Submitted:

01 December 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

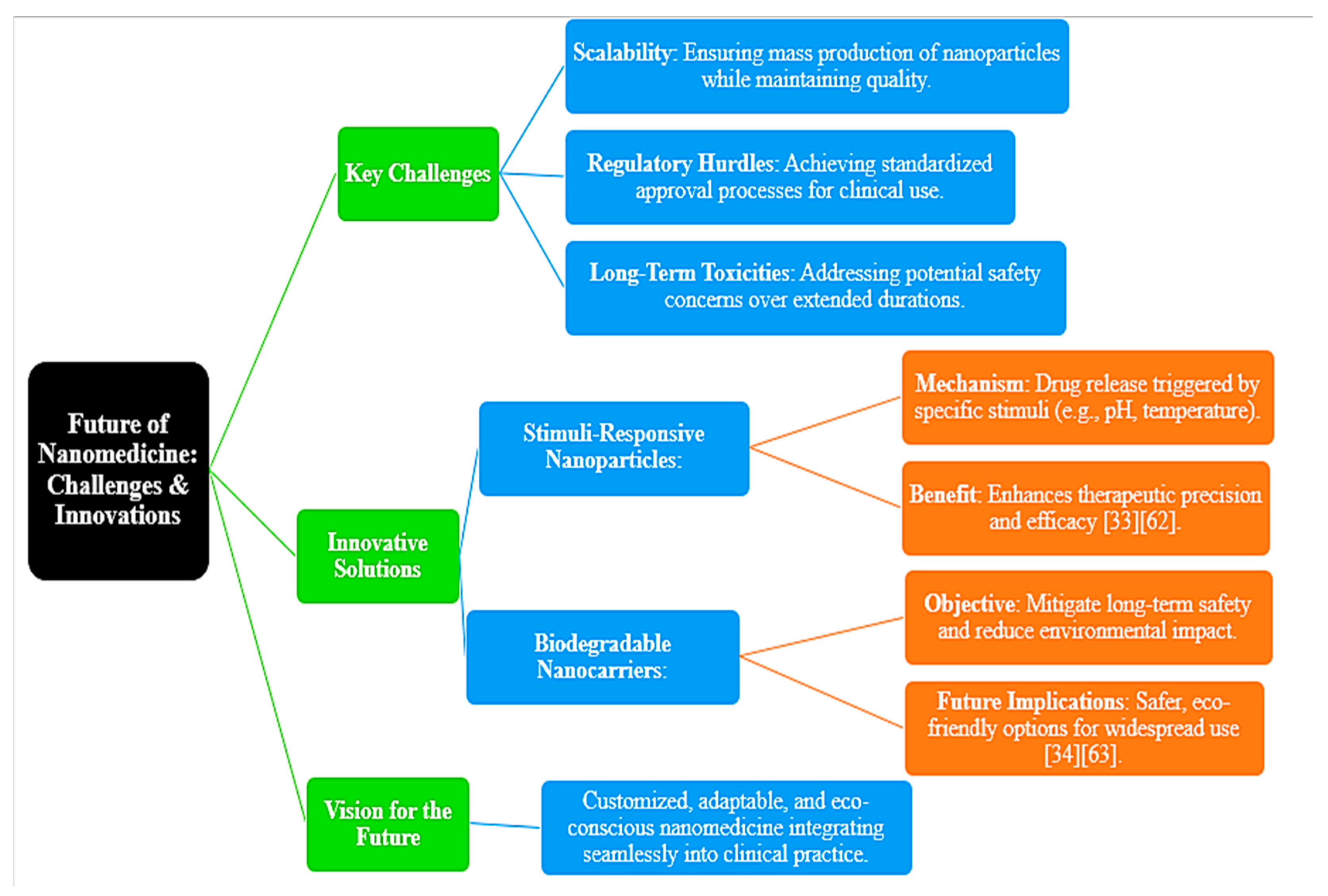

Customization of medicine has made healthcare even more personalized, enhancing therapeutical efficiency with low adverse effects. It can be achieved through an innovative tool that has reached unprecedented abilities through the process of nanotechnology in targeted drug delivery, advanced diagnostics, and therapeutic systems. This makes a review on the integration of nanotechnology with personalized medicine-including historical considerations towards applications in today's contexts up to future perspectives.The targeting of diseased tissues has proven to be tremendous, considering a combination of both passive and active targeting mechanisms that nanospheres assume the form of liposomes, dendrimers, or polymeric micelles. Quantum dots and nanosensors have revolutionized the area of diagnostics, enabling detection at an earliest possible stage with real-time monitoring, changing patient care forever. Theranostic platforms, integrating therapeutic agents with diagnostic tools, really reveal the dynamic ability to customize treatments.Despite these strides forward, the critical problems to be overcome are those related to biological complexity, barriers caused by regulation, and eventual long-term toxicities. Biocompatible biodegradable nanocarrier research and responsive system explorations will help move such applications forward in a positive fashion toward better and safer designs. The joining of wearable nanotechnology to a nanoparticle-enabled gene delivery system is probably going to move standards of care.This review outlines the crucial role nanotechnology is playing in moving personalized medicine forward, from bridging diagnosis to therapy and filling the gap of heterogeneity in disease. But a lot more is to come because it holds promise for a revolution in healthcare ever more precise, adaptable, and patient-centered with innovation and interdisciplinary collaboration continuing.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Personalized Medicine and Nanotechnology

2.1. Evolution, Challenges, and Applications of Nanotechnology in Precision Care

| Aspect | Description | Examples/Remarks | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolution of Personalized Medicine | Driven by advances in genomics and proteomics, focusing on patient-specific molecular pathways for precise interventions. | Nanotechnology contributes significantly through precise drug delivery and theranostics. | [11,12] |

| Drug Delivery Systems | Nanoparticles like liposomes, dendrimers, and polymeric micelles enable targeted drug delivery, enhancing drug bioavailability and specificity. | E.g., Doxil minimizes cardiotoxicity in cancer treatment. | [7], [13,14,15] |

