Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

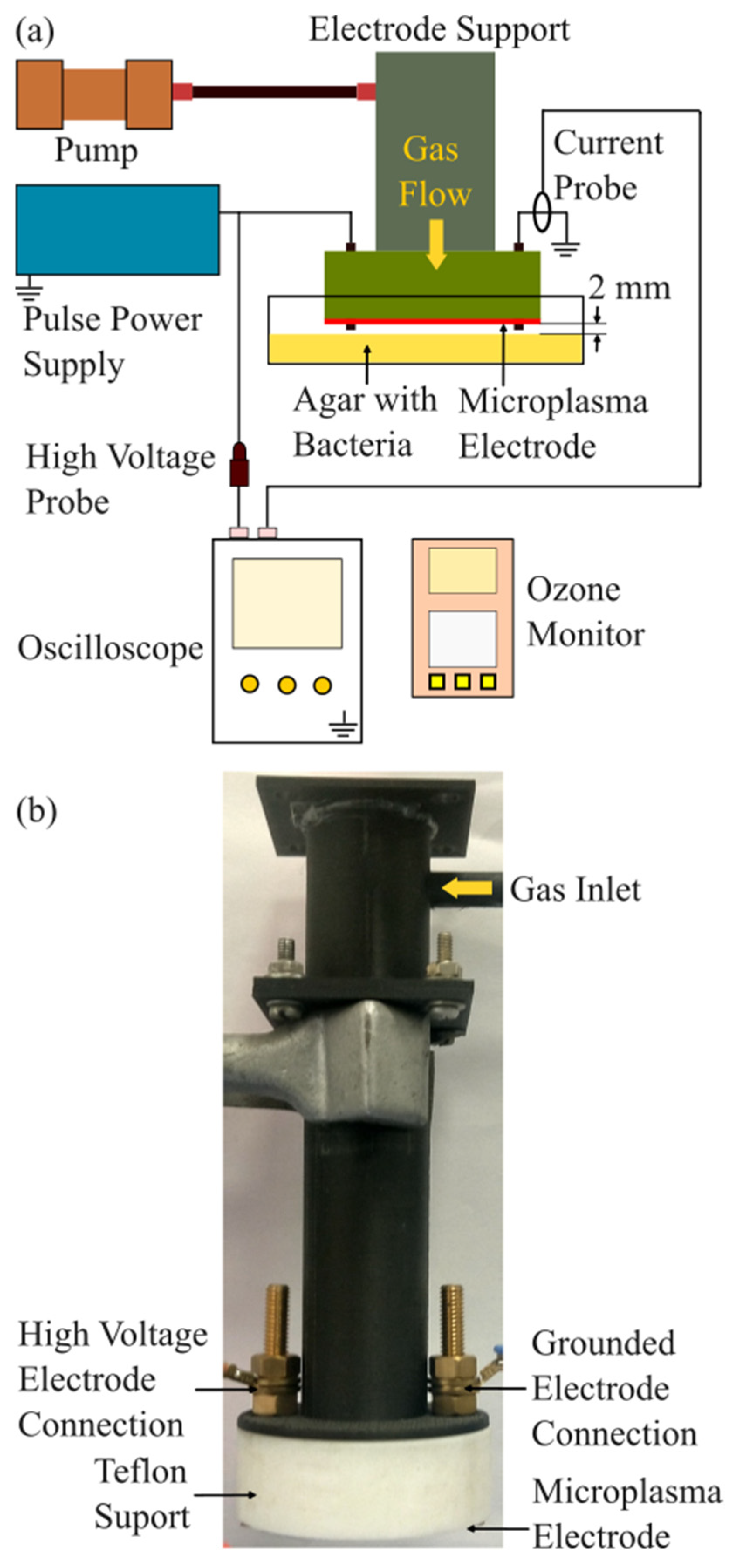

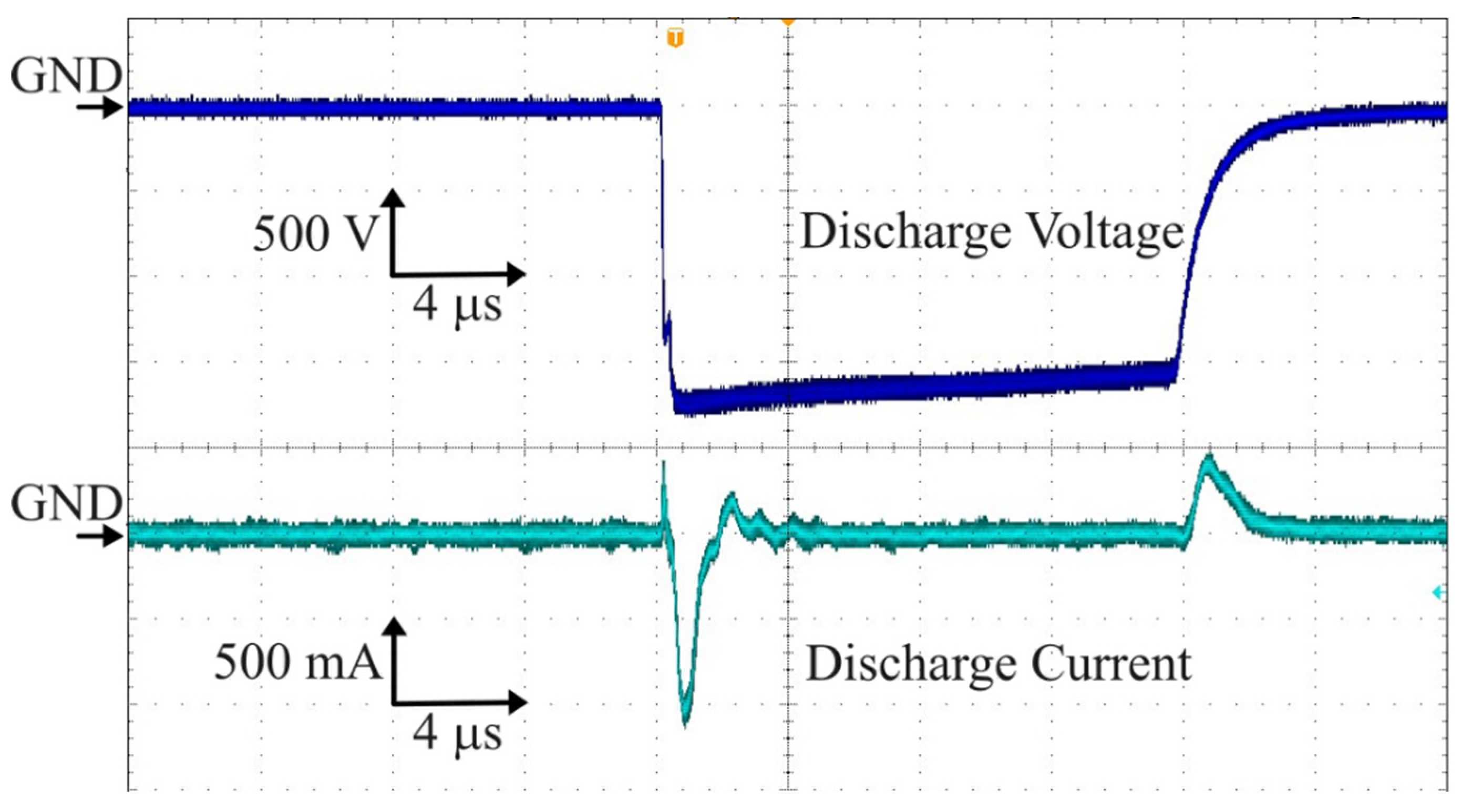

2.1. Experimental Setup

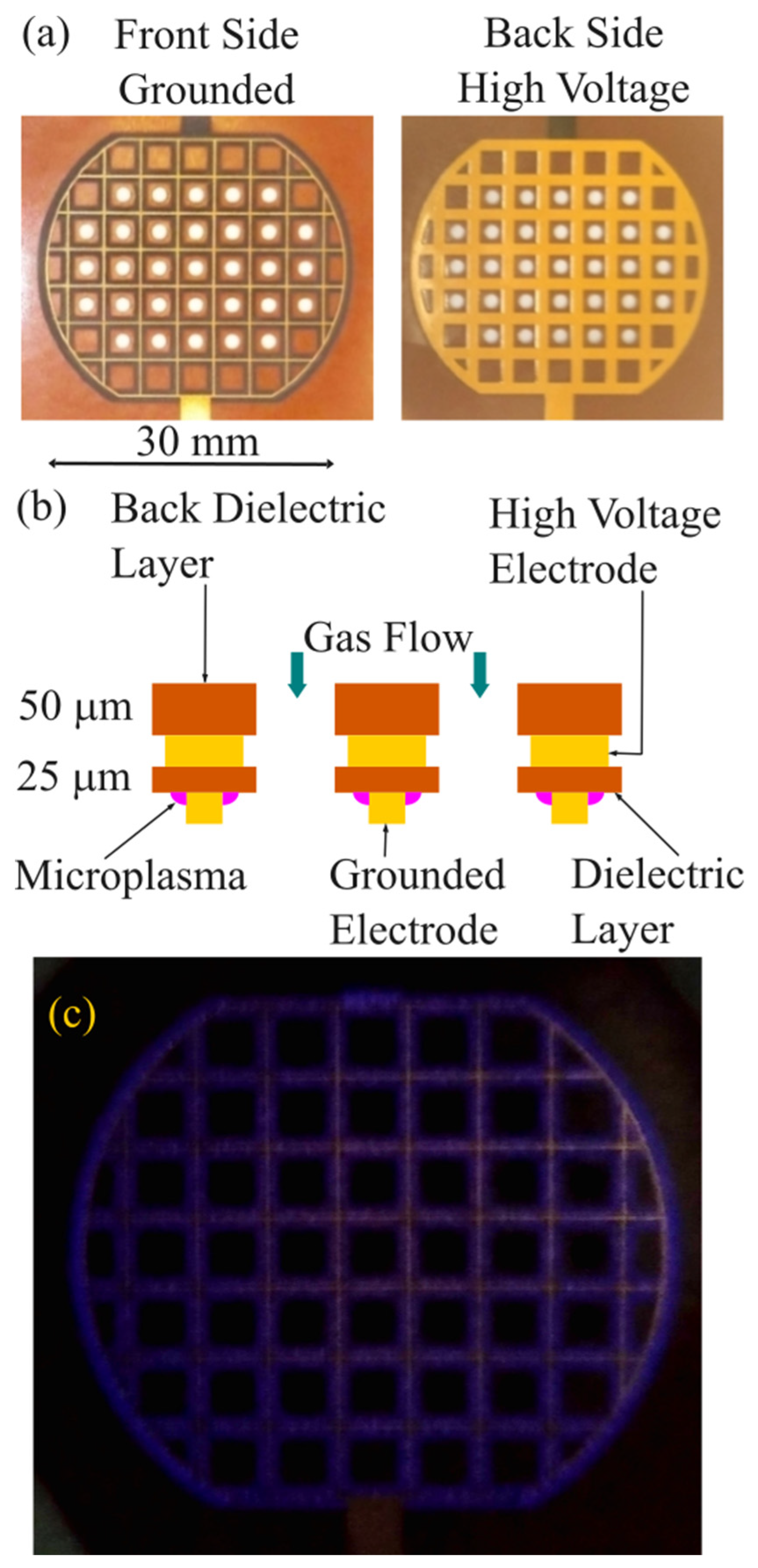

2.2. Microplasma Electrode

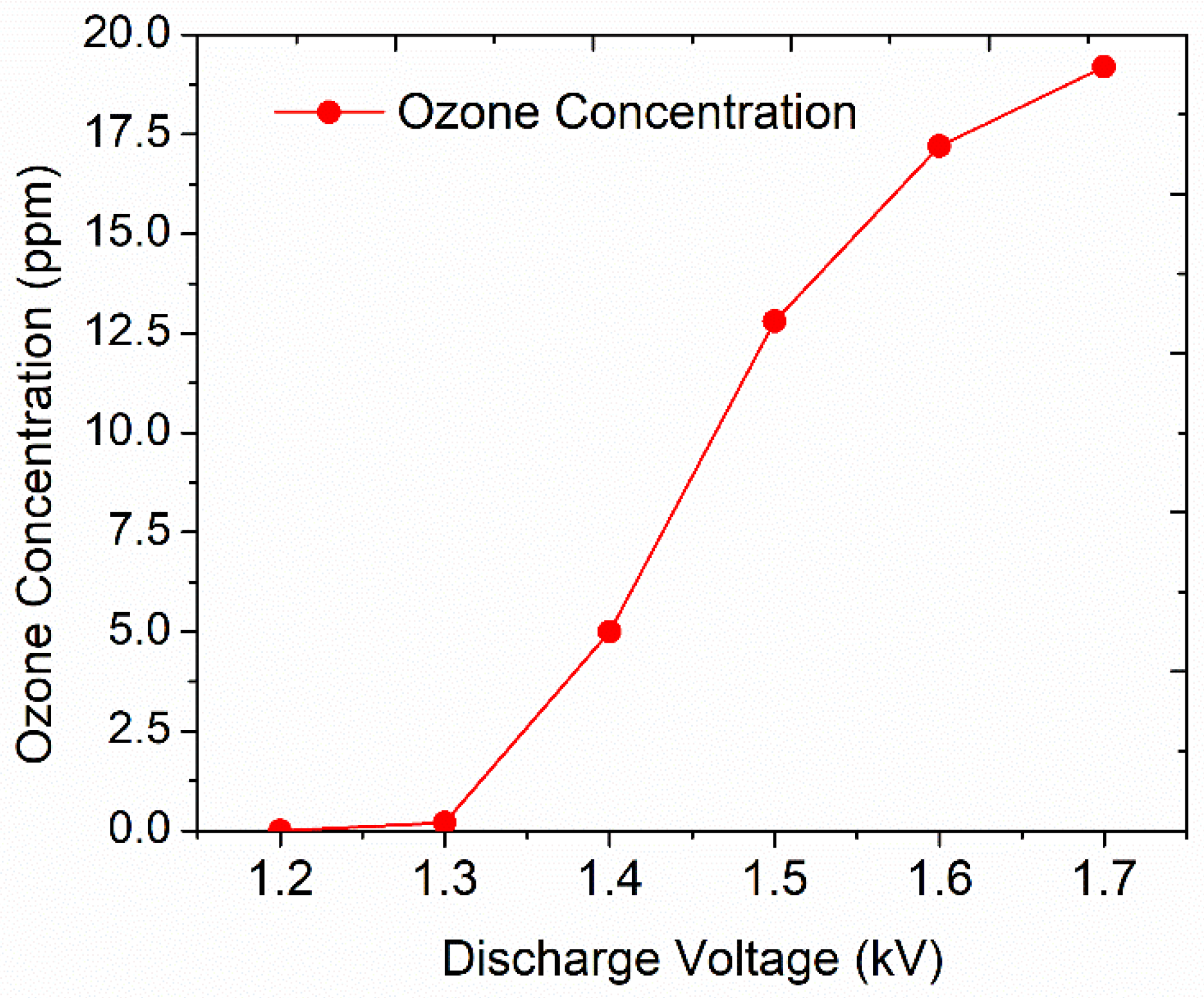

2.3. Ozone Generation

2.4. Microbiology Assay

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Blajan, M., Mizuno, Y., Ito, A., Shimizu, K., 2016. Microplasma actuator for EHD induced flow. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 53, 2409–2415. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K., Mizuno, Y., Blajan, M., Yoneda, H., 2016. Characteristics of an atmospheric nonthermal microplasma actuator. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 53, 1452–1458. