1. Introduction

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is an indole homone secreted during the dark hours at night by the vertebrate pineal gland. Tryptophan serves as the precursor for melatonin biosynthesis and is taken up from the circulation and then converted into serotonin. Then, serotonin is converted into N-acetylserotonin by the enzyme arylalkylamine-N-acetyl transferase (AANAT) while N-acetylserotonin is metabolized into melatonin by the enzyme hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase (HIOMT). It has been demonstrated that melatonin is produced by many organs other than the pineal gland[1]. Melatonin not only can maintain circadian rhythms and prevent obesity, neurodegenerative diseases and viral infections, but also impact the gut microbiome and gut health [2,3]. Recent studies have found that the intestine, a vital melatonin repository, can synthesize and secret a large amount of melatonin[4]. In the intestine, melatonin is essential in maintaining intestinal microbial homeostasis, intestinal mucosal immunity, and epithelial cell metabolism [2]. The abnormal increase in GCs will also lead to a decrease in melatonin, further disrupting the biological clock in mice [5]. Moreover, studies in humans and mice showed that sleep deprivation leads to decreased intestinal melatonin, increased intestinal GCs, damaged intestinal barrier and microbiome dysbiosis [6,7,8].

GCs are among variety of endogenous compounds that have been suggested to influence melatonin production in various vertebrate species [9,10,11]. Furthermore, studies have shown that melatonin synthesis can be influenced by GCs, as exemplified by models of stress and elevated concentrations of GCs [5,12]. However, the effect of chronic exposure to Dex on melatonin secretion in goats haven’t been revealled.

GCs directly regulate the circadian clock. All animals have a physiological mechanism called the "biological clock," a 24-hour cycle rhythm from day to night. The metabolic activities of life have their biological rhythms, such as hormone secretion, nutrient absorption and metabolism, gene transcription and so on [13]. At the cellular level, mammals' circadian clock involves two transcriptional feedback loops that work seamlessly by positively or negatively regulating the expression of circadian clock components. This feedback loop is composed of periods (Per1, Per2, and Per3) and cryptochromes (cry1 and 2) and circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (Clock) / brain and muscle ARNT-like (BMAL1). The biological clock plays an essential role in maintaining the normal physiological function of the intestine. The critical clock gene BAML1 can regulate the regeneration of intestine epithelial cells by affecting cytokines, cell cycle and cell proliferation [14]. Deleting the gene Per2 led to decreased expression of intestinal tight junction proteins and increased intestinal permeability in mice [15]. It is worth studying whether chronic exposure to Dex influence the biological clock in goats, which may influence intestinal function. Therefore, this experiment focuses on studying the effects of chronic exposure to Dex on the expression of circadian rhythm of melatonin secretion and clock genes, and intestine barrier function in goats.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Nanjing Agricultural University. The project number is 31972638. The sampling procedures according to the “Guidelines on Ethical Treatment of Experimental Animals” (2006) No.398 set by the Ministry of Science and Technology, China.

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

In brief, ten healthy male goats (25 ± 1kg) fitted with ruminal cannulas were randomly allocated to two groups. The animals were housed in individual pens with free access to water. The goats were fed twice daily (8:00 am and 6:00 pm) at Nanjing Agriculture University (Nanjing, China), from October to December. The control (Con) group was injected with saline, and the treatment group (Dex) was intramuscularly injected with 0.2 mg/kg Dex before morning feeding for 21 days.All the animals were clinically healthy with no evidence of disease and free from internal and external parasites. Their health status was evaluated based on rectal temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, appetite, fecal consistency, and hematologic profile. All experiments were conducted under natural light. All goats were fed with forage–based diets (Alfalfa hay – Medicago sativa L.) and 250g/animal of concentrate mixture (oats 12%, faba bean 15%, barley 25%, pea 10%, sugar beet pulp 20%, molasses 5%, and mineral and vitamin supplements 3%) provide twice a day. Polyethylene catheters were aseptically inserted into the external jugular vein of each goat on the day before the experiment. Blood samples were collected at 4 h intervals over a 24 h period (starting at 04:00 h on day 20 and finishing at 4:00 h on day 21 ) into PAX gene Blood RNA Tube (Qiagen) and stored at -80°C until processing.

On day 21, after an overnight fast, all goats were weighed and killed by injections of xylazine (0.5 mg/kg of body weight; Xylosol; Ogris Pharme, Wels, Austria) and pentobarbital (50 mg/kg body weight; Release; WDT, Garbsen, Germany). Immediately after slaughter, the colon, and cecum were collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen. All the samples were stored at -80 °C for subsequent studies.

2.2. Measurement of Plasma And Colon Melatonin And Plasma Cortisol Level

According to the manufacturer's protocol, plasma melatonin levels were detected using a melatonin ELISA kit (ENZ107 KIT150-0001, Enzo Lifesciences, USA). The colon contents were mixed with 500μL alcohol and centrifuged to collect the supernatant for melatonin detection. The assay sensitivity, range, and intra-assay coefficient of variation were 0.08 pg/mL, 1–162 pg/mL, and <15%, respectively. All samples were tested twice and presented on average. Plasma cortisol was determined using an RIA cortisol kit (Beijing North Institute of Biological Tec.), following the manufacturer's instructions. The sensitivity of the assay was 1 ng/mL. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 7.0%, and all samples were measured in the same assay to avoid interassay variability.

