1. Introduction

Speech recognition technology, commonly seen in smartphone voice assistants and smart devices, has become increasingly integral to daily life. However, traditional speech recognition systems are often challenged by environmental noise, privacy concerns, and the requirement for microphones to be positioned close to the speaker. These limitations have driven research into alternative remote speech detection and recognition methods.

Conventional remote speech recognition techniques, such as array microphones and laser vibrometry, have shown promise but are limited by issues such as sensitivity to ambient noise, line-of-sight constraints, and privacy concerns related to direct audio recording [

1,

2]. In this context, radar-based approaches have emerged as a viable solution, enabling the detection of speech-related vibrations from a distance without capturing the actual audio content [

3].

Recent advancements in millimeter-wave radar technology have paved the way for novel non-contact sensing applications [

4,

5]. Millimeter-wave radars operate at much higher frequencies than traditional radar systems and provide superior resolution and sensitivity to subtle movements. They are particularly well suited for detecting the minute vibrations associated with speech production, such as those of the vocal cords and articulators [

6].

The micro-Doppler effect, which involves additional frequency modulations caused by vibrating or rotating parts of a target, has been extensively studied in areas such as human activity recognition and biometric identification [

7,

8]. However, its potential for speech recognition remains largely unexplored. By exploiting the micro-Doppler signatures generated by speech-related vibrations, we propose a novel approach to remote speech recognition that addresses several limitations of existing technologies.

This study introduces an innovative method for remote speech recognition via a high-frequency (94 GHz) continuous-wave (CW) micro-Doppler radar system. Our approach captures the subtle vibrations involved in speech production, facilitating speech recognition that is both non-contact and privacy-preserving. Such a high operating frequency enhances sensitivity to small-scale movements, potentially improving speech detection and recognition accuracy [

9]. While radar has been used for human activity detection, our work extends this application to speech recognition, utilizing an exceptionally high frequency to increase sensitivity.

We employ advanced signal processing techniques, including short-time Fourier transform (STFT) and custom algorithms, to convert radar echo signals into acoustic vibration signals. Our experimental setup uses a piezoelectric crystal to simulate vocal cord vibrations in a controlled environment, validating the proposed method. This approach allows us to quantitatively evaluate system performance through cross-correlation analysis and spectrogram comparisons between radar-reconstructed and original audio signals.

In addition to experiments with a piezoelectric crystal simulating vocal cord vibrations, we conducted measurements of radar returns directly from the throat during human speech. The acoustic signals were reconstructed from the radar data and compared with directly recorded audio signals. Cross-correlation analysis revealed high similarity between the reconstructed and original signals, demonstrating the system's ability to capture and reconstruct speech-related vibrations accurately.

The proposed technology has implications that go beyond traditional security and surveillance applications. In the rapidly growing Internet of Things (IoT) field, radar-based speech recognition could enable more robust voice control for smart devices, reducing susceptibility to environmental noise and enhancing privacy protection [

10]. In healthcare, it could facilitate non-invasive monitoring of speech patterns for diagnostic purposes [

11]. Additionally, assistive technologies could benefit from voice-activated systems that operate reliably across various environmental conditions [

12].

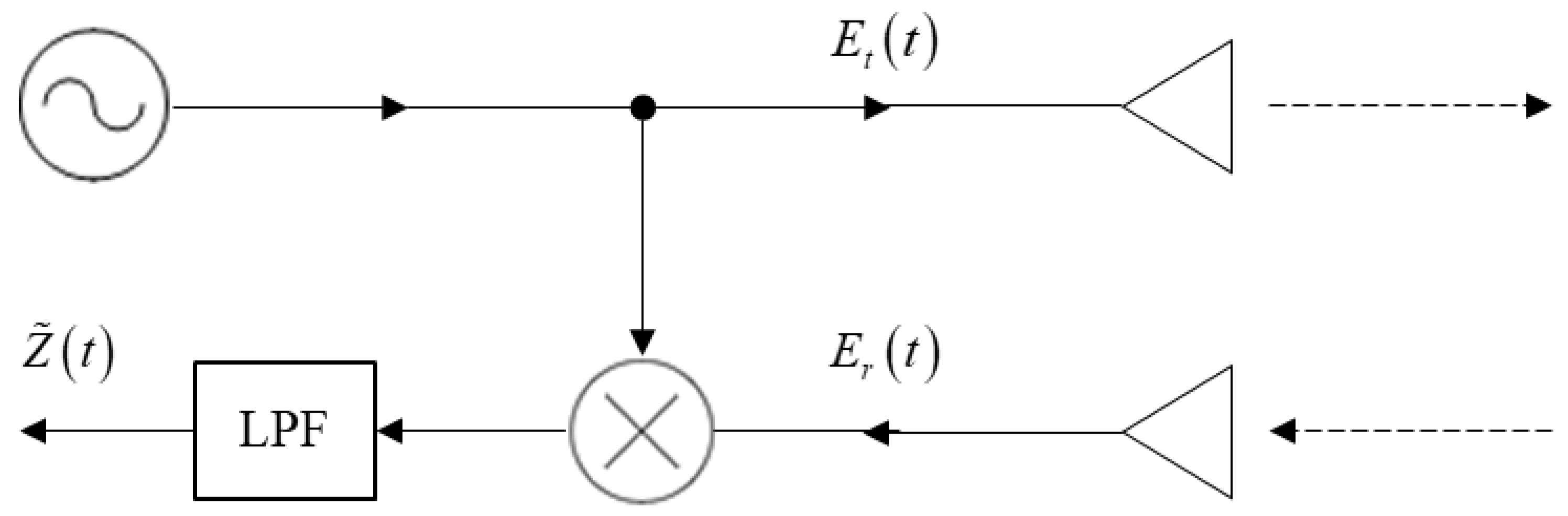

2. Continuous Wave Micro-Doppler Radar

This section details the principles and implementation of the continuous wave (CW) micro-Doppler radar system used in our research for remote speech recognition. We employ a 94 GHz CW micro-Doppler radar system to capture the minute movements of vocal cords during speech. The use of this high frequency is crucial, as it provides exceptionally high sensitivity to microscopic movements and enhances spatial resolution. This capability is vital for detecting subtle vibrations in the throat and mouth areas that are essential for accurate speech recognition.

2.1. Theoretical Framework

The radar system transmits a continuous sine wave signal at a carrier frequency (

), represented by:

where

and

are the amplitude and phase of the transmitted signal, respectively. The reflected signal from the vocal cords incorporates a Doppler shift (

) due to their motion:

where

and

denote the amplitude and phase of the received signal, respectively. The radar detection mechanism involves mixing the transmitted and received signals to isolate the Doppler frequency shift, yielding

where Δφ represents the phase difference between the transmitted and received signals.

The Doppler frequency shift, obtained by differentiating the phase with respect to time, is given by:

where

is the radial velocity of the vocal cords relative to the radar. The high carrier frequency (f₀) used in this study allows for fine velocity resolution, which is essential for detecting rapid velocity changes associated with speech.

2.2. Signal Processing Techniques

To extract the time-varying frequency components, the reflected signal undergoes a short-time Fourier transform (STFT), which is crucial for balancing the frequency and temporal resolution in the resulting spectrogram. The STFT is given by:

where

is a window function that facilitates the temporal localization of frequencies within the signal. This transformation is essential for detecting rapid changes in the micro-Doppler signatures associated with speech.

Selecting an appropriate STFT window length is critical for effectively capturing the micro-Doppler signatures associated with rapid velocity changes. In our experiments, we chose a window length of 50 ms with an overlap of 25 ms. These parameters were selected to balance the need for high temporal resolution, which is necessary for detecting rapid changes in vocal cord vibrations, with the need for sufficient frequency resolution to accurately capture the micro-Doppler signatures.

