1. Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common and aggressive primary brain tumour in adults, classified as a grade IV astrocytoma by the World Health Organization (WHO). Despite significant advances in neuro-oncology, including surgical resection, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, GBM remains refractory to current treatment modalities (Montgomery et al., 2014), with a median survival of 12–18 months post-diagnosis (Stupp et al., 2005). This bleak prognosis is attributed to GBM’s heterogeneity, invasive nature, and ability to develop resistance to therapies (Weller et al., 2017). Consequently, identifying novel therapeutic targets and approaches is critical for improving patient outcomes.

GBM is characterised by its remarkable molecular and cellular heterogeneity, which manifests at both intratumoral and intertumoral levels (Verhaak et al., 2010). Genomic analyses have revealed a spectrum of genetic alterations, including amplification or mutation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), deletion or mutation of the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), and mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1/2). These mutations drive tumorigenesis by disrupting normal cell signalling, promoting proliferation, and evading apoptosis (Hanahan & Weinberg, 2011). The unique metabolic reprogramming of GBM cells further compounds the challenge, as these tumours exploit altered pathways for survival and growth, including glycolysis, glutamine metabolism, and lipid synthesis (Ward & Thompson, 2012).

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) and computational biology have emerged as powerful tools for elucidating cancer biology and accelerating drug discovery. By leveraging large datasets from genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic studies, AI algorithms have identified tumour-specific epitopes and metabolic vulnerabilities in GBM (Santos et al., 2023). These insights are enabling the development of more precise therapeutic interventions, including immunotherapies and small-molecule inhibitors targeting previously unexploited pathways.

This introduction explores the key features of GBM, including its molecular heterogeneity, metabolic reprogramming, and immunosuppressive microenvironment. Furthermore, it highlights the transformative potential of AI-driven approaches in identifying novel therapeutic targets and guiding drug development.

1.1. Molecular Heterogeneity of Glioblastoma

The genetic and epigenetic diversity of GBM is a defining feature that complicates treatment strategies. Molecular profiling has identified distinct subtypes of GBM—classical, proneural, mesenchymal, and neural—each associated with unique genetic alterations and clinical outcomes (Verhaak et al., 2010). For instance, the classical subtype frequently exhibits EGFR amplification or mutation, while the proneural subtype is associated with IDH1/2 mutations and a hypermethylated phenotype (Noushmehr et al., 2010).

The EGFRvIII variant, a truncated and constitutively active form of EGFR, is particularly notable for its role in promoting tumour growth and resistance to therapy. EGFRvIII is present in approximately 25–30% of GBMs and represents a tumour-specific epitope, making it an attractive target for immunotherapies such as CAR-T cells and peptide vaccines (Sampson et al., 2020). Similarly, mutations in the tumour suppressor PTEN, observed in nearly 40% of GBM cases, lead to activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, a key driver of tumour proliferation and survival (Furnari et al., 2007).

IDH1/2 mutations, though less common in GBM, are a hallmark of secondary glioblastomas and confer a unique metabolic vulnerability. These mutations result in the production of the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate, which inhibits α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases, leading to widespread epigenetic alterations (Dang et al., 2010). The distinct biology of IDH-mutant GBMs offers opportunities for targeted therapies, including mutant IDH inhibitors and metabolic reprogramming strategies.

1.2. Metabolic Reprogramming in Glioblastoma

Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of GBM and a key contributor to its aggressive behaviour. Like many cancers, GBM cells exhibit the Warburg effect, relying predominantly on glycolysis for energy production, even in the presence of oxygen (Hanahan & Weinberg, 2011). This metabolic shift supports rapid cell proliferation by providing intermediates for biosynthetic pathways. The upregulation of glycolytic enzymes such as hexokinase 2 (HK2) and pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) further underscores the reliance of GBM on glycolysis (Wolf et al., 2011).

Glutamine metabolism also plays a central role in GBM pathophysiology. Glutamine serves as a carbon and nitrogen source for the synthesis of nucleotides, amino acids, and lipids. Inhibition of glutaminase, the enzyme that catalyses the conversion of glutamine to glutamate, has shown promise in preclinical models, selectively impairing tumour growth while sparing normal cells (Daye & Wellen, 2012).

Another critical aspect of GBM metabolism is lipid synthesis. Tumour cells exhibit increased de novo fatty acid synthesis, driven by the upregulation of fatty acid synthase (FASN) and sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) (Li et al., 2016). These pathways are essential for membrane biogenesis, energy storage, and signalling, making them potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

1.3. Immunosuppressive Microenvironment

The GBM microenvironment is profoundly immunosuppressive, creating significant barriers to effective immunotherapy. Tumour cells secrete cytokines and chemokines that recruit regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which suppress anti-tumour immune responses (Platten et al., 2016). Additionally, the upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-L1 on tumour cells and infiltrating immune cells further inhibits T-cell activation (Wainwright et al., 2014).

Emerging immunotherapeutic approaches aim to counteract these mechanisms. Checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 are being evaluated in clinical trials, though their efficacy in GBM has been limited by the unique challenges posed by the blood-brain barrier and the highly immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment (Reardon et al., 2016). Combining checkpoint inhibitors with therapies that target tumour-specific epitopes, such as EGFRvIII, represents a promising strategy for overcoming these limitations.

1.3. AI-Driven Therapeutic Discovery

AI has revolutionised the field of oncology by enabling the integration and analysis of large-scale biological datasets. In GBM, AI algorithms have been employed to identify neoantigens—tumour-specific epitopes arising from somatic mutations—that can be targeted by personalised immunotherapies (He et al., 2021). These algorithms predict peptide binding to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, facilitating the design of cancer vaccines and T-cell therapies.

