1. Introduction

Enterohemorrhagic

Escherichia coli (EHEC) is a zoonotic pathogen that poses a significant public health concern. The EHEC most relevant to human health is serotype O157:H7, which can cause diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis and Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS) in humans [

1]. HUS, a serious disease with global distribution, has a low incidence in industrialized countries such as the USA, Canada and Japan, with 1-3 cases per 100,000 children under age five [

2]. In contrast, Argentina experiences endemic levels of HUS, particularly affecting young children [

3]. Ruminants, especially cattle, are the primary reservoir of EHEC [

4], with intermittent shedding of the bacteria through feces. Shedding is particularly high in young calves and around weaning age [

5].

Research indicates that vaccinating cattle against EHEC O157:H7 can effectively reduce colonization. A simulation based on data from The Health Protection Scotland's enhanced surveillance system predicts that cattle vaccination could decrease EHEC O157:H7 shedding by approximately 50% and this decrease would ultimately reduce the cases in humans by 85% [

6]. This highlights the potential of cattle vaccination as a strategy to lower food contamination and consequently reduce HUS cases.

Additionally, several EHEC O157:H7 virulence factors can elicit immune responses in cattle during natural or experimental infection. Research of experimental and natural infections has shown that calves produce serological responses to proteins encoded by the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) such as Intimin (bacterial adhesin) and the type 3 secretion system (T3SS secretory proteins EspA and EspB, and the bacterial receptor Tir [

7].

The mouse model has been central to assessing antigenicity and immunogenicity in immunological research on anti-EHEC candidate vaccines. For example, it has been used to evaluate protection in newborn mice from EHEC challenge [

8], assess cytokine profile response after vaccination [

9], compare immunization routes [

10], explore novel EHEC vaccine formats [

11], and test the efficacy of bivalent vaccines such as Brucella-EHEC [

12], OMV-based vaccine formulations [

13], chimeric antigens [

14,

15] and candidate conjugated vaccines [

16].

On the other hand, Neonatal Calf Diarrhea (NCD) is a multifactorial disease in newborn cattle, primarily caused by pathogens such as enterotoxigenic

Escherichia coli (ETEC F5+/K99),

Salmonella spp, Bovine Coronavirus (BCoV) and Bovine Rotavirus type A (BRoVA) [

17]. Current NCD vaccines available on the market generally contain inactivated ETEC and

Salmonella. Based on promising findings from recombinant γ-intimin and EspB proteins of EHEC, we aimed to use these same proteins in the ETEC pathotype and

Salmonella dublin to stimulate an immune response against these microorganisms and potentially protect calves from NCD. Additionally, antibodies produced against these EHEC proteins, may reduce EHEC O157:H7 colonization in cattle, thereby helping to minimize food contamination.

Since existing bovine NCD vaccines also contain BCoV and BRoVA, this study also evaluated the combination of the recombinant bacteria with these viral particles to ensure no interference with the vaccine’s immunogenic properties. We assessed the immune response in mice and guinea pigs vaccinated with a recombinant chimeric protein, comprising the EspB and the C-terminal end of γ-intimin (Int280γ) antigens of EHEC O157:H7, anchored to the membrane of ETEC and Salmonella dublin strains. This strategy aims to improve the efficacy of the NCD vaccine to protect calves against neonatal diarrhea while contributing positively to human health by reducing HUS transmission.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production of EHEC Recombinant Proteins in ETEC and Salmonella dublin

The gene synthesis of a chimeric sequence encoding EspB and Int280γ, fused by a linker, was performed at Genewiz gene synthesis company (

www.genewiz.com). The antigenic sequence also contained the coding sequences for Wza-Omporf1 in the N-terminal region, where Wza corresponds to the signal sequence of an enterobacterial lipoprotein and Omporf1 is an outer membrane protein of

Vibrio anguillarum [

18]. The chimera’s estimated molecular weight was 74 kDa.

The chimeric construct included BamHI and HindIII restriction sites at its ends, enabling its insertion into the pUC57 vector and subsequently into the pTrcHis2B vector (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, USA). The pTrcHis2B vector with the corresponding ligated insert was transformed into E. coli DH5 and the successful ligation was then confirmed by PCR. The vector added a histidine and a c-Myc tag sequence to the C-terminal end of the chimera. The histidine tag facilitated detection and purification. This recombinant gene was designated BLI280..

Enterotoxigenic E. coli B41 (ETEC) and Salmonella enterica serovar dublin 98/167 (Salmonella dublin) strains were cultured in LB medium, then transformed by electroporation with pTrcHis2B-BLI280. Transformed bacteria were selected for ampicillin resistance conferred by the plasmid. Colonies of ETEC and S. dublin transformed with the pTrcHis2B-BLI280 plasmid were inoculated and grown into 5 ml of MINCA broth with Vitox (for ETEC) and LB (for S. dublin) respectively, each supplemented with 100 µg/ml ampicillin, at 37 °C with 200 rpm agitation. A 250 µl aliquot of each culture was inoculated into 25 ml of the respective media supplemented with ampicillin and grown with agitation until reaching a OD600nm of 0.6-0.8. At this point, protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside) for 4 h with 200 rpm agitation at 37 °C. The cultures were then centrifuged (3,000 x g, 10 min, 4 °C), and the resulting pellets were retained for vaccine formulation after inactivation.

Recombinant His-tagged Int280γ and EspB proteins was prepared as previously described [

19]. Briefly, the gene fragment (843 bp) encoding the 280 carboxyl-terminal amino acids of γ -Intimin and the EspB gene were amplified by PCR from a bovine EHEC O157:H7 isolation. The amplified DNA fragments were cloned into the His-tag expression vector pRSET-A (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, USA). The resulting constructs were transformed into chemically competent

E. coli BL21 (D3)/pLysS, following the manufacturer. This chimeric sequence was also cloned into the pRSET-A vector, and this construction was used to transform

E. coli BL21 (D3)/pLysS.

Protein expression was then induced by adding 1mM IPTG, and His-tagged proteins were purified from the lysates by affinity chromatography on nickel-agarose columns (ProBond Nickel-Chelating Resin, Invitrogen Corporation), eluted under denaturing conditions, and dialyzed in PBS pH 7.4.

2.2. Inactivation of Recombinant ETEC and Salmonella dublin

Bacteria were grown at 37 °C in suitable media for recombinant protein expression, then centrifuged at 7,000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended with a formalin (40% stabilized with methanol) solution in phosphate buffered saline, PBS pH 7.4 (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4). Inactivation was performed by shaking the bacterial suspensions at 150 rpm for 1 h at room temperature, then transferring to 4 °C. The suspensions were inactivated using varying concentrations of formalin (0.2% and 0.3% v/v), incubation times (8, 24 and 72 h), and temperatures (4 and 37 °C). Inactivation was confirmed by plating samples of the treated bacterial suspension on Trypticase Soy agar and incubating at 37 °C for 7 days.

2.3. Cellular Localization of the Chimera Protein Detection

The chimera expression on the outer membrane as previously reported [

18]. Cells from bacterial-induced cultures were centrifuged at 10,000 x

g for 2 min, washed three times with PBS, and resuspended in 1.5 ml of Tris-HCl-NaCl buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0, containing 0.3% NaCl). The cell suspension was subjected to ultrasound sonication for 5 min on ice, using a 10-second on/off pulse cycle and 20-50% amplitude. The resulting supernatant was further centrifuged at 10,000 x

g x g for 1 h at 4 °C to remove the unbroken cells and debris and isolate the total membrane fraction. This new supernatant was considered the soluble cytoplasmic/periplasmic fraction.

Further outer membrane fractioning was performed by resuspending the obtained pellet with 0.4 ml of HEPES buffer (10 mM [pH 7.4], containing 1% sodium lauryl sarcosine) to solubilize the inner membrane. This resuspension was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, followed by ultracentrifugation at 20,000 x g for 1 h at 4 °C to obtain the outer membrane. Each fractionated sample was stored for subsequent analysis.

2.4. Western Blot Assay

The samples obtained from the inactivation and cell fractionation procedures were examined by Western blot. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using a 12% w/v polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions and transferred onto 0.45-µm nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham-Pharmacia, Germany) for immunoblotting. The membranes were blocked with 3% nonfat dry milk in PBS (pH 7.4) for 1 h at 37 °C with agitation, then washed three times with PBS-T and incubated with the appropriate serum sample for 1 h. Following three additional washes, the membranes were incubated for 1 h with HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-bovine IgG (Bethyl Laboratories, Texas, USA) diluted 1:5000 in PBS-T. The signal was revealed with 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Pierce, Rockford, USA).

Western blot was performed on serum samples collected before and after immunization, from each vaccinated group to confirm the specificity of the antibody response. Serum from a bovine previously inoculated with the recombinant EspB and Int280γ antigens (1:500 dilution) was used as a positive control.

2.5. Strains and Production of Coronavirus and Rotavirus

Bovine Rotavirus UK (BRV UK) and Bovine Coronavirus (BCoV) Mebus strains were produced using D-MEM (Gibco, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 2 µg/mL of trypsin and antibiotics. BRV UK was replicated in monkey kidney cells (MA-104), while BCoV Mebus strain was replicated in bovine kidney (MDBK) cells. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and viral replication was monitored by the appearance of cytopathic effects after approximately 48 to 72 h. Once cytopathic effects were observed, the cells and virus were subjected to freeze-thaw cycles to release the viral particles, then clarified by centrifugation at 3,500 rpm for 20 min. The resulting supernatants, containing the viral strains, were then stored at -80 °C until further use.

Inactivation of the viral strains was performed by treating the samples with 0.5% formalin for 48 h at 4 °C.

2.6. Fluorescent Focus Reduction Assay

The virus neutralization (VN) assay was performed as previously described [

20]. Briefly, guinea pig serum samples were heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min. Serial 4-fold dilutions of each sample (ranging from1:4 to 1:1024) were placed in quadruple in 96-well plates and mixed with an equal volume of group A Rotavirus

to obtain a mixture containing 100 FFU/100 μl. This resulted in a final neutralization stage of 1:8 to 1:2048. An additional well without virus was included to assess the potential toxicity of the serum on cells. Each assay also included positive control sera with established Rotavirus antibody titers and negative controls for internal reference. Guinea pig reference samples were obtained from naturally seronegative and vaccinated animals.

The serum–virus mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, followed by the addition of 100 μl of MA-104 cell suspension containing between 200,000 ± 50,000 cells. After a 3-day incubation at 37 °C, the plates were fixed with 70% acetone. Detection was performed using a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-RV polyclonal antiserum derived from a hyperimmunized, colostrum-deprived calf.

The test was considered valid if the virus titration rechecks resulted in an infectious titer of 100 (TCID

50), with an acceptance range of 50–200 TCID

50. The positive control was required to yield its expected titer within ± 1 standard deviation (SD), while the negative serum should show no neutralization (evident by cytopathic effect in the monolayer). Additionally, control cells (cells plus culture medium, without serum and without virus) were expected to maintain an intact monolayer. VN Ab titers were calculated by the Reed and Muench method [

21], with negative serum samples assigned an arbitrary value of 0.30 for calculation.

