1. Introduction

Recent advancements in Lab-on-a-Chip (LoC), micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS), and micromixer systems highlight the growing interest in engineering, biotechnology, and medicine due to their cost-effectiveness, ease of production, and repeatability [

1,

2,

3]. Microfluidic devices condense traditional laboratory functions into compact chips, enabling detection, mixing, synthesis, and separation at micro- and nano-scales. These systems offer significant advantages in chemical and biomedical analysis, including speed, precision, and minimal reagent use [

4,

5,

6]. Within microfluidics, micromixers are fundamental for achieving efficient fluid mixing and are broadly classified into passive and active types, depending on whether external energy sources are required.

Passive mixers operate without external energy and can be manufactured cost-effectively through methods like lithography [

7]. The mixing process in these devices often involves structural modifications within the microchannel to alter fluid flow velocities, such as introducing obstacles [

8], implementing sudden constrictions and expansions [

9], curving channels [

10], or using lamination techniques [

11] to promote turbulence. These modifications enable efficient blending by creating secondary flows and elongating the fluid interface. Optimized split-and-recombine techniques, for example, achieve high mixing efficiencies by leveraging these structural characteristics [

12,

13]. Channel geometry thus plays essential role in passive micromixer performance, where a series of repetitive mixing units can amplify efficiency by stretching the fluid interface through fluid-geometry interactions. Effective designs often feature serpentine channels, which induce secondary flows to further enhance mixing [

14,

15,

16].

However, the low Reynolds number typical in microfluidic devices limits the feasibility of turbulent mixing, making these systems heavily reliant on slower, diffusion-driven processes to achieve adequate mixing, often necessitating longer channels [

17,

18]. To address this limitation, researchers have introduced obstacles within the channel, which extends the fluid–fluid interface, enhancing mixing efficiency even in short channel lengths, despite the associated increase in pressure drop [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Additionally, combining serpentine channels with embedded obstacles has proven to be a powerful approach, effectively merging the benefits of both strategies to achieve even higher efficiencies [

23].

Active mixers, on the other hand, require various energy sources, leading to different production techniques such as pressure [

24], acoustics [

25,

26,

27,

28], magnetic fields [

29,

30], and electric fields [

31,

32,

33]. These mixers provide precise control over mixing rates and ratios at the channel exit, making them ideal for applications that demand rapid response or high-volume mixing, such as drug delivery, diagnostics, and biochemical assays [

34]. A key benefit of active mixers is their capability to adjust mixing efficiency (MI) in real time, which can significantly enhance process control. For instance, magnetic actuation is used in microsystems with micro-stirrers that generate circulation loops, effectively reducing mixing time and achieving higher MI at rotor speeds between 100 and 600 rpm [

35]. This real-time capability can incorporate permanent magnets [

36] or electromagnets [

37] to mix ferrofluids or even manipulate magnetic particles for specific biomedical applications [

38]. Innovative methods, like creating thermal bubbles or freezing microbeads within the flow, further expand the strategies available for efficient fluid mixing, adding versatility in design for application-specific needs [

39].

In both active and passive mixer systems, mixing calculations are typically performed under room conditions using the finite element method (FEM) for steady-state scenarios. These simulations often assume non-Newtonian and incompressible fluid properties [

40,

41,

42], which can lead to overestimations in simulated efficiency compared to experimental results. Optimizing channel size, geometry, and flow rate improves MI, often using two-dimensional (2D) FEM for reduced computation time [

43]. However, 2D and 2D axisymmetric models cannot capture flow variations across channel heights, leading to potential inaccuracies in performance predictions. Three-dimensional (3D) analyses address these issues, accounting for fluid velocity variations and local Re values to provide a more accurate representation of mixing dynamics [

44].

A 3D analysis of a microrobot-based active micromixer introduced a system with a rotor embedded in a microfluidic chip, enabling mixing at various rotor heights but excluding magnetic field influence, which complicates modeling due to nonlinear interactions [

13]. Practical application requires leak-proof chip designs, and our work proposes a simpler microrobotic configuration that eliminates leak-proofing and integrates seamlessly into microfluidic chips. Another study demonstrated a mobile microrobot system driven by a Helmholtz coil for mixing, though it faced scalability and control complexity issues [

32]. Our configuration, featuring two microrobots with one as a motor-driven actuator, allows adjustable levitation and orientation, representing a significant advance in microfluidic mixing technology.