| EPR Effect | Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect localizes drugs at tumor sites, improving therapeutic efficacy and reducing systemic toxicity. | Widely utilized in cancer nanomedicine. | [13,14] |

| Diagnostics | Quantum dots and magnetic nanoparticles improve imaging resolution and enable real-time monitoring of disease progression. | Facilitates dynamic assessment of disease states. | [18,19] |

| Theranostics | Combines therapeutic and diagnostic functions, providing real-time feedback on treatment efficacy and enabling adaptive strategies. | A pivotal innovation in precision care. | [20] |

| Challenges in Nanomedicine | Includes disease heterogeneity, biocompatibility, long-term toxicity concerns, and regulatory hurdles. | Requires interdisciplinary collaborations for effective solutions. | [16,17] |

3. Targeted Drug Delivery with Nanotechnology

3.1. Key Systems and Strategies in Nanoparticle-Mediated Therapies

| Feature | Description | Examples/Remarks | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Liposomes, one of the earliest and widely utilized nanocarriers. | Recognized for their versatility in drug delivery. | [3,26] |

| Key Characteristics | Biocompatible and capable of encapsulating both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs. | Supports broad-spectrum drug delivery applications. | [3] |

| Surface Modifications | Incorporation of PEGylation enhances stability and prolongs circulation time in the bloodstream. | Improves pharmacokinetic profile and targeting efficiency. | [26,27] |

| Clinical Example | Doxil, a liposomal formulation of doxorubicin, reduces cardiotoxicity and targets tumors. | A notable success in clinical oncology applications. | [26,27] |

| Recent Advancements | Innovations in liposomal systems emphasize their role in targeted drug delivery. | Highlighted as a key approach in modern therapeutic research. | [1,28] |

| Feature | Details | References |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle-Aptamer Conjugates | Strategy for achieving cell-specific drug delivery in oncology, offering precise targeting for cancer therapies. | [58] |

| Dendrimers | Highly branched, tree-like structures with high drug-loading capacity, ideal for delivering anticancer agents. | [29,30] |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles | Engineered nanoparticles that respond to specific stimuli (e.g., pH or temperature) for controlled, localized drug release in diseased tissues. | [2,31] |

| Vesicular Nano-Carriers (Liposomal Systems) | Nano-carriers expanding in precision care, particularly in the management of respiratory health. | [2,31] |