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K., Ishii, T., Blajan, M., 2010a. Emission spectroscopy of pulsed power microplasma for atmospheric pollution control. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 46, 1125–1131.

- Shimizu, K., Blajan, M., Kuwabara, T., 2011. Removal of indoor air contaminant by atmospheric microplasma. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 47, 2351–2358.

- Blajan, M., Umeda, A., Muramatsu, S., Shimizu, K., 2011. Emission spectroscopy of pulsed powered microplasma for surface treatment of PEN film. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 47, 1100–1108.

- Shimizu, K., Umeda, A., Muramatsu, S., Blajan, M., 2010b. Basic study on surface treatment of functional resin film by pulsed atmospheric microplasma. IEEJ Transactions on Fundamentals and Materials 130, 858–864.

- Shimizu, K., Umeda, A., Blajan, M., 2011. Surface treatment of polymer film by atmospheric pulsed microplasma: Study on gas humidity effect for improving the hydrophilic property. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 50, 08KA03.

- Shimizu, K., Yamada, M., Kanamori, M., Blajan, M., 2010. Basic study of bacteria inactivation at low discharge voltage by using microplasmas. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 46, 641–649.

- Shimizu, K., Kristof, J., Blajan, M.G., 2019. Applications of dielectric barrier discharge microplasma. In: IntechOpen eBooks. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Kang, Z., Jiang, E., Song, R., Zhang, Y., Qu, G., Wang, T., Jia, H., Zhu, L., 2021. Plasma induced efficient removal of antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli and antibiotic resistance genes, and inhibition of gene transfer by conjugation. Journal of Hazardous Materials 419, 126465.

- Zhang, A., Jiang, X., Ding, Y., Jiang, N., Ping, Q., Wang, L., Liu, Y., 2023. Simultaneous removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater by a novel nonthermal plasma/peracetic acid combination system: Synergistic performance and mechanism. Journal of Hazardous Materials 452, 131357.

- Li, H., Zhang, R., Zhang, J., Wang, Q., Wang, Y., Zhou, J., Wang, T., 2023. Conjugation transfer of plasma-induced sublethal antibiotic resistance genes under photoreactivation: Alleviation mechanism of intercellular contact. Journal of Hazardous Materials 455, 131620.

- Ehlbeck, J., Schnabel, U., Polak, M., Winter, J., Von Woedtke, T., Brandenburg, R., Von Dem Hagen, T., Weltmann, K., 2010. Low temperature atmospheric pressure plasma sources for microbial decontamination. Journal of Physics D Applied Physics 44, 013002.

