Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

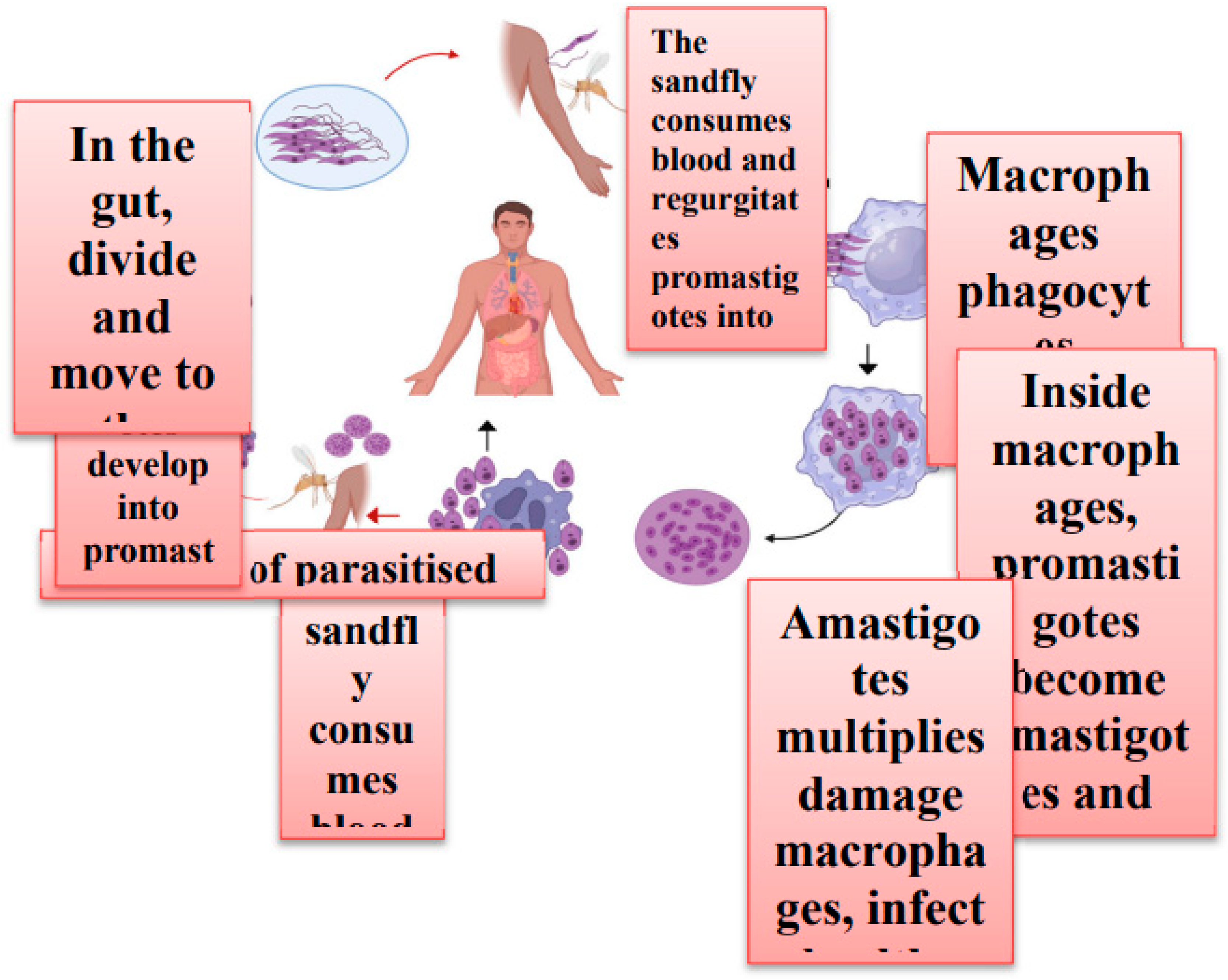

1. Introduction

2. Treatment Strategies and Challenges

| Drug Name | Generic Name | Drug Class | Brand names | Treatement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pentavalent antimony | sodium stibogluconate(SSG) | pentavalent antimonials | Pentostam® | Visceral, Cutaneous, and Mucosal forms of leishmaniasis and PKDL |

| Amphotericin b | Amphotericin b systemic | Polyenes | Amphocin, Fungizone | Visceral leishmaniasis or Kala-azar, second-line treatment for mucosal leishmaniasis and Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

| Amphotericin b liposomal | Amphotericin b liposomal systemic | Polyenes | AmBisome | Visceral leishmaniasis or Kala-azar, second-line treatment for mucosal leishmaniasis and Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

| Miltefosine | Miltefosine systemic | Anthelmintics | Impavido | Visceral, Cutaneous, and Mucosal forms of leishmaniasis |

| Pentamidine, Pentamidine isethionate, Pentamidine mesylate | Pentamidine systemic | Miscellaneous antibiotics, inhaled anti-infectives | Pentam, Nebupent, Pentam 300, Pentacarinat®, Lomidine® | Visceral, Cutaneous, and Mucosal forms of leishmaniasis |

| Amphotericin b lipid complex | Amphotericin b lipid complex systemic | Polyenes | Abelcet | Visceral leishmaniasis or Kala-azar, second-line treatment for mucosal leishmaniasis and Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

| Paromomycin sulfate, Paromomycin sulfate (15 %) ointment, | Humatin | aminoglycoside | Leshcutan® | Visceral, Cutaneous forms of leishmaniasis |