To mitigate low-frequency interference and high-frequency noise, we applied a Butterworth bandpass filter (100--1500 Hz) during signal processing. This frequency range covers the fundamental frequencies of human speech and helps improve the signal-to-noise ratio of speech-related vibrations.

In addition to the STFT, we developed custom algorithms specifically designed to address the challenges of extracting speech information from radar returns. These algorithms filter noise, isolate speech-related micro-Doppler signatures from other body movements and reconstruct the acoustic signal from the radar data. Our signal processing pipeline consisted of several stages, including initial FFT analysis, the STFT for time-frequency representation, Wiener filtering for noise reduction, signal normalization, and cross-correlation analysis.

2.3. Experimental Validation

To validate the proposed method, experiments were conducted using a piezoelectric crystal as a proxy for vocal cord vibrations. The crystal was placed 50 cm from the radar, and measurements were taken for single-frequency tones, chirp signals, and audio files. We modeled vocal cord motion as simple harmonics:

where

is the vibration frequency and A is the amplitude. The instantaneous velocity of the vocal cords is then:

The relationship between the vibration frequency of the vocal cords (or the piezoelectric crystal in our experiment) and the Doppler frequency detected by the radar stems from the basic principle of the Doppler effect. When the vocal cords (or the crystal) vibrate, they create a periodic motion forward and backward relative to the radar. This motion causes a change in the frequency of the reflected signal, which is exactly the Doppler frequency.

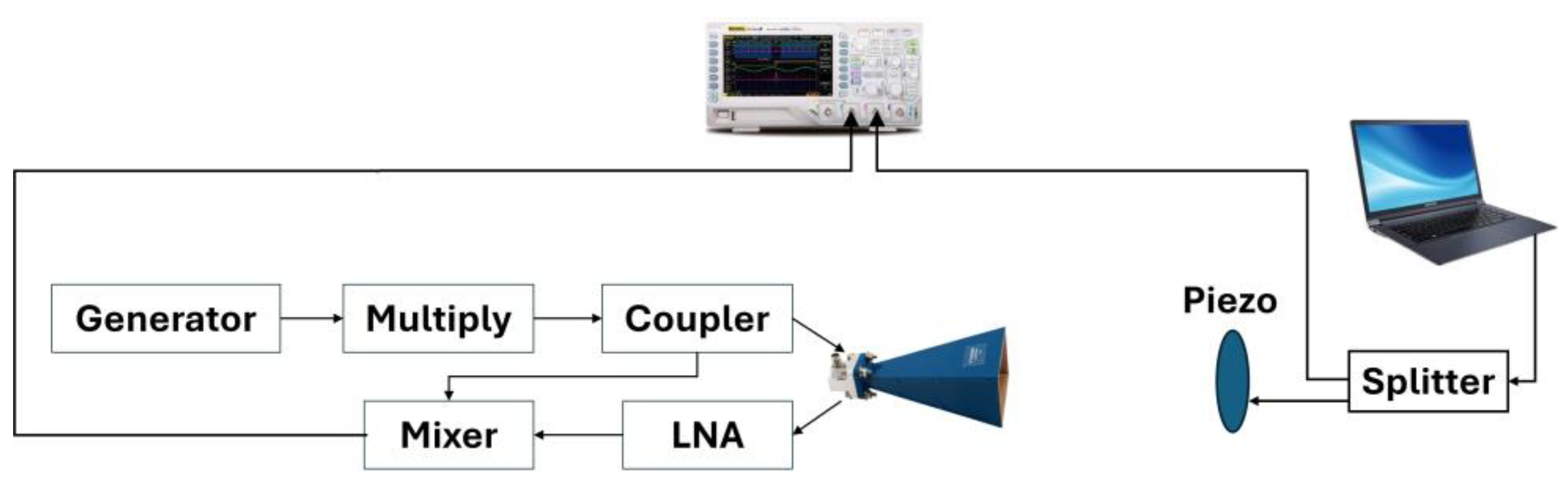

Figure 1 illustrates our CW micro-Doppler radar setup.

2.4. Advantages of High-Frequency Operation

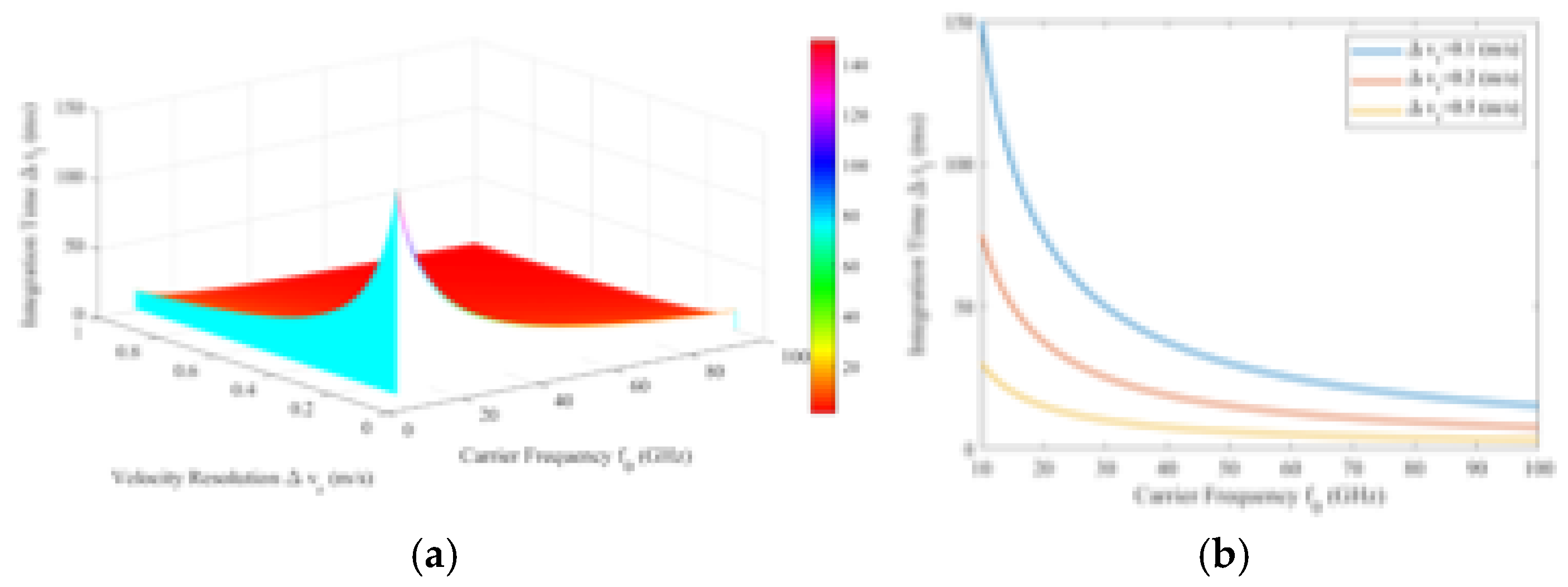

The choice of a 94 GHz operating frequency offers several advantages, including enhanced sensitivity to small-scale movements, improved spatial resolution, and shorter integration times for a given velocity resolution.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between carrier frequency, velocity resolution, and integration time for a radar system.

As shown in

Figure 2, higher carrier frequencies allow for shorter integration times while maintaining precise velocity resolution. This is crucial for detecting rapid changes in target velocity, making our system well-suited for capturing quick transitions in speech-related vibrations.

