1. Introduction

The Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal transition (EMT) is the process in which stationary epithelial cells become elongated, motile, bind to the extracellular matrix (ECM) and express mesenchymal cell markers. This process is instrumental for embryonic development and tissue regeneration, as well as for pathological conditions, such as during the initial stages of cancer invasion and metastasis. Increased level of the intermediate filament protein vimentin is a canonical marker for EMT, along with expression of fibronectin, and the switch from E- to N-cadherin expression [

1].

Vimentin is a protein closely linked to increased cell motility, as it is required for persistent cell migration, wound healing, and tissue regeneration [

2,

3,

4]. The protein level of vimentin correlates with poor survival in patients with lung cancer and is required for the development and metastasis of lung cancer cells in mice [

5,

6]. Vimentin is also required for the changes of cell shape which mimic the change from round to elongated that occurs during EMT [

7]. However, the role of vimentin in EMT and in lung cancer remains unclear. Vimentin is known to control cell motility by various pathways. In addition to regulation of the mechanical and physical properties of cells, vimentin enhances the function of microtubules in directed migration, and acts as a protein scaffold, which can allow protein production and interaction at the right subcellular site at the right time [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

The observation that vimentin filaments are required for the production of collagen I, the most abundant ECM protein in the body, via stabilization of collagen mRNA production, highlight the possibility that vimentin can control the EMT via increased collagen production at specific sites [

13]. We have previously found that vimentin polymerization into filaments occurs at the base of mature focal adhesions, but not of nascient cell adhesions to the ECM and described the role of vimentin dynamics in force-transduction over focal adhesions [

14,

15]. Most research on vimentin is based on overexpression or knock down studies. Therefore, how the dynamic properties of the vimentin filaments influence the EMT or the binding of proteins to vimentin is not known. We have previously synthesized a novel drug which specifically blocks the dynamics of vimentin filaments, and found it to change cell matrix adhesions, increase cellular contractile force and block cell migration [

15]. We hypothesize that vimentin dynamics is required for EMT of lung cancer cells, via the regulation of vimentin-interacting proteins.

Our data suggests that during the EMT of epithelial lung cancer cells, vimentin dynamics is required to gain EMT phenotypes such as increased cell spreading, increased cell migration speed, and a negative correlation between cell migration speed and directionality. We further observed that the dynamic turnover of vimentin filaments to be essential for the binding to vimentin of proteins previously known to regulate cancer. We also present ALD-R491 as a potential novel drug against EMT and cancer metastasis, and describe, in detail, the changes of the vimentin interactome that accompany EMT, with the most significant change in components of the extracellular matrix. In summary, these findings provide novel avenues for investigation of the regulation of cell motility, EMT and treatment of cancer metastasis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Treatments

A549 cell lines were purchased from ATCC (USA), cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, Germany) and supplemented with 10 % Fetal Bovine Serum (Biowest, France) and 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 microg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Cells were split weekly. The TGF-β1 was dissolved in 4 nM HCl, and equal final concentration of HCl was used as control. ALD-R491 was synthesized by Aluda Pharmaceuticals (USA), dissolved in DMSO (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and used at a final concentration of 5 μM.

2.2. Antibodies and Cell Dyes Blot

The antibodies used were as follows: anti-vimentin (V6389; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), pan-cytokeratin (ab8068; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-GAPDH (A1978; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and Horseradish-peroxide-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (GtxMu-004-DHRPX; ImmunoReagents, Raleigh, NC, USA). To stain for nuclei, we used 0.05 μg/mL Hoechst, and further phalloidin for F-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA).

2.3. Western Blot

The cytoskeletal isolation fractions were separated using 4% to 15% precast polyacrylamide gels (4568084; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The gels were then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (1704271; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using a transfer system (Trans-Blot Turbo; 1705150; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The blocking and developing of the membranes were carried out as previously described [

16]. Membranes were stripped after imaging vimentin and pan-keratin and exposed for 2 min to confirm that the membranes had been stripped, before incubating with GAPDH antibody as a loading control.

2.4. Immunoflourescence

The cells were immunostained as described previously and analyzed under an inverted phase contrast microscope (AxioVert 40 CFL; Zeiss, Germany) [

15]. Images shown in the figures are autoleveled in Fiji (version 1.54j.)

2.5. Live Cell Imaging

The cells were seeded at 375 cells/well in slide chambers (Cat.No: 94.6150.801, Sarstedt, Germany.). After 24 hours, DMEM was replaced with medium containing 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. Post additional 72 h, the medium was replaced with DMEM with ALD-R491, or DMSO control. 24 h thereafter, the medium was replaced with DMEM without phenol red, containing 0.05 μg/mL Hoechst (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and ALD-R491 or DMSO. This was followed by live-cell imaging for 10 h with images taken every 20 min using the Mica Microhub Imaging System and the software LasX (Leica Microsystems, Germany). Images shown are auto leveled in Fiji (version 1.54j.)

2.6. Image Analysis

Cell shape was quantified of images taken a 0 and 10 h timepoints, using FIJI version v1.54j [

17]. All cells with well demarcated borders were manually outlined with the “Freehand selections” tool. The analysis of the correlation between migration speed and persistence was done in R (version 4.4.1), as shown in the Supplementary data. Numbers of cells used for cell shape and spreading area analysis, control (N=33), TGF-β1 (N=11) and ALD-R491 (N=17).

2.7. Tracking Cell Migration

Cell migration was tracked by using the Fiji plug-in of TrackMate tool [

18]. The full documentation of this plug-in can be seen on the ImageJ wiki:

https://imagej.net/plugins/trackmate/ (accessed on 23 October 2024). The following specific settings were chosen for the tracking: Detector, Thresholding detector; Intensity threshold, 10; Simple LAP tracker: Linking max distance, 100 µm, Gap-closing max frame gap, 0; duration of tracks, 10 h (30 frames). All other settings remained at their default options. The tracks acquired were analyzed using the in-built algorithms (

https://imagej.net/plugins/trackmate/algorithms, accessed on 23 October 2024. Numbers of cells used for migration, control (N=48), TGF-β1 (N=119) and ALD-R491 (N=120) for cell migration.

2.8. Monitoring Cell Division

Cell division was monitored for 10 hours by counting the cell nuclei using Fiji (version 1.54j). All cells with well demarcated and not overlapping cell nuclei were manually outlined with the “Freehand selections” tool. Cells that underwent cell division and cells that failed to divide, showing “hourglass” cell shape were counted. Numbers of total cells used for cell division, control (N=231), TGF-β1 (N= 111), and TGF-β1+ALD R491 (N = 200). All images shown are auto leveled in Fiji (version 1.54j.).

2.9. Proteomic Analysis Using Label Free Quantification Mass Spectrometry

Briefly, five micrograms of protein from intermediate filament fraction [

19] were diluted to 1 M urea using 50 mM NH4HCO3 and processed as previously described [

20]. Briefly, samples were reduced and alkylated by the sequential addition of 5 mM dithiothreitol (30 min, room temperature) and 15 mM iodoacetamide (20 min on ice) prior to trypsin digestion ratio of 1:50 protein desalted and analyzed by nano-LC–MS/MS. Peptide separation was achieved by reverse phase HPLC with two mobile phase gradient system, using an C18 column (EASY-Spray PepMap RSLC; 50 cm × 75 μm ID, 2 μm; 40 °C; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and flow rate of 300 nl/min. Solvent A (0.1 % formic acid in water) and solvent B (0.1 % formic acid in 80 % acetonitrile) at 300 nl/min flow rate (RSLCnano HPLC system; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a gradient program of 0–5 min at 3 % B, then increasing from 3 % B to 50 % B over the next 30 min. Mass spectrometry was performed using a(Q Exactive HF hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Data-dependent aquisition was performed with 10 product ion scans (centroid: resolution, 30,000; automatic gain control, 1 × 105 maximum injection time, 60 ms; isolation: normalized collision energy, 27; intensity threshold, 1 × 105) per full mass spectrometry scan (profile: resolution, 120,000; automatic gain control, 1 × 106; maximum injection time, 60 ms; scan range, 375–1500

m/z).