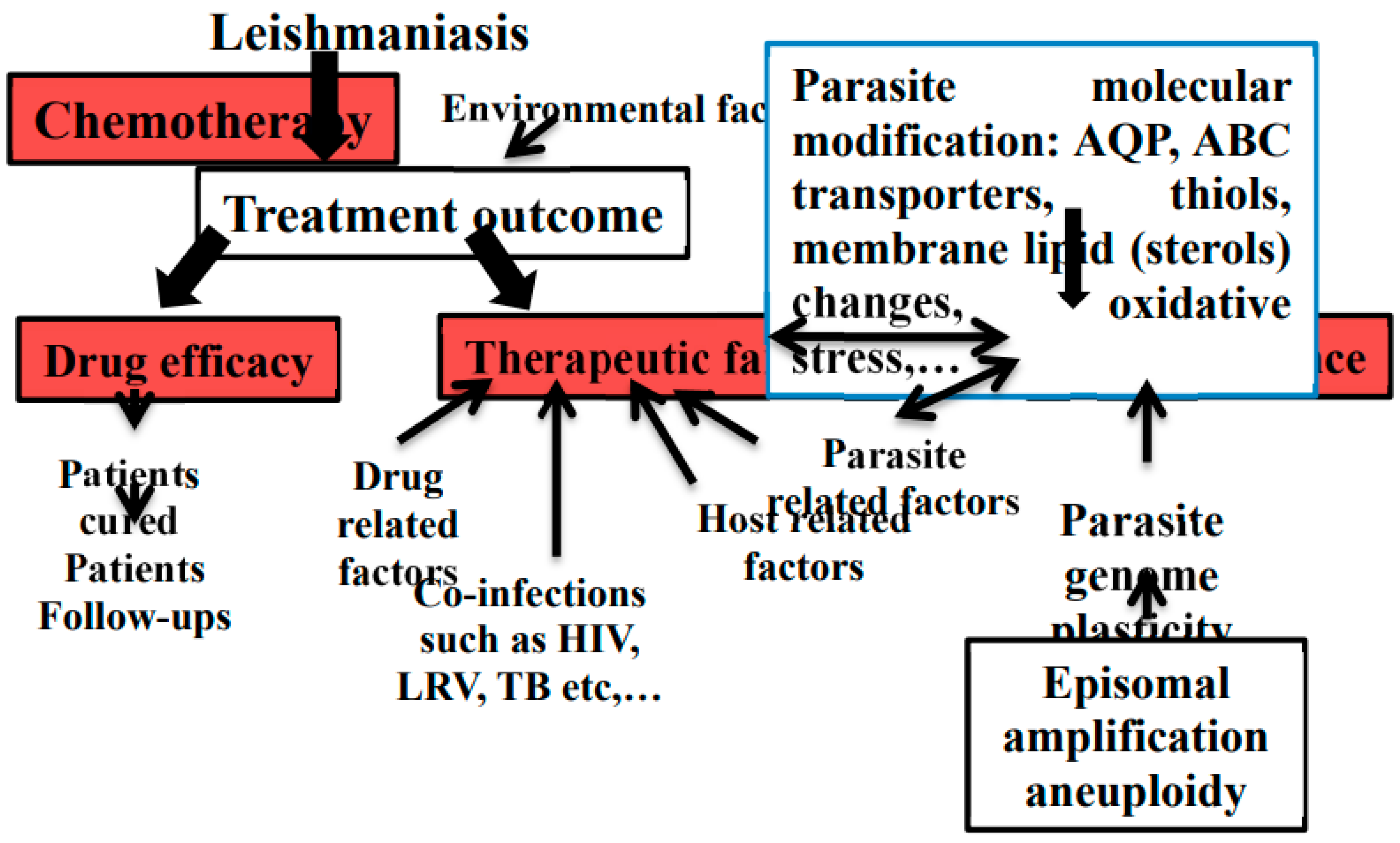

3. Drug Resistance in Leishmania

4. Reported Case Study

| S.no | Region | Patients | Clinical Manifestation | Species | Unsuccessful Treatment | Proposed Mechanisms for Failure/Relapse | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Asia | Male(6) | CL(3), VL(3) | L. tropica (CL), L. donovani (VL) | SS, AmB, AmB-L, MIL, GLU IL and GLU IM | CL- Hosts immunological factors and Parasite Resistance, VL- Hosts immunological factors and Parasite Resistance | [75,76,77,78,79,80] |

| 2 | South America | Male(21), Female (2) | CL(15), VL(6), MCL(1), DCL(1) | L. guyanensis (CL), L. panamensis (CL), L. naiffi (CL) L. tropica (CL), L. braziliensis (CL), L. infantum (VL), L. braziliensis (MCL), L. amazonensis (DCL) | SS, AmB, AmB-L, MIL, GLU IL and GLU IM, AmB e PENT / GLU e AmB, PENT (IL or IM) | CL- Dose-dependent resistance of the species, Route of drug administration, Inappropriate initial treatment, Presence of LRV virus, VL- Not Reported, MCL- Host immunological factors, DCL- Host immunological factors | [81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90], |

| 3 | North America | Male (1) | VL(1) | NR | GLU | VL- Inappropriate initial treatment | [91] |

| 4 | Europe | Male(4), Female (6) | CL(2), VL(8) | L. infantum (VL), L. tropica (CL), | L-AmB e AmB lipid complex, MIL e AmB, GLU | CL- Inappropriate initial treatment , VL- Host immunological factors, Mixed infection by two strains | [88,92,93,94,95,96,97] |

| 5 | Africa | Male(1), Female (1) | VL(2) | L. infantum (VL) | GLU, AmB IV, GLU / L-AmB, L-AmB, L-AmB + MIL / L-AmB, L-AmB + MIL / L-AmB and GLU / L-AmB | VL- Host immunological factors | [97] |

9. Conclusion

References

- Inceboz, T.; Inceboz, T. , “Epidemiology and Ecology of Leishmaniasis,” Curr. Top. Neglected Trop. Dis., Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- “Leishmaniasis.” https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis (accessed Jan. 31, 2024).

- “On the presence of peculiar parasitic organisms in the tissue of a specimen of Delhi boil | WorldCat.org.” https://search.worldcat.org/title/on-the-presence-of-peculiar-parasitic-organisms-in-the-tissue-of-a-specimen-of-delhi-boil/oclc/11826455 (accessed Jan. 31, 2024).

