1. Introduction

Rare earth elements (REEs) have some excellent chemical and physical properties, achieving its wide application in many fields, such as electronic components, national defense and aerospace [

1,

2,

3]. With the market demand increasing, the annual production of rare earth oxide has increased from 210,000 to 350,000 tons in the past 5 years [

4,

5], leading to an increase in rare earth secondary resources. Many conspicuous secondary resources belong to post-consumer recycling [

6], like waste permanent magnets and waste polishing powders [

7,

8,

9,

10], while in pre-consumer recycling field some resources, like red mud [

11,

12], have the potential to be recovered. Rare earth molten salt electrolysis slag was a typical one in pre-consumer recycling field.

The main rare earth production method is rare earth fluoride molten salt electrolysis.[

13] In this procedure, approximately 8% of REEs would remain in the REMES each year. [

14] Therefore, with the expansion of rare earth production, more REMES would be generated. Meanwhile, considering the abundance of Li and REEs in this secondary resource, [

15] it is essential to recycle it.

Mubula et al [

16] categorized the recovery methodologies of REMES into three types, including alkali mineral phase reconstruction methods, salt mineral phase reconstruction methods and acid mineral phase reconstruction methods. Yang et al [

17] utilized sodium hydroxide to reconstruct the phase of rare earth compounds and lithium fluoride, transforming them into hydroxides. After washing and leaching treatments, the optimal leaching efficiency of rare earths, fluorine and lithium were 99.05%, 98.23% and 99.22%. Yang [

18] utilized borax to reconstruct REMES, generating rare earth oxides and sodium fluoride. After washing and leaching, the leaching efficiency of REEs exceeded 97%. Tian et al [

19] invented a method reconstructing REMES by concentrated sulfuric acid. During the phase reconstruction process, the rare earth compounds and lithium fluoride were changed into sulfuric salt, HF released and collected in this period. Then, the HF was utilized to produce hydrofluoric acid, which precipitated the rare earth fluorides and lithium fluoride from the leaching lixivium. In this method, more than 90% of REEs, Li and F could be recovered.

The diversity of phase reconstruction methods were the core treatments on the recovery of REMES and the defluorination of rare earth compounds at the initial step was the main purpose of phase reconstruction.[

20] With the development of the methodologies, many issues have been handled, such as the recovery of Lithium and the increase of resource utilization rate. Besides, because of the defluorination process, the hydrometallurgical process was the main purification method. [

21] This would result in waste water problems and long production process

Lai [

22] attempted to apply vacuum distillation method into the recovery of REMES, while vacuum distillation was only utilized to extract LiF. Considering the volatility of rare earth fluoride, if the rare earth compounds could be fluorinated, vacuum distillation might be a potential method to recover REEs with no waste water generation, achieving the environmentally friendly resources recovery. Therefore, this paper investigated the feasibility and obstacles on the recovery of REEs by vacuum distillation as well as the fluorination of REMES.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Equipment

This REMES was obtained from a rare earth factory in Jiangxi Province of China. NH4HF2 (98.5%, AR, Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd) was selected as the fluorination reagent. The facility in this study is a self-made vertical furnace. The furnace is composed of a cylindrical alundum tube, heating system and vacuum system. The heating system consists of 6 pieces of silicon carbide rods which are set around the alundum tube. The function of vacuum system is provided by a vacuum pump called “First FX 32”.

2.2. Experimental Process

Initially, the phase change of rare earth fluoride in the REMES under the vacuum and high temperature conditions was investigated. The REMES was compacted as a block and set at the center of the vertical vacuum distillation furnace. Then, many the REMES blocks with same mass were distilled at different temperature for different time, respectively. Based on the distillation results, the possible phase change in the high-temperature and vacuum environment was analyzed. According to the results of the phase transition investigation, the fluorination of REMES was studied. NH

4HF

2 would react with REMES in an airtight furnace. After reaction, the fluorinated REMES would be distilled to prove the availability of the fluorination and vacuum distillation. The recovery efficiencies of REEs and Li were calculated by Equation. (1), using the recovery efficiency of REEs as an example.

where

represents the recovery of REEs, %;

is the content of total REO in the distillation residue, %;

is the mass of the distillation residue, g;

represents the content of total REO, %;

is the mass of the raw material, g.

2.3. Characterization and Analytical Methods

The differential scanning calorimetry and thermo-gravimetric analysis were carried out by SDT on the atmosphere of N2 (TA Q600, TA, America). The phase analysis of the sample was conducted by X-ray diffractometer (D8 Advance, Bruker, Germany; ultima IV, Ragiku, Japan). Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (PE optima 8300DV, PerkinElmer, America) was employed to analyze the concentration of Li. The XPS analysis was conducted by Thermo SCIENTIFIC ESCALAB 250Xi (Thermo Fisher Scientific, America). The shift due to charge accumulation was corrected using the binding energy of a mixture of C 1s set to 284.8eV as a reference. The content of total REEs was analyzed by the chemical method.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Analysis of Raw Material