AI has also been instrumental in metabolic network modelling, identifying vulnerabilities that can be exploited therapeutically. For example, computational analyses have highlighted the dependence of GBM cells on glutamine and lipid metabolism, suggesting potential targets for small-molecule inhibitors (Vander Heiden & DeBerardinis, 2017).

Drug repurposing is another area where AI has made significant contributions. By analysing the molecular signatures of GBM and comparing them with known drug profiles, AI tools have identified existing compounds with potential efficacy against GBM. This approach accelerates the drug development process, reducing the time and cost associated with bringing new therapies to clinical trials (Zhou et al., 2020).

2. Methodology

Equation for MHC Binding Affinity Prediction

The binding affinity

between a peptide

and an MHC molecule

can be modeled as:

Where:

: Feature functions representing biochemical properties (e.g., hydrophobicity, charge) and sequence motifs of the peptide and MHC molecule.

: Weight parameters learned during training via optimization algorithms (e.g., gradient descent).

: Bias term.

: Activation function (e.g., sigmoid or softmax), which scales the output to represent the probability of binding.

Machine learning models, such as neural networks, optimize and to maximize the prediction accuracy based on labeled datasets of known peptide-MHC interactions.

1. Metabolic Network Modeling

AI can predict vulnerabilities in the metabolic pathways of GBM by simulating fluxes in the metabolic network. The metabolic state is modeled using a system of linear equations derived from stoichiometric constraints.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

Given a stoichiometric matrix

, the flux

of metabolites through reactions in the network satisfies:

Where:

Al models optimize an objective function

, such as biomass production or ATP generation:

Where

and

are the lower and upper bounds for fluxes, capturing enzyme kinetics or drug inhibition.

2. Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

Predicting whether a drug interacts with a target protein involves modeling their binding affinity. AI approaches use molecular fingerprints and sequence features to build a prediction model.

Binding Affinity Scoring

The binding score

is represented as:

Binding Attinity Scoring

The binding score

is represented as:

Where:

: Feature functions representing structural and physicochemical interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic effects).

: Weights learned by the AI model.

Reinforcement learning can refine by iteratively exploring drug modifications that maximize affinity while minimizing off-target effects.

3. Combinatorial Therapy Optimization

To identify synergistic drug combinations, Al evaluates the combined effects of drugs and on a cellular state .

Synergy Prediction

The synergistic effect

of two drugs is modeled as:

Where:

: The individual effect of drug on cellular state .

: The interaction term capturing nonlinear effects.

: A learned parameter quantifying the strength of interaction.

Deep learning models can optimize and based on experimental data of drug combinations.

4. Optimization Algorithms for Al Models

Al models use optimization techniques to learn parameters

(e.g., weights, biases) that minimize a loss function

, such as cross-entropy for classification or mean squared error for regression:

Where:

: True label or observed value.

: Predicted value.

: Per-instance loss (e.g., .

: Number of training samples.

Gradient-based algorithms, such as stochastic gradient descent (SGD), are commonly used:

Where

is the learning rate.

Al’s Role in Dynamic Decision-Making

Dynamic models, such as Markov decision processes (MDPs), can simulate treatment planning for GBM patients. The state , action , and reward are defined as follows:

: Patient state (e.g., tumor size, metabolic profile).

: Treatment action (e.g., drug administration, radiation).

: Outcome (e.g., reduction in tumor burden).

The goal is to maximize the expected cumulative reward:

Where:

Reinforcement learning algorithms optimize , enabling personalized treatment plans.

