Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

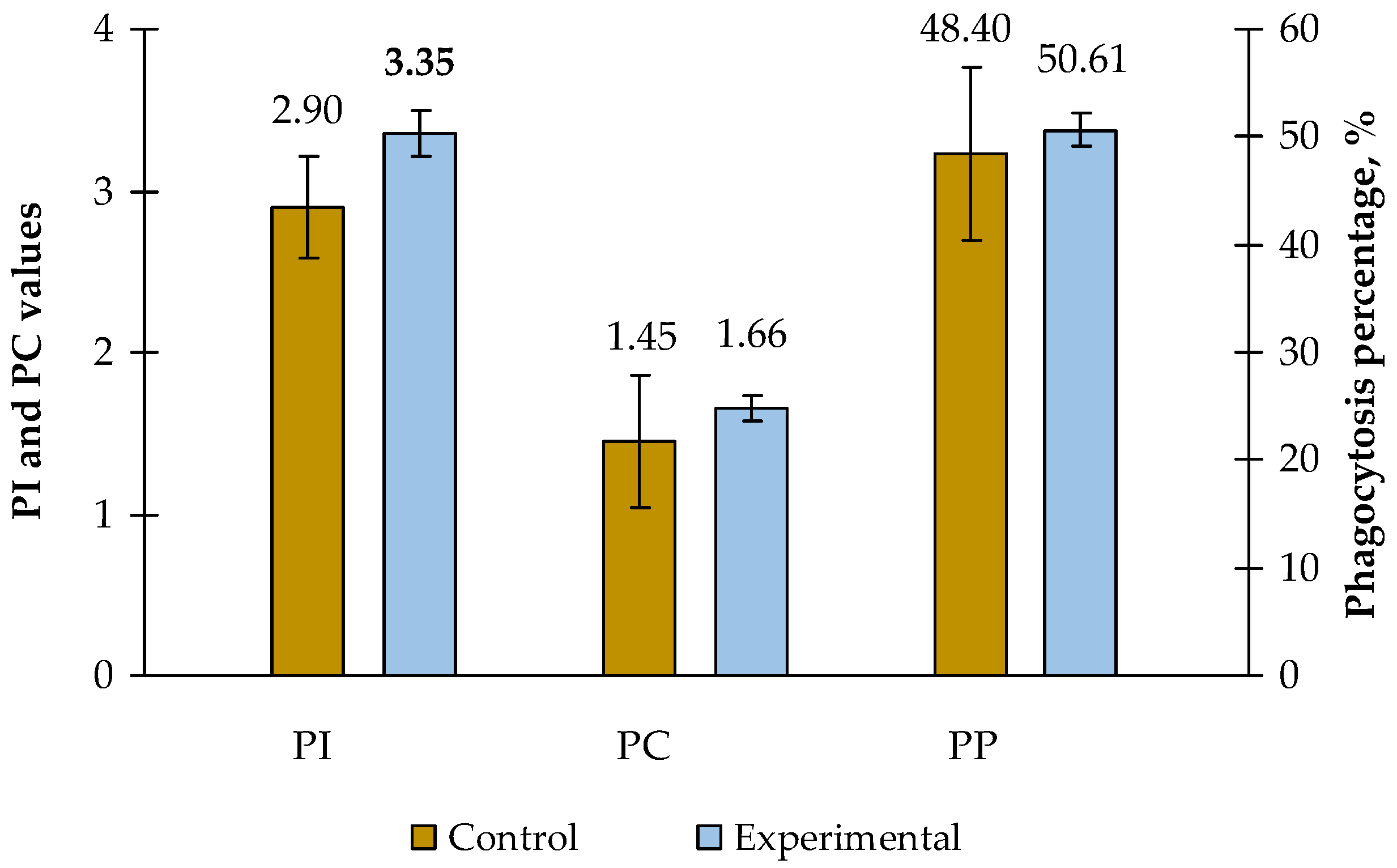

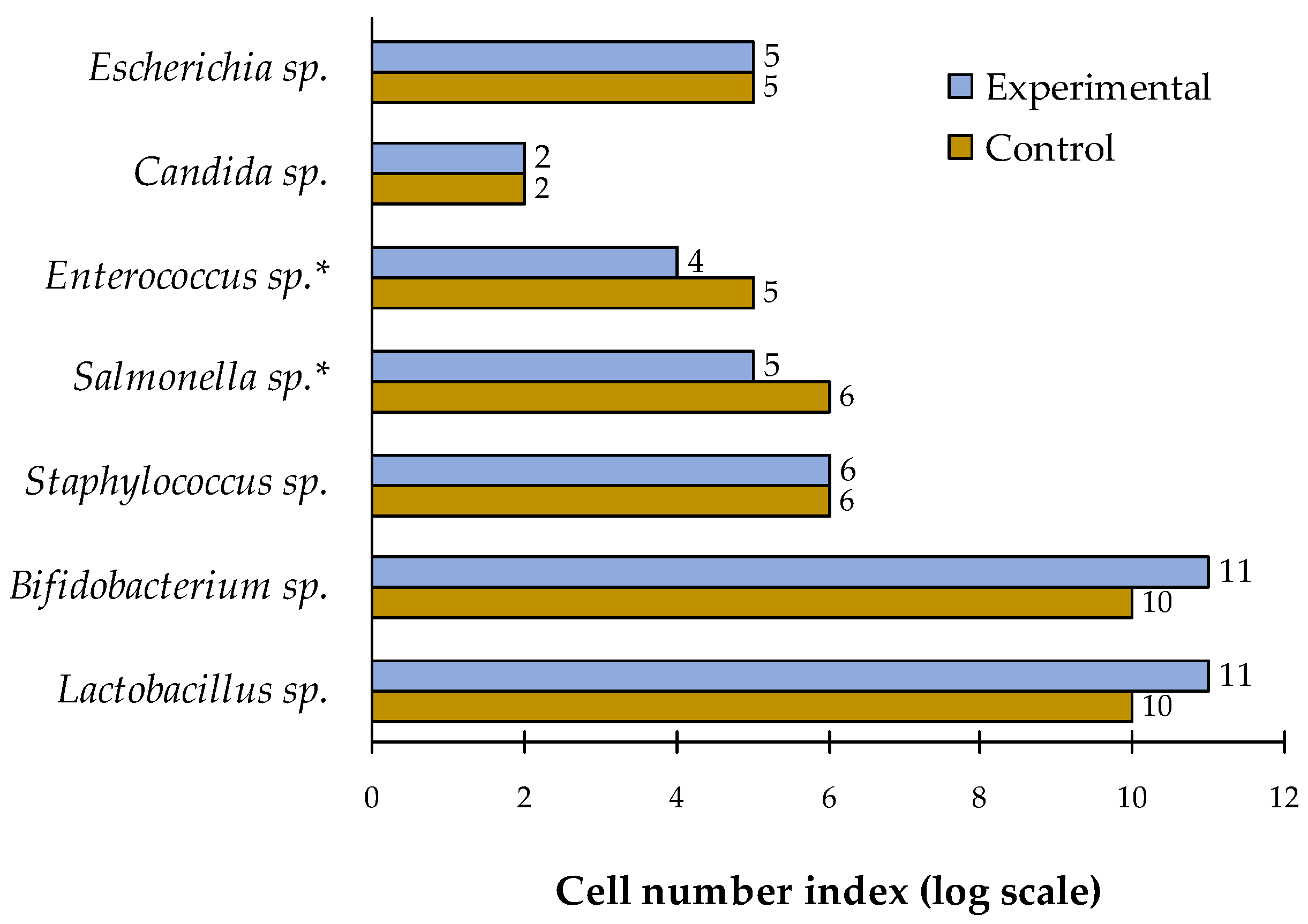

The effect of carotene-containing probiotic feed additive on the digestibility and assimilation of feed and zootechnical indices of growing piglets was studied. The study involved 40 crossbred male piglets (F1: Duroc‒Landrace) with a live weight of 20‒25 kg. Two groups were formed, each with 20 piglets, based on the principle of analogues. The experiment was performed during a fattening period and lasted 30 days. The experimental group received a complete feed supplemented with the studied feed additive that resulted in a 6.8% increase in the daily weight gain compared to the control group. Piglets from the experimental group showed increased digestibility coefficients for dry matter (+2.2%), organic matter (+2.5%), and protein (+2.1%) compared to the control group. Additionally, the experimental group demonstrated a trend towards increase in the protein fractions in blood serum as well as the same trend for the phagocytic activity, phagocytic index, and phagocytic count. The study also demonstrated a significant reduction in the number of Salmonella and Enterococcus cells in the experimental group. The obtained results allow us to recommend this feed additive for use in the diet of fattened piglets.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nutrient Media for Isolation of Microorganisms

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Diet and Conditions

2.4. Determination of Average Daily Weight Gain

2.5. Balance Experiment

2.6. Determination of Hematological Parameters

2.7. Determination of the Retinol Content in Blood Serum

2.8. Determination of Non-Specific Resistance Parameters

2.9. Study of the Microflora of the Gastrointestinal Tract

2.10. Statistical Data Treatment

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Feed Additive on the Average Daily Weight Gain of Growing Fattening Pigs

3.2. Balance Experiment Results

3.3. Effect of Feed Additive on Biochemical, Morphological, and Immunological Characteristics of the Blood of Fattened Piglets