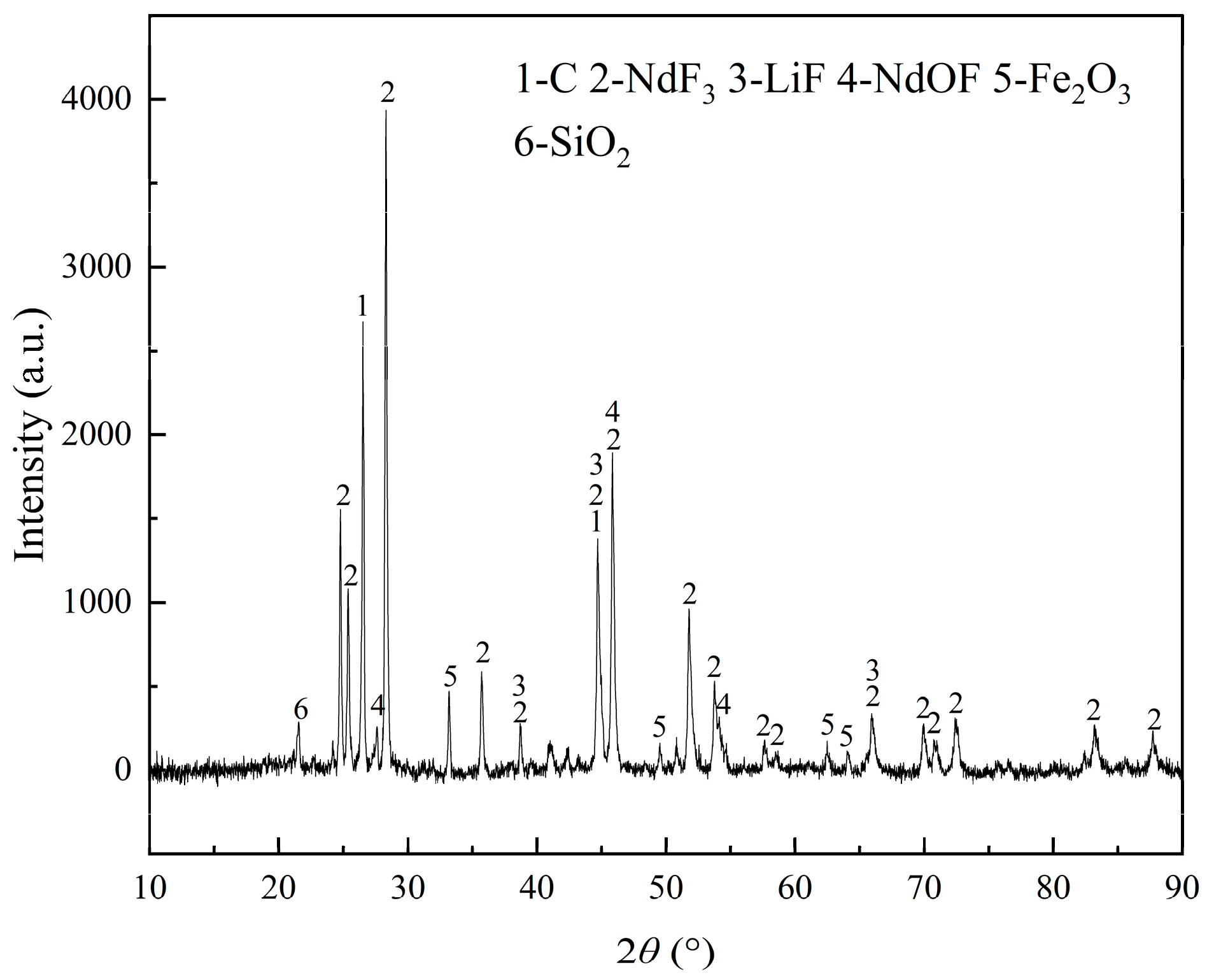

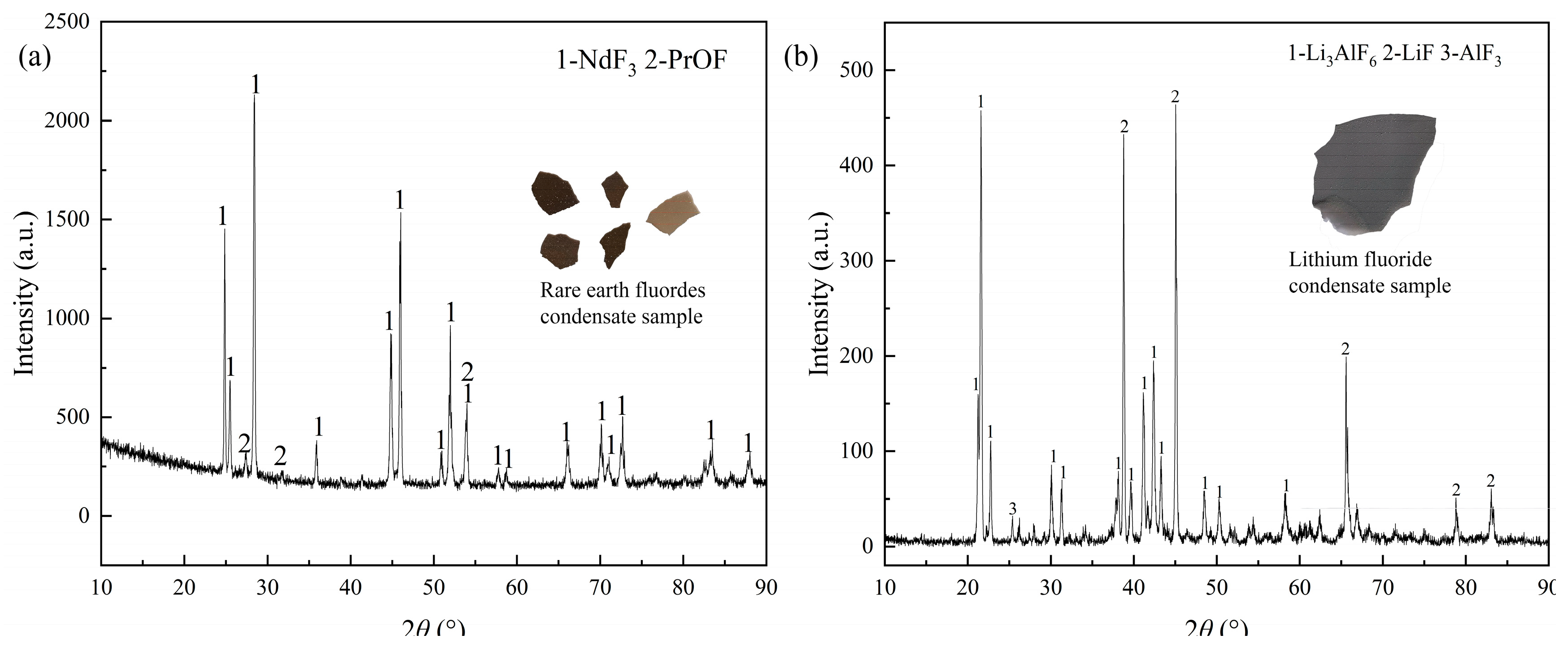

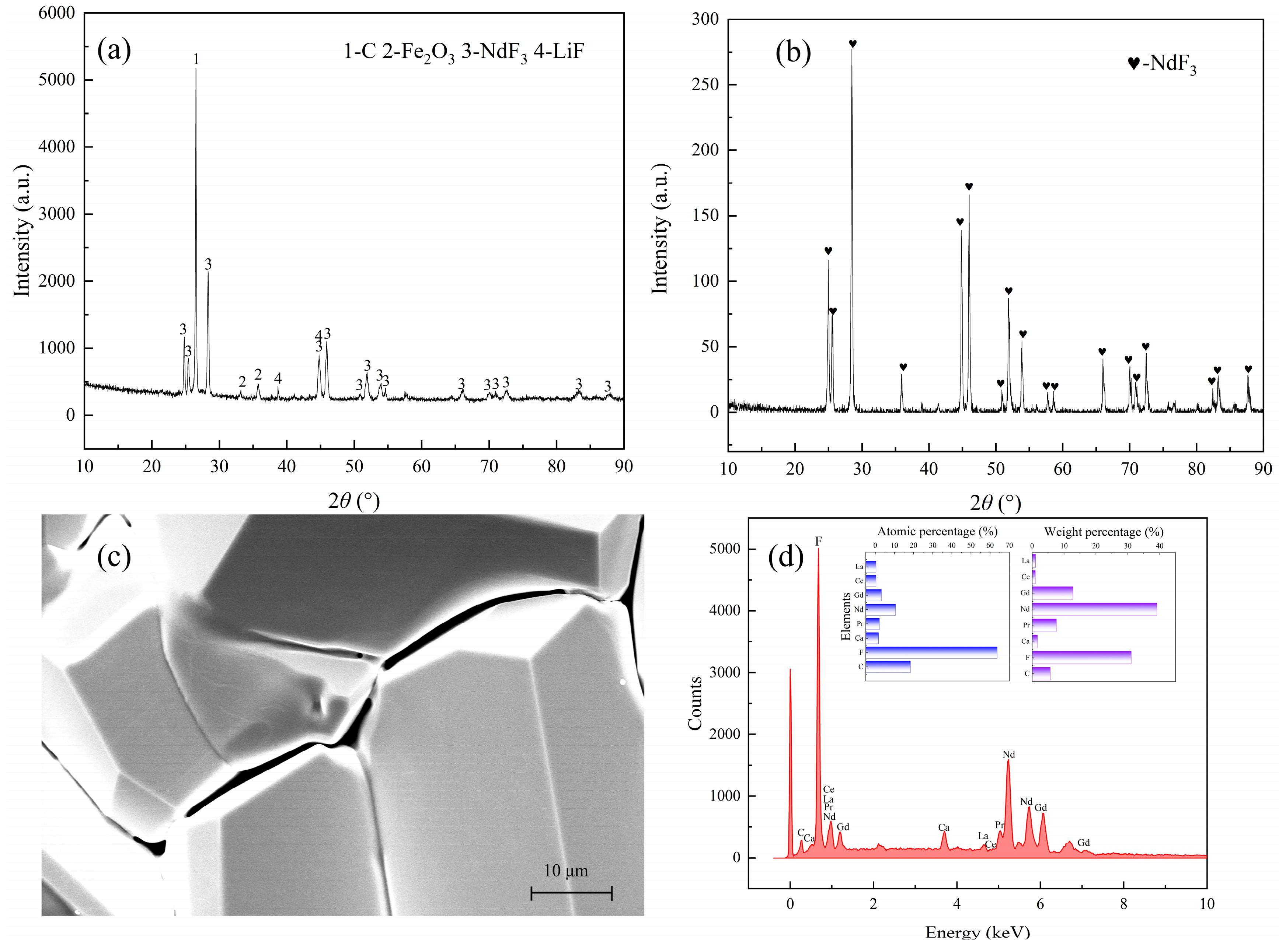

The composition of REMES is displayed in

Table 1 and

Table 2. In this slag, Nd, Pr and Gd are the major REEs. Additionally, according to

Figure 1, neodymium fluoride is the major phase of REEs and neodymium oxyfluoride also exists in the slag, while oxide impurities, including Fe

2O

3 and SiO

2, are discovered. In

Figure 2, the XPS analysis illustrated neodymium compounds were mainly composed of NdF

3 and gadolinium is combined with both O and F, while praseodymium is combined with O. Notably, the XRD pattern shows no peak of Al, while the XPS result displays the peak of Al

2O

3, which might be caused by the detection limit of XRD.

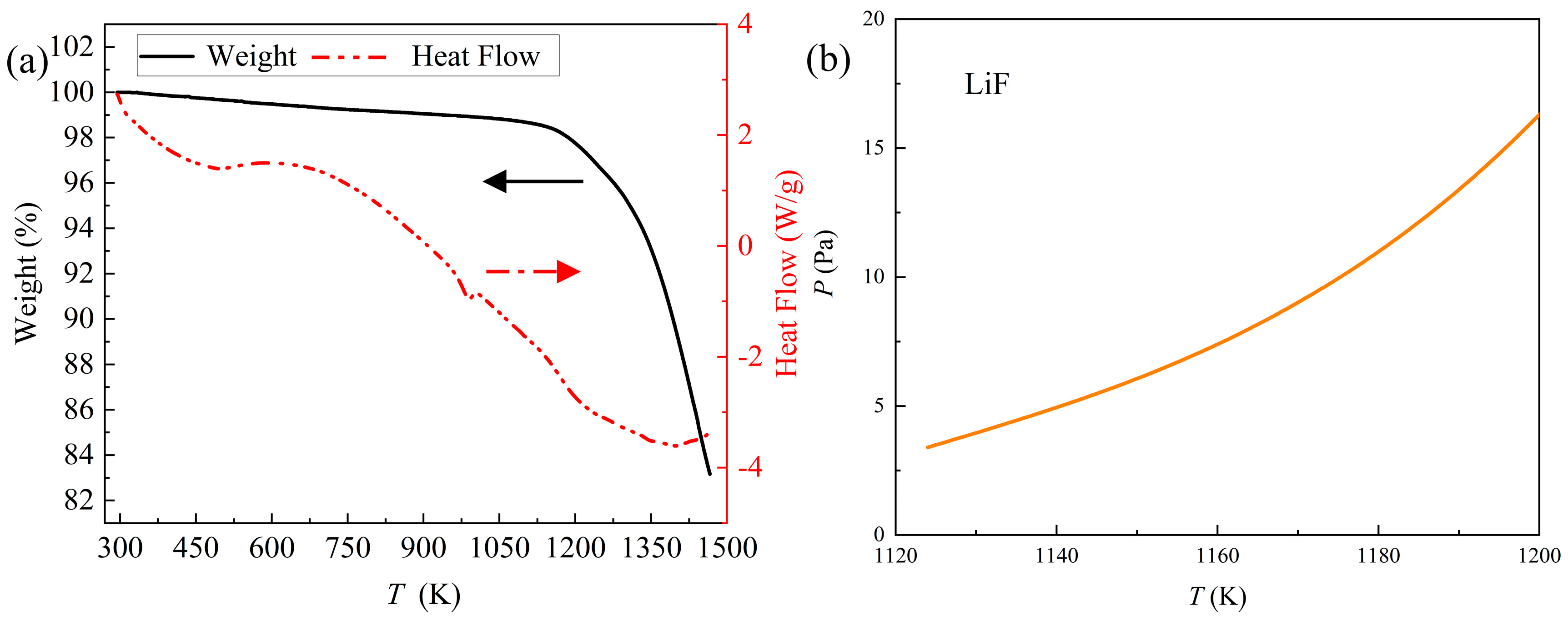

To determine the distillation temperature, TG-DSC analysis was carried out. The consequence is exhibited in

Figure 3 (a). The DSC curve showed an endothermic peak at approximately 950 K and this peak might belong to the reaction between Fe

2O

3 and C. Additionally, the weight change of REMES had no obvious difference until approximately 1100 K. According to the saturated vapor pressure of LiF at 1124 K, the evaporation of some substance might start at this temperature. [

23] Therefore, the initial distillation temperature at experiments with different temperature was selected as 1173 K.

To sum up, the REMES was mainly composed of REEs, fluorine, carbon, lithium and some oxide impurities, including silicon, iron and aluminum. Rare earth elements mainly existed as fluorides, with some forms of oxyfluorides and oxides. Lithium mainly existed as lithium fluoride. Combined with TG-DSC results, the vacuum distillation method could be used to recycle this slag.