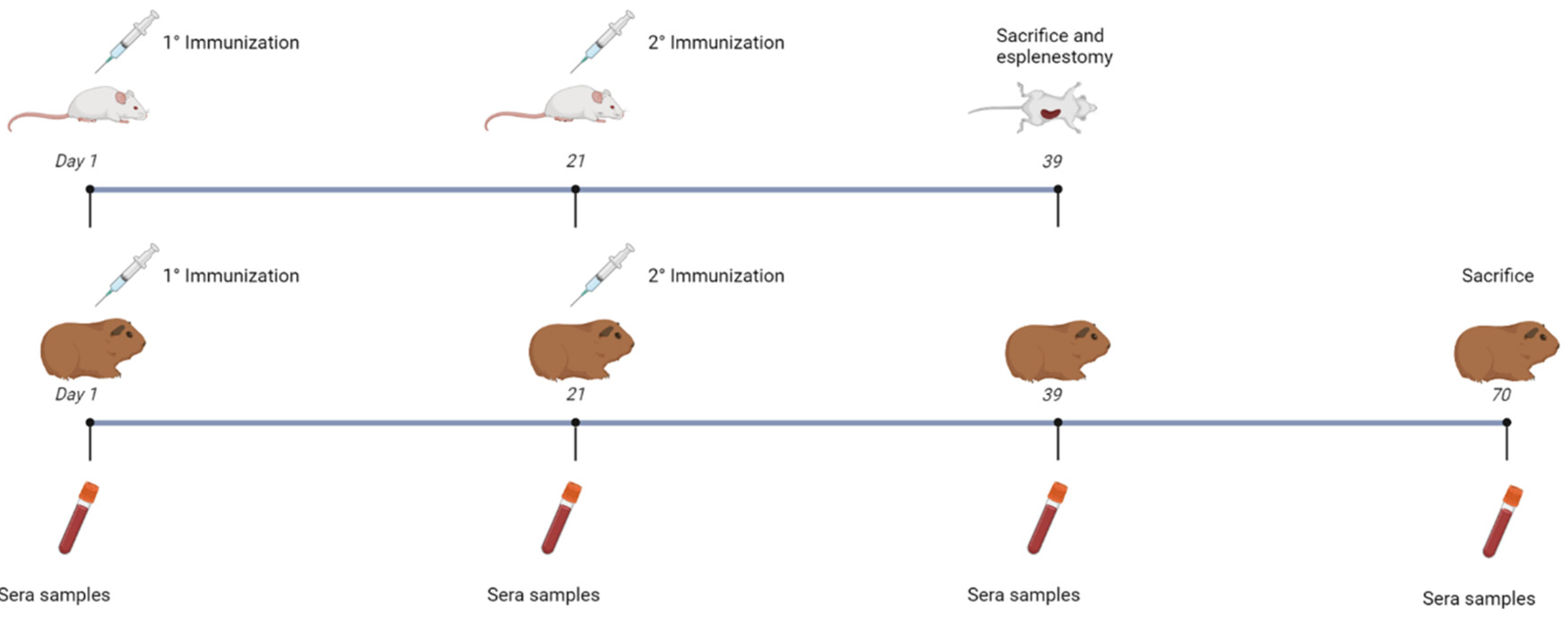

2.7. Animal Models and Immunization

In this study, mice (male BALB/c, 3 months old) and guinea pigs (female Hartley, 4 months old) were utilized as animal models. The mice were divided into eight groups, seven of which included five vaccinated mice each, with the remaining group (control) comprising four animals. Each animal received two vaccine doses, administered subcutaneously in the neck area at 21-day intervals, using ISA 50 as the adjuvant in a 50%:50% ratio with respect to the aqueous phase. The groups were numbered from 1 to 8 and vaccinated according to the specifications in

Table 1A. Serum samples were collected from both animal models on days 1 and 21 post-vaccination, with additional sampling on days 39 and 70 post-vaccination for guinea pigs and at day 39 for mice.

The guinea pig cohort consisted of ten animals divided into two groups of five. Each animal received two vaccine doses, administered subcutaneously in the neck area at 21-day intervals, using ISA 50 as the adjuvant in a 50%:50% ratio with respect to the aqueous phase. The groups were numbered as 1 and 2 and vaccinated according to the specifications in

Table 1B.

Table 1.

B: Groups of vaccinated guinea pigs.

Table 1.

B: Groups of vaccinated guinea pigs.

| Groups of guinea pigs |

Treatments |

Details |

| Control |

Control

|

1 mL of PBS |

| Vaccinated |

Inactivated ETEC B41 and Salmonella dublin expressing Chimera proteins + BRoVA UK and BCoVB Mebus |

1.108 CFU of inactivated ETEC B41 and Salmonella dublin expressing Chimera proteins resuspended with 1.107 FFU BRoVA UK and BCoVB Mebus |

Animals were kept in ventilated cages and housed under standardized conditions with regulated daylight, humidity, and temperature. The animals received food and water ad libitum. The animal experiments were authorized by the Institutional Committee for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals CICUAE INTA CICVyA approved the study (CICUAE 09/2023).

2.8. IgG Specific Antibody ELISA

Specific IgG antibody titers against the chimera, Int280γ, and EspB were measured in sera samples from the mice and guinea pigs using an indirect ELISA. Briefly, 96-well ELISA plates (Ivema, ES08 Buenos Aires, Argentina) were coated ON at 4 °C with 500 ng/well of each protein in carbonate/bicarbonate buffer pH 9.6. Plates were then washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T, pH 7.4) and blocked with 3% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at 37 °C to prevent non-specific binding. Four-fold serial dilutions of mouse and guinea pig serum samples in 3% nonfat dry milk were added (100 µl/well), and the plates were incubated for 1 h 37 °C. Each plate included a blank control with 3% nonfat dry milk alone, a known positive sample, and a negative sample. After washing with PBS-T, the plates were incubated for 1 h with 100 µl of goat anti-mouse IgG or goat anti-guinea pig conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, USA), both at a dilution of 1:4000 in 3% nonfat dry milk. The plates were washed four times with PBS-T followed by the addition of ABTS [2,2_-azino-di (3-ethyl-benzthiazoline sulphonic acid)] (Amresco, Solon, USA) substrate in citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 4.2) with 0.01% H2O2 (100 µl/well). Reactions were stopped after 10 min with 100 µl/well of 5% SDS, and absorbance was measured at 405nm (OD405) using a BioTek ELx808 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, USA).

Antibody titers were expressed as the logarithm of the reciprocal of the end-point dilution that yielded an OD405nm above the cut-off value, which was calculated as the average plus two times the standard deviation of the optical densities of the samples measured on day 0.

2.9. Specific Antibody BCoV and BRoVA ELISA

The antibody titer in both animal models was determined using a double-sandwich ELISA assay [

22]. Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with hyperimmune anti-BCoV serum in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) and incubated for 18 h at 4-8 °C. The plates were then blocked with 10% nonfat milk in PBS-T. Subsequently, clarified supernatants from HRT-18 or MA-104 cultures infected with standardized titer of coronavirus were added to the wells. Supernatants from uninfected cells were also incorporated in the assay as a control.

Two-fold serial dilutions of the samples and their respective positive and negative controls were added to the wells. Finally, commercial polyclonal anti-mouse or anti-guinea pig antibodies conjugated to peroxidase were added, depending on the species. The reaction was developed using H2O2 and ABTS, then stopped with SDS, and the absorbance was measured at 405 nm (Multiskan FC).

2.10. Antigen- Specific IL-17, IFN-γ and IL-5 Production by Spleen Cells

Spleens from untreated and immunized mice were passed through a 40-mm cell strainer to obtain a single-cell suspension. Spleen cells were seeded in 48 well culture plates in a final volume of 500 µl/well RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum, containing 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. All cell samples were stimulated with 2 µg/ml antigen or medium only. After 72 h of incubation (37 °C and 5% CO2), IFN-γ, IL-5 and IL-17 concentrations were quantified in supernatants by ELISA (BD Biosciences, San Diego, USA), using conditions recommended by the manufacturer.

2.11. Statistical Analysis.

The data were evaluated statistically by two-way or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni for multiple comparisons (via the GraphPad Prism® software). Differences were considered significant at a p <0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Design, Cloning and Introduction into Carrier Bacteria of Chimera Protein

The chimeric protein was designed as a composite from the N- to C-terminus in the sequence Wza-Omporf-EspB-linker-Int280γ. The gene encoding this chimera, designated BLI280, was synthesized de novo and initially cloned into a cloning vector. After excision, the gene was inserted into the expression vector pTrcHis2B, yielding pTrcHis2B-BLI280. This construct was introduced via electroporation into Salmonella enterica serovar dublin and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli.