4. Diagnostic and Theranostic Applications

4.1. Nanotechnology’s Role in Diagnostics and Combined Therapeutic Approaches

| Feature | Description | Examples/Remarks | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theranostics | Convergence of therapeutic and diagnostic functions, enhancing precision medicine. Enables real-time monitoring and adaptive treatment. | Combines diagnostics and therapy for advanced medical approaches. | [40,41] |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Nanoparticles with unique optical properties like brightness and photostability, used in imaging and biomarker detection. | Ideal for high-resolution cellular imaging and target tracking. | [42,43] |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Enhance contrast in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and enable targeted drug delivery. | Used for improving MRI imaging and targeted therapies. | [44] |

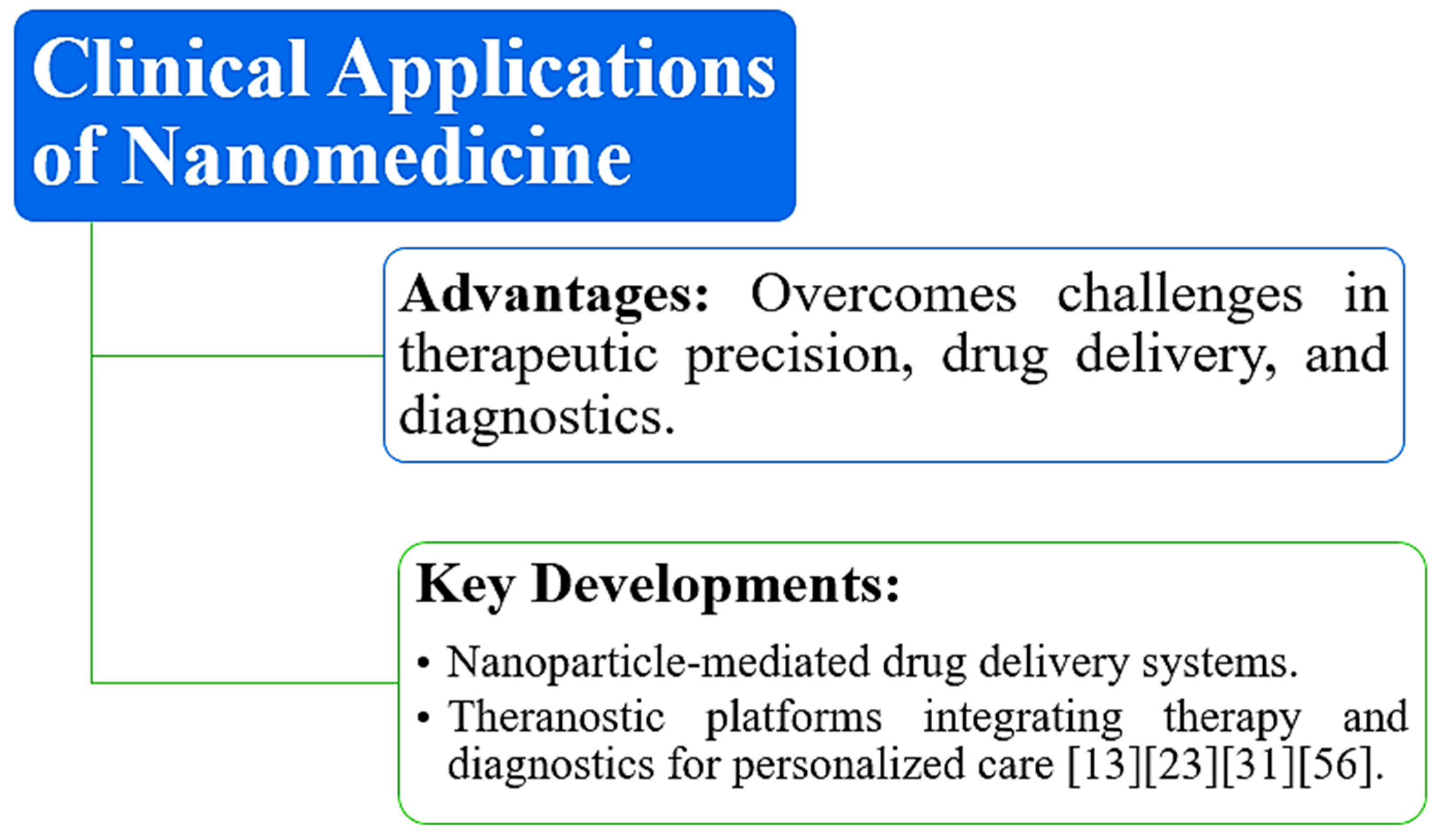

5. Clinical Applications and Future Directions

5.1. Real-World Applications and Future Prospects for Nanomedicine in Personalized Care

6. Conclusions

References

- Maeda, H., Wu, J., Sawa, T., Matsumura, Y., & Hori, K. (2000). Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: A review. Journal of Controlled Release, 65(1-2), 271–284. [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. E., Chen, Z., & Shin, D. M. (2008). Nanoparticle therapeutics: An emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 7(9), 771–782. [CrossRef]

- Torchilin, V. P. (2005). Recent advances with liposomes as pharmaceutical carriers. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 4(2), 145–160. [CrossRef]

- Jain, R. K., & Stylianopoulos, T. (2010). Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 7(11), 653–664. [CrossRef]

- Peer, D., Karp, J. M., Hong, S., Farokhzad, O. C., Margalit, R., & Langer, R. (2007). Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nature Nanotechnology, 2(12), 751–760. [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Y., & Maeda, H. (1986). A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: Mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Research, 46(12), 6387–6392.

