1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of unknown etiology characterized by erosions and ulcers in the colon. In recent years, various molecular targeted agents, including cytokine-neutralizing antibodies, have been developed for the treatment of UC. Identifying biomarkers that can predict the efficacy of each drug in advance could aid the selection of a therapeutic agent.

To date, numerous predictive biomarkers have been validated for the therapeutic efficacy of several agents used in the treatment of UC. Nishida et al. reported the use-fulness of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a predictor of loss of response to infliximab and clinical relapse after tacrolimus induction in UC [

1,

2]. Endo et al. found that the NLR and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) could predict the response to systemic corticosteroid therapy in UC [

3]. The C-reactive protein (CRP)-to-lymphocyte ratio (CLR) has also been reported to be a useful predictor of colectomy after infliximab treatment in acute severe UC [

4]. These biomarkers are inexpensive and can be measured by routine blood tests, and can therefore be easily applied in clinical practice.

Ustekinumab (UST) is a monoclonal antibody against p40, a subunit common to interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23. UST suppresses chronic inflammation by inhibiting IL-12, which induces T helper 1 cell response, and IL-23, which is involved in T helper 17 cell differentiation [

5]. Although the UNIFI trial demonstrated the efficacy of UST induction and maintenance therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe UC [

6], there are still many cases of primary non-response and loss of response to UST treatment. Hence, it would be very useful in clinical practice to predict the long-term outcome of UST treatment prior to treatment initiation. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have validated biomarkers for predicting the efficacy of UST treatment in patients with UC.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify biomarkers that can predict the long-term outcomes of UST treatment in patients with UC at an early stage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

We retrospectively reviewed the records of patients with moderately to severely active UC treated with UST between March 2020 and January 2023 at our hospital. The diagnosis of UC was based on the clinical presentation, endoscopic and histological findings, and the exclusion of alternative diagnoses. Analyzed data included demographic and clinical characteristics, medical history, and laboratory and endoscopic findings.

Baseline (pretreatment) laboratory testing, including markers of systemic inflammation, was performed within one week before UST treatment initiation. Patients received a weight-based, one-time induction dose of UST of 260 mg (≤ 55kg), 390 mg (55–85 kg), or 520 mg (>85 kg) as an intravenous infusion, followed by 90-mg subcutaneous maintenance injections every 8 or 12 weeks. Response evaluation was performed at weeks 4 and 8, and every 8 weeks thereafter. All patients were followed up by physical examination and blood testing.

2.2. Study Endpoint

The primary outcome measure of this study was clinical remission at week 48.

2.3. Definitions

The partial Mayo (pMayo) score was used to assess clinical disease activity, excluding the endoscopic subscore. The Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) was used to assess endoscopic activity. Clinical remission was defined as a pMayo score ≤2 with each subscore ≤1. Clinical response was defined as a decrease in the pMayo score of ≥2 points relative to the baseline value, and a rectal bleeding score ≤1 or a decrease in this score of ≥1 relative to the baseline value. Patients who discontinued UST treatment or received any other treatment after UST initiation were defined as non-responders. The remaining patients were divided in remission and non-remission groups based on whether they achieved clinical remission at week 48 of UST treatment.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as medians and interquartile ranges, and compared between the groups using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, and compared using the Fisher exact test. The cumulative UST treatment discontinuation rates were plotted using Kaplan–Meier plots, and differences between groups were evaluated using the log-rank test. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were employed to identify factors associated with clinical remission at week 48 of UST treatment. To evaluate the predictive performance of the identified factors, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted to calculate the area under the ROC curve. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP®®, Version 15.2.1, SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, 1989-2021, USA.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Patient Characteristics

