1. Introduction

Currently, measures aimed at reducing antibiotic consumption and controlling the use of antibacterial therapy is considered the most effective strategy for overcoming bacterial resistance to antimicrobial drugs [

1]. This approach makes it possible to limit the spread of existing antibiotic resistance mechanisms, as well as the emergence of new ones. However, restrictive measures alone could not be considered sufficient for a number of pathogens that are characterized by a high capacity for adaptation in healthcare settings, diverse mechanisms of resistance determinants acquisition and a high risk of global spread (the ESKAPE group:

Enterococcus faecium,

Staphylococcus aureus,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Acinetobacter baumannii,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter spp.) [

2]. The development of new approaches to prophylactic and therapeutic agents is particularly important for pathogens of this group.

Protein-based antimicrobials, such as phage- (endolysins) and bacterial-derived (bacteriocins) enzymes that degrade peptidoglycan, are among the innovative non-traditional compounds [

3]. Such molecules possess rapid action, low potential for resistance development, capable to disrupt bacterial biofilms, and mainly active against one of the bacterial categories (Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria) due to differences in peptidoglycan structure [

4,

5]. Although specificity of action may be advantageous from a safety point of view, the most serious infections often require complex action and therefore drugs with a narrow spectrum (e.g. individual endolysins) may not show sufficient efficacy [

3,

6]. A number of studies suggest combining lytic enzymes with antibiotics to reduce the doses of both components of the combination, increase efficacy and reduce toxicity [

7,

8,

9]. This approach has shown positive results

in vitro and in several models with Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacterial infections of various severity [

10,

11,

12]. Although the experimental results of such studies are impressive, the approach faces problems in practice. Thus, it was shown that the advanced endolysin CF-301 (Exebacase drug), used together with the standard-of-care antibiotic, failed to show sufficient efficacy in the Phase III clinical trials [

13]. It follows that more possible combinations and approaches should be explored to achieve success in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

There are several examples of combinations of bacteriolytic enzymes with antimicrobial peptides. For example, endolysin Ply2660 showed synergism with cathelicidin LL-37 against vancomycin-resistant

E. faecalis biofilms and in a murine model of peritoneal septicemia [

14]. Also, T7L and T4L endolysins were combined with colistin, polymyxin B and nisin and studied against

P. aeruginosa and

S. aureus and their biofilms, and significant synergy was shown for both species [

15]. However, antimicrobial peptides can be cytotoxic to eukaryotic cells and has limited effect against sessile bacteria, so further researches are needed.

Bacteriolytic enzymes can also be combined and reveal synergistic effect. Antipneumococcal endolysins Pal and Cpl-1 with different mechanisms of action potentiated each other effect

in vitro against

Streptococcus pneumoniae [

16]. Antistaphylococcal endolysin LysK demonstrated synergy with bacteriocin lysostaphin against methicillin-resistant

S. aureus in the checkerboard assay [

17]. However, most of the examples include enzymes with the same Gram-specificity. Our previous research shows that combination of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria-targeting enzymes can also be synergistic. Non-modified endolysin LysSi3 revealed synergy with lysostaphin against planktonic

S. aureus and dual-species (

S. aureus +

P. aeruginosa and

S. aureus +

K. pneumoniae) biofilms [

18].

Summarizing the known experience in the development of enzybiotics we are investigating the effects of combining the peptidoglycan hydrolases of different groups to create an effective substance for the treatment of polymicrobial biofilm-based wound infections. In this article, we explore the antibacterial properties of combinations of the engineered endolysin LysAm24-SMAP, which targets Gram-negative bacteria, with two Gram-positive bacteria-targeting enzymes – CHAP-containing endolysin LysCH2, which is similar in structure and properties to LysK, and the well-characterized bacteriocin lysostaphin (LST). The combinations have demonstrated in vitro and in vivo efficacy, and the research results will form the basis for the development of innovative bactericidal agents for topical therapy.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Antibacterial Properties of Bacteriolytic Enzymes

Critical or high priority pathogens include carbapenem-resistant

A. baumannii (CRAB), bacteria of the Enterobacterales genus resistant to third-generation cephalosporins and carbapenems as well as carbapenem-resistant

P. aeruginosa (CRPA) and methicillin-resistant

S. aureus (MRSA) rise serious challenges to healthcare [

2]. These species pose the greatest threat due to high morbidity and mortality, high virulence, limited treatment options and a strong tendency to spread resistance. According to published data, the six pathogens (

Escherichia coli,

S. aureus,

K. pneumoniae,

S. pneumoniae,

A. baumannii and

P. aeruginosa) directly caused 930,000 antimicrobial resistance-associated deaths and 4.78 million deaths were attributable to antimicrobial resistance [

19]. Also, there are few or no promising drugs in development for these species at the present time.

Most of these pathogens occur in severe skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) where they form polymicrobial consortia embedded in biofilms, causing significant difficulties in therapy, lead to a protracted course of the disease and hospitalization period. In this regard, timely and effective local antibacterial therapy, taking into account the probable spectrum of pathogens and their resistance, plays a key role in the success of SSTI treatment.