3.2. The Distillation Experiments of REMES and Its Phase Changes of REEs

In this part, the REMES was directly distilled in the abovementioned self-made vertical furnace in vacuum. The distillation results on the different distillation time and temperature were mainly investigated. And the condensates were characterized for analyzing the phase changes process of REEs.

3.2.1. The Distillation Experiments on the Distillation Time for the Phase Changes of REMES

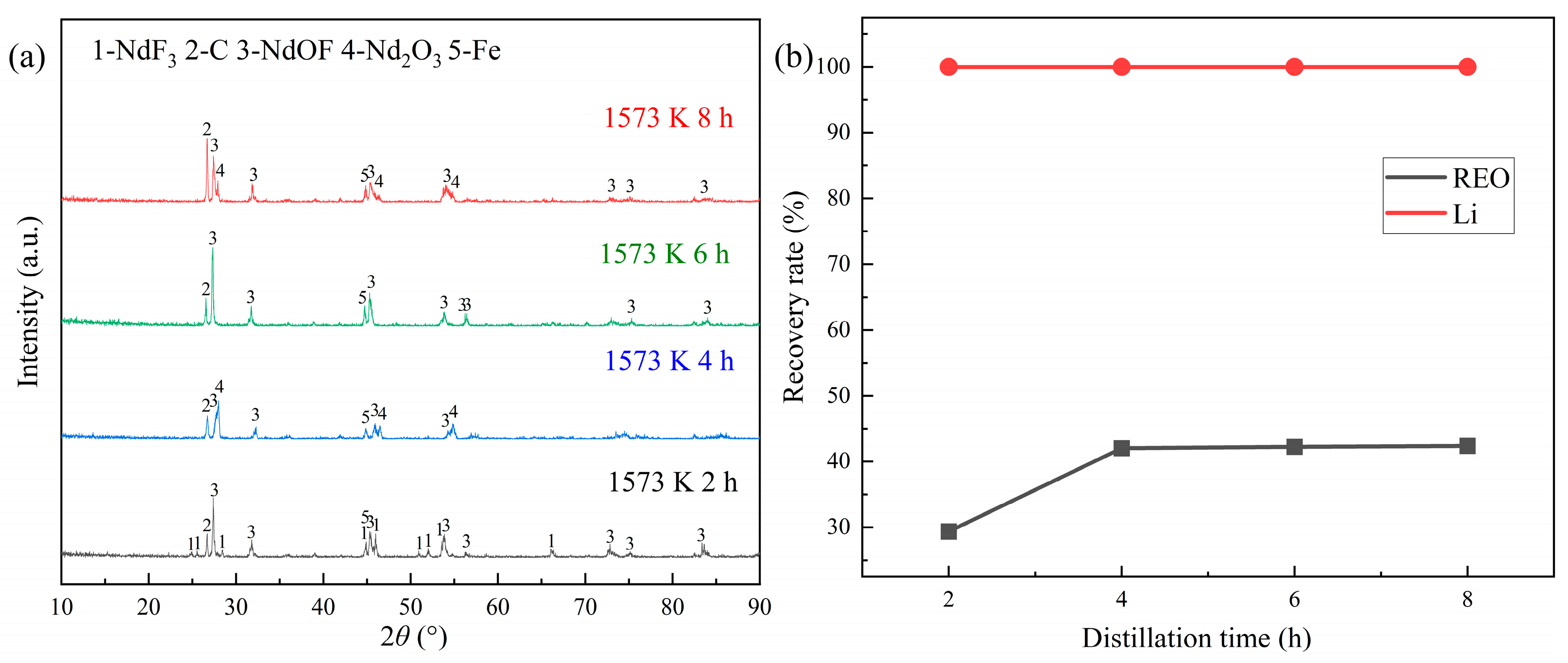

The 10 g of REMES sample was heated at 1573 K and 0.1 Pa with the distillation time changing from 2 h to 8 h. The results are showcased in

Figure 4. It suggested that when distillation time was 2 h, the diffraction peaks of NdF

3 obviously decreased and those of NdOF significantly enhanced, compared to the pattern of raw material. After the distillation time reached 4 h, NdF

3 disappeared and only NdOF could be observed. Additionally, the recovery of LiF could be completed at 2 h, and the rare earth recovery efficiency reached the maximum at 4 h, which was 42.04%. (See

Figure 4 (b)) This phenomenon indicated that there were at least two kinds of phase transitions about rare earth compounds at the distillation process, including the evaporation of rare earth fluorides and LiF as well as the generation of NdOF.

For completely investigating the transition of rare earth compounds, it was necessary to carry out the experiments at different distillation temperature. The distillation time was chosen as 6 h to insure the complete transition.

