1. Introduction

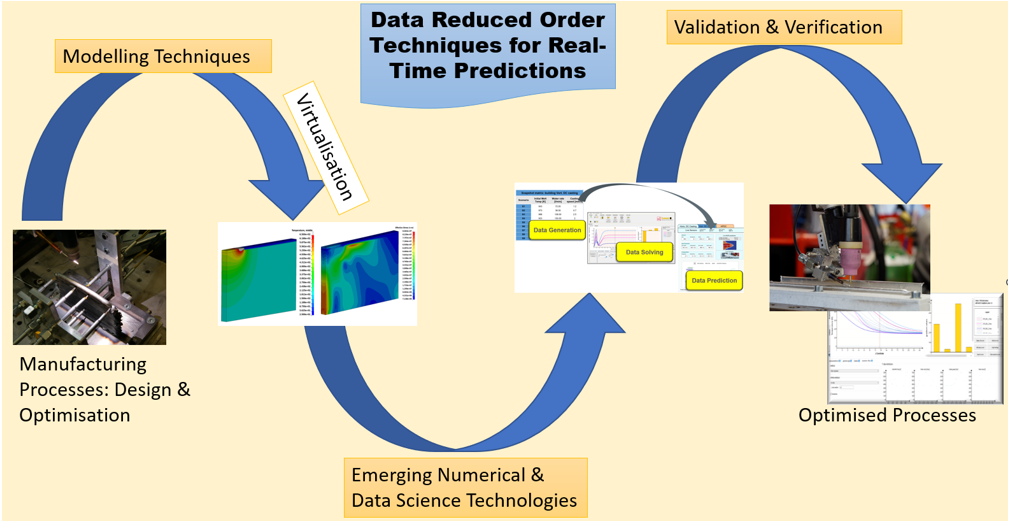

Digital twin and shadowing concepts enable material-based industries to evaluate the performance of their processes and products quickly and efficiently [

1]. They help reduce costs and improve the entire production chain by offering prediction and correction routines that optimize performance [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Real-time modelling and its applications within the digital twin framework for manufacturing processes have been developed to incorporate fast and reliable prediction techniques within the industrial digitalization framework [

8,

9,

10]. The use of data-driven techniques, along with smart handling, training, and learning of manufacturing data, is a new trend in the design and optimization of industrial production chains [

11]. Although many advanced numerical simulation technologies have been employed to design and optimize material processes within the manufacturing chain (e.g., offline optimizations), the digitalization drive has generated a strong demand for quick and real-time predictive models where live data can be interpreted and used as training data for fast responsive models [

12,

13].

With the advancement of data science schemes, including smart handling and learning techniques like machine learning technologies, industrial digitalization concepts have driven the development of greener and more efficient manufacturing processes. Digital twin and shadowing schemes, which create a digital counterpart for real-time monitoring, controlling, and optimization, are based on process data handling, and data learning. Model order reduction (MOR) techniques are an integral part of these schemes, where the combination of data-driven reduced models and ML modules creates fast and accurate predictive models. MOR technology trends have promoted many new ideas for process optimization and monitoring, leading to more efficient processes and achieving cheaper, higher-quality productions and parts [

14,

15,

16,

17].

One of the main challenges in applying reduced predictive models to industrial processes is the creation and verification of these models [

18]. Numerous data-driven and hybrid techniques are available for reduced modelling in general engineering applications, but their suitability, accuracy, and efficiency for steady-state and time-transient process modelling have not been fully verified [

19]. Some techniques have specific features that limit their applicability to general process modelling (e.g., rate dependency), while others may not be accurate enough for modelling changing conditions during real-world industrial processes [

20]. This paper briefly summarizes the performance of available MOR techniques for manufacturing processes, scrutinizing issues of accuracy, speed, and reliability of model predictions. As case studies, the application of MOR techniques for extrusion and AM processes are concisely presented, where time-transient temperature histories are predicted using tailored MOR techniques.

2. MOR Techniques for Material Processes

There has been much debate about the application of MOR and hybrid modeling for manufacturing processes and their associated sub-processes (e.g., cooling, heating) to establish the best modeling schemes. Various reduced modeling schemes have been developed for general engineering applications, employing different data science methods to reduce the dimensionality of complex simulations. Methods such as eigen-base, two-stage reduction, regression (both conventional and symbolic), support vector machines, clustering, and other popular data science techniques have been used to achieve this dimensionality reduction in engineering simulations.

Other techniques, such as proper generalized decomposition (PGD), Krylov subspace methods (KSMs), balanced truncation (BT), and reduced basis methods (RBM), have also been employed to create lower-dimensional representations of processes. In particular, the application of PGD methods for processes with a large number of input parameters has been investigated due to their efficient separation of variables. Additionally, KSM reduction techniques (e.g., PRIMA, SPRIM) can project data related to complex processes with many parameters onto a lower-dimensional space with reduced computational demands [

21]. RBM and BT techniques can also be employed to reduce the data dimensionality of engineering processes by truncation and the utilization of basis functions corresponding to the original data structure.

2.1. Eigen-Base Model Builders

Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD), Singular Value Decomposition (SVD), and Proper Generalized Decomposition (PGD) are among the most popular eigen-based reduced modeling techniques for process simulations [

16,

17]. These techniques can be defined as decomposition schemes (both spatial and temporal) where algebraic approximations of system responses are created to allow for fast reconstruction of system characteristics. In eigen-based techniques, dimensionality reduction is achieved by approximating essential data information using mathematical eigenvalue analyses. The initial data for these reduced models can originate from experimental work, verified numerical simulations, hybrid analytical-simulations, and/or mined data, where variations of predefined system parameters are considered to fill the so-called snapshot matrix. For POD and SVD, the factorization of the system response can be mathematically expressed as [

19]:

where

is the eigenvector of

A, the decomposed matrices

and

are orthogonal matrices related to spatial and temporal decomposition, respectively, and

is the eigenvalue matrix. These reduced model builders are popular for manufacturing processes because they can easily characterize processes using an appropriate number of data eigenmodes.

