Data Processing

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Apparent Diffusion Coefficient |

| aPTT | activated partial thromboplastin time |

| ASCT1 | Neutral amino acid transporter A |

| AT | atherothrombotic stroke |

| BBB | blood-brain barrier |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| CE | cardioembolic stroke |

| CG | cysteinylglycine |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CT | computer tomography |

| Cys | cysteine |

| CysS | cystine |

| CβS | cystathionine beta-synthase |

| DM2 | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| DWI | diffusion-weighted imaging |

| EAAT | excitatory amino acid transporter |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| EAAC1 | Excitatory Amino Acid Carrier 1 |

| GLT-1 | Glutamate transporter-1 |

| Glu | glutamate |

| GSH | glutathione |

| Hcy | homocysteine |

| HDL-C | high-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HHcy | hyperhomocysteinemia |

| HS | hemorrhagic stroke |

| ICH | intracerebral hemorrhage |

| IL-1β | interleukin 1β |

| IL-6 | interleukin 6 |

| IS | ischemic stroke |

| Lac | lacunar stroke |

| LAT-1 | Large Neutral Amino Acid Transporter 1 |

| LDL-C | low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LMWTs | low-molecular weight aminothiols |

| MCAO | middle cerebral artery occlusion |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| mRs | modified Rankin Scale |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| NIHSS | National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| OGD | oxygen and glucose deprivation |

| OR | odds ratio |

| OS | oxidative stress |

| PLT | platelets |

| rCys | reduced cysteine |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RR | relative risk ratio |

| SAH | subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| T1 | first tertile |

| T3 | third tertile |

| tCG | total cysteinylglycine |

| tCys | total cysteine |

| TG | triglycerides |

| tGSH | total glutathione |

| tHcy | total homocysteine |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TOAST | Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment |

| WBC | white blood cells |

| xc- | cystine/glutamate transporter |

References

- GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20(10), 795-820. [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A., Al-Khamis, F.A., Al-Bakr, A.I., Alsulaiman, A.A., Msmar, A.H. Risk factors and subtypes of acute ischemic stroke. A study at King Fahd Hospital of the University. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2016, 21(3), 246-251. [CrossRef]

- Salaudeen, M.A., Bello, N., Danraka, R.N., Ammani, M.L. Understanding the Pathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke: The Basis of Current Therapies and Opportunity for New Ones. Biomolecules 2024, 14(3), 305. [CrossRef]

- Vinknes, K.J., Refsum, H., Turner, C., Khaw, K.T., Wareham, N.J., Forouhi, N.G., Imamura, F. Plasma Sulfur Amino Acids and Risk of Cerebrovascular Diseases: A Nested Case-Control Study in the EPIC-Norfolk Cohort. Stroke 2021, 52(1), 172-180. [CrossRef]

- Holmen, M., Hvas, A.M., Arendt, J.F.H. Hyperhomocysteinemia and Ischemic Stroke: A Potential Dose-Response Association-A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. TH Open 2021, 5(3), e420-e437. [CrossRef]

- Lehotsky, J., Kovalska, M., Baranovicova, E., Hnilicova, P., Kalenska, D., Kaplan, P. Ischemic Brain Injury in Hyperhomocysteinemia. In: Cerebral Ischemia [Internet]; Pluta R. Eds; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2021, Chapter 5.

- Harris, S., Rasyid, A., Kurniawan, M., Mesiano, T., Hidayat, R. Association of high blood homocysteine and risk of increased severity of ischemic stroke events. Int J Angiol. 2019, 28(1), 34–38. [CrossRef]

- Markišić, M., Pavlović, A.M., Pavlović, D.M. The Impact of homocysteine, vitamin B12, and vitamin D levels on functional outcome after firstever ischaemic stroke. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 5489057..

- Li, L., Ma, X., Zeng, L., Pandey, S., Wan, R., Shen, R., Zhang, Q. Impact of homocysteine levels on clinical outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke receiving intravenous thrombolysis therapy. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9474. [CrossRef]

- Kahl, A., Stepanova, A., Konrad, C., Anderson, C., Manfredi, G., Zhou, P., Iadecola, C., Galkin, A. Critical Role of Flavin and Glutathione in Complex I-Mediated Bioenergetic Failure in Brain Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Stroke 2018, 49(5), 1223-1231. [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, K. Glutathione in the Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22(9), 5010. [CrossRef]

- Iskusnykh, I.Y., Zakharova, A.A., Pathak, D. Glutathione in Brain Disorders and Aging. Molecules 2022, 27(1), 324. [CrossRef]

- Matuz-Mares, D., Riveros-Rosas, H., Vilchis-Landeros, M.M., Vázquez-Meza, H. Glutathione Participation in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10(8), 1220. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P. Radical-free biology of oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2008, 295(4), C849-868. [CrossRef]

- Włodek, L. Beneficial and harmful effects of thiols. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 54(3), 215-523.