It is believed that peptidoglycan hydrolases are predominantly selective for either Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria [

20]. Combining enzymes with different Gram-targeting mechanisms to increase the efficacy of drugs against polymicrobial infections is therefore preferable. In addition, a deeper hydrolysis of peptidoglycan layer and a synergistic effect of the combination can be expected due to different substrate specificities. To develop an effective antibacterial agent, we selected proteins targeting the most common cephalosporin- and carbapenem-resistant species, such as

P. aeruginosa and Enterobacterales (mainly

E. coli,

Klebsiella spp.,

Enterobacter spp.) as well as methicillin-resistant

S. aureus and

S. epidermidis.

Our study includes previously described endolysin LysAm24 with lysozyme-like muramidase activity [

21]. The protein also contains the cell wall binding domain at the N-terminus, which is rather unusual as Gram-negative bacteria-targeting endolysins are typically globular with an enzymatic catalytic domain. Although LysAm24 was shown to have a broad spectrum of activity against Gram-negative bacteria and potential in the treatment of local infections [

22], it was demonstrated that LysAm24 was completely inhibited in isotonic solutions, presumably due to loss of ability to permeate the outer membrane. Genetic modification with an optimized fragment of the permeabilizing peptide SMAP-29 (1-17, K2,7,13) at the C-terminus results in the engineered endolysin LysAm24-SMAP, which is designed to potentiate enzyme activity in complex solutions. Two different peptidoglycan hydrolases – endolysin LysCH2 and bacteriocin LST, were investigated to include in the composition as a component targeting Gram-positive bacteria. LysCH2 is a predicted N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase from Staphylococcus phage, a truncated homologue of the known LysK, CHAP-domain-containing endolysin [

23,

24], while LST is a glycyl-glycine endopeptidase from

Staphylococcus simulans that hydrolyzes crosslinking pentaglycine bridges [

25].

LysAm24-SMAP was shown to have potent antibacterial activity against several Gram-negative species, including those with multiple drug resistance (

Figure 1c). The average activity against different species was:

A. baumannii – 100.0%,

P. aeruginosa – 99.3%,

E. coli – 55.8%,

K. pneumoniae – 41.0%. Spectrum of LysCH2 and LST includes Gram-positive bacteria and reveals 100% average activity of LST against three species; LysCH2 has 100.0%, 99.5% and 99.6% average activity against

S. aureus,

S. epidermidis,

S. haemolyticus, respectively (

Figure 1c).

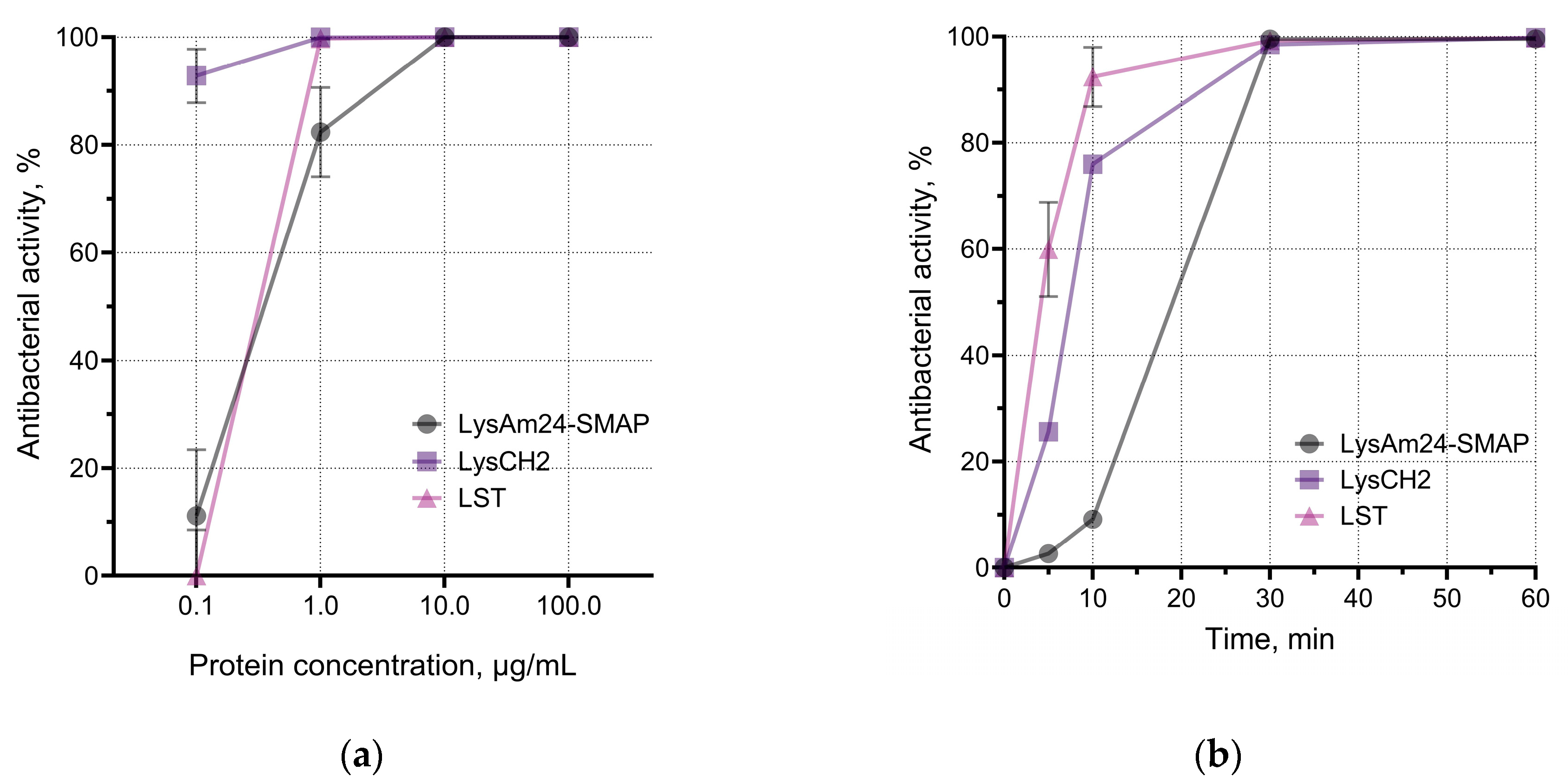

We assessed the effective antibacterial doses of enzymes and their rate of action against host bacterial species (

Figure 1a, b). LysAm24-SMAP killed more than 80% (or up to 1.5×10

5 CFU/mL) of planktonic

A. baumannii at concentrations higher than 1 μg/mL. We also observed dose-dependency of LysCH2 and LST against

S. aureus. Comparison of enzymes showed that average doses required to reveal the effects against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria vary by about 10 times: concentrations needed to kill 99.9% of bacterial cells (bactericidal concentration) by LysAm24-SMAP, LysCH2, and LST were 11.56 μg/mL, 1.46 μg/mL, and 0.98 μg/mL correspondingly. It is a well-known phenomenon that much higher concentrations are required to kill Gram-negative bacteria than Gram-positive bacteria [

26]. We suggest that these differences result from the enzyme interacting with and inhibited by the outer membrane structures of cells [

27,

28], although LysAm24-SMAP activity was measured in PBS buffer to reduce non-specific electrostatic interactions.

