Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Selection

2.2. Measurement of Cadmium Exposure and Its Effects on the Function of Kidneys

2.3. Normalization of Cadmium Excretion Rate and β2-Microglobulin Excretion Rate

2.4. Mediation Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Participants According to eGFR and β2-Microglobulin Excretion

3.2. Effects of Cadmium Exposure on Risks of Hypertension and β2-Microglobulinuria

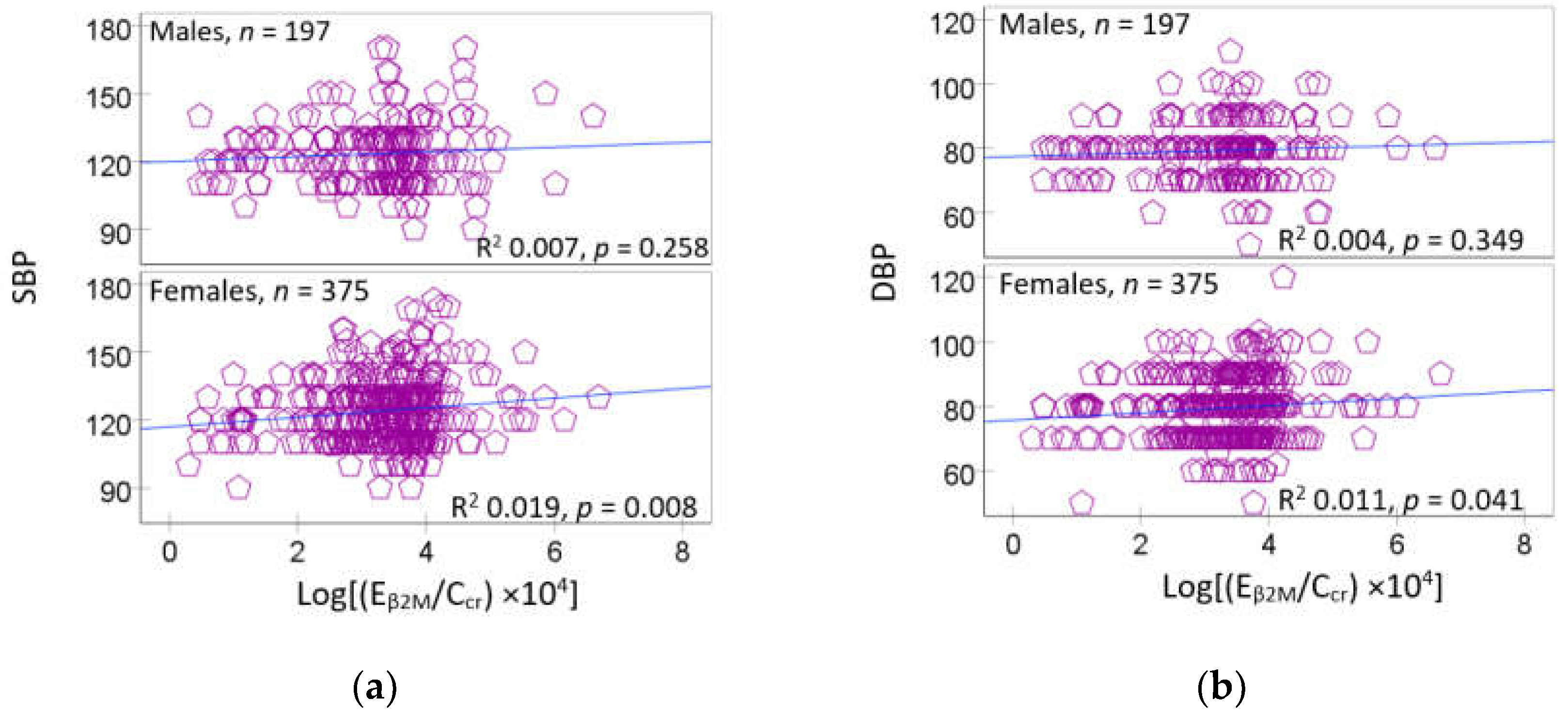

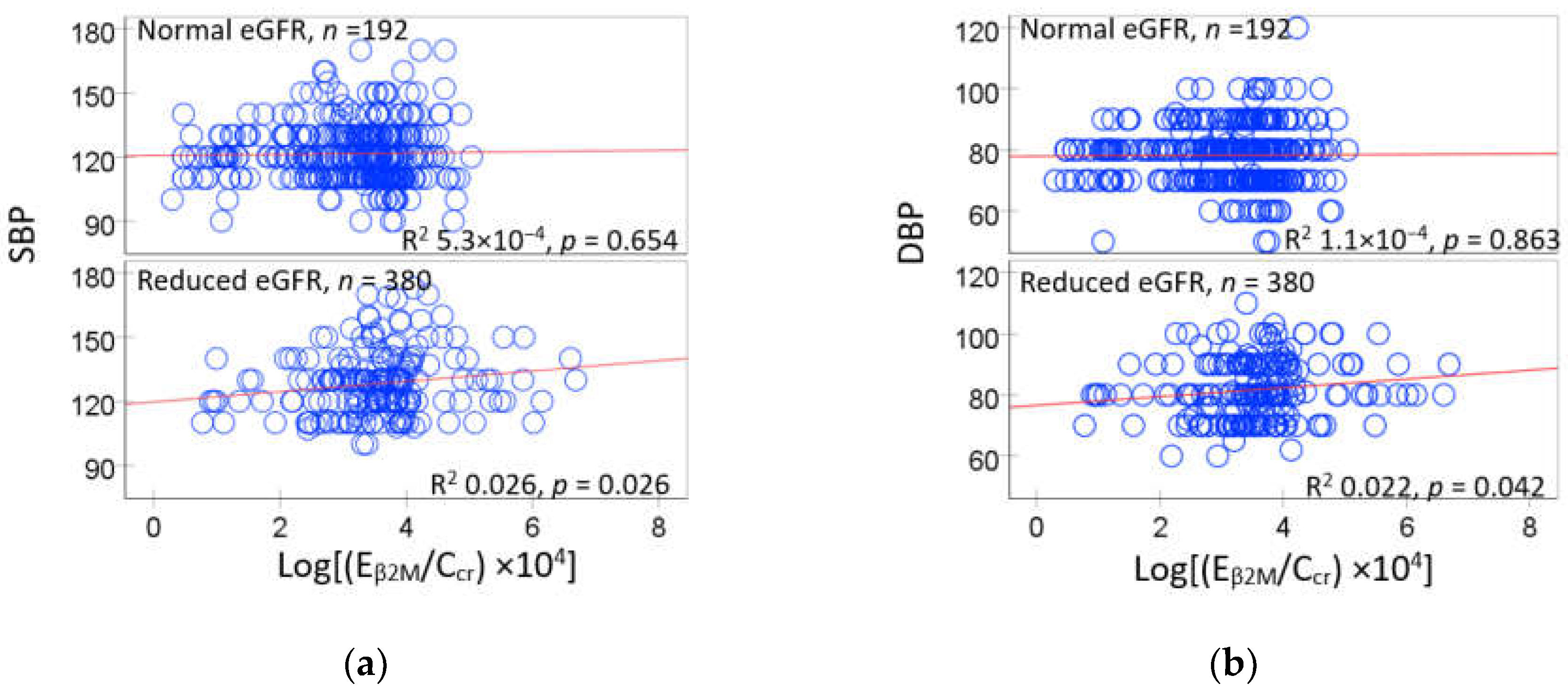

3.3. Urinary β2-Microglobulin as a Predictor of Rising Blood Pressure

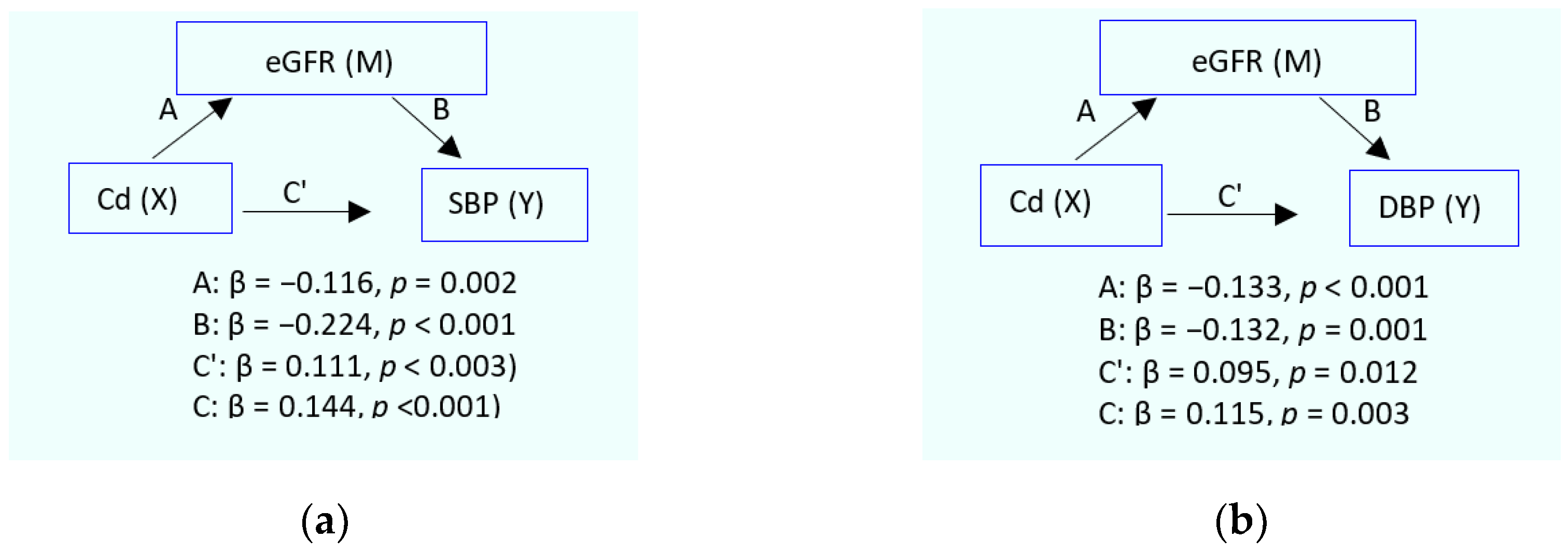

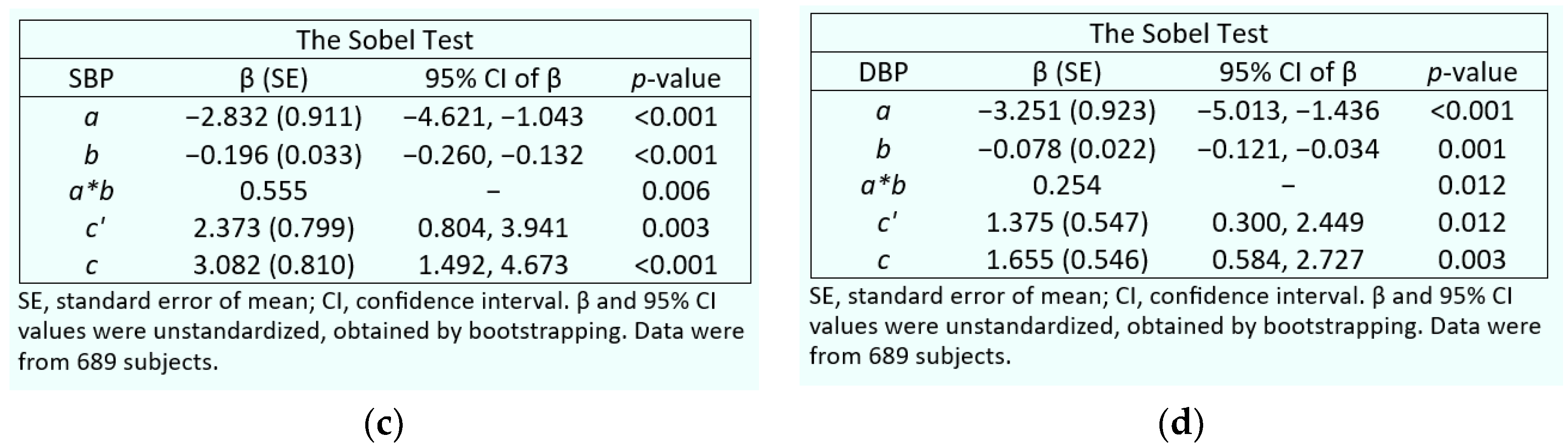

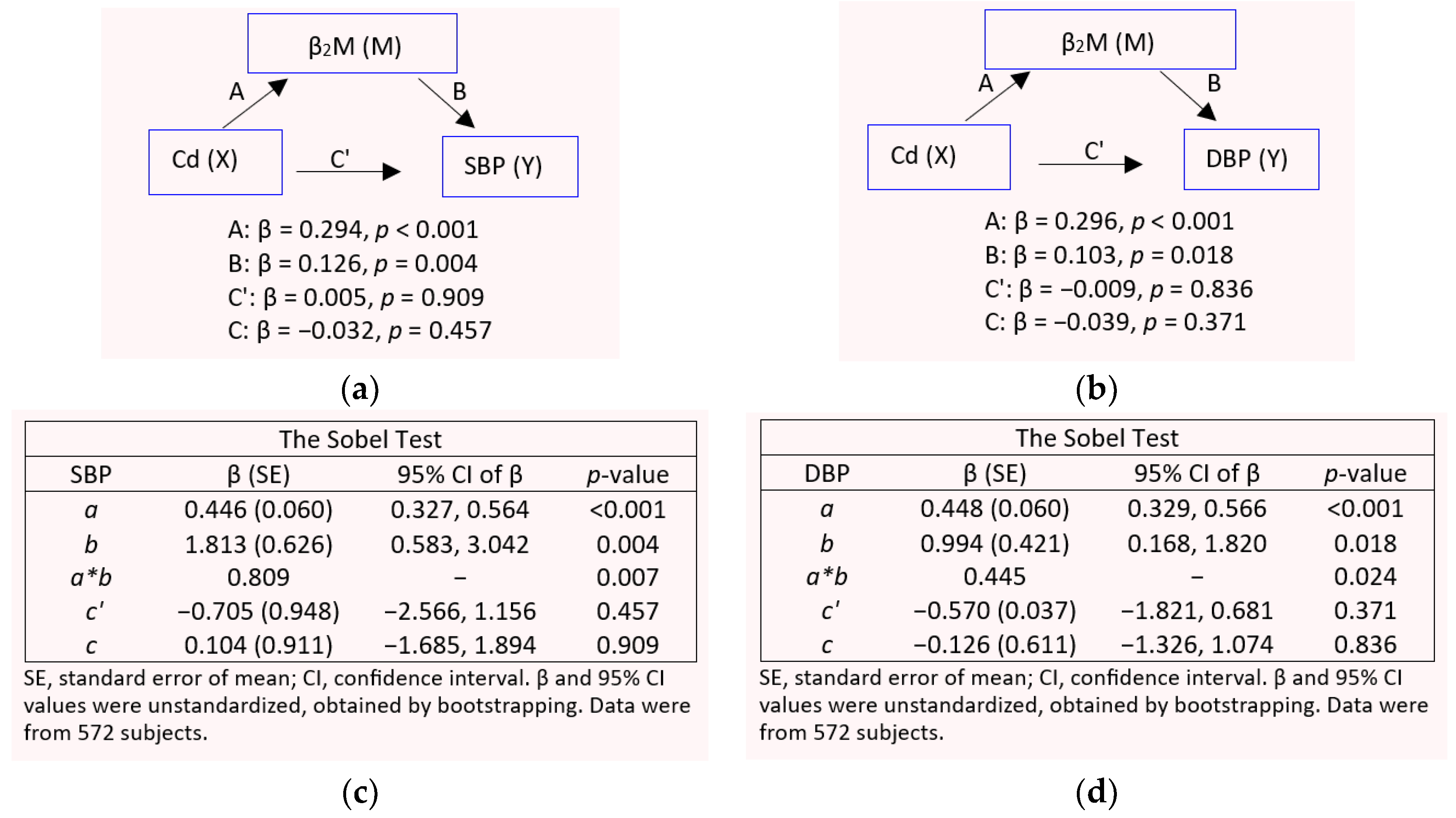

3.4. GFR and β2-Microglobulin as Mediators of Cadmium-Induced Blood Pressure Elevation

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Cadmium Exposure on Blood Pressure and Tubular Reabsorptive Function

4.2. Gender Differences in Blood Pressure Variability and Cadmium Effects

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. Estimation of health risks associated with dietary cadmium exposure. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fechner, C.; Hackethal, C.; Höpfner, T.; Dietrich, J.; Bloch, D.; Lindtner, O.; Sarvan, I. Results of the BfR MEAL Study: In Germany, mercury is mostly contained in fish and seafood while cadmium, lead, and nickel are present in a broad spectrum of foods. Food Chem. X 2022, 14, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Kataoka, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Matsuda, R.; Uneyama, C. Dietary exposure of the Japanese general population to elements: Total diet study 2013–2018. Food Saf. 2022, 10, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, D.T.; Jandev, V.; Petroni, M.; Atallah-Yunes, N.; Bendinskas, K.; Brann, L.S.; Heffernan, K.; Larsen, D.A.; MacKenzie, J.A.; Palmer, C.D.; et al. Airborne levels of cadmium are correlated with urinary cadmium concentrations among young children living in the New York state city of Syracuse, USA. Environ. Res. 2023, 223, 115450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almerud, P.; Zamaratskaia, G.; Lindroos, A.K.; Bjermo, H.; Andersson, E.M.; Lundh, T.; Ankarberg, E.H.; Lignell, S. Cadmium, total mercury, and lead in blood and associations with diet, sociodemographic factors, and smoking in Swedish adolescents. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 110991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, R.S.; Fresquez, M.R.; Watson, C.H. Cigarette smoke cadmium breakthrough from traditional filters: Implications for exposure. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2015, 39, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thévenod, F.; Herbrechter, R.; Schlabs, C.; Pethe, A.; Lee, W.K.; Wolff, N.A.; Roussa, E. Role of the SLC22A17/lipocalin-2 receptor in renal endocytosis of proteins/metalloproteins: a focus on iron- and cadmium-binding proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2023, 325, F564–F577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thévenod, F.; Lee, W.K.; Garrick, MD. Iron and Cadmium Entry Into Renal Mitochondria: Physiological and Toxicological Implications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, Q.; Shi, W.; Zhang, W.; Gao, X.; Li, Y.; Hao, R.; Dong, X.; Chen, C.; et al. Associations of environmental cadmium exposure with kidney damage: Exploring mediating DNA methylation sites in Chinese adults. Environ. Res. 2024, 251 (Pt 1), 