- Ivanov, A.V., Alexandrin, V.V., Paltsyn, A.A., Nikiforova, K.A., Virus, E.D., Luzyanin, B.P., Maksimova, M.Y., Piradov, M.A., Kubatiev, A.A. Plasma low-molecular-weight thiol/disulphide homeostasis as an early indicator of global and focal cerebral ischaemia. Redox report: communications in free radical research 2017, 22(6), 460-466. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A., Isaksson, A., Brattström, L., Hultberg, B. Homocysteine and other thiols determined in plasma by HPLC and thiol-specific postcolumn derivatization. Clin. Chem. 1993, 39(8), 1590-1597..

- Williams, R.H., Maggiore, J.A., Reynolds, R.D., Helgason, C.M. Novel approach for the determination of the redox status of homocysteine and other aminothiols in plasma from healthy subjects and patients with ischemic stroke. Clin. Chem. 2001, 47(6), 1031–1039.

- Carru, C., Deiana, L., Sotgia, S., Pes, G.M., Zinellu, A. Plasma thiols redox status by laser-induced fluorescence capillary electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 2004, 25(6), 882-889. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.V., Popov, M.A., Aleksandrin, V., Pudova, P.A., Galdobina, M.P., Metelkin, A.A., Kruglova, M.P., Maslennikov, R.A., Silina, E.V., Stupin, V.A., Kubatiev, A.A. Simultaneous determination of cysteine and other free aminothiols in blood plasma using capillary electrophoresis with pH-mediated stacking. Electrophoresis 2024, 45(5-6), 411-419. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C., Håkansson, N., Wolk, A. Dietary cysteine and other amino acids and stroke incidence in women. Stroke 2015, 46(4), 922-926. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T., Qu, K., Chimon, G.N., Seah, A.B., Chang, H.M., Wong, M.C., Ng, Y.K., Rumpel, H., Halliwell, B., Chen, C.P. High plasma cyst(e)ine level may indicate poor clinical outcome in patients with acute stroke: possible involvement of hydrogen sulfide. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2006, 65(2), 109-115. [CrossRef]

- Paterson, P.G., Lyon, A.W., Kamencic, H., Andersen, L.B., Juurlink B.H. Sulfur amino acid deficiency depresses brain glutathione concentration. Nutr. Neurosci. 2001, 4(3), 213-222. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.C. Glutathione synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830(5), 3143-3153. [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.J., Chai, C., Lim, T.W., Yamamoto, M., Lo, E.H., Lai, M.K., Wong, P.T. Cystathionine β-synthase inhibition is a potential therapeutic approach to treatment of ischemic injury. ASN Neuro. 2015, 7(2), 1759091415578711. [CrossRef]

- Qu, K., Lee, S.W., Bian, J.S., Low, C.M., Wong, P.T. Hydrogen sulfide: neurochemistry and neurobiology. Neurochem. Int. 2008, 52(1-2), 155-165. [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y., Wang, Z., Chen, G. The role of hydrogen sulfide in stroke. Med. Gas. Res. 2016, 6(2), 79-84. [CrossRef]

- Janáky, R., Varga, V., Hermann, A., Saransaari, P., Oja, S.S. Mechanisms of L-cysteine neurotoxicity. Neurochem. Res. 2000, 25(9-10), 1397-1405. [CrossRef]

- Olney, J.W., Zorumski, C., Price, M.T., Labruyere, J. L-cysteine, a bicarbonate-sensitive endogenous excitotoxin. Science 1990, 248(4955), 596-599. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, A., West, C.A., Heine, M.F., Rigor, B.M. The neurotoxicity of sulfur-containing amino acids in energy-deprived rat hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 1993, 601(1-2), 317-320. [CrossRef]

- Goulart, V.A.M., Sena, M.M., Mendes, T.O., Menezes, H.C., Cardeal, Z.L., Paiva, M.J.N., Sandrim, V.C., Pinto, M.C.X., Resende, R.R. Amino Acid Biosignature in Plasma among Ischemic Stroke Subtypes. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 8480468. [CrossRef]

