Submitted:

01 December 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

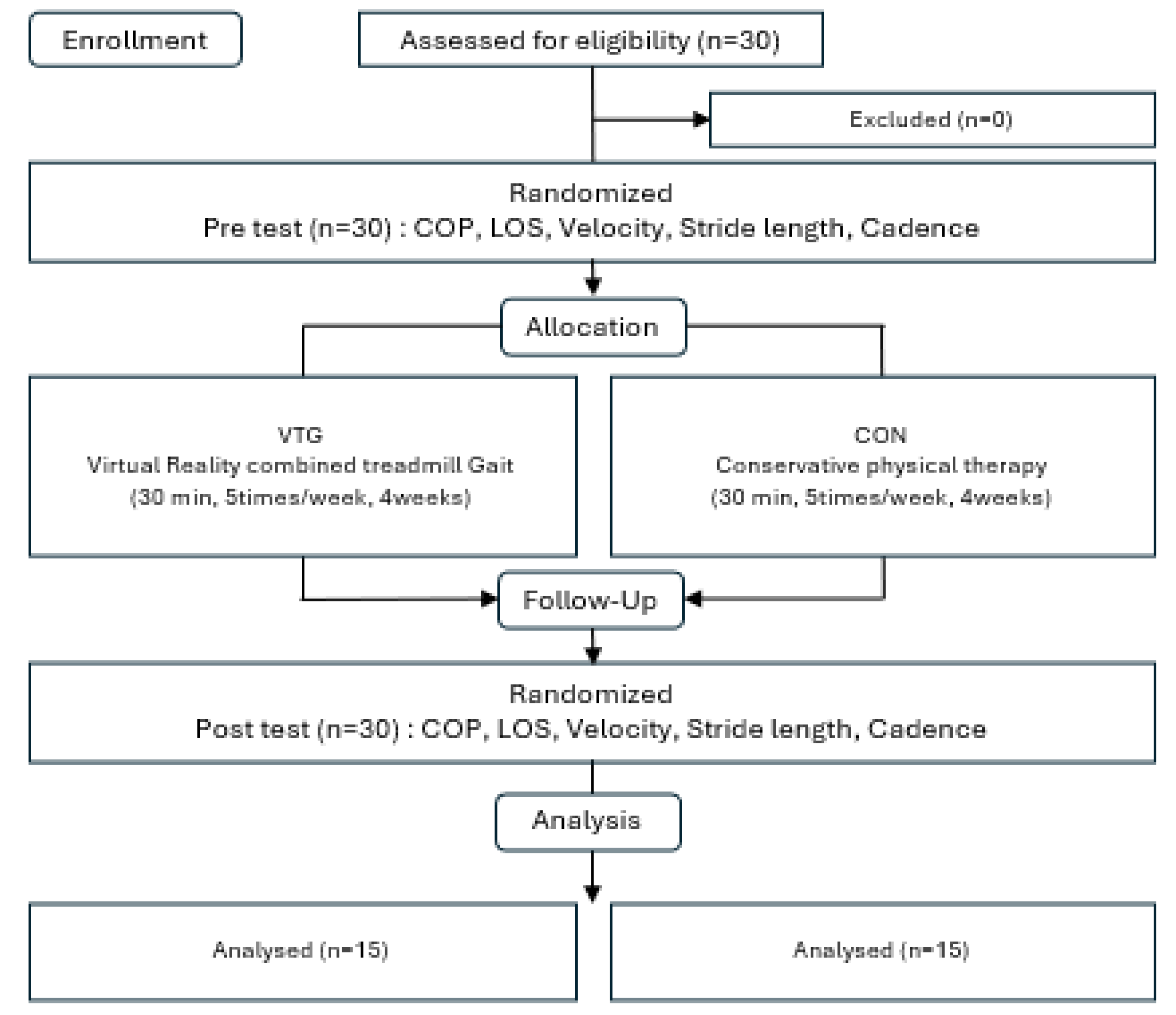

BACKGROUND: In this study aims to investigate the changes in balance and walking by applying virtual reality combined with treadmill gait training to children with spastic cerebral palsy. OBJECTIVE: Thirty patients with children with spastic cerebral palsy were randomly divided into two groups. The experiment group had a virtual reality combined treadmill gait training program group. The control group had a general physiotherapy group. METHODS: Prior to the initiation of this study. Patients’ balance ability was assessed using the Bio-rescue (Center of Pressure; COP, Limit of Stability; LOS). velocity, stride length, cadence was measured to examine gait ability. RESULT: After the intervention, the experimental group showed a significant increase in COP and LOS values compared to the control group. Regarding gait ability, the experimental group showed significant increases in velocity, step length, and cadence post-intervention compared to pre-intervention scores, with differences significantly higher than those of the control group. CONCULSION: The conclusion of this study may be used as a basic material for an effective Virtual Reality Com-bined Treadmill Gait Training method for children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy and have significance as an intervention for Children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy patients requiring long-term treatment.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participations

2.2. Design

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Virtual Reality Combined Treadmill Gait Training (VTG) Group

2.3.2. Conservative Treatment (CON) Group

2.4. Evaluation

2.4.1. Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS)

2.4.2. Balance Test

2.4.3. Gait Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients

3.2. Changes in Balance Ability Before and After Intervention

3.3. Changes in Walking Ability Before and After Intervention

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bax, M.; Goldstein, M.; Rosenbaum, P.; Leviton, A.; Paneth, N.; Dan, B. Proposed definition and classification of cerebral palsy, April 2005. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2005, 47, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’SHEA, T.M. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cerebral palsy. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2008, 51, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woollacott, M.H.; Shumway-Cook, A. Postural dysfunction during standing and walking in children with cerebral palsy: what are the underlying problems and what new therapies might improve balance? Neural plasticity. 2005, 12, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krigger, K.W. Cerebral palsy: an overview. American family physician. 