Study proposals, particularly for animal research, typically require justification for a proposed sample size based on statistical power calculations, which are often carried out automatically under defaults in web applets or statistical software. The cost-benefit analysis of this effort to researchers needing funding is easy – and following the usual procedure typically requires little, if any, justification. In our view, however, the foundations of statistical power deserve less blind acceptance and more healthy interrogation by researchers and reviewers.

We see research design as an underemphasized part of the research process and support the expectation that researchers meaningfully justify sample size choices – particularly when there are ethical concerns, such as in animal research. When taken as more than default mathematical calculations, sample size investigations can motivate deeper evaluation of plans for study design, analysis, and interpretation, and expose limitations early enough to promote improvement while taking advantage of the subject matter expertise and creativity of researchers. Before we discuss an alternative path, we visit some concepts we are implicitly trusting by relying on statistical power.

This short communication does not provide yet another tutorial of power-based sample size calculations meant to return a clear-cut answer to the question of exactly how many participants are needed per group; instead, it is meant to spark more critical evaluation of measurement, design, analysis, and interpretation in the research design phase, before resources (including animal lives) are used to carry out the study.

Entering the Hypothetical Land of Error Rates

Opening up the baggage of statistical power starts with interrogating the concepts of Type I and Type II error rates. Under a null hypothesis statistical framework, errors are defined relative to a simple decision around whether to reject the null hypothesis – it is either rejected in error (“reject when we should not”) or not rejected in error (“fail to reject when we should”). The former is a Type I error, the latter is a Type II error, and power is associated with “rejecting when we should,” the non-error compliment to a Type II error. Power calculations are based on long-run rates of these errors over hypothetical replications: Type I error rate (α), Type II error rate (β), and Power (1-β).

Error rates (as opposed to single errors) are conceptually based on a hypothetical collection of many decisions, a proportion of which are errors. The collection of decisions may correspond to many hypothetical identical replications of a study and an analysis under the same statistical model; a collection that is not constructed in real life, thus leaving the error rates as hypothetical – and these are the fundamental ingredients underlying power calculations used to justify real-life research decisions. While we appreciate the theoretical attractiveness and mathematical convenience error rates offer, we question handing them too much authority. They seem to bring an air of objectivity and comfort to an otherwise challenging and messy research process; but their roots inhabit the same soil as statistical hypothesis tests that have been criticized for decades, for example for their rigid focus on often poorly justified null hypotheses and decision rules [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Problems Arising Back in Reality

When we leave the hypothetical land of a having a collection of data sets and associated decisions about rejecting the null hypothesis, we inevitably face issues: Real-life error rates are unknown and even difficult to fully conceptualize – we are not able to repeat experiments identically, we know that assumptions used in the calculations are violated in practice, and, even if the true effect could be equal to null hypothesized value, we never know if the decision about rejecting a null hypothesis is in error for any individual study. Theoretical error rates are only as trustworthy as the assumed model of the process that generated the real-life data – and this statistical model is inherently based on assumptions about reality that are violated and uncertain by definition (otherwise they would not be called assumptions).

While similar cautions apply broadly for statistical methods, in power-related practices we often see blatant ignoring of the underlying model and its connection to theoretical error rates, leading to overconfident expectations about reality and questionable study design decisions. This is exemplified by misleading statements such as “we will be wrong 5% of the time” if we reject a test (null) hypothesis based on a p-value threshold of 0.05; this statement would only be true if the statistical model and all its assumptions were correct and if it would be possible to conduct identical replications of a study – but there are countless explicit and implicit assumptions that are part of a statistical model [

5], so a statement that uses the word “will” is overconfident in almost all cases. The same applies to “we will obtain a statistically significant result in 80% of cases” (if power is 80%), which is misleading for the same reasons stated above. Further, power is not the “probability of obtaining a statistically significant result”, as one can often hear; it is this probability only if the true effect is exactly equal to the alternative hypothesis used for power calculation and if all other model assumptions are correct, which almost never applies in practice.

