Submitted:

30 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

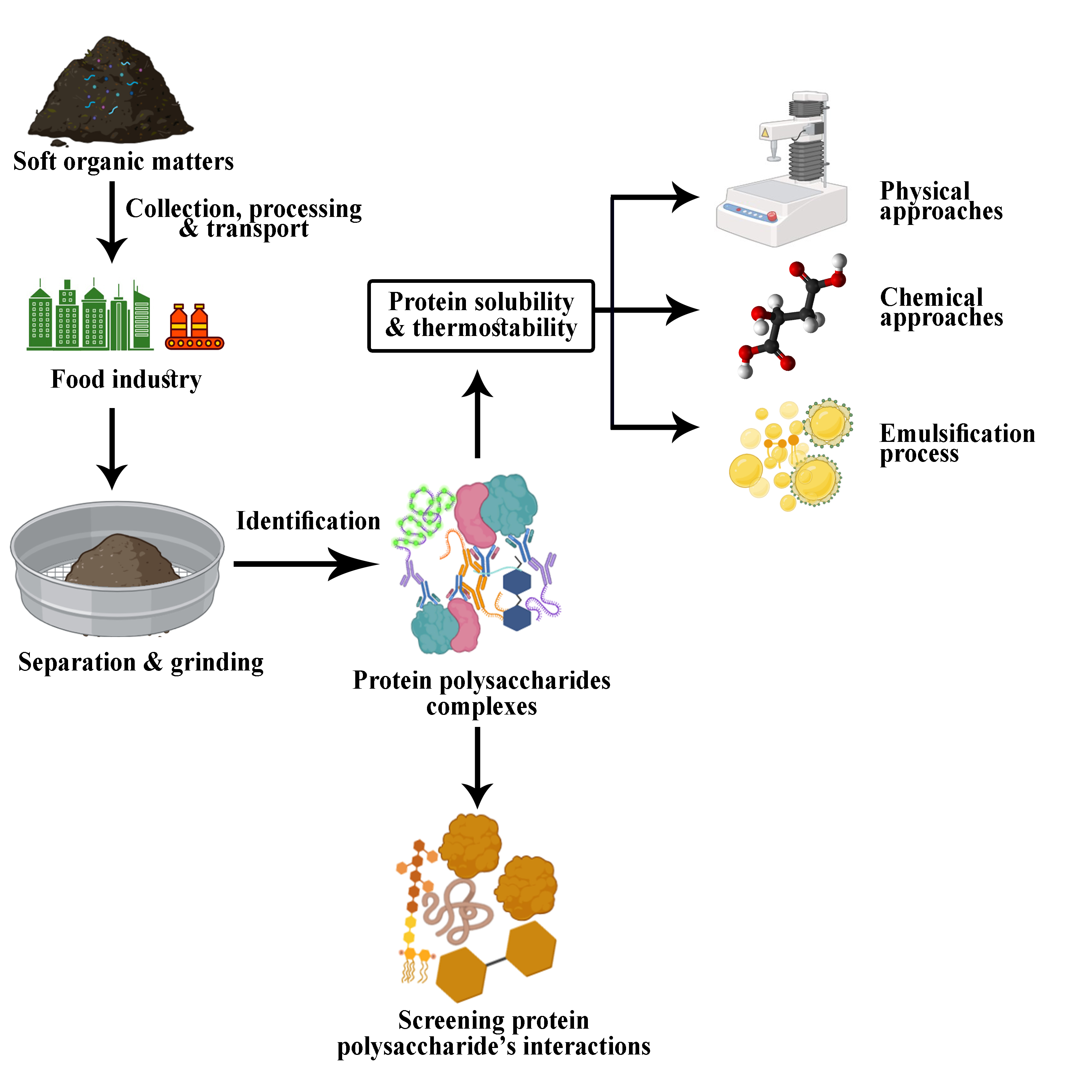

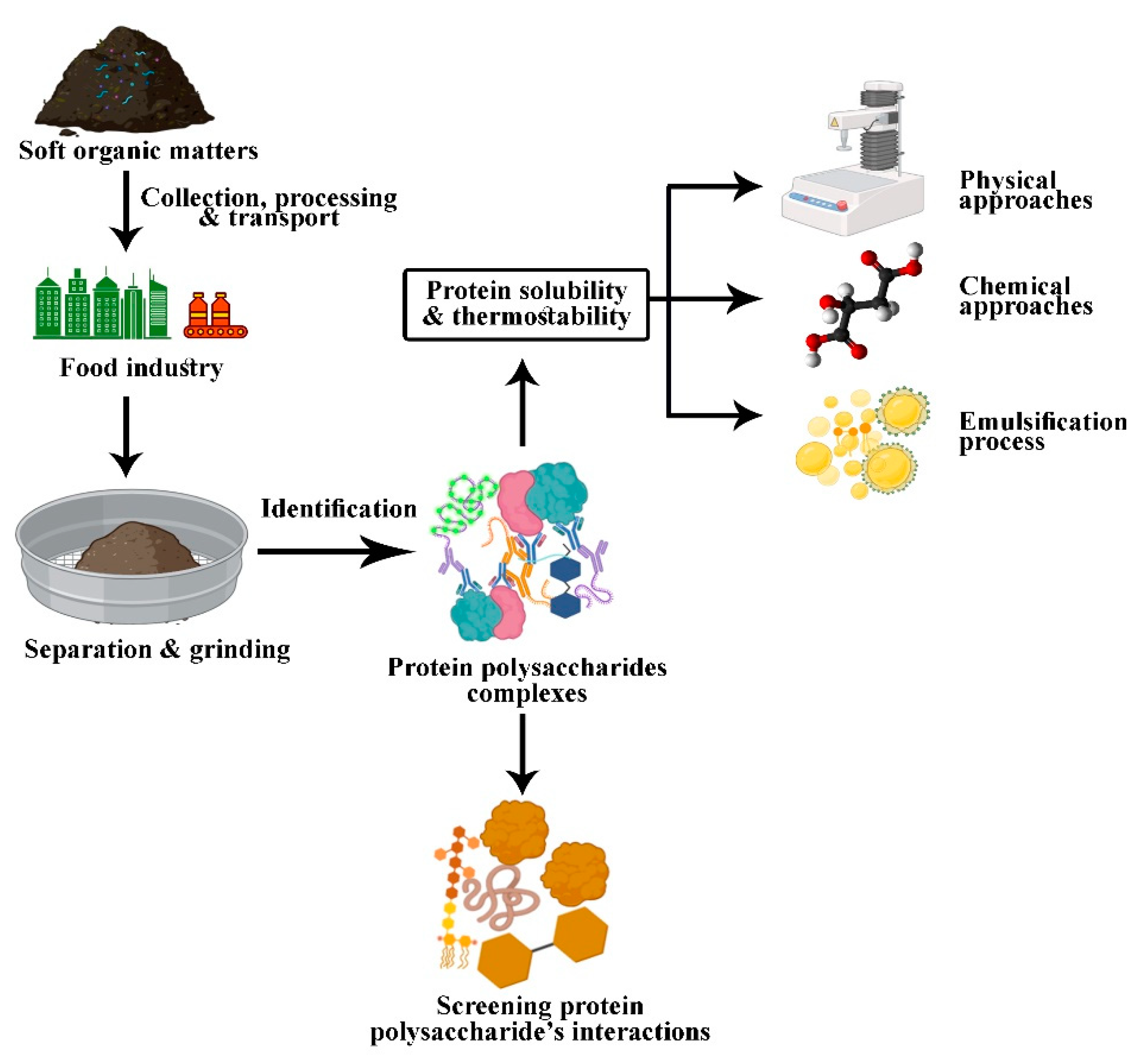

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

- Soft matter, complex fluids, significantly impact the structure and sensory attributes of foods

- Milk and mayonnaise show proteins’ role in stabilizing emulsions, crucial for consistency

- Polysaccharide-protein interactions are key to the texture and rheology of semi-solid foods

- Stable assembly structures are essential for improving food quality and meeting dietary needs

- Investigating soft matter & biopolymer interactions is key to optimizing food stability & texture

