Submitted:

30 November 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BEB | Binary–encounter–Bethe |

| BED | Binary–encounter-dipole |

| HF | Hartree–Fock |

| ICS | Ionization cross section |

| OVGF | Outer valence Green function |

| TCS | Total cross section |

Appendix A. Binding Energies, B, Kinetic Orbital Energies U and HOMOs Energies of the Studied Targets

Appendix A.1. Calculated with the HF Method Binding Energies B, Kinetic Orbital Energies U of the Studied Targets

| Orbital No. | B (eV) | U (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 423.70 | 602.02 |

| 2 | 423.70 | 602.02 |

| 3 | 307.75 | 436.01 |

| 4 | 307.37 | 435.98 |

| 5 | 307.37 | 435.98 |

| 6 | 306.0 | 435.86 |

| 7 | 36.188 | 49.142 |

| 8 | 32.871 | 56.227 |

| 9 | 29.490 | 45.438 |

| 10 | 24.570 | 45.287 |

| 11 | 24.509 | 45.486 |

| 12 | 20.373 | 28.960 |

| 13 | 19.422 | 45.659 |

| 14 | 17.855 | 35.506 |

| 15 | 16.362 | 37.558 |

| 16 | 16.136 | 40.181 |

| 17 | 15.964 | 29.630 |

| 18 | 12.927 | 50.071 |

| 19 | 11.650 | 36.887 |

| 20 | 11.329 | 50.811 |

| 21 | 10.372 | 30.498 |

| Orbital No. | B (eV) | U (eV) | B (eV) | U (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2852.9 | 3731.1 | 2853.4 | 3731.1 |

| 2 | 424.16 | 602.00 | 424.13 | 602.02 |

| 3 | 424.16 | 602.01 | 424.13 | 602.02 |

| 4 | 309.71 | 436.13 | 308.08 | 436.01 |

| 5 | 307.84 | 435.99 | 307.95 | 435.87 |

| 6 | 307.84 | 435.99 | 307.82 | 435.97 |

| 7 | 306.44 | 435.85 | 307.81 | 436.08 |

| 8 | 287.58 | 593.54 | 288.09 | 593.55 |

| 9 | 218.69 | 560.89 | 219.20 | 560.91 |

| 10 | 218.61 | 561.98 | 219.12 | 562.03 |

| 11 | 218.60 | 562.07 | 219.12 | 562.05 |

| 12 | 37.053 | 49.944 | 36.686 | 49.013 |

| 13 | 33.520 | 56.392 | 33.318 | 56.271 |

| 14 | 31.419 | 61.358 | 32.204 | 62.570 |

| 15 | 29.034 | 58.689 | 28.678 | 60.286 |

| 16 | 25.241 | 45.425 | 25.224 | 45.271 |

| 17 | 24.247 | 51.509 | 24.414 | 51.024 |

| 18 | 20.215 | 34.408 | 20.679 | 30.373 |

| 19 | 20.116 | 45.191 | 20.211 | 45.843 |

| 20 | 17.870 | 41.651 | 17.228 | 54.826 |

| 21 | 16.944 | 31.629 | 16.981 | 37.236 |

| 22 | 16.822 | 37.613 | 16.661 | 30.324 |

| 23 | 16.212 | 50.782 | 16.589 | 41.560 |

| 24 | 13.492 | 54.721 | 14.032 | 51.316 |

| 25 | 13.221 | 50.513 | 13.350 | 53.848 |

| 26 | 12.666 | 60.695 | 13.279 | 61.505 |

| 27 | 12.154 | 37.355 | 12.082 | 36.944 |

| 28 | 11.733 | 54.286 | 11.625 | 52.252 |

| 29 | 10.351 | 39.768 | 10.204 | 41.309 |

| Orbital No. | B (eV) | U (eV) | B (eV) | U (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13334 | 16195 | 13335 | 16195 |

