Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Evidence for ECCO2R

3. Key Areas of Future Research

3.1 Hemolysis

3.2 Thrombosis and Bleeding

4. CO2 Removal Rate Performance

4.1 Cannula

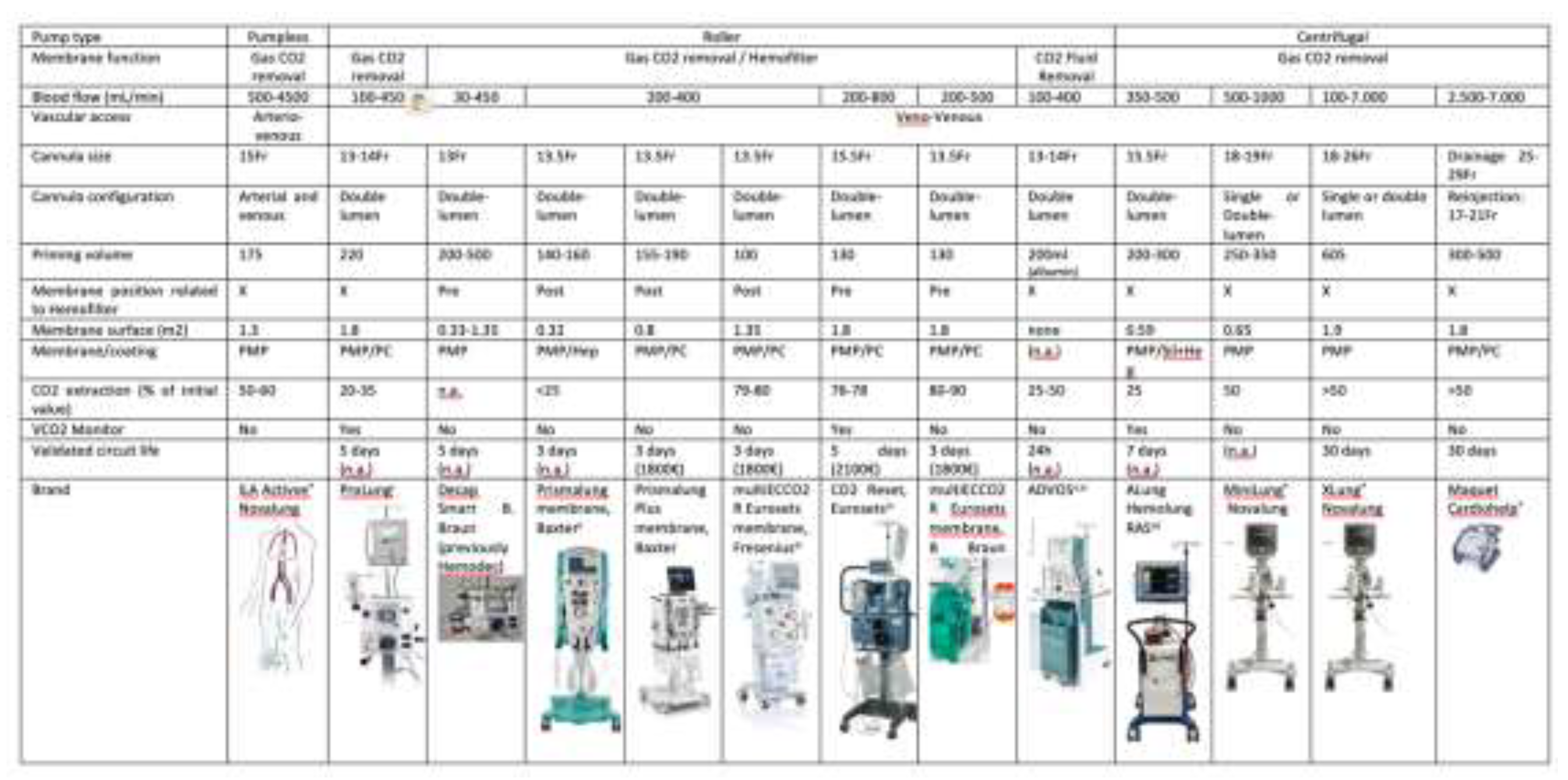

4.2 Pumps, Membranes and Circuits

4.2.1. Pumps

4.2.2. Membranes

4.2.2.1 Materials

4.2.2.2 Novel Surfaces for ECCO2R

4.2.2.3 Measuring device VCO2 to assess membrane performance

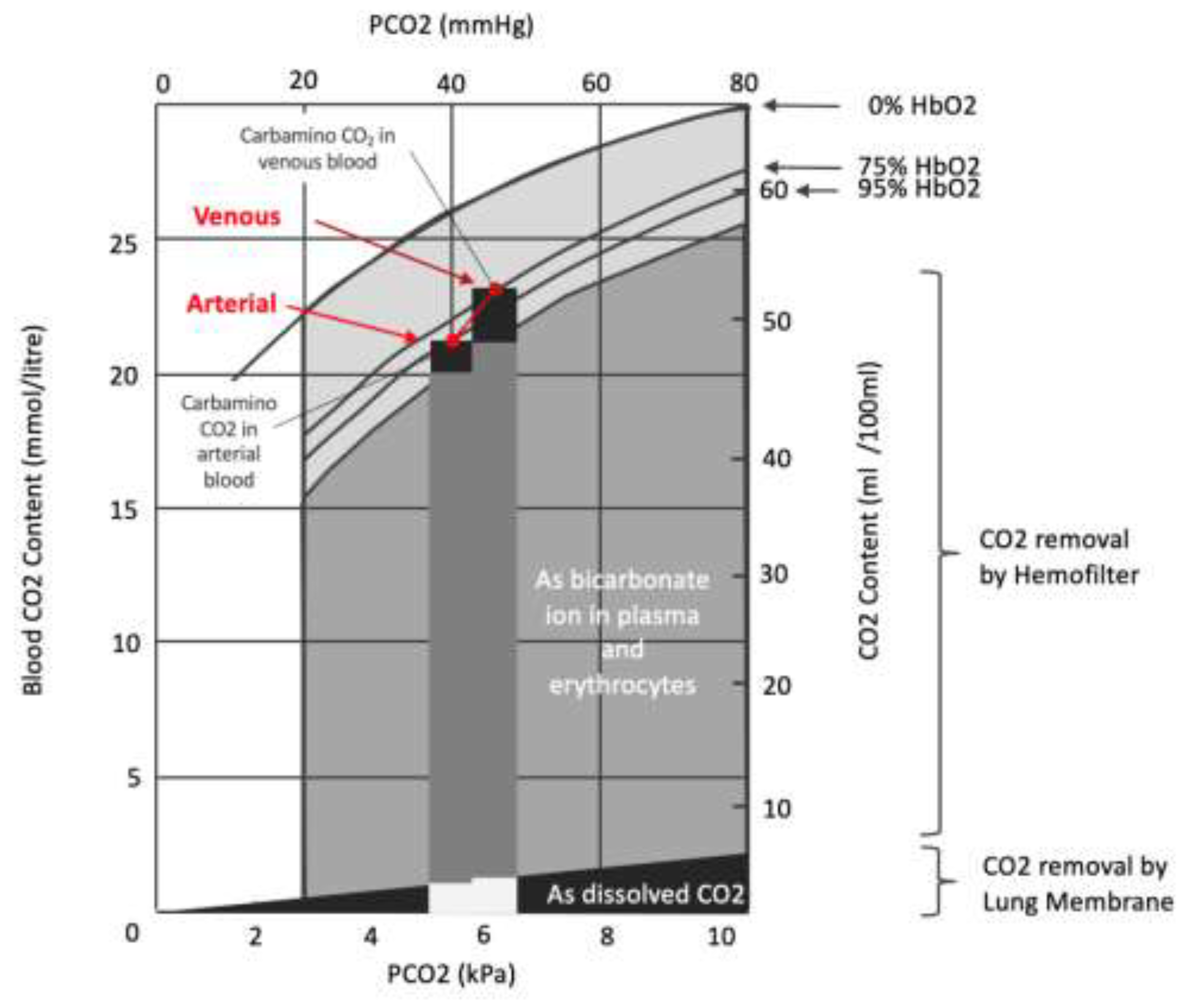

4.3. Combined CO2 Removal (“Lung Dialysis”) with renal support

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ohtake, S.; Kawashima, Y.; Hirose, H.; Matsuda, H.; Nakano, S.; Kaku, K.; Okuda, A. Experimental evaluation of pumpless arteriovenous ECMO with polypropylene hollow fiber membrane oxygenator for partial respiratory support. . 1983, 29, 237–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bein, T.; Weber, F.; Philipp, A.; Prasser, C.; Pfeifer, M.; Schmid, F.-X.; Butz, B.; Birnbaum, D.; Taeger, K.; Schlitt, H.J. A new pumpless extracorporeal interventional lung assist in critical hypoxemia/hypercapnia*. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 1372–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bein, T.; Zimmermann, M.; Hergeth, K.; Ramming, M.; Rupprecht, L.; Schlitt, H.J.; Slutsky, A.S. Pumpless extracorporeal removal of carbon dioxide combined with ventilation using low tidal volume and high positive end-expiratory pressure in a patient with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anaesthesia 2009, 64, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattinoni, L.; Pesenti, A.; Mascheroni, D.; Marcolin, R.; Fumagalli, R.; Rossi, F.; Lapichino, G.; Romagnoli, G.; Uziel, L.; Agostoni, A.; et al. Low-frequency positive-pressure ventilation with extracorporeal CO2 removal in severe acute respiratory failure. JAMA 1986, 256, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Bein, T.; Arlt, M.; Philipp, A.; Rupprecht, L.; Mueller, T.; Lubnow, M.; Graf, B.M.; Schlitt, H.J. Pumpless extracorporeal interventional lung assist in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective pilot study. Crit. Care 2009, 13, R10–R10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Bein, T.; Philipp, A.; Ittner, K.; Foltan, M.; Drescher, J.; Weber, F.; Schmid, F.-X. Interhospital transportation of patients with severe lung failure on pumpless extracorporeal lung assist. Br. J. Anaesth. 