2006, 73, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shikako-Thomas, K.; Dahan-Oliel, N.; Shevell, M.; Law, M.; Birnbaum, R.; Rosenbaum, P. Play and be happy? Leisure participation and quality of life in school-aged children with cerebral palsy. International journal of pediatrics. 2012, (1), 387280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.L.; Walter, S.D.; Hanna, S.E.; Palisano, R.J.; Russell, D.J.; Raina, P. Prognosis for gross motor function in cerebral palsy: Creation of motor development curves. Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 2003, 58, 166–168. [Google Scholar]

- Winters, T.; Gage, J.; Hicks, R. Gait patterns in spastic hemiplegia in children and young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987, 69, 437–441. [Google Scholar]

- Bertoti, D.B.; Gross, A.L. Evaluation of biofeedback seat insert for improving active sitting posture in children with cerebral palsy: A clinical report. Physical therapy. 1988, 68, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketelaar, M.; Vermeer, A.; Hart, H. T. ’ van Petegem-van Beek, E.; Helders, P. J. Effects of a functional therapy program on motor abilities of children with cerebral palsy. Physical therapy. 2001, 81, 1534–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; Reid, D. The influence of virtual reality play on children’s motivation. Canadian journal of occupational therapy. 2005, 72, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNevin, N.H.; Coraci, L.; Schafer, J. Gait in adolescent cerebral palsy: the effect of partial unweighting. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2000, 81, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindl, M.R.; Forstner, C,; Kern, H. ; Hesse, S. Treadmill training with partial body weight support in nonambulatory patients with cerebral palsy. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2000, 81, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, C.L.; Malouin, F.; Dumas, F.; Marcoux, S.; Lepage, C.; Menier, C. Early and intensive treadmill locomotor training for young children with cerebral palsy: a feasibility study. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 1997, 9, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdea, G.C.; Cioi, D.; Kale, A.; Janes, W.E.; Ross, S.A.; Engsberg, J.R. Robotics and gaming to improve ankle strength, motor control, and function in children with cerebral palsy—a case study series. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering. 2012, 21, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveistrup, H.; Thornton, M.; Bryanton, C.; McComas, J.; Marshall, S.; Finestone, H. Outcomes of intervention programs using flatscreen virtual reality. The 26th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Vol. 2. IEEE, 2004.

