1. Introduction

Antimicrobial drug resistance (AR) is recognized as one of the most important global public health concerns [

1]. It could lead to the loss of 10 million lives annually by 2050. This is on top of the significant clinical and economic consequences and the quality - adjusted life year (QALY) lost [

2]. This makes AR as one of the largest challenges to global health and to health care systems around the world, demanding global, regional, and country and even hospital - specific collaborative solutions derived by epidemiological and microbiological data. Infections caused by antimicrobial multi-drug resistant bacteria, mainly Gram negative bacteria, in pediatric patients significantly increase morbidity, mortality, hospitalization and costs allocated to healthcare systems worldwide [

3]. QALY’s lost are tremendously more when infections by AR bacteria occur in infants and children than in adults. This is even more true in environments like PICU with critically ill and more or less immunocompromised patients.

Bacteria can acquire and transmit resistance through various mechanisms, among which extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases are increasingly important nowadays [

4]. There is an urgent need to reduce the spread of these resistant bacteria particularly among highly susceptible patients such as critically ill infants and children in order to save human lives. To this purpose surveying for a set of specific resistance genes in a high-risk endemic healthcare setting, in other words searching for a targeted resistome of the hospital unit, is extremely important for understanding the resistance problem that exists in the particular hospital unit and confronting it with enhanced infection control measures and with antimicrobial stewardship programs [

5]. These measures have been developed lately and can be used in individual hospitals and health regions or smaller hospitals.

We aimed to investigate whether targeted gene amplification when searched directly in clinical samples can be used as a rapid and effective tool for active surveillance of AR in an endemic Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). Secondary objectives were a) the comparison between the direct detection of targeted AR genes in stools and the culture-based phenotypic analysis, b) the comparison between the impact of an active surveillance program combined with enhanced and tailored infection control measures (EICM) based on the targeted resistome and infection control measures (ICM) used at routine clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design, patient population and clinical protocol:

The study was conducted in an eight-bed PICU within 18 months as part of an interventional initiative of Infection Control Committee of Hippokration General Hospital targeting to control spread of AR genes among critically ill pediatric patients in the PICU. The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Studies Committee of the Scientific Advisory Board of Hippokration Hospital. As the stool samples were taken routinely according to the hospital Infection Control Committee policy in the PICU, signing of informed consent by the parents og the patients was deemed unnecessary.

The clinical protocol consisted of three phases:

1) The baseline phase, which lasted five months determined the existing AR burden in the PICU. All patients hospitalized for at least 5 days in the PICU were screened for the presence of the AR genes using PCR directly applied to stool samples. The presence of four carbapenemases, namely blaKPC, blaOXA-48-like, blaVIM and blaNDM as well as blaTEM and blaSHV were evaluated by endpoint PCR. Patients, not bearing the resistance genes under study, were re-evaluated after ≥ 1 month for probable colonization.

2) The intervention phase was run for 8 months. During this time period the ICMs were intensified through the implementation of three infection control and prevention components: a) Enhanced compliance to routine active surveillance cultures: Weekly reminders for rectal swab collection were planned to be sent to the hospital’s microbiology department for routine surveillance cultures for AR detection, isolation and identification of pathogens and susceptibility testing with phenotypic assays. Sampling frequency evaluations before and after the intervention phase reflected the level of compliance to routine surveillance procedures. b) Monthly educational and training meetings of infection control and prevention team with PICU staff (physicians, nurses and rest of staff). Distribution of poster handouts and floor plans of colonized patients. c) Audits with feedback on antimicrobial consumption and infection control: Consumption of all antibiotics and carbapenems per month was expressed as number of defined daily doses (DDDs) per 100 bed-days. Compliance with hand hygiene (direct observation, percentage of hand hygiene performance to the total number of opportunities), consumption of antiseptic solution (liters per 100 bed-days) and Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSI rate, number of CLABSIs per 1000 central-line days), were used to assess the implementation of these measurements.

3) The maintenance phase of the AR surveillance protocol lasted for another 5 months and assessed the combinational effect of two surveillance factors: enhanced infection control measures mentioned above and the implementation of the targeted molecular panel of AR genes customized to represent the most frequently met AR gene burden in this specific PICU.