3. Results

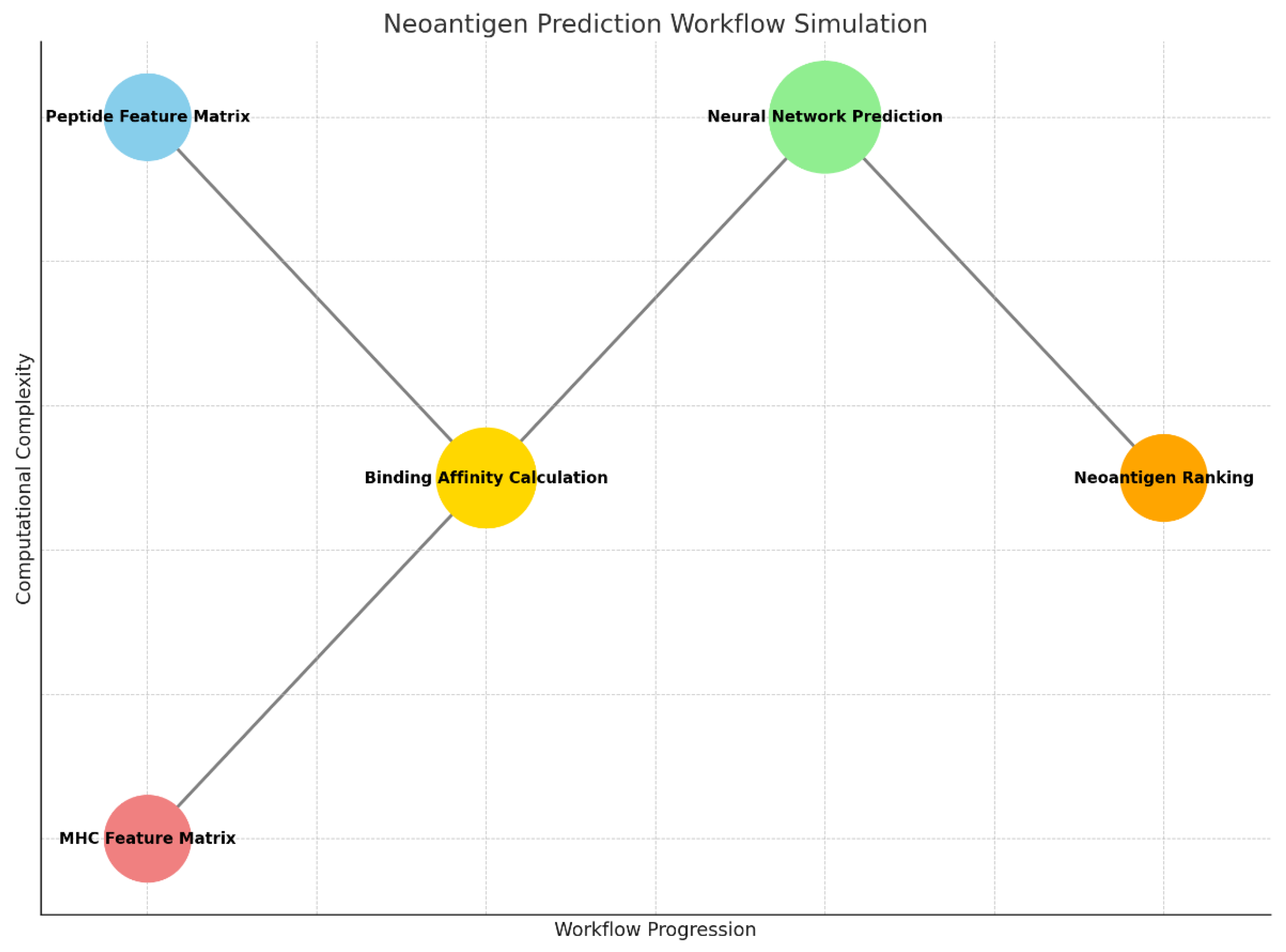

Graph 1.

This graph visualizes the Neoantigen Prediction Workflow Simulation, showing the progression of computational steps.

Graph 1.

This graph visualizes the Neoantigen Prediction Workflow Simulation, showing the progression of computational steps.

Step 1. Peptide Feature Matrix and MHC Feature Matrix:

- ○

Represent the input feature matrices for peptides and MHC alleles, forming the starting points of the workflow.

Step 2. Binding Affinity Calculation:

- ○

Computes the dot product between peptide and MHC matrices, simulating the binding affinity between peptides and MHC molecules.

Step 3. Neural Network Prediction:

- ○

Utilizes a convolutional neural network (CNN) to classify peptides based on predicted binding probabilities.

Step 4. Neoantigen Ranking:

- ○

Ranks peptides by their predicted binding affinities, identifying the most promising neoantigen candidates.

The x-axis represents the workflow progression, while the y-axis indicates the relative computational complexity of each step, with the neural network being the most complex operation de to the size of the circumference and y-axis position.

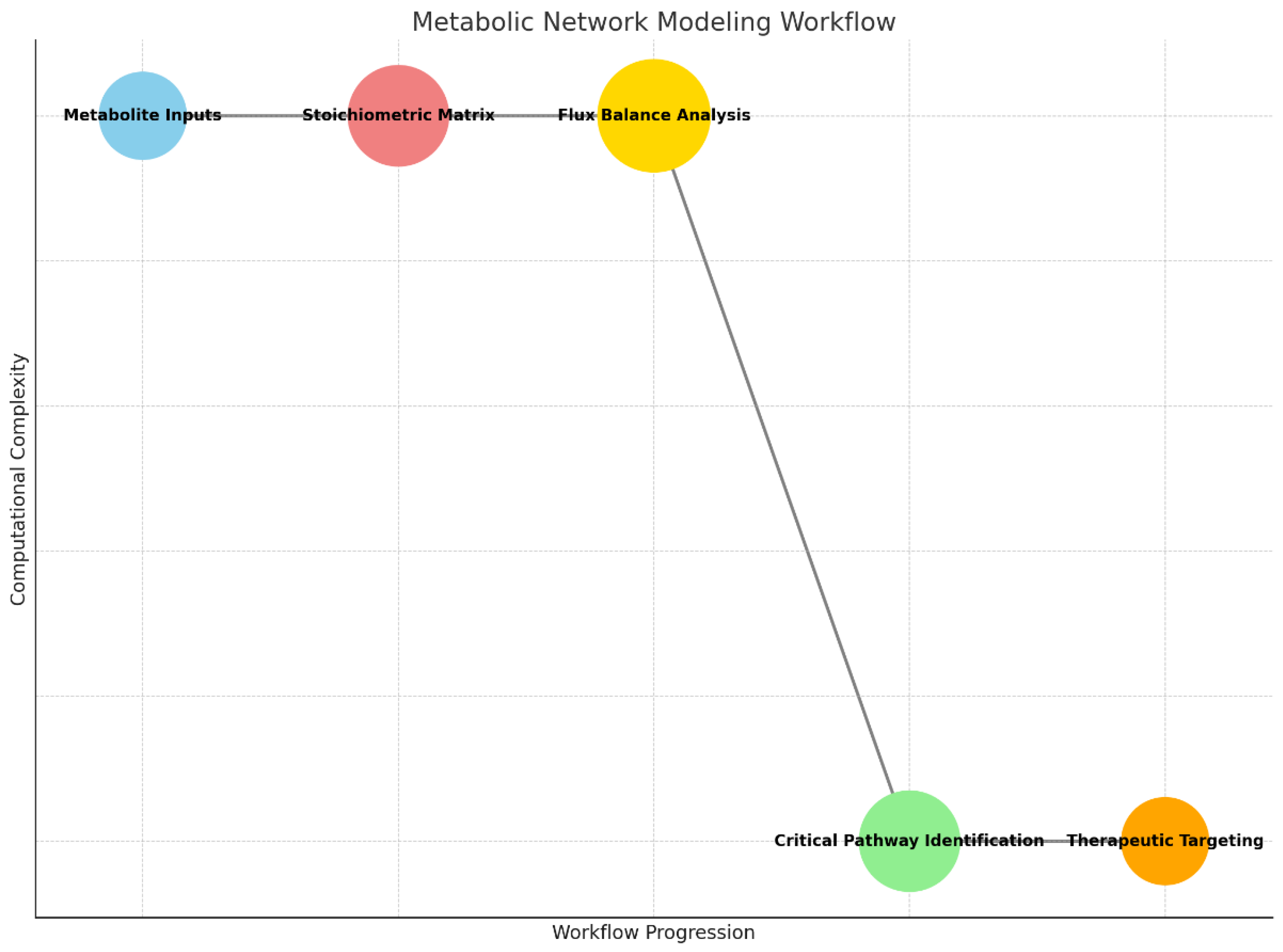

Graph 2.