3.4. FA Effect on Nonspecific Resistance Indices

3.5. Microbiological Profiling of the Intestine Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, F.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Ren, S.; Guo, L.; Chen, Z.; Hrabchenko, N.; Wu, J.; Yu, J. Mechanisms and applications of probiotics in prevention and treatment of swine diseases. Porc. Health Manag. 2023, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.W.; Gormley, A.; Jang, K.B.; Duarte, M.E. Invited review ‒ current status of global pig production: an overview and research trends. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Jensen, J.D. Sustainability implications of rising global pork demand. Anim. Front. 2022, 12, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluske, J.R.; Turpin, D.L.; Kim, J.C. Gastrointestinal tract (gut) health in the young pig. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 4, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayrle, H.; Mevissen, M.; Kaske, M.; Nathues, H.; Gruetzner, N.; Melzig, M.; Walkenhorst, M. Medicinal plants – prophylactic and therapeutic options for gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases in calves and piglets? A systematic review. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Cho, J.; Keum, G.B.; Kwak, J.; Doo, H.; Choi, Y.; Kang, J.; Kim, H.; Chae, Y.; Kim, E.S.; Song, M.; Kim, H.B. Investigation of the impact of multi-strain probiotics containing Saccharomyces cerevisiae on porcine production. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2024, 66, 876–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, J.; Truffin, D.; Majdeddin, M.; Van Poucke, M.; Van Liefferinge, E.; Van Noten, N.; Vandaele, M.; Van Kerschaver, C.; Degroote, J.; Peelman, L.; Linder, P. Gluconic acid improves performance of newly weaned piglets associated with alterations in gut microbiome and fermentation. Porcine Health Manag. 2023, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Duarte, M.E.; Sevarolli Loftus, A.; Kim, S.W. Intestinal health of pigs upon weaning: challenges and nutritional intervention. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 628258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, B.; Nyachoti, C.M. Husbandry practices and gut health outcomes in weaned piglets: A review. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 3, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeser, A.J.; Pohl, C.S.; Rajput, M. Weaning stress and gastrointestinal barrier development: implications for lifelong gut health in pigs. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 3, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Gong, T.; Jiang, Z.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y. The role of probiotics in alleviating post-weaning diarrhea in piglets from the perspective of intestinal barriers. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 883107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, V.; Duk Ha, B.; Kibria, S.; Kim, I.H. Effect of low-nutrient-density diet with probiotic mixture (Bacillus subtilis ms1, B. licheniformis SF5-1, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) supplementation on performance of weaner pigs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 2022, 106, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeser, A.J.; Blikslager, A.T. Mechanisms of porcine diarrhoeal disease. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2007, 231, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahindi, R.K.; Htoo, J.K.; Nyachoti, C.M. Effect of dietary lysine content and sanitation conditions on performance of weaned pigs fed antibiotic-free diets. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 94, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.D. Impact of antibiotic use in the swine industry. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 19, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewulf, J.; Joosten, P.; Chantziaras, I.; Bernaerdt, E.; Vanderhaeghen, W.; Postma, M.; Maes, D. Antibiotic use in European pig production: less is more. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekagul, A.; Tangcharoensathien, V.; Yeung, S. Patterns of antibiotic use in global pig production: A systematic review. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2019, 7, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.; Khalid, A.; Fu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Khan, S.; Wang, Z. Potential of Bacillus velezensis as a probiotic in animal feed: a review. J. Microbiol. 2021, 59, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardeau, M.; Lehtinen, M.J.; Forssten, S.D.; Nurminen, P. Importance of the gastrointestinal life cycle of Bacillus for probiotic functionality. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 2570–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.A.; To, E.; Fakhry, S.; Baccigalupi, L.; Ricca, E.; Cutting, S.M. Defining the natural habitat of Bacillus spore-formers. Res. Microbiol. 2009, 160, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, B.; Li, T.; Kim, I.H. Effects of supplementing growing-finishing pig diets with Bacillus spp. probiotic on growth performance and meat-carcass grade quality traits. Rev. Bras. Zootecn. 2016, 45, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devyatkin, V.; Mishurov, A.; Kolodina, E. Probiotic effect of Bacillus subtilis B-2998D, B-3057D, and Bacillus licheniformis B-2999D complex on sheep and lambs. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2021, 8, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhounde, S.; Adéoti, K.; Mounir, M.; Giusti, A.; Refinetti, P.; Out, A.; Effa, E.; Ebenso, B.; Adetimirin, V.O.; Barceló, J.M.; Thiare, O.; Rabetafika, H.N.; Razafindralambo, H.L. Applications of probiotic-based multi-components to human, animal and ecosystem health: concepts, methodologies, and action mechanisms. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łubkowska, B.; Jeżewska-Frąckowiak, J.; Sroczyński, M.; Dzitkowska-Zabielska, M.; Bojarczuk, A.; Skowron, P.M.; Cięszczyk, P. Analysis of industrial Bacillus species as potential probiotics for dietary supplements. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luise, D.; Bosi, P.; Raff, L.; Amatucci, L.; Virdis, S.; Trevisi, P. Bacillus spp. probiotic strains as a potential tool for limiting the use of antibiotics, and improving the growth and health of pigs and chickens. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 801827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Jinno, C.; Kim, K.; Wu, Z.; Tan, B.; Li, X.; Whelan, R.; Liu, Y. Dietary Bacillus spp. enhanced growth and disease resistance of weaned pigs by modulating intestinal microbiota and systemic immunity. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smołucha, G.; Steg, A.; Oczkowicz, M. The role of vitamins in mitigating the effects of various stress factors in pigs breeding. Animals 2024, 14, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomhoff, H.K.; Smeland, E.B.; Erikstein, B.; Rasmussen, A.M.; Skrede, B.; Skjønsberg, C.; Blomhoff, R. Vitamin A is a key regulator for cell growth, cytokine production, and differentiation in normal B cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 23988–23992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Qi, G.; Brand, D.; Zheng, S.G. Role of vitamin A in the immune system. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamor, E.; Fawzi, W.W. Effects of vitamin a supplementation on immune responses and correlation with clinical outcomes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 18, 446–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amimo, J.O.; Michael, H.; Chepngeno, J.; Raev, S.A.; Saif, L.J.; Vlasova, A.N. Immune impairment associated with vitamin A deficiency: insights from clinical studies and animal model research. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W. Review: Vitamin A supply in swine production: current science and practical considerations. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2023, 39, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W. The role of vitamin A in non-ruminant immunology. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4, 1197802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepngeno, J.; Amimo, J.O.; Michael, H.; Jung, K.; Raev, S.; Lee, M.V.; Damtie, D.; Mainga, A.O.; Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J.; Rotavirus, A. Inoculation and oral vitamin A supplementation of vitamin A deficient pregnant sows enhances maternal adaptive immunity and passive protection of piglets against virulent rotavirus A. Viruses 2022, 14, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langel, S.N.; Paim, F.C.; Alhamo, M.A.; Lager, K.M.; Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J. Oral vitamin A supplementation of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infected gilts enhances IgA and lactogenic immune protection of nursing piglets. Vet. Res. 2019, 50, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amimo, J.O.; Michael, H.; Chepngeno, J.; Raev, S.A.; Saif, L.J.; Vlasova, A.N. Immune impairment associated with vitamin a deficiency: insights from clinical studies and animal model research. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhomychev, A.I. Determination of the phagocyte activity of the blood as a method of studying the effect of toxic substances and during medical examinations of workers. Gig. Sanit. 1960, 25, 77–84, [in Russian]. [Google Scholar]

