Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biopolymer: Properties and Applications

2.1. Types of Biopolymer

2.1.1. Chitosan

2.1.2. Alginate

2.1.3. Hyaluronic Acid

2.1.4. Gelation

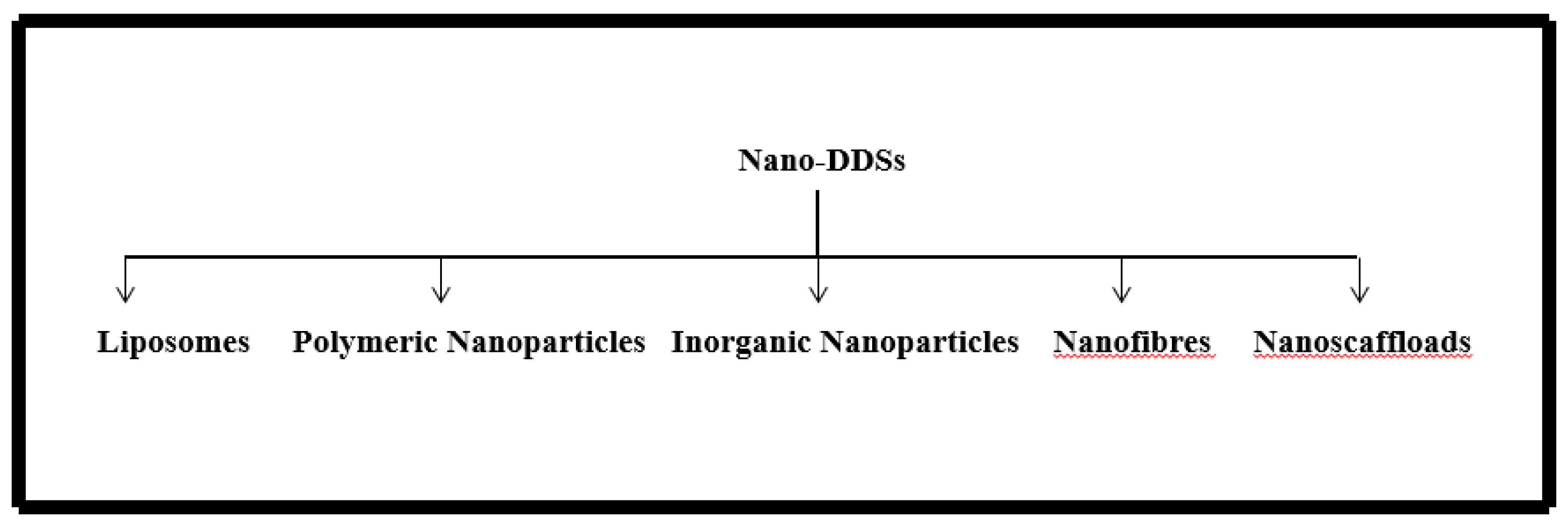

3. Nano Drug Delivery Systems

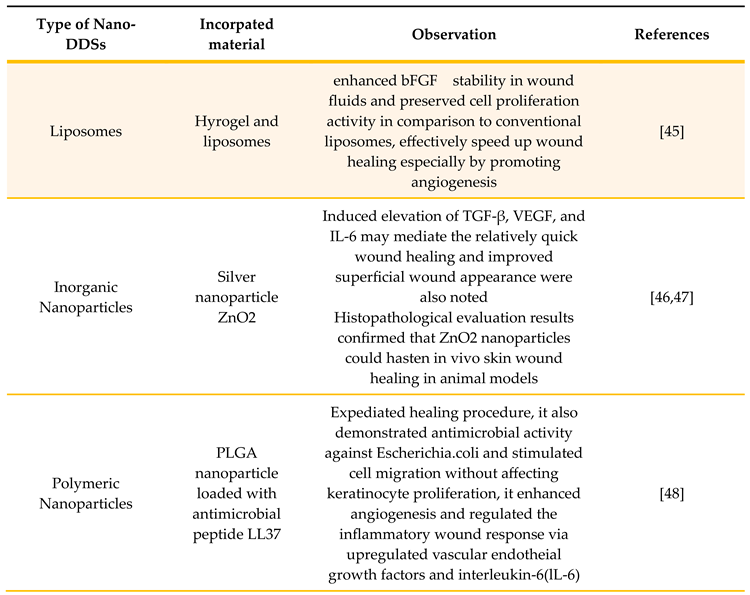

3.1. Liposomes

3.2. Inorganic Nanoparticles

3.3. Polymeric Nanoparticles

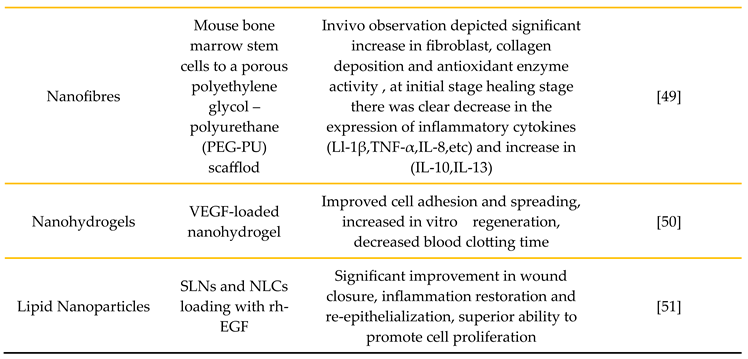

3.4. Nanofibers

3.5. Nanohydrogels

3.6. Lipid Nanoparticles

4. Cancer Treatment and Wound Healing Mechanisms

5. Applications of Biopolymer Based Nanocarriers in Cancer Wound Healing

6. Challenges and Future Prospects

7. Conclusions

References

- Deptuła, M.; Zieliński, J.; Wardowska, A.; Pikuła, M. Wound healing complications in oncological patients: perspectives for cellular therapy. [CrossRef]

- Pikuła, M.; Langa, P.; Kosikowska, P.; Trzonkowski, P. Stem cells and growth factors in wound healing. Postepy Hig Med Dosw 2015, 69, 874–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, J.; Haponiuk, J.T.; Thomas, S.; Gopi, S. Biopolymer based nanomaterials in drug delivery systems: A review. [CrossRef]