2006, 96, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Hoeper, M.M.; Bein, T.; Simon, A.R.; Gottlieb, J.; Wisser, W.; Frey, L.; Van Raemdonck, D.; Welte, T.; Haverich, A.; et al. Interventional Lung Assist: A New Concept of Protective Ventilation in Bridge to Lung Transplantation. Asaio J. 2008, 54, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, S.C.; Paramasivam, K.; Oram, J.; Bodenham, A.R.; Howell, S.J.; Mallick, A. Pumpless extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal for life-threatening asthma. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, A.; Elliot, S.; McKinlay, J.; Bodenham, A. Extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal using the Novalung® in a patient with intracranial bleeding. Anaesthesia 2006, 62, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwischenberger, J.B.; Alpard, S.K. Artificial lungs: a new inspiration. Perfusion 2002, 17, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwischenberger, J.B.; Alpard, S.K.; Tao, W.; Deyo, D.J.; Bidani, A. Percutaneous extracorporeal arteriovenous carbon dioxide removal improves survival in respiratory distress syndrome: A prospective randomized outcomes study in adult sheep. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2001, 121, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwischenberger, J.B.; Savage, C.; Witt, S.A.; Alpard, S.K.; Harper, D.D.; Deyo, D.J. Arterio-venous CO2 removal (AVCO2R) perioperative management: rapid recovery and enhanced survival. J. Investig. Surg. 2002, 15, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terragni, P.; Maiolo, G.; Ranieri, V.M. Role and potentials of low-flow CO2 removal system in mechanical ventilation. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2012, 18, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchinsky, A.I.; Jordan, B.S.R.; Regn, D.; Necsoiu, C.; Federspiel, W.J.; Morris, M.J.; Cancio, L.C. Respiratory dialysis: Reduction in dependence on mechanical ventilation by venovenous extracorporeal CO2 removal*. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 39, 1382–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberto, F.; Pugliese, F.; D'Alio, A.; Perrella, S.; D'Auria, B.; Ianni, S.; Anile, M.; Venuta, F.; Coloni, G.; Pietropaoli, P. Extracorporeal Removal CO2 Using a Venovenous, Low-Flow System (Decapsmart) in a Lung Transplanted Patient: A Case Report. Transplant. Proc. 2009, 41, 1412–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas, V.J.; Lynch, J.E.; Ates, R.; Miller, L.; Zwischenberger, J.B. Venovenous Carbon Dioxide Removal in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Asaio J. 2009, 55, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrington, K.L.; McRae, K.M.; Gardaz, J.-. .-P.; Dunnill, M.S.; Sykes, M.K.; Wilkinson, A.R. A randomized comparison of total extracorporeal CO2 removal with conventional mechanical ventilation in experimental hyaline membrane disease. Intensiv. Care Med. 1989, 15, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livigni, S.; Maio, M.; Ferretti, E.; Longobardo, A.; Potenza, R.; Rivalta, L.; Selvaggi, P.; Vergano, M.; Bertolini, G. Efficacy and safety of a low-flow veno-venous carbon dioxide removal device: results of an experimental study in adult sheep. Crit. Care 2006, 10, R151–R151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearden, P.D.; Federspiel, W.J.; Morley, S.W.; Rosenberg, M.; Bieniek, P.D.; Lund, L.W.; Ochs, B.D. Respiratory dialysis with an active-mixing extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal system in a chronic sheep study. Intensiv. Care Med. 2012, 38, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.P.; Kon, Z.N.; Evans, C.; Wu, Z.; Iacono, A.T.; McCormick, B.; Griffith, B.P. Ambulatory veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: Innovation and pitfalls. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 142, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, S.; Braune, S.A.; Engel, M.; Nierhaus, A.; Frings, D.; Ebelt, H.; Uhrig, A.; Metschke, M.; Wegscheider, K.; Suttorp, N.; et al. Avoiding invasive mechanical ventilation by extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal in patients failing noninvasive ventilation. Intensiv. Care Med. 2012, 38, 1632–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extracorporeal lung support technologies - bridge to recovery and bridge to lung transplantation in adult patients: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2010;10(5):1-47.

- Engel M, Albrecht H. Use of Extracorporeal CO2 Removal to Avoid Invasive Mechanical Ventilation in Hypercapnic Coma and Failure of Noninvasive Ventilation. J Pulm Respir Med. 2016;6(3). [CrossRef]