- Weltmann, K.-D., Polak, M., Masur, K., Von Woedtke, T., Winter, J., Reuter, S., 2012. Plasma processes and plasma sources in medicine. Contributions to Plasma Physics 52, 644–654. [CrossRef]

- Weltmann, K.-D., Kindel, E., Von Woedtke, T., Hähnel, M., Stieber, M., Brandenburg, R., 2010. Atmospheric-pressure plasma sources: Prospective tools for plasma medicine. Pure and Applied Chemistry 82, 1223–1237. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T., Fu, S., Xie, W., Li, F., Liu, Y., 2024. Comparison of inactivation characteristics of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus in water by rotary plasma jet sterilization. Environmental Technology & Innovation 36, 103746.

- Juozaitienė, V., Jonikė, V., Mardosaitė-Busaitienė, D., Griciuvienė, L., Kaminskienė, E., Radzijevskaja, J., Venskutonis, V., Riškevičius, V., Paulauskas, A., 2024. Application of cold plasma therapy for managing subclinical mastitis in cows induced by Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus uberis and Escherichia coli. Veterinary and Animal Science 25, 100378.

- Wang, Q., Lavoine, N., Salvi, D., 2022. Cold atmospheric pressure plasma for the sanitation of conveyor belt materials: Decontamination efficacy against adherent bacteria and biofilms of Escherichia coli and effect on surface properties. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 84, 103260.

- Gershman, S., Harreguy, M.B., Yatom, S., Raitses, Y., Efthimion, P., Haspel, G., 2021. A low power flexible dielectric barrier discharge disinfects surfaces and improves the action of hydrogen peroxide. Scientific Reports 11. [CrossRef]

- Mosaka, T.B.M., Unuofin, J.O., Daramola, M.O., Tizaoui, C., Iwarere, S.A., 2024. Rapid susceptibility of Carbapenem resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its resistance gene to non-thermal plasma treatment in a batch reactor. Journal of Water Process Engineering 65, 105915.

- Zhao, Y., Shao, L., Duan, M., Liu, Y., Sun, Y., Zou, B., Wang, H., Dai, R., Li, X., Jia, F., 2024. TMT-based quantitative proteomics and non-targeted metabolomic analyses reveal the inactivation mechanism of cold atmospheric plasma against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Food Control 165, 110608.

- Zhao, Y., Shao, L., Jia, L., Zou, B., Dai, R., Li, X., Jia, F., 2022. Inactivation effects, kinetics and mechanisms of air- and nitrogen-based cold atmospheric plasma on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 79, 103051.

- Blajan, M.G., Yahaya, A.G., Kristof, J., Okuyama, T., Shimizu, K., 2022. Inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus by microplasma. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 59, 434–440. [CrossRef]

- Liao, X., Xiang, Q., Liu, D., Chen, S., Ye, X., Ding, T., 2017b. Lethal and Sublethal Effect of a Dielectric Barrier Discharge Atmospheric Cold Plasma on Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Food Protection 80, 928–932. [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.-S., Jeon, E.B., Kim, J.Y., Choi, E.H., Lim, J.S., Choi, J., Park, S.Y., 2020. Impact of non-thermal dielectric barrier discharge plasma on Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus and quality of dried blackmouth angler (Lophiomus setigerus). Journal of Food Engineering 278, 109952. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Hong, F., Guo, Y., Zhang, J., Shi, J., 2013. Sterilization of Staphylococcus aureus by an atmospheric Non-Thermal plasma jet. Plasma Science and Technology 15, 439–442. [CrossRef]

- Cotter, J.J., Maguire, P., Soberon, F., Daniels, S., O’Gara, J.P., Casey, E., 2011. Disinfection of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms using a remote non-thermal gas plasma. Journal of Hospital Infection 78, 204–207. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Sun, P., Wu, H., Bai, N., Wang, R., Zhu, W., Zhang, J., Liu, F., 2010. Inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis by a direct-current, cold atmospheric-pressure air plasma microjet. Journal of Biomedical Research 24, 264–269.

- Yoo, J.H., Baek, K.H., Heo, Y.S., Yong, H.I., Jo, C., 2020. Synergistic bactericidal effect of clove oil and encapsulated atmospheric pressure plasma against Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Staphylococcus aureus and its mechanism of action. Food Microbiology 93, 103611. [CrossRef]

- Korachi, M., Gurol, C., Aslan, N., 2010. Atmospheric plasma discharge sterilization effects on whole cell fatty acid profiles of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Electrostatics 68, 508–512. [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.H., Ki, S.H., Ahn, J.H., Shin, J.H., Hong, E.J., Kim, Y.J., Choi, E.H., 2018. Inactivation of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus on contaminated perilla leaves by Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) plasma treatment. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 643, 32–41. [CrossRef]

- Han, L., Patil, S., Boehm, D., Milosavljević, V., Cullen, P.J., Bourke, P., 2015. Mechanisms of Inactivation by High-Voltage Atmospheric Cold Plasma Differ for Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 82, 450–458. [CrossRef]

