Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

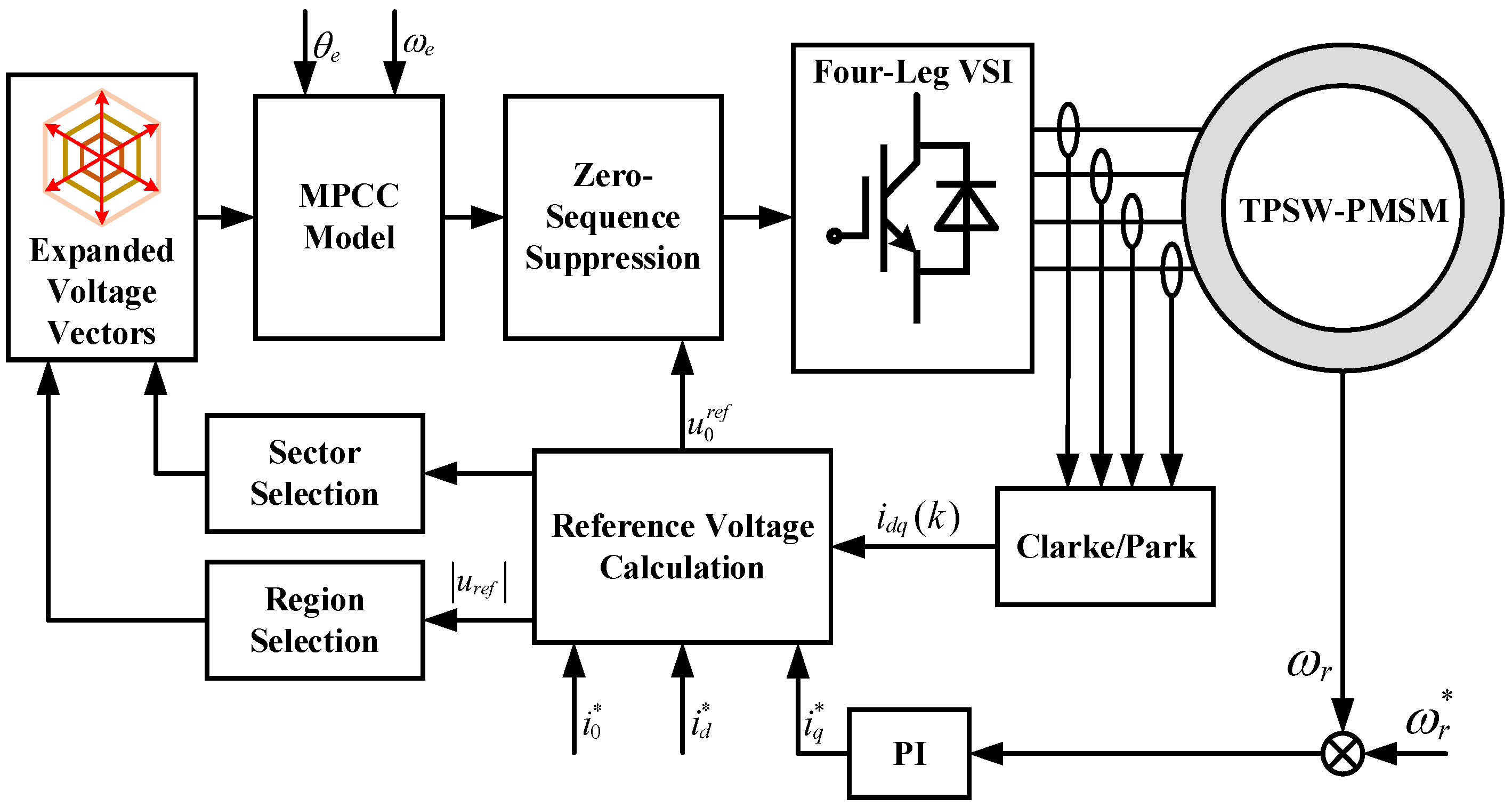

A low-complexity model predictive current control (MPCC) strategy based on extended voltage vectors is proposed to improve computational efficiency and steady-state performance for three-phase series-winding permanent magnet synchronous motors (TPSW-PMSM). This method delivers excellent steady-state performance while substantially reducing the computational burden compared to conventional MPCC. First, a simplified sector selection method is employed to preselect the sector in which the reference voltage vector resides. Next, the reference voltage vector is used to filter out redundant candidate voltage vectors, thereby reducing computation and ensuring real-time control capabilities. Basic active voltage vectors are segmented and recombined according to their magnitudes, without complex duty cycle calculations to further streamline processing. To mitigate the impact of zero-sequence current, zero-sequence current suppression is employed for effective compensation within the control system. This strategy’s combination of reduced computational complexity, reliable steady-state performance, and real-time control establishes it as an efficient solution for TPSW-PMSM systems. Simulation results validate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

