Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Previous Research in the Field

1.2. Current Study Novelty and Focus

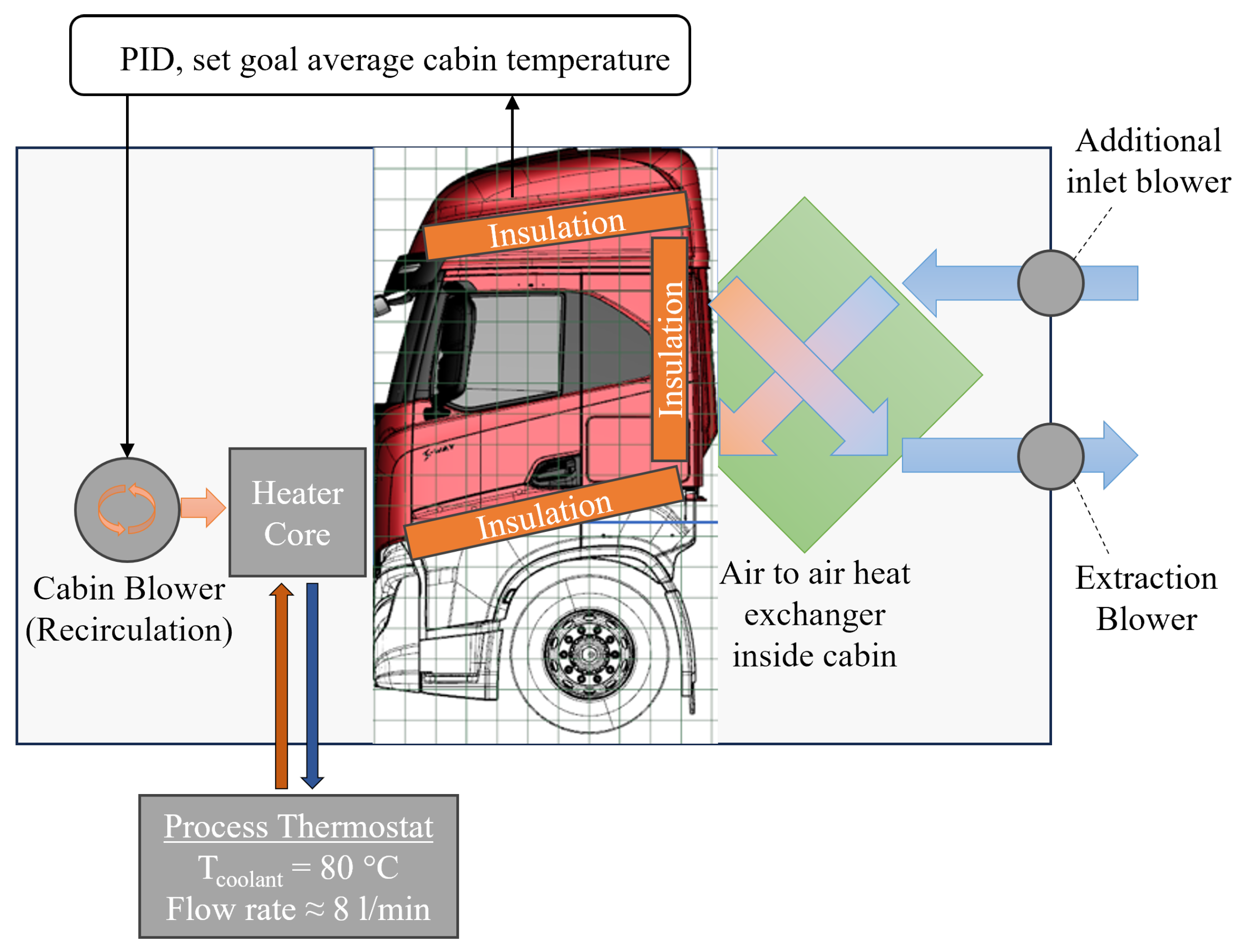

- We use an air-air heat exchanger that reuses the thermal energy from the conditioned air that leaves the cabin to pre-heat the fresh air that will be blown into the cabin. This approach allows us to use sufficient fresh air to keep the C concentration within the cabin at a feasible level while, at the same time, keeping the energy consumption low.