- Kukoyi, A.R. Economic impacts of natural polymers, in: O. Olatunji (Ed.),Natural Polymers: Industry Techniques and Applications; Springer: Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewska-Krepsztul, J.; et al. Biopolymers for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications: Recent Advances and Overview of Alginate Electrospinning. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Dean, K.; Li, L. Polymer blends and composites from renewable resources. Progress in Polymer Science 2006, 31, 576–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.K.; Lee, D.I.; Park, J.M. Biopolymer-based microgels/nanogels for drug delivery applications. Progress in Polymer Science 2009, 34, 1261–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uebersax, L.; Merkle, H.P.; Meinel, L. Biopolymer-based growth factor delivery for tissue repair: from natural concepts to engineered systems. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2009, 15, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, N.; Rani, R.; Pahwa, R.; Gupta, M. Biopolymers and treatment strategies for wound healing: an insight view. International Journal of Polymeric Materials and Polymeric Biomaterials 2020, 71, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantes, V. T.; Faraco, A. A.; Ferreira, F. B.; Oliveira, C. A.; Martins-Santos, E.; Cassini-Vieira, P.; Barcelos, L. S.; Ferreira, L. A.; Goulart, G. A. Retinoic Acid-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Surrounded by Chitosan Film Support Diabetic Wound Healing in In Vivo Study. Coll. Surf. B. Biointerf. 2020, 188, 110749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Hasan, N.; Cao, J.; Lee, J.; Hlaing, S. P.; Yoo, J. W. Chitosan-Based Nitric Oxide-Releasing Dressing for Anti-Biofilm and In Vivo Healing Activities in MRSA Biofilm-Infected Wounds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 142, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, H. E.; Zulfakar, M. H.; Ng, S. F. Alginate Based Bilayer Hydrocolloid Films as Potential Slow-Release Modern Wound Dressing. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 434, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; He, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Mei, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, X.; Chen, Z. Encapsulation of Green Tea Polyphenol Nanospheres in PVA/alginate hydrogel for promoting wound healing of diabetic rats by regulating PI3K/AKT pathway. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 110, 110686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.P.; Vidic, J.; Mukherjee, R.; Chang, C.M. Experimental Methods for the Biological Evaluation of Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Risks. Pharmaceutics. 2023, 15, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, R.P.; Mukherjee, R.; Priyadarshini, A.; Gupta, A.; Vibhuti, A.; Leal, E.; Sengupta, U.; Katoch, V.M.; Sharma, P.; Moore, C.E.; Raj, V.S.; Lyu, X. Potential of nanoparticles encapsulated drugs for possible inhibition of the antimicrobial resistance development. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S. N.; Lee, H. J.; Lee, K. H.; Suh, H. Biological Characterization of EDC-Crosslinked Collagen-Hyaluronic Acid Matrix in Dermal Tissue Restoration. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 1631–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuman, M. G.; Nanau, R. M.; Oruña-Sanchez, L.; Coto, G. Hyaluronic Acid and Wound Healing. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 18, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparavigna, A.; Fino, P.; Tenconi, B.; Giordan, N.; Amorosi, V.; Scuderi, N. A New Dermal Filler Made of Cross-Linked and Auto-Cross-Linked Hyaluronic Acid in the Correction of Facial Aging Defects. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2014, 13, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, G.; Guo, B.; Huang, J. Hyaluronan Oligosaccharides Promote Diabetic Wound Healing by Increasing Angiogenesis. Pharmacol. Rep. 2016, 68, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D. S.; Lee, Y.; Ryu, H. A.; Jang, Y.; Lee, K.-M.; Choi, Y.; Choi, W. J.; Lee, M.; Park, K. M.; Park, K. D.; Lee, J. W. Cell Recruiting Chemokine-Loaded Sprayable Gelatin Hydrogel Dressings for Diabetic Wound Healing. Acta Biomater. 