Submitted:

07 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Soil Sample

2.2. Preparation of Medium for Isolation of Fungal Species

2.3. Preparation of Potato Dextrose Agar for Isolation of Fungal Species

2.4. Preparation of 3, 5-Dinitrosalicylic Acid (DNS)

2.5. Isolation and Sub-Culturing of Fungal Specie

2.6. Identification of Fungal Isolates

2.7. Qualitative (Primary) Screening for Pectinolytic Fungal Species

2.8. Quantitative (Secondary) Screening for Pectinolytic Fungal Species

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation and Sub-Culturing of Fungal Species

3.2. Identification of Fungal Isolates

3.3. Qualitative (Primary) Screening for Pectinolytic Fungal Species

3.4. Quantitative Screening of Potent Pectinolytic Fungal Species (Secondary Screening)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shilpa, M.K.; Jason, Y. Isolation and screening of pectinase-producing bacteria from soil sample. CGC Int. J. Contemp. Res. Eng. Technol. 2021, 3, 166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Belkheiri, A.; Forouhar, A.; Ursu, A.V.; Dubessay, P.; Pierre, G.; Delattre, C.; Djelveh, G.; Abdelkafi, S.; Hamdami, N.; Michaud, P. Extraction, Characterization, and Applications of Pectins from Plant By-Products. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokade, D.D.; Vaidya, S.L.; Naziya, M.A.; Dixit, P.P. Screening of Pectinase Producing Bacteria, Isolated from Osmanabad fruit market soil. Int. J. Interdiscip. Multidiscip. 2015, 2, 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Tabssum, F.; Ali, S.S. Screening of pectinase producing Gram-positive bacteria: Isolation and characterization. Punjab Univ. J. Zool. 2018, 33, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.; Kumar, A.S.; Mukherjee, G. Isolation and Characterization of Alkaline Pectinase Productive Bacillus tropicus from Fruit and Vegetable Waste Dump Soil. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2021, 64, e21200319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakitikul, W.; Tammasat, T.; Udjai, J.; Nimmanpipug, P. Experimental and DFT study of gelling factor of pectin. Suranaree J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 23, 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Carlos Álvarez García, Chapter 11 - Application of Enzymes for Fruit Juice Processing, Editor(s): Gaurav Rajauria, Brijesh K. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.M.P.; Coimbra, J.S.R.; Souza, V.G.L.; Sousa, R.C.S. Structure and Applications of Pectin in Food, Biomedical, and Pharmaceutical Industry: A Review. Coatings 2021, 11, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarini, M.; Durazzo, A. Bernini, R.; Campo, M.; Vita, C.; Souto, E.B.; Lombardi-Boccia, G, Ramadan, M.F.; Santini, A.; Romani, A. Fruit Wastes as a Valuable Source of Value-Added Compounds: A Collaborative Perspective. Molecules 2021, 26, 6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinay, C.; Biswas, D.; Roy, S.; Vaidya, D.; Verma, A.; Gupta, A. Current Advancements in Pectin: Extraction, Properties and Multifunctional Applications. Foods 2022, 11, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Hua, X.; Liu, J.R.; Wang, M.M.; Liu, Y.X.; Yang, R.J.; Cao, Y.P. Extraction of sunflower head pectin with superfine grinding pretreatment. Food Chem. 2020, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picot-Allain, M.C.N.; Ramasawmy, B.; Emmambux, M.N. Extraction, characterisation, and application of pectin from tropical and sub-tropical fruits: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 38, 282–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman-Benn, A.; Contador, C.A.; Li, M.-W.; Lam, H.-M.; Ah-Hen, K.; Ulloa, P.E.; Ravanal, M.C. Pectin: An overview of sources, extraction and applications in food products, biomedical, pharmaceutical and environmental issues. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suckhoequyhonvang.vn (2022). Health benefits of pectin. https://www.suckhoequyhonvang.vn/tin-tuc/nhung-tuc-dung-cua-pectin-doi-voi-suc-khoe-92.html. (Accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Hassan, S. Development of Novel Pectinase and Xylanase Juice Clarifcation Enzymes via a Combined Biorefnery and Immobilization Approach. Doctoral Thesis, Technological University Dublin, Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauldhar, B.S.; Kaur, H.; Meda, V.; Sooch, B.S. Chapter 12—Insights into Upstreaming and Downstreaming Processes of Microbial Extremozymes. Extremozymes and Their Industrial Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 321–352. ISBN 9780323902748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shet, A.R.; Desai, S.V.; Achappa, S. Pectinolytic enzymes: Classification, production, purification and applications. Res. J. Life Sci. Bioinform. Pharm Chem. Sci. 2018, 4, 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Basheer, S.M.; Chellappan, S.; Sabu, A. Chapter 8—Enzymes in Fruit and Vegetable Processing; Kuddus, M., Aguilar, C.N., Eds.; Value-Addition in Food Products and Processing through Enzyme Technology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 101–110. ISBN 9780323899291. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, G.; Singh, A.; Kaur, A.; Singh, R.; Kaur, J.; Mahajan, R. Microbial pectinases: An ecofriendly tool of nature for industries. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumer, O.J.; Abate, D. Screening and molecular identification of pectinase producing microbes from coffee pulp. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2961767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satapathy, S.; Behera, P.M.; Tanty, D.K.; Srivastava, S.; Thatoi, H.; Dixit, A.; Sahoo, S.L. Isolation and molecular identification of pectinase producing Aspergillus species from different soil samples of Bhubaneswar regions. BioRxiv 2019, 2019 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, S.; Chio, C.; Khatiwada, J.R.; Kognou, A.L.M.; Chen, X.; Qin, W. Optimization of Cultural Conditions for Pectinase Production by Streptomyces sp. and Characterization of Partially Purified Enzymes. Microb. Physiol. 2023, 33, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Kokare, C. Chapter 17—Microbial Enzymes of Use in Industry; Brahmachari, G., Ed.; Biotechnology of Microbial Enzymes (Second Edition); Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 405–444. ISBN 9780443190599. [Google Scholar]