For multi-physical material processes involving thermal and mechanical evolutions (e.g., heating, cooling, warping), generating reduced versions of the full process models is more challenging due to the transient nature of these processes. The integration of these reduced models into digital twin or shadow frameworks is also limited by the high volume of data required for modeling. Therefore, proper data modeling techniques that employ a balanced combination of MOR and ML techniques are essential to achieve accurate real-time predictions. If the same mathematical basis as in Equation (1) is employed for predicting temperature (and stress) responses during a material process, it can be written as [

11]:

where

are temperatures and stresses at process time

t. Hence, the stress, deformation, and temperature at any nodal point can be predicted during the material process (e.g., AM, extrusion) using a proper data interpolation scheme.

2.2. Kriging and Regression Model Builders

The combination of two-stage Kriging and principal component analysis (PCA) model building schemes are among the most powerful dimensional-reduction techniques. These methods maintain primary data characteristics and their dimensions while eliminating less important dimensions using correlation methods. In these techniques, the spatial correlations between sample data are used to create a new coordinate system where maximum data variances are aligned. Although these techniques are popular for reduced model building in manufacturing processes, their rate-dependencies limit their applicability for processes with rapidly changing parameters (e.g., high gradient time-transient data).

Conventional and symbolic regression techniques are among the oldest reduction methods, where data variables can be sorted based on their impacts. Variables can be ranked by their importance indexes, allowing less important data to be ignored to reduce data dimensions. Symbolic regression (SR) and genetic algorithm symbolic regression (GASR) are more sophisticated regression techniques, where regression analysis is performed within a multi-dimensional search space for mathematical expressions and operators to find the most suitable model. Although these regression techniques have been extensively applied to reduce the data dimensionality of steady-state processes, their applications for transient processes are limited due to higher error margins for data with high gradient changes.

2.3. Clustering and SVM Model Builders

Clustering-based reduced model building is a well-known technique among various data science methods, involving the grouping and clustering of data points with common features. It can be defined as an unsupervised learning scheme used to identify patterns in available data for better insights. Recently developed clustering techniques include density-based spatial clustering, expectation-maximization clustering, mean-shift clustering, K-means clustering, and hierarchical clustering. For applications in industrial process simulations, clustering techniques, along with interpolation methods (e.g., Kriging, radial basis functions, inverse distance), can be employed to predict real-time responses.

Support vector machine (SVM) is another ML scheme (supervised learning) that can represent spatio-temporal data for both steady-state and transient processes, mapping data into different categories based on existing gaps in time and coordinate space. Various kernel functions, including linear, polynomial, radial basis functions, and Fourier kernel functions, can be used in SVM to classify process-related data. The powerful classification and regression features of SVM can be employed to predict real-time process responses, facilitating the control and optimization of transient industrial processes while avoiding data overfitting.

3. Case Study–Process Applications

The introduction of data-driven and real-time accurate models for industrial processes has begun to transform the control and optimization of these processes. Real-time models for processes like industrial extrusion and AM are rapidly evolving to generate faster and more reliable prediction models. In the case of the extrusion process, the large thermo-mechanical deformation of material requires frequent updates of the material state. For AM processes, with their frequently changing demands due to more complex geometries, innovative power sources, and new materials, the need for fast and accurate models has been emphasized [

22].

Although numerical simulations of these processes using finite element and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) techniques have been extensively used in industries, real-time control and optimization require much faster models. To investigate the application of fast reduced models for extrusion and AM processes, comprehensive frameworks have been established to evaluate the performance of these real-time predictive tools.

3.1. Reduced Models for Extrusion Process

Extrusion processes are adaptable manufacturing methods used to produce various profiles with different shapes, sizes, and complex cross-sections using pre-designed dies. Numerical simulations and fast real-time models can help optimize these processes and provide insights into the large thermo-mechanical deformations of materials during the process. To build accurate and reliable real-time models for these processes, the following steps can be followed:

- ➢

Any real-time data model needs a properly sized initial database that provides enough data points with the right balance of data density within its multi-dimensional search spaces. To generate such a database, parallel numerical simulation and experimental frameworks need to be set up.

- ➢

After conducting limited experimental trials, the data need to be compared to numerical simulation runs that resemble these experiments. Calibrations and further verifications are then performed to confirm the accuracy and reliability of offline numerical simulations of the process.

- ➢

In the next step, the most influential process parameters are defined and selected, and a proper sampling technique (e.g., Sobol, LHS) is employed to form a snapshot matrix.

- ➢

Using the process scenarios in the snapshot matrix, real-time models based on appropriate mathematical and data science schemes are generated. These models need to be agile enough to cover the entire data within the search space (e.g., within the limits of process parameters).

- ➢

To validate the accuracy and reliability of these models, further design of experiments (DOEs) process scenarios are carried out to provide benchmark results for model validations.

- ➢

Model validations are carried out using DOEs data at three levels: normal conditions, near boundary conditions, and extrapolation stages. Data from within, near the limits, and outside of the search space are used to perform the full validation exercise.