In this study, we introduce a novel untethered microfluidic mixer system utilizing two identical microrobots that interact magnetically, with one acting as a propeller robot whose height is precisely adjusted through magnetic levitation. This levitation mechanism significantly reduces surface friction, enabling higher operational speeds and improved control over fluid dynamics, which are challenging in conventional tethered or fixed-position mixers. By simulating various roll and pitch orientations, we replicated the movement of a curved propeller blade without requiring complex 3D production techniques, streamlining fabrication and enhancing scalability. Critical parameters such as maximum drag force, torque, and rotational speeds were calculated across different configurations to determine their effects on mixing efficiency (MI). Performance testing at three distinct sections of the channel outlet, using data from 13,556 points over a 3-second interval, showed exceptional mixing efficiency, achieving up to 99.16% MI at 2000 µm from the chamber. These results highlight our microrobot levitation system’s capability for efficient mixing in compact, short-channel designs suitable for diverse applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microchannel Design

The active mixing system was designed around a Y-shaped microfluidic channel with a 0.5 mm x 0.5 mm square cross-section, featuring two fluid inlets and one outlet (

Figure 1). Fluid was introduced through the inlets, with concentrations set at 0 mol/m

3 and 1 mol/m

3 to create a gradient aimed at achieving a uniform 0.5 mol/m

3 concentration at the outlet, indicative of 100% mixing index (MI). A central mixing area, enclosed by an Infinite Element (IE) boundary to simulate an unbounded domain, provides a spherical air environment where two identical microrobots are positioned (

Figure 1-a). These microrobots contain N52-grade permanent magnets that generate a magnetic field, enabling levitation and rotation within the channel. The magnetic forces between the microrobots control their orientation and allow the propeller robot to rotate, inducing mixing as it interacts with incoming fluids from the inlets.

The microchannel includes a primary Mixing Chamber (3.0 mm in diameter) and an Effective Rotating Domain (2.8 mm in diameter), where the microrobots are actively engaged in fluid agitation (

Figure 1-b). To monitor mixing performance, three sections (labeled I, II, and III) were defined along the outlet channel, each spaced 1 mm apart, to evaluate the mixing at specific points immediately after the mixing area, at the midpoint, and at the outlet end, assessing the effect of diffusion on MI.

To achieve an accurate representation of flow dynamics, the channel geometry was discretized using a fine mesh, with a total of 13,556 sample points in the COMSOL simulation (

Figure 1-c). Mesh density was higher in critical regions, including near the center and corners, to capture detailed fluid flow and concentration gradients, especially close to channel walls where velocity gradients are most significant. Sample points were distributed within 20 µm x 20 µm regions, represented by blue and red-marked rectangles in

Figure 1-c, to ensure high-resolution mixing calculations. The boundary element mesh along the channel walls factored in gravity and surface tension effects.

To evaluate the efficiency of mixing, the microrobot system was analyzed in subsystems, including magnetic field, fluid flow, and transport of diluted species. Each subsystem was modeled and simulated in 3D using COMSOL Multiphysics software v6.0 [

45]. The Magnetic Fields No Currents (MFNC) module was used for magnetic torque analysis, while the Moving Mesh (Rotating Domain) and Laminar Flow (SPF) modules handled drag force calculations and fluid dynamics. Angular displacement and torque relationships were examined through Moving Mesh (Rotating Domain), Laminar Flow, and Global Equations (GE) modules. Post-processing yielded maximum torque and rotational speeds at various levitation heights.

Table 1 lists the boundary conditions used in COMSOL for solving fluid flow problems.

2.2. Magnetic Field

Magnetic field analyses calculated the attractive force among three permanent magnets within the microrobots. The magnetic field was modeled using Maxwell’s equations as:

where

represents the magnetic field distribution (A/m). The relationship between the magnetic flux density

(W/m

2) and

is given by:

where

is the vacuum permeability and

the magnetization (A/m). The magnetic scalar potential

(A) was determined using the Magnetic Fields, No Currents interface, leading to:

This equation assumes a constant magnetic scalar potential. The attractive magnetic force

exerted by the actuator robot on the propeller robot is then expressed as [

46]:

where

is the relative permeability. The torque produced by the magnet in an external field is determined by:

where

,

ℓ, and

r represent the anisotropy, the depth of the domain (in the z-direction), and the position vector linking the rotation axis to the element

, respectively. Here,

is the elemental force calculated over

N, the number of elements with surface

.

and

are the elemental forces acting along the y and x directions, respectively;

and

are the components of the position vector defined by the rotation axis and the midpoint of

.

2.3. Fluid Flow

The steady-state incompressible Navier-Stokes equations were used, with simulations solved alongside the continuity equation [

47]. The Partial Differential Equation (PDE) model was used to employ the stationary incompressible Navier-Stokes equations as follows:

Here,

represents the density of the fluid (

),

the velocity field vector (m/s),

the dynamic viscosity (Pa.s),

p the pressure (Pa), and

the external body forces (

). Mass conservation for fluid flow is based on the continuity equation:

The modeling of mixing processes for both Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids is governed by the continuity, momentum, and energy equations. The energy equation, which represents the conservation of energy, is presented as follows:

Here,

e denotes the energy per unit mass,

the stress tensor, and

the heat flux vector. The Reynolds number,

, which characterizes the flow regime (laminar or turbulent), is defined as:

Where is the average velocity (m/s), the hydraulic diameter (m), and the dynamic viscosity (Pa.s).

