1. Introduction

The presence of plastic in every compartment of the globe is not just a problem, it’s a pressing global crisis (Villarubia-Gómez et al. 2018; MacLeod et al., 2021; Pinheiro et al., 2023). With plastic production worldwide continuously and dangerously increasing year after year, reaching 400.3 Mtonnes in 2022 (“Plastics – the fast Facts 2023 • Plastics Europe,” n.d.), and a mere 9% of this plastic being recycled (“Think that your plastic is being recycled?,” n.d.), the enormity of the problem is starkly highlighted. The consumption of single-use items, accounting for approximately 50% of the global plastic production, is still a major concern (Miller, 2020; Chen et al., 2021; Arijeniwa et al., 2024). Plastic can reach the marine environment from a variety of sources, including the fishing and aquaculture industries (e.g., rope, waste, fishing gear, and nets), ships and vessels used for commercial and transportation purposes, and also land-based origins like mismanaged waste or urban litter (Cózar et al., 2014; Jambeck et al., 2015; Cassey et al., 2016; Suaria et al., 2016; Haward, 2018). Plastic litter can be classified according to size: macroplastics (> 2.5 cm), mesoplastics (from 5 mm to 2,5 cm), and, most infamous, microplastics (MPs, < 5 mm) (Jeyasanta et al., 2020; Haar et al., 2022). The latter can be derived by the degradation of larger plastic items (macro- and mesoplastics) following UV radiation exposure and mechanical embrittlement (secondary microplastics), or they can be intentionally manufactured for human purposes (primary microplastics). They have been detected in water, sediments, and, of course, various species of marine animals (Andrady, 2011; De Benedetto et al., 2024; Materić et al., 2022; Fraissinet et al., 2024).

Furthermore, oil also represents one of the most historically concerning pollutants in the marine environment. The routine or accidental release of drilling activities, transport, and waste mismanagement into the sea can have significant environmental consequences particularly for marine fauna (Gong et al., 2014; Frasier et al., 2019; Duarte et al., 2020; Kalter and Passow, 2023). The coastline is one of the most exposed areas where oil can persist for long periods of time due to the combined effect of currents, winds, and tides which can enhance its permanence in the area (Gundlach et al., 1978; Asif et al., 2022; Huttel et al., 2022; D’Affonseca et al., 2023).

As a marker of the Anthropocene, a new material named Plastitar which combines the oil derivatives (tar) with plastics (mainly primary origin), has been recently described as “an agglomerate of tar and plastics (mainly microplastics), which are amalgamated and attached to a rock surface” (Domínguez-Hernández et al., 2022). The authors put forth a hypothesis regarding the genesis of this material, proposing that interaction between tar and floating plastics are responsible for its formation. Due to the fluctuations in temperature and UV light throughout the diurnal cycle, tar undergoes a cyclical process of hardening and softening. During this process, floating plastics on the sea surface may become entrained and mixed within tar structure. Ultimately, the volatile components evaporate, and the high molecular weight fraction hardens, leading to the solidification of the blocks. These blocks incorporate not only plastics but also natural materials (Domínguez-Hernández et al., 2022). An alternative hypothesis for the formation of Plastitar is that the hardening and weathering process occurs while the tar is already attached to the rock. Consequently, when plastics or other materials come into contact with the surface, they can become entrapped in the soft crude oil mixture and remain embedded within it during the hardening phase (Saliu et al., 2023b).

Ellrich et al. (2023) conducted a thorough investigation into this phenomenon, uncovering that reports of plastic embedded in tar have been documented since 1973. Furthermore, over the past five decades, ten studies have been conducted on this novel material, with eight of these Plastitar records occurring in proximity to the oil transportation routes from the North Atlantic to the Sea of Japan (Ellrich et al., 2023). A limited number of studies have been conducted on Plastitar in the Mediterranean Sea. The initial observation was documented in 2011 along the Maltese coastline, where concentrations reaching several thousand pellets per square meter were identified within tar deposits attached to emerged and intertidal rocks (Turner & Holmes, 2011). In 2020, Fajković et al. published a report in which they described the presence of a new phenomenon on Croatian islands. They termed these objects “plasto-tarballs,” and they proposed that they function as a sinkhole for MPs due to their high prevalence in the tar matrix (Fajković et al., 2020). A more recent study has provided detailed qualitative and quantitative data on the occurrence of tar and microplastics (MPs) in four distinct regions of the Mediterranean Sea: The North Mediterranean, the Southern Adriatic, the South West Mediterranean, and the Western Mediterranean (Saliu et al., 2023a). The authors observed an exceptionally high concentration of pellets within their tar samples, indicating a pervasive distribution of Plastitar across the investigated sites, which have previously been identified as hotspots for both MPs and oil pollution (Sharma et al., 2021; Asif et al., 2022;).