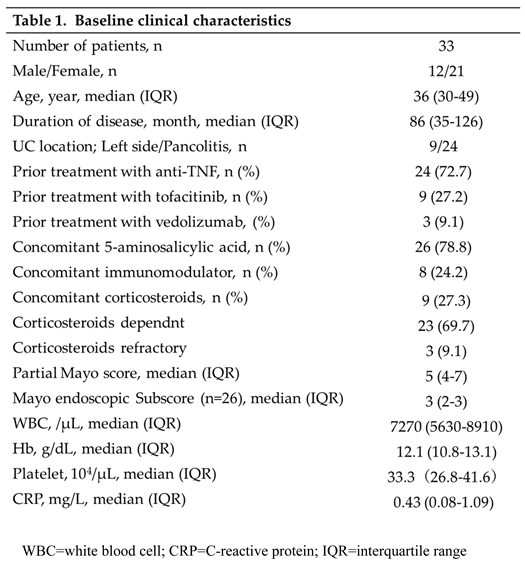

A total of 33 patients (12 men and 21 women) with a median age of 36 years were included in the study. All patients received UST subcutaneously every 8 weeks as maintenance therapy. The median disease duration was 86 (35–-126) months. Regarding previous treatment, 24 (72.7%) and 9 (27.2%) patients had received anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antibody products and tofacitinib, respectively. At the start of UST treatment, 9 (27.3%) patients were taking corticosteroids and 8 (24.2%) were taking immunomodulators. The median CRP value, pMayo score, and MES were 0.43 (0.08–1.12) mg/dL, 5 (4–7), and 3 (2–3; n=26). The baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