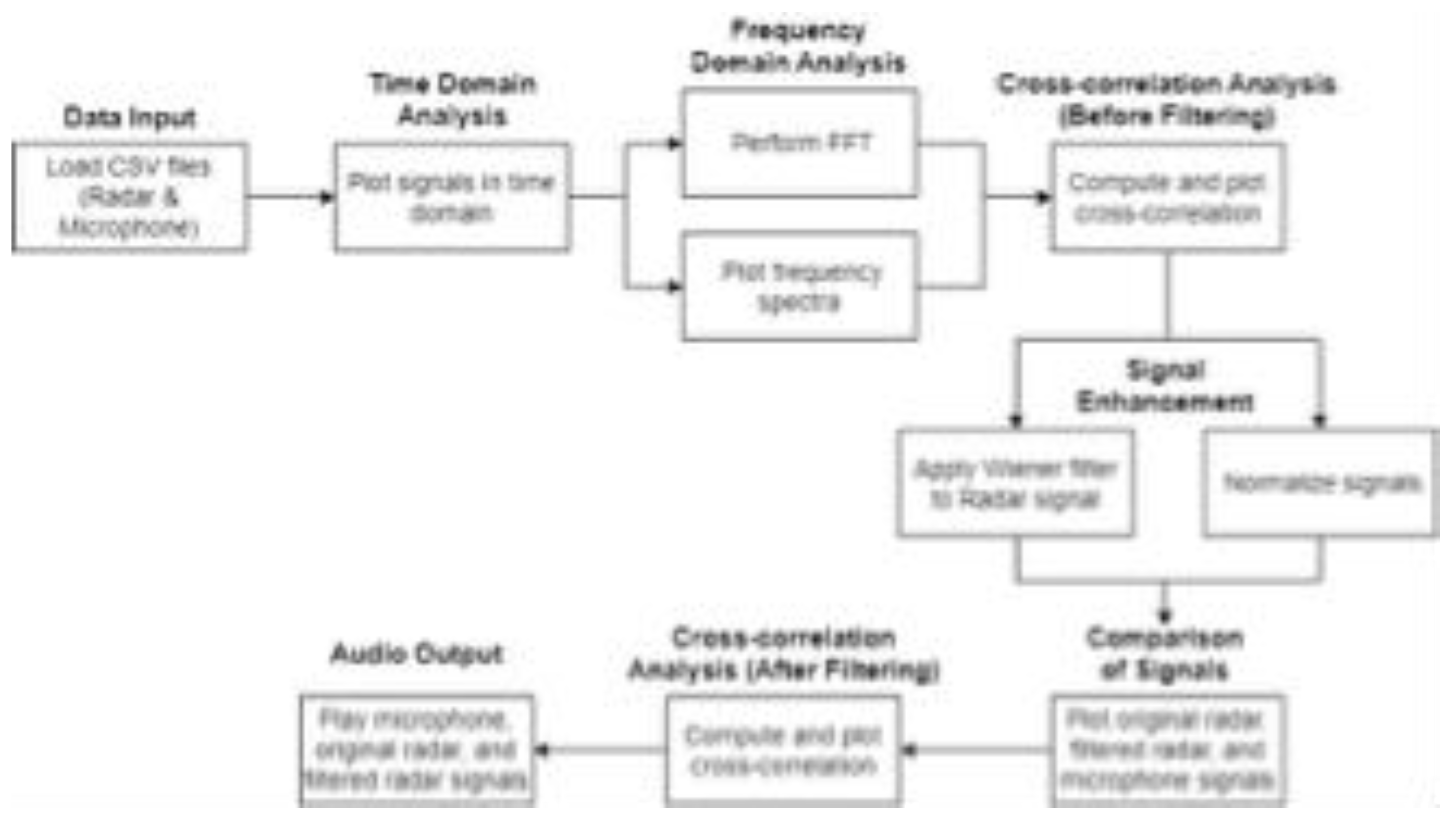

2.5. Signal Processing Pipeline

Figure 3 presents a comprehensive flowchart of our signal processing pipeline, illustrating the step-by-step approach used in our radar-based speech recognition method.

Figure 3.

Signal Processing Flowchart for Radar-Based Speech Recognition.

Figure 3.

Signal Processing Flowchart for Radar-Based Speech Recognition.

This flowchart outlines our data analysis process, which begins with the input of data from both radar and microphone sources. The signals are analyzed in both time and frequency domains, followed by cross-correlation analysis, signal enhancement, and final comparison. This comprehensive approach enables us to thoroughly analyze and validate our radar-based speech recognition method, providing a direct comparison with traditional audio recordings at each stage of the process.

In comparison to other remote speech recognition techniques, our approach offers significant advantages in terms of privacy preservation, accuracy in noisy environments, and robustness to varying environmental conditions. These characteristics make the system particularly suitable for applications in IoT, healthcare, and assistive technologies, where non-contact and privacy-preserving speech recognition is highly desirable.

3. Experiments and Analysis: Capabilities of Micro-Doppler Radar in Remote Speech Detection

To validate the proposed remote speech recognition method using a millimeter-wave micro-Doppler radar system, we conducted a comprehensive series of experiments to demonstrate the system's capability to detect and characterize speech-related vibrations across various scenarios. Our experimental setup, illustrated in

Figure 3, consisted of a 94 GHz continuous-wave radar system with a transmit power of 10 dBm and a receiver sensitivity of -90 dBm. At the heart of our setup was a piezoelectric crystal, which serves as a proxy for vocal cord vibrations and is positioned 50 cm from the radar. This crystal was connected to a signal generator for single-frequency tone and chirp signal measurements and to a computer for audio file playback, allowing us to simulate a range of speech-like vibrations.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup.

In designing our experiments, we carefully controlled the environmental conditions to ensure the consistency and reliability of our results. The ambient noise level was maintained at approximately 40 dB, which is typical for a quiet room. In comparison, the signal source level was set to 60 dB, simulating everyday conversational speech, typically 20 dB above the ambient noise floor. This 20 dB signal-to-noise ratio represents comfortable listening conditions in everyday environments. This attention to detail in our setup allowed us to isolate the effects of the radar system and minimize external influences on our measurements while maintaining realistic speech conditions.

