7.1. Precise Decoupling

Let it be a constant air-gap machine with a multiphase winding in the stator and another in the rotor. The theoretical assumptions are the same as in chapter 10 of [

6], but eliminating the hard restriction of sinusoidal air-gap induction, that is, the windings do not have, as postulated in [

6], an unreal and ideally sinusoidal distribution in space, on the contrary, all the air-gap induction harmonics produced by them are taken into account. (Note in passing that, consistent with this fact, the analysis field of the SPhTh goes far beyond the one in [

6]). The phases of each winding are, as in [

6], equal, and symmetrically and evenly spaced (the angle between any two consecutive is

2π/m).

In a symmetrical machine without homopolar components and

mstr=mrot = 3, there is in the stator winding (the same applies to rotor) only one

DmPhS of flux linkages and another one of voltages, with the sequence g=1. Therefore, all the individual magnetic vector potential and electric potential difference space waves in stator, no matter their changes of amplitude and speed (arbitrary transients)

must produce

DmPhS´s of this sequence. In a

m-phase winding, however, there are several

DmPhS´s of

Ψ and

U, which are mathematically and graphically fully characterized by their corresponding dynamic phasors

. Since these

DmPhS´s are independent of each other, as underlined at the end of

Section 4, there

must be groups of space waves, which are also independent of each other, and which produce the existing

DmPhS´s. This is one of the main

physical ideas underlying the paper [

15] to untangle the intricate structure of the multiphase machine and address the problem of its possible decoupling.

Applying the key concept of a

DmPhS of

g sequence, or, better expressed, on the base of the

DmPhS´s of flux linkages and voltages that they produce in a multiphase IM, the field harmonics of its stator winding (the same applies to rotor)

must necessarily be distributed among several

independent groups. And this, indeed, has been mathematically proven in the SPhTh ([

15], page 85). The relative order,

h, of the harmonics belonging to the same group meet the equation

h=qm ± g. According to this fact, it is evident that, if

mstr ≠ mrot, the decoupling of the multiphase machine by pairs of homologous groups of stator and rotor space waves is mathematically impossible. The reason is, simply, that the field harmonics belonging to one only stator waves group have their rotor counterparts distributed among several rotor groups; and conversely.

The condition

mstr = mrot, required for a precise machine decoupling, theoretically deduced in the preceding paragraphs, has also been checked with the help of a very complete program [

19]. This program starts from the groundwork of the one used in [

15], based on the SPhTh, but it is more powerful and much more versatile and faster. It can simulate transients of multiphase IM´s not only in healthy conditions, as was the case in [

15], but also with any kind of rotor failures. In fact, the program has been applied in [

20] to end-ring failures and its simulations have been tested and confirmed by failure measurements in real industrial installations. In this work, the simpler program variant of healthy motor is the one applied and consist of a dynamic model of an IM with constant air-gap, ideal magnetic circuit and arbitrary number of air-gap harmonics produced by the windings. The program has been implemented using MATLAB in a PC with an Intel Core i7-8700 processor and solved using a fourth-order Runge–Kutta method with a simulation step size of 10

−4.