2.3. Assay of Arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT)

Colonic epithelial tissue and pineal gland tissue were collected and weighed (9 g/sample), respectively. The samples were homogenized in the designed buffer provided in AANTA ELISA KIT (Shanghai GuYan Industrial Co., Ltd) and subjected to extract protein. The melatonin synthase enzyme content was measured according to the kit's instructions.

2.4. Assay of Malondialdehyde and Glutathione content

Blood samples were collected and stored at −20 °C for further enzyme activity analysis. Malondialdehyde (MDA) and Glutathione (GSH) content were measured using the MDA and GSH ELISA kits (Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology Co., Ltd., respectively), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.5. RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and real-time PCR

Total RNA was purified directly from whole blood samples collected from goats, using a PAX Gene Blood RNA kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions and resuspended in 80 ml of Elution Buffer. mRNA was then reverse-transcribed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two microliters of diluted cDNA (1:40, v/v) were used for real-time PCR, performed in an Mx3000P (Stratagene, USA). GAPDH was chosen as the reference gene. The method of 2

-△△Ct was used to analyze the real-time PCR results, and all the primers listed in

Table 1 were synthesized by Tsingke Company (Nanjing, China).

2.6. Assay of DAO and LPS

The concentration of DAO was detected by Micro DAO (Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology Co., Ltd). The operation process was carried out in strict accordance with the instructions. The concentration of LPS was detected by Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) ELISA Kit (Cloud-Clone Corp., formerly Uscn Life Science Inc.). The minimum detectable dose of sensitivity is less than or equal to 0.19 ng/ml. The operation process was carried out following the instructions strictly.

2.7. Western blotting analysis

Thirty micrograms of protein extracted from each sample were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio Trace; Pall Corp., New York, NY, USA). After transfer, membranes were blocked for 2 h at room temperature in blocking buffer and then incubated with the following primary antibodies: rabbit-anti-GR (1:1000; DF4994; Protech, Cambridge, UK), CLOCK (1:1000; ab65033; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), BMAL1 (1:1000; ab228594; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-Tubulin-α (1:10,000; BS1699; Bioworld) overnight at 4°C. After washing with 1x PBS, the membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit HRP conjugated IgG (1:10,000; Bioworld) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the blot was visualized by an imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and band intensity was analyzed by Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The mRNA levels of clock-related genes, protein expression of GR, CLOCK and BMAL1, melatonin, cortisol, DAO, LPS, GSH and MDA contents were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) with IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software (United States) to test the statistical significance of the differences among the six daily time points and confirm the daily variation (P ≤ 0.05), as the premise of cosinor analysis. To determine the circadian rhythmicity of each clockrelated gene profile, the mRNA levels of clock-related genes were analyzed separately using MATLAB 7.0 (MathWorks Inc., USA) based on unimodal cosinor regression [y = A + (B × cos (2π(x − C)/ 24))]. A, B and C represent the mesor, amplitude and acrophase, respectively. The results of regression analysis were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05, which was calculated using the number of samples, R2 values and the number of predictors (mesor, amplitude and acrophase). Differences of the mesor, amplitude and acrophase between Con and Dex group were tested by one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test, considering P ≤ 0.05 to be significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of chronic Dex Exposure on the Concentrations of Melatonin and Cortisol in Goats

