1. Introduction

Boron, positioned nearest to carbon in the periodic table, shares various structural attributes and represents a typical electron-deficient element. Experimental and theoretical investigations of elemental boron clusters have been ongoing since the 1980s [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Systematic experimental and computational analyses have revealed the propensity of boron clusters to exhibit planar or quasi-planar structures across diverse size scales. Owing to the electron deficiency, boron-based clusters possess a unique electron distribution orbital structure, enabling the formation of distinct chemical bonds. Within these clusters, chemical bonding is influenced by π/σ aromaticity, antiaromaticity, and conflicting aromaticity, necessitating electron delocalization to counterbalance boron's inherent electronic deficiencies [

4,

5,

6,

9]. Additionally, the unusual bonding mode also leads to dynamic structural fluxionality of bare boron clusters and related compound systems.

Metal atoms are introduced into boron clusters to create boron-based alloy clusters. The approach proves effective in exploring structural diversity, adjusting electronic properties, and uncovering new chemical bonds within these clusters [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Utilizing intramolecular charge transfer allows precise electron counting in alloy clusters, facilitating the deliberate design of new cluster structures and deeper investigation into their bonding and dynamic attributes. Structural fluxionality is an extraordinary attribute inherent in boron clusters, manifesting as dynamic flexibility. The electron deficiency of boron contributes significantly to this distinct dynamic behavior. Researchers have consistently designed and documented a range of pure boron clusters showcasing dynamic fluxionality, including B

11−, B

13+, B

15+, and B

19− [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Subsequent research revealed that blending different metals enables the deliberate design of boron-based cluster nanomachines exhibiting dynamic fluxionality. In 2017, Zhai and colleagues identified nearly isoenergetic three-layer and spiral structures within the Be

6B

11− cluster [

25]. The former sandwich structure demonstrates two dynamic rotation/twisting modes, resembling structural fluidity akin to the nanoscale Earth-Moon system. Furthermore, researchers have observed magical dynamic fluxionality in a range of binary boron-based nanoclusters, including Na

5B

7, V

2B

7−, Be

3B

11− [

26,

27,

28], among others.

To diminish the dynamic energy barrier associated with fluxionality, researchers started incorporating multiple metal atoms to alter the electron distribution within boron clusters. Compass-like clusters MB

7X

2 and MB

8X

2 (where X stands for Zn or Cd and M represents Be, Ru, or Os) [

29], the X

2 needle undergoes rotation along the B

8 wheel. The central B

6 ring within the boron-based ternary Rb

6Be

2B

6 cluster [

30], featuring a distinct sandwich structure, emerges as exposed bare B enclosed by two tetrahedral BeRb

3 ligands. The bonding pattern within the vast sandwich cluster encourages distinctive dual-mode dynamic fluxionality. The study aims to examine the structure of the ternary cluster B

8Al

3+, analyze its structural stability, and determine if it presents novel instances of dynamic structural fluxionality. The GM structure of the B

8Al

3+ was determined using CK search. The B

8Al

3+ cluster exhibits a three-layer structure. Its geometric configuration resembles a "clock": the middle B

8 ring create the dial, while the two aluminums above it atoms act as pointer, with an Al unit below it. Chemical bonding analysis indicates that the B

8Al

3+ cluster exhibits 6π/6σ dual aromaticity, with a double delocalized electron cloud facilitating a continuous "orbit," enabling unrestricted rotation of the Al

2 unit above the B

8 ring. Charge calculations reveal evident charge transfer among the Al

2 unit, Al atom, and the B

8 ring, presenting a formal description as a [Al]

+[B

8]

2−[Al

2]

2+ ion complex.

2. Results

2.1. Global-Minimum of B8Al3+ Cluster

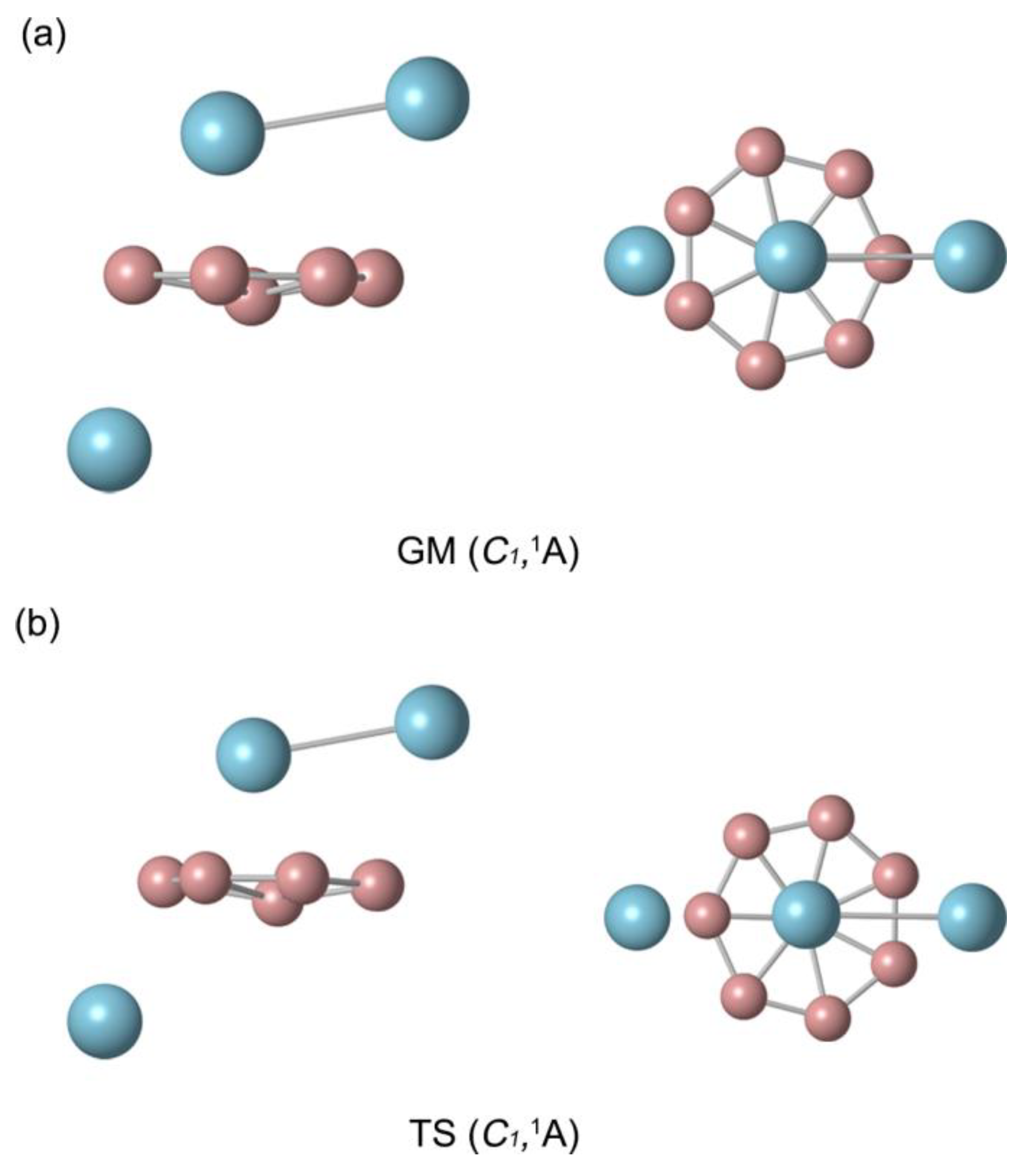

Figure 1a show the GM

C1 (

1A) structure of B

8Al

3+ cluster. The relative energies of the top 20 low-lying isomers, including zero-point energy correction (ZPE), are provided in