2.2. Targeted molecular analysis:

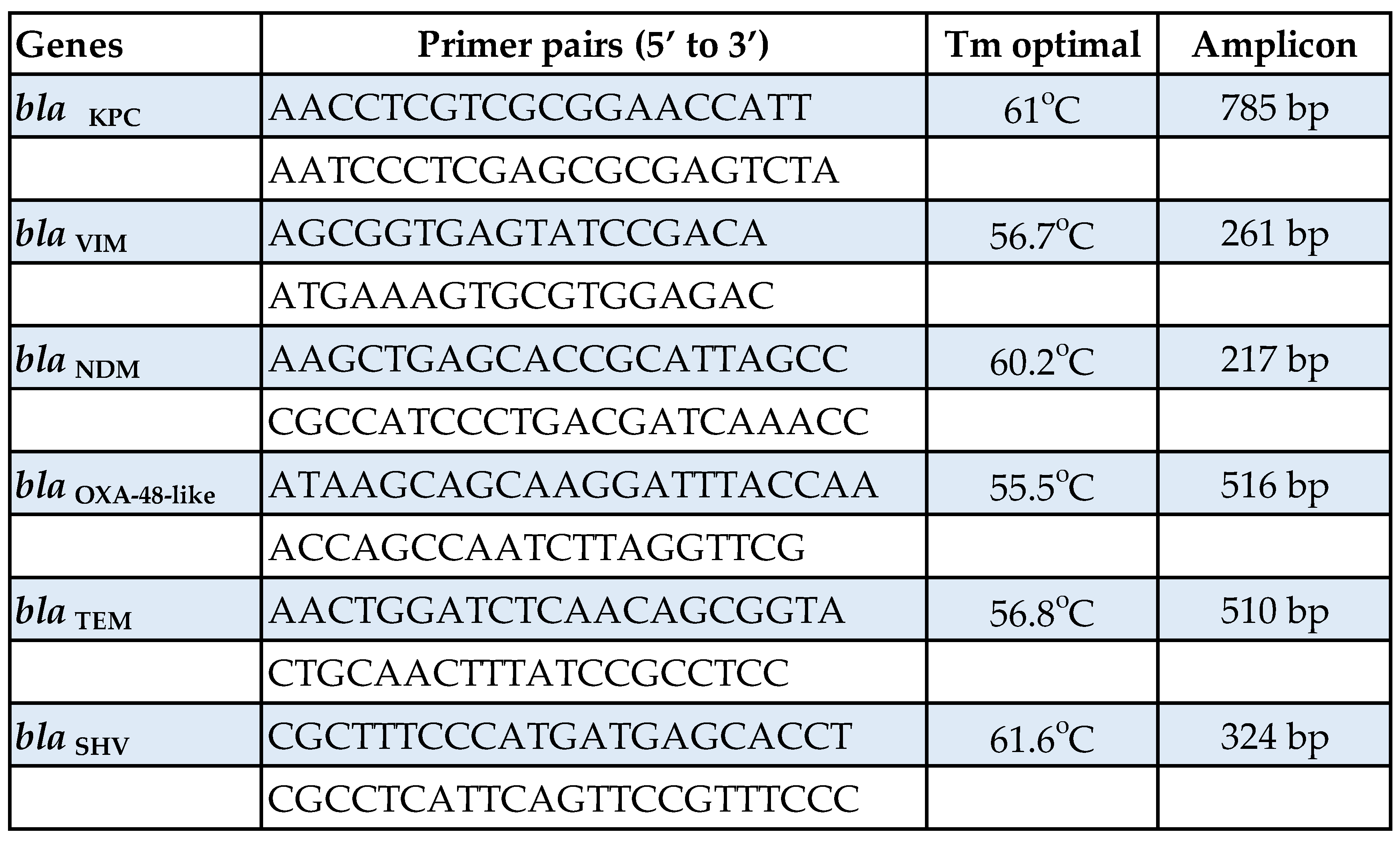

Stool samples were collected and divided into six 0.25-g portions and stored at -80o C until processed. DNA extraction directly from stool samples was performed using the QIAamp® PowerFecal® DNA Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer’s specifications. The AR genes studied were the following: blaKPC, blaVIM, blaNDM, blaOXA-48-like, blaTEM and blaSHV. AR was assessed by endpoint PCR using KAPA HiFi HotStart PCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems Inc, MA, USA) and specific primers for each targeted gene designed with Oligo 7.0 online software (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primer pair sequences, optimal annealing temperature and expected amplified product of indicated bla genes used to amplify AR genes directly from stool samples.

Table 1.

Primer pair sequences, optimal annealing temperature and expected amplified product of indicated bla genes used to amplify AR genes directly from stool samples.