| 2 | 1772.9 | 3195.1 | 1773.5 | 3195.1 |

| 3 | 1592.2 | 3166.6 | 1592.8 | 3166.6 |

| 4 | 1592.2 | 3166.9 | 1592.7 | 3166.9 |

| 5 | 1592.2 | 3166.9 | 1592.7 | 3166.9 |

| 6 | 424.20 | 602.00 | 424.13 | 602.02 |

| 7 | 424.20 | 602.01 | 424.13 | 602.02 |

| 8 | 309.57 | 436.14 | 308.11 | 436.01 |

| 9 | 307.85 | 435.98 | 307.86 | 435.76 |

| 10 | 307.85 | 435.99 | 307.85 | 435.97 |

| 11 | 306.39 | 435.85 | 307.79 | 436.20 |

| 12 | 267.70 | 766.10 | 268.24 | 766.10 |

| 13 | 202.77 | 709.25 | 203.31 | 709.26 |

| 14 | 202.55 | 710.98 | 203.09 | 711.05 |

| 15 | 202.53 | 711.12 | 203.08 | 711.07 |

| 16 | 86.836 | 586.40 | 87.380 | 586.39 |

| 17 | 86.732 | 587.14 | 87.268 | 587.00 |

| 18 | 86.709 | 587.01 | 87.266 | 587.21 |

| 19 | 86.450 | 587.89 | 86.996 | 587.86 |

| 20 | 86.450 | 587.85 | 86.996 | 587.90 |

| 21 | 36.971 | 49.811 | 36.677 | 49.056 |

| 22 | 33.520 | 56.435 | 33.324 | 56.278 |

| 23 | 30.376 | 51.103 | 30.881 | 56.097 |

| 24 | 27.840 | 77.019 | 27.691 | 75.621 |

| 25 | 25.227 | 45.492 | 25.192 | 45.371 |

| 26 | 24.106 | 55.105 | 24.292 | 54.455 |

| 27 | 20.118 | 34.612 | 20.677 | 30.583 |

| 28 | 20.082 | 45.384 | 20.141 | 45.914 |

| 29 | 17.737 | 41.273 | 16.966 | 37.295 |

| 30 | 16.817 | 37.635 | 16.706 | 40.492 |

| 31 | 16.812 | 30.927 | 16.568 | 29.828 |

| 32 | 15.685 | 52.194 | 16.185 | 59.049 |

| 33 | 13.052 | 59.804 | 13.126 | 55.832 |

| 34 | 12.248 | 49.590 | 13.012 | 52.312 |

| 35 | 12.158 | 37.334 | 12.235 | 62.538 |

| 36 | 12.018 | 52.657 | 12.087 | 36.963 |

| 37 | 11.181 | 68.587 | 11.498 | 57.508 |

| 38 | 10.165 | 47.962 | 10.039 | 47.489 |

Appendix A.2. Calculated with the OVGF Method HOMOs Energies of the Studied Targets

| C4H4N2 | 2-C4H3ClN2 | 5-C4H3ClN2 | 2-C4H3BrN2 | 5-C4H3BrN2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18.144 | 18.561 | 18.023 | 18.529 | |

| 17.851 | 17.923 | 17.768 | 17.808 | |

| 18.302 | 16.220 | 15.839 | 16.047 | 15.062 |

| 17.293 | 15.278 | 15.129 | 15.107 | 15.080 |

| 16.204 | 15.027 | 15.045 | 14.982 | 15.006 |

| 14.693 | 14.678 | 14.890 | 14.100 | 14.767 |

| 14.630 | 11.845 | 13.108 | 11.655 | 12.290 |

| 14.565 | 12.382 | 12.297 | 11.603 | 11.591 |

| 11.331 | 11.675 | 11.690 | 11.599 | 11.583 |

| 11.327 | 11.640 | 11.632 | 10.497 | 11.204 |

| 10.461 | 10.178 | 10.075 | 10.301 | 10.184 |

| 9.804 | 10.120 | 10.040 | 9.911 | 9.865 |

References

- Joshipura, K. N.; Mason, N. Atomic-Molecular Ionization by Electron Scattering, 1st ed.; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2019; pp. 177–217.

- Szmytkowski, Cz.; Możejko, P. Recent total cross section measurements in electron scattering from molecules. Eur. Phys. J. D 2020, 74, 90. [CrossRef]

- Boudaiffa, B.; Cloutier, P.; Hunting, D.; Huels, M. A.; Sanche, L. Resonant formation of DNA strand breaks by low-energy (3 to 20 eV) electrons. Science 2000, 287, 1658–1600. [CrossRef]

- Sanche, L. Beyond radical thinking. Nature 2009, 461, 358–359. [CrossRef]

- McKee, A. D.; Schaible, M. J.; Rosenberg, R. A.; Kundu, S.; Orlando, T. M. Low energy secondary electron induced damage of condensed nucleotides. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 204709. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zheng, Li.; Sanche, L. Low–energy electron damage to condensed–phase DNA and its constituents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7879. [CrossRef]

- Cobut, V.; Fongillo, Y.; Patau, J. P.; Goulet, T.; Fraser, M. J.; Jay-Gerin, J. P. Monte-Carlo simulation of fast electron and proton tracks in liquid water.I. Physical and physico-chemical aspects. Radiat. Phys. Chem., 1998, 51, 229–243.

- Villagrasa, C.; Francis, Z.; Incerti, S. Physical models implemented in the Geant4-DNA extension of the Geant-4 toolkit for calculating initial radiation damage at the molecular level. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2011, ı143, 214–218.

- Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Aso, T.; Bagli, E.; Bagulya, A.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; Beck, B. R.; Bogdanov, A. G.; Brandt, D.; Brown, J. M. C.; Burkhardt, H.; Canal, Ph.; Cano-Ott, D.; Chauvie, S.; Cho, K.; Cirrone, G. A. P.; Cooperman, G.; Cortés-Giraldo, M. A.; Cosmo, G.; Cuttone, G.; Depaola, G.; Desorgher, L.; Dong, X.; Dotti, A.; Elvira, V. D.; Folger, G.; Francis, Z.; Galoyan, A.; Garnier, L.; Gayer, M.; Genser, K. L.; Grichine, V. M.; Guatelli, S.; Gueye, P.; Gumplinger, P.; Howard, A.S.; Hřivnáčová, I.; Hwang, S.; Incerti, S.; Ivanchenko, A.; Ivanchenko, V. N.; Jones, F. W.; Jun, S. Y.; Kaitaniemi, P.; Karakatsanis, N.; Karamitros, M.; Kelsey, M.; Kimura, A.; Koi, T.; Kurashige, H.; Lechner, A.; Lee, S. B.; Longo, F.; Maire, M.; Mancusi, D.; Mantero, A.; Mendoza, E.; Morgan, B.; Murakami, K.; Nikitina, T.; Pandola, L.; Paprocki, P.; Perl, J.; Petrović, I.; Pia, M. G.; W. Pokorski, W.; Quesada, J. M.; Raine, M.; Reis, M. A.; Ribon, A.; Ristić Fira, A.; F. Romano, F.; Russo, G.; Santin, G.; Sasaki, T.; Sawkey, D.; Shin, J. I.; Strakovsky, I. I.; Taborda, A.; Tanaka, S.; Tomé, B.; Toshito, T.; Tran, H. N.; Truscott, P. R.; Urban, L.; Uzhinsky, V.; Verbeke, J. M.; Verderi, M.; Wendt, B. L.; Wenzel, H.; Wright, D. H.; Wright, D. M.; Yamashita, T.; Yarba, J.; Yoshida, H. Recent developments in Geant4 Nucl. Instr. Meth. Phys. Res. A 2016, ı835, 186–225.

- Rosales, L. F.; Incerti, S.; Francis, Z.; Bernal, M. A. Accounting for radiation–induced indirect damage on DNA with the Geant 4–DNA code. Phys. Med. 2018, 51, 108–116. [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.; Traoré-Dubuis, A.; Álvarez, L.; Lozano, A. I.; Ren, X.; Dorn, A.; Limão-Vieira, P.; Blanco, F.; Oller, J. C.; Muñoz, A.; Garcáa-Abenza, A.; Gorfinkiel, J. D.; Barbosa, A. S.; Bettega, M. H. F.; Stokes, P.; White, R. D.; Jones, D. B.; Brunger M. J.; García, G. A Complete cross section set for electron scattering by pyridine: Modelling electron transport in the energy range 0–100 eV. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6947. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A. I.; Álvarez, L.; García-Abenza, A.; Guerra C.; Kossoki, F.; Rosado, J.; Blanco, F.; Oller, J. C.; Hasan, M.; Centurion, M.; Weber, T.; Slaughter, D. S.; Mootheril, D. M.; Dorn, A.; Kumar, S.; Limão-Vieira, P.; Colmenares, R.; García, G. Electron scattering from 1-methyl-5-nitroimidazole: Cross–sections for modeling electron transport through potential radiosensitizers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12182. [CrossRef]

- Tylińska, B.; Wiatrak, B.; Czyżnikowska, Ż.; Cieśla-Niechwiadowicz, A.; Gębarowska, E.; Janicka-Kłos, A. Novel pyrimidine derivatives as potential anticancer agents: Synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular doking study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 22, 3825. [CrossRef]

- Al-Tuwaijri, H. M.; Al-Abdullah, E. S.; El-Rashedy, A. A.; Anasari, S. A.; Almomen, A.; Alshibl, H. M.; Haiba, M. E.; Alkahtani, H. M. New indazol–pyrimidine–based derivatives as selective anticancer agents: Design, synthesis, and in silico studies. Molecules 2023, 28, 3664. [CrossRef]

- Myriagkou, M.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Deligiannidou, G.-E.; Patsilinakos, A.; Kontogiorgis, Ch.; Pontiki, E. Novel pyrimidine derivatives as antioxidant and anticancer agents: Design, synthesis and molecular modeling studies. Molecules 2023, 28, 3913. [CrossRef]