Figure S1. The B

8Al

3+ cluster exhibits

C1 symmetry, signifying the global minimum on the potential energy surface. Initial computations using PBE0/def2-TZVP on the top 20 structures revealed the GM cluster to be 1.01 kcal mol

−1 lower in energy than its nearest competitor. It is worth noting that within the DFT method, the PBE0 and B3LYP functionals are widely acknowledged for their complementarity in molecular systems. To ensure computational consistency across density functionals concerning geometry and energetics, we completed a comparison at the B3LYP/def2-TZVP method level, revealing the GM cluster to be 7.71 kcal mol

−1 lower in energy than its closest competitor. Subsequent calculations conducted at the CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP//PBE0/def2-TZVP and complementary CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP//B3LYP/def2-TZVP levels indicated energy advantages of 5.61 kcal mol

−1 and 4.65 kcal mol

−1, respectively, for the GM structure. Hence, based on the aforementioned data, the GM

C1 (

1A) structure of B

8Al

3+ cluster is confirmed to be a really minimal structure on the potential energy surface.

Figure 1a displays the top and side views of the GM B

8Al

3+ cluster, representing a closed-shell electronic system. The GM B

8Al

3+ cluster comprises three layers, resembling a clock: the middle B

8 ring create the dial, while the two aluminums above it atoms act as pointer, with an Al unit below it.

Figure 1b demonstrates the similarity between the TS structure and the GM structure, where the Al–Al pointer rotates approximately 25.7° to achieve the TS structure. Currently, the Al–Al pointer is positioned between the two B atoms on the dial. The cartesian coordinates of GM cluster and TS structure at PBE0/def2-TZVP are presented in

Table S1.

2.2. Bond Distances, Wiberg Bond Indices, and Natural Atomic Charges

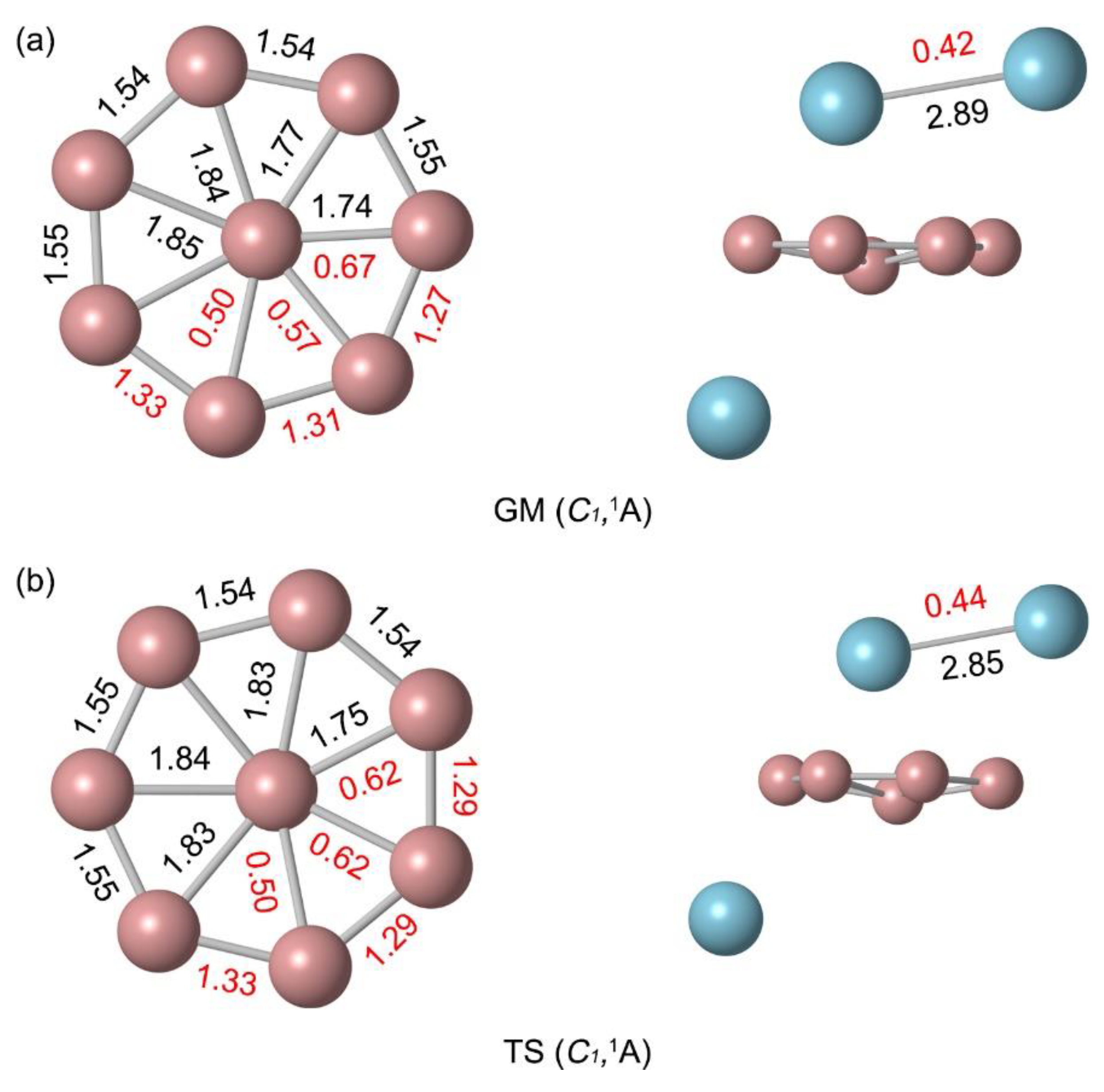

Figure 2a displays the bond distances and bond orders for GM B

8Al

3+ cluster. The boron ring's peripheral bond distances are 1.54−1.55 Å, below the upper-bound of 1.70 Å for B−B single bonds. It suggests a force between the B atoms involving both covalent single bonds and delocalized electrons, the bond orders of the B

8 ring are greater than 1, which also illustrates this essence. Radial B–B links are much longer (1.74−1.85 Å), the links are in line with delocalized π/σ bonding, which are weaker than single bond. Indeed, their calculated WBIs amount to 0.50−0.67. The distance between the two Al atoms, 2.89 Å, is close to the upper limit of the Al−Al single bond (2.52 Å), and the corresponding Al−Al bond order is 0.42, indicating the presence of an Al−Al single bond.