- Hilty, M.P.; Riva, T.; Cottini, S.R.; Kleinert, E.-M.; Maggiorini, A.; Maggiorini, M. Low flow veno-venous extracorporeal CO2 removal for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017, 83, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braune, S.; Sieweke, A.; Brettner, F.; Staudinger, T.; Joannidis, M.; Verbrugge, S.; Frings, D.; Nierhaus, A.; Wegscheider, K.; Kluge, S. The feasibility and safety of extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal to avoid intubation in patients with COPD unresponsive to noninvasive ventilation for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure (ECLAIR study): multicentre case–control study. Intensiv. Care Med. 2016, 42, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, A.; Fanelli, V.; Pham, T.; Ranieri, V.M. European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Trials Group and the “Strategy of Ultra-Protective lung ventilation with Extracorporeal CO2 Removal for New-Onset moderate to severe ARDS” (SUPERNOVA) investigators Feasibility and safety of extracorporeal CO2 removal to enhance protective ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome: The SUPERNOVA study. Intensiv. Care Med. 2019, 45, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain-Syed, F.; Birk, H.-W.; Wilhelm, J.; Ronco, C.; Ranieri, V.M.; Karle, B.; Kuhnert, S.; Tello, K.; Hecker, M.; Morty, R.E.; et al. Extracorporeal Carbon Dioxide Removal Using a Renal Replacement Therapy Platform to Enhance Lung-Protective Ventilation in Hypercapnic Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019-Associated Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 598379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consales, G.; Zamidei, L.; Turani, F.; Atzeni, D.; Isoni, P.; Boscolo, G.; Saggioro, D.; Resta, M.V.; Ronco, C. Combined Renal-Pulmonary Extracorporeal Support with Low Blood Flow Techniques: A Retrospective Observational Study (CICERO Study). Blood Purif. 2021, 51, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, N.K.; Mani, R.K.; Herth, F.J.; Schmidt, W.; Teschler, H.; Bonin, F.; Becker, H.; Randerath, W.J.; Stieglitz, S.; Hagmeyer, L.; et al. A Novel Extracorporeal CO 2 Removal System. Chest 2013, 143, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, E.; Crotti, S.; Zacchetti, L.; Bottino, N.; Berto, V.; Russo, R.; Chierichetti, M.; Protti, A.; Gattinoni, L. Effect of extracorporeal CO2 removal on respiratory rate in spontaneously breathing patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Crit. Care 2013, 17, P128–P128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, J.-L.; Piquilloud, L.; Vimpere, D.; Aissaoui, N.; Guerot, E.; Augy, J.L.; Pierrot, M.; Hourton, D.; Arnoux, A.; Richard, C.; et al. Physiological effects of adding ECCO2R to invasive mechanical ventilation for COPD exacerbations. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamee, J.J.; Gillies, M.A.; Barrett, N.A.; Perkins, G.D.; Tunnicliffe, W.; Young, D.; Bentley, A.; Harrison, D.A.; Brodie, D.; Boyle, A.J.; et al. Effect of Lower Tidal Volume Ventilation Facilitated by Extracorporeal Carbon Dioxide Removal vs Standard Care Ventilation on 90-Day Mortality in Patients With Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure. JAMA 2021, 326, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, T.; Pisani, L.; Cavalli, I.; Vega, M.L.; Maietti, E.; Filippini, C.; Nava, S.; Ranieri, V.M. Extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal for treatment of exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ORION): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagiannidis, C.; Hesselmann, F.; Fan, E. Physiological and Technical Considerations of Extracorporeal CO2 Removal. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannidis, C.; Strassmann, S.; Brodie, D.; Ritter, P.; Larsson, A.; Borchardt, R.; Windisch, W. Impact of membrane lung surface area and blood flow on extracorporeal CO2 removal during severe respiratory acidosis. Intensiv. Care Med. Exp. 2017, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, H.R.; Mirsaeidi, M.; Socias, S.; Sprenker, C.; Caldeira, C.; Camporesi, E.M.; Mangar, D. Plasma Free Hemoglobin Is an Independent Predictor of Mortality among Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0124034–e0124034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehle, K.; Philipp, A.; Zeman, F.; Lunz, D.; Lubnow, M.; Wendel, H.-P.; Göbölös, L.; Schmid, C.; Müller, T. Technical-Induced Hemolysis in Patients with Respiratory Failure Supported with Veno-Venous ECMO – Prevalence and Risk Factors. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0143527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimbene, A.; Neelamegham, S.; Frazier, O.H.; Moake, J.L.; Dong, J.-F. Acquired von Willebrand syndrome associated with left ventricular assist device. Blood 2016, 127, 3133–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufour, N.; Radjou, A.; Thuong, M. Hemolysis and Plasma Free Hemoglobin During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support: From Clinical Implications to Laboratory Details. Asaio J. 2020, 66, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadee, C.; Raat, N.J.; Kanias, T.; Tejero, J.; Lee, J.S.; Kelley, E.E.; Zhao, X.; Liu, C.; Reynolds, H.; Azarov, I.; et al. Nitric Oxide Scavenging by Red Blood Cell Microparticles and Cell-Free Hemoglobin as a Mechanism for the Red Cell Storage Lesion. Circulation 2011, 124, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