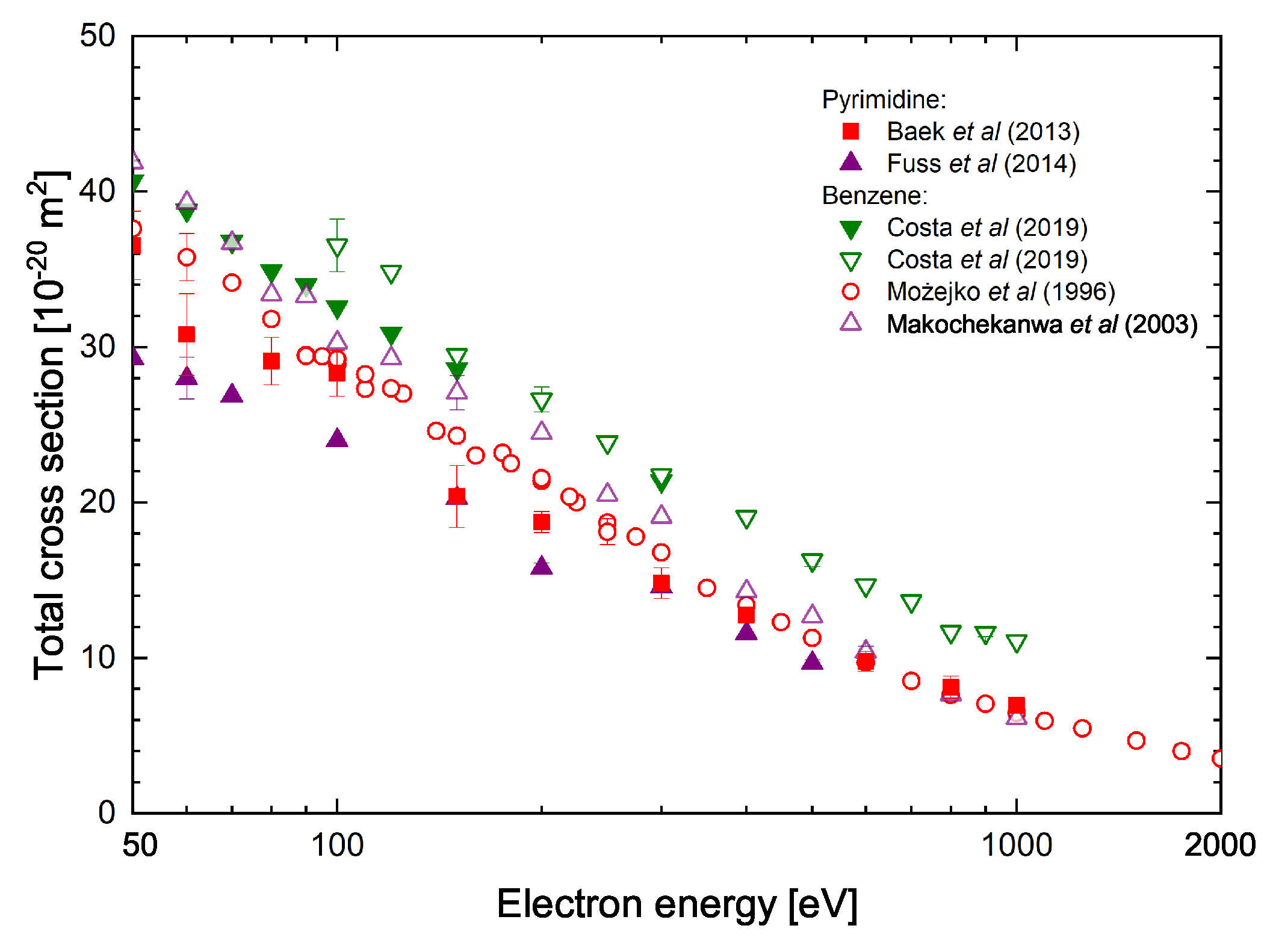

- Baek, W. Y.; Arndt, A.; Bug, M. U.; Rabus, H.; Wang, M. Total electron–scattering cross sections of pyrimidine. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 032702. [CrossRef]

- Fuss, M. C.; Sanz, A. G.; Blanco, F.; Oller, J. C.; Limão-Vieira, P.; Brunger, M. J.; García, G. Total electron scattering cross sections for pyrimidine and pyrazine as measured using a magnetically confined experimental system. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 488, 012048. [CrossRef]

- Maljković, J. B.; Milosavljević, A. R.; Blanco, F.; and Šević, D.; Garcıa, G.; Marinković, B. P. Absolute differential cross sections for elastic scattering of electrons from pyrimidine Phys. Rev. A 2009, 79, 052706. [CrossRef]

- Palihawadana, P.; Sullivan, J.; Brunger, M. J.; Winstead, C.; McKoy, V.; Garcıa, G.; Blanco, F.; Buckman, S. Low–energy elastic electron interactions with pyrimidine. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 062702. [CrossRef]