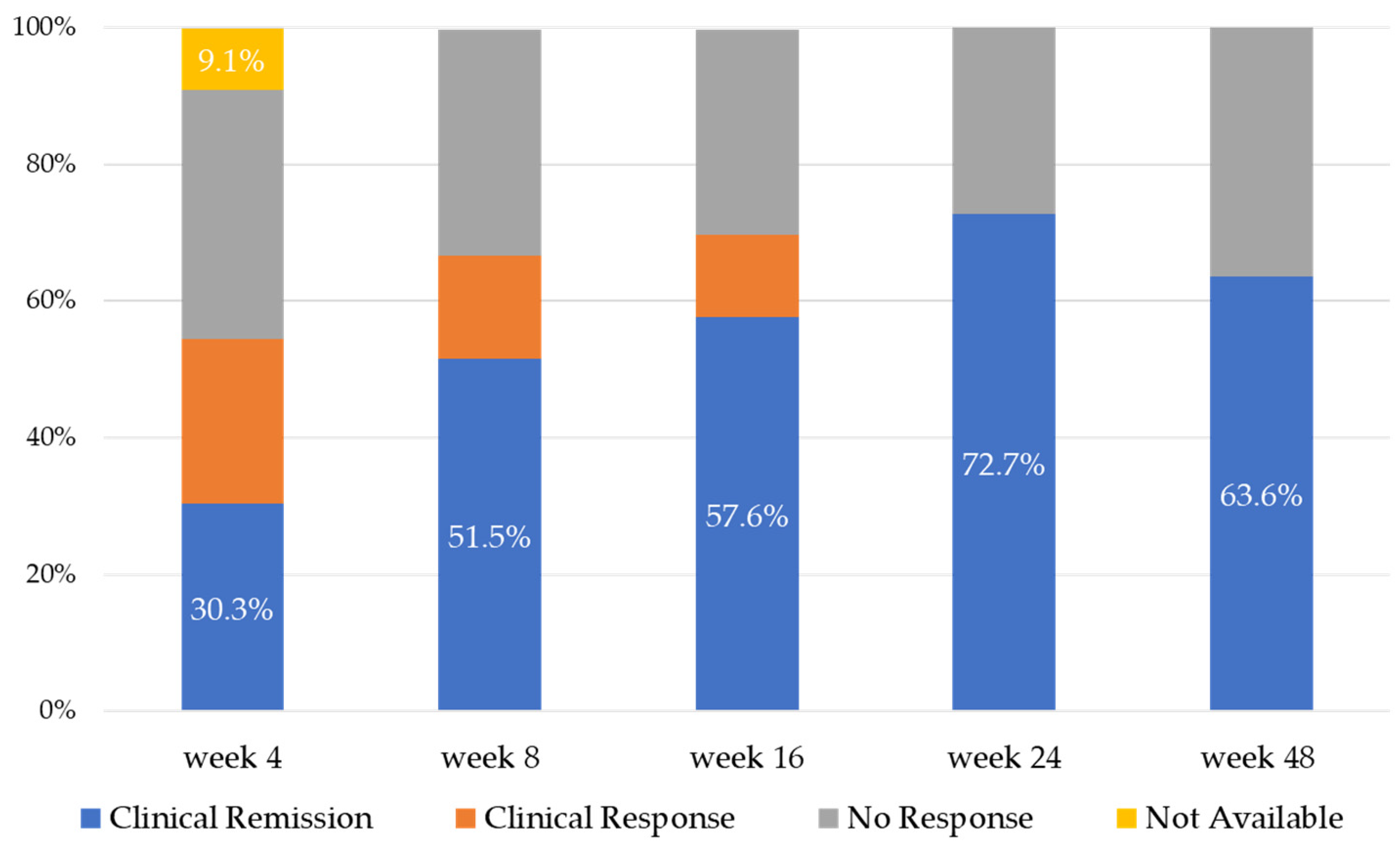

3.2. UST Treatment Efficacy Up to Week 48

Figure 1 demonstrates the efficacy of UST treatment up to 48 weeks. Clinical remission rates increased gradually from week 4 to week 24 (30.3%, 51.5%, 57.6%, and 72.7% at weeks 4, 8, 16, and 24, respectively), with a median clinical remission rate at week 48 of 63.6%. The clinical response rates were 54.5%, 66.7%, 69.7%, and 72.7% at weeks 4, 8, 16, and 24, respectively, and 63.6% at week 48. The UST treatment continuation rates at weeks 24 and 48 were 84.8% and 75.6%, respectively.

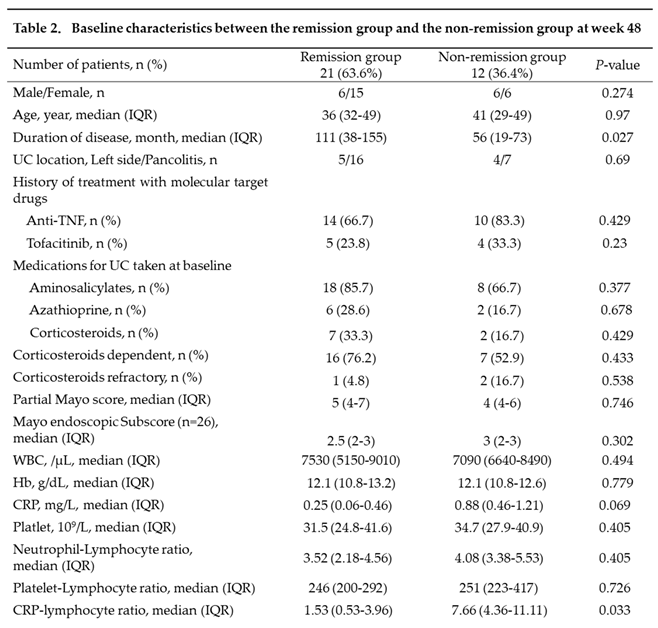

3.3. Comparison between the Remission and Non-Remission Groups at Week 48

Baseline clinical characteristics were compared between 21 patients in the remission group and 12 patients in the non-remission group (Table 2). Compared with those in the remission group, patients in the non-remission group had significantly shorter disease duration (p=0.027) and significantly higher CLR values (p=0.033). Although CRP values also tended to be higher in the non-remission than in the remission group, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.069). The pMayo score and MES (n=26), as well as NLR and PLR values did not significantly differ between the two groups.

