Submitted:

07 November 2024

Posted:

08 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (i)

- glycosidases, cleaving the bonds between N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid, including two subgroups: N-acetylmuramidases and N-acetylglucosaminidases

- (ii)

- transglucosylases, cleaving bonds between N-acetylmuramic acid and N-acetylglucosamine (like N-acetylmuramidases), but in a different mechanism; they do not require water, thus are not considered hydrolyses

- (iii)

- amidases, cleaving the amide bond between N-acetylmuramic acid and L-alanine, the first amino acid in the cross-linking peptide

- (iv)

2. Results

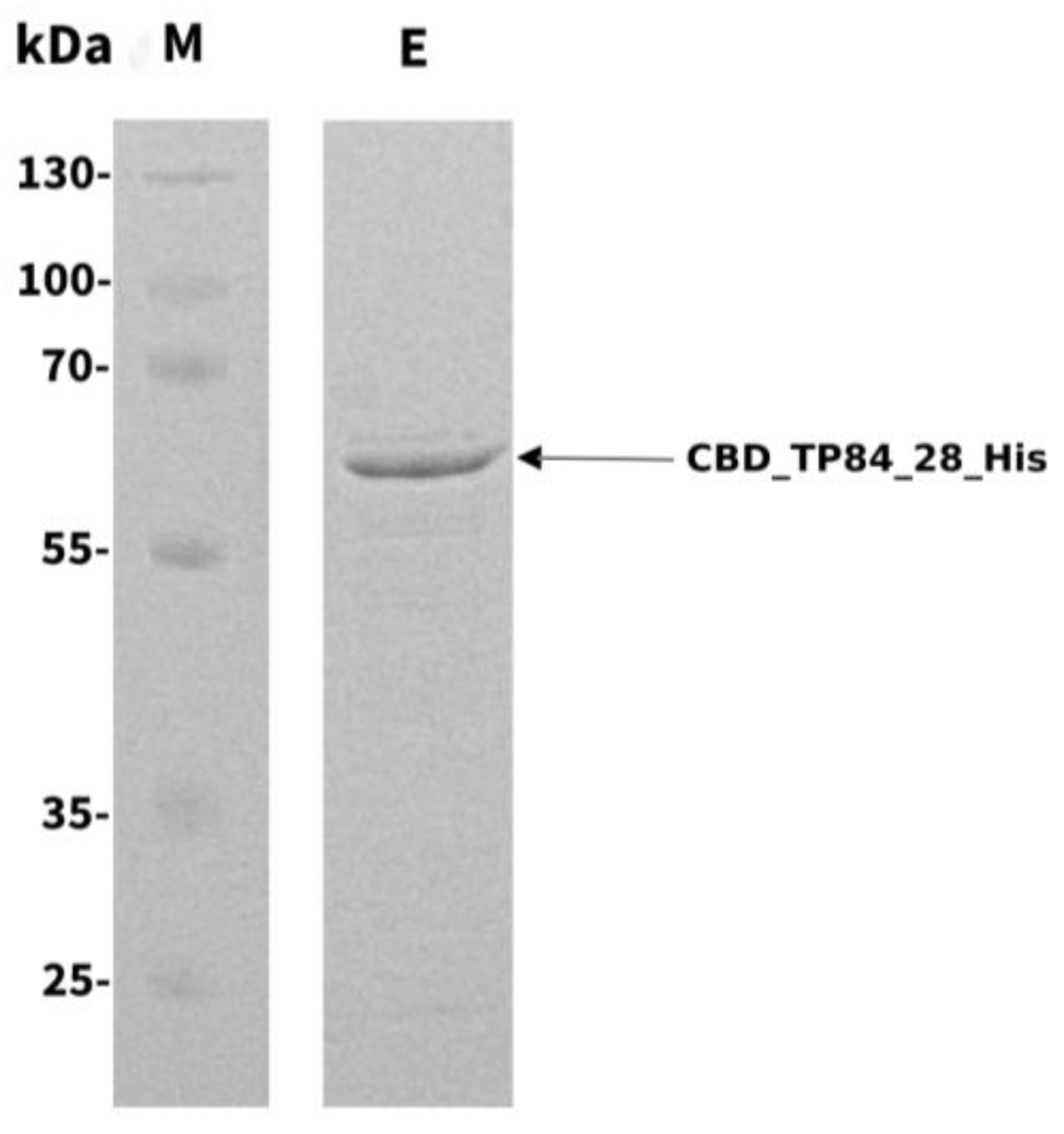

2.1. Cloning, Overproduction, and Purification of Recombinant Fusion Endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His