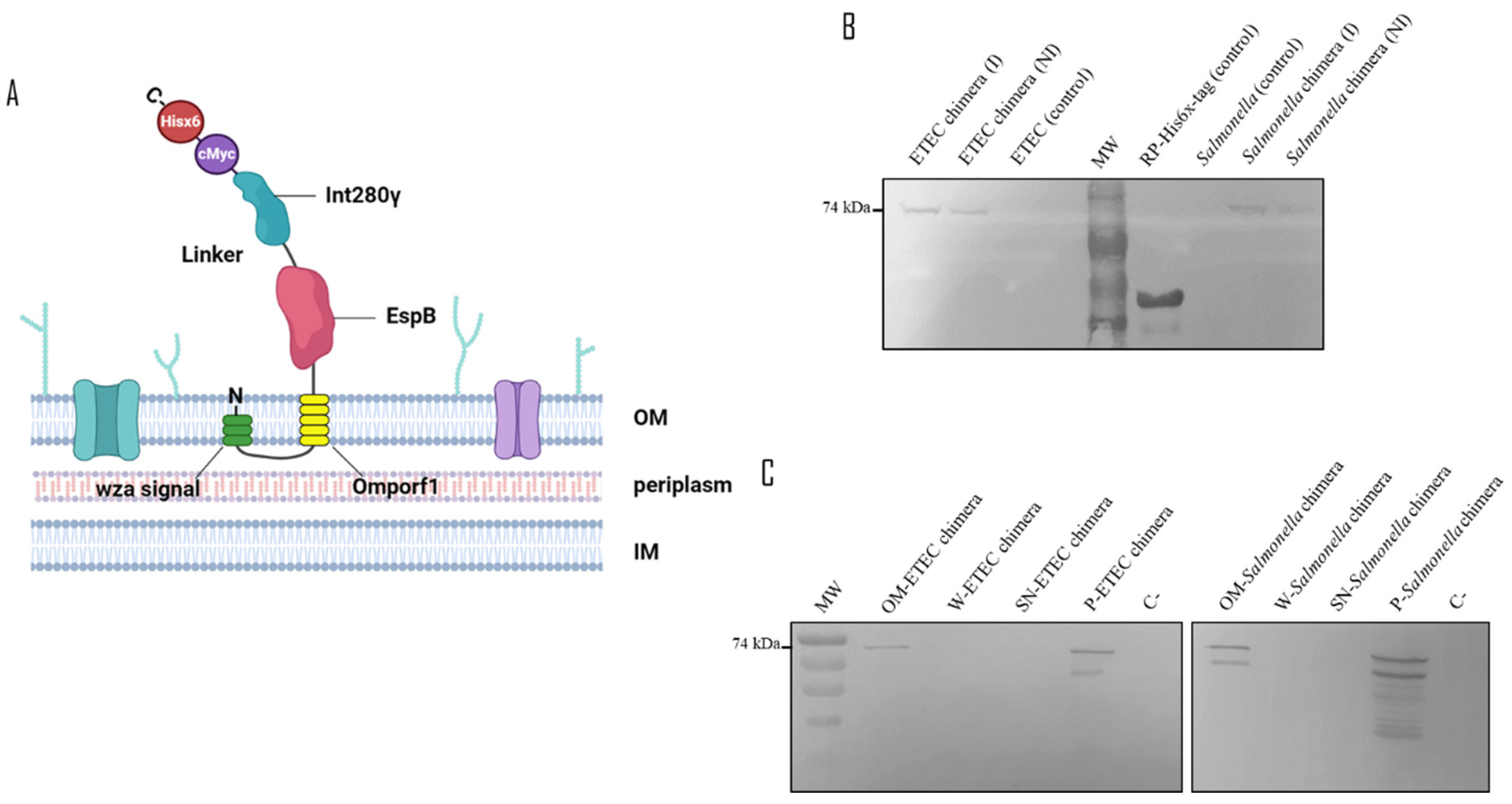

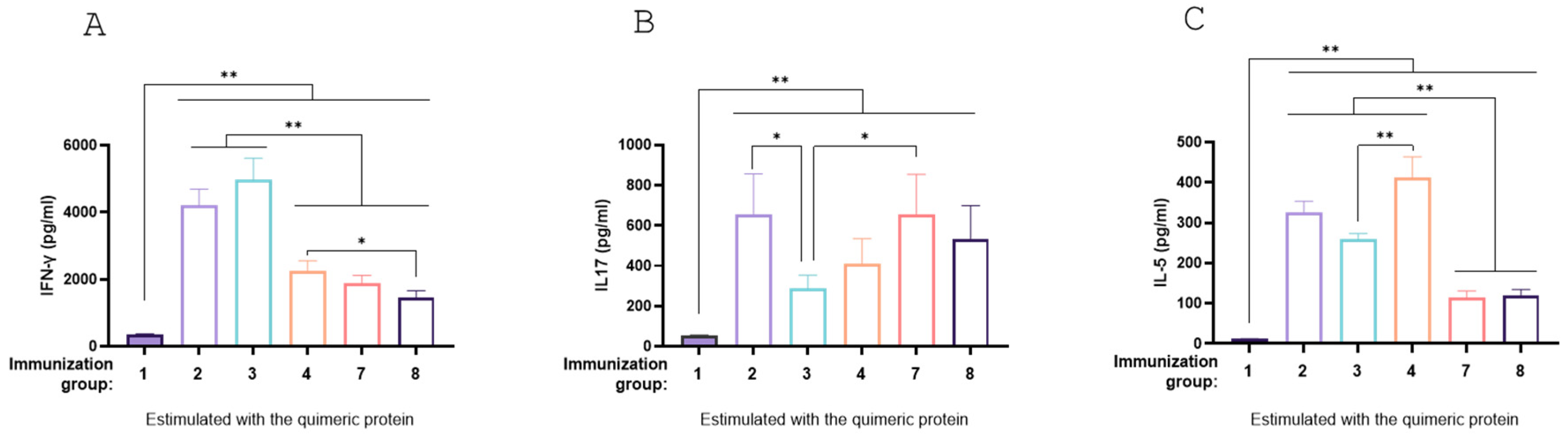

3.2. Membrane-Anchoring of Chimeric Protein to ETEC and Salmonella dublin

The anchorage of the chimera to the bacterial membranes (

Figure 1A) in the transformed bacteria ETEC and

Salmonella dublin pTrcHis2B-BLI280 was assessed by western blotting of cytoplasm and membrane fractions (obtained by ultracentrifugation) of induced and non-induced bacteria. Chimera in western blots was detected using an anti-histidine tag (Hisx6) antibody and bovine serum specific against the previously obtained EspB and Int280γ antigens [

23], as detailed in the Materials and Methods section.

The presence of the chimeric protein was confirmed in both ETEC and

Salmonella samples, irrespective of IPTG induction (

Figure 1B,C). Moreover, the chimeric protein appeared exclusively in the outer membrane fraction of both bacteria, as corroborated by negative results in analyses of the pellet washings, pellet supernatants and total bacterial culture supernatants (

Figure 1B,C). Further analyses of recombinant ETEC and

Salmonella (

Supplementary Figure S1) with bovine serum specific for EspB and Int280γ also confirmed the outer-membrane localization. These findings indicate that the chimera is anchored to the outer bacterial membrane.

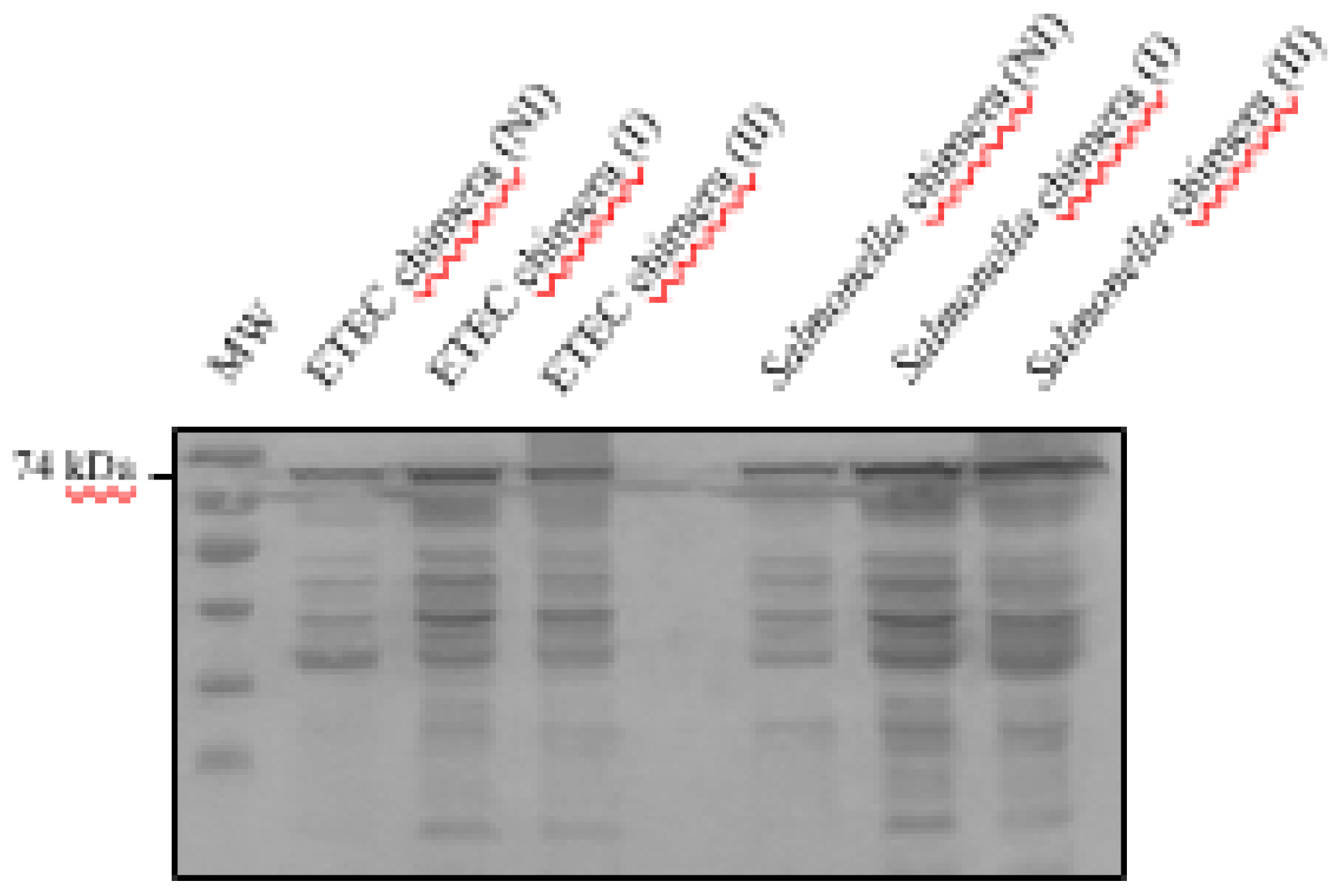

3.3. Inactivation of Recombinant ETEC and Salmonella dublin and Antigenic Preservation in Vaccine Formulation

Inactivation assays performed on induced suspensions of chimeric recombinant ETEC (refer to materials and methods and

Supplementary Figure S2 indicated that the best inactivation condition consisted of applying 0.2%

v/v of formalin for 96 h at 4 °C. This treatment led to a slight decrease in chimeric protein concentrations, as observed by Western blotting (

Figure 2). We also assessed the preservation and integrity of the antigen in recombinant ETEC and

Salmonella dublin after storage periods of 2 to 7 months at 4 °C, by western blot (

Supplementary Figure S3).

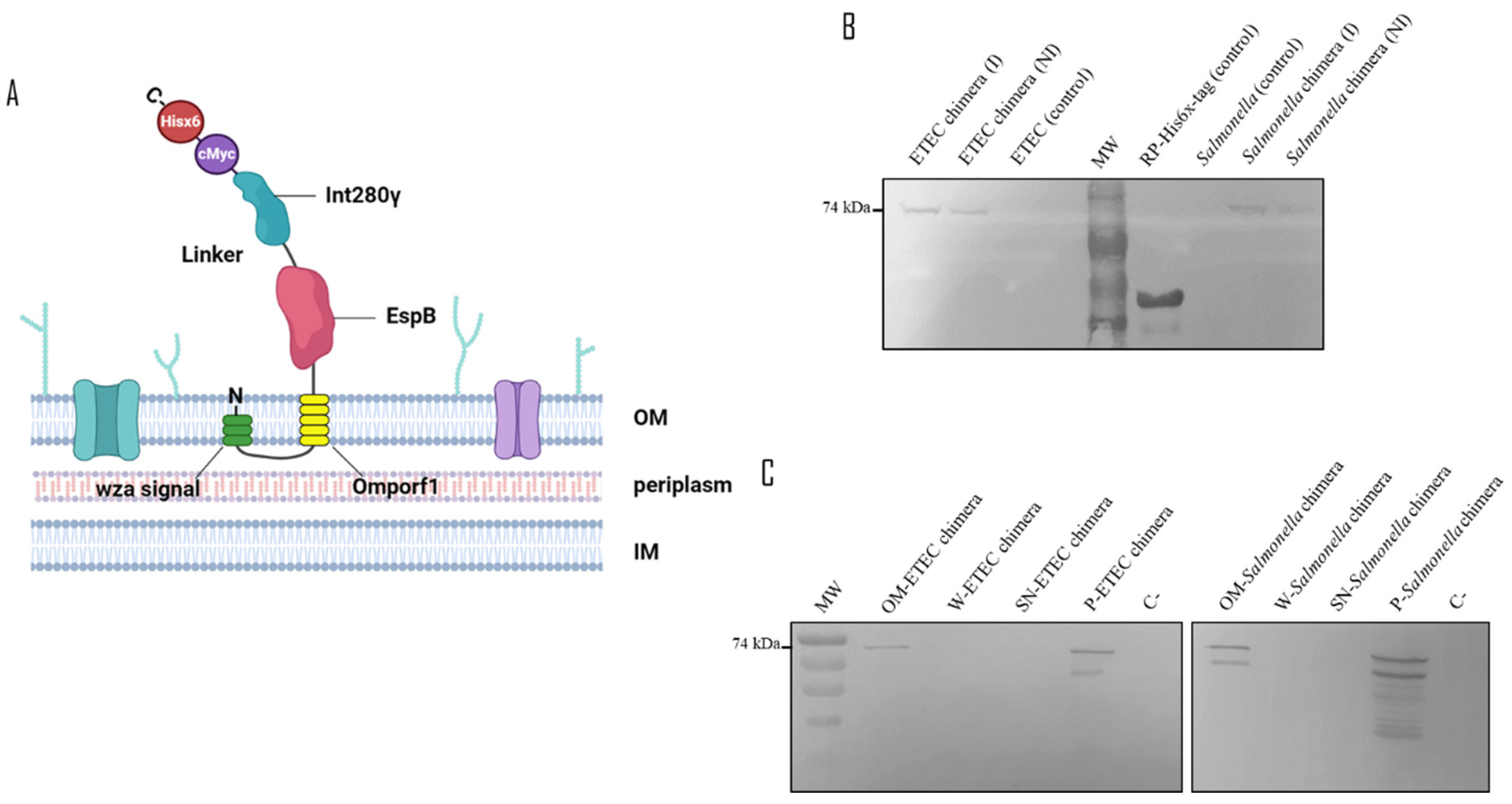

3.4. Immune Response of Mice and Guinea Pigs

The following step was to assess the immunogenicity and efficacy of the new vaccine strategy against bovine diarrhea complex —which includes the recombinant EHEC O157:H7 antigen—, by performing immune response assays in mice and guinea pigs (

Figure 3).