The thermal protocol used was the following: initial denaturation at 95o C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 20 sec denaturation at 98o C, 15 sec annealing at 55.5o C - 61.6o C and 60 sec extension at 72o C and one cycle of 1 min final extension at 72o C. The amplified products, with a size between 217 bp - 785 bp in length, were visualized on 1.5% agarose gel after adding ethidium bromide to a final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml (ApliChem GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). Patients found negative for the resistance genes under study, were re-evaluated after at least 3 weeks for probable colonization.

3. Results

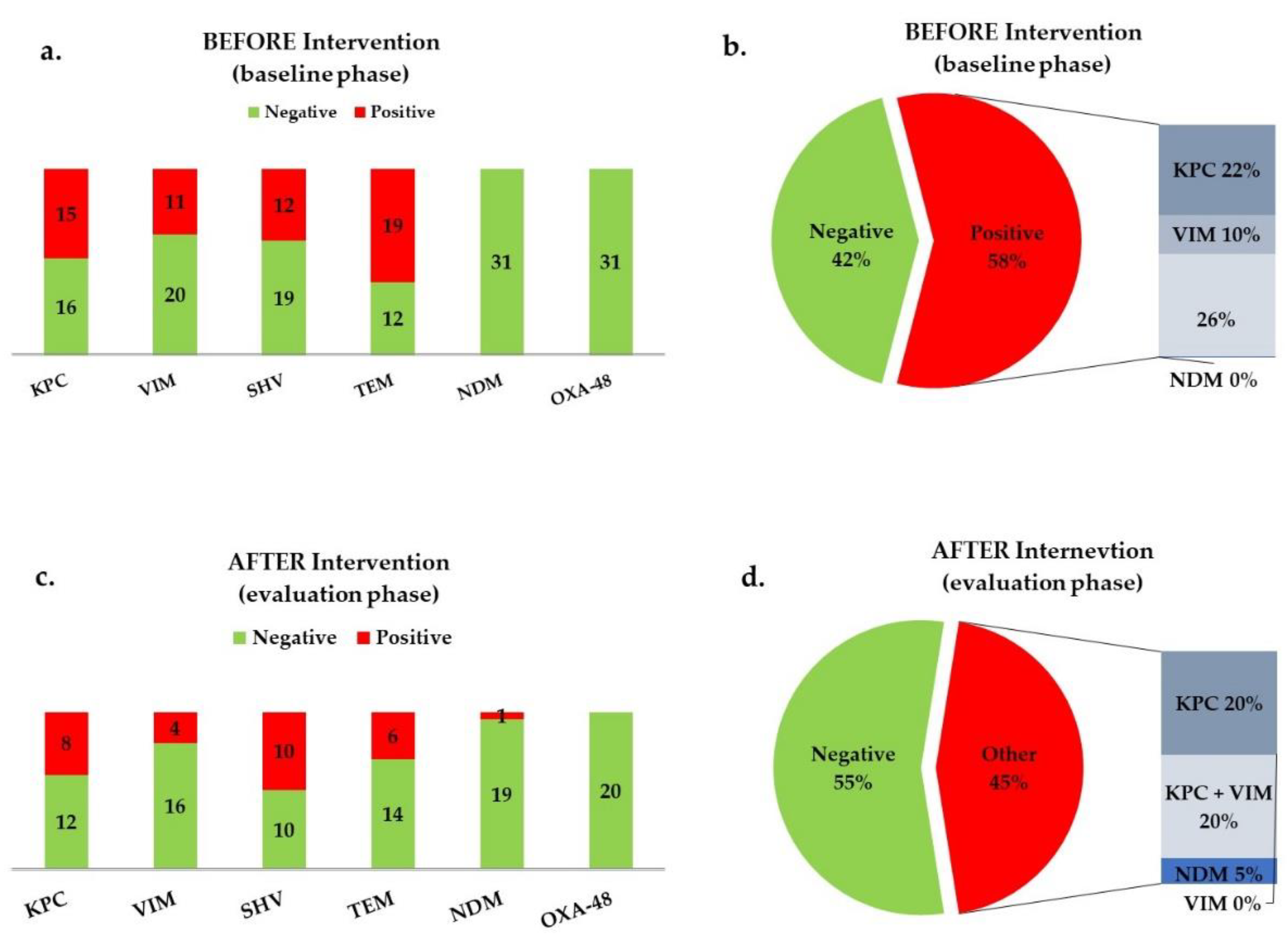

In total, 51 patients were included aged 3 mo - 14 yrs. During the Baseline period, 37 stool samples were collected from 31 patients. Molecular analysis for the presence of the AR genes studied (Table 1) gave the following results: 15 (48.4%) patients were colonized with bla

KPC, 11 (35.5%) with bla

VIM, 12 (38.7%) with bla

SHV, 19 (61.3%) with bla

TEM and no patients were colonised with either bla

NDM or bla

OXA-48-like (

Figure 1a). Only 6 (19.4%) patients were negative to the above 6 AR genes. Eighteen patients (58%) carried at least one carbapenemase (

Figure 1b).