118667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, S.; Nogawa, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Sakurai, M.; Nishijo, M.; Ishizaki, M.; Morikawa, Y.; Kido, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Suwazono, Y. Effect of renal tubular damage on non-cancer mortality in the general Japanese population living in cadmium non-polluted areas. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2023, 43, 1849–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smereczański, N.M.; Brzóska, M.M. Current levels of environmental exposure to cadmium in industrialized countries as a risk factor for kidney damage in the general population: A comprehensive review of available data. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aramjoo, H.; Arab-Zozani, M.; Feyzi, A.; Naghizadeh, A.; Aschner, M.; Naimabadi, A.; Farkhondeh, T.; Samarghandian, S. The association between environmental cadmium exposure, blood pressure, and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 35682–35706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.C.; Almeida Lopes, A.C.B.; Urbano, M.R.; Carvalho, M.F.H.; Silva, A.M.R.; Tinkov, A.A.; Aschner, M.; Mesas, A.E.; Silbergeld, E.K.; Paoliello, M.M.B. An updated systematic review on the association between Cd exposure, blood pressure and hypertension. Ecotoxicol. Environ, Saf. 2021, 208, 111636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verzelloni, P.; Giuliano, V.; Wise, L.A.; Urbano, T.; Baraldi, C.; Vinceti, M.; Filippini, T. Cadmium exposure and risk of hypertension: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2024, 120014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doccioli, C.; Sera, F.; Francavilla, A.; Cupisti, A.; Biggeri, A. Association of cadmium environmental exposure with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinleye, A.; Oremade, O.; Xu, X. Exposure to low levels of heavy metals and chronic kidney disease in the US population: A cross sectional study. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0288190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, K.J.; Marquez, N.; Dolgert, A.; Fukutaki, K.; Fullman, N.; McGaughey, M.; Pletcher, M.A.; Smith, A.E.; Tang, K.; Yuan, C.W.; et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: Reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 2018, 392, 2052–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Forecasting Collaborators. Burden of disease scenarios for 204 countries and territories, 2022–2050: A forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2204–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murton, M.; Goff-Leggett, D.; Bobrowska, A.; Garcia Sanchez, J.J.; James, G.; Wittbrodt, E.; Nolan, S.; Sörstadius, E.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Tuttle, K. Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease by KDIGO Categories of Glomerular Filtration Rate and Albuminuria: A Systematic Review. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Jafar, T.H.; Nitsch, D.; Neuen, B.L.; Perkovic, V. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2021, 398, 786–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, D.R.; Vassalotti, J.A. Screening, identifying, and treating chronic kidney disease: Why, who, when, how, and what? BMC Nephrol. 2024, 25, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirovic, A.; Satarug, S.; Jevtic, J.; Ivanovski, A.; Orisakwe, O.E.; Jankovic, S.; Cirovic, A.J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 86, 127542.