3.4. Predictors of Clinical Remission at Week 48

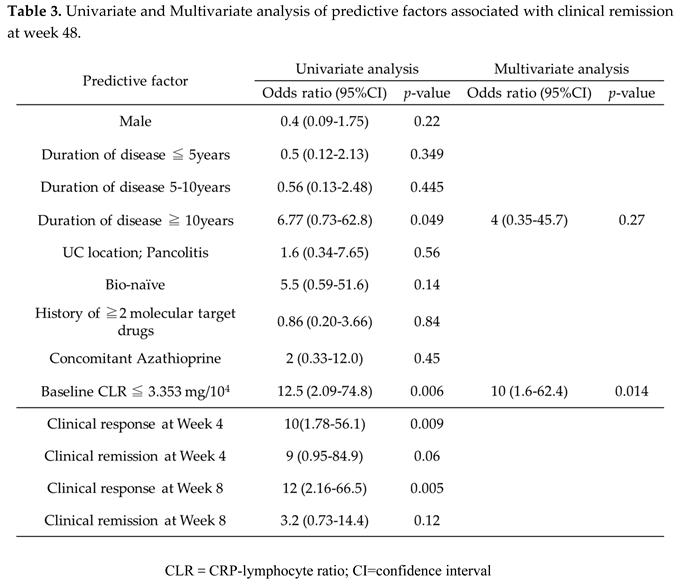

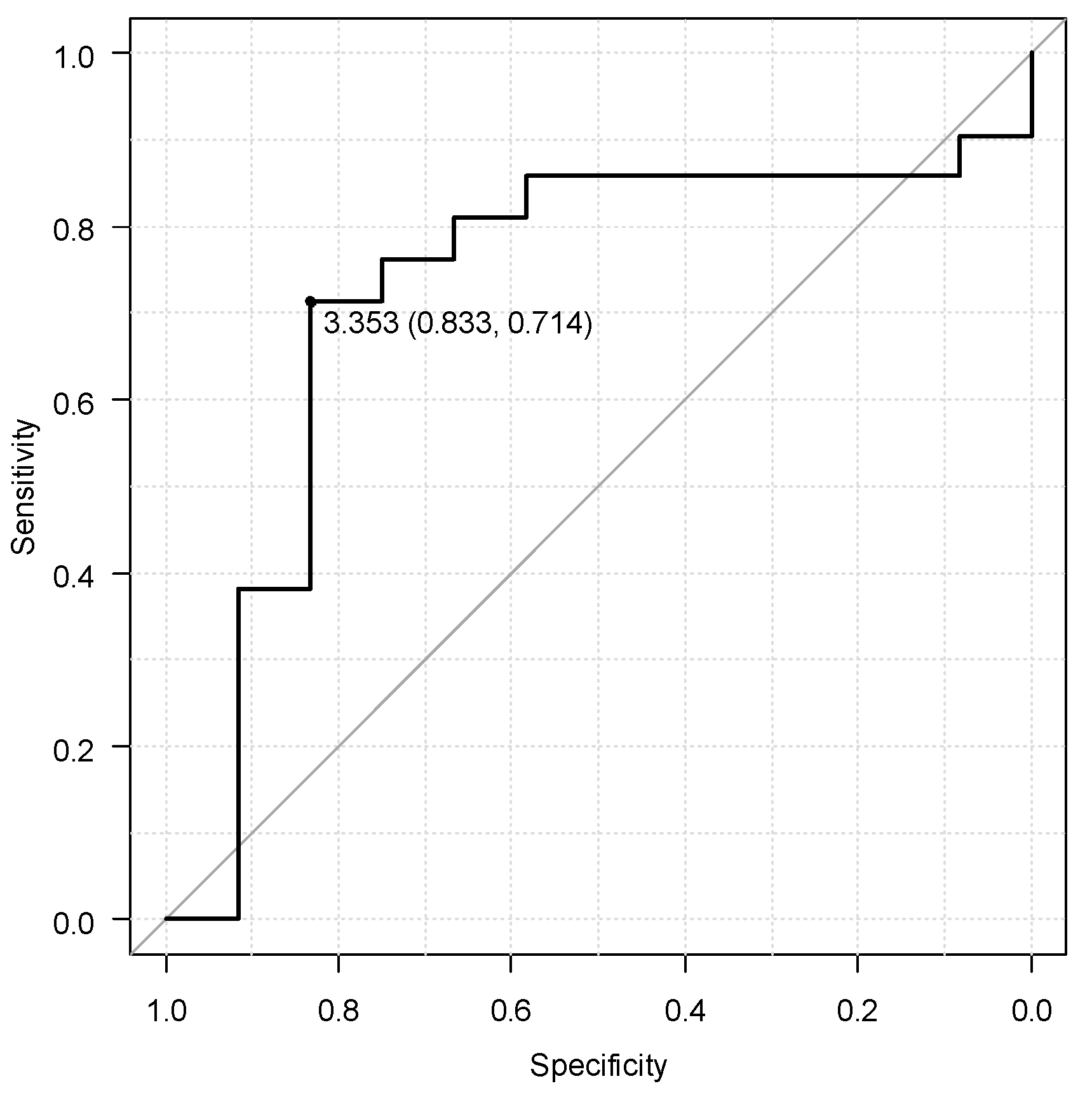

In the ROC curve analysis, the optimal threshold for the baseline CLR value associated with long-term efficacy of UST was 3.353, with an area under the curve for clinical remission at week 48 of 0.7, sensitivity of 71.4%, and specificity of 83.3% (

Figure 2).

In the univariable analysis, disease duration ≥10 years (odds ratio [OR]: 6.77, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.73–62.8, p=0.049) and baseline CLR value ≤3.353 (OR: 16, 95% CI: 2.59–98.8, p=0.003) were significantly associated with clinical remission at week 48. However, in the multivariable analysis, only baseline CLR value ≤3.353 was identified as an independent predictive factor (OR: 13.5, CI: 2.09–86.7, p=0.006).

When evaluating the UST treatment response in the early phase, the clinical response rate at week 4 (OR: 10, CI: 1.78–56.1, p=0.009) and that at week 8 (OR: 12, CI: 2.16–66.5, p=0.005) were significantly associated with clinical remission at week 48 (Table 3).