Despite a general concern and the enactment of legislation to protect the environment from accidental spills the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (“MARPOL 1973 - Final Act and Convention.pdf,” n.d.), global oil consumption and marine transport activities are nowadays increasing, same as plastic production (Saliu et al., 2023b),underscoring the necessity for the dissemination of updated information regarding the interaction between these two forms of pollution. In light of the preceding publications, numerous areas of the Mediterranean Sea, particularly the Italian peninsula, have been subjected to investigation, including the Apulian region. To date, the Northern Ionian Sea, extending between Punta Alice (KR) and Santa Maria di Leuca (LE), has yet to be investigated (Carlucci et al., 2021). Furthermore, this area is home to the Gulf of Taranto, which is characterized by the presence of intense commercial and cruise ship traffic. The present study investigated eleven Plastitar blocks collected along the Ionian Apulian coastline. The objectives of this study were threefold: firstly, the extraction of the plastic particles from the matrix and their qualitative and quantitative characterization; secondly, the identification of the tar composition; and thirdly, the study of the plastic concentration in the analyzed tar blocks. This study will contribute further data to increase the baseline of information related to this new trend in marine pollution, which combines two of the most serious environmental problems of the 20th century: plastic pollution and oil spills.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collecting and Storage of Plastitar Block

Eleven Plastitar blocks were collected in five different sites located along the Ionian coast of the Apulian Region, in the summer season (July 2024) (

Figure 1;

Table 1). Each block was gently removed from the rocks using a chisel as leverage. Once in the laboratory, each Plastitar block was cataloged, wrapped in white paper, and separately stored in a cool and dry place, away from sunlight to preserve its integrity avoiding possible melting due to the high summer temperature.

2.2. Plastics Extraction

Plastitar blocks were photographed and weighed before extracting plastic from the tar structure. Each Plastitar block was broken manually, taking advantage of its malleability, and carefully explored. Plastic extraction was performed using stainless steel tweezers and the particles were carefully placed in 10 mL glass vials. Then 5 mL of esane 96% (Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy) was added to each vial in an ultrasonic bath (15-minute treatment) to remove tar residues that can interfere with subsequent spectroscopic analyses. This cleaning treatment has been repeated multiple times (at least six), substituting the dirty hexane, full of tar residues, with a clean amount of reagent each time.

2.3. Plastic Morphological Characterization

The particles extracted from each sample were collectively weighed using an analytical balance (NAPCO JA-210) and singularly photographed using Leica Stereoscope equipped with Nikon Imaging Systems (NIS) Elements software (version 4.60), to report shapes and colors. The size of plastics was instead determined using ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012).

2.4. Plastics Spectroscopic Characterization

Agilent Technologies FTIR spectrometer, model Cary 680 equipped with a DTGS detector and Pike Miracle ZnSeGermanium ATR attachment, has been used to spectroscopically analyze the particles separated from tar. The measures were carried out in ATR-FTIR mode in the spectral region 600– 4000 cm–1, the resolution was 4 cm–1, and the number of scans was 32 for each spectrum. All the particles present in the samples were analyzed; just in the case of P4, P7, and P11, due to the high number of pellets found, a subset was selected (at least 35% of particles extracted) for the ATR-FTIR characterization.

2.5. Tar NMR Sample Preparation and Characterization

Sample preparation for NMR analysis was performed by dissolving 10 mg of Plastitar compound in 600µl of deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) containing 0.03 v/v% TMS (sodium salt of trimethylsilyl propionic acid) as a chemical shift reference. After filtration, the resulting solution was transferred to a 5 mm NMR tube. Three technical triplicates were performed. For fraction proton distribution, an NMR sample was prepared by dissolving the same amount of compound in 500 µl dichloromethane (CD2Cl2). Spectra acquisition was performed at 300 K on a Bruker Avance III 600 Ascend NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) operating at 600.13 MHz for 1H observation and equipped with a TCI cryoprobe incorporating a z-axis gradient coil and automatic tuning matching (ATM). A one-dimensional experiment (zg Bruker pulse program) was run with 256 scans, 64 K time domain, spectral width 20.0276 ppm (12,019.230 Hz), acquisition time 2.73 s, relaxion delay 2 s and pulse p1 8.6 s. The resulting FIDs were multiplied by an exponential weighting function corresponding to a line broadening of 0.3 Hz before Fourier transformation, automated phasing, and baseline correction. Resonances identification were based on 1H and 13C assignment by 1D and 2D experiments (1H-13C hsqcetgpsisp2.3, and hmbcgplpndqf and 1H decoupled 13C, hr_zg0dc Bruker pulse program) and by comparison with the literature data (Poveda and Molina, 2012; Oliviero Rossi et al., 2018).