2.4. Transport of Diluted Species

The Laminar Flow (SPF) and Transport of Diluted Species (TDS) physics interfaces were utilized. The TDS interface handled the mixing of two dilute species, A and B, within the main circular area of the channel. These species entered the device through separate inlet ports at equal concentrations, diffusivities, and flow rates. The transient behavior of the mixing system was observed through time-dependent studies over 3 seconds at room conditions. The fluid was incompressible and Newtonian, with a density (

) of 1000

and a dynamic viscosity (

) of 0.001

. The concentration distribution of the species is determined by the convection-diffusion transport equation:

Here,

represents the molar fluxes,

the characteristic flow speed,

the rate of moles of species

i produced per unit volume per unit time,

the species concentration, and

the diffusion coefficient. The MI of the micromixers was evaluated using the Mixing Index (MI) [

48], calculated as follows:

where

is the mean concentration at each sampling node

i, and

is the reference concentration when the fluids are completely mixed, assumed to be 0.5. An MI of 1 corresponds to perfect homogeneity in this system. The standard deviation (SD) as a percentage by referencing the target mixing value:

The homogeneity of the mixing was evaluated using the Homogeneity Index (HI), calculated as follows:

where

is the mean concentration of the mixed species at each sampling node

i, and

is the standard deviation of the concentration at the same nodes. The HI ranges from 0% to 100%, where 100% indicates perfect homogeneity (complete mixing) and values closer to 0% indicate less homogeneity.

3. Numerical Analysis

Boundary conditions and key parameter settings were selected in COMSOL to reflect realistic microfluidic conditions and assess mixing efficiency (MI) accurately (

Table 1). The inlet concentrations, set at

and

mol/m

3, provided a high gradient to challenge the system’s mixing capability. A no-slip boundary (

mm/s) was applied along channel walls to simulate realistic frictional effects, critical in microfluidic flows. Outlet pressure was maintained at zero to ensure consistent flow without added pressure gradients. We used a species flow rate ratio of

for symmetrical fluid entry, allowing internal dynamics to drive MI. Remanent flux density (

T) ensured stable magnetic control of the microrobot while preventing excess force that could disrupt its orientation. To cover both laminar and transitional regimes typical in microfluidics, Reynolds numbers ranged from 0.01 to 1000, while propeller speeds from 0 to 6000 rpm enabled assessment of rotational effects on MI. Robot lengths from 0.75 to 2.5 mm were tested to evaluate size-dependent drag impacts on mixing efficiency, essential for optimizing microrobot dimensions within microfluidic channels.

3.1. Magnetic Field and Propeller Velocity

The levitation height of the propeller robot is adjustable based on the vertical distance between the robots. Different drag forces and magnetic forces exerted on the propeller robot affect the maximum achievable rotational speeds. To compare the effect of different levitation heights on mixing rates under consistent conditions, it is necessary to keep the robots’ speeds identical. Drag force and maximum torque values were calculated for each levitation height to determine the maximum rotational speed of the propeller robot. The analysis was performed in two stages using different setups for magnetic analyses (

Figure 2-a) and for examining the drag force and MI within a Y-shaped microfluidic channel (

Figure 2-b), where a microrobot centrally located mixes fluids from two inlets. The model in

Figure 2-a, featuring two identical microrobots placed at the center of an air domain with a specific levitation height

, was used to calculate the magnetic torque produced in the propeller robot. The surrounding Infinite Element (IE) domain enhanced the precision of these calculations. The next phase involved examining the drag force on the microrobot surface. The perpendicular placement of robots optimizes lateral force benefits, contrasting with parallel arrangements (

Figure 2-b).

As the propeller robot rotates in the fluidic chamber, it experiences significantly more drag force compared to the actuator robot, which is driven by a motorized system in the air, an angular offset (

) was expected between these robots [

3,

46]. Generated torque on the propeller robot was calculated using rotating robots to each other (

Figure 2-c), with results shown in

Figure 2-d. The torque values are inversely proportional to the levitation height

, influenced by lateral forces on the propeller’s magnets. The relationship between maximum torque values and

shows a more linear trend for

and higher, as depicted in section

Figure 2-e. The maximum speed values show characteristics similar to those of torque values, as shown in

Figure 2-f. Maximum speed calculations, which employed a stop condition in the global equation (GE) physics to balance magnetic torque (

) against drag torque (

), determine the propeller’s maximum rotational speed at the given levitation height. To maintain equal conditions for MI across different levitation heights, subsequent analyses were conducted at a constant propeller speed of 1500 rpm.

Additionally, the fluid flow and pressure distribution in the mixing chamber were analyzed to observe the dynamic impact of the propeller’s rotation on mixing. The initial state (t = 0 s) is shown in

Figure 3-a, where velocity magnitude and pressure distribution indicate symmetrical patterns as fluids enter through