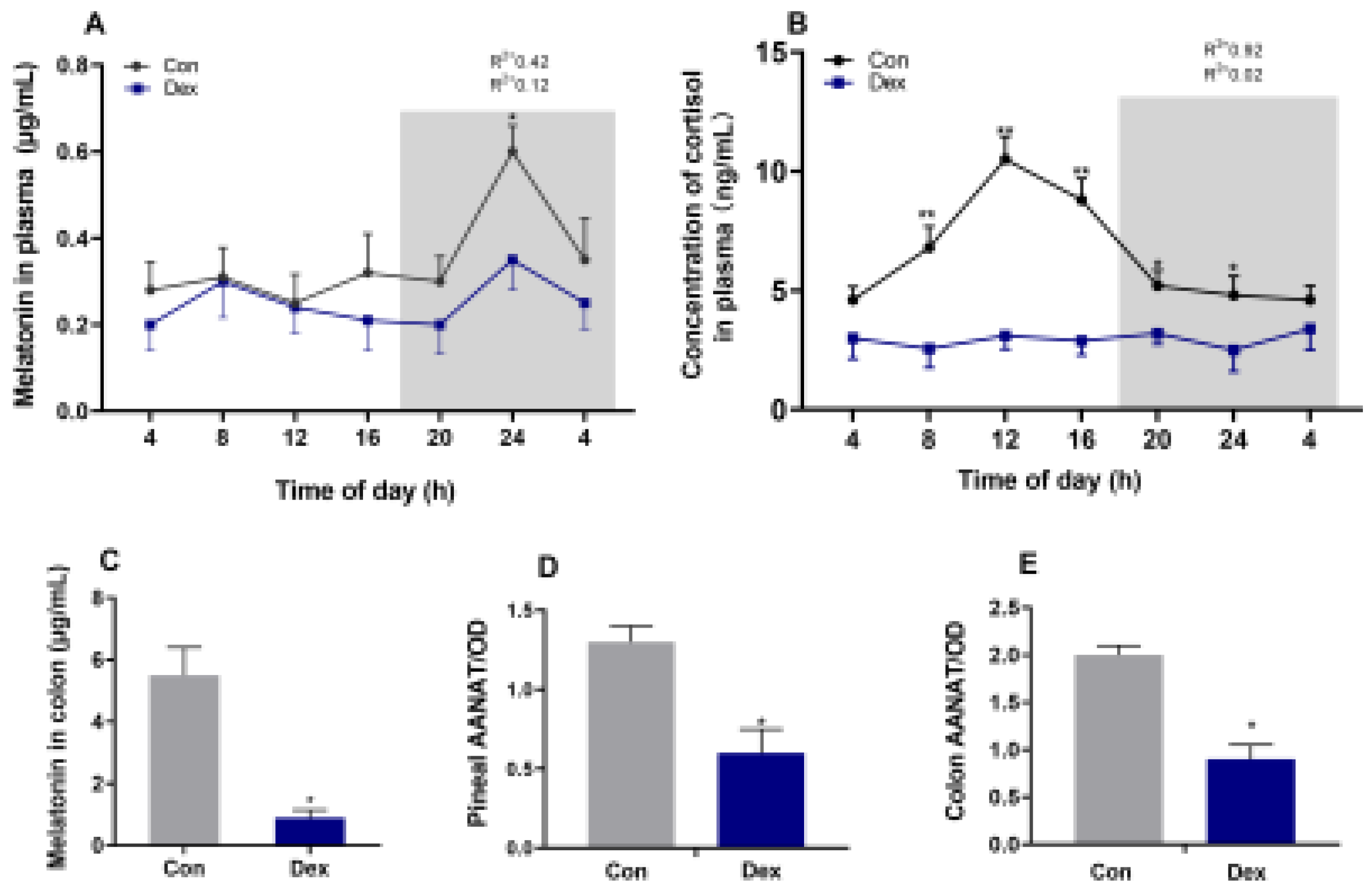

The levels of melatonin (

Figure 1A) and corticosterone (

Figure 1B) in the control group showed changes in diurnal patterns (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA), which was disturbed in Dex group. The results of the analysis of colon contents indicated that Dex treatment resulted in a decrease of melatonin (P<0.05) in the colon compared with the control group on day 21 (

Figure 1C). Meanwhile, a significant reduction (P<0.05) in AANAT, a key enzyme in melatonin production, was observed in the pineal gland and colon tissue samples (

Figure 1D,E). The mesors of cortisol and melatonin level were significantly down-regulated (P < 0.05) by Dex injection, and the amplitude of melatonin level was decreased by Dex (P < 0.05) (

Table 2).