1. Introduction

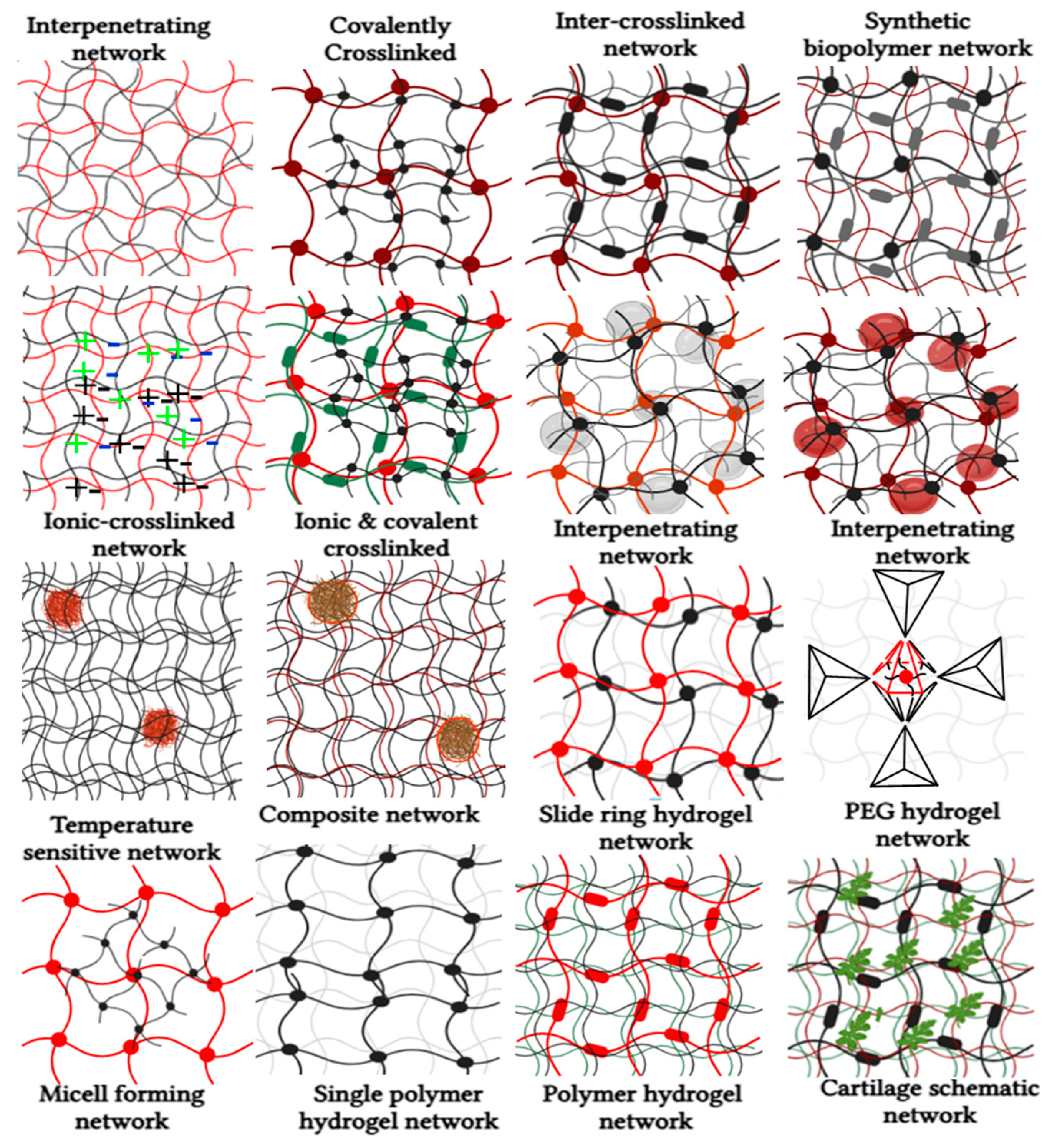

2. Consistency Capacity of Soft Matter

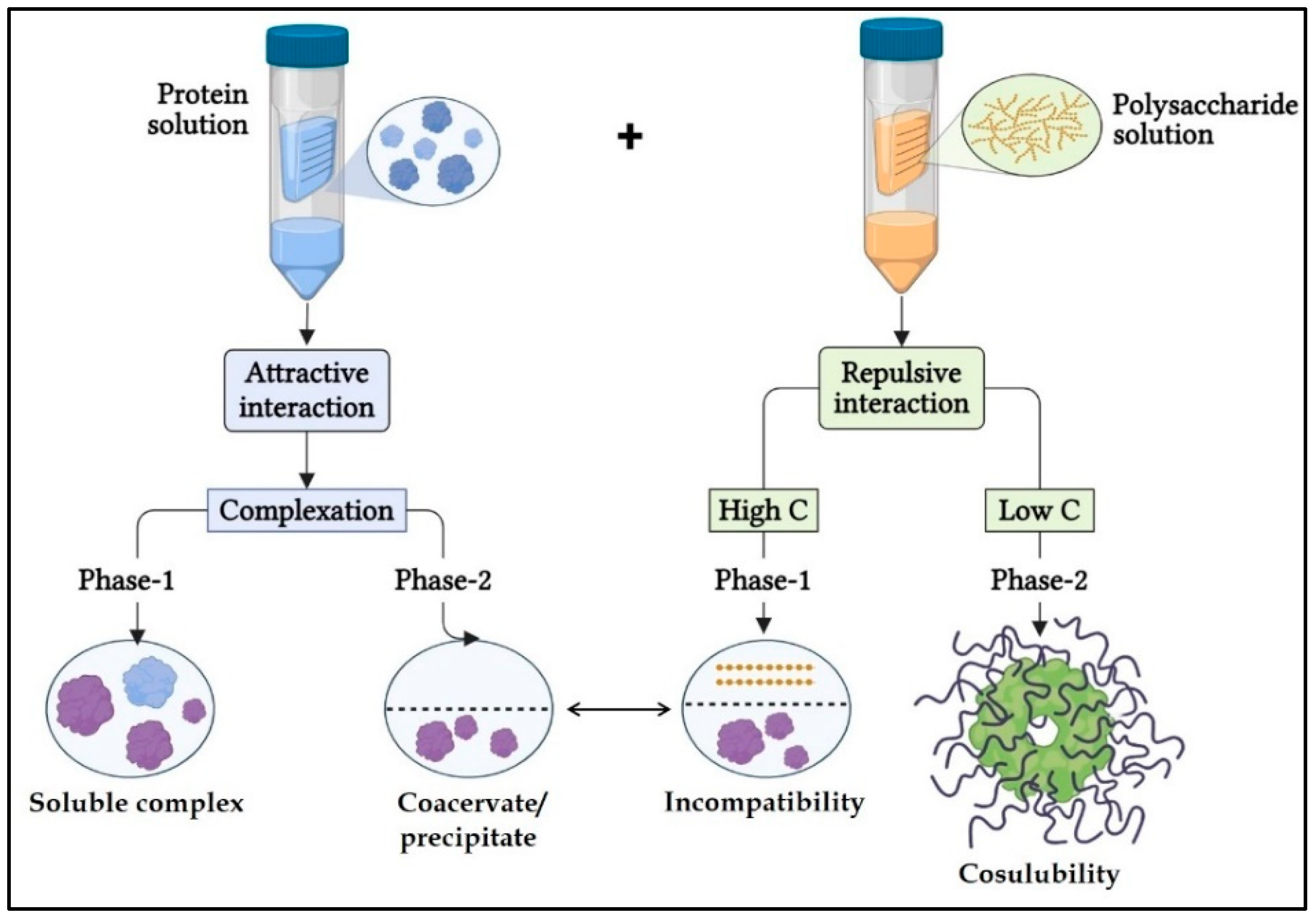

3. Phase-Specificity Screening

- I.

- Biopolymer concentration;

- II.

- The biopolymers’ molecular weight, figure, charge, and conformation;

- III.

- Environmental factors include the mechanical field, pH, ionic strength, and temperature.