2.10. Protein Identification, Relative Quantification, Bioinformatic Functional Profiling and Interaction Analysis

Proteins were identified by searching the mass spectrometry data files against the Homo sapiens proteome database (

www.uniprot.org/proteomes/UP000005640, downloaded, 2 August 2021; 78120 entries) using MaxQuant v. 1.6.4.0 with the label free quantification (LFQ) and intensity-based absolute quantification (iBAQ) options selected [

21,

22,

23]. Default settings were used with search parameters set to include the following modifications: carbamidomethyl-Cys (fixed); Met oxidation; protein N-terminal acetylation (variable); maximum of two missed tryptic cleavages. Peptide-spectrum and protein identifications were filtered using a target-decoy approach at a false discovery rate (FDR) of 1%. Statistical analyses were performed using LFQ-Analyst (bioinformatics.erc.monash.edu/apps/LFQ-Analyst/, accessed 18 October 2021), where the LFQ intensity values were used for protein quantification [

24]. Missing values were replaced by values drawn from a normal distribution of 1.8 standard deviations and a width of 0.3 for each sample (Perseus-type). Protein-wise linear models combined with empirical Bayesian statistics were used for differential expression analysis using the Bioconductor package

limma, whereby the adjusted P-value cut-off was set at 0.05- and 2-fold change cut-off was set at 1. The Benjamini–Hochberg method of FDR correction was applied. Analysis of the relative amount of specific intermediate filament proteins in the enriched intermediate filament fractions were calculated using iBAQ values. This is a method for calculation of the relative abundance of proteins in a dataset, which is achieved by dividing the total precursor intensities by the number of theoretically observable peptides of the protein. Proteins were relatively quantified by 2 or more unique peptides. The g: Profiler tool was used for functional enrichment analysis g:Profiler (version e104_eg51_p15_3922dba) with the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR method applying a significance threshold of 0.05 [

16]. The Min and Max size settings of the functional category were set to 3 and 500, respectively, with No electronic gene ontology (GO) annotations selected. GO terms for Molecular Function, Biological Process, Cellular Compartment, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Reactome were assigned. The species was set to Homo sapiens. The data presented in this study is analyzed using the same methods as previously described [

25]. The proteins in the list of changes of the interactome were analyzed with STRING database.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the ggpubr and rstatix packages in R (version 4.4.1). The shape and migration parameters were compared using pairwise, two-sided t-tests. Figures/Graphs were created using ggplot2 and patchwork packages in R. Significance was determined at p ≤ 0.05. Pearson’s correlation between mean speed and persistence was calculated using linear regression.

3. Results

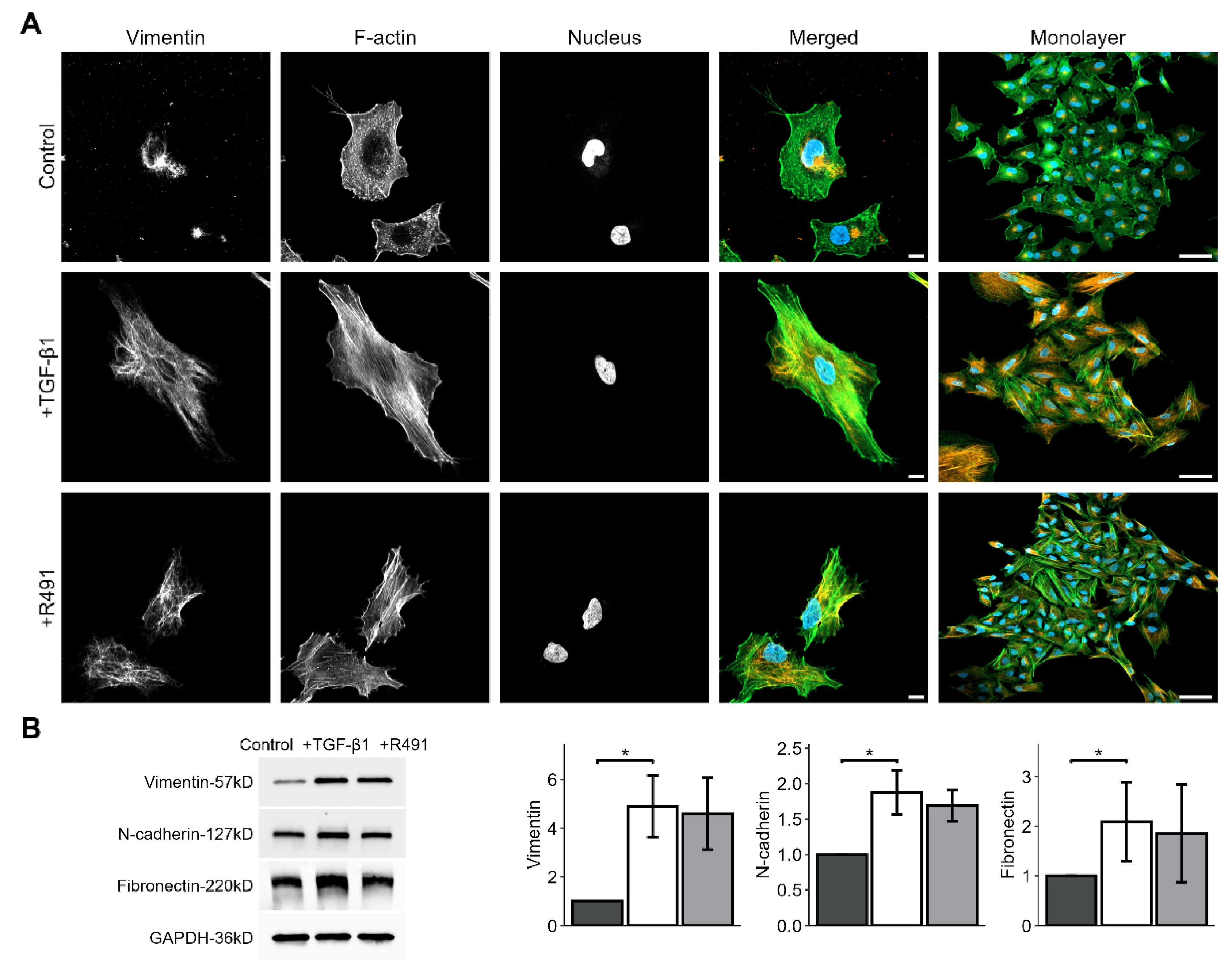

3.1. ALD-R491 Partially Reverses Phenotypes of the Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition

The intermediate filament protein vimentin regulates cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix, cell shape and motility, all key for EMT-mediated cancer invasion [

14]. To determine whether the vimentin-targeting drug ALD-R491 reverses EMT, we induced EMT in epithelial lung cancer cells with TGF-β1, followed by treatment with ALD-R491. TGF-β1-treated cells showed increased levels of EMT markers, such as vimentin, N-cadherin and fibronectin, and increased formation of actin-stress fibres, all previously described markers of EMT. The ALD-R491 partially reversed these phenotypes of EMT (

Figure 1A). The epithelial lung cancer cells showed minor, but detectable levels of vimentin, with vimentin filaments mainly localised around the nucleus. TGF-β1-treatment resulted in a spatial re-organization of vimentin towards the periphery of the cell (

Figure 1A). Subsequent ALD-R491-treatment caused loss of actin stress fibres, and a more central position of vimentin filaments around the nuclei. ALD-R491 did not change the total protein levels of the EMT markers in the cells. These observations suggest that ALD-R491 can reverse a subset of mesenchymal cell phenotypes to epithelial.