- Ruiz-Postigo, J.A.; et al. “Global leishmaniasis surveillance: 2019-2020, a baseline for the 2030 roadmap/Surveillance mondiale de la leishmaniose: 2019-2020, une periode de reference pour la feuille de route a l’horizon 2030.,” Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec., vol. 96, no. 35, pp. 401–420, Sep. 2021, Accessed: Feb. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=HRCA&sw=w&issn=00498114&v=2. 6752. [Google Scholar]

- Burza, S.; Croft, S.L.; Boelaert, M. , “Leishmaniasis,” Lancet, vol. 392, no. 10151, pp. 951–970, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Reithinger, R.; Dujardin, J.C.; Louzir, H.; Pirmez, C.; Alexander, B.; Brooker, S. , “Cutaneous leishmaniasis,” Lancet Infect. Dis., vol. 7, no. 9, pp. 581–596, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Desjeux, P.; et al. “Leishmaniasis,” Nat. Rev. Microbiol., vol. 2, no. 9, pp. 692–693, Sep. 2004. [CrossRef]

- “Cutaneous and Mucosal Leishmaniasis - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization.” https://www.paho.org/en/topics/leishmaniasis/cutaneous-and-mucosal-leishmaniasis (accessed Feb. 22, 2024).

- Sangueza, O.P.; Sangueza, J.M.; Stiller, M.J.; Sangueza, P. , “Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: A clinicopathologic classification,” J. Am. Acad. Dermatol., vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 927–932, Jun. 1993. [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Narváez, F.J.; Vargas-González, A.; Canto-Lara, S.B.; Damián-Centeno, A.G. , “Clinical picture of cutaneous leishmaniases due to Leishmania (Leishmania) mexicana in the Yucatan peninsula, Mexico,” Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz, vol. 96, no. 2, pp. 163–167, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Sunter, J.; Gull, K. , “Shape, form, function and Leishmania pathogenicity: from textbook descriptions to biological understanding,” Open Biol., vol. 7, no. 9, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Peer, G.D.G.; et al. “A Systematic Assessment of Leishmania donovani Infection in Domestic and Wild Animal Reservoir Hosts of Zoonotic Visceral Leishmaniasis in India,” Microbiol. Res. 2024, Vol. 15, Pages 1645-1654, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 1645–1654, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Peters, N.C.; et al. “In vivo imaging reveals an essential role for neutrophils in leishmaniasis transmitted by sand flies,” Science, vol. 321, no. 5891, pp. 970–974, Aug. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Stuart, K.; et al. “Kinetoplastids: related protozoan pathogens, different diseases,” J. Clin. Invest., vol. 118, no. 4, pp. 1301–1310, Apr. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, D.E.; Benchimol, M.; Rodrigues, J.C.F.; Crepaldi, P.H.; Pimenta, P.F.P.; de Souza, W. , “The Cell Biology of Leishmania: How to Teach Using Animations,” PLoS Pathog., vol. 9, no. 10, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, D.E.; Benchimol, M.; Rodrigues, J.C.F.; Crepaldi, P.H.; Pimenta, P.F.P.; de Souza, W. , “The Cell Biology of Leishmania: How to Teach Using Animations,” PLoS Pathog., vol. 9, no. 10, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Peer, G.D.G.; et al. “Exploration of Antileishmanial Compounds Derived from Natural Sources,” Antiinflamm. Antiallergy. Agents Med. Chem., vol. 23, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Capela, R.; Moreira, R.; Lopes, F. , “An Overview of Drug Resistance in Protozoal Diseases,” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, Vol. 20, Page 5748, vol. 20, no. 22, p. 5748, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ponte-Sucre, A.; et al. “Drug resistance and treatment failure in leishmaniasis: A 21st century challenge,” PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., vol. 11, no. 12, p. e0006052, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- “Current Treatment of Leishmaniasis: A Review.” https://benthamopen.com/ABSTRACT/TOANTIMJ-1-9 (accessed Jun. 18, 2022).

- Aronson, N.; et al. “Diagnosis and Treatment of Leishmaniasis: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH),” Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., vol. 96, no. 1, p. 24, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- “List of 14 Leishmaniasis Medications Compared - Drugs.com.” https://www.drugs.com/condition/leishmaniasis.html?submitted=true&category_id=&drugNameType=generics&approvalStatus=approved&rxStatus=all#sortby (accessed Mar. 26, 2024).

- Ritmeijer, K.; et al. “A comparison of miltefosine and sodium stibogluconate for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in an Ethiopian population with high prevalence of HIV infection,” Clin. Infect. Dis., vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 357–364, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Diro, E.; Lynen, L.; Mohammed, R.; Boelaert, M.; Hailu, A.; van Griensven, J. , “High Parasitological Failure Rate of Visceral Leishmaniasis to Sodium Stibogluconate among HIV Co-infected Adults in Ethiopia,” PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., vol. 8, no. 5, p. e2875, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, J.; Sundar, S. , “Current and emerging medications for the treatment of leishmaniasis,” Expert Opin. Pharmacother., vol. 20, no. 10, pp. 1251–1265, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- “Changing response to diamidine compounds in cases of kala-azar unresponsive to antimonial - PubMed.” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1938817/ (accessed Jul. 29, 2024).