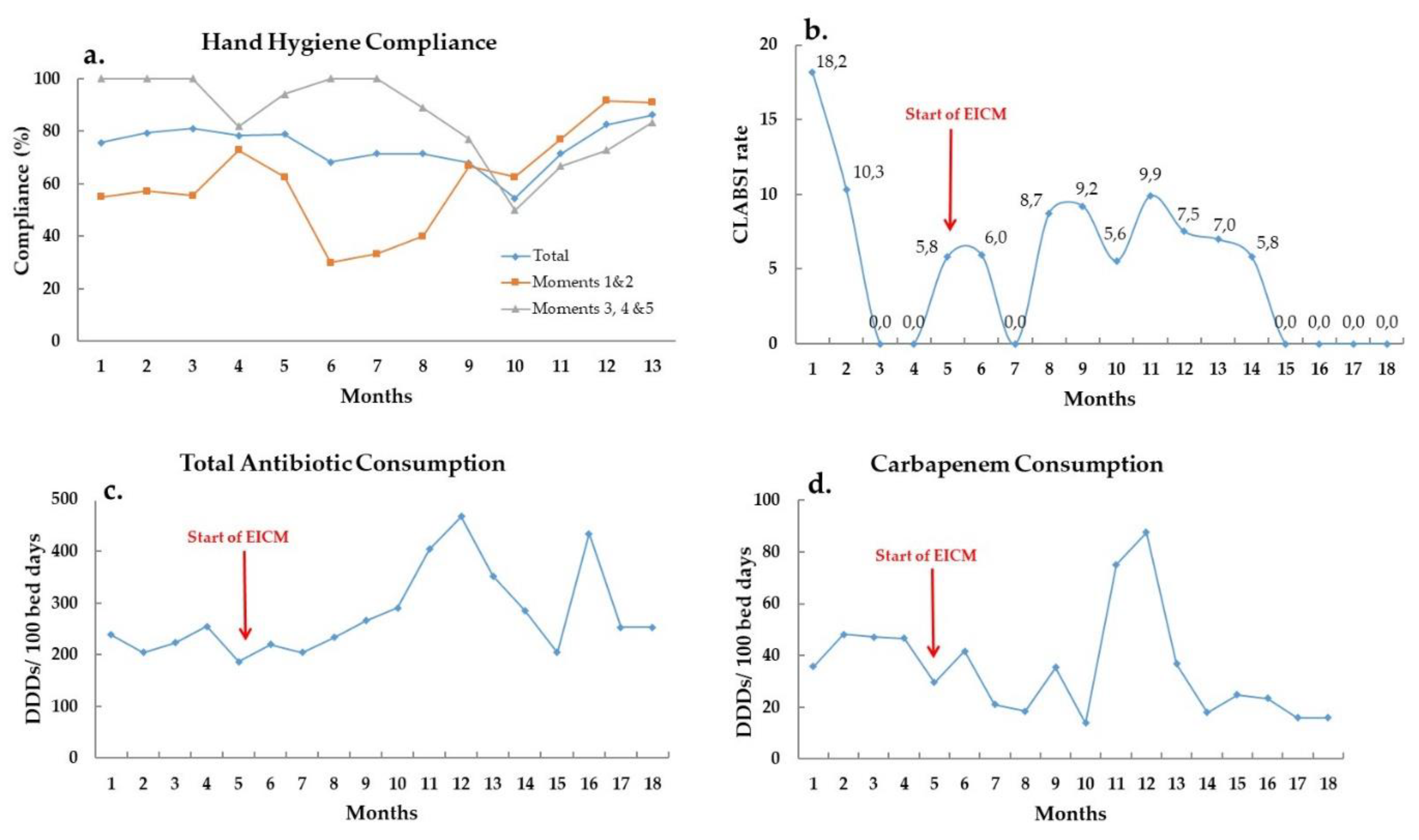

During the Intervention phase, total monthly carbapenem consumption was decreased, despite the fact that total monthly antibiotic consumption showed a small overall increase, and ranged between 13.9 to 87.6 DDDs per 100 bed-days during the study period (

Figure 2c,d).