2016, 38, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K.; Suzuki, S.; Tabata, Y.; Nishimura, Y. Accelerated Wound Healing through the Incorporation of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor-Impregnated Gelatin Microspheres into Artificial Dermis Using a Pressure-Induced Decubitus Ulcer Model in Genetically Diabetic Mice. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2005, 58, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakura, A.; Tabata, Y.; Tamura, N.; Doi, K.; Nishimura, K.; Nakamura, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Fujita, M.; Komeda, M. Gelatin Sheet Incorporating Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor Enhances Healing of Devascularized Sternum in Diabetic Rats. Circulation 2001, 104, I325–I329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, Z.; Qizilbash, F.F.; Iqubal, M.K. , et al. Nano-based drug delivery system: recent strategies for the treatment of ocular disease and future perspective. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 2019, 13, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainza, G.; Villullas, S.; Pedraz, J.L.; Hernandez, R.M.; Igartua, M. Advances in drug delivery systems (DDSs) to release growth factors for wound heal-ing and skin regeneration. Nanomedicine. 2015, 11, 1551–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, M.; Planell, J.A. Nanotechnology in regenerative medicine. Drug Deliv Syst. 2011, 21, 623–626. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Dhiman, R.; Prudencio, C.R.; da Costa, A.C.; Vibhuti, A.; Leal, E.; Chang, C.M.; Raj, V.S.; Pandey, R.P. Chitosan: Applications in Drug Delivery System. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2023, 23, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Korrapati, P.S.; Karthikeyan, K.; Satish, A.; Krishnaswamy, V.R.; Venugopal, J.R.; Ramakrishna, S. Recent advancements in nanotechnological strategies in selection, design and delivery of biomolecules for skin regeneration. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2016, 67, 747–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.S.; Hussein, S.A.; Ali, A.H.; Korma, S.A.; Lipeng, Q.; Jinghua, C. Liposome: composition, characterisation, preparation, and recent innovation in clinical applications. J Drug Target. 2019, 27, 742–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitragotri, S.; Burke, P.A.; Langer, R. Overcoming the challenges in adminis-tering biopharmaceuticals: formulation and delivery strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degim, Z.; Celebi, N.; Alemdaroglu, C.; Deveci, M.; Ozturk, S.; Ozogul, C. Evalu-ation of chitosan gel containing liposome-loaded epidermal growth factor on burn wound healing. Int Wound J. 2011, 8, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, M.L.; Matricardi, P.; Cencetti, C.; Peris, J.E.; Melis, V.; Carbone, C.; Escribano, E.; Zaru, M.; Fadda, A.M.; Manconi, M. Combination of argan oil and phospholipids for the development of an effective liposome-like formulation able to improve skin hydration and allantoin dermal delivery. Int J Pharm. 2016, 505, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofazzal Jahromi, M.A.; Sahandi Zangabad, P.; Moosavi Basri, S.M.; Sahandi Zangabad, K.; Ghamarypour, A.; Aref, A.R.; Karimi, M.; Hamblin, M.R. Nanomedicine and advanced technologies for burns: preventing infection and facilitating wound healing. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018, 123, 33–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lu, K.j.; Yu, C.; et al. Nano-drug delivery systems in wound treatment and skin regeneration. J Nanobiotechnol 2019, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Fu, X. Naturally derived materials-based cell and drug delivery systems in skin regeneration. J Control Release. 2010, 142, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonifacio, B.V.; Silva, P.B.; Ramos, M.A.; Negri, K.M.; Bauab, T.M.; Chorilli, M. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems and herbal medicines:a review. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Discher, D.E.; Eisenberg, A. Polymer vesicles. Science. 2002, 297, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hromadka, M.; Collins, J.B.; Reed, C.; Han, L.; Kolappa, K.K.; Cairns, B.A.; Andrady, T.; van Aalst, J.A. Nanofber applications for burn care. J Burn Care Res. 2008, 29, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Xie, J.; Liu, W.; Xia, Y. Electrospun nanofibers: new concepts, materials, and applications. Acc Chem Res. 2017, 50, 1976–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, R.; Barhoum, A.; Bechelany, M.; Dufresne, A. Nanofibers for biomedical and healthcare applications. Macromol Biosci. 