- Palihawadana, P.; Machacek, J. R.; Makochekanwa, C.; Sullivan, J. P.; Brunger, M. J.; Winstead, C.; McKoy, V.; Garcıa, G.; Blanco, F.; Buckman, S. J. Electron and positron scattering from pyrimidine. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2012, 388, 052079. [CrossRef]

- Maljković, J. B. Absolute differential cross sections for elastic electron scattering from small biomolecules. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 565, 012005. [CrossRef]

- W. Y. Baek, W. Y.; Bug, M. U.; Rabus, H. Differential elastic electron–scattering cross sections of pyrimidine in the energy range between 20 eV and 1 keV. Phys. Rev A 2014, 89, 062716. [CrossRef]

- Colmenares, R.; Sanz, A. G.; Fuss, M. C.; Blanco, F.; García, G. Stopping power for electrons in pyrimidine in the energy range 20–3000eV. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 2014, 83 Part B, 91-94. [CrossRef]

- Regeta, K.; Allan, M.; Winstead, C.; McKoy, V.; Mašın, Z.; Gorfinkiel, J. D. Resonance effects in elastic cross sections for electron scattering on pyrimidine: Experiment and theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 024301. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. B.; Bellm, S. M.; Blanco, F.; García G.; Limão-Vieira, P. Brunger, M. J. Differential cross sections for electron impact excitation of pyrimidine. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 074304. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. B.; Ellis-Gibbings, L.; García, G.; Nixon, K. L.; Lopes, M. C. A., Brunger, M. J. Intermediate energy cross sections for electron–impact vibrational–excitation of pyrimidine. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143, 094304. [CrossRef]

- Regeta K.; Allan, M.; Mašín, Z.; Grofinkiel, J. D. Absolute cross sections for electronic excitation of pyrimidine by electron impact. J. Chem. Phys., 2016, 144, 024302. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, N.; Antony, B. Electron and positron interaction with pyrimidine: A theoretical investigation. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123, 124906. [CrossRef]

- Mašín, Z.; Gornfinkiel, J. D. Effect of the Third π★ Resonance on the angular distributions for electron–pyrimidine scattering. Eur. Phys. J. D 2016, 70, 150. [CrossRef]

- Bug, M. U.; Baek W. Y.; Rabus, H.; Villagrasa, C.; Meylan, S.; Rosenfeld, A. B. An electron–impact cross section data set (10 eV–1 keV) of DNA constituents based on consistent experimental data: A requisite for Monte Carlo simulations. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2017, 130, 459–479. [CrossRef]

- Luthra, M.; Bharadvaja, A.; Prashant, A.; Baluja, K. L. Electron scattering from pyrimidine up to 5 keV. Braz. J. Phys. 2024, 54, 116. [CrossRef]

- Linert, I.; Dampc, M.; Mielewska, B.; Zubek, M. Cross sections for ionization and ionic fragmentation of pyrimidine molecules by electron collisions. Eur. Phys. J. D 2012, 66, 20. [CrossRef]

- Dinger, M.; Baek, W. Y.; Rabus, H. Comparative experimental and theoretical study on doubly differential electron–impact ionization cross sections of pyrimidine. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 109, 062813. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, W.; Luna, H.; Sigaud, L.; Tavares, A. C.; Montenegro, E. C. Absolute total and partial dissociative cross sections of pyrimidine at electron and proton intermediate impact velocities. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 140, 064309. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Naghma, R.; Antony, B. Electron Impact total ionisation cross section for simple bio–molecules: A theoretical approach. Mol. Phys. 2014, 112, 1201–1209. [CrossRef]

- Champion, Ch.; Quinto, M. A.; Weck, Ph. F. Electron– and proton–induced ionization of pyrimidine. Eur. Phys. J. D 2015, 69, 127. [CrossRef]