- In addition, to mitigate also the thermal losses through the walls, we apply a thermal insulation to the cabin. This measure additionally enhances the thermal performance of the truck cabin and, hence, it further reduces the energy consumption of the HVAC system.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

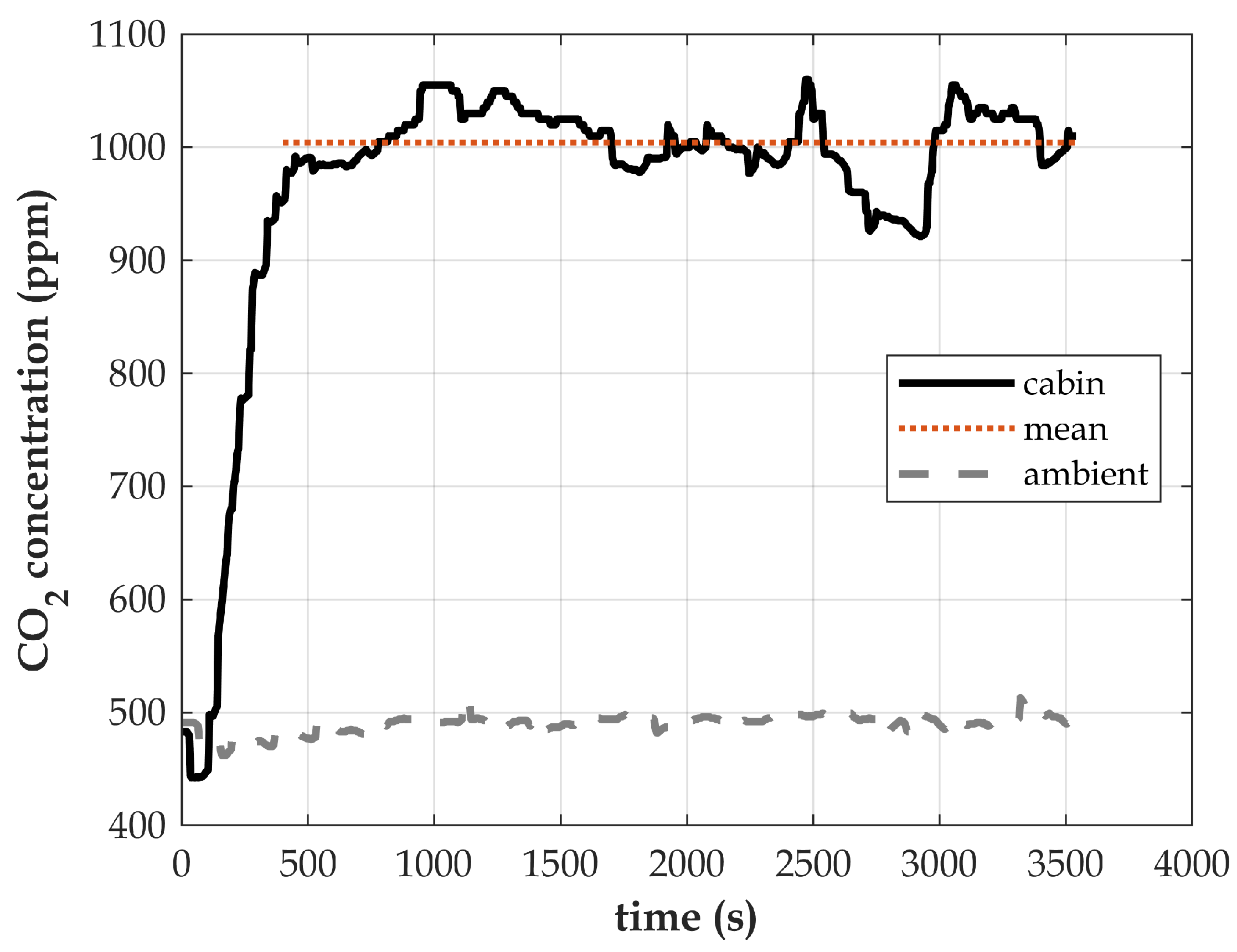

3.1. C Concentration

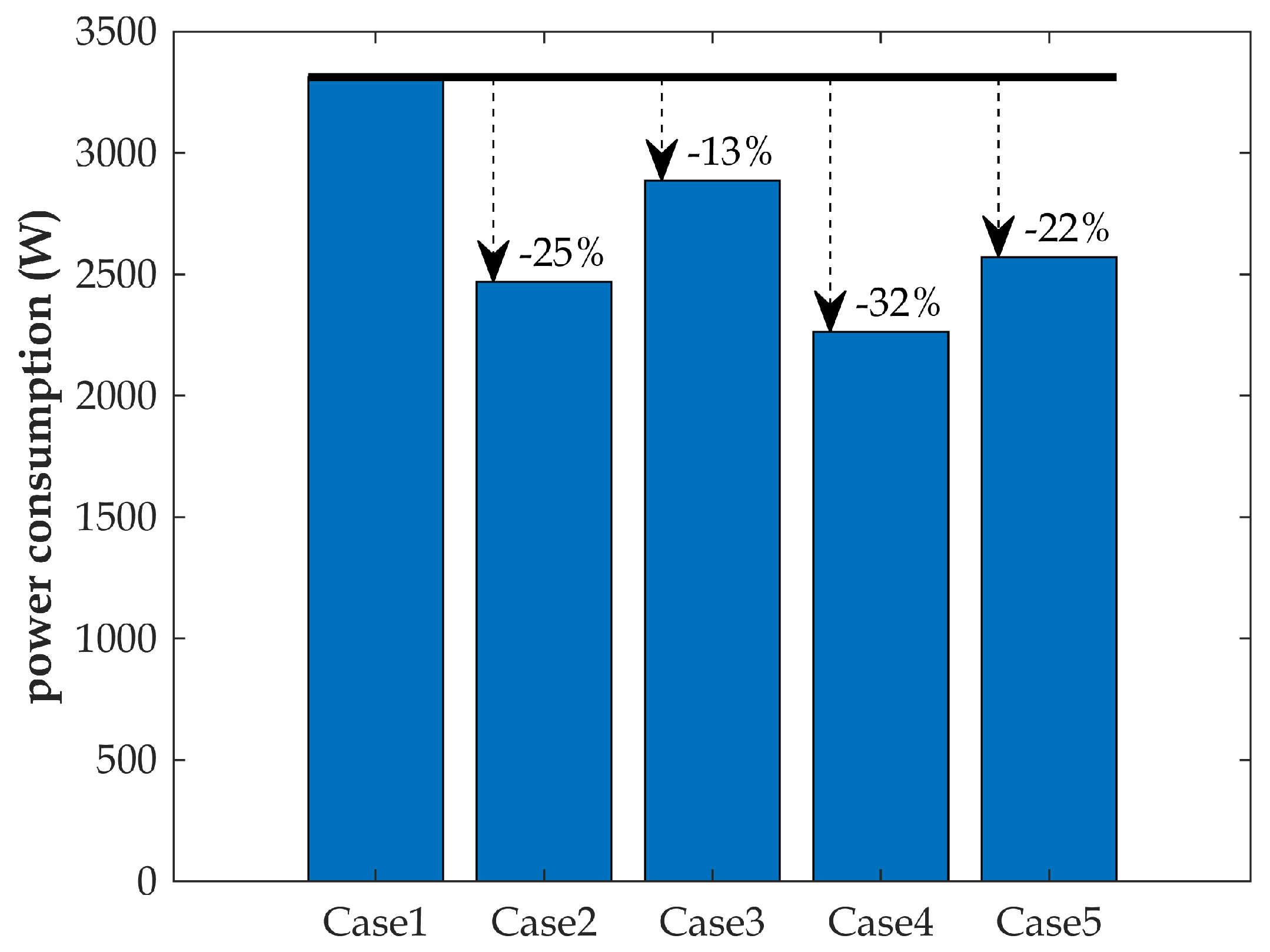

3.2. Power Demand for Heating

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASHRAE | American society of heating, refrigerating and air-conditioning engineers |