4. The Stability of the Manufacturing Mechanism

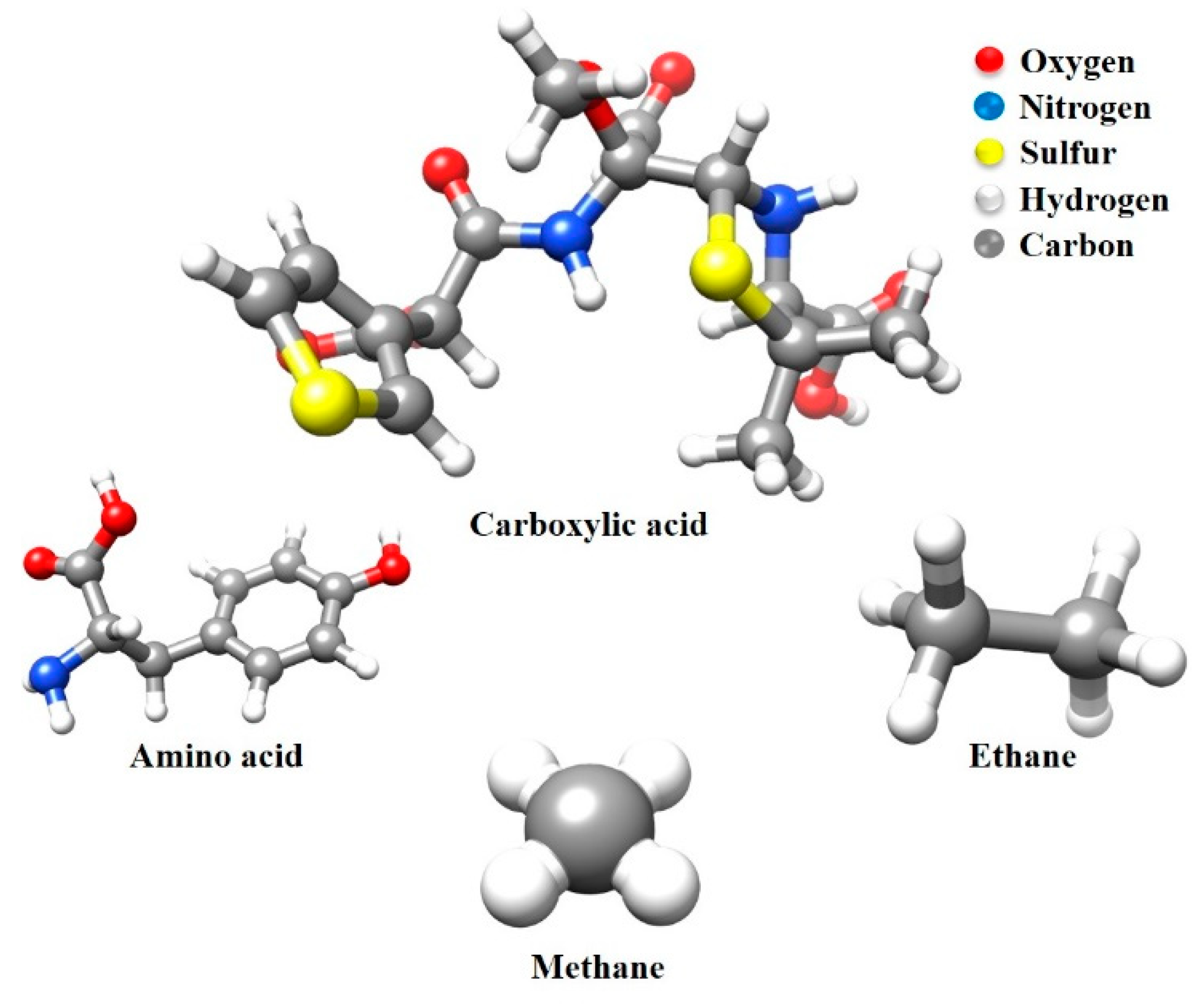

4.1. Weak Interactions in Food Microstructure and Stability

4.2. Protein-Polysaccharide Interactions and Stability in Food Systems

4.2.1. Optimizing Protein Functionality with Processing Techniques

4.2.1.1. Thermal Treatments

4.2.1.2. Homogenization

4.2.1.3. Superfine Grinding

4.2.1.4. Ultrasonication

4.2.2. Chemical Methods of Protein-Polysaccharide Interaction for Food Stability

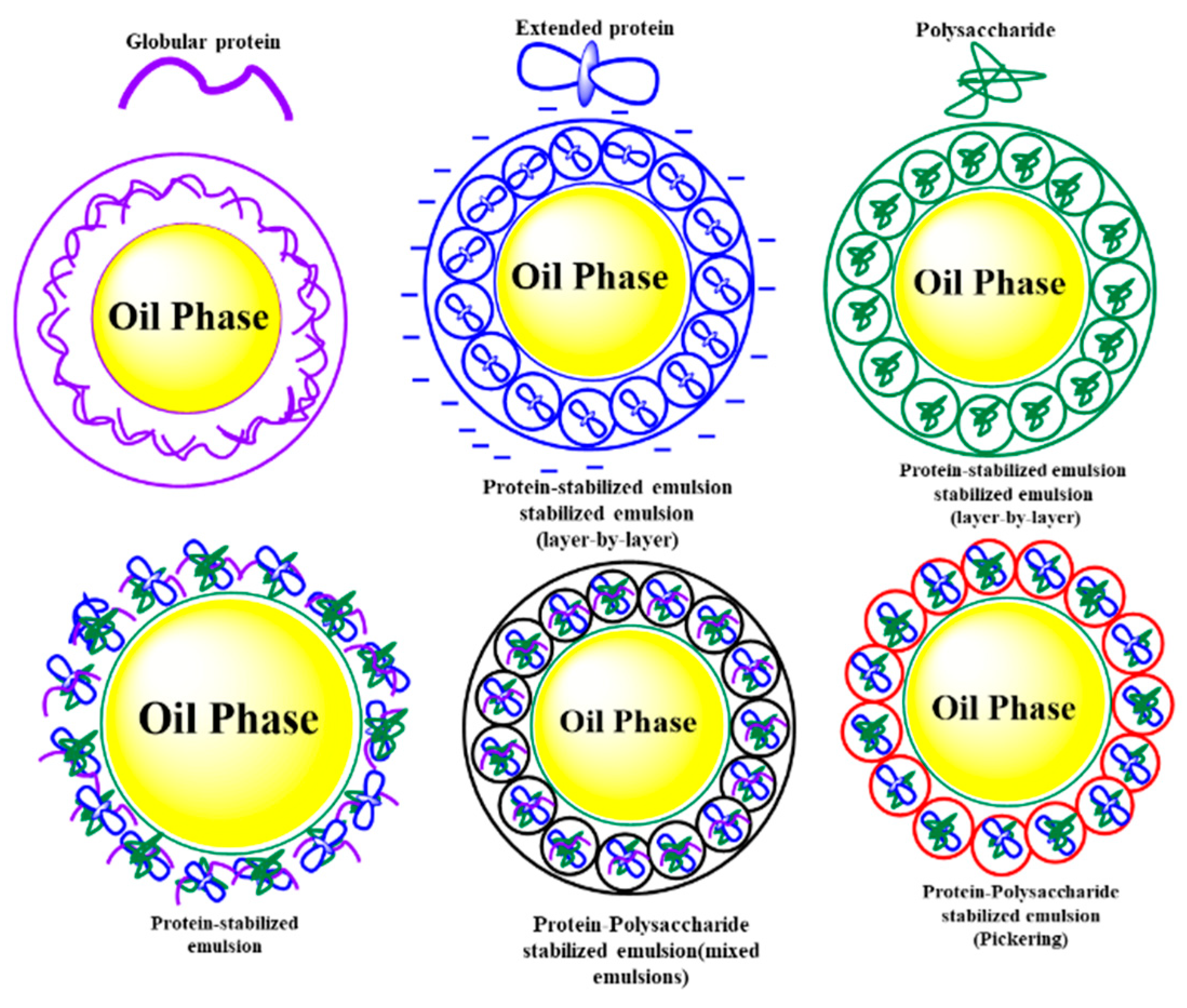

4.2.3. Mechanisms and Methods for Enhancing Emulsion Stability

5. Factors Influencing Polysaccharide-Protein Interactions in Food Systems

5.1. Covalent Cross-Linking in Polysaccharide-Protein Interactions

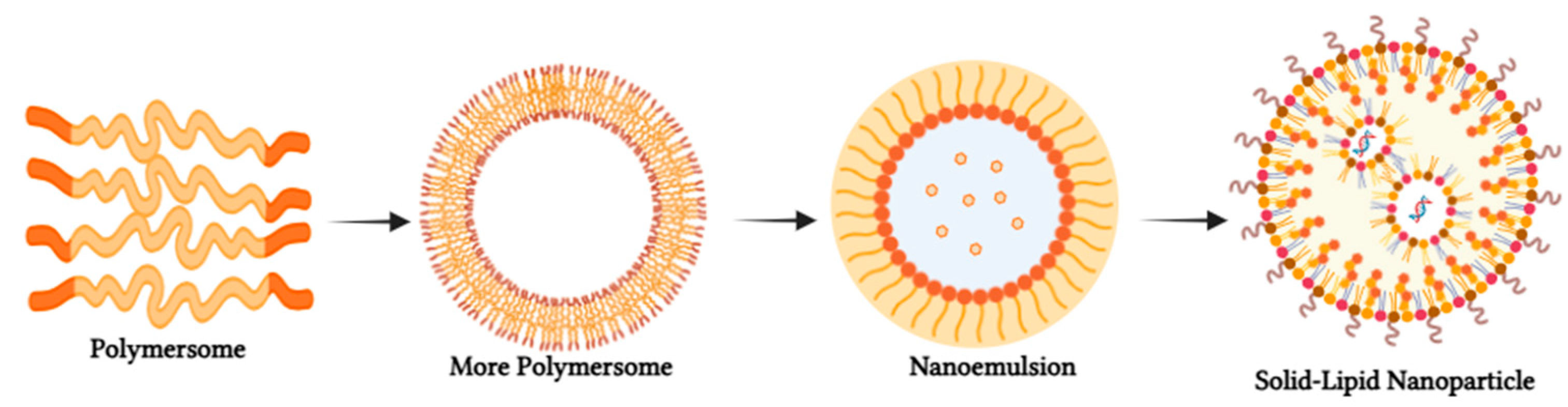

5.2. Layer-by-Layer Assembly and Polysaccharide-Protein Interactions

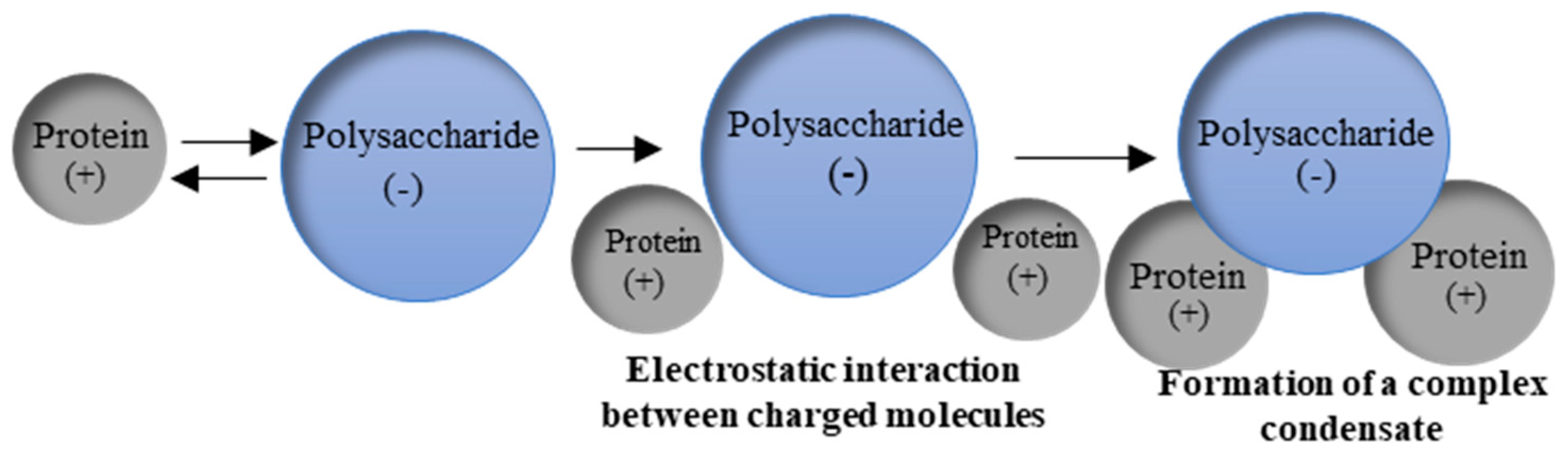

5.3. Electrostatic Interactions in Protein-Polysaccharide Complex Formation

5.4. Steric Hindrance in Protein-Polysaccharide Interactions

5.5. Impact of Hydrogen Bonding on Polysaccharide-Protein Interactions (HBs)

5.6. Interactions Driven by Hydrophobic Forces

6. The Food Soft-Material Suitability and Assembling Structural Stable Evaluation

6.1. Phase Model Approach

6.2. Turbidity Method

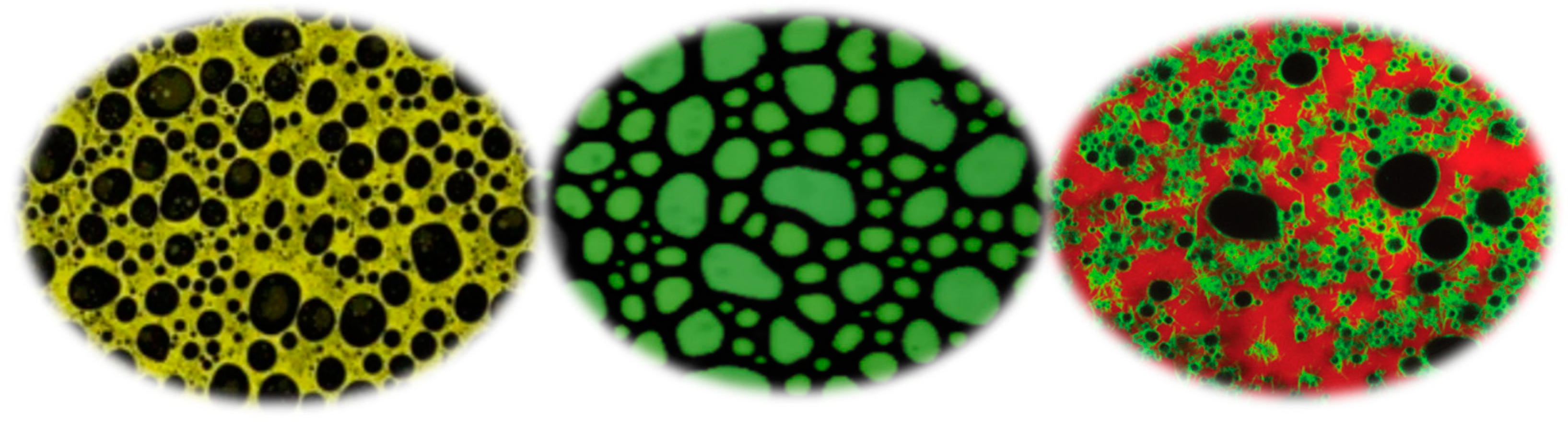

6.3. Microscopic Method

6.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

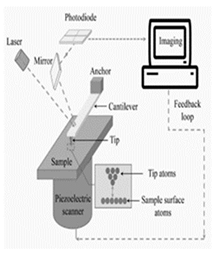

6.3.2. Microscope Using Atomic Force (AFM)

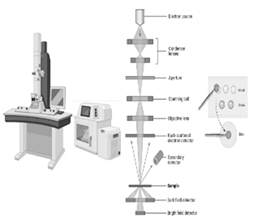

6.3.3. Utilizing a Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

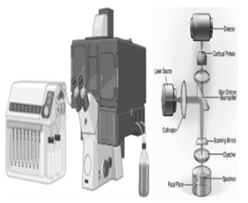

6.3.4. Scanning Microscope with Confocal Laser (CLSM)

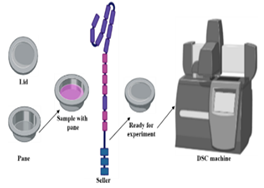

6.4. Scanning Differential Equations (DSC)

6.5. Rheological and Textural Analysis

6.5.1. Rheological Measurements in Food

6.5.2. Textural Analysis of Food Properties

6.5.3. Enhancing the Rheological and Textural Analysis Section

6.6. Physicochemical Characterization

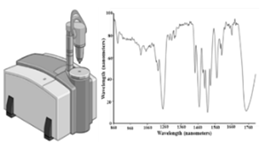

6.6.1. Infrared Fourier Transform (FTIR)

6.6.2. Raman Spectroscopy for Non-Destructive Molecular Identification and Analysis

6.7. Macromolecular Characterization of Component Compatibility

7. Challenges and Limitations of the Methods Used Currently in Characterizing Soft Matters

8. New Trends in the Fields of Soft-Matter Intricate Food Manufacturing

8.1. Printing of Soft-Matter-Induced Food Structures

8.2. AI and Machine Learning in Food Formulation

8.3. Biodegradable and Edible Packaging

8.4. Precision Fermentation for Novel Ingredients

8.5. Advanced Imaging and Spectroscopy Techniques

8.6. Robotics and Automation in Food Processing

8.7. Personalized Nutrition and Functional Foods

8.8. Phytochemical-Induced Immune-Stimulating Functional Foods

9. Conclusions

Declaration of competing interest

Acknowledgment

References

- Grier, D.G. A Revolution in Optical Manipulation. Nature 2003, 424, 810–816. [CrossRef]

- Weitz, D.A. Soft Materials Evolution and Revolution. Nat. Mater. 2022, 21, 986–988. [CrossRef]

- Hanani, N. Characteristics of Soft Matters 1.1. An Autom. Irrig. Syst. Using Arduino Microcontroller 2018, 3, 2–6.

- Schifferstein, H.N.J.; Kudrowitz, B.M.; Breuer, C. Food Perception and Aesthetics - Linking Sensory Science to Culinary Practice. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2022, 20, 293–335. [CrossRef]

- Mahato, S.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, D.W. Glass Transitions as Affected by Food Compositions and by Conventional and Novel Freezing Technologies: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 94, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Heerschop, S.N.; Cardinaals, R.P.M.; Biesbroek, S.; Kanellopoulos, A.; Geleijnse, J.M.; van ‘t Veer, P.; van Zanten, H.H.E. Understanding the Complexity of the Food System: Differences and Commonalities between Two Optimization Models. 2023, 17. [CrossRef]

- Assenza, S.; Mezzenga, R. Soft Condensed Matter Physics of Foods and Macronutrients. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2019, 1, 551–566. [CrossRef]

- Runthala, A.; Mbye, M.; Ayyash, M.; Xu, Y.; Kamal-Eldin, A. Caseins: Versatility of Their Micellar Organization in Relation to the Functional and Nutritional Properties of Milk. Molecules 2023, 28, 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Taslikh, M.; Mollakhalili-Meybodi, N.; Alizadeh, A.M.; Mousavi, M.M.; Nayebzadeh, K.; Mortazavian, A.M. Mayonnaise Main Ingredients Influence on Its Structure as an Emulsion. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 2108–2116. [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, M.; Tran, R.; Vera, G.; Niedrist, D.; Rousset, A.; Pierre, R.; Shastri, V.P.; Forget, A. Hydrogel-Forming Algae Polysaccharides: From Seaweed to Biomedical Applications. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 1027–1052. [CrossRef]

- Marhamati, M.; Ranjbar, G.; Rezaie, M. Effects of Emulsifiers on the Physicochemical Stability of Oil-in-Water Nanoemulsions: A Critical Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 340, 117218. [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Morales, E.A.; Mendez-Montealvo, G.; Velazquez, G. Interactions of the Molecular Assembly of Polysaccharide-Protein Systems as Encapsulation Materials. A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 295, 102398. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.C.; Bhokisham, N.; Li, J.; Hong, K.L.; Quan, D.N.; Tsao, C.Y.; Bentley, W.E.; Payne, G.F. Biofabricating Functional Soft Matter Using Protein Engineering to Enable Enzymatic Assembly. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 1809–1822. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, A.; Li, D.; Guo, Y.; Sun, L. Applications of Mixed Polysaccharide-Protein Systems in Fabricating Multi-Structures of Binary Food Gels—A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 197–210. [CrossRef]

- Toniazzo, T.; Fabi, J.P. Versatile Polysaccharides for Application to Semi-Solid and Fluid Foods: The Pectin Case. Fluids 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh, P.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Advanced Characterization Techniques for Nanostructured Materials in Biomedical Applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2024, 7, 122–143. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Sman, R.G.M. Soft Matter Approaches to Food Structuring. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 176–177, 18–30. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.L.; Kubo, M.T.K.; Caetano-Silva, M.E.; Carvalho, G.R.; Augusto, P.E.D. Chapter 5 - How Food Structure Influences the Physical, Sensorial, and Nutritional Quality of Food Products. In; Cerqueira, M.Â.P.R., Pastrana Castro Health and Well-Being, L.M.B.T.-F.S.E. and D. for I.N., Eds.; Academic Press, 2023; pp. 113–138 ISBN 978-0-323-85513-6.

- Kim, H. J., Kim, J. H., Yu, D. H., Je, A. R., Choi, S., Kweon, H. S., ... & Huh, Y. H. (2017). Large-Area Ultrastructural Analysis on Alteration of Synaptic Vesicles in the 835MHz Radiofrequency-exposed Cerebral Cortex of Mice Brain Using Limitless Panorama and 3D Electron Tomography. Microscopy and Microanalysis, 23(S1), 1160-1161.