3.2.2. The Distillation Experiments on the Temperature for the Phase Changes of REMES

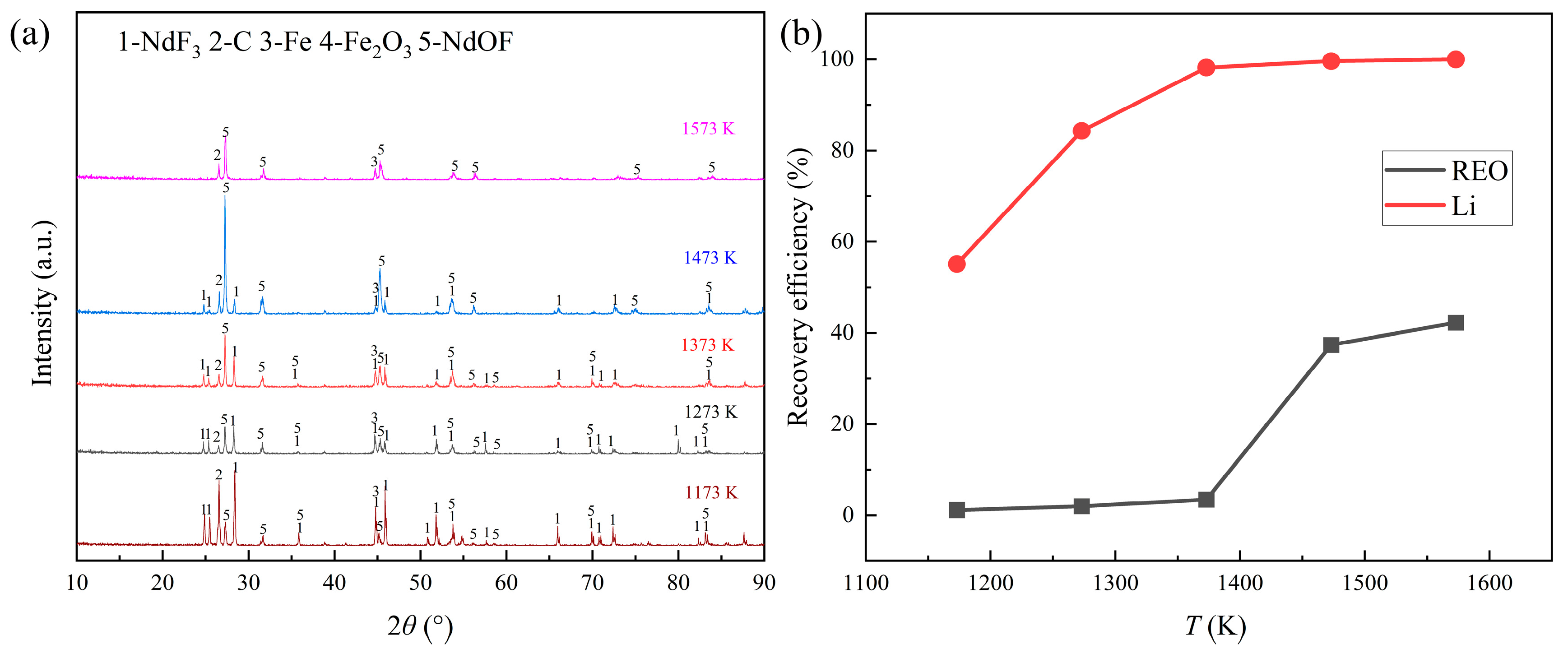

The possible phase changes of rare earth fluorides were investigated by the distillation experiments of REMES at different temperature. According to the TG-DSC results, the distillation temperature varied from 1173 K to 1573 K. The other conditions were set as the distillation time of 6 h and the absolute pressure of 0.1 Pa. The consequences are shown in

Figure 5.

Figure 5 (a) illustrated that the diffraction peaks of NdF

3 gradually decreased and the disappearance of NdF

3 could be observed at 1573 K, while the rise of the diffraction peaks of NdOF could be observed at 1173 K. According to

Figure 5 (b), at 1173 K, only LiF could evaporate. When the temperature reached 1373 K, the recovery efficiency of Li reached the maximum. As for the distillation of REEs, the evaporation of rare earth fluorides could not happen until 1473 K, and 37.36% of the total REEs could be recovered, while the rare earth recovery efficiency improved slightly at 1573 K.

The results were consistent with the results of the distillation time experiments. Besides, the generation of NdOF might start at 1173 K and this reaction terribly affected the recovery of rare earth fluorides.

3.2.3. The Investigation on the Evaporation and the Generation of NdOF in the Distillation Process

For further investigating the evaporation of fluorides and the generation of NdOF, the distillation condensates at 1573 K for 6 h were analyzed. The results are shown in

Figure 6.

In

Figure 6 (a), NdF

3 could be collected at a condenser with a small amount of PrOF, elucidating that the evaporation of rare earth fluorides occurred at 1573 K, and PrOF also possessed the ability of evaporation at high vacuum environment. Interestingly, AlF

3 and cryolithionite could be observed in the condensate containing LiF, which illustrated that it was difficult to obtain high-purity LiF product. Notably, only Al

2O

3 was discovered in the raw material, suggesting that AlF

3 and cryolithionite were generated in the distillation process. These phenomena indicated that some oxide impurities might capture the fluorine of rare earth fluorides in the high-temperature and vacuum environment, creating NdOF and Nd

2O

3.

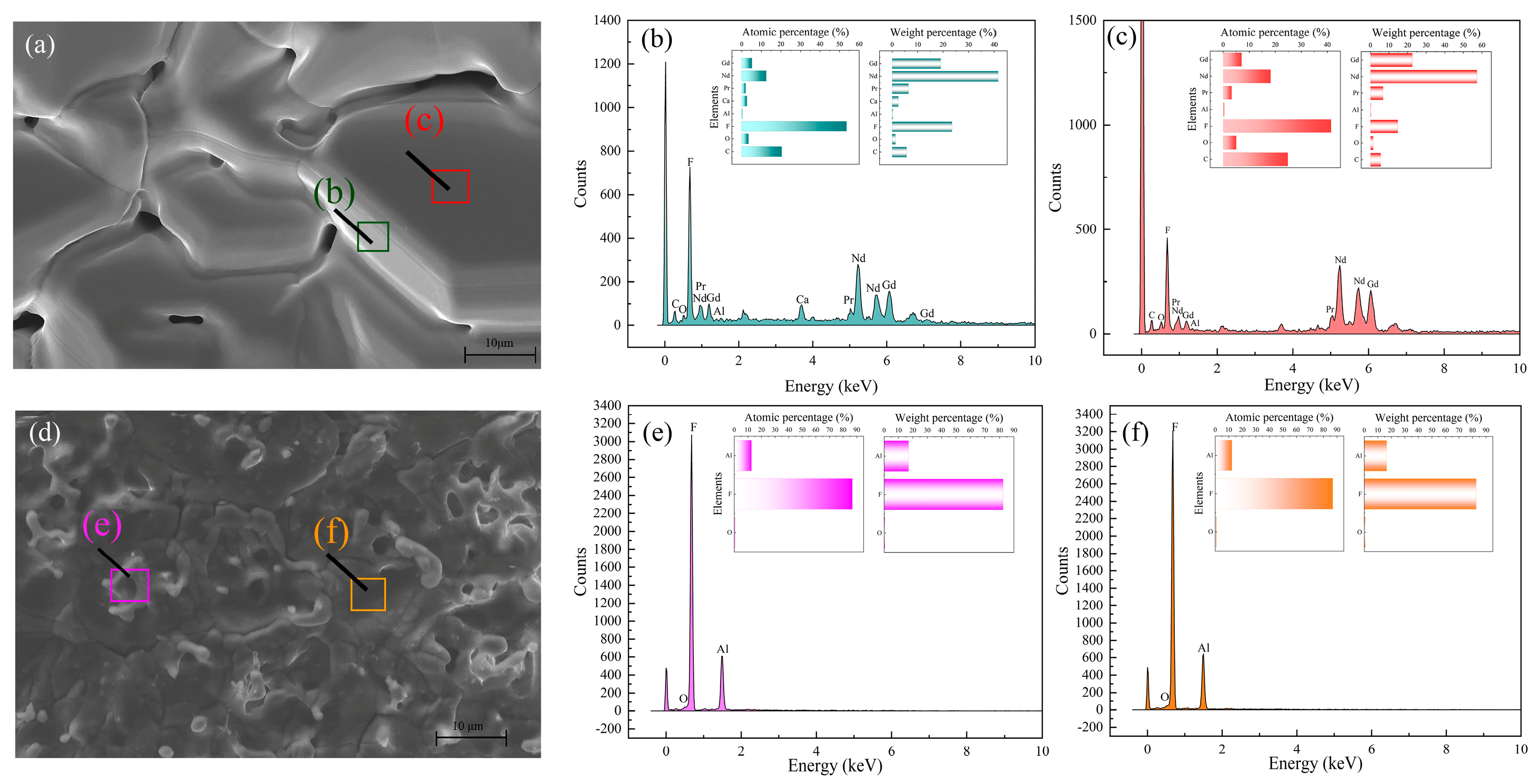

Figure 7 showed the morphology and micro distribution of the two condensates.