- Oliver-Williams, C.; Howard, A.G.; Navas-Acien, A.; Howard, B.V.; Tellez-Plaza, M.; Franceschini, N. Cadmium body burden, hypertension, and changes in blood pressure over time: Results from a prospective cohort study in American Indians. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2018, 12, 426–437.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tellez-Plaza, M.; Navas-Acien, A.; Crainiceanu, C.M.; Guallar, E. Cadmium exposure and hypertension in the 1999-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scinicariello, F.; Abadin, H.G.; Murray, H.E. Association of low-level blood lead and blood pressure in NHANES 1999–2006. Environ. Res. 2011, 111, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, R.E.; Levallois, P. Associations between cadmium levels in blood and urine, blood pressure and hypertension among Canadian adults. Environ. Res. 2017, 155, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Q.; Wu, H.B.; Niu, Q.S.; Jia, P.P.; Qin, Q.R.; Wang, X.D.; He, J.L.; Yang, W.J.; Huang, F. Exposure to multiple metals and the risk of hypertension in adults: A prospective cohort study in a local area on the Yangtze River, China. Environ. Int. 2021, 153, 106538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liu, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, H.; Lu, Q. Polymorphisms in gene MMP-2 modify the association of cadmium exposure with hypertension risk. Environ. Int. 2019, 124, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.K.; Kim, Y. Association of blood cadmium with hypertension in the Korean general population: Analysis of the 2008–2010 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2012, 55, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Kim, B. Influence of serum ferritin combined with blood cadmium concentrations on blood pressure and hypertension: From the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda, M.; Wai, K.M.; Kanda, A.; Ando, M.; Murashita, K.; Nakaji, S.; Ihara, K. Low Level of Serum Cadmium in Relation to Blood Pressures Among Japanese General Population. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S.; Nishijo, M.; Ujjin, P.; Vanavanitkun, Y.; Moore, M.R. Cadmium-induced nephropathy in the development of high blood pressure. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 157, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonprasert, K.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Ruenweerayut, R.; Johnson, D.W.; Na-Bangchang, K.; Satarug, S. Is renal tubular cadmium toxicity clinically relevant? Clin. Kidney J. 2018, 11, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S.; Boonprasert, K.; Gobe, G.C.; Ruenweerayut, R.; Johnson, D.W.; Na-Bangchang, K.; Vesey, D.A. Chronic exposure to cadmium is associated with a marked reduction in glomerular filtration rate. Clin. Kidney J. 2018, 12, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Yimthiang, S.; Khamphaya, T.; Pouyfung, P.; Đorđević, A.B. Environmental Cadmium Exposure Induces an Increase in Systolic Blood Pressure by Its Effect on GFR. Stresses 2024, 4, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Nogawa, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Kido, T.; Sakurai, M.; Nakagawa, H.; Suwazono, Y. Benchmark Dose of Urinary Cadmium for Assessing Renal Tubular and Glomerular Function in a Cadmium-Polluted Area of Japan. Toxics 2024, 12, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanathan, P.C.; Ooi, K.S.; Mohammad Haniff, M.A.S.; Ahmadipour, M.; Dee, C.F.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Hamzah, A.A.; Chang, E.Y. Lifting the Veil: Characteristics, Clinical Significance, and Application of β-2-Microglobulin as Biomarkers and Its Detection with Biosensors. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2022, 8, 3142–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, T.; Meng, Q.; A Saleh, M.; E Norlander, A.; Joehanes, R.; Zhu, J.; Chen, B.H.; Zhang, B.; Johnson, A.D.; Ying, S.; et al. Integrative network analysis reveals molecular mechanisms of blood pressure regulation. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2015, 11, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.R.; Hank, S.; Dale, B.L.; Himmel, L.; Zhong, X.; Smart, C.D.; Fehrenbach, D.J.; Chen, Y.; Prabakaran, N.; Tirado, B.; et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in SH2B3/LNK promotes hypertension development and renal damage. Circ. Res. 2022, 131, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, J.A.; Hwang, S.J.; Huan, T.; Mendelson, M.; Yao, C.; Courchesne, P.; Saleh, M.A.; Madhur, M.S.; Levy, D. Evidence for a causal role of the SH2B3-β2M axis in blood pressure regulation. Hypertension 2019, 73, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Swaddiwudhipong, W.; Ruangyuttikarn, W.; Nishijo, M.; Ruiz, P. Modeling cadmium exposures in low- and high-exposure areas in Thailand. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teeyakasem, W.; Nishijo, M.; Honda, R.; Satarug, S.; Swaddiwudhipong, W.; Ruangyuttikarn, W. Monitoring of cadmium toxicity in a Thai population with high-level environmental exposure. Toxicol. Lett. 2007, 169, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, R.; Swaddiwudhipong, W.; Nishijo, M.; Mahasakpan, P.; Teeyakasem, W.; Ruangyuttikarn, W.; Satarug, S.; Padungtod, C.; Nakagawa, H. Cadmium induced renal dysfunction among residents of rice farming area downstream from a zinc-mineralized belt in Thailand. Toxicol. Lett. 2010, 198, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yimthiang, S.; Pouyfung, P.; Khamphaya, T.; Kuraeiad, S.; Wongrith, P.