- Wang, A. Z., Langer, R., & Farokhzad, O. C. (2012). Nanoparticle delivery of cancer drugs. Annual Review of Medicine, 63, 185–198. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S., & Benjamin, L. E. (2007). Nanotechnology for cancer therapy: Hype or hope? Nature Medicine, 13(8), 929–935. [CrossRef]

- Alexis, F., Pridgen, E., Molnar, L. K., & Farokhzad, O. C. (2008). Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. Molecular Pharmaceutics, 5(4), 505–515. [CrossRef]

- Sun, T. M., Zhang, Y. S., Pang, B., Hyun, D. C., Yang, M., & Xia, Y. (2014). Engineered nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer therapy. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 53(46), 12320–12364. [CrossRef]

- Sykes, E. A., et al. (2014). Tailoring nanoparticles for personalized cancer therapies. Nature Nanotechnology, 9(10), 821–823. [CrossRef]

- Sun, T. M., Zhang, Y. S., Pang, B., Hyun, D. C., Yang, M., & Xia, Y. (2014). Engineered nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer therapy. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 53(46), 12320–12364. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M. (2005). Cancer nanotechnology: Opportunities and challenges. Nature Reviews Cancer, 5(3), 161–171. [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, N., Wu, J., Xu, X., Kamaly, N., & Farokhzad, O. C. (2014). Cancer nanotechnology: The impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 66, 2–25. [CrossRef]

- Torchilin, V. P. (2006). Multifunctional nanocarriers. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 58(14), 1532–1555. [CrossRef]

- Farokhzad, O. C., Cheng, J., Teply, B. A., Sherifi, I., Jon, S., Kantoff, P. W., Richie, J. P., & Langer, R. (2006). Targeted nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates for cancer chemotherapy in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(16), 6315–6320. [CrossRef]

- Jain, R. K. (2001). Delivery of molecular and cellular medicine to solid tumors. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 46(1-3), 149–168. [CrossRef]

- Nie, S., Xing, Y., Kim, G. J., & Simons, J. W. (2007). Nanotechnology applications in cancer. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering, 9, 257–288. [CrossRef]

- Park, K., & Kang, E. (2010). Safe and efficient nanocarriers: Commentaries on clinical success and remaining issues in nanomedicine. Nano Today, 5(5), 325–330. [CrossRef]