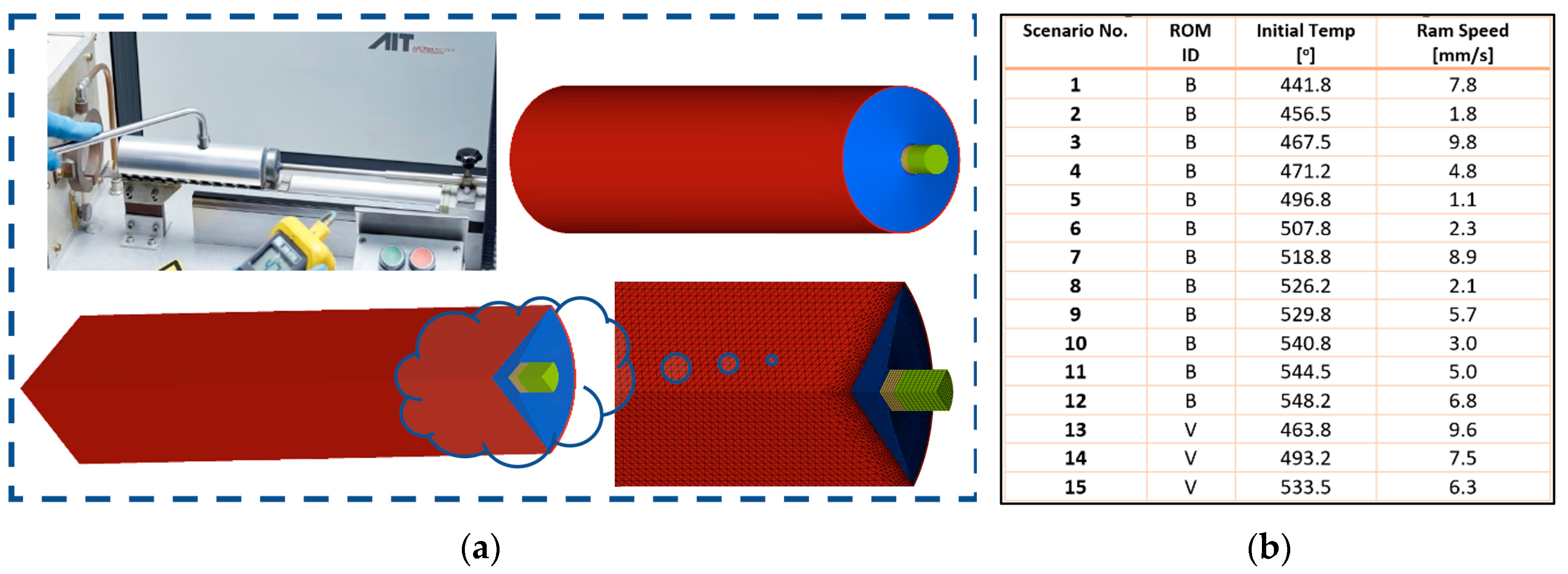

For the numerical simulations of extrusion processes in this research work, the thermo-mechanical solver HyperXtrude (HX) is used, which employs the arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian (ALE) hybrid approach to calculate large material deformations [

23]. Both the ram speed and initial billet temperature are defined as major process parameters, with their variations based on the billet material (aluminum 6060) and the limits of the extrusion machine. These variations are defined as initial billet temperatures ranging from 440°C to 550°C and ram speeds ranging from 1 to 10 mm/s for the cylindrical aluminum billet (with a 50 mm diameter). The numerical domain is discretized using 172,000 volumetric elements, and only a quarter of the model is simulated due to double symmetric conditions.

Figure 1 shows the geometry and the finite element (FE) mesh for the extrusion process, along with the snapshot matrix for the model-building exercise.

3.2. Reduced Models for AM Process

For industrial wire arc AM processes, where the manufacturing of parts evolves over time, accurate and reliable reduced models are required to account for transient changes in material feeds, power, and thermal energy content. Although many different reduction techniques can be tailored and employed for real-time predictions, their generality and accuracy need to be scrutinized. Many of these models are either tailored for smooth data changes or are not suitable for transient data due to rate dependencies [

24].

In the current research, various popular reduced model building techniques were considered for the AM process, where available finite element (FE) and experimental data could be processed to train the model. Following the previous extrusion process application, the procedure for reduced model building for AM processes can be summarized as follows:

- ➢

The initial verification of the FE model for the AM process was carefully conducted using experimental data (with Goldak heat source modeling [

25]).

- ➢

A suitable snapshot matrix was defined to carry out detailed FE simulations with varying input parameters, including initial base temperature, torch power, and deposition speed.

- ➢

The snapshot results are used to create, and train reduced models using different techniques.

- ➢

Further DOE scenarios were performed to create a validation matrix for the models.

- ➢

The performances of various models were investigated through an extensive comparative study between reduced and FE models for DOEs.

- ➢

The results of the comparative study were further post-processed to determine the most suitable techniques for AM reduced models.