- Osete-Alcaraz, A.; Gómez-Plaza, E.; Pérez-Porras, P.; Bautista-Ortín, A.B. Revisiting the use of pectinases in enology: A role beyond facilitating phenolic grape extraction. Food Chem. 2022, 372, 131282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, S.; Ayele, A. Pectinase from Microorganisms and Its Industrial Applications. Sci. World J. Vol. 2022, 2022, 1881305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamdar, N.; Dike, A.; Jadhav, A. Isolation, Screening, and Identification of Pectin Degrading Bacteria from Soil. J. Chem. Health Risks JCHR 2024, 14, 930–938. [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson, M.; Drake, H.; Bengtson, S.; Rasmussen, B. A Cryptic Alternative for the Evolution of Hyphae. BioEssays 2020, 42, 1900183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- José Carlos, D.L.-M.; Leonardo, S.; Jesús, M.-C.; Paola, M.-R.; Alejandro, Z.-C.; Juan, A.-V.; Cristóbal Noé, A. Solid-State Fermentation with Aspergillus niger GH1 to enhance Polyphenolic content and antioxidative activity of Castilla Rose Purshia plicata. Plants 2020, 9, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudeep, K.C.; Jitendra, U.; Dev, R.J.; Binod, L.; Dhiraj, K.C.; Bhoj, R.P.; Tirtha, R.B.; Rajiv, D.; Santosh, K.; Niranjan, K.; Vijaya, R. Production, Characterization, and Industrial Application of Pectinase Enzyme Isolated from Fungal Strains. Fermentation 2020, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Varghese, L.M.; Yadav, R.D.; et al. , A pollution reducing enzymatic deinking approach for recycling of mixed office waste paper. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 45814–45823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonji, R.E.; Itakorode, B.O.; Ovumedia, J.O.; Adedeji, O.S. Purification and biochemical characterization of pectinase produced by Aspergillus fumigatus isolated from soil of decomposing plant materials. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, M.; Pulicherla, K.K. Psychrophiles as the source for potential industrial psychrozymes. Recent Developments in Microbial Technologies. Recent Dev. Microb. Technol. 2021, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Kumar, V.; Singh, J.; Upadhyaya, C.P. Recent Developments in Microbial Technologies. Environmental and Microbial Biotechnology. 2021, 2662–169X. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, C.J.; Mims, C.W.; Blackwell, M. Intro. Mycology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1996; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, H.L.; Hunter, B.B. Illustrated Genera of Imperfect Fungi, 3rd ed.; Burgess Publishing Co.: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1972; p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, H.P.; Kaur, G. Optimization of cultural conditions for pectinase produced by fruit spoilage fungi. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 3, 851–859. [Google Scholar]

