Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. History of Antimicrobial Drug Discovery

3. Structural Natures of Antimicrobials

4. Approaches in Antimicrobial Drug Discovery

4.1. Culture Techniques

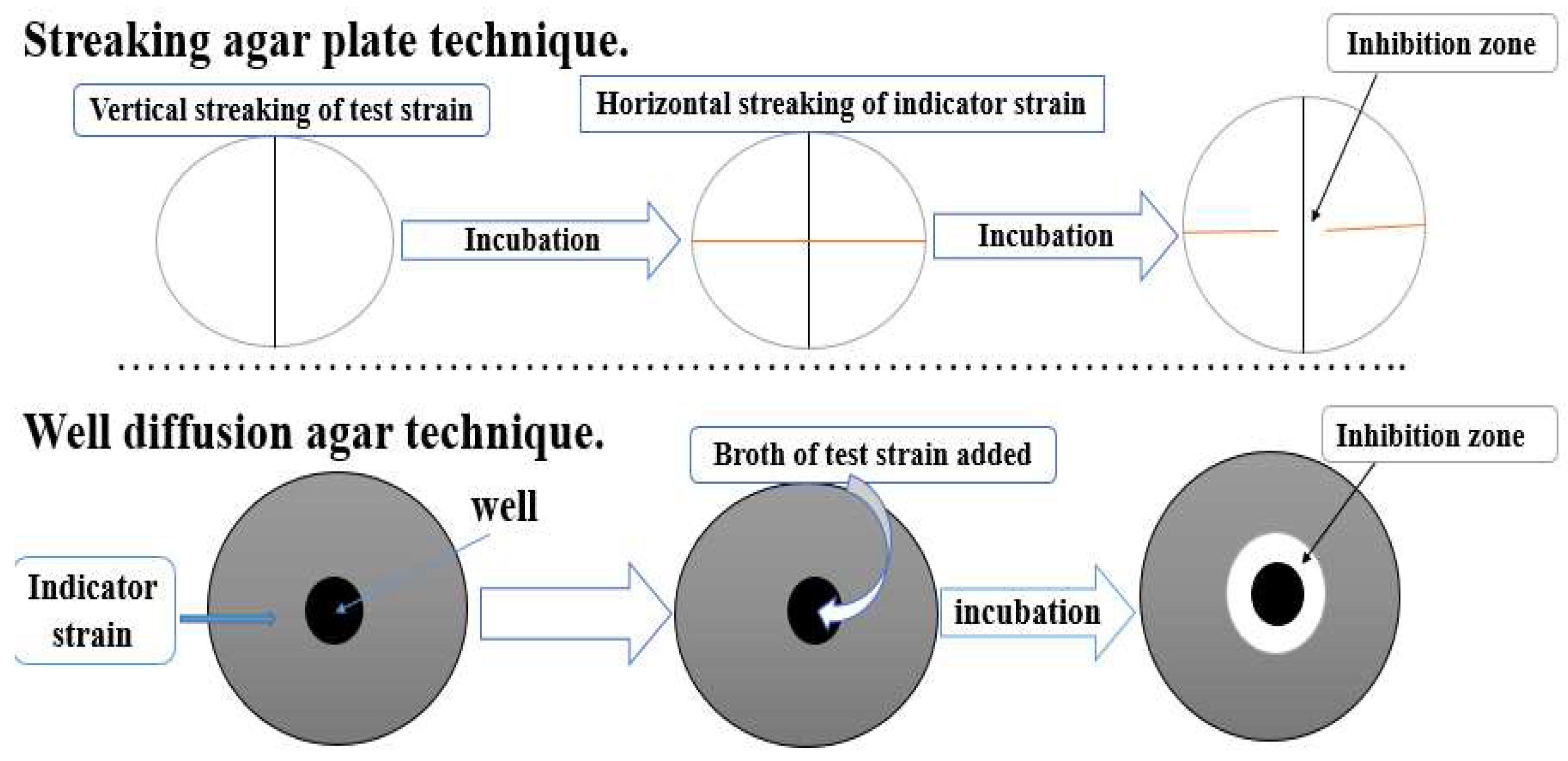

4.1.1. Streaking and Spreading Agar Plate Technique

4.1.2. Well Diffusion Agar Technique

4.2. Biochemical Modification of Already Known Molecules

4.3. Induction of Silent Genes Encoding Bioactive Molecules

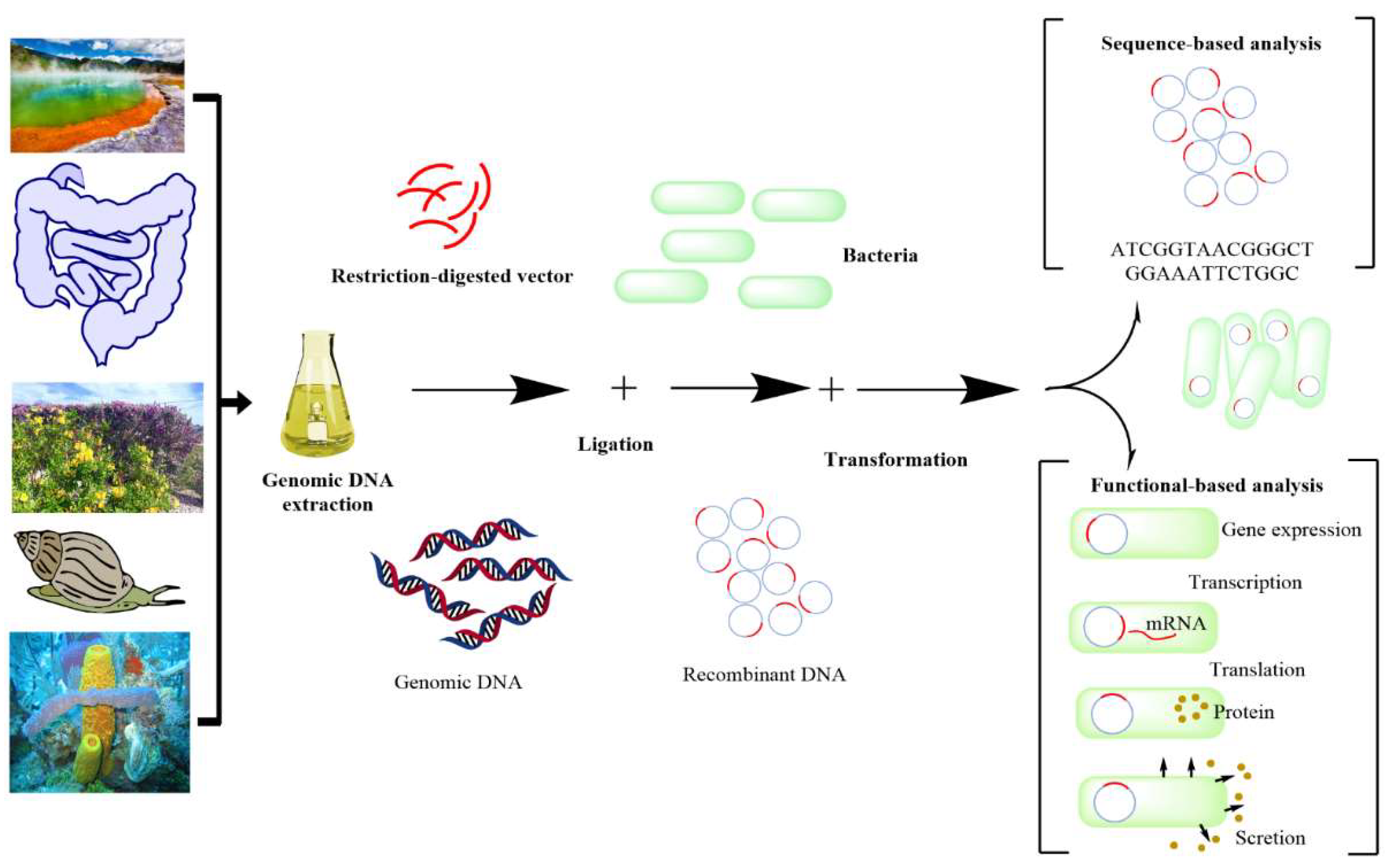

4.4. Metagenomic Tools and Uncultured Microbes

4.5. Microbiota and Bioactive Metabolites

4.6. Microbial Co-Cultivation (Mixed-Culture)

4.7. Alternative Targets for Antimicrobials Other Than Cellular Components

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Code Availability

Ethical Approval

Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

References

- Maartens MMJ, Swart CW, Pohl CH, Kock LJF. 2011. Antimicrobials, chemotherapeutics or antibiotics. Sci Res Essays. 6:3927–9.