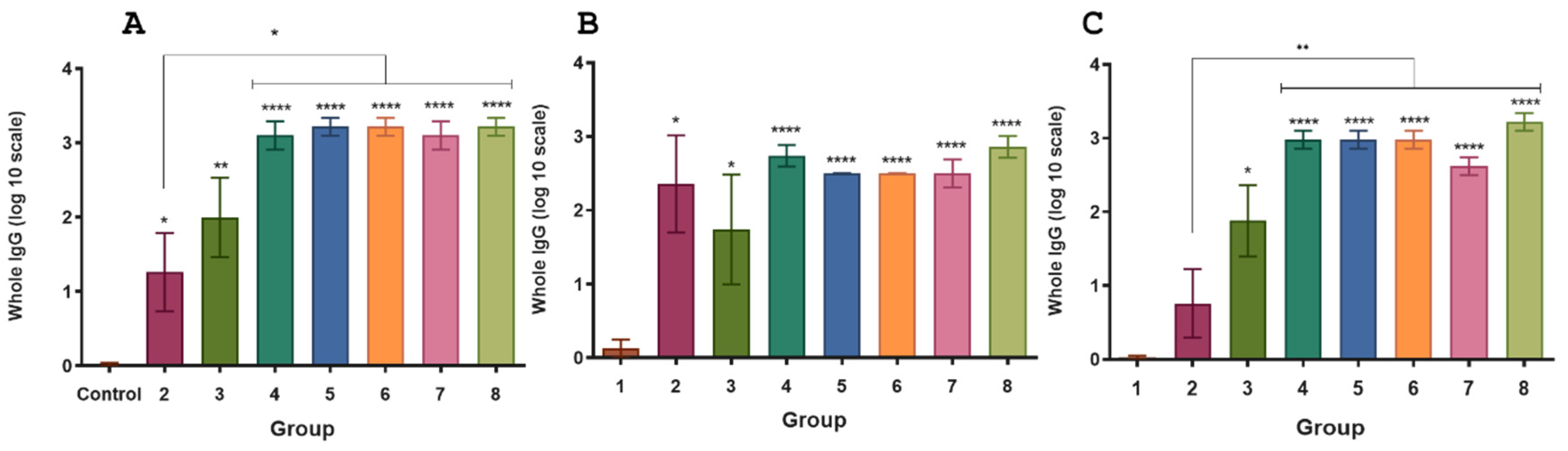

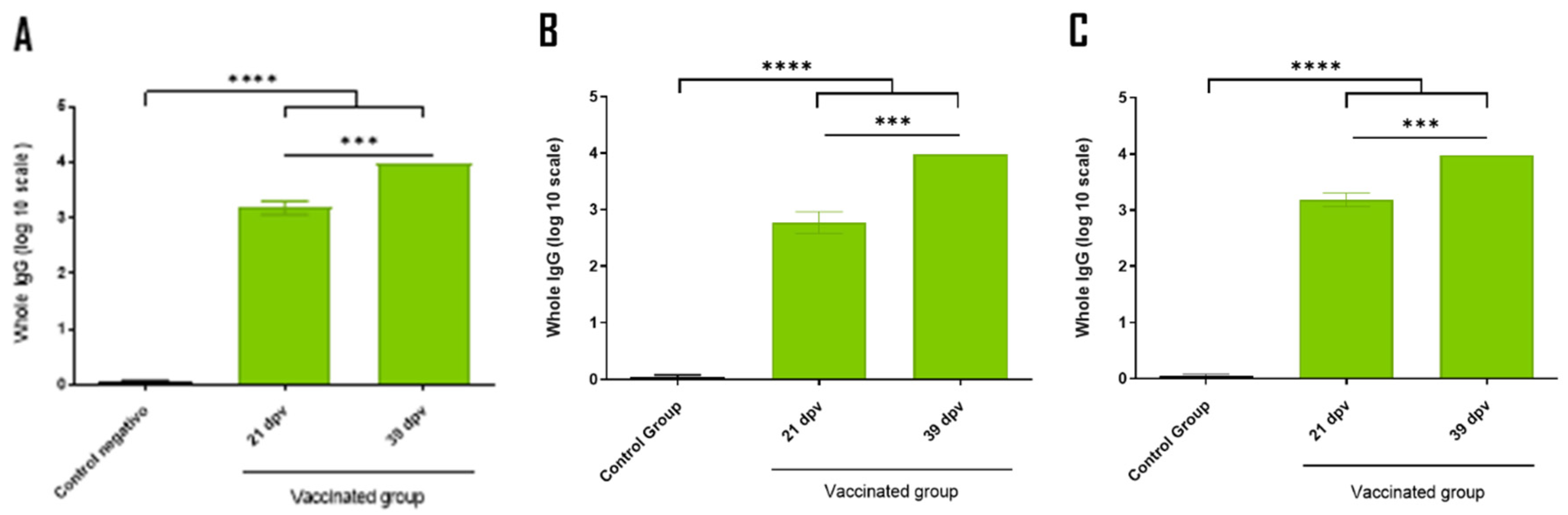

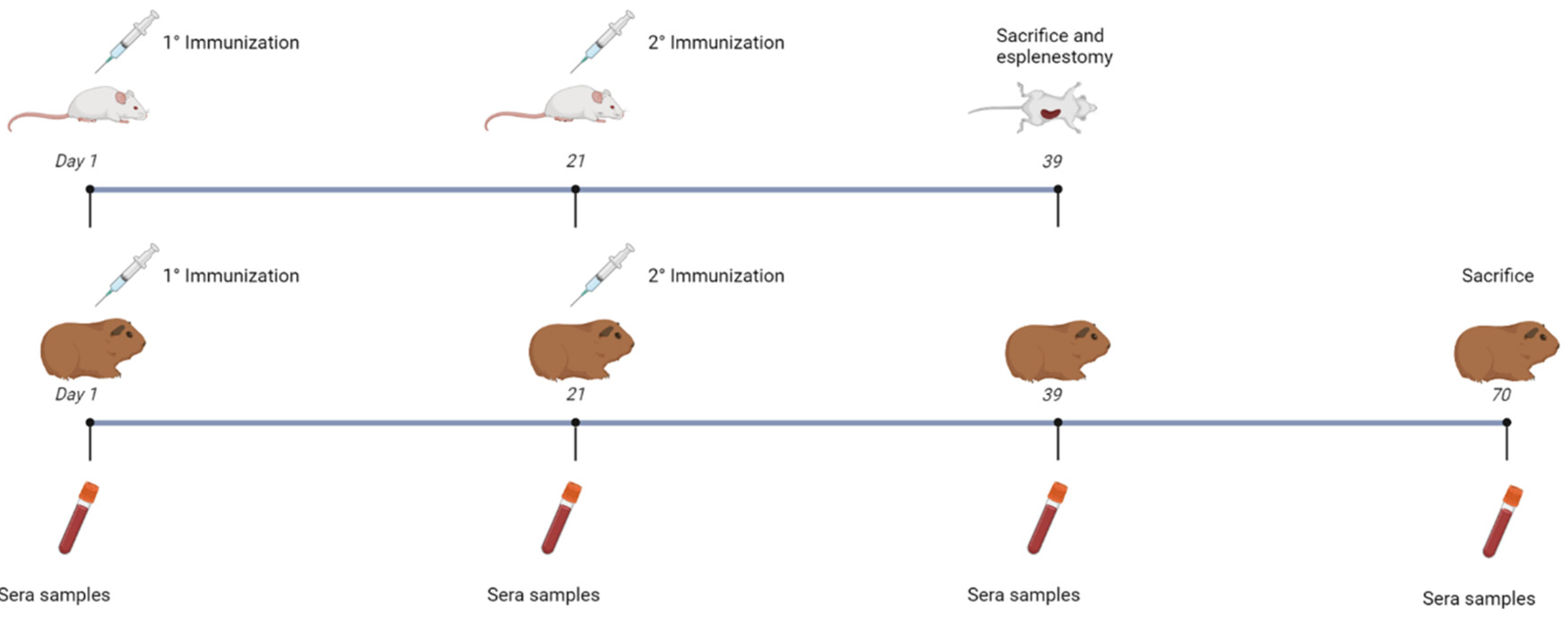

Immunization results at 39 days post-vaccination (dpv) in mice indicated that the combination of the individual antigens (group 2) and the antigen corresponding to the chimeric fusion (groups 3 and 4) led to a higher immune response compared to the control group (group 1) (

Figure 4A). Notably, comparable molecular amounts of the individual antigen (group 2) and the chimera (group 3) produced similar immune responses. Furthermore, the immune response generated by 10 µg of the recombinant chimera (group 4) was equivalent to that produced by the groups containing ETEC and/or

Salmonella dublin expressing the recombinant chimera in the membrane (groups from 5 to 8). No significant differences were observed in the immune response between the mice inoculated with one or two of the bacteria expressing the recombinant chimera in the membrane (groups 5 and 6 vs. 7 and 8) (

Figure 4A). The inclusion of 10

7 focus-forming units (FFU) of each BCoV and BRoVA into the vaccine mixture did not impair the immune response against the chimeric protein (group 8 vs. 7). Both groups of mice inoculated with either the recombinant soluble chimera or the chimera expressed in bacterial membranes developed a specific immune response against Int280γ and EspB (

Figure 4B,C). No significant differences were observed in the immune response between vaccination at 21 dpv and booster at 39 dpv in groups 4 to 8. This suggests that a single dose may be sufficient to elicit an effective immune response (

Supplementary Figure S4).

