Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of the Study and Control Groups

2.2. Determination of Serum Concentrations of Selected Markers of Inflammation

2.3. MRE in the Study Group

2.4. Statistical Analysis

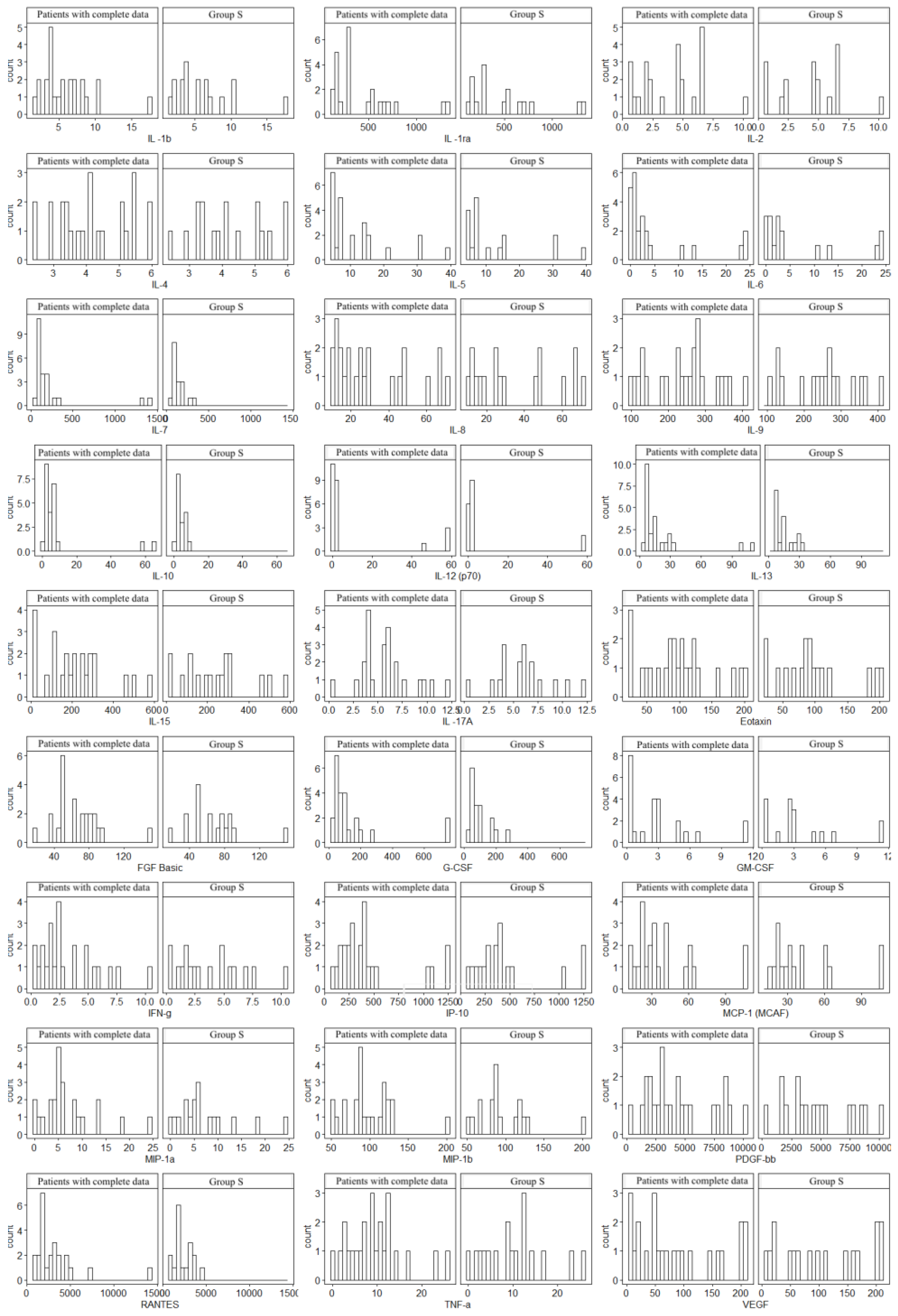

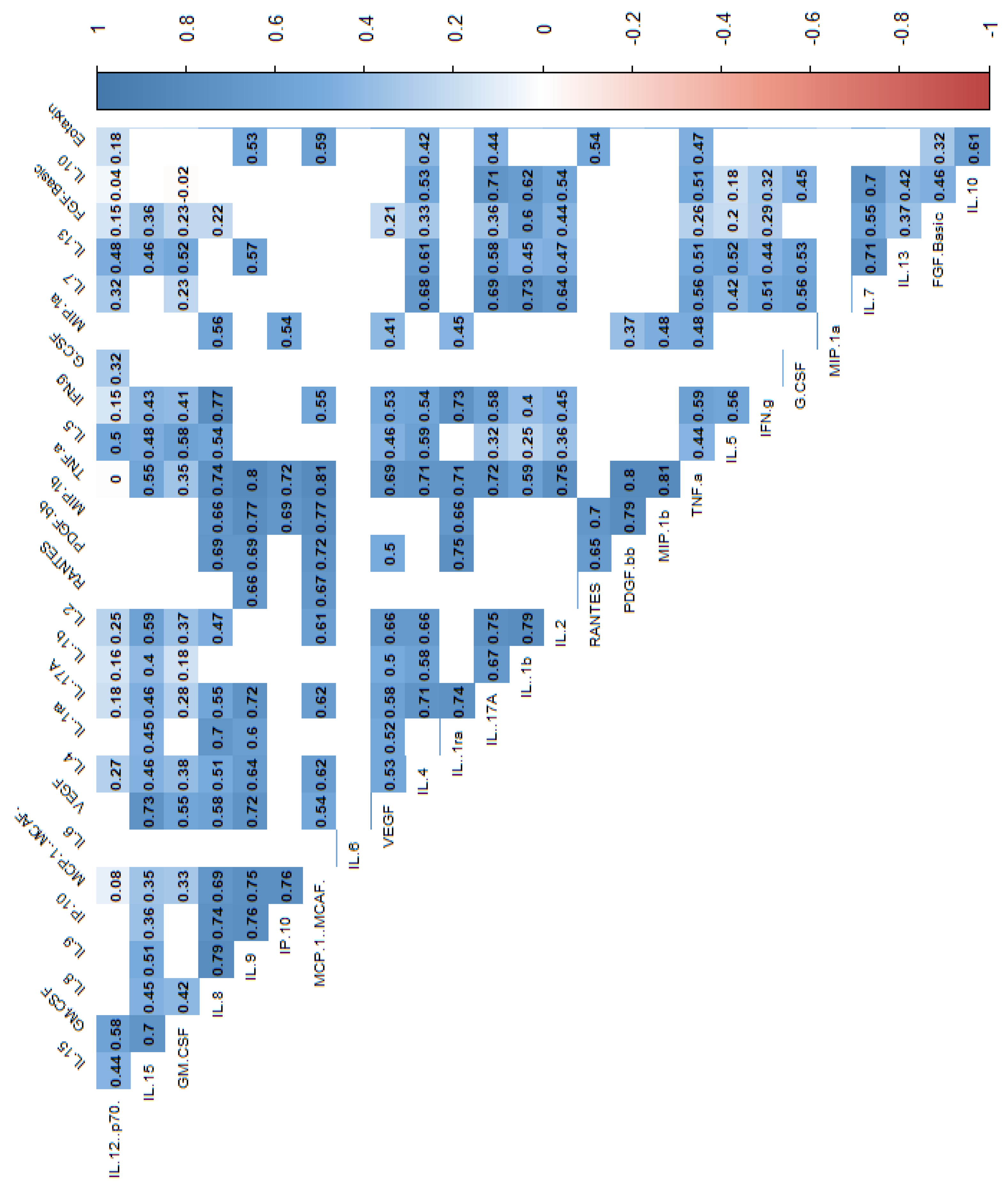

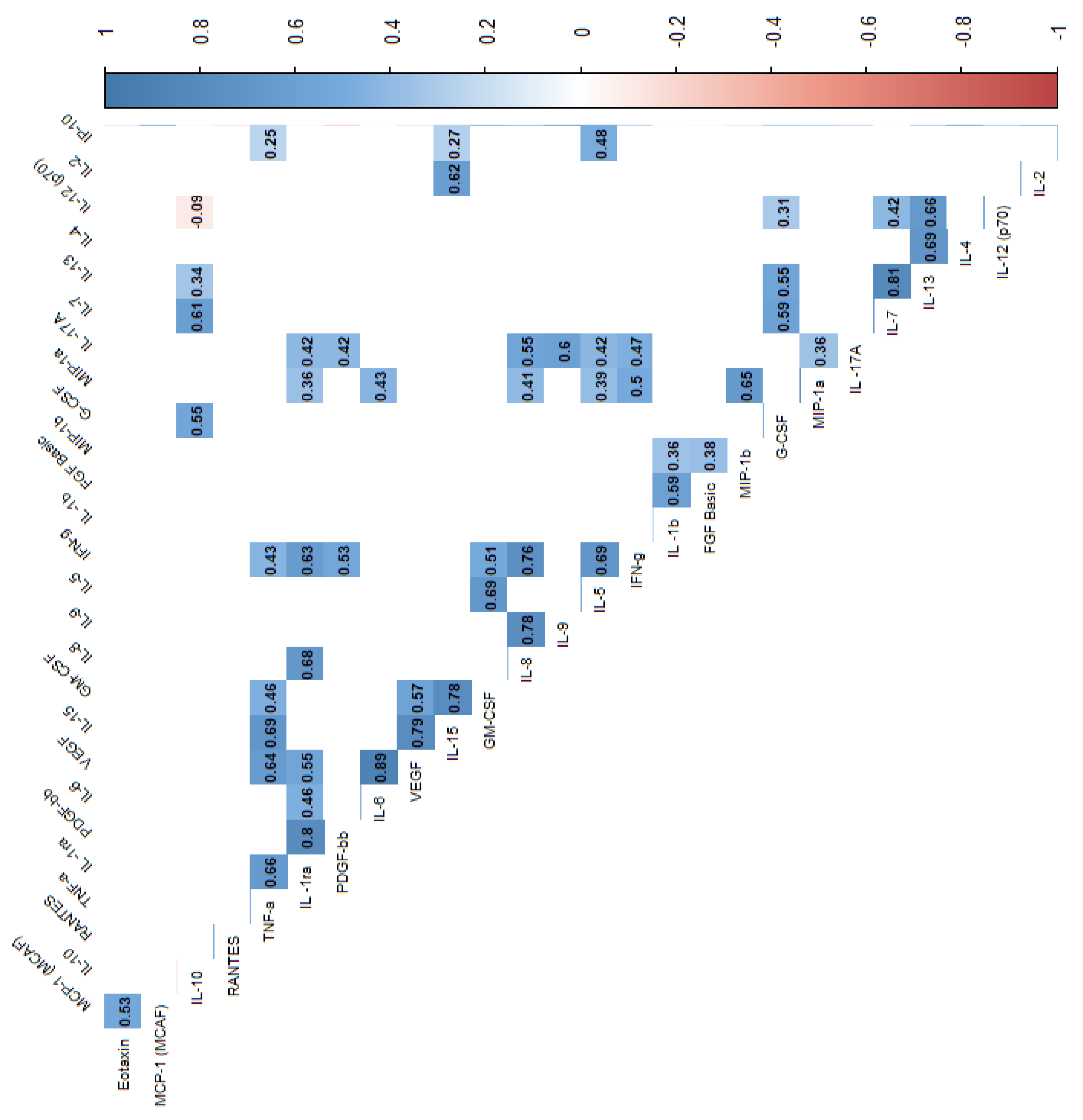

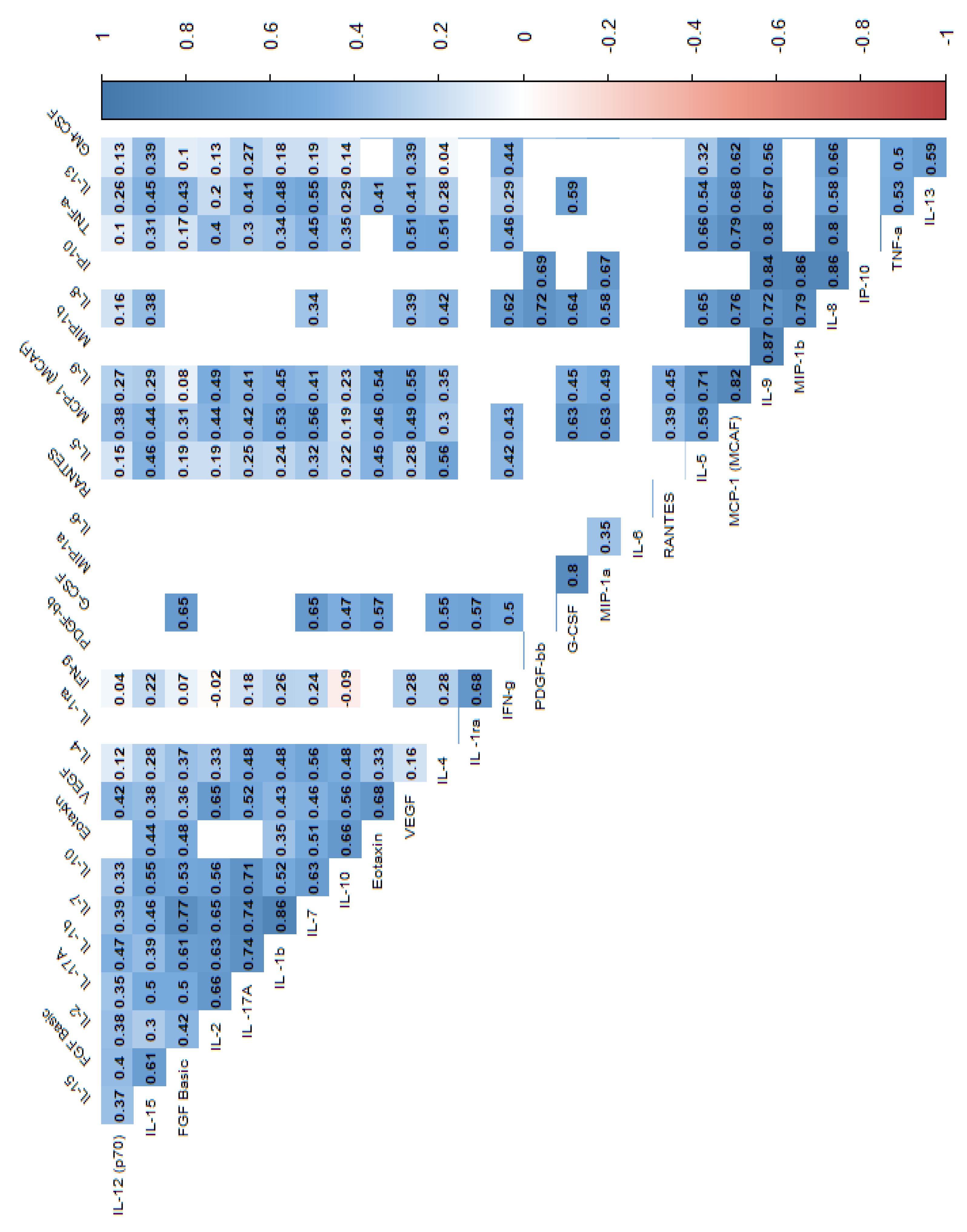

3. Results

- -

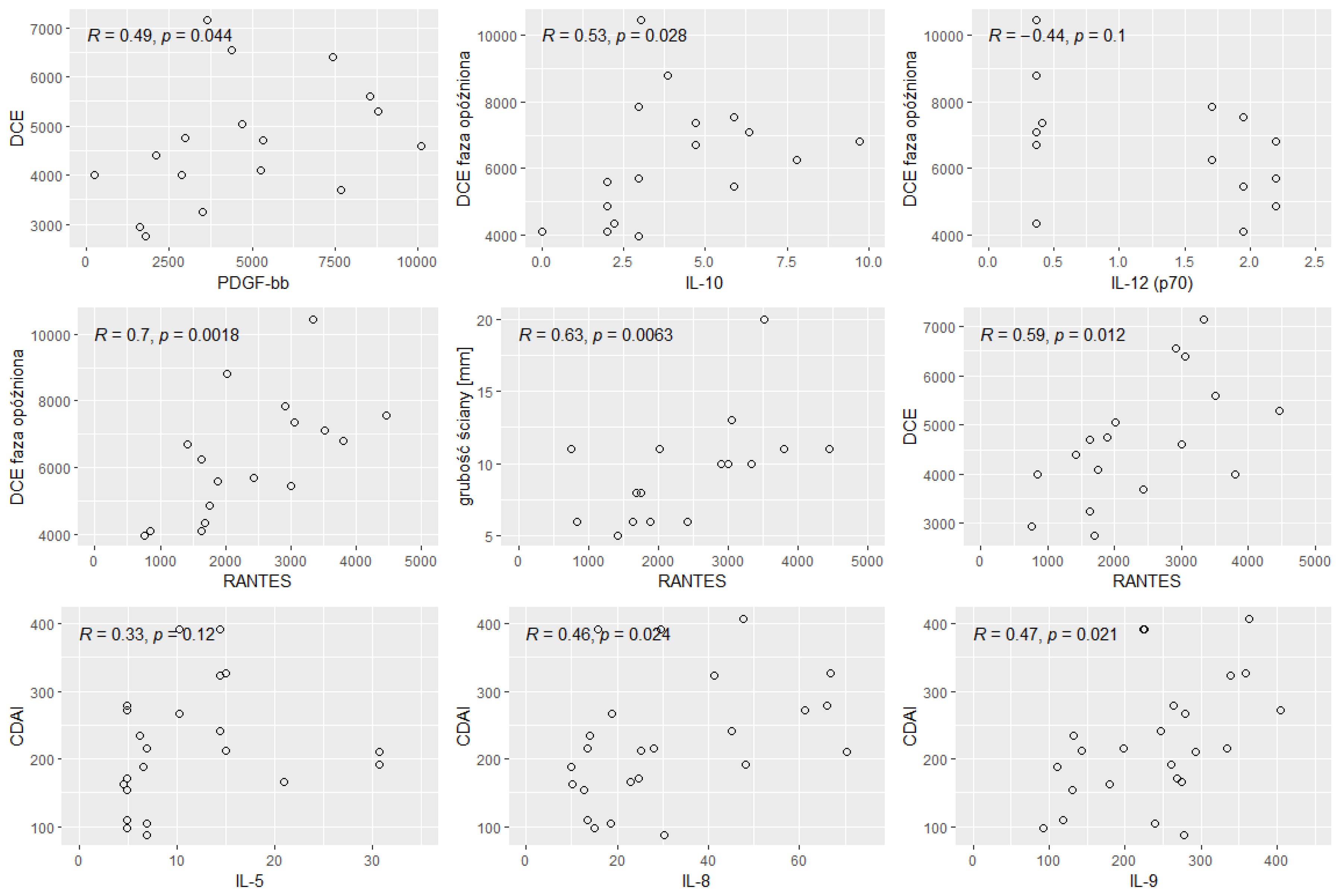

- enhancement of the intestinal wall assessed using DCE;

- -

- enhancement of the intestinal wall assessed using delayed-phase of DCE;

- -

- thickness of the intestinal wall on T2 images;

- -