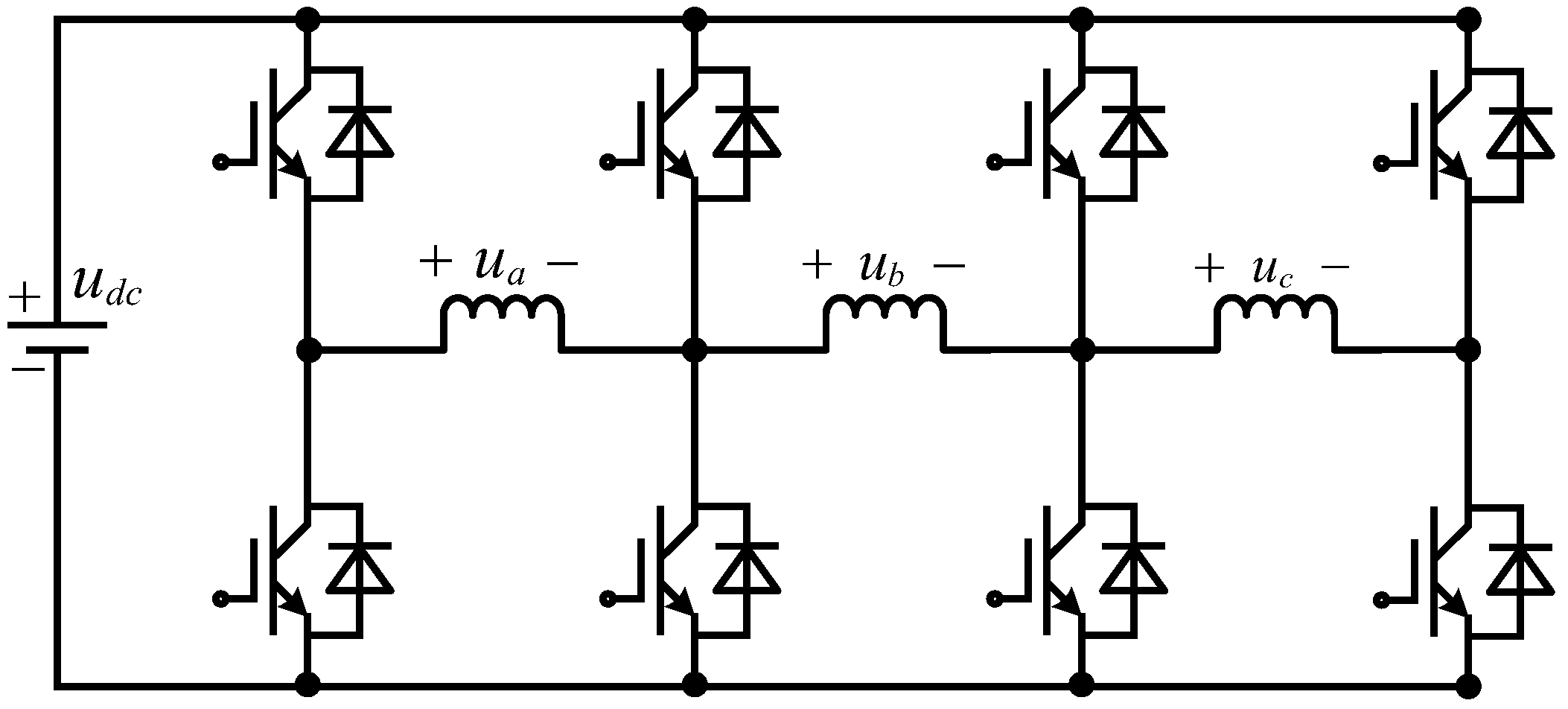

2. Modeling of TPSW-PMSM Drive

2.1. Mathematical Model of the TPSW-PMSM

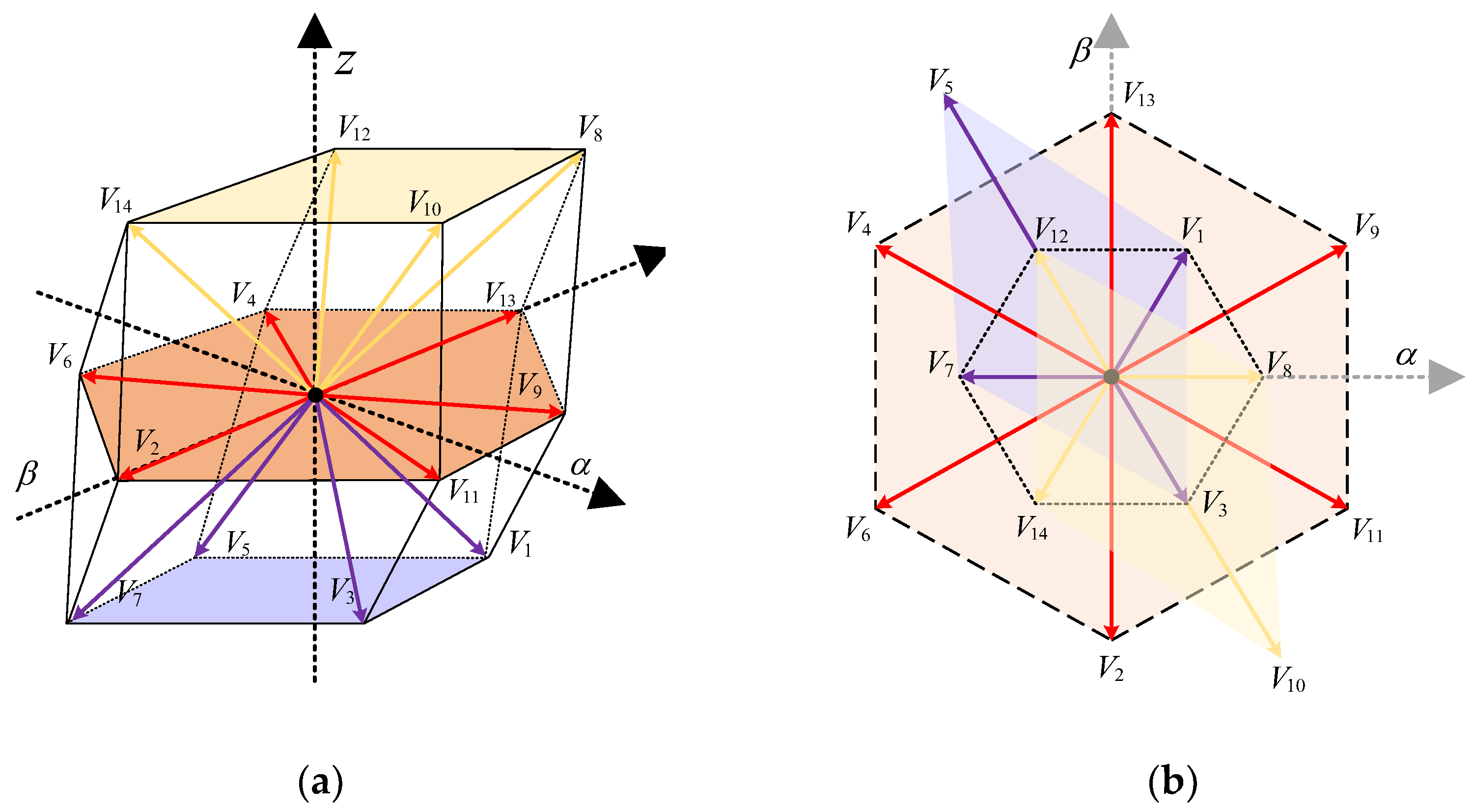

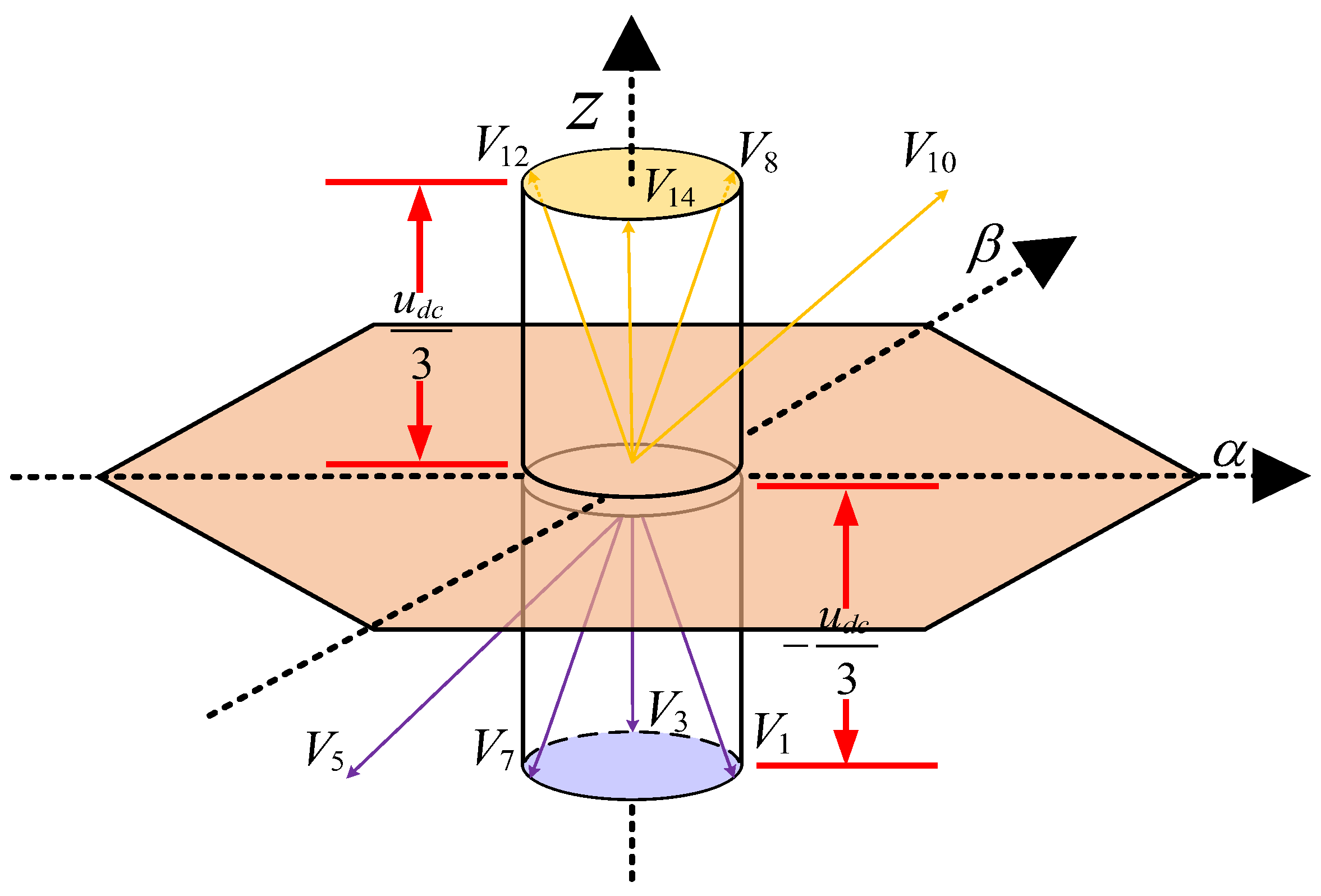

2.2. Voltage Vector Distribution Within the Subspace

3. Improved MPCC for TPSW-PMSM

3.1. Basic Principles of MPCC

3.2. Basic Principles of Proposed MPCC

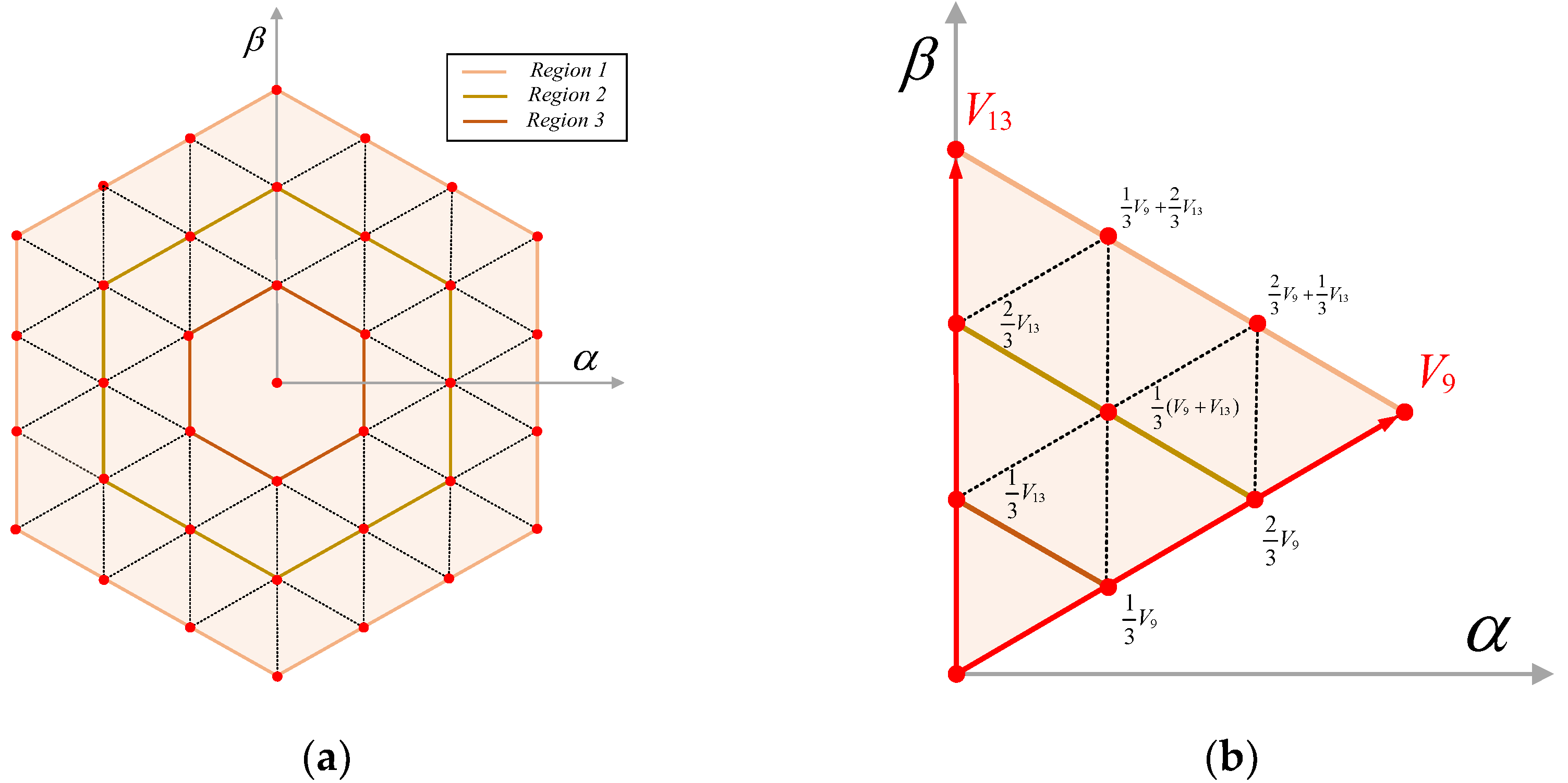

3.2.1. Expanded Voltage Vectors

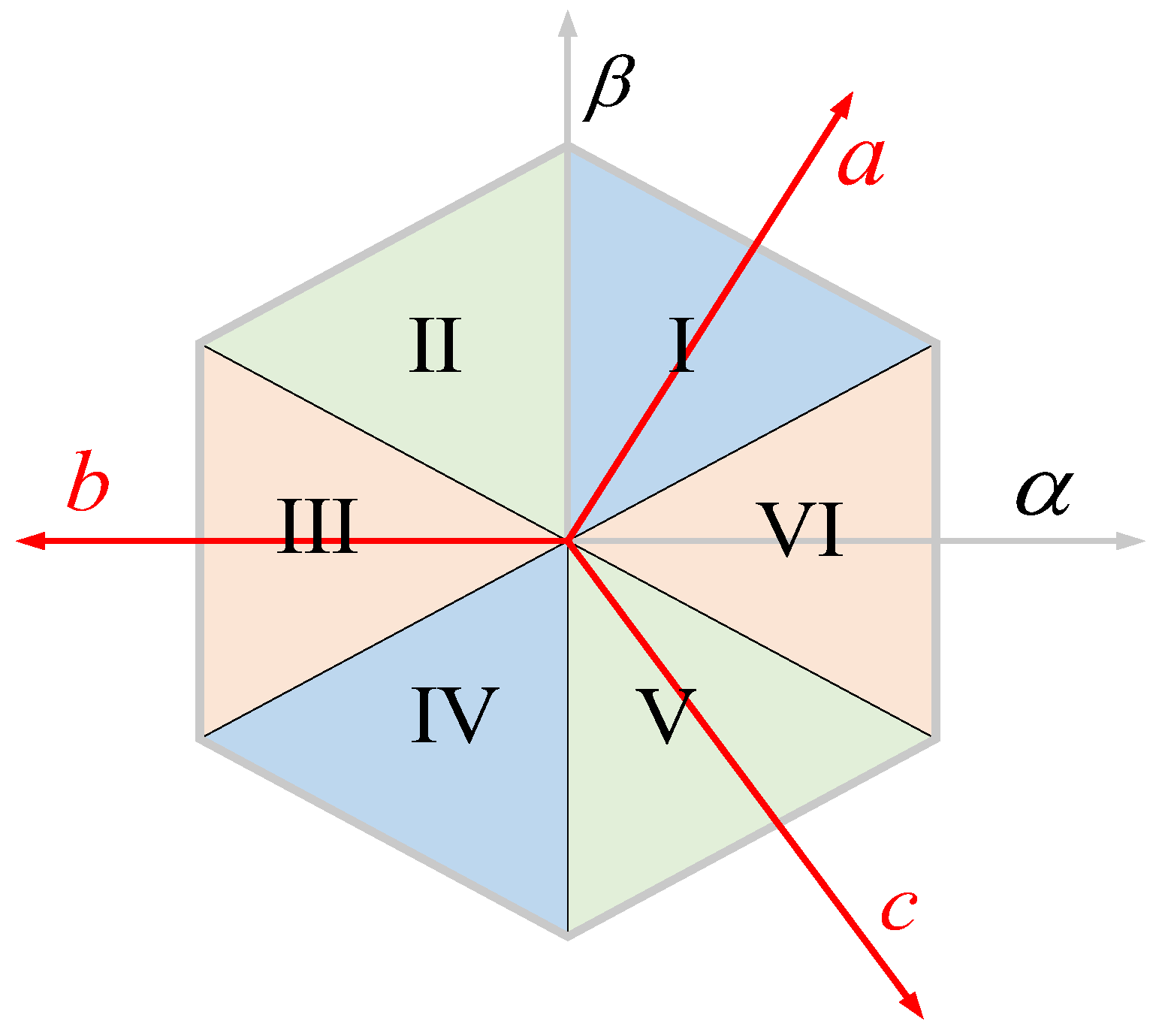

3.2.2. Simplified Voltage Vector Selection