At the same time, the time-kill assay showed that LST acted faster, and the time required for this enzyme to kill 90.0% of the bacteria was 8.95 min, compared to 13.80 minutes for LysCH2 and 18.60 minutes for LysAm24-SMAP. However, all three enzymes reach plateau at approximately 30 min of incubation (

Figure 1b).

The pH of the medium had a moderate effect on the activity of the proteins, which was more pronounced in the case of LysAm24-SMAP. It was shown that LysAm24-SMAP has the maximum activity at mild acidic (pH 5.0) and mild alkalic (pH 8.0) conditions (

Figure 1d), LysCH2 is significantly inhibited at pH 8.0, while LST shows 100% activity over the pH range studied (

Figure 1d). The pH dependence shows that mild acidic values are optimal, and both components of the combination could be effective and show maximum efficiency.

The results show that selected enzymes are suitable in terms of their spectrum of bacterial targets, are comparable in the rate of antibacterial action, and require close conditions for maximum activity. This makes it possible to further investigate their properties in combination.

2.2. Enzymes Combinations Effects on Planktonic Bacteria and Biofilms

To assess the effects of combination on lysins activity a standard minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay, minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) assay and a checkerboard test were conducted for several strains (

Table 1).

For LysAm24-SMAP MIC was determined for an only

A. baumannii and it was 64 µg/mL. For other Gram-negative species we observed growth inhibition expressed in approximately two-fold optical density decrease at 1024 µg/mL concentration, however, MICs were not estimated (

Figure S1). The same was found for LysCH2, where no MICs were reached despite high concentrations, but a 2-3-fold decrease in the optical density of Gram-positive bacteria was observed. LST at the studied concentrations has pronounced activity against one of two

S. aureus strains with the MIC 0.5 µg/mL (

Figure S2).

When the content of the wells was plated on agar medium the MBC of LysAm24-SMAP was defined for

E. coli ATCC 25922 – 1024 µg/mL and for

A. baumannii ATCC 19606 – 64 µg/mL. Similarly, MBC of LysCH2 for

S. aureus ATCC 25923 was 128 µg/mL without the MIC estimation. It can be suggested that large aggregates of lysed bacterial cells contribute to the optical density of the suspensions and lead to false conclusions about the effectiveness of the enzymes and underestimation of antibacterial effect. Therefore, for combination studies we chose to estimate the bactericidal concentrations [

29] rather than the MICs, which don’t reflect the real activity of endolysins. Interestingly, LysCH2 requires much higher (more than 100-fold) effective concentrations in the MIC assay compared to LST, despite the fact that they do not have drastically different individual

in vitro properties.

Antimicrobial synergy testing was used to determine the impact of two enzymes combinations (LysAm24-SMAP + LysCH2; LysAm24-SMAP + LST) for 6 bacterial strains. Based on the checkerboard assay we have calculated fractional bactericidal concentration index (ΣFBC) (

Table 1,

Figure S1,

Figure S2). Combination of LysAm24-SMAP and LysCH2 appeared to have mostly additive effect for both Gram-positive (

S. aureus) and Gram-negative bacteria (

K. pneumoniae,

E. coli), while it was indifferent for

A. baumannii. For

S. aureus strains 64 µg/mL of LysAm24-SMAP reduces the MBC of LysCH2 by 2-4 times. For

E. coli 32 µg/mL of LysCH2 reduces the MBC of LysAm24-SMAP by 2 times. It should also be noted that in all experiments the maximum concentrations in combination (1024 μg/mL LysAm24-SMAP + 128 μg/mL LysCH2) gave the best results for all strains, as no bacterial growth was observed, except for

P. aeruginosa.

The LysAm24-SMAP and LST combination has a pronounced synergistic effect on

S. aureus strains, where the lowest investigated concentration of LysAm24-SMAP (64 µg/mL) reduced the MBC of LST by 8 times. At increased concentrations of LysAm24-SMAP (1024 µg/mL) bactericidal effect was observed even at 0.06 µg/mL of LST (16-fold MBC reduction). On the other hand, combination of these compounds had no increase in inhibitory activity on Gram-negative bacterial species (

A. baumannii,

E. coli). No antagonistic interactions were observed with any of the combinations. Our data are consistent with previous results on LST and LysSi3 combinations, where synergism was demonstrated for

S. aureus [

18]. This phenomenon could be explained by simultaneous hydrolysis of different peptidoglycan bonds of

S. aureus by different types of peptidoglycan hydrolases and deeper degradation of PG, but a significant difference between combinations with LysCH2 and LST remains unclear.