- Adedayo, M.R.; Mohammed, M.T.; Ajiboye AE and abdulmumini, S.A. Pectinolytic activity of Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus flavus grown on citrus parasidis peel in solid state fermentation. Glob. J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2021, 27, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghomary, A.E.; Shoukry, A.A.; EL-Kotkat, M.B. Productivity of pectinase enzymes by Aspergillus sp. isolated from Egyptian soil. Al-Azhar J. Agric. Res. 2021, 46, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budu, M.; Boakye, P.; Bentil, J.A. Microbial diversity, enzyme profile and substrate concentration for bioconversion of cassava peels to bioethanol. Preprints.org, 2023, 1, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Timothy, C. Cairns, Corrado Nai and Vera Meyer Aspergillus niger: A Hundred Years of Contribution to the Natural Products Chemistry. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2018, 5, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwelu, C.O.; Afeez, O.A.; Anthony, O.U.; Promise, O.A.; Mmesoma, U.-E.C.; Henry, O.E. Studies on Properties of Lipase Produced from Aspergillus sp. Isolated from Compost Soil. Adv. Enzym. Res. 2022, 10, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ametefe, G.D.; Oluwadamilare, L.A.; Ifeoma, C.J.; Olubunmi, I.I.; Ofoegbu, V.O.; Folake, F.; Orji, F.A.; Iweala, E.E.J.; Chinedu, S.N. Optimization of pectinase activity from locally isolated fungi and agrowastes. Res. Sq., 2021, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, M.T.M.; Ibrahim, D. Partial purification and characterisation of pectinase produced by Aspergillus niger LFP-1 grown on pomelo peels as a substrate. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2021, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oumer, O.J. Pectinase: Substrate, production and their biotechnological applications. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 2, 238761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalambigeswari, R.; Sangilimuthu, A.Y.; Narender, S.; Ushani, U. Isolation, identification, screening and optimization of pectinase producing soil fungi (Aspergillus niger). Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 9, 762–768. [Google Scholar]

|

| Microorganism | Zone of Pectinolytic Activity/mm |

|---|---|

| Aspergillus niger | 25.00 |

| Fusarium sp. | 23.00 |

| Trichoderma sp. | 20.00 |

| Aspergillus flavus | 20.00 |

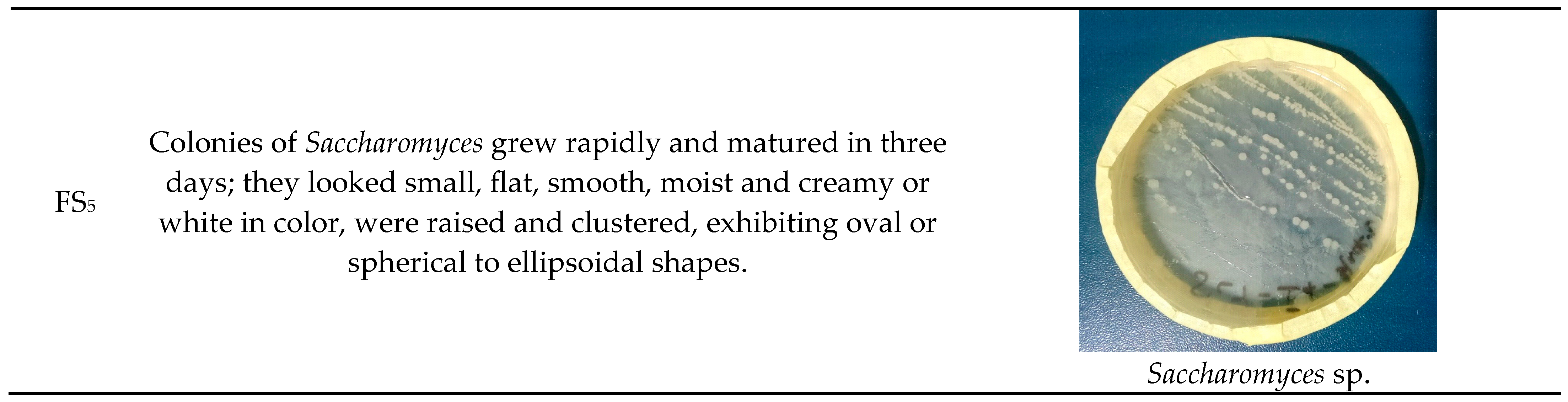

| Saccharomyces sp. | 7.00 |

| Microorganism | Reducing Sugar (mg/mL) | Enzyme Activity (U/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus niger (FS2) | 3.92 | 36.23 |

| Aspergillus flavus (FS1) | 3.68 | 32.52 |

| Trichoderma sp. (FS3) | 3.23 | 29.74 |

| Fusarium sp. (FS4) | 3.16 | 28.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).