- diffusion restriction assessed using apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps (mm/s).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sairenji T, Collins K, Evans D. An Update on Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 2017, 44, 673–692.

- Alatab S, et al. GBD 2017 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborators, The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet Gastroenterology& hepatology. 2020, 5, 17–30.

- Odze, R. A contemporary and critical appraisal of 'indeterminate colitis'. Mod Pathol 2015, 28, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgart, D. Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis—From Epidemiology and Immunobiology to a Rational Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approach. Springer, New York, 2012.

- Baumgart D, Sandborn W. Crohn’s disease. Lancet volume 2012, 380, 1590–1605.

- Eder, P. Przydatność biomarkerów w ocenie aktywności nieswoistych chorób zapalnych jelit - wskazówki praktyczne. Gastroenterologia kliniczna 2018, 10, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Olivera PA, Silverberg MS. Biomarkers That Predict Crohn’s Disease Outcomes. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2023, 7, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, AR. Treat to target in Crohn’s disease: A practical guide for clinicians. World J Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, An J. Cytokines, inflammation and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2007, 45, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova TV, Miteva L, Stanilov N, Spassova Z, Stanilova SA. Interleukin-6 compared to the other Th17/Treg related cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 1912–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein G, McGovern D. Using Markers in IBD to predict disease and treatmenr outcomes: rationale and a review of current status. The Americal Journal of Gastroenterology Supplements. 2016, 3, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennike T, Birkelund S, Stensballe A, Andersen V. Biomarkers in inflammatory bowel diseases: current status and proteomics identification strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 3231–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voskuil, MD. Predicting (side) effects for patients with inflam- matory bowel disease: The Promise of pharmacogenetics. World J Gastroeneterol 2019, 25, 2539–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moy M, Sauk J, Gee M "The Role of MR Enterography in Assessing Crohn’s Disease Activity and Treatment Response". Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2016, 13, 8168695.