- Tao, S., Xiao, X., Li, X., Na, F., Na, G., Wang, S., Zhang, P., Hao, F., Zhao, P., Guo, D., Liu, X., Yang, D.Targeted metabolomics reveals serum changes of amino acids in mild to moderate ischemic stroke and stroke mimics. Front Neurol. 2023, 14, 1153193. [CrossRef]

- Elkafrawy, H., Mehanna, R., Ali, F., Barghash, A., Dessouky, I., Jernerén, F., Turner, C., Refsum, H., Elshorbagy, A. Extracellular ysteine influences human preadipocyte differentiation and correlates with fat mass in healthy adults. Amino Acids 2021, 53(10), 1623-1634. [CrossRef]

- Ottosson, F., Engström, G., Orho-Melander, M., Melander, O., Nilsson, P.M., Johansson, M. Plasma Metabolome Predicts Aortic Stiffness and Future Risk of Coronary Artery Disease and Mortality After 23 Years of Follow-Up in the General Population. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2024, 13(9), e033442. [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, Y., Ozkan, E., Simşek, B. Plasma total homocysteine and cysteine levels as cardiovascular risk factors in coronary heart disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2002, 82(3), 269-277. [CrossRef]

- Oda, M., Fujibayashi, K., Wakasa, M., Takano, S., Fujita, W., Kitayama, M., Nakanishi, H., Saito, K., Kawai, Y., Kajinami, K. Increased plasma glutamate in non-smokers with vasospastic angina pectoris is associated with plasma cystine and antioxidant capacity. Scand. Cardiovasc J. 2022, 56(1), 180-186. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.S., Ghasemzadeh, N., Eapen, D.J., Sher, S., Arshad, S., Ko, Y.A., Veledar, E., Samady, H., Zafari, A.M., Sperling, L., Vaccarino, V., Jones, D.P., Quyyumi, A.A. Novel Biomarker of Oxidative Stress Is Associated With Risk of Death in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation 2016, 133(4), 361-369. [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, S., Abramson, J.L., Jones, D.P., Rhodes, S.D., Weintraub, W.S., Hooper, W.C., Vaccarino, V., Alexander, R.W., Harrison, D.G., Quyyumi, A.A.Endothelial function and aminothiol biomarkers of oxidative stress in healthy adults. Hypertension 2008, 52(1), 80-85. [CrossRef]

- Salemi, G., Gueli, M.C., D'Amelio, M., Saia, V., Mangiapane, P., Aridon, P., Ragonese, P., Lupo, I. Blood levels of homocysteine, cysteine, glutathione, folic acid, and vitamin B12 in the acute phase of atherothrombotic stroke. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 30(4), 361-364. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.C., Guo, J.L., Xu, L., Jiang, X.H., Chang, C.H., Jiang, Y., Zhang, Y.Z. Impact of homocysteine on acute ischemic stroke severity: possible role of aminothiols redox status. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24(1), 175. [CrossRef]

- Maksimova, M.Y., Ivanov, A.V., Virus, E.D., Nikiforova, K.A., Ochtova, F.R., Suanova, E.T., Kruglova, M.P., Piradov, M.A., Kubatiev, A.A. Impact of glutathione on acute ischemic stroke severity and outcome: possible role of aminothiols redox status. Redox report : communications in free radical research, 2021, 26(1), 117–123. [CrossRef]

- Brott, T., Adams, H. P., Jr, Olinger, C. P., Marler, J. R., Barsan, W. G., Biller, J., Spilker, J., Holleran, R., Eberle, R., & Hertzberg, V. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989, 20(7), 864–870. [CrossRef]

- Sulter, G., Steen, C., De Keyser, J. Use of the Barthel index and modified Rankin scale in acute stroke trials. Stroke 1999, 30, 1538–1541.