In general, power calculations beg a lot of trust in unknowns, and yet it is common to treat resulting sample size numbers as if they provide concrete and objective answers to inform crucial research decisions, and often ones with ethical implications. We hope this glimpse into the baggage associated with error rates, and thus power, will spur some healthy skepticism; but motivating change must also acknowledge the unfortunate reality that incentives from peers, funding bodies and animal welfare committees (whether explicit or only assumed by the researchers) promote the comfortable status quo instead of rewarding curiosity about limitations of current methodological norms. Pushback against dichotomous statistical hypothesis testing has gained traction within analysis [

3,

4], but influence on use of power calculations has been limited, despite reliance on the same criticized theory and practices [

6]. An over-focus on simple statistical power also inadvertently encourages ignoring more sophisticated design and analysis principles available to increase precision (and thus decrease, for example, number of animals used), because calculating statistical power with such analyses is often not straightforward or not implemented in default statistical procedures.

An Alternative Definition of Success Tied to Research Context

It is possible to let go of much of the baggage of error rates by shifting away from defining a research “success” in terms of avoiding theoretical Type I and Type II errors toward a context-dependent success based on ranges of values instead of single values for null and alternative hypotheses. A successful study should result in useful information about how compatible the data (and background assumptions) are with values large (or small) enough to be deemed practically important (e.g., clinically relevant) as compared to values too small (or large) to be considered practically important.