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Satarug, S. Effects of Environmental Exposure to Cadmium and Lead on the Risks of Diabetes and Kidney Dysfunction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloch, M.J.; Basile, J.N. Review of recent literature in hypertension: Updated clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease now include albuminuria in the classification system. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2013, 15, 865–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Scmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Castro, A.F., III; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T.; et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.A.; Allen, C.M.; Akbari, A.; Collier, C.P.; Holland, D.C.; Day, A.G.; Knoll, G.A. Comparison of the new and traditional CKD-EPI GFR estimation equations with urinary inulin clearance: A study of equation performance. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 488, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Becker, C.; Inker, L.A. Glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria for detection and staging of acute and chronic kidney disease in adults: a systematic review. JAMA 2015, 313, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, R.W.; Reed, L.D. Estimation of average concentration in the presence of nondetectable values. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 1990, 5, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C. Cadmium-Induced Proteinuria: Mechanistic Insights from Dose–Effect Analyses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, P.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E. Total imprecision of exposure biomarkers: implications for calculating exposure limits. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2007, 50, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Nishijo, M.; Ruangyuttikarn, W.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. The Effect of Cadmium on GFR Is Clarified by Normalization of Excretion Rates to Creatinine Clearance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, K.R.; Gosmanova, E.O. A generic method for analysis of plasma concentrations. Clin. Nephrol. 2020, 94, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J. Advances in mediation analysis: A survey and synthesis of new developments. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 825–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Warsi, G.; Dwyer, J.H. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multiv. Behav. Res. 1995, 30, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Meth. Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckelhoff, J.F. Gender differences in the regulation of blood pressure. Hypertension 2001, 37, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckelhoff, J.F. Mechanisms of sex and gender differences in hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2023, 37, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, P.J.; Currie, G.; Delles, C. Sex differences in the prevalence, outcomes and management of hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2022, 24, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashima, Y.; Konta, T.; Kudo, K.; Takasaki, S.; Ichikawa, K.; Suzuki, K.; Shibata, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Kato, T.; Kawata, S.; et al. Increases in urinary albumin and beta2-microglobulin are independently associated with blood pressure in the Japanese general population: The Takahata Study. Hypertens. Res. 2011, 34, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, K.; Konta, T.; Mashima, Y.; Ichikawa, K.; Takasaki, S.; Ikeda, A.; Hoshikawa, M.; Suzuki, K.; Shibata, Y.; Watanabe, T.; et al. The association between renal tubular damage and rapid renal deterioration in the Japanese population: The Takahata study. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2011, 15, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, K.W.; Chien, L.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Kao, H.C. Sex-specific differences in early renal impairment associated with arsenic, lead, and cadmium exposure among young adults in Taiwan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 52655–52664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, C.; Nagao, Y.; Shibuya, C.; Kashiki, Y.; Shimizu, H. Urinary cadmium and serum levels of estrogens and androgens in postmenopausal Japanese women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, C.; Konishi, K.; Goto, Y.; Tamura, T.; Wada, K.; Hayashi, M.; Takeda, N.; Yasuda, K. Associations of urinary cadmium with circulating sex hormone levels in pre- and postmenopausal Japanese women. Environ. Res. 2016, 150, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, I.; Engström, A.; Vahter, M.; Skerfving, S.; Lundh, T.; Lidfeldt, J.; Samsioe, G.; Halldin, K.; Åkesson, A. Associations between cadmium exposure and circulating levels of sex hormones in postmenopausal women. Environ. Res. 2014, 134, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochud, M.; Jenny-Burri, J.; Pruijm, M.; Ponte, B.; Guessous, I.; Ehret, G.; Petrovic, D.; Dudler, V.; Haldimann, M.; Escher, G.; et al. Urinary Cadmium Excretion Is Associated with Increased Synthesis of Cortico- and Sex Steroids in a Population Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | All, n = 689 | Normal eGFR a | Reduced eGFR b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males, n = 183 |