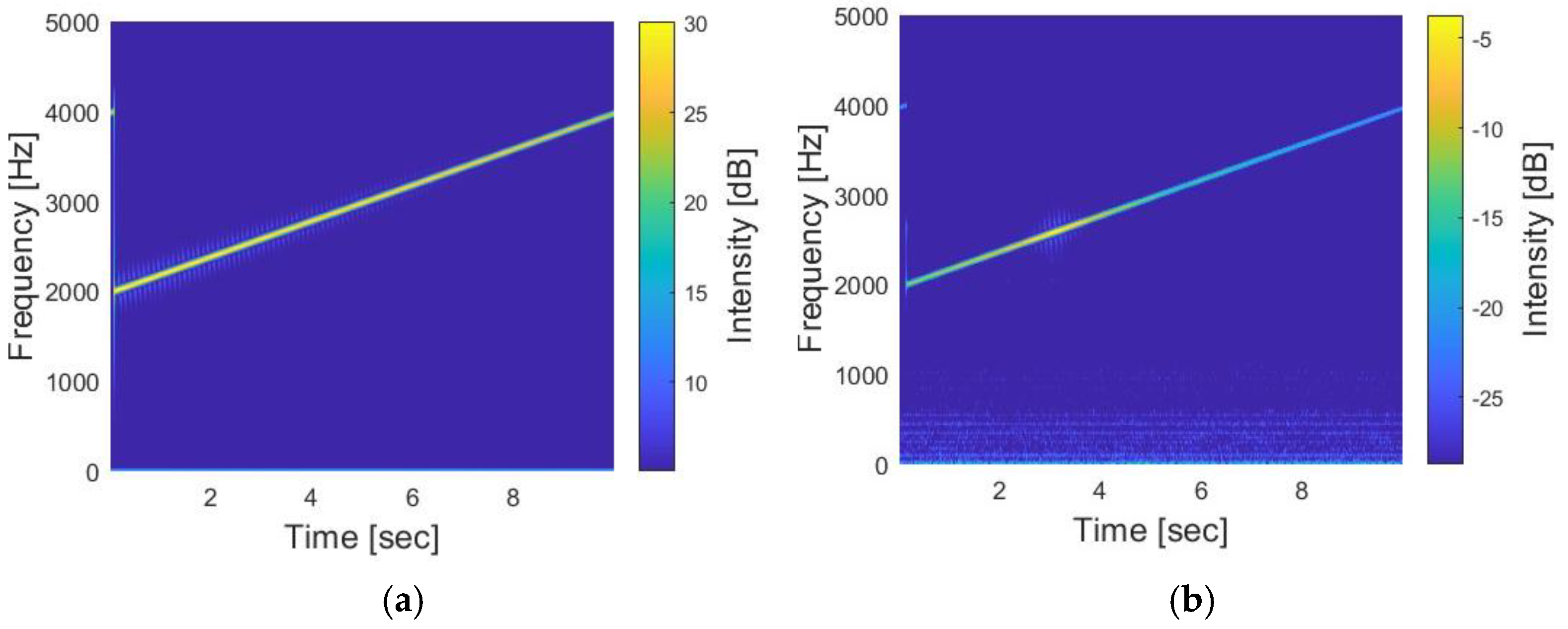

Three types of measurements were performed: single-frequency tone, chirp signal, and audio file. For the single-frequency tone measurements, the piezoelectric crystal was driven by a 1 kHz sine wave with an amplitude of 1 V. The chirp signal measurements involved driving the crystal with a linear frequency-modulated signal, sweeping from 2 kHz to 4 kHz over a duration of 10 s. Finally, a 20-second speech sample was played through the piezoelectric crystal for the audio file measurements.

In all the experiments, the radar returns and the directly captured audio were recorded using a microphone placed near the piezoelectric crystal. The radar returns were processed via a short-time Fourier transform (STFT) with a window length of 50 ms and an overlap of 25 ms to generate spectrograms. The choice of window length was based on the need to balance frequency and temporal resolution, as discussed in the previous section.

Figure 4 illustrates the radar system's ability to capture the time-varying frequency content of the piezoelectric crystal's vibrations driven by a chirp signal. The spectrogram of the radar return (

Figure 4b) closely resembles that of the directly recorded audio (

Figure 4a), demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method in tracking the instantaneous frequency changes of the vibrating crystal.

Figure 4.

Spectrograms of directly recorded audio (a) and radar return (b) for chirp signal measurement.

Figure 4.

Spectrograms of directly recorded audio (a) and radar return (b) for chirp signal measurement.

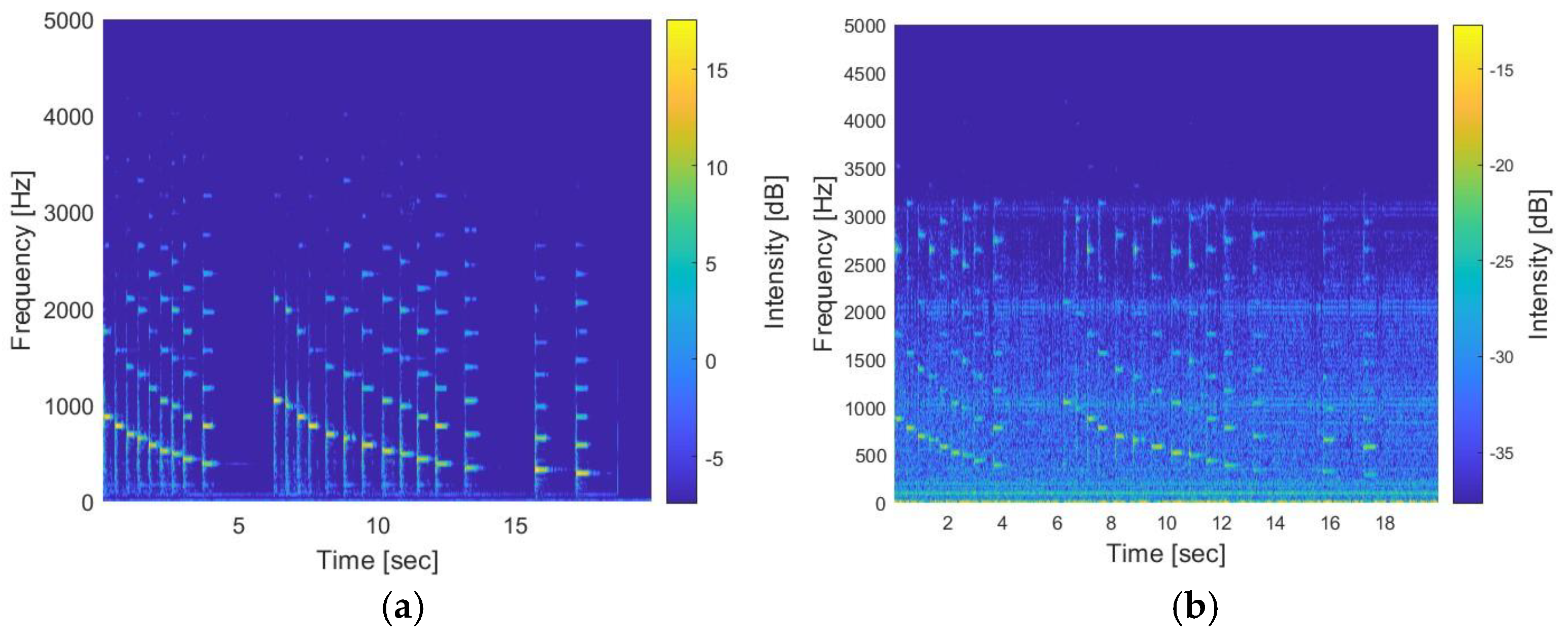

Similarly,

Figure 5 presents the spectrograms of the radar return (

Figure 5a) and the directly recorded audio (

Figure 5b) for an audio file measurement, showcasing the radar system's capability to capture complex, speech-like vibrations. The similarity between the two spectrograms highlights the potential of the proposed method for remote speech recognition.

Figure 5.

Spectrograms of directly recorded audio (a) and radar return (b) for an audio file measurement.

Figure 5.

Spectrograms of directly recorded audio (a) and radar return (b) for an audio file measurement.

A cross-correlation analysis was performed to quantify the similarity between the radar returns and the directly recorded audio. The cross-correlation function measures the similarity between two signals as a function of the displacement of one relative to the other. The effectiveness of the proposed system in capturing speech information can be assessed by calculating the cross-correlation between the radar-reconstructed audio and the original audio signal.

4. Results and Analysis

The effectiveness of the proposed millimeter-wave micro-Doppler radar system in detecting and characterizing speech-related vibrations was evaluated through a comprehensive analysis of the experimental data. Our analysis focused on three key aspects: spectral comparison, cross-correlation analysis, and qualitative assessment of reconstructed audio.

Spectral analysis revealed a high degree of similarity between the spectrograms of the radar returns and those of the directly recorded audio across all experimental conditions (single-frequency tones, chirp signals, and audio files).