2.2. Properties of the Recombinant Fusion Endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His

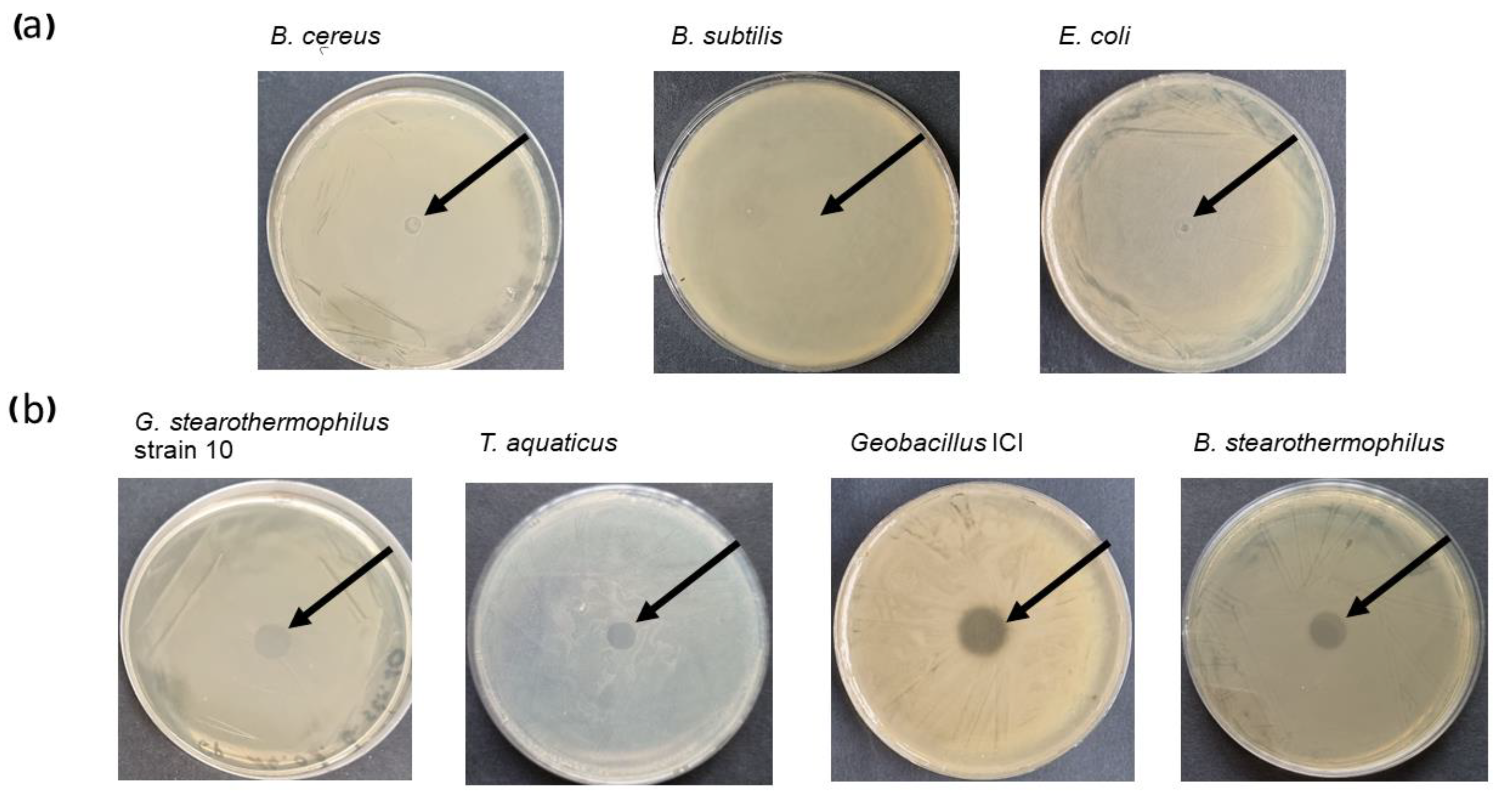

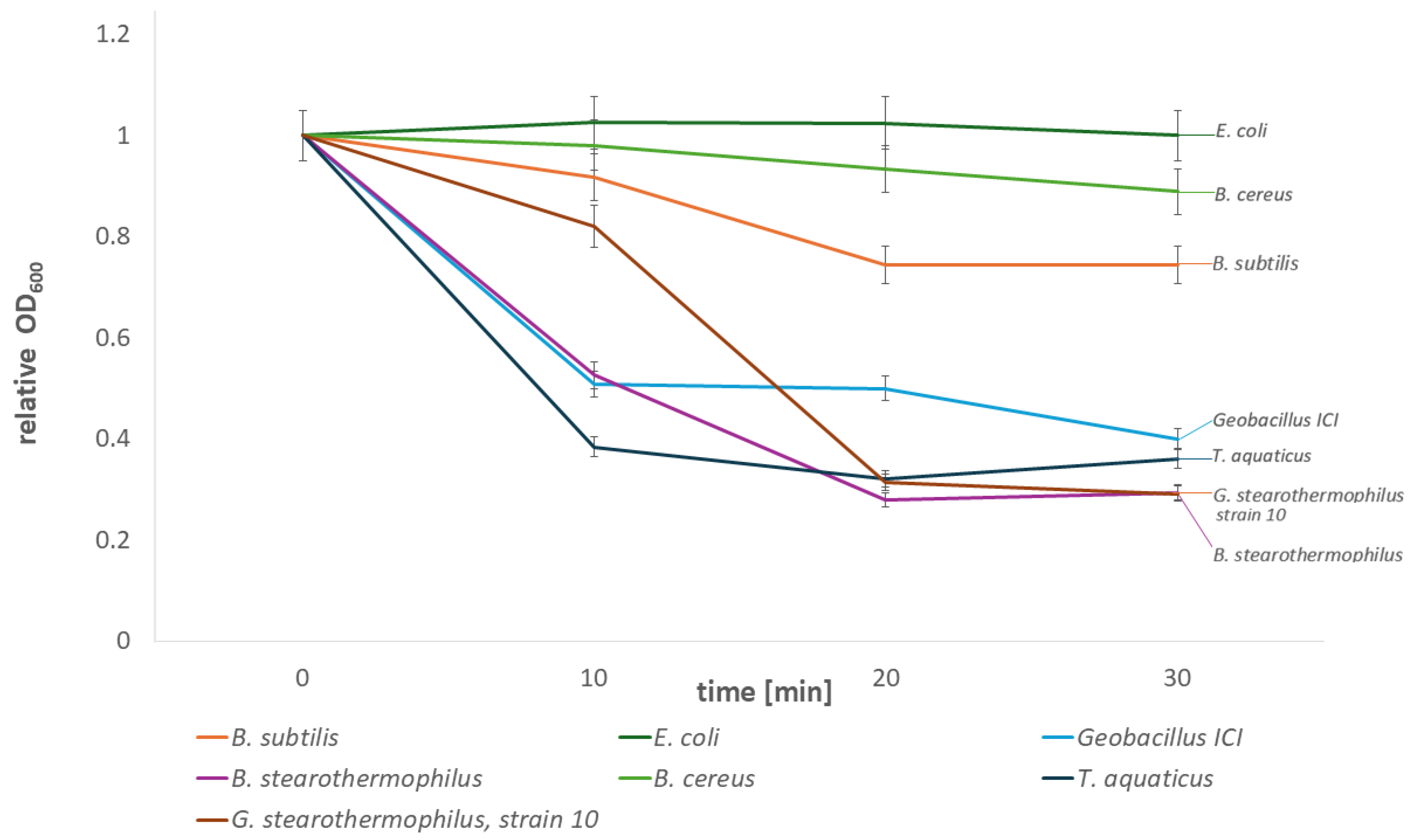

2.2.1. Lytic Activity of the Recombinant Fusion Endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His Against Test Bacteria

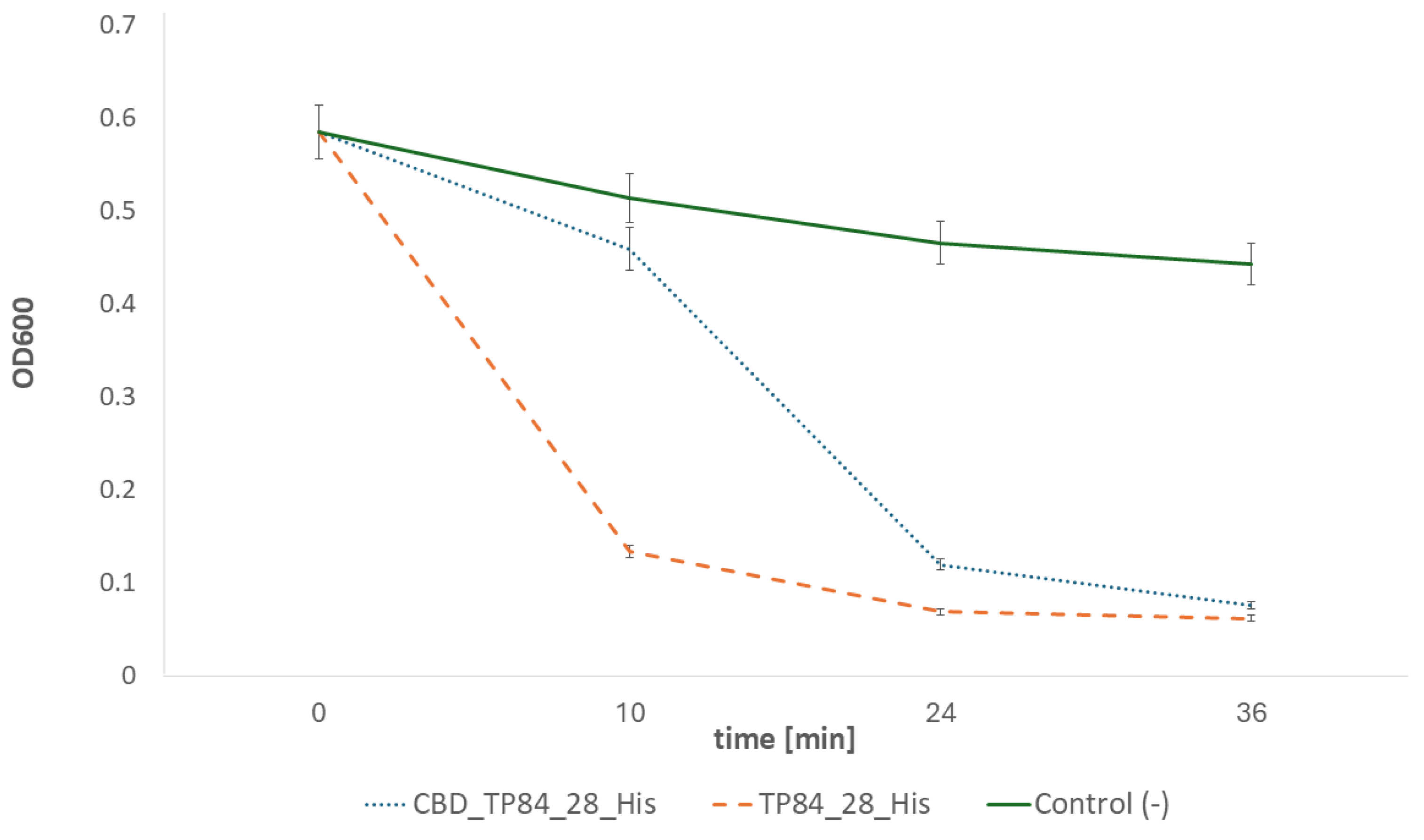

2.2.2. Activity of the Recombinant Fusion Endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His in Comparison to Recombinant Endolysin TP84_28_His