- Nekrasov, R.V.; Ivanov, G.A.; Chabaev, M.G.; Zelenchenkova, A.A.; Bogolyubova, N.V.; Nikanova, D.A.; Sermyagin, A.A.; Bibikov, S.O.; Shapovalov, S.O. Effect of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) bat on health and productivity performance of dairy cows. Animals 2022, 12, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalova, N.A.; Pleshkov, V.A. Hematological profile of pig breeds of universal productivity direction. Int. Res. J. 2022, 2, 175–179, [in Russian]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingmongkolchai, S.; Panbangred, W. In vitro evaluation of candidate Bacillus spp. for animal feed. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 63, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marubashi, T.; Gracia, M.I.; Vilà, B.; Bontempo, V.; Kritas, S.K.; Piskoríková, M. The efficacy of the probiotic feed additive Calsporin® (Bacillus subtilis C-3102) in weaned piglets: Combined analysis of four different studies. J. Appl. Anim. Nutr. 2012, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Kim, I.H. Effect of Bacillus subtilis C-3102 spores as a probiotic feed supplement on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, diarrhea score, intestinal microbiota, and excreta odor contents in weanling piglets. Animals 2022, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priest, F.G. Extracellular enzyme synthesis in the genus Bacillus. Bacteriol. Rev. 1977, 41, 711–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvan, O.; Gavrish, I.; Lebedev, S.V.; Korotkova, A.M.; Miroshnikova, E.P.; Serdaeva, V.A.; Bykov, A.V.; Davydova, N.O. Effect of probiotics on the basis of Bacillus subtilis and Bifidobacterium longum on the biochemical parameters of the animal organism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Chem. Med. 2018, 25, 2175–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magomedaliev, I.M.; Nekrasov, R.V.; Chabaev, M.G.; Javakhia, V.V.; Glagoleva, E.V.; Kartashov, M.I. Influence of probiotic complex on productive qualities and metabolic processes in growing fattening young pigs. Agrarian Sci. 2020, 1, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, E. Weight gain by gut microbiota manipulation in productive animals. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 106, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantas, D.; Papatsiros, V.; Tassis, P.; Giavasis, I.; Bouki, P.; Tzika, E. A feed additive containing Bacillus toyonensis (Toyocerin®) protects against enteric pathogens in postweaning piglets. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 118, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Number of animals per group | Ration1 |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological experiment (25 days) | ||

| 1 (control) | 20 | SMF |

| 2 (experimental) | 20 | SMF + FA (1.0 kg/ton) |

| Registration period of the balance experiment (5 days) | ||

| 1 (control) | 10 | SMF |

| 2 (experimental) | 10 | SMF + FA (1.0 kg/ton) |

| Parameter | Piglet group | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Experimental | |

| Duration of the experiment, days | 30 | |

| Live weight at the beginning of the experiment, kg | 25.3 ± 0.8 | 25.2 ± 0.7 |

| Live weight at the end of the experiment, kg | 44.3 ± 1.3 | 47.3 ± 1.2* |

| Absolute live weight gain, kg | 18.9 ± 2.2 | 22.1 ± 1.2* |

| Average daily weight gain, g | 630 ± 52 | 730 ± 22* |

| Live weight, % of the control | 100.0 | 106.8 |

| Nutrient | Piglet group | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Experimental | |