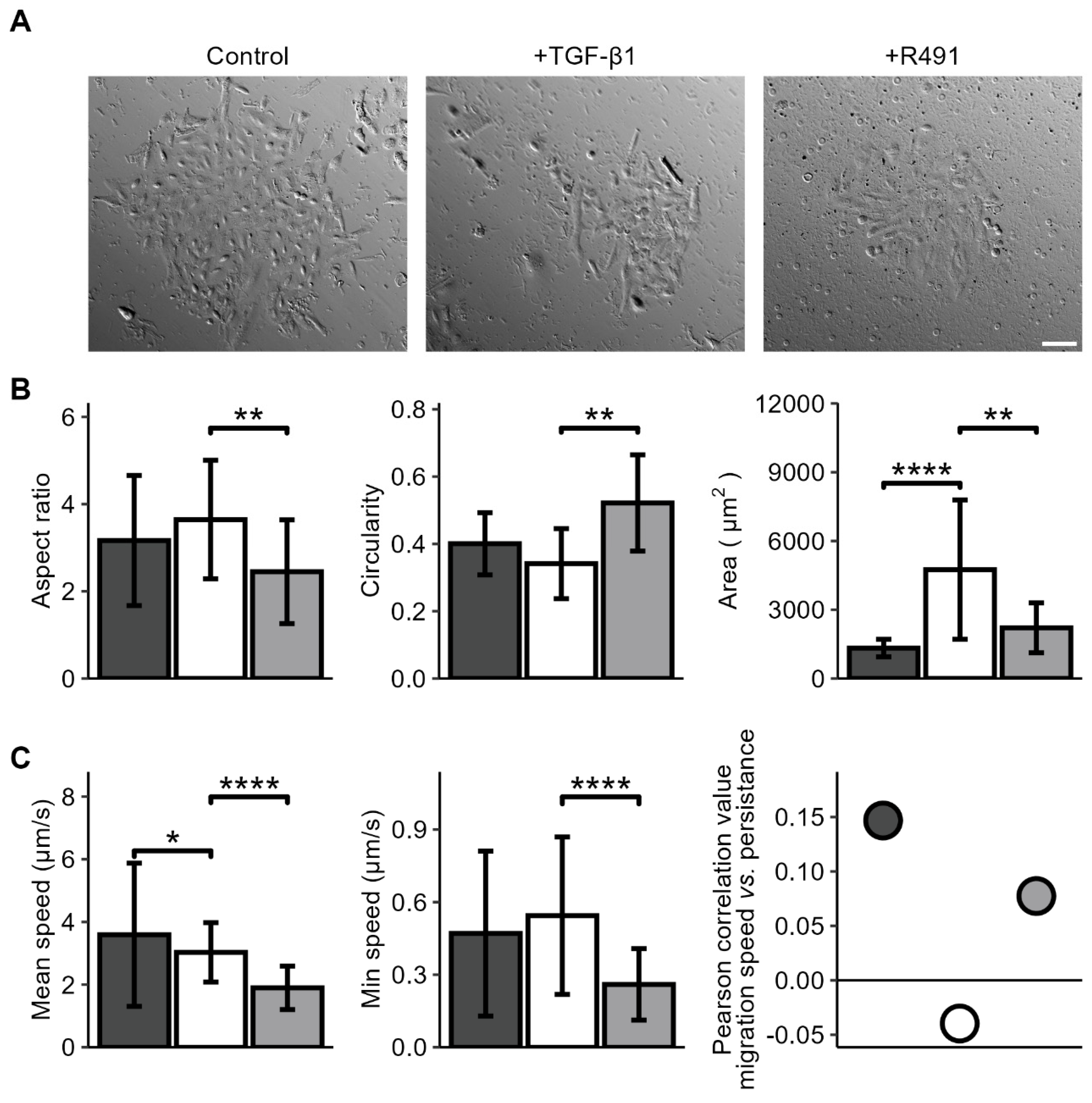

We then aimed to determine if vimentin dynamics is required for the changes of cell shape and motility that occur during EMT. For this, we induced EMT in the A594 lung cancer cells with TGF-β1, followed by ALD-R491-treatment, as described earlier. While the untreated A594 lung cancer cells displayed polygonal epithelial morphology, TGF-β1 -treated cells become less cohesive and slightly more elongated, a phenotype that was partly reversed by treatment with ALD-R491 (

Figure 2). Besides, TGF-beta treated cells become less round, a phenotype that significantly reversed by ALD-R491 treatment. The TGF-β1-treatment significantly increased the spreading area of the cells. TGF-β1 further increased the minimum cell speed of migration and changed the minor positive correlation between cell migration speed and migration directionality from positive to negative. These phenotypes were reversed upon ALD-R491-treatment (

Figure 2 and

Suppl. Figure S1). Taken together, these findings suggest that the dynamics of vimentin filaments can contribute to the changes in cell shape and migration that accompany EMT.

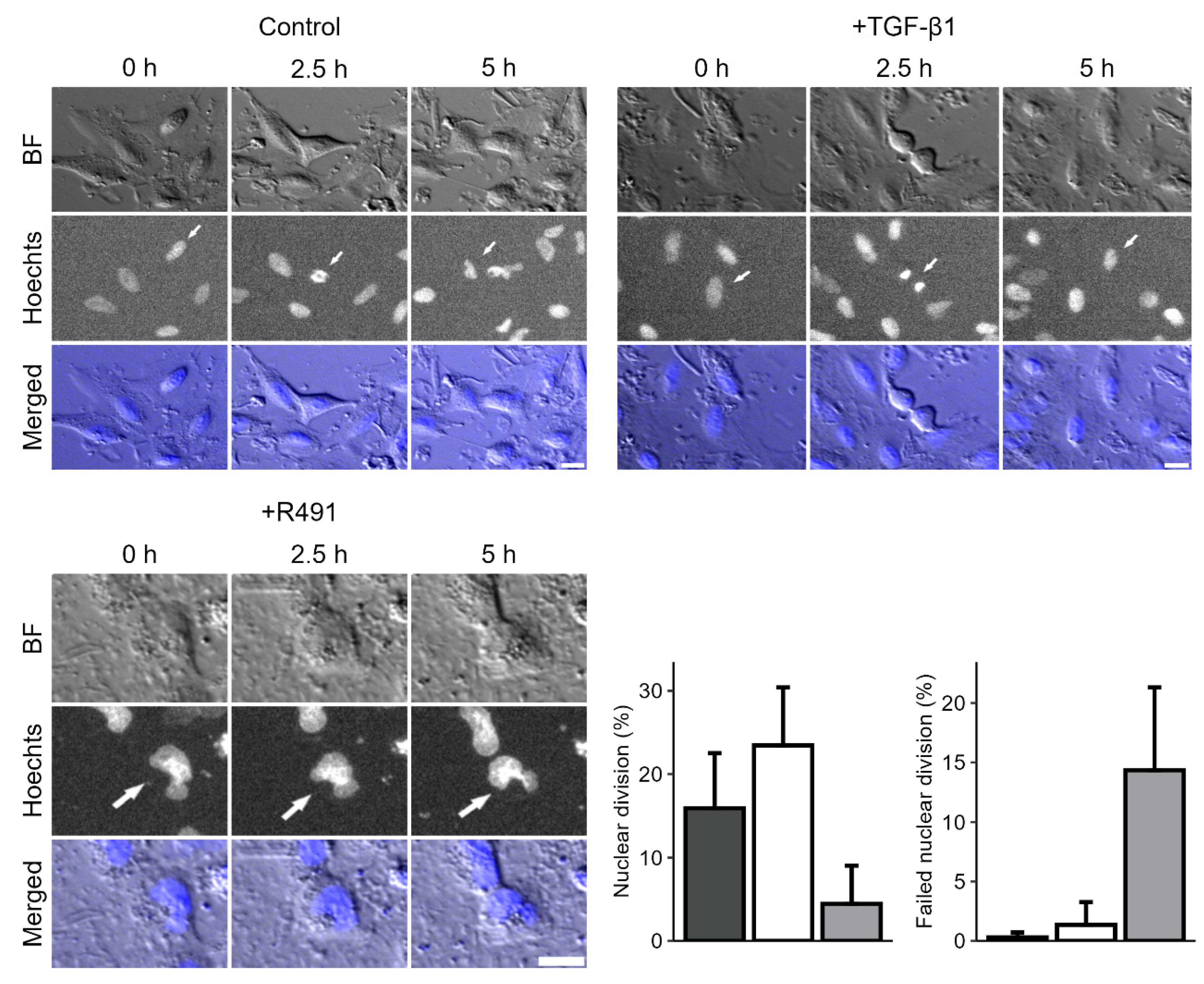

During live-cell imaging of the cells, we further observed that ALD-R491-treated cells displayed a trend towards abnormal division of their nuclei, as compared to the control. Many single cells failed to divide and showed an hour-glass-shaped nucleus that remained deformed or two nuclei. The DNA appeared more condensed in these deformed nuclei, as compared to control (

Figure 3). This suggests that the dynamic turnover of vimentin filaments can regulate the nuclear shape and division during mitosis.