2019, 19, e1800256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.J.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Ravichandran, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Balamurugan, R.; Sundarrajan, S.; Ramakrishna, S. Nanofbrous structured biome-metic strategies for skin tissue regeneration. Wound Repair Regen. 2013, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocco, I.; Zavan, B.; Bassetto, F.; Vindigni, V. Nanotechnology-based therapies for skin wound regeneration. J Nanomater. 2012, 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Malinen, M.M.; Lauren, P.; Lou, Y.R.; Kuisma, S.W.; Kanninen, L.; Lille, M.; Corlu, A.; Guguen-Guillouzo, C.; Ikkala, O. Nanofbrillar cellulose hydrogel promotes three-dimensional liver cell culture. J Control Release. 2012, 164, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachuau, L. Recent developments in novel drug delivery systems for wound healing. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015, 12, 1895–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anumolu, S.S.; Menjoge, A.R.; Deshmukh, M.; Gerecke, D.; Stein, S.; Laskin, J.; Sinko, P.J. Doxycycline hydrogels with reversible disulfide crosslinks for dermal wound healing of mustard injuries. Biomaterials. 2011, 32, 1204–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajimiri, M.; Shahverdi, S.; Esfandiari, M.A.; Larijani, B.; Atyabi, F.; Rajabiani, A.; Dehpour, A.R.; Amini, M.; Dinarvand, R. Preparation of hydrogel embedded polymer-growth factor conjugated nanoparticles as a diabetic wound dressing. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2015, 42, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzigmann, D.; Kulkarni, J.A.; Leung, J.; Chen, S.; Cullis, P.R.; van der Meel, R. Lipid nanoparticle technology for therapeutic gene regulation in the liver. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020, 159, 344–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, M.L.; Dos Santos, W.M.; de Sousa, A. , et al. Lipid nanoparticles as a skin wound healing drug delivery system: discoveries and advances. Curr Pharm Des. 2020, 26, 4536–4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.L.; Chen, P.P.; ZhuGe, D.L.; Zhu, Q.Y.; Jin, B.H.; Shen, B.X.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, Y.Z. Liposomes with silk fbroin hydrogel core to stabilize bFGF and promote the wound healing of mice with deep second-degree scald. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017, 6, 1700344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Wong, K.K.; Ho, C.M.; Lok, C.N.; Yu, W.Y.; Che, C.M.; Chiu, J.F.; Tam, P.K. Topical delivery of silver nanoparticles promotes wound healing. Chem MedChem. 2007, 2, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Morsy, R.; El-Zawawy, N.A.; Fareed, M.F.; Bedaiwy, M.Y. Synthesized zinc peroxide nanoparticles (ZnO2-NPs): a novel antimicrobial, antielastase, anti-keratinase, and anti-inflammatory approach toward polymicrobial burn wounds. Int J Nanomed. 2017, 12, 6059–6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chereddy, K.K.; Her, C.H.; Comune, M.; Moia, C.; Lopes, A.; Porporato, P.E.; Vanacker, J.; Lam, M.C.; Steinstraesser, L.; Sonveaux, P. PLGA nanoparticles loaded with host defense peptide LL37 promote wound healing. J Control Release. 2014, 194, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geesala, R.; Bar, N.; Dhoke, N.R.; Basak, P.; Das, A. Porous polymer scaffold for on-site delivery of stem cells–protects from oxidative stress and potentiates wound tissue repair. Biomaterials. 2016, 77, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhande, G.; Carrow, J.K.; Thakur, T.; Xavier, J.R.; Parani, M.; Bayless, K.J.; Gaharwar, A.K. Nanoengineered injectable hydrogels for wound healing application. Acta Biomater. 2018, 70, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, Y.; Pandey, R.P.; Dutt, M.; Gupta, A.; Vibhuti, A.; Raj, V.S.; Chang, C.; Priyadarshini, A. Liposomes and phytosomes: Nanocarrier systems and their applications for the delivery of phytoconstituents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 491, 0010–8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunjan, Vidic, J.; Manzano, M.; Raj, V.S.; Pandey, R.P.; Chang, C.M. Comparative meta-analysis of antimicrobial resistance from different food sources along with one health approach in Italy and Thailand. One Health. 2022, 16, 100477.