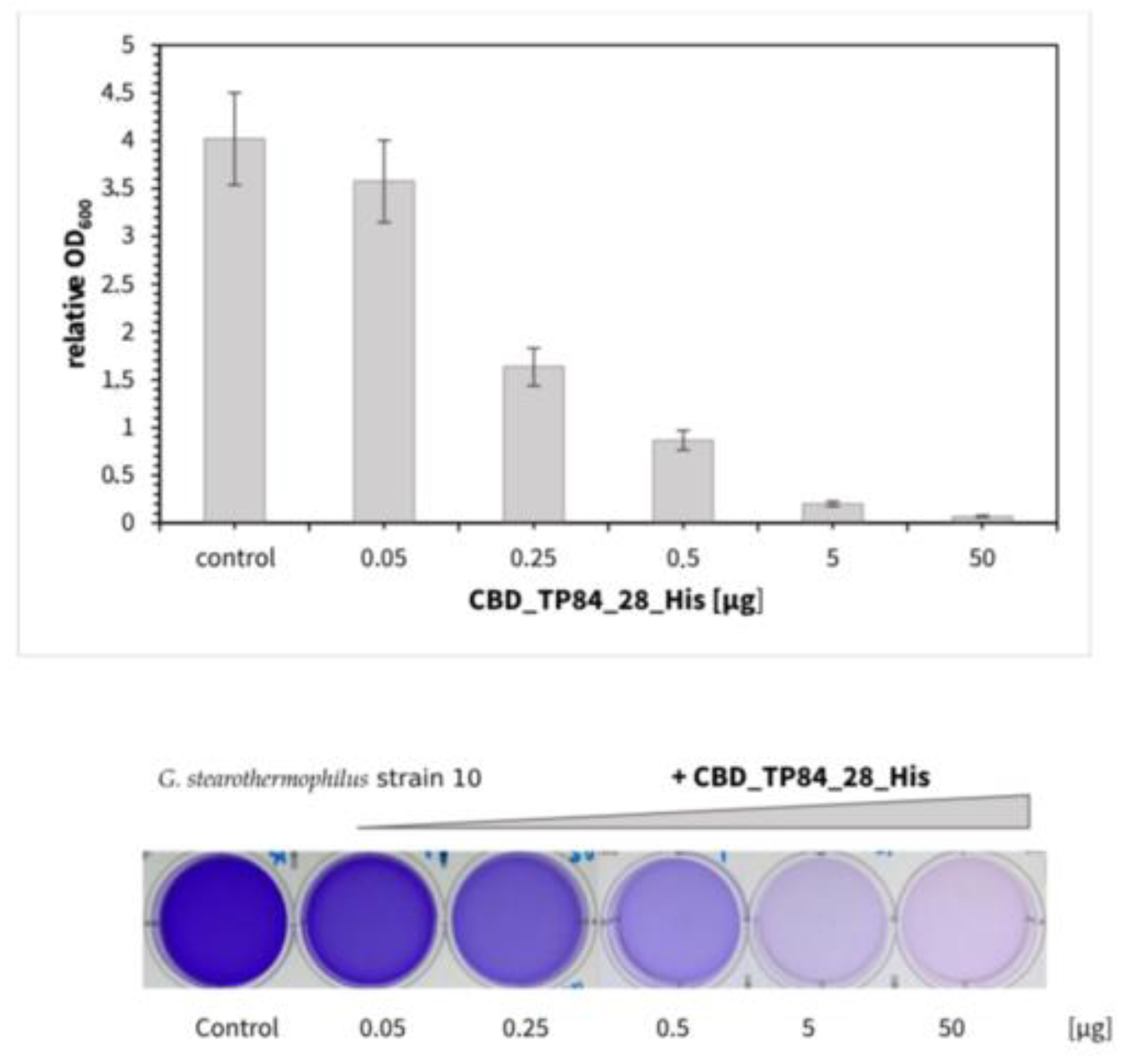

2.2.3. Lytic Activity of the Recombinant Fusion Endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His Against Biofilm