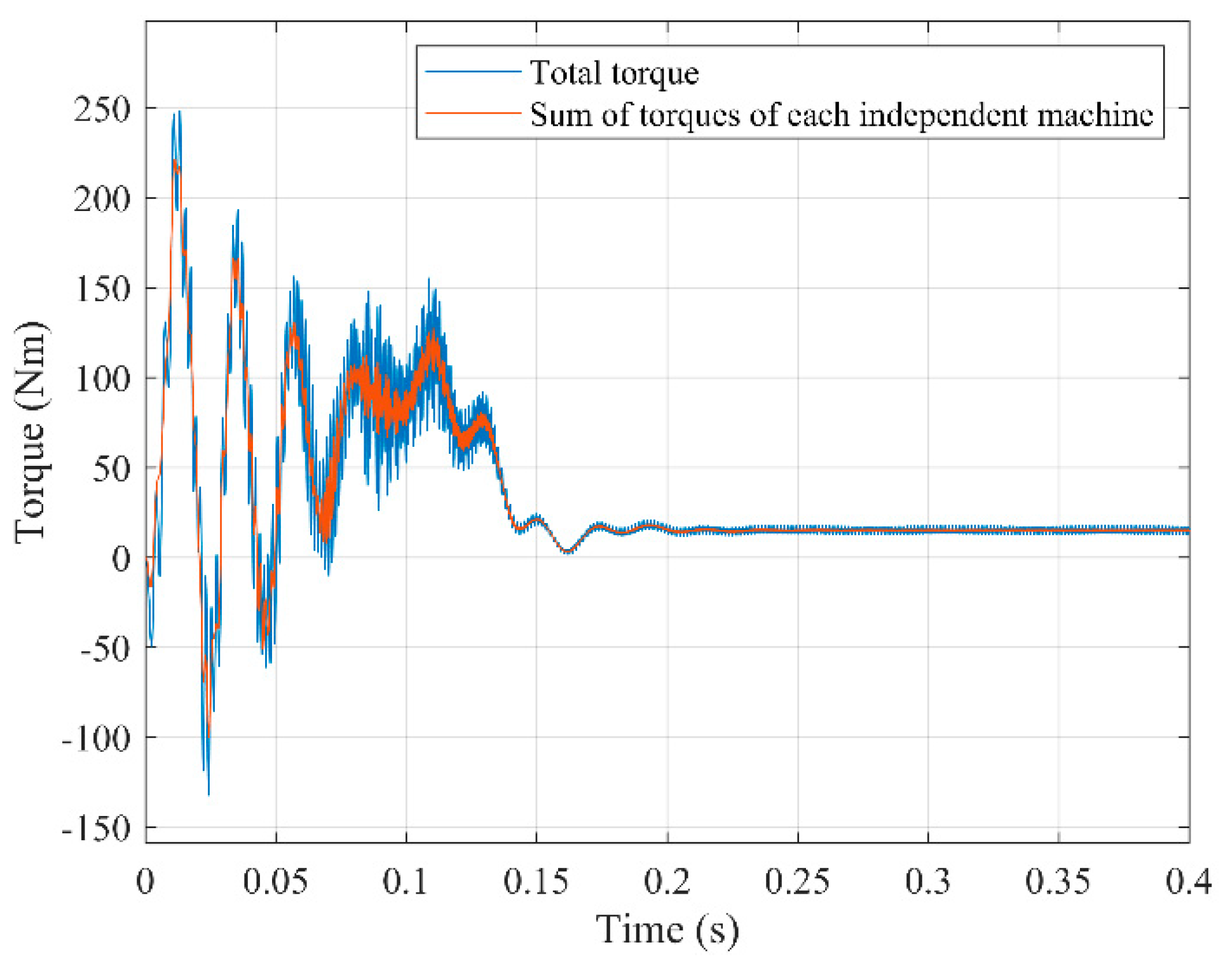

The verification procedure is based on the second approach described at the end of the previous section. Thus, first, the model is input with a voltage system sum of (mstr-1)/2 DmPhS’s of different g sequences, giving as output the total motor torque. Next, the same model is fed with each of these DmPhS’s separately, giving as output the motor torque for each case. Finally, these torques are summed and compared to the total torque. If both results overlap it means that both systems are equivalent, or in other words, that the m-phase machine can be decoupled into a set of (m-1)/2 electrically independent but mechanically coupled machines. Notice too that each of these machines can be treated as a three-phase machine in terms of the SPhTh, since only one effective space phasor is sufficient to characterize the action of all the waves of a given space quantity (e.g., Ψ for magnetic vector potential waves, U for scalar electric potential difference waves and I for current linear density waves).

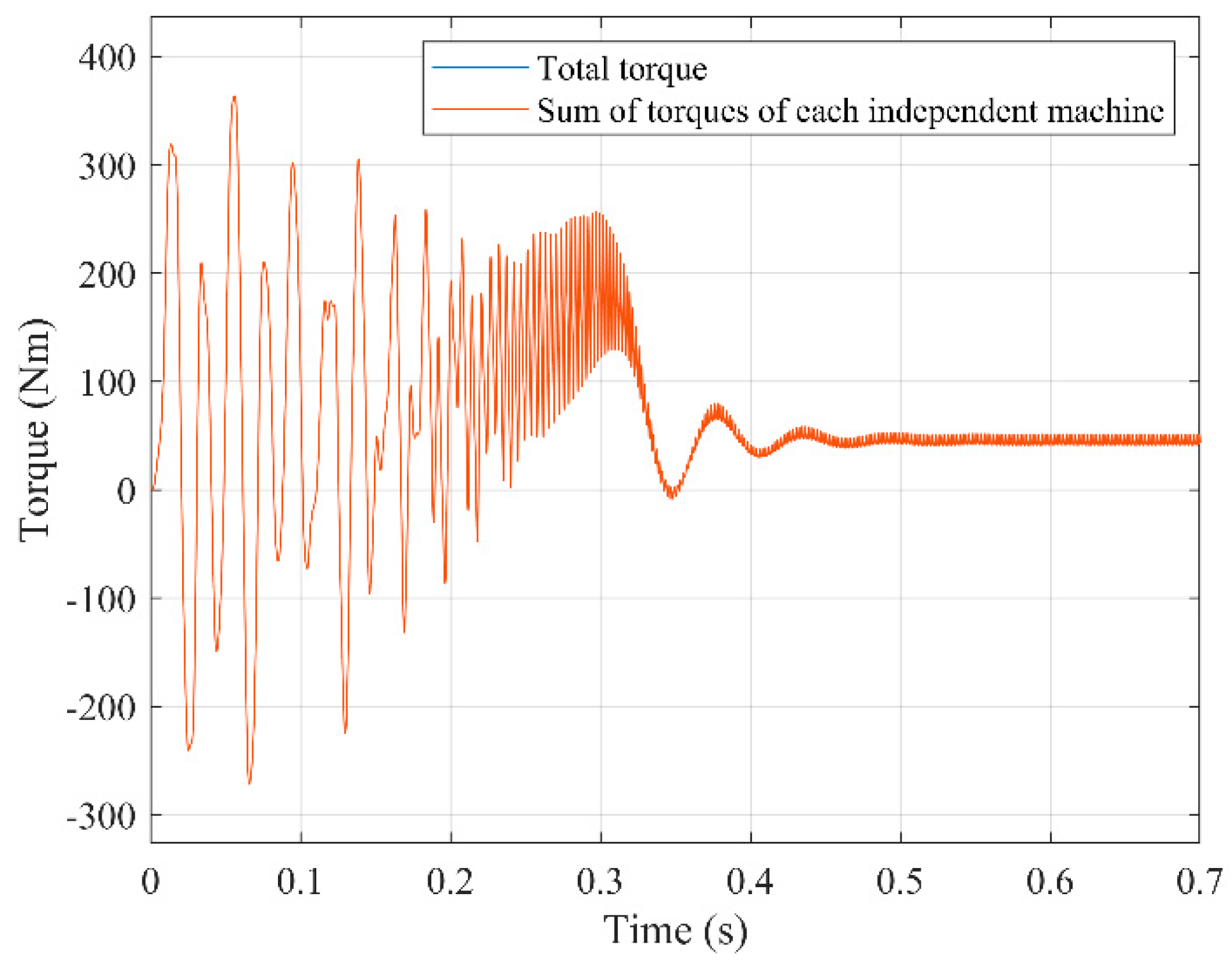

Figure 6 shows the application of this procedure to the direct start-up under constant load torque of a wound induction motor (data in

Appendix A) with

p=2 and

mstr=mrot=5, being the voltage

DmPhS’s:

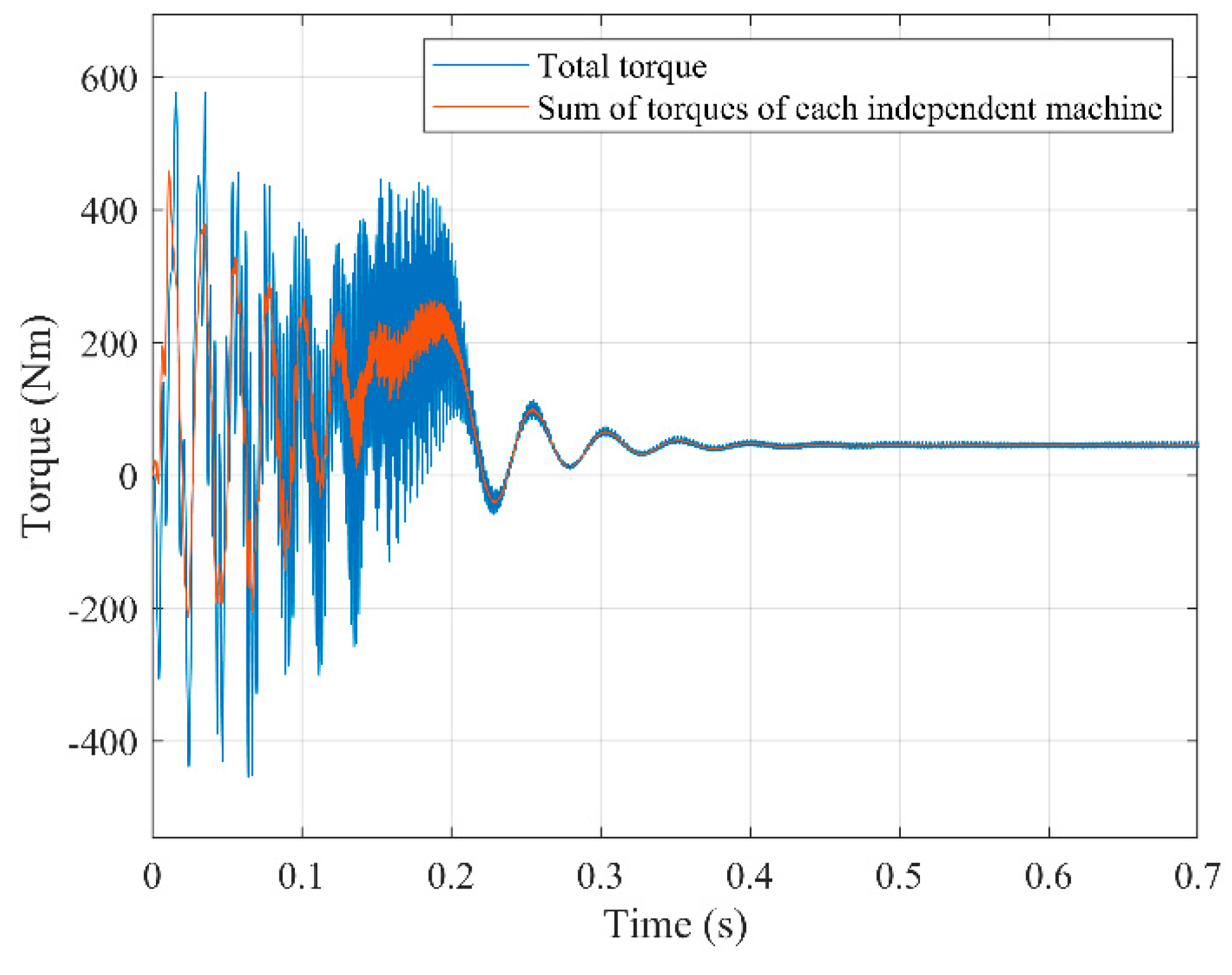

As can be seen, the electromagnetic torque is exactly equal in both cases (red graph overlapping the blue one). However, if the number of rotor phases is changed to 7, then

Figure 7 shows that both torques clearly differ, meaning that the machine cannot be decoupled by pairs of homologous groups of stator and rotor space waves. As mentioned before, the reason is that the field harmonics belonging to a given stator group have their rotor counterparts distributed among several rotor groups. For example, in this case, the field harmonic of relative order h=9 belongs to the group of g = ±1 in the stator, while in the rotor it appears in the group of

g = ±2. Similar discrepancies occur with many other harmonics as well.

The previous conclusions also apply, of course, to squirrel-cage motors. In this type of machine, assuming the almost universal case of

B/p integer, the rotor can be regarded as a system of

B/p phases, where

B is the number of rotor bars and

p the number of pole pairs.