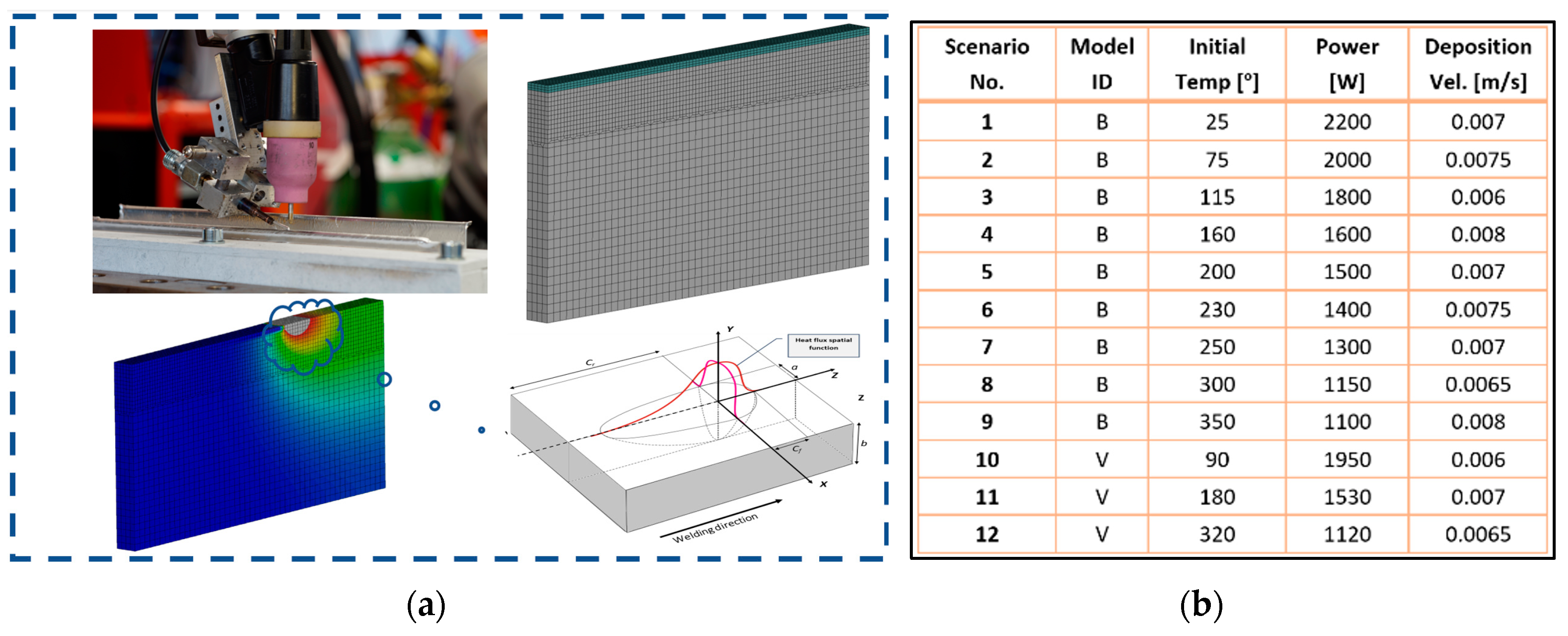

For the AM case study in this research work, a single-layer deposition process on top of a thermally pre-conditioned wall with dimensions of 100 mm x 50 mm x 6 mm was simulated. Aluminum 6061 wires were used for the deposition process, and welding was carried out using inert gas welding. For the initial validations, experimental trials were conducted to observe the thermal evolution and measure the temperature variations at selected locations. To build the reduced models, nine additional process simulation scenarios were performed with varying parameters such as torch power, deposition speed, and initial temperatures.

Figure 2 shows the geometry and the FE mesh for the AM process, along with the snapshot matrix for the model-building exercise.

4. Comparative Study

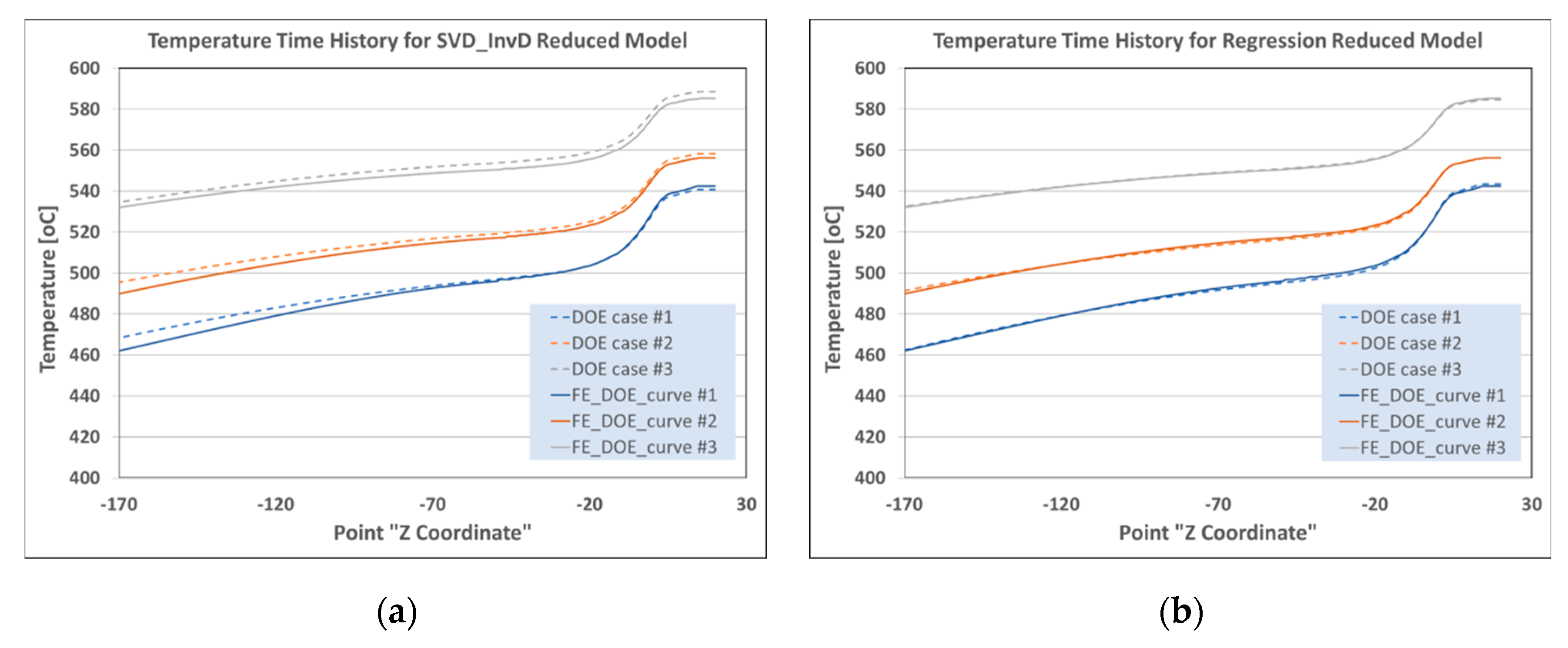

To evaluate the performance of real-time models and compare the outcomes of different reduced model building techniques, comparative studies have been conducted for both industrial case studies. The aim is to investigate the accuracy and reliability of real-time models based on data provided by the verified FE results of DOEs. For the first case study on the extrusion process, popular eigen-based POD techniques and the more general SVD method, along with regression analyses, were employed for the model-building exercise.