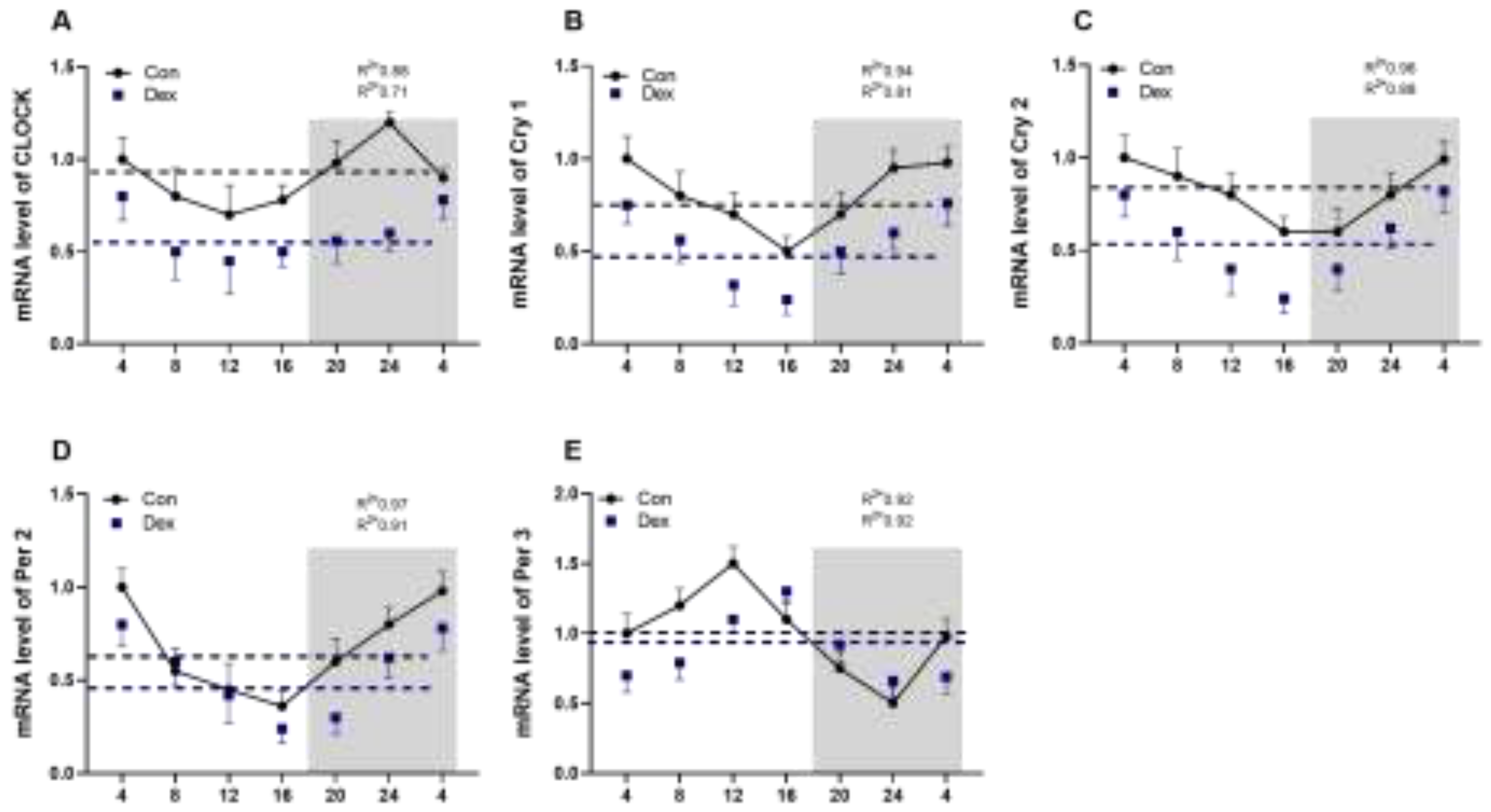

3.2. Effect of Chronic Dex Exposure On The Circadian Rhythm Of Clock Genes In Plasma

Five clock genes were detected in plasma (

Figure 2A-E) in gene expression and region-specific rhythmic patterns. In Con group, all the five tested genes showed circadian rhythms, but the circadian rhythms of Clock, Cry1, Cry2 and Per2 were abolished or blunted by the Dex (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Dex significantly reduced the mesor of mRNA of Clock, Cry1, Cry2, Per2 (

Table 3). In

Figure 2E, the peak of mRNA of Per3 during the day was delayed by four hours in Dex group. In

Table 3, the acrophase of mRNA of Cry2 was decreased by Dex, but acrophase of mRNA of Per2 was increased by Dex (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

Figure 2.

Effect of chronic Dex exposure on the circadian rhythm parameters of clock genes in goats plasma. (A) Clock genes; (B) Cry1 gene; (C) Cry2 gene; (D) Per2 gene; (E) Per3 gene. The data markers in the graphs indicate the clock gene mRNA expression levels, and the results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. The curves represent the 24-h period determined by cosinor analysis. n = 5 goats per time point. Data from CT2 are double-plotted. R2 values represent the degree of fitting. Values are mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared with control.

Figure 2.

Effect of chronic Dex exposure on the circadian rhythm parameters of clock genes in goats plasma. (A) Clock genes; (B) Cry1 gene; (C) Cry2 gene; (D) Per2 gene; (E) Per3 gene. The data markers in the graphs indicate the clock gene mRNA expression levels, and the results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. The curves represent the 24-h period determined by cosinor analysis. n = 5 goats per time point. Data from CT2 are double-plotted. R2 values represent the degree of fitting. Values are mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared with control.

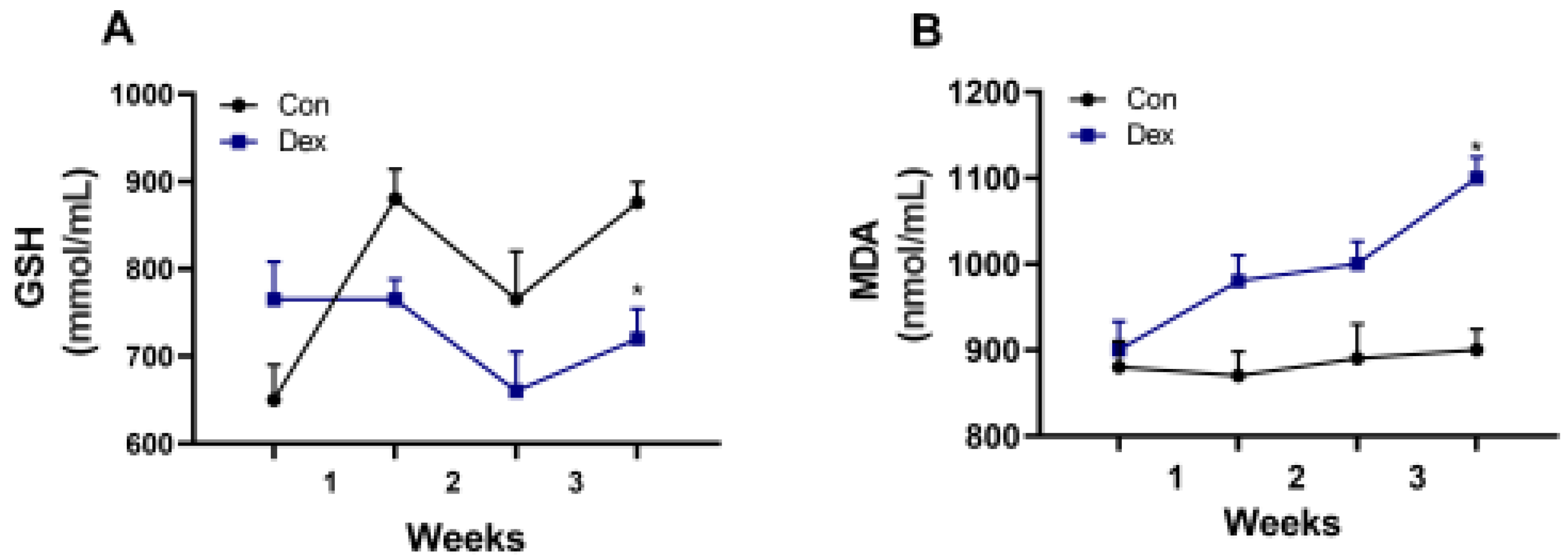

Figure 3.