3. Results

3.1. Tar NMR Characterization

Structural assignments of Plastitar compound

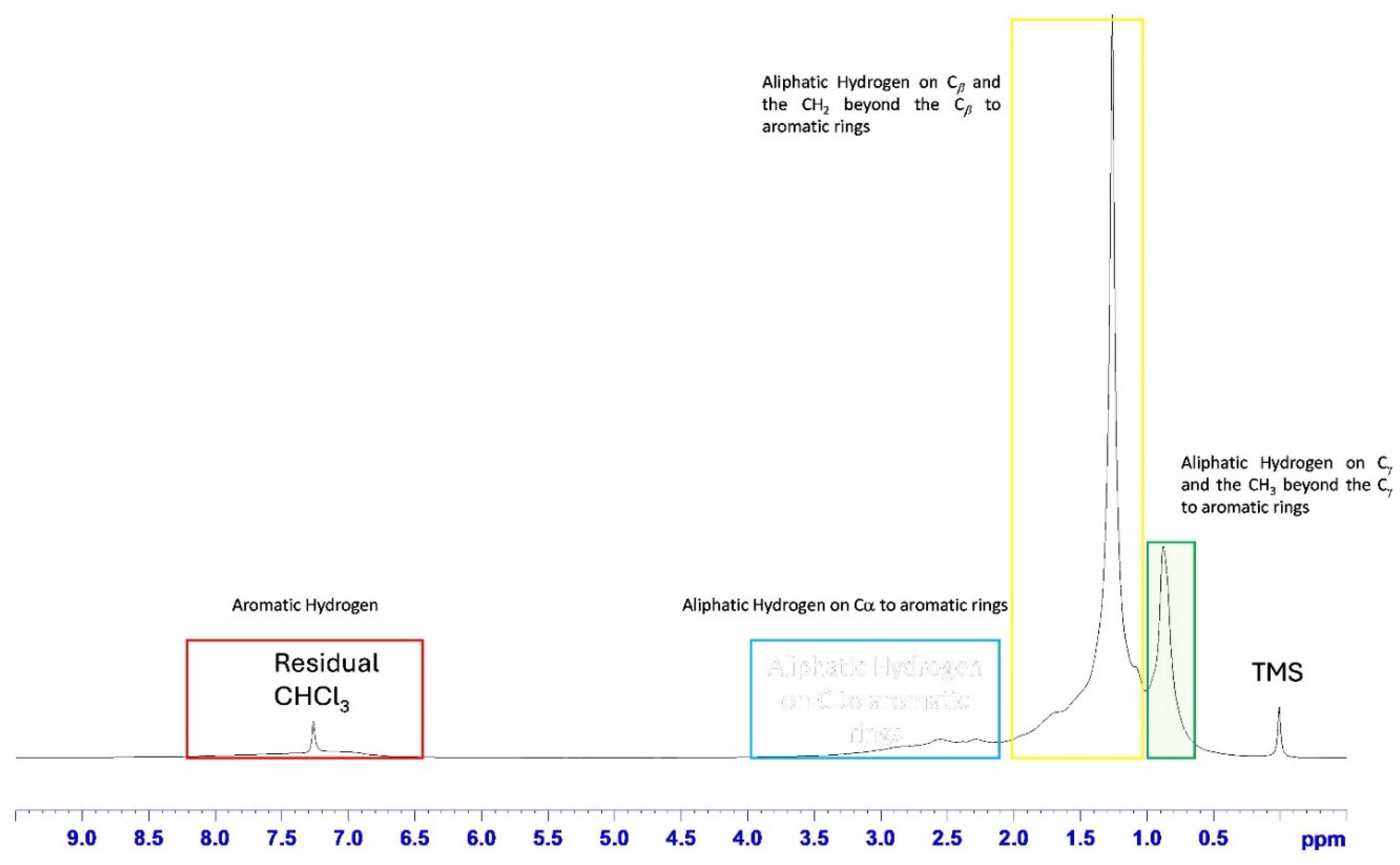

1H NMR spectrum (

Figure 2) showed the presence of four main spectral regions as previously described. Intense signals at 0.88 ppm (carbon at -15-24 ppm) and at 1.26 ppm (carbon at 23-40 ppm) were ascribed to aliphatic hydrogens on C

g, the CH

3 beyond the C

g to aromatic rings and on C

b, the CH

2 beyond the C

bto aromatic rings, respectively. Two broad signals were identified: in the range 2.00-4.00 ppm (carbon at 14-46 ppm) resonances of aliphatic hydrogen on C

a to aromatic rings and, in the range 6.5 -8.00 ppm aromatic hydrogen signals (carbon at 120-130 ppm).

The assigned spectral regions were then integrated after normalization, with the aim of providing the fractional proton distributions. In order to remove the chloroform signal in the aromatic region, the integration procedure was performed on a dichloromethane solvent NMR spectrum, with residual solvent signal at 5.3 ppm (

Figure 1S in

Supplementary Materials). The hydrogen distribution, resulting from the NMR spectrum integration revealed the highest percentage (~ 67%) of aliphatic protons on C

b, the CH

2 beyond the C

bto aromatic rings with respect to the other aliphatic protons (7.68 and 21.82 for hydrogen on C

a to aromatic rings and C

g and the CH

3 beyond the C

g to aromatic rings, respectively).

3.2. Plastic Morphological Characterization

From the eleven Plastitar blocks, 250 particles were extracted; 42 were materials with natural origin like seeds, rocks, and shells, while 208 were plastics, with a concentration of 2.42 plastic items/g of Tar. Most of the particles found were microplastics (75%), the 24% were mesoplastics (5mm to 2.5 cm), just 1% were macroplastics (> 2.5 cm). Pellets represented 90% of the plastic found, 5% were fragments, and the rest were films and filaments. The most frequently found pellets were yellowish. The average weight of tar blocks is 85.69 g, while the average weight of plastics extracted from them is 0.52 g (

Table 2). Some pellets were melted together, while others reported signs of environmental exposure with some calcification residues on their surfaces (

Figure 2S and 3S, respectively, in Supplementary Material).