- Kaneva, A.M., Potolitsyna, N.N., Bojko, E.R. Range of values for lipid accumulation product (LAP) in healthy residents of the European north of Russia. Obesity and metabolism 2020, 17(2), 179-186. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.V., Popov, M.A., Metelkin, A.A., Aleksandrin, V.V., Agafonov, E.G., Kruglova, M.P., Silina, E.V., Stupin, V.A., Maslennikov, R.A., Kubatiev, A.A. Influence of Coronary Artery Bypass Grafts on Blood Aminothiols in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Metabolites 2023, 13(6), 743. [CrossRef]

- Krzyżanowska, W., Pomierny, B., Filip, M., Pera, J. Glutamate transporters in brain ischemia: to modulate or not? Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2014, 35(4), 444-462. [CrossRef]

- Massie, A., Boillée, S., Hewett, S., Knackstedt, L., Lewerenz, J. Main path and byways: non-vesicular glutamate release by system xc(-) as an important modifier of glutamatergic neurotransmission. J. Neurochem. 2015, 135(6), 1062-1079. [CrossRef]

- Burdo, J., Dargusch, R., Schubert, D. Distribution of the cystine/glutamate antiporter system xc- in the brain, kidney, and duodenum. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2006, 54(5), 549-557. [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, K., Nakaki, T. Impaired glutathione synthesis in neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14(10), 21021-21044. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., Ko, D.G., Hong, D.K., Lim, M.S., Choi, B.Y., Suh, S.W. Role of Excitatory Amino Acid Carrier 1 (EAAC1) in Neuronal Death and Neurogenesis After Ischemic Stroke. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21(16), 5676. [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, C., Aoyama, K. The Role of Non-Coding RNAs in the Neuroprotective Effects of Glutathione. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22(8), 4245. [CrossRef]

- De Bundel, D., Schallier, A., Loyens, E., Fernando, R., Miyashita, H., Van Liefferinge, J., Vermoesen, K., Bannai, S., Sato, H., Michotte, Y., Smolders, I., Massie, A. Loss of system xI- does not induce oxidative stress but decreases extracellular glutamate in hippocampus and influences spatial working memory and limbic seizure susceptibility. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31(15), 5792-5803. [CrossRef]

- Sears, S.M.S., Hewett, J.A., Hewett, S.J. Decreased epileptogenesis in mice lacking the System xc- transporter occurs in association with a reduction in AMPA receptor subunit GluA1. Epilepsia Open 2019, 4(1), 133-143. [CrossRef]

- He, Y., Hewett, S.J. The Cystine/Glutamate Antiporter, System xc-, Contributes to Cortical Infarction After Moderate but Not Severe Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Mice. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 821036. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.J., Jun, H.O., Kim, J.H., Kim, J.H. Astrocytic cystine/glutamate antiporter is a key regulator of erythropoietin expression in the ischemic retina. FASEB J. 2019, 33(5), 6045-6054. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T., Cui, Y., Dong, S., Kong, X., Xu, X., Wang, Y., Wan, Q., Wang, Q. Treadmill Training Reduces Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Inhibiting Ferroptosis through Activation of SLC7A11/GPX4. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 8693664. [CrossRef]

- Heit, B.S., Chu, A., McRay, A., Richmond, J.E., Heckman, C.J., Larson, J. Interference with glutamate antiporter system xc- enables post-hypoxic long-term potentiation in hippocampus. Exp. Physiol. 2024, 109(9), 1572-1592. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.H., Lin, Y.J., Chen, W.L., Huang, Y.C., Chang, C.W., Cheng, F.C., Liu, R.S., Shyu, W.C. HIF-1α triggers long-lasting glutamate excitotoxicity via system xc- in cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion. J. Pathol. 2017, 241(3), 337-349. [CrossRef]

- Soria, F.N., Pérez-Samartín, A., Martin, A., Gona, K.B., Llop, J., Szczupak, B., Chara, J.C., Matute, C., Domercq, M. Extrasynaptic glutamate release through cystine/glutamate antiporter contributes to ischemic damage. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124(8), 3645-3655. [CrossRef]

- Fogal, B., Li, J., Lobner, D., McCullough, L.D., Hewett, S.J. System xI- activity and astrocytes are necessary for interleukin-1 beta-mediated hypoxic neuronal injury. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27(38), 10094-10105. [CrossRef]

- Krzyżanowska, W., Pomierny, B., Bystrowska, B., Pomierny-Chamioło, L., Filip, M., Budziszewska, B., Pera, J. Ceftriaxone- and N-acetylcysteine-induced brain tolerance to ischemia: Influence on glutamate levels in focal cerebral ischemia. PLoS One 2017, 12(10), e0186243. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Wallin, C., Weber, S.G., Sandberg, M. Net efflux of cysteine, glutathione and related metabolites from rat hippocampal slices during oxygen/glucose deprivation: dependence on gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Brain Res. 1999, 815(1), 81-88. [CrossRef]

