Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

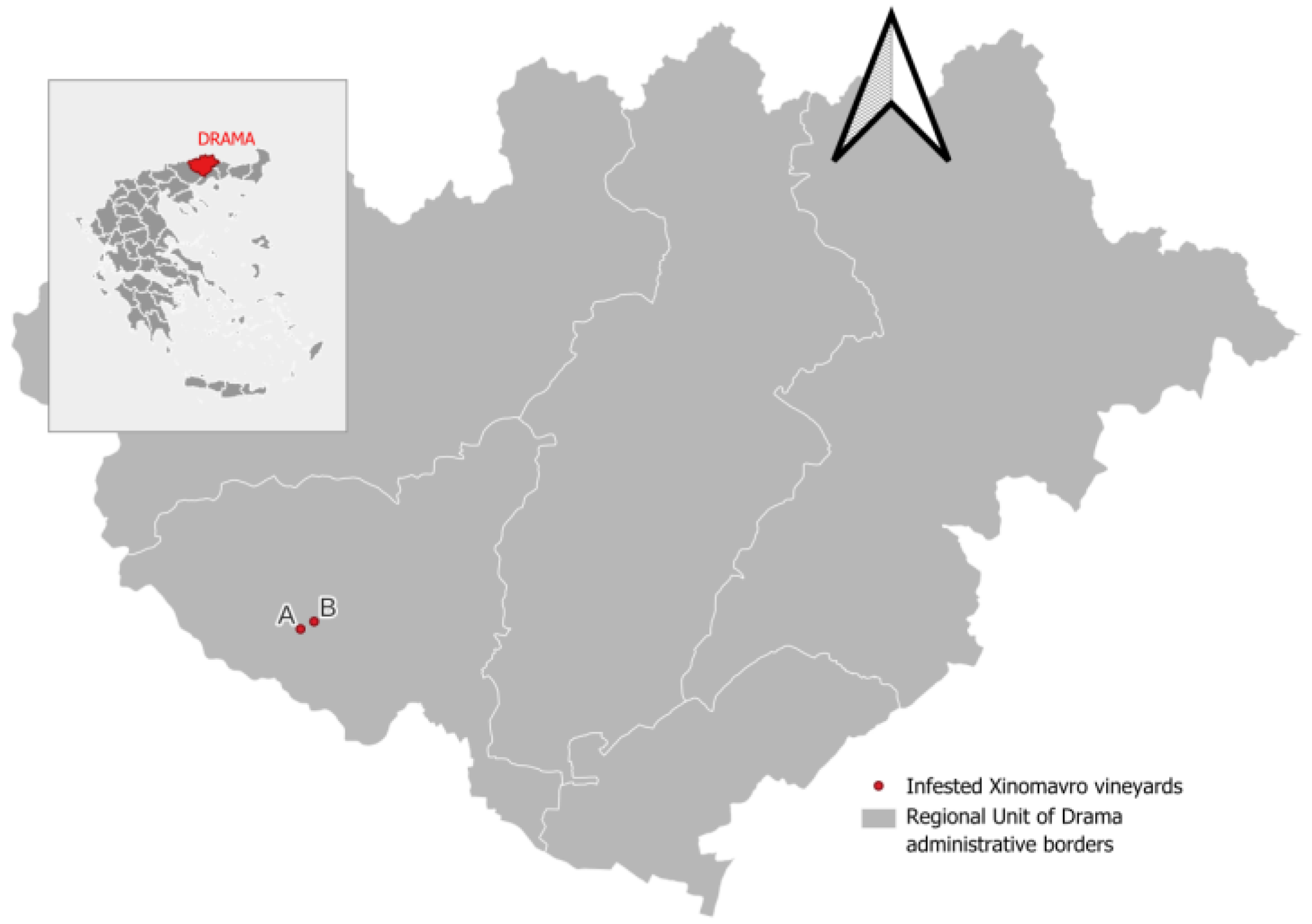

2.1. Population Density Monitoring and Sampling Locations

2.2. Species Identification

2.3. Assessment of the Damage Extent

3. Results

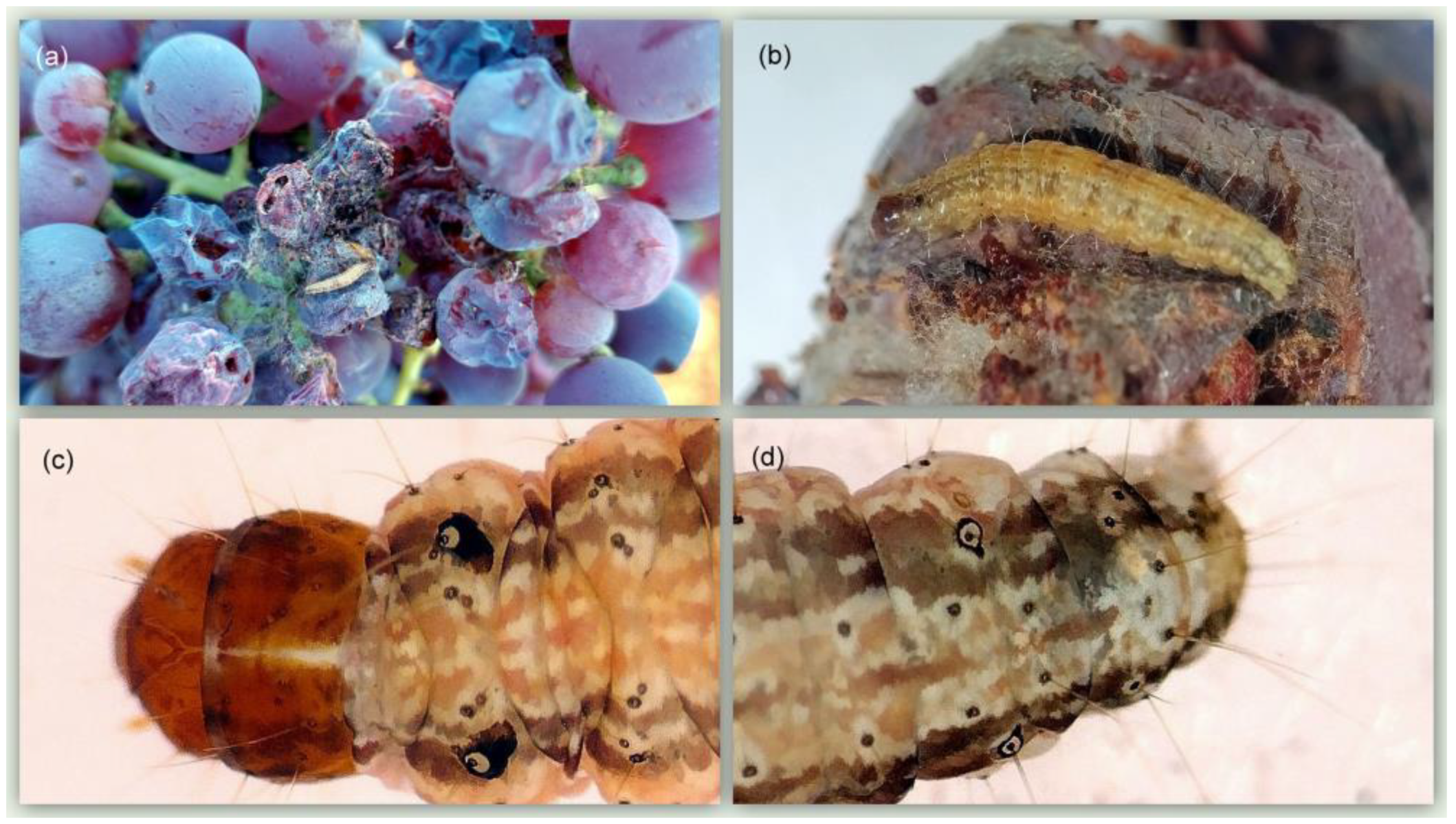

3.1. Species Identification

3.2. Monitoring of Flight in Pheromone Traps

3.3. Description of the Damage

3.4. Estimation of the Damage Level

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aitken, A.D. A Key to the Larvae of Some Species of Phycitinae (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae) Associated with Stored Products, and of Some Related Species. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1963, 54, 175–188. [CrossRef]

- Triplehorn, C.A.; Johnson, N.F.; Borror, D.J. Borror and DeLong’s Introduction to the Study of Insects; 7. ed., [3. Nachdr.].; Thompson Brooks/Cole: Belmont, CA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-03-096835-8.

- Liu, C.; Yang, M.; Li, M.; Jin, Z.; Yang, N.; Yu, H.; Liu, W. Climate Change Facilitates the Potentially Suitable Habitats of the Invasive Crop Insect Ectomyelois ceratoniae (Zeller). Atmosphere 2024, 15, 119. [CrossRef]

- Pachkin, A.; Kremneva, O.; Leptyagin, D.; Ponomarev, A.; Danilov, R. Light Traps to Study Insect Species Diversity in Soybean Crops. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2337. [CrossRef]

- Simoglou, K.B.; Karataraki, A.; Roditakis, N.E.; Roditakis, E. Euzophera bigella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) and Dasineura Oleae (F. Low) (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae): Emerging Olive Crop Pests in the Mediterranean? J Pest Sci 2012, 85, 169–177. [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.A., 2009. Lepidoptera (Moths, Butterflies). In: Cardι, R.T., Resh, V.H., 2009. Encyclopedia of insects, 2nd ed. ed. Elsevier/Academic Press, Amsterdam London.