- Seal, B.S.; Drider, D.; Oakley, B.B.; Brüssow, H.; Bikard, D.; Rich, J.O.; Miller, S.; Devillard, E.; Kwan, J.; Bertin, G.; et al. Microbial-derived products as potential new antimicrobials. Veter- Res. 2018, 49, 66. [CrossRef]

- Qurbani, K.; Hussein, S.; Ahmed, S.K. Recent meningitis outbreak in Iraq: a looming threat to public health. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Dar KB, Bhat AH, Amin S, Zargar MA, Masood A, Malik AH, et al. 2017. Evaluation of antibacterial, antifungal and phytochemical screening of Solanum nigrum. Biochem Anal Biochem. 6(309):1009–2161.

- Qurbani, K.; Hussein, S.; Ahmed, S.K.; Darwesh, H.; Ali, S.; Hamzah, H. Biosafety and biosecurity in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region: Challenges and necessities. J. Biosaf. Biosecurity 2024, 6, 65–66. [CrossRef]

- Qurbani, K.; Hussein, S.; Hamzah, H.; Sulaiman, S.; Pirot, R.; Motevaseli, E.; Azizi, Z. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles by Raoultella Planticola and Their Potential Antibacterial Activity Against Multidrug-Resistant Isolates. 2022, 20, 75–83. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.; Sulaiman, S.; Ali, S.; Pirot, R.; Qurbani, K.; Hamzah, H.; Hassan, O.; Ismail, T.; Ahmed, S.K.; Azizi, Z. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Aeromonas caviae for Antibacterial Activity and In Vivo Effects in Rats. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2023, 202, 2764–2775. [CrossRef]

- Karch AM. 2013. 2014 Lippincott’s Pocket Drug Guide for Nurses. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;

- Sherif, R.; Segal, B.H. Pulmonary aspergillosis: clinical presentation, diagnostic tests, management and complications. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2010, 16, 242–250. [CrossRef]

- Qurbani, K.; Ali, S.; Hussein, S.; Hamzah, H. Antibiotic resistance in Kurdistan, Iraq: A growing concern. New Microbes New Infect. 2024, 57, 101221. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.; Ahmed, S.K.; Qurbani, K.; Fareeq, A.; Essa, R.A. Infectious diseases threat amidst the war in Gaza. J. Med. Surg. Public Heal. 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Hussein, S.; Qurbani, K.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Fareeq, A.; Mahmood, K.A.; Mohamed, M.G. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. J. Med. Surg. Public Heal. 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill J. 2016. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations.

- Qurbani KA, Amiri O, Othman GM, Fatah AA, Yunis NJ, Joshaghani M, et al. 2024. Enhanced antibacterial efficacy through piezo memorial effect of CaTiO3/TiO2 Nano-Composite. Inorg Chem Commun. 165:112470. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, D.M.; Hassan, S.A.; Amin, A.A.M.; Abdullah, M.N.; Qurbani, K.; Aziz, S.B. Author response for "A synergistic investigation of azo-thiazole derivatives incorporating thiazole moieties: a comprehensive exploration of their synthesis, characterization, computational insights, solvatochromism, and multimodal biological activity assessment". 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kader, D.A.; Aziz, D.M.; Mohammed, S.J.; Maarof, N.N.; Karim, W.O.; Mhamad, S.A.; Rashid, R.M.; Ayoob, M.M.; Kayani, K.F.; Qurbani, K. Green synthesis of ZnO/catechin nanocomposite: Comprehensive characterization, optical study, computational analysis, biological applications and molecular docking. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 319. [CrossRef]

- Aziz D, Hassan SA, Mamand DM, Qurbani K. 2023. New azo-azomethine derivatives: Synthesis, characterization, computational, solvatochromic UV‒Vis absorption and antibacterial studies. J Mol Struct. 1284:135451.

