a. Introduction

The advancement of technology is revolutionizing the way of teaching and learning science. In this view, virtual learning tools, such as dynamic simulations, are increasingly becoming popular, especially in various scientific disciplines, such as biology, physics, chemistry, among others (Navarro et al., 2024). Dynamic simulations seem to mainly be used to carry out highly complex and/or dangerous experiments or these which are impossible to perform in a physical laboratory (Ndihokubwayo, 2017). Moreover, they alleviate the time and effort which would be required to conduct the required experiments compared to physical laboratories (Roschelle et al., 2000). Dynamic simulations are thus used as an alternative to physical laboratories and provide to students the opportunity to interact with the science concepts they learn (Moore et al., 2013).

While emphasizing on the importance of utilizing computer simulations in the practical aspects of teaching kinetic chemical principles, research demonstrated that simulations significantly enhance the learning experience during the teaching process. They provide students with opportunities to develop new skills and capabilities in order to foster a dynamic environment that optimizes interaction and interactivity within a school setting (Daaif et al., 2019). It has been shown that students taught using computer simulation had significantly better performance and higher-order cognitive achievement in chemistry than their counterparts who were taught with the traditional lecture method at the Senior Secondary School level (Gambari et al., 2016; Uzezi & Deya, 2020; Oladejo, Akinola, & Nwaboku, 2021). Employing dynamic simulations in teaching and learning science is highly beneficial for educators and learners, despite encountering various challenges that impede their classroom implementation. Thus, integrating interactive simulations into science education could enrich learning experiences and facilitate effective comprehension of scientific concepts among students (Ben Ouahi, 2022).

However, simulations are relatively new in Rwanda schools (Tuyizere & Yadav, 2023). Few studies have been conducted to explore the usefulness of simulations in teaching and learning chemistry. The study conducted in Gicumbi District demonstrated that the integration of computer-based simulations in teaching and learning chemistry units leads to significantly high average scores, increased motivation, positive attitudes, and enhanced understanding among students (Nsabayezu et al., 2023; Nsabayezu et al., 2024). The study conducted in Western Province secondary schools revealed that computer simulations contribute to engaging students’ active participation in knowledge creation in chemistry (Mukama & Byukusenge, 2023). Students also highly value the use of Interactive Computer Simulations (ICSs) in teaching and learning chemistry. Their perceptions regarding the intention to use computer simulations, actual usage, ease of use, and perceived usefulness are notably influenced by their pre-existing knowledge and self-confidence in using computers (Batamuliza, Habinshuti & Nkurunziza, 2024).Thus, Rwandan teachers seem to be not yet familiar with their use. Furthermore, Rwandan teachers’ perceptions on the use of dynamic simulations is not yet reported.

Even though Rwanda and many other countries have understood the importance of integration of ICT in their education system, teachers are still facing several difficulties to use dynamic simulations associated with their low skills to integrate technology into their lessons (Erdem, 2019; Ghavifekr & Rosdy, 2015). The researchers reported several barriers mainly associated to difficulties to integrate technology in teaching their science subjects (Ghavifekr & Rosdy, 2015), including lack of adequate materials within schools, teachers' lack of enough ICT skills, pressing mindset that the use of dynamic simulations impedes teaching and learning, among others (Bo et al., 2018).

Although several studies reported the use of dynamic simulations in teaching and learning science (Ben Ouahi et al., 2021; Droui & El Hajjami, 2014; Nafidi et al., 2018), no studies has yet covered the views of Rwanda chemistry teachers on the use of dynamic simulations in teaching and learning chemical kinetics, one of the most abstract chemistry topics. The purpose of the current research is, thus, to collect perceptions of Kigali city secondary schools’ chemistry teachers on the use of dynamic simulations in teaching and learning Chemical Kinetics. It focuses on teachers' interest in using dynamic simulations in teaching and learning chemical kinetics and teachers’ view on the worthiness of dynamic simulations in teaching the same chemistry content.

The current study aimed at exploring chemistry teachers’ perceptions of the useful and integration of dynamic simulations in teaching and learning of chemical kinetics.

b. Literature Review

Simulation is defined as a technique replacing or amplifying real experience that evokes or replicates substantial aspects of the real world in a fully interactive manner (Gaba, 2004). In this regard, in some countries, simulations and virtual laboratories have gained popularity due to their effectiveness in teaching challenging science subjects (Babateen, 2011). In this regard, science simulations and virtual labs have been increasingly incorporated into educational settings as a promising method to supplement traditional hands-on laboratory practices (Keller & Keller, 2005; Mahmoud & Zoltan, 2009). While investigating the relationship between students’ engagement and satisfaction with simulation-based learning, and their learning styles, the results indicated that participants expressed high levels of engagement and satisfaction when using simulations to learn science concepts in physics, chemistry, and biology. In addition, their self-confidence and preferred learning styles significantly predicted their engagement and satisfaction during the learning process. Therefore, simulations are considered as a pedagogical tool to enhance practical experience in science education (Almasri, 2022).

Virtual laboratories are proposed as a complement to physical labs, offering a solution to enhance practical experience in STEM education by allowing students to conduct experiments without constraints of time, space, or safety hazards. Integrating virtual laboratories into educational practices is seen as a crucial step in modernizing teaching methodologies and providing students with access to high-quality educational resources.

Literatures report that the use of dynamic simulations in teaching and learning sciences is very useful to both students and teachers, irrespective of numerous barriers that interfere with their use in classroom activities (Bo et al., 2018). During the research conducted about teaching and learning science in Morocco, the teachers’ views reported that dynamic simulations can help students to understand scientific concepts effectively, and thus enhance learning activities (Ben Ouahi et al., 2022).

The dynamic simulations help both teachers and students to visualize things that were not visible like electrons and atoms (Wieman et al., 2013). Dynamic simulations are designed for the students to achieve learning outcomes. Thus, teachers and students are encouraged to use them to explore science physical phenomena, especially those which are difficult to visualize through physical laboratory activities or those which are dangerous to physically visualize (Wieman & Perkins, 2006).