Effective disruption of biofilms is one of the key advantages of enzybiotics as antibacterial agents. Numerous studies approve enzymes efficacy against different bacterial consortia, acting on both cells and matrix components [

20,

30,

31]. Based on the data obtained in the checkerboard assay 1 mg/mL LysAm24-SMAP + 0.1 mg/mL LysCH2 (10:1 ratio), and 1 mg/mL LysAm24-SMAP + 0.01 mg/mL LST (100:1 ratio) were selected as fixed enzymes combinations to study the antibacterial effect on the model mono-species (

K. pneumoniae,

S. aureus) and dual-species (

K. pneumoniae +

S. aureus) biofilms (BF).

As shown by the plate test results, LysAm24-SMAP plays a key role in the destruction of BFs in

K. pneumoniae and

K. pneumoniae +

S. aureus, with a predictably less pronounced effect on

S. aureus BFs. (

Figure S3). Surprisingly, LysCH2 or LST alone had no effect on

S. aureus BFs, showing slightly increased crystal violet staining after the treatment compared to the control. Although individual enzymes were capable to degrade biofilms, the combinations of LysAm24-SMAP and LysCH2 did not show any additive effects on mono- and dual-species BFs. On the opposite, synergic interaction was detected in

S. aureus and mixed biofilms for LysAm24-SMAP and LST cocktail.

An analysis similar to the checkerboard assay with LysAm24-SMAP and LST was performed on BF-associated

S. aureus ATCC 29213 using crystal violet staining of adherent structures (biofilms and large aggregates) (

Figure S4). Even at the lowest enzyme concentrations (64 µg/mL LysAm24-SMAP + 0.06 µg/mL LST) there was no evidence of biofilm formation, confirming the synergistic effect on both planktonic and BF-associated

S. aureus.

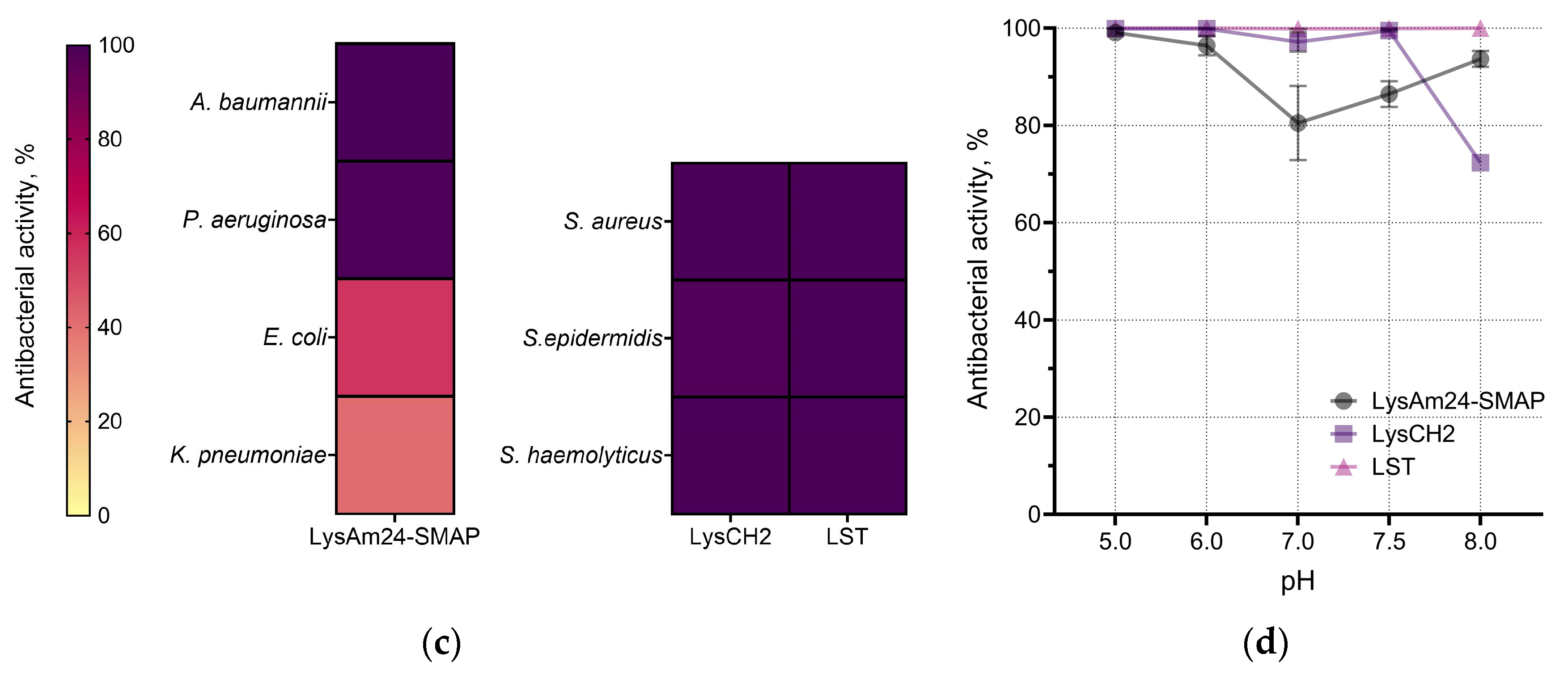

A fluorescent differential staining was done for mixed

P. aeruginosa and

S. aureus BFs treated with the cocktail of LysAm24-SMAP and LST (

Figure 2). Despite the lack of enzyme synergism against

P. aeruginosa in the checkerboard assay, the effect of the combination on the on the glass slides preformed biofilms was also detected. Treatment with the enzymes solution showed the absence of intensive cell bodies staining in a complex biofilm mileu or extracellular polymeric matrix in the area of enzymes’ application.

Previously LST demonstrated increased inhibition and disruption of

S. aureus biofilms when enzyme was mixed with DNase I [

31]. The authors suggested that this was probably due to the removal of extracellular DNA by DNase, leading to the disruption of mature biofilms, thereby facilitating the penetration of LST. In addition to its bactericidal activity, LysAm24 has been shown to have a strong DNA-binding capacity [

27], which may also contribute to the complex antibiofilm activity of the combination.

The combination of LysAm24-SMAP and LST can therefore be considered highly effective for developing antibacterial therapeutics for the treatment of biofilm-associated polymicrobial infections.