- Bakhtyar R, Tofiq R, Hamzah H, Qurbani K. 2024. Fabricated Fusarium species-mediated nanoparticles against Gram-negative pathogen. World Acad Sci J. 7(1):1. [CrossRef]

- García-Salinas, S.; Elizondo-Castillo, H.; Arruebo, M.; Mendoza, G.; Irusta, S. Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Activity and Cytotoxicity of Different Components of Natural Origin Present in Essential Oils. Molecules 2018, 23, 1399. [CrossRef]

- Durand, G.A.; Raoult, D.; Dubourg, G. Antibiotic discovery: history, methods and perspectives. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 53, 371–382. [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Li, W. Next-Generation Drug Discovery to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2019, 44, 961–972. [CrossRef]

- Keyes K, Lee MD, Maurer JJ. 2003. Antibiotics: Mode of Action, Mechanisms of Resistance and Transfer. Microbial Food Safetry in Animal Agriculture Current Topics. ME Torrence and RE Isaacson, eds. Iowa State Press, Ames, USA;

- Bassett, E.J.; Keith, M.S.; Armelagos, G.J.; Martin, D.L.; Villanueva, A.R.; Keith Tetracycline-Labeled Human Bone from Ancient Sudanese Nubia (A.D. 350). Science 1980, 209, 1532–1534. [CrossRef]

- Playfair J. 2004. Living with Germs: In sickness and in health. Oxford University Press, USA;

- Schwartz, R.S. Paul Ehrlich’s Magic Bullets. New Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1079–1080. [CrossRef]

- Marshall Jr EK. 1939. Bacterial chemotherapy: the pharmacology of sulfanilamide. Physiol Rev. 19(2):240–69.

- Fleming, A. On the Antibacterial Action of Cultures of a Penicillium, with Special Reference to their Use in the Isolation of B. influenzae. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1929, 10, 226–236.

- Aminov, R. History of antimicrobial drug discovery: Major classes and health impact. 2016, 133, 4–19. [CrossRef]

- Waksman, S.A. Microbial Antagonisms and Antibiotic Substances. Soil Sci. 1947, 64, 433. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, D. Microbiological properties of teicoplanin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1988, 21, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. Platforms for antibiotic discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 371–387. [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Skalidis, T.; Vardakas, K.Z.; Legakis, N.J.; on behalf of the Hellenic Cefiderocol Study Group Activity of cefiderocol (S-649266) against carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria collected from inpatients in Greek hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 1704–1708. [CrossRef]

- Boman, H.G. Antibacterial peptides: basic facts and emerging concepts. J. Intern. Med. 2003, 254, 197–215. [CrossRef]

- Katz, L.; Baltz, R.H. Natural product discovery: past, present, and future. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 43, 155–176. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, G.; Beckloff, N.; Weinberg, A.; Kisich, K.O. The Roles of Antimicrobial Peptides in Innate Host Defense. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 2377–2392. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.T.; Fischbach, M.A. Natural Products Version 2.0: Connecting Genes to Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2469–2493. [CrossRef]

- Arnison, P.G.; Bibb, M.J.; Bierbaum, G.; Bowers, A.A.; Bugni, T.S.; Bulaj, G.; Camarero, J.A.; Campopiano, D.J.; Challis, G.L.; Clardy, J.; et al. Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide natural products: overview and recommendations for a universal nomenclature. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013, 30, 108–160. [CrossRef]

- Strohl, W.R. The role of natural products in a modern drug discovery program. Drug Discov. Today 2000, 5, 39–41. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, R. The soil metagenome – a rich resource for the discovery of novel natural products. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2004, 15, 199–204. [CrossRef]

- Kellenberger E. 2001. Exploring the unknown. EMBO Rep. 2(1):5–7.