4. Zero-Sequence Current Suppression Strategy

5. Simulation Validation

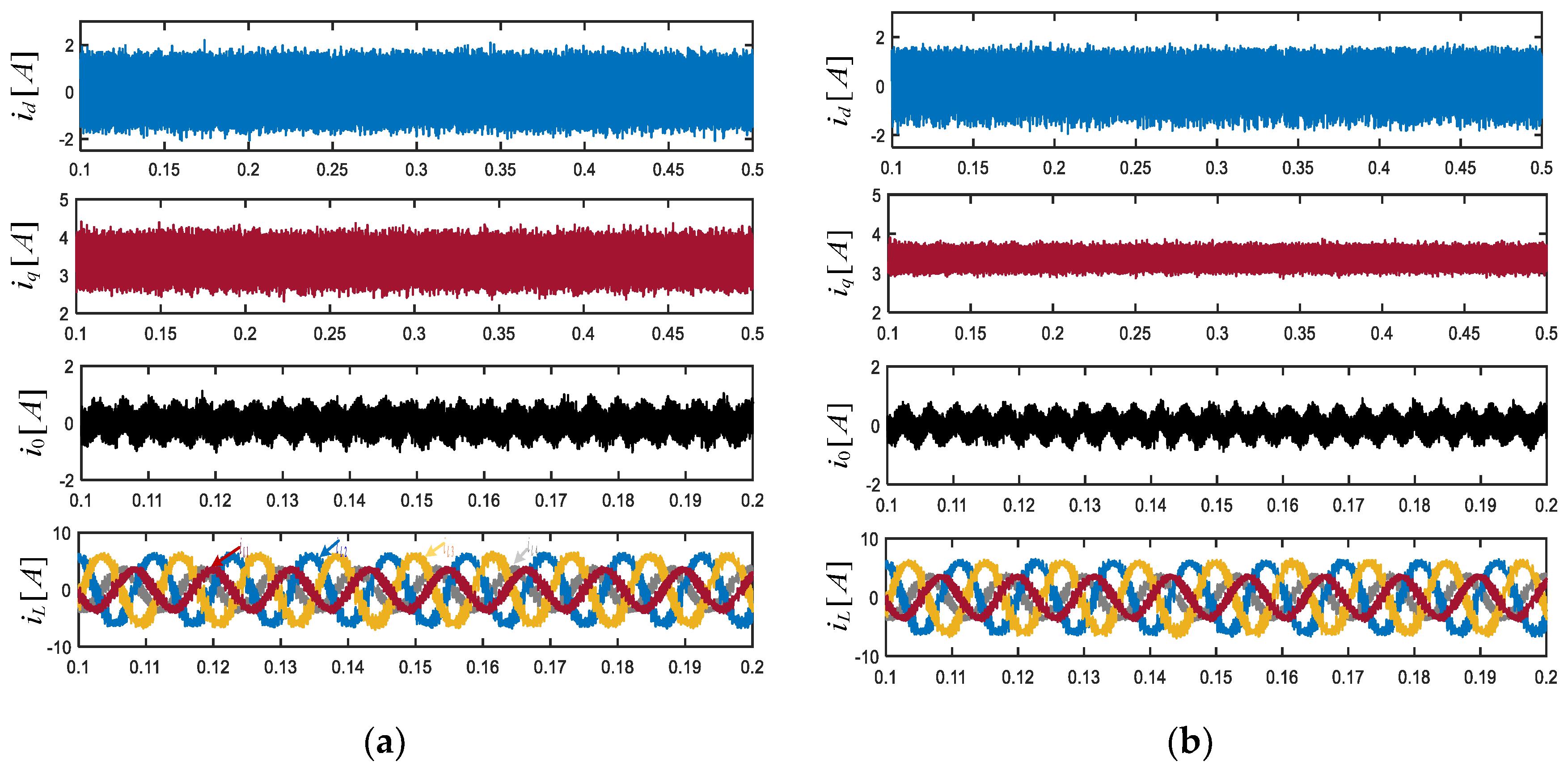

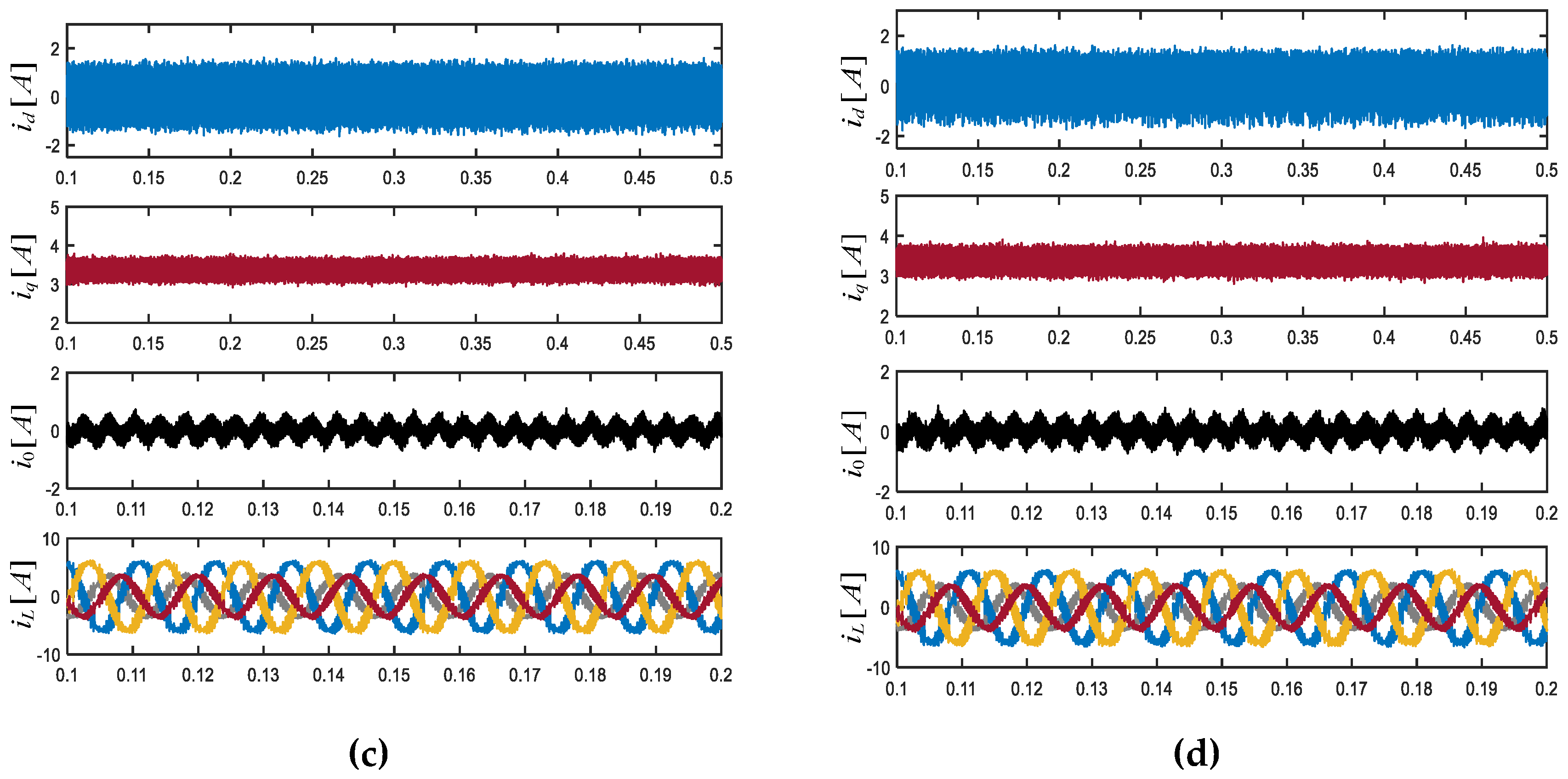

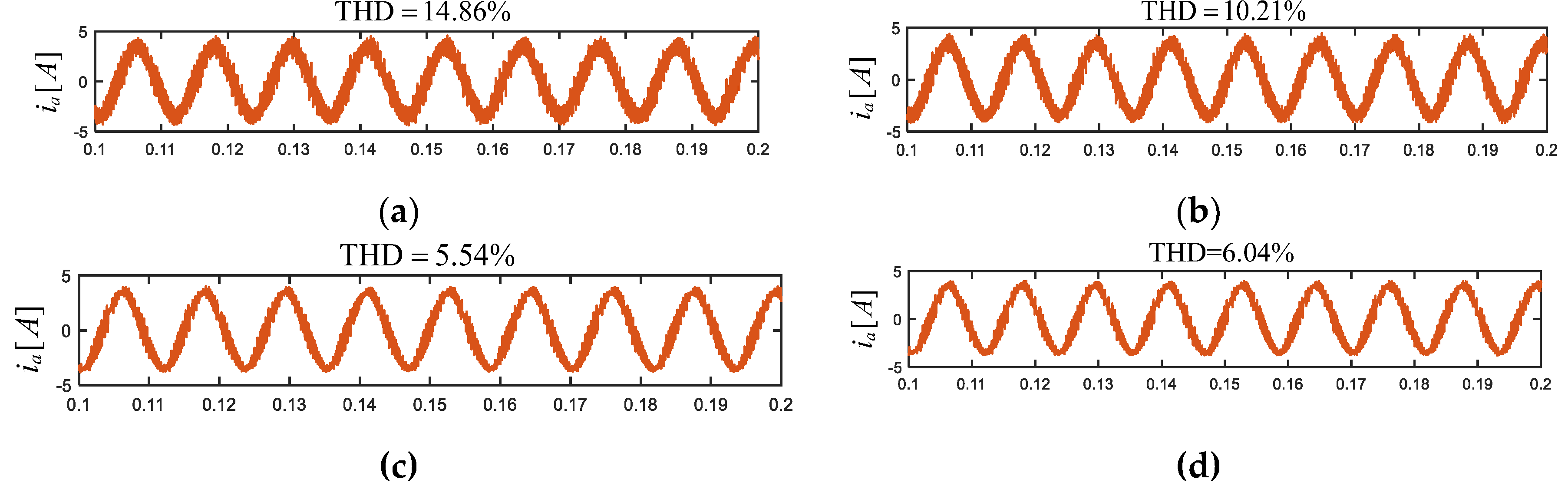

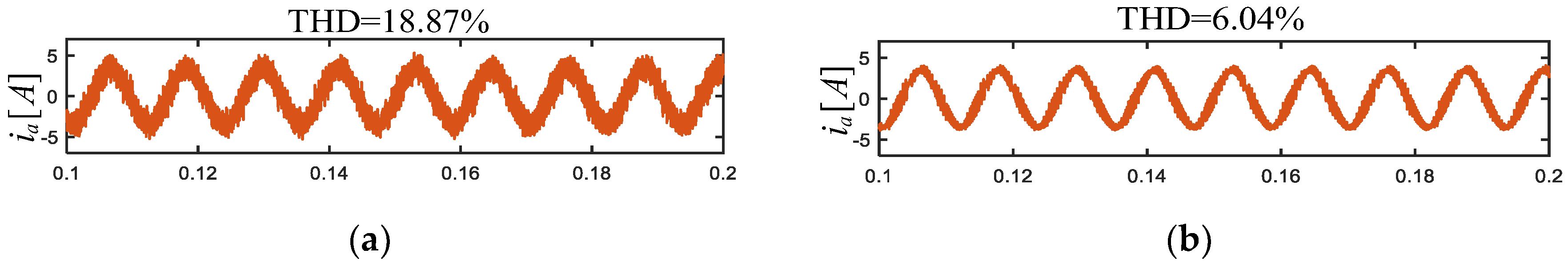

5.1. Steady-State Performance and Computational Complexity Evaluation

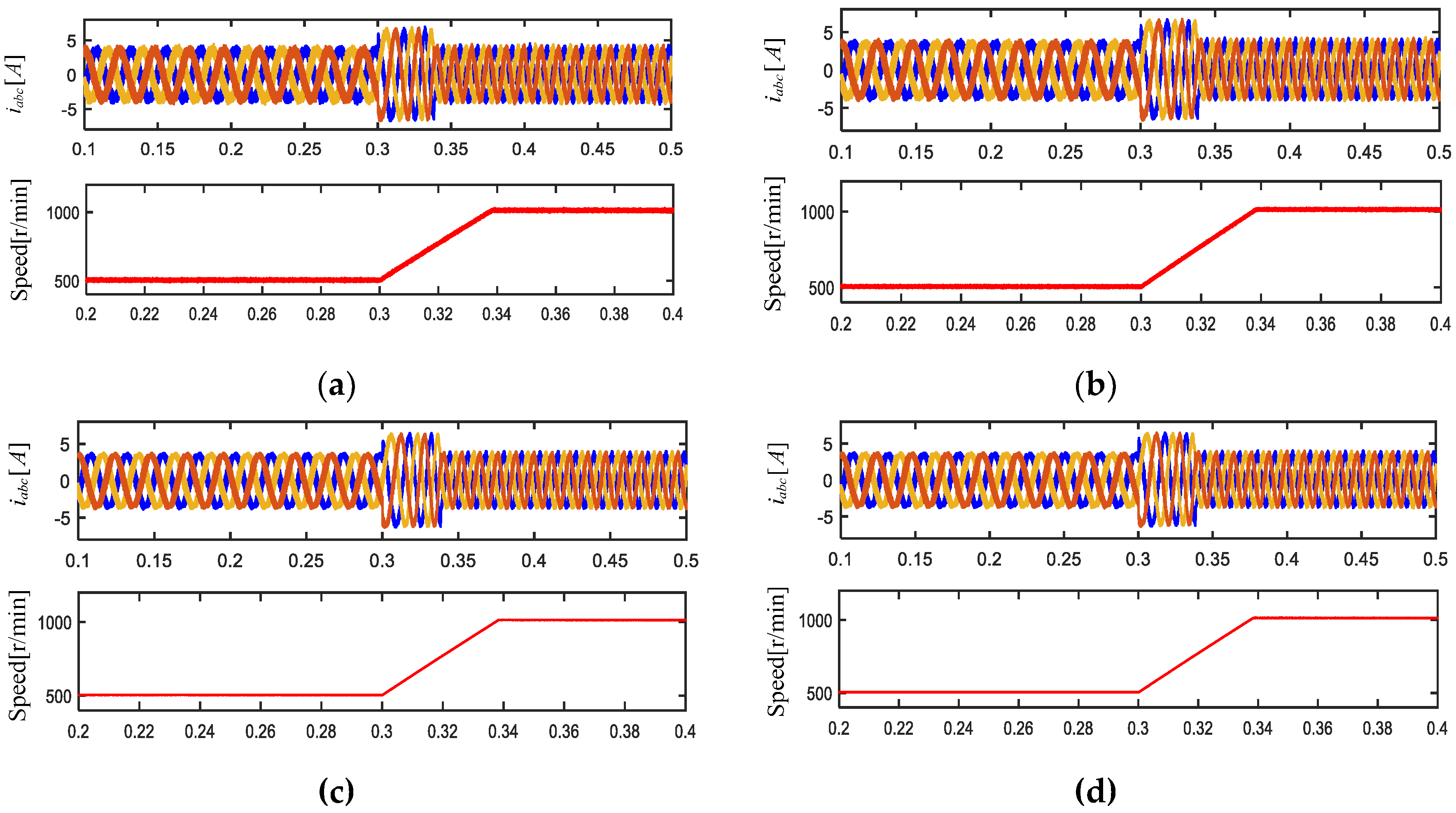

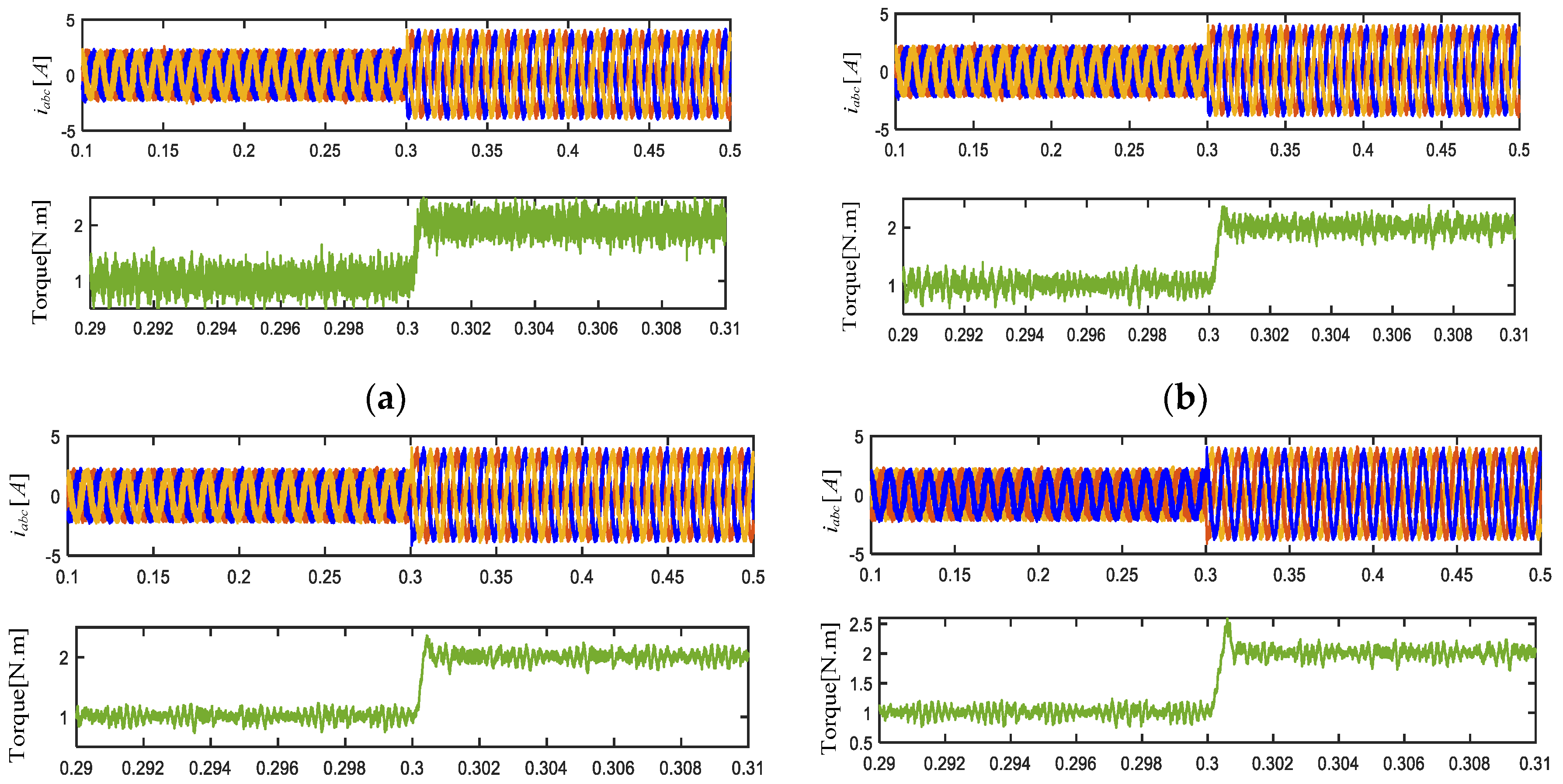

5.2. Dynamic Performance Evaluation

6. Conclusions

Funding

References

- C. Liu, “Emerging Electric Machines and Drives — An Overview,” in IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 2270-2280, Dec. 2018.

- Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Peng, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, X. Torsional Vibration Analysis and Suppression of Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor With Staggered Segmented Rotor for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification 2023, 10, 6285–6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemma, B.D.; Pradabane, S. An Optimized Alternative Fixed Switching 12-Sector Space Vector Pulse Width Modulation Control of Open-End Winding PMSM Drive. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 55169–55177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Huang, Q.; Xie, W. An Improved Parallel Predictive Torque Control for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 32496–32507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Qi, W.; He, T. Direct Torque Control of PMSM with Modified Finite Set Model Predictive Control. Energies 2020, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, A.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, D.; Qu, R. Self-Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control of Three-Phase Series-End Winding Motor Drive. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 10939–10950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhu, X.; Si, X.; Lee, C.H.T. Fault-Tolerant Control for Multiple Open-Leg Faults in Open-End Winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor System Based on Winding Reconnection. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 36, 6068–6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, B.; Xu, C. Research of Fault-Tolerant Control Strategy for Open-End Winding PMSM Under Open-Phase Fault. 2023 IEEE PELS Students and Young Professionals Symposium (SYPS). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ChinaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–5.