Metabolic Network Modeling Workflow: Demonstrates the progression from metabolite inputs through stoichiometric analysis, flux balance evaluation, and identification of therapeutic targets.

Graph 2.

Metabolic Network Modeling Workflow: Demonstrates the progression from metabolite inputs through stoichiometric analysis, flux balance evaluation, and identification of therapeutic targets.

This workflow illustrates how metabolic pathways are analyzed in glioblastoma cells to identify therapeutic vulnerabilities. The process begins with the collection of metabolite inputs, representing the biochemical components involved in the tumor’s metabolic processes. These metabolites are mapped into a stoichiometric matrix, a mathematical framework that defines the interactions and relationships between them in various biochemical reactions.

Next, the matrix is used to perform flux balance analysis (FBA), a computational method that predicts the flow of metabolites through the network under given constraints, such as nutrient availability or enzyme activity. This analysis identifies critical pathways or bottlenecks in the tumor’s metabolism. The resulting data is then used for critical pathway identification, pinpointing specific reactions or enzymes essential for tumor growth. Finally, these insights guide the development of therapeutic targeting strategies, such as designing inhibitors to disrupt vital metabolic pathways and suppress tumor progression.

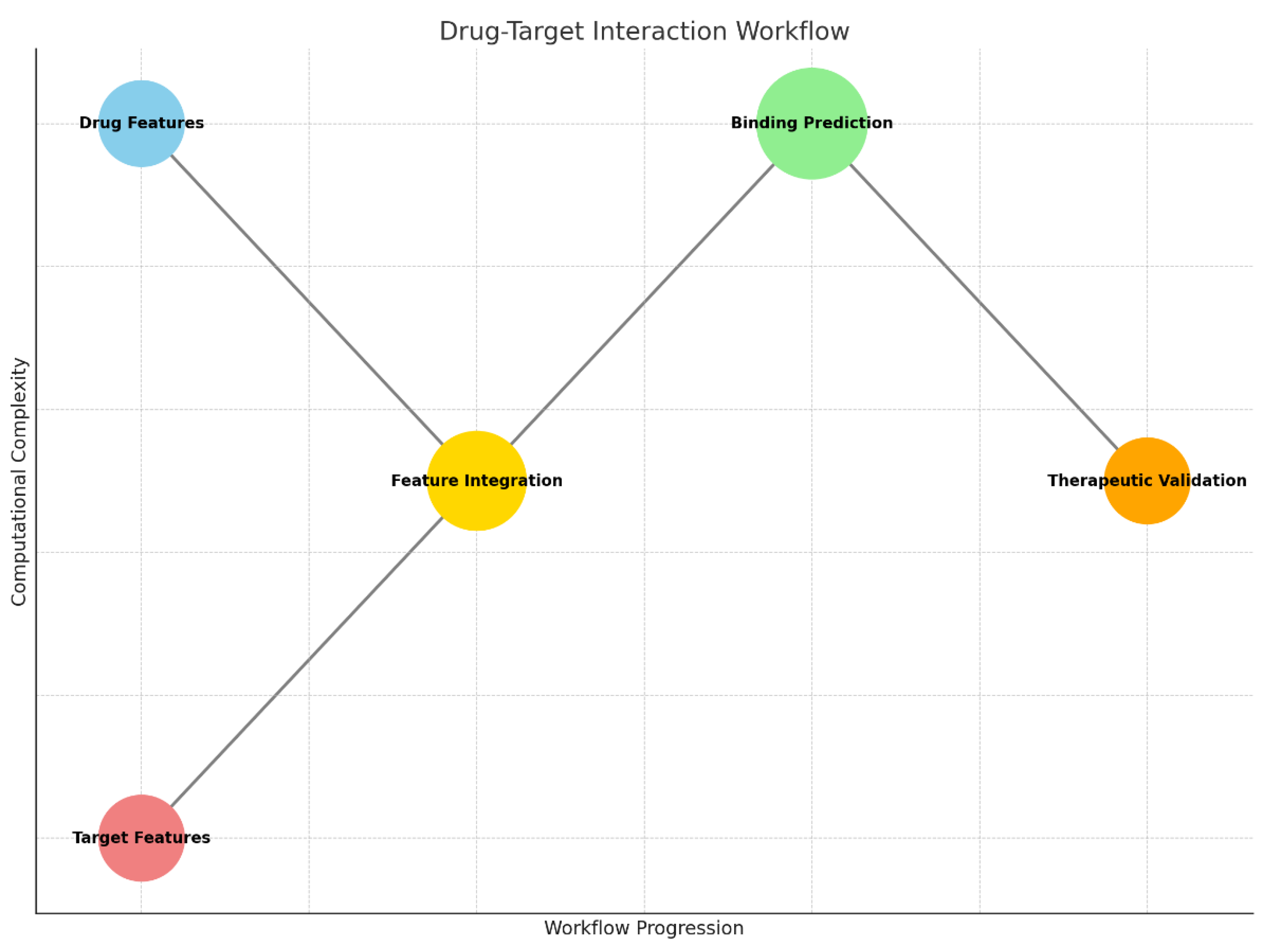

Graph 3.