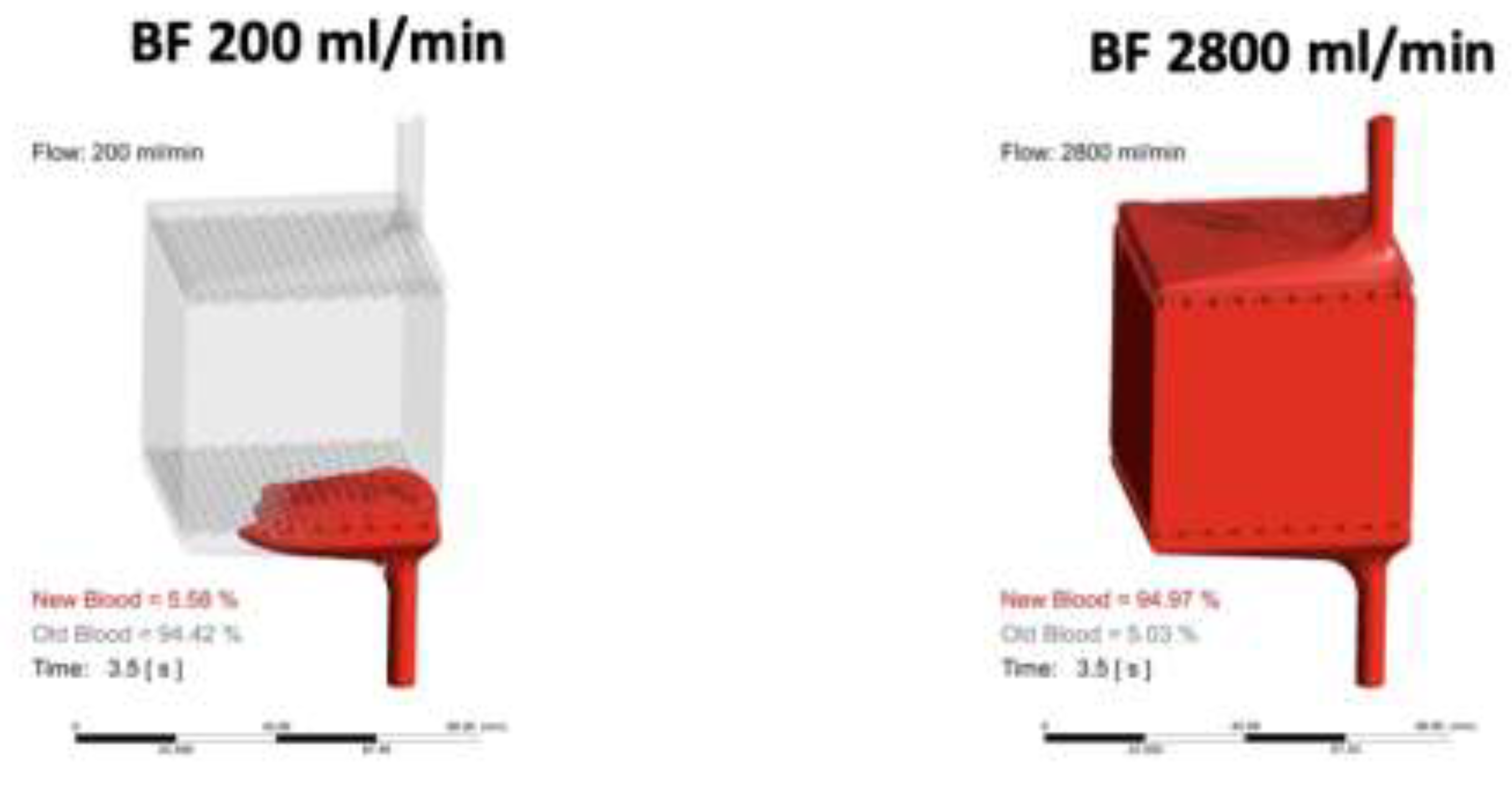

- Gross-Hardt, S.; Hesselmann, F.; Arens, J.; Steinseifer, U.; Vercaemst, L.; Windisch, W.; Brodie, D.; Karagiannidis, C. Low-flow assessment of current ECMO/ECCO2R rotary blood pumps and the potential effect on hemocompatibility. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlois, M.R.; Delanghe, J.R. Biological and clinical significance of haptoglobin polymorphism in humans. Clin. Chem. 1996, 42, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rother, R.P.; Bell, L.; Hillmen, P.; Gladwin, M.T. The Clinical Sequelae of Intravascular Hemolysis and Extracellular Plasma Hemoglobin. JAMA 2005, 293, 1653–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minneci, P.C.; Deans, K.J.; Zhi, H.; Yuen, P.S.; Star, R.A.; Banks, S.M.; Schechter, A.N.; Natanson, C.; Gladwin, M.T.; Solomon, S.B. Hemolysis-associated endothelial dysfunction mediated by accelerated NO inactivation by decompartmentalized oxyhemoglobin. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 3409–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaer, D.J.; Buehler, P.W.; Alayash, A.I.; Belcher, J.D.; Vercellotti, G.M. Hemolysis and free hemoglobin revisited: exploring hemoglobin and hemin scavengers as a novel class of therapeutic proteins. Blood 2013, 121, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da, Q.; Teruya, M.; Guchhait, P.; Teruya, J.; Olson, J.S.; Cruz, M.A. Free hemoglobin increases von Willebrand factor–mediated platelet adhesion in vitro: implications for circulatory devices. Blood 2015, 126, 2338–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L'Acqua, C.; Hod, E. New perspectives on the thrombotic complications of haemolysis. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 168, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurzinger, L.; Blasberg, P.; Schmid-Schönbein, H. Towards a concept of thrombosis in accelerated flow: Rheology, fluid dynamics, and biochemistry. Biorheology 1985, 22, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C. Anticoagulation and Coagulation Management for ECMO. Semin. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesthesia 2009, 13, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malfertheiner, M.V.; Pimenta, L.P.; von Bahr, V.; E Millar, J.; Obonyo, N.G.; Suen, J.; Pellegrino, V.; Fraser, J.F. Acquired von Willebrand syndrome in respiratory extracorporeal life support: a systematic review of the literature. . 2017, 19, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbhenn, J.; Neuffer, N.; Zieger, B.; Schmutz, A. Is Extracorporeal CO2 Removal Really “Safe” and “Less” Invasive? Observation of Blood Injury and Coagulation Impairment during ECCO2R. Asaio J. 2017, 63, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, N.K.; Mani, R.K.; Herth, F.J.; Schmidt, W.; Teschler, H.; Bonin, F.; Becker, H.; Randerath, W.J.; Stieglitz, S.; Hagmeyer, L.; et al. A Novel Extracorporeal CO 2 Removal System. Chest 2013, 143, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sorbo, L.; Fan, E.; Nava, S.; Ranieri, V.M. ECCO2R in COPD exacerbation only for the right patients and with the right strategy. Intensiv. Care Med. 2016, 42, 1830–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braune, S.; Sieweke, A.; Brettner, F.; Staudinger, T.; Joannidis, M.; Verbrugge, S.; Frings, D.; Nierhaus, A.; Wegscheider, K.; Kluge, S. The feasibility and safety of extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal to avoid intubation in patients with COPD unresponsive to noninvasive ventilation for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure (ECLAIR study): multicentre case–control study. Intensiv. Care Med. 2016, 42, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bein, T.; Weber-Carstens, S.; Goldmann, A.; Müller, T.; Staudinger, T.; Brederlau, J.; Muellenbach, R.; Dembinski, R.; Graf, B.M.; Wewalka, M.; et al. Lower tidal volume strategy (≈3 ml/kg) combined with extracorporeal CO2 removal versus ‘conventional’ protective ventilation (6 ml/kg) in severe ARDS. Intensiv. Care Med. 2013, 39, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanelli, V.; Ranieri, M.V.; Mancebo, J.; Moerer, O.; Quintel, M.; Morley, S.; Moran, I.; Parrilla, F.; Costamagna, A.; Gaudiosi, M.; et al. Feasibility and safety of low-flow extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal to facilitate ultra-protective ventilation in patients with moderate acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funakubo, A.; Taga, I.; McGillicuddy, J.W.; Fukui, Y.; Hirschl, R.B.; Bartlett, R.H. Flow vectorial analysis in an artificial implantable lung. . 