- Flynn, S.; Palma, P.; Bender, A. Feasibility of using the Sony PlayStation 2 gaming platform for an individual poststroke: a case report. Journal of neurologic physical therapy. 2007, 31, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D, Rose, F. ; Brooks, B.; Attree, E.; Parslow, D.; Leadbetter, A.; McNeil, J. A preliminary investigation into the use of virtual environments in memory retraining after vascular brain injury: indications for future strategy? Disability and rehabilitation. 1999, 21, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, P.L.; Rand, D.; Katz, N.; Kizony, R. Video capture virtual reality as a flexible and effective rehabilitation tool. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation. 2004, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, M.K. Virtual environments for motor rehabilitation. Cyberpsychology & behavior. 2005, 8, 187–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.; Kwon, Y. Therapeutic virtual reality program in chronic stroke patients recovery of upper extremity and neuronal reorganization. Journal of special education & rehabilitation science. 2005, 44, 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, W.S.; Song, C.H. Effects of virtual reality-based exercise on static balance and gait abilities in chronic stroke. The Journal of Korean Physical Therapy. 2009, 21, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.H.; Ko. J.Y. Evaluation of balance and activities of daily living in children with spastic cerebral palsy using virtual reality program with electronic games. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association. 2010, 10, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y.K.; Hwang, J.H.; Kim, N.G. Assessments of Static Balance Using Virtual Moving Surround. Journal of the Korean Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2006, 30, 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Go, J. Effects of virtual reality based exercise program on gross motor function and balance of children with spastic cerebral palsy. Journal of The Korean Society of Integrative Medicine. 2016, 4, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jelsma, J.; Pronk, M.; Ferguson, G.; Jelsma-Smit, D. The effect of the Nintendo Wii Fit on balance control and gross motor function of children with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Developmental neurorehabilitation. 2013, 16, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.S.; Lee, D.Y.; Lee, S.W. The effects of rehabilitation exercise using a home video game (PS2) on gait ability of chronic stroke patients. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society. 2010, 11, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesar, T.M.; Reisman, D.S.; Perumal, R.; Jancosko, A.M.; Higginson, J.S.; Rudolph, K.S. Combined effects of fast treadmill walking and functional electrical stimulation on post-stroke gait. Gait & posture. 2011, 33, 309–313. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, D.K.; Oh, D.W.; Lee, S.H. Effectiveness of ankle visuoperceptual-feedback training on balance and gait functions in hemiparetic patients. The Journal of Korean Physical Therapy. 2010, 22, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Alshryda, S.; Wright, J. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Classic papers in orthopaedics. London: Springer London. 2013,575-577.

- Østensjø, S.; Carlberg, E.B.; Vøllestad, N.K. Motor impairments in young children with cerebral palsy: relationship to gross motor function and everyday activities. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2004, 46, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latash, M.L.; Ferreira, S.S.; Wieczorek, S.A. Duarte M. Movement sway: changes in postural sway during voluntary shifts of the center of pressure. Experimental brain research. 2003, 150, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Chu, H.; Park, C.; Kang, G.H.; Seo, J.; Sung, K.K. Comparison of recovery patterns of gait patterns according to the paralyzed side in Korean stroke patients: Protocol for a retrospective chart review. Medicine. 2018, 97, e12095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Smuck, M.; Legault, C.; Ith, M.A.; Muaremi, A.; Aminian, K. Gait symmetry assessment with a low back 3d accelerometer in post-stroke patients. Sensors. 2018, 18, 3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilson, J.K.; Sullivan, K.J.; Cen, S.Y.; Rose, D.K.; Koradia, C.H.; Azen, S.P. Meaningful gait speed improvement during the first 60 days poststroke: minimal clinically important difference. Physical therapy. 2010, 90, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, D.; Boian, R.; Merians, A.S.; Tremaine, M.; Burdea, G.C.; Adamovich, S.V. Virtual reality-enhanced stroke rehabilitation. IEEE transactions on neural systems and rehabilitation engineering. 2001, 9, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketelaar, M.; Vermeer, A.; Hart, Ht.; van Petegem-van Beek, E.; Helders, P.J. Effects of a functional therapy program on motor abilities of children with cerebral palsy. Physical therapy. 2001, 81, 1534–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, J.A.; Fox, E.J.; Lowe, J.; Swales, H.B.; Behrman, A.L. Locomotor training with partial body weight support on a treadmill in a nonambulatory child with spastic tetraplegic cerebral palsy: a case report. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2004, 16, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merians, A.; Tunik, E.; Fluet, G.; Qiu, Q.; Adamovich, S. Innovative approaches to the rehabilitation of upper extremity hemiparesis using virtual environments. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2009, 45, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Tossavainen, T.; Juhola, M.; Pyykkö, I.; Aalto, H.; Toppila, E. Development of virtual reality stimuli for force platform posturography. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2003, 70(2-3), 277-283.