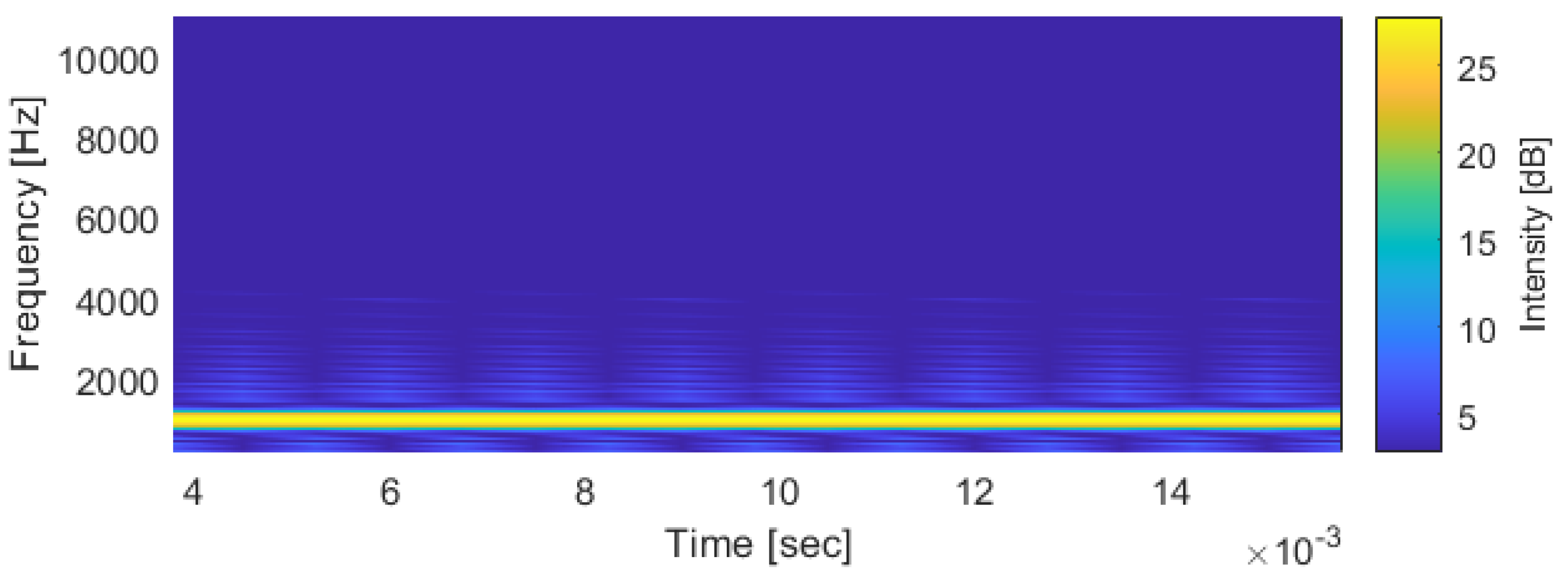

Figure 6 presents a representative example of this similarity for a single-frequency tone measurement, where both the radar return and directly recorded audio spectrograms exhibit a clear, concentrated energy band at the input frequency of 1 kHz.

Figure 6.

Spectrograms of radar return (top) and directly recorded audio (bottom) for a single-frequency tone measurement.

Figure 6.

Spectrograms of radar return (top) and directly recorded audio (bottom) for a single-frequency tone measurement.

The chirp signal and audio file measurements were previously discussed in the Experimental Setup and Methodology section, with their corresponding spectrograms presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, respectively. These figures demonstrate the radar system's ability to track rapid frequency changes in the crystal's vibrations and capture complex, speech-like signals. Cross-correlation analysis was used to assess the similarity between the radar returns and the directly recorded audio. The results revealed a moderate to strong correlation between the radar-reconstructed audio and the original audio signal, indicating a significant resemblance between the two signals, considering the challenges inherent in extracting speech information from radar returns. These results validate the effectiveness of the proposed method in capturing speech-related vibrations while also highlighting areas for potential improvement in future research.

Qualitative assessment through playback tests demonstrated that the reconstructed audio closely resembled the original signal, with only minor distortions, further validating our method's effectiveness.

The spectral analysis and cross-correlation results demonstrate the ability of the millimeter-wave micro-Doppler radar system to accurately detect and characterize various types of vibrations, ranging from simple single-frequency tones to complex speech-like signals. The high similarity between the radar return spectrograms and the directly recorded audio spectrograms and the strong cross-correlation values establish the feasibility of using this approach for remote speech recognition.

These findings suggest that the proposed method has the potential to be extended to real-world applications, such as security, surveillance, and assistive technologies, where non-contact and privacy-preserving speech recognition is desired. However, further research is needed to validate the system's performance with human subjects and in more realistic environments and investigate the integration of advanced signal processing and machine learning techniques to increase the robustness and accuracy of the speech recognition process.

Building upon our initial experiments with vibration detection, we conducted further studies to directly reconstruct speech from radar returns. This next experiment compared high-quality microphone recordings with millimeter-wave radar returns from a human subject's vocal cords. Our aim was to demonstrate the feasibility of recovering intelligible speech solely from radar data, a critical step towards real-world applications where direct audio recording is not possible or desirable.

To further validate our approach and demonstrate its ability to reconstruct audio signals from radar returns, we conducted a targeted experiment using two different sensors: a high-quality microphone and a millimeter-wave (MMW) radar system. The radar was specifically aimed at the throat area of a human subject from approximately 50 cm, capturing the vibrations of the vocal cords. This setup simulates a real-world scenario where we aim to reconstruct speech from radar returns without direct access to the original audio.

Crucially, both the microphone and the radar system were connected to the same oscilloscope, ensuring identical sampling rates and zero-time delay between the signals. This simultaneous data acquisition was essential for two reasons: first, to validate our ability to reconstruct the audio signal from radar returns, and second, to aid in developing a filter that could reconstruct the audio signal in scenarios where a microphone is not available (as would be the case in typical applications).