- Slivka, A., Cohen, G. Brain ischemia markedly elevates levels of the neurotoxic amino acid, cysteine. Brain Res. 1993, 608(1), 33-37. [CrossRef]

- Sedlak, T.W., Paul, B.D., Parker, G.M., Hester, L.D., Snowman, A.M., Taniguchi, Y., Kamiya, A., Snyder, S.H., Sawa, A. The glutathione cycle shapes synaptic glutamate activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116(7), 2701-2706. [CrossRef]

- Montine, T.J., Picklo, M.J., Amarnath, V., Whetsell, W.O. Jr., Graham, D.G. Neurotoxicity of endogenous cysteinylcatechols. Exp. Neurol. 1997, 148(1), 26-33. [CrossRef]

- Omorou, M., Liu, N., Huang, Y., Al-Ward, H., Gao, M., Mu, C., Zhang, L., Hui, X. Cystathionine beta-Synthase in hypoxia and ischemia/reperfusion: A current overview. Arch. Biochem Biophys. 2022, 718, 109149. [CrossRef]

- Ren, C., Du, A., Li, D., Sui, J., Mayhan, W.G., Zhao, H. Dynamic change of hydrogen sulfide during global cerebral ischemia-reperfusion and its effect in rats. Brain Res. 2010, 1345, 197-205. [CrossRef]

- Lechpammer, M., Tran, Y.P., Wintermark, P., Martínez-Cerdeño, V., Krishnan, V.V., Ahmed, W., Berman, R.F., Jensen, F.E., Nudler, E., Zagzag, D. Upregulation of cystathionine β-synthase and p70S6K/S6 in neonatal hypoxic ischemic brain injury. Brain Pathol. 2017, 27(4), 449-458. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Zou, L.P., Du, J.B., Wong, V. Electro-acupuncture protects against hypoxic-ischemic brain-damaged immature rat via hydrogen sulfide as a possible mediator. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 485(1), 74-78. [CrossRef]

- Qu, K., Chen, C.P., Halliwell, B., Moore, P.K., Wong, P.T. Hydrogen sulfide is a mediator of cerebral ischemic damage. Stroke 2006, 37(3), 889-893. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Wu, X., Xu, Y., He, M., Yang, J., Li, J., Li, Y., Ao, G., Cheng, J., Jia, J. The cystathionine β-synthase/hydrogen sulfide pathway contributes to microglia-mediated neuroinflammation following cerebral ischemia. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 66, 332-346. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Leak, R.K., Shi, Y., Suenaga, J., Gao, Y., Zheng, P., Chen, J. Microglial and macrophage polarization—new prospects for brain repair. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11(1), 56-64. [CrossRef]

- Li, T., Wang, L., Hu, Q., Liu, S., Bai, X., Xie, Y., Zhang, T., Bo, S., Gao, X., Wu, S., Li, G., Wang, Z. Neuroprotective Roles of l-Cysteine in Attenuating Early Brain Injury and Improving Synaptic Density via the CBS/H2S Pathway Following Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 176. [CrossRef]

- McCune, C.D., Chan, S.J., Beio, M.L., Shen, W., Chung, W.J., Szczesniak, L.M., Chai, C., Koh, S.Q., Wong, P.T., Berkowitz, D.B. "Zipped Synthesis" by Cross-Metathesis Provides a Cystathionine β-Synthase Inhibitor that Attenuates Cellular H2S Levels and Reduces Neuronal Infarction in a Rat Ischemic Stroke Model. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2(4), 242-252. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N.S., Peng, Z.F., Chen, M.J., Moore, P.K., Whiteman, M. Hydrogen sulfide induced neuronal death occurs via glutamate receptor and is associated with calpain activation and lysosomal rupture in mouse primary cortical neurons. Neuropharmacology 2007, 53(4), 505-514. [CrossRef]

- Han, M., Liu, D., Qiu, J., Yuan, H., Hu, Q., Xue, H., Li, T., Ma, W., Zhang, Q., Li, G., Wang, Z. Evaluation of H2S-producing enzymes in cerebrospinal fluid and its relationship with interleukin-6 and neurologic deficits in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 123, 109722. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.E., Coody, T.K., Jeong, M.Y., Berg, J.A., Winge, D.R., Hughes, A.L. Cysteine Toxicity Drives Age-Related Mitochondrial Decline by Altering Iron Homeostasis. Cell 2020, 180(2), 296-310. [CrossRef]