- Inhibition of the biofilm formation by G. stearothermophilus strain 10

- Inhibition of biofilm formation by mesophilic pathogenic-related bacteria

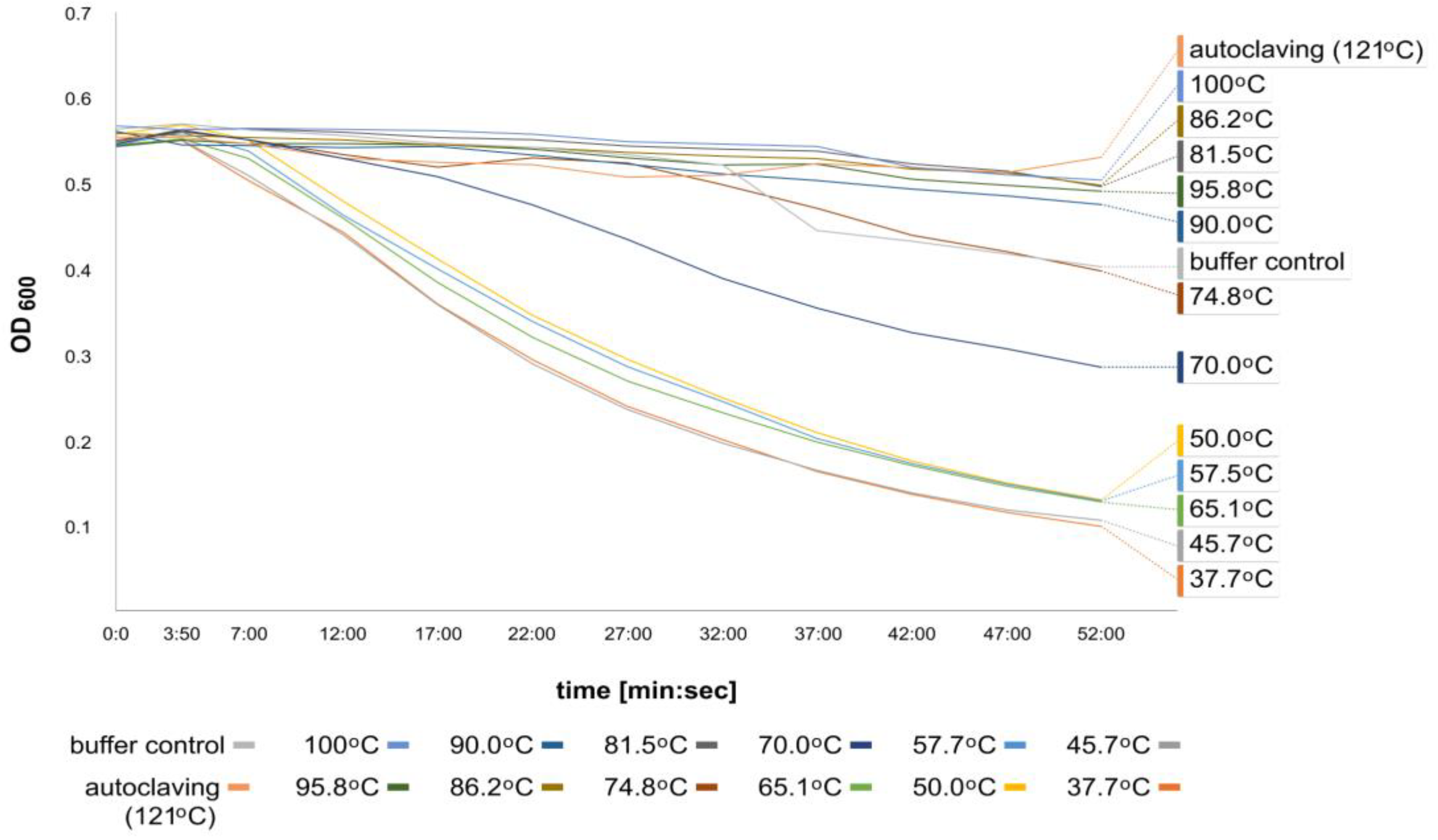

2.2.4. Thermostability of the Recombinant Fusion Endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His

2.2.5. Cellulose- Binding Properties of the Recombinant Fusion Endolysin CBD_TP84_28

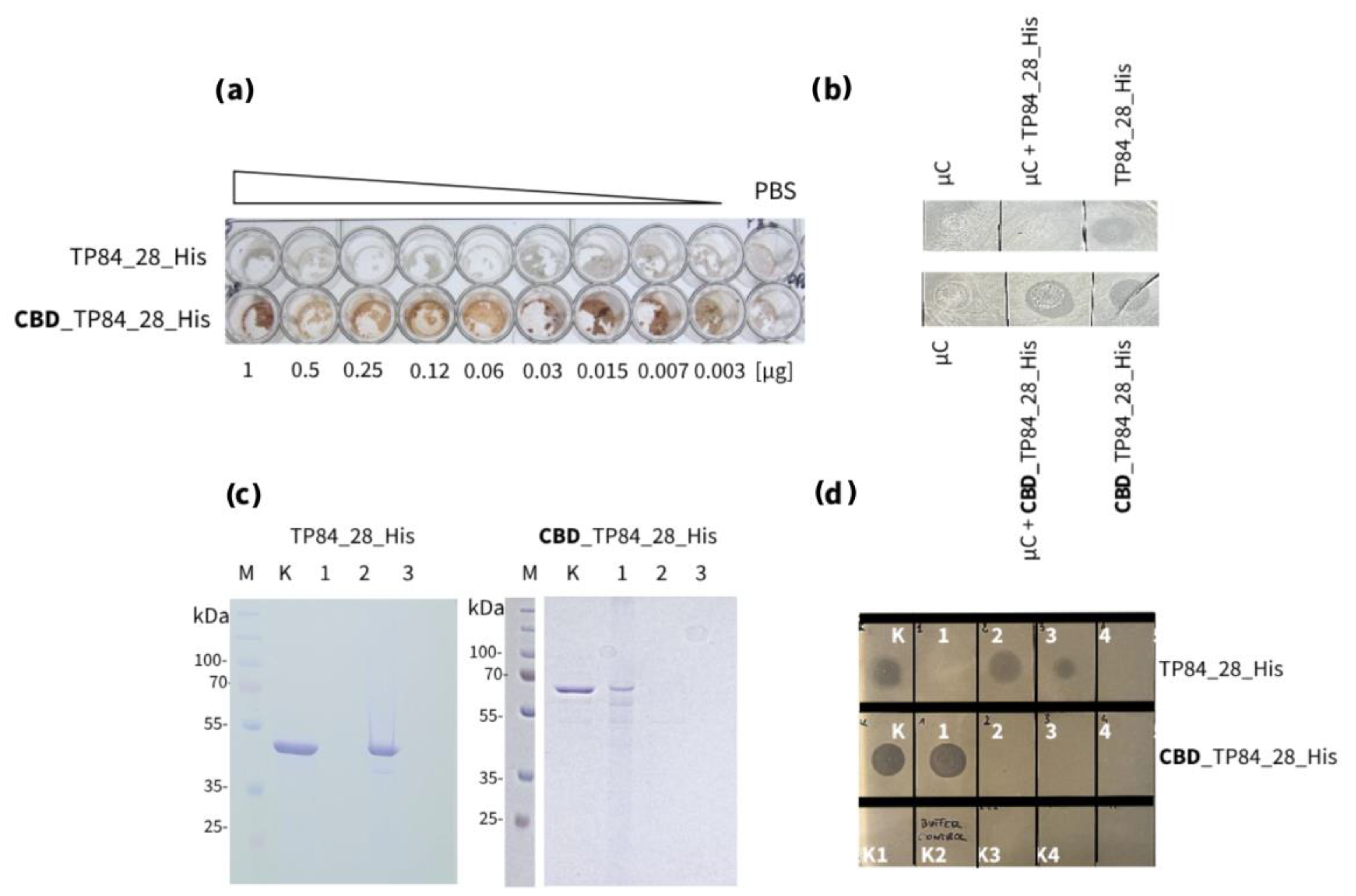

- Interaction with microcellulose (µC) assayFigure 7. Interactions comparison of recombinant endolysin TP84_28_His and recombinant fusion endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His with µC. Panel (a) Binding of TP84_28_His and CBD_TP84_28_His to µC in a 96-well plate using detection of His-tag for Western blots (Method 2.2.3.1). Both proteins have a His-tag that is located at the C-terminus, which allows for detection of the protein attached to the µC using anti-His antibodies. Panel (b) Dot blot assay of endolysin activity using the host G. stearothermophilus strain 10. A control - µC i 1 x PBS dot applied, µC complex formed with each of the enzymes: TP84_28_His and CBD_TP84_28_His were applied to the agar plate with spread G. stearothermophilus strain 10. Panel (c) SDS-PAGE comparative analysis of the formation of insoluble µC complexes with CBD_TP84_28 and with TP84_28_His. Lane M, PageRuler Plus Stained Protein Ladder; lane K, untreated TP84_28_His (left)/CBD_TP84_28 (right); lane 1, insoluble µC complex formed with TP84_28_His (left)/CBD_TP84_28_His (right); lane 2, supernatants of complexes formation – unbound protein; lane 3, washing supernatant of the complexes with 1 x PBS. Panel (d) µC complex formed with each of the enzymes: TP84_28_His and CBD_TP84_28_His were applied to the agar plate with spread G. stearothermophilus strain 10 to measure µC complexes activity; dot