2003, 49, 383–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meyer, A.D.; Rishmawi, A.R.; Kamucheka, R.; Lafleur, C.; Batchinsky, A.I.; Mackman, N.; Cap, A.P. Effect of blood flow on platelets, leukocytes, and extracellular vesicles in thrombosis of simulated neonatal extracorporeal circulation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 18, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okorie, U.M.; Denney, W.S.; Chatterjee, M.S.; Neeves, K.B.; Diamond, S.L. Determination of surface tissue factor thresholds that trigger coagulation at venous and arterial shear rates: amplification of 100 fM circulating tissue factor requires flow. Blood 2008, 111, 3507–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.H.H.; Ki, K.K.; Zhang, M.; Asnicar, C.; Cho, H.J.; Ainola, C.; Bouquet, M.; Heinsar, S.; Pauls, J.P.; Bassi, G.L.; et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation-Induced Hemolysis: An In Vitro Study to Appraise Causative Factors. Membranes 2021, 11, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhro, A.; Huisjes, R.; Verhagen, L.P.; Mañú-Pereira, M.d.M.; Llaudet-Planas, E.; Petkova-Kirova, P.; Wang, J.; Eichler, H.; Bogdanova, A.; van Wijk, R.; et al. Red Cell Properties after Different Modes of Blood Transportation. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.S.; Weerwind, P.W.; Bekers, O.; Wouters, E.M.; Maessen, J.G. Carbon dioxide dialysis in a swine model utilizing systemic and regional anticoagulation. Intensiv. Care Med. Exp. 2016, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, V.J.J.; Miller, L.; Lynch, J.E.; Anderson, M.J.; Zwischenberger, J.B. Percutaneous Venovenous CO2 Removal With Regional Anticoagulation in an Ovine Model. Asaio J. 2006, 52, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimont, P.; Habran, S.; Desaive, T.; Blaffart, F.; Lagny, M.; Amand, T.; Dauby, P.; Oury, C.; Lancellotti, P.; Hego, A.; et al. Extracorporeal CO2 removal and regional citrate anticoagulation in an experimental model of hypercapnic acidosis. Artif. Organs 2019, 43, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaravilli, V.; Di Girolamo, L.; Scotti, E.; Busana, M.; Biancolilli, O.; Leonardi, P.; Carlin, A.; Lonati, C.; Panigada, M.; Pesenti, A.; et al. Effects of sodium citrate, citric acid and lactic acid on human blood coagulation. Perfusion 2018, 33, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, J.; Qian, J.; You, H.; Gu, Y.; Hao, C.; Jiao, Z.; Ding, F. Citrate Pharmacokinetics in Critically Ill Patients with Acute Kidney Injury. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e65992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, A.; Patroniti, N.; Isgrò, S.; Albertini, M.; Costanzi, M.; Pirrone, F.; Scaravilli, V.; Vergnano, B.; Pesenti, A. Blood acidification enhances carbon dioxide removal of membrane lung: an experimental study. Intensiv. Care Med. 2009, 35, 1484–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, A.; Mangili, P.; Giani, M.; Redaelli, S.; Scaravilli, V.; Castagna, L.; Sosio, S.; Pirrone, F.; Albertini, M.; Patroniti, N.; et al. Extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal through ventilation of acidified dialysate: An experimental study. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 2014, 33, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, A.; Giani, M.; Redaelli, S.; Mangili, P.; Scaravilli, V.; Ormas, V.; Costanzi, M.; Albertini, M.; Bellani, G.; Patroniti, N.; et al. Infusion of 2.5 meq/min of lactic acid minimally increases CO2 production compared to an isocaloric glucose infusion in healthy anesthetized, mechanically ventilated pigs. Crit. Care 2013, 17, R268–R268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaravilli, V.; Kreyer, S.; Belenkiy, S.; Linden, K.; Zanella, A.; Li, Y.; Dubick, M.A.; Cancio, L.C.; Pesenti, A.; Batchinsky, A.I. Extracorporeal Carbon Dioxide Removal Enhanced by Lactic Acid Infusion in Spontaneously Breathing Conscious Sheep. Anesthesiology 2016, 124, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bels, D.; Pierrakos, C.; Spapen, H.D.; Honore, P.M. A double catheter approach for extracorporeal CO2removal integrated within a continuous renal replacement circuit. J. Transl. Intern. Med. 2018, 6, 157–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moossavi, S.; Vachharajani, T.J.; Jordan, J.; Russell, G.B.; Kaufman, T.; Moossavi, S. Retrospective Analysis of Catheter Recirculation in Prevalent Dialysis Patients. Semin. Dial. 2008, 21, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