Hand hygiene compliance was at a moderate level throughout the whole study and fluctuated between 54.5% and 86.2% compliance (

Figure 2a). Hand hygiene before contact with the patient and aseptic procedures improved significantly. Antiseptic solution consumption showed no significant change, but CLABSI rate was decreased and nullified for the last four consecutive months the study period (

Figure 2b). Rectal swabs taken for active surveillance cultures were increased from an average 1.45 to 6.5 per patient, showing more than 4-fold improvement.

During the maintenance period (second targeted molecular screening period), 23 stool samples were collected from 20 patients: 8 (40%) patients were colonized with bla

KPC, 4 (20%) with bla

VIM, 10 (50%) with bla

SHV, 6 (30%) with bla

TEM, 1 (5%) with bla

NDM and no patients were colonised with bla

OXA-48-like (

Figure 1c). Seven (35%) patients were negative to the presence of all 6 targeted genes. Patients carrying at least one carbapenemase were 9 (45%;

Figure 1d).

Comparison of molecular analysis and bacterial cultures showed that during the baseline phase 5 patient samples were found positive for at least one of the AR genes, 3 had no culture taken in the context of the standard of care during their hospitalization and 2 had a culture taken after 2 and 4 months correspondingly, confirming the PCR result. In 14 patients, the direct detection of targeted AR genes in stools and the culture-based phenotypic analysis were in complete agreement, but for 11 patients, differences between the two methods were detected. None of these 11 cases with positive PCR results had also positive cultures. During the maintenance phase, the two methods were in complete agreement for 14 patients, but for the remaining 6 patients, stool samples were found positive for at least one AR gene by the PCR method, but rectal swabs, at the same time period, were found negative for resistance by the culture-based analysis. Four of these patients had positive cultures later, verifying the original positive PCR result, one of them had no other culture taken until discharge and one had a single subsequent culture, which was also found negative.

4. Discussion

In this pilot study, we found that direct implementation of targeted and customized molecular detection of specific AR genes (resistome) is effective tool to promptly recognize the bacterial resistance burden of a high-risk healthcare unit and successfully evaluate the added intervention measures. The molecular approach we used to detect those specific AR genes seems to be superior to the culture-based phenotypic analysis which is commonly used in a clinical setting and in combination with the enhanced and tailored infection control measures had a positive effect on the bacterial resistance burden of a high-risk healthcare unit.

Implementation of active surveillance using a rapid and targeted molecular tool that we developed was successfully conducted, giving the benefit to cohort patients before the development of an infection. Furthermore, the results of the rectal swabs samples, taken in terms of enhanced active surveillance and processed with culture-based phenotypic methods used as a routine method by the hospital, were compared to the results of the culture-independent PCR-based metagenomics analysis used by this study. At many circumstances negative for carbapenem-resistant bacteria cultures were accompanied by positive PCR findings for at least one carbapenemase. This discordant phenomenon may be explained by the higher sensitivity and specificity of PCR methods instead of phenotypic methods, as other studies have shown, too [

6,

7]. In addition, the metagenomic method used in this study allowed us to detect resistance genes present at the level of the microbial community of the stool sample and not only at the level of an organism that was able to grow in culture, which approach becomes increasingly adopted [

8].

Other two important advantages of the molecular surveillance method evaluated in this study are the much shorter time that is needed with obvious benefit to the prompt implementation of infection control measures, and the precise targeting of AR genes included in the bundle of genes searched according to the local AR epidemiology. The result of this AR gene targeting is huge in minimizing the costs for infection control in the hospital. Our previous experience on local epidemiology for AR using both phenotypic and molecular tests was more than helpful to customize AR targets in this study based on their frequency and clinical significance in critically ill children [

9,

10,

11]. This approach may reduce any redudant cost by avoiding inclusion of all available AR genes that may be infrequent or without clinical significance for specific patient popoulations.

The applied EICM led to decreased carriage of bla

KPC, bla

VIM and bla

TEM and increased patients found negative for all 6 targeted AR genes, showing that implementation of EICM may reduce the burden of AR bacteria in this endemic PICU, even in the difficult case of carbapenemase producing Gram-negative bacteria. Previous studies by our group and others have also shown that AR incidence and infection rates diminished or were even eliminated with enhanced infection control measures enforcement [

5,

11,

12,

13].

Reduction of carbapenem consumption may have contributed to the restricted spread of carbapenem resistance genes, as correlation between consumption of carbapenems and the resistance developed to them is highlighted by previous studies [

13,

14].