- Mishra, M.; Biswas, U.K.; Jha, D.N.; Khan, A.B. , “Amphotericin versus pentamidine in antimony-unresponsive kala-azar,” Lancet, vol. 340, no. 8830, pp. 1256–1257, Nov. 1992. [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.; Chakravarty, J.; Agarwal, D.; Rai, M.; Murray, H.W. , “Single-dose liposomal amphotericin B for visceral leishmaniasis in India,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 362, no. 6, pp. 504–512, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Croft, S.L.; Engel, J. , “Miltefosine--discovery of the antileishmanial activity of phospholipid derivatives,” Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg., vol. 100 Suppl 1, no. SUPPL. 1, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Dorlo, T.P.C.; Balasegaram, M.; Beijnen, J.H.; de vries, P.J. , “Miltefosine: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of leishmaniasis,” J. Antimicrob. Chemother., vol. 67, no. 11, pp. 2576–2597, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlencord, A.; Maniera, T.; Eibl, H.; Unger, C. , “Hexadecylphosphocholine: oral treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in mice,” Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., vol. 36, no. 8, pp. 1630–1634, 1992. [CrossRef]

- Croft, S.L.; Neal, R.A.; Pendergast, W.; Chan, J.H. , “The activity of alkyl phosphorylcholines and related derivatives against Leishmania donovani,” Biochem. Pharmacol., vol. 36, no. 16, pp. 2633–2636, Aug. 1987. [CrossRef]

- Sunyoto, T.; Potet, J.; Boelaert, M. , “Why miltefosine—a life-saving drug for leishmaniasis—is unavailable to people who need it the most,” BMJ Glob. Heal., vol. 3, no. 3, p. 709, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wiwanitkit, V. , “Interest in paromomycin for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar),” Ther. Clin. Risk Manag., vol. 8, p. 323, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Ponte-Sucre, A.; et al. “Drug resistance and treatment failure in leishmaniasis: A 21st century challenge,” PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., vol. 11, no. 12, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.; et al. “Efficacy of miltefosine in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in India after a decade of use,” Clin. Infect. Dis., vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 543–550, Aug. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Rijal, S.; et al. “Increasing failure of miltefosine in the treatment of Kala-azar in Nepal and the potential role of parasite drug resistance, reinfection, or noncompliance,” Clin. Infect. Dis., vol. 56, no. 11, pp. 1530–1538, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Zerpa, O.; Padrón-Nieves, M.; Ponte-Sucre, A. , “American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis,” Drug Resist. Leishmania Parasites Consequences, Mol. Mech. Possible Treat., pp. 177–191, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

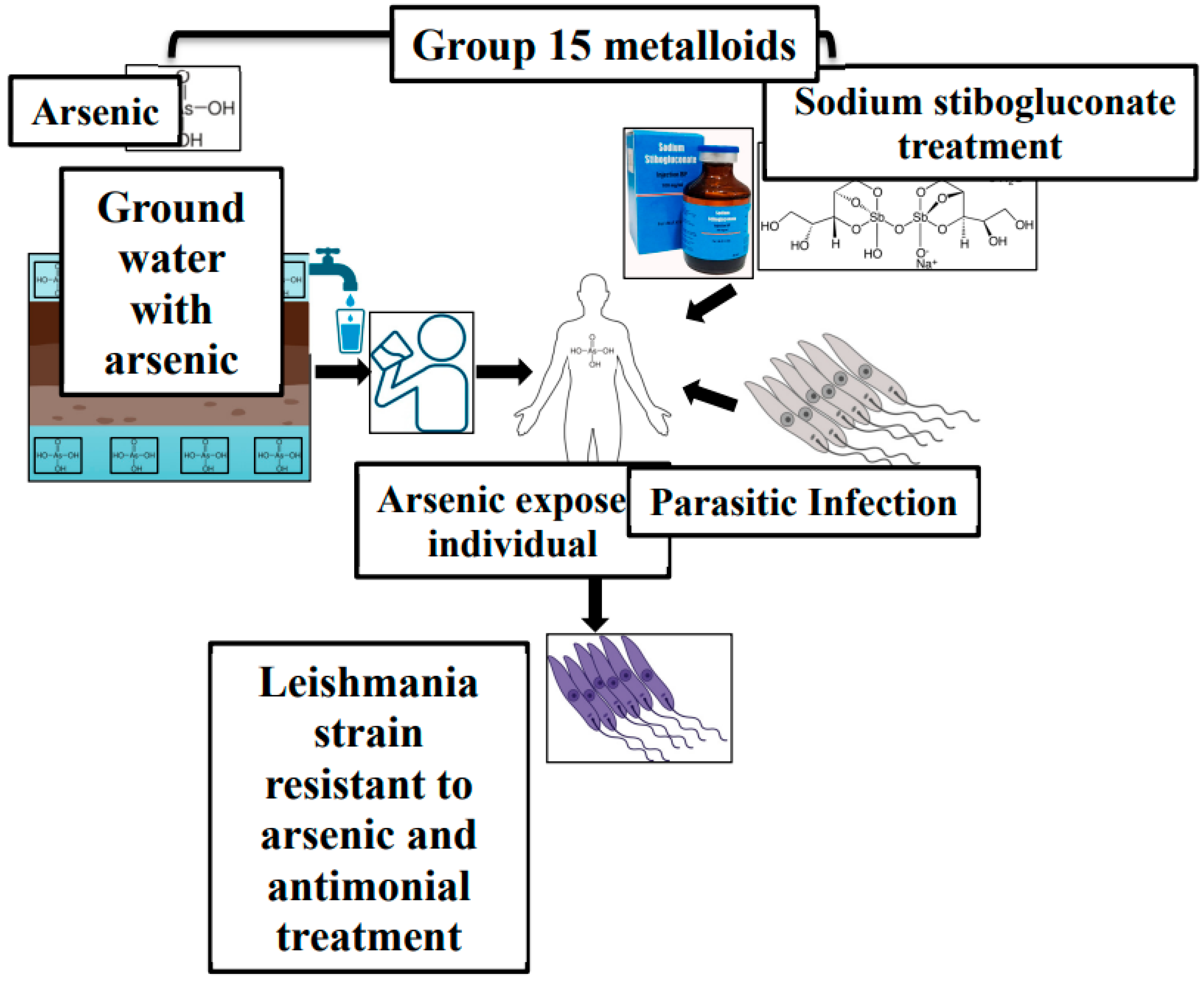

- Yan, S.; Jin, L.; Sun, H. , “51Sb Antimony in Medicine,” Met. Drugs Met. Diagnostic Agents Use Met. Med., pp. 441–461, Dec. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborti, D.; et al. “Arsenic groundwater contamination in Middle Ganga Plain, Bihar, India: a future danger?,” Environ. Health Perspect., vol. 111, no. 9, p. 1194, Jul. 2003. [CrossRef]

- “Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar): challenges ahead - PubMed.” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16778314/ (accessed Aug. 02, 2024).