| BEV | Battery electric vehicle |

| C | Carbon dioxide |

| HVAC | Heating, ventilation and air-conditioning |

| OEM | Original equipment manufacturer |

| PID | Proportional–integral–derivative controller |

References

- European Union. The European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 05.11.2024).

- Gellai, I.; Popovac, M.; Kardos, M.; Simic, D. Numerical analysis of the energy efficiency measures for improving the truck cabin thermal performance. Engineering Modelling, Analysis and Simulation 2024, 2, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Heß, L.; Dimova, D.; Piechalski, J.W.; Rusche, S.; Best, P.; Sonnekalb, M. Analysis of the Specific Energy Consumption of Battery-Driven Electrical Buses for Heating and Cooling in Dependence on the Technical Equipment and Operating Conditions. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Cigarini, F.; Fay, T.A.; Artemenko, N.; Göhlich, D. Modeling and experimental investigation of thermal comfort and energy consumption in a battery electric bus. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2021, 12, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Moll, C.; Plötz, P.; Hadwich, K.; Wietschel, M. Are battery-electric trucks for 24-hour delivery the future of city logistics?-A german case study. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Göhlich, D.; Ly, T.A.; Kunith, A.; Jefferies, D. Economic assessment of different air-conditioning and heating systems for electric city buses based on comprehensive energetic simulations. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2015, 7, 398–406. [CrossRef]

- Steinstraeter, M.; Heinrich, T.; Lienkamp, M. Effect of low temperature on electric vehicle range. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, D.; Basciotti, D.; Gellai, I. Demand-based control design for efficient heat pump operation of electric vehicles. Energies 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lajunen, A.; Yang, Y.; Emadi, A. Review of Cabin Thermal Management for Electrified Passenger Vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2020, 69, 6025–6040. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Brewer, E.; Pham, L.; Jung, H. Reducing mobile air conditioner (MAC) power consumption using active cabin-air-recirculation in a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV). World Electric Vehicle Journal 2018, 9, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Schutzeich, P.; Pischinger, S.; Hemkemeyer, D.; Franke, K.; Hamelbeck, P. A Predictive Cabin Conditioning Strategy for Battery Electric Vehicles. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.C.; Kamarudin, L.M.; Shukri, S.; Abdullah, N.S.; Zakaria, A. Monitoring of carbon dioxide (CO2) accumulation in vehicle cabin. 2016 3rd International Conference on Electronic Design, ICED 2016 2016, pp. 427–432. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H. Modeling CO2 concentrations in vehicle cabin. SAE Technical Papers 2013, 2, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Nielsen, F.; Karlsson, H.; Ekberg, L.; Dalenbäck, J.O. Vehicle cabin air quality: influence of air recirculation on energy use, particles, and CO2. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 43387–43402. [CrossRef]

- Persily, A.; Bahnfleth, W.P.; Kipen, H.; Lau, J.; Mandin, C.; Sekhar, C.; Wargocki, P.; Weekes, L.C.N. ASHRAE Position Document on Indoor Carbon Dioxide 2022.

- Persily, A.; de Jonge, L. Carbon dioxide generation rates for building occupants. Indoor Air 2017, 27, 868–879. [CrossRef]

- The Engineering ToolBox. Ethylene Glycol Heat-Transfer Fluid Properties. Available online: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/ethylene-glycol-d_146.html (accessed on 20.11.2024).

| Case1 | Case2 | Case3 | Case4 | Case5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved insulation | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Recirculation mode | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Air-air heat exchanger | No | No | No | No | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).