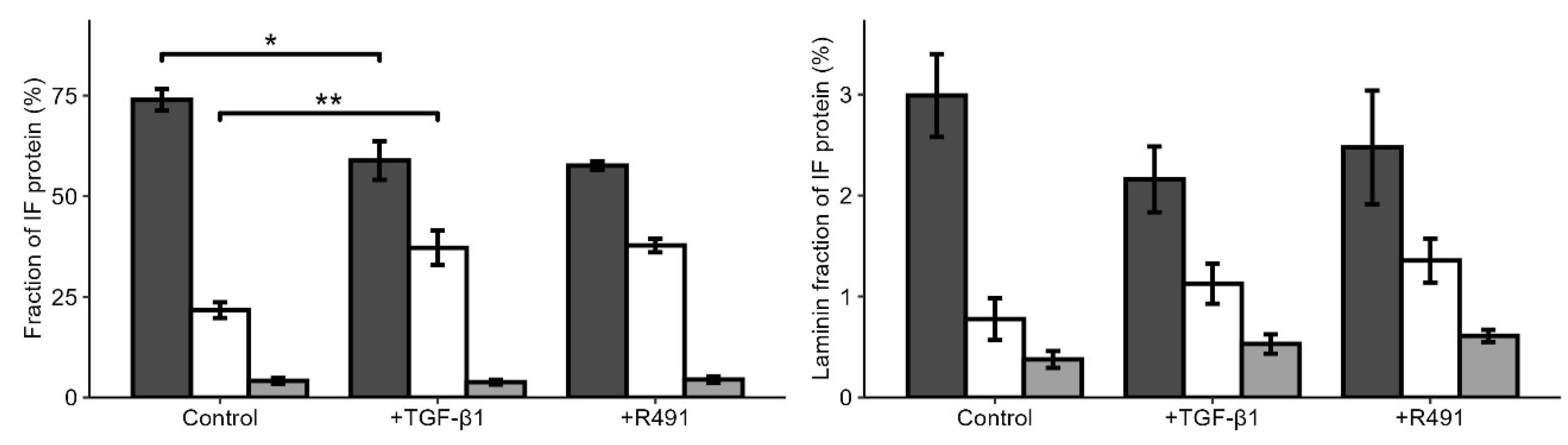

3.2. EMT-Increased Binding of Extracellular Matrix, Cell Motility, Cytokinesis, Cytoskeletal and RNA-Binding Proteins to Vimentin, is Partially Reversed by ALD-R491

Vimentin has been proposed to act as a molecular scaffold that regulates intracellular signaling [

26]. To gain insights into how EMT changes the relative proportion of intermediate filaments in epithelial lung cancer cells, and the proteins that bind to these filaments, we purified the intermediate filament fraction of the cytoskeleton in the cells, followed by Mass spectrometry. The vast majority of intermediate filaments in the epithelial A594 cells were keratins, mainly keratin 1, 7, 8, and 18. However, also low levels of vimentin were detected (

Figure 4,

Suppl. Table S3). TGF-β1 increased the levels of vimentin in the intermediate filament fraction around two-fold, levels that did not change upon subsequent ALD-R491-treatment (

Figure 4). The total levels of lamins and the ratio between variants of lamins were not significantly influenced by the ALD-R491-treatment (

Figure 4,

Suppl. Table S2).

To determine if, and how ALD-R491 can control the capacity of vimentin to regulate EMT, we characterised the protein interactome that bound to the intermediate filament fraction of cells. For this, we identified and relatively quantified 838 proteins in the intermediate filament fraction, of which many were not previously known to bind to intermediate filaments. We observed that TGF-β1 changed the binding of 24 proteins to the intermediate filaments, of which all increased their levels (

Table 1). Most of these EMT-induced interfilament-binding proteins were components or regulators of the extracellular matrix (ECM), cell –matrix adhesion, cytoskeleton and cell migration (

Figure 5). The most prononced change, with a fold change of 137, was of variants of fibronectin, which increased the binding to vimentin upon EMT. These included Fibronectin 1 (FN1), Anastellin; Uhl-Y1, Ugl-Y2, and Ugl-Y3. Fibronectin promotes which cell adhesion, spreading and migration in health and disease [

27,

28]. Proteins previously known to bind to fibronectin also showed an increased binding, i.e. Supervillin, which induces cell protrusions and regulates acto-myosin-based contractile force, and Transglutaminase-2 (TGM-2), which promotes integrin-fibronectin binding and activates TGF-β1 signalling [

29,

30,

31,

32].

We observed increased levels of additional proteins of TGF-β1 signaling, such as PML and TGF-β1 itself [

33]. The TGF-β1-treatment further increased the levels of proteins known to induce cell migration, such as SON, Kinesin Family Member 4A, Aminopeptidase, Drebin-1, SUN2, Transmembrane protein 43, Cardesmon, Spectrin [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. In addition to a role in migration, the proteins SON and Kinesin Family Member 4A also regulate the cell cycle [

40,

43]. Proteins known to regulate the contractile forces that cells use for cell migration were also identified, such as Drebin-1, SUN2 and Cardesmon [

44], along with aminopeptidase which regulates cell-ECM interactions [

36]. TGF-β1 further induces the binding of cytoskeletal regulators, such as Neurabin-2, Drebin-1 alpha-actinin-1, Spectrin, and Filamin A [

45,

46,

47]. Alpha-actinin-1, Spectrin, and Filamin A are actin crosslinkers which suppresses actin branching and ruffling [

48], and alpha-actinin-1 is further required for EMT [

49]. Additionally, we observed that proteins that process RNA, e.g. SON, and THR3 were increased upon TGF-β1-treatment (

Table 1, and

Supplementary Table S1). Taken together, these observations suggest that TGF-β1 significantly increases the binding to intermediate filaments by proteins that contribute to EMT through ECM-cell adhesion, cytoskeletal organization, and cell migration.

To determine if ALD-R491 can revert the EMT-associated intermediate filament interactome to normal, we compared it between TGF-β1-treated cells, that subsequently were treated with ALD-R491 or DMSO control. We observed that the ALD-R491 reversed the TGF- β1- induced binding of RNA splicing proteins to the intermediate filaments (

Table 2,

Figure 5,

Suppl. Figures S2 and S3). These included the binding of the protein SON, which was reduced to levels prior to TGF- β1-treatment (

Table 2). SON is an mRNA splicing cofactor that is required for mitosis and cell migration

[34,50]. We also observed the reduced binding to the intermediate filaments of the protein FUS and of Aldehyde dehydrogenase. FUS is part of the hnRNP complex and supports the stability of pre-mRNA, mRNA export and stability

[51–54]. The TGF-β1-treatment increased the proportion of these two proteins, although at fold-change that was slightly lower than the 2-fold cut off value we used. Taken together, these findings suggest that ALD-R491-mediated inhibition of vimentin dynamics suppresses the spatial and timely localization of proteins to the subcellular site required for dynamic cytoskeletal, mechanical, morphological and motile changes.