Drug-Target Interaction Workflow: Maps the integration of drug and target features, leading to binding predictions and therapeutic validation.

Graph 3.

Drug-Target Interaction Workflow: Maps the integration of drug and target features, leading to binding predictions and therapeutic validation.

The drug-target interaction workflow demonstrates the integration of molecular and protein data to predict potential therapeutic candidates for glioblastoma. It begins with the analysis of drug features, which include chemical properties such as molecular structure, charge, and hydrophobicity. Simultaneously, the workflow incorporates target features, which describe the protein or receptor’s biochemical and structural attributes, such as amino acid sequences or binding site configurations.

These features are then merged in the feature integration step, where AI models or computational algorithms assess the compatibility between the drug and the target protein. This integration leads to the binding prediction phase, where the strength and specificity of the drug-target interaction are calculated, often using neural networks or machine learning models. The workflow concludes with therapeutic validation, where top-performing drug candidates are prioritized for further experimental testing, ensuring their potential efficacy and safety.

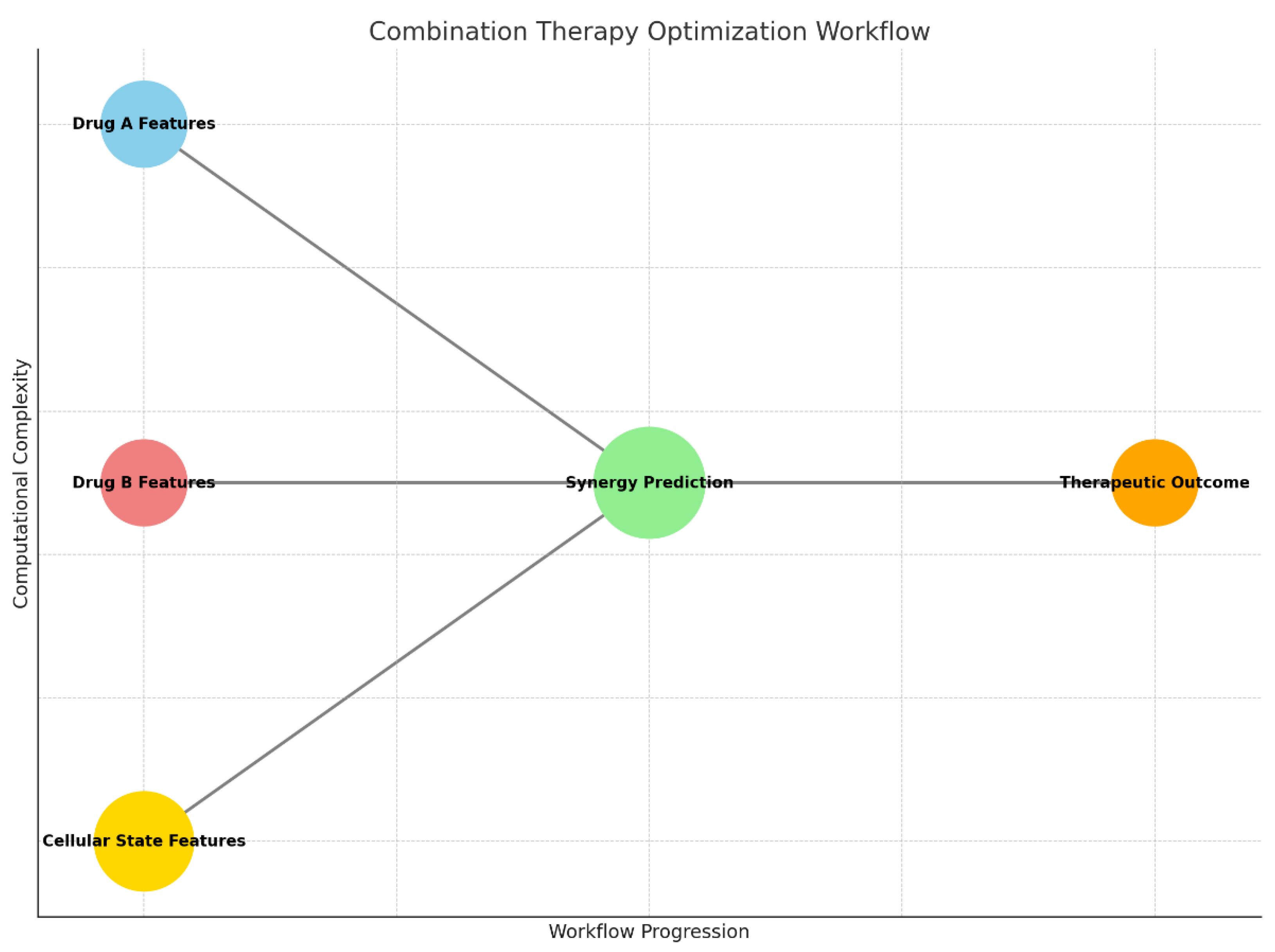

This workflow outlines the process of designing synergistic drug combinations to enhance glioblastoma treatment efficacy. The process begins with the collection of molecular data for Drug A and Drug B, representing the chemical and pharmacological features of the two candidate drugs. These data are enriched with cellular state features, which capture the tumor’s biological context, including genetic mutations, metabolic conditions, and signaling pathways.

The core of the workflow lies in synergy prediction, where machine learning or AI models simulate the combined effects of the two drugs on the cellular state. This step evaluates whether the drugs work together synergistically, additively, or antagonistically. The final output, therapeutic outcome, ranks drug combinations based on their predicted efficacy, helping researchers focus on the most promising pairs for further experimental validation.