Effect of chronic Dex exposure on the concentration of GSH and MDA in plasma. (A) GSH content; (B) MDA content. The results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. n = 5 goats, and values are mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared with control.

Figure 3.

Effect of chronic Dex exposure on the concentration of GSH and MDA in plasma. (A) GSH content; (B) MDA content. The results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. n = 5 goats, and values are mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, compared with control.

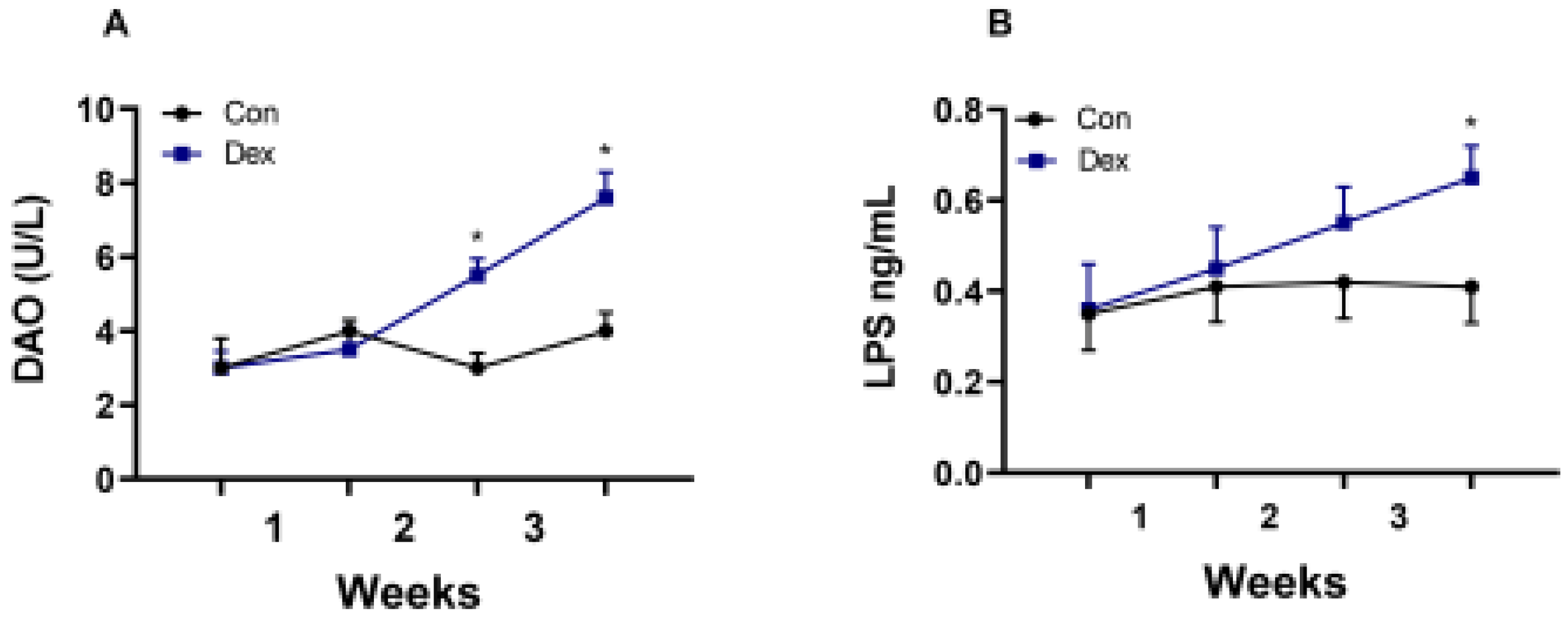

3.4. Effect of Chronic Dex Exposure On Intestinal Barrier Function Indexes (DAO and LPS)

Results showed that DAO in the Dex group was higher than that of the Con group (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA) in the last week of the experiment (

Figure 4A). Also, on day 21, the results showed that the LPS of the Dex group was higher than that of the Con group (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA) (

Figure 4B).