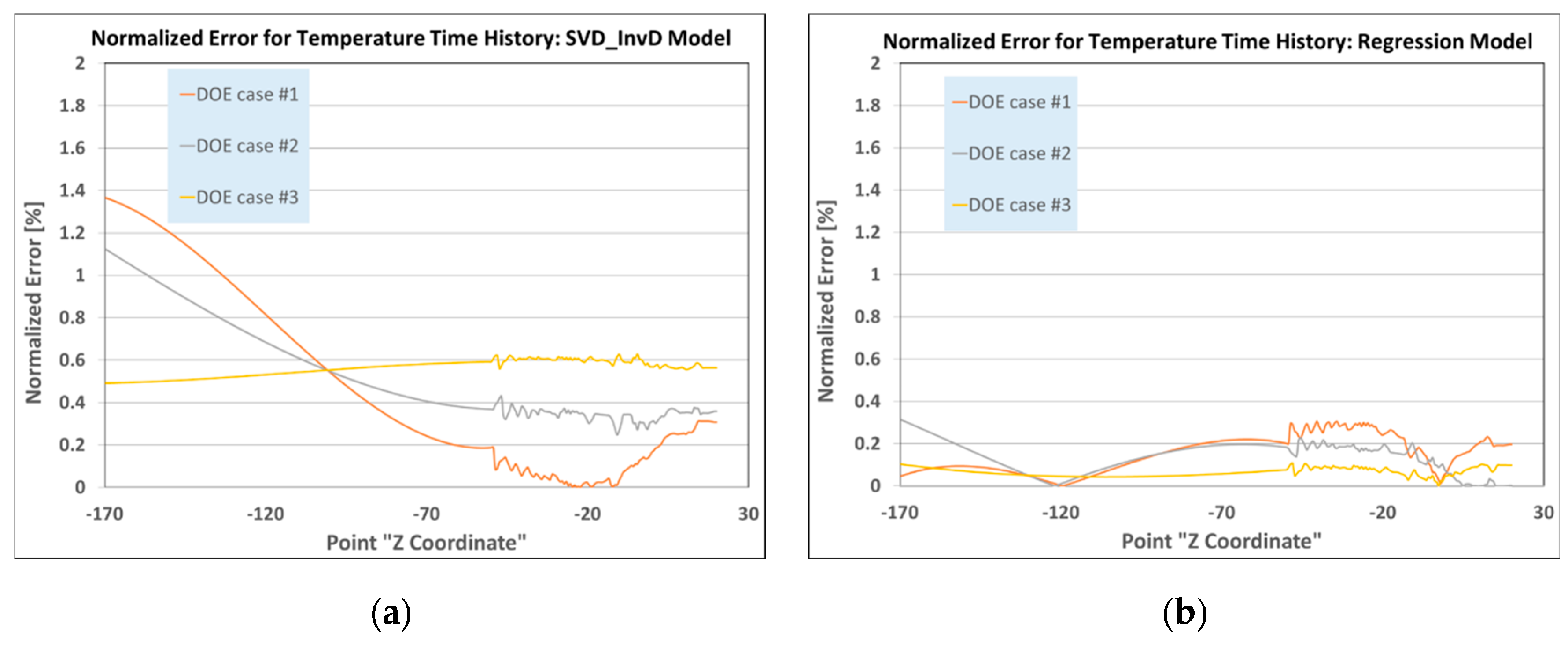

Figure 3 shows the comparisons of temperature time histories for SVD and regression techniques using DOE results. The data weighting feature of the inverse distance (InvD) technique is used for the SVD solver as a data interpolator [

19].

The normalized error graphs for the SVD_InvD and regression techniques are presented in

Figure 4 for all three DOEs. The finite element (FE) results for these three validation scenarios are compared with the results from the real-time models. The normalized error percentages are calculated based on the data model predictions for nodes along the extrusion billet, relative to the FE simulation results. The results indicate that the normalized errors are higher at the billet's ends (i.e., at the initial boundary) and near the die, where significant material deformation occurs. The thermo-mechanical phenomena resulting from the material's large deformation as it passes through the die cause temperature fluctuations in this region, which can pose challenges for the accuracy of the data model predictions.

Similarly, for the real-time models of AM processes, eigen-based and regression solvers were employed to build reduced models to investigate their accuracy and reliability. Although there are no general rules for choosing the best-performing technique for reduced model building, some models perform better in terms of accuracy and reliability for dynamic processes like AM, depending on the nature of the transient data.

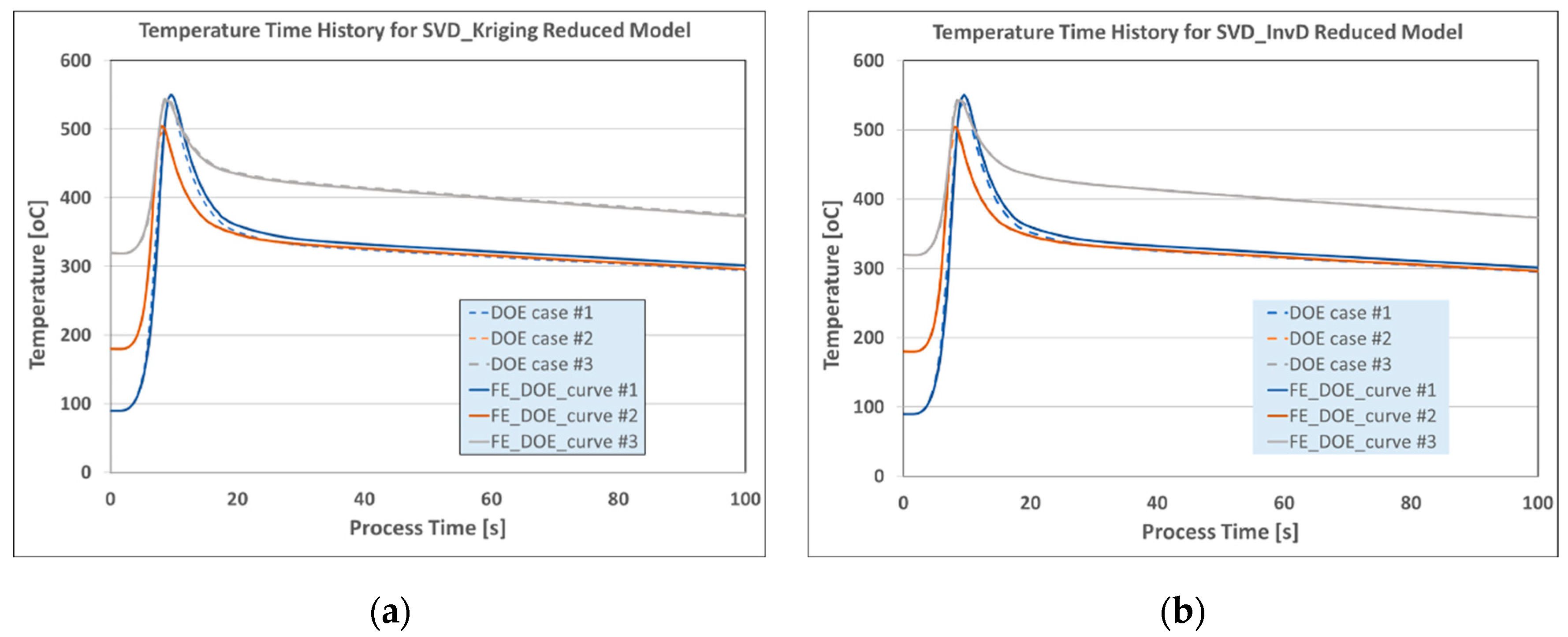

Figure 5 shows the comparisons of temperature time histories for the DOE results and reduced models, using the SVD_Kriging and SVD_InvD (SVD solver with inverse distance data interpolator) techniques for a nodal point on the wall during the AM process.