Females, n = 280 |

Males, n = 68 |

Females, n = 158 |

||

| % Female | 63.4 | 39.5 | 60.5 *** | 30.1 | 69.5 *** |

| % Smoking | 28.3 | 48.5 | 17.7 *** | 53.0 | 13.2 *** |

| % Hypertension | 32.4 | 22.4 | 30.7 * | 42.0 | 42.4 |

| Age, years | 42.7 (12.4) | 37.8 (11.5) | 40.8 (11.4) ** | 44.6 (12.5) | 51.0 (11.0) ** |

| Age range, years | 16−80 | 16−73 | 18−69 | 19−71 | 19−80 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.4 (3.9) | 22.6 (3.1) | 23.7 (4.3) ** | 23.6 (3.6) | 24.6 (3.7) * |

| eGFR c, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 97.4 (17.6) | 106.7 (10.7) | 107.6 (10.0) | 77.9 (9.4) | 76.7 (11,0) |

| % eGFR ≤ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 2.6 | 0 | 0 | 2.9 | 10.1 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 121 (15) | 120 (14) | 119 (14) | 125 (16) | 126 (17) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 78 (10) | 77 (10) | 77 (10) | 80 (11) | 80 (11) |

| ECd/Ecr, µg/g creatinine | 2.77 (3.9) | 1.70 (2.88) | 3.29 (3.94) *** | 1.73 (2.74) | 3.51 (4.95) ** |

| Eβ2M/Ecr, µg/g creatinine | 253 (1975) | 83 (174) | 70 (118) * | 748 (2868) | 549 (3522) |

| % Eβ2M/Ecr ≥ 300 µg/g creatinine | 7.3 | 8.6 | 2.7 * | 16.7 | 10.0 |

| (ECd/Ccr) × 100, µg/L filtrate | 2.19 (3.27) | 1.46 (2.41) | 2.13 (2.56) ** | 2.04 (3.35) | 3.22 (4.69) * |

| (Eβ2M/Ccr) × 100, µg/L filtrate | 301 (2753) | 71 (151) | 46 (77) | 1297 (5949) | 597 (4182) |

| % (Eβ2M/Ccr) × 100 ≥ 300 µg/L filtrate | 6.8 | 7.9 | 1.8 ** | 16.7 | 10.1 |

| Parameters | All, n = 572 | Quartile of β2M excretion rate a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1, n =142 |