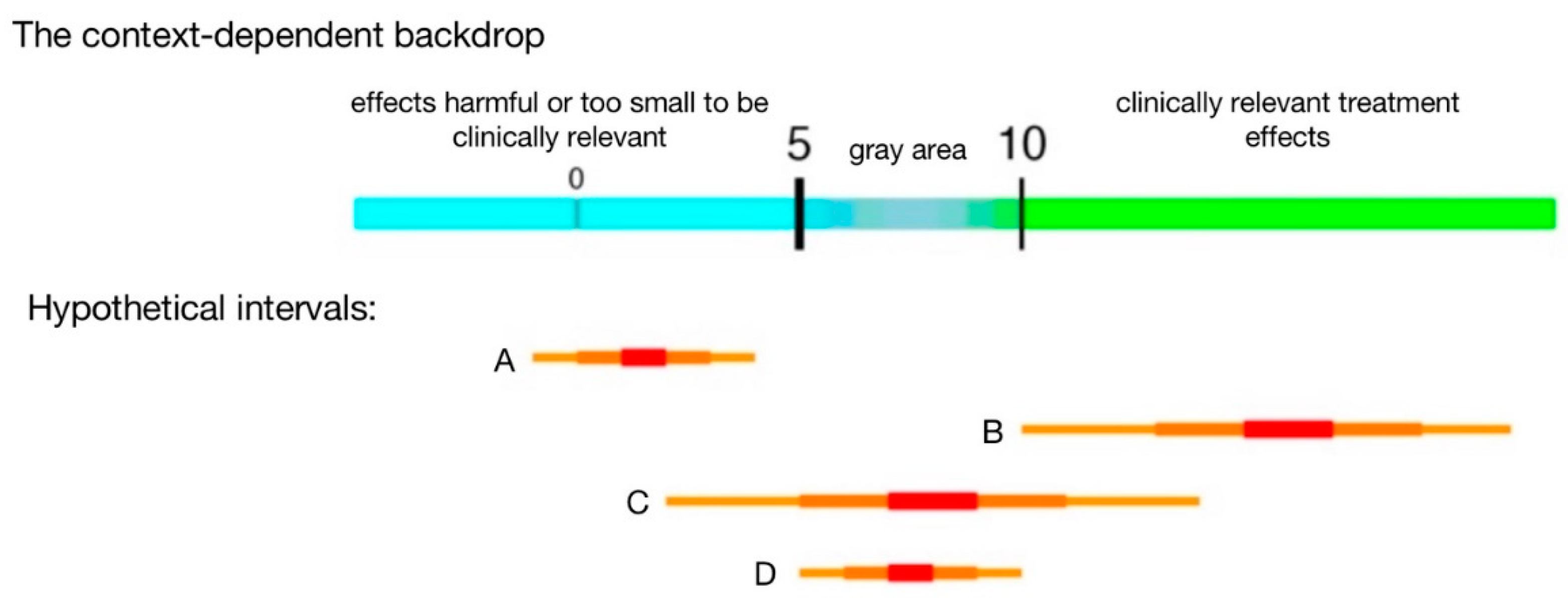

For example, suppose the effect of a new anti-hypertensive drug on average systolic blood pressure has to be a reduction of at least 10 units to be deemed clinically relevant, with a reduction of 5–10 units representing gray area (unclear clinical relevance), and less than 5 clearly not clinically meaningful (though clearly not “no effect”). Then, a sample-size related goal might be to achieve a precision such that an interval is not wider than 5 units. That is, we aim for obtaining an interval that does

not overlap both clinically relevant (values greater than 10) and not relevant values (values less than 5), which is only possible if an interval is wider than 5 units (

Figure 1). Note that such a successful research outcome can accompany a range of p-values and thus is not defined by “statistical significance.”

As alluded to in the example, one strategy for a researcher to exert control over the width of a future interval (precision) is through choice of sample size; more information and technical guidance on choosing a sample size based on precision rather than power can be found elsewhere [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. While precision-based approaches can be carried out in ways just as automatic and default as traditional power-based approaches, the focus on intervals invites use of context-dependent knowledge and expertise related to the treatment and proposed methods of measurement. In this spirit, we offer a larger framework for incorporating research context and interpretation of results

a priori [

12,

13].

A picture can help clarify alternative definitions of success (

Figure 1): Intervals A and B clearly distinguish between regions of different practical implications, and both are considered study successes because all values in A are deemed too small to be clinically relevant, and nearly all values in B are large enough to be clinically relevant. Interval C, on the other hand, is not considered a success because it contains values in both regions, not supporting a conclusion in either direction. Narrower intervals (greater precision) help to avoid scenario C and facilitate successes (A and B). Even with a narrow interval, we can still land in gray area (D); while potentially frustrating, such is the reality of doing research and D still provides valuable information to inform future research.

As

Figure 1 conveys, this approach requires initial context-dependent work to draw the number line delineating the regions. While simple in construction, the process is not trivial and can be surprisingly challenging, partly because it is a novel exercise for most researchers and statisticians. Assigning practical or clinical importance to values

a priori can be compared to creating a backdrop in theatre productions – a picture hanging behind the action of a play to provide meaningful context. In research, a “quantitative backdrop” [

13] provides a contextual basis in front of which study design, analysis, and interpretation of results take place, ideally without over-reliance on arbitrary default statistical criteria (

Figure 1).

Loosening Our Grip on Interval Endpoints

Our use of the term “interval” thus far has been purposefully vague, as our definition of success does not depend on any particular method for obtaining intervals (whether they are called confidence, credible, or posterior intervals), only that the researcher sufficiently trusts the interval and can justify its use to others (Box 1). We promote relaxing long-held views of what a statistical interval does or should represent and see interpretating confidence or credible intervals as compatibility intervals [

4,

5,

14,

15] as a step in this direction. Compatibility encourages a shift from dichotomously phrased research questions (e.g., “is there a treatment effect?”) to the more meaningful “what are possible values for a treatment effect that are most compatible with the obtained data and all background assumptions?” (to which the answer would be: the values inside the obtained interval [

15]).

We can also relax the rigidity with which interval endpoints are interpreted. When drawing an interval, the line must have ends, but values beyond the endpoints do not suddenly switch from being compatible with the data and assumptions, to incompatible. Values inside the interval are just considered

more compatible, and values outside are

less compatible [

4], and that applies whether we have a 95% or 80% or any other interval. Loosening our grip on the rigidity of endpoints can facilitate another shift from believing we are calculating the one and only sample size answer to undertaking an investigation that honors limitations and challenges.