- Kondeti, V.S.S.K., Phan, C.Q., Wende, K., Jablonowski, H., Gangal, U., Granick, J.L., Hunter, R.C., Bruggeman, P.J., 2018. Long-lived and short-lived reactive species produced by a cold atmospheric pressure plasma jet for the inactivation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 124, 275–287. [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, D.L., Shama, G., Kong, M.G., 2013. Restoration of antibiotic sensitivity in meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus following treatment with a non-thermal atmospheric gas plasma. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 41, 398–399. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M., Zhuang, H., Zhao, J., Wang, J., Yan, W., Zhang, J., 2019. Differences in cellular damage induced by dielectric barrier discharge plasma between Salmonella Typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus. Bioelectrochemistry 132, 107445. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.G., Paff, M., Friedman, G., Fridman, G., Fridman, A., Brooks, A.D., 2010. Control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in planktonic form and biofilms: A biocidal efficacy study of nonthermal dielectric-barrier discharge plasma. American Journal of Infection Control 38, 293–301. [CrossRef]

- Liao, X., Li, J., Suo, Y., Ahn, J., Liu, D., Chen, S., Hu, Y., Ye, X., Ding, T., 2017a. Effect of preliminary stresses on the resistance of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus toward non-thermal plasma (NTP) challenge. Food Research International 105, 178–183. [CrossRef]

- Gök, V., Aktop, S., Özkan, M., Tomar, O., 2019. The effects of atmospheric cold plasma on inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus and some quality characteristics of pastırma—A dry-cured beef product. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 56, 102188. [CrossRef]

- Burts, M.L., Alexeff, I., Meek, E.T., McCullers, J.A., 2009. Use of atmospheric non-thermal plasma as a disinfectant for objects contaminated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. American Journal of Infection Control 37, 729–733. [CrossRef]

- Iza, F., Kim, G.J., Lee, S.M., Lee, J.K., Walsh, J.L., Zhang, Y.T., Kong, M.G., 2008. Microplasmas: sources, particle kinetics, and biomedical applications. Plasma Processes and Polymers 5, 322–344. [CrossRef]

- Heeren, T., Ueno, T., Wang, N.D., Namihira, T., Katsuki, S., Akiyama, H., 2005. Novel dual Marx Generator for microplasma applications. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 33, 1205–1209.

- Rusterholtz, D.L., Lacoste, D.A., Stancu, G.D., Pai, D.Z., Laux, C.O., 2013. Ultrafast heating and oxygen dissociation in atmospheric pressure air by nanosecond repetitively pulsed discharges. Journal of Physics D Applied Physics 46, 464010.

- Zhang, L., Wang, K., Wu, K., Guo, Y., Liu, Z., Yang, D., Zhang, W., Luo, H., Fu, Y., 2024. Air disinfection by nanosecond pulsed DBD plasma. Journal of Hazardous Materials 472, 134487. [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2020. Available online: http://www.eucast.org.

- Leclercq, R., Canton, R., Brown, D.F.J., Giske, C.G., Heisig, P., MacGowan, A.P., Kahlmeter, G. EUCAST expert rules in antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, 141–160. [PubMed]

- Matuschek, E., Brown, D.F.J., Kahlmeter, G. Development of the EUCAST disk diffusion antimicrobial susceptibility testing method and its implementation in routine microbiology laboratories. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, O255–O266. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldgy, A., Nayak, G., Aboubakr, H.A., Goyal, S.M., Bruggeman, P.J., 2020. Inactivation of virus and bacteria using cold atmospheric pressure air plasmas and the role of reactive nitrogen species. Journal of Physics D Applied Physics 53, 434004. [CrossRef]

- Morent, R., De, N., 2011. Inactivation of bacteria by Non-Thermal plasmas. In: InTech eBook, doi: 10.5772/1861. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/17641.

- Graves, D.B., 2012. The emerging role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in redox biology and some implications for plasma applications to medicine and biology. Journal of Physics D Applied Physics 45, 263001.

- Polito, J., Quesada, M.J.H., Stapelmann, K., Kushner, M.J., 2023. Reaction mechanism for atmospheric pressure plasma treatment of cysteine in solution. Journal of Physics D Applied Physics 56, 395205.

- Eliasson, B., Hirth, M., Kogelschatz, U., 1987. Ozone synthesis from oxygen in dielectric barrier discharges. Journal of Physics D Applied Physics 20, 1421–1437.