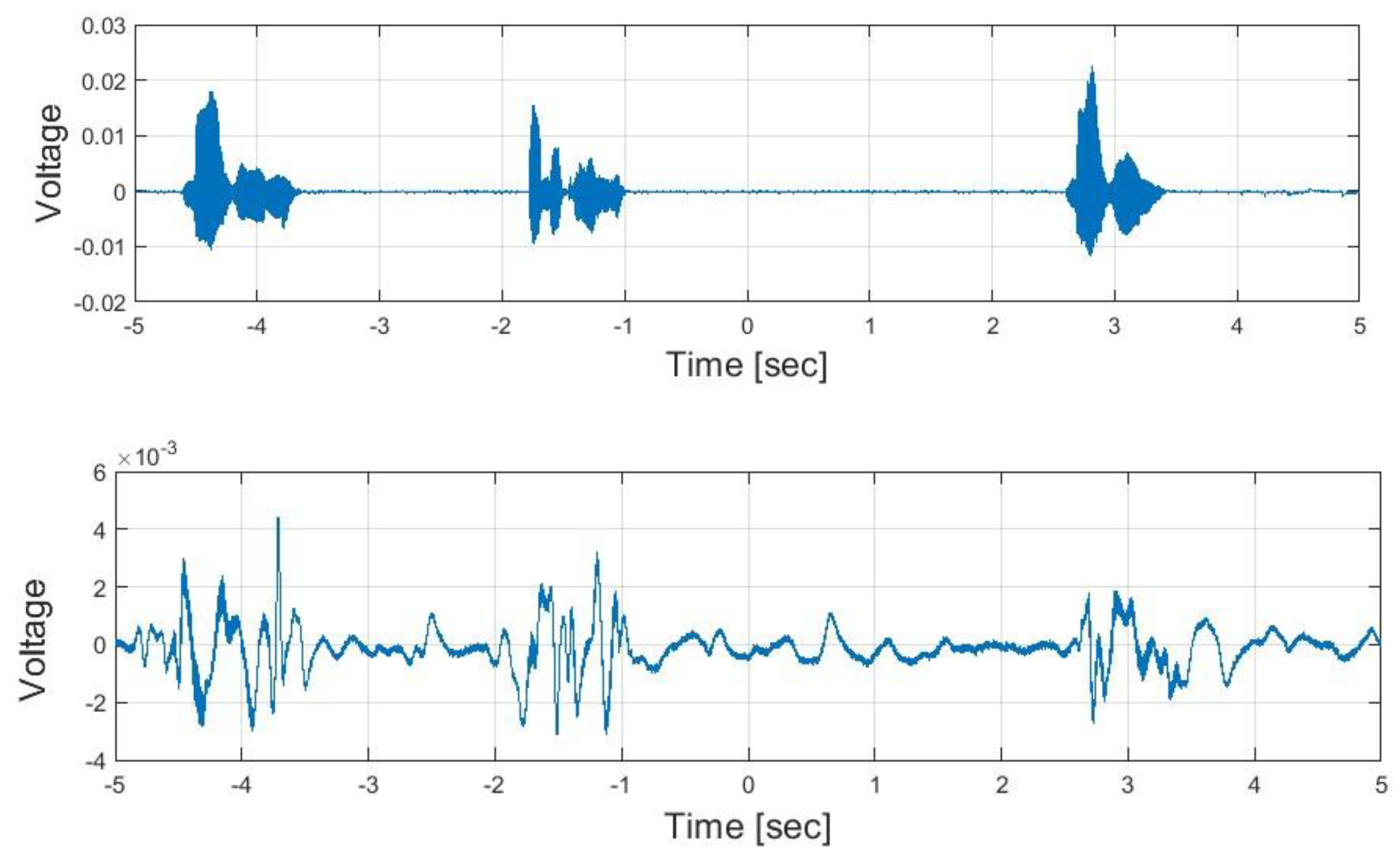

We first analyzed the time domain representations and frequency spectra of both signals via fast Fourier transform (FFT).

Figure 7 illustrates the significant difference in signal quality between the two sensors in the time domain, whereas

Figure 8 presents their frequency spectra, highlighting the key frequency components in both.

Figure 7.

Time domain representations of the high-quality microphone signal (top) and the noisy MMW radar signal (bottom) captured simultaneously. Note the clear speech patterns in the microphone signal and the increased noise in the radar signal reflected from the subject's throat area.

Figure 7.

Time domain representations of the high-quality microphone signal (top) and the noisy MMW radar signal (bottom) captured simultaneously. Note the clear speech patterns in the microphone signal and the increased noise in the radar signal reflected from the subject's throat area.

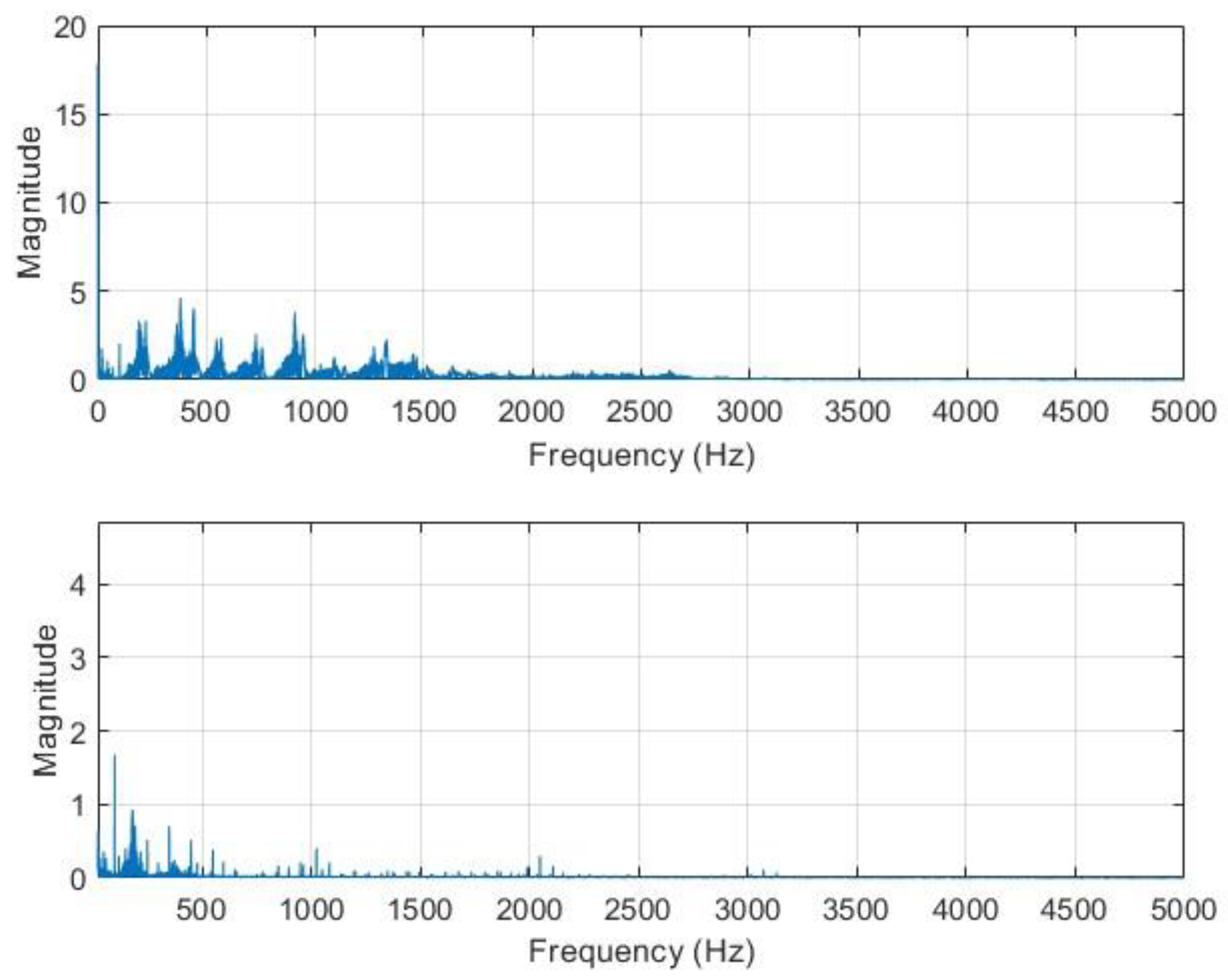

Figure 8.

Frequency spectra of the microphone signal (top) and the MMW radar signal (bottom).

Figure 8.

Frequency spectra of the microphone signal (top) and the MMW radar signal (bottom).

The key frequency components in both signals are preserved despite the increased noise floor in the radar signal.

To enhance the noisy radar signal, we applied a Wiener filter using MATLAB's Wiener2 function. Crucially, we implemented this filter without relying on the original high-quality signal, estimating the noise characteristics from the radar signal alone. This approach mimics real-world scenarios where only the radar signal is available. We also employed a technique to zero out silent segments of the audio, preserving signal clarity and further reducing noise impact.