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, K.; Qian, H.; Ramachandran, B.; Jiang, F. The Advances of Characterization and Evaluation Methods for the Compatibility and Assembly Structure Stability of Food Soft Matter. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 753–763. [CrossRef]

- Zeeb, B.; Jost, T.; McClements, D.J.; Weiss, J. Segregation Behavior of Polysaccharide–Polysaccharide Mixtures—a Feasibility Study. Gels 2019, 5, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Recent Progress in Hydrogel Delivery Systems for Improving Nutraceutical Bioavailability. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 68, 238–245. [CrossRef]

- Peak, C.W.; Wilker, J.J.; Schmidt, G. A Review on Tough and Sticky Hydrogels. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2013, 291, 2031–2047. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Sun, C.; Li, Q. Interaction between the Polysaccharides and Proteins in Semisolid Food Systems; Elsevier, 2018; ISBN 9780128140451.

- Rackers, J.A.; Ponder, J.W. Classical Pauli Repulsion: An Anisotropic, Atomic Multipole Model. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150. [CrossRef]

- Yue, K.; Huang, M.; Marson, R.L.; Hec, J.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Yan, X.; Wu, K.; et al. Geometry Induced Sequence of Nanoscale Frank-Kasper and Quasicrystal Mesophases in Giant Surfactants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 14195–14200. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Yan, X.Y.; Guo, Q.Y.; Lei, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, F.; et al. Expanding Quasiperiodicity in Soft Matter: Supramolecular Decagonal Quasicrystals by Binary Giant Molecule Blends. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022, 119, 2–7. [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.; Tchameni, Z.F.N.; Bhat, Z.F.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaglan, S. Recent Insights on the Conformational Changes, Functionality, and Physiological Properties of Plant-Based Protein–Polyphenol Conjugates. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 2131–2154. [CrossRef]

- Ubbink, J. Soft Matter Approaches to Structured Foods: From ‘“Cook-and-Look”’ to Rational Food Design? 2012, 9–35. [CrossRef]

- Paper, C. Soft Matter Physics Can Set Biological Clock of Industrial Food Science and (Bio) Technology. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Punia, S.; Scott, W.; Omodunbi, A. Recent Advances in Thermoplastic Starches for Food Packaging : A Review. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 30, 100743. [CrossRef]

- Ogborn, J. Soft Matter: Food for Thought. Phys. Educ. 2004, 39, 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Tu, R.; Song, H.; Dong, K.; Geng, F.; Chen, L.; Huang, Q.; Wu, Y. Fabrication and Characterization of Gelatin–EGCG–Pectin Ternary Complex: Formation Mechanism, Emulsion Stability, and Structure. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 1442–1453. [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J.E.; Behnsen, J.; Duller, R.A.; Nichols, T.E.; Worden, R.H. Particle Size Analysis: A Comparison of Laboratory-Based Techniques and Their Application to Geoscience. Sediment. Geol. 2024, 464, 106607. [CrossRef]

- Listov, D.; Goverde, C.A.; Correia, B.E.; Fleishman, S.J. Opportunities and Challenges in Design and Optimization of Protein Function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 639–653. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, T.; Li, H.; Sedaghat Doost, A.; Van Damme, E.J.M.; De Meulenaer, B.; Van der Meeren, P. Improved Heat Stability of Recombined Evaporated Milk Emulsions by Wet Heat Pretreatment of Skim Milk Powder Dispersions. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 118, 106757. [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Chen, H.; Wu, C.; Du, M. The Mechanism of Improved Thermal Stability of Protein-Enriched O/W Emulsions by Soy Protein Particles; 2020; Vol. 11; ISBN 8641186332275.

- Ma, W.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Wu, C.; Du, M. Enhancing the Thermal Stability of Soy Proteins by Preheat Treatment at Lower Protein Concentration. Food Chem. 2020, 306. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Ma, W.; Cai, Y.; Wang, T. Preheat-Stabilized Pea Proteins with Anti-Aggregation Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 1288–1295. [CrossRef]

- Yiasmin, M.N.; Islam, M.S.; He, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, R.; Hua, X. Purification, Isolation, and Structure Characterization of Water Soluble and Insoluble Polysaccharides from Maitake Fruiting Body. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1879–1888. [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Matsumiya, K.; Kaneko, W.; Okazaki, M.; Matsumura, Y. Ultra-High-Pressure Homogenization Can Modify Colloidal, Interfacial, and Foaming Properties of Whey Protein Isolate and Micellar Casein Dispersions Differently According to the Temperature Condition. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 619, 126470. [CrossRef]

- Saricaoglu, F.T. Application of High-Pressure Homogenization (HPH) to Modify Functional, Structural and Rheological Properties of Lentil (Lens Culinaris) Proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 144, 760–769. [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.; Shi, X.; Wu, F.; Zou, H.; Chang, C.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, M.; Yu, C. Improving the Stability of Oil-in-Water Emulsions by Using Mussel Myo Fi Brillar Proteins and Lecithin as Emulsi Fi Ers and High-Pressure Homogenization. J. Food Eng. 2019, 258, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, G.; Plazzotta, S.; Calligaris, S.; Manzocco, L.; Nicoli, M.C. Impact of High Pressure Homogenization on Physical Properties, Extraction Yield and Biopolymer Structure of Soybean Okara. Lwt 2019, 113, 108324. [CrossRef]

- Hydrolysates, I.; Cha, Y.; Wu, F.; Zou, H.; Shi, X.; Zhao, Y.; Bao, J.; Du, M.; Yu, C. Improved Functional Properties of Oyster Protein. Molecules 2018. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, G.; Zeng, H.; Chen, L. Effects of High Pressure Homogenization on Faba Bean Protein Aggregation in Relation to Solubility and Interfacial Properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 83, 275–286. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wu, F.; Cha, Y.; Zou, H.; Bao, J.; Xu, R.; Du, M. Effects of High-Pressure Homogenization on Functional Properties and Structure of Mussel (Mytilus Edulis) Myofibrillar Proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 741–746. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhu, Y. Effects of Ultrafine Grinding Time on the Functional and Flavor Properties of Soybean Protein Isolate. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2020, 196, 111345. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, Z.; Pan, X.; Dai, Y.; Hou, H.; Wang, W.; Ding, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Dong, H. Effect of Grinding on the Structure of Pea Protein Isolate and the Rheological Properties of Its Acid-Induced Gels. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 3455–3462. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, R.; Ni, K.; Wu, T.; Luo, X.; Liang, B.; Zhang, M. Reduction of Particle Size Based on Superfine Grinding: Effects on Structure, Rheological and Gelling Properties of Whey Protein Concentrate. J. Food Eng. 2016, 186, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Nazari, B.; Mohammadifar, M.A.; Shojaee-Aliabadi, S.; Feizollahi, E.; Mirmoghtadaie, L. Effect of Ultrasound Treatments on Functional Properties and Structure of Millet Protein Concentrate. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 41, 382–388. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Li, X.; Taha, A.; Wei, Y.; Hu, T.; Fatamorgana, P.B.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, F.; Xu, X.; Pan, S.; et al. Effect of High Intensity Ultrasound on the Structure and Physicochemical Properties of Soy Protein Isolates Produced by Different Denaturation Methods. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 97, 105216. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Ma, W.; Cai, Y.; Wang, T. Preheat-Stabilized Pea Proteins with Anti-Aggregation Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 1288–1295. [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Zhao, N.; Sun, S.; Dong, X.; Yu, C. High-Intensity Ultrasonication Treatment Improved Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Mussel Sarcoplasmic Proteins and Enhanced the Stability of Oil-in-Water Emulsion. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 589, 124463. [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasuriya, S.N.; Nickerson, M.T. Review on Plant Protein–Polysaccharide Complex Coacervation, and the Functionality and Applicability of Formed Complexes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 5559–5571. [CrossRef]

- Pergande, M.R.; Cologna, S.M. Isoelectric Point Separations of Peptides and Proteins. Proteomes 2017, 5. [CrossRef]

- Gentile, L. ScienceDirect Protein – Polysaccharide Interactions and Aggregates in Food Formulations. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 48, 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Niyigaba, T.; Liu, D.; Habimana, J.D.D. The Extraction , Functionalities and Applications of Plant. Foods A Rev. 2021, 10, 23.

- Zang, Z.; Tang, S.; Li, Z.; Chou, S.; Shu, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y.; Tian, J.; et al. An Updated Review on the Stability of Anthocyanins Regarding the Interaction with Food Proteins and Polysaccharides. Compr. Rev. food Sci. food Saf. 2022, 21, 4378–4401. [CrossRef]

- Taha, A.; Casanova, F.; Šimonis, P.; Jonikaitė-Švėgždienė, J.; Jurkūnas, M.; Gomaa, M.A.; Stirkė, A. Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Glycation of Bovine Serum Albumin/Starch Conjugates Improved Their Emulsifying Properties. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 82. [CrossRef]

- Khalesi, H.; Emadzadeh, B.; Kadkhodaee, R.; Fang, Y. Effects of Biopolymer Ratio and Heat Treatment on the Complex Formation between Whey Protein Isolate and Soluble Fraction of Persian Gum. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2017, 38, 1234–1241. [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, G.; Ding, J.; Andrade, J.; Engeseth, N.J.; Feng, H. Effect of Plant Protein-Polysaccharide Complexes Produced by Mano-Thermo-Sonication and PH-Shifting on the Structure and Stability of Oil-in-Water Emulsions. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 47, 317–325. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. H., Sun, X., Huang, G. Q., & Xiao, J. X. (2018). Conjugation of Soybean Protein Isolate with Xylose/Fructose through Wet-Heating Maillard Reaction. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 12. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhou, X.; Ma, P.; Wang, Q. Effect of Different Carbohydrates on the Functional Properties of Black Rice Glutelin (BRG) Modified by the Maillard Reaction. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 93, 102979. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Chen, B.; Rao, J. Pea Protein Isolate–High Methoxyl Pectin Soluble Complexes for Improving Pea Protein Functionality: Effect of PH, Biopolymer Ratio and Concentrations. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 80, 245–253. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Feng, B.; Jiang, B.; Miao, M. Interaction between Soybean Protein and Tea Polyphenols under High Pressure. Food Chem. 2019, 277, 632–638. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, X.; Liang, L.; Xu, X. Gallic Acid-Aided Cross-Linking of Myofibrillar Protein Fabricated Soluble Aggregates for Enhanced Thermal Stability and a Tunable Colloidal State. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 11535–11544. [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.B.; Wang, B.; Zisu, B.; Adhikari, B. Complexation between Flaxseed Protein Isolate and Phenolic Compounds: Effects on Interfacial, Emulsifying and Antioxidant Properties of Emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 94, 20–29. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Ma, C.; McClements, D.J.; Gao, Y. A Comparative Study of Covalent and Non-Covalent Interactions between Zein and Polyphenols in Ethanol-Water Solution. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 63, 625–634. [CrossRef]

- García Arteaga, V.; Apéstegui Guardia, M.; Muranyi, I.; Eisner, P.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U. Effect of Enzymatic Hydrolysis on Molecular Weight Distribution, Techno-Functional Properties and Sensory Perception of Pea Protein Isolates. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 65, 102449. [CrossRef]

- Noman, A.; Xu, Y.; AL-Bukhaiti, W.Q.; Abed, S.M.; Ali, A.H.; Ramadhan, A.H.; Xia, W. Influence of Enzymatic Hydrolysis Conditions on the Degree of Hydrolysis and Functional Properties of Protein Hydrolysate Obtained from Chinese Sturgeon (Acipenser Sinensis) by Using Papain Enzyme. Process Biochem. 2018, 67, 19–28. [CrossRef]

- Zang, X.; Yue, C.; Wang, Y.; Shao, M.; Yu, G. Effect of Limited Enzymatic Hydrolysis on the Structure and Emulsifying Properties of Rice Bran Protein. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 85, 168–174. [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.P.; Siddiqi, R.A.; Sogi, D.S. Enzymatic Modification of Rice Bran Protein: Impact on Structural, Antioxidant and Functional Properties. Lwt 2021, 138, 110648. [CrossRef]

- Akbari, S.; Nour, A.H. Emulsion Types, Stability Mechanisms and Rheology: A Review. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 2018, 1, 11–17. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Pan, Y.; Jia, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Yin, L. Review on the Stability Mechanism and Application of Water-in-Oil Emulsions Encapsulating Various Additives. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 1660–1675. [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Díaz, C.; Wandersleben, T.; Marqués, A.M.; Rubilar, M. Multilayer Emulsions Stabilized by Vegetable Proteins and Polysaccharides. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 25, 51–57. [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Non-Covalent Interactions between Proteins and Polysaccharides. Biotechnol. Adv. 2006, 24, 621–625. [CrossRef]