- Blagov, A., Postnov, A., Sukhorukov, V., Popov, M., Uzokov, J., Orekhov, A. Significance of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of Parkinson's Disease. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2024, 29(1), 36. [CrossRef]

- Refsum, H., Smith, A.D., Ueland, P.M., Nexo, E., Clarke, R., McPartlin, J., Johnston, C., Engbaek, F., Schneede, J., McPartlin, C., Scott, J.M. Facts and recommendations about total homocysteine determinations: an expert opinion. Clin. Chem. 2004, 50(1), 3-32. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P., Liu, C., Suliburk, J., Hsu, J.W., Muthupillai, R., Jahoor, F., Minard, C.G., Taffet, G.E., Sekhar, R.V. Supplementing Glycine and N-Acetylcysteine (GlyNAC) in Older Adults Improves Glutathione Deficiency, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Inflammation, Physical Function, and Aging Hallmarks: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78(1), 75-89. [CrossRef]

- Dröge, W. Aging-related changes in the thiol/disulfide redox state: implications for the use of thiol antioxidants. Exp. Gerontol. 2002, 37(12), 1333-1345. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total | IS | HS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 210 | 138 | 72 |

| Stroke type and subtype | AT – 74 (53.6%) CE – 37 (26.8%) Lac – 10 (7.2%) Other – 17 (12.3%) |

ICH – 13 (18.1%) SAH – 59 (81.9%) |

|

| Age, years (Q1; Q3) | 55 (50; 57) | 55 (52; 57) | 55 (49; 57) |

| Male/Female | 161/49 | 103/35 | 58/14 |

| NIHSS | 7.5 (6;10) | 7 (6;10) | 9 (7;15)* |

| mRs | 3 (2;3) | 3 (2;3) | 3 (2;3) |

| Risk factors | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 113 (53.8) | 73 (52.9) | 40 (55.6) |

| DM2, n (%) | 66 (31.4) | 40 (29.0) | 26 (36.1) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 148 (70.5) | 95 (68.8) | 53 (73.6) |

| HHcy: tHcy>15 μM (%) | 44 (21.7) | 31 (23.0) | 13 (19.1) |

| CAD, n (%) | 110 (52.4) | 73 (52.9) | 37 (51.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 132 (62.9) | 91 (65.5) | 41 (57.7) |

| Current cigarette smoking, n (%) | 179 (85.2) | 115 (82.7) | 64 (90.1) |

| Alcohol drinking, n (%) | 104 (49.5) | 66 (47.8) | 38 (52.8) |

| Body mass index | 27.6 (27.2; 28.0) | 28 (27.2; 28) | 27.6 (27.2; 28.6) |

| Body mass index >25 kg/m2, n (%) | 198 (94.3) | 130 (93.5) | 68 (95.8) |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Total cholesterol, mM | 3.5 (1.7; 4.0) | 3.5 (1.7; 4.0) | 3.5 (1.7; 3.9) |

| TG, mM | 2.1 (1.5; 2.7) | 2.1 (1.5; 2.7) | 2.1 (1.7; 2.7) |

| HDL-C, mM | 1.2 (1.0; 1.4) | 1.2 (1.0; 1.4) | 1.2 (1.0; 1.3) |

| LDL-C, mM | 2.4 (2.2; 3.4) | 2.4 (2.2; 3.2) | 2.4 (2.2; 3.4) |

| High atherogenic coefficient (%) | 116 (55.2) | 77 (55.4) | 39 (54.9) |

| Glucose, mM | 4.9 (4.2; 5.1) | 4.9 (4.7; 6.1) | 4.8 (4.7; 5.1) |

| aPTT, s | 33 (27; 35) | 33 (27; 35) | 33 (27; 35) |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 3.8 (3.7; 3.9) | 3.8 (3.6; 4.0) | 3.8 (3.7; 3.9) |

| WBC,109/L | 7.0 (5.25-8.0) | 7.0 (5.0-8.0) | 7.0 (6.0-8.0) |

| PLT,109/L | 278 (234; 312) | 289 (234; 312) | 278 (234;311) |

| CRP, mg/L | 4 (3;6) | 4 (3;6) | 4 (3;7) |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 4 (3;6) | 4 (3;6) | 4 (3;6) |