- Ruby, M.; Gifford, C.C.; Pandey, R.; Raj, V.S.; Sabbisetti, V.S.; Ajay, A.K. Autophagy as a Therapeutic Target for Chronic Kidney Disease and the Roles of TGF-β1 in Autophagy and Kidney Fibrosis. Cells 2023, 12, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainza, G.; Pastor, M.; Aguirre, J.J.; Villullas, S.; Pedraz, J.L.; Hernandez, R.M.; Igartua, M. A novel strategy for the treatment of chronic wounds based on the topical administration of rhEGF-loaded lipid nanoparticles: in vitro bioactivity and in vivo effectiveness in healing-impaired db/db mice. J Control Release. 2014, 185, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, P.; Rani, A.; Hameed, S.; Chandra, S.; Chang, C.-M.; Pandey, R.P. Current Understanding of the Molecular Basis of Spices for the Development of Potential Antimicrobial Medicine. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, H.F. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1986, 315, 1650–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybinski, B.; Franco-Barraza, J.; Cukierman, E. The wound healing, chronic fibrosis, and cancer progression triad. Physiol Genomics. 2014, 46, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsson, V.; Gibbs, D.L.; Brown, S.D.; Wolf, D.; Bortone, D.S.; Ou Yang, T.H. , et al. The Immune landscape of cancer. Immunity. 2018, 48, 812–830.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, H.A.; Zito, P.M. Wound Healing Phases. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing (2019).