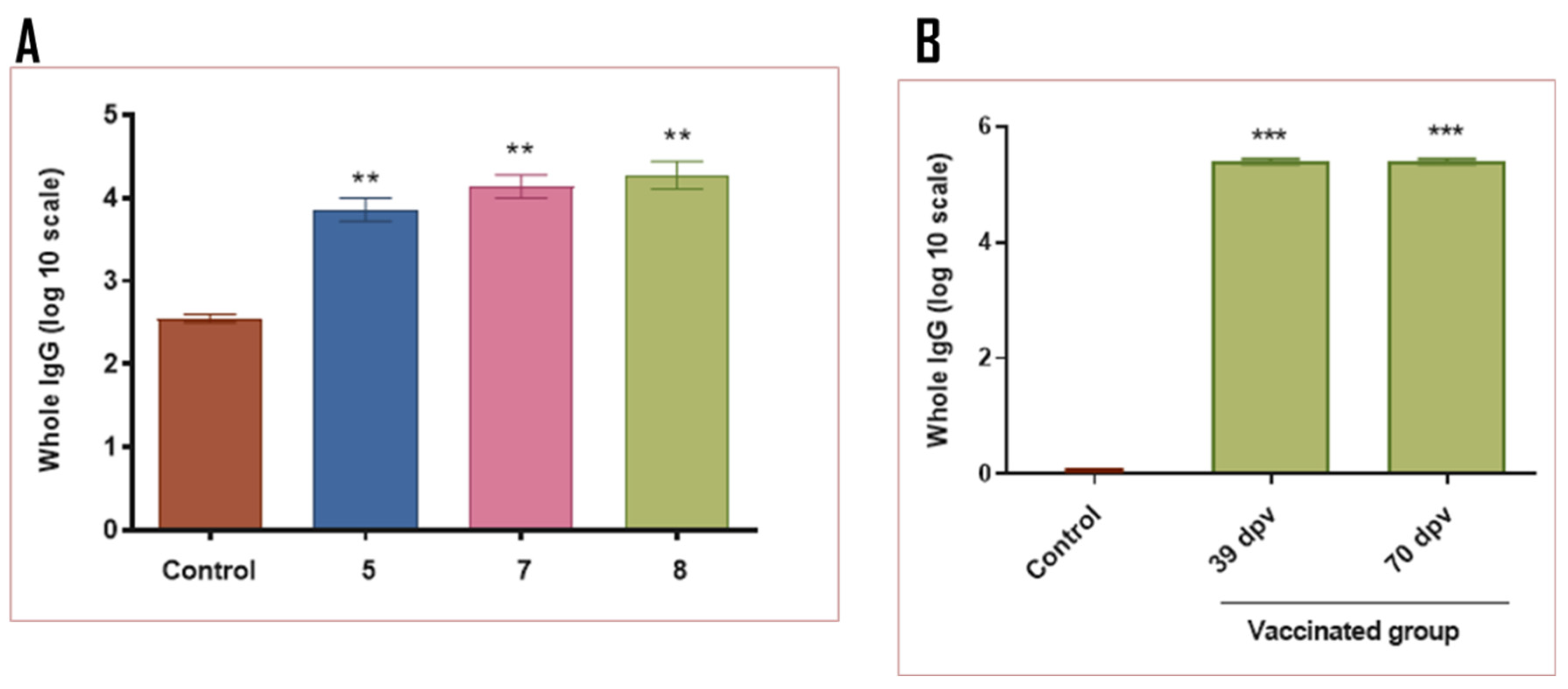

In a similar manner to the results obtained in mice (group 8), the complete vaccination strategy in guinea pigs led to an elevated immune response against the chimera, Int280γ and EspB when compared to the control group (

Figure 5). Interestingly, the specific immune response against Int280γ and EspB did not exhibit significant differences, suggesting both antigens demonstrated comparable immunogenicity (

Figure 5B,C).

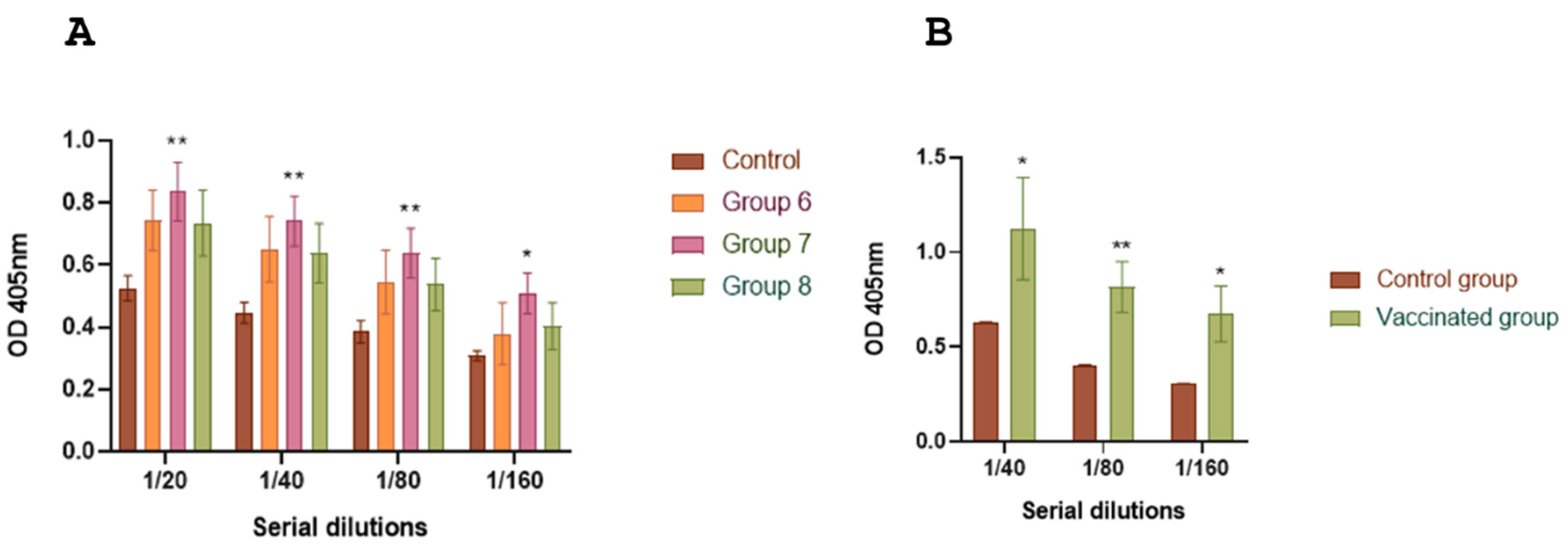

3.5. Evaluation of Immune Response Against Chimera-Carrying Bacteria

To integrate the chimera antigen in an existing vaccine formulation, such as the one for bovine neonatal diarrhea, we evaluated the immune responses induced by bacterial carriers and viral particles in mice and guinea pigs. ELISA analysis of total specific IgG levels against ETEC fimbriae (groups 5, 7 and 8) and

Salmonella lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (groups 6, 7 and 8) in mice indicated the triggering of immune responses against both fimbriae and LPS (

Figures 6A and 7A). Guinea pigs showed similar results when inoculated with the complete vaccine formulation (

Figures 6B and 7B). In contrast to mice, the basal response to fimbriae in guinea pigs was considerably lower to that of the group inoculated with chimera-carrying bacteria (control groups,

Figure 6A,B).

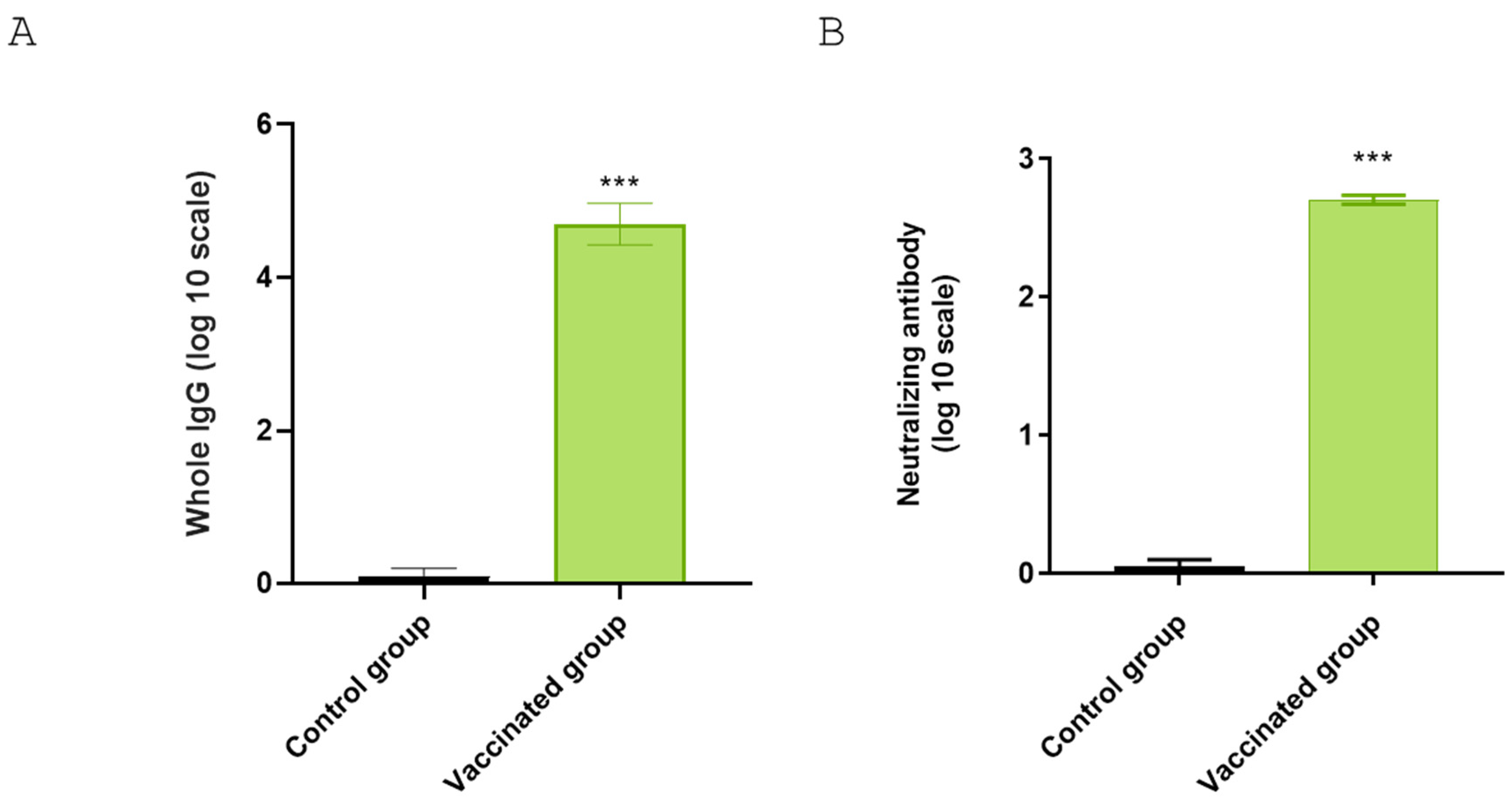

3.6. Antibody Titers Against BRoVA UK and BCoV Mebus

Guinea pigs that received the complete vaccine showed significantly higher titers against BCoV Mebus compared to the control group (

Figure 8A). To further characterize the neutralization capability of guinea pig sera against Rotavirus A (RVA), we performed a virus neutralization assay using BRoVA UK strain. The guinea pig group receiving the complete vaccination formulation showed significantly higher virus neutralization antibody titers (512) than the control group (

Figure 8B).