- Mazumder, D.N.G. , “Effect of chronic intake of arsenic-contaminated water on liver,” Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., vol. 206, no. 2, pp. 169–175, Aug. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Perry, M.R.; et al. “Visceral Leishmaniasis and Arsenic: An Ancient Poison Contributing to Antimonial Treatment Failure in the Indian Subcontinent?”. [CrossRef]

- Roychoudhury, J. ; N. A.-I. journal of biochemistry; undefined 2008, “Sodium stibogluconate: Therapeutic use in the management of leishmaniasis,” Repos. Roychoudhury, N AliIndian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2008•repository.ias.ac.in, vol. 45, pp. 16–22, 2008, Accessed: Aug. 05, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Brochu, C.; et al. “Antimony uptake systems in the protozoan parasite Leishmania and accumulation differences in antimony-resistant parasites,” Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., vol. 47, no. 10, pp. 3073–3079, Oct. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Maharjan, M.; Singh, S.; Chatterjee, M.; Madhubala, R. , “Assessing aquaglyceroporin gene status and expression profile in antimony-susceptible and -resistant clinical isolates of Leishmania donovani from India,” J. Antimicrob. Chemother., vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 496–507, Mar. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Marquis, N.; Gourbal, B.; Rosen, B.P.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Ouellette, M. , “Modulation in aquaglyceroporin AQP1 gene transcript levels in drug-resistant Leishmania,” Mol. Microbiol., vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 1690–1699, Sep. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, G.; Wyllie, S.; Singh, N.; Sundar, S.; Fairlamb, A.H.; Chatterjee, M. , “Increased levels of thiols protect antimony unresponsive Leishmania donovani field isolates against reactive oxygen species generated by trivalent antimony,” Parasitology, vol. 134, no. Pt 12, p. 1679, Nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Croft, S.L.; Sundar, S.; Fairlamb, A.H. , “Drug resistance in leishmaniasis,” Clin. Microbiol. Rev., vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 111–126, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Légaré, D.; et al. “The Leishmania ATP-binding Cassette Protein PGPA Is an Intracellular Metal-Thiol Transporter ATPase,” J. Biol. Chem., vol. 276, no. 28, pp. 26301–26307, Jul. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Ouellette, M.; Lightbody, J.; Papadopoulou, B.; Rosen, B.P. , “An ATP-dependent As(III)-glutathione transport system in membrane vesicles of Leishmania tarentolae.,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 93, no. 5, p. 2192, Mar. 1996. [CrossRef]

- Ashutosh, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Sundar, S.; Goyal, N. Ashutosh; Sundar, S.; Goyal, N., “Molecular mechanisms of antimony resistance in Leishmania,” J. Med. Microbiol., vol. 56, no. Pt 2, pp. 143–153, Feb. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.C.; Beverley, S.M.; Cotrim, P.C. , “Functional genetic identification of PRP1, an ABC transporter superfamily member conferring pentamidine resistance in Leishmania major,” Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., vol. 130, no. 2, pp. 83–90, Aug. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Manzano, J.I.; García-Hernández, R.; Castanys, S.; Gamarro, F. , “A new ABC half-transporter in Leishmania major is involved in resistance to antimony,” Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., vol. 57, no. 8, pp. 3719–3730, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Perea, A.; Manzano, J.I.; Castanys, S.; Gamarro, F. , “The LABCG2 Transporter from the Protozoan Parasite Leishmania Is Involved in Antimony Resistance,” Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., vol. 60, no. 6, pp. 3489–3496, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, B.; et al. “Antimony-resistant but not antimony-sensitive Leishmania donovani up-regulates host IL-10 to overexpress multidrug-resistant protein 1,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 110, no. 7, pp. E575–E582, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