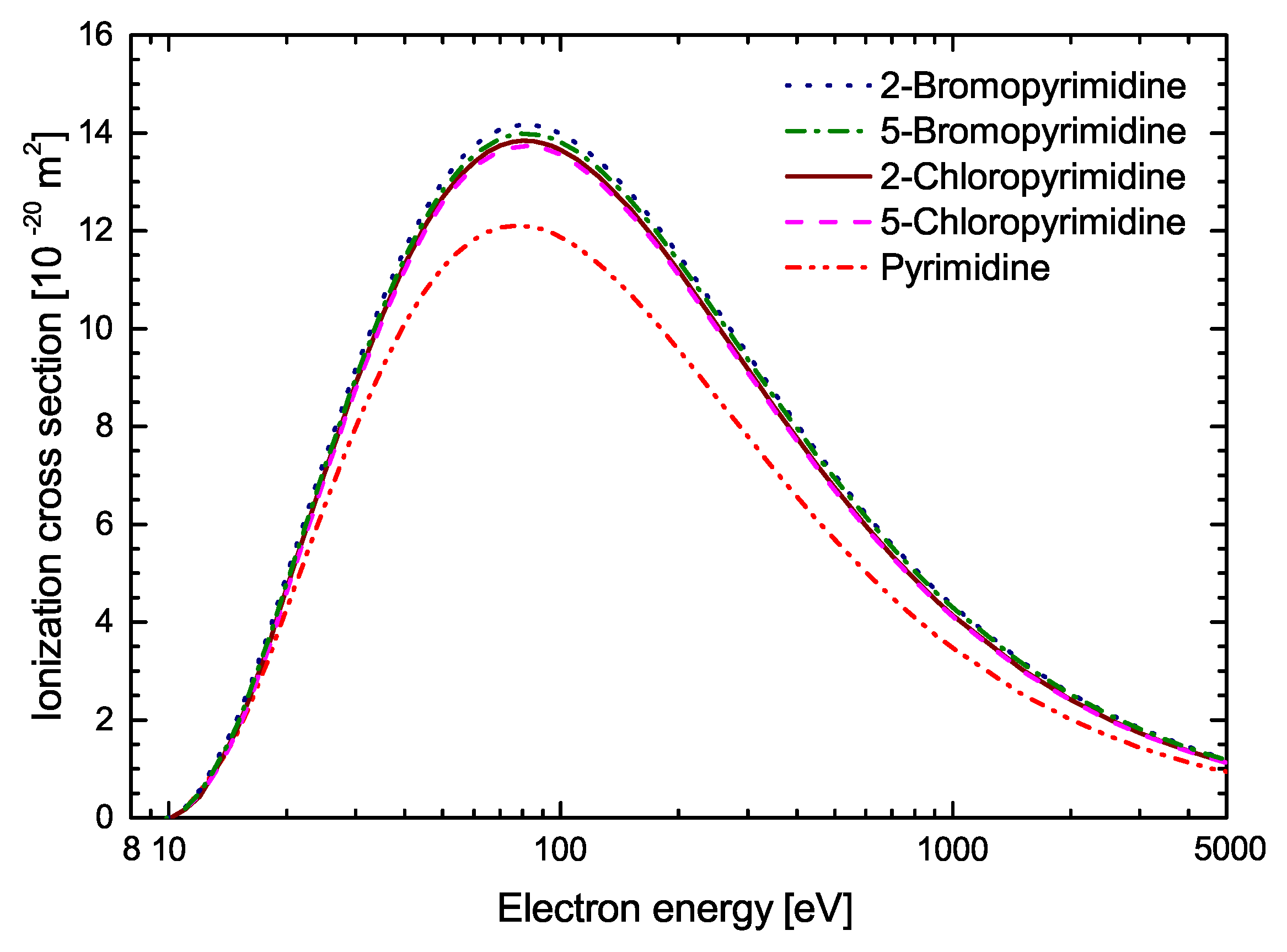

- Żywicka, B.; Możejko P. Electron–impact ionization cross sections calculations for purine and pyrimidine molecules. In Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Elementary Processes in Atomic Systems, Bratislava, Slovakia, 9–12 July 2014; 236–239.

- Modelli, A.; Bolognesi, P.; Avaldi, L. Temporary anion states of pyrimidine and halopyrimidines. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 10775–10782. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A. S.; Bettega, M. H. F. Shape resonances in low–energy–electron collisions with halopyrimidines. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 214301. [CrossRef]

- Możejko, P.; Sanche, L. Cross section calculations for electron scattering from DNA and RNA bases. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2003, 42, 201–211. [CrossRef]

- Możejko, P.; Sanche, L. Cross sections for electron scattering from selected components of DNA and RNA. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2005, 73, 77–84. [CrossRef]

- Możejko, P. Calculations of electron impact ionization cross section for simple biomolecules: Formic and acetic acids. Eur. Phys. J. Special Topics 2007, 144, 233–237. [CrossRef]

- Dampc, M.; Możejko, P.; Zubek, M. Electron impact ionization and cationic fragmentation of the pyridazine molecules. Eur. Phys. J. D 2018, 72, 216. [CrossRef]

- Szmytkowski, Cz.; Stefanowska, S.; Tańska, N.; Żywicka, B.; Ptasińska-Denga, E.; Możejko, P. Cross sections for electron collision with pyridine [C5H5N] molecule. Mol. Phys. 2018, 117, 395–403. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. K.; Rudd, M. E. Binary–encounter–dipole model for electron–impact ionization. Phys. Rev. A 1994, 50, 3954–3967. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.; Kim, Y. K.; Rudd, M. E. New model for electron--impact ionization cross sections of molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 104, 2956-2966. [CrossRef]

- Vriens, L. Binary–encounter and classical collision theories. In Case Studies in Atomic Physics 1; McDaniel, E. W., McDowell, M. R. C., Eds.; North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1969; pp. 335–398.