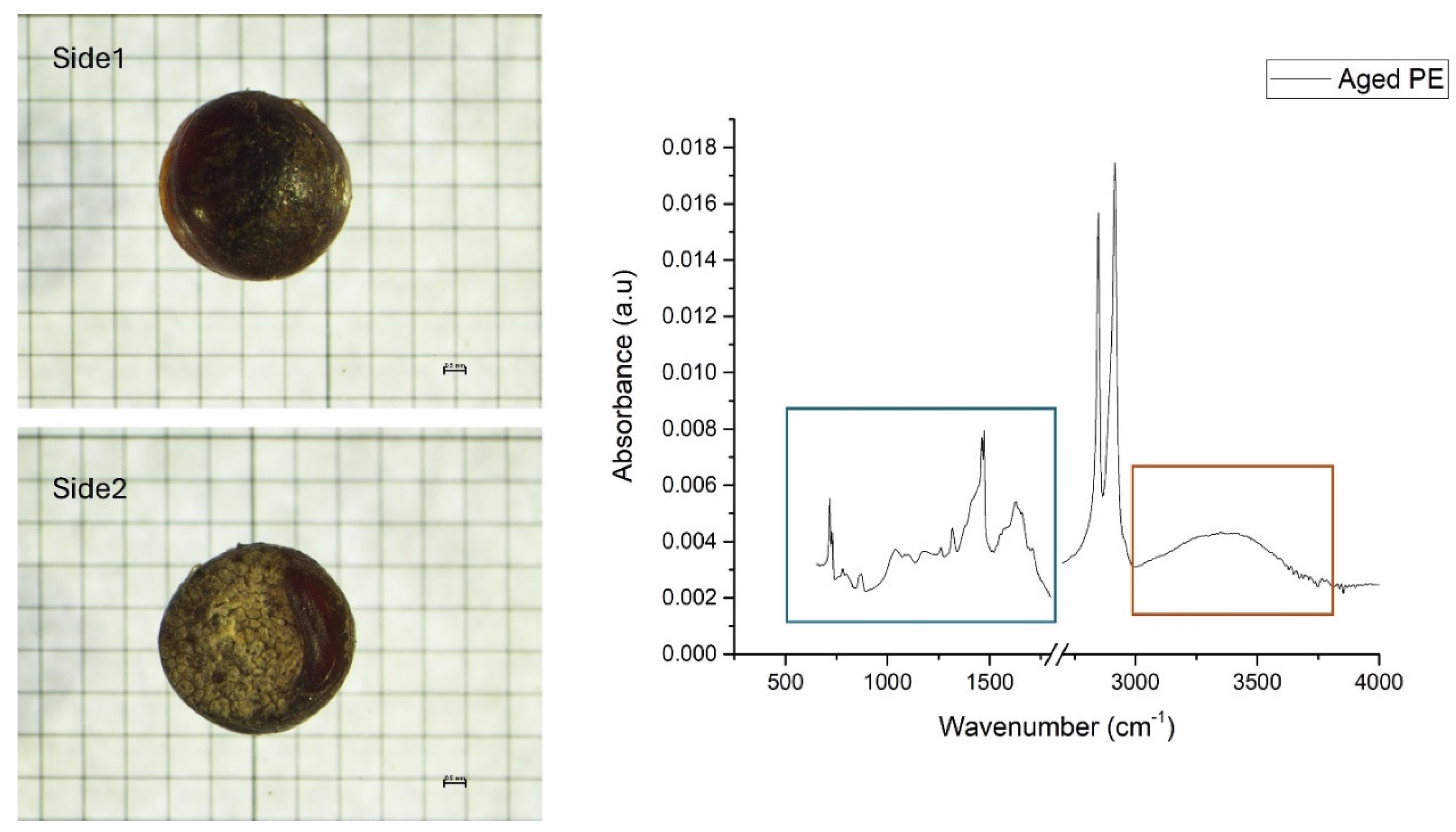

3.3. Plastics ATR-FTIR Characterization

A total of 104 plastics were analyzed 89% of those particles were polyethylene (PE), 6% were Polypropylene (PP), and 5% were cellulose. Some of the spectra presented irregularity in the fingerprinting region (500 – 1500 cm-1) and the region relative to OH stretching (3000 to 3600 cm-1), which were ascribed to aging process due to environmental conditions (

Figure 3).

To better investigate the possible weathering that occurred on the recovered plastics, a pellet whose outer surface was particularly damaged, which resulted in a spectrum difficult to identify, was cut in half to analyze the internal one, showing a defined spectrum of PP, and highlighting how the external parts of plastics can be highly weathered while the inner side is still well preserved (

Figure 4). Also in the PP spectrum, it is possible to see the big bands in the OH region (3000-3500), while the bands in the fingerprinting region are very weak, this situation can indicate a high level of weathering, as can also be seen by the pictures comparing the outside and inside of the pellet.

4. Discussion

To achieve a comprehensive understanding of the tar matrix chemical composition of the Plastitar samples, Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (¹H-NMR) analysis was performed. One of the key advantages of NMR is its ability to simultaneously examine multiple components of a mixture using a single ¹H-NMR spectrum, allowing for the evaluation of the relative amounts of aliphatic and aromatic hydrogen in the mixture (Nciri et al., 2014, 2017; Poveda and Molina 2014). This technique is commonly employed for characterizing both synthetic and natural compounds. Unlike conventional analytical methods, NMR spectroscopy does not require pre-treatment of samples, reducing the time and effort involved in sample preparation. Additionally, it is considered environmentally friendly due to the minimal use of solvents and reduced waste generation (Majid et al., 2014). The matrix has been identified as bitumen. As previously reported by Oliviero Rossi et al. (2018), the resonances assigned to the olefinic protons, in the expected range 4.5-6.00 ppm were not observed, as also confirmed by the assignments in the 2D