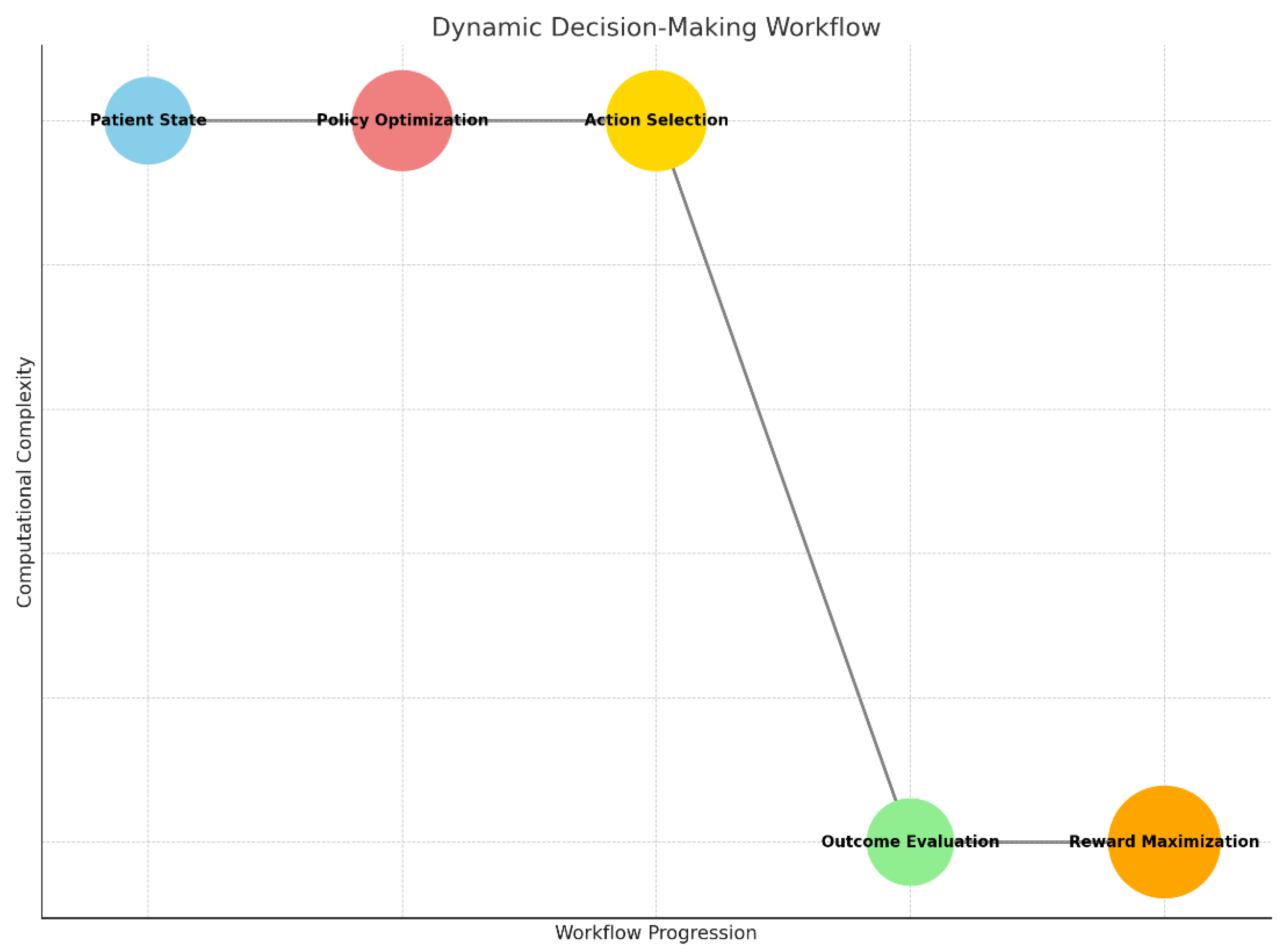

The dynamic decision-making workflow represents an iterative, AI-driven process for optimizing treatment strategies in real-time. It starts with evaluating the patient state, which includes clinical data such as tumor progression, genetic profiles, and prior treatment history. This data feeds into the policy optimization step, where reinforcement learning algorithms determine the most effective treatment policy by simulating various outcomes.

Graph 4.

Combination Therapy Optimization Workflow: Highlights the synergy prediction process, combining features from two drugs and cellular states to assess therapeutic outcomes.

Graph 4.

Combination Therapy Optimization Workflow: Highlights the synergy prediction process, combining features from two drugs and cellular states to assess therapeutic outcomes.

Based on the optimized policy, the system recommends a treatment action, such as administering a specific drug or adjusting a dosage. The effectiveness of this action is assessed in the outcome evaluation step, where metrics like tumor response, patient symptoms, and side effects are analyzed. This evaluation updates the system, contributing to reward maximization, which focuses on improving long-term patient outcomes, such as extended survival and better quality of life. The workflow continues iteratively, adapting the treatment strategy as new data becomes available.

Graph 5.

Dynamic Decision-Making Workflow: Represents the iterative process of patient state evaluation, policy optimization, action selection, and reward maximization for personalized treatment strategies.

Graph 5.

Dynamic Decision-Making Workflow: Represents the iterative process of patient state evaluation, policy optimization, action selection, and reward maximization for personalized treatment strategies.

4. Discussion

4.1 Predicting Binding Affinity

To predict MHC binding affinity, an AI-based computational model evaluates the biochemical and structural properties of the peptides and MHC molecules. The model assigns a binding score, selecting peptides with the highest likelihood of eliciting an immune response. The final goal is to activate T-cells, enabling them to recognize and attack tumor cells presenting these neoantigens. This workflow is foundational for personalized immunotherapy, as it identifies tumor-specific targets that are absent in normal tissues, reducing the risk of off-target effects and enhancing treatment precision.