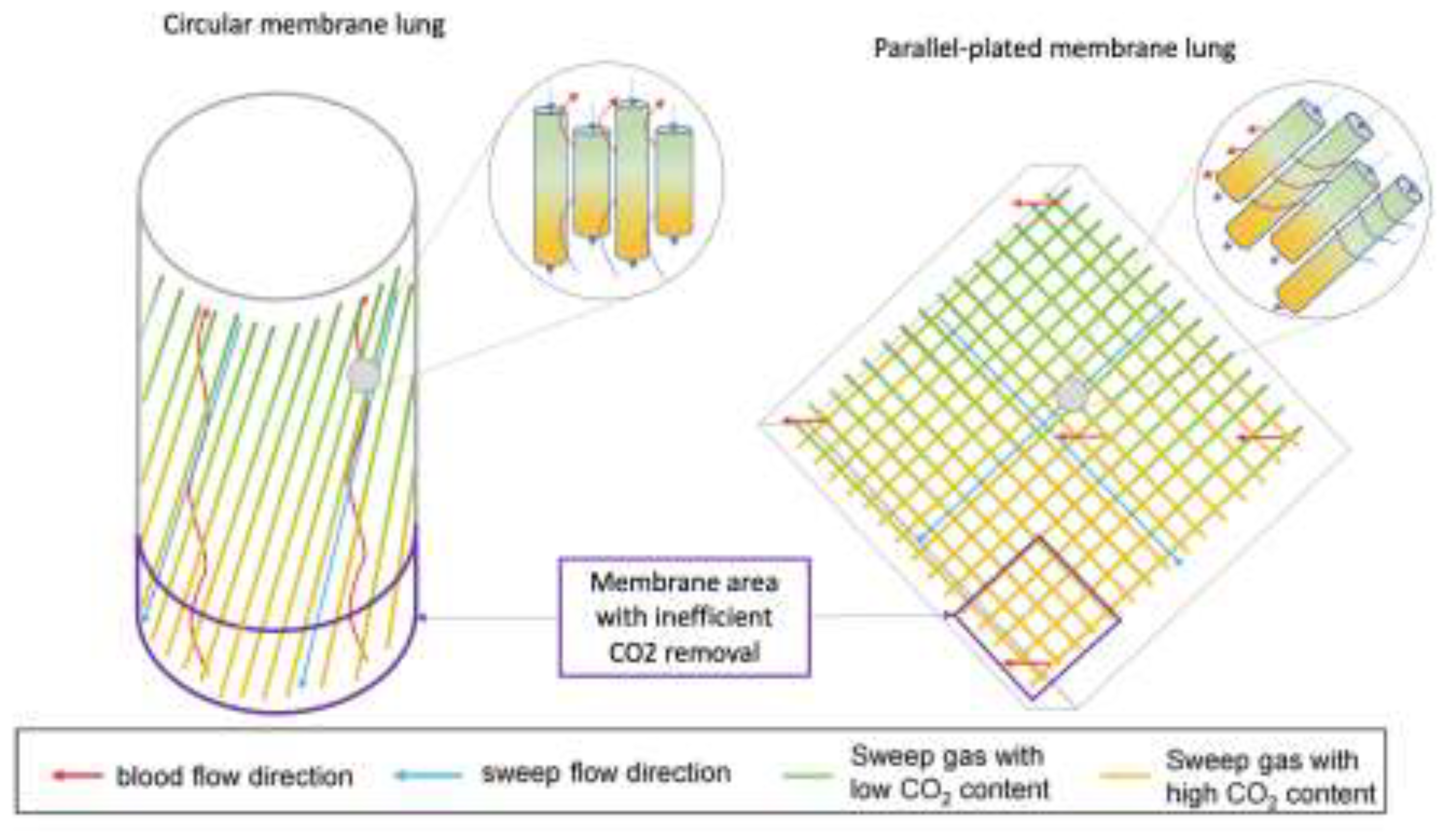

- Schwärzel, L.S.; Jungmann, A.M.; Schmoll, N.; Caspari, S.; Seiler, F.; Muellenbach, R.M.; Bewarder, M.; Dinh, Q.T.; Bals, R.; Lepper, P.M.; et al. Comparison of Circular and Parallel-Plated Membrane Lungs for Extracorporeal Carbon Dioxide Elimination. Membranes 2021, 11, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allardet-Servent, J.; Castanier, M.; Signouret, T.; Soundaravelou, R.; Lepidi, A.; Seghboyan, J.-M. Safety and Efficacy of Combined Extracorporeal CO2 Removal and Renal Replacement Therapy in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Acute Kidney Injury. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 2570–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Jaber, S.; Zogheib, E.; Godet, T.; Capellier, G.; Combes, A. Feasibility and safety of low-flow extracorporeal CO2 removal managed with a renal replacement platform to enhance lung-protective ventilation of patients with mild-to-moderate ARDS. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nentwich, J.; Wichmann, D.; Kluge, S.; Lindau, S.; Mutlak, H.; John, S. Low-flow CO2 removal in combination with renal replacement therapy effectively reduces ventilation requirements in hypercapnic patients: a pilot study. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2019, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanella, A.; Castagna, L.; Salerno, D.; Scaravilli, V.; Deab, S.A.E.A.E.S.; Magni, F.; Giani, M.; Mazzola, S.; Albertini, M.; Patroniti, N.; et al. Respiratory Electrodialysis. A Novel, Highly Efficient Extracorporeal CO2 Removal Technique. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffries, R.G.; Lund, L.; Frankowski, B.; Federspiel, W.J. An extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal (ECCO2R) device operating at hemodialysis blood flow rates. Intensiv. Care Med. Exp. 2017, 5, 41–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, R.; Esposito, I.; Imperatore, F.; Liguori, G.; Gritti, F.; Cafora, C.; Marsilia, P.F.; De Cristofaro, M. Decapneization as supportive therapy for the treatment of status asthmaticus: a case report. J. Med Case Rep. 2021, 15, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospach, I.; Goldstein, J.; Harenski, K.; Laffey, J.G.; Pouchoulin, D.; Raible, M.; Votteler, S.; Storr, M. In vitro characterization of PrismaLung+: a novel ECCO2R device. Intensiv. Care Med. Exp. 2020, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CO2 Reset – Eurosets. https://www.eurosets.com/en/product/co2-reset/. Accessed , 2024. 25 November.