- Connon, S.A.; Giovannoni, S.J. High-Throughput Methods for Culturing Microorganisms in Very-Low-Nutrient Media Yield Diverse New Marine Isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 3878–85. [CrossRef]

- Zengler, K.; Toledo, G.; Rappé, M.; Elkins, J.; Mathur, E.J.; Short, J.M.; Keller, M. Cultivating the uncultured. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 15681–15686. [CrossRef]

- Williston, E.H.; Zia-Walrath, P.; Youmans, G.P. Plate Methods for Testing Antibiotic Activity of Actinomycetes against Virulent Human Type Tubercle Bacilli. J. Bacteriol. 1947, 54, 563–568. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira L de C, Silveira AMM, Monteiro A de S, Dos Santos VL, Nicoli JR, Azevedo VA de C, et al. 2017. In silico prediction, in vitro antibacterial spectrum, and physicochemical properties of a putative bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain L156. 4. Front Microbiol. 8:876.

- Dubourg, G.; Elsawi, Z.; Raoult, D. Assessment of the in vitro antimicrobial activity of Lactobacillus species for identifying new potential antibiotics. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 46, 590–593. [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Patel, M.; Hadi, S. Functional and health promoting inherent attributes ofEnterococcus hiraeF2 as a novel probiotic isolated from the digestive tract of the freshwater fishCatla catla. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3085. [CrossRef]

- Zipperer, A.; Konnerth, M.C.; Laux, C.; Berscheid, A.; Janek, D.; Weidenmaier, C.; Burian, M.; Schilling, N.A.; Slavetinsky, C.; Marschal, M.; et al. Human commensals producing a novel antibiotic impair pathogen colonization. Nature 2016, 535, 511–516. [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, P.P.; Muriana, P.M. A Microplate Growth Inhibition Assay for Screening Bacteriocins against Listeria monocytogenes to Differentiate Their Mode-of-Action. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1178–1194. [CrossRef]

- Davies, J. How to discover new antibiotics: harvesting the parvome. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011, 15, 5–10. [CrossRef]

- Saisho, Y.; Katsube, T.; White, S.; Fukase, H.; Shimada, J. Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Tolerability of Cefiderocol, a Novel Siderophore Cephalosporin for Gram-Negative Bacteria, in Healthy Subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62. [CrossRef]

- Vickers NJ. 2017. Animal communication: when i’m calling you, will you answer too? Curr Biol. 27(14):R713–5.

- Wohlleben, W.; Mast, Y.; Stegmann, E.; Ziemert, N. Antibiotic drug discovery. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 541–548. [CrossRef]

- Hosaka, T.; Ohnishi-Kameyama, M.; Muramatsu, H.; Murakami, K.; Tsurumi, Y.; Kodani, S.; Yoshida, M.; Fujie, A.; Ochi, K. Antibacterial discovery in actinomycetes strains with mutations in RNA polymerase or ribosomal protein S12. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 462–464. [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, K.; Reynolds, K.A.; Kersten, R.D.; Ryan, K.S.; Gonzalez, D.J.; Nizet, V.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Moore, B.S. Direct cloning and refactoring of a silent lipopeptide biosynthetic gene cluster yields the antibiotic taromycin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 1957–1962. [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, P.J.; Challis, G.L. Discovery of microbial natural products by activation of silent biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 509–523. [CrossRef]

- Spohn, M.; Kirchner, N.; Kulik, A.; Jochim, A.; Wolf, F.; Muenzer, P.; Borst, O.; Gross, H.; Wohlleben, W.; Stegmann, E. Overproduction of Ristomycin A by Activation of a Silent Gene Cluster in Amycolatopsis japonicum MG417-CF17. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 6185–6196. [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Grkovic, T.; Balasubramanian, S.; Kamel, M.S.; Quinn, R.J.; Hentschel, U. Elicitation of secondary metabolism in actinomycetes. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 798–811. [CrossRef]

- Qurbani K, Hussein S, Ahmed SK. 2024. Molecular Biotechniques for the Isolation and Identification of Microorganisms.