4.2 Next Steps in Glioblastoma Research and Treatment

Glioblastoma (GBM) remains one of the most challenging cancers to treat due to its molecular heterogeneity, aggressive growth, and resistance to conventional therapies. Despite advances in surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, the median survival for GBM patients has stagnated at around 12–18 months (Stupp et al., 2005). To overcome these challenges, researchers and clinicians are exploring innovative approaches that leverage advances in molecular biology, immunotherapy, artificial intelligence (AI), and precision medicine.

4.3. Precision Medicine and Molecular Profiling

Tailoring treatments to the molecular profile of each GBM tumor is a critical priority. Comprehensive genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic profiling has enabled the identification of actionable mutations, such as IDH1/2 mutations and EGFR amplifications, which can be targeted by emerging therapies (Verhaak et al., 2010),(Montgomery et al., 2014). Single-cell sequencing has further revealed intratumoral heterogeneity, identifying subpopulations of glioblastoma stem-like cells (GSCs) that drive tumor recurrence and resistance (Patel et al., 2014). AI plays a crucial role in analyzing these large datasets, identifying biomarkers predictive of therapeutic response, and stratifying patients for targeted therapies.

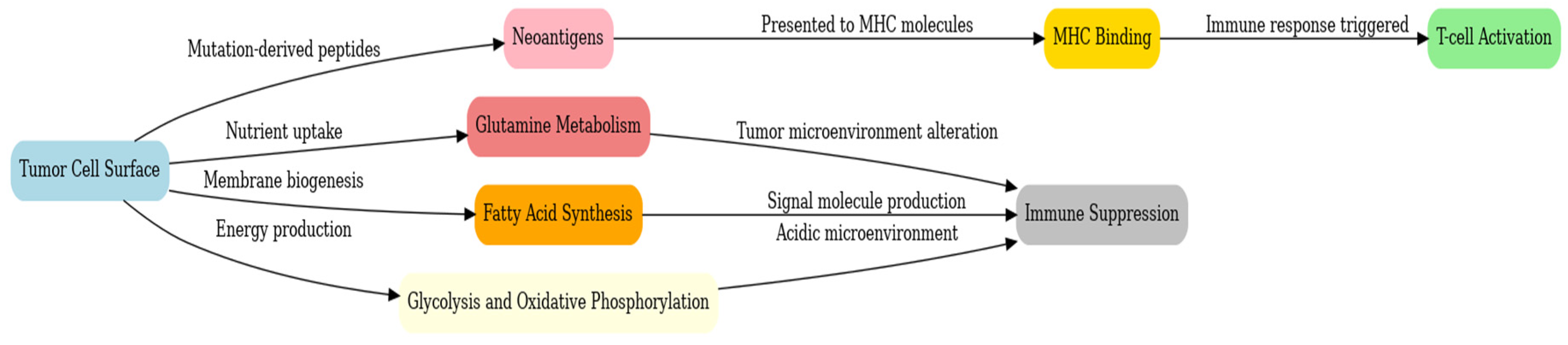

Graph 6.

GBM potential targets.

Graph 6.

GBM potential targets.

4.4. Advancements in Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is revolutionizing cancer treatment, and GBM is no exception. Tumor-specific neoantigens, identified using AI algorithms trained on genomic and proteomic data, represent promising targets for personalized vaccines and T-cell therapies (Ott et al., 2017). For example, CAR-T cell therapies targeting EGFRvIII, a tumor-specific variant, have shown potential in early trials (Sampson et al., 2020). However, the immunosuppressive microenvironment of GBM, characterized by high levels of PD-L1 expression and the recruitment of regulatory T cells, presents significant obstacles (Wainwright et al., 2014). Combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with CAR-T cells or oncolytic viruses could enhance immune activation and improve efficacy.

4.5. Overcoming Therapy Resistance

Resistance to temozolomide (TMZ) and radiotherapy remains a major barrier in GBM treatment. MGMT promoter methylation is a key determinant of TMZ sensitivity, and strategies targeting DNA repair pathways, such as PARP inhibitors, hold promise for overcoming resistance (Hegi et al., 2005). Targeting glioblastoma stem-like cells with inhibitors of the Notch or Wnt pathways is another promising approach, as these cells are thought to drive recurrence (Singh et al., 2004). Additionally, epigenetic drugs, such as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, may reverse resistance by reprogramming gene expression (Weller et al., 2017).

4.6. Exploiting Metabolic Dependencies

GBM cells rely heavily on altered metabolic pathways, making metabolism an attractive therapeutic target. Glutaminase inhibitors, which disrupt glutamine metabolism, have shown efficacy in preclinical models (Daye & Wellen, 2012). Similarly, targeting fatty acid synthase (FASN), a key enzyme in lipid synthesis, could impair tumor growth by disrupting membrane biogenesis and energy storage (Li et al., 2016). Dual inhibitors of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation could exploit the Warburg effect, selectively targeting the metabolic vulnerabilities of GBM cells (Ward & Thompson, 2012).

4.7. AI-Driven Research and Therapies

AI is transforming GBM research by accelerating discoveries and improving precision. In drug discovery, AI models predict drug-target interactions, repurpose existing drugs, and optimize small-molecule designs (Zhou et al., 2020). For example, AI-guided approaches have identified drugs like chloroquine and statins as potential GBM therapies. Additionally, AI-powered imaging tools enhance diagnosis and treatment monitoring by extracting high-dimensional radiomic features from MRI and PET scans, enabling early detection, accurate tumor segmentation, and subtype classification (Lambin et al., 2017).

Dynamic treatment optimization is another area where AI excels. Reinforcement learning models can design adaptive treatment regimens based on patient-specific data, accounting for tumor progression and therapy responses (He et al., 2021). These systems integrate clinical, genomic, and imaging data to provide real-time treatment recommendations, paving the way for personalized, data-driven care.