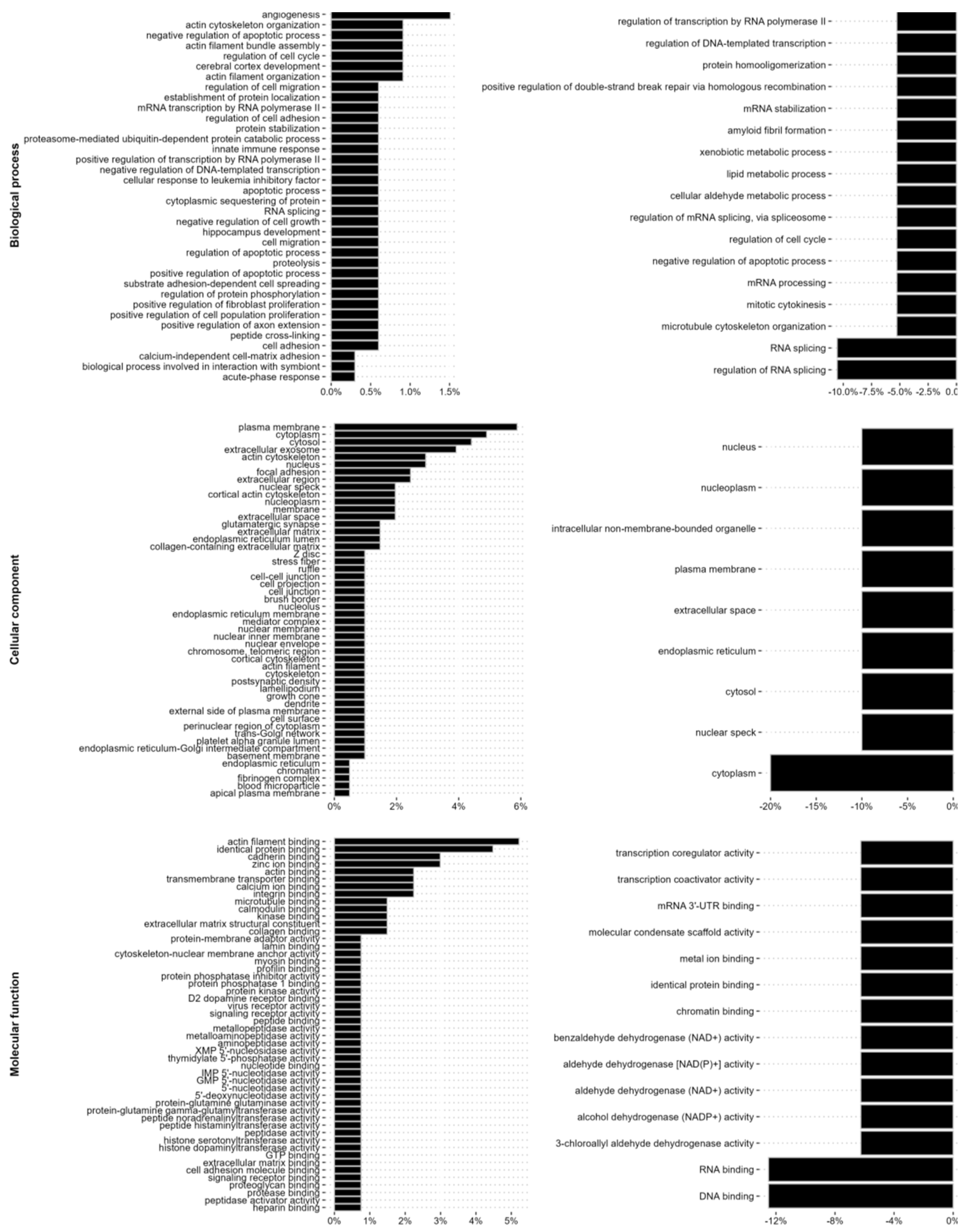

We further analyzed the changes in the intermediate filament interactome with regard to biological process, cellular compartment and molecular mechanisms. TGF-β1 induced the binding of proteins previously known to localize to the plasma membrane and cytoskeleton of cells, as well as to cell-extracellular matrix adhesions, the extracellular space and the ECM, including the collagen-containing extracellular marix, and of proteins with a molecular function in the cytoskeleton, extracellular matrix or cell adhesion. In addition, we observed a lower, but still significantly increased binding to proteins with previously described function in the RNA splicing and RNA metabolism, as well as nuclear proteins with DNA binding properties, including the mRNA splicing protein SON (

Figure 5 and

Suppl. Table S1). Further treatment with ALD-R491 resulted in a decreased binding of proteins linked to RNA binding and RNA splicing, including SON, protein scaffolding and aldehyde dehydrogenase (

Figure 5,

Suppl. Figure S2, and Suppl. Table S2). Taken together, this highlights that vimentin filaments can regulate EMT via different signalling pathways and cellular functions.

4. Discussion

In this study, we show that ALD-R491, a small chemical component that specifically targets and suppresses the dynamic turnover of vimentin intermediate filaments, reverses EMT phenotypes of lung cancer cells. Specifically, TGF-β1-induced mesenchymal phenotypes of cell spreading and migration, as well as a mesenchymal distribution or the cytoskeleton were reversed to epithelial. EMT increased the fraction of vimentin within the intermediate filaments of cells, and the binding to components and regulators of the ECM, the cytoskeleton, and cell motility. It also, to a lesser extent, it increased binding to RNA-binding proteins. ALD-R491 primarily reduced the binding of RNA-binding proteins.

The finding that ALD-R491-treatment reduced the spreading area of the cells, is in line with previous observations that the spatial distribution of vimentin filaments governs cell spreading [

7,

55]. The observation that ALD-R491 reduced the cell migration speed and persistence in the TGF-β1-treated lung cancer cells is consistent with previous findings that the dynamic turnover of vimentin filaments promotes cell migration

ex vivo and

in vivo, and that vimentin is required for invasion of lung cancer into the surrounding tissues [

3,

6,

56]. Our findings are in line with earlier observation that, in addition to the protein levels, also the dynamic properties of vimentin filaments are important for cell motility. For example, vimentin re-organization towards the cell periphery by p21-activaied kinase (PAK) increases cell migration, whereas oncogenes increase the soluble pool of vimentin, redistributes vimentin towards the nucleus, and induces cell invasion [

57,

58]. We have further observed that ALD-R491 reduced the cell migration speed of fibroblast cells, in a vimentin-dependent manner [

15]. The finding that ALD-R491 reversed the EMT-induced negative correlation between the persistence and speed of cell migration to positive, provides novel insights into the differences between epithelial and mesenchymal cell migration, and highlights that vimentin dynamics can be a main factor in the switch between EMT and these two separate and different types of cell migration.

We observed that EMT mainly increased the binding to the intermediate filament fraction of components and regulators of the ECM, cell adhesion, cell cytoskeleton, and cell motility. This can be an indirect consequence that the transcription and synthesis of these proteins are significantly increased when cell acquire the motile properties during EMT. However, in particular for fibronectin variants, where we observed an almost 140-fold increase in the binding to intermediate filaments, while total fibronectin levels only increased two-fold, it is also possible that the binding of fibronectin to vimentin acts to regulate the local distribution and deposition of fibronectin into the ECM. This would be similar to a recently proposed binding and/or buffering function of vimentin for a regulation of the deposition of integrin in the organisation of cell-matrix adhesions [

59,

60]. Fibronectin is known to significantly increase cell adhesion signaling, migration and invasion, and to contribute to EMT in cancer [

61]. TGF-β1 further induced the intermediate filament binding of the protein transglutaminase 2 (TGM2), an ECM component which stabilizes the ECM through strengthening the interaction between integrins and fibronectin and stimulates TGF-β1-signaling [

30,

31,

32]. Taken together with the essential role for vimentin to produce collagen I, via stabilization of collagen mRNA, these observations suggest that vimentin can regulate the EMT by different ECM-regulating pathways [

32]. The possible effect of ALD-R491 on the division of the nucleus during cytokinesis, is consistent with the earlier finding that vimentin dynamics contribute to successful mitosis through interaction with the actin cortex [

62]. While EMT induced the binding of the protein SON to vimentin, ALD-R491 reversed this binding back to normal levels in epithelial cells. SON is an RNA-binding protein, which is enriched in mitosis, and essential for cytokinesis and the proliferation of epithelial cancer cells [

50]. SON promotes the splicing of many cell-cycle and DNA-repair transcripts which possess weak splice sites, such as AURKB, PCNT, AKT1, which all function in cytokinesis, and required for correct microtubule dynamics, spindle pool separation during mitosis [

34,

40]. Together with our data, this suggests that the binding of SON to vimentin is important for the function of SON during mitosis. We observed a reversion of TGF-β1-increased binding to vimentin of FUS and ALDH1A1, although the TGF-β1-increase was under the 2-fold cut off that we used for the data. Both FUS and ALDH1A1 are previously known to suppress EMT. FUS is an RNA-binding protein, which impairs levels of E-cadherin in NSCLC patients, and cell migration [

63]. ALDH1A1 is an aldehyde dehydrogenase required for cell migration and invasion of A594 lung cancer cells [

64]. Vimentin filaments have previously been found to bind to proteins that stabilise mRNA, regulate mRNA splicing and to stimulate protein production, such as ribosomal proteins, and also found to assemble in clusters where ribosomes are enriched [

20,

65]. The presence of RNA-binding proteins highlights the possibility that vimentin-facilitated RNA metabolism and processing is instrumental for EMT, similar to the role of RNA processing in EMT in embryonic development [

65].

Taken together, our data is in line with earlier reports that vimentin filaments act as change-platform that allows spatially localized protein production when cells transiently change shape, as during EMT-induced cell migration and in cytokinesis. It further suggests that intact dynamic turnover of vimentin filament is essential for major changes in cell shape during cell migration and cytokinesis and for EMT. EMT and cell motility are fundamental processes in the progression and invasion of carcinomas, such epithelial-derived lung cancer, as EMT provides the cells with the mechanical, adhesive and motile properties that cause them to invade and metastasize into the surrounding tissue [

7]. Our observation that the drug ALD-R491 partially reverses EMT phenotypes of lung cancer cells suggests that the drug can be used to meet the urgent need to identify novel tools to suppress EMT.