The reality is that to carry out a sample size calculation based on precision (via math or computer simulation), we must input a specific interval width. This may at first seem inconsistent with the recommendation to relax interpretations of intervals and rigidity of endpoints. However, there is no conflict if we also relax our belief that there is a single correct answer to the sample size question and instead use the exercise to motivate a nuanced investigation to help understand challenges inherent in carrying out the study. This can include many calculations to reflect different levels of precision and varying sensitivity to assumptions.

As previously mentioned, precision-based methods can be easily used to carry out a typical power calculation in disguise, rather than the more holistic approach we are promoting. Several practices can help avoid using them as power calculations in disguise: (1) avoid using confidence intervals to carry out hypothesis tests by simply checking if they contain a null value (a null hypothesis), (2) embrace the

a priori work of developing the context-specific backdrop identifying the range of values to be considered practically, or clinically, relevant, (3) create the backdrop using a scale that facilitates practical interpretation within context (e.g., not standardized effect sizes), and (4) contrary to common advice, do not simply use a previously obtained estimate to delineate the ranges of values in the backdrop (e.g., the 5 or the 10 in

Figure 1).

The last point deserves further attention: it is common to use previous estimates (such as pilot study results) as the “(practically meaningful) alternative value” in traditional power calculations, though this is not necessary or recommended. The practice has negative implications for sample size justification [

10], for example because published effect estimates are often exaggerated [

16]. Such practice can lead to sample sizes that are smaller than needed (if the published estimate is larger than the smallest values deemed practically relevant) or larger than needed (if the published estimate is smaller than what is deemed practically relevant). There is no reason a previous estimate should automatically be judged practically relevant – it can fall anywhere relative to the backdrop and should not change the

a priori developed backdrop! This can be confusing because it is counter to what is often taught and expected from funding agencies. Relative to the previous example, a pilot study may have produced an estimated reduction of 4 units – which when considered relative to the backdrop is not clinically relevant and therefore there is no reason to increase the sample size to attempt to detect an effect as small as 4 units. The decision of what values will be judged practically relevant should thus be made based on knowledge of the subject matter (e.g., medical) and of the measurement scale, not on previous estimates of an effect of interest.

Taking Back the Power Shouldn’t Be Easy

A common question when considering this framework is: What if researchers do not have enough knowledge of how the outcome variable’s measurement scale is connected to practical implications to create the quantitative backdrop? That is, what if they are not able to identify values that would be considered large, or small, relative to practical implications? If this is the case, then we argue researchers should honestly declare that with the currently available knowledge, it is impossible to come up with a justifiable sample size. In such a situation, using default power calculations will essentially just move the research challenge into the analysis and interpretation phase, after already using valuable resources for the experiment – because if practical implications of possible outcomes are unclear before the experiment, they are usually still unclear after results are in. Instead, an inability to identify practical implications of possible outcomes in the planning stage of a study would highlight the exploratory nature of the research and a need for better understanding of the outcome variable, which could be a valuable research goal by itself.

Engaging in a sample size investigation as we are recommending will not feel easy. Investigating sample sizes, rather than calculating them using default power analysis settings will bring up hard questions, throw light on assumptions that were previously hidden, and create additional problems to address. We need constant reminders that statistical methods depend on a substantial set of background assumptions; and methods for justifying sample sizes are no exception.

Sample size investigation presents an opportunity for researchers to give up simple math calculations in exchange for taking back some of the authority and creativity blindly given over to statistical power for decades. We have a responsibility as scientists to work to understand and interrogate our chosen scientific methodologies to the best of our ability – to avoid being fooled by our own assumptions. Embracing this challenge in the design phase of a study can lead to higher quality research, and ultimately to more efficient research spending and respect for animal lives.