High levels of hand hygiene compliance, which is also confirmed by the reduced CLABSI rate, is one more contributing factor for decreased colonization. The importance of hand hygiene in the transmission of antimicrobial resistance is now well documented and that is why global and national organizations are adopting guidelines that are constantly updated as more and more studies focus on this subject [

5,

15].

Direct implementation of a targeted and customized rapid molecular detection assay for searching specific resistance genes of interest according to local epidemiology in clinical samples is an effective and rapid tool to promptly recognize the burden of bacterial resistance and successfully evaluate the added intervention measures.

Author Contributions

A.G. (Athina Giampani) was involved in data curation and writing the original draft of the manuscript. M.Si. (Maria Simitsopoulou) was involved in experimental design and result acquisition, writing the original draft of the manuscript, final editing and formatting. M.Sd. (Maria Sdougka) was involved in sample and medical record data collection. E.R. (Emmanuel Roilides) was involved in funding acquisition and final editing and formatting of the manuscript. E.I. (Elias Iosifidis) was involved in project administration, supervision and reviewing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was supported by Procter & Gamble and Gilead Sciences and by the Department of Biology of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Committee of Clinical Studies, Scientific Board of Hippokration General Hospital of Thessaloniki (Approval Code: 1st issue/14-1-2021; Approval Date: 14 Jan 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived from subjects enrolled in the study since the stool samples were taken routinely according to the hospital policy in the PICU.

Data Availability Statement

We confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the dedication of the PICU medical and nursing stuff to providing us with the stool samples and we thank the Microbiology Department of Hippokration Hospital for sharing microbiology data.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to declare related to this manuscript.

References

- Ventola, CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: causes and threats. P & T journal. 2015, 40, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central]

- Barmpouni M, Gordon JP, Miller RL, et al. Clinical and Economic Value of Reducing Antimicrobial Resistance in the Management of Hospital-Acquired Infections with Limited Treatment Options in Greece. Infect Dis Ther. 2023, 12, 1891–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romandini A, Pani A, Schenardi PA, Pattarino GAC, De Giacomo C, Scaglione F. Antibiotic Resistance in Pediatric Infections: Global Emerging Threats, Predicting the Near Future. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021, 10, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990-2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet. 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magiorakos AP, Burns K, Rodríguez Baño J, et al. Infection prevention and control measures and tools for the prevention of entry of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae into healthcare settings: Guidance from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schechner V, Straus-Robinson K, Schwartz D, et al. Evaluation of PCR-based testing for surveillance of KPC-producing carbapenem-resistant members of the Enterobacteriaceae family. J Clin Microbiol. 2009, 47, 3261–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La M van, Lee B, Hong BZM, et al. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of colistin-resistance gene (mcr-1) positive Enterobacteriaceae in stool specimens of patients attending a tertiary care hospital in Singapore. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2019, 85, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofts TS, Gasparrini AJ, Dantas G. Next-generation approaches to understand and combat the antibiotic resistome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017, 15, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karampatakis T, Antachopoulos C, Tsakris A, Roilides E. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Greece: an extended review (2000-2015). Future Microbiol. 2017, 12, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karampatakis T, Tsergouli K, Politi L, et al. Polyclonal predominance of concurrently producing OXA-23 and OXA-58 carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains in a pediatric intensive care unit. Mol Biol Rep. 2019, 46, 3497–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampatakis T, Tsergouli K, Iosifidis E, et al. Effects of an Active Surveillance Program and Enhanced Infection Control Measures on Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacterial Carriage and Infections in Pediatric Intensive Care. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2019, 25, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herruzo R, Ruiz G, Perez-Blanco V, et al. Bla-OXA48 gene microorganisms outbreak, in a tertiary Children’s Hospital, over 3 years (2012-2014). Medicine (United States). [CrossRef]

- Yang P, Chen Y, Jiang S, Shen P, Lu X, Xiao Y. Association between antibiotic consumption and the rate of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria from China based on 153 tertiary hospitals data in 2014. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. [CrossRef]

- Renk H, Sarmisak E, Spott C, Kumpf M, Hofbeck M, Hölzl F. Antibiotic stewardship in the PICU: Impact of ward rounds led by paediatric infectious diseases specialists on antibiotic consumption. Sci Rep. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Evidence of Hand Hygiene as the Building Block for Infection Prevention and Control. 2017. Available online: http://apps.who.int/bookorders (accessed on 20 July 2020).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).