- Pejaković, D.A., Copeland, R.A., Cosby, P.C., Slanger, T.G., 2007. Studies on the production of O2(a1Δg, υ = 0) and O2(b1Σg+, υ = 0) from collisional removal of O2(A3Σu+, υ′ = 6–10). Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres 112. [CrossRef]

- Fridman, A., 2008. Plasma Biology and Plasma Medicine. In: Cambridge University Press eBooks. pp. 848–914. [CrossRef]

- Blajan, M., Nonaka, D., Kristof, J., Shimizu, K., 2019. Study of Induced EHD flow by microplasma vortex Generator. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 47, 5345–5354. [CrossRef]

- Sakiyama, Y., Graves, D.B., Chang, H.-W., Shimizu, T., Morfill, G.E., 2012. Plasma chemistry model of surface microdischarge in humid air and dynamics of reactive neutral species. Journal of Physics D Applied Physics 45, 425201. [CrossRef]

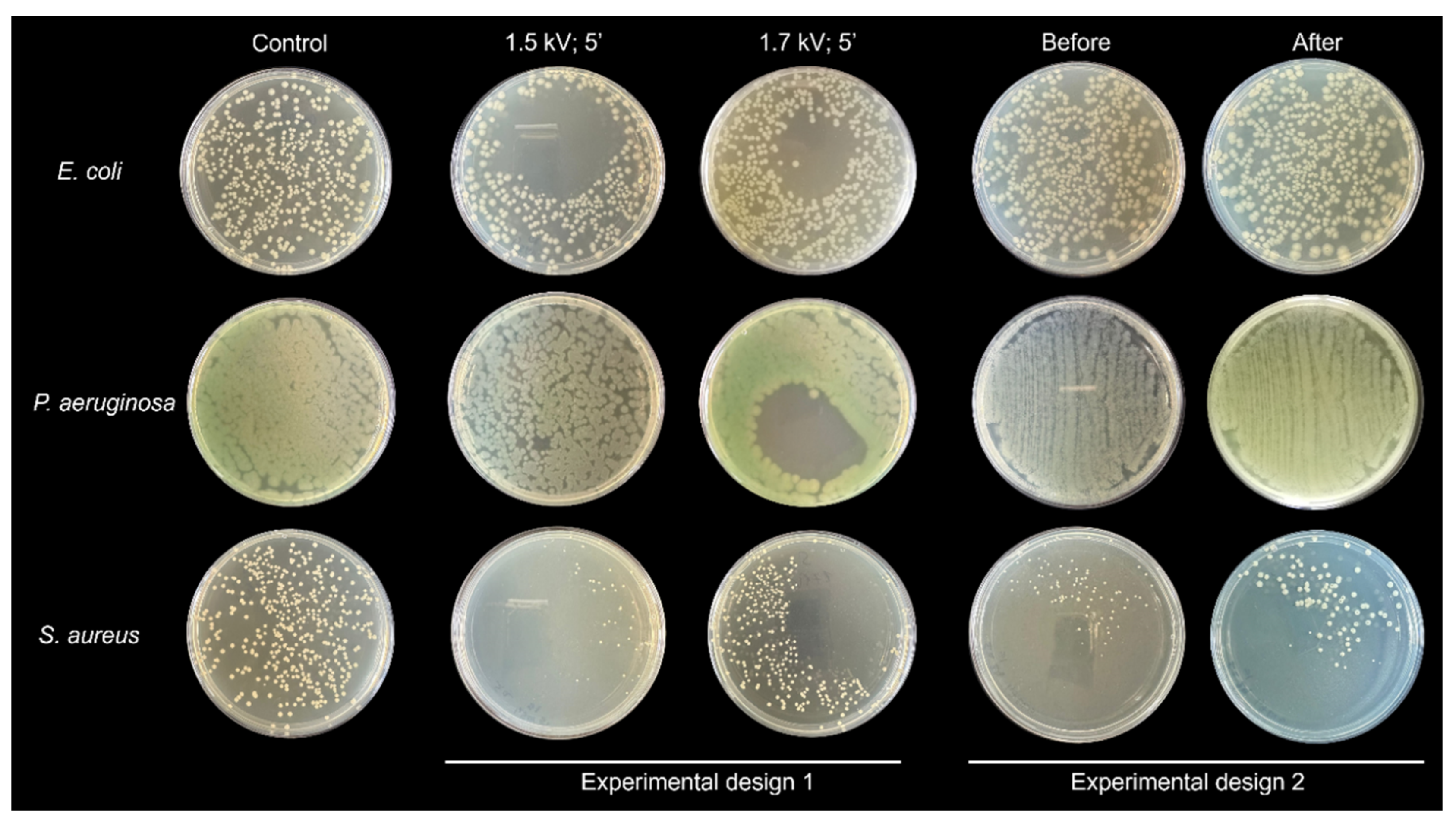

| CFU | ||||

| -1.5 kV | -1.7 kV | |||

| Treated | Control | Treated | Control | |

| E. coli | 279±77.7 | 348±44.6 | 222.5 ±13.4 | 348±44.6 |

| P. aeruginosa | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| S. aureus | 35.5±6.3 | 205±103.9 | 287 ±69.3 | 205±103.9 |