2.3. In Vivo Evaluation of Combination Against Biofilm Wound Infection

Treatment of infections associated with biofilm formation poses particular challenges to antibiotic therapy. This is particularly important for wound infections, which are typically polymicrobial and biofilm-related. At the same time, there are not many adequate models for assessing the properties of new antibacterial drugs in vivo for such nosology. Here we evaluated the efficacy of the selected combination in a murine model of wound infection caused by a polymicrobial consortium including P. aeruginosa and S. aureus in a pre-grown biofilm. We believe that such a model better reflects the processes that occur during the development of SSTI, which may contribute to healing dynamics and antibiotic tolerance.

To obtain antibacterial substance, enzymes combination (1 mg/mL LysAm24-SMAP + 0.01 mg/mL LST) was formulated in a gel base containing 0.5% of alginic acid sodium salt and 1.0% of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose.

Two isolates were used to model local wound infection: S. aureus 73-14 (MRSA) and P. aeruginosa 38-16 (resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, gentamicin, meropenem and tetracycline, and requires excessive doses of polymyxin B). The dual-species biofilms, preformed in a tube, were applied to a damaged skin and one day later the treatment with combination gel or vehicle gel began.

Both

P. aeruginosa and

S. aureus were present on the 1

st day before treatment as was shown by wound homogenates cultivating (

Figure S5), the mean bacterial load was 7.28 × 10

6, 5.09 × 10

6 и 2.84 ×10

7 CFU/mL for untreated, vehicle and combination gel groups, respectively, with no statistical difference between groups.

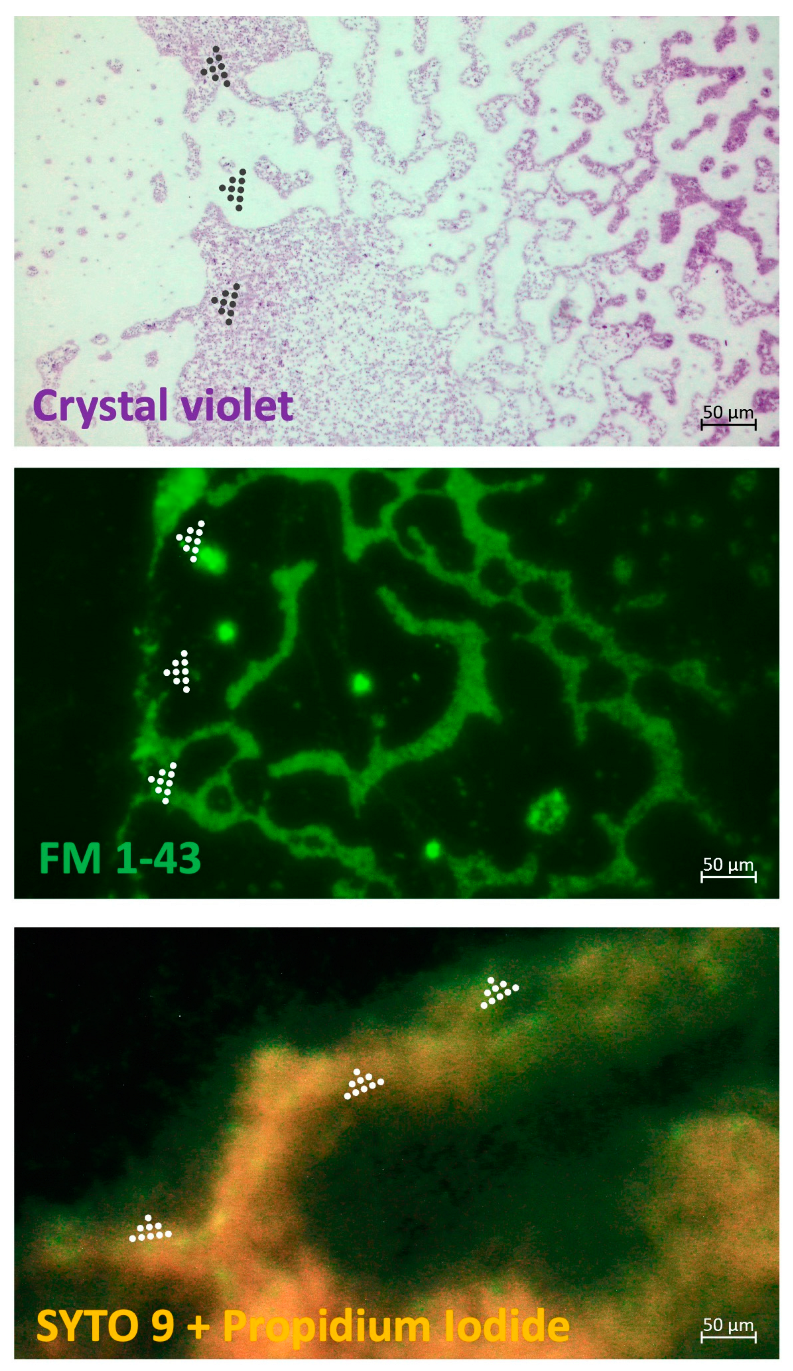

We accessed the wound closure and bacterial decolonization during the course of treatment (

Figure 3). Application of the combination gel with enzymes resulted in the absence of the significant bacterial growth in the wounds and a reduction in contamination of blood samples (

Figure S6), indicating the efficacy of the composition. Thus, the bacterial load in the wound samples from the vehicle group increased by 1723% (almost 20-fold from the initial burden) by day 7, by an average of 5.2-fold in the untreated animals and by 2.3-fold in animals treated with the combination gel (

Figure 3a,

Figure S5). At the same time, an increase in the CFU number in the blood samples was detected only in the untreated animals group, indicating a generalization of the infection in the mice in the absence of wound treatment (

Figure S6). Therefore, topical treatment with both the vehicle gel and the enzymes-containing gel prevented the spread of bacteria from wound defects to the bloodstream, apparently due to the formation of a film on the wound surface as the gel dries. However, the vehicle gel did not prevent and even promote the total bacterial growth within the defect and adjacent tissues, as extensive suppuration and abscess formation were found during autopsy.

