1. Introduction

Cybercrime poses a serious danger to cybersecurity [

1], and according to [

2], the cost of cybercrime reached 8 trillion dollars in 2023, with malware such as banking malware accounting for a large proportion of this total cost. In recent years, banking malware has emerged as a major concern because malicious actors can make huge profits from these types of malware variants [

3], and the cost to businesses is high. For instance, Emotet banking malware infections can cost up to 1 million dollars per incident to remediate [

4]. Banking malware attacks also continue to rise [

5], and the discovery of new banking malware variants also continues to increase for example, over a thousand variants of the banking malware Godfather were discovered in 2023 alone [

6].

The Zeus banking malware has emerged as one of the most notorious banking malware variants ever developed [

7] and since the release of the Zeus source code, many additional variants of Zeus have been developed and emerged and these include Ramnit, ZeusPanda and Ramnit [

8].

1.1. Need for Detecting Banking Malware

New malware variants are always being discovered and are becoming more sophisticated in the way they attack systems [

9], and they will continue to increase [

10]. Banking malware follows the same trajectory, and, in this category, Zeus and its variants are still the most prevalent. For example,

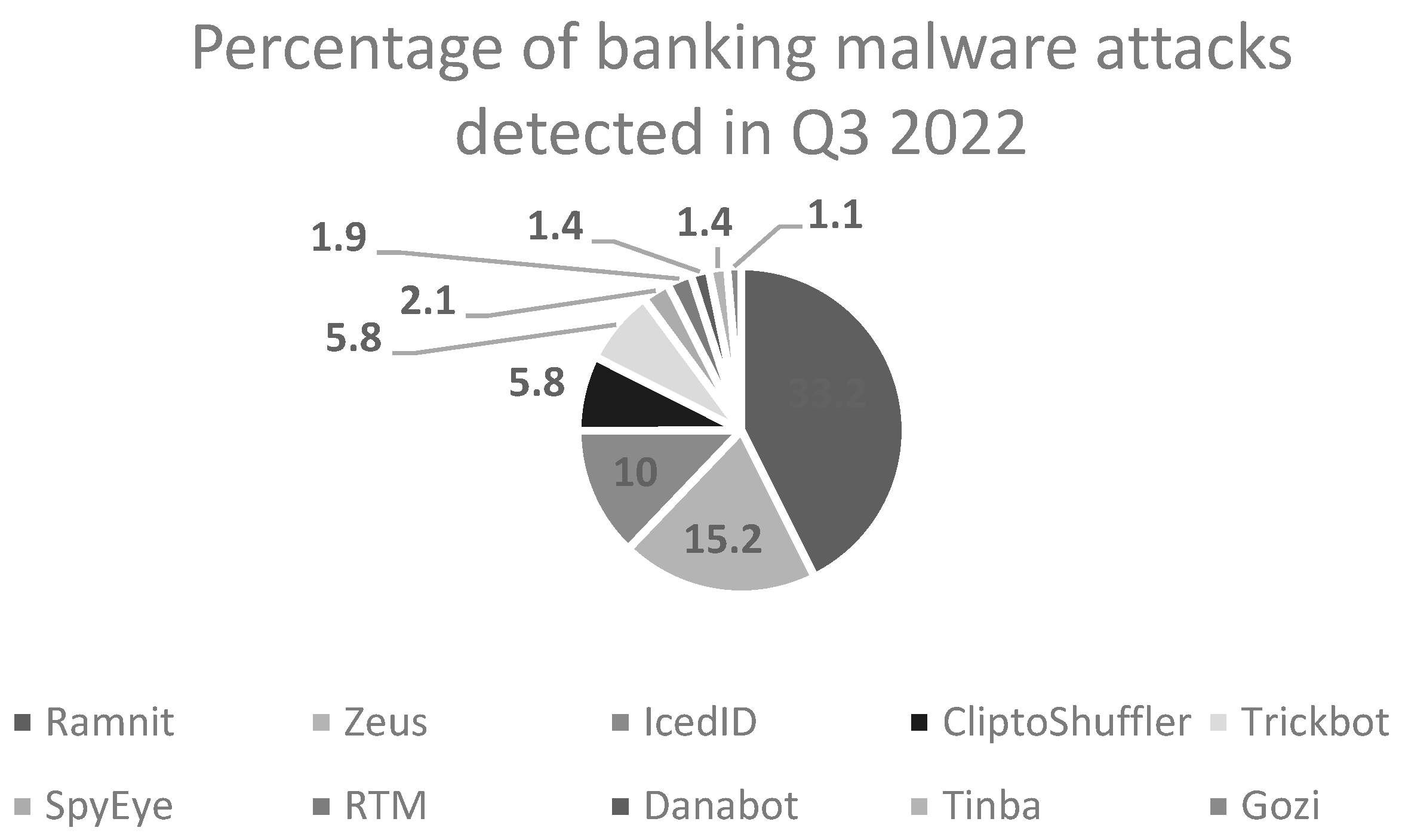

Figure 1 shows that Zeus and Ramnit were amongst the top ten banking malware variants discovered in Q3 of 2022 [

11].

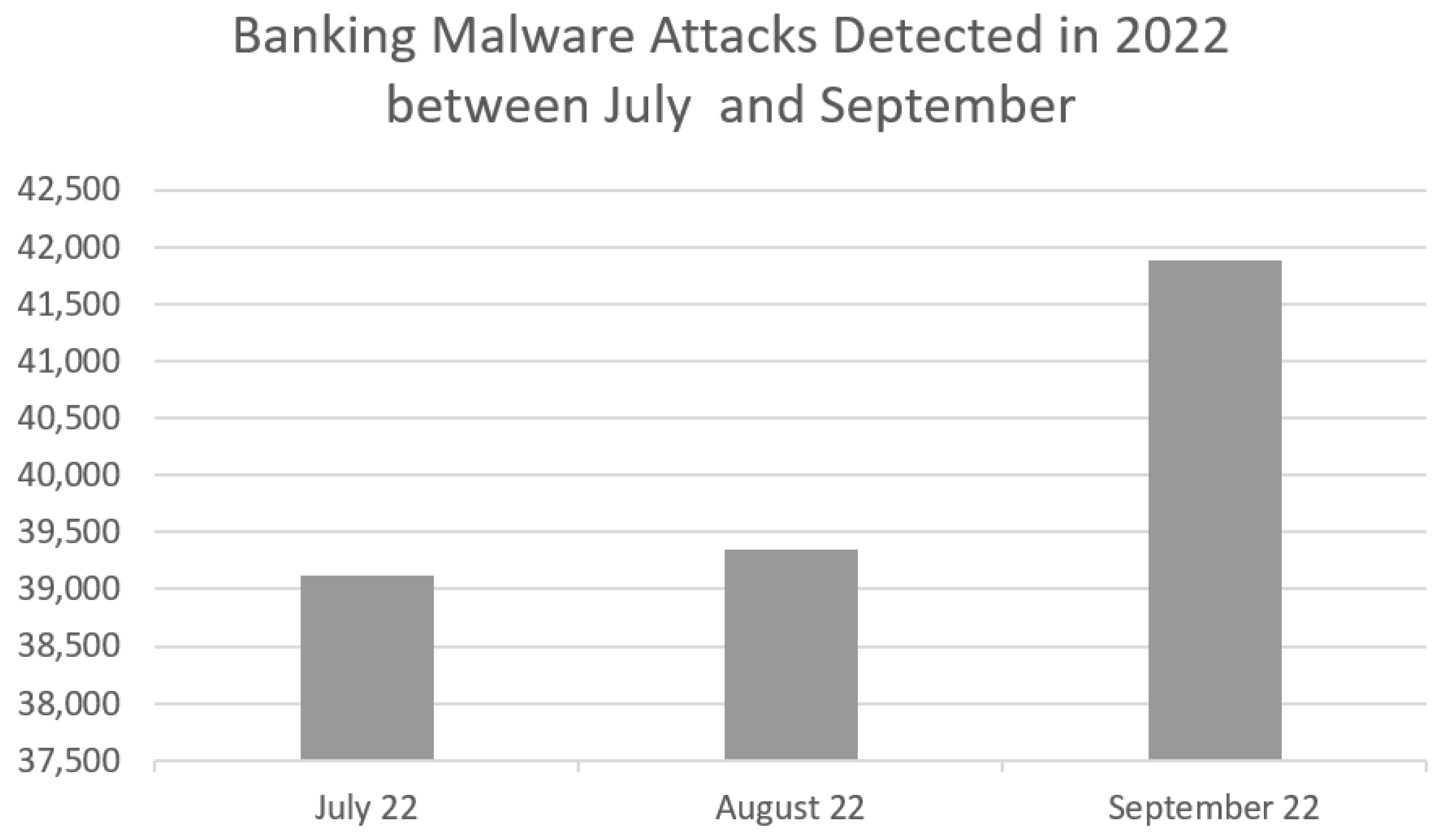

Figure 2 depicts the number of banking malware attacks that were detected during the same time and an upward trend is clearly visible [

11].

Banking malware have also diversified their tactics and expanded their capabilities and have, overtime, evolved into more sophisticated software tools that leverage several attack vectors to cause financial loss. The fact that threat actors can use Malware-as-a-service (MaaS) providers to target victims has also led to their increased prevalence and some of these MaaS providers can charge up to

$4000 per month to discharge their services [

12].

Many strategies exist to detect banking malware, and these include signature-based, anomaly based, behavior based and heuristic approaches [

13], but these do have limitations [

14]. These approaches and limitations are explored further over the next few sections however, some of these limitations include:

The need to update signature-based malware systems.

The inability of these systems to detect newer malware variants.

Unable to detect malware that uses sophisticated obfuscation techniques.

The inability to detect zero-day malware.

This research paper is broken down into the following sections. Firstly, a review is conducted of the Zeus, Zeus Panda and Ramnit banking malware variants and then a banking malware family tree is proposed. The purpose of this review is to understand the similarities and differences between the various banking malware variants. Next, a literature review of related research is provided followed by a problem statement. Finally, this paper proposes a machine learning approach for detecting banking malware and also, proposes a feature section approach that supports the proposed machine learning approach.

The main contributions of this paper are to develop a methodology and approach to detect several banking malware variants’ Command and Control communication network traffic (C&C) and distinguish them from benign network traffic using binary classification Machine Learning (ML) algorithms. Three ML algorithms and an ensemble approach are all examined, analyzed and compared in this paper and these include the Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF) and K-Nearest Neighbors KNN ML algorithms. An ensemble approach is also examined and this uses and combines all three algorithms.

This paper will compare the results of the binary ML classification algorithms to determine which one provides the best detection results when used to detect the Zeus banking malware C&C network traffic and other variants of the Zeus banking malware. The minimal number of features that could be utilized to identify the same banking malware variants is also determined. This paper aims to:

From all the ML algorithms being analyzed, identify which one performs the best.

Establish whether the features used to detect the Zeus banking malware can also be used to detect the other banking malware variants.

Determine a minimum set of features that could be used for detecting Zeus.

Determine a minimum set of features that could be used for detecting the other variants of the Zeus malware.

Compare the performance results of all the ML algorithms.

1.2. Overview of the Zeus Banking Malware

There are several traits that the Zeus banking malware has been seen to portray and these include [

15]:

Zeus malware is known to propagate like a virus and is normally spread using spam emails that contain a trojan horse with the malware embedded within the trojan.

Zeus normally attacks Windows systems and targets data such as usernames and passwords and other important information such as banking information.