The finding that the ALD-R491 drug partially reverses cell phenotypes of the EMT in lung cancer cells highlights the possibility to use ALD-R491 to develop future treatment against lung cancer metastasis. The identification of novel intermediate filament-binding proteins, and how these change during EMT and upon addition ALD-R491 increase our understanding about how vimentin dynamics can regulate EMT, cell invasion and cancer metastasis.

Taken together, our findings are in line with the hypothesis that the binding to vimentin of ECM and cell migration proteins, as well as proteins of RNA metabolism and function, such as the protein SON, allows the specific function of molecular pathways in the time and space required for dynamic changes of cells, such as during EMT and cancer metastasis. These observations expand our understanding of the functions of vimentin in cancer metastasis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary document 1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.B.G.; methodology, C.A.E, H.R.K.; software, A.K.; validation, C.A.E.; formal analysis, M.R., A.K., H.R.K., N.K., E.M.E., C.A.E,; investigation, M.R., A.K., H.R.K., E.M.E., C.A.E, K.D. A.K.B.G.; resources, D.S, R.C.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R, A.K.B.G..; writing—review and editing, M.R.,A.K.,N.K.,C.A.E, K.D., R.C., A.K.B.G.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, A.K.B.G..; project administration, A.K.B.G..; funding acquisition, K.D., A.K.B.G., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

The human cells used for the study were purchased from a cell bank which has obtained the informed consent.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Joanna Chowdry, University of Sheffield, for showing us the intermediate filament extraction method, the Karolinska Institutet core facility Biomedicum Imaging (BIC) and Thommie Karlsson, Micromedics (Sweden) for expert advice on Live Cell Imaging, and the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), the Portuguese Government (PEst-OE/QUI/UI0674/2013) and the Agência Regional para o Desenvolvimento da Investigaçaõ Tecnologia e Inovação (ARDITI), M1420-01-0145-FEDER-000005 Centro de Química da Madeira (CQM) (Madeira 14–20) for financial and administrative support, and The QExactive HF orbitrap mass spectrometer was funded by BBSRC, UK (award no. BB/M012166/1).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- S. Usman et al., "Vimentin Is at the Heart of Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) Mediated Metastasis," Cancers (Basel), vol. 13, no. 19, Oct 5 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Menko, B. M. Bleaken, A. A. Libowitz, L. Zhang, M. A. Stepp, and J. L. Walker, "A central role for vimentin in regulating repair function during healing of the lens epithelium," Mol Biol Cell, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 776-90, Mar 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Ridge, J. E. Eriksson, M. Pekny, and R. D. Goldman, "Roles of vimentin in health and disease," Genes Dev, vol. 36, no. 7-8, pp. 391-407, Apr 1 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Danielsson, M. K. Peterson, H. Caldeira Araujo, F. Lautenschlager, and A. K. B. Gad, "Vimentin Diversity in Health and Disease," Cells, vol. 7, no. 10, Sep 21 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Kidd, D. K. Shumaker, and K. M. Ridge, "The role of vimentin intermediate filaments in the progression of lung cancer," Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 1-6, Jan 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Berr et al., "Vimentin is required for tumor progression and metastasis in a mouse model of non-small cell lung cancer," Oncogene, vol. 42, no. 25, pp. 2074-2087, Jun 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Mendez, S. Kojima, and R. D. Goldman, "Vimentin induces changes in cell shape, motility, and adhesion during the epithelial to mesenchymal transition," FASEB J, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 1838-51. [CrossRef]

- M. Guo et al., "The role of vimentin intermediate filaments in cortical and cytoplasmic mechanics," Biophys J, vol. 105, no. 7, pp. 1562-8, Oct 1 2013. [CrossRef]

- N. Costigliola et al., "Vimentin fibers orient traction stress," Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 114, no. 20, pp. 5195-5200, May 16 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jiu et al., "Vimentin intermediate filaments control actin stress fiber assembly through GEF-H1 and RhoA," J Cell Sci, vol. 130, no. 5, pp. 892-902, Mar 1 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. Gan et al., "Vimentin Intermediate Filaments Template Microtubule Networks to Enhance Persistence in Cell Polarity and Directed Migration," Cell Syst, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 252-263 e8, Sep 28 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Coelho-Rato, S. Parvanian, M. K. Modi, and J. E. Eriksson, "Vimentin at the core of wound healing," Trends Cell Biol, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 239-254, Mar 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang and B. Stefanovic, "LARP6 Meets Collagen mRNA: Specific Regulation of Type I Collagen Expression," Int J Mol Sci, vol. 17, no. 3, p. 419, Mar 22 2016. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ostrowska-Podhorodecka, I. Ding, M. Norouzi, and C. A. McCulloch, "Impact of Vimentin on Regulation of Cell Signaling and Matrix Remodeling," Front Cell Dev Biol, vol. 10, p. 869069, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. R. Kim et al., "ALD-R491 regulates vimentin filament stability and solubility, cell contractile force, cell migration speed and directionality," Front Cell Dev Biol, vol. 10, p. 926283, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Alkasalias et al., "RhoA knockout fibroblasts lose tumor-inhibitory capacity in vitro and promote tumor growth in vivo," Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 114, no. 8, pp. E1413-E1421, Feb 21 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Schindelin et al., "Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis," Nat Methods, vol. 9, no. 7, pp. 676-82, Jun 28 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Tinevez et al., "TrackMate: An open and extensible platform for single-particle tracking," Methods, vol. 115, pp. 80-90, Feb 15 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Leech et al., "Proteomic analyses of intermediate filaments reveals cytokeratin8 is highly acetylated--implications for colorectal epithelial homeostasis," Proteomics, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 279-88, Jan 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Evans et al., "Metastasising Fibroblasts Show an HDAC6-Dependent Increase in Migration Speed and Loss of Directionality Linked to Major Changes in the Vimentin Interactome," Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 4, Feb 10 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Cox, M. Y. Hein, C. A. Luber, I. Paron, N. Nagaraj, and M. Mann, "Accurate proteome-wide label-free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ," Mol Cell Proteomics, vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 2513-26, Sep 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Cox and M. Mann, "MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification," Nat Biotechnol, vol. 26, no. 12, pp. 1367-72, Dec 2008. [CrossRef]

- B. Schwanhausser et al., "Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control," Nature, vol. 473, no. 7347, pp. 337-42, May 19 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Shah, R. J. A. Goode, C. Huang, D. R. Powell, and R. B. Schittenhelm, "LFQ-Analyst: An Easy-To-Use Interactive Web Platform To Analyze and Visualize Label-Free Proteomics Data Preprocessed with MaxQuant," J Proteome Res, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 204-211, Jan 3 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Danielsson et al., "Majority of differentially expressed genes are down-regulated during malignant transformation in a four-stage model," Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 110, no. 17, pp. 6853-8, Apr 23 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Ivaska, H. M. Pallari, J. Nevo, and J. E. Eriksson, "Novel functions of vimentin in cell adhesion, migration, and signaling," Exp Cell Res, vol. 313, no. 10, pp. 2050-62, Jun 10 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. Missirlis, T. Haraszti, H. Kessler, and J. P. Spatz, "Fibronectin promotes directional persistence in fibroblast migration through interactions with both its cell-binding and heparin-binding domains," Sci Rep, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 3711, Jun 16 2017. [CrossRef]

- O. Ramos Gde, L. Bernardi, I. Lauxen, M. Sant'Ana Filho, A. R. Horwitz, and M. L. Lamers, "Fibronectin Modulates Cell Adhesion and Signaling to Promote Single Cell Migration of Highly Invasive Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma," PLoS One, vol. 11, no. 3, p. e0151338, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Crowley, T. C. Smith, Z. Fang, N. Takizawa, and E. J. Luna, "Supervillin reorganizes the actin cytoskeleton and increases invadopodial efficiency," Mol Biol Cell, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 948-62, Feb 2009. [CrossRef]