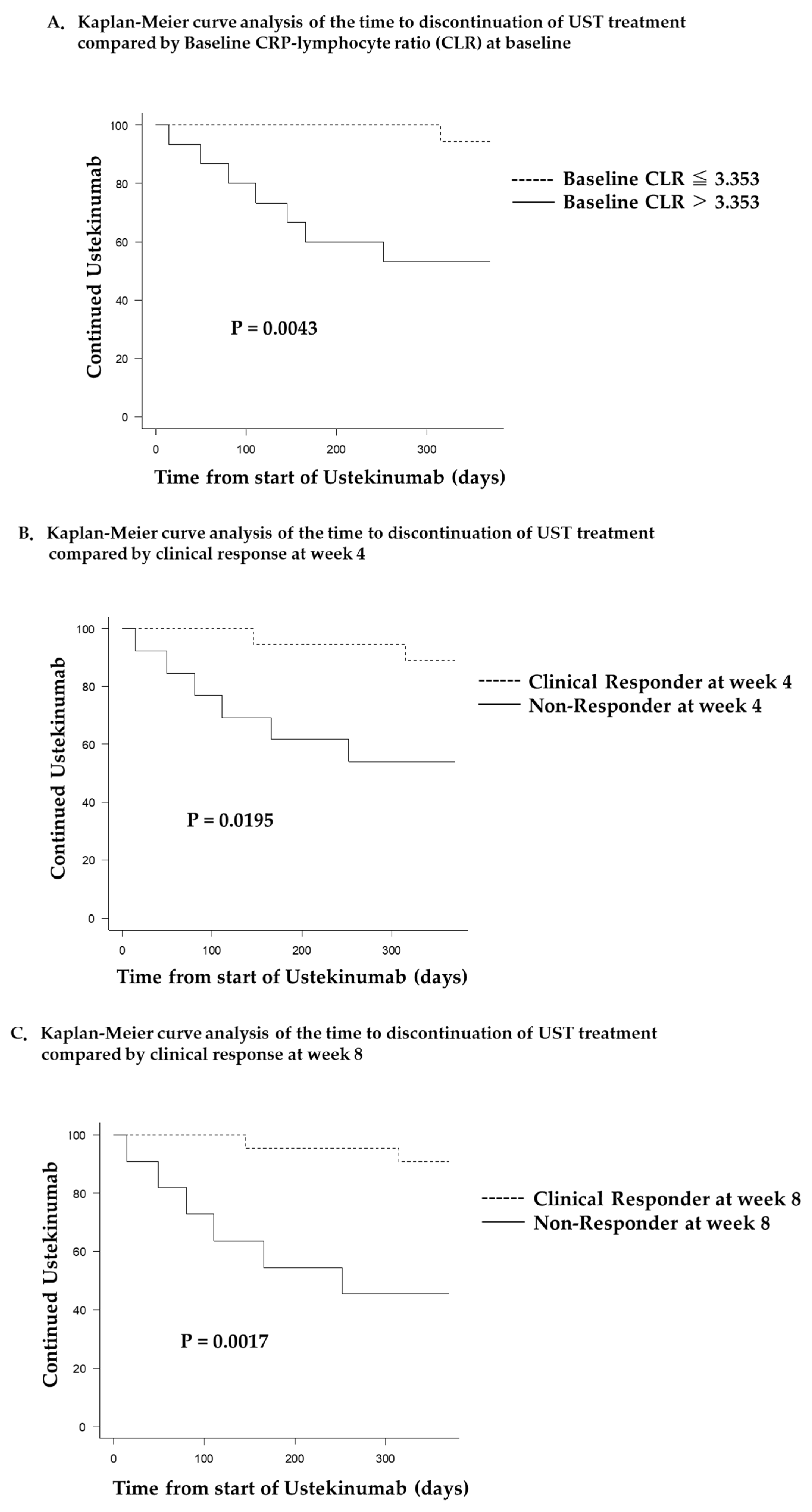

3.5. Kaplan–Meier Curve Analyses

Figure 3 depicts the survival analysis of the time to UST treatment discontinuation. Patients in the low CLR group (baseline CLR ≤3.353) showed significantly longer UST treatment duration than those in the high CLR group (baseline CLR >3.353) (p=0.0089,

Figure 3A). Furthermore, UST treatment duration was significantly longer in the clinical responder than in the non-responder group, both at week 4 (p=0.0195,

Figure 3B) and at week 8 (p=0.0017,

Figure 3C).

3.6. UST Treatment Safety

Adverse events occurred in two patients (one case of skin rash and one case of upper respiratory infection requiring hospitalization); however, neither adverse event required discontinuation of UST treatment. Among nonresponders, two patients underwent elective colectomy.

4. Discussion

In this study, the baseline CLR value was significantly associated with clinical re-mission at week 48 of UST treatment, suggesting that higher CLR values at baseline predicting lower efficacy of UST treatment can be one of the criteria for selecting therapeutic agents for UC. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report pretreatment biomarkers that can be used to predict long-term UST efficacy in patients with UC. Considering the variety of therapeutic agents that have been developed for refractory UC in recent years, predicting the efficacy of a therapeutic agent prior to treatment initiation using readily available parameters would be of great clinical significance.