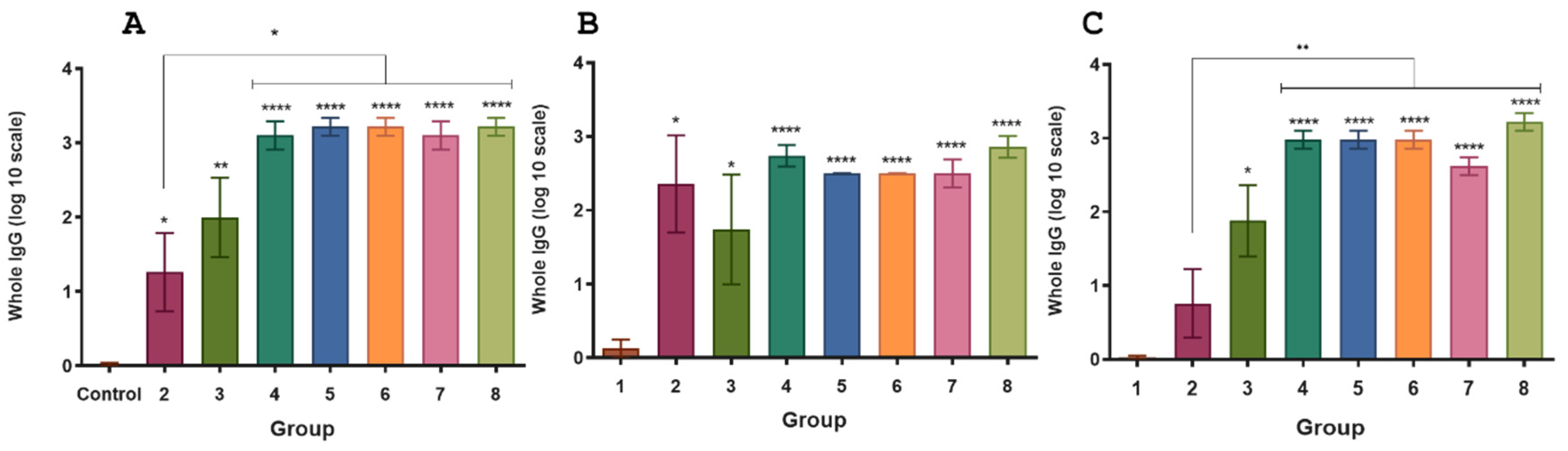

3.7. Antigen-Specific Immune Response Profiles Across Vaccination Groups

The highest levels of specific IgG1 were observed in mice vaccine groups inoculated with 2 µg of the chimera (group 3), 10 µg of the chimera (group 4), 1.10

8 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 and

Salmonella dublin, expressing the chimera (group 7) (

Figure 9A). The levels detected in Group inoculated with 1.10

8 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 and

Salmonella dublin, expressing the chimera, plus BRoVA and BCoVB (8) were slightly lower than those observed in the other treatment groups (p<0.0001,

Figure 9A).

For IgG2a levels, the highest were found in Groups 4, 7, and 8 (

Figure 9B). However, groups 2 (1 µg of EspB and 1 µg of Int280γ) and group 3 also showed significantly higher levels compared to the control group (

Figure 9B).

Levels of IFN-γ (Th1 marker), IL-5 (Th2 marker), and IL-17 (Th17 marker) were assessed through splenocyte stimulation assays in mice immunized with the chimeric protein (

Figure 10A, B and C). All treatments (Groups 2, 3, 4, 7 and 8) demonstrated the capacity to induce a mixed Th1, Th2, and Th17 profile. Groups 7 and 8 had lower levels of IFN-γ and IL-5 IL-17, while showing higher levels of IL-17; however, the increase was only significant for Group 7 compared to Group 3 (p<0.05,

Figure 10A,B). These results indicate that the mucosal immunization schemes tested elicited a robust antigen-specific humoral immune response, both when administered as recombinant antigens and as carrier-expressed formulations.

4. Discussion

Proteins from the T3SS have been studied as potential components for rational design of vaccines capable of reducing fecal shedding of EHEC O157:H7 in cattle [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Prior research has demonstrated that intramuscular vaccination with recombinant EspB and Int280γ antigens generates a specific humoral immune response in cattle serum [

8,

28,

29] and induced a specific mucosal secretory immune response via oral vaccination in mice [

30]. Additionally, these specific antibodies could inhibit epithelial cell lines adhesion and reduce T3SS-dependent red blood cell lysis, colonization, and shedding in bovines [

19] and mice orally challenged with EHEC O157:H7 [

30]. These findings support the potential of an intramuscular vaccine containing these antigens, although the vaccine formulation must be optimized to enhance protection and commercial viability for cattle vaccination

In this study, we first designed a membrane-anchoring chimeric protein combining the EspB and Int280γ antigens and evaluated its expression in two pathogens responsible for NCD, Salmonella dublin and ETEC. The chimera was successfully expressed in the membrane. This result confirmed the correct translation of the coding sequence for Wza-Omporf1 and His(6X)-cMyc tag in the N- and C-terminal region, respectively. Expression analysis showed that non-induced bacteria showed basal expression of the chimera, whereas both induced bacterial strains expressed the chimera at similarly higher levels. The chimera proved stable under inactivation and storage conditions.

The IgG responses to fimbriae and LPS in sera indicate preservation of bacterial structures, a crucial consideration for future scaling up and licensing efforts. Immune responses in sera from the two experimental models inoculated with individual or combined recombinant bacteria showed high titers of chimera-specific antibodies. These result supports proper expression, anchorage, and membrane exposure, as well as the effective preservation of the vaccine antigen, even after inactivation and subsequent storage.

In the immunization assays, no significant differences were observed between the use of each recombinant bacterium individually or in combination, suggesting saturation of the immune response. With no apparent synergistic effect, a vaccine formulation containing either chimera -expressing recombinant ETEC or Salmonella alone would be sufficient.

Regarding chimera expression in the membrane, 1.108 CFU bacteria expressing the chimera were immunologically equivalent to 10 µg of the recombinant chimeric antigen. The immune response observed at 21 and 39 dpv was similar regardless the dose in both models, suggesting that a single vaccination may suffice in a potential vaccination strategy. Furthermore, the individual evaluations of the EspB and Int280ϒ antigens in both models elicited comparable immune responses, underscoring their importance in chimera construction and their robust immunogenic properties.

Furthermore, the analysis of the immune response of BCoV and BRoVA showed that these viral particles elicited strong specific response without interference with the chimera response. Similarly, LPS and fimbriae antigens also elicited increased immune responses in both models. However, in both instances, animals might have pre-existing specific antibodies against these bacterial antigens, or the responses may involve cross-reactivity with similar pathogens, given the basal response in controls.

Finally, the elevated levels of IgG1 and IgG2a observed in the vaccine groups, alongside the induction of markers associated with Th1 (IFN-γ), Th2 (IL-5), and Th17 (IL-17) responses, suggest that the chimeric protein can elicit a mixed immune response. This combination of humoral (IgG1 and IgG2a) and cellular (IFN-γ, IL-5, IL-17) responses indicates that a vaccine containing the EspB and Int280γ, as recombinant antigens alone, fused or anchored to the bacterial membrane, may offer broad and effective protection against the pathogen.

5. Conclusions

The membrane-anchoring chimera generated specific antibodies against the fused and individual proteins of EHEC O157:H7, with no significant differences in immune response between individual proteins. Expressing this chimera in Salmonella and ETEC enhances the potential of the NCD vaccine to protect calves against neonatal diarrhea. This strategy could also benefit human health by helping to prevent HUS without increasing production costs or altering standard cattle vaccination schedule.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.V., A.A.C., A.W., M.L.; methodology, D.A.V., D.H., A.W., M.L.; formal analysis, H.R., E.Z., M.C.C: M.L. Investigation, D.A.V., E.Z., D.B., M.L.; resources, H.R., D.H., A.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R., D.A.V., D.H., A.A.C., M.L.; supervision, D.A.V., D.H., A.A.C., A.W., M.L.; project administration, D.A.V., A.A.C., A.W., M.L.: funding acquisition, D.A.V, A.A.C., A.W., M.L.

Funding

The Project was supported by PICT Start Up -2016-0017, and FONTAR ANR FT 30000, both grants from Argentina National Science and Technology Agency, Argentina and PI113 from National Institute of Agrucultural Research (INTA), Argentina-.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The animal study protocol was Institutional Committee for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals CICUAE INTA CICVyA approved the study (CICUAE 09/2023).

Acknowledgments

To Julia Sabio Y García for reviewing the manuscript).