Figure 7 (a) showed the morphology of condensate, and the micro distributions of area (b) and (c) exhibited that the condensate was mainly composed of rare earth fluorides with a small amount of Al and Ca, which coincided with the phenomenon of

Figure 6 (a). Besides, although Li could not be discovered by EDS, the content of

Figure 7 (d - f) also agreed with the corresponding XRD result. Therefore, it was essential to investigate the exact phase change of the slag. The potential reactions were listed at

Table 3.

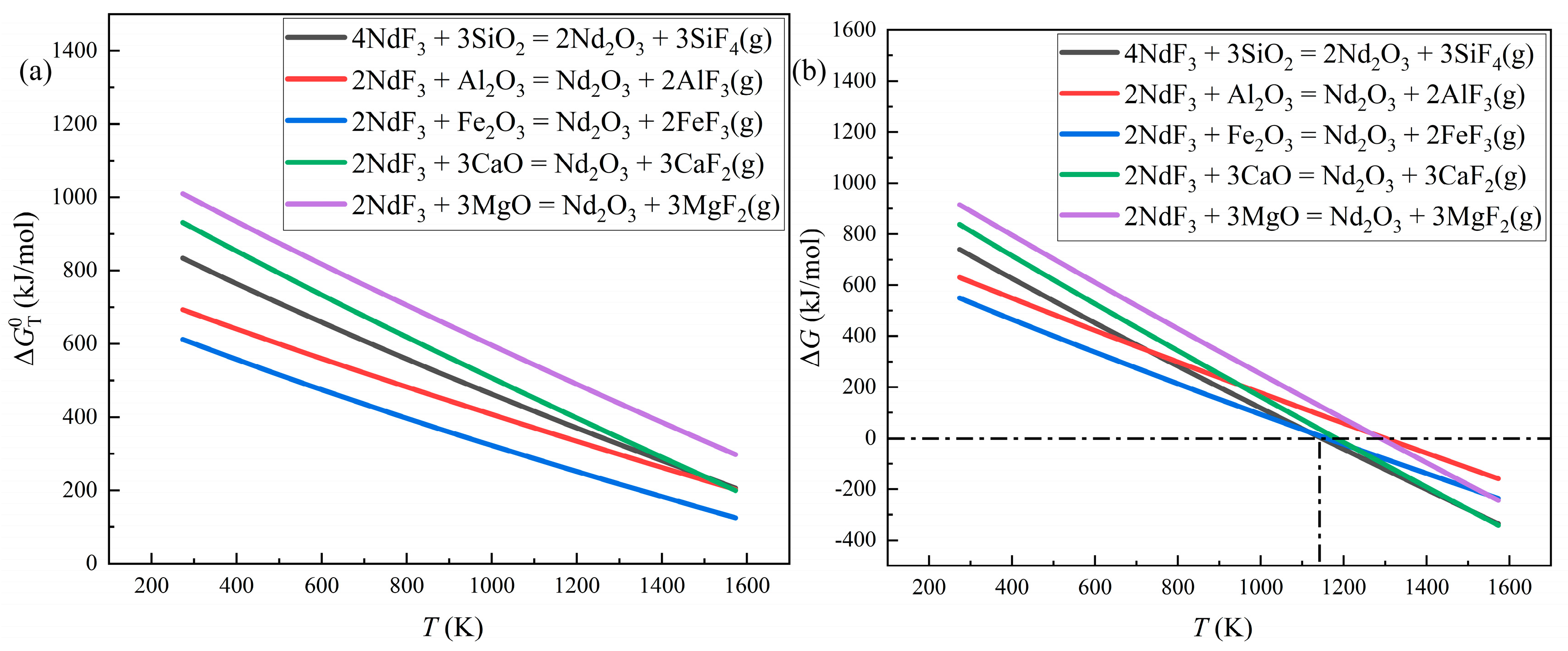

The Equations. (2) - (11) are the possible reactions in the distillation period. Owing to the lack on the thermodynamic data of NdOF, only Equations. (2) - (6) could be calculated. Because NdOF is the intermediate product of many defluorination process [

24,

25], the availability of Equations. (2) - (6) might lead to that of Equations. (7) - (11). The Gibbs free energy changes of Equations. (2) - (6) are displayed in

Figure 8.

Figure 8 (a) exhibits that the standard Gibbs free energy changes will decrease with the temperature increasing, and the changes are still higher than 0

at 1573 K, which indicates that it is difficult to react at standard condition. This result is consistent with the DSC consequence. Considering the experiments were implemented in the nonstandard state, the Gibbs free energy changes are supposed to be computed by thermodynamic isothermal equation, which are showcased as Equation. (12) and Equation. (13).

where

, is the standard Gibbs free energy change of the reaction,

;

T is the reaction temperature, K;

P is the partial pressure of the gaseous product in the reaction, Pa;

n is the stoichiometric number of the gas resultant; R is the gas constant,

; P

0 is the standard pressure, Pa.

Because the pressure of the experiments was 0.1 Pa, the partial pressure was set as 0.1 Pa. The calculation result is displayed in

Figure 8 (b). In nonstandard state, the reactions of Al

2O

3 and SiO

2 could happen around 1123 K, which agrees with the enhance of the NdOF diffraction peaks at 1173 K.

This calculation results and the experimental consequences elucidated that oxide impurities could capture the fluorine from rare earth fluorides, and the rare earth fluorides was transferred into rare earth oxides and rare earth oxyfluoride, disturbing the evaporation of rare earth fluorides and leading to the low recovery efficiency of REEs. Therefore, eliminating oxide impurities was a significant mission of the distillation recovery method.

3.3. The Effect of Fluorination Process on the Recovery of REMES by Vacuum Distillation

In previous study, NH

4HF

2 was expected as a potential fluorination reagent for rare earth oxides and oxyfluorides. [

26] The additional fluorine sources of NH

4HF

2 might have the ability to transfer the oxide impurities to fluorides. Therefore, the fluorination process of oxide impurities as well as the slag and the vacuum distillation were investigated.