K, TP84_28_His/CBD_TP84_28_His; dot 1, formed and washed µC complexes with TP84_28_His/CBD_TP84_28_His; dot 2, supernatants of insoluble µC complexes formation; dot 3, washes of the complexes with 1 x PBS; dots 4, first washes of the complex with water.Figure 7. Interactions comparison of recombinant endolysin TP84_28_His and recombinant fusion endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His with µC. Panel (a) Binding of TP84_28_His and CBD_TP84_28_His to µC in a 96-well plate using detection of His-tag for Western blots (Method 2.2.3.1). Both proteins have a His-tag that is located at the C-terminus, which allows for detection of the protein attached to the µC using anti-His antibodies. Panel (b) Dot blot assay of endolysin activity using the host G. stearothermophilus strain 10. A control - µC i 1 x PBS dot applied, µC complex formed with each of the enzymes: TP84_28_His and CBD_TP84_28_His were applied to the agar plate with spread G. stearothermophilus strain 10. Panel (c) SDS-PAGE comparative analysis of the formation of insoluble µC complexes with CBD_TP84_28 and with TP84_28_His. Lane M, PageRuler Plus Stained Protein Ladder; lane K, untreated TP84_28_His (left)/CBD_TP84_28 (right); lane 1, insoluble µC complex formed with TP84_28_His (left)/CBD_TP84_28_His (right); lane 2, supernatants of complexes formation – unbound protein; lane 3, washing supernatant of the complexes with 1 x PBS. Panel (d) µC complex formed with each of the enzymes: TP84_28_His and CBD_TP84_28_His were applied to the agar plate with spread G. stearothermophilus strain 10 to measure µC complexes activity; dot K, TP84_28_His/CBD_TP84_28_His; dot 1, formed and washed µC complexes with TP84_28_His/CBD_TP84_28_His; dot 2, supernatants of insoluble µC complexes formation; dot 3, washes of the complexes with 1 x PBS; dots 4, first washes of the complex with water.