The species composition also differed significantly between groups (

Figure 3b). In the untreated animals,

P. aeruginosa was present in the wound defects up to the end of the observation period and reached 30% or more of the total CFU count. On the opposite, only single

P. aeruginosa CFUs were found in the vehicle and combination gel-treated groups by day 7. It can be noticed that despite both vehicle and combination gels effectively eliminated Gram-negative species, vehicle gel significantly increased the total bacterial load due to

S. aureus colonization.

The presence of both pathogens in the samples was also confirmed by PCR results for the

gmk and

rpsL genes, which are often considered housekeeping genes (HKs) when determining the expression levels of genes associated with biofilm formation in

S. aureus and

P. aeruginosa, respectively (

Figure S7) [

18,

32,

33]. Target genes expression was detected in samples of wound homogenates obtained from mice on day 1 and day 7 after infection. On the 7

th day, threshold cycles (C

ts) of

P. aeruginosa rpsL fragments increased dramatically, and were detected in only a few samples in the vehicle and combination gel groups, consistent with the cultivation results. It is worth noting that there was no amplification of the target fragments in any of the control uninfected skin samples taken from the same animals.

In general, there was a correlation between the dynamics of wound healing and bacterial load (

Figure 3c). The open wound area was 21.7 – 22.2 mm

2 in all groups before the start of treatment (24 h postinfection). There was virtually no statistical change in wound surface area during the observation period in the untreated group (23.1 mm

2 on day 7), and a decrease in surface area on day 7 in the vehicle and combination-treated groups, which were 17.1 and 12.5 mm², respectively, with a statistical difference between the negative control and combination gel groups. In addition, a more pronounced hyperemia of the wound area was observed in the vehicle group and in the untreated group.

To date, there are no reported studies of combinations of enzymes with different Gram-specificity for the treatment of polymicrobial infections

in vivo. However, a few promising strategies to combine peptidoglycan hydrolases with antibiotics or antimicrobial peptides are described.

In vitro studies showed a pronounced synergy of endolysin Ply2660 with LL-37 antimicrobial peptide in the degradation of

E. faecalis biofilms [

14]. Combinations of T7L and T4L endolysins with colistin, polymyxin B and nisin also showed significant synergy against

P. aeruginosa and

S. aureus and their biofilms [

15].

In vivo murine wound model was performed for ElyA1 endolysin, which significantly reduced

A. baumannii bacterial load when combined with colistin [

10]. Therefore, new combination options are highly required to eliminate polymicrobial consortia, especially

in vivo biofilms-related infections.

Thus, we have shown that serious local infections, including those associated with the formation of complex bacterial consortia and biofilms, can be effectively treated and prevented with the enzybiotic containing the combination of lytic enzymes targeting bacteria of different Gram-specificity. Animal wound model showed that the combination significantly prevents the bacterial burden growth, stops the estimation of chronic process and systematization of the infection. However, in order to achieve a more pronounced antibacterial effect, the concentration of enzymes in the combination as well as the excipients composition should be optimized and the most effective regimes of the treatment should be defined.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Recombinant Proteins Expression and Purification

The LysAm24-SMAP coding sequence, including the LysAm24 muramidase sequence (NCBI AN: APD20282.1) and a fragment of the antimicrobial peptide SMAP-29 (1–17, K2,7,13, RKLRRLKRKIAHKVKKY) on C-terminus of enzyme, was artificially synthesized in the pAL-TA vector (Evrogen, Russia) and integrated into the pET-42b expression vector (+). The LysCH2 coding sequence (NCBI AN: QAY02446.1) and LST coding sequence (NCBI AN: AJM90220.1) were also artificially synthesized in the pAL-TA (Evrogen, Russia) vector and integrated into the pET-42b expression vector (+). The correctness of the assembly of vector constructs was verified by Sanger sequencing.

The enzymes constructs were introduced into the E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS strain using the heat-shock transformation. The obtained producers were cultured at 37°C, 250 rpm in in 2×YT medium (16 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl) with the selective antibiotics (30 µg/mL chloramphenicol, 50 µg/mL kanamycin) addition to optical density OD600 = 0.6-0.8. Then the proteins expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (AppliСhem, Germany) at 37°C for 4 h. The cells biomasses were harvested by centrifugation (6000×g, 10 min, 4°C) and disrupted by sonication.

The cells debris was removed by centrifugation (10000×g, 30 min, 4°C), and supernatants were purified on NGC Discovery™ 10 FPLC system (Bio-Rad, United States). LysAm24-SMAP-containing supernatant purification was carried out on a XK 16/20 column (GE Healthcare, United States) using a cation exchange SP-sepharose FF resin (GE Healthcare) and afterwards on a XK 16/600 column (GE Healthcare) using a gel exclusion resin Superdex 75pg (GE Healthcare). The protein was eluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS tablets: 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.3-7.5, VWR, United States).

LST-containing supernatant was purified using a cation exchange SP-Focurose HPR resin (VDO Biotech, China), eluted by 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl buffer and dialysed against 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 buffer solution.

LysCH2 was expressed in inclusion bodies which were washed in PBS and dissolved in 8М urea, 0.5 M NaCl, 1% glycerol, 10 mM imidazole, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 buffer overnight. After the centrifugation (10000×g, 60 min, 4°C), the supernatant was purified on an affinity HiTrap IMAC FF resin (GE Healthcare) and eluted by a linear imidazole gradient (10 mM to 250 mM). The protein fractions were pooled and dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 buffer.

The proteins concentrations were determined by measurement of the optical density at 280 nm wavelength (Implen NanoPhotometer, IMPLEN, Germany) and calculated using a predicted extinction coefficients (LysAm24-SMAP, 0.852 (mg/mL)-1cm-1, 27.0 kDa; LST, 2.398 (mg/mL)-1cm-1, 27.5 kDa, LysCH2, 2.155 (mg/mL)-1cm-1, 29.8 kDa). The protein purity was determined by 16% SDS-PAGE.