- Bethe, H. Zur Theorie des Durchgangs schneller Korpuskularstrahlen durch Materie. Ann. Phys. 1930, 397, 325–400. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M. J.; et al, GAUSSIAN 03, Revision B.05, Gaussian: Pittsburgh, USA, 2003.

- Cederbaum, L. S. One–body Green’s function for atoms and molecules: Theory and application. J. Phys. B 1975, 8, 290–303. [CrossRef]

- von Niessen, W.; Schirmer, J.; Cederbaum, L. S. Computational methods for the one–particle Green’s function. Comp. Phys. Rep. 1984, 1, 57–125. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J. V. Electron binding energies of anionic alkali metal atoms from partial fourth order electron propagator theory calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 89, 6348–6352. [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewski, V. G.; von Niessen, W. Vectorizable algorithm for Green function and many--body perturbation methods. J. Comp. Chem. 1994, 14, 13–18. [CrossRef]

- Berthod, H.; Giessner-Prettre, C.; Pullman, A. Theoretical study of the electronic properties of the purine and pyrimidine components of the nucleic acids. Theoret. Chim. Acta 1966, 5, 53-–68. [CrossRef]

- Kunii, T.L.; Kuroda, H. Ionization potentials and electron affinities of carbo- and heterocyclic π–conjugated molecules. Theoret. Chim. Acta 1968, 11, 97–106. [CrossRef]

- Yencha, A.J.; El-Sayed, M.A. Lowest ionization potentials of some nitrogen heterocyclics. J. Chem. Phys. 1968, 48, 3469–3475. [CrossRef]

- Hush, N.S.; Cheung, A.S., Ionization potentials and donor properties of nucleic acid bases and related compounds. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1975, 34, 11–13. [CrossRef]

- Schwell, M.; Jochims, H.-W.; Baumgartel, H.; Leach, S. VUV Photophysics and dissociative photoionization of pyrimidine, purine, imidazole and benzimidazole in the 7–18 eV photon energy range. Chem. Phys. 2008, 353 145–162. [CrossRef]

- Y.-K. Kim, W. Hwang, N.M. Weinberger, M.A. Ali, M.E. Rudd, M. E. Electron-impact ionization cross sections of atmospheric molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 106 1026–1033. [CrossRef]

- Karwasz, G. P.; Możejko, P.; Song, M.–Y. Electron–impact ionization of fluoromethanes–Review of experiments and binary–encounter models. Int. J. Mass. Spectrom. 2014, 365-366 232–237. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Brunger, M. J.; Campbell, L.; Kato, H.; Hoshino, M.; Rau, A. R. P. Scaled plane–wave Born cross sections for atoms and molecules. Rev.Mod. Phys. 2016, 88, 025004. [CrossRef]

- Lampe, F. W., Franklin, J. L.; Field, F. H. Cross sections for ionization by electrons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 6129–6132. [CrossRef]

- Schram, B. L.; Van der Wiel, M. J.; de Heer, F. J.; Moustafa, H. R. Absolute gross ionization cross sections for electrons (0.6–12 keV) in hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Phys. 1966, 44, 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Możejko, P.; Kasperski, G.; Szmytkowski, Cz.; Karwasz, G. P.; Brusa, R. S.; Zecca, A. Absolute total cross section measurements for electron scattering on benzene molecules. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 257, 309–313. [CrossRef]

- Makochekanwa, C.; Sueoka, O.; M. Kimura, M. Comparative study of electron and positron scattering from benzene (C6H6) and hexafluorobenzene (C6F6) molecules. Phys. Rev. A 2003, 68, 032707. [CrossRef]

- Costa; F.; Alvarez; L.; Lozano; A. I.; Blanco, F.; Oller, J. C.; Muñoz, A.; Souza Barbosa, A.; Bettega, M. H. F.; Ferreira da Silva, F.; Limão-Vieira, P.; White; R. D.; Brunger, M. J.; García, G. Experimental and theoretical analysis for total electron scattering cross sections of benzene. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 084310.