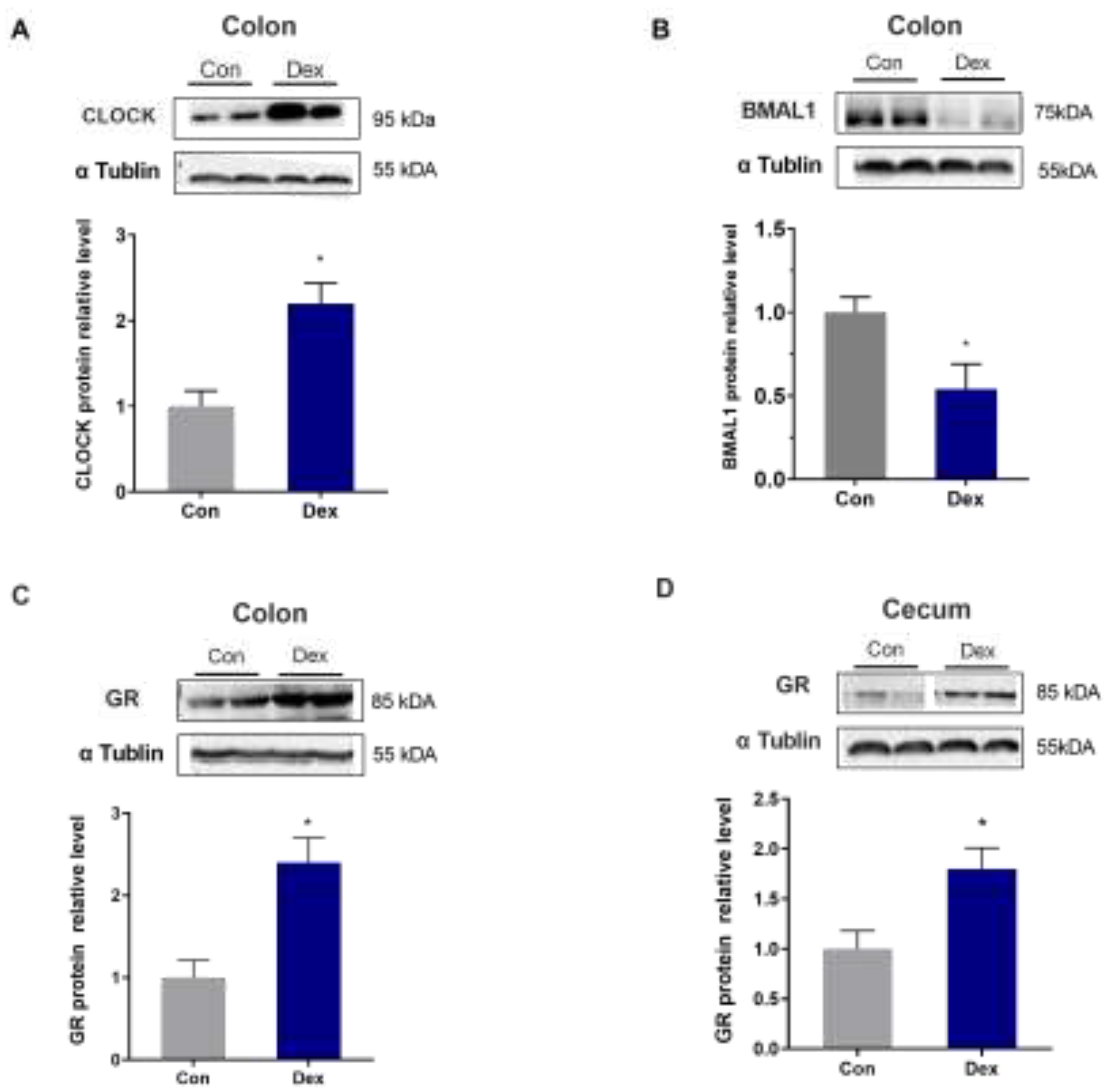

3.5. Effect of Chronic Exposure to DEX on CLOCK\BMAL1 and GR Protein Expression

Through further analysis of the protein expression in the colon and cecum, we found that chronic Dex treatment significantly up-regulated the expression of CLOCK protein and down-regulated the expression of BMAL1 (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA) (

Figure 5A and 5B). In addition, the expression of GR was significantly increased in the treatment group compared with the control group in the colon and cecum (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA) (

Figure 5C and 5D).

4. Discussion

In this study, chronic exposure to Dex treatment led to the disturbance of the circadian rhythm of plasma melatonin levels in the goats, indicating the destruction of internal biological rhythm. Dex treatment was found to reduce cortisol content in mammals. GCs exert feedback inhibition on their own secretion by blocking the effects of the corticotrophin releasing hormone on the pituitary gland [16,17]. In this study, the endogenous cortisol secretion was inhibited significantly by Dex treatment. These observations demonstrated that an experimental model of chronic GC administration to goats has been well established.

In order to investigate the cause of the decrease in melatonin, we detected the critical enzyme of melatonin synthesis, and the results showed that the amount of AANAT synthesis decreased in pineal. Therefore, long-term exposure to Dex leads to a decrease in AANAT synthesis. In mice, chronic exposure to Dex caused a decrease in melatonin and critical enzymes of melatonin synthesis [5], which is in line with our results. Previous studies showed that MDA and GSH are affected by melatonin [13], and in our results, a decrease in plasma melatonin also leads to a decrease of GSH and an increase of MDA in plasma .

In our experiment, we also found that long-term injection of Dex led to a decrease in the secretion of melatonin in the intestine. Melatonin in the intestine is crucial for maintaining normal intestinal function and immunity. The melatonin concentration may be related to the imbalance of intestinal flora, increased inflammatory factors, and even the change in intestinal barrier permeability [8,14]. The results also showed that the AANAT synthesis decreased in the colon of goats, which caused the decrease in melatonin. Previous studies have also shown that insufficient melatonin secretion in the gut leads to intestinal mucosal damage and microbial disturbance [2]. Our experimental results showed that DAO and LPS in the plasma increased, indicating that intestinal barrier function might be impaired.