- Loret, C.; Schumm, S.; Pudney, P.D.A.; Frith, W.J.; Fryer, P.J. Phase Separation and Molecular Weight Fractionation Behaviour of Maltodextrin/Agarose Mixtures. Food Hydrocoll. 2005, 19, 557–565. [CrossRef]

- Crocker, K.; Lee, K.K.; Chakraverti-wuerthwein, M.; Li, Z.; Tikhonov, M.; Mani, M.; Gowda, K.; Kuehn, S. Environmentally Dependent Interactions Shape Patterns in Gene Content across Natural Microbiomes. Nat. Microbiol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Pilania, G.; Batra, R.; Huan, T.D.; Kim, C.; Kuenneth, C.; Ramprasad, R. Polymer Informatics: Current Status and Critical next Steps. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Reports 2021, 144, 100595. [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Zhang, R.; Yao, P. Influence of Pea Protein Aggregates on the Structure and Stability of Pea Protein/Soybean Polysaccharide Complex Emulsions. Molecules 2015, 20, 5165–5183. [CrossRef]

- Min, H.Y.; Lee, H.Y. Molecular Targeted Therapy for Anticancer Treatment. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 1670–1694. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Huang, Q. Assembly of Protein-Polysaccharide Complexes for Delivery of Bioactive Ingredients: A Perspective Paper. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 1344–1352. [CrossRef]

- Boeriu, C.G.; Oudgenoeg, G.; Spekking, W.T.J.; Berendsen, L.B.J.M.; Vancon, L.; Boumans, H.; Gruppen, H.; Van Berkel, W.J.H.; Laane, C.; Voragen, A.G.J. Horseradish Peroxidase-Catalyzed Cross-Linking of Feruloylated Arabinoxylans with β-Casein. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 6633–6639. [CrossRef]

- Han, M.M.; Yi, Y.; Wang, H.X.; Huang, F. Investigation of the Maillard Reaction between Polysaccharides and Proteins from Longan Pulp and the Improvement in Activities. Molecules 2017, 22, 5–8. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Lu, X.; Li, N.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, R.; Tang, X.; Qiao, X. Effects and Mechanism of Free Amino Acids on Browning in the Processing of Black Garlic. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 4670–4676. [CrossRef]

- Alfayadh, H.M.; Hamk, M.L.; Ibrahim, K.J.; Al-Saadi, J.M. Effect of Milk Proteins Aggregation Using Transglutaminase and Maillard Reaction on Ca2+ Milk Gel. Kurdistan J. Appl. Res. 2018, 3, 63–67. [CrossRef]

- 88. Wusigale; Liang, L.; Luo, Y. Casein and Pectin: Structures, Interactions, and Applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 97, 391–403. [CrossRef]

- Chun Tie, Y.; Birks, M.; Francis, K. Grounded Theory Research: A Design Framework for Novice Researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Bian, T.; Gardin, A.; Gemen, J.; Houben, L.; Perego, C.; Lee, B.; Elad, N.; Chu, Z.; Pavan, G.M.; Klajn, R. Electrostatic Co-Assembly of Nanoparticles with Oppositely Charged Small Molecules into Static and Dynamic Superstructures. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, doi.org/10.1038/s41557-021-00752-9.

- Silva, C.E.P.; Loh, W. Chapter 2 - Fundamentals of Emulsion Formation and Stability. In Clay Minerals and Synthetic Analogous as Emulsifiers of Pickering Emulsions; Wypych, F., de Freitas, R.A.B.T.-D. in C.S., Eds.; Elsevier, 2022; Vol. 10, pp. 37–59 ISBN 1572-4352.

- Zang, X.; Wang, J.; Yu, G.; Cheng, J. Addition of Anionic Polysaccharides to Improve the Stability of Rice Bran Protein Hydrolysate-Stabilized Emulsions. Lwt 2019, 111, 573–581. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Strategies to Control and Inhibit the Flocculation of Protein-Stabilized Oil-in-Water Emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 96, 209–223. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Shao, G.; Qu, D.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, L.; Yang, L.; Li, R.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Dilatational Rheological and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Characterization of Oil-Water Interface: Impact of PH on Interaction of Soy Protein Isolated and Soy Hull Polysaccharides. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 99, 105366. [CrossRef]

- Zhi, L.; Liu, Z.; Wu, C.; Ma, X.; Hu, H.; Liu, H.; Adhikari, B.; Wang, Q.; Shi, A. Advances in Preparation and Application of Food-Grade Emulsion Gels. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 136399. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Song, W.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Some Physical Properties of Protein Moiety of Alkali-Extracted Tea Polysaccharide Conjugates Were Shielded by Its Polysaccharide. Molecules 2017, 22. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.K.; Pedersen, J.N.; Marie, R. Size and Surface Charge Characterization of Nanoparticles with a Salt Gradient. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Jiang, H.; Tu, J.; He, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, R.; Jin, W.; Han, J.; Liu, W. Effect of PH, Protein/Polysaccharide Ratio and Preparation Method on the Stability of Lactoferrin-Polysaccharide Complexes. Food Chem. 2024, 456, 140056. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Xiang, S.; Nie, K.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Fang, Y.; Nishinari, K.; Phillips, G.O.; Jiang, F. Whey Protein Isolate/Gum Arabic Intramolecular Soluble Complexes Improving the Physical and Oxidative Stabilities of Conjugated Linoleic Acid Emulsions. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 14635–14642. [CrossRef]

- Kala, R.; Samková, E.; Hanuš, O.; Pecová, L.; Sekmokas, K.; Riaukienė, D. Milk Protein Analysis: An Overview of the Methods – Development and Application. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendelianae Brun. 2019, 67, 345–359. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Van der Meeren, P.; Sun, W. New Insights into Protein–Polysaccharide Complex Coacervation: Dynamics, Molecular Parameters, and Applications. Aggregate 2024, 5, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Zhou, L.; Lyu, F.; Liu, J.; Ding, Y. The Complex of Whey Protein and Pectin: Interactions, Functional Properties and Applications in Food Colloidal Systems – A Review. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2022, 210, 112253. [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Sun, W.; Li, D.; Diao, J.; Xiu, P. Inhibition of Amyloid Nucleation by Steric Hindrance. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 10045–10054. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhong, Q. High Temperature-Short Time Glycation to Improve Heat Stability of Whey Protein and Reduce Color Formation. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 44, 453–460. [CrossRef]

- Wijayanti, H.B.; Bansal, N.; Deeth, H.C. Stability of Whey Proteins during Thermal Processing: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 1235–1251. [CrossRef]

- Giubertoni, G.; Hilbers, M.; Caporaletti, F.; Laity, P.; Groen, H.; Van der Weide, A.; Bonn, D.; Woutersen, S. Hydrogen Bonds under Stress: Strain-Induced Structural Changes in Polyurethane Revealed by Rheological Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 940–946. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Using Steric Hindrance to Manipulate and Stabilize Metal Halide Perovskites for Optoelectronics. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 7231–7247. [CrossRef]

- Mula, S.; Han, T.; Heiser, T.; Lévêque, P.; Leclerc, N.; Srivastava, A.P.; Ruiz-Carretero, A.; Ulrich, G. Hydrogen Bonding as a Supramolecular Tool for Robust OFET Devices. Chem. - A Eur. J. 2019, 25, 8304–8312. [CrossRef]

- Nurazzi, N.M.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Khalina, A.; Abdullah, N.; Sabaruddin, F.A.; Kamarudin, S.H.; Ahmad, S.; Mahat, A.M.; Lee, C.L.; Aisyah, H.A.; et al. Fabrication, Functionalization, and Application of Carbon Nanotube-Reinforced Polymer Composite: An Overview. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13, 1–44. [CrossRef]

- Kida, J.; Aoki, D.; Otsuka, H. Mechanophore Activation Enhanced by Hydrogen Bonding of Diarylurea Motifs: An Efficient Supramolecular Force-Transducing System. Aggregate 2021, 2, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Chen, Z.; Wei, Z.; Tian, L. Hydrophobic Interaction: A Promising Driving Force for the Biomedical Applications of Nucleic Acids. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Kasimova, M.R.; Velázquez-Campoy, A.; Nielsen, H.M. On the Temperature Dependence of Complex Formation between Chitosan and Proteins. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 2534–2543. [CrossRef]

- Esteghlal, S.; Hosseini, S.M.H. Fabrication of Zein/Persian Gum Particles Under the Effect of PH and Protein:Gum Ratio and Investigating Their Physico-Chemical Properties. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 2204–2215. [CrossRef]

- Metilli, L.; Francis, M.; Povey, M.; Lazidis, A.; Marty-Terrade, S.; Ray, J.; Simone, E. Latest Advances in Imaging Techniques for Characterizing Soft, Multiphasic Food Materials. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 279, 102154. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Xu, Z.; Fan, H.; Xu, X.; Pan, S.; Liu, F. Recent Advances in the Effects of Food Microstructure and Matrix Components on the Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104301. [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Lu, T.; Qu, S. Preface to the “Soft Matter Mechanics” Special Issue of Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica. Acta Mech. Solida Sin. 2019, 32, 533–534. [CrossRef]

- Mourdikoudis, S.; Pallares, R.M.; Thanh, N.T.K. Characterization Techniques for Nanoparticles: Comparison and Complementarity upon Studying Nanoparticle Properties. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 12871–12934. [CrossRef]

- Whitesides, G.M.; Boncheva, M. Beyond Molecules: Self-Assembly of Mesoscopic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 4769–4774.

- Gao, Y.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Lin, Y. A Brief Guideline for Studies of Phase-Separated Biomolecular Condensates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 18, 1307–1318. [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Wang, K.; Wu, K.; Corke, H.; Nishinari, K.; Jiang, F. Stability, Microstructure and Rheological Behavior of Konjac Glucomannan-Zein Mixed Systems. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 188, 260–267. [CrossRef]

- Abdelquader, M.M.; Li, S.; Andrews, G.P.; Jones, D.S. Therapeutic Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Comprehensive Review of Their Thermodynamics, Microstructure and Drug Delivery Applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2023, 186, 85–104. [CrossRef]

- Drozłowska, E.; Bartkowiak, A.; Łopusiewicz, Ł. Characterization of Flaxseed Oil Bimodal Emulsions Prepared with Flaxseed Oil Cake Extract Applied as a Natural Emulsifying Agent. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Münzberg, M.; Hass, R.; Dinh Duc Khanh, N.; Reich, O. Limitations of Turbidity Process Probes and Formazine as Their Calibration Standard. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 719–728. [CrossRef]

- Kitchener, B.G.B.; Wainwright, J.; Parsons, A.J. This Is a Repository Copy of A Review of the Principles of Turbidity Measurement. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2017, 41, 620–642.

- Peddie, C.J.; Genoud, C.; Kreshuk, A.; Meechan, K.; Micheva, K.D.; Narayan, K.; Pape, C.; Parton, R.G.; Schieber, N.L.; Schwab, Y.; et al. Volume Electron Microscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2022, 2, 51. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, H.; Hobson, C.M.; Chew, T.L.; Aaron, J.S. Imagining the Future of Optical Microscopy: Everything, Everywhere, All at Once. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Vanossi, A.; Bechinger, C.; Urbakh, M. Structural Lubricity in Soft and Hard Matter Systems. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ranjit, S.; Lanzanò, L.; Libby, A.E.; Gratton, E.; Levi, M. Advances in Fluorescence Microscopy Techniques to Study Kidney Function. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 128–144. [CrossRef]

- Relucenti, M.; Familiari, G.; Donfrancesco, O.; Taurino, M.; Li, X.; Chen, R.; Artini, M.; Papa, R.; Selan, L. Microscopy Methods for Biofilm Imaging: Focus on Sem and VP-SEM Pros and Cons. Biology (Basel). 2021, 10, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Parisse, S.; Petit, J.F.; Forzy, A.; Lecardeur, A.; Beaugrand, S.; Palmas, P. Binder and Interphase Microstructure in a Composite Material Characterized by Scanning Electron Microscopy and NMR Spin Diffusion Experiments. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2020, 221, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zahl, P.; Zhang, Y. Guide for Atomic Force Microscopy Image Analysis to Discriminate Heteroatoms in Aromatic Molecules. Energy and Fuels 2019, 33, 4775–4780. [CrossRef]

- Teshima, H.; Takata, Y.; Takahashi, K. Adsorbed Gas Layers Limit the Mobility of Micropancakes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 115. [CrossRef]

- Berger, C., Premaraj, N., Ravelli, R. B., Knoops, K., López-Iglesias, C., & Peters, P. J. (2023). Cryo-electron tomography on focused ion beam lamellae transforms structural cell biology. Nature Methods, 20(4), 499-511.