3.2. Bacterial Strains

The ATCC collection strains and clinical isolates (N.F. Gamaleya National Center for Epidemiology and Microbiology, Russia) of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including several multiple drug resistant representatives, were stored at -80°C and cultured in liquid medium at 37°C, 250 rpm or on the agar medium overnight before assay.

3.3. Enzymes Activity Assay

To evaluate antibacterial activity of the enzymes, overnight bacterial cultures were diluted in fresh Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB, HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., India) and grown to the exponential growth phase (optical density OD600 = 0.5-0.7) at 37°C, 250 rpm. Then, the culture was centrifuged and resuspended in PBS pH 7.4 to the turbidity visually equal to the McFarland turbidity standard of 0.5 (~1.5 × 108 CFU/mL).

The bacterial suspension was diluted 100 times in PBS pH 7.4 (for LysAm24-SMAP activity) or in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 (for LysCH2 and LST activity). Enzymes were also diluted to the required concentrations in PBS pH 7.4 (LysAm24-SMAP) or 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 (LysCH2 and LST). Subsequently, 100 μL of enzyme solutions and 100 μL of the prepared suspensions were added to the 96-well plates and incubated for 30 min (LysAm24-SMAP) or 60 min (LysCH2 and LST), unless specified, at 200 rpm, 37°C. Buffer solutions (PBS pH 7.4 or 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5) mixed with bacteria were used as negative controls.

After incubation, the mixtures were diluted tenfold in PBS, 100 μL each was plated on Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) and incubated at 37°C for 16-18 h. Colony forming units (CFUs) were counted and the antibacterial activity was estimated according to the formula:

where CFU

exp is the CFU number in the experimental culture plates, and CFU

cont is the CFU number in the control culture plates. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

The dose-dependency study was performed at 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 μg/mL proteins concentrations. The kinetic study was performed at 5, 10, 30, and 60 minutes of incubation and 1 μg/mL proteins concentration. The pH-dependent activity examined at proteins concentration of 1 μg/mL in 20 mM Tris-HCl or PBS buffer solutions with pH values of 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 7.5, 8.0. LysAm24-SMAP activity was assessed against A. baumannii 50-16 model strain, LysCH2 and LST – against S. aureus ATCC 29213.

Spectrum of action was evaluated at 100 μg/mL LysAm24-SMAP concentration and 10 μg/mL LysCH2 and LST concentration. Bacterial strains included A. baumannii (n=6), P. aeruginosa (n=9), E. coli (n=6), K. pneumoniae (n=5), S. aureus (n=15), S. epidermidis (n=5), S. haemolyticus (n=3). Antibacterial activity was regarded as meaningful when it exceeded 30%.

3.4. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations Estimation and Checkerboard Assay

To evaluate the MICs of proteins, bacterial collection strains (

S. aureus ATCC 29213,

S. aureus ATCC 25923,

A. baumannii ATCC 19606,

P. aeruginosa АТСС 9027,

K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031,

E. coli ATCC 25922) were used. The test was performed according to the broth microdilution method [

34]. Briefly, the strains were grown overnight on MHA, then 2–5 individual colonies were resuspended in PBS to the 0.5 McFarland units turbidity following 100-fold dilution with MHB. Afterwards, bacterial cultures (50 μL) were mixed with 2-fold serial dilutions of the enzymes (50 μL) and incubated at 37°C for 16–20 h. Final protein concentrations ranged from 64 to 1024 µg/mL for LysAm24-SMAP, from 8 to 128 µg/mL for LysCH2, and from 0.06 to 1 µg/mL for LST. Bacterial culture in MHB (100 μL) was used as a growth control, and MHB alone was used as a sterility control. The MICs was estimated by OD

600 measurement and were confirmed as the lowest antimicrobial concentration that prevented visible bacterial growth.

Checkerboard assay was performed by microdilution method as previously described for bacteriolytic enzymes combinations [

18]. Two-fold serial dilutions of the enzymes (concentrations from 64 to 1024 µg/mL for LysAm24-SMAP, from 8 to 128 µg/mL for LysCH2, and from 0.06 to 1 µg/mL for LST) were prepared in PBS buffer solution. Bacterial cultures were prepared as described above for MIC estimation in MHB, mixed with the enzymes and incubated at 37°C for 16–20 h. MICs were estimated by OD

600 measurement and visually confirmed.

In addition, mixtures were plated on MHA and incubated at 37°C for 16–20 h. MBCs were established as the bactericidal concentration with complete elimination of bacteria. The fractional bactericidal concentration (FBC) for both antimicrobials was calculated by dividing the MBC of two enzyme in combination with the MBC of each enzyme alone. For each combination, the results were evaluated by the calculation of fractional bactericidal concentration index (ΣFBC) representing the sum of FBC of LysAm24-SMAP and FBC of LysCH2 or LST considering to be as follows: 0 <

x ≤ 0.5—synergism; 0.5 <

х ≤ 1— additive effect; 1 <

х ≤ 2—indifference;

x > 2—antagonism [

29].

For BF formation assessment the wells after incubation were gently washed twice with 200 µL of PBS, air-dried, stained with 100 µL of 0.1% crystal violet (Applichem, Germany) for 20 min, followed by triple rinsing with water. The remaining stain was re-solubilized in 200 µL of 33% acetic acid, and the OD590 of the solutions was measured (SPECTROstar NANO Absorbance Reader, BMG LABTECH, Germany).

3.5. Biofilms Formation and Enzymes Antibiofilm Activity

Bacterial cultures of

K. pneumoniae 104-14 and

S. aureus 73-14 isolates were grown overnight in a TSB (BD Tryptic Soy Broth) at 37°C for 16–20 h, harvested by centrifugation (6000×g, 5 min), resuspended in PBS to a turbidity corresponding to 1.0 McFarland units (~3 × 10

8 CFU/mL) and 100-fold diluted in the TSB [

18].