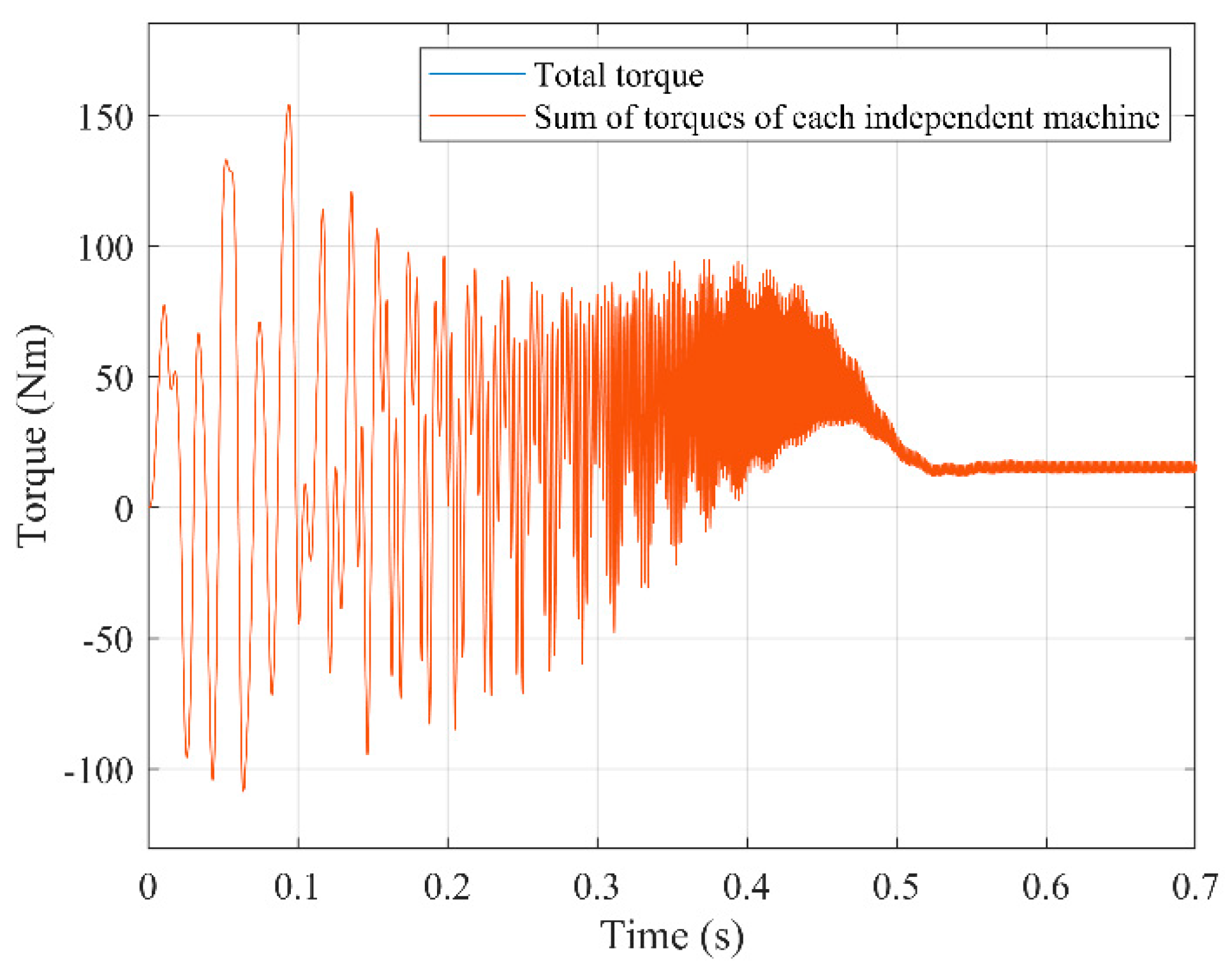

Figure 8 shows the application of the mentioned procedure to a squirrel-cage motor with 14 bars,

p=2, mstr=7 and

mrot=14/2=7, (remaining data in

Appendix A) being the

DmPhS’s:

As in the case of the wound induction motor, when the condition of

mstr=mrot holds, there is also a perfect match between the torque resulting of feeding the machine with all the

DmPhS’s simultaneously, and that obtained as the sum of torques when the machine is fed with each of the

DmPhS’s separately. Likewise, when the condition is not satisfied, for example, if the number of rotor bars is increased to 22, the decoupling of the machine is mathematically impossible, as shown in

Figure 9.

Thanks to the fast computation time of the program (typically around 25s for a 0.5s simulation), tens of simulations have been conducted with very different machines. Moreover, the input phase voltages had not only a sinusoidal, but also an arbitrary time evolution, expressed as sums of functions that meet (3). In all cases, the simulations confirmed the aforementioned conclusions.

In summary, as first deduced theoretically and then confirmed by tens of simulations (and shown for the first time in this paper, as far as the authors know), the condition for a machine decoupling both precise and valid for the whole working region (arbitrary slips) is that the equality mstr = mrot is fulfilled.

Since in almost all squirrel cage motors, mstr ≠ mrot, their decoupling, if at all possible, can only be appoximate and, most probably, only within a restricted working region. This issue is addressed in the next section.

7.2. Approximate Decoupling Within a Narrow Working Region—Equations of the Multiphase Machine

Let us start, in a first step, from a machine with

m phases in stator and rotor. For each one of its fictitious machines, related to each group “

g” of harmonic space waves, the voltage of any of its stator or rotor phases,

K, must be equal to its resistive voltage drop plus the time derivative of its flux linkages, that is (

x = stator or rotor):