In addition to the CLR,4 other biomarkers based on the peripheral blood lymphocyte count, such as the NLR and PLR, have been reported as predictive factors for treatment efficacy in patients with UC [

1,

2,

3,

7]. The lymphocyte count in the peripheral blood is decreased in active UC, which may be caused by various factors, such as infiltration of lymphocytes into the intestinal tissue, apoptosis due to autoimmune diseases, malnutrition, and leakage due to intestinal bleeding [

3]. CRP, an acute-phase protein produced by hepatocytes upon stimulation with IL-6, is the most well-studied inflammatory parameter in patients with IBD [

8,

9]. The CRP responses more modest in UC compared to that in Crohn’s disease, with more than 15% of patients with UC showing no CRP response [

10,

11]. Chaparro et al. reported that high baseline CRP values were negatively correlated with the short-term UST response [

12]. Similarly, in the current study, patients with lower long-term UST efficacy tended to have higher baseline CRP values. Although UC is a disease with a heterogeneous cytokine profile, the results suggest that UST, an anti-IL-12/23 antibody, is less effective in patients with high CRP values, who may also have high levels of IL-6. Based on these findings, the CLR, which is the ratio of CRP to the peripheral blood lymphocyte count, may be a novel biomarker that reflects the pathogenesis of UC and the mechanism of action of UST.

According to prior studies in patients with IBD, the short-term response to treatment with biologic agents, including anti-TNF antibody agents like infliximab, is predictive of the long-term efficacy [

13,

14]. For UST, the short-term treatment response at weeks 8–12 has been associated with the long-term outcomes in patients with Crohn’s disease [

15,

16]. In our study, the early response to UST treatment at weeks 4 and 8 was predictive of its long-term efficacy in patients with UC. Similar findings were obtained in the UNIFI study, which reported that clinical remission at week 8 of UST treatment was associated with clinical remission at maintenance week 44 [

17]. Thus, the results of the present study are consistent with previously reported findings. Notably, in our study, the clinical response at week 4 was significantly associated with the long-term efficacy of UST treatment. Predicting the subsequent efficacy early after the start of UST treatment is clinically meaningful because it allows for early decision-making regarding treatment continuation.

This study has limitations due to the retrospective single-center design, which limited the sample size and may have led to selection bias. Thus, further prospective studies with a large cohort should be performed to validate the predictive value of the CLR and early treatment response for UST efficacy in patients with UC.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that baseline CLR values are associated with the long-term outcomes of UST treatment in patients with UC. Therefore, this parameter should be considered when selecting a treatment agent for UC in clinical practice. In addition, early response to treatment was associated with clinical remission at week 48 of UST treatment, suggesting that a change in treatment may be considered if there is no improvement in clinical symptoms by week 8 of UST treatment.

Author Contributions

Ryoji Koshiba collected data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. Kazuki Kakimoto designed the study and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. Noboru Mizuta, Keijiro Numa, Naohiko Kinoshita, Kei Nakazawa, Yuki Hirata, Takako Miyazaki, Shiro Nakamura, Hiroki Nishikawa have contributed to data collection and have critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available because there is no appropriate site for uploading at present. The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Shiro Nakamura reports receiving speaking fees from AbbVie GK, EA Pharma Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K. Dr.