- Miranda, K.; Girard-Dias, W.; Attias, M.; de Souza, W.; Ramos, I. Three Dimensional Reconstruction by Electron Microscopy in the Life Sciences: An Introduction for Cell and Tissue Biologists. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2015, 82, 530–547. [CrossRef]

- Vishwanadh, B.; Jo, J.; Bonifacio, C.S.; Wiezorek, J.M.K. Site-Specific Preparation of Plan-View Samples with Large Field of View for Atomic Resolution STEM and TEM Studies of Rapidly Solidified Multi-Phase AlCu Thin Films. Mater. Charact. 2022, 189, 111943. [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Jin, K.; Sun, G.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Liu, L. Microscopy Imaging of Living Cells in Metabolic Engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 752–765. [CrossRef]

- Smisdom, N.; Braeckmans, K.; Deschout, H.; vandeVen, M.; Rigo, J.-M.; De Smedt, S.C.; Ameloot, M. Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching on the Confocal Laser-Scanning Microscope: Generalized Model without Restriction on the Size of the Photobleached Disk. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011, 16, 046021. [CrossRef]

- Knothe, G.; Dunn, R.O. A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Melting Points of Fatty Acids and Esters Determined by Differential Scanning Calorimetry. JAOCS, J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2009, 86, 843–856. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, H.K.; Shi, G. Curing Kinetics Study of Epoxy Resin/Hyperbranched Poly(Amideamine)s System by Non-Isothermal and Isothermal DSC. E-Polymers 2010, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Tamagawa, R.E.; Martins, W.; Derenzo, S.; Bernardo, A.; Rolemberg, M.P.; Carvan, P.; Giulietti, M. Short-Cut Method to Predict the Solubility of Organic Molecules in Aqueous and Nonaqueous Solutions by Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Cryst. Growth Des. 2006, 6, 313–320. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Mcgrath, J.J.; Wang, B. Determination of the Ice Quantity by Quantitative Microscopic Imaging of Vitrification Solutions. 2008, 268, 261–268. [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Wang, H.; Zhao, M.; Xing, J. Purity Determination and Uncertainty Evaluation of Theophylline by Mass Balance Method, High Performance Liquid Chromatography and Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 650, 227–233. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.R.; Dumlu, P.; Vermeir, L.; Lewille, B.; Lesaffer, A.; Dewettinck, K. Rheological Characterization of Gel-in-Oil-in-Gel Type Structured Emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 46, 84–92. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Lu, J.; Sun, Q.; Liu, C.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, R. Evaluation of the IR Biotyper for Klebsiella Pneumoniae Typing and Its Potentials in Hospital Hygiene Management. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 1343–1352. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczuk, D.; Pitucha, M. Application of FTIR Method for the Assessment of Immobilization of Active Substances in the Matrix of Biomedical Materials. Materials (Basel). 2019, 12. [CrossRef]

- Poiana, M.A.; Alexa, E.; Munteanu, M.F.; Gligor, R.; Moigradean, D.; Mateescu, C. Use of ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy to Detect the Changes in Extra Virgin Olive Oil by Adulteration with Soybean Oil and High Temperature Heat Treatment. Open Chem. 2015, 13, 689–698. [CrossRef]

- Amenabar, I.; Poly, S.; Goikoetxea, M.; Nuansing, W.; Lasch, P.; Hillenbrand, R. Hyperspectral Infrared Nanoimaging of Organic Samples Based on Fourier Transform Infrared Nanospectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, Z. Current Trends of Raman Spectroscopy in Clinic Settings: Opportunities and Challenges. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Serebrennikova, K. V.; Berlina, A.N.; Sotnikov, D. V.; Dzantiev, B.B.; Zherdev, A. V. Raman Scattering-Based Biosensing: New Prospects and Opportunities. Biosensors 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, H.; Mehdizadeh, H.; Drapeau, D.; Yoon, S. In-Line Monitoring of Amino Acids in Mammalian Cell Cultures Using Raman Spectroscopy and Multivariate Chemometrics Models. Eng. Life Sci. 2018, 18, 55–61. [CrossRef]

- Iwan W. Schie; Christoph Krafft1; Jürgen Popp. Cell classification with low-resolution Raman spectroscopy (LRRS). J. Biophotonics. 2015, 87, 306–327. [CrossRef]

- Paper, W. Fundamentals of Scanning Electron Microscopy in Life Science Research An Introduction to SEM and the Versatile SEM Techniques Available for Fundamentals of Scanning Electron Microscopy in Life Science Research.

- Inkson, B.J. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for Materials Characterization; Elsevier Ltd, 2016; ISBN 9780081000571.

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yue, W.; Qin, W.; Dong, H.; Vasanthan, T. Nanostructures of Protein-Polysaccharide Complexes or Conjugates for Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 169–196. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J. Photoelectron Spectroscopy: Fundamental Principles and Applications; 2018; ISBN 9783319929552.

- Wang, K.; Taylor, K.G.; Ma, L. Advancing the Application of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) to the Characterization and Quantification of Geological Material Properties. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2021, 247, 103852. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.K.; Wang, Q.Y.; Fitzpatrick, M.E. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) for Materials Characterization; Elsevier Ltd, 2016; ISBN 9780081000571.

- Li, Y.; Zhong, M.; Xie, F.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qi, B. The Effect of PH on the Stabilization and Digestive Characteristics of Soybean Lipophilic Protein Oil-in-Water Emulsions with Hypromellose. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 125579. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhou, M.; Tai, X.; Li, H.; Han, X.; Yu, J. Analytical Transmission Electron Microscopy for Emerging Advanced Materials. Matter 2021, 4, 2309–2339. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhou, Q.; Li, W.; Gao, J.; Liao, X.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, M.; Zhou, Y.; Sui, X.; et al. Influence Mechanism of Wheat Bran Cellulose and Cellulose Nanocrystals on the Storage Stability of Soy Protein Isolate Films: Conformation Modification and Molecular Interaction Perspective. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 139, 108475. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pérez, L.; Madsen, J.; Themistou, E.; Gaitzsch, J.; Messager, L.; Armes, S.P.; Battaglia, G. Nanoscale Detection of Metal-Labeled Copolymers in Patchy Polymersomes. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 2065–2068. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, B.; Guo, S.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z. Droplet Impacting Dynamics: Recent Progress and Future Aspects. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 317, 102919. [CrossRef]

- Aygun, U.; Urey, H.; Yalcin Ozkumur, A. This Technique Enables Direct Detection and Observation of Samples without Perturbing Their Physiological Processes or Physical Structures, a Feature That Has Driven Its Popularity. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- BACHMANN, M.; FIEDERLING, F.; BASTMEYER, M. Practical Limitations of Superresolution Imaging Due to Conventional Sample Preparation Revealed by a Direct Comparison of CLSM, SIM and DSTORM. J. Microsc. 2016, 262, 306–315. [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Jia, Y.; Bai, S.; Li, Q.; Dai, L.; Li, J. The Power of Super-Resolution Microscopy in Modern Biomedical Science. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 314, 102880. [CrossRef]

- Dürrenberger, M.B.; Handschin, S.; Conde-Petit, B.; Escher, F. Visualization of Food Structure by Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM). Lwt 2001, 34, 11–17. [CrossRef]

- Bernewitz, R.; Schmidt, U.S.; Schuchmann, H.P.; Guthausen, G. Structure of and Diffusion in O/W/O Double Emulsions by CLSM and NMR-Comparison with W/O/W. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 458, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Sriprablom, J.; Luangpituksa, P.; Wongkongkatep, J.; Pongtharangkul, T.; Suphantharika, M. Influence of PH and Ionic Strength on the Physical and Rheological Properties and Stability of Whey Protein Stabilized o/w Emulsions Containing Xanthan Gum. J. Food Eng. 2019, 242, 141–152. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wen, C.; Dong, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Janaswamy, S.; Zhu, B.; Song, S. Effect of ε-Polylysine Addition on κ-Carrageenan Gel Properties: Rheology, Water Mobility, Thermal Stability and Microstructure. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 95, 212–218. [CrossRef]

- Frolov, I.N.; Okhotnikova, E.S.; Ziganshin, M.A.; Firsin, A.A. Interpretation of Double-Peak Endotherm on DSC Heating Curves of Bitumen. Energy and Fuels 2020, 34, 3960–3968. [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.; Molitor, P.F.; Schmidt, S.J. Mobility and Stability Characterization of Model Food Systems Using NMR, DSC, and Conidia Germination Techniques. J. Food Sci. 1999, 64, 950–959. [CrossRef]

- Wiechmann, P.; Panwitt, H.; Heyer, H.; Reich, M.; Sander, M.; Kessler, O. Combined Calorimetry, Thermo-Mechanical Analysis and Tensile Test on Welded EN AW-6082 Joints. Materials (Basel). 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Kong, B.; Han, J.; Sun, C.; Li, P. Structure and Antioxidant Activity of Whey Protein Isolate Conjugated with Glucose via the Maillard Reaction under Dry-Heating Conditions. Food Struct. 2014, 1, 145–154. [CrossRef]

- Ptaszek, P. Chapter 5 - Large Amplitude Oscillatory Shear (LAOS) Measurement and Fourier-Transform Rheology: Application to Food. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Ahmed, J., Ptaszek, P., Basu, S.B.T.-A. in F.R. and I.A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing, 2017; pp. 87–123 ISBN 978-0-08-100431-9.

- Yuan, Q.; Lu, X.; Khayat, K.H.; Feys, D.; Shi, C. Small Amplitude Oscillatory Shear Technique to Evaluate Structural Build-up of Cement Paste. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2017, 50, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kimondo, J.J.; Said, R.R.; Wu, J.; Tian, C.; Wu, Z. Mechanical Rheological Model on the Assessment of Elasticity and Viscosity in Tissue Inflammation: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2024, 19, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.N.A.H.; McElhaney, R.N. Membrane Lipid Phase Transitions and Phase Organization Studied by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 2013, 1828, 2347–2358. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, R.; Sugahara, A.; Hagihara, H.; Mizukado, J.; Shinzawa, H. Molecular-Scale Deformation of Polypropylene/Silica Composites Probed by Rheo-Optical Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Imaging Analysis Combined with Disrelation Mapping. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 12160–12167. [CrossRef]

- Osten, J.; Milkereit, B.; Schick, C.; Kessler, O. Dissolution and Precipitation Behaviour during Continuous Heating of Al-Mg-Si Alloys in a Wide Range of Heating Rates. Materials (Basel). 2015, 8, 2830–2848. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ding, W.; Luo, Z.; Loo, B.H.; Yao, J. Probing Single Molecules and Molecular Aggregates: Raman Spectroscopic Advances. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2016, 47, 623–635. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.A.; Prasad, R.V.S. Chapter 2 - Basic Principles of Additive Manufacturing: Different Additive Manufacturing Technologies. In Woodhead Publishing Reviews: Mechanical Engineering Series; Manjaiah, M., Raghavendra, K., Balashanmugam, N., Davim, J.P.B.T.-A.M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing, 2021; pp. 17–35 ISBN 978-0-12-822056-6.