- Charlop-Powers, Z.; Milshteyn, A.; Brady, S.F. Metagenomic small molecule discovery methods. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 19, 70–75. [CrossRef]

- Qurbani, K.; Khdir, K.; Sidiq, A.; Hamzah, H.; Hussein, S.; Hamad, Z.; Abdulla, R.; Abdulla, B.; Azizi, Z. Aeromonas sobria as a potential candidate for bioremediation of heavy metal from contaminated environments. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Courtois, S.; Cappellano, C.M.; Ball, M.; Francou, F.-X.; Normand, P.; Helynck, G.; Martinez, A.; Kolvek, S.J.; Hopke, J.; Osburne, M.S.; et al. Recombinant Environmental Libraries Provide Access to Microbial Diversity for Drug Discovery from Natural Products. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 49–55. [CrossRef]

- Handelsman, J.; Rondon, M.R.; Brady, S.F.; Clardy, J.; Goodman, R.M. Molecular biological access to the chemistry of unknown soil microbes: a new frontier for natural products. Chem. Biol. 1998, 5, R245–R249. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Jones, G.; Hunter, D. Comparison of rapid DNA extraction methods applied to contrasting New Zealand soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 2053–2059. [CrossRef]

- Knietsch, A.; Waschkowitz, T.; Bowien, S.; Henne, A.; Daniel, R. Metagenomes of Complex Microbial Consortia Derived from Different Soils as Sources for Novel Genes Conferring Formation of Carbonyls from Short-Chain Polyols on Escherichia coli. Microb. Physiol. 2003, 5, 46–56. [CrossRef]

- Majernı́k A, Gottschalk G, Daniel R. 2001. Screening of environmental DNA libraries for the presence of genes conferring Na+ (Li+)/H+ antiporter activity on Escherichia coli: characterization of the recovered genes and the corresponding gene products. J Bacteriol. 183(22):6645–53.

- Gillespie, D.E.; Brady, S.F.; Bettermann, A.D.; Cianciotto, N.P.; Liles, M.R.; Rondon, M.R.; Clardy, J.; Goodman, R.M.; Handelsman, J. Isolation of Antibiotics Turbomycin A and B from a Metagenomic Library of Soil Microbial DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 4301–4306. [CrossRef]

- Voget, S.; Leggewie, C.; Uesbeck, A.; Raasch, C.; Jaeger, K.-E.; Streit, W.R. Prospecting for Novel Biocatalysts in a Soil Metagenome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 6235–6242. [CrossRef]

- Liles, M.R.; Manske, B.F.; Bintrim, S.B.; Handelsman, J.; Goodman, R.M. A Census of rRNA Genes and Linked Genomic Sequences within a Soil Metagenomic Library. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 2684–2691. [CrossRef]

- Knietsch, A.; Bowien, S.; Whited, G.; Gottschalk, G.; Daniel, R. Identification and Characterization of Coenzyme B 12 -Dependent Glycerol Dehydratase- and Diol Dehydratase-Encoding Genes from Metagenomic DNA Libraries Derived from Enrichment Cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 3048–3060. [CrossRef]

- Quaiser, A.; Ochsenreiter, T.; Lanz, C.; Schuster, S.C.; Treusch, A.H.; Eck, J.; Schleper, C. Acidobacteria form a coherent but highly diverse group within the bacterial domain: evidence from environmental genomics. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 50, 563–575. [CrossRef]

- Leser, T.D.; Mølbak, L. Better living through microbial action: the benefits of the mammalian gastrointestinal microbiota on the host. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 2194–2206. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.; Martineau, B.; Jones, W.; Ballam, J.; Mackie, R. Characterization of Fecal Bacterial Populations in Canines: Effects of Age, Breed and Dietary Fiber. Microb. Ecol. 2002, 44, 186–197. [CrossRef]

- Salminen S, von Wright A, Morelli L, Marteau P, Brassart D, de Vos WM, et al. 1998. Demonstration of safety of probiotics—a review. Int J Food Microbiol. 44(1–2):93–106.

- McFarland L V. 2000. Normal flora: diversity and functions. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 12(4):193–207.

- Lam, Y.C.; Crawford, J.M. Discovering antibiotics from the global microbiome. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 392–393. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gutierrez, E.; Mayer, M.J.; Cotter, P.D.; Narbad, A. Gut microbiota as a source of novel antimicrobials. Gut Microbes 2018, 10, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Suneja G, Nain S, Sharma R. 2019. Microbiome: A source of novel bioactive compounds and antimicrobial peptides. Microb Divers Ecosyst Sustain Biotechnol Appl Vol 1 Microb Divers Norm Extrem Environ. :615–30.