Studies have shown that disruption of biology rhythm can cause damage to the intestinal barrier and is associated with many intestinal diseases [20]. Preview studies have reported that dysregulation of intrinsic clock mechanisms can cause metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [21,22]. In ruminants, the effects of chronic exposure to DEX on genes expression associated with the circadian clock have been explored in this study. In the past few years, the expression profiles of clock genes in the peripheral blood have been investigated and these and few other studies demonstrate that clock genes oscillate not only in the central nervous system but also in peripheral organs and blood [23,24]. Time variation of clock genes in the whole blood have been observed in humans, rats, dogs, cows and horses. In cows, mRNA expression of Bmal1, Clock, Per2, and Cry2 peaked in the early night[25,26]. The transcriptional/translational feedback loop of genes such as clock, cry1, cry2, per1, and per2 plays an key role in the biological clock. We observed a highly robust daily rhythm of the expression of each studied clock gene in the blood. Each gene showed a different amount of expression (Mesor) and amplitude of rhythm, compared to the other investigated genes. All rhythmic genes showed a nocturnal acrophase except Per 3. Chronic Dex exposure blunted the circadian rhythms of all the major clock genes in blood. Dex caused a four hour delay in the daytime peak of Per 3 compared to the control group. Blood is not a homogeneous tissue, and different cell types are not synchronized together, which can explain why many positive (Clock and Bmal1) and negative (Cry1 and Per2) clock elements displayed in peripheral circadian oscillators are not expressed in reverse[27,28,29].

Conclusions

The mechanisms by which chronic Dex alters the circadian gene expression in the goat are largely unknown. In our experimental results, the protein expression of GR was upregulated in intestinal epithelial cells, and the expression of CLOCK and BMAL1 proteins also changed. It is likely that Dex directly regulates clock gene expression through GR mediated transcriptional regulation[30]. However, melatonin is a crucial regulator in controlling circadian rhythms [31]. and the loss of circadian rhythm of plasma melatonin corresponded to the diminished circadian pattern of clock genes in this study. We speculate that chronic Dex may indirectly affects the expression rhythm of circadian clock gene through alterations in melatonin secretion.

Author Contributions

The authors’ contributions are as follows: Cai, L.P, Chen, Q, Hua, C.F, and Ni, Y.D conceived the present study and explained the data. Cai, L.P, Niu, LQ and Hua, C.F conducted the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Wu, L., Ni, Y.D gave critical suggestions during the experiment and writing the manuscript. Chen, Q, Hua, C.F, Kong, Q.J, participated in the chemical analysis and collected the data. All the authors revised the manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Project no. 31572433) and the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Project no. 32172810). The authors thank the 2021 Youth Science and Technology Innovation Project (1732922101) that Jiangsu University of Science and Technology provided.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Nanjing Agricultural University. The project number is 31972638. The sampling procedures according to the “Guidelines on Ethical Treatment of Experimental Animals” (2006) No.398 set by the Ministry of Science and Technology, China.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