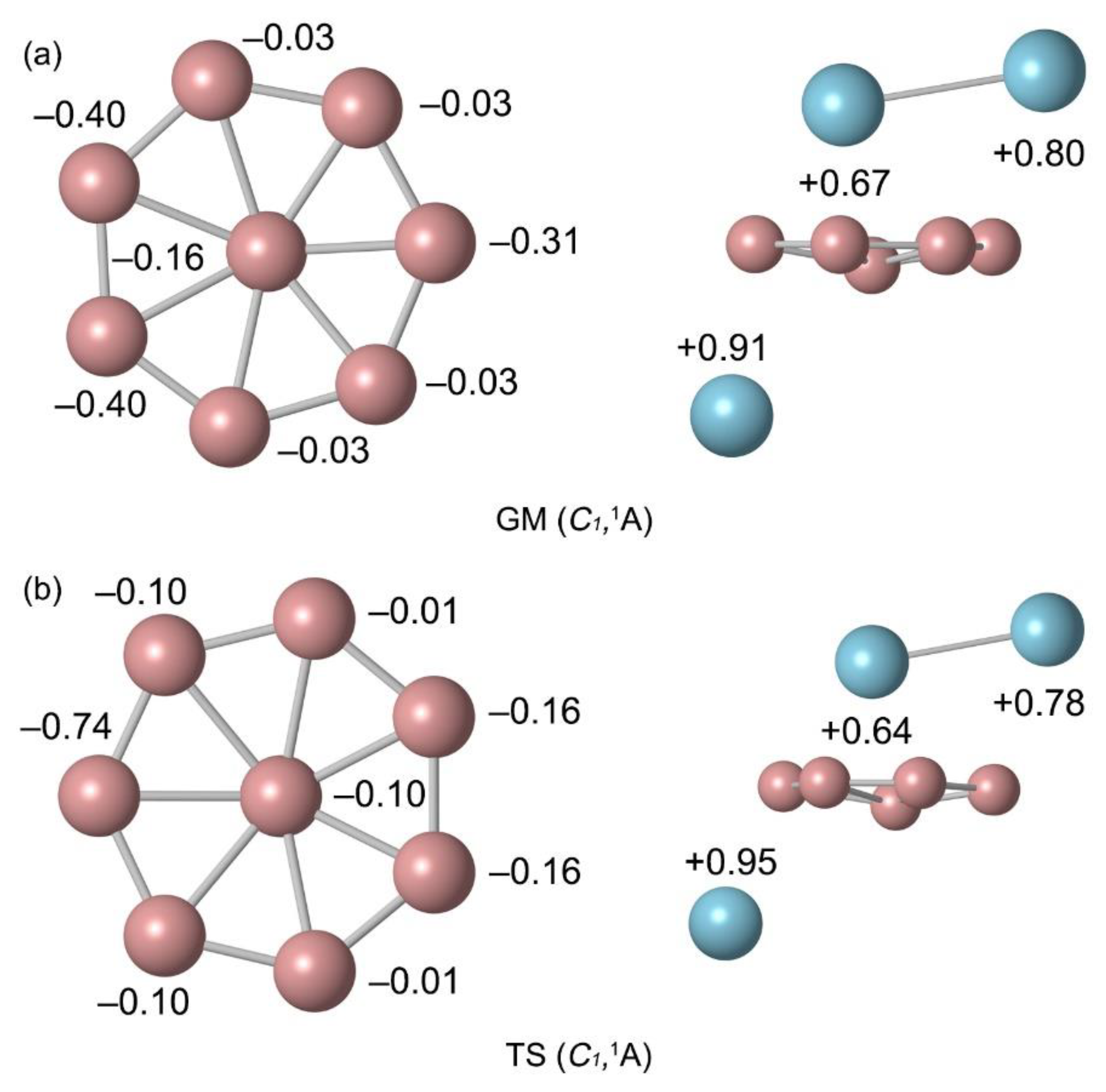

The natural atomic charges were calculated by natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis as shown in

Figure 3. The Al atom below the B ring carry a positive charge of +0.91 |e|. This natural atomic charge data indicate that there is one electron transfers from Al atom to the B

8 ring. The rightmost B atom near the pointer Al

2 carry a charge of −0.31 |e|, indicating an electrostatic interaction between the B and Al atoms (

Figure 3a). The B atoms are negatively charged from −0.03 to −0.40 |e| in GM and from −0.01 to −0.74 |e| in TS. The charge carried by Al

2 unit is +1.47 |e|, which can be approximately regarded as transferring two electrons to the B

8 ring. The bond distances and bond order of TS and GM are similar. Due to the deflection of the Al needle, the natural atomic charge changes slightly. Overall, the charge transfer case is identical. The similarity in structure and chemical bonding of GM and TS implies a lower energy barrier between them. Thus, both the GM and TS structures of B

8Al

3+ cluster are essential charge transfer complexes of [Al]

+[B

8]

2−[Al

2]

2+.

3. Discussion

3.1. Dynamic Structural Fluxionality

Vibration frequency analysis was conducted on the GM and TS structures of B

8Al

3+ cluster at PBE0 level, as illustrated in

Figure S2. The GM B

8Al

3+ cluster exhibits a vibration soft mode at 30.43 cm

−1, correspond the tangential reverse motion involving the Al

2 unit and the B

8 ring. The movement along the vibration soft mode vector leads to the formation of the corresponding TS structure. The TS structure's vibration soft mode is 29.48

i cm

−1. Both exhibit similar rotation modes that facilitate the relative rotation of the Al

2 unit above the B

8 ring. These soft vibrational modes are perfectly in line with dynamic structural fluxionality of the system as a molecular rotor.

To vividly demonstrate the dynamic fluxionality of B8Al3+ cluster, we have run a BOMD simulation at a selected set of temperatures of 300 K for a time span of 50 ps. The system dynamics trajectories were obtained by taking GM structure as the initial coordinate at PBE0 level. The BOMD data are visualized using GaussView, which vividly show that the present ternary cluster behaves closely like a functioning compass at the subnanoscale. The BOMD simulation results vividly illustrate the dynamic fluxionality process within the B8Al3+ cluster: the Al−Al unit rotates above the B8 ring, resembling the motion of a clock hands. Throughout the BOMD simulation, the B8Al3+ cluster consistently retained geometric stability without noticeable deformation. A short movie is extracted from the simulation and presented in the ESI. The animation approximately lasts for 12 ps.