- Mousa, W.K.; Athar, B.; Merwin, N.J.; Magarvey, N.A. Antibiotics and specialized metabolites from the human microbiota. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 1302–1331. [CrossRef]

- Donia, M.S.; Cimermancic, P.; Schulze, C.J.; Wieland Brown, L.C.; Martin, J.; Mitreva, M.; Clardy, J.; Linington, R.G.; Fischbach, M.A. A Systematic Analysis of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in the Human Microbiome Reveals a Common Family of Antibiotics. Cell 2014, 158, 1402–1414. [CrossRef]

- Pettit, R.K. Mixed fermentation for natural product drug discovery. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 83, 19–25. [CrossRef]

- Qurbani, K.; Hamzah, H. Intimate communication between Comamonas aquatica and Fusarium solani in remediation of heavy metal-polluted environments. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 1397–1406. [CrossRef]

- Netzker, T.; Fischer, J.; Weber, J.; Mattern, D.J.; König, C.C.; Valiante, V.; Schroeckh, V.; Brakhage, A.A. Microbial communication leading to the activation of silent fungal secondary metabolite gene clusters. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 299–299. [CrossRef]

- Salmon I, Bull AT. 1984. Mixed-culture fermentations in industrial microbiology.

- Smid, E.J.; Lacroix, C. Microbe–microbe interactions in mixed culture food fermentations. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, 148–154. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, K.; You, L.; Arnold, F.H. Engineering microbial consortia: a new frontier in synthetic biology. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 483–489. [CrossRef]

- Hesseltine CW. 1992. Mixed-culture fermentations. Appl Biotechnol Tradit fermented foods.

- Brakhage, A.A. Regulation of fungal secondary metabolism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 11, 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.-C.; Jensen, P.R.; Kauffman, C.A.; Fenical, W. Libertellenones A–D: Induction of cytotoxic diterpenoid biosynthesis by marine microbial competition. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 5267–5273. [CrossRef]

- Degenkolb, T.; Heinze, S.; Schlegel, B.; Strobel, G.; Gräfe, U. Formation of New Lipoaminopeptides, Acremostatins A, B, and C, by Co-cultivation ofAcremoniumsp. Tbp-5 andMycogone roseaDSM 12973. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2002, 66, 883–886. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe T, Izaki K, Takahashi H. 1982. New Polyenic Antibiotics Active Against Gram-Positive And-Negative Bacteria I. Isolation And Purification Of Antibiotics Produced By Gluconobacter sp. W-315. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 35(9):1141–7.

- Onaka, H.; Mori, Y.; Igarashi, Y.; Furumai, T. Mycolic Acid-Containing Bacteria Induce Natural-Product Biosynthesis in Streptomyces Species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 400–406. [CrossRef]

- Cueto, M.; Jensen, P.R.; Kauffman, C.; Fenical, W.; Lobkovsky, E.; Clardy, J. Pestalone, a New Antibiotic Produced by a Marine Fungus in Response to Bacterial Challenge. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1444–1446. [CrossRef]

- Marmann, A.; Aly, A.H.; Lin, W.; Wang, B.; Proksch, P. Co-Cultivation—A Powerful Emerging Tool for Enhancing the Chemical Diversity of Microorganisms. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1043–1065. [CrossRef]

- Park HB, Kwon HC, Lee C-H, Yang HO. 2009. Glionitrin A, an antibiotic− antitumor metabolite derived from competitive interaction between abandoned mine microbes. J Nat Prod. 72(2):248–52.