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Palermo, M.S.; Exeni, R.A.; Fernández, G.C. Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: Pathogenesis and Update of Interventions. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2009, 7, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nataro, J.P.; Kaper, J.B. Diarrheagenic Escherichia Coli. Clin Microbiol Rev 1998, 11, 142–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas, M.; Chinen, I.; Miliwebsky, E.; Masana, M. Risk Factors for Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli-Associated Human Diseases. Microbiol Spectr 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, S.W.; Low, J.C.; Besser, T.E.; Mahajan, A.; Gunn, G.J.; Pearce, M.C.; Mckendrick, I.J.; Smith, D.G.E.; Gally, D.L. Lymphoid Follicle-Dense Mucosa at the Terminal Rectum Is the Principal Site of Colonization of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia Coli O157:H7 in the Bovine Host. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midgley, J.; Desmarchelier, P. Pre-Slaughter Handling of Cattle and Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli (STEC). Lett Appl Microbiol 2001, 32, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, L.; Reeve, R.; Gally, D.L.; Low, J.C.; Woolhouse, M.E.J.; McAteer, S.P.; Locking, M.E.; Chase-Topping, M.E.; Haydon, D.T.; Allison, L.J.; et al. Predicting the Public Health Benefit of Vaccinating Cattle against Escherichia coli O157. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 16265–16270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretschneider, G.; Berberov, E.M.; Moxley, R.A. Isotype-Specific Antibody Responses against Escherichia coli O157:H7 Locus of Enterocyte Effacement Proteins in Adult Beef Cattle Following Experimental Infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2007, 118, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovitz, B.C.; Larzábal, M.; Vilte, D.A.; Cataldi, A.; Mercado, E.C. The Intranasal Vaccination of Pregnant Dams with Intimin and EspB Confers Protection in Neonatal Mice from Escherichia coli (EHEC) O157:H7 Infection. Vaccine 2016, 34, 2793–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldi, A.; Yevsa, T.; Vilte, D. a; Schulze, K.; Castro-Parodi, M.; Larzábal, M.; Ibarra, C.; Mercado, E.C.; Guzmán, C. A Efficient Immune Responses against Intimin and EspB of Enterohaemorragic Escherichia coli after Intranasal Vaccination Using the TLR2/6 Agonist MALP-2 as Adjuvant. Vaccine 2008, 26, 5662–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiuk, S.; Asper, D.; Rogan, D.; Mutwiri, G.; Potter, A. Subcutaneous and Intranasal Immunization with Type III Secreted Proteins Can Prevent Colonization and Shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Mice. Microb Pathog 2008, 45, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, U.B.; Haller, C.; Haidinger, W.; Atrasheuskaya, A.; Bukin, E.; Lubitz, W.; Ignatyev, G. Bacterial Ghosts as an Oral Vaccine: A Single Dose of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Bacterial Ghosts Protects Mice against Lethal Challenge. Infect Immun 2005, 73, 4810–4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannino, F.; Herrmann, C.K.; Roset, M.S.; Briones, G. Development of a Dual Vaccine for Prevention of Brucella Abortus Infection and Escherichia coli O157:H7 Intestinal Colonization. Vaccine 2015, 33, 2248–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingermann, M.; Avila, L.; De Marco, M.B.; Vázquez, L.; Di Biase, D.N.; Müller, A.V.; Lescano, M.; Dokmetjian, J.C.; Fernández Castillo, S.; Pérez Quiñoy, J.L. OMV-Based Vaccine Formulations against Shiga Toxin Producing Escherichia coli Strains Are Both Protective in Mice and Immunogenic in Calves. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018, 14, 2208–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, D.A.; Del Canto, F.; Salazar, J.C.; Céspedes, S.; Cádiz, L.; Arenas-Salinas, M.; Reyes, J.; Oñate, Á.; Vidal, R.M. Immunization of Mice with Chimeric Antigens Displaying Selected Epitopes Confers Protection against Intestinal Colonization and Renal Damage Caused by Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, D.A.; Garcia-Betancourt, R.; Vidal, R.M.; Velasco, J.; Palacios, P.A.; Schneider, D.; Vega, C.; Gómez, L.; Montecinos, H.; Soto-Shara, R.; et al. A Chimeric Protein-Based Vaccine Elicits a Strong IgG Antibody Response and Confers Partial Protection against Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli in Mice. Front Immunol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konadu, E.; Donohue-Rolfe, A.; Calderwood, S.B.; Pozsgay, V.; Shiloach, J.; Robbins, J.B.; Szu, S.C. Syntheses and Immunologic Properties of Escherichia coli O157 O-Specific Polysaccharide and Shiga Toxin 1 B Subunit Conjugates in Mice. Infect Immun 1999, 67, 6191–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, M.; Roch, F.F.; Conrady, B. Prevalence of Worldwide Neonatal Calf Diarrhoea Caused by Bovine Rotavirus in Combination with Bovine Coronavirus, Escherichia coli K99 and Cryptosporidium Spp.: A Meta-Analysis. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Novel Bacterial Surface Display Systems Based on Outer Membrane Anchoring Elements from the Marine Bacterium Vibrio Anguillarum. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008, 74, 4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilte, D.A.; Larzábal, M.; Garbaccio, S.; Gammella, M.; Rabinovitz, B.C.; Elizondo, A.M.; Cantet, R.J.C.; Delgado, F.; Meikle, V.; Cataldi, A.; et al. Reduced Faecal Shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Cattle Following Systemic Vaccination with γ-Intimin C₂₈₀ and EspB Proteins. Vaccine 2011, 29, 3962–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tô, T.L.; Ward, L.A.; Yuan, L.; Saif, L.J. Serum and Intestinal Isotype Antibody Responses and Correlates of Protective Immunity to Human Rotavirus in a Gnotobiotic Pig Model of Disease. J Gen Virol 1998, 79 ( Pt 11) Pt 11, 2661–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A Simple Method of Estimating Fifty per Cent Endpoints. Am J Epidemiol 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, C.; Bok, M.; Chacana, P.; Saif, L.; Fernandez, F.; Parreño, V. Egg Yolk IgY: Protection against Rotavirus Induced Diarrhea and Modulatory Effect on the Systemic and Mucosal Antibody Responses in Newborn Calves. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2011, 142, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martorelli, L.; Garimano, N.; Fiorentino, G.A.; Vilte, D.A.; Garbaccio, S.G.; Barth, S.A.; Menge, C.; Ibarra, C.; Palermo, M.S.; Cataldi, A. Efficacy of a Recombinant Intimin, EspB and Shiga Toxin 2B Vaccine in Calves Experimentally Challenged with Escherichia coli O157:H7. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3949–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilte, D.A.; Larzábal, M.; Garbaccio, S.; Gammella, M.; Rabinovitz, B.C.; Elizondo, A.M.; Cantet, R.J.C.; Delgado, F.; Meikle, V.; Cataldi, A.; et al. Reduced Faecal Shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Cattle Following Systemic Vaccination with γ-Intimin C280 and EspB Proteins. Vaccine 2011, 29, 3962–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.R. Vaccination of Cattle against Escherichia Coli O157 : H7. 2014, 1–11. Correspondence. [CrossRef]

- Potter, A.A.; Klashinsky, S.; Li, Y.; Frey, E.; Townsend, H.; Rogan, D.; Erickson, G.; Hinkley, S.; Klopfenstein, T.; Moxley, R.A.; et al. Decreased Shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by Cattle Following Vaccination with Type III Secreted Proteins. Vaccine 2004, 22, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeilly, T.N.; Mitchell, M.C.; Rosser, T.; McAteer, S.; Low, J.C.; Smith, D.G.E.; Huntley, J.F.; Mahajan, A.; Gally, D.L. Immunization of Cattle with a Combination of Purified Intimin-531, EspA and Tir Significantly Reduces Shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Following Oral Challenge. Vaccine 2010, 28, 1422–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilte, D.A.; Larzábal, M.; Cataldi, Á.A.; Mercado, E.C. Bovine Colostrum Contains Immunoglobulin G Antibodies against Intimin, EspA, and EspB and Inhibits Hemolytic Activity Mediated by the Type Three Secretion System of Attaching and Effacing Escherichia coli. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2008, 15, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovitz, B.; Vilte, D.; Larzábal, M.; Abdala, A.; Galarza, R.; Zotta, E.; Ibarra, C.; Mercado, E.; Cataldi, A. Physiopathological Effects of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Inoculation in Weaned Calves Fed with Colostrum Containing Antibodies to EspB and Intimin. Vaccine 2014, 32, 3823–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.L.; Larzábal, M.; Song, H.; Cheng, T.; Wang, Y.; Smith, L.Y.; Cataldi, A.A.; Ow, D.W. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 Antigens Produced in Transgenic Lettuce Effective as an Oral Vaccine in Mice. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2023, 136, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A) Schematic representation of the chimeric protein. The chimera comprises a Wza-Omporf1 anchor sequence that inserts itself into the outer membrane (OM) at the N-terminal end and orients the rest of the EspB-linker-Int280 antigenic fusion to the extracellular milieu. The C-terminal region ends with the epitopes for c-Myc and His6x-tags. The approximate molecular weight of the chimera is 74 kDa. Detection of the recombinant chimeric protein expression and outer membrane localization in recombinant ETEC and Salmonella. B) ETEC and Salmonella transformed with pTrcHis2B-BLI280 were induced (I), or not (non-induced: NI), with IPTG for recombinant chimera expression. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE. Wild-type ETEC and Salmonella strains were used as controls not expressing the chimera and recombinant Int280ϒ-Hisx6 (RP) purified protein was used as primary antibody control. C) ETEC and Salmonella transformed with pTrcHis2B-BLI280 were induced with IPTG to express the recombinant chimera. Samples of different fractions from the membrane purification process of ETEC and Salmonella were separated by SDS-PAGE. References: outer membrane (OM), pellet washings (W), pellet supernatant (SN), total bacterial pellet (P) and total bacterial culture supernatant (C). Chimera detection was performed using a mouse-specific anti Hisx6-tag primary antibody and an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse as a secondary antibody, in both western blot assays.

Figure 1.

A) Schematic representation of the chimeric protein. The chimera comprises a Wza-Omporf1 anchor sequence that inserts itself into the outer membrane (OM) at the N-terminal end and orients the rest of the EspB-linker-Int280 antigenic fusion to the extracellular milieu. The C-terminal region ends with the epitopes for c-Myc and His6x-tags. The approximate molecular weight of the chimera is 74 kDa. Detection of the recombinant chimeric protein expression and outer membrane localization in recombinant ETEC and Salmonella. B) ETEC and Salmonella transformed with pTrcHis2B-BLI280 were induced (I), or not (non-induced: NI), with IPTG for recombinant chimera expression. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE. Wild-type ETEC and Salmonella strains were used as controls not expressing the chimera and recombinant Int280ϒ-Hisx6 (RP) purified protein was used as primary antibody control. C) ETEC and Salmonella transformed with pTrcHis2B-BLI280 were induced with IPTG to express the recombinant chimera. Samples of different fractions from the membrane purification process of ETEC and Salmonella were separated by SDS-PAGE. References: outer membrane (OM), pellet washings (W), pellet supernatant (SN), total bacterial pellet (P) and total bacterial culture supernatant (C). Chimera detection was performed using a mouse-specific anti Hisx6-tag primary antibody and an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse as a secondary antibody, in both western blot assays.

Figure 2.

Detection of recombinant the chimeric protein in inactivated recombinant ETEC and Salmonella. Induced recombinant ETEC and Salmonella were inactivated with 0.2 % formalin incubated for 72 h at 4 °C. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE. Chimera detection was performed using a mouse-specific anti Hisx6-tag primary antibody and an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse as a secondary antibody. The abbreviations correspond to: Uninduced bacteria (NI), induced bacteria (I) and induced and inactivated bacteria (II).

Figure 2.

Detection of recombinant the chimeric protein in inactivated recombinant ETEC and Salmonella. Induced recombinant ETEC and Salmonella were inactivated with 0.2 % formalin incubated for 72 h at 4 °C. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE. Chimera detection was performed using a mouse-specific anti Hisx6-tag primary antibody and an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse as a secondary antibody. The abbreviations correspond to: Uninduced bacteria (NI), induced bacteria (I) and induced and inactivated bacteria (II).

Figure 3.

Scheme of immunization assays of mice and guinea pigs. Groups of mice and guinea pigs were immunized with two doses of vaccine preparations in an interval of 21 days via subcutaneous injection. Sera samples were collected from both animal models at days 1, 21 and 39. On day 39, the mice were sacrificed, and splenectomy was performed. An additional sera sample collection was performed for the guinea pigs on the 70th day before performing euthanasia of the animals. The mice were divided into seven groups of five animals each; one group of four animals was used as a control. The different groups were numbered from 1 to 8 and inoculated with the following antigens combinations: Group 1: PBS Control, Group 2: 1 µg of EspB and 1 µg of Int280ϒ, Group 3: 2 µg of the chimera, Group 4: 10 µg of the chimera, Group 5: ETEC expressing the chimera, Group 6: Salmonella expressing the chimera, Group 7: Both recombinant bacteria expressing the chimera and Group 8: Both recombinant bacteria expressing the chimera plus BCoV and BRoVA viral particles. The guinea pigs were divided into two groups of five animals each. One group was inoculated with a vaccine containing both recombinant bacteria expressing the chimera plus BCoV and BRoVA viral particles. The other group was vaccinated with PBS (Control.

Figure 3.

Scheme of immunization assays of mice and guinea pigs. Groups of mice and guinea pigs were immunized with two doses of vaccine preparations in an interval of 21 days via subcutaneous injection. Sera samples were collected from both animal models at days 1, 21 and 39. On day 39, the mice were sacrificed, and splenectomy was performed. An additional sera sample collection was performed for the guinea pigs on the 70th day before performing euthanasia of the animals. The mice were divided into seven groups of five animals each; one group of four animals was used as a control. The different groups were numbered from 1 to 8 and inoculated with the following antigens combinations: Group 1: PBS Control, Group 2: 1 µg of EspB and 1 µg of Int280ϒ, Group 3: 2 µg of the chimera, Group 4: 10 µg of the chimera, Group 5: ETEC expressing the chimera, Group 6: Salmonella expressing the chimera, Group 7: Both recombinant bacteria expressing the chimera and Group 8: Both recombinant bacteria expressing the chimera plus BCoV and BRoVA viral particles. The guinea pigs were divided into two groups of five animals each. One group was inoculated with a vaccine containing both recombinant bacteria expressing the chimera plus BCoV and BRoVA viral particles. The other group was vaccinated with PBS (Control.