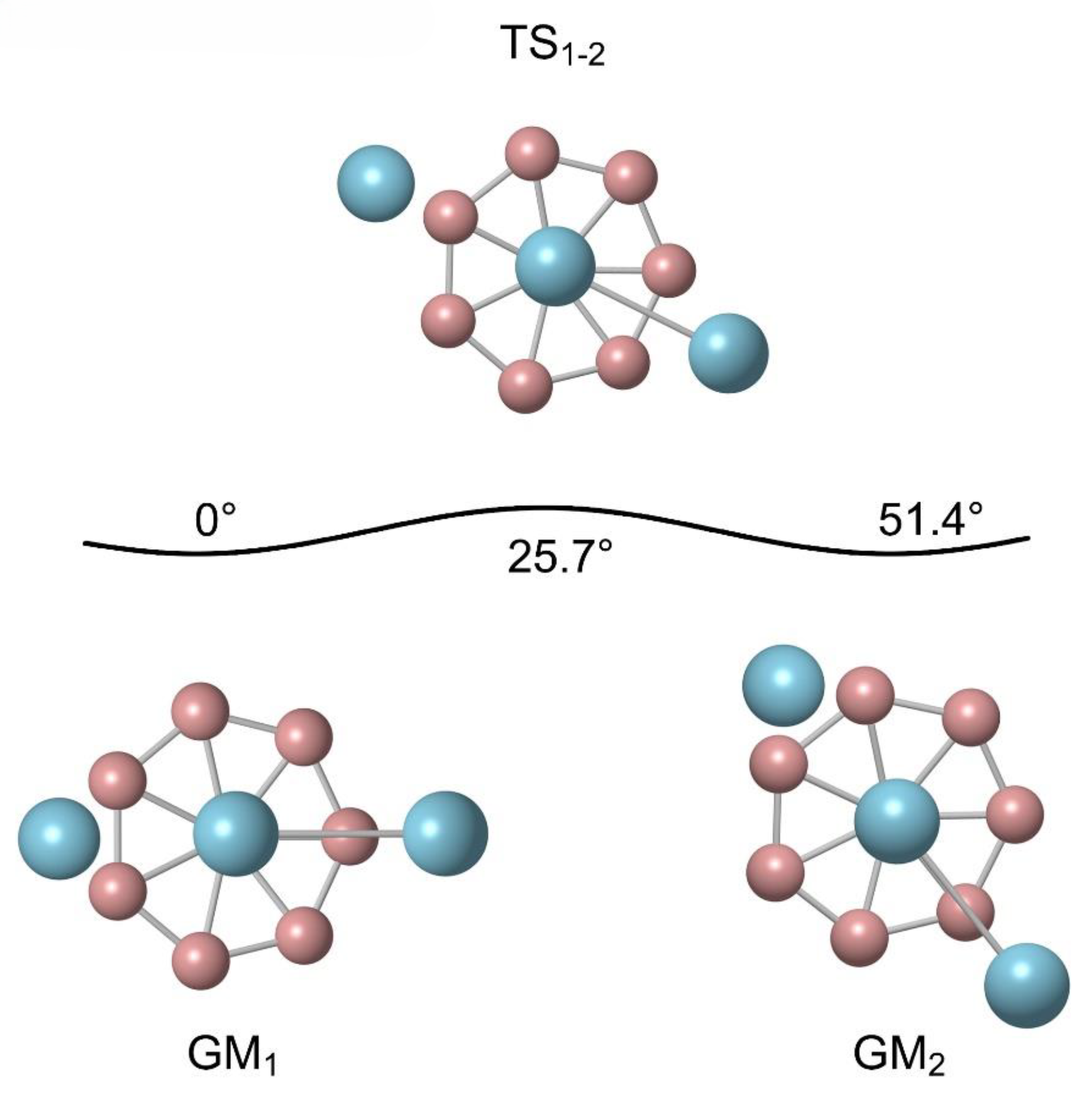

Figure 4 displays the dynamic evolution process of B

8Al

3+ cluster. The rotation energy barrier for B

8Al

3+ cluster is 0.32 kcal mol

−1 at PBE0 level, refined to 0.19 kcal mol

−1 at the CCSD(T) level. The Al−Al unit, resembling a pointer, is suspended above the B

8 ring. Starting from GM

1 as the initial configuration, it rotates clockwise with the B

8 ring's center as the axis. As the Al−Al pointer rotates 25.7° clockwise, surpassing the rotation energy barrier, it reaches the first transition state, TS

1-2, while the Al−Al pointer is perpendicular to the B-B bond of the two adjacent B atoms below at this stage. Further rotate Al–Al dimer by 25.7° clockwise, one recovers the GM geometry (GM

2). Subsequently, it continues to rotate clockwise, always exceeding the reaction energy barrier. After completing the above process by six TS configurations and five GM configurations, all atoms in B

8Al

3+ cluster eventually return to their initial positions.