| Dry matter | 75.13 ± 0.76 | 76.82 ± 0.66* |

| Organic matter | 73.34 ± 0.70 | 75.23 ± 0.72* |

| Protein | 75.60 ± 0.57 | 77.20 ± 0.43* |

| Nutrient parameter | Piglet group | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Experimental | |

| Received with the fodder, g | 58.40 ± 0.5 | 58.90 ± 0.5 |

| Released with feces, g | 4.91 ± 0.55 | 4.98 ± 0.40 |

| Digested, g | 53.48 ± 0.65 | 53.93 ± 0.27 |

| Released with urine, g | 13.92 ± 0.33 | 13.71 ± 0.19 |

| Accumulated in the body, g | 39.50 ± 0.30 | 40.25 ± 0.23* |

| Utilized, % of: | ||

| Received nitrogen | 67.63 ± 0.35 | 69.36 ± 0.24 |

| Digested nitrogen | 73.85 ± 1.16 | 74.63 ± 1.22 |

| Nutrient parameter | Calcium | Phosphorus | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piglet group | Piglet group | |||

| Control | Experimental | Control | Experimental | |

| Received with the fodder, g | 14.30 ± 0.2 | 14.30 ± 0.2 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | 9.0 ± 0.1 |

| Released with feces, g | 7.03 ± 0.38 | 7.22 ± 0.38 | 5.80 ± 0.38 | 5.92 ± 0.15 |

| Released with urine, g | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.20 ± 0.10* | 2.21 ± 0.11 | 1.55 ± 0.07* |

| Accumulated in the body, g | 6.49 ± 0.30 | 6.61 ± 0.29 | 1.14 ± 0.22 | 1.60 ± 0.17* |

| Utilized, % of received amount | 45.38 ± 1.05 | 46.71 ± 1.03 | 12.67 ± 1.11 | 18.50 ± 1.22 |

| Parameter | Piglet group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Experimental | Reference values1 | |

| Total protein, g/L | 64.72±1.82 | 66.8±2.22 | 58.0–85.0 |

| Albumin, g/L | 24.08±3.06 | 25.01±2.05 | 20.0–45.0 |

| Globulin, g/L | 40.94±2.18 | 41.74±4.56 | 23.0–54.0 |

| Urea, mmole/L | 6.24±0.86 | 6.36±0.46 | 4.9–8.5 |

| Creatinine, mmole/L | 130.02±25.12 | 135.25±14.07 | 113.0–172.0 |

| Total bilirubin, μmole/L | 5.14±0.12 | 7.29±0.05 | 0.3–8.2 |

| ALT, ME/L | 41.22±26.22 | 47.06±8.90 | 30.0–94.0 |

| AST, ME/L | 34.25±9.09 | 35.13±6.27 | 13.0–97.0 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), mmole/L | 246.30±70.00 | 256.01±40.10 | 74.0–454.0 |

| Carotene, mmole/L | 0.65±0.12 | 0.79±0.09* | – |

| Vitamin A, mmole/L | 0.39±0.03 | 0.45±0.04* | – |

| Cholesterol, mmole/L | 2.20±0.53 | 2.10±0.41 | 2.1–3.5 |

| Triglycerides, mmole/L | 0.33±0.08 | 0.29±0.10 | 0.12–0.60 |

| Phospholipids, mmole/L | 3.61±0.10 | 3.39±0.08 | – |

| Glucose, mmole/L | 4.50±0.67 | 4.71±0.92 | 3.7–6.4 |

| Calcium, mmole/L | 1.98±0.16 | 2.01±0.09 | 1.8–3.7 |

| Phosphorus, mmole/L | 2.13±0.14 | 2.39±0.26 | 2.3–4.8 |

| Leucocytes, 109/L | 10.10±1.91 | 9.10±2.60 | 8.0–16.2 |

| Erythrocytes, 1012/L | 6.90±0.24 | 6.20±0.27 | 6.0–7.5 |

| Haemoglobin, г/L | 124.78±32.41 | 124.85±5.5 | 90.0–130.0 |

| Hematocrit,% | 46.72±5.48 | 47.12±4.35 | 40.0–50.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).