- Lee, H.S.; Choi, H.S.; Kwon, O.Y. A literature review on balance control factors. Physical Therapy Korea. 1996, 3, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, C.; Hwang, W.; Hwang, S.; Chung, Y. Treadmill training with virtual reality improves gait, balance, and muscle strength in children with cerebral palsy. The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine. 2016, 238, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; Reid, D. The influence of virtual reality play on children’s motivation. Canadian journal of occupational therapy. 2005, 72, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuzer, G.; Senel, A.; Atay, M.; Stam, H. Playstation eyetoy games” improve upper extremity-related motor functioning in subacute stroke: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2008, 44, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bisson, E.; Contant, B.; Sveistrup, H.; Lajoie, Y. Functional balance and dual-task reaction times in older adults are improved by virtual reality and biofeedback training. Cyberpsychology & behavior. 2007, 10, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, E.S.; Kraemer, D.J.; Hamilton, A.F.D.C.; Kelley, W.M.; Grafton, S.T. Sensitivity of the action observation network to physical and observational learning. Cerebral cortex. 2009, 19, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.H.; Jang, S.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Hallett, M.; Ahn, S.H.; Kwon, Y.H. Virtual reality–induced cortical reorganization and associated locomotor recovery in chronic stroke: an experimenter-blind randomized study. Stroke. 2005, 36, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | VGT group (n = 15) | CON group (n = 15) | t/x2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 6 (40.0%) | 8 (53.3%) | 0.464 | 0.715 |

| Female | 9 (60.0%) | 7 (46.7%) | ||

| GMFM | 0.464 | 0.715 | ||

| GMFM Ⅰ | 9 (60.0%) | 7 (46.7%) | ||

| GMFM Ⅱ | 6 (40.0%) | 8 (53.3%) | ||

| Paralysis type | 0.136 | 1.000 | ||

| Hemiplegia | 6 (40.0%) | 7 (46.7%) | ||

| Diplegia | 9 (60.0%) | 8 (53.3%) | ||

| Age (years) | 11.60±1.95a | 11.33±1.87 | 0.381 | .706b |

| Height (㎝) | 137.60±10.01 | 142.27±9.27 | -1.325 | .196b |

| Weight (kg) | 37.67±8.47 | 38.00±8.28 | -0.371 | .714b |

| VTG (n=15) | CON (n=15) | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COP (㎝) | pre | 12.98±2.64 | 12.74±2.94 | 0.231 | .505 |

| post | 10.56±2.46 | 11.43±2.94 | |||

| change | -2.42±1.19* | -1.31±0.72* | -3.110 | .004 | |

| LOS (㎠) | pre | 5599.43±902.35 | 5488.25±1028.22 | 0.315 | .198 |

| post | 7635.41±1289.58 | 8009.86±1387.06 | |||

| change | 2035.97±638.79* | 2521.61±491.99* | -2.310 | .028 | |

| VTG (n=15) | CON (n=15) | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity (m/s) | pre | 2.50±.35 | 2.50±.31 | 4.055 | .957 |

| post | 2.89±.36 | 2.60±.37 | |||

| change | .39±.22* | .10±.12* | 4.379 | .000 | |

| Step length (㎝) | pre | 95.38±2.64 | 95.11±2.07 | 0.305 | .763 |

| post | 101.53±1.09 | 96.72±2.45 | |||

| change | 6.15±2.95* | 1.61±1.80* | 5.087 | .000 | |

| Cadence (times/min) | pre | 100.99±4.59 | 98.6±3.06 | 1.681 | .104 |

| post | 110.10±4.37 | 103.26±3.10 | |||

| change | 10.00±6.70* | 4.67±3.09 | 2.801 | .009 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).