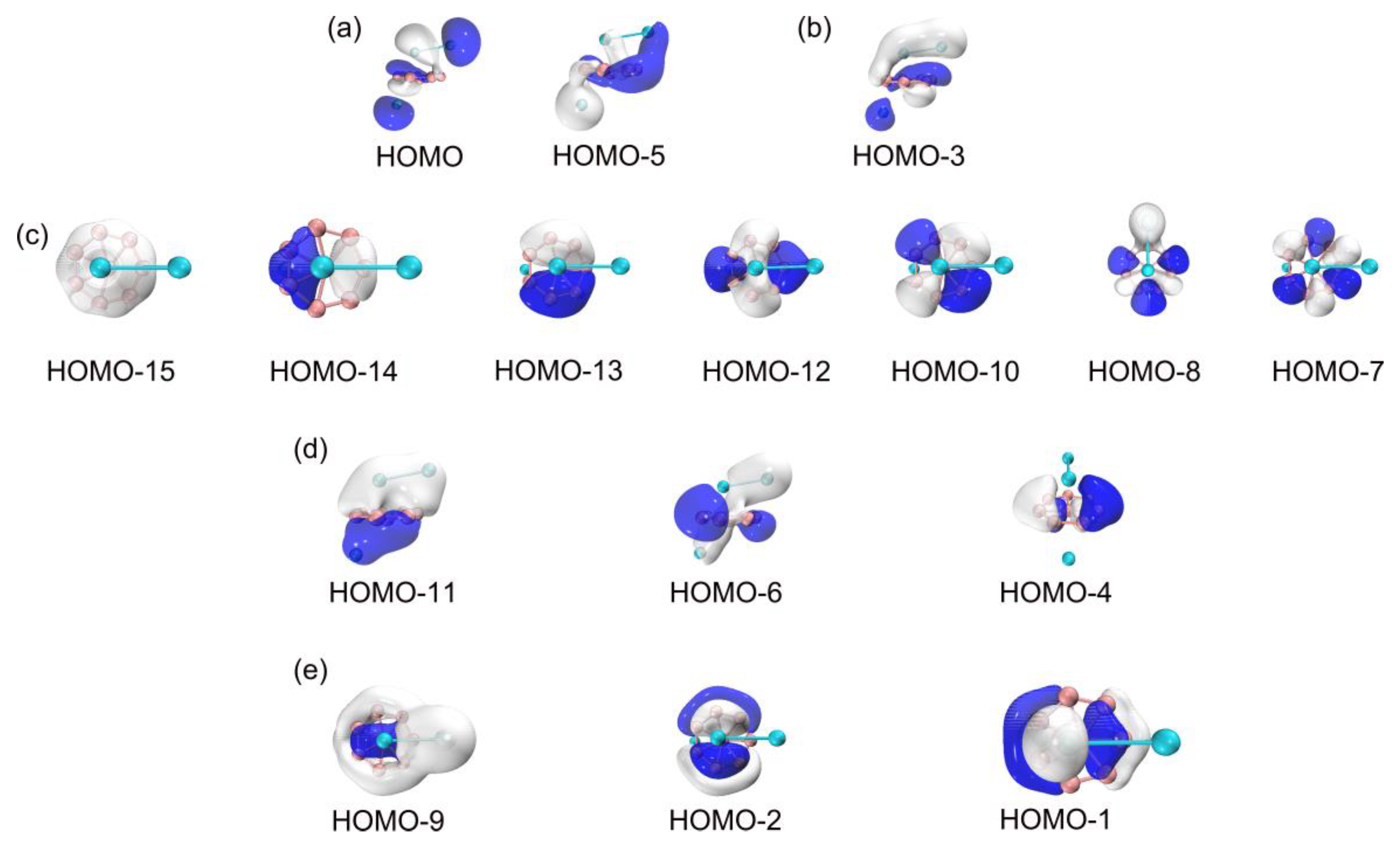

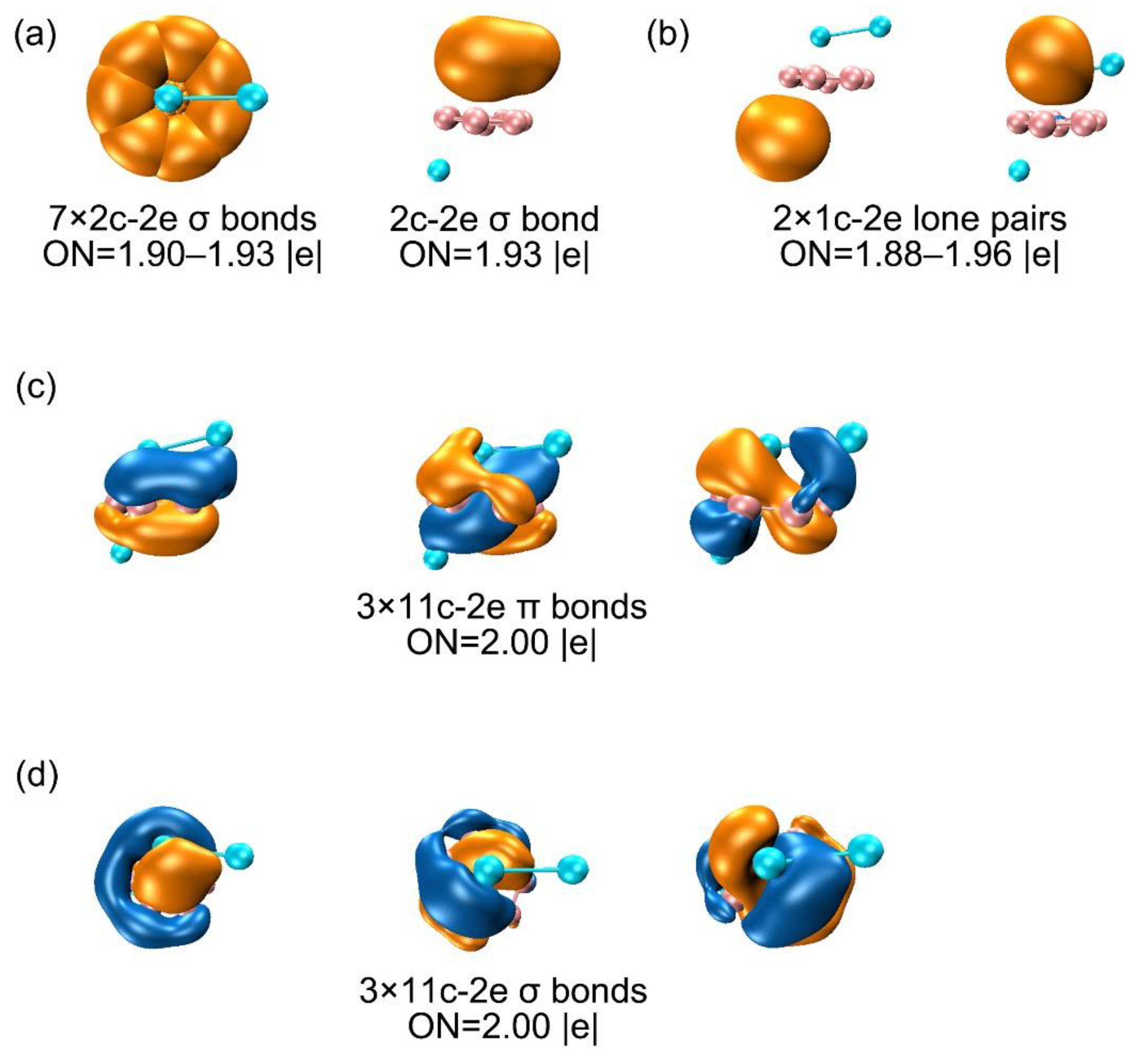

3.2. Chemical Bonding

To understand the unique geometries, stability, and dynamic fluxionality of GM B

8Al

3+ cluster, it is essential to elucidate their chemical bonding. For this purpose, CMOs and AdNDP analyses are fundamental. The GM B

8Al

3+ cluster is a closed-shell cluster with 32 valence electrons. Its 16 occupied CMOs are sorted to five subsets based on their constituent atomic orbitals (AOs) as shown in

Figure 5. The two CMOs in subset (a) are composed mainly of 3s/3p AOs from two aluminum atoms, in their constructive versus destructive combinations. According to the CMO construction principles, these two CMOs can be localized as the lone pairs of Al 3s

2. HOMO−3 in subset (b) is responsible for interlayer Al–Al σ single bond, which originate from 3s AOs of two Al atoms. Meanwhile, the 14 orbital electrons in subset (c) are derived mainly from the 2s and 2p atomic orbitals of B

8 ring.

There are seven CMOs in subset (c) contain HOMO−15, HOMO−14, HOMO−13, HOMO−12, HOMO−10, HOMO−8 and HOMO−7, which constitute a complete series with from 0 up to 3 nodal planes (sequentially from left to right), including 2 degenerate pairs. Upon recombination, these seven orbitals can form seven two-center two-electron (2c-2e) bonds, thereby being localized as seven B–B σ bonds. These Lewis-type bonds constitute the cluster's structural framework, utilizing a total of 14 electrons.