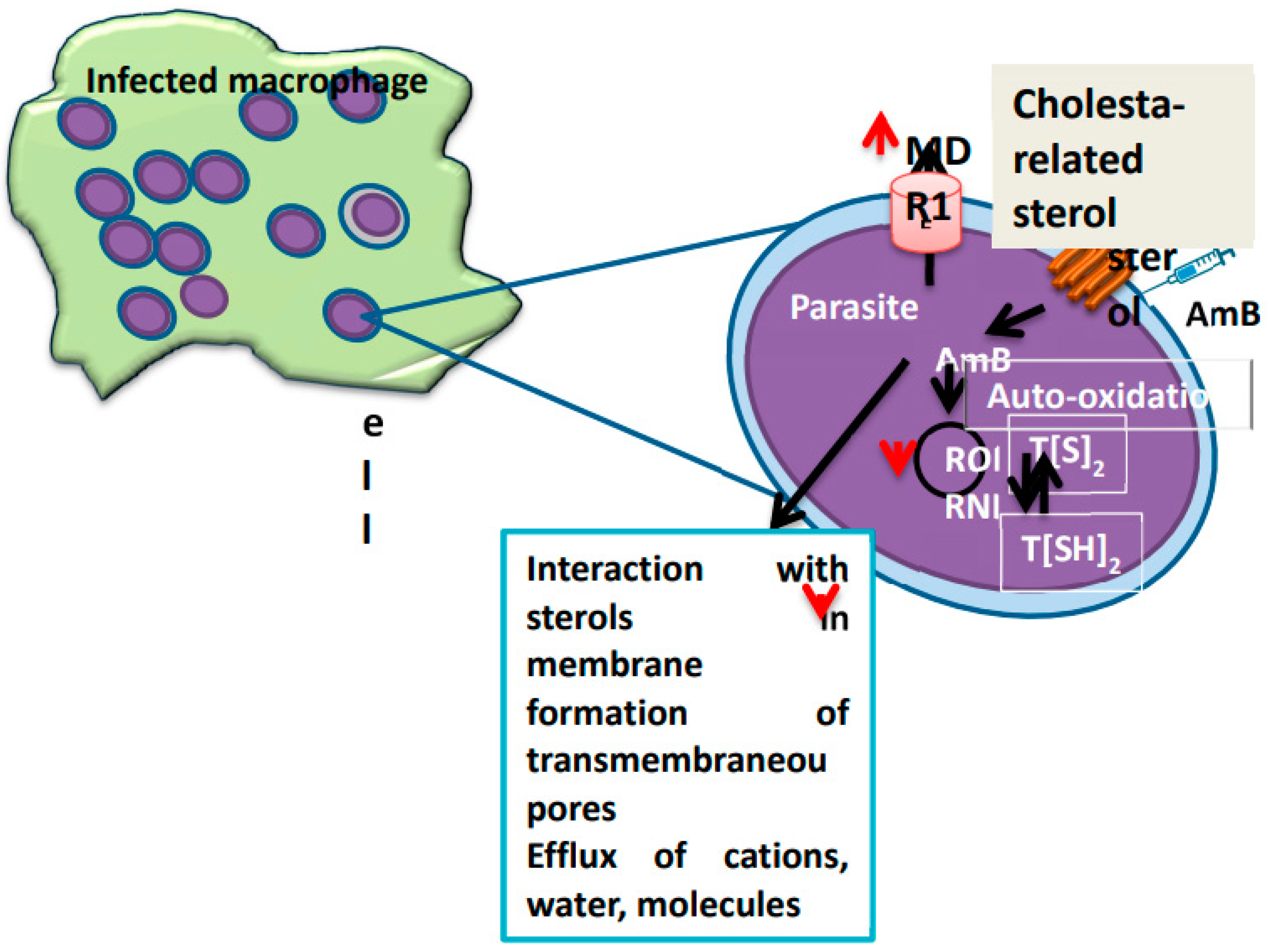

- Sundar, S.; Chakravarty, J. , “Liposomal amphotericin B and leishmaniasis: Dose and response,” J. Glob. Infect. Dis., vol. 2, no. 2, p. 159, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Purkait, B.; et al. “Mechanism of amphotericin B resistance in clinical isolates of Leishmania donovani,” Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 1031–1041, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Mwenechanya, R.; et al. “Sterol 14α-demethylase mutation leads to amphotericin B resistance in Leishmania mexicana,” PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., vol. 11, no. 6, p. e0005649, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.; Sen, S.S.; Muthuswami, R.; Madhubala, R. , “Stigmasterol as a potential biomarker for amphotericin B resistance in Leishmania donovani,” J. Antimicrob. Chemother., vol. 75, no. 4, pp. 942–950, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- del M, M.; Cossio, A.; Velasco, C.; Osorio, L. , “Risk factors for therapeutic failure to meglumine antimoniate and miltefosine in adults and children with cutaneous leishmaniasis in Colombia: A cohort study,” PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., vol. 11, no. 4, p. e0005515, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, V.K.; et al. “In vitro Susceptibility of Leishmania donovani to Miltefosine in Indian Visceral Leishmaniasis,” Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., vol. 89, no. 4, pp. 750–754, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