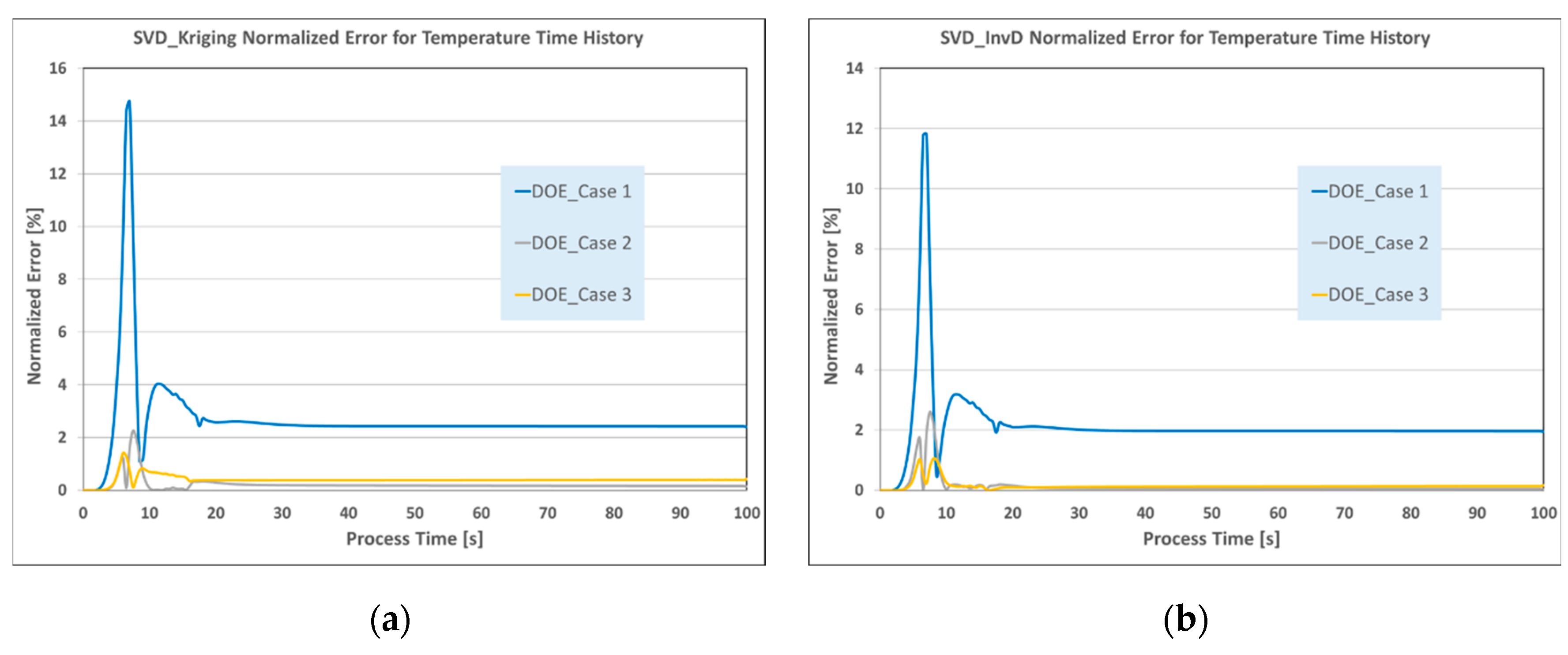

Figure 6 shows the normalized transient error graphs for the same SVD_Kriging and SVD_InvD techniques for all three DOEs.

5. Discussion

Although real-time models can help improve prediction-correction schemes for material processes, there are challenges related to their accuracy, efficiency, and reliability. Material processes are inherently multi-physical, often involving high rates of heating and cooling during production, as well as changes in material state from fluid to solid or vice versa. Therefore, the performance of these real-time models depends on data quality, the quantity of available data, the rate of changes within the data, and the complexity of the system being modeled.

The results presented here show that these models can reasonably predict the transient responses of the AM and extrusion processes. Although the process databases for both AM and extrusion cases are limited in size, the available data have balanced distributions within the multi-dimensional search spaces (e.g., limits of the processing parameters for manufacturing machines). However, as observed from the real-time responses, coping with high heating/cooling rates (e.g., the passage of the torch over a measuring point in the AM process) and fitting into the initial process conditions (e.g., initial temperature) remain challenging tasks for these models.

To investigate the performance of real-time models in predicting high heating/cooling rates and their ability to fit initial process conditions, a further study was conducted to compare the accuracy of different model building techniques.