- Kamaly, N., Xiao, Z., Valencia, P. M., Radovic-Moreno, A. F., & Farokhzad, O. C. (2012). Targeted polymeric therapeutic nanoparticles: Design, development, and clinical translation. Chemical Society Reviews, 41(7), 2971–3010. [CrossRef]

- Gradishar, W. J., Tjulandin, S., Davidson, N., Shaw, H., Desai, N., Bhar, P., & Hawkins, M. J. (2005). Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(31), 7794–7803. [CrossRef]

- Petros, R. A., & DeSimone, J. M. (2010). Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 9(8), 615–627. [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, R. N., Jagrati, K., Sengar, A., & Prajapati, S. K. (2024). Nanoparticles: Pioneering the future of drug delivery and beyond. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 13(13), 1243–1262.

- Sengar, A., Jagrati, K., & Khatri, S. (2024). Enhancing therapeutics: A comprehensive review on naso-pulmonary drug delivery systems for respiratory health management. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 13(13), 1112–1140.

- Sengar, A. (2023). Targeting methods: A short review including rationale, goal, causes, strategies for targeting. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, 4(8), 1379–1384. ISSN 2582-7421.

- Jagrati, K. M., & Sengar, A. (2024). Liposomal vesicular delivery system: An innovative nano carrier. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 13(13), 1155–1169. [CrossRef]

- Sengar, A., Vashisth, H., Chatekar, V. K., Gupta, B., Thange, A. R., & Jillella, M. S. R. S. N. (2024). From concept to consumption: A comprehensive review of chewable tablets. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 13(16), 176–189.

- Sengar, A., Tile, S. A., Sen, A., Malunjkar, S. P., Bhagat, D. T., & Thete, A. K. (2024). Effervescent tablets explored: Dosage form benefits, formulation strategies, and methodological insights. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 13(18), 1424–1435.

- Sengar, A., Saha, S., Sharma, L., Hemlata, Saindane, P. S., & Sagar, S. D. (2024). Fundamentals of proniosomes: Structure & composition, and core principles. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 13(21), 1063–1071.

- Jain, R. K., & Stylianopoulos, T. (2010). Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 7(11), 653–664. [CrossRef]

- Nie, S., Xing, Y., Kim, G. J., & Simons, J. W. (2007). Nanotechnology applications in cancer. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering, 9, 257–288. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M. (2005). Cancer nanotechnology: Opportunities and challenges. Nature Reviews Cancer, 5(3), 161–171. [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, N., Wu, J., Xu, X., Kamaly, N., & Farokhzad, O. C. (2014). Cancer nanotechnology: The impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 66, 2–25. [CrossRef]

- Torchilin, V. P. (2006). Multifunctional nanocarriers. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 58(14), 1532–1555. [CrossRef]

- Farokhzad, O. C., Cheng, J., Teply, B. A., Sherifi, I., Jon, S., Kantoff, P. W., Richie, J. P., & Langer, R. (2006). Targeted nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates for cancer chemotherapy in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(16), 6315–6320. [CrossRef]

- Park, K., & Kang, E. (2010). Safe and efficient nanocarriers: Commentaries on clinical success and remaining issues in nanomedicine. Nano Today, 5(5), 325–330. [CrossRef]

- Kamaly, N., Xiao, Z., Valencia, P. M., Radovic-Moreno, A. F., & Farokhzad, O. C. (2012). Targeted polymeric therapeutic nanoparticles: Design, development, and clinical translation. Chemical Society Reviews, 41(7), 2971–3010. [CrossRef]

- Gradishar, W. J., Tjulandin, S., Davidson, N., Shaw, H., Desai, N., Bhar, P., & Hawkins, M. J. (2005). Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(31), 7794–7803. [CrossRef]

- Petros, R. A., & DeSimone, J. M. (2010). Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 9(8), 615–627. [CrossRef]

- O’Neal, D. P., Hirsch, L. R., Halas, N. J., Payne, J. D., & West, J. L. (2004). Photo-thermal tumor ablation in mice using near-infrared-absorbing nanoparticles. Cancer Letters, 209(2), 171–176. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X., Cui, Y., Levenson, R. M., Chung, L. W., & Nie, S. (2004). In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. Nature Biotechnology, 22(8), 969–976. [CrossRef]