- Niu, F.; Niu, D.; Zhang, H.; Chang, C.; Gu, L.; Su, Y.; Yang, Y. Ovalbumin/Gum Arabic-Stabilized Emulsion: Rheology, Emulsion Characteristics, and Raman Spectroscopic Study. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 607–614. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Popp, J.; Bocklitz, T. Chemometric Analysis in Raman Spectroscopy from Experimental Design to Machine Learning–Based Modeling. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 5426–5459. [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.; Kou, M.; Fan, J.; Pan, W.; Feng, Z.J.; Su, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, W. Structural Characteristics and Rheological Properties of Ovalbumin-Gum Arabic Complex Coacervates. Food Chem. 2018, 260, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Boukhelkhal, I.; Kosinski, P.; Attia, S. Heat and Moisture Transfer Measurement Protocols for Building Envelopes. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Lai, H.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, P.; Li, Y.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y. Slippery Shape Memory Polymer Arrays with Switchable Isotropy/Anisotropy and Its Application as a Reprogrammable Platform for Controllable Droplet Motion. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 403, 126356. [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, D. Sample Presentation, Sources of Error and Future Perspectives on the Application of Vibrational Spectroscopy in the Wine Industry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 861–868. [CrossRef]

- Vu Trung, N.; Pham Thi, N.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, M.N.; Tran Anh, D.; Nguyen Trung, T.; Tran Quang, T.; Than Van, H.; Tran Thi, T. Tuning the Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) with 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid Acting as a Biobased Crosslinking Agent. Polym. J. 2022, 54, 335–343. [CrossRef]

- Andoh, C.N.; Attiogbe, F.; Bonsu Ackerson, N.O.; Antwi, M.; Adu-Boahen, K. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy: An Analytical Technique for Microplastic Identification and Quantification. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 136, 105070. [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, E.; Picken, S.J.; van Esch, J.H. Analysis of Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Determining the Transition Temperatures, and Enthalpy and Heat Capacity Changes in Multicomponent Systems by Analytical Model Fitting. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2023, 148, 12393–12409. [CrossRef]

- Alhede, M.; Qvortrup, K.; Liebrechts, R.; Høiby, N.; Givskov, M.; Bjarnsholt, T. Combination of Microscopic Techniques Reveals a Comprehensive Visual Impression of Biofilm Structure and Composition. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 65, 335–342. [CrossRef]

- Schlafer, S.; Meyer, R.L. Confocal Microscopy Imaging of the Biofilm Matrix. J. Microbiol. Methods 2017, 138, 50–59. [CrossRef]

- Nnyigide, O.S.; Hyun, K. A Comprehensive Review of Food Rheology: Analysis of Experimental, Computational, and Machine Learning Techniques. Korea Aust. Rheol. J. 2023, 35, 279–306. [CrossRef]

- Leblon, B.; Adedipe, O.; Hans, G.; Haddadi, A.; Tsuchikawa, S.; Burger, J.; Stirling, R.; Pirouz, Z.; Groves, K.; Nader, J.; et al. A Review of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy for Monitoring Moisture Content and Density of Solid Wood. For. Chron. 2013, 89, 595–606. [CrossRef]

- Busch, F.; Han, T.; Makowski, M.R.; Truhn, D.; Bressem, K.K.; Adams, L. Integrating Text and Image Analysis: Exploring GPT-4V’s Capabilities in Advanced Radiological Applications Across Subspecialties. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.L.C.; Taylor, J.M.; Davidson, E.C. Design of Soft Matter for Additive Processing. Nat. Synth. 2022, 1, 592–600. [CrossRef]

- Joyner, H.S. Rheology OfSemisolid Foods; 2019; ISBN 9783030271336.

- Robert, A. Revolutionizing the Food Industry with AI and Machine Learning Applications. 2024.

- Ross, J.; Belgodere, B.; Chenthamarakshan, V.; Padhi, I.; Mroueh, Y.; Das, P. Large-Scale Chemical Language Representations Capture Molecular Structure and Properties. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022, 4, 1256–1264. [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Gupta, M. Artificial Intelligence Capability: Conceptualization, Measurement Calibration, and Empirical Study on Its Impact on Organizational Creativity and Firm Performance. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103434. [CrossRef]

- 202 Sullivan, Y.; Fosso Wamba, S. Artificial Intelligence and Adaptive Response to Market Changes: A Strategy to Enhance Firm Performance and Innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 174, 114500. [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.K.; Al Azad, S.; Rahman, M.H.; Farjana, M.; Uddin, M.R.; Dey, D.; Mahmud, S.; Ema, T.I.; Biswas, P.; Anjum, M.; et al. Catabolic Profiling of Selective Enzymes in the Saccharification of Non-Food Lignocellulose Parts of Biomass into Functional Edible Sugars and Bioenergy: An in Silico Bioprospecting. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2022, 9, 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Westlake, J.R.; Tran, M.W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Burrows, A.D.; Xie, M. Biodegradable Active Packaging with Controlled Release: Principles, Progress, and Prospects. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 1166–1183. [CrossRef]

- Hilgendorf, K.; Wang, Y.; Miller, M.J.; Jin, Y.-S. Precision Fermentation for Improving the Quality, Flavor, Safety, and Sustainability of Foods. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2024, 86, 103084. [CrossRef]

- Augustin, M.A.; Hartley, C.J.; Maloney, G.; Tyndall, S. Innovation in Precision Fermentation for Food Ingredients. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 64, 6218–6238. [CrossRef]

- Zahra, A.; Qureshi, R.; Sajjad, M.; Sadak, F.; Nawaz, M.; Khan, H.A.; Uzair, M. Current Advances in Imaging Spectroscopy and Its State-of-the-Art Applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122172. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Pan, D. Spatial Distribution, Compositional Pattern, and Source Apportionment of Colloidal Trace Metals in the Coastal Water of Shandong Peninsula, Northeastern China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 203, 116445. [CrossRef]

- Duong, L.N.K.; Al-Fadhli, M.; Jagtap, S.; Bader, F.; Martindale, W.; Swainson, M.; Paoli, A. A Review of Robotics and Autonomous Systems in the Food Industry: From the Supply Chains Perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 106, 355–364. [CrossRef]

- Terayama, T.; Furukawa, A. Soft Matter Particle Rearrangement in Shear-Thinning. 2024. [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Nano-Enabled Personalized Nutrition: Developing Multicomponent-Bioactive Colloidal Delivery Systems. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 282, 102211. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Park, C.; Kim, M.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, D.S. Advances in Single-Cell Omics and Multiomics for High-Resolution Molecular Profiling. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 515–526. [CrossRef]

- Jabin, A.; Uddin, M.F.; Al Azad, S.; Rahman, A.; Tabassum, F.; Sarker, P.; Morshed, A.K.M.H.; Rahman, S.; Raisa, F.F.; Sakib, M.R.; et al. Target-Specificity of Different Amyrin Subunits in Impeding HCV Influx Mechanism inside the Human Cells Considering the Quantum Tunnel Profiles and Molecular Strings of the CD81 Receptor: A Combined in Silico and in Vivo Study. Silico Pharmacol. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Victoria Obayomi, O.; Folakemi Olaniran, A.; Olugbemiga Owa, S. Unveiling the Role of Functional Foods with Emphasis on Prebiotics and Probiotics in Human Health: A Review. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 119, 106337. [CrossRef]

| Approaches | Processing Parameters |

Protein | Functional effects | Solubility | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal pretreatments | 70–90 °C for 2,4 and 24 h, pH= 6.8 | Skim milk | Lactosylation of whey proteins and caseins improves emulsion thermostability. | Improve its heat stability (containing 17.6% S.M.P., w/w) | [36] |

| 100 °C for 30 min, pH= 6.2 | Soy protein o/w emulsions | Enhanced thermal stability and dispersibility suppress coalescence, flocculation, and creaming. | The emulsions stabilized by 10% (w/v) SPPs | [37] | |

| 100 °C for 30 min, pH=6.0, 6.2 and 6.4 | Soy Proteins | Formulations targeting anti-aggregation, suppressed gelation, reduced viscosity, and enhanced flow behavior | 10% (w/v) suspensions of LCPH-treated SPs | [38] | |

| 80–120 °C for 30 min, pH=7 | Pea protein | Higher pretreatment temperatures reduce protein aggregation via peptide chain rearrangement and diminish intermolecular cross-links | High concentration (15%, w/v) | [39] | |

| 130 °C for 4 h 110 °C for 8 h | Maitake protein | Polysaccharide solubilization enhances extraction and thermal stability | The yield was 3.58% | [40] | |

| Homogenization | High-pressure homogenization (H.P.H) 240 MPa | Whey protein isolate (W.P.I.) and micellar casein dispersions | High homogenization pressure refines particle size, boosts dispersibility and solubility (W.P.I.: 99.5% → 100%, MC: 34% → 99%), and enhances foaming and emulsification | Foaming ability and stability due to the large particle size reduction | [41] |

| H.P.H (25, 50, 75, 100 and 150 MPa) | lentil (Lens culinaris) proteins | Pressure-induced enhancement (75 MPa → 100 MPa) improves solubility (32% → 47%), emulsification, and foaming while reducing viscosity and gelation. | Increasing water solubility with H.P.H., pressure up to 100 MPa | [42] | |

| H.P.H 40, 80, and 120 MPa | Oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion stabilized | Reduced particle size, enhanced zeta potential, and protein restructuring improve solubility (16.5% → 75.1%), emulsification (activity & stability), and apparent viscosity. | Improved solubility (from 16.5% to 75.1%) | [43] | |

| H.P.H 69 MPa combined with hydrogen peroxide | Chicken breast myofibrillar protein | H.P.H. treatment with H₂O₂ enhances thermal stability by blocking free S.H. groups, hindering disulfide formation, and preventing protein denaturation | Exposed hydrophobic groups (from 196.37 to 258.50) of M.M.P. | [43] | |

| H.P.H 50, 100 and150 MPa after 5 passes | Soybean okara | H.P.H. intensity enhancement (11.49% → 90% passes at 150 MPa) refines particle size, boosts solubility, and enhances physical stability, albeit increasing viscosity. | Protein extraction yield (g/100 g) 150 MPa-5 passes 89.69 ± 2.24a | [44] | |

| H.P.H 20–100 MPa for 2 cycles | Oyster ProteinIsolate Hydrolysates | H.P.H. treatment improves protein solubility (22.4% → 39.2%), emulsification, zeta potential, and surface hydrophobicity | High-pressure micro fluidization (120 MPa) | [45] | |

| H.P.H 103 and 207 MPa | Faba bean protein | At pH 7, protein solubility dramatically increases (35% →99%), enhancing interfacial film formation and stability (F.C. & F.S.) due to rapid penetration and adsorption while reducing emulsion creaming index (E.C.I.) | Protein foaming capacity from 91 to 260% after 30 kpsi high-pressure homogenizations,good stability with about 95% | [46] | |

| H.P.H 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 MPa | Mussel (Mytilus edulis) myofibrillar protein | High-pressure homogenization (100 MPa) alters protein conformation (secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures) via particle size reduction, leading to enhanced functionality: solubility (35% → 42%), E.C.I., E.S.I., foam formation, and stability. | Protein solubility and oil holding capacity increased by 7.4% and 1300% at 100 MPa | [47] | |

| Superfine grinding | Ultrafine for 0, 2,4, and 8 h grinding under atm. Pressure, ball zirconia: S.P.I. powder ratio 6:1 | Soybean protein isolate | Extended grinding time reduces particle size, increases surface area and water holding capacity, and improves protein solubility (30% → 40%) and dispersibility. | 2, 4, 6, and 8 h (84.51, 89.4, 88.55, and 82.92 %) were higher than that at 0 h (77.42 %). The average particle size of 137.5 ± 10.7 nm at 8 h | [48] |

| Planetary ball grinding machine with a rotation speed of 200 rpm at room | Pea protein isolate | Micronization refines particle size distribution, enhancing fluidity, water holding capacity (W.H.C.), protein solubility (45.89% → 69.84%), viscosity, and product quality. | Pea protein isolate 69.84 1.37a Water holding capacity 94.67% | [49] | |

| Multidimensional swing high-energy nano-ball-milling | Whey protein concentrate | Micronization reduces particle size to 8 μm, alters protein secondary structure, and elevates gel formation temperature (73.5 °C → 85.6 °C) and water holding capacity. | Increased stability gelation temperature from 73.5 °C to 85.6 °C | [50] | |

| Ultrasound | High-power ultrasound (18.4, 29.58, and 73.95 W/cm2) | Millet protein concentrate | Ultrasonication at higher intensities reduces molecular weight and zeta potential (increases negative surface charge), enhancing protein solubility (60% → 90%), E.A.I., emulsion stability, and foam properties. | Increased the solubility of the native M.P.C. (65.8 ± 0.6%) | [51] |

| High-intensity ultrasound (20 kHz, 400 W) | Soy protein isolate | Ultrasonication (25 min) alters protein structure and weakens interactions, improving soy protein dispersion solubility (38% → 46.3%) and fluidity. | Ultrasound 20 kHz, 80Wcm−2 for 0–25 min | [52] | |

| High-power ultrasound (20 kHz, power density of 0.75 W/ml) | Micellar casein powders | Micronization reduces protein particles to ~1 μm, significantly enhancing solubility (>95%) despite unchanged molecular weight. | 100 °C temperature, concentration of 15% (w/v) | [53] | |

| High-intensity ultrasonication (20 kHz) | Mussel sarcoplasmic proteins | 20-minute ultrasonication enhances protein functionality: solubility (60% → 85%), adsorbed protein, foam properties (formation & stability), emulsification (activity & stability), and generates a homogeneous texture due to particle size reduction. | At 20 kHz, 600W for 20 min was the optimum condition for modification. | [54] |

| Approaches | Chemical | Proteins | Functional effects | Solubility | Refs. | |

| Polysaccharides | Gum Arabic | Pea protein concentrate | Maillard reaction significantly improves protein solubility and other functionalities. | BS-PEF 2 →85.56 ± 1.43a 79.86 | [60] | |

| Persian gum | Whey protein isolate | Solubility increases at pH > pHι > pHϕ₁ due to electrostatic interactions promoting complex solubilization. | Persian gum (1:3, 1:1, 3:1, 6:1, and 9:1% w/w WPI/PG) | [61] | ||