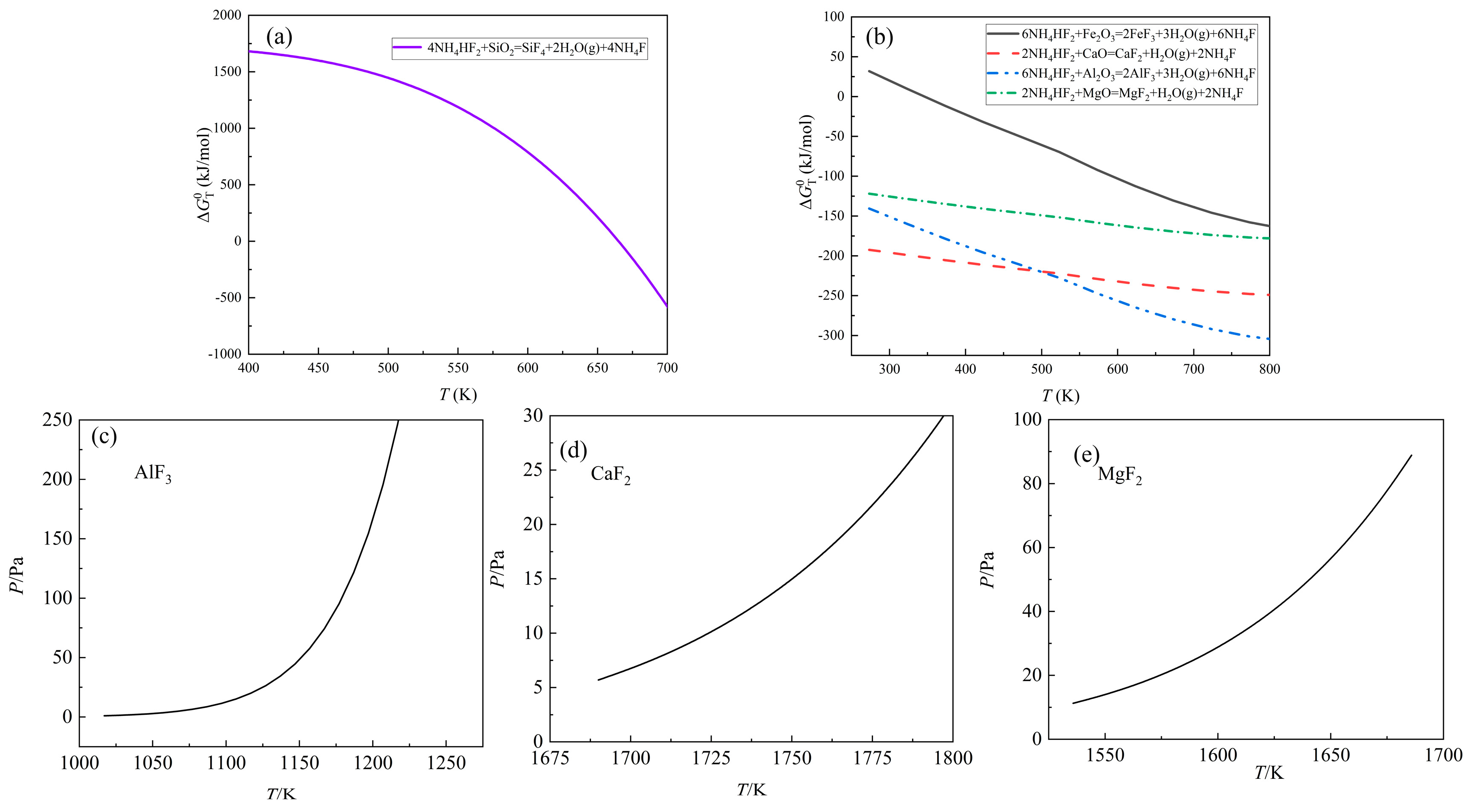

3.3.1. The Volatility of Fluoride Impurities

According to

Figure 9 (a) and (b), NH

4HF

2 also possesses the ability of fluorinating oxide impurities. Therefore, the volatility of the fluoride impurities is supposed to be studied.

The saturated vapor pressures of AlF3, CaF2 and MgF2 were calculated by Antoine equation. Due to the lack of parameters, the interference of FeF3 for the distillation of rare earth fluoride would be examined at the distillation experiment.

SiF

4 is a gaseous substance, so it would be separated in the fluorination process. As shown in

Figure 9 (c) and

Figure 6, AlF

3 is easy to evaporate and would be combined with LiF. The saturated vapor pressures of CaF

2 and MgF

2 indicated that the distillation temperature of CaF

2 and MgF

2 might be higher than 1573 K or around 1573 K, which might disturb the purity of rare earth fluorides. (See

Figure 9 (d) and (e)) Due to the low content of CaO and MgO and the evaporation of rare earth fluorides at 1473 K, the separation of CaF

2 and MgF

2 could be ignored. Therefore, it was feasible to fluorinate REMES.

3.3.2. The Treatment for REMES by Fluorination and Vacuum Distillation

For fluorinating the oxide impurities and rare earth compounds, 20 g of NH4HF2 was utilized to react with 10 g of REMES. The materials were mixed in a graphite crucible and placed in an airtight furnace with a cover. To fulfill the fluorination reaction, the fluorination experiment would process at 773 K for 6 h.

As shown in

Figure 10, the diffraction peaks of NdOF and Nd

2O

3 disappeared in the XRD pattern of the fluorinated REMES. Besides, the fluorine content increased to 30.64 wt%. Then, the fluorinated slag was compacted and then distilled at 1573 K and 0.1 Pa for 6 h. The recovery efficiency was displayed in

Table 4.

According to the experimental results, the recovery efficiency of REEs increased to 86.23%. Besides, the XRD pattern also proved the high purity of rare earth product. Although CaF

2 still could be discovered in the product by SEM-EDS, the purity of rare earth product was adequate. Notably, Fe

2O

3 could be still observed in the fluorinated slag, indicating that it was difficult to fluorinate Fe

2O

3 in the slag and the existed Fe

2O

3 might be the main obstacle for the distillation of rare earth fluoride. Besides, according to

Figure 3 the graphite in the slag could reduce Fe

2O

3 at approximately 1000 K, and the generated Fe also could be observed in

Figure 5 (a), which might decrease the effect of Fe

2O

3 to the distillation of rare earth fluoride. Therefore, NH

4HF

2 could indeed increase the recovery efficiency of REEs and reduce the influence of impurities for the product purity.

Above all, NH4HF2 could transfer the oxide impurities as well as rare earth oxides and oxyfluorides, and only a small amount of CaF2 could affect the purity of rare earth condensate.

4. Conclusion

This study introduced the phase transition of REMES at the high temperature and vacuum condition, elucidating the obstacle on recovering REEs by vacuum distillation. And then, the investigation for the fluorination process was implemented. The main conclusions were exhibited as follows:

(1) The distillation experiments results showed that 42.04% of rare earth fluorides and 99.99% of lithium fluoride in the rare earth molten salt electrolytic slag could be evaporated at 1573 K and 0.1 Pa for 4 h, and rare earth oxides as well as rare earth oxyfluorides would be generated simultaneously.

(2) The phase transition analysis elucidated that the oxide impurities could react with rare earth fluorides under high temperature and vacuum condition, capturing the fluorine element and generating rare earth oxides as well as oxyfluorides. This phenomenon terribly affected the recovery efficiency of REEs.

(3) The fluorination experiments indicated that the fluorination process could fluorinate both rare earth compounds and oxide impurities, and after fluorinating the slag by 20 g NH4HF2 at 773 K for 6 h, recovery efficiency of rare earth elements could increase to 86.23% at 1573 K and 0.1 Pa for 6 h, while some problems, such as the fluorination of Fe2O3, still existed.