- Benelli, G.; Lucchi, A.; Anfora, G.; Bagnoli, B.; Botton, M.; Campos-Herrera, R.; Carlos, C.; Daugherty, M.P.; Gemeno, C.; Harari, A.R.; et al. European Grapevine Moth, Lobesia botrana Part I: Biology and Ecology. Entomologia 2023a, 43, 261–280. [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Lucchi, A.; Anfora, G.; Bagnoli, B.; Botton, M.; Campos-Herrera, R.; Carlos, C.; Daugherty, M.P.; Gemeno, C.; Harari, A.R.; et al. European Grapevine Moth, Lobesia botrana Part II: Prevention and Management. Entomologia 2023b, 43, 281–304. [CrossRef]

- Varikou, K.; Birouraki, A.; Bagis, N.; Kontodimas, D.C. Effect of Temperature on the Development and Longevity of Planococcus ficus (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 2010, 103, 943–948. [CrossRef]

- Karamaouna, F.; Menounou, G.; Stathas, G.J.; D.N. Avtzis. First record and molecular identifi cation of the parasitoid Anagyrus sp. near pseudococci Girault (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) in Greece - Host size preference for the vine mealybug Planococcus ficus (Signoret) (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae). Hellenic Plant Protection Journal 2011, 4, 45–52, Available at: https://www.hppj.gr/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Volume-4-Issue-2-July-2011.pdf.

- Evangelou, V.; Lytra, I.; Krokida, A.; Antonatos, S.; Georgopoulou, I.; Milonas, P.; Papachristos, D.P. Insights into the Diversity and Population Structure of Predominant Typhlocybinae Species Existing in Vineyards in Greece. Insects 2023, 14, 894. [CrossRef]

- Roditakis, N.E. First Record of Frαnkliniellα occidentαlis in Greece. Entomologia Hellenica 1991, 9, 77. [CrossRef]

- Roditakis, E.; Roditakis, N.E. Assessment of the Damage Potential of Three Thrips Species on White Variety Table Grapes—In Vitro Experiments. Crop Protection 2007, 26, 476–483. [CrossRef]

- Bagnoli, B.; Lucchi, A. Bionomics of Cryptoblabes gnidiella (Milliθre) (Pyralidae Phycitinae) in Tuscan vineyards. IOBC/WPRS Bulletin 2001, 24(7), 79–84. Available at: https://iobc-wprs.org/product/iobc-wprs-bulletin-vol-24-7-2001/.

- Lucchi, A.; Ricciardi, R.; Benelli, G.; Bagnoli, B. What Do We Really Know on the Harmfulness of Cryptoblabes gnidiella (Milliθre) to Grapevine? From Ecology to Pest Management. Phytoparasitica 2019, 47, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, R.; Di Giovanni, F.; Cosci, F.; Ladurner, E.; Savino, F.; Iodice, A.; Benelli, G.; Lucchi, A. Mating Disruption for Managing the Honeydew Moth, Cryptoblabes gnidiella (Milliθre), in Mediterranean Vineyards. Insects 2021, 12, 390. [CrossRef]

- French Institute of Vine and Wine. The economic cost of Cryptoblabes gniediella. Institut Franηais de la Vigne et du Vin, 2024. Accessed on 26-10-2024. Available at: https://www.vignevin.com/article/le-cout-economique-de-cryptoblabes-gniediella/.

- Avidov, Z.; Gothilf, S. Observations on the honeydew moth (Cryptoblabes gnidiella Milliere) in Israel. Ktavim 1960, 10(3–4), 109–124. Available at: https://download.ceris.purdue.edu/file/2088.

- Dawidowicz, Ł.; Rozwałka, R. Honeydew Moth Cryptoblabes gnidiella (MILLIΘRE, 1867) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae): An Adventive Species Frequently Imported with Fruit to Poland. Polish Journal of Entomology 2016, 85, 181–189. [CrossRef]

- Elnagar, H. Population Dynamic of Honeydew Moth, Cryptoblabes gnidiella Miller in Vineyards Orchards. Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences. A, Entomology 2018, 11, 73–78. [CrossRef]

- Velez-Gavilan, J. Cryptoblabes gnidiella (honeydew moth). CABI, 2022, 16381. Accessed on 13-10-2024. Available at: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/10.1079/cabicompendium.16381.

- Karsholt, O.; Razowski, J. The Lepidoptera of Europe: A Distributional Checklist; Apollo books: Stenstrup, 1996; ISBN 978-87-88757-01-9.

- Neunzig, H.H. The Moths of America, North of Mexico. Fasc. 15,2: Fasc. 15. Pyraloidea / H. H. Neunzig Pyralidae (Pt.), Phycitinae (Pt; Neunzig, H.H., Ed.; Classey: London, 1986; ISBN 978-0-933003-01-9.