| Gum Arabic and modified starch | Pea protein and soy protein isolates | Electrostatic attraction between positively charged pea protein and negatively charged starch (72.5% increase) enhances pea protein-starch complex solubility at pH 4 | Maximum solubility (72.5%) | [62] | ||

| Xylose/fructose | Soybean protein isolate | Maillard reaction enhances solubility (xylose: 43%, fructose: 59%) | Xylose is more sensitive than fructose | [63] | ||

| Arabinose, sodium alginate, maltodextrin, and lactose | Black rice glutelin | Maillard reaction boosts protein-arabinose complex solubility (pI: 15% → pH 7: 79.61%) via increased hydrophilic character and enhanced protein-water interactions. | Maximum solubility 79.61% at pH 7 | [64] | ||

| High methoxyl pectin | Pea protein isolate | Electrostatic complexation enhanced both pea protein solubility and thermal stability. pH 3.5 mixing ratio decreased from 20:1 to 1:1. | The pH of soluble complexes shifted to pH4.8 mixing ratio increased from 1:1 to 20:1 | [65] | ||

| Polyphenols | Phenolic compounds | Cinnamomum camphora seed kernel protein | High-pressure treatment (up to 100 MPa) enhances protein solubility (pH 3: 23.99%, pH 5: 242.89%) and thermal stability (altered secondary structure, higher unfolding energy) while reducing viscosity and gelation. | The solubility maximum increased by 43.5% | [66] | |

| Gallic acid | Myofibrillar protein | Gallic acid cross-linking enhances protein thermal stability, solubility (40% increase), and colloidal stability by promoting soluble aggregate formation and hindering disulfide bond formation. | Solubility reaches around 90% when 50 μmol/g protein | [67] | ||

| Tea polyphenols | Soybean protein | Polyphenol treatment (0.08 w/v) improves protein solubility (0.258 g/ml) by reducing hydrophobicity and enhancing surface hydrophilicity. | Not Applicable | [66] | ||

| Flaxseed phenolic compounds | Flaxseed protein isolate | Polyphenol binding alters protein secondary structure and masks hydrophobic groups, enhancing solubility. | Increase solubility | [68] | ||

| (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), quercetagetin (Q) and chlorogenic acid (CA) | Zein | Improving thermal stability by rising temperature due to covalent bond formation | Zein thermogram exhibited peaks at 91.5 and 266.6 °C | [69] | ||

| Hydrolyzing enzyme | Different proteolytic enzymes | Pea protein isolates | Acidic pH (4.5) significantly enhances protein solubility (2% → 71%) via structural alterations, the release of hydrophilic moieties, and modified electrostatic interactions, except with chymotrypsin treatment | at pH 4.5 increase the protein solubility | [70] | |

| Papain | Protein hydrolysate obtained from Chinese sturgeon | Pepsin hydrolysis (pH 2-10) enhances protein solubility (max > 98% at pH 6) by liberating soluble peptides from aggregates and increasing charged groups (carboxyl & amine) via hydrolysis | solubilityranged between 86.57% and 98.74% height | [71] | ||

| Trypsin | Rice bran protein | Proteolysis enhances protein solubility and thermal stability by solubilizing peptides from aggregates and increasing ionizable groups | solubility temperatures (30-90 °C) for 30 min | [72] | ||

| Papain | Rice bran protein | Structural modifications enhance protein solubility (>46%) by exposing more polar sites, promoting stronger water interactions | enzyme-papain to get ~15%, 25% and 32% degree of hydrolysis | [73] | ||

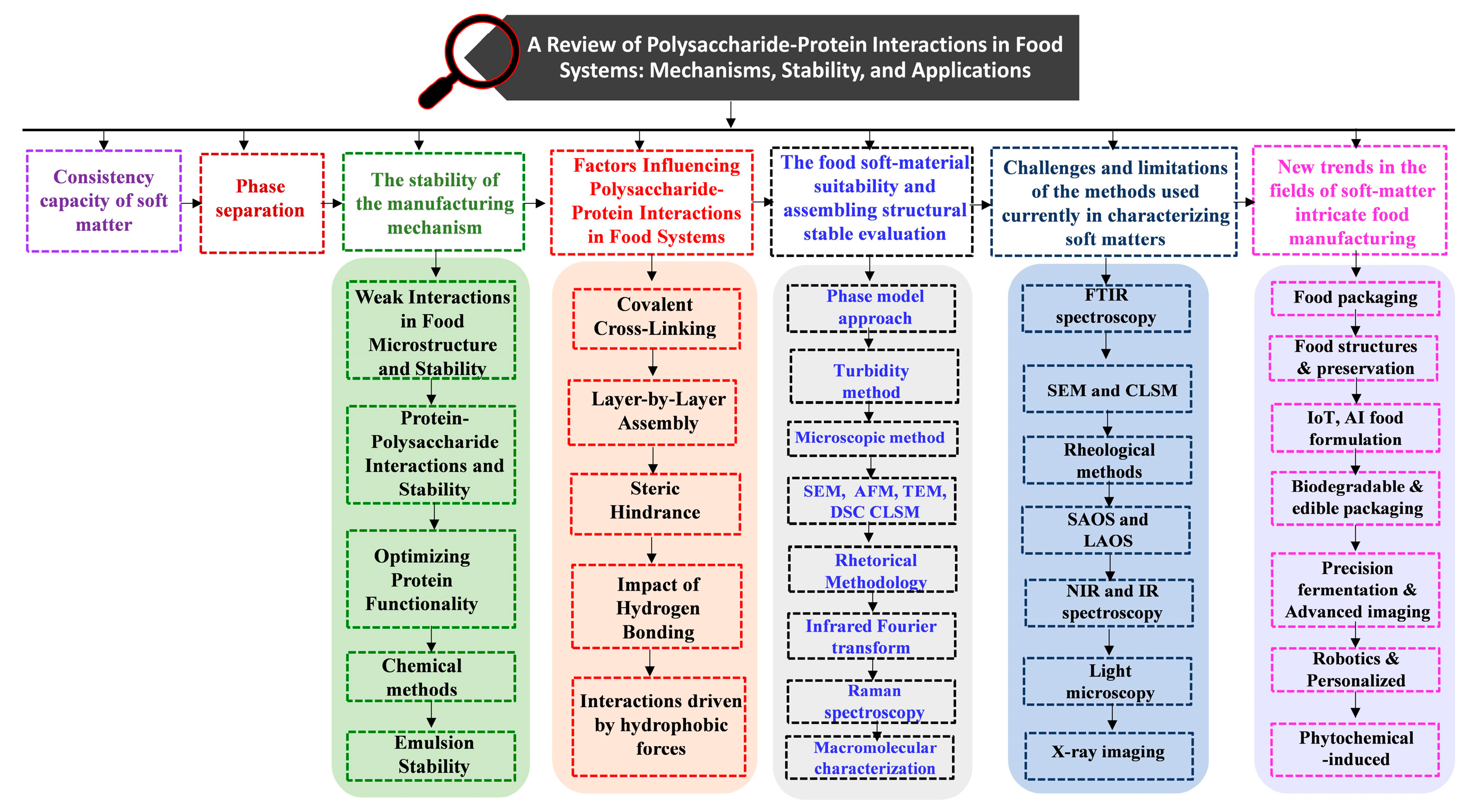

| Equipment | Operating conditions | Advantages | Disadvantages | Comparison | Figure |

| Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) | Electron beam energy, electron beam current, vacuum level, working distance, scan speed, detector configuration, sample preparation | 1. SEM provides detailed surface topography and morphology of samples, allowing for the visualization of fine surface features [129]. 2. SEM can be equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) for elemental analysis of samples 3. SEM offers a considerable depth of field, enabling the imaging of samples with uneven surfaces [130]. |

1. SEM typically requires extensive sample preparation. Including coating with a conductive layer, which can be time-consuming and may introduce artefacts 2. SEM operates under high vacuum, which limits the analysis of samples that are sensitive to vacuum conditions or are non-conductive [129]. |

SEM is advantageous for high-resolution imaging of surface morphology and elemental analysis, while AFM offers high-resolution imaging and manipulation capabilities at the nanoscale. |

SEM |

| Microscope using atomic force (AFM) | Vacuum, air, liquid, Temperature (-196~ 1000 °C), vibrations, acoustic noise, humidity |

1. AFM provides high-resolution surface topography imaging and can measure surface properties such as roughness and adhesion. 2. It allows for the manipulation at the nanoscale, including the positioning of individual atoms and molecules. 3. AFM can operate in air, liquid, and vacuum environments, making it suitable for a wide range [131]. |

1. Conventional AFM has a relatively low imaging rate compared to others such as SEM, TEM 2. AFM images can be complex 3. AFM requires precise calibration, operation, and interpretation [132]. |

Both techniques have unique strengths and limitations, making them complementary tools for nanoscale characterization. |

AFM |

| Utilizing a transmission electron microscope (TEM) | Vacuum, acceleration voltage, beam current, thickness, temperature, magnetic field, vibration isolation | 1. TEM provides high-resolution images, revealing ultrastructural details [133]. 2. TEM analyzes atomic structures and defects at the atomic scale. 3. TEM allows real-time observation of material growth, such as graphene fabrication [134]. |

1. TEM sample preparation can be complex and time-consuming, requiring thin sectioning and staining of samples 2. TEM has a limited field of view, making it challenging to observe large high-resolution areas [135]. |

TEM provides atomic-level resolution, while CLSM enables optical sectioning and live-cell imaging; SEM is ideal for direct imaging and measurements |

TEM |

| Scanning microscope with confocal laser (CLSM) | Laser wavelength, laser power, scan speed, detector gain, light, mounting medium, thickness, temperature, vibration isolation | 1. CLSM provides optical sectioning, allowing for the visualization of samples in three dimensions and the reconstruction of 3D images 2. CLSM is suitable for live-cell imaging, enabling observing dynamic processes in biological samples [136]. |

1. CLSM can cause photo-bleaching of fluorescent dyes, limiting imaging duration and penetration depth, thus restricting its use in thick samples. However, it can perform multiphoton imaging for deep tissue imaging and reduce phototoxicity [137]. | Both techniques have unique strengths and limitations, making them valuable tools for nanoscale characterization and imaging. |

CLSM |

| Scanning differential equations (DSC) | Temperature range, heating/cooling rate, atmosphere, sample mass and preparation, calibration | 1. DSC is utilized to determine melting points and measure solubility in both aqueous and nonaqueous solutions, offering valuable data for materials science research [138]. 2. It is widely employed to study the curing kinetics of materials, offering insights into thermosetting polymers and composite reactions [139]. |

1. DSC’s minimal sample requirement limits specific analyses. 2. Cooling rate limitations in DSC systems impact studying vitrification solutions [140]. 3. Variations in DSC systems affect result interpretation [141]. |

DSC aids in material characterization, solubility measurement, and curing kinetics, while rhetorical methods evaluate parameters for purity assessment and thermodynamic relationships. |

DSC |

| Rhetorical Methodology | Purpose, theoretical framework, type of communication, available evidence | 1. Rhetorical analysis offers a comprehensive view, while solid forms’ temperature reactions reveal transformations and stability [142]. 3. DSC uses the equation for fast and efficient drug purity testing |

1. Not all fields benefit from rhetorical analysis, which may need specialized knowledge for interpretation. 2. Using rhetorical analysis can be tricky due to the complex data |

Both have unique strengths and limitations, making them valuable tools in their fields. |

A single-step procedure employed for emulsion [143] |

| Infrared Fourier transform (FTIR) | State, amount, purge gas, resolution, number of scans, temperature | 1. FTIR reveals the molecular composition of various samples 2. Fast and versatile for identifying and classifying samples, even at the subspecies level [144]. 3. Advanced techniques offer high-resolution analysis at the nanoscale [145] |

1. FTIR results can vary based on sample preparation techniques. [146]. 2. Data analysis requires expertise to interpret spectra [147]. |

FTIR excels in molecular analysis and nanoscale resolution, while Raman offers chemical specificity and non-destructive identification. |

FTIR (Bio Render generated this diagram with some modifications) |

| Raman spectroscopy | Laser wavelength, power, concentration, conditions, resolution, scans, and detection mode | 1. It is noninvasive, requires no sample preparation, and works with aqueous samples, making it versatile [19,20]. 2. Non-destructive, requires minimal prep and works well with liquids like water [150]. |

1. Low signal yield leads to long acquisition times, limiting high-throughput clinical analysis [151]. 2. Fluorescence from some samples can further mask the Raman signal [152] |

Both techniques have unique strengths and limitations, making them valuable molecular analysis and characterization tools. |

Raman spectroscopy Raman spectroscopy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).