In this paper, the phase changes and the fluorination of REMES were elucidated, proving the feasibility of recovery REEs by vacuum distillation. Vacuum distillation method is an environmentally friendly method, possessing the potential of recovering resources with no waste water or gas production. Although further investigation still is necessary to implement, this study also hopes that this attempt on the vacuum distillation could inspire readers, making it possible to put an environmentally friendly treatment into practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.X, G.T.; methodology, F.X, S.S.; formal analysis, X.L, Z.Y..; investigation, Z.Y., S.S.; data curation, Z.Y, Z.Z.,X.H.; writing—Z.Y., J.C., W.H.; supervision, G.T., F.X.; resources: F.X, S.S.; project administration, F.X.,G.T.; funding acquisition, F.X., G.T.; visualization: J.C., Z.Z,W.H.,C.S.K.Y.; validation: X.H.,C.S., K.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Number 2020YFC1909003) and (Grant Number 2022YFB3504401).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Patil, A.; Thalmann, N.; Torrent, L.; Tarik, M.; Struis, R.; Ludwig, C. Surfactant-based enrichment of rare earth elements from NdFeB magnet e-waste: Optimisation of cloud formation and rare earths extraction. J. Mol. Liq 2023, 382, 121905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, Y.; Ilankoon, I.; Dushyantha, N.; Nwaila, G. Rare earth permanent magnets for the green energy transition: Bottlenecks, current developments and cleaner production solutions. Resour Conserv Recycl 2025, 212, 107966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, S.; Jin, Z.; Emad, S.; Vergara, J.; Yawas, D.; Dagwa, I.; Omiogbemi, I. Potential of rare-earth compounds as anticorrosion pigment for protection of aerospace AA2198-T851 alloy. Heliyon 2023, 9(3), e14693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USGS P. Mineral commodity summaries 2024. US Geological Survey 2024:144-145.

- USGS P. Mineral commodity summaries 2020. US Geological Survey 2020:132-133.

- Omodara, L.; Pitkaaho, S.; Turpeinen, E.; Saavalainen, P.; Oravisjarvi, K.; Keiski, R. Recycling and substitution of light rare earth elements, cerium, lanthanum, neodymium, and praseodymium from end-of-life applications – A review. J CLEAN PROD 2019, 236, 117573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Gu, J.; Zeng, X.; Yuan, W.; Rao, M.; Xiao, B.; Hu, H. A Review of the Occurrence and Recovery of Rare Earth Elements from Electronic Waste. Molecules 2024, 29, 4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, F.; Hu, W.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, H. Technologies of Recycling REEs and Iron from NdFeB Scrap. Metals 2023, 13, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-P.; Chen, Y.-J.; Tso, Y.-C.; Sheng, C.-F.; Ponou, J.; Kou, M.; Zhou, H.; Chen, W.-S. Separation of Cerium Oxide Abrasive and Glass Powder in an Abrasive-Glass Polishing Waste by Means of Liquid–Liquid–Powder Extraction Method for Recovery: A Comparison of Using a Cationic and an Anionic Surfactant Collector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borra, C.R.; Vlugt, T.J.H.; Yang, Y.; Offerman, S.E. Recovery of Cerium from Glass Polishing Waste: A Critical Review. Metals 2018, 8, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daminescu, D.; Duteanu, N.; Ciopec, M.; Negrea, A.; Negrea, P.; Nemeş, N.S.; Pascu, B.; Lazău, R.; Berbecea, A. Kinetic Modelling the Solid–Liquid Extraction Process of Scandium from Red Mud: Influence of Acid Composition, Contact Time and Temperature. Materials 2023, 16, 6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S.; Costa, R.; Shah, S.; Mishra, S. Bevilaqua, Denise.; Akcil, A. Biotechnological trends and market impact on the recovery of rare earth elements from bauxite residue (red mud) – A review. Resour Conserv Recycl 2021, 171, 105645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cardona, J.; Huang, T.; Zhao, F.; Sutherland, J.; Atifi, A.; Fox, R.; Baek, D. Molten salt electrolysis and room temperature ionic liquid electrochemical processes for refining rare earth metals: Environmental and economic performance comparison. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2022, 54, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Gong, A.; Tian, L.; Xu, Z. Research Progress of Rare Earth Recovery from Rare Earth Waste. J. Chin. Rare Earth Soc 2019, 37(3), 259–272. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Z.; Hu, X.; Wen, H. Effect of roasting activation of rare earth molten salt slag on extraction of rare earth, lithium and fluorine. J RARE EARTH 2023, 41, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubula, Y.; Yu, M.; Yang, D.; Niu, H.; Qiu, T.; Mei, G. Recovery of Rare Earths from Rare-Earth Melt Electrolysis Slag by Mineral Phase Reconstruction. JOM 2024, 76, 4732–4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yu, M.; Mubula, Y.; Yuan, W.; Huang, Z.; Lin, B.; Mei, G.; Qiu, T. Recovering rare earths, lithium and fluorine from rare earth molten salt electrolytic slag using sub-molten salt method. J RARE EARTH 2024, 42(9), 1774–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wei, T.; Xiao, M.; Niu, F.; Shen, L. Rare Earth Recovery from Fluoride Molten-Salt Electrolytic Slag by Borax Roasting-Hydrochloric Acid Leaching. JOM 72, 939-945.

- Tian, L.; Chen, L.; Gong, A.; Wu, X.; Cao, C.; Xu, Z. Recovery of rare earths, lithium and fluorine from rare earth molten salt electrolytic slag via fluoride sulfate conversion and mineral phase reconstruction. MINER ENG 2021, 170, 106956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubula, Y.; Yu, M.; Gu, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, M.; Qiu, T.; Mei, G. Recovery of rare earths from rare earth molten salt electrolytic slag using alkali phase reconstruction method with the aid of external electric field. J RARE EARTH 2024, In press.

- Zhang, M.; He, B.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Liang, Y. Recovery of rare earth elements from rare earth molten salt electrolytic slag via fluorine fixation by MgCl2 roasting. J RARE EARTH 2024, 42, 1979–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, S.; Liu, K.; Xia, Q.; Huang, M.; Hu, G.; Zhang, H.; Qi, T. Recovery of rare earths, lithium, and fluorine from rare earth molten salt electrolytic slag by mineral phase reconstruction combined with vacuum distillation. Sep. Purif 2023, 310, 123105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaws, C. The Yaws Handbook of Yapor Pressure Antoine Coefficients Second Ed. Gulf Professional Publishing, Oxford, Volume 2, 2015, pp. 318.

- Xu, G. Rare earths (up). Metallurgical Industry Press, Beijing, 1995, pp 59-60.

- Chong, S.; Riley, B. Thermal conversion in air of rare-earth fluorides to rare-earth oxyfluorides and rare-earth oxides. J. Nucl. Mater 2022, 561, 153538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xiao, F.; Sun, C.; Zhong, H.; Tu, Gan. REEs recovery from molten salt electrolytic slag: Challenges and opportunities for environmentally friendly techniques. J RARE EARTH 2024, 42(6), 1009-1019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).