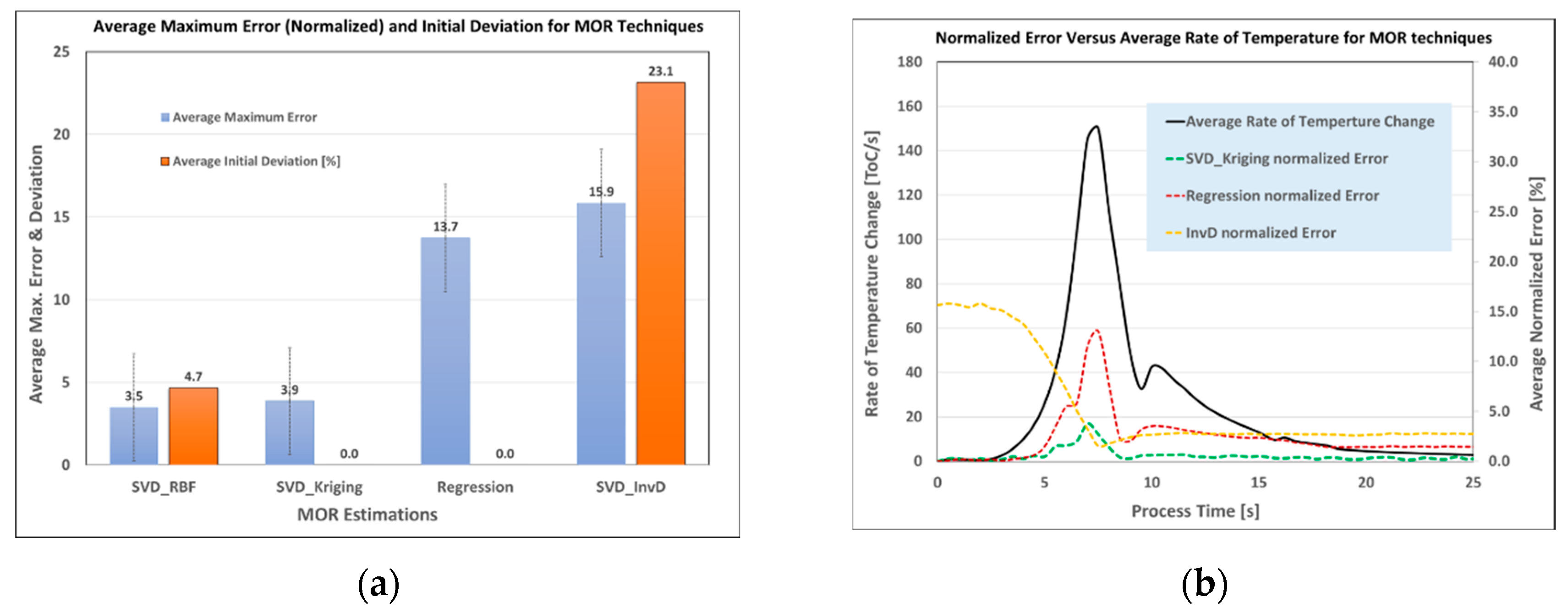

Figure 7a shows the average maximum errors (over three DOEs) and the deviation of initial conditions (in percentages) for four popular model building techniques: SVD_RBF (SVD solver with radial basis function interpolator), SVD_Kriging, SVD-InvD, and regression techniques.

Figure 7b shows the time history of the average normalized errors (over three DOEs) with the calculated rate of temperature changes.

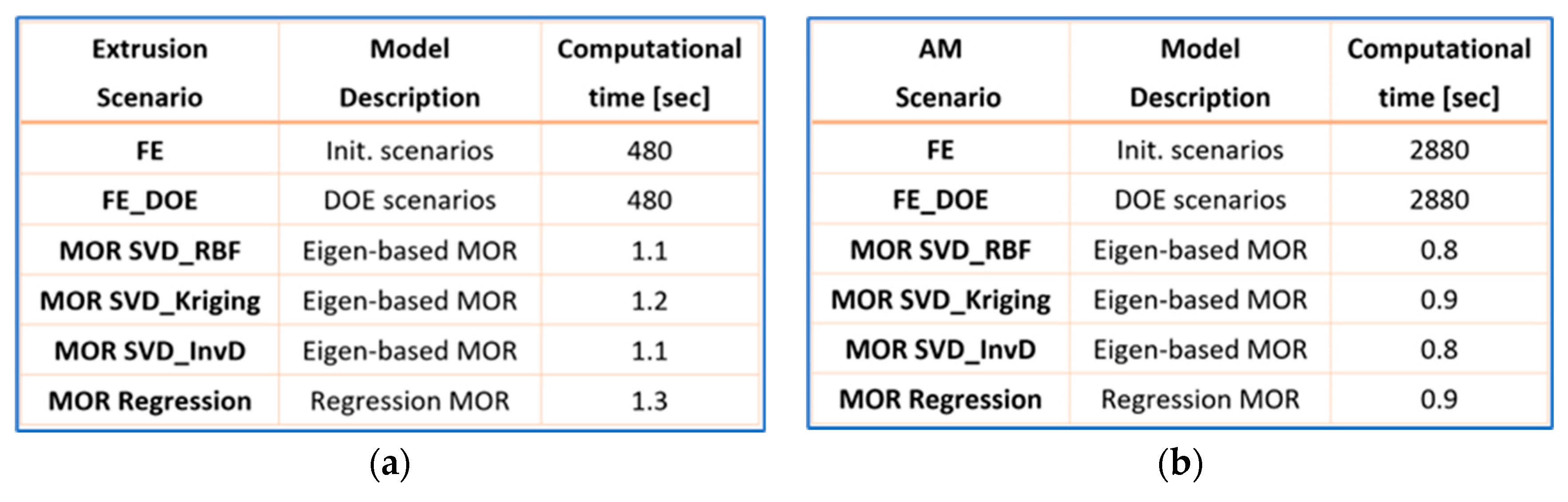

Figure 8 also show the computational time for the FE simulations and real-time models for both extrusion and AM case studies.

As observed from these figures, the real-time models exhibit some degree of temperature rate dependency and deviations from the initial process conditions. However, for both the extrusion and AM processes in this study, the SVD_Kriging and regression techniques demonstrate superior performance in predicting the thermal transient responses.

6. Conclusions

The use of dimensional-reduction techniques and their associated real-time models for material processes like casting, extrusion, and additive manufacturing is becoming increasingly popular and valuable for industrial production. These tools can optimize manufacturing processes, improve product quality, enhance the predictive-corrective power of real-time adjustments, and reduce costs and time by avoiding lengthy trial-and-error loops.

In the first part of the paper, brief descriptions of MOR techniques and their applications for dynamic material processes like extrusion and AM manufacturing were presented, along with a concise elaboration on some data science aspects of these new techniques. In the second part of the paper, real-time model building exercises for practical case studies were explained, and their challenges related to accuracy, heat rate dependency, and thermal initial boundary conditions were examined.

Although the detailed results of the best-performing data “solver-interpolator” combinations are not presented here due to the vast number of these combinations, it has been shown that some well-known solvers (e.g., SVD, regression) can produce reasonably accurate real-time results. Future publications will explore real-time model building exercises for other multi-physical processes, such as casting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. Horr and H. Drexler; methodology, A. M. Horr; software, H. Drexler (numerical simulation), A.M. Horr (data models); validation, H. Drexler, A.M. Horr; formal analysis, H. Drexler, A.M. Horr; investigation, A.M. Horr and H. Drexler; data curation, A.M. Horr; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. Horr; writing—review and editing, H. Drexler, A.M. Horr; visualization, A.M. Horr; supervision, A.M. Horr; funding acquisition, A.M. Horr and H. Drexler. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Austrian Federal Ministry for Climate Action, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology, the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG) and the Austrian Institute of Technology under the UF2023 scheme.