- Ellis, S.; Lin, E.J.; Tartar, D. Immunology of Wound Healing. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2018, 7, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.S. Nanomaterials for cancer therapy; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, M. Cancer nanotechnology: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Cancer 2005, 5, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himanshu RPrudencio, C.; da Costa, A.C.; Leal, E.; Chang, C.M.; Pandey, R.P. Systematic Surveillance and Meta-Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance and Food Sources from China and the USA. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanocarriers for cancer-targeted drug delivery, Preeti Kumari, Balaram Ghosh, and Swati Biswas. [CrossRef]

- Serpe, L. Conventional chemotherapeutic drug nanoparticles for cancer treatment. Nanotechnol Life Sci 2006, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullotti, E.; Yeo, Y. Extracellularly activated nanocarriers: a new paradigm of tumor targeted drug delivery. Mol Pharm 2009, 6, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozawa, M.G.; Zurita, A.J.; Dias-Neto, E. , et al. Beyond receptor expression levels: the relevance of target accessibility in ligand directed pharma codelivery systems. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2008, 18, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdan, S.; Pastar, I.; Drakulich, S.; Dikici, E.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Deo, S.; Daunert, S. Nanotechnology-driven therapeutic interventions in wound healing: potential uses and applications. ACS Cent Sci 2017, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahana, T.G.; Rekha, P.D. Biopolymers: Applications in wound healing and skin tissue engineering Molecular Biology Reports. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Park, J.Y.; Kang, H.J.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J. Fucoidan/FGF-2 induces angiogenesis through JNK- and p38-mediated activation of AKT/MMP-2 signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014, 450, 1333–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, R.; Rerek, M.; Wood, E.J. Fucoidan modulates the effect of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 on fibroblast proliferation and wound repopulation in in vitro models of dermal wound repair. Biol Pharm Bull 2004, 27, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalej, H.; Moalla, D.; Boisset, C.; Bardaa, S.; Ayed, H.B.; Sahnoun, Z.; Rebai, T.; Nasri, M.; Hmidet, N. Rhelogical, dermal wound healing and in vitro antioxidant properties of exopolysaccharide hydrogel from Pseudomonas stutzeri AS22. Colloids Surf B 2014, 123, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, P.; Arun, A.B.; Ashwini, P.; Rekha, P.D. Functional and cell proliferative properties of an exopolysaccharide produced by Nitratireductor sp. PRIM-31. Int J Biol Macromol 2016, 85, 400–404. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, R.P.; Nascimento, M.S.; Franco, C.H.; Bortoluci, K.; Silva, M.N.; Zingales, B.; Gibaldi, D.; Castaño Barrios, L.; Lannes-Vieira, J.; Cariste, L.M.; Vasconcelos, J.R.; Moraes, C.B.; Freitas-Junior, L.H.; Kalil, J.; Alcântara, L.; Cunha-Neto, E. Drug Repurposing in Chagas Disease: Chloroquine Potentiates Benznidazole Activity against Trypanosoma cruzi In Vitro and In Vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0028422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, P.; Arun, A.B.; Ashwini, P.; Rekha, P.D. Versatile properties of an exopolysaccharide R-PS18 produced by Rhizobium sp. PRIM-18. Carbohydr Polym 2015, 126, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Ye, M.; Du, Z.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L. Purification, characterization and promoting effect on wound healing of an exopolysaccharide from Lachnum YM405. Carbohydr Polym 2014, 105, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, R.P.; Mukherjee, R.; Chang, C.M. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance system mapping in different countries. Drug Target Insights. 2022, 16, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey RP, Gunjan, Himanshu, Mukherjee R, Chang CM. Nanocarrier-mediated probiotic delivery: a systematic meta-analysis assessing the biological effects. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, Y.; Pandey, R.P.; Dutt, M.; Gupta, A.; Vibhuti, A.; Raj, V.S.; Chang, C.-M.; Priyadarshini, A. Silver Nanoparticles Phytofabricated through Azadirachta indica: Anticancer, Apoptotic, and Wound-Healing Properties. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanova, F.; Milagres, F.A.P.; Brustulin, R.; Araújo, E.L.L.; Pandey, R.P.; Raj, V.S.; Deng, X.; Delwart, E.; Luchs, A.; Costa, A.C.D.; Leal, É. A New Circular Single-Stranded DNA Virus Related with Howler Monkey Associated Porprismacovirus 1 Detected in Children with Acute Gastroenteritis. Viruses 2022, 14, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himanshu, Mukherjee R, Vidic J, Leal E, da Costa AC, Prudencio CR, Raj VS, Chang CM, Pandey RP. Nanobiotics and the One Health Approach: Boosting the Fight against Antimicrobial Resistance at the Nanoscale. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, E.D.S.F.; Rosa, U.A.; Ribeiro, G.O.; Villanova, F.; Milagres, F.A.P.; Brustulin, R.; Morais, V.D.S.; Araújo, E.L.L.; Pandey, R.P.; Raj, V.S.; Sabino, E.C.; Deng, X.; Delwart, E.; Luchs, A.; Leal, É.; da Costa, A.C. Multiple clades of Husavirus in South America revealed by next generation sequencing. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0248486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).