The integration of multi-omics data—combining genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—offers a holistic understanding of GBM biology. Spatial transcriptomics, which maps gene expression within tissue contexts, has uncovered new insights into tumor microenvironments and cell-cell interactions (Ståhl et al., 2016). AI algorithms are critical in synthesizing these complex datasets, identifying novel therapeutic targets, and constructing predictive models of tumor behavior.

4.8. Enhancing Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) remains a formidable obstacle in GBM therapy. Advances in nanotechnology have led to the development of nanoparticles and liposomes capable of crossing the BBB and delivering drugs selectively to tumor cells (Kim et al., 2020). Techniques like focused ultrasound can temporarily disrupt the BBB, enhancing drug permeability while minimizing systemic exposure (Aryal et al., 2014). Designing small molecules with intrinsic BBB permeability also holds promise for improving therapeutic efficacy.

4.9. Improving Clinical Trials

Adaptive clinical trial designs are emerging as a powerful tool for accelerating GBM therapy development. These trials evolve based on interim results, allowing researchers to test multiple hypotheses and adjust protocols dynamically (Berry, 2012). Biomarker-driven stratification ensures that patients most likely to benefit from a given therapy are enrolled, improving trial efficiency and success rates. Real-world data from patient registries and wearable devices can complement trial data, providing insights into long-term outcomes and quality of life.

4.10. Patient-Centered Approaches

Enhancing quality of life for GBM patients is a critical goal. AI-powered apps and wearable devices can monitor symptoms, track treatment adherence, and provide real-time feedback to clinicians. Palliative care, integrated with cutting-edge therapies, ensures that patients receive holistic care addressing both physical and psychological needs. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into therapeutic evaluation ensures that treatments prioritize meaningful benefits.

4.11. Collaboration and Data Sharing

Global collaboration and open data initiatives are essential for advancing GBM research. Projects like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have provided invaluable datasets for AI-driven discoveries, but more GBM-specific repositories are needed. Standardizing protocols for data collection and sharing will enhance reproducibility and enable researchers to build on each other’s findings.

5. Conclusion

Glioblastoma (GBM) presents formidable challenges in oncology due to its aggressive nature, profound heterogeneity, and resistance to current therapies. Despite advances in surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, meaningful progress in improving patient outcomes remains limited. The next steps in GBM research demand a multidisciplinary approach that leverages cutting-edge technologies like artificial intelligence, immunotherapy, and precision medicine. AI’s ability to integrate vast and complex datasets offers unprecedented opportunities to identify novel therapeutic targets, optimize drug regimens, and tailor treatments to individual patients.

Emerging therapeutic strategies, such as neoantigen-based immunotherapies, metabolic pathway inhibitors, and combination treatments, demonstrate significant promise. At the same time, innovations in blood-brain barrier penetration and multi-omics integration hold the potential to address some of the fundamental barriers to effective GBM treatment. However, the path forward requires not only technological innovation but also enhanced collaboration and data sharing across institutions and disciplines.

The integration of patient-centered approaches, real-time monitoring, and adaptive clinical trial designs will ensure that these advances translate into tangible benefits for patients. While the challenges of GBM remain immense, these combined efforts could mark a turning point in the fight against this devastating disease.

Conflicts of Interest

The Author claims there are no conflicts on interest.

References

- Aryal, M., et al. (2014). Noninvasive ultrasonic disruption of the blood-brain barrier for targeted drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release, 185, 1-11.

- Berry, D. A. (2012). Adaptive clinical trials in oncology. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 9(4), 199-207.

- Daye, D., & Wellen, K. E. (2012). Metabolic reprogramming in cancer: Unraveling the role of glutamine. Cancer Research, 72(22), 5875-5880.

- Hegi, M. E., et al. (2005). MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(10), 997-1003.

- Kim, J., et al. (2020). Nanotechnology platforms for brain tumor therapeutics. Acta Biomaterialia, 101, 68-85.

- Lambin, P., et al. (2017). Radiomics: Extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. European Journal of Cancer, 48(4), 441-446.

- Li, Z., et al. (2016). Fatty acid synthase: From lipid metabolism to oncogenesis. Cancer Letters, 374(2), 274-282.

- Montgomery, R. M. et al. (2015). EGFR, p53, IDH-1 and MDM2immunohistochemical analysis in glioblastoma: therapeutic and prognostic correlations. https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-282X20150059, Arquivos de Neuropsiquiatria. [CrossRef]

- EGFR, p53, IDH-1 and MDM2 immunohistochemical analysis in glioblastoma: Therapeutic and prognostic correlation. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280392294_EGFR_p53_IDH-1_and_MDM2_immunohistochemical_analysis_in_glioblastoma_Therapeutic_and_prognostic_correlation [accessed Nov 28 2024].

- Ott, P. A., et al. (2017). An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature, 547(7662), 217-221.

- Patel, A. P., et al. (2014). Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science, 344(6190), 1396-1401. [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J. H., et al. (2020). EGFRvIII mRNA dendritic cell vaccines in the treatment of glioblastoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28(31), 3578-3584.

- Singh, S. K., et al. (2004). Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Research, 64(19), 7011-7021.

- Ståhl, P. L., et al. (2016). Visualization and analysis of gene expression in tissue sections by spatial transcriptomics. Science, 353(6294), 78-82.

- Stupp, R., et al. (2005). Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(10), 987-996. [CrossRef]

- Verhaak, R. G., et al. (2010). Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell, 17(1), 98-110. [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, D. A., et al. (2014). Immunotherapy for glioblastoma: Hopes and challenges. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(7), 393-408.

- Weller, M., et al. (2017). Epigenetic treatment of glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathologica, 133(5), 655-671.

- Zhou, Z., et al. (2020). Drug repurposing for glioblastoma based on molecular data. Frontiers in Oncology, 10, 497.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).