- Kennedy NA, Jones G-R, Plevris N, et al. Association between level of fecal calprotectin and progression of Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2019, 17, 2269–2276. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico F, Bonovas S, Danese S, et al. Review article: faecal calprotectin and histologic remission in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020, 51, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røseth AG, Schmidt PN, Fagerhol MK. Correlation between faecal excretion of indium-111-labelled granulocytes and calprotectin, a granulocyte marker protein, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999, 34, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, E. Fecal calprotectin: towards a standardized use for inflammatory bowel disease management in routine practice. J Crohns Colitis. 2015, 9, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan Q, Zhang J. Recent Advances: The Imbalance of Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 4810258. 160. Friedrich M, Pohin M, Powrie F. Cytokine Networks in the Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Immunity 2019, 50, 992–1006.

- Cornish J, Wirthgen E, Däbritz J. Biomarkers predictive of response to thiopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Caviglia G, Rosso C, Stalla F, et al. On-Treatment Decrease of Serum Interleukin- 6 as a Predictor of Clinical Response to Biologic Therapy in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J Clin Med. 2020, 9, 800. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich M, Pohin M, Powrie F. Cytokine Networks in the Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Immunity. 2019, 50, 992–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombel JF, D'haens G, Lee WJ, Petersson J, Panaccione R. Outcomes and Strategies to Support a Treat-to-target Approach in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. J Crohns Colitis. 2020, 14, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nikolaus S, Waetzig GH, Butzin S, et al. Evaluation of interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor components sIL-6R and sgp130 as markers of inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018, 33, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caviglia G, Rosso C, Stalla F, et al. On-Treatment Decrease of Serum Interleukin- 6 as a Predictor of Clinical Response to Biologic Therapy in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J Clin Med. 2020, 9, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgonje A, von Martels, Gabriëls R, et al. A combined set of four serum inflammatory biomarkers reliably predicts endoscopic disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Med. 2019, 6, 251.

- Danese S, Vermeire S, Hellstern P, et al Randomised trial and open-label extension study of an anti-interleukin-6 antibody in Crohn’s disease (ANDANTE I and II). Gut 2019, 68, 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Marlow G, van Gent D, Ferguson L. Why interleukin-10 supplementation does not work in Crohn’s disease patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 3931–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari N, Abdulla J, Zayyani N, Brahmi U, Taha S, Satir AA. Comparison of RANTES expression in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: an aid in the differential diagnosis? J Clin Pathol. 2006, 59, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzystek-Korpacka M, Neubauer K, Matusiewicz M, Platelet-derived growth factor-BB reflects clinical, inflammatory and angiogenic disease activity and oxidative stress in inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical Biochemistry 2009, 42, 1602–1609. [CrossRef]

- Słowińska-Solnica K, Pawlica-Gosiewska D, Gawlik K, Owczarek D, Cibor D, Pocztar H, Mach T, Solnica B. Serum Inflammatory markers in the diagnosis and assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. Archives of Medical Science 2021, 17, 252.

- Neubauer K, Matusiewicz M, Bednarz-Misa I, Gorska S, Gamian A, Krzystek- Korpacka M. Diagnostic potential of systemic eosinophil-associated cytokines and growth factors in IBD. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018, 2018, 7265812. [Google Scholar]

- Scaioli E, Cardamone C, Scagliarini M, Zagari RM, Bazzoli F, Belluzzi A. Can fecal calprotectin better stratify Crohn’s disease activity index? Ann Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Casini-Raggi V, Kam L, Chong YJ, Fiocchi C, Pizarro TT, Cominelli F. Mucosal imbalance of IL-1 and IL-1 receptor antagonist in inflammatory bowel disease. A novel mechanism of chronic intestinal inflammation. J Immunol. 1995, 154, 2434–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogler, G. Singh A, Kavanaugh A., Rubin T.D. Extraintestinal manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Concepts, Treatment and Implications for Disease Treatment. Review in basic and clinical gastroenterology and hepatology 2021, 161, 1118–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein J, Cheifetz A. Crohn Disease: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2017, 92, 1088–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder P, et al. Association of serum VEGF with clinical response to anti-TNFα therapy for Crohn’s disease. Cytokine 2015, 76, 288–293.

- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee. Shergill A, Lightdale J, Bruining D, Acosta R, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi K, Decker G, Early D, Evans J, Fanelli R, Fisher D, Fonkalsrud L, Foley K, Hwang J, Jue T, Khashab M, Muthusamy V, Pasha S, Saltzman J, Sharaf R, Cash B, DeWitt J. The role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015, 81, 1101–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Jess T, Gamborg M, Matzen P et al. Increased risk of intestinal cancer in Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 100, 2724–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller D, Windsor A, Cohen R et al. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: review of the evidence. Tech Coloproctol 2019, 23, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmine, Stolfi; et al. Role of TGF-Beta and Smad7 in Gut Inflammation, Fibrosis and Cancer. Biomolecules. 2021, 11, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton J, Platnich J, Muruve D, Jijon H, Buret A, Beck P. Interleukin-8 in gastrointestinal inflammation and malignancy: induction and clinical consequences. International Journal of Interferon, Cytokine and Mediator Research 2016, 8, 13–34. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | N | min | max | median | q1 | q3 | mean | SD | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24 | 22 | 78 | 43.5 | 31.5 | 57.8 | 45 | 15.8 | 3.23 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 24 | 13.5 | 32 | 21.8 | 19.5 | 24.1 | 22.1 | 4.27 | 0.871 |

| Height (m) | 24 | 1.57 | 1.94 | 1.7 | 1.63 | 1.76 | 1.7 | 0.099 | 0.02 |

|

Body weight (kg/m²) |

24 | 35 | 107 | 62 | 56.8 | 71.8 | 66 | 16.3 | 3.32 |

| CDAI | 24 | 88 | 408 | 214 | 165 | 274 | 226 | 92.5 | 18.9 |

| WBC | 24 | 3.65 | 25.1 | 7.04 | 4.96 | 9.66 | 8.06 | 5.02 | 1.02 |

| Hematocrit | 24 | 25.7 | 47.4 | 36 | 30.5 | 40.5 | 35.6 | 6.12 | 1.25 |

| ESR | 18 | 5 | 71 | 16 | 11.2 | 27.2 | 21.5 | 17.1 | 4.04 |

| CRP | 24 | 1 | 195 | 22.7 | 7.48 | 76.6 | 48.7 | 53.7 | 11 |

| Variable | n | min | max | median | q1 | q3 | mean | SD | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calprotectin (μg/g) | 24 | 1.57 | 1162 | 299 | 65.9 | 878 | 442 | 418 | 85.4 |

| pANCA | Negative | 17 | 70.80% |

| Positive | 6 | 20.80% | |

| No data | 2 | 8.33% | |

| cANCA | Negative | 22 | 91.70% |

| Positive | 0 | 0.00% | |

| No data | 2 | 8.33% |

| Variable | n | min | max | median | q1 | q3 | mean | SD | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 23 | 50 | 85 | 64 | 59.5 | 71.5 | 65.4 | 9.98 | 2.08 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23 | 20.1 | 44.1 | 24.3 | 23.4 | 27.6 | 26 | 4.85 | 1.01 |

| Height (m) | 23 | 1.52 | 1.83 | 1.67 | 1.62 | 1.72 | 1.67 | 0.077 | 0.016 |

| Body weight (kg) | 23 | 50 | 120 | 71 | 63.5 | 79 | 72.3 | 14.2 | 2.96 |

| Hematocrit | 23 | 29.9 | 45.8 | 41.8 | 40.1 | 43.7 | 41.4 | 3.48 | 0.726 |

| WBC | 23 | 3.56 | 10.8 | 7.32 | 5.42 | 8.3 | 6.94 | 1.84 | 0.383 |

| Variable | Study group (n=24) | Control group (n=23) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Q1 | Q3 | median | Q1 | Q3 | ||