Even though dynamic simulations are proved so useful, research reports that their implementation in teaching and learning sciences is still challenging and slow (Brenner & Brill, 2016). The reasons include teacher-focused, learner-focused; situation-focused, and curriculum focused challenges that can be seen via limited teachers and students’ ICT skills, school infrastructure, software access, and technical support (Errington, 2011). To be able to effectively use dynamic simulations in teaching and learning sciences, the researchers are recommending to solve the pedagogical and technological issues by increasing teachers training (Brenner & Brill, 2016).

c. Methodology

The present section provides a detailed account of the methodology used to answer the current research questions. It covers the research design and describes participants, sampling methods, research instruments, data analysis, validity and reliability of data, and ethical considerations.

Research Design

The convergent parallel design was considered appropriate for evaluating teachers' perceptions on the integration of dynamic simulation in teaching and learning chemical kinetics. Within this design, mixed-method approaches integrating both quantitative and qualitative data to provide a comprehensive understanding of the teachers' perceptions were used. This methodology provided the flexibility to incorporate numerical and textual data for depicting teachers’ perspectives on the subject (Creswell & Clark, 2017).

Figure 2.

Convergent parallel design (Adapted from Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011).

Figure 2.

Convergent parallel design (Adapted from Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011).

Location of the Study, Sampling, and Participants

The current study was conducted in Kigali city secondary schools. Purposive sampling was employed to guarantee that all participants possess pertinent information regarding the research topic. Thus, participants to the current research were selected from upper-level secondary schools having combinations with chemistry as one of the major subjects. They included a total of 60 chemistry teachers in upper level of secondary school.

Data Collection Instruments

In this study, the research team developed a questionnaire which was validated by experts from University of Rwanda-College of Education. The purpose of the instrument was to investigate chemistry teachers' perceptions on the usefulness and integration of dynamic simulations in the teaching of chemical kinetic concepts. The questionnaire comprises four main sections: The first section contains items on teachers’ perceptions on the effectiveness of dynamic simulations’ uses in teaching chemical kinetics. The second explores teachers' views on the effect of dynamic simulations on students' understanding and retention of chemical kinetics concepts. The third section highlights the barriers hindering chemistry teachers from fully integrating dynamic simulations into chemical kinetics teaching, while the fourth section examines the supports needed for effective use of dynamic simulations in teaching chemical kinetics.

Data Analysis

The quantitative data underwent descriptive statistical analysis using Excel, and the findings were presented using bar diagrams and pie charts. For the qualitative data, the analysis was conducted using the Taguette tool (Rampin R, 2020), following the six-step: (1) familiarization, (2) coding, (3) generating themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) writing up (Jugder (2016) and Caulfield (2019)). Thematic analysis was employed to identify recurring themes and patterns in the interview transcripts, and the results were presented using an interpretative approach

Validity and Reliability

The content validity of the research instruments was achieved through the experts’ reviews. To ensure data reliability, the pilot studies using the questionnaire survey and interview questions were conducted with a small group of teachers to ensure clarity and relevance. Triangulation method using multiple data sources (surveys, interviews) was used to strengthen the validity and reliability of findings.

Ethical Considerations

Prior to commencing this research, ethical clearance was obtained from the Research and Ethics Screening Committee (RESC) at the University of Rwanda - College of Education. In addition, all the participants signed an informed consent ensuring they understand the study's purpose and their right to withdraw at any time. To uphold anonymity and confidentiality, participants and school names were anonymized using codes.

c. Results & Discussion

The questionnaire focused on four main aspects: 1) Teachers' interest in using dynamic simulations in teaching chemical kinetics, 2) Teachers' perceptions towards dynamic simulations in teaching and learning, and 3)Worthiness of dynamic simulations in teaching chemical kinetics. 4) Improving the teaching of chemical kinetics in the advanced level of secondary school

The questions asked to collect data were measured with a Likert scale containing five levels. Each level was given a numeric value to facilitate data presentation, analysis and frequency.

Table 1 and Table 2 contain the computed mean of all participants from 13 secondary school based in Kigali City for the aspect (2) Teachers' perceptions towards dynamic simulations in teaching and learning, and (4) improving the teaching of chemical kinetics in the Advanced Level of Secondary School. The last aspect, pie chart was used for (1) teachers’ interest in using dynamic simulations in teaching chemical kinetics (3)"Worthiness of dynamic simulations in teaching chemical kinetics," included an open-ended section. In this section, students were asked to provide suggestions to improve the teaching of this subject.

Table 3 shows the representative excerpts from the students' suggestions regarding the teaching of action research online.

Tentative Research Questions

How do Chemistry teachers perceive the effectiveness of dynamic simulations in teaching Chemical Kinetics?

How do Chemistry teachers perceive the effect of dynamic simulations on students' understanding and retention of Chemical Kinetics concepts?

What barriers prevent Chemistry teachers from fully integrating dynamic simulations into their Chemical Kinetics curriculum?

What types of support do chemistry teachers believe are necessary to effectively use dynamic simulations in teaching Chemical Kinetics?