The “coverage” rate definition of a 95% confidence interval says that 95% of the hypothetical confidence intervals coming from theoretical data sets generated under the same design and model would contain (or “cover”) the true value; 5% of such intervals are expected to be “errors” in terms of excluding the true value.

Confidence intervals can be created by inverting hypothesis tests: a 95% confidence interval includes possible values (e.g., effect sizes) for the null hypothesis that would have p-values larger than 0.05, given the statistical model. The interval can thus be taken as conveying the effect sizes that have the least information against them and are most compatible with the data, given all background assumptions; it can therefore be termed a compatibility interval [

4,

14,

15].

Intervals matching classic confidence intervals can arise more generally as quantiles of a distribution summarizing the most common values of a distribution without any need for referencing a true value or defining an error rate. This is the motivation for using posterior intervals within Bayesian inference as summaries of the inner part of posterior distributions. In a non-Bayesian setting, intervals can be used to summarize randomization distributions or sampling distributions, again with no reliance on true or hypothesized values or error rates. A 95% interval, for example, provides the interval excluding values beyond the 97.5 percentile and below the 2.5 percentile.

We encourage this more general “summarizing a distribution” interpretation that helps relax interpretation of the endpoints from hard-boundary thresholds to rather arbitrary summaries of a distribution of interest. Displaying intervals as a collection of segments representing different choices for quantiles (e.g., 95% and 80%) facilitates this view (

Figure 1).

The goal is to have a more general interpretation of intervals beyond error and coverage rates that allows their use as a way to (necessarily imperfectly) represent the values most compatible with the data and all background assumptions (the model), as well as with context-dependent knowledge.

References

- Rothman KJ. Significance questing. Annals of Internal Medicine 1986; 105: 445–447.

- Gigerenzer G. Statistical rituals: The replication delusion and how we got there. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 2018; 1: 198–218.

- Wasserstein RL, Schirm AL, Lazar NA. Moving to a world beyond “p < 0.05”. The American Statistician 2019; 73 sup1: 1–19.

- Amrhein V, Greenland S, McShane B. Retire statistical significance. Nature 2019; 567: 305–307.

- Amrhein V, Trafimow D, Greenland S. Inferential statistics as descriptive statistics: There is no replication crisis if we don't expect replication. The American Statistician 2019; 73 sup1: 262–270. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa S, Lagisz M, Yang Y, et al. Finding the right power balance: Better study design and collaboration can reduce dependence on statistical power. PLoS Biology 2024; 22: e3002423. [CrossRef]

- Greenland S. On sample-size and power calculations for studies using confidence intervals. American Journal of Epidemiology 1988; 128: 231–237. [CrossRef]

- Goodman SN, Berlin JA. The use of predicted confidence intervals when planning experiments and the misuse of power when interpreting results. Annals of Internal Medicine 1994; 121: 200–206. [CrossRef]

- Cumming G. Understanding the New Statistics. New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Ramsey F, Schafer D. The Statistical Sleuth: A Course in Methods of Data Analysis. Brooks/Cole, Boston, 3rd Edition, 2013.

- Rothman K, Greenland S. Planning study size based on precision rather than power. Epidemiology 2018; 29: 599–603. [CrossRef]

- Higgs MD. Sample size without power – Yes, it’s possible. Critical Inference 2019. https://critical-inference.com/sample-size-without-power-yes-its-possible.

- Higgs MD. Quantitative backdrop to facilitate context dependent quantitative research. Critical Inference 2024. https://critical-inference.com/quantitative-backdrop.

- Rafi Z, Greenland S. Semantic and cognitive tools to aid statistical science: replace confidence and significance by compatibility and surprise. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2020; 20: 244. [CrossRef]

- Amrhein V, Greenland S. Discuss practical importance of results based on interval estimates and p-value functions, not only on point estimates and null p-values. Journal of Information Technology 2022; 37: 316–320.

- van Zwet E, Schwab S, Greenland S. Addressing exaggeration of effects from single RCTs. Significance 2021; 18: 16–21. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).