Data Availability Statement

Sharing of data and reduced models generated in this research work may be considered upon request.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank the Austrian Federal Ministry for Climate Action, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology and also the Austrian Institute of Technology (AIT) for the technical/financial support in this research work. Authors would also like to thank Johannes Kronsteiner, from LKR, Austrian Institute of Technology and Andela Babaja, former master student at Technische Universität München for their contributions in this research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ball, P., Badakhshan, E. Sustainable Manufacturing Digital Twins: A Review of Development and Application. In: Scholz, S.G., Howlett, R.J., Setchi, R. (eds) Sustainable Design and Manufacturing. KES-SDM 2021. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, vol 262, 2022, Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Corallo, A.; Del Vecchio, V.; Lezzi, M.; Morciano, P. Shop Floor Digital Twin in Smart Manufacturing: A Systematic Literature Review: Sustainability, 2021, 13, 12987. [CrossRef]

- Thelen, A., Zhang, X., Fink, O. et al. A comprehensive review of digital twin — part 1: modeling and twinning enabling technologies. Struct Multidisc Optim 65, 354, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wynn, M.; Irizar, J. Digital Twin Applications in Manufacturing Industry: A Case Study from a German Multi-National. Future Internet, 2023, 15, 282. [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.B., Mishra, D., Pal, S.K. et al. Digital twin: current scenario and a case study on a manufacturing process. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 107, 3691–3714, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ashtari Talkhestani, Behrang and Weyrich, Michael. "Digital Twin of manufacturing systems: a case study on increasing the efficiency of reconfiguration" at - Automatisierungstechnik, 2020, vol. 68, no. 6, pp. 435-444. [CrossRef]

- Latif, H. , Shao, G. and Starly, B. A Case Study of Digital Twin for a Manufacturing Process Involving Human Interactions, Proceedings of 2020 Winter Simulation Conference, Orlando, FL, US, 2020, [online]. https://tsapps.nist.gov/publication/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=930232, (Accessed November 18, 2024).

- Mahfoud, H., Moutaoukil, O., Toum Benchekroun, M., Latif, A. Real-Time Predictive Maintenance-Based Process Parameters: Towards an Industrial Sustainability Improvement. In: Ezziyyani, M., Kacprzyk, J., Balas, V.E. (eds) International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems for Sustainable Development (AI2SD'2023). AI2SD, 2023. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 931. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K., Li, Y., Liu, C. et al. Advanced Data Collection and Analysis in Data-Driven Manufacturing Process. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 33, 43, 2020. [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, P., Leahy, K., Bruton, K. et al. Big data in manufacturing: a systematic mapping study. Journal of Big Data 2, 20 2015. [CrossRef]

- Horr, A.M. Real-Time Modeling for Design and Control of Material Additive Manufacturing Processes. Metals 2024, 14, 1273. [CrossRef]

- Horr, A. M. Optimization of Manufacturing Processes Using ML-Assisted Hybrid Technique, J. of Manuf. Letters, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Horr A.M., Notes on New Physical & Hybrid Modelling Trends for Material Process Simulations; J. of Phy. conference Series, 2020, Vol. 1603, 012008. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Sikander, A. Review and analysis of model order reduction techniques for high-dimensional complex systems. Microsyst Technol 30, 1177–1190, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Favoretto B., de Hillerin C. A., Bettinotti O., Oancea V., Barbarulo A., Reduced order modeling via PGD for highly transient thermal evolutions in additive manufacturing, Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 349, 405-430, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Quaranta G. Efficient simulation tools for real-time monitoring and control using model order reduction and data-driven techniques. Tesi doctoral, UPC, Departament d'Enginyeria Civil Ambiental, 2019, Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2117/168567.

- Kerschen, G., Golinval, J., VAKAKIS, A.F. et al. The Method of Proper Orthogonal Decomposition for Dynamical Characterization and Order Reduction of Mechanical Systems: An Overview. Nonlinear Dyn 41, 147–169, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Horr A.M., Gómez Vázquez R., and Blacher D. Data Models for Casting Processes – Performances, Validations and Challenges, 2024, IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 1315 012001. [CrossRef]

- Brunton, S. L., Kutz J. N. Data Driven Science & Engineering - Machine Learning, Dynamical Systems, and Control, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Qin J., Hu F., Liu Y., Witherell P., Wang C. L., Rosen D. W., Simpson T. W., Lu Y., Tang Q., Research and application of machine learning for additive manufacturing, Additive Manufacturing, 52, 102691, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Antoulas, A.C., Ionutiu R., Martins N., Maten E. Jan W. ter, Mohaghegh K., Pulch R., Rommes J., Saadvandi M., Striebel M. Model Order Reduction: Methods, Concepts and Properties. In: Günther, M. (eds) Coupled Multiscale Simulation and Optimization in Nanoelectronics. Mathematics in Industry, 2015, vol 21. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Brötz, S.; Horr, A. M. Framework for progressive adaption of FE mesh to simulate generative manufacturing processes. Manuf. Lett., 2020, 24, 52–55. [CrossRef]

- Hoque S.E., Hovden S., Culic S., Nietsch J.A., Kronsteiner J., and Horwatitsch D., Modeling friction in hyperxtrude for hot forward extrusion simulation of AA6060 and AA6082 alloys, 25th International Conference on Material Forming (ESAFORM 2022), 2022, Key Engineering Materials, 926:416–425, 8. [CrossRef]

- Wang C., Tan X.P., Tor S.B., Lim C.S., Machine learning in additive manufacturing: State-of-the-art and perspectives, Additive Manufacturing, Volume 36, ,101538, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Goldak, J., Chakravarti, A. and Bibby, M., A New Finite Element Model for Welding Heat Sources, Metallurgical Transactions B, 15B, 299-305, 1984. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).