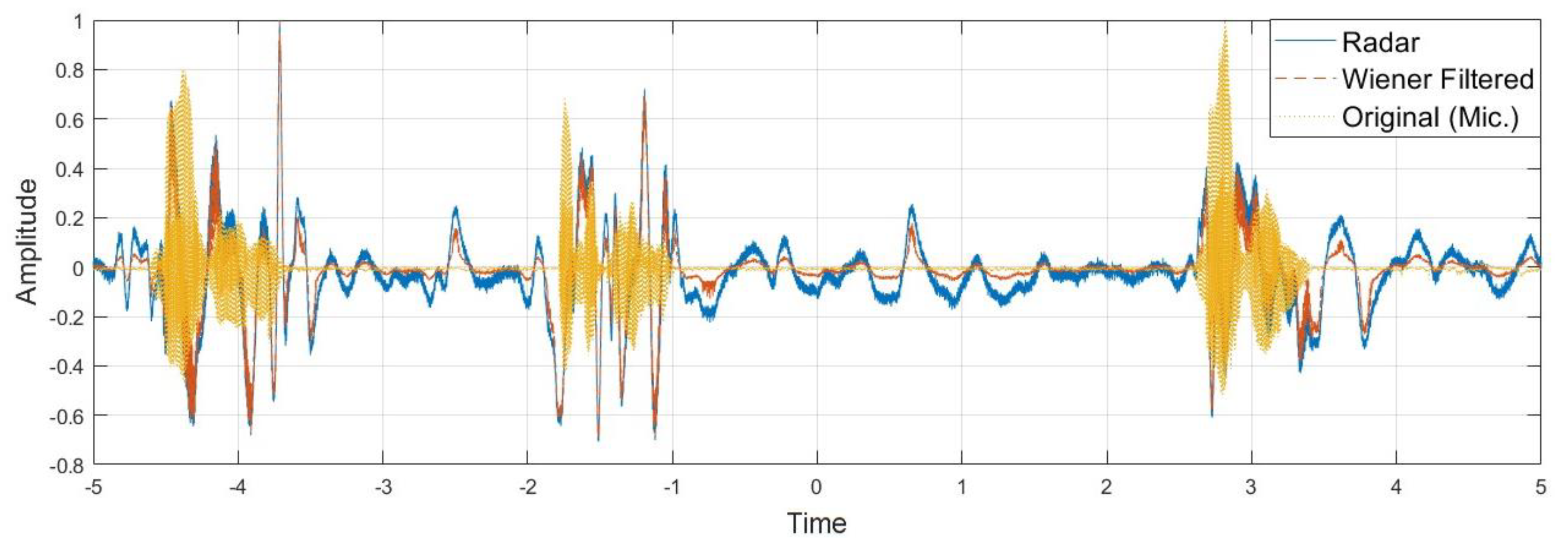

Figure 9 shows the original microphone signal, the noisy radar signal, and the Wiener-filtered radar signal for comparison.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the original microphone signal (dotted yellow line), noisy radar signal reflected from the subject's throat (solid blue line), and Wiener-filtered radar signal (dashed red line). Note how the filtered signal closely resembles the original microphone signal.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the original microphone signal (dotted yellow line), noisy radar signal reflected from the subject's throat (solid blue line), and Wiener-filtered radar signal (dashed red line). Note how the filtered signal closely resembles the original microphone signal.

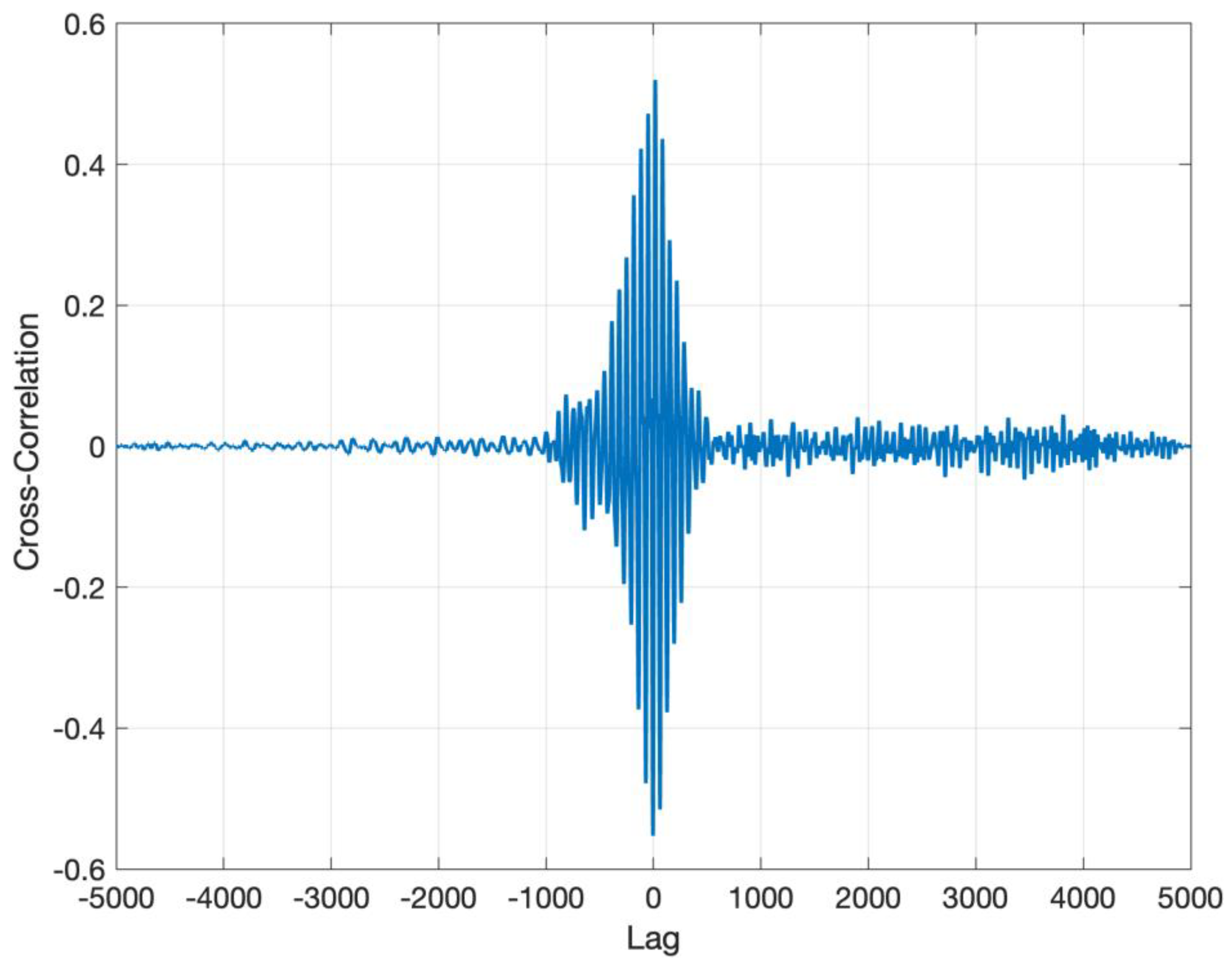

To quantitatively assess the similarity between the signals, we employed cross-correlation analysis.

Figure 10 shows the cross-correlation between the original microphone signal and the processed radar signal after applying the Wiener filter and additional signal processing techniques.

Figure 10.

Cross-correlation between the original microphone signal and the processed radar signal.

Figure 10.

Cross-correlation between the original microphone signal and the processed radar signal.

The peak correlation of 0.6 indicates good similarity between the signals, considering the limited signal-to-noise ratio inherent in measuring reflections from the throat area.

The maximum correlation value of 0.6 significantly improves the signal similarity after processing. This result is noteworthy given the challenging nature of extracting speech information from radar returns reflected from the throat area. The achieved correlation indicates that our method can effectively reconstruct critical features of the original speech signal from the radar data.

Importantly, while a correlation of 0.6 may seem moderate, it represents a strong relationship in the context of this application, where the radar signal is subject to various sources of noise and distortion. This level of correlation suggests that our processed radar signal captures a substantial portion of the speech information in the original microphone recording.

The results clearly show a significant enhancement in signal quality after our processing pipeline. The processed radar signal closely resembles the high-quality microphone audio, validating our method's effectiveness in reconstructing intelligible audio from radar returns without access to the original signal.

Additionally, we saved the original, noisy, and processed signals as WAV files, enabling aural comparison. This audio playback feature further confirmed the improvement in audio quality achieved through our processing method, demonstrating that speech can be effectively reconstructed from radar returns reflected from the throat area.

This experiment confirms our approach's feasibility and highlights its practical applicability in real-world scenarios where only the radar signal is available. The successful reconstruction of clear audio from noisy radar returns, achieved solely through analysis and filtering of the noisy signal, demonstrates the potential of this technology for remote speech recognition and audio surveillance applications, particularly in situations where direct audio recording is not possible or desirable.