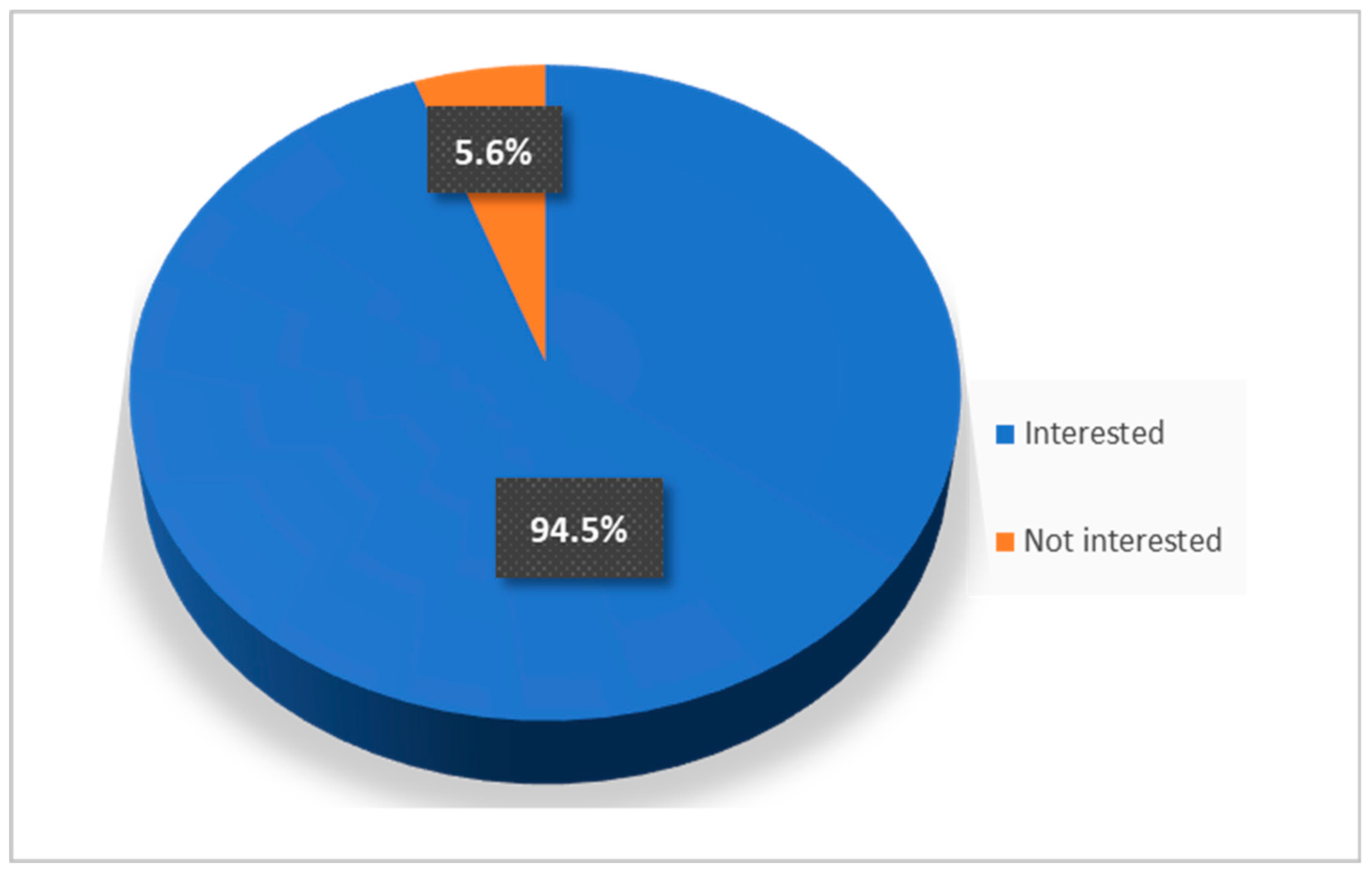

1. Teachers' Interest in Using Dynamic Simulations in Teaching Chemical Kinetics

The present study explored the teachers’ interest in using dynamic simulations in teaching and learning chemical kinetics in advanced levels of secondary schools in Kigali city.

The results showed that almost all teachers (94.5%) who participated in the study are interested in incorporating DS in teaching and learning of chemical kinetics concepts while only5.6% were not interested. These few teachers who did not show any interest mentioned some hindering factors such as technical issues and accessibility, the cost including licensing fees, maintenance and upgrade among others factors.

Figure.

Teachers’ interest in incorporating dynamic simulation in teaching and learning chemical kinetics.

Figure.

Teachers’ interest in incorporating dynamic simulation in teaching and learning chemical kinetics.

Teachers' interest in using dynamic simulations (DS) in teaching chemical kinetics is often driven by the potential benefits these tools offer mainly in visualization of abstract concepts. The adoption of online DS in teaching and learning chemistry has made the comprehension of various abstract concepts easy, especially in schools with scarcity of laboratory apparatus and equipment (Herga et al.; 2016). The majority of teachers who participated in this study confirmed that the dynamic simulations allow them to concretize some realities which normally appear as abstracts in the minds of students. This improves the extent to which students comprehend and internalize chemical kinetics concepts. This is in agreement with the findings of other numerous studies (Hartley et al., 1988; Baker, 1991; Lowe, 2012) who demonstrated the value of using online simulations in science education, highlighting their role as an interactive communication tool that allows access to various types of information, including texts, images, data, and graphics. In a similar study, Ben et al. (2022), while investigating the views of teachers on effectiveness of dynamic simulations used in teaching in Morocco, revealed that all teachers in are much interested in online simulations because they are effective for both teachers and students. The above findings are comparable to the results of the present study where participants (94.5%) confirmed that they are interested in dynamic simulations. Even though this study did not involve students, there is no doubt that if simulations help teachers effectively deliver chemical kinetics lessons, students also, directly or indirectly, benefit from simulations.

2. Teachers' Perceptions Towards Dynamic Simulations in Teaching and Learning

Most educators view dynamic simulations (DS) in teaching and learning as beneficial, and they are aware of the various advantages these resources offer to the classroom. The

Table 1 shows different benefits and values of using DS in their schools.

Animation, text, audio, video, slideshows, and simulations are all examples of multimedia. The study of McGarr, O. (2020) documented that multimedia has a positive influence on the effectiveness of the Internet.