- Ioriatti, C.; Lucchi, A.; Varela, L.G. Grape Berry Moths in Western European Vineyards and Their Recent Movement into the New World. In Arthropod Management in Vineyards:; Bostanian, N.J., Vincent, C., Isaacs, R., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2012; pp. 339–359 ISBN 978-94-007-4031-0.

- Elekcioglu, N.Z.; Olculu, M. Pest, predator and parasitoid species in persimmon orchards in the eastern Mediterranean region of Turkey, with new records. Fresenius Environmental Bulletin 2017, 26, 5170-5176.

- Harari, A.R.; Zahavi, T.; Gordon, D.; Anshelevich, L.; Harel, M.; Ovadia, S.; Dunkelblum, E. Pest Management Programmes in Vineyards Using Male Mating Disruption. Pest Management Science 2007, 63, 769–775. [CrossRef]

- Keçeci̇, M. The Population Dynamic of Honeydew Moth [Cryptoblabes Gnidiella Mill. (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae)] in Vineyard in Antalya. Mediterranean Agricultural Sciences 2021, 34, 169–173. [CrossRef]

- Vidart, M.V.; Mujica, M.V.; Calvo, M.V.; Duarte, F.; Bentancourt, C.M.; Franco, J.; Scatoni, I.B. Relationship between Male Moths of Cryptoblabes gnidiella (Milliθre) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) Caught in Sex Pheromone Traps and Cumulative Degree-Days in Vineyards in Southern Uruguay. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 258. [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.19.3) -Computer software. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I 273 from diverse Metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299.

- Avtzis, D.N.; Markoudi, V.; Mizerakis, V.; Devalez, J.; Nakas, G.; Poulakakis, N.; Petanidou, T. The Aegean Archipelago as Cradle: Divergence of the Glaphyrid Genus Pygopleurus and Phylogeography of P. Foina. Systematics and Biodiversity 2021, 19, 346–358. [CrossRef]

- Sadras, V.O.; Petrie, P.R. Climate Shifts in South-Eastern Australia: Early Maturity of Chardonnay, Shiraz and Cabernet Sauvignon Is Associated with Early Onset Rather than Faster Ripening: Climate Shifts and Grapevine Ripening. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 2011, 17, 199–205. [CrossRef]

- Zumbado-Ulate, H.; Schartel, T.E.; Simmons, G.S.; Daugherty, M.P. Assessing the Risk of Invasion by a Vineyard Moth Pest Guild. NB 2023, 86, 169–191. [CrossRef]

- Moschos, T.; Souliotis, C.; Broumas, T.; Kapothanassi, V. Control of the European Grapevine moth Lobesia botrana in Greece by the Mating Disruption Technique: A Three-Year Survey. Phytoparasitica 2004, 32, 83–96. [CrossRef]

- Daane, K.M.; Yokota, G.Y.; Walton, V.M.; Hogg, B.N.; Cooper, M.L.; Bentley, W.J.; Millar, J.G. Development of a Mating Disruption Program for a Mealybug, Planococcus ficus, in Vineyards. Insects 2020, 11, 635. [CrossRef]

- Mondani, L.; Palumbo, R.; Tsitsigiannis, D.; Perdikis, D.; Mazzoni, E.; Battilani, P. Pest Management and Ochratoxin A Contamination in Grapes: A Review. Toxins 2020, 12, 303. [CrossRef]

- Ringenberg, R.; Botton, M.; Garcia, M.S.; Nondillo, A. Biologia Comparada e Exigκncias Tιrmicas de Cryptoblabes gnidiella Em Dieta Artificial. Pesq. agropec. bras. 2005, 40, 1059–1065. [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, N. Creating a Degree-Day Model of Honeydew Moth [Cryptoblabes Gnidiella (Mill., 1867) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae)] in Pomegranate Orchards. Turkish Journal of Entomology 2018, 53–62. [CrossRef]

- Wysoki, M.; Ben Yehuda, S.; Rosen, D. Reproductive Behavior of the Honeydew Moth, Cryptoblabes gnidiella. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development 1993, 24, 217–223. [CrossRef]

- Acin, P. Management of the honeydew moth by mating disruption in vineyard. IOBC/WPRS Bulletin 2019, 146, 28–31. Available at: https://iobc-wprs.org/product/iobc-wprs-bulletin-vol-146-2019-copy/.

- Reineke, A.; Thiιry, D. Grapevine Insect Pests and Their Natural Enemies in the Age of Global Warming. J Pest Sci 2016, 89, 313–328. [CrossRef]

- Caffarra, A.; Rinaldi, M.; Eccel, E.; Rossi, V.; Pertot, I. Modelling the Impact of Climate Change on the Interaction between Grapevine and Its Pests and Pathogens: European Grapevine Moth and Powdery Mildew. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2012, 148, 89–101. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).