Once the Zeus malware gets onto the device, it needs to perform several actions to infect the device. The Zeus bot inserts malicious code into the winlogin.exe process after copying itself to the system 32 directory and this is achieved by escalating its privileges and manipulating the Winlogin.exe and svchost processes. Two files are created, local.ds, which is used to download the configuration file and user.ds, which is used to transmit stolen data back to the threat actors’ C&C servers. The additional code injected into the svchost process is used by the Zeus bot for communication purposes and Zeus communicates using a Command and Control (C&C) channel which can either use a centralised or P2P architecture. In the centralised architecture, the IP address of the C&C server is hardcoded into the Bot’s binary file which leaves the bot vulnerable because if the C&C channel is discovered and blocked, the Zeus bot becomes inactive and is unable to recover [

16]. Modern day variants of the Zeus malware use a P2P architecture as this is more resilient to disconnections and are much harder to detect and block [

17]. One reason is simply because the IP address is not hardcoded into the bot binary and because in the P2P network, multiple bots can act as C&C servers. This architecture also allows stolen data to be routed through the bot network via these intermediary C&C bots and crucially, allows bots to recover from failures [

18]. This recovery is possible because each peer C&C bot can essentially provide support to a failed bot for example, by sending the failed bot an updated IP address to help it resume malicious communications.

1.3. Overview of the Zeus Panda Banking Malware

The Zeus Panda banking malware portrays similar characteristics to the Zeus banking malware and research shows that it infects devices using spam emails and exploit kits and it has been known to spread like a virus [

15]. The Zeus Panda’s communication architecture is similar to the Zeus banking malware architecture however, its communication is generally encrypted using RC4 or AES [

15]. The Zeus Panda authors have also enhanced the code to allow it to detect and evade security protection tools such as anti-virus software and firewalls [

19]. Zeus Panda is intelligent enough to detect that it is running in a virtual environment and upon sensing such an environment, it can disable itself to ensure researchers are unable to detect communication patterns [

19]. The Zeus Panda malware is difficult to detect and can persist on a device for a long time and researchers have concluded that the Zeus Panda is a sophisticated variant of the Zeus malware [

20].

1.4. Overview of the Ramnit Banking Malware

Ramnit is an enhanced version of the Zeus malware [

21] and spreads between devices just like a virus and it incorporates code from the Zeus banking malware. It is delivered to a device via spam emails or via exploit kits and once the C&C communication is established, the C&C communication traffic is encrypted using custom encryption techniques [

22]. Ramnit can also use HTTPS to obfuscate the communication channel and hide any data that is transmitted between systems. Ramnit is sophisticated enough to detect and evade security tools and once it infects a device, it can persist on the device for a long time [

22]. Ramnit can also use evasion techniques to avoid detection and some of these include the use of anti-debugging techniques, code injection and process handling, polymorphic capabilities, encryption and environmental awareness [

23].

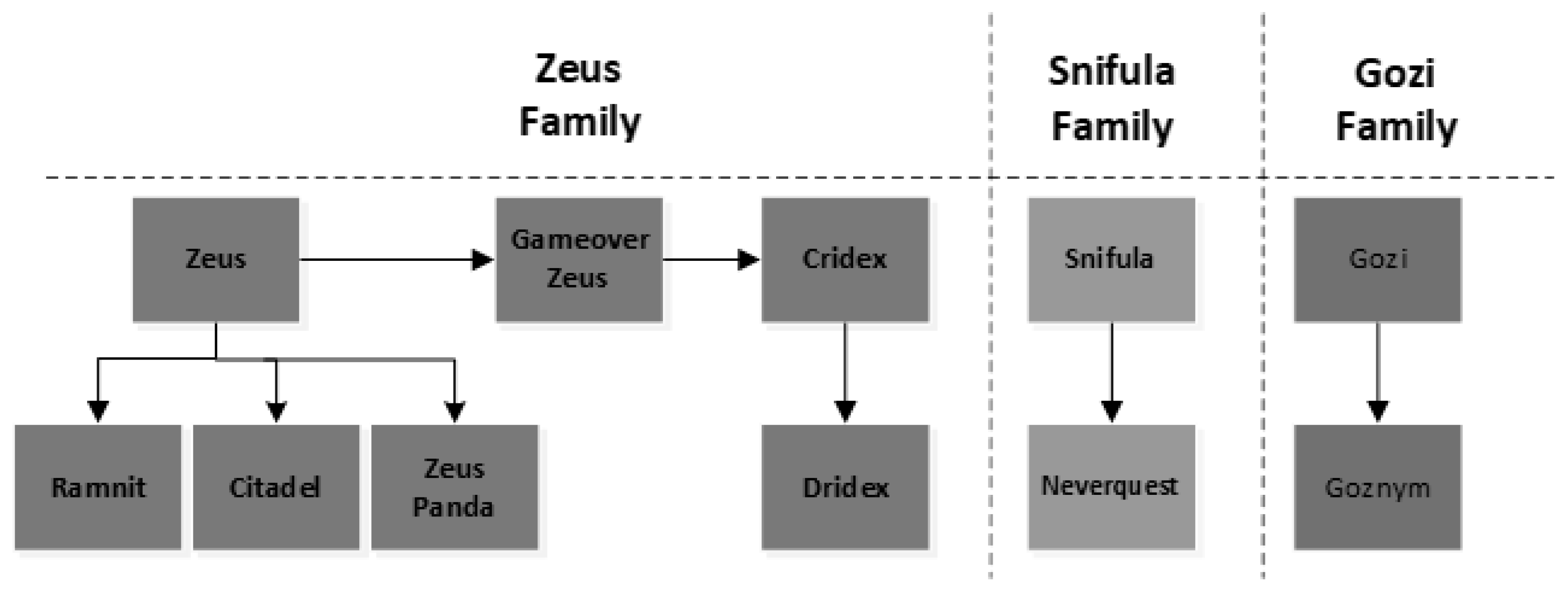

1.5. Proposed Banking Malware Tree

This section examines and discusses the relationship between the three banking malware variants that were discussed above and establishes a timescale of when they emerged.

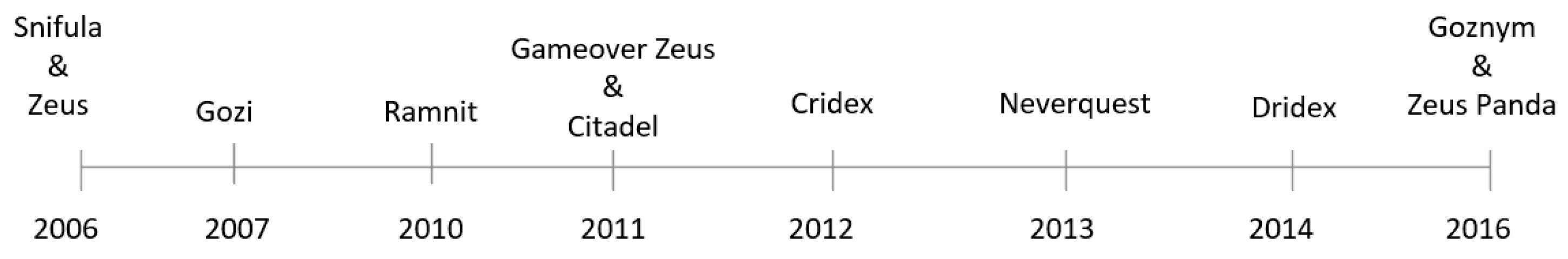

Figure 4 shows that Zeus was discovered in 2006 [

24], Ramnit was discovered in 2010, and Zeus Panda was discovered in 2016 [

25] and research indicates that they all share similar code and perform similar actions. Based on this research [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], this paper proposes that all banking malware variants belong to a specific family of banking malware, and this proposed family tree can be seen in

Figure 3. A historical timeline of a selection of banking malware variants can be seen in

Figure 4 which suggests that all banking malware variants can be traced back to one of the parent banking malware variants, Zeus, Snifula and Gozi, as shown in

Figure 3.

The key conclusions drawn from this research are that:

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 discusses some of the key research that has been conducted in this field. In section 3, a problem statement is presented.

Section 4 proposes a framework to detect the banking malware variants discussed in sections 1.2 to 1.4, section 5 analyses and compares the research findings and section 6 concludes with a summary and conclusion.

2. Related Studies

Malware detection approaches can be categorized using several methods. However, the method discussed by [

31] is used in this paper which is that malware detection can either be signature based, heuristic based or behavioral based. Also, malware detection tools can either be host based, or network based [

32], and this research examines a network-based approach as it is focusing on the C&C network communication traffic.

The authors in [

33] used the SVM machine learning algorithm to develop an intrusion detection system which uses the NSL-KDD dataset to classify network traffic. To select appropriate features, [

33] used a hybrid feature selection approach which ranks the features using a feature selection approach called Information Gain Ratio (IGR) and then, refines this further by using the k-means classifier. They achieved an accuracy of 99.32 and 99.37 when used with 23 and 30 features.

A simple yet effective method was developed by [

34] which involves extracting statical features called ‘function call frequency’ and ‘opcode frequency’ from Windows PE files. These features are extracted from both the executable files’ header and from the executable’s payload and the features were extracted from a total of 1,230 executable files. The dataset contained 800 malware and 430 non-malware executable files, and the experimental work was conducted using a tool called WEKA. Several classifiers were experimented with, and the results of these experiments can be seen in

table 1.

Research was carried out by [

35] who used an unsupervised machine learning algorithm to detect bot communication traffic. They used datasets obtained from the university of Georgia which contained bot traffic from both the Zeus and Waledac malware variants. Features were extracted from the dataset by using a tool called Netmate which extracts the traffic as flows and then analyses each flow to calculate their statistical features. The datasets were clustered using the WEKA tool and, all the experimental analysis was also conducted using this tool. The experimental results can be seen in

table 2.

BotOnus [

36] is a tool that extracts a set of flow specific feature vectors and then uses an online fixed-width clustering algorithm to arrange these features into unique clusters. Suspicious botnet clusters are defined as flow clusters that have at least two members that have an intra-cluster similarity above a certain threshold. All hosts inside these clusters are considered to be infected with bots. BotOnus is an online detection technique that uses unsupervised machine learning algorithms for detecting malicious bots. Because BotOnus employs an unsupervised method that is motivated by the inherent features of botnets, like group behaviors, it can identify unknown botnets without any prior knowledge of them.

Table 3 shows the experimental results that were obtained by using BotOnus.

RCC Detector (RCC3) is a tool developed by [

37] that uses a multi-layer perception (MLP) and a temporal persistence (TP) classifier to analyze network traffic flows to identify malware communication traffic. The botnet detection system was trained and tested using the DETER testbed and two datasets were used, the DARPA and LBNL datasets. The authors aimed to predict Zeus, Blackenergy and normal traffic and the key to this paper is that RCC examines traffic generated from a host. The tool achieved a detection rate of 97.7%.

3. Problem Statement

The goal of this study is to create a methodology and framework for predicting banking malware using machine learning approaches. Many malware detection approaches already exist and have been researched and used by researchers and some of these include signature-based approaches [

38,

39] and anomaly-based detection approaches [

40,

41] however, these do have limitations [

42]. For instance, signature-based systems are not able to detect zero-day malware or unknown malware variants, and they must be updated frequently to accommodate newly emerging malware variants.

Many of these problems can be solved with the aid of machine learning [

43], and this research has developed a framework and method that can identify various banking malware variants using machine learning. Although some experimental work has been done in this field [

33,

34,

35], little to no research has been done that seeks to detect a variety of banking malware variants by only training one dataset which belongs to only one banking malware variant. The goal of this research study is to develop a machine learning model using a single training dataset. Subsequently, this approach is employed to identify other banking malware variants, and the detection results are compared to identify which ML algorithms perform the best. This research also examines the minimum number of features that could be used to obtain satisfactory prediction result.

4. Research Methodology

This research paper aims to classify C&C network traffic flows as belonging to Zeus which indicates that the C&C network traffic is malicious. Bot samples are collected as pcap files and these pcap files are made up of network flows. A flow is defined as a sequence of packets flowing between a source and a destination host. Each flow is referred to as an ML sample and the features are extracted from these samples. For this research, supervised ML algorithms were chosen as these algorithms are well suited for solving predication and classification problems such as the one being researched in this paper [

44]. This paper analyses three supervised ML algorithms and these are the Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF) and the K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) ML algorithms and also examines an ensemble approach.