- Nie, S., Xing, Y., Kim, G. J., & Simons, J. W. (2007). Nanotechnology applications in cancer. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering, 9, 257–288. [CrossRef]

- Park, K., & Kang, E. (2010). Safe and efficient nanocarriers: Commentaries on clinical success and remaining issues in nanomedicine. Nano Today, 5(5), 325–330. [CrossRef]

- Kamaly, N., Xiao, Z., Valencia, P. M., Radovic-Moreno, A. F., & Farokhzad, O. C. (2012). Targeted polymeric therapeutic nanoparticles: Design, development, and clinical translation. Chemical Society Reviews, 41(7), 2971–3010. [CrossRef]

- Gradishar, W. J., Tjulandin, S., Davidson, N., Shaw, H., Desai, N., Bhar, P., & Hawkins, M. J. (2005). Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(31), 7794–7803. [CrossRef]

- Petros, R. A., & DeSimone, J. M. (2010). Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 9(8), 615–627. [CrossRef]

- Jain, R. K. (2001). Delivery of molecular and cellular medicine to solid tumors. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 46(1-3), 149–168. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M. (2005). Cancer nanotechnology: Opportunities and challenges. Nature Reviews Cancer, 5(3), 161–171. [CrossRef]

- Sengar, A., Yadav, S., & Niranjan, S. K. (2024). Formulation and evaluation of mouth-dissolving films of propranolol hydrochloride. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 13(16), 850–861.

- Bertrand, N., Wu, J., Xu, X., Kamaly, N., & Farokhzad, O. C. (2014). Cancer nanotechnology: The impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 66, 2–25. [CrossRef]

- Torchilin, V. P. (2006). Multifunctional nanocarriers. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 58(14), 1532–1555. [CrossRef]

- Farokhzad, O. C., Cheng, J., Teply, B. A., Sherifi, I., Jon, S., Kantoff, P. W., Richie, J. P., & Langer, R. (2006). Targeted nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates for cancer chemotherapy in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(16), 6315–6320. [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, N., & Kataoka, K. (2006). Current state, achievements, and future prospects of polymeric micelles as nanocarriers for drug and gene delivery. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 112(3), 630–648. [CrossRef]

- Jain, R. K., & Stylianopoulos, T. (2010). Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 7(11), 653–664. [CrossRef]

- Nie, S., Xing, Y., Kim, G. J., & Simons, J. W. (2007). Nanotechnology applications in cancer. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering, 9, 257–288. [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, N., Wu, J., Xu, X., Kamaly, N., & Farokhzad, O. C. (2014). Cancer nanotechnology: The impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 66, 2–25. [CrossRef]

- Torchilin, V. P. (2006). Multifunctional nanocarriers. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 58(14), 1532–1555. [CrossRef]

- Farokhzad, O. C., Cheng, J., Teply, B. A., Sherifi, I., Jon, S., Kantoff, P. W., Richie, J. P., & Langer, R. (2006). Targeted nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates for cancer chemotherapy in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(16), 6315–6320. [CrossRef]

- Kamaly, N., Xiao, Z., Valencia, P. M., Radovic-Moreno, A. F., & Farokhzad, O. C. (2012). Targeted polymeric therapeutic nanoparticles: Design, development, and clinical translation. Chemical Society Reviews, 41(7), 2971–3010. [CrossRef]

- Gradishar, W. J., Tjulandin, S., Davidson, N., Shaw, H., Desai, N., Bhar, P., & Hawkins, M. J. (2005). Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(31), 7794–7803. [CrossRef]

- Petros, R. A., & DeSimone, J. M. (2010). Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 9(8), 615–627. [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, N., & Kataoka, K. (2006). Current state, achievements, and future prospects of polymeric micelles as nanocarriers for drug and gene delivery. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 112(3), 630–648. [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, M. A., Fallica, A. N., Virzì, N., Kesharwani, P., Pittalà, V., & Greish, K. (2022). The promise of nanotechnology in personalized medicine. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(5), 673. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).