| Age (years) | 43.50 | 31.00 | 58.50 | 64.00 | 59.00 | 72.00 | 0.00 |

| Height (m) | 1.70 | 1.63 | 1.77 | 1.67. | 1.61 | 1.72 | 0.42 |

| Body weight (kg) | 62.00 | 56.50 | 72.50 | 71.00 | 63.00 | 79.00 | 0.08 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.85 | 19.42 | 24.20 | 24.30 | 23.26 | 27.89 | 0.00 |

| WBC | 7.04 | 4.84 | 9.67 | 7.32 | 5.38 | 8.36 | 0.99 |

| Hematocrit | 36.05 | 30.35 | 40.50 | 41.80 | 39.70 | 43.70 | 0.00 |

| Variable | Group S | Group C | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| median | Q1 | Q3 | median | Q1 | Q3 | ||

| IL-1β | 5.19 | 3.84 | 7.55 | 2.18 | 1.06 | 3.84 | 0.00 |

| IL -1RA | 284.59 | 180.45 | 583.97 | 123.75 | 36.21 | 162.93 | 0.00 |

| IL-2 | 4.52 | 1.96 | 6.19 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.68 | 0.00 |

| IL-4 | 4.12 | 3.28 | 5.16 | 2.92 | 2.44 | 3.35 | 0.00 |

| IL-5 | 6.86 | 4.92 | 14.70 | 5.61 | 4.98 | 6.86 | 0.26 |

| IL-6 | 1.48 | 0.82 | 3.75 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| IL-7 | 124.25 | 92.72 | 181.64 | 72.30 | 46.62 | 151.49 | 0.01 |

| IL-8 | 25.00 | 14.53 | 46.35 | 2.82 | 0.07 | 20.46 | 0.00 |

| IL-9 | 254.19 | 161.49 | 286.77 | 109.76 | 63.56 | 147.18 | 0.00 |

| IL-10 | 4.28 | 2.96 | 6.34 | 1.01 | 0.02 | 4.42 | 0.00 |

| IL-12 (p70) | 1.71 | 0.36 | 2.20 | 1.71 | 1.71 | 1.95 | 0.52 |

| IL-13 | 11.47 | 7.97 | 23.99 | 8.40 | 4.60 | 10.89 | 0.03 |

| IL-15 | 198.06 | 110.02 | 283.01 | 123.78 | 110.02 | 130.65 | 0.08 |

| IL-17A | 5.54 | 3.96 | 6.90 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 2.92 | 0.00 |

| Variable | Group S | Group C | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Q1 | Q3 | median | Q1 | Q3 | ||

| Eotaxin | 95.94 | 61.92 | 123.45 | 53.49 | 19.03 | 101.17 | 0.02 |

| FGF-Basic | 65.08 | 50.87 | 81.77 | 51.64 | 34.32 | 76.54 | 0.29 |

| G-CSF | 75.52 | 50.31 | 140.06 | 76.56 | 55.85 | 124.26 | 0.95 |

| GM-CSF | 2.49 | 0.50 | 4.01 | 1.87 | 1.66 | 1.97 | 0.45 |

| IFN-γ | 2.35 | 1.51 | 5.00 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 1.75 | 0.01 |

| IP-10 | 362.55 | 226.93 | 449.42 | 49.38 | 26.27 | 278.70 | 0.00 |

| MCP-1 (MCAF) | 30.98 | 22.12 | 49.05 | 1.67 | 1.51 | 11.25 | 0.00 |

| MIP-1α | 5.35 | 4.08 | 8.78 | 4.68 | 2.75 | 6.82 | 0.24 |

| MIP-1β | 90.65 | 81.13 | 120.84 | 33.82 | 17.09 | 48.03 | 0.00 |

| PDGF-BB | 3580.42 | 2190.98 | 6371.61 | 292.35 | 65.40 | 1226.16 | 0.00 |

| RANTES | 2615.87 | 1662.23 | 3657.45 | 855.64 | 515.59 | 1780.38 | 0.00 |

| TNF α | 8.88 | 4.82 | 12.09 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.00 |

| VEGF | 64.97 | 28.26 | 152.46 | 17.53 | 15.34 | 21.92 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).