- B. O. Odii and P. Coussons, "Biological functionalities of transglutaminase 2 and the possibility of its compensation by other members of the transglutaminase family," ScientificWorldJournal, vol. 2014, p. 714561, 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Jones et al., "Matrix changes induced by transglutaminase 2 lead to inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor growth," Cell Death Differ, vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 1442-53, Sep 2006. [CrossRef]

- H. Tatsukawa, Y. Furutani, K. Hitomi, and S. Kojima, "Transglutaminase 2 has opposing roles in the regulation of cellular functions as well as cell growth and death," Cell Death Dis, vol. 7, no. 6, p. e2244, Jun 2 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Hleihel et al., "A Pin1/PML/P53 axis activated by retinoic acid in NPM-1c acute myeloid leukemia," Haematologica, vol. 106, no. 12, pp. 3090-3099, Dec 1 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Kim et al., "De Novo Mutations in SON Disrupt RNA Splicing of Genes Essential for Brain Development and Metabolism, Causing an Intellectual-Disability Syndrome," Am J Hum Genet, vol. 99, no. 3, pp. 711-719, Sep 1 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. F. Hou et al., "KIF4A facilitates cell proliferation via induction of p21-mediated cell cycle progression and promotes metastasis in colorectal cancer," Cell Death Dis, vol. 9, no. 5, p. 477, May 1 2018. [CrossRef]

- U. Lendeckel, F. Karimi, R. Al Abdulla, and C. Wolke, "The Role of the Ectopeptidase APN/CD13 in Cancer," Biomedicines, vol. 11, no. 3, Feb 28 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Shirao and Y. Sekino, "General Introduction to Drebrin," Adv Exp Med Biol, vol. 1006, pp. 3-22, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Koizumi and J. G. Gleeson, "Sun proteins enlighten nuclear movement in development," Neuron, vol. 64, no. 2, pp. 147-9, Oct 29 2009. [CrossRef]

- N. Zhang et al., "TMEM43 promotes the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by activating VDAC1 through USP7 deubiquitination," Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol, vol. 9, p. 9, 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Y. Ahn et al., "SON controls cell-cycle progression by coordinated regulation of RNA splicing," Mol Cell, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 185-98, Apr 22 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. Carrasco et al., "Differential gene expression profile between progressive and de novo muscle invasive bladder cancer and its prognostic implication," Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 6132, Mar 17 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Ackermann et al., "Downregulation of SPTAN1 is related to MLH1 deficiency and metastasis in colorectal cancer," PLoS One, vol. 14, no. 3, p. e0213411, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Sheng, S. L. Hao, W. X. Yang, and Y. Sun, "The multiple functions of kinesin-4 family motor protein KIF4 and its clinical potential," Gene, vol. 678, pp. 90-99, Dec 15 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Bougaran and V. L. Bautch, "Life at the crossroads: the nuclear LINC complex and vascular mechanotransduction," Front Physiol, vol. 15, p. 1411995, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shan, S. M. Farmer, and S. Wray, "Drebrin regulates cytoskeleton dynamics in migrating neurons through interaction with CXCR4," Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 118, no. 3, Jan 19 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Blakley et al., "Mobility of the spin-labeled side chains of some novel antifolate inhibitors in their complexes with dihydrofolate reductase," Eur J Biochem, vol. 196, no. 2, pp. 271-80, Mar 14 1991. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang et al., "Critical roles of alphaII spectrin in brain development and epileptic encephalopathy," J Clin Invest, vol. 128, no. 2, pp. 760-773, Feb 1 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang et al., "Characterization of LIMA1 and its emerging roles and potential therapeutic prospects in cancers," Front Oncol, vol. 13, p. 1115943, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. F. Xie et al., "High ACTN1 Is Associated with Poor Prognosis, and ACTN1 Silencing Suppresses Cell Proliferation and Metastasis in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma," Drug Des Devel Ther, vol. 14, pp. 1717-1727, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Huen et al., "SON is a spliceosome-associated factor required for mitotic progression," Cell Cycle, vol. 9, no. 13, pp. 2679-85, Jul 1 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. Yamaguchi and K. Takanashi, "FUS interacts with nuclear matrix-associated protein SAFB1 as well as Matrin3 to regulate splicing and ligand-mediated transcription," Sci Rep, vol. 6, p. 35195, Oct 12 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yu and R. Reed, "FUS functions in coupling transcription to splicing by mediating an interaction between RNAP II and U1 snRNP," Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 112, no. 28, pp. 8608-13, Jul 14 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, S. Liu, G. Liu, A. Ozturk, and G. G. Hicks, "ALS-associated FUS mutations result in compromised FUS alternative splicing and autoregulation," PLoS Genet, vol. 9, no. 10, p. e1003895, Oct 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. Baechtold, M. Kuroda, J. Sok, D. Ron, B. S. Lopez, and A. T. Akhmedov, "Human 75-kDa DNA-pairing protein is identical to the pro-oncoprotein TLS/FUS and is able to promote D-loop formation," J Biol Chem, vol. 274, no. 48, pp. 34337-42, Nov 26 1999. [CrossRef]

- C. D. Lynch, A. M. Lazar, T. Iskratsch, X. Zhang, and M. P. Sheetz, "Endoplasmic spreading requires coalescence of vimentin intermediate filaments at force-bearing adhesions," Mol Biol Cell, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 21-30, Jan 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Richardson et al., "Vimentin Is Required for Lung Adenocarcinoma Metastasis via Heterotypic Tumor Cell-Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Interactions during Collective Invasion," Clin Cancer Res, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 420-432, Jan 15 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Tang, Y. Bai, and S. J. Gunst, "Silencing of p21-activated kinase attenuates vimentin phosphorylation on Ser-56 and reorientation of the vimentin network during stimulation of smooth muscle cells by 5-hydroxytryptamine," Biochem J, vol. 388, no. Pt 3, pp. 773-83, Jun 15 2005. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Rathje et al., "Oncogenes induce a vimentin filament collapse mediated by HDAC6 that is linked to cell stiffness," Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 111, no. 4, pp. 1515-20, Jan 28 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Jang, H. J. Park, W. Seong, J. Kim, and C. Kim, "Vimentin-mediated buffering of internal integrin beta1 pool increases survival of cells from anoikis," BMC Biol, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 139, Jun 24 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ostrowska-Podhorodecka et al., "Vimentin tunes cell migration on collagen by controlling beta1 integrin activation and clustering," J Cell Sci, vol. 134, no. 6, Mar 29 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Li et al., "Fibronectin 1 promotes melanoma proliferation and metastasis by inhibiting apoptosis and regulating EMT," Onco Targets Ther, vol. 12, pp. 3207-3221, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Shaebani, R. Jose, L. Santen, L. Stankevicins, and F. Lautenschlager, "Persistence-Speed Coupling Enhances the Search Efficiency of Migrating Immune Cells," Phys Rev Lett, vol. 125, no. 26, p. 268102, Dec 31 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Lyu and Q. Wang, "Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: A clinical analysis," Oncol Lett, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 1855-1862, Aug 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Fan et al., "ALDH3A1 driving tumor metastasis is mediated by p53/BAG1 in lung adenocarcinoma," J Cancer, vol. 12, no. 16, pp. 4780-4790, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Guzman-Espinoza, M. Kim, C. Ow, and E. J. Hutchins, ""Beyond transcription: How post-transcriptional mechanisms drive neural crest EMT"," Genesis, vol. 62, no. 1, p. e23553, Feb 2024. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

TGF-β1 -induced cell and cytoskeletal EMT phenotypes in A594 lung cancer cells, with and without ALD-R491-treatment. A594 cells treated without or with TGF-β1, and subsequent ALD-R491-treatment (R491), analysed with regard to (A) representative cells (left) with regard to vimentin, F-actin or nuclei, as indicated, with merged images showing vimentin (red), F-actin (green), and nuclei (blue). Scale bars 10 (left) and 50 µm (right). (B) Protein levels of EMT markers (left), as quantified (right) for control (dark grey), treatment with TGF-β1 (white) followed by ALD-R491 (light grey). Bar plots show mean, error bars standard deviation, p ≤ 0.05 (*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***), and p ≤ 0.0001 (****).

Figure 1.