- Payne, D.J.; Gwynn, M.N.; Holmes, D.J.; Pompliano, D.L. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 6, 29–40. [CrossRef]

- Clatworthy, A.E.; Pierson, E.; Hung, D.T. Targeting virulence: a new paradigm for antimicrobial therapy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 541–548. [CrossRef]

- Rasko, D.A.; Moreira, C.G.; Li, D.R.; Reading, N.C.; Ritchie, J.M.; Waldor, M.K.; Williams, N.; Taussig, R.; Wei, S.; Roth, M.; et al. Targeting QseC Signaling and Virulence for Antibiotic Development. Science 2008, 321, 1078–1080. [CrossRef]

- Negrea, A.; Bjur, E.; Ygberg, S.E.; Elofsson, M.; Wolf-Watz, H.; Rhen, M. Salicylidene Acylhydrazides That Affect Type III Protein Secretion inSalmonella entericaSerovar Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 2867–2876. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-I.; Liu, G.Y.; Song, Y.; Yin, F.; Hensler, M.E.; Jeng, W.-Y.; Nizet, V.; Wang, A.H.-J.; Oldfield, E. A Cholesterol Biosynthesis Inhibitor Blocks Staphylococcus aureus Virulence. Science 2008, 319, 1391–1394. [CrossRef]

- Su Z, Honek JF. 2007. Emerging bacterial enzyme targets. Curr Opin Investig drugs (London, Engl 2000). 8(2):140–9.

- Schimmel, P.; Tao, J.; Hill, J. Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases as targets for new anti-infectives. FASEB J. 1998, 12, 1599–1609. [CrossRef]

- Lock, R.L.; Harry, E.J. Cell-division inhibitors: new insights for future antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 324–338. [CrossRef]

- Njoroge, J.; Sperandio, V. Jamming bacterial communication: New approaches for the treatment of infectious diseases. EMBO Mol. Med. 2009, 1, 201–210. [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, Y.; Eguchi, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Okamoto, S.; Doi, A.; Utsumi, R. Two-component signal transduction as potential drug targets in pathogenic bacteria. 2010, 13, 232–239. [CrossRef]

- Diacon, A.H.; Pym, A.; Grobusch, M.; Patientia, R.; Rustomjee, R.; Page-Shipp, L.; Pistorius, C.; Krause, R.; Bogoshi, M.; Churchyard, G.; et al. The Diarylquinoline TMC207 for Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. New Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 2397–2405. [CrossRef]

- Lomovskaya, O.; Bostian, K.A. Practical applications and feasibility of efflux pump inhibitors in the clinic—A vision for applied use. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 71, 910–918. [CrossRef]

- Bush K, Macielag MJ. 2010. New β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 20(10):1277–93.

- Devasahayam, G.; Scheld, W.M.; Hoffman, P.S. Newer antibacterial drugs for a new century. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2010, 19, 215–234. [CrossRef]

- Kohanski, M.A.; Dwyer, D.J.; Collins, J.J. How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 423–435. [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.K.; Collins, J.J. Engineered bacteriophage targeting gene networks as adjuvants for antibiotic therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 4629–4634. [CrossRef]

| Classes | Antibiotics | Years of Discovery | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Β-Lactams | Penicillin Carbapenem Cephalosporin |

1928 1976 1948 |

Penicillium notatum, Penicillium chrysogenum Streptomyces cattleya Cephalosporium acremonium |

| Carboxylic acid | Mupirocin | 1971 | Pseudomonas fluorescens |

| Chloramphenicol | Chloramphenicol | 1946 | Streptomyces venezuelae |

|

Glycopeptides |

Teicoplanin Vancomycin |

1978 1953 |

Actinoplanes teichomyceticus Amycolatopsis orientalis |

| Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin Kanamycin Natamycin Neomycin Streptomycin |

1963 1957 1957 1949 1943 |

Micromonospora purpurea Streptomyces kanamyceticus Streptomyces natalensis Streptomyces fradiae Streptomyces griseus |

| Macrolides | Erythromycin Spiramycin Fidaxomicin |

1948 1952 1975 |

Streptomyces erythraeus Streptomyces ambofaciens Dactylosporangium aurantiacum |

| Lipopeptides: | Daptomycin | 1986 | Streptomyces roseosporus |

| Polypeptides: | Polymyxin | 1947 | Paenibacillus polymyxa |

| Rifamycins: | Rifampicin | 1957 | Streptomyces mediterranei |

| Sulfonamides: | Sulfamethoxazole | 1961 | Synthetic |

| Tetracyclines: | Chlortetracycline Tigecycline |

1948 1999 |

Streptomyces aureofaciens Synthetic |

| Nitroimidazoles: | Metronidazole | 1960 | Streptomyces spp. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).