4.1. Machine Learning Algorithms

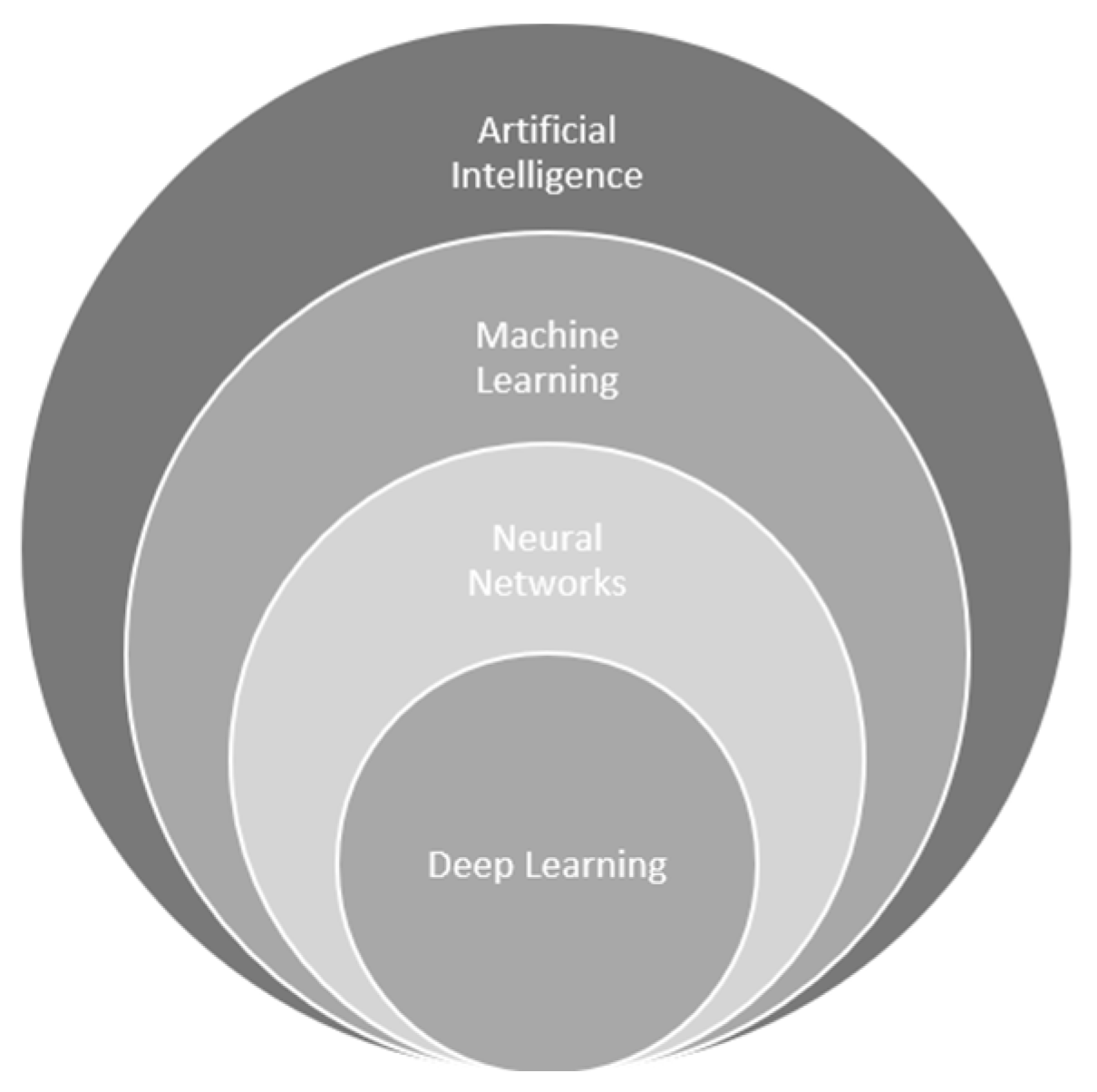

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is made up of several fields which include deep learning, neural networks and machine learning.

Figure 5 depicts the various fields of AI [

45].

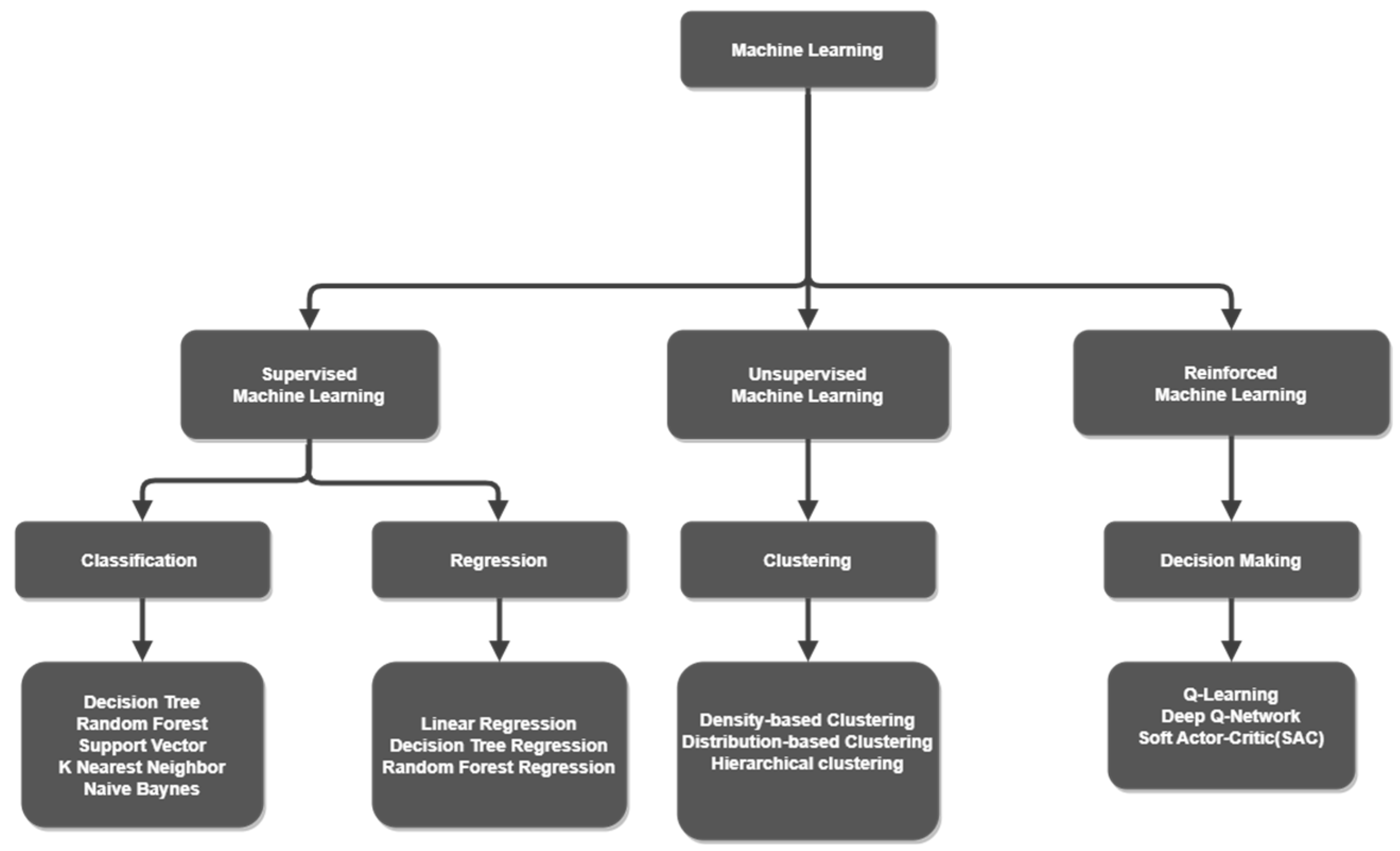

The most widely used approaches in machine learning are supervised, unsupervised and reinforced learning and

Figure 6 illustrates the various types of machine learning approaches [

46] that could be used. For this paper, supervised ML approaches are used.

There are several types of supervised ML approaches that could be considered for the problem being researched in this paper and these are [

46]:

Binary Classification – Two possible classifications can be predicted for example, an email can either be spam or not spam. The two possible classes are usually either normal or abnormal.

Multi-Class classification - Multiple classes are involved and each data point is classified into one of the available class options.

Multi-Label classification - Multiple classes can be predicted for each data point. For example, a house could be present in multiple photos.

For this research, the binary classification approach was selected as this has been used by many researchers to solve similar problems. For the supervised ML algorithms used in this research, a brief description of these is provided below.

One of the most effective and noteworthy machine learning methods for predictive modeling is the Decision Tree (DT) algorithm, which performs exceptionally well when dealing with binary classification problems [

47]. Since this research aims to ascertain whether the network flow is malicious (banking malware traffic) or benign, the decision tree technique is a good fit for this prediction problem. Additionally, the decision tree algorithm learns and makes predictions extremely quickly [

47].

In comparison to the decision tree algorithm, the Random Forest (RF) algorithm can be more effective, can produce better prediction results, and can lessen the likelihood of overfitting [

48]. It can do this because the RF algorithm can construct multiple decision trees which can help to improve prediction results. When utilizing the RF method, it is crucial to adjust the parameters of the algorithm, to improve the prediction accuracy. It can be challenging to foresee the ideal values in advance, and the parameters are chosen by experimentation. One of these parameters is the quantity of trees constructed during the training and testing phases and research shows that constructing more than 128 trees can raise the cost of training and testing while offering no appreciable improvement in accuracy [

49]. Constructing between 64 and 128 trees has shown to be the ideal number of trees that should be used, so, the experimental analysis for this research also used between 64 and 128 trees [

50].

The K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) ML algorithm is a supervised ML algorithm which is simple to implement and can produce good results. KNN is considered to be a non-parametric method [

51], meaning that it makes no assumptions about the underlying data. Following the computation of the distance between each new data point and every other training data point, the algorithm can classify the new data point in relation to the trained data points [

52].

An ensemble approach [

53] is also used in this research and for this, the random forest, decision tree and the k-nearest neighbor ML algorithms are all used in the ensemble approach. A voting classifier was used to combine the results of all the models, and for this research, a soft vote [

54] was used for predicting the malware. The soft voting approach is useful because it can select the average probability of each class [

55].