- Oto, Y.; Noguchi, T.; Fauziah, M.B. Experimental Verification of Fault Tolerant Operation Focusing on DC-Bus Battery Failure in Dual Inverter Motor Drive. World Electr. Veh. J. 2019, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Jiang, D.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X. Generalized PWM Method for Series-End Winding Motor Drive. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 36, 4452–4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Liu, C.; Song, Z.; Liu, S. Suppression of Dual-Harmonic Components for Five-Phase Series-Winding PMSM. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification 2021, 8, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Ruan, C.; Nian, H.; Sun, D. Zero-Sequence Current Suppression Strategy With Common-Mode Voltage Control for Open-End Winding PMSM Drives With Common DC Bus. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 4691–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Dong, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Liu, C. A Novel Modulation Strategy for Asymmetrical Six-Phase Series-Winding PMSM Based on Predictive Controller. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 70, 5592–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kondo, T.; Rajashekara, K.; Zhu, B. Zero-sequence current suppression for open-end winding induction motor drive with resonant controller. 2016 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, USADATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 2788–2793.

- Cui, R.; Fan, Y.; Cheng, M. A New Zero-Sequence Current Suppression Control Strategy for Five-Phase Open-Winding Fault-Tolerant Fractional-Slot Concentrated Winding IPM Motor Driving System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 2731–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, T.; Mo, L. Zero-Sequence Current Suppression for Open-Winding Permanent Magnet Brushless Motor Driving System Based on Second Order Generalized Integrator. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 37465–37473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Zuo, Y.; Lin, X. Direct Torque Control for Series-Winding PMSM with Zero-Sequence Current Suppression Capability. Electronics 2023, 12, 4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Feng, K.; Liu, C. Multivector-Based Model Predictive Current Control With Zero-Sequence Current Suppression for Three-Phase Series-End Winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification 2022, 9, 3282–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Garcia, C.; Mora, A.; Flores-Bahamonde, F.; Acuna, P.; Novak, M.; Zhang, Y.; Tarisciotti, L.; Davari, S.A.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Latest Advances of Model Predictive Control in Electrical Drives—Part I: Basic Concepts and Advanced Strategies. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 37, 3927–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, K. , Serkies, P., & Szabat, K. (2019). Continuous and Finite Set Model Predictive Control of Induction Motor Drive. IECON 2019 - 45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, 1, 963-968.

- Ahmed, A.A.; Koh, B.K.; Lee, Y.I. A Comparison of Finite Control Set and Continuous Control Set Model Predictive Control Schemes for Speed Control of Induction Motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2017, 14, 1334–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. , & Wu, H. ( 2021). Summary of Model Predictive Control Methods in Motor Drive System. 2021 IEEE 7th International Conference on Control Science and Systems Engineering (ICCSSE), 169–174.

- Zhao, K.; Zhou, R.; She, J.; Zhang, C.; He, J.; Li, X. A Model Predictive Current Control Based on Sliding Mode Speed Controller for PMSM. 2020 13th International Conference on Human System Interaction (HSI). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, JapanDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 229–233.

- Sun, X.; Wu, M.; Lei, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J. An Improved Model Predictive Current Control for PMSM Drives Based on Current Track Circle. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 3782–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.D.; Ramesh, T.; Pothuraju, R. Model Predictive Current Control for Multi-Level Inverter fed Speed Sensorless PMSM Drive. 2022 IEEE IAS Global Conference on Emerging Technologies (GlobConET). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, RomaniaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 375–380.

- Dang, C. , Dou, M., & Wang, Y. (2021). Model predictive direct torque control for PMSM drives in M-T frame. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Predictive Control of Electrical Drives and Power Electronics (PRECEDE), 138-141.

- Ma, C. , Yao, X., Li, H., & De Belie, F. (2019). Current boundary-based model predictive torque control of PMSM. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics, 9(3), 4395-4406.

- Mao, H.; Tang, X.; Tang, H. Speed control of PMSM based on neural network model predictive control. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 2022, 44, 2781–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.A.; Kassem, A.M. Modeling, Simulation and Performance Improvements of a PMSM Based on Functional Model Predictive Control. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2012, 38, 3071–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Yang, H. A Universal Multiple-Vector-Based Model Predictive Control of Induction Motor Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 6957–6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yang, H. Model Predictive Control of PMSM Drives Based on General Discrete Space Vector Modulation. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2020, 36, 1300–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, D.; Huang, L. Generalized Multiple-Vector-Based Model Predictive Control for PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 9356–9366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Voltage Vectors | Switching States | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0001 | /3 | / | -/3 | |

| 0010 | 0 | -2/ | 0 | |

| 0011 | /3 | -/ | -/3 | |

| 0100 | - | / | 0 | |

| 0101 | -2/3 | 2/ | -/3 | |

| 0110 | - | -/ | 0 | |

| 0111 | -2/3 | 0 | -/3 | |

| 1000 | 2/3 | 0 | /3 | |

| 1001 | / | 0 | ||

| 1010 | 2/3 | -2/ | /3 | |

| 1011 | -/ | 0 | ||

| 1100 | -/3 | / | /3 | |

| 1101 | 0 | 2/ | 0 | |

| 1110 | -/3 | -/ | /3 | |

| 1111 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sector | Logical Values |

|---|---|

| I | |

| II | |

| III | |

| IV | |

| V | |

| VI |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Stator Resistance | 0.9 |

| Pole Pairs | 4 |

| d-axis Inductance | 3.7 |

| q-axis Inductance | 5 |

| Zero-sequence Inductance | 4 |

| Flux Linkage | 0.08 |

| Third Rotor Flux Linkage | 0.002 |

| Control scheme | Number of candidate voltage vectors | Computational burden of sector selection | Time allocation calculations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional-MPCC | 16 | Low | No |

| DCC-MPCC (no sector selection) |

6 | Low | Yes |

| DCC-MPCC (sector selection) |

1 | High | Yes |

| DV-MPCC (no sector selection) |

Low | Yes | |

| DV-MPCC (sector selection) |

1 | High | Yes |

| Proposed MPCC | Low | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).