Figure 4.

Specific IgG responses at 39 dpv in inoculated mice. ELISA plates were coated with purified the recombinant chimera (A), EspB (B) and Int280ϒ (C) respectively. Specific antibodies response to the chimera, Int280ϒ and EspB were measured for each group using indirect ELISA and sera samples (39 dpv) from mice. Group 1: 150 µl of PBS (Control), Group 2: 1 µg of EspB and 1 µg of Int280γ, Group 3: 2 µg of the chimera, Group 4: 10 µg of the chimera, Group 5: 1.108 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 expressing the chimera, Group 6: 1.108 inactivated CFU of Salmonella dublin expressing the chimera, Group 7: 1.108 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 and Salmonella dublin, both expressing the chimera and Group 8: 1.108 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 and Salmonella dublin, both expressing the chimera, plus 1.107 FFU BRoVA UK and BCoVB Mebus. Goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used as a secondary antibody. ABTS was used as substrate and the reaction was measured at OD450. The antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the end-point dilution resulting in an OD405 above the cut-off value. The cut-off value was calculated as the average plus two times the standard deviation of the optical densities of the samples measured on day 0. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test, p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 4.

Specific IgG responses at 39 dpv in inoculated mice. ELISA plates were coated with purified the recombinant chimera (A), EspB (B) and Int280ϒ (C) respectively. Specific antibodies response to the chimera, Int280ϒ and EspB were measured for each group using indirect ELISA and sera samples (39 dpv) from mice. Group 1: 150 µl of PBS (Control), Group 2: 1 µg of EspB and 1 µg of Int280γ, Group 3: 2 µg of the chimera, Group 4: 10 µg of the chimera, Group 5: 1.108 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 expressing the chimera, Group 6: 1.108 inactivated CFU of Salmonella dublin expressing the chimera, Group 7: 1.108 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 and Salmonella dublin, both expressing the chimera and Group 8: 1.108 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 and Salmonella dublin, both expressing the chimera, plus 1.107 FFU BRoVA UK and BCoVB Mebus. Goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used as a secondary antibody. ABTS was used as substrate and the reaction was measured at OD450. The antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the end-point dilution resulting in an OD405 above the cut-off value. The cut-off value was calculated as the average plus two times the standard deviation of the optical densities of the samples measured on day 0. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test, p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 5.

Specific IgG responses in inoculated guinea pigs. ELISA plates were coated with the purified recombinant chimera (A), EspB (B) and Int280ϒ (C), respectively. Specific antibodies response to the chimera, Int280ϒ and EspB were measured for each group using indirect ELISA and sera samples from guinea pigs. Goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used as a secondary antibody. ABTS was used as substrate and the reaction was measured at OD450. The antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the end-point dilution resulting in an OD405 above the cut-off value. The cut-off value was calculated as the average plus two times the standard deviation of the optical densities of the samples measured on day 0. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test p < 0.0002 (***) and p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 5.

Specific IgG responses in inoculated guinea pigs. ELISA plates were coated with the purified recombinant chimera (A), EspB (B) and Int280ϒ (C), respectively. Specific antibodies response to the chimera, Int280ϒ and EspB were measured for each group using indirect ELISA and sera samples from guinea pigs. Goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used as a secondary antibody. ABTS was used as substrate and the reaction was measured at OD450. The antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the end-point dilution resulting in an OD405 above the cut-off value. The cut-off value was calculated as the average plus two times the standard deviation of the optical densities of the samples measured on day 0. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test p < 0.0002 (***) and p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 6.

AB: IgG response against fimbria in sera of mice and guinea pigs inoculated with ETEC. ELISA plates were coated with purified fimbriae. Antibody response to fimbriae was measured for each group using indirect ELISA and sera samples from mice (A) and guinea pigs (B). Goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used as a secondary antibody. ABTS was used as a substrate and the reaction was measured at OD450. The antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the end-point dilution resulting in an OD405 above the cut-off value. The cut-off value was calculated as the average plus two times the standard deviation of the optical densities of the samples measured on day 0. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test, p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.001 (***).

Figure 6.

AB: IgG response against fimbria in sera of mice and guinea pigs inoculated with ETEC. ELISA plates were coated with purified fimbriae. Antibody response to fimbriae was measured for each group using indirect ELISA and sera samples from mice (A) and guinea pigs (B). Goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used as a secondary antibody. ABTS was used as a substrate and the reaction was measured at OD450. The antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the end-point dilution resulting in an OD405 above the cut-off value. The cut-off value was calculated as the average plus two times the standard deviation of the optical densities of the samples measured on day 0. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test, p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.001 (***).

Figure 7.

IgG response against LPS in sera of inoculated mice and guinea pigs with Salmonella. ELISA plates were coated with purified LPS. Antibodies response to LPS were measured for each group using indirect ELISA and sera samples from of mice (A) and guinea pigs (B). Goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used as a secondary antibody. ABTS was used as a substrate and the reaction was measured at OD450. The antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the end-point dilution resulting in an OD405 above the cut-off value. The cut-off value was calculated as the average plus two times the standard deviation of the optical densities of the samples measured on day 0. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test, p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**).

Figure 7.

IgG response against LPS in sera of inoculated mice and guinea pigs with Salmonella. ELISA plates were coated with purified LPS. Antibodies response to LPS were measured for each group using indirect ELISA and sera samples from of mice (A) and guinea pigs (B). Goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used as a secondary antibody. ABTS was used as a substrate and the reaction was measured at OD450. The antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the end-point dilution resulting in an OD405 above the cut-off value. The cut-off value was calculated as the average plus two times the standard deviation of the optical densities of the samples measured on day 0. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test, p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**).

Figure 8.

IgG response against BCoV and neutralizing antibodies against BRoVA in sera of vaccinated guinea pigs. (A) ELISA plates were coated with hyperimmune anti-BCoV serum. Clarified supernatants from HRT-18 cultures infected with standardized titer of coronavirus or supernatants from uninfected cells (control) was added into the corresponding wells. Commercial polyclonal anti-mouse or anti-guinea pig antibodies conjugated to peroxidase were added as appropriate. The plates were read using an ELISA reader at 405 nm. (B) Mixtures of serial dilutions of guinea pig serum were incubated with equal amounts of BRoVA. The mixture was incubated with a cell suspension to determine neutralization. The test was developed using a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-RV polyclonal antiserum derived from a colostrum-deprived calf by hyperimmunization. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test, p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.001 (***).

Figure 8.

IgG response against BCoV and neutralizing antibodies against BRoVA in sera of vaccinated guinea pigs. (A) ELISA plates were coated with hyperimmune anti-BCoV serum. Clarified supernatants from HRT-18 cultures infected with standardized titer of coronavirus or supernatants from uninfected cells (control) was added into the corresponding wells. Commercial polyclonal anti-mouse or anti-guinea pig antibodies conjugated to peroxidase were added as appropriate. The plates were read using an ELISA reader at 405 nm. (B) Mixtures of serial dilutions of guinea pig serum were incubated with equal amounts of BRoVA. The mixture was incubated with a cell suspension to determine neutralization. The test was developed using a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-RV polyclonal antiserum derived from a colostrum-deprived calf by hyperimmunization. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test, p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.001 (***).

Figure 9.

Mice antibody titers induced by recombinant chimera. Total titers of IgG1 (A) and IgG2a (B). Groups are formed as in

Figure 4 Group 1: 150 µl of PBS (Control), Group 2: 1 µg of EspB and 1 µg of Int280γ, Group 3: 2 µg of the chimera, Group 4: 10 µg of the chimera, Group 7: 1.10

8 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 and

Salmonella dublin, both expressing the chimera and Group 8: 1.10

8 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 and

Salmonella dublin, both expressing the chimera, plus 1.10

7 FFU BRoVA UK and BCoVB Mebus.. Isotypes were determined in serum dilutions from various vaccinated groups using an indirect ELISA with a purified recombinant chimera as the antigen. Titers are expressed as geometric mean of each group (n = 5). Statistical analysis was performed by Bonferroni test, p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 9.

Mice antibody titers induced by recombinant chimera. Total titers of IgG1 (A) and IgG2a (B). Groups are formed as in

Figure 4 Group 1: 150 µl of PBS (Control), Group 2: 1 µg of EspB and 1 µg of Int280γ, Group 3: 2 µg of the chimera, Group 4: 10 µg of the chimera, Group 7: 1.10

8 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 and

Salmonella dublin, both expressing the chimera and Group 8: 1.10

8 inactivated CFU of ETEC B41 and

Salmonella dublin, both expressing the chimera, plus 1.10

7 FFU BRoVA UK and BCoVB Mebus.. Isotypes were determined in serum dilutions from various vaccinated groups using an indirect ELISA with a purified recombinant chimera as the antigen. Titers are expressed as geometric mean of each group (n = 5). Statistical analysis was performed by Bonferroni test, p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.0001 (****).

Figure 10.

Cytokine production by splenocytes from immunized mice. BALB/c mice were none immunized (control) or immunized with different vaccine formulations. Eighteen days after the last immunization, mice were sacrificed, and spleen cells were stimulated with purified recombinant chimera. After 72 h of culture, the concentrations of IFN-γ (A), IL-17A (B) and IL-5 (C) were determined in the culture supernatant by ELISA. The results are expressed as mean values (±standard error) of three experiments with 5 mice per group. Significant differences were analyzed for each cytokine between different vaccines for each stimulus , p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**).

Figure 10.

Cytokine production by splenocytes from immunized mice. BALB/c mice were none immunized (control) or immunized with different vaccine formulations. Eighteen days after the last immunization, mice were sacrificed, and spleen cells were stimulated with purified recombinant chimera. After 72 h of culture, the concentrations of IFN-γ (A), IL-17A (B) and IL-5 (C) were determined in the culture supernatant by ELISA. The results are expressed as mean values (±standard error) of three experiments with 5 mice per group. Significant differences were analyzed for each cytokine between different vaccines for each stimulus , p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**).

Table 1.

A: Groups of vaccinated mice.

Table 1.

A: Groups of vaccinated mice.

| Groups of mice |

Treatments |

Details |

| 1 |

Control

|

150 µl of PBS |

| 2 |

EspB and Int280γ

|

1 µg of EspB and 1 µg of Int280γ dissolved in 150 µl of PBS |

| 3 |

Chimera protein (low dose)

|

2 µg of Chimera protein dissolved in 150 µl of PBS |

| 4 |

Chimera protein (high dose)

|

10 µg of Chimera protein dissolved in 150 µl of PBS |

| 5 |

Inactivated ETEC B41 expressing Chimera protein |

1.108 CFU of inactivated ETEC B41 expressing Chimera protein resuspended in PBS |

| 6 |

Inactivated Salmonella dublin expressing Chimera protein |

1.108 CFU of inactivated Salmonella dublin expressing Chimera protein resuspended in PBS |

| 7 |

Inactivated ETEC B41 and Salmonella dublin expressing Chimera protein |

1.108 CFU of inactivated ETEC B41 and Salmonella dublin, both expressing Chimera protein resuspended in PBS |

| 8 |

Inactivated ETEC B41 and Salmonella dublin expressing Chimera proteins + BRoVA UK and BCoVB Mebus |

1.108 CFU of inactivated ETEC B41 and Salmonella dublin expressing Chimera proteins resuspended with 1.107 FFU BRoVA UK and BCoVB Mebus |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).