Table 1 shows that a high number of teachers (77.8%) believe that the adoption of the use of dynamic simulations in their teaching and learning practices enhances student engagement. Similarly to a considerable extent (72.2%) who expressed that DS could provide a visual representation of abstracted concepts if it is well designed and integrated with the existing curriculum. This is supported by their colleagues (66.7%) who reported respectively that 1) DS facilitates the experimentation without lab equipment, and 2) performs the experiment on time. The average (50%) of teachers highlighted that using DS facilitates the learners to grasp the concept faster than using traditional teaching methods. This is supported by Mhamed et. al, (2021) documented that simulations have a positive impact on the performance of the students to refine their understanding (a cognitive process essential for improving skills application) and therefore enabled them to overcome certain learning difficulties. The study of Addis (2021) suggested that simulation is a general capacity that underpins other domains of cognition, such as the perception of ongoing experience. Almost half of the participants (44.4%) expressed that DS could support data analysis and interpretation of learners' performance in chemical experiments. Chang, et al., (2019) documented that students who learn using dynamic simulations perform better than those with traditional methods of teaching. This is supported by 5.6% of teachers who say the use of DS also develops in-depth thinking of learners.

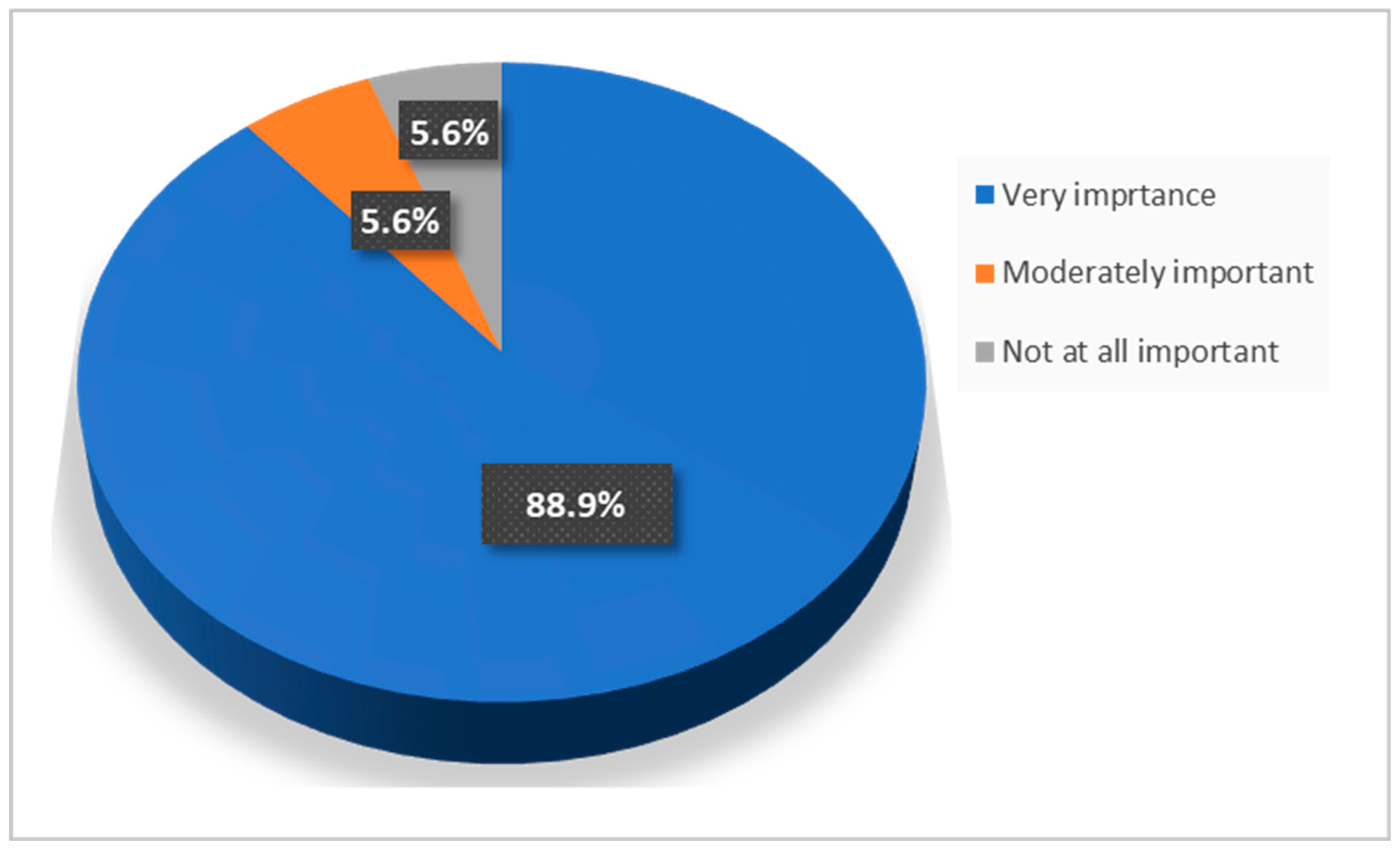

3. Worthiness of Dynamic Simulations in Teaching Chemical Kinetics

The current study results show that 88.9% of the respondents corroborate that the dynamic simulations (DS) are very important teaching and learning tools. On this, 5.6 % of chemistry teachers found DS moderately important while 5.6 % reported that they are not at all important as shown in Figure….... From these testimonies of the majority of teachers, the DS tool is a worthy approach in teaching chemical kinetics (CK) because it enhances understanding of the concepts for the students via visualization, interaction and real-time feedback.

This is supported by one teacher who said:

I use simulations to demonstrate how molecules are moving in a gaseous phase. What I did, was I browsed a simulation and showed them how particles are moving. I found that simulation when applied to a specific topic can enhance understanding of the concept you teach learners.

In addition, the DSs link the gap between theoretical concepts and experimental observations, causing CK to be more attainable and increasing interest for students. Another study conducted by Sweeder et al., (2019) also demonstrated that visualizations are able to describe how particles interact to produce successful reactions.

Figure 1.

Importance of dynamic simulations in teaching chemical kinetics.

Figure 1.

Importance of dynamic simulations in teaching chemical kinetics.