1H-

13C hsqc spectrum (

Figure 4S in

Supplementary Materials) which means that the amount of olefinic hydrocarbons, although present, is negligible. While aromatic protons percentage showed the lowest value (3.64 %), as already reported for industrial bitumens (Oliviero Rossi et al., 2018). Bitumen possesses distinct chemo-mechanical characteristics, which is why it is currently one of the primary components in various industrial products. As a product derived from crude oil, it is classified as a viscoelastic material exhibiting adhesive and waterproofing features and its chemical composition is largely influenced by its source (crude oil) and the refining process, both of which contribute to its distinctive chemical and physical traits (Read et al., 2003; Oliviero Rossi et al., 2018:). Chemically, bitumen is composed of roughly 80% carbon, 15% hydrogen, with the remainder made up of two categories of atoms: heteroatoms and metals (Asphalt Institute. Superpave Asphalt Binder Specification (SP-1) 2003).

The plastic found within the tar matrix was predominantly Polyethylene (PE) and Polypropylene (PP) in pellet form, followed by fragments and films. Microplastic was the most abundant size fraction, a finding that aligns with those of other authors in similar studies (Turner and Holmes, 2011; Domínguez-Hernández et al., 2022; Saliu et al., 2023a). Globally, pellets represent the second most significant source of primary microplastics in the environment, with an estimated 450 tonnes of items spilled in oceans and seas worldwide annually (Galgani and Rangel-Buitrago, 2024). Nevertheless, the existing literature frequently indicates that only 2.2% of plastic particles identified in Mediterranean surface waters are pellets (Suaria et al., 2016). It has been hypothesized by some authors that the high abundance of these particles in the tar blocks may be related to a particular association with oil during the formation of the Plastitar (Saliu et al., 2023a). Polyethylene and Polypropylene have been identified in significant quantities in this and other studies on Plastitar. These are the most produced plastics worldwide (Plastics – the fast Facts 2023 • Plastics Europe, n.d.) and the most common polymers found in marine water surfaces due to their low density (Erni-Cassola et al., 2019). This lends support to the theory that plastic and tar can interact on the water surface and, in the second stage, can reach the shores, where they harden and adhere to the rocks.

FT-IR spectroscopy is widely regarded as one of the most prevalent and suitable techniques employed in microplastics research (Primpke et al., 2020). Furthermore, this technique can be employed to highlight and measure changes in the chemical bonds of the plastic due to environmental ageing (Campanale et al., 2023). The attenuated total reflection (ATR) configuration is a commonly employed approach, typically utilized for the analysis of larger particles (Primpke et al., 2020). In fact, at the interface of the crystal, where the internal reflection of the infrared beam occurs, a stationary evanescent wave is found and interacts with the sample: the limited sampling depth of the evanescent wave permits the analysis of high absorbing substances, such as polymers, and it obviates the necessity for sample preparation the only requirement being the intimate contact of the sample with the internal reflection crystal. The resulting IR spectrum of the material pressed onto the surface is comparable to the one obtained by transmission after a simple elaboration of the spectrum (ATR correction).

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the PE spectra display the emergence of new bands within the 1510 to 1770 cm

-1 range of absorbance. These bands exhibit centered peaks at approximately 1614 cm

-1, and a broad band at 3100–3600 cm

-1, which is associated with the vibrational stretching of OH groups. These bands can be attributed to the oxidation of the PE surface during the aging process, as reported by other authors (Niaounakis et al., 2019; Campanale et al., 2023; Di Giulio et al., 2024). In particular, thermo-oxidative degradation can be more extensive in dark-coloured plastics due to the potential for further temperature increases resulting from the accumulation of heat absorbed by the material from solar infrared radiation (Marchetto et al., 2022). Regarding the PP spectrum of the external pellet surface, the characteristic bands of PP are almost undetectable, indicating a high level of degradation. In instances where plastics have been subjected to significant weathering, certain vibrational bands may not be discernible (Renner et al., 2019). Furthermore, the prominent band in the OH stretching region is present in both spectra (internal and external surfaces), which may be attributed to prolonged exposure to water. The photodegradation of plastic debris typically commences with photooxidation, which initiates on the external surface that is exposed to environmental factors. Subsequently, due to the high UV-B radiation extinction coefficient in plastics and the presence of additives that can impede oxygen diffusion, the degradation can be localized outside (Niaounakis et al., 2019; Andrady, 2022;), thereby preserving the core, as evidenced by our IR spectra. An alternative hypothesis for this deterioration is that the plastics were embedded in black tar material and exposed to solar radiation on the beach. This matrix contains chemicals that are prone to photo-oxidation (Roy Chowdhury et al., 2023), suggesting that the permanence in the black tar matrix may have accelerated the degradation pathway of the plastics. The surface may deteriorate in several ways, including the formation of pits, fine cracks, or a loss of colour and strength. The colour of the analysed pellet provides further corroboration of these findings. The environmental weathering process has resulted in significant damage to the surfaces and morphologies of the samples, as illustrated in

Figures 1S and 2S of the

Supplementary Materials. In particular, the white or yellowish hue is indicative of a loss of colour that is consistent with prolonged persistence in the environment (Campanale et al., 2023).