- Jones, D. B.; Bellm, S. M.; Limão-Vieira, P.; Brunger, M. J. Low–energy electron scattering from pyrimidine: Similarities and differences with benzene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2012, 535, 30–34. [CrossRef]

| Energy [eV] | C4H4N2 | 2-C4H3ClN2 | 5-C4H3ClN2 | 2-C4H3ClN2 | 5-C4H3ClN2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.804 | 0.00000 | ||||

| 9.865 | 0.00000 | ||||

| 9.900 | 0.00934 | 0.00355 | |||

| 9.911 | 0.00000 | ||||

| 10.00 | 0.01920 | 0.00883 | 0.01366 | ||

| 10.04 | 0.00000 | ||||

| 10.12 | 0.00000 | ||||

| 11 | 0.1877 | 0.1697 | 0.1930 | 0.2058 | 0.1899 |

| 12 | 0.5286 | 0.4370 | 0.4573 | 0.5588 | 0.5013 |

| 13 | 0.9283 | 0.8912 | 0.8583 | 1.052 | 0.9616 |

| 14 | 1.319 | 1.368 | 1.318 | 1.540 | 1.437 |

| 15 | 1.744 | 1.844 | 1.775 | 2.050 | 1.904 |

| 16 | 2.244 | 2.402 | 2.342 | 2.628 | 2.508 |

| 17 | 2.753 | 2.981 | 2.924 | 3.223 | 3.099 |

| 18 | 3.267 | 3.547 | 3.485 | 3.798 | 3.668 |

| 19 | 3.785 | 4.131 | 4.053 | 4.393 | 4.244 |

| 20 | 4.283 | 4.692 | 4.610 | 4.959 | 4.805 |

| 25 | 6.380 | 7.055 | 6.960 | 7.341 | 7.168 |

| 30 | 7.992 | 8.874 | 8.775 | 9.175 | 8.995 |

| 35 | 9.199 | 10.26 | 10.15 | 10.57 | 10.39 |

| 40 | 10.11 | 11.31 | 11.21 | 11.63 | 11.45 |

| 45 | 10.77 | 12.10 | 11.99 | 12.43 | 12.24 |

| 50 | 11.25 | 12.68 | 12.57 | 13.01 | 12.82 |

| 55 | 11.59 | 13.11 | 12.99 | 13.43 | 13.24 |

| 60 | 11.82 | 13.40 | 13.29 | 13.73 | 13.55 |

| 65 | 11.97 | 13.61 | 13.50 | 13.94 | 13.75 |

| 70 | 12.06 | 13.74 | 13.63 | 14.07 | 13.88 |

| 75 | 12.10 | 13.81 | 13.70 | 14.14 | 13.96 |

| 80 | 12.10 | 13.84 | 13.73 | 14.17 | 13.99 |

| 85 | 12.08 | 13.83 | 13.72 | 14.16 | 13.98 |

| 90 | 12.02 | 13.79 | 13.69 | 14.12 | 13.94 |

| 95 | 11.95 | 13.73 | 13.63 | 14.06 | 13.89 |

| 100 | 11.87 | 13.65 | 13.55 | 13.98 | 13.81 |

| 110 | 11.67 | 13.46 | 13.36 | 13.79 | 13.63 |

| 125 | 11.33 | 13.11 | 13.01 | 13.44 | 13.28 |

| 150 | 10.72 | 12.46 | 12.37 | 12.79 | 12.64 |

| 175 | 10.13 | 11.80 | 11.72 | 12.13 | 12.00 |

| 200 | 9.568 | 11.18 | 11.10 | 11.51 | 11.38 |

| 250 | 8.594 | 10.09 | 10.01 | 10.40 | 10.29 |

| 300 | 7.789 | 9.171 | 9.105 | 9.477 | 9.374 |

| 350 | 7.122 | 8.407 | 8.347 | 8.701 | 8.608 |

| 400 | 6.564 | 7.763 | 7.708 | 8.046 | 7.960 |

| 450 | 6.090 | 7.214 | 7.163 | 7.487 | 7.407 |

| 500 | 5.683 | 6.741 | 6.694 | 7.004 | 6.930 |

| 600 | 5.020 | 5.968 | 5.926 | 6.213 | 6.148 |

| 700 | 4.503 | 5.362 | 5.325 | 5.592 | 5.534 |

| 800 | 4.089 | 4.874 | 4.841 | 5.091 | 5.039 |

| 900 | 3.748 | 4.473 | 4.443 | 4.678 | 4.630 |

| 1000 | 3.463 | 4.137 | 4.109 | 4.331 | 4.287 |

| 1500 | 2.530 | 3.031 | 3.011 | 3.186 | 3.155 |

| 2000 | 2.009 | 2.411 | 2.395 | 2.542 | 2.516 |

| 2500 | 1.674 | 2.011 | 1.998 | 2.124 | 2.104 |

| 3000 | 1.440 | 1.731 | 1.720 | 1.831 | 1.813 |

| 3500 | 1.266 | 1.523 | 1.513 | 1.612 | 1.597 |

| 4000 | 1.131 | 1.361 | 1.353 | 1.443 | 1.429 |

| 4500 | 1.024 | 1.233 | 1.225 | 1.307 | 1.295 |

| 5000 | 0.9359 | 1.127 | 1.120 | 1.196 | 1.185 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).