4.2. System Architecture and Methodology

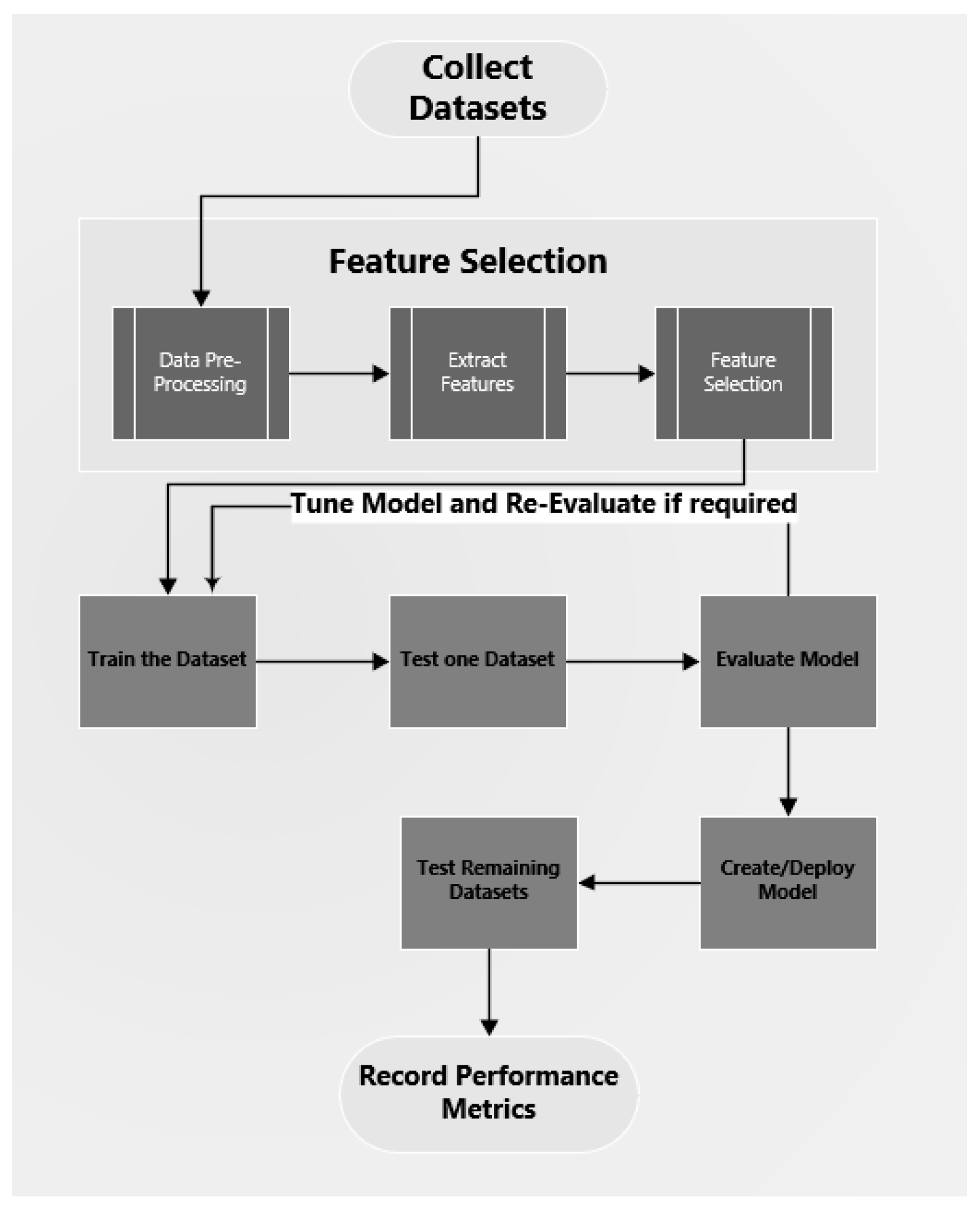

The system architecture shown in

Figure 7 depicts the steps that are completed for the experimental work completed during this research. These include:

The datasets are identified and collected.

Features are extracted from these datasets.

The extracted features are transferred to a csv file and prepared.

The features are selected for training and testing.

The algorithm is trained and tested, and a model is created. Only one dataset is used for the training.

The model is tuned and trained and tested again if required.

The model is used to test and evaluate the remaining datasets.

Deploy the final model and test all the data samples and create a report highlighting the evaluation metrics.

4.3. Data Samples

In this study, a variety of datasets were collected, and these datasets represent real-world activity that were captured by various reputable organizations. Six datasets were used for this research, and these were collected from Zeustracker [

56], Stratosphere [

57], Abuse.ch [

58] and Dalhouse University [

59]. Abuse.ch correlates samples from commercial and open-source platforms such as VirusTotal, ClamAV, Karspersky and Avast [

58]. Dalhousie universities’ botnet samples are part of the NIMS botnet research project and have been widely utilized by many researchers [

59].

Table 4 defines all the data sets that were used during this research and provides some details around the banking malware variant, the year that the samples were collected and the number of flows extracted from these samples.

4.4. Feature Selection

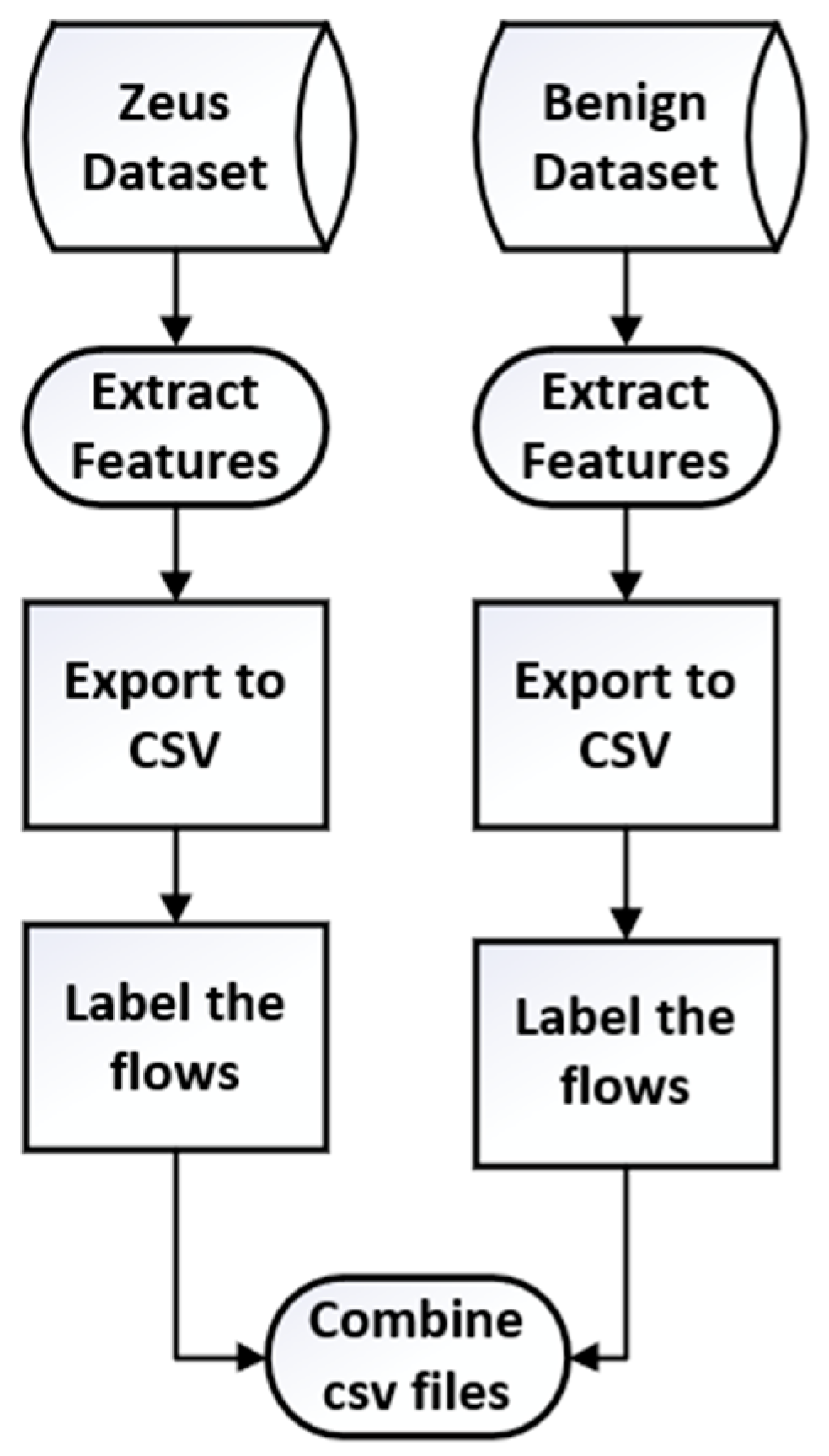

The procedure for gathering and preparing the data can be seen in

Figure 8 and this is discussed further in this section. The features were extracted and exported into a CSV file and a total of 44 features were extracted. It is important to select the appropriate and best features as this helps reduce overfitting and computational cost and helps the ML algorithm learn faster [

60,

61]. Several approaches can be used to identify the appropriate features, and the three predominant approaches are [

62]:

Filter method - Feature selection is independent of the ML algorithm.

Wrapper method - Features are selectively used to train the ML algorithm and through continual experimental analysis, the best features are selected for the final model. This method can be very time-consuming.

Hybrid – Which is a fusion of the filter and wrapper approaches.

For this research, the features were analyzed using the filter-based approach and three automated feature selection algorithms were used for this analysis, and these included the ANOVA [

63], RFE [

64] and SelectKBest [

65] feature selection algorithms. This empirical analysis determined that the following ten features would be the most appropriate and minimum number of features required for predicting the different malware variants.

mean_fpktl.

min_fpktl.

min_bpktl.

min_fiat.

mean_fiat.

mean_biat.

min_biat.

sflow_fpackets.

sflow_fbytes.

Duration.

The above ten features were used in the training and testing of the machine learning algorithms and the results of the experimental analysis can be viewed in section 5.

4.5. Evaluation Approach of the Experimental Analysis

The evaluation metrics, precision, recall, and f1-Score are used for the experimental analysis conducted for this research. Precision is the percentage of correctly identified positive cases from the whole data sample [

66] and recall is the percentage of correctly identified positive cases from the positive samples only [

67]. The formulas used are:

The f1-Score considers both the positive and negative cases combined, and the formula used to calculate the f1-score is set out below [

68]:

A confusion matrix [

69], shown in

table 5, will also be generated for each experiment that is conducted. The confusion matrix calculates the True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP) and False Negatives (FN) scores for each dataset.

5. Results

This section presents the training and testing results for all the ML algorithms and compares the prediction results for each of the datasets. For each ML algorithm, two tables are presented. The first table shows the precision, recall and f1-score results and the second table depict the following information: the number of samples tested; the number of samples correctly classified (true positives); the number of samples misclassified (false negatives). The table also depicts the prediction results of the benign C&C network samples.

5.1. Training and Testing the Decision Tree Machine Learning Algorithms

The DT ML algorithm was trained using the features defined in

Section 4.4 and for the training, 3 folds were used. A training accuracy of 0.974 was achieved and

table 6 shows the testing results and

table 7 depicts a confusion matrix for each of the datasets tested. By examining the key metric, which is the recall score for the malware, most of the recall scores are above 95. The lowest recall rate was 66 for dataset6 and the highest recall score was 99 achieved by both datasets 3 and 4.

5.2. Training and Testing the Random Forest (RF) Machine Learning Algorithm

The results of testing the RF ML algorithm can be seen in

table 8 and

table 9. A training accuracy of 0.997 was achieved and by examining the key metric, which is the recall score for the malware, most of the recall results are above 95. The lowest recall score was for dataset6, which was 66, and the highest recall score was obtained by datasets 3 and 4, which 99.

5.3. Training and Testing the K-Neaest Neigbor (KNN) Machine Learning Algorithm

The KNN testing results can be seen in

table 10 and

table 11. A training accuracy of 0.950 was achieved and by examining the key metric, which is the recall score for the malware traffic, most of the malware recall results are above 90. The lowest malware recall rate was 50, which was achieved by dataset6, and the highest malware recall score was 100 achieved by dataset3.

5.4. Training and Testing Using the Ensemble Machine Learning Approach

An ensemble approach was used to train and test all the datasets and the results of these can be seen in

table 12 and

table 13. Again, focusing on the malware recall score for each dataset, the highest malware recall score was achieved with both datasets 3 and 4 with a score of 99. The lowest malware recall score achieved was for dataset6 which was 66.