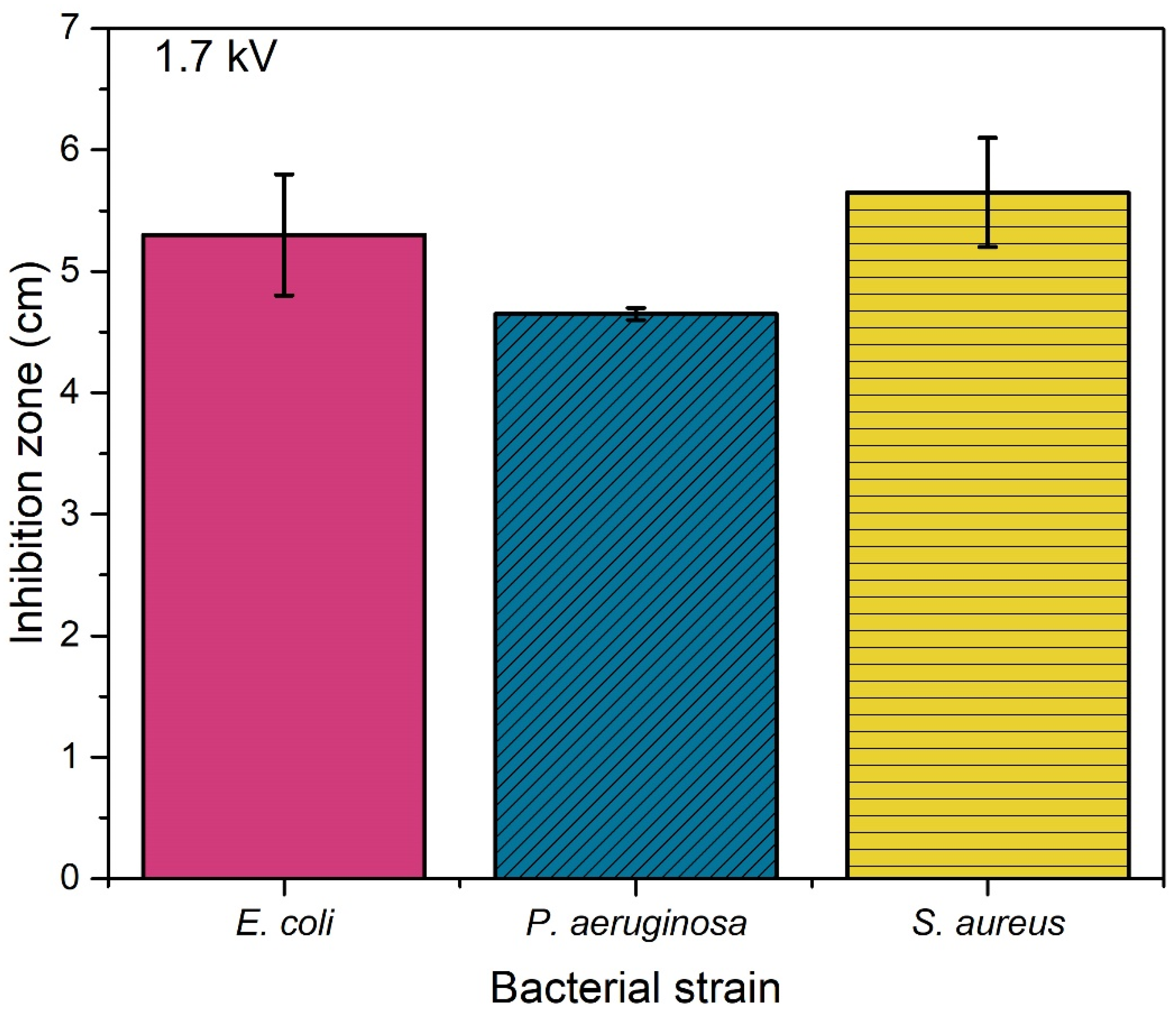

| D values | ||||||

| -1.5 kV | -1.7 kV | -1.7 kV 45 mm diameter area |

||||

| Bacterial liquid quantity | 50 µL (kJ/50 µL) | 1 mL (kJ/mL) | 50 µL (kJ/50 µL) | 1 mL (kJ/mL) | 50 µL (kJ/50 µL) | 1 mL (kJ/mL) |

| E. coli | 7.88 | 157.5 | 4.49 | 89.9 | 0.28 | 5.6 |

| P. aeruginosa | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| S. aureus | 0.99 kJ | 19.9 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).