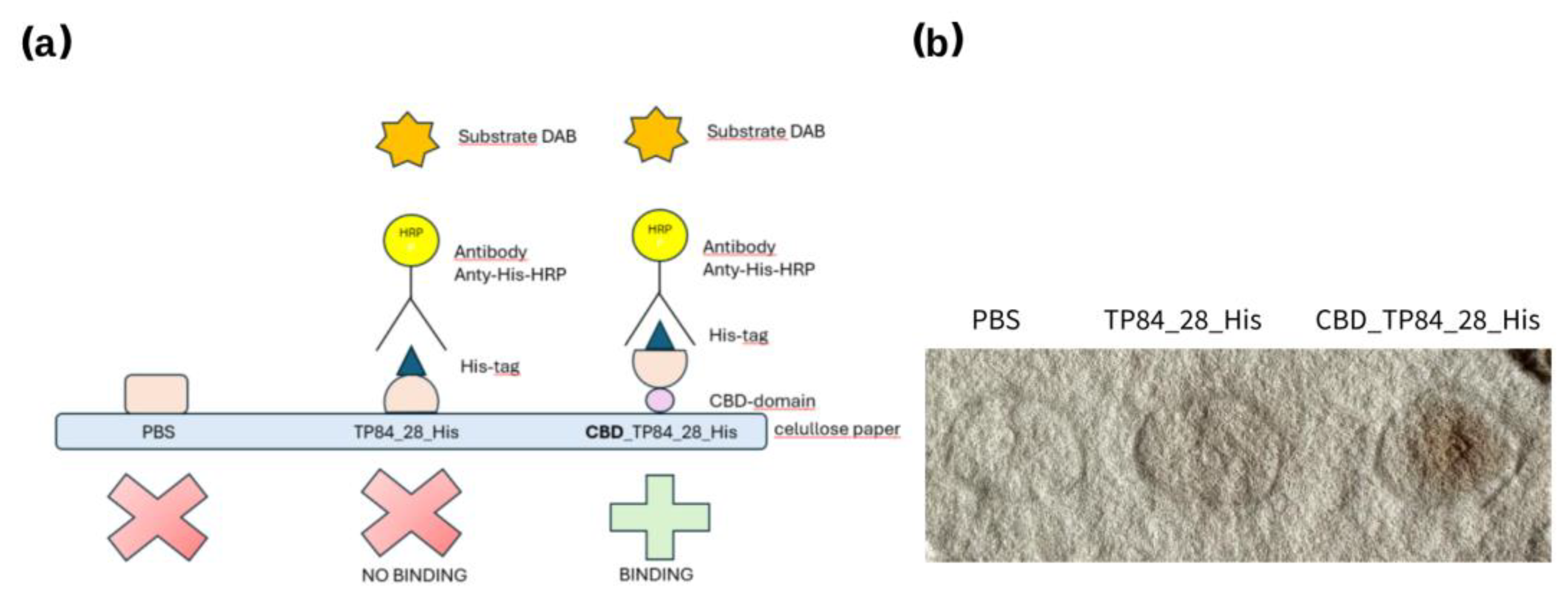

- Cellulose paper-based immunoblottingFigure 8. CBD_TP84_28_His interaction with cellulose paper: (a) scheme showing CBD-domain binding to cellulose filter paper and how His-Tag binds with anti-His-HRP antibody, which enables visualisation of the reaction after colour development using DAB. (b) cellulose filter paper with spots: PBS buffer (control), TP84_28_His and CBD_TP84_28_His.Figure 8. CBD_TP84_28_His interaction with cellulose paper: (a) scheme showing CBD-domain binding to cellulose filter paper and how His-Tag binds with anti-His-HRP antibody, which enables visualisation of the reaction after colour development using DAB. (b) cellulose filter paper with spots: PBS buffer (control), TP84_28_His and CBD_TP84_28_His.

3. Discussion

- (i)

- the specificity of the CBD_TP84_28_His appears to depend both on the thermophilicity and phylogenetic relatedness of the bacteria

- (ii)

- the structure of peptidoglycan varies substantially across Bacillus bacterial species

- (iii)

- the structure of peptidoglycan of the tested thermophiles has common features, sensitive to the CBD_TP84_28_His

- (iv)

- differences in external polysaccharide envelopes may play an important role, preventing the enzyme access to the cell wall.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains, Media, Reagents, DNA, SOFTWARE and devices

4.2. Construction, Expression and Purification of Fusion Endolysin - CBD_TP84_28_His

4.2.1. Cloning tp84_28 Gene into pET28_delSapI_CBD_His Vector

4.2.2. Gene Expression and Overproduction of CBD_TP84_28_His

4.2.3. Recombinant Fusion Endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His Purification

4.3. Characterization of Recombinant Fusion Endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His

4.3.1. Evaluation of the Lytic Activity of CBD_TP84_28_His

- Spot assay (diffusion test)

- Turbidity reduction assay (spectrophotometer variant)

- Turbidity reduction assay (Tecan microplate reader variant)

- Inhibition of the biofilm formation by the recombinant fusion endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His