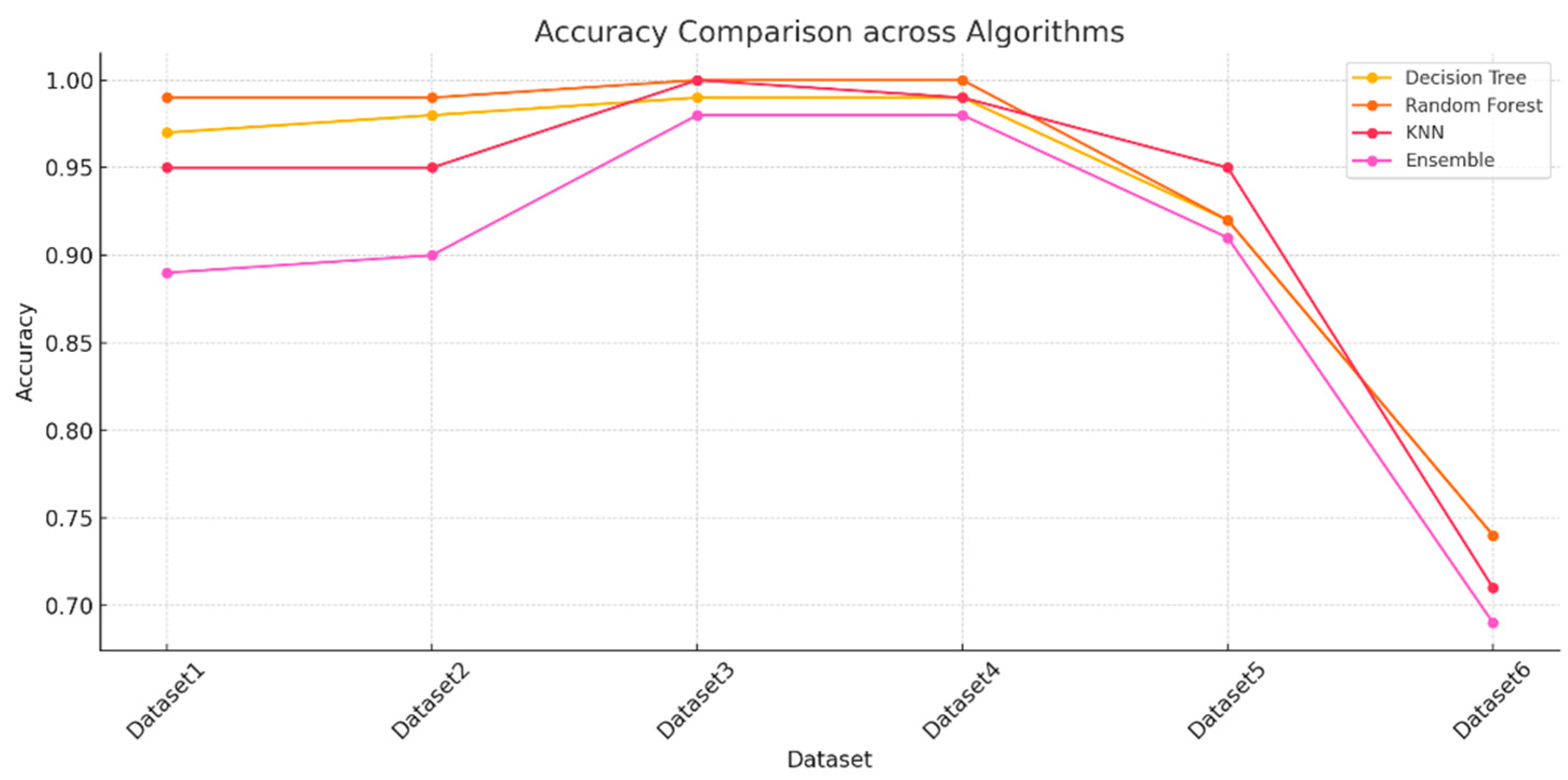

5.5. Comparing the Predication Results of All the Algorithms Tested

The results obtained from testing all the algorithms are compared in this section.

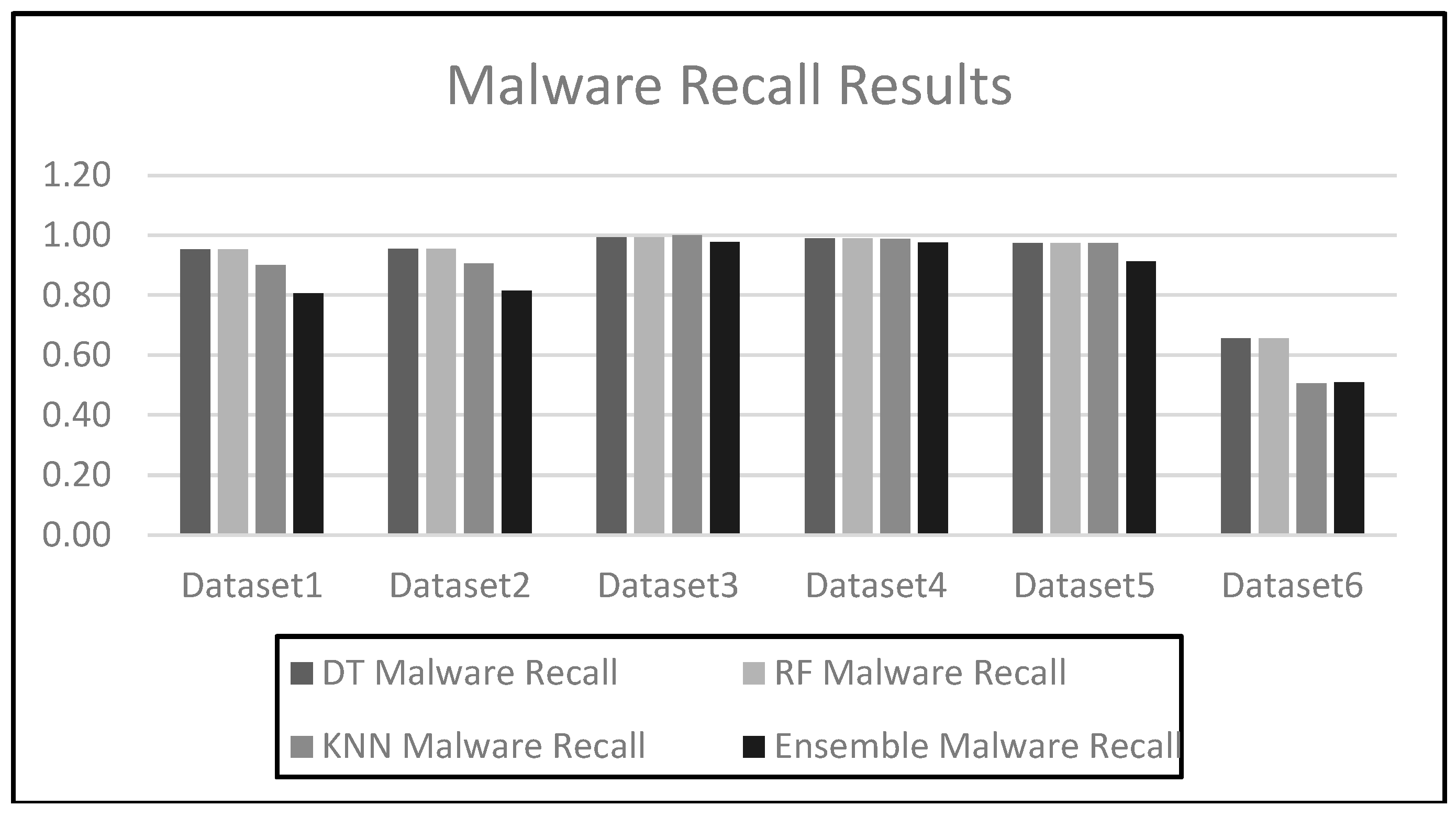

Figure 9 shows the malware recall results of all the algorithms when tested against all the datasets and