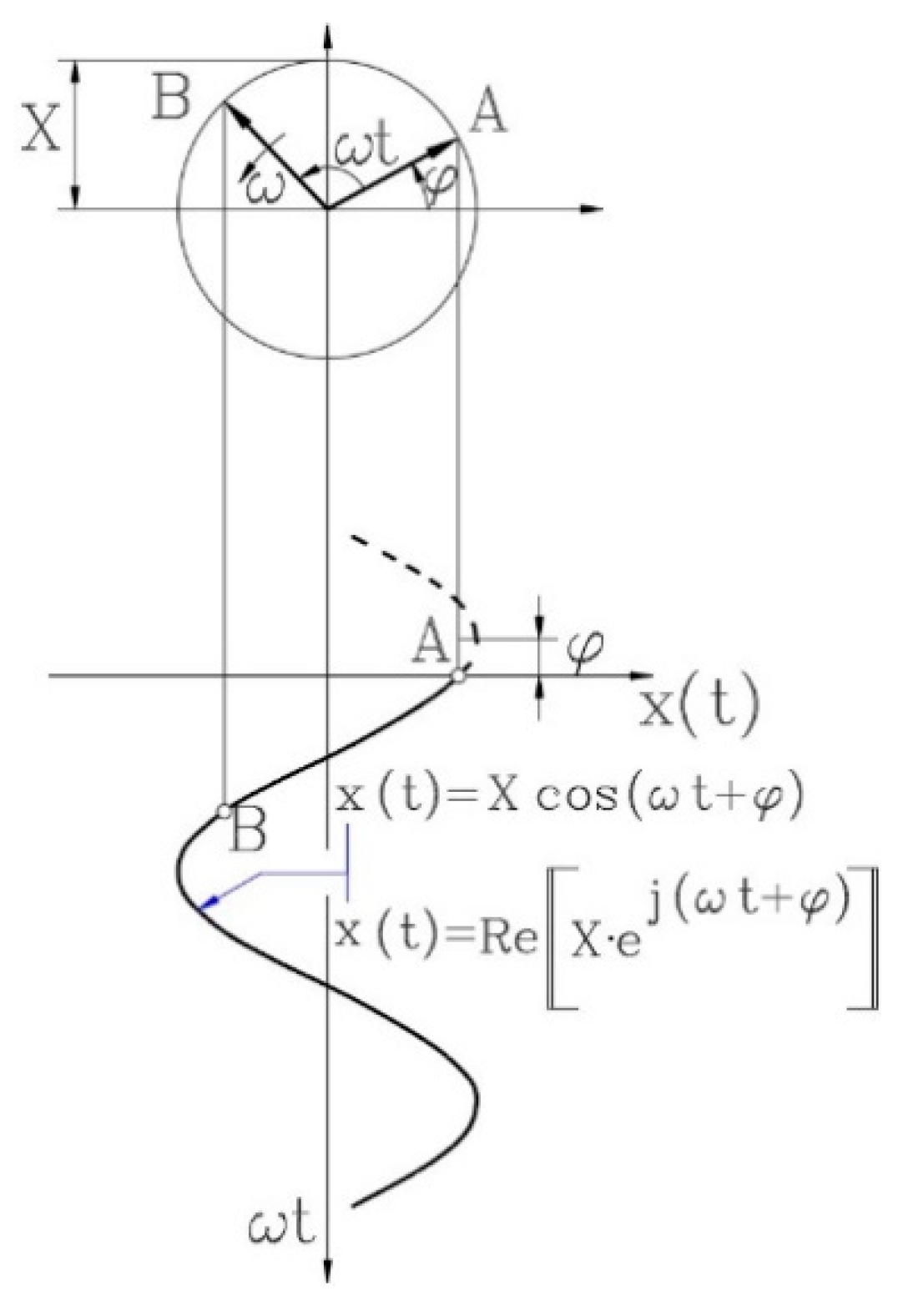

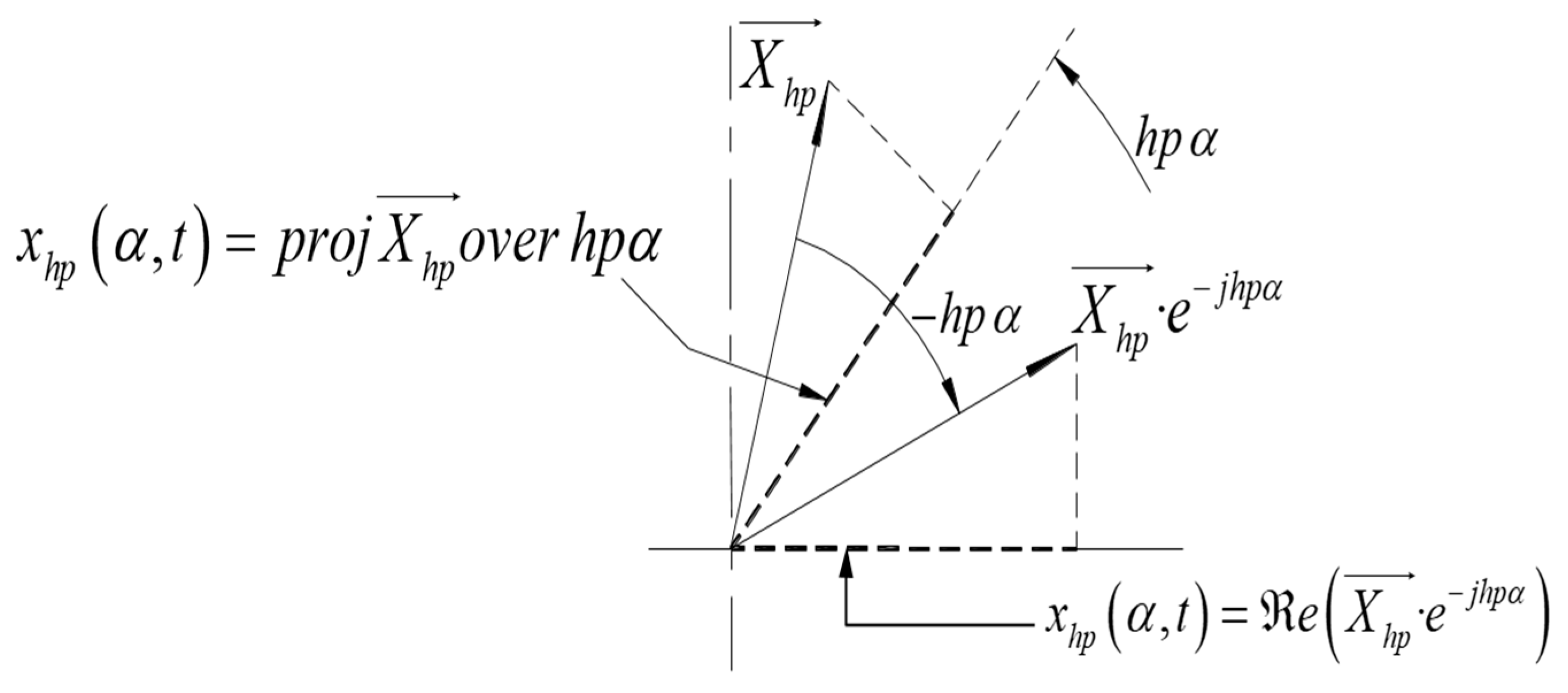

Expressing these three

time quantities by means of the projections of their corresponding

space phasors onto the phase axis (see section 6, especially third bullet point (c) of that section), (20) turns into:

Since (21) is valid for any instant of time, any phase and for any number of phases, it follows for each one of the fictitious machines:

Equations (21) and (22) highlight two key advantages of the SPhTh:

- (a)

Space phasors provide a deep physical insight into the machine behavior. This enables to "untangle" its complex structure, and it is just this previous knowledge that allows to directly write the equations of the machine with space harmonics as the ones of a set of electrically independent machines. Without this knowledge, the machine has to be analyzed as a single global system with a very intricate structure.

- (b)

The very powerful step from (20) to equations (21) – (22) is extremely simple and straightforward.

In [

21]

very precise measurements of transient harmonic torques in three-phase

IM´s connected to the mains were carried out. In addition to the measurements, it was also theoretically justified and confirmed by numerous simulations that the field harmonics effect on the machine torque may be very important in several industrial transients, like start up, unplugging, drop out, injection braking, etc. Yet, it was also proven that this effect is always negligible

at low slips of the machine. This conclusion is also deduced in [

22], page 208, using a quite different reasoning, and can be extended, with even more reason, to each wave group of the multiphase machine. This implies that in converter-controlled multiphase machines (always small slips, even in transients)