For mono-species biofilms, bacterial cultures (100 µL) were added to the wells of 96-well sterile polystyrene cell culture plates (Eppendorf, Germany). For dual-species biofilms, Klebsiella and Staphylococcus cultures were mixed in 1:1 (v/v) ratio and added to the wells in 100 µL volume. Plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C, 250 rpm to allow strong biofilms formation.

Afterwards, wells were gently washed twice with 200 µL of PBS and air-dried for 15 min. Then 100 µL of individual enzymes solutions (1 mg/mL LysAm24-SMAP, 0.1 mg/mL LysCH2, 0.01 mg/mL LST) or their combinations (1 mg/mL LysAm24-SMAP + 0.1 mg/mL LysCH2; 1 mg/mL LysAm24-SMAP + 0.01 mg/mL LST) were added to the wells and incubated at 37°C, 250 rpm for 4 h. The 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.5 was used as a negative control.

After incubation, wells were carefully washed twice 200 µL of PBS, air-dried, stained with 100 µL of 0.1% crystal violet (Applichem, Germany) for 20 min, followed by triple rinsing with water. The remaining stain was re-solubilized in 200 µL of 33% acetic acid, and the OD

590 of the solutions was measured (SPECTROstar NANO Absorbance Reader, BMG LABTECH, Germany). All experiments were performed in five replicates. The experimental values were normalized by dividing by the mean OD

590 of corresponding negative control. The interpretation of the biofilm formation was performed according to [

35].

3.6. Microscopy

Bacterial cultures of P. aeruginosa 38-16 and S. aureus 73-14 isolates were grown in a TSB (BD Tryptic Soy Broth) at 37°C for 16–20 h, harvested by centrifugation (6000×g, 5 min), resuspended in PBS to a turbidity corresponding to 1.0 McFarland units (~3 × 108 CFU/mL) and 100-fold diluted in the TSB. Sterile glass coverslips (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA) were plunged in Petri dishes containing the bacterial cultures mixture 1:1 (v/v) in TSB with approximately 106 CFU/mL of each strain. The dishes were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h without shaking. Slides were carefully washed with sterile water, and 10 µL of the enzymes combination (1 mg/mL LysAm24-SMAP + 0.01 mg/mL LST) or control buffer were dropped onto the slides, and they were incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Afterward, the slides were again carefully washed with sterile water two times.

Air-dried slides were stained with a 0.1% crystal violet solution for 15 min at RT, rinsed with water, and air-dried for bright-field microscopy. Other slides were stained with FilmTracer™ FM 1-43 green biofilm cell stain (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) and the FilmTracer™ LIVE/DEAD® Biofilm Viability Kit (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA), according to the manufacturers’ instructions for dark-field fluorescent microscopy. All slides were imaged with the Axiostar Plus Transmitted Light Microscope (Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany) at ×400 magnification. Microphotographs were proceeded with the ZEN 3.0 (blue edition) software (Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany).

3.7. In Vivo Assessment of Enzymes Combination Using Polymicrobial Biofilm Wound Infection Model

A combination of LysAm24-SMAP and LST enzymes was formulated in a gel base containing 0.5% of alginic acid sodium salt (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany) and 1% of carboxymethyl cellulose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 20 мМ Tris pH = 6.0, to the final concentration of enzymes 1 and 0.01 mg/mL correspondingly. Vehicle gel had the same composition without enzymes.

Before the manipulations with the animals, the preformed biofilms were grown. For this,

S. aureus 73-14 and

P. aeruginosa 38-16 bacteria were incubated in TSB overnight. The cells were pelleted (6,000×g, 10 min, RT), resuspended in PBS to a turbidity corresponding to 1.0 McFarland units. Both strains were added in a 100-fold dilution each to the fresh TSB medium with the addition of 1% glucose. Five mL of the prepared medium containing bacteria were added to a sterile tube together with a tip, which acts as a surface for biofilm formation [

36]. Then the tube was incubated at 37

oС for 48 h without aeration. The formed dense viscous biofilm from the surface of the tube was used as an infecting agent.

To model the mixed biofilm wound infection 27 female BALB/c mice (20–22 g) were used. Before the experiments animals were weighted and their backs were shaved with an electric razor. Mice were randomly allocated in three experimental groups: treatment with lysins-containing gel (n = 9), treatment with placebo gel (n = 9) or untreated animals (n = 9). Animals were anaesthetized with intramuscular injection of Zoletil-xylazine mixture (45 mg/kg and 7.5 mg/kg) and one full-thickness skin wound (d = 8 mm) was made with biopsy gun Dermo-Punch (Sterylab, Italy). After 5 minutes, animals were infected with the preformed biofilm applied to the surface of the wound in a volume of 20 μl. Twenty-four hours after the infection three animals from each group were euthanized, heart blood samples and infected dermal grafts were taken. Control skin samples were also taken from the same animals at a distance of 1 cm from the infected area to minimize contamination. Grafts were homogenized in 1 ml of PBS using TissueLyser II (Thermo FS, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples of grafts and blood were serially diluted, plated on MHA (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., India) and bacterial CFU were counted after an overnight incubation at 37 °C. Homogenates were also taken for PCR analysis. PCR analysis of wounds bacterial contamination was conducted as described in [

18] for

S. aureus (gmk gene)

and P. aeruginosa (

rpsL gene).

Wounds of the remaining animals were epicutaneously treated with 100 μl of combination gel, vehicle or were left untreated. The animals were treated twice a day with 6 h interval for 5 days. Wound-closure progression (planimetry) was analyzed by measuring the bounds of the wounds in two dimensions (width and length) and the area was calculated using the of the oval area equation. On the 3rd and 7th days the grafts and blood samples were collected for 3 animals in each group as described above.

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and approved by the Ethic Committee of N.F. Gamaleya National Research Centre for Epidemiology and Microbiology (Protocol number 40, 03.04.2023).