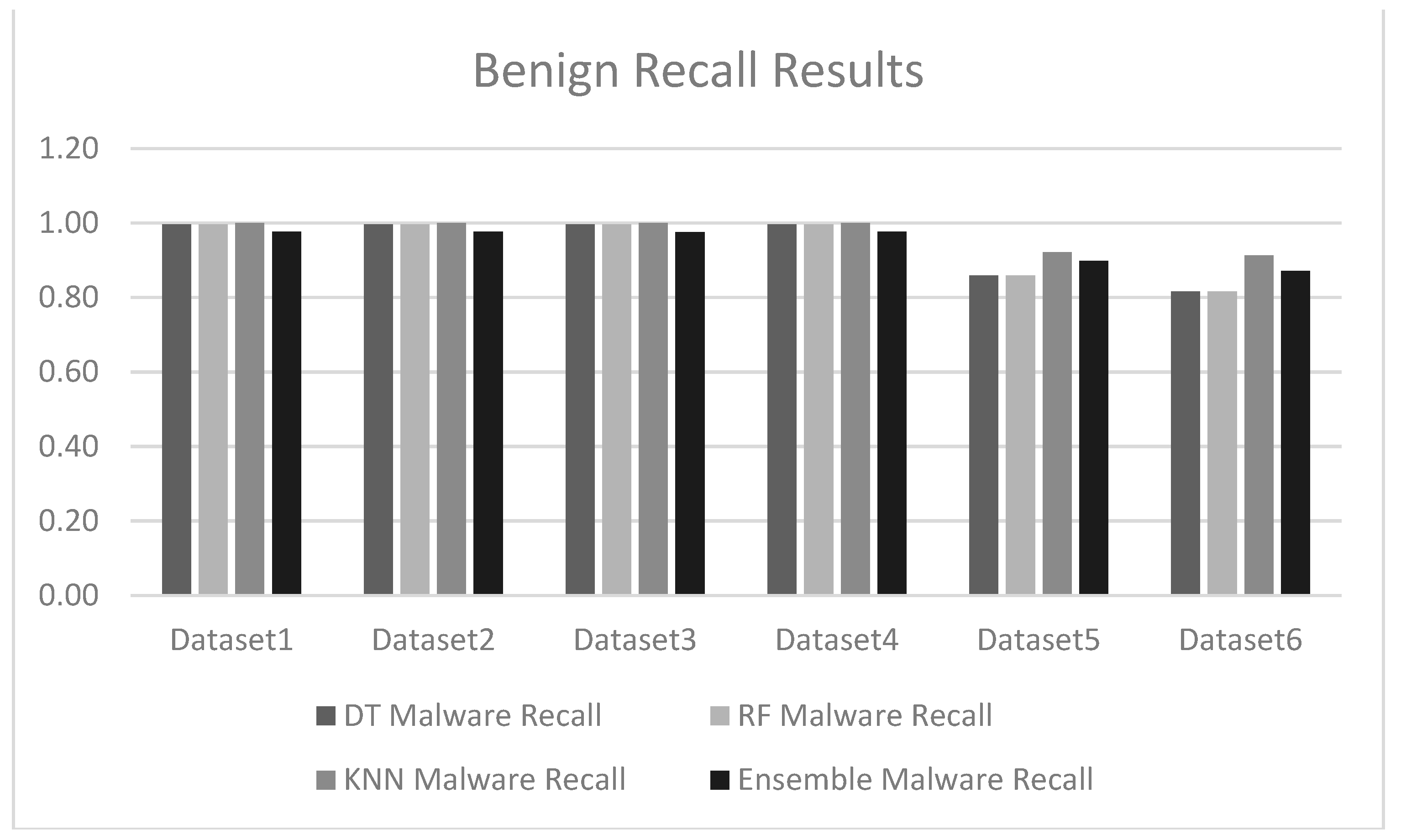

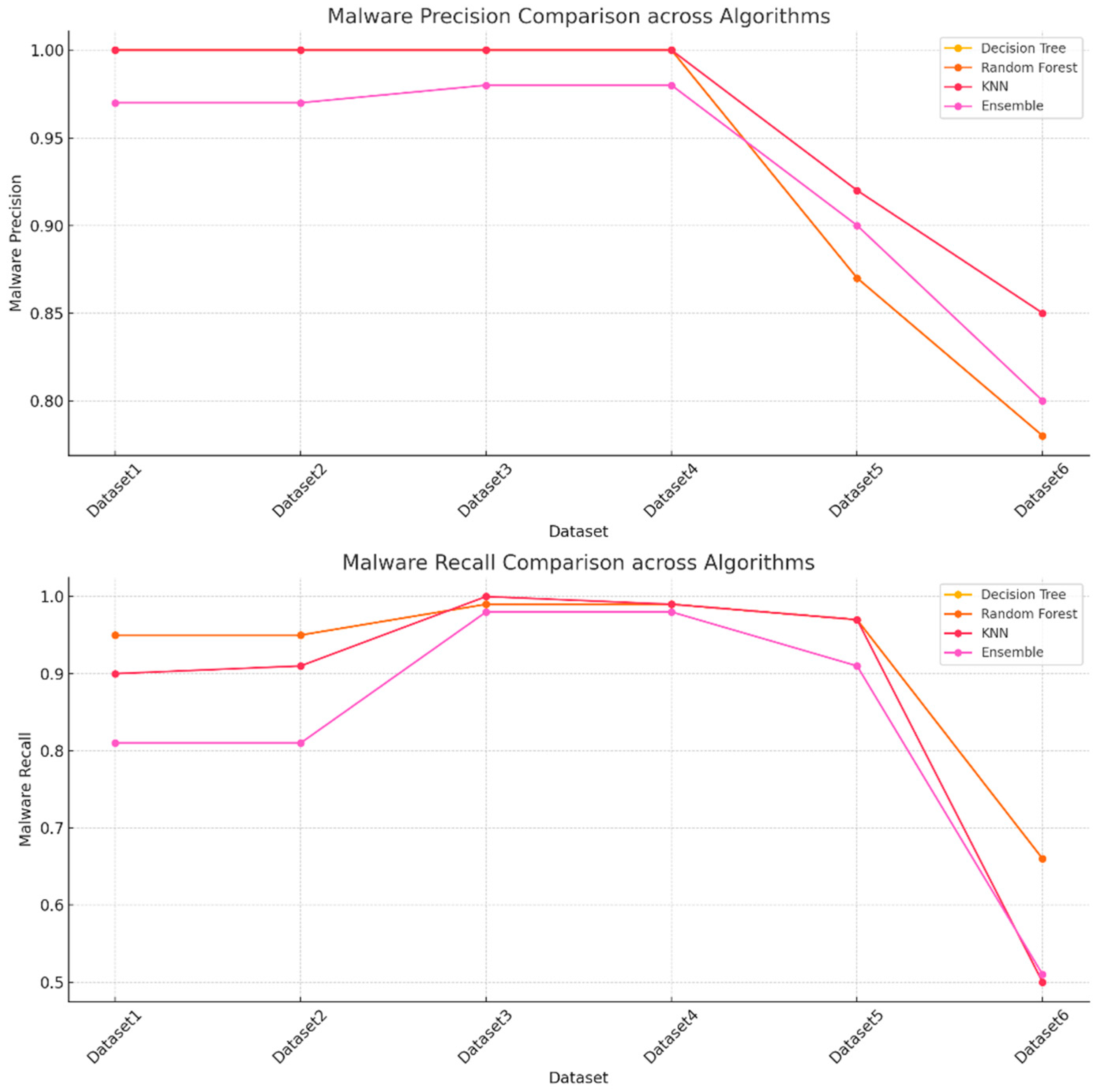

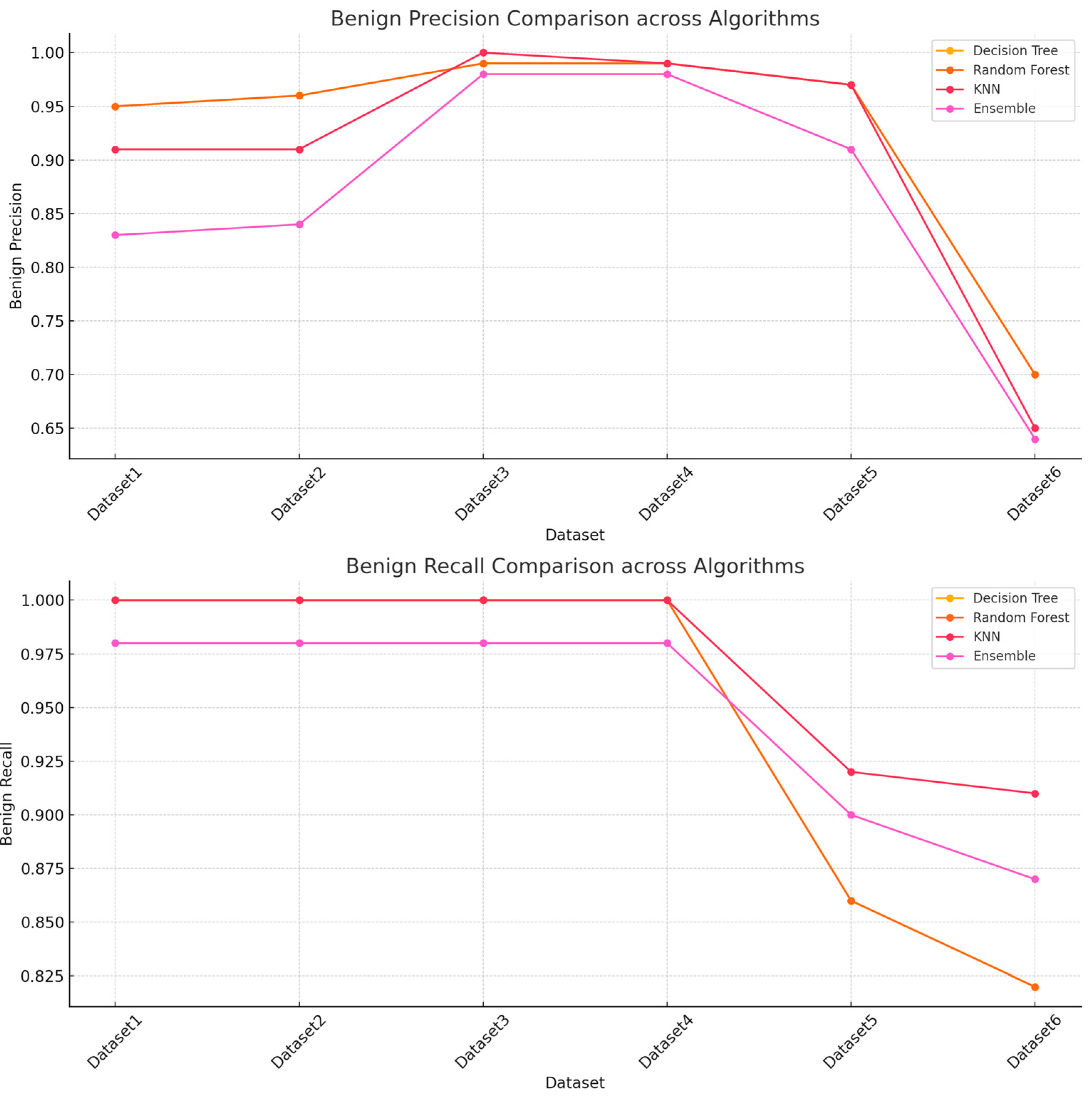

Figure 10 shows the benign traffic recall scores. An expanded view of the results can be seen in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 which show both the recall and precision scores for both the malware and benign traffic samples.

The results obtained during the testing phase indicate that the decision tree algorithm performed consistently well across all the datasets with high accuracy scores for datasets 1 - 4. Dataset6 does show lower performance with an accuracy score of 0.74, and this seems to indicate that the decision tree algorithm faced some challenges when used for testing on a large dataset. The random forest algorithm also performed well and achieved similar results to the decision tree algorithm. The KNN algorithm performed extremely well across datasets 1 - 4 as the accuracy scores were close to 100 for all these datasets.

The random forest and decision tree algorithms generally perform better than the k-nearest neighbor and ensemble approaches on most datasets, especially for smaller and less complex datasets. K-nearest neighbor performs exceptionally well for smaller datasets but suffers with larger or more complex data. The ensemble approach does provide a balanced approach but performs poorly when compared to the decision tree and random forest ML algorithms, especially for larger datasets.

The experimental results and the patterns observed suggest that the random forest and decision tree models are more robust and consistent across all the datasets, while the k-nearest neighbor and ensemble models may face some difficulties with larger or more complex data. Dataset 6 seems particularly challenging, reducing performance across all the datasets.

This paper has demonstrated an approach that can be used to detect banking malware and some its variants and has demonstrated that the methodology does work across multiple datasets and other variants of the Zeus malware.

6. Conclusions

The framework's ability to identify banking malware and its variants have been demonstrated by the empirical analysis conducted during this research. The research shows that the methodology and framework used for this study can identify both older and newer versions of the Zeus banking malware. It is possible that this approach can be used to detect a large number of banking malware variants without having to examine each one in order to understand its characteristics. This is because the framework and technique developed during this research identified key features that could be used and may also predict other banking malware variants. Also, this research has shown that a reduced set of features can be used for detecting banking malware and this should help increase the performance and time required for training and testing machine learning or deep learning algorithms, especially for large datasets. This research will also benefit other researchers as they should be able to adopt this approach in their own research and will have a good base to begin conducting experiments of a similar nature.

It may be possible to advance this research in the future by improving the methodology to include more banking malware variants, especially variants belonging to a different banking malware family. Additionally, more study may be done to identify other malware types and increase the prediction accuracy of these predictions. The results of this study may also be utilized by researchers to develop an intrusion detection system (IDS) that can identify a variety of malware, and by anti-virus manufacturers to support their development of malware detection tools. Once the infection has been identified, action can also be taken against the malicious communications. Researchers can improve their work by using the results of this study to create their own malware prediction systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K.; software, M.K.; validation, M.K.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, M.K.; resources, M.K.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Wadhwa, Amit, and Neerja Arora. "A Review on Cyber Crime: Major Threats and Solutions." International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Science 8, no. 5 (2017).

- Morgan, Steve. 2022. “Cybercrime to Cost the World 8 Trillion Annually in 2023.” Cybercrime Magazine. , 2022. https://cybersecurityventures.com/cybercrime-to-cost-the-world-8-trillion-annually-in-2023/. 17 October.

- “Banking Malware Threats Surging as Mobile Banking Increases – Nokia Threat Intelligence Report.” n.d. Nokia. https://www.nokia.com/about-us/news/releases/2021/11/08/banking-malware-threats-surging-as-mobile-banking-increases-nokia-threat-intelligence-report/.

- Kuraku, Sivaraju, and Dinesh Kalla. "Emotet malware—a banking credentials stealer." Iosr J. Comput. Eng 22 (2020): 31-41.

- Etaher, Najla, George RS Weir, and Mamoun Alazab. "From zeus to zitmo: Trends in banking malware." In 2015 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ISPA, vol. 1, pp. 1386-1391. IEEE, 2015.

- “Godfather Banking Trojan Spawns 1.2K Samples across 57 Countries.” 2024. Darkreading.com. 2024. https://www.darkreading.com/endpoint-security/godfather-banking-trojan-spawns-1k-samples-57-countries.

- Pilania, Suruchi, and Rakesh Singh Kunwar. "Zeus: In-Depth Malware Analysis of Banking Trojan Malware." In Advanced Techniques and Applications of Cybersecurity and Forensics, pp. 167-195. Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Kazi, Mohamed Ali, Steve Woodhead, and Diane Gan. "An investigation to detect banking malware network communication traffic using machine learning techniques." Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 3, no. 1 (2022): 1-23.

- Owen, Harry, Javad Zarrin, and Shahrzad M. Pour. "A survey on botnets, issues, threats, methods, detection and prevention." Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 2, no. 1 (2022): 74-88.

- Boukherouaa, El Bachir, Mr Ghiath Shabsigh, Khaled AlAjmi, Jose Deodoro, Aquiles Farias, Ebru S. Iskender, Mr Alin T. Mirestean, and Rangachary Ravikumar. Powering the digital economy: Opportunities and risks of artificial intelligence in finance. International Monetary Fund, 2021.