Figure 6a shows the AdNDP bonding scheme, affirming the alignment between seven CMOs and the seven 2c-2e single bonds on the B

8 ring. The occupation numbers (ONs) are 1.90–1.93 |e|, which generally close to ideal value of 2.00 |e|. Subset (d) is the cluster's delocalized π framework, primarily sourced from the 2s/2p orbitals of B atoms (

Table S2). The corresponding AdNDP bonding scheme allocates three delocalized π orbitals into three 11c-2e bonds, with an occupation value of 2.00 |e|. Three CMOs in subset (e) constitute a delocalized 6σ subsystem, situated on the 8 B atoms. Subsets (d) and (e) each comprise 3 orbitals and 6 delocalized electrons, satisfying the (4

n+2) Hückel rule (

n=1), establishing the cluster's π/σ dual aromaticity. In Subset (b), an Al–Al σ orbital aligns with AdNDP bonding principles. Corresponds to the AdNDP scheme in

Figure 6a (right). In the TS structure, the CMOs, AdNDP scheme, orbital compositions virtually do not alter (

Figure S3 and S4, ESI†), which explain why the dynamic fluxionality process has no energy barrier.

In summary, the chemical bonding of B8Al3+ cluster consists of the lone pairs of two Al atoms, a covalent Al-Al single bond, seven 2c-2e Lewis single bonds within the B8 ring, three 11-center delocalized σ and three 11-center delocalized π bonds, which establishes their two-fold 6π/6σ aromaticity. This dual aromaticity collectively underlie the unique dynamic fluxionality for cluster.

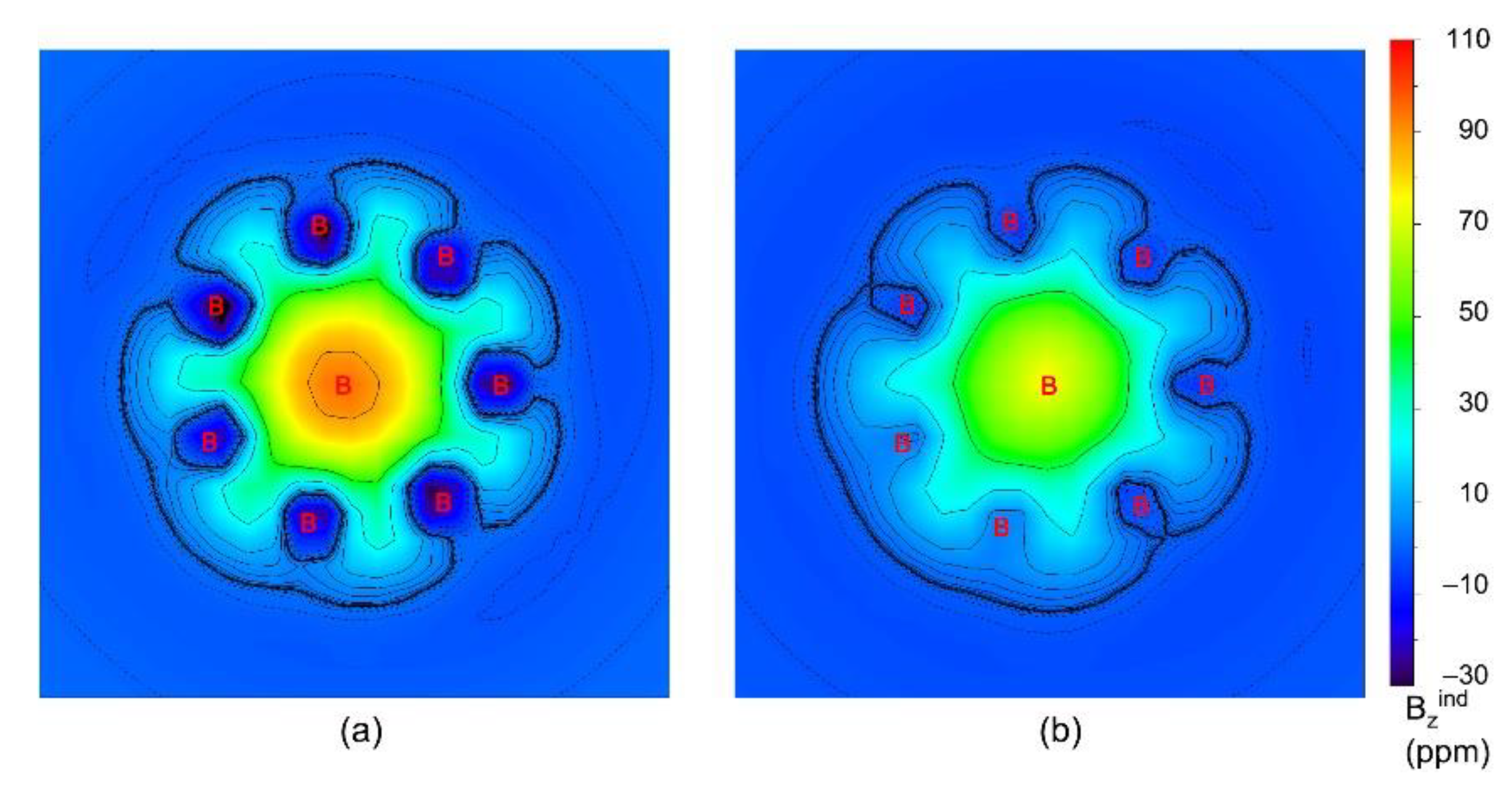

To more intuitively observe the dual 6π/6σ aromaticity, the color-filled maps of ICSS

zz of B

8Al

3+ cluster at 0 (ICSS

zz(0)) and 1 Å (ICSS

zz(1)) above the B

8 ring plane are plotted in

Figure 7. The green areas in (a) and (b) within the molecular wheel, in which the shielding effect is primarily concentrated, are in line with σ and π aromaticity of the cluster, respectively. Obviously, the [B

8]

2− unit has doubly 6π/6σ aromatic, which is the key factor that causes the ground state to stabilize. In essence, 6π/6σ double aromaticity of [B

8]

2− which is based on its charge-transfer as described previously. Nucleus-independent chemical shifts, NICS and NICS

zz, are calculated for GM B

8Al

3+ cluster as an additional criterion for aromaticity (

Table S3, ESI). The large negative values are consistent with the assessment of π and σ double aromaticity. The NICS and NICSzz values at the centre of a B

3 triangle are actual helpful for understanding the aromaticity of GM B

8Al

3+, whereas those at 1 Å below the plane probe π aromaticity. The electron clouds over the system are uniform and dilute facilitate dynamic fluxionality which are based on two-fold magic 6π/6σ aromaticity.