- Huber, W.; Lorenz, G.; Heilmaier, M.; Böttcher, K.; Sahm, P.; Middelhoff, M.; Ritzer, B.; Schulz, D.; Bekka, E.; Hesse, F.; et al. Extracorporeal multiorgan support including CO2-removal with the ADVanced Organ Support (ADVOS) system for COVID-19: A case report. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2021, 44, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allescher, J.; Rasch, S.; Wiessner, J.R.; de Garibay, A.P.R.; Huberle, C.; Hesse, F.; Schulz, D.; Schmid, R.M.; Huber, W.; Lahmer, T. Extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal with the Advanced Organ Support system in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Artif. Organs 2021, 45, 1522–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, G.J.; Killer, H.M.; Reeves, R.; Sosnowski, A.W.; Firmin, R.K. Early Experience with a Polymethyl Pentene Oxygenator for Adult Extracorporeal Life Support. Asaio J. 2002, 48, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshbin, E.; Roberts, N.; Harvey, C.; Machin, D.; Killer, H.; Peek, G.J.; Sosnowski, A.W.; Firmin, R.K. Poly-Methyl Pentene Oxygenators Have Improved Gas Exchange Capability and Reduced Transfusion Requirements in Adult Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Asaio J. 2005, 51, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toomasian, J.M.; Schreiner, R.J.; Meyer, D.E.; Schmidt, M.E.; Hagan, S.E.; Griffith, G.W.; Bartlett, R.H.; Cook, K.E. A Polymethylpentene Fiber Gas Exchanger for Long-Term Extracorporeal Life Support. Asaio J. 2005, 51, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylor, J. Membrane oxygenators: current developments in design and application. J. Biomed. Eng. 1988, 10, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supplement for the 10th EuroELSO Congress 4–6 May 2022 London/UK. Perfusion 2022, 37, 3–111. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ontaneda, A.; Annich, G.M. Novel Surfaces in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Circuits. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, J.D.; Arazawa, D.T.; Ye, S.-H.; Shankarraman, V.; Wagner, W.R.; Federspiel, W.J. Carbonic anhydrase immobilized on hollow fiber membranes using glutaraldehyde activated chitosan for artificial lung applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2013, 24, 2611–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arazawa, D.; Kimmel, J.; Finn, M.; Federspiel, W. Acidic sweep gas with carbonic anhydrase coated hollow fiber membranes synergistically accelerates CO2 removal from blood. Acta Biomater. 2015, 25, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straube, T.L.; Farling, S.; A Deshusses, M.; Klitzman, B.; Cheifetz, I.M.; Vesel, T.P. Intravascular Gas Exchange: Physiology, Literature Review, and Current Efforts. Respir. Care 2022, 67, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.R.; Jones, N.L.; Reed, J.W. Calculation of whole blood CO2 content. J. Appl. Physiol. 1988, 65, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, J.; Tatam, R.P. Optical gas sensing: A review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2013, 24, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Barrett, N.; Hart, N.; Camporota, L. In vivo carbon dioxide clearance of a low-flow extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal circuit in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Perfusion 2020, 35, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Barrett, N.; Hart, N.; Camporota, L. In-vitro performance of a low flow extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal circuit. Perfusion 2019, 35, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappadona, F.; Costa, E.; Mallia, L.; Sangregorio, F.; Nescis, L.; Zanetti, V.; Russo, E.; Bianzina, S.; Viazzi, F.; Esposito, P. Extracorporeal Carbon Dioxide Removal: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Applications; Focus on Combined Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.M.; Halfwerk, F.; Wiegmann, B.; Neidlin, M.; Arens, J. Trends, Advantages and Disadvantages in Combined Extracorporeal Lung and Kidney Support From a Technical Point of View. Front. Med Technol. 2022, 4, 909990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allescher, J.; Rasch, S.; Wiessner, J.R.; de Garibay, A.P.R.; Huberle, C.; Hesse, F.; Schulz, D.; Schmid, R.M.; Huber, W.; Lahmer, T. Extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal with the Advanced Organ Support system in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Artif. Organs 2021, 45, 1522–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cove, M.E.; MacLaren, G.; Federspiel, W.J.; Kellum, J.A. Bench to bedside review: Extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal, past present and future. Crit. Care 2012, 16, 232–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taccone, F.S.; Malfertheiner, M.V.; Ferrari, F.; Di Nardo, M.; Swol, J.; Broman, L.M.; Vercaemst, L.; Barrett, N.; Pappalardo, F.; Belohlavek, J.; et al. Extracorporeal CO2 removal in critically ill patients: a systematic review. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017, 83, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivona, L.; Battistin, M.; Carlesso, E.; Langer, T.; Valsecchi, C.; Colombo, S.M.; Todaro, S.; Gatti, S.; Florio, G.; Pesenti, A.; et al. Alkaline Liquid Ventilation of the Membrane Lung for Extracorporeal Carbon Dioxide Removal (ECCO2R): In Vitro Study. Membranes 2021, 11, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, F.A.; Santonocito, C.; Lamasb, T.; Costa, P.; Vieira, S.M.; Ferreira, H.A.; Sanfilippo, F. Is artificial intelligence prepared for the 24-h shifts in the ICU? Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2024, 101431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Haimowitz, B.J.; Tharwani, K.; Rojas-Peña, A.; Bartlett, R.H.; Potkay, J.A. A Wearable Extracorporeal CO2 Removal System with a Closed-Loop Feedback. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).