Quartile 2, n =143 |

Quartile 3, n = 142 |

Quartile 4, n = 145 |

||

| % Female | 65.6 | 57.0 | 69.2 | 67.6 | 68.3 |

| % Smoking | 31.5 | 27.5 | 27.3 | 34.5 | 36.6 |

| % Hypertension | 37.1 | 34.5 | 31.5 | 28.7 | 43.4 |

| Age, years | 46.2 (10) | 44.2 (9.3) | 45.9 (10.2) | 45.0 (10.2) | 49.7 (9.6) *** |

| Age range, years | 16−80 | 16−68 | 18−74 | 18−70 | 21−80 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.1 (3.8) | 24.3 (3.4) | 24.4 (4.4) | 24.0 (3.5) | 23.6 (3.5) |

| % BMI > 30 kg/m2 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 4.3 |

| eGFR b, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 96.8 (17.5) | 100.4 (14.4) | 99.6 (16.6) | 99.8 (17.5) | 87.6 (18.3)*** |

| % eGFR ≤ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 10.3 *** |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 124 (14) | 122 (12) | 124 (14) | 122 (14) | 126 (17) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 79 (10) | 79 (8) | 79 (9) | 79 (10) | 81 (10) |

| ECd/Ecr, µg/g creatinine | 3.23 (4.13) | 2.05 (2.67) | 2.56 (3.34) | 3.50 (4.58) | 4.80 (4.99) *** |

| Eβ2M/Ecr, µg/g creatinine | 276 (2070) | 2.54 (2.54) | 21.4 (9.7) | 59 (21) | 1009 (4032) *** |

| % Eβ2M/Ecr ≥ 300 µg/g creatinine | 7.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28.3 |

| (ECd/Ccr) × 100, µg/L filtrate | 2.56 (3.46) | 1.55 (1.98) | 1.86 (2.43) | 2.64 (3.50) | 4.14 (4.65) *** |

| (Eβ2M/Ccr) × 100, µg/L filtrate | 314 (2757) | 1.95 (1.89) | 15.7 (6.2) | 44 (12) | 1179 (5396) *** |

| % (Eβ2M/Ccr) × 100 ≥ 300 µg/L filtrate | 6.6% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26.2 |

| Independent Variables/Factors | Hypertension | β2-microglobulinuria a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POR (95% CI) | p | POR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age, years | 1.059 (1.040, 1.078) | <0.001 | 0.998 (0.948, 1.050) | 0.926 |

| Gender | 1.477 (0.953, 2.290) | 0.081 | 2.165 (0.946, 4.955) | 0.068 |

| Smoking | 1.524 (0.974, 2.363) | 0.065 | 0.600 (0.266, 1.354) | 0.219 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| < 24 | Referent | Referent | ||

| 24−30 | 2.080 (1.442, 3.001) | <0.001 | 0.605 (0.287, 1.276) | 0.187 |

| > 30 | 3.342 (1.481, 7.543) | 0.004 | 1.121 (0.230, 5.466) | 0.887 |

| ECd/Ccr quartile: (ECd/Ccr) ×100 µg/L filtrate | ||||

| Q1: < 0.18 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Q2: 0.18−0.70 | 1.078 (0.583, 1.994) | 0.811 | 0.574 (0.034, 9.658) | 0.700 |

| Q3: 0.71−2.73 | 2.522 (1.465, 4.342) | 0.001 | 6.982 (0.887, 54.93) | 0.065 |

| Q4: ≥ 2.74 | 2.787 (1.595, 4.871) | <0.001 | 10.67 (1.364, 83.40) | 0.024 |

| Independent Variables/Factors |

SBP or DBP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All, n = 548 |

Normal eGFR a n = 362 |

Reduced eGFR b n = 186 |

||||

| β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Model 1: SBP | ||||||

| Age, years | 0.323 | <0.001 | 0.281 | <0.001 | 0.250 | 0.002 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.188 | <0.001 | 0.201 | <0.001 | 0.158 | 0.029 |

| Log[(ECd/Ccr) ×105, µg/L filtrate | −0.037 | 0.400 | −0.038 | 0.510 | −0.012 | 0.885 |

| Log(Eβ2M/Ccr) ×104, µg/L fltrate | 0.080 | 0.059 | 0.000425 | 0.993 | 0.182 | 0.013 |

| Smoking | −0.059 | 0.207 | −0.008 | 0.888 | -0.138 | 0.094 |

| Gender | 0.105 | 0.029 | −0.106 | 0.080 | 0.087 | 0.283 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.145 | <0.001 | 0.106 | <0.001 | 0.103 | <0.001 |

| Model 2: DBP | ||||||

| Age, years | 0.121 | 0.006 | 0.114 | 0.045 | −0.035 | 0.675 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.199 | <0.001 | 0.229 | <0.001 | 0.090 | 0.231 |

| Log[(ECd/Ccr) ×105, µg/L filtrate | −0.038 | 0.406 | −0.068 | 0.245 | −0.051 | 0.563 |

| Log(Eβ2M/Ccr) ×104, µg/L fltrate | 0.078 | 0.081 | −0.004 | 0.945 | 0.192 | 0.012 |

| Smoking | −0.041 | 0.406 | 0.007 | 0.903 | −0.132 | 0.125 |

| Gender | 0.054 | 0.286 | 0.034 | 0.585 | 0.074 | 0.379 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.054 | <0.001 | 0.053 | <0.001 | 0.023 | 0.114 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).