None of the data was deposited in an official repository. Data that support those study findings are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the technician team at Nanjing Agriculture University led by Y.D. Ni, for their assistance in caring for the goats throughout the experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad, S.B.; Ali, A.; Bilal, M.; Rashid, S.M.; Wani, A.B.; Bhat, R.R.; Rehman, M.U. Melatonin and Health: Insights of Melatonin Action, Biological Functions, and Associated Disorders. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2023, 43, 2437–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, J.; Reiter, R.J.; Ma, X. Melatonin mediates mucosal immune cells, microbial metabolism, and rhythm crosstalk: A therapeutic target to reduce intestinal inflammation. Med Res Rev 2020, 40, 606–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claustrat, B.; Leston, J. Melatonin: Physiological effects in humans. Neurochirurgie 2015, 61, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, F.; Sutradhar, S.; Das, P.; Mukherjee, S. Gut melatonin: A potent candidate in the diversified journey of melatonin research. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2021, 303, 113693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses-Santos, D.; Buonfiglio, D.D.C.; Peliciari-Garcia, R.A.; Ramos-Lobo, A.M.; Souza, D.D.N.; Carpinelli, A.R.; Carvalho, C.R.O.; Sertie, R.A.L.; Andreotti, S.; Lima, F.B.; et al. Chronic treatment with dexamethasone alters clock gene expression and melatonin synthesis in rat pineal gland at night. Nat Sci Sleep 2018, 10, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Wang, Z.; Cao, J.; Dong, Y.; Chen, Y. Melatonin alleviates oxidative stress in sleep deprived mice: Involvement of small intestinal mucosa injury. Int Immunopharmacol 2020, 78, 106041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteleone, P.; Fuschino, A.; Nolfe, G.; Maj, M. Temporal relationship between melatonin and cortisol responses to nighttime physical stress in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1992, 17, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Kim, S.H.; Park, J.W.; Kho, Y.; Seok, P.R.; Shin, J.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Jun, J.H.; Jung, H.C.; Kim, E.K. Melatonin in the colon modulates intestinal microbiota in response to stress and sleep deprivation. Intest Res 2020, 18, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.A.; Tamura, E.K.; D'Argenio-Garcia, L.; Muxel, S.M.; da Silveira Cruz-Machado, S.; Marcola, M.; Carvalho-Sousa, C.E.; Cecon, E.; Ferreira, Z.S.; Markus, R.P. Dual Effect of Catecholamines and Corticosterone Crosstalk on Pineal Gland Melatonin Synthesis. Neuroendocrinology 2017, 104, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutterschmidt, D.I.; Mason, R.T. Temporally distinct effects of stress and corticosterone on diel melatonin rhythms of red-sided garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis). Gen Comp Endocrinol 2010, 169, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Han, W.; Zhang, A.; Zhao, M.; Cong, W.; Jia, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhao, R. Chronic corticosterone disrupts the circadian rhythm of CRH expression and m(6)A RNA methylation in the chicken hypothalamus. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2022, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnino-Subiabre, A.; Orellana, J.A.; Carmona-Fontaine, C.; Montiel, J.; Diaz-Veliz, G.; Seron-Ferre, M.; Wyneken, U.; Concha, M.L.; Aboitiz, F. Chronic stress decreases the expression of sympathetic markers in the pineal gland and increases plasma melatonin concentration in rats. J Neurochem 2006, 97, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggiogalle, E.; Jamshed, H.; Peterson, C.M. Circadian regulation of glucose, lipid, and energy metabolism in humans. Metabolism 2018, 84, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, K.; Cooke, A.; Chang, H.; Weaver, D.R.; Breault, D.T.; Karpowicz, P. The Circadian Clock Gene BMAL1 Coordinates Intestinal Regeneration. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 4, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoko, O.O.; Kono, H.; Ishimaru, K.; Miyake, K.; Kubota, T.; Ogawa, H.; Okumura, K.; Shibata, S.; Nakao, A. Expressions of tight junction proteins Occludin and Claudin-1 are under the circadian control in the mouse large intestine: implications in intestinal permeability and susceptibility to colitis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e98016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapolsky, R.M.; Armanini, M.P.; Packan, D.R.; Sutton, S.W.; Plotsky, P.M. Glucocorticoid feedback inhibition of adrenocorticotropic hormone secretagogue release. Relationship to corticosteroid receptor occupancy in various limbic sites. Neuroendocrinology 1990, 51, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, M.A.; Kim, P.J.; Kalman, B.A.; Spencer, R.L. Dexamethasone suppression of corticosteroid secretion: evaluation of the site of action by receptor measures and functional studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2000, 25, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, G.; Ozturk, G.; Guney, S.; Sinanoglu, O.; Tuncdemir, M. Protective effect of melatonin and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Ren Fail 2013, 35, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Ma, Y.; Ding, S.; Jiang, H.; Fang, J. Effects of Melatonin on Intestinal Microbiota and Oxidative Stress in Colitis Mice. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018, 2607679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, D. Biological Clock and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Review: From the Standpoint of the Intestinal Barrier. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2022, 2022, 2939921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.M.; Carter, A.M.; Grant, P.J. Association between polymorphisms in the Clock gene, obesity and the metabolic syndrome in man. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008, 32, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimba, S.; Ogawa, T.; Hitosugi, S.; Ichihashi, Y.; Nakadaira, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Tezuka, M.; Kosuge, Y.; Ishige, K.; Ito, Y.; et al. Deficient of a clock gene, brain and muscle Arnt-like protein-1 (BMAL1), induces dyslipidemia and ectopic fat formation. PLoS One 2011, 6, e25231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.A.; Viggars, M.R.; Esser, K.A. Metabolism and exercise: the skeletal muscle clock takes centre stage. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2023, 19, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, S.; Numano, R.; Abe, M.; Hida, A.; Takahashi, R.; Ueda, M.; Block, G.D.; Sakaki, Y.; Menaker, M.; Tei, H. Resetting central and peripheral circadian oscillators in transgenic rats. Science 2000, 288, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teboul, M.; Barrat-Petit, M.A.; Li, X.M.; Claustrat, B.; Formento, J.L.; Delaunay, F.; Levi, F.; Milano, G. Atypical patterns of circadian clock gene expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Mol Med (Berl) 2005, 83, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmori, K.; Nishikawa, S.; Oku, K.; Oida, K.; Amagai, Y.; Kajiwara, N.; Jung, K.; Matsuda, A.; Tanaka, A.; Matsuda, H. Circadian rhythms and the effect of glucocorticoids on expression of the clock gene period1 in canine peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Vet J 2013, 196, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, A.; Gonnenwein, S.; Bischoff, S.C.; Sherman, H.; Chapnik, N.; Froy, O.; Lorentz, A. The circadian clock is functional in eosinophils and mast cells. Immunology 2013, 140, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellet, M.M.; Sassone-Corsi, P. Mammalian circadian clock and metabolism - the epigenetic link. J Cell Sci 2010, 123, 3837–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachon, F.; Nagoshi, E.; Brown, S.A.; Ripperger, J.; Schibler, U. The mammalian circadian timing system: from gene expression to physiology. Chromosoma 2004, 113, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eachus, H.; Oberski, L.; Paveley, J.; Bacila, I.; Ashton, J.P.; Esposito, U.; Seifuddin, F.; Pirooznia, M.; Elhaik, E.; Placzek, M.; et al. Glucocorticoid receptor regulates protein chaperone, circadian clock and affective disorder genes in the zebrafish brain. Dis Model Mech 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Gall, C.; Weaver, D.R.; Moek, J.; Jilg, A.; Stehle, J.H.; Korf, H.W. Melatonin plays a crucial role in the regulation of rhythmic clock gene expression in the mouse pars tuberalis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2005, 1040, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).