Despite the recent surge in interest surrounding novel plastic forms, the interaction between plastics and tar has been documented since the 1970s. However, the majority of published works on this topic have been conducted in the northern hemisphere. Frequently, plastic and tar have been observed along coastlines exposed to strong winds and intense offshore water currents (Domínguez-Hernández et al., 2022; Ellrich et al., 2023; Saliu et al., 2023a). This evidence lends support to the hypothesis that plastics and tar may accumulate in these circulation areas before being transported to the coastlines by wind-driven currents. This may account for the presence of this considerable quantity of polyolefin, which is typically comprised of floating plastics, within the tar matrix. However, Saliu et al. (2023) also reported that they had examined tar residues carried by the sea and found no evidence of plastic. The formation and accumulation pathways of the Plastitar remain unclear, with potential variations at the regional scale. These pathways are likely linked to wind direction and the levels of pollution from plastics and oil (Ellrich et al., 2023).

The recently reported and defined new types of plastic waste represent a significant environmental risk, particularly in marine ecosystems. This is because they can break down and cause biomagnification, which in turn results in harmful effects on various organisms, as well as increased pollution levels that create unfavorable living conditions. The toxic substances present in tar, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are harmful to marine organisms and can also accumulate in their bodies, leading to a range of adverse effects, including internal injuries and oxidative stress. Similarly, microplastics, due to the chemical additives and persistent substances that remain in their structure and their small size and shape, are responsible for direct and indirect adverse effects on marine fauna (Prokić et al., 2019, 2021; Domínguez-Hernández et al., 2022;).

The presence of Plastitar represents a significant threat to the marine ecosystem, with the potential for unknown environmental consequences. This highlights the urgent need for further data to better understand the extent of the problem and to conduct a thorough investigation into the sources and impacts of this phenomenon. Furthermore, there are still some unanswered questions regarding these emerging plastic litter variants. Consequently, further research is required to gain a full understanding of the potential implications regarding the origin and the presence of Plastitar on shores worldwide. It is likely that the extent of data concerning this pollutant is more widespread than currently assumed. In this context, we present the first report on the presence of Plastitar in the Salento region, thereby expanding our understanding of the distribution of this novel material along the Italian coastline.

5. Conclusions

In a world where plastic production and oil spills are dangerously increasing, the Plastitar formation could be accelerated or promoted, leading to a higher amount of this plastic variant being washed out to beaches and rocky shores. This is not a new phenomenon, and the little information available about it is concerning. Further research is needed to standardize methods for sampling, the extraction of plastics from it, their cleaning, and characterization. The tar profiles and dataset, the same as the plastic spectra, should be implemented and shared to deeply investigate the features of these materials after environmental exposure. Efforts are needed to expand knowledge about the possible direct and indirect impact of Plastitar and other new plastic variants on marine coastal environments and communities. These new types of plastic waste can be red flags to underline how much the pollution problem needs to be managed at the source, which requires new ways to handle recycling systems and more efforts in controlling oil transportation routes. This needs to be managed at the international level, promoting regulations and guidelines on a global scale to face what appears to be a global impact.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

SF analyzed and photographed the samples of Plastitar and wrote the manuscript; EM was responsible for the conceptualization of the research and wrote the manuscript. CF collected and photographed the Plastitar samples and wrote the manuscript; CM carried out the qualitative plastic component analysis on the samples and photographed the items. GEDB performed the spectroscopic characterization of plastics; CG performed the Tar NMR characterization and wrote the manuscript. FF performed the Tar NMR characterization and wrote the manuscript; GB wrote the manuscript; SP wrote, revised and approved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work is partially funded by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4 - Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree n.3175 of 18 December 2021 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union – Next Generation EU; Project code CN_00000033, Concession Decree No. 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP D33C22000960007, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center - NBFC”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- Andrady, A.L., 2022. Weathering and fragmentation of plastic debris in the ocean environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 180, 113761. [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L., 2011. Microplastics in the marine environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 62, 1596–1605. [CrossRef]

- Arijeniwa, V.F., Akinsemolu, A.A., Chukwugozie, D.C., Onawo, U.G., Ochulor, C.E., Nwauzoma, U.M., Kawino, D.A., Onyeaka, H., 2024. Closing the loop: A framework for tackling single-use plastic waste in the food and beverage industry through circular economy- a review. Journal of Environmental Management 359, 120816. [CrossRef]

- Asif, Z., Chen, Z., An, C., Dong, J., 2022. Environmental Impacts and Challenges Associated with Oil Spills on Shorelines. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 10, 762. [CrossRef]

- Asphalt Institute. Superpave Asphalt Binder Specification (SP-1), 3rd ed.; Asphalt Institute: Lexington, KY, USA, 2003.

- Campanale, C., Savino, I., Massarelli, C., Uricchio, V.F., 2023. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy to Assess the Degree of Alteration of Artificially Aged and Environmentally Weathered Microplastics. Polymers 15, 911. [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, R., Capezzuto, F., Cipriano, G., D’Onghia, G., Fanizza, C., Libralato, S., Maglietta, R., Maiorano, P., Sion, L., Tursi, A., Ricci, P., 2021. Assessment of cetacean–fishery interactions in the marine food web of the Gulf of Taranto (Northern Ionian Sea, Central Mediterranean Sea). Rev Fish Biol Fisheries 31, 135–156. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Awasthi, A. K., Wei, F., Tan, Q., & Li, J. (2021). Single-use plastics: Production, usage, disposal, and adverse impacts. Science of the total environment, 752, 141772. [CrossRef]