| Ferritin, μg/L | 75 (45; 90) | 75 (45; 90) | 75 (45; 90) |

| LMWTs | |||

| tCys, μM | 211 (173; 253) | 213 (171; 251) | 211 (179;255) |

| tGSH, μM | 2.9 (2.3; 3.8) | 3.17 (2.48;3.89) | 2.70 (2.09; 3.34)* |

| tHcy, μM | 11.3 (8.2; 14.7) | 11.5 (8.6; 14.8) | 10.0 (7.8; 14.4) |

| tCG, μM | 20.0 (16.5; 25.0) | 20.0 (16.5; 24.8) | 20.1 (16.5; 26.1) |

| rCys, μM | 13.7 (9.7; 19.1) | 12.9 (9.9; 19.1) | 16.6 (9.3; 18.9) |

| CysS, μM | 49.8 (40.1; 58.3) | 49.3 (39.6; 57.4) | 51.1 (40.9; 61.1) |

| LMWTs | tCys | CysS | rCys | tCG | tHcy | tGSH |

| tCys | - | 0.393*** | -0.178 | 0.551*** | 0.645*** | 0.160 |

| CysS | - | -0.041 | 0.041 | 0.260** | 0.229* | |

| rCys | - | -0.149 |

-0.360*** | -0.230* | ||

| tCG | - | 0.450*** | 0.221* | |||

| tHcy | - | 0.371*** | ||||

| Cholesterol | 0.173 | -0.162 | 0.077 | -0.027 | -0.193 | -0.208* |

| Variable | NIHSS≤13 (N=168) | NIHSS>13 (N=42) | PMann-U |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 55 (50.3; 57) | 55 (49; 58) | 0.72 |

| tCys, μM | 216 (172; 254) | 204 (173; 252) | 0.604 |

| tGSH, μM | 2.89 (2.23; 3.85) | 3.11 (2.60; 3.52) | 0.394 |

| tCG, μM | 19.1 (16.4; 24.8) | 21.1 (18.3; 28.1) | 0.088 |

| tHcy, μM | 11.3 (8.0; 14.8) | 11.1 (9.0; 14.2) | 0.872 |

| CysS, μM | 51.1 (41.0; 59.4) | 44.7 (34.5; 53.4) | 0.0063* |

| rCys, μM | 13.7 (8.9; 18.8) | 13.3 (10.0; 20.3) | 0.6 |

| CysS, μM | Proportion of patients with NIHSS > 13 (%) | RR (p) | OR (95% CI) | Post hoc power, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cohort | ||||