4.3.2. Evaluation of the Thermostability of Recombinant Fusion CBD_TP84_28_His

4.3.3. Cellulose- Binding Properties of Recombinant Fusion Endolysin CBD_TP84_28_His

- Interaction with microcellulose assay

- Cellulose paper-based immunoblotting assay

5. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. About Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/about.html (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Liu, H.; Hu, Z.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Lu, S.; Rao, X. Therapeutic potential of bacteriophage endolysins for infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 30, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladskin, EU. Microbiome-balancing skincare | endolysin science | Gladskin. Available online: https://www.gladskin.eu/collections/staphefekt (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Briers, Y.; Walmagh, M.; Grymonprez, B.; Biebl, M.; Pirnay, J.P.; Defraine, V.; Michiels, J.; Cenens, W.; Aertsen, A.; Miller, S.; Lavigne, R. Art-175 is a highly efficient antibacterial against multidrug-resistant strains and persisters of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3774–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grishin, A.V.; Karyagina, A.S.; Vasina, D.V.; Vasina, I.V.; Gushchin, V.A.; Lunin, V.G. Resistance to peptidoglycan-degrading enzymes. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 703–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.U.; Wang, W.; Sun, Q.; Shah, J.A.; Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Chen, W.; Wang, S. Endolysin, a promising solution against antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, A.; Mayer, C. Peptidoglycan structure, biosynthesis, and dynamics during bacterial growth. In Extracellular Sugar-Based Biopolymers Matrices. Biologically-Inspired Systems, vol 12; Cohen, E., Merzendorfer, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, M.; Ross, P.; McAuliffe, O.; O'Mahony, J.; Coffey, A. Recombinant bacteriophage lysins as antibacterials. Bioeng. Bugs 2010, 1, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Guo, Q.; Li, Z.; Guo, X.; Liu, X. Bacteriophage endolysin: A powerful weapon to control bacterial biofilms. Protein J. 2023, 42, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, H.; Ryu, S. Bacteriophage and endolysin engineering for biocontrol of food pathogens: recent advances and future trends. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 8919–8938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żebrowska, J.; Żołnierkiewicz, O.; Ponikowska, M.; Puchalski, M.; Krawczun, N.; Makowska, J.; Skowron, P.M. Cloning and characterization of a thermostable endolysin of bacteriophage TP-84 as a potential disinfectant and biofilm-removing biological agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, G.F.; Campbell, L.L. Characterization of a thermophilic bacteriophage for Bacillus stearothermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 1966, 91, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, I.; Campbell, L.L. Production and purification of the thermophilic bacteriophage TP-84. Appl. Microbiol. 1975, 29, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łubkowska, B.; Jeżewska-Frąckowiak, J.; Sobolewski, I.; Skowron, P.M. Bacteriophages of thermophilic Bacillus group bacteria - a review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żebrowska, J.; Witkowska, M.; Struck, A.; Laszuk, P.E.; Raczuk, E.; Ponikowska, M.; Skowron, P.M.; Zylicz-Stachula, A. Antimicrobial potential of the genera Geobacillus and Parageobacillus, as well as endolysins biosynthesized by their bacteriophages. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowron, P.M.; Kropinski, A.M.; Żebrowska, J.; Janus, L.; Szemiako, K.; Czajkowska, E.; Maciejewska, N.; Skowron, M.; Łoś, J.; Łoś, M.; Zylicz-Stachula, A. Sequence, genome organization, annotation and proteomics of the thermophilic, 47.7-kb Geobacillus stearothermophilus bacteriophage TP-84 and its classification in the new Tp84 virus genus. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, P.M.; Łubkowska, B.; Sobolewski, I.; Zylicz-Stachula, A.; Šimoliūnienė, M.; Šimoliūnas, E. Bacteriophages of thermophilic 'Bacillus Group' bacteria: A systematic review, 2023 update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoseyov, O.; Takagi, M.; Goldstein, M.A.; Doi, R.H. Primary sequence analysis of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose binding protein A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 3483–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouhmad, A.; Mamo, G.; Dishisha, T.; Amin, M. A.; Hatti-Kaul, R. . T4 lysozyme fused with cellulose-binding module for antimicrobial cellulosic wound dressing materials. Journal of applied microbiology 2016, 121, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.; Draper, L.A.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C. The advantages and challenges of using endolysins in a clinical setting. Viruses 2021, 13, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontijo, M.T.P.; Jorge, G.P.; Brocchi, M. Current status of endolysin-based treatments against Gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gu, J.; Lv, M.; Guo, Z.; Yan, G.; Yu, L.; Du, C.; Feng, X.; Han, W.; Sun, C.; Lei, L. The antibacterial activity of E. coli bacteriophage lysin Lysep3 is enhanced by fusing the Bacillus amyloliquefaciens bacteriophage endolysin binding domain D8 to the C-terminal region. J. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysando. Lysando-Brochure-Digital. Available online: https://www.lysando.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Lysando-Brochure-Digital.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Zampara, A.; Sørensen, M.C.H.; Grimon, D.; Antenucci, F.; Vitt, A.R.; Bortolaia, V.; Briers, Y.; Brøndsted, L.

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Otto, M. The staphylococcal exopolysaccharide PIA - biosynthesis and role in biofilm formation, colonization, and infection. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 3324–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, N.; Zheng, Y.; Opoku-Temeng, C.; Du, Y.; Bonsu, E.; Sintim, H.O. Biofilm formation mechanisms and targets for developing antibiofilm agents. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siondalski, P.; Kołaczkowska, M.; Bieńkowski, M.; Pęksa, R.; Kowalik, M.M.; Dawidowska, K.; Vandendriessche, K.; Meuris, B. Bacterial cellulose as a promising material for pulmonary valve prostheses: In vivo study in a sheep model. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B: Appl. Biomater. 2024, 112, e35355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marangoz, B.; Kahraman, S.; Bostan, K. Bacillus spp. responsible for spoilage of dairy products. Int. J. Food Eng. 2018, 4, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- André, S.; Vallaeys, T.; Planchon, S. Spore-forming bacteria responsible for food spoilage. Res. Microbiol. 2017, 168, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żebrowska, J.; Mucha, P.; Prusinowski, M.; Krefft, D.; Żylicz-Stachula, A.; Deptuła, M.; Skoniecka, A.; Tymińska, A.; Zawrzykraj, M.; Zieliński, J.; Pikuła, M.; Skowron, P.M. Development of hybrid biomicroparticles: cellulose-exposing functionalized fusion proteins. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yang, S.; Al-Dossary, A.A.; Broitman, S.; Ni, Y.; Guan, M.; Yang, M.; Li, J.; et al. Nanobody-functionalized cellulose for capturing SARS-CoV-2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0230321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacteria | Control [OD600] | Treatment [OD600] | Reduction [%] |

| E. coli (DSM 1103) | 5.4 | 3.3 | 39 |

| S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 1.6 | 0.3 | 81 |

| P. aeruginosa (ATCC 17503) | 14.9 | 8.6 | 42 |

| S. enteritidis (ATCC 25928) | 0.14 | 0.09 | 34 |

| B. cereus (DSM 31) | 11.9 | 8.0 | 33 |

| Control | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).