- Cózar, A., Echevarría, F., González-Gordillo, J. I., Irigoien, X., Úbeda, B., Hernández-León, S.,... & Duarte, C. M. (2014). Plastic debris in the open ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(28), 10239-10244. [CrossRef]

- Cressey, D. (2016). The plastic ocean. Nature, 536(7616), 263-265. [CrossRef]

- De Benedetto, G.E., Fraissinet, S., Tardio, N., Rossi, S., Malitesta, C., 2024. Microplastics determination and quantification in two benthic filter feeders Sabella spallanzanii, Polychaeta and Paraleucilla magna, Porifera. Heliyon 10, e31796. [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, T., De Benedetto, G.E., Ditaranto, N., Malitesta, C., Mazzotta, E., 2024. Insights into Plastic Degradation Processes in Marine Environment by X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Study. IJMS 25, 5060. [CrossRef]

- D’Affonseca, F. M., Reis, F. A. G. V., dos Santos Corrêa, C. V., Wieczorek, A., do Carmo Giordano, L., Marques, M. L.,... & Riedel, P. S. (2023). Environmental sensitivity index maps to manage oil spill risks: A review and perspectives. Ocean & Coastal Management, 239, 106590. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Hernández, C., Villanova-Solano, C., Sevillano-González, M., Hernández-Sánchez, C., González-Sálamo, J., Ortega-Zamora, C., Díaz-Peña, F.J., Hernández-Borges, J., 2022. Plastitar: A new threat for coastal environments. Science of The Total Environment 839, 156261. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C. M., Agusti, S., Barbier, E., Britten, G. L., Castilla, J. C., Gattuso, J. P.,... & Worm, B. (2020). Rebuilding marine life. Nature, 580(7801), 39-51. [CrossRef]

- Ellrich, J.A., Ehlers, S.M., Furukuma, S., 2023. Plastitar records in marine coastal environments worldwide from 1973 to 2023. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1297150. [CrossRef]

- Erni-Cassola, G., Zadjelovic, V., Gibson, M.I., Christie-Oleza, J.A., 2019. Distribution of plastic polymer types in the marine environment; A meta-analysis. Journal of Hazardous Materials 369, 691–698. [CrossRef]

- Fajković, H., Cuculić, V., Cukrov, N., Kwokal, Ž., Pikelj, K., Huljek, L., Marinović, S., n.d. Plasto-tarball - a sinkhole for microplastic (Croatian coast case study).

- Frasier, K.E., Solsona-Berga, A., Stokes, L., Hildebrand, J.A. (2020). Impacts of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill on Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles. In: Murawski, S., et al. Deep Oil Spills. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Fraissinet, S., De Benedetto, G.E., Malitesta, C., Holzinger, R., Materić, D., 2024. Microplastics and nanoplastics size distribution in farmed mussel tissues. Commun Earth Environ 5, 128. [CrossRef]

- Galgani, F., Rangel-Buitrago, N., 2024. White tides: The plastic nurdles problem. Journal of Hazardous Materials 470, 134250. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y., Zhao, X., Cai, Z., O’Reilly, S.E., Hao, X., Zhao, D., 2014. A review of oil, dispersed oil and sediment interactions in the aquatic environment: Influence on the fate, transport and remediation of oil spills. Marine Pollution Bulletin 79, 16–33. [CrossRef]

- Gundlach, E. R., & Hayes, M. O. (1978). Vulnerability of coastal environments to oil spill impacts. Marine technology society Journal, 12(4), 18-27.

- Haarr, M. L., Falk-Andersson, J., & Fabres, J. (2022). Global marine litter research 2015–2020: Geographical and methodological trends. Science of The Total Environment, 820, 153162. [CrossRef]

- Haward, M., 2018. Plastic pollution of the world’s seas and oceans as a contemporary challenge in ocean governance. Nat Commun 9, 667. [CrossRef]

- Huettel, M. (2022). Oil pollution of beaches. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering, 36, 100803. [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J. R., Geyer, R., Wilcox, C., Siegler, T. R., Perryman, M., Andrady, A.,... & Law, K. L. (2015). Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. science, 347(6223), 768-771. [CrossRef]

- Jeyasanta, K.I., Sathish, N., Patterson, J., Edward, J.K.P., 2020. Macro-, meso- and microplastic debris in the beaches of Tuticorin district, Southeast coast of India. Marine Pollution Bulletin 154, 111055. [CrossRef]

- Kalter, V., & Passow, U. (2023). Quantitative review summarizing the effects of oil pollution on subarctic and arctic marine invertebrates. Environmental Pollution, 319, 120960. [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, M., Arp, H. P. H., Tekman, M. B., & Jahnke, A. (2021). The global threat from plastic pollution. Science, 373(6550), 61-65. [CrossRef]

- Majid, A., & Pihillagawa, I. (2014). Potential of NMR spectroscopy in the characterization of nonconventional oils. Journal of Fuels, 2014(1), 390261.

- Marchetto, D., De Ferri, L., Latella, A., Pojana, G., 2022. Micro- and mesoplastics in sea surface water from a Northern Adriatic coastal area. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29, 37471–37497. [CrossRef]

- MARPOL 1973 - Final Act and Convention.pdf, n.d.