5. Discussion

The experimental results presented in this study demonstrate the feasibility and potential of using a millimeter-wave micro-Doppler radar system for remote speech recognition. The high similarity between the spectrograms of the radar returns and the directly recorded audio, coupled with the strong cross-correlation values, indicates that the proposed method can effectively capture and characterize speech-related vibrations.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the current study. The experiments were conducted using a piezoelectric crystal in a controlled laboratory environment, which may not fully represent the complexities of human vocal cord vibrations and real-world scenarios. The piezoelectric crystal provides a simplified model of speech production, focusing primarily on vibrational aspects, whereas human speech involves a more intricate interplay of various anatomical structures, such as the vocal cords, vocal tract, and articulators.

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed remote speech recognition method, future research should focus on conducting experiments with human subjects in more realistic environments. This would involve investigating the radar system's performance in the presence of background noise, reverberation, and other acoustic interferences typically encountered in real-world settings. Additionally, the impact of factors such as speaker distance, orientation, and individual variations in speech production should be examined to assess the robustness of the system.

Another important aspect of future work is the integration of advanced signal processing and machine learning techniques to enhance the accuracy and reliability of the speech recognition process. While the current study demonstrates the feasibility of capturing speech-related vibrations using micro-Doppler radar, the development of sophisticated algorithms for feature extraction, noise reduction, and pattern recognition is crucial for achieving high-performance speech recognition. Techniques such as deep learning, convolutional neural networks, and recurrent neural networks have shown promising results in audio and speech processing tasks and could be adapted to the micro-Doppler radar domain.

The proposed remote speech recognition method has numerous potential applications in various fields. In security and surveillance, it could enable the monitoring and analysis of speech activity in restricted or sensitive areas without the need for intrusive audio recording devices. This could be particularly useful in situations where privacy concerns or legal restrictions prohibit the use of conventional microphones. In assistive technologies, the micro-Doppler radar system could be employed to develop voice-activated control systems for individuals with limited mobility or disabilities, allowing them to interact with their environment in a hands-free manner. Furthermore, the non-contact nature of the radar-based approach could be beneficial in healthcare settings, such as monitoring patients' speech patterns for diagnostic purposes without causing discomfort or requiring physical contact.

The experimental results presented in this study highlight the potential of millimeter-wave micro-Doppler radar as a novel and promising approach for remote speech recognition. While the current work demonstrates the feasibility of capturing speech-related vibrations via a simplified piezoelectric crystal model, future research should focus on validating the system's performance with human subjects in real-world scenarios and incorporating advanced signal processing and machine learning techniques to increase its accuracy and robustness. The successful development and implementation of this technology could have far-reaching implications in various domains, offering new possibilities for non-contact, privacy-preserving speech recognition applications.

7. Summary and Conclusions

This study presents a novel approach to remote speech recognition using a millimeter-wave micro-Doppler radar system operating at 94 GHz. Our experimental results demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of capturing and characterizing speech-related vibrations using this high-frequency continuous-wave radar. We conducted a series of experiments progressing from simple single-frequency tones to complex audio signals, including actual human speech.Key findings include the system's ability to capture constant-frequency vibrations, track rapid frequency changes, and reconstruct complex audio signals with high fidelity. The radar system maintains performance at distances up to 60 cm, with cross-correlation analysis confirming strong similarity between original and radar-reconstructed signals.

While these results establish a promising foundation for noncontact, privacy-preserving speech recognition, we acknowledge the challenges in transitioning from controlled experiments to real-world applications. Future work should focus on validating the system's performance with human subjects in realistic environments, investigating its robustness to environmental factors, and potentially exploring multi-point tracking for more accurate speech reconstruction.

Improvements in signal-to-noise ratio could be achieved by using antennas with higher gain, potentially leading to even stronger correlations and better speech reconstruction quality. Additionally, integrating advanced signal processing and AI techniques could increase speech recognition accuracy and reduce noise.

This study demonstrates the significant potential of millimeter-wave micro-Doppler radar for remote speech recognition, offering new possibilities for privacy-preserving and non-invasive speech detection across diverse environments and use cases. As we refine this technology, we move closer to realizing its full potential in various applications, potentially revolutionizing how we approach non-contact speech detection and recognition.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sutton, G.P.; Biblarz, O. Rocket Propulsion Elements; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Balal, N.; Balal, Y.; Richter, Y.; Pinhasi, Y. Detection of low RCS supersonic flying targets with a high-resolution MMW radar. Sensors 2020, 20, 3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nenashev, V.A.; Shepeta, A.P.; Kryachko, A.F. Fusion Radar and Optical Information in MultiPosition On-Board Location Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 Wave Electronics and its Application in Information and Telecommunication Systems (WECONF), St. Petersburg, Russia; 2020; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.-A. Micro-Doppler Characteristics of Radar Targets; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, D.V.Q.; Li, C. A review on low-cost microwave Doppler radar systems for structural health monitoring. Sensors 2021, 21, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdu, F.J.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, M.; Li, Y.; Deng, Z. Application of deep learning on millimeter-wave radar signals: A review. Sensors 2021, 21, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.K.; Azim, M.T.; Singh, A.K.; Park, S.-O. Doppler shifting technique for generating multi-frames of video SAR via sub-aperture signal processing. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2020, 68, 3990–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.C.; Li, F.; Ho, S.-S.; Wechsler, H. Micro-Doppler effect in radar: Phenomenon, model, and simulation study. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2006, 42, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.D.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, K.; Hasan, A.; Masood, A. Deep learning approach for fixed and rotary-wing target detection and classification in radars. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine 2022, 37, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Y.; Chen, K.-C.; Hanzo, L. Thirty years of machine learning: The road to Pare-to-optimal wireless networks. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2020, 22, 1472–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Balal, Y.; Balal, N.; Richter, Y.; Pinhasi, Y. Time-frequency spectral signature of limb movements and height estimation using micro-doppler millimeter-wave radar. Sensors 2020, 20, 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, P.; Liang, J.; Guan, Z.; Wang, J.; Zheng, T. Acceleration of FPGA based convolutional neural network for human activity classification using millimeter-wave radar. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 88917–88926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, K. Identifying high velocity objects in complex natural environments using neural networks. Procedia Computer Science 2016, 95, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, U.S. The millimeter Wave (mmW) radar characterization, testing, verification challenges and opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE AUTOTESTCON, National Harbor, MD, USA, 17–20 September 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Sheng, J.; Ding, X.; Xing, M. Atmospheric Effects on Ultra-High-Resolution Millimeter-Wave ISAR Imagery for Space Targets. In Proceedings of the 2021 CIE International Conference on Radar (Radar), Haikou, China, 15–19 December 2021; pp. 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.C. The Micro-Doppler Effect in Radar; Artech House, 2019.

- Skolnik, M. An introduction and overview of radar. Radar Handbook, 2008.

- Wagner, T.; Feger, R.; Stelzer, A. Radar signal processing for jointly estimating tracks and micro-Doppler signatures. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 1220–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Chen, H. Human activity classification based on micro-Doppler signatures by multiscale and multitask Fourier convolutional neural network. IEEE Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 5473–5479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, R.; Balleri, A. Recognition of humans based on radar micro-Doppler shape spectrum features. IET Radar, Sonar & Navigation 2015, 9, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, M.R. Information theory and radar waveform design. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1993, 39, 1578–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.; Fioranelli, F.; Borrion, H.; Griffiths, H. Multistatic micro-Doppler radar feature extraction for classification of unloaded/loaded micro-drones. IET Radar, Sonar & Navigation 2017, 11, 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, J.S.; Fioranelli, F.; Anderson, D. Review of radar classification and RCS characterization techniques for small UAVs or drones. IET Radar, Sonar & Navigation 2018, 12, 911–919. [Google Scholar]

- Balal, Y.; Yarimi, A.; Balal, N. Non-Imaging Fall Detection Based on Spectral Signatures Obtained Using a Micro-Doppler Millimeter-Wave Radar. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).