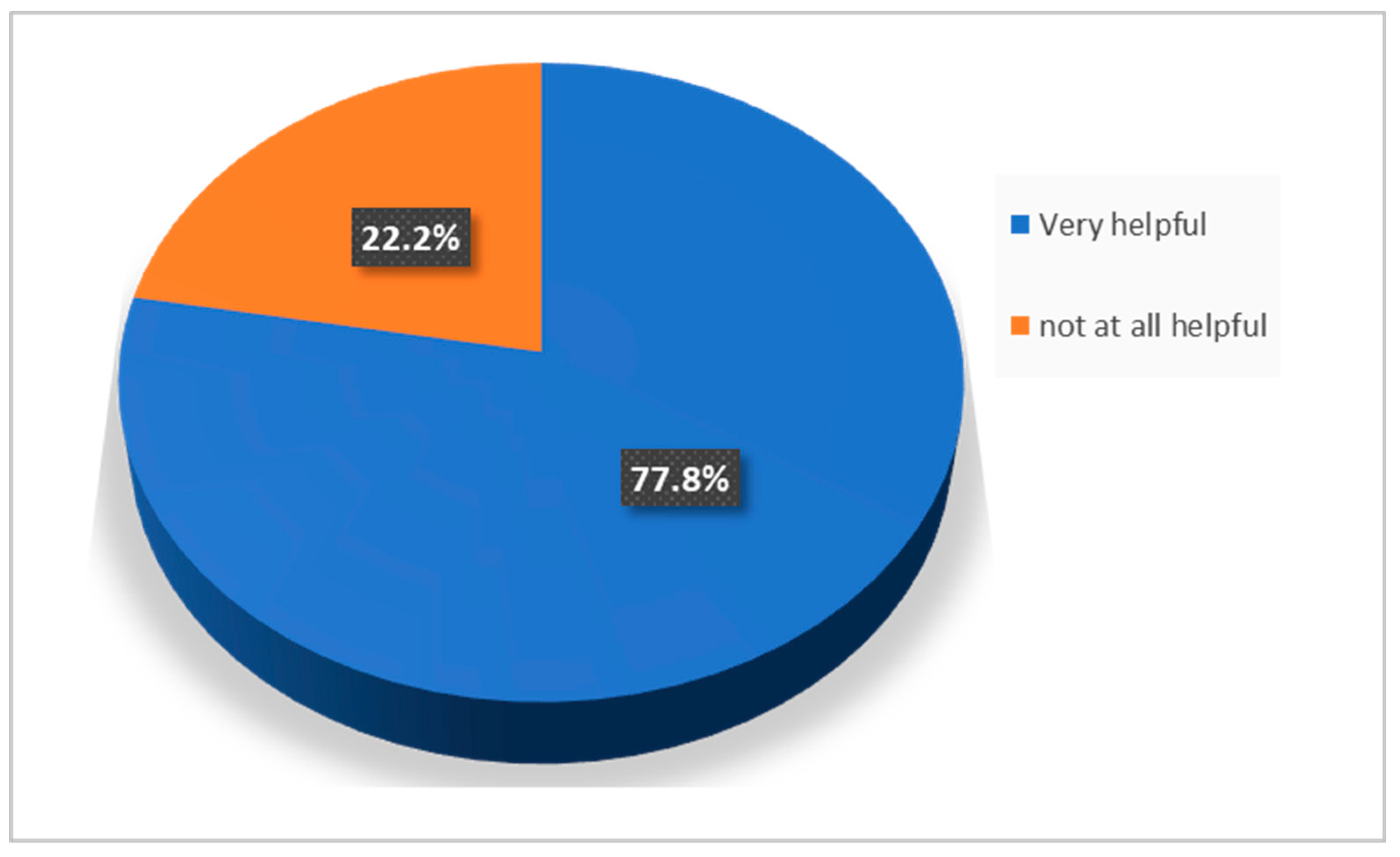

Through the investigation conducted during our research, 77.8 % of chemistry teachers confirm that teaching chemical kinetics by using dynamic simulations tools are very helpful while 22.2 % do not value their uses as depicted in Figure …… These results are in agreement with the findings in a similar study by Cruz and his co-workers about chemical kinetics simulators who concluded that simulations are helpful in teaching (Cruz et al.2020). As the majority participants explain, the DSs tool plays a crucial importance in delivering chemical kinetics lessons.

Figure 2.

Helpfulness of dynamic simulations (DSs) in teaching chemical kinetics concepts.

Figure 2.

Helpfulness of dynamic simulations (DSs) in teaching chemical kinetics concepts.