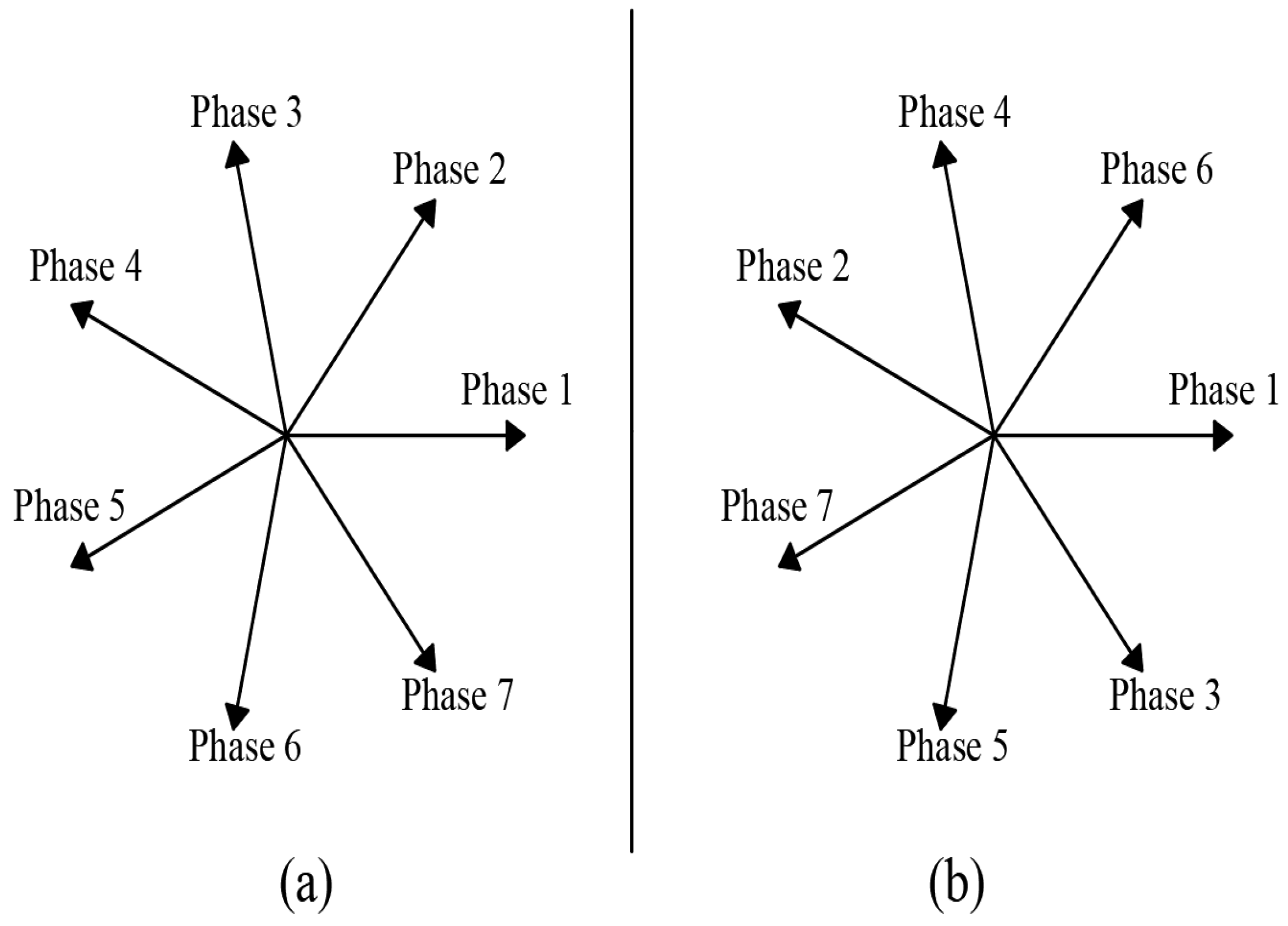

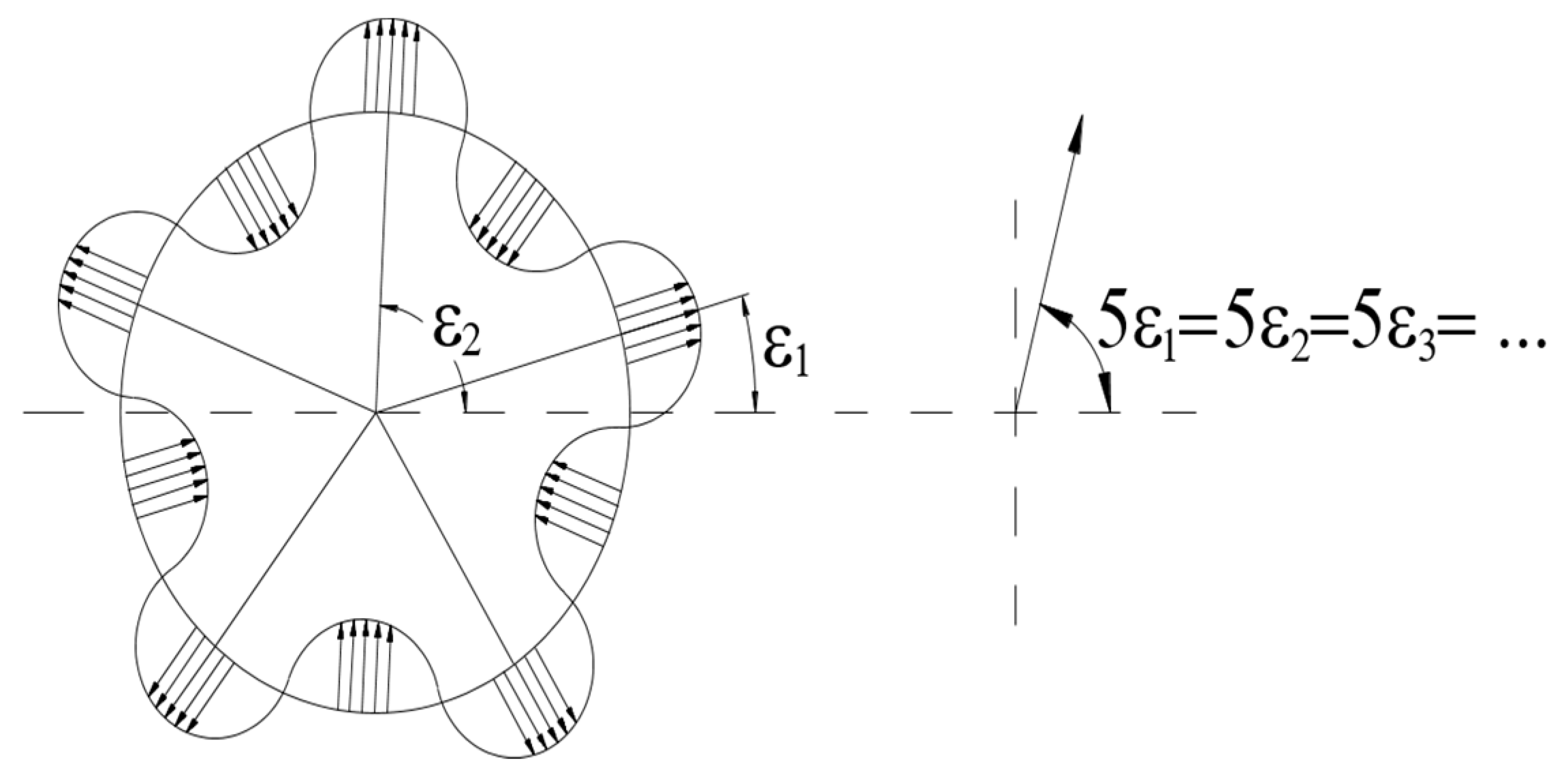

it is acceptable to assume that only the space harmonics which are head members of their groups, that is, the harmonics with the lowest pole number, need to be considered. (e. g., for a 5-phase machine – which only has two groups – harmonics 1 and 3. For a 7-phase machine, harmonics 1, 3 and 5, etc.).