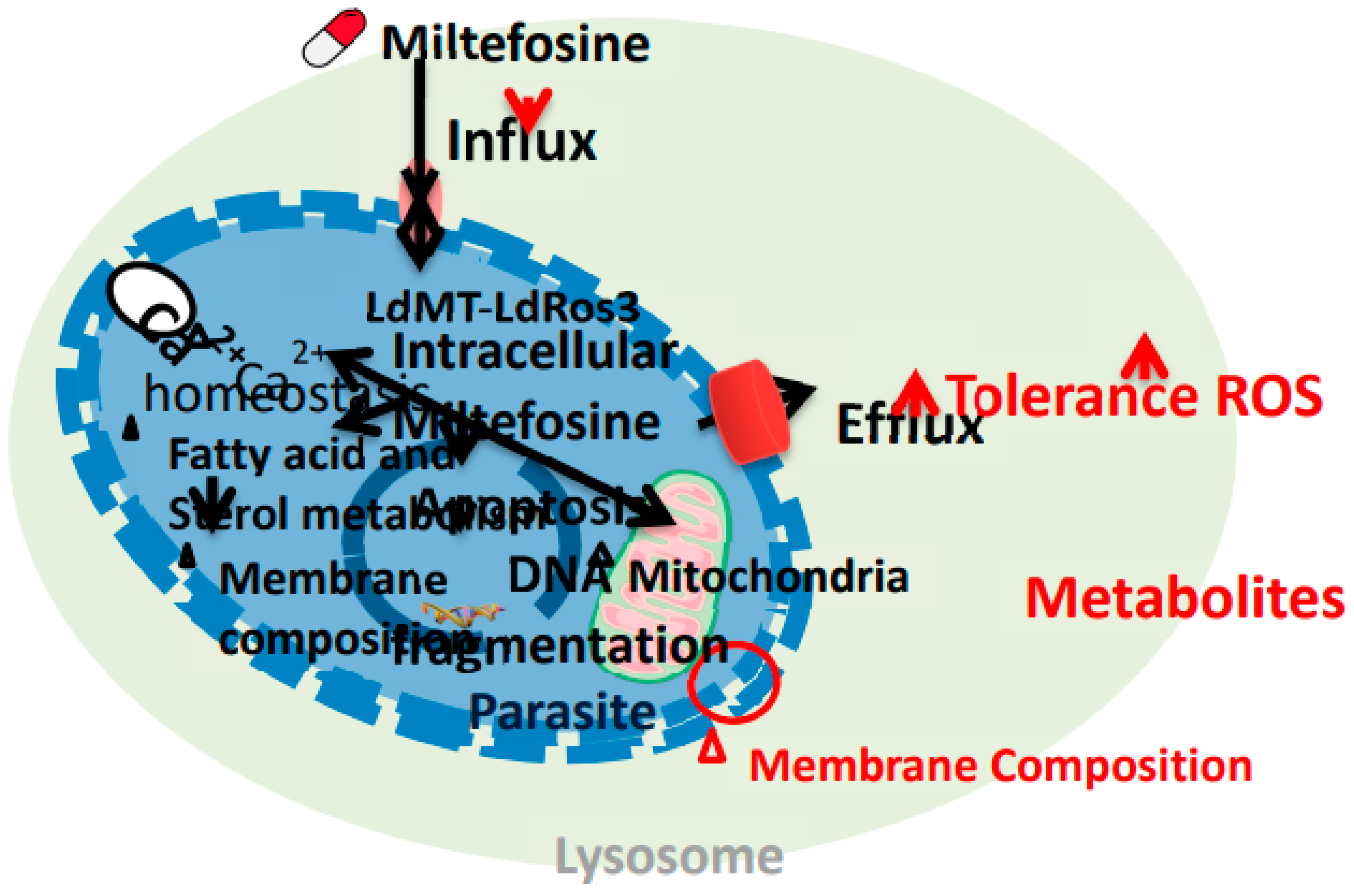

- Pinto-Martinez, A.K.; Rodriguez-Durán, J.; Serrano-Martin, X.; Hernandez-Rodriguez, V.; Benaim, G. , “Mechanism of action of miltefosine on Leishmania donovani involves the impairment of acidocalcisome function and the activation of the sphingosine-dependent plasma membrane Ca 2+ channel,” Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., vol. 62, no. 1, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Victoria, F.J.; Sánchez-Cañete, M.P.; Castanys, S.; Gamarro, F. , “Phospholipid translocation and miltefosine potency require both L. donovani miltefosine transporter and the new protein LdRos3 in Leishmania parasites,” J. Biol. Chem., vol. 281, no. 33, pp. 23766–23775, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Khanra, S.; Sarraf, N.R.; Das, A.K.; Roy, S.; Manna, M. , “Miltefosine Resistant Field Isolate From Indian Kala-Azar Patient Shows Similar Phenotype in Experimental Infection,” Sci. Reports 2017 71, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- “Control of the leishmaniases WHO TRS n° 949.” https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-TRS-949 (accessed Sep. 19, 2024).

- Maarouf, M.; De Kouchkovsky, Y.; Brown, S.; Petit, P.X.; Robert-Gero, M. , “In VivoInterference of Paromomycin with Mitochondrial Activity ofLeishmania,” Exp. Cell Res., vol. 232, no. 2, pp. 339–348, 97. 19 May. [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, V.; Sundar, S.; Dujardin, J.C.; Salotra, P. , “Elucidation of cellular mechanisms involved in experimental paromomycin resistance in leishmania donoVani,” Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., vol. 58, no. 5, pp. 2580–2585, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Jhingran, A.; Chawla, B.; Saxena, S.; Barrett, M.P.; Madhubala, R. , “Paromomycin: Uptake and resistance in Leishmania donovani,” Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., vol. 164, no. 2, pp. 111–117, Apr. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.K.; et al. “Phase 4 Pharmacovigilance Trial of Paromomycin Injection for the Treatment of Visceral Leishmaniasis in India,” J. Trop. Med., vol. 2011, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.; Chakravarty, J. , “Paromomycin in the treatment of leishmaniasis,” Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 787–794, 08. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Musa, A.M.; et al. “Paromomycin for the Treatment of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Sudan: A Randomized, Open-Label, Dose-Finding Study,” PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., vol. 4, no. 10, p. e855, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Hailu, A.; et al. “Geographical Variation in the Response of Visceral Leishmaniasis to Paromomycin in East Africa: A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomized Trial,” PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., vol. 4, no. 10, p. e709, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- de A, G.; et al. “Systematic Review of Treatment Failure and Clinical Relapses in Leishmaniasis from a Multifactorial Perspective: Clinical Aspects, Factors Associated with the Parasite and Host,” Trop. Med. Infect. Dis., vol. 8, no. 9, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Marovich, M.A.; et al. “Leishmaniasis recidivans recurrence after 43 years: A clinical and immunologic report after successful treatment,” Clin. Infect. Dis., vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 1076–1079, Oct. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Patole, S.; Burza, S.; Varghese, G.M. , “Multiple relapses of visceral leishmaniasis in a patient with HIV in India: a treatment challenge,” Int. J. Infect. Dis., vol. 25, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ekiz, Ö.; Rifaio, E.N.; Şen, B.B. ; G. C¸ulha; Özgür, T.; Do, A.C., “Leishmaniasis recidiva cutis of the lips mimicking granulomatous cheilitis,” Indian J. Dermatol., vol. 60, no. 2, p. 216, Apr. 2015.