- AMR. 2022. “IT Threat Evolution in Q3 2022. Non-Mobile Statistics.” Securelist.com. Kaspersky. , 2022. https://securelist.com/it-threat-evolution-in-q3-2022-non-mobile-statistics/107963/. 18 November.

- Kazi, Mohamed Ali, Steve Woodhead, and Diane Gan. "Comparing the performance of supervised machine learning algorithms when used with a manual feature selection process to detect Zeus malware." International Journal of Grid and Utility Computing 13, no. 5 (2022): 495-504.

- Punyasiri, D. L. S. "Signature & Behavior Based Malware Detection." (2023).

- Gopinath, Mohana, and Sibi Chakkaravarthy Sethuraman. "A comprehensive survey on deep learning based malware detection techniques." Computer Science Review 47 (2023): 100529.

- Kazi, M.; Woodhead, S.; Gan, D. A contempory Taxonomy of Banking Malware. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Secure Cyber Computing and Communications, Jalandhar, India, 15–17 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Falliere, N.; Chien, E. Zeus: King of the Bots. 2009. Available online: https://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://pure.port.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/42722286/Understanding_and_Mitigating_Banking_Trojans.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwizroXLwZqJAxU-VUEAHdgzKqEQFnoECDMQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1St11bbRwbhYj9IB4VdQv4 (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Lelli, A. Zeusbot/Spyeye P2P Updated, Fortifying the Botnet. Available online: https://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/zeusbotspyeye-p2p-updated-fortifying-botnet (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- Cluley, Graham. “GameOver Zeus Malware Returns from the Dead.” Graham Cluley, , 2014. https://grahamcluley.com/gameover-zeus-malware/. 14 July.

- Niu, Zequn, Jingfeng Xue, Dacheng Qu, Yong Wang, Jun Zheng, and Hongfei Zhu. "A novel approach based on adaptive online analysis of encrypted traffic for identifying Malware in IIoT." Information Sciences 601 (2022): 162-174.

- Ebach, Luca. "Analysis Results of Zeus. Variant. Panda." G DATA Advanced Analytics (2017).

- Lamb, Christopher. Advanced Malware and Nuclear Power: Past Present and Future. No. SAND2019-14527C. Sandia National Lab.(SNL-NM), Albuquerque, NM (United States), 2019.

- De Carli, Lorenzo, Ruben Torres, Gaspar Modelo-Howard, Alok Tongaonkar, and Somesh Jha. "Botnet protocol inference in the presence of encrypted traffic." In IEEE INFOCOM 2017-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, pp. 1-9. IEEE, 2017.

- Lioy, Antonio, Andrea Atzeni, and Francesco Romano. "Machine Learning for malware characterization and identification." (2023).

- Black, Paul, Iqbal Gondal, and Robert Layton. “A Survey of Similarities in Banking Malware Behaviours.” Computers & Security 77 (August 2018): 756–72. [CrossRef]

- Pilania, Suruchi, and Rakesh Singh Kunwar. "Zeus: In-Depth Malware Analysis of Banking Trojan Malware." In Advanced Techniques and Applications of Cybersecurity and Forensics, pp. 167-195. Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- CLULEY, Graham. “Russian Creator of NeverQuest Banking Trojan Pleads Guilty in American Court.” Hot for Security, 2019. https://www.bitdefender.com/en-us/blog/hotforsecurity/russian-creator-of-neverquest-banking-trojan-pleads-guilty-in-american-court/.

- Fisher, Dennis. “Cridex Malware Takes Lesson from GameOver Zeus.” Threatpost.com. Threatpost, , 2014. https://threatpost.com/cridex-malware-takes-lesson-from-gameover-zeus/107785/. 15 August.

- Ionut Ilascu. “Softpedia.” softpedia, , 2014. https://news.softpedia.com/news/Cridex-Banking-Malware-Variant-Uses-Gameover-Zeus-Thieving-Technique-455193.shtml. 16 August.

- Andriesse, Dennis, Christian Rossow, Brett Stone-Gross, Daniel Plohmann, and Herbert Bos. "Highly resilient peer-to-peer botnets are here: An analysis of gameover zeus." In 2013 8th International Conference on Malicious and Unwanted Software:" The Americas"(MALWARE), pp. 116-123. IEEE, 2013.

- Sarojini, S. , and S. Asha. "Botnet detection on the analysis of Zeus panda financial botnet." Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol 8 (2019): 1972-1976.

- Aboaoja, Faitouri A., Anazida Zainal, Fuad A. Ghaleb, Bander Ali Saleh Al-Rimy, Taiseer Abdalla Elfadil Eisa, and Asma Abbas Hassan Elnour. "Malware detection issues, challenges, and future directions: A survey." Applied Sciences 12, no. 17 (2022): 8482.

- Chen, Ruidong, Weina Niu, Xiaosong Zhang, Zhongliu Zhuo, and Fengmao Lv. "An effective conversation-based botnet detection method." Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2017, no. 1 (2017): 4934082.

- Jha, Jayshree, and Leena Ragha. "Intrusion detection system using support vector machine." International Journal of Applied Information Systems (IJAIS) 3 (2013): 25-30.

- Singla, Sanjam, Ekta Gandotra, Divya Bansal, and Sanjeev Sofat. "A novel approach to malware detection using static classification." International Journal of Computer Science and Information Security 13, no. 3 (2015): 1-5.

- Wu, Wei, Jaime Alvarez, Chengcheng Liu, and Hung-Min Sun. "Bot detection using unsupervised machine learning." Microsystem Technologies 24 (2018): 209-217.

- Yahyazadeh, Mosa, and Mahdi Abadi. "BotOnus: An Online Unsupervised Method for Botnet Detection." ISeCure 4, no. 1 (2012).

- Soniya, B. , and M. Wilscy. "Detection of randomized bot command and control traffic on an end-point host." Alexandria Engineering Journal 55, no. 3 (2016): 2771-2781.

- Ghafir, I.; Prenosil, V.; Hammoudeh, M.; Baker, T.; Jabbar, S.; Khalid, S.; Jaf, S. BotDet: A System for Real Time Botnet Command and Control Traffic Detection. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 38947–38958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Agarwal.; S. Satapathy, Implementation of signature-based detection system using snort in windows, International Journal of Computer Applications & Information Technology 2014, vol. 3, no. 3.

- He, S.; Zhu, J.; He, P.; Lyu, M.R. Experience report: System log analysis for anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 27th international symposium on software reliability engineering (ISSRE), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 23–27 October 2016; pp. 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Qian, Y.; Zou, Q.; Liu, P.; Xiang, J. DeepSyslog: Deep Anomaly Detection on Syslog Using Sentence Embedding and Metadata. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2022, 17, 3051–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisat, A.; Gondal, I.; Vamplew, P.; Kamruzzaman, J. Survey of intrusion detection systems: Techniques, datasets and challenges. Cybersecurity 2019, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Said, Z.; Memon, S.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Khalid, M.; Nguyen, X.P.; Arıcı, M.; Hoang, A.T.; Nguyen, L.H. Comparative evaluation of AI-based intelligent GEP and ANFIS models in prediction of thermophysical properties of Fe3O4-coated MWCNT hybrid nanofluids for potential application in energy systems. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, M.; Nygard, K.E.; Gomes, R.; Chowdhury, M.M.; Rifat, N.; Connolly, J.F. Cybersecurity Threats and Their Mitigation Approaches Using Machine Learning—A Review. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2022, 2, 527–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Rene Y., Aaron S. Coyner, Jayashree Kalpathy-Cramer, Michael F. Chiang, and J. Peter Campbell. "Introduction to machine learning, neural networks, and deep learning." Translational vision science & technology 9, no. 2 (2020): 14-14.

- Kumar, Ajitesh. “Difference: Binary, Multiclass & Multi-Label Classification.” Data Analytics, , 2022. https://vitalflux.com/difference-binary-multi-class-multi-label-classification/?utm_content=cmp-true. 16 May.

- Elmachtoub, Adam N., Jason Cheuk Nam Liang, and Ryan McNellis. "Decision trees for decision-making under the predict-then-optimize framework." In International conference on machine learning, pp. 2858-2867. PMLR, 2020.

- Liberman, Neil. “Decision Trees and Random Forests.” Towards Data Science. Towards Data Science, , 2017. https://towardsdatascience.com/decision-trees-and-random-forests-df0c3123f991. 27 January.

- Oshiro, Thais Mayumi, Pedro Santoro Perez, and José Augusto Baranauskas. "How many trees in a random forest?." In Machine Learning and Data Mining in Pattern Recognition: 8th International Conference, MLDM 2012, Berlin, Germany, -20, 2012. Proceedings 8, pp. 154-168. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012. 13 July.

- Kazi, Mohamed Ali, Steve Woodhead, and Diane Gan. "Detecting Zeus Malware Network Traffic Using the Random Forest Algorithm with Both a Manual and Automated Feature Selection Process." In IOT with Smart Systems: Proceedings of ICTIS 2022, Volume 2, pp. 547-557. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2022.

- Suyal, Manish, and Parul Goyal. "A review on analysis of k-nearest neighbor classification machine learning algorithms based on supervised learning." International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology 70, no. 7 (2022): 43-48.

- Aggarwal, Charu C., and Charu C. Aggarwal. Data classification. Springer International Publishing, 2015.

- Chung, Jetli, and Jason Teo. "Single classifier vs. ensemble machine learning approaches for mental health prediction." Brain informatics 10, no. 1 (2023): 1.

- Salur, Mehmet Umut, and İlhan Aydın. "A soft voting ensemble learning-based approach for multimodal sentiment analysis." Neural Computing and Applications 34, no. 21 (2022): 18391-18406.

- Jabbar, Hanan Ghali. "Advanced Threat Detection Using Soft and Hard Voting Techniques in Ensemble Learning." Journal of Robotics and Control (JRC) 5, no. 4 (2024): 1104-1116.

- Shomiron. zeustracker. Available online: https://github.com/dnif-archive/enrich-zeustracker (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Stratosphere. Stratosphere Laboratory Datasets. Available online: https://www.stratosphereips.org/datasets-overview Retrieved (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Abuse.ch. Fighting malware and botnets. Available online: https://abuse.ch/ (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Haddadi, F.; Zincir-Heywood, A.N. Benchmarking the effect of flow exporters and protocol filters on botnet traffic classification. IEEE Syst. J. 2014, 10, 1390–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasongo, Sydney Mambwe, and Yanxia Sun. "A deep learning method with filter based feature engineering for wireless intrusion detection system." IEEE access 7 (2019): 38597-38607.

- Miller, Shane, Kevin Curran, and Tom Lunney. "Multilayer perceptron neural network for detection of encrypted VPN network traffic." In 2018 International conference on cyber situational awareness, data analytics and assessment (Cyber SA), pp. 1-8. IEEE, 2018.

- Kazi, Mohamed Ali, Steve Woodhead, and Diane Gan. 2023. "An Investigation to Detect Banking Malware Network Communication Traffic Using Machine Learning Techniques" Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 3, no. 1: 1-23.

- Nasiri, Hamid, and Seyed Ali Alavi. "A Novel Framework Based on Deep Learning and ANOVA Feature Selection Method for Diagnosis of COVID-19 Cases from Chest X-Ray Images." Computational intelligence and neuroscience 2022, no. 1 (2022): 4694567.

- Alshanbari, Huda M., Tahir Mehmood, Waqas Sami, Wael Alturaiki, Mauawia A. Hamza, and Bandar Alosaimi. "Prediction and classification of COVID-19 admissions to intensive care units (ICU) using weighted radial kernel SVM coupled with recursive feature elimination (RFE)." Life 12, no. 7 (2022): 1100.

- Kavya D, “Optimizing Performance: SelectKBest for Efficient Feature Selection in Machine Learning,” Medium, , 2023, https://medium.com/@Kavya2099/optimizing-performance-selectkbest-for-efficient-feature-selection-in-machine-learning-3b635905ed48. 16 February.