References

- Benson JM, Peritt D, Scallon BJ, et al. Discovery and mechanism of ustekinumab: a human monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-12 and interleukin-23 for treatment of immune-mediated disorders. MAbs 2011, 3, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sands, B.E.; Sandborn, W.J.; Panaccione, R.; O’brien, C.D.; Zhang, H.; Johanns, J.; Adedokun, O.J.; Li, K.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Van Assche, G.; et al. Ustekinumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. New Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1201–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, Y.; Hosomi, S.; Yamagami, H.; Yukawa, T.; Otani, K.; Nagami, Y.; Tanaka, F.; Taira, K.; Kamata, N.; Tanigawa, T.; et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio for Predicting Loss of Response to Infliximab in Ulcerative Colitis. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0169845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, Y.; Hosomi, S.; Yamagami, H.; Sugita, N.; Itani, S.; Yukawa, T.; Otani, K.; Nagami, Y.; Tanaka, F.; Taira, K.; et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts clinical relapse of ulcerative colitis after tacrolimus induction. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0213505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo K, Satoh T, Yoshino Y, et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Plate-let-to-Lymphocyte Ratios as Noninvasive Predictors of the Therapeutic Outcomes of Systemic Corticosteroid Therapy in Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2021, 6, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Con, D.; Andrew, B.; Nicolaides, S.; van Langenberg, D.R.; Vasudevan, A. Biomarker dynamics during infliximab salvage for acute severe ulcerative colitis: C-reactive protein (CRP)-lymphocyte ratio and CRP-albumin ratio are useful in predicting colectomy. Intest. Res. 2022, 20, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, N.; Asai, Y.; Miyazu, T.; Tamura, S.; Tani, S.; Yamade, M.; Iwaizumi, M.; Hamaya, Y.; Osawa, S.; Furuta, T.; et al. Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio is a short-term predictive marker of ulcerative colitis after induction of advanced therapy. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2022, 10, goac025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeire, S.; Van Assche, G.; Rutgeerts, P. Laboratory markers in IBD: useful, magic, or unnecessary toys? Gut 2006, 55, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavropoulou, E.; Mechie, N.-C.; Knoop, R.; Petzold, G.; Ellenrieder, V.; Kunsch, S.; Pilavakis, Y.; Amanzada, A. Association of serum interleukin-6 and soluble interleukin-2-receptor levels with disease activity status in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective observational study. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0233811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saverymuttu, S.H.; Hodgson, H.J.; Chadwick, V.S.; Pepys, M.B. Differing acute phase responses in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Gut 1986, 27, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosli, M.H.; Zou, G.; Garg, S.K.; Feagan, S.G.; MacDonald, J.K.; Chande, N.; Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G. C-Reactive Protein, Fecal Calprotectin, and Stool Lactoferrin for Detection of Endoscopic Activity in Symptomatic Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 802–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro, M.; Garre, A.; Iborra, M.; Sierra-Ausín, M.; Acosta, M.B.-D.; Fernández-Clotet, A.; de Castro, L.; Boscá-Watts, M.; Casanova, M.J.; López-García, A.; et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Ustekinumab in Ulcerative Colitis: Real-world Evidence from the ENEIDA Registry. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2021, 15, 1846–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombel, J.F.; Rutgeerts, P.; Reinisch, W.; Esser, D.; Wang, Y.; Lang, Y.; Marano, C.W.; Strauss, R.; Oddens, B.J.; Feagan, B.G.; et al. Early Mucosal Healing With Infliximab Is Associated With Improved Long-term Clinical Outcomes in Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taxonera, C.; Rodríguez, C.; Bertoletti, F.; Menchén, L.; Arribas, J.; Sierra, M.; Arias, L.; Martínez-Montiel, P.; Juan, A.; Iglesias, E.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Golimumab as First, Second or Third Anti-TNF Agent in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1394–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, T.; Maemoto, A.; Katsurada, T.; Motoya, S.; Ueno, N.; Fujiya, M.; Ashida, T.; Hirayama, D.; Nakase, H. Long-Term Clinical Effectiveness of Ustekinumab in Patients With Crohn’s Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Crohns Colitis 360 2020, 2, otaa061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorrami S, Ginard D, Marín-Jiménez I, et al. Ustekinumab for the Treatment of Refractory Crohn’s Disease: The Spanish Experience in a Large Multicentre Open-label Cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1662–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adedokun, O.J.; Xu, Z.; Marano, C.; O’brien, C.; Szapary, P.; Zhang, H.; Johanns, J.; Leong, R.W.; Hisamatsu, T.; Van Assche, G.; et al. Ustekinumab Pharmacokinetics and Exposure Response in a Phase 3 Randomized Trial of Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2244–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).