- Al-Jawabreh, A. ; A. N.-Skin. D. for the; undefined 2007, “Leishmaniasis recidivans in a Palestinian Bedouin child,” Wiley Online Libr. Al-Jawabreh, A NasereddinSKINmed Dermatology Clin. 2007•Wiley Online Libr., vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 250–252, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, B.; Pandey, K. ; O. K.-A. J. of; undefined 2009, “Relapse of visceral leishmaniasis after miltefosine treatment in a Nepalese patient,” Res. Pandey, K Pandey, O Kaneko, T Yanagi, K HirayamaAmerican J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009•researchgate.net, vol. 80, no. 4, pp. 580–582, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Eichenberger, A.; et al. “A severe case of visceral leishmaniasis and liposomal amphotericin B treatment failure in an immunosuppressed patient 15 years after exposure,” BMC Infect. Dis., vol. 17, no. 1, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, A.; et al. “Failure of Liposomal-amphotericin B Treatment for New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis due to Leishmania braziliensis,” Intern. Med., vol. 59, no. 9, pp. 1227–1230, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gangneux, J.P.; et al. “Recurrent American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis - Volume 13, Number 9—07 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC,” Emerg. Infect. Dis., vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 1436–1438, 2007. 20 September. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.M.; et al. “Recurrent cutaneous leishmaniasis,” An. Bras. Dermatol., vol. 88, no. 3, pp. 462–464, 13. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Soares, G.H.C.; et al. “Case Report: Coinfection by Leishmania amazonensis and HIV in a Brazilian Diffuse Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Patient,” Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., vol. 103, no. 3, pp. 1076–1080, 20. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Vieira-Gonçalves, R.; et al. “First report of treatment failure in a patient with cutaneous leishmaniasis infected by Leishmania (Viannia) naiffi carrying Leishmania RNA virus: a fortuitous combination?,” Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop., vol. 52, p. e20180323, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, J.J.A.; Cunha, M.A.; Diniz, S.R.; Monteiro, M.G.L.; Araújo, S.P.; Luz, K.G. , “TRATAMENTO DE RECIDIVA DE LEISHMANIOSE VISCERAL EM CRIANÇA COM TERAPIA TRIPLA: RELATO DE CASO,” Brazilian J. Infect. Dis., vol. 25, p. 101206, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Vélez, I.D.; Colmenares, L.M.; Muñoz, C.A. , “Two cases of visceral leishmaniasis in Colombia resistant to meglumine antimonial treatment,” Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 231–236, Jul. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Dereure, J.; et al. “Visceral leishmaniasis. Persistence of parasites in lymph nodes after clinical cure,” J. Infect., vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 77–81, Jul. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Arboleda, M.; Barrantes, S.; Úsuga, L.Y.; Robledo, S.M. , “Successful treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis with intralesional meglumine antimoniate: A case series,” Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop., vol. 52, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Reinaldo, L.G.C.; et al. “Recurrent kala-azar: report of two cured cases after total splenectomy,” Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo, vol. 62, p. e31, 20. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.E.V.; et al. “Therapeutic failure of meglumine antimoniate in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis,” Rev. Esc. M Rivera, J AlgerEDITORIAL BOARD, 2005 • Rev., no. 4, 2005, Accessed: Oct. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.revistamedicahondurena.hn/assets/Uploads/Vol73-4-2005.

- Darcis, G.; et al. “Recurrence of visceral and muco-cutaneous leishmaniasis in a patient under immunosuppressive therapy,” BMC Infect. Dis., vol. 17, no. 1, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Stefanidou, M.P.; et al. “A rare case of leishmaniasis recidiva cutis evolving for 31 years caused by Leishmania tropica,” Int. J. Dermatol., vol. 47, no. 6, pp. 588–589, Jun. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, M.; Doulgerakis, C.; Pratlong, F.; Dedet, J.P.; Tselentis, Y. , “Treatment failure due to mixed infection by different strains of the parasite Leishmania infantum,” Acad. Antoniou, C Doulgerakis, F Pratlong, JP Dedet, Y TselentisAmerican J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2004•academia.edu, 2004, Accessed: Oct. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.academia.edu/download/31633346/71.

- Jeziorski, E.; et al. “Mucosal relapse of visceral leishmaniasis in a child treated with anti-TNFα,” Int. J. Infect. Dis., vol. 33, pp. e135–e136, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Villaverde, R.; Melguizo, J.B.; Solano, J.L.; Pérez, M.P.B.; Sintes, R.N. , “Leishmaniasis cutánea crónica: Respuesta a n-metil glucamina intralesional tras fracaso con paramomicina tópica,” Actas Dermosifiliogr., vol. 93, no. 4, pp. 263–266, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Morizot, G.; et al. “Antimony to Cure Visceral Leishmaniasis Unresponsive to Liposomal Amphotericin B,” PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., vol. 10, no. 1, p. e0004304, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- RP, P. ; Mukherjee R; Priyadarshini A; Gupta A; Vibhuti A; Leal E; Sengupta U; VM, K.; Sharma P; CE, M.; VS, R., Lyu X. Potential of nanoparticles encapsulated drugs for possible inhibition of the antimicrobial resistance development. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 Sep;141:111943. [CrossRef]

- RP, P. ; Vidic J; Mukherjee R, Chang CM. Experimental Methods for the Biological Evaluation of Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Risks. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Feb 11;15(2):612. [CrossRef]

- “Leishmaniasis emergence in Europe.” https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/leishmaniasis-emergence-europe (accessed Nov. 14, 2024).

- Kumar, S; Dhiman, R; CR, P.; AC, C.; Vibhuti, A; Leal, E; CM, C.; VS, R. Kumar S; Dhiman R; CR, P.; AC, C.; Vibhuti A; Leal E; CM, C.; VS, R., Pandey RP. Chitosan: Applications in Drug Delivery System. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2023;23(2):187-191. [CrossRef]

- Ruby, M; CC, G.; Pandey, R; VS, R.; VS, S. Ruby M; CC, G.; Pandey R; VS, R.; VS, S., Ajay AK. Autophagy as a Therapeutic Target for Chronic Kidney Disease and the Roles of TGF-β1 in Autophagy and Kidney Fibrosis. Cells. 2023 Jan 26;12(3):412. [CrossRef]

- Khatri, P; Rani, A; Hameed, S; Chandra, S; CM, C. Khatri P; Rani A; Hameed S; Chandra S; CM, C., Pandey RP. Current Understanding of the Molecular Basis of Spices for the Development of Potential Antimicrobial Medicine. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023 Jan 29;12(2):270. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S; Khatri, P; Fatima, Z; RP, P. Tripathi S; Khatri P; Fatima Z; RP, P., Hameed S. A Landscape of CRISPR/Cas Technique for Emerging Viral Disease Diagnostics and Therapeutics: Progress and Prospects. Pathogens. 2022 Dec 29;12(1):56. [CrossRef]

- RP, P. ; Mukherjee R, Chang CM. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance system mapping in different countries. Drug Target Insights. 2022 Nov 30; 16:36-48. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).