To reinforce and check the above conclusion from a different perspective, it is very useful to have a look at the, in the author’s opinion, valuable paper [

23]. In it, the authors present a theoretical framework of analysis using matrix transformations. Relying on it, and in order to show through a practical example that in any induction (or more precisely: in any constant air-gap) multiphase machine the decoupling is always possible, they choose a machine with seven phases in the stator. They start then from the assumption that in this case “the flux produced by the rotor in the stator winding has a fundamental, a third and a fifth harmonic component” ([

23], page 336), but without giving any mathematical proof or physical explanation that justify it. So, one has the right to ask: why choose just and only these three harmonics? What is the reason for not choosing, e.g., the first seven machine harmonics or other combinations? (In these other cases one can verify that there is no longer any decoupling). Likewise, when applying their procedure to a 5-phase machine, only the first and third harmonics may be present in order to achieve decoupling. And so on.

The useful and correctly proven decoupling of induction machines in the valuable paper [

23] is actually based on the unstated assumption that only the space harmonics which are precisely the head members of the groups established in the SPhTh produce torque.

Yet, this assumption is only acceptable for the narrow region of small slips ([

21], page 74, [

22], page 208). Thus, it is only this assumption that allows the approximate, but very practical decoupling of converter-controlled multiphase induction machines (always small slips, even in transients) by means of

(m-1)/2 pairs of independent space harmonics. Moreover, in contrast to

Section 7.1, in the particular case now under consideration, the decoupling does apply also to the structure

mstr ≠ mrot. Indeed, even when

mstr ≠ mrot, any pair of homologous stator and rotor

head members is independent of all other analogous pairs, and it is only these pairs that produce torque in this case. Notice that the validity of an approximate decoupling at low slips is also clearly confirmed by

Figure 7 and

Figure 9: when the motor is close to steady state, the blue and red graphs practically overlap each other. Yet, out of this small region, if

mstr ≠ mrot , as is the case with virtually all the squirrel cage motors, there is an important cross coupling between stator and rotor space waves that belong to different groups, as proven in the SPhTh [

15] and as seen by comparing

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

Now, instead of using, as done in previous paragraphs, the straightforward and very “visual language” of groups of space waves, let us resort to the abstract language of “mathematical subspaces”. Precisely formulated in this language, the second and most important contribution or thesis of this paper is the following: the claim or the statements that the machine structure is always equivalent to a set of mutually orthogonal bidimensional subspaces with only one harmonic per subspace must be rejected. These statements, although accepted without objection in the literature for some 20 years, have never been mathematically proven. This could hardly have been done since, as shown in previous paragraphs, they only hold, and only approximately (although with very good approximation) in the narrow region of small slips.

In spite of that, and as already written in section 2, it would be unfair not to recognize the positive impact of the above statements on valuable applications of multiphase machines. Yet, one should be aware that it has been a lucky coincidence that, so far, the decoupling procedure based on them has been applied and verified only in the field of converter-controlled machines. Certainly, this is, at least nowadays, their overwhelmingly used and most important industrial field. Yet, a technological circumstance is no reason in science to sustain and present, without any proof, theoretical principles or statements as having general validity, when they only apply to a particular case.

Moreover (and worse, in our opinion) such an approach also makes impossible to physically understand and explain what are the true reasons why, despite the fact that those general statements are incorrect, there is nevertheless a particular field in which they do hold up. Likewise, it prevents a deep physical insight into the intricate machine structure and how to correctly untangle it.

Equation (22) fully describes the electric behavior of any one of the fictitious machines with all its winding space harmonics. As the input data in (22) are usually the phase voltages, the space phasor U of each fictitious machine is known, since U is, simply, one of the ISC of the phase voltages of the real machine. Thus, solving (22) requires determining the relationship between the space phasors I and Ψ (between currents and flux linkages, if we refer to their homologous time quantities). This is a very complicated task if the whole group of space harmonics of each fictitious machine has to be taken into account. Yet, in converter-controlled machines, since only the head harmonic of each group is considered, the mentioned relationship can be easily established for each fictitious machine through its inductances.

Indeed, in this case, mathematical content and structure of the stator (or rotor) equation (22) for any of the fictitious

m-phase machines, expressed in space phasors,

are the same as that of the electrical stator (or rotor) equation of a three-phase machine under analogous conditions (in both cases it is, simply, the very well-known IM in which there is stator-rotor magnetic coupling only through their main space waves. The influence of the remaining fields is included in the leakage inductances). But for three-phase machines, that have been, by far, the most usual and important industrial ones, the equation (22) and the relationship between the “space vectors”

I and

Ψ, under the above assumptions, have been known in the literature for a very long time. Therefore, there is no point in repeating here for each fictitious machine the well-known mathematical process leading to correlate phasors

Ψ and

I, a process that, for three-phase machines, can be seen in all detail, in pages 80-82 of [

8], the pioneering and nowadays a classic work on “space vectors”. In line with [

8], in a multiphase machine, the formulae for each one of its fictitious machine become:

with:

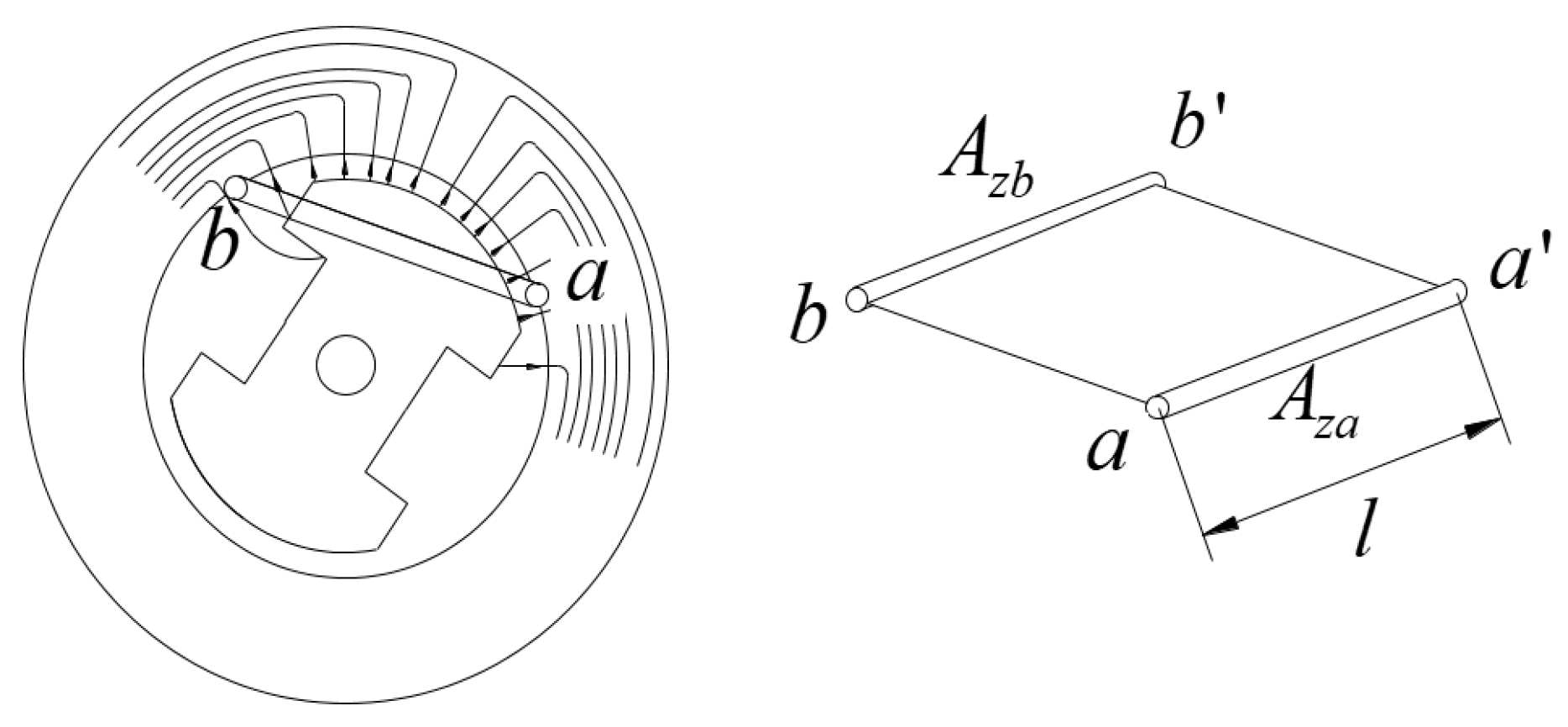

where

Lg,μ-x and

Lg,σ-x are (x = stator or rotor) the magnetizing and leakage inductance of one phase,

Lg,M the maximum mutual inductance between stator and rotor phases,

hg is the relative order of the head harmonic of the

g group of space waves and

λ is the rotor mechanical angle.

Replacing (23) and (24) in (22) the final stator and rotor electrical equations, expressed in space phasors, for any of these fictitious machines (formulae completely analogous to the ones of their equivalent three phase machines) are:

The terms U and I in each fictitious machine are, simply, one of the space phasors or, what is mathematically the same, one of the ISC of the voltages and currents of the real machine. The space waves, that is, the space phasors in (26), are given in their own system. Rotor (or stator) phasors are translated into the stator (or rotor) system by simply multiplying them (i. e. applying to them) the rotation (or ). In this connection, and with regard to the interpretation of (26), it is probably not superfluous to call the attention to the fact that, from a rigorous physical viewpoint (and thus for a deep insight into the machine phenomena too), only space quantities can be subjected to space coordinate changes.

The torque of each fictitious machine is given by:

where symbol

x stands here for vectorial product.

The mechanical equation of the real machine can then be expressed as:

Equation (27) is very enlightening and intuitive: it states that the torque in a machine is, simply, the tendency to align of two magnets (more precisely: of their equivalent stator and rotor current sheets expressed in a common reference frame).

Equations (26) and (27) also show another essential advantage of the SPhTh. Indeed, notice that no matter how high the stator and rotor phase number of each fictitious machine may be, its equation system has only three unknowns, two of which belonging to the bidimensional complex domain (the third one, λ, is a real variable). Thus, there is no need of abstract and long m-dimensional matrix transformations that, moreover, are usually introduced without any physical explanation or interpretation.

Obviously, through mere mathematical manipulations, one can express the equation system (26) and (27) using as variables

Istr and

Ψstr instead of

Istr and

Irot. In particular, for the torque, after referring the rotor quantities to the stator, we get the well-known expression of general use:

Certainly, (29) is not as visual and didactic as (27) . Yet, on the other hand, it has two key advantages:

- (a)

In line with Feynman´s ideas, the space phasors

Ψ that appear in (29) are, by far, the most important ones, especially for control studies. In fact, virtually all schemes for very high precision torque control are based on them [

24].

- (b)

Ψstr can be easily obtained on-line by measuring the stator voltages and currents. Indeed, from the general equation (22) it follows:

Once the phasorial equations of the fictitious machines have been solved, the current in any stator (or rotor) phase of the real multiphase machine is obtained by adding the projections of the stator (or rotor)

I phasors of all fictitious machines onto their corresponding axes. Since these

I phasors (as well as the torques of the fictitious or of their equivalent three-phase machines) are decoupled, each of them can be controlled in an independent manner. This enables developing schemes for the control of the multiphase machines as a mere extension of those already known for three-phase machines, like the field-oriented or the direct torque control, which are particular cases of a much more general principle [

24].

As to this point, practical implementations of multiphase machines with symmetrical windings that use the field harmonics in addition to the fundamental wave for improving the torque production capability have been known for a very long time, with

m odd being always the case ([

13], page 494). The structure of the machine control is usually deduced and explained by means of rather complex and abstract matrix transformations. This is, of course, a fully legitimate method. Yet, the authors believe that perhaps today’s exacerbate mathematical formalism may sometimes become a process in which the deep physical insight into the phenomena is often almost completely lost. Thus, as an alternative procedure, in pages 90-91 of [

15], a typical field-oriented control structure of the multiphase IM is deduced and explained starting directly from the general principle in [

24] and without resorting to any phase transformation or reduction matrices. It is shown that the usual mathematical blocks of the control structure (whose presence is generally justified and interpreted as abstract matrix transformations) are actually operations with amplitudes, positions, space coordinate changes and projections (to get the time quantities) of the suitable space phasors.