4. Methods

The global minimum (GM) structure and low-lying isomers of the B

8Al

3+ cluster were determined through Coalescence Kick (CK) search and more than 5000 stationary points (3000 singlet and 2000 triplet) were detected on the potential energy surface with the help of artificial structure construction [

31,

32]. The candidate low-lying structures were subsequently reoptimized at the PBE0/def2-TZVP level [

33,

34]. Frequency calculations were carried out at the same level to ensure that the reported structures are true minima. To check for computational consistency of different functionals in structures and energetics, the zero-point correction energy was also calculated at the B3LYP/ PBE0/def2-TZVP. In order to benchmark the relative energies, the top five low-lying isomers, were further assessed at the single-point CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP level on the basis of their PBE0/def2-TZVP and B3LYP/def2-TZVP geometries [

35,

36,

37].

At the PBE0/def2-TZVP level, orbital composition analysis was completed through NAO calculations, and Wiberg bond indices (WBIs) and natural atomic charges were obtained through natural bond orbital (NBO) calculations [

38]. Chemical bonds were elucidated using canonical molecular orbital (CMO) analysis and adaptive natural density partitioning (AdNDP) [

39]. Nucleus independent chemical shifts (NICSs), Iso-chemical shielding surfaces (ICSSs) were calculated to evaluate π/σ aromaticity [

40,

41]. AdNDP analysis and ICSSs calculations were done with the Multifwn program [

42]. We performed e Born-Oppenheimer molecular dynamics (BOMD) simulations at a temperature of 300K to study the dynamic properties of the clusters [

43]. All the above calculations are done using the Gaussian 09 software package [

44]. The visualization of calculation results is completed through GaussView, CYLview and VMD programs [

45,

46,

47].

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have designed a cationic ternary boron-based binary B−Al cluster, B8Al3+, which adopt three-layered structure can be seen as subnanoscale clock in shape with a quasi-planar B8 wheel. And the Al2 pointer that above the wheel and another aluminum atom under it. It features dynamic structural fluxionality at 300 K. Charge calculations suggest that the cluster can be described as a charge-transfer ion complex and formulated as [Al]+[B8]2−[Al2]2+, whose three charged layers are bound via quite strong electrostatic forces. BOMD simulation indicates that the Al–Al pointer can freely rotate on the dial below, requiring an energy barrier of 0.19 kcal mol−1 to facilitate its rotation. Chemical bonding analyses indicate a magic 6π/6σ double aromaticity of B8Al3+ cluster. The dual delocalized electron clouds create a fluid “orbital” that allows the Al2 unit above the B8 ring to rotate freely, thus imparting dynamism to the cluster. The balance of electrostatic traction and repulsion between layers are the critical contribution to the dynamic fluxionality of the cluster.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org., Table S1: Cartesian coordinates for optimized global-minimum (GM) and transition-state (TS) structures of B8Al3+ cluster at the PBE0/def2-TZVP level; Table S2: Orbital composition analyses for occupied canonical molecular orbitals (CMOs) of GM (C1, 1A) B8Al3+ cluster; Table S3: Calculated NICSzz and NICS (shown in italics in brackets) of GM B8Al3+ cluster at the PBE0/def2-TZVP level. These values are calculated at the center of B3 triangle, as well as at 1 Å above the center; Figure S1: Alternative optimized structures for B8Al3+ cluster at the PBE0/def2-TZVP level including zero-point energy (ZPE) corrections, along with their relative energies. Relative energies are also presented for top five lowest-energy isomers at the single-point CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP//PBE0/def2-TZVP (in parentheses) and for top two lowest-energy isomers at the B3LYP/def2-TZVP (in square brackets, with ZPE corrections), and single-point CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP//B3LYP/def2-TZVP (in curly brackets) levels of theory. All energies are shown in kcal mol–1; Figure S2: Displacement vectors of the vibrational modes of (a) GM and (b) TS structures of the B8Al3+ cluster at the PBE0/def2-TZVP level; Figure S3: Pictures of occupied canonical molecular orbitals (CMOs) of TS B8Al3+ cluster. (a) Lone pairs. (b) Lewis-type Al–Al σ bond. (c) Seven CMOs for Lewis B–B σ single bonds along the periphery of disk B8 motif. (d) Three delocalized π CMOs. (e) Three delocalized σ CMOs; Figure S4: AdNDP bonding scheme for TS (C1, 1A) B8Al3+ cluster. Occupation numbers (ONs) are shown.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-J.G.; methodology, S.-J.G.; validation, S.-J.G. and T.-L.Y.; investigation, S.-J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-J.G.; writing—review and editing, S.-J.G. and T.-L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22173053), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi Province (201801D121103 and 202303021212289), the Shanxi “1331” Project, and Lyuliang City High-Level Scientific and Technological Talents Project (2023RC14).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ruatta, S.A.; Hamley, L.; Anderson, S.L. Dynamics of boron cluster ion reactions with deuterium: adduct formation and decay. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 91, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boustani, I.; Quandt, A.; Hernández, E.; Rubio, A. New boron based nanostructured materials. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 3176–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J.E.; Ugalde, J.M. The curiously stable B13+ cluster and its neutral and anionic counterparts: the advantages of planarity. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihara, J. i. B13+ is highly aromatic. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 5486−5489.

- Aihara, J. i; Kanno, H.; Ishida, T. Aromaticity of planar boron clusters confirmed. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 13324–13330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.-J.; Kiran, B.; Li, J.; Wang, L.-S. Hydrocarbon analogues of boron clusters−planarity, aromaticity and antiaromaticity. Nat. Mater. 2003, 2, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.-J.; Alexandrova, A.N.; Birch, K.A.; Boldyrev, A.I.; Wang, L.-S. Hepta- and octacoordinate boron in molecular wheels of eight- and nine- atom boron clusters: observation and confirmation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 6004–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oger, E.; Crawford, N.R.M.; Kelting, R.; Weis, P.; Kappes, M.M.; Ahlrichs, R. Boron cluster cations: transition from planar to cylindrical structures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8503–8506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova, A.N.; Boldyrev, A.I.; Zhai, H.-J.; Wang, L.-S. All-boron aromatic clusters as potential new inorganic ligands and building blocks in chemistry(review). Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 2811–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-L.; Chen, Q.; Tian, W.-J.; Bai, H.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Hu, H.-S.; Li, J.; Zhai, H.-J.; Li, S.-D.; Wang, L.-S. The B35 cluster with a double-hexagonal vacancy: a new and more flexible structural motif for borophene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 12257–12260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Li, W.-L.; Jian, T.; Chen, Q.; You, X.-R.; Ou, T.; Zhao, X.-Y. Zhai, H.-J.; Li, S.-D.; Wang, L.-S. Observation and characterization of the smallest borospherene, B28− and B28. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 064307.