| ≤54 | 34 out of 124 (27.4) | 3.56 (0.0003) |

4.53 (1.80-11.39) |

95.3 |

| >54 | 6 out of 78 (7.7) | |||

| IS | ||||

| ≤54 | 20 out of 87 (23) | 5.29 (0.003) |

6.57 (1.46-29.51) |

84.2 |

| >54 | 2 out of 46 (4.3) | |||

| HS | ||||

| ≤54 | 14 out of 37 (37.8) | 3.12 (0.0069) |

4.41 (1.28-15.23) |

70.2 |

| >54 | 4 out of 33 (12.1) | |||

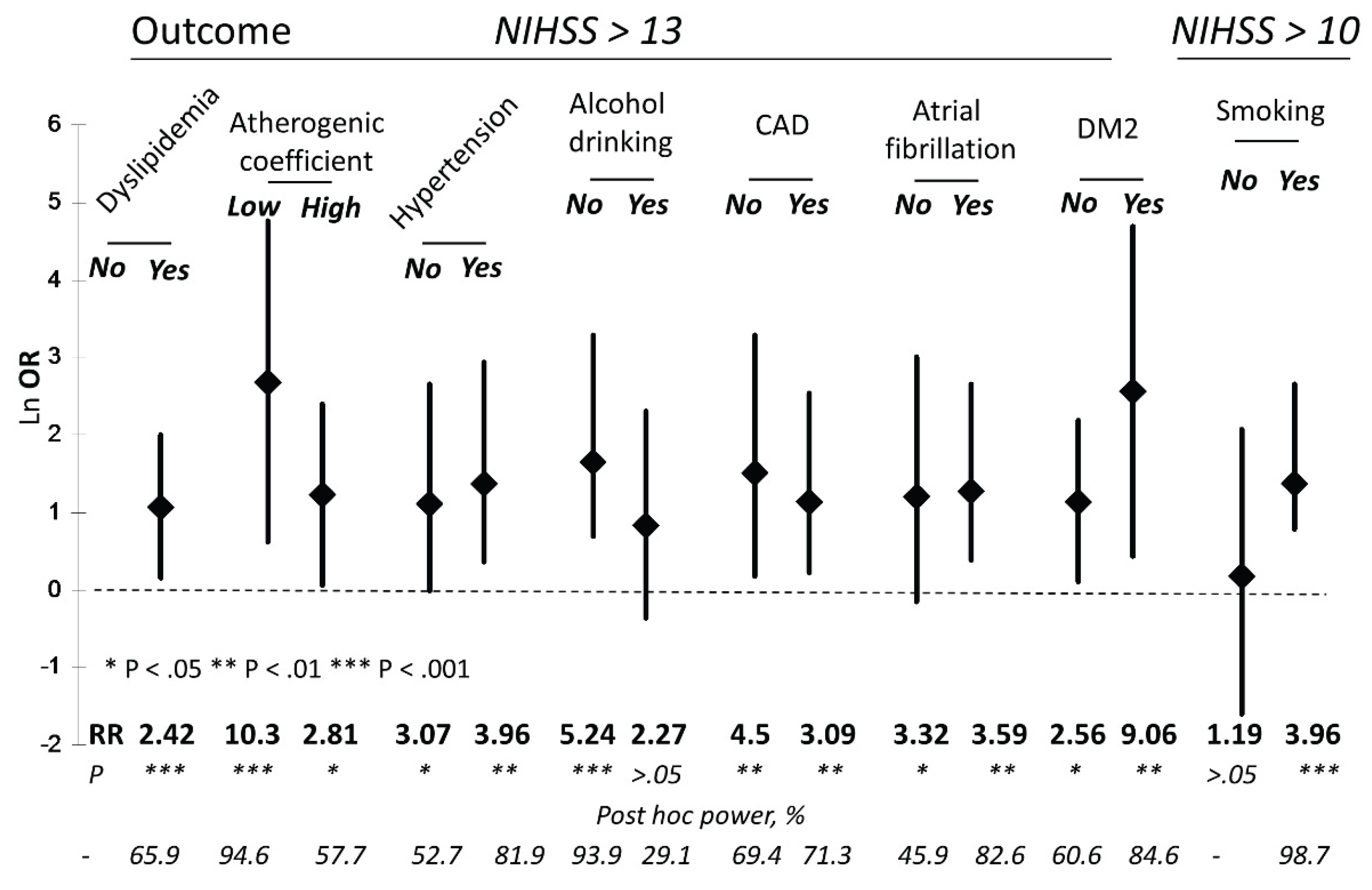

| Factor | NNIHSS>13/ NCysS ≤ 54 μM |

NNIHSS>13/ NCysS > 54 μM |

RR (p) |

OR (95% CI) |

Post hoc power, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 tGSH (0.64-2.48 μM) |

7 / 43 | 2 / 23 | 1.87 (>0.05) |

2.042 (0.39-10.75) |

n/d |

| T3 tGSH (3.42-22.3 μM) |

10 / 34 | 2 / 30 | 4.41 (0.01) |

5.83 (1.16-29.27) |

65.2 |

| T1 tHcy (3.1-9.1 μM) |

9 / 50 | 1 / 16 | 2.88 (>0.05) |

3.29 (0.38-28.24) |

n/d |

| T3 tHcy (13.3-30.9 μM) |

9 / 30 | 2 / 34 | 5.1 (0.005) |

6.86 (1.35-34.93) |

72.6 |

| T1 tCys (62.4-185 μM) |

15 / 54 | 1 / 12 | 3.33 (>0.05) |

4.23 (0.50-35.67) |

n/d |

| T3 tCys (239-385 μM) |

11 / 30 | 2 / 34 | 6.23 (0.0013) |

9.26 (1.85-46.34) |

87.3 |

| T1 tCG (9.1-17.0 μM) |

6 / 38 | 3 / 28 | 1.47 (>0.05) |

1.56 (0.36-6.87) |

n/d |

| T3 tCG (23.6-73.7 μM) |

9 / 44 | 5 / 20 | 0.82 (>0.05) |

0.77 (0.22-2.69) |

n/d |

| T1 rCys (0.87-10.6 μM) |

10 / 34 | 3 / 28 | 2.75 (0.036) |

3.47 (0.85-14.2) |

42 |

| T3 rCys (17.3-51.6 μM) |

14 / 40 | 2 / 22 | 3.85 (0.013) |

5.39 (1.1-26.46) |

62.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).