- Luan, Hui, and Chin-Chung Tsai. "A review of using machine learning approaches for precision education." Educational Technology & Society 24, no. 1 (2021): 250-266.

- Davis, Jesse, and Mark Goadrich. "The relationship between Precision-Recall and ROC curves." In Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on Machine learning, pp. 233-240. 2006.

- Fourure, Damien, Muhammad Usama Javaid, Nicolas Posocco, and Simon Tihon. "Anomaly detection: How to artificially increase your f1-score with a biased evaluation protocol." In Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, pp. 3-18. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021.

- Visa, Sofia, Brian Ramsay, Anca L. Ralescu, and Esther Van Der Knaap. "Confusion matrix-based feature selection." Maics 710, no. 1 (2011): 120-127.

Figure 1.

Top ten malware discovered in Q3 of 2022.

Figure 1.

Top ten malware discovered in Q3 of 2022.

Figure 2.

Banking malware attacks detected in Q3 of 2022.

Figure 2.

Banking malware attacks detected in Q3 of 2022.

Figure 3.

Banking malware tree.

Figure 3.

Banking malware tree.

Figure 4.

Banking malware timeline.

Figure 4.

Banking malware timeline.

Figure 5.

Artificial Intelligence and related fields.

Figure 5.

Artificial Intelligence and related fields.

Figure 6.

Machine learning approaches with example algorithms.

Figure 6.

Machine learning approaches with example algorithms.

Figure 7.

System Architecture.

Figure 7.

System Architecture.

Figure 8.

Methodology for collecting and preparing the data.

Figure 8.

Methodology for collecting and preparing the data.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the prediction results for all three ML algorithms.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the prediction results for all three ML algorithms.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the prediction results for all three ML algorithms.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the prediction results for all three ML algorithms.

Figure 11.

Malware precision and recall scores.

Figure 11.

Malware precision and recall scores.

Figure 12.

Benign precision and recall scores.

Figure 12.

Benign precision and recall scores.

Figure 13.

Accuracy comparison across all the algorithms.

Figure 13.

Accuracy comparison across all the algorithms.

Table 1.

Test results from [

34] when using the SVM ML algorithm.

Table 1.

Test results from [

34] when using the SVM ML algorithm.

| Classifier |

Classification Results

FP |

FN |

Accuracy |

| Kstar |

0.275 |

0.026 |

88.69 |

| J48 |

0.156 |

0.026 |

92.84 |

| DT |

0.14 |

0.031 |

97.47 |

Table 2.

Test results from [

35] when using an unsupervised ML algorithm.

Table 2.

Test results from [

35] when using an unsupervised ML algorithm.

| |

FP |

TN |

FP |

FN |

Accuracy |

| Zeus 1 |

14,678 |

4352 |

969 |

1 |

0.9515 |

| Zeus 2 |

14,663 |

4341 |

991 |

5 |

0.9502 |

| Waledac 1 |

14,536 |

4500 |

963 |

1 |

0.9518 |

| Waledac 2 |

14,521 |

4525 |

963 |

1 |

0.9523 |

| Storm 1 |

10,139 |

4499 |

501 |

1386 |

0.8858 |

| Storm 2 |

2300 |

503 |

247 |

3 |

0.9181 |

Table 3.

Test results from [

35] when using an unsupervised ML algorithm.

Table 3.

Test results from [

35] when using an unsupervised ML algorithm.

| Botnet |

Average Detection Rate |

Average False Alarm Rate |

| HTTP-based |

0.95 |

0.041 |

| IRC-based |

0.96 |

0.033 |

| P2P-based |

0.91 |

0.037 |

Table 4.

Datasets used in this research.

Table 4.

Datasets used in this research.

| Dataset type |

Malware Name/Year |

Number of flows |

Name of dataset for this paper |

Malware

Benign |

Zeus/2019 |

66009 |

Dataset1 |

| N/A |

66009 |

Malware

Benign |

Zeus/2019 |

38282 |

Dataset2 |

| N/A |

38282 |

Malware

Benign |

Zeus/2022 |

272425 |

Dataset3 |

| N/A |

272425 |

Malware

Benign |

ZeusPanda/2022 |

11864 |

Dataset4 |

| N/A |

11864 |

Malware

Benign |

Ramnit/2022 |

10204 |

Dataset5 |

| N/A |

10204 |

Malware

Benign |

Dridex/2018 |

134998 |

Dataset6 |

| N/A |

134998 |

Table 5.

Confusion matrix that will be used to measure the detection accuracy.

Table 5.

Confusion matrix that will be used to measure the detection accuracy.

| |

Predicted Benign |

Predicted Zeus |

| Actual Benign (Total) |

TN |

FP |

| Actual Zeus (Total) |

FN |

TP |

Table 6.

Testing results when using the decision tree ML algorithm.

Table 6.

Testing results when using the decision tree ML algorithm.

| Dataset Name |

Malware

Precision Score |

Malware

Recall Score |

Malware

f1-score |

Benign

Precision Score |

Benign

Recall Score |

Benign

f1-score |

| Dataset1 |

1.00 |

0.95 |

0.97 |

0.95 |

1.00 |

0.97 |

| Dataset2 |

1.00 |

0.95 |

0.97 |

0.96 |

1.00 |

0.98 |

| Dataset3 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

| Dataset4 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

| Dataset5 |

0.87 |

0.97 |

0.92 |

0.97 |

0.86 |

0.91 |

| Dataset6 |

0.78 |

0.66 |

0.71 |

0.70 |

0.82 |

0.76 |

Table 7.

Confusion matrices depicting the testing results of the decision tree ML algorithm.

Table 7.

Confusion matrices depicting the testing results of the decision tree ML algorithm.

| Dataset Name |

Malware

Total

Samples

Tested |

Malware

Samples

Classified

Correctly |

Malware

Samples

Classified

Incorrectly |

Total

Benign

Samples

Tested |

Benign

Samples

Classified

Correctly |

Benign

Samples

Classified

Incorrectly |

| Dataset1 |

66009 |

62906 |

3103 |

66009 |

65722 |

287 |

| Dataset2 |

38282 |

36519 |

1763 |

38282 |

38152 |

130 |

| Dataset3 |

272425 |

270328 |

2097 |

272425 |

271439 |

986 |

| Dataset4 |

11864 |

11728 |

136 |

11864 |

11820 |

44 |

| Dataset5 |

10204 |

9941 |

263 |

10204 |

8759 |

1445 |

| Dataset6 |

134998 |

88500 |

46498 |

134998 |

110167 |

24831 |

Table 8.

Testing results when using the random forest ML algorithm.

Table 8.

Testing results when using the random forest ML algorithm.

| Dataset Name |

Malware

Precision Score |

Malware

Recall Score |

Malware

f1-score |

Benign

Precision Score |

Benign

Recall Score |

Benign

f1-score |

| Dataset1 |

1.00 |

0.95 |

0.97 |

0.95 |

1.00 |

0.97 |

| Dataset2 |

1.00 |

0.95 |

0.97 |

0.96 |

1.00 |

0.98 |

| Dataset3 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

| Dataset4 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

| Dataset5 |

0.87 |

0.97 |

0.92 |

0.97 |

0.86 |

0.91 |

| Dataset6 |

0.78 |

0.66 |

0.71 |

0.70 |

0.82 |

0.76 |

Table 9.

Confusion matrices depicting the testing results of the random forest ML algorithm.

Table 9.

Confusion matrices depicting the testing results of the random forest ML algorithm.

| Dataset Name |

Total

Malware

Samples

Tested |

Malware

Samples

Classified

Correctly |

Malware

Samples

Classified

Incorrectly |

Total

Benign

Samples

Tested |

Benign

Samples

Classified

Correctly |

Benign

Samples

Classified

Incorrectly |

| Dataset1 |

66009 |

65051 |

958 |

66009 |

66003 |

6 |

| Dataset2 |

38282 |

37737 |

545 |

38282 |

38278 |

4 |

| Dataset3 |

272425 |

272276 |

149 |

272425 |

272401 |

24 |

| Dataset4 |

11864 |

11758 |

106 |

11864 |

11863 |

1 |

| Dataset5 |

10204 |

9990 |

214 |

10204 |

8852 |

1352 |

| Dataset6 |

134998 |

88586 |

46412 |

134998 |

111428 |

23570 |

Table 10.

Testing results when using the k-nearest neighbor (KNN) ML algorithm.

Table 10.

Testing results when using the k-nearest neighbor (KNN) ML algorithm.

| Dataset Name |

Malware

Precision Score |

Malware

Recall Score |

Malware

f1-score |

Benign

Precision Score |

Benign

Recall Score |

Benign

f1-score |

| Dataset1 |

1.00 |

0.90 |

0.95 |

0.91 |

1.00 |

0.95 |

| Dataset2 |

1.00 |

0.91 |

0.95 |

0.91 |

1.00 |

0.95 |

| Dataset3 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Dataset4 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

| Dataset5 |

0.92 |

0.97 |

0.95 |

0.97 |

0.92 |

0.95 |

| Dataset6 |

0.85 |

0.50 |

0.63 |

0.65 |

0.91 |

0.76 |

Table 11.

Confusion matrices depicting the testing results of the random forest ML algorithm.

Table 11.

Confusion matrices depicting the testing results of the random forest ML algorithm.

| Dataset Name |

Total

Malware

Samples

Tested |

Malware

Samples

Classified

Correctly |

Malware

Samples

Classified

Incorrectly |

Total

Benign

Samples

Tested |

Benign

Samples

Classified

Correctly |

Benign

Samples

Classified

Incorrectly |

| Dataset1 |

66009 |

59476 |

6533 |

66009 |

66003 |

6 |

| Dataset2 |

38282 |

34659 |

3623 |

38282 |

38278 |

4 |

| Dataset3 |

272425 |

272423 |

2 |

272425 |

272401 |

24 |

| Dataset4 |

11864 |

11719 |

145 |

11864 |

11863 |

1 |

| Dataset5 |

10204 |

9939 |

265 |

10204 |

9397 |

807 |

| Dataset6 |

134998 |

68156 |

66842 |

134998 |

123232 |

11766 |

Table 12.

Testing results when using the random forest ML algorithm.

Table 12.

Testing results when using the random forest ML algorithm.

| Dataset Name |

Malware

Precision Score |

Malware

Recall Score |

Malware

f1-score |

Benign

Precision Score |

Benign

Recall Score |

Benign

f1-score |

| Dataset1 |

1.00 |

0.95 |

0.97 |

0.95 |

1.00 |

0.97 |

| Dataset2 |

1.00 |

0.95 |

0.97 |

0.96 |

1.00 |

0.98 |

| Dataset3 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

| Dataset4 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

| Dataset5 |

0.87 |

0.97 |

0.92 |

0.97 |

0.86 |

0.91 |

| Dataset6 |

0.78 |

0.66 |

0.71 |

0.70 |

0.82 |

0.76 |

Table 13.

Confusion matrices depicting the testing results of the random forest ML algorithm.

Table 13.

Confusion matrices depicting the testing results of the random forest ML algorithm.

| Dataset Name |

Total

Malware

Samples

Tested |

Malware

Samples

Classified

Correctly |

Malware

Samples

Classified

Incorrectly |

Total

Benign

Samples

Tested |

Benign

Samples

Classified

Correctly |

Benign

Samples

Classified

Incorrectly |

| Dataset1 |

66009 |

65051 |

958 |

66009 |

66003 |

6 |

| Dataset2 |

38282 |

37737 |

545 |

38282 |

38278 |

4 |

| Dataset3 |

272425 |

272276 |

149 |

272425 |

272401 |

24 |

| Dataset4 |

11864 |

11758 |

106 |

11864 |

11863 |

1 |

| Dataset5 |

10204 |

9990 |

214 |

10204 |

8852 |

1352 |

| Dataset6 |

134998 |

88586 |

46412 |

134998 |

111428 |

23570 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).