- Materić, D., Holzinger, R., Niemann, H., 2022. Nanoplastics and ultrafine microplastic in the Dutch Wadden Sea – The hidden plastics debris? Science of The Total Environment 846, 157371. [CrossRef]

- Miller, S. A. (2020). Five misperceptions surrounding the environmental impacts of single-use plastic. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(22), 14143-14151. [CrossRef]

- Nciri, N., Song, S., Kim, N., & Cho, N. (2014). Chemical characterization of gilsonite bitumen. Journal of Petroleum & Environmental Biotechnology, 5(5), 1.

- Nciri, N., Kim, N., & Cho, N. (2017). New insights into the effects of styrene-butadiene-styrene polymer modifier on the structure, properties, and performance of asphalt binder: The case of AP-5 asphalt and solvent deasphalting pitch. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 193, 477-495.

- Niaounakis, M., Kontou, E., Pispas, S., Kafetzi, M., Giaouzi, D., 2019. Aging of packaging films in the marine environment. Polymer Engineering & Sci 59. [CrossRef]

- Oliviero Rossi, C., Caputo, P., De Luca, G., Maiuolo, L., Eskandarsefat, S., & Sangiorgi, C. (2018). 1H-NMR spectroscopy: A possible approach to advanced bitumen characterization for industrial and paving applications. Applied Sciences, 8(2), 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8020229Plastics – the fast Facts 2023 • Plastics Europe, n.d. . Plastics Europe. URL https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-fast-facts-2023/ (accessed 10.25.23).

- Poveda, J. C., & Molina, D. R. (2012). Average molecular parameters of heavy crude oils and their fractions using NMR spectroscopy. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 84, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Poveda, J. C., Molina, D. R., & Pantoja-Agreda, E. F. (2014). ¹h-and 13c-nmr structural characterization of asphaltenes from vacuum residua modified by thermal cracking. CT&F-Ciencia, tecnología y futuro, 5(4), 49-59.Primpke, S., Christiansen, S.H., Cowger, W., De Frond, H., Deshpande, A., Fischer, M., Holland, E.B., Meyns, M., O’Donnell, B.A., Ossmann, B.E., Pittroff, M., Sarau, G., Scholz-Böttcher, B.M., Wiggin, K.J., 2020. Critical Assessment of Analytical Methods for the Harmonized and Cost-Efficient Analysis of Microplastics. Appl Spectrosc 74, 1012–1047. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, H. T., MacDonald, C., Santos, R. G., Ali, R., Bobat, A., Cresswell, B. J.,... & Rocha, L. A. (2023). Plastic pollution on the world’s coral reefs. Nature, 619(7969), 311-316. [CrossRef]

- Prokić, M.D., Gavrilović, B.R., Radovanović, T.B., Gavrić, J.P., Petrović, T.G., Despotović, S.G., Faggio, C., 2021. Studying microplastics: Lessons from evaluated literature on animal model organisms and experimental approaches. Journal of Hazardous Materials 414, 125476. [CrossRef]

- Prokić, M.D., Radovanović, T.B., Gavrić, J.P., Faggio, C., 2019. Ecotoxicological effects of microplastics: Examination of biomarkers, current state and future perspectives. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 111, 37–46. [CrossRef]

- Read, J.; Whiteoak, D. The Shell Bitumen Handbook, 5th ed.; Thomas Telford Publishing: London, UK, 2003.

- Renner, G., Sauerbier, P., Schmidt, T.C., Schram, J., 2019. Robust Automatic Identification of Microplastics in Environmental Samples Using FTIR Microscopy. Anal. Chem. 91, 9656–9664. [CrossRef]

- Roy Chowdhury, P., Medhi, H., Bhattacharyya, K.G., Hussain, C.M., 2023. Emerging plastic litter variants: A perspective on the latest global developments. Science of The Total Environment 858, 159859. [CrossRef]

- Saliu, F., Compa, M., Becchi, A., Lasagni, M., Collina, E., Liconti, A., Suma, E., Deudero, S., Grech, D., Suaria, G., 2023a. Plastitar in the Mediterranean Sea: New records and the first geochemical characterization of these novel formations. Marine Pollution Bulletin 196, 115583. [CrossRef]

- Saliu, F., Lasagni, M., Clemenza, M., Chubarenko, I., Esiukova, E., Suaria, G., 2023b. The interactions of plastic with tar and other petroleum derivatives in the marine environment: A general perspective. Marine Pollution Bulletin 197, 115753. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., Sharma, V., Chatterjee, S., 2021. Microplastics in the Mediterranean Sea: Sources, Pollution Intensity, Sea Health, and Regulatory Policies. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 634934. [CrossRef]

- Suaria, G., Avio, C. G., Mineo, A., Lattin, G. L., Magaldi, M. G., Belmonte, G.,... & Aliani, S. (2016). The Mediterranean Plastic Soup: synthetic polymers in Mediterranean surface waters. Scientific reports, 6(1), 37551. [CrossRef]

- Think that your plastic is being recycled? Think again. [WWW Document], n.d.. MIT Technology Review. URL https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/10/12/1081129/plastic-recycling-climate-change-microplastics/ (accessed 10.14.24).

- Turner, A., Holmes, L., 2011. Occurrence, distribution and characteristics of beached plastic production pellets on the island of Malta (central Mediterranean). Marine Pollution Bulletin 62, 377–381. [CrossRef]

- Villarrubia-Gómez, P., Cornell, S. E., & Fabres, J. (2018). Marine plastic pollution as a planetary boundary threat–The drifting piece in the sustainability puzzle. Marine policy, 96, 213-220.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).