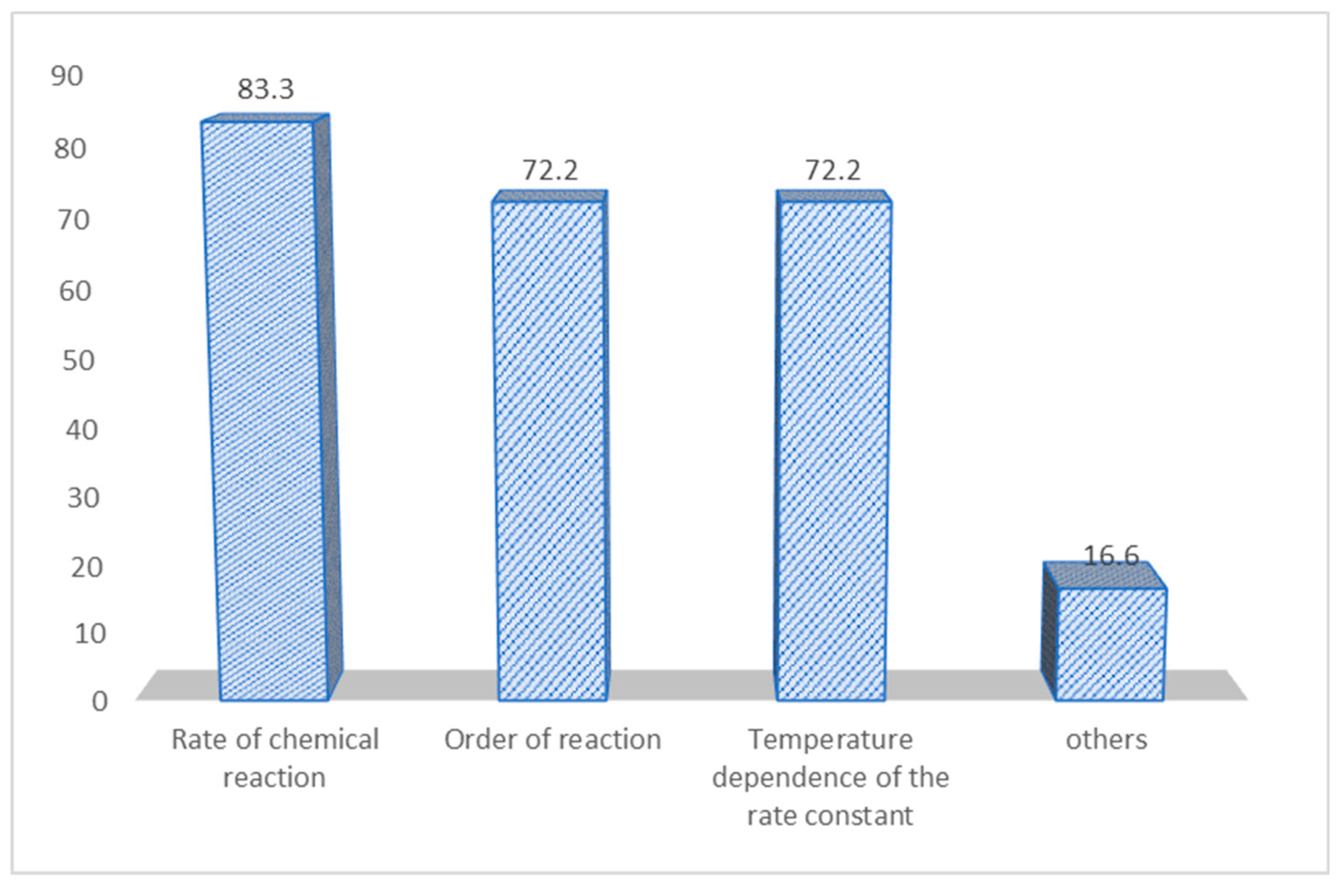

4. Improving the Teaching of Chemical Kinetics in the Advanced Level of Secondary School

Figure 3.

Improving the teaching of chemical kinetics in the advanced level of secondary school.

Figure 3.

Improving the teaching of chemical kinetics in the advanced level of secondary school.

Teachers in Kigali city have scanned through the chemical kinetics concepts and confirmed that many of them can be taught using dynamic simulations. The figure above (Fig no.) shows that 83.3 % of teachers found that dynamic simulations can be used to engage students actively while teaching the rate of chemical reaction. In addition, 72.2% of the interviewed teachers confirmed that the dynamic simulations (DSs) can be used to teach the order of reaction and temperature dependence of the rate constant concepts. Furthermore, the 16.6 % of teachers have mentioned other various chemical kinetics topics which can be handled using dynamic simulations (DSs) to be added.

Teaching of chemical kinetics concepts for students at secondary and university is mostly dominated by teachers/Lecturers while the students are passive during the lesson (Chairam et al., 2009). In addition, other researchers found that chemical kinetics concepts are difficult topics to teach for students due to their complexity (Chairman and Klahan, 2015).

Yet it is the laboratory work which allows students to engage actively in the lesson, and is recognized as an essential component of science education, utilized to achieve a range of cognitive, practical, and emotional objectives (Chairam et al. 2015). Even though chemical kinetics concepts are difficult to teach for teachers and to learn for students, research works found that using dynamic simulations as teaching tools should help teachers to teach them, while dynamic simulations help students to be more engaged, motivated as well as easily comprehensible and facile visualization of the molecules interaction. Both motivation and students engagement are not only to help students to build new knowledge but also ameliorates students’ understanding of the concepts being learned at the cognitive level (Almasri et al.,2022).

The findings presented in the Figure…. are similar to the results obtained in other studies (Xie and Tinker, 2006, Zewail-Foote et al., 2019, Penn and Ramnarain, 2019). Another study shows that the incorporation of dynamic simulations (DSs) in learning improves students’ learning of chemistry concepts in the complex environment (Plass et.al., 2012). Looking at the above studies, it can be concluded that, teachers from Kigali city as well as teachers from elsewhere confirm that the use of DSs can help both teachers and students in teaching and learning of chemical kinetics in particular and chemistry in general. Therefore DSs can be used for teaching concepts or as a complementary tool to enhance student understanding after conventional chemistry practical (Penn and Ramnarain, 2019).

d. Conclusion & Recommendations

The results from this research shows that the use of dynamic simulations in teaching chemical kinetics offers substantial benefits to enhance students’ understanding. In this regard, the 77.8% of chemistry teachers that participated to this research agreed that using dynamic simulation tools to teach chemical kinetics is very beneficial as they provide visual and interactive representations of abstract concepts. Despite some challenges such as technical information technology skills and access to DS resources, the overall consensus supports their integration as valuable teaching and learning aids in modern chemistry education. Indeed, findings show that 83.3% of teachers found dynamic simulations effective for engaging students in learning the rate of chemical reactions.

Based on the positive perception of chemistry teachers regarding the use of DS in teaching chemical kinetics, it is recommended that educational institutions integrate these tools into the curriculum to enhance student engagement and understanding. Professional development programs should be provided to equip teachers with the skills needed to effectively use dynamic simulations. Additionally, resources should be allocated to ensure teachers have access to the necessary technology. Schools should also encourage the use of dynamic simulations to cover a broader range of chemical kinetics topics and regularly assess their impact on student learning outcomes, fostering a collaborative environment where teachers can share best practices and innovations.

e. Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge financial support from University of Rwanda, College of Education in partnership with the MasterCard Foundations through Leaders In Teaching (LIT) project. They are also thankful to the Directorate of Research and Innovation for providing a Research Ethical clearance, and to all respondents who participated in the study.