- Sergeeva, A.P.; Zubarev, D.Y.; Zhai, H.-J.; Boldyrev, A.I.; Wang, L.-S. A photoelectron spectroscopic and theoretical study of B16− and B162−: an all-boron naphthalene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 7244–7246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.-J.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Li, W.-L.; Chen, Q.; Bai, H.; Hu, H.-S.; Piazza, Z.A.; Tian, W.-J.; Lu, H.-G.; Wu, Y.-B.; Mu, Y.-W.; Wei, G.-F; Liu, Z.-P.; Li, S.-D.; Wang, L.-S. Observation of an all-boron fullerene. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannix, A.J.; Zhou, X.-F.; Kiraly, B.; Wood, J.D.; Alducin, D.; Myers, B.D.; Liu, X.-L.; Fisher, B.L.; Santiago, U.; Guest, J.R.; Yacaman, M.J.; Ponce, A.; Oganov, A.R.; Hersam, M.C.; Guisinger, N.P. Synthesis of borophenes: anisotropic, two-dimensional boron polymorphs. Science 2015, 350, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, Q.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Cheng, P.; Meng, S.; Chen, L.; Wu, K. Experimental realization of two-dimensional boron sheets. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-L.; Jian, T.; Chen, X.; Li, H.-R.; Chen, T.-T.; Luo, X.-M.; Li, S.-D.; Li, J.; Wang, L.-S. Observation of a metal-centered B2-Ta@B18− tubular molecular rotor and a perfect Ta@B20− boron drum with the record coordination number of twenty. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 1587–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Moreno, D.; Osorio, E.; Castro, A.C.; Pan, S.; Chattaraj, P.K.; Heine, T.; Merino, G. Structure and bonding of IrB12−: converting a rigid boron B12 platelet to a Wankel motor. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 27177–27182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, I.A.; Li, W.-L.; Piazza, Z.A.; Boldyrev, A.I.; Wang, L.-S. Complexes between planar boron clusters and transition metals: a photoelectron spectroscopy and ab initio study of CoB12– and RhB12–. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 8098–8105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Li, H.-R.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Lu, X.-Q.; Mu, Y.-W.; Lu, H.-G.; Li, S.-D. Fluxional bonds in planar B19−, tubular Ta@B20−, and cage-like B39−. J. Comput. Chem. 2018, 40, 966–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, R.-X.; Gao, S.-J.; Han, P.-F.; Zhai, H.-J. Chemical bonding and dynamic structural fluxionality of a boron-based Al2B8 binary cluster: the robustness of a doubly 6π/6σ aromatic [B8]2− molecular. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 1964–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhai, H.-J.; Li, S.-D. B11−: a moving subnanoscale tank tread. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 16054–16060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Guajardo, G.; Sergeeva, A.P.; Boldyrev, A.I.; Heine, T.; Ugalde, J.M.; Merino, G. Unravelling phenomenon of internal rotation in B13+ through chemical bonding analysis. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 6242−6244.

- Jiménez-Halla, J.O.C.; Islas, R.; Heine, T.; Merino, G. B19−: an aromatic wankel motor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5668–5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Sergeeva, A.P.; Zhai, H.-J.; Averkiev, B.B. L.; Wang, L.-S.; Boldyrev, A.I. A concentric planar doubly π-aromatic B19− cluster. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 202206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.-C.; Feng, L.-Y.; Wang, Y.-J.; Jalife, S.; Vásquez-Espinal, A.; Cabellos, J.L.; Pan, S.; Merino, G.; Zhai, H.-J. Coaxial triple-layered versus helical Be6B11− clusters: dual structural fluxionality and multifold aromaticity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10174–10177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, P.-F.; Wang, Y.-J.; Feng, L.-Y.; Gao, S.-J.; Sun, Q.; Zhai, H.-J. Chemical bonding and dynamic structural fluxionality of a boron-based Na5B7 sandwich cluster. Molecules, 2023, 28, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.-F.; Sun, Q.; Zhai, H.-J. Boron-based inverse sandwich V2B7− cluster: double π/σ aromaticity, metal−metal bonding, and chemical analogy to planar hypercoordinate molecular wheels. Molecules, 2023, 28, 4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Feng, L.-Y.; Yan, M.; Zhai, H.-J. Be3B11− cluster: a dynamically fluxional berylo-borospherene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 2846−2852.

- Yu, R.; Yan, G.-R.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Cui, Z.-H. Two-layer molecular rotors: a zinc dimer rotating over planar hypercoordinate motifs. J. Comput. Chem. 2023, 30, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Feng, L.-Y.; Xu, L.; Hou, X.-R.; Li, N.; Miao, C.-Q.; Zhai, H.-J. Boron-based ternary Rb6Be2B6 cluster featuring unique sandwich geometry and a naked hexagonal boron ring. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 20043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, P.P.; Sattelmeyer, K.W.; Saunders, M.; Schaefer III, H.F.; Schleyer, P.v.R. Mindless chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. 2006, 110, 4287–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M. Stochastic search for isomers on a quantum mechanical surface. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yañez, O.; Vásquez-Espinal, A.; Pino-Rios, R.; Ferraro, Pan, F.-S.; Osorio, E.; Merino, G.; Tiznado, W. Exploiting electronic strategies to stabilize a planar tetracoordinate carbon in cyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 12112–12115. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.A.; Figgen, D.; Goll, E.; Stoll, H.; Dolg, M. Systematically convergent basis sets with relativistic pseudopotentials. II. small-core pseudopotentials and correlation consistent basis sets for the post-d group 16−18 elements. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 11113–11123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis III, G.D.; Bartlett, R.J. A full coupled-cluster singles and doubles model: the inclusion of disconnected triples, J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 76, 1910–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: the PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuseria, G.E.; Schaefer III, H.F. Is coupled cluster singles and doubles (CCSD) more computationally intensive than quadratic configuration interaction (QCISD)? J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 3700–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.E.; Curtiss, L.A.; Weinhold, F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubarev, D.Y.; Boldyrev, A.I. Developing paradigms of chemical bonding: adaptive natural density partitioning. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 5207–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wannere, C.S.; Corminboeuf, C.; Puchta, R.; Schleyer, P.v.R. Nucleus-independent chemical shifts (NICS) as an aromaticity criterion. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3842–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klod, S.; Kleinpeter, E. Ab initio calculation of the anisotropy effect of multiple bonds and the ring current effect of arenes−application in conformational and configurational analysis. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2001, 2, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F.-W. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandeVondele, J.; Krack, M.; Mohamed, F.; Parrinello, M.; Chassaing, T.; Hutter, J. Quickstep: fast and accurate density functional calculations using a mixed gaussian and plane waves approach. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2005, 167, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. GAUSSIAN 09, Revision D.01, Gaussian, Inc. Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- Dennington, R.; Keith, T.; Millam, J. GaussView, Version 5, Semichem, Inc., Shawnee Mission, KS, 2009.

- Legault, C.Y. CYLview, 1.0b, Universitѐ de Sherbrooke. 2009. https://www.cylview.org.

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).