TGF-β1 -induced cell and cytoskeletal EMT phenotypes in A594 lung cancer cells, with and without ALD-R491-treatment. A594 cells treated without or with TGF-β1, and subsequent ALD-R491-treatment (R491), analysed with regard to (A) representative cells (left) with regard to vimentin, F-actin or nuclei, as indicated, with merged images showing vimentin (red), F-actin (green), and nuclei (blue). Scale bars 10 (left) and 50 µm (right). (B) Protein levels of EMT markers (left), as quantified (right) for control (dark grey), treatment with TGF-β1 (white) followed by ALD-R491 (light grey). Bar plots show mean, error bars standard deviation, p ≤ 0.05 (*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***), and p ≤ 0.0001 (****).

Figure 2.

ALD-R491 reverses EMT-dependent cell spreading and migration phenotypes to normal. A594 lung cancer cell treated without (dark grey) or with TGF-β1 (white) and ALD-R491 (R491) (light grey), as indicated, shown in (A) cell monolayers, Scale bar 100 µm, (B) cell aspect ratio, circularity, spreading area, and (C) cell migration speed, persistence and correlation between speed and persistence for control (dark grey), treatment with TGF-β1 (white) followed by ALD-R491 (light grey). Bar plots show mean, error bars standard deviation, p ≤ 0.05 (*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***), and p ≤ 0.0001 (****).

Figure 2.

ALD-R491 reverses EMT-dependent cell spreading and migration phenotypes to normal. A594 lung cancer cell treated without (dark grey) or with TGF-β1 (white) and ALD-R491 (R491) (light grey), as indicated, shown in (A) cell monolayers, Scale bar 100 µm, (B) cell aspect ratio, circularity, spreading area, and (C) cell migration speed, persistence and correlation between speed and persistence for control (dark grey), treatment with TGF-β1 (white) followed by ALD-R491 (light grey). Bar plots show mean, error bars standard deviation, p ≤ 0.05 (*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***), and p ≤ 0.0001 (****).

Figure 3.

Treatment with ALD-R491 and nuclear division during mitosis. A594 lung cancer cells treated without (top left) and with TGF-β1 (top right panel), followed by ALD-R491 (R491) (lower left). Bright field images (BF), DNA staining by Hoechts and merged images with BF and DNA (blue), are shown, as indicated. White arrows indicating dividing cells. Scalebar, 20 µm, with quantifications shown (lower right panel), with A594 treated without (dark grey), with TGF- β1 (white) followed by ALD-R491 (light grey), with regard to proportion of nuclear division of all nuclei (left) and deformed, not dividing proportion of dividing nuclei (right panel). Bar plots show mean, error bars standard deviation, p ≤ 0.05 (*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***), and p ≤ 0.0001 (****).

Figure 3.

Treatment with ALD-R491 and nuclear division during mitosis. A594 lung cancer cells treated without (top left) and with TGF-β1 (top right panel), followed by ALD-R491 (R491) (lower left). Bright field images (BF), DNA staining by Hoechts and merged images with BF and DNA (blue), are shown, as indicated. White arrows indicating dividing cells. Scalebar, 20 µm, with quantifications shown (lower right panel), with A594 treated without (dark grey), with TGF- β1 (white) followed by ALD-R491 (light grey), with regard to proportion of nuclear division of all nuclei (left) and deformed, not dividing proportion of dividing nuclei (right panel). Bar plots show mean, error bars standard deviation, p ≤ 0.05 (*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***), and p ≤ 0.0001 (****).

Figure 4.

TGF-β1 increases vimentin and reduces keratin in the intermediate filament fraction of the cytoskeleton. Keratin (dark grey), vimentin (white) and lamins (light grey) in the intermediate filament fraction, or of (right panel) lamin A (dark grey), lamin B1 (white) and B2 (light grey) of all lamins, in A594 lung cancer cell treated without (control) or with TGF- β1 and subsequent ALD-R491, as indicated. Bar plots show mean, error bars standard deviation, p ≤ 0.05 (*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***), and p ≤ 0.0001 (****).

Figure 4.

TGF-β1 increases vimentin and reduces keratin in the intermediate filament fraction of the cytoskeleton. Keratin (dark grey), vimentin (white) and lamins (light grey) in the intermediate filament fraction, or of (right panel) lamin A (dark grey), lamin B1 (white) and B2 (light grey) of all lamins, in A594 lung cancer cell treated without (control) or with TGF- β1 and subsequent ALD-R491, as indicated. Bar plots show mean, error bars standard deviation, p ≤ 0.05 (*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***), and p ≤ 0.0001 (****).

Figure 5.

The EMT increases the binding to intermediate filaments of proteins that regulate the cell-extracellular matrix adhesion, cytoskeleton, cell shape and cell motility, while ALD-491 reduces binding of RNA metabolism and function. The changes of the vimentin interactome upon EMT (left) and by additional ALD-491-treatment (right panel) shown as percentages, with the Biological function (top), Cellular compartment (middle), and Molecular function (lower panel), as indicated.

Figure 5.

The EMT increases the binding to intermediate filaments of proteins that regulate the cell-extracellular matrix adhesion, cytoskeleton, cell shape and cell motility, while ALD-491 reduces binding of RNA metabolism and function. The changes of the vimentin interactome upon EMT (left) and by additional ALD-491-treatment (right panel) shown as percentages, with the Biological function (top), Cellular compartment (middle), and Molecular function (lower panel), as indicated.

Table 1.

Changes in protein levels for proteins altered in the vimentin interactome of TGFβ1-treated A549 cells, relative to the native epithelial A549 cells.

Table 1.

Changes in protein levels for proteins altered in the vimentin interactome of TGFβ1-treated A549 cells, relative to the native epithelial A549 cells.

| Protein |

Gene |

Protein ID |

TGFβ vs A549 (Fold change) |

| Fibronectin;Anastellin;Ugl-Y1;Ugl-Y2;Ugl-Y3 |

FN1 |

P02751 |

137.19 |

| Transforming growth factor-β1-induced protein ig-h3 |

TGF-Β1I |

Q15582 |

28.05 |

| Protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase 2 |

TGM2 |

P21980 |

17.63 |

| 5-nucleotidase |

NT5E |

P21589 |

6.92 |

| Aminopeptidase N |

ANPEP |

P15144 |

5.58 |

| Neurabin-2 |

PPP1R9B |

Q96SB3 |

4.92 |

| Zinc finger protein 185 |

ZNF185 |

O15231 |

4.86 |

| Drebrin |

DBN1 |

Q16643 |

4.32 |

| Caldesmon |

CALD1 |

E9PGZ1 |

4.08 |

| SUN domain-containing protein 2 |

SUN2 |

Q9UH99 |

3.92 |

| SON |

SON |

P18583 |

3.78 |

| CTP synthase 1 |

CTPS1 |

A0A3B3IRI2 |

3.68 |

| Bcl-2-associated transcription factor 1 |

BCLAF1 |

A0A3B3ITZ9 |

3.48 |

| Supervillin |

SVIL |

A0A6I8PIX7 |

3.23 |

| Protein PML |

PML |

P29590 |

3.18 |

| Protein disulfide-isomerase A4 |

PDIA4 |

A0A499FI48 |

2.85 |

| Transmembrane protein 43 |

TMEM43 |

Q9BTV4 |

2.62 |

| Uncharacterized protein C17orf85 |

C17orf85 |

Q53F19 |

2.58 |

| Thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein 3 |

THRAP3 |

A0A3B3ITZ9 |

2.36 |

| Alpha-actinin-1 |

ACTN1 |

P12814 |

2.25 |

| LIM domain and actin-binding protein 1 |

LIMA1 |

Q9UHB6 |

2.22 |

| Kinesin-like protein 14 |

KIF14 |

Q15058 |

2.11 |

| Spectrin alpha chain, non-erythrocytic 1 |

SPTAN1 |

Q13813 |

2.06 |

| Filamin-A |

FLNA |

P21333 |

2.01 |

Table 2.

Significantly changed proteins in vimentin interactome of TGFβ1- and ALD-R491-treated A549 cells, relative to TGFβ-treated A549 cells.

Table 2.

Significantly changed proteins in vimentin interactome of TGFβ1- and ALD-R491-treated A549 cells, relative to TGFβ-treated A549 cells.

| Protein |

Gene |

Protein ID |

ALD-R49 and TGFβ vs TGFβ

(Fold Change) |

| Protein SON |

SON |

P18583 |

- 4.89 |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase, dimeric NADP-preferring |

ALDH3A1 |

P30838 |

-2.62 |

| RNA-binding protein FUS |

FUS |

P35637 |

-2.62 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).