References

- Mukama, E.; Byukusenge, P. Supporting Student Active Engagement in Chemistry Learning with Computer Simulations. J. Learn. Dev. 2023, 10, 427–439. [CrossRef]

- Nsabayezu, E., Hakizimana, V. E., Manizabayo, P., Wencesla, O. H., & Niyonzima, N. F. N. (2024). Contribution of Computer-Assisted Simulation on Students’ Learning of Chemical Bonding in selected secondary Schools of Rwanda. African Journal of Education, 7(4), 124.

- Nsabayezu, E.; Iyamuremye, A.; Mukiza, J.; Mbonyiryivuze, A.; Gakuba, E.; Niyonzima, F.N.; Nsengimana, T. Impact of computer-based simulations on students’ learning of organic chemistry in the selected secondary schools of Gicumbi District in Rwanda. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 28, 3537–3555. [CrossRef]

- Gambari, I.A.; Gbodi, B.E.; Olakanmi, E.U.; Abalaka, E.N. Promoting Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation among Chemistry Students using Computer-Assisted Instruction. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2016, 7, 25–46. [CrossRef]

- Uzezi, J. G., & Deya, G. D. (2020). Effect of Computer Simulation on Secondary School Students’ Academic Achievement in Acid-Base Reactions. ATBU Journal of Science, Technology and Education, 8(1), 286-295.

- Oladejo, A. I., Akinola, V. O., & Nwaboku, N. C. (2021). Teaching chemistry with computer simulation: Would senior school students perform better. Crawford journal of multidisciplinary research, 2(2), 16-32.

- Ben Ouahi, M.; Lamri, D.; Hassouni, T.; Al Ibrahmi, E.M. Science Teachers' Views on the Use and Effectiveness of Interactive Simulations in Science Teaching and Learning. Int. J. Instr. 2022, 15, 277–292. [CrossRef]

- Daaif, J., Zerraf, S., Tridane, M., Chbihi, M. E. M., Moutaabbid, M., Benmokhtar, S., & Belaaouad, S. (2019). Computer Simulations as a Complementary Educational Tool in Practical Work: Application of Monte-Carlo Simulation to Estimate the Kinetic Parameters for Chemical Reactions. J. Multim. Process. Technol., 10(3), 104-111.

- Navarro, C.; Arias-Calderón, M.; Henríquez, C.A.; Riquelme, P. Assessment of Student and Teacher Perceptions on the Use of Virtual Simulation in Cell Biology Laboratory Education. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 243. [CrossRef]

- Ndihokubwayo, K. (2017). Investigating the status and barriers of science laboratory activities in Rwandan teacher training colleges towards improvisation practice. 4(1), 47–54.

- Moore, E.B.; Herzog, T.A.; Perkins, K.K. Interactive simulations as implicit support for guided-inquiry. Chem. Educ. Res. Pr. 2013, 14, 257–268. [CrossRef]

- Ghavifekr, S.; Rosdy, W.A.W. Teaching and Learning with Technology: Effectiveness of ICT Integration in Schools. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2015, 1, 175. [CrossRef]

- Bo, W.V.; Fulmer, G.W.; Lee, C.K.-E.; Chen, V.D.-T. How Do Secondary Science Teachers Perceive the Use of Interactive Simulations? The Affordance in Singapore Context. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2018, 27, 550–565. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A.; Simpson, Z.B.; Blom, T. FitSpace Explorer: An algorithm to evaluate multidimensional parameter space in fitting kinetic data. Anal. Biochem. 2008, 387, 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A.; Simpson, Z.B.; Blom, T. Global Kinetic Explorer: A new computer program for dynamic simulation and fitting of kinetic data. 2008, 387, 20–29. [CrossRef]

- Zewail-Foote, M.; Venters, J.R.; Johnson, K.A. Teaching Chemical Kinetics with Dynamic Simulations. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 278–281. [CrossRef]

- Roschelle, J.M.; Pea, R.D.; Hoadley, C.M.; Gordin, D.N.; Means, B.M. Changing How and What Children Learn in School with Computer-Based Technologies. Futur. Child. 2000, 10, 76–101. [CrossRef]

- Erdem, A. A Study on Teachers’ Views on the Use of Technology to Improve Physics Education in High Schools. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2019, 7, 142–153. [CrossRef]

- Ghavifekr, S.; Rosdy, W.A.W. Teaching and Learning with Technology: Effectiveness of ICT Integration in Schools. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2015, 1, 175. [CrossRef]

- Bo, W.V.; Fulmer, G.W.; Lee, C.K.-E.; Chen, V.D.-T. How Do Secondary Science Teachers Perceive the Use of Interactive Simulations? The Affordance in Singapore Context. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2018, 27, 550–565. [CrossRef]

- Ben Ouahi, M.; Hou, M.A.; Bliya, A.; Hassouni, T.; Al Ibrahmi, E.M. The Effect of Using Computer Simulation on Students’ Performance in Teaching and Learning Physics: Are There Any Gender and Area Gaps?. Educ. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Droui, M., & El Hajjami, A. (2014). Simulations informatiques en enseignement des sciences: apports et limites. EpiNet: revue électronique de l’EPI, 164.

- Nafidi, Y., Alami, A., Moncef, Z. A. K. I., El Batri, B., & Afkar, H. (2018). Impacts of the use of a digital simulation in learning earth sciences (the case of relative dating in high school). Journal of turkish science education, 15(1), 89-108.

- Tuyizere, G.; Yadav, L.L. Effect of interactive computer simulations on academic performance and learning motivation of Rwandan students in Atomic Physics. Int. J. Evaluation Res. Educ. (IJERE) 2023, 12, 252–259. [CrossRef]

- Babateen, H. M. (2011). The role of virtual laboratories in science education. Singapore: IACSIT press.

- Keller, H., & Keller, E. (2005). Making real virtual labs. The Science Education Review, 4(1), 2-11. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1049733.pdf.

- Almasri, F. (2022). Simulations to teach science subjects: Connections among students’ engagement, self-confidence, satisfaction, and learning styles. Education and Information Technologies, 27(5), 7161-7181.

- Ben Ouahi, M.; Lamri, D.; Hassouni, T.; Al Ibrahmi, E.M. Science Teachers' Views on the Use and Effectiveness of Interactive Simulations in Science Teaching and Learning. Int. J. Instr. 2022, 15, 277–292. [CrossRef]

- Bo, W.V.; Fulmer, G.W.; Lee, C.K.-E.; Chen, V.D.-T. How Do Secondary Science Teachers Perceive the Use of Interactive Simulations? The Affordance in Singapore Context. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2018, 27, 550–565. [CrossRef]

- Gaba, D.M. The future vision of simulation in health care. Qual. Saf. Heal. Care 2004, 13, i2–i10. [CrossRef]

- Wieman, C.E.; Perkins, K.K. A powerful tool for teaching science. Nat. Phys. 2006, 2, 290–292. [CrossRef]

- Wieman, C.E.; Adams, W.K.; Loeblein, P.; Perkins, K.K. Teaching Physics Using PhET Simulations. Phys. Teach. 2010, 48, 225–227. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, A.M.; Brill, J.M. Investigating Practices in Teacher Education that Promote and Inhibit Technology Integration Transfer in Early Career Teachers. TechTrends 2016, 60, 136–144. [CrossRef]

- Kopcha, T.J. Teachers' perceptions of the barriers to technology integration and practices with technology under situated professional development. 2012, 59, 1109–1121. [CrossRef]

- Errington, E. (2011). The edge of reality: Challenges facing educators using simulation to supplement students' lived experience. Surrey Centre for Excellence in Professional Training and Education.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a mixed methods design. Designing and conducting mixed methods research, 53-106.

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage publications.

- Herga, N. R., Čagran, B., & Dinevski, D. (2016). Virtual laboratory in the role of dynamic visualization for better understanding of chemistry in primary school. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 12(3), 593-608.

- Hartley, J.R. Learning from Computer Based Learning in Science. Stud. Sci. Educ. 1988, 15, 55–76. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J. J. (1986). A Summary of Research in Science Education--1985.

- Lowe, D.; Newcombe, P.; Stumpers, B. Evaluation of the Use of Remote Laboratories for Secondary School Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2012, 43, 1197–1219. [CrossRef]

- Ben Ouahi, M.; Lamri, D.; Hassouni, T.; Al Ibrahmi, E.M. Science Teachers' Views on the Use and Effectiveness of Interactive Simulations in Science Teaching and Learning. Int. J. Instr. 2022, 15, 277–292. [CrossRef]

- McGarr, O. The use of virtual simulations in teacher education to develop pre-service teachers’ behaviour and classroom management skills: implications for reflective practice. J. Educ. Teach. 2020, 47, 274–286. [CrossRef]

- McGarr, O. The use of virtual simulations in teacher education to develop pre-service teachers’ behaviour and classroom management skills: implications for reflective practice. J. Educ. Teach. 2020, 47, 274–286. [CrossRef]

- Addis, D.R. Mental Time Travel? A Neurocognitive Model of Event Simulation. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 2020, 11, 233–259. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Sung, H.-Y.; Guo, J.-L.; Chang, B.-Y.; Kuo, F.-R. Effects of spherical video-based virtual reality on nursing students’ learning performance in childbirth education training. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 30, 400–416. [CrossRef]

- Sweeder, R.D.; Herrington, D.G.; VandenPlas, J.R. Supporting students’ conceptual understanding of kinetics using screencasts and simulations outside of the classroom. Chem. Educ. Res. Pr. 2019, 20, 685–698. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, E., Montoya, A., & Ágreda, J. (2020). CHEMical KINetics SimuLATOR (Chemkinlator): A friendly user interface for chemical kinetics simulations. Revista Colombiana de Química, 49(1), 40-47.

- Chairam, S.; Somsook, E.; Coll, R.K. Enhancing Thai students’ learning of chemical kinetics. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2009, 27, 95–115. [CrossRef]

- Chairam, S.; Klahan, N.; Coll, R. Exploring Secondary Students' Understanding of Chemical Kinetics through Inquiry-Based Learning Activities. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2015, 11. [CrossRef]

- Almasri, F. (2022). Simulations to teach science subjects: Connections among students’ engagement, self-confidence, satisfaction, and learning styles. Education and Information Technologies, 27(5), 7161-7181.

- Xie, Q.; Tinker, R. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Chemical Reactions for Use in Education. J. Chem. Educ. 2006, 83. [CrossRef]

- Zewail-Foote, M.; Venters, J.R.; Johnson, K.A. Teaching Chemical Kinetics with Dynamic Simulations. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 278–281. [CrossRef]

- Suits, J. P., & Sanger, M. J. (2013). Dynamic visualizations in chemistry courses. In Pedagogic roles of animations and simulations in chemistry courses (pp. 1-13). American Chemical Society.

- Plass, J.L.; Milne, C.; Homer, B.D.; Schwartz, R.N.; Hayward, E.O.; Jordan, T.; Verkuilen, J.; Ng, F.; Wang, Y.; Barrientos, J. Investigating the effectiveness of computer simulations for chemistry learning. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2012, 49, 394–419. [CrossRef]

- Penn, M.; Ramnarain, U. South African university students’ attitudes towards chemistry learning in a virtually simulated learning environment. Chem. Educ. Res. Pr. 2019, 20, 699–709. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Different benefits and values of using DS in schools.

Table 1.

Different benefits and values of using DS in schools.

| Benefits |

Value |

Percentage (%) |

| Enhances student engagement |

14 |

77.8 |

| Provides visual representation of abstract concepts |

13 |

72.2 |

| Help students grasp the concept faster |

9 |

50 |

| Allows for experimentation without lab equipment |

12 |

66.7 |

| Facilitates data analysis and interpretation |

8 |

44.4 |

| Allows to perform many experiments at the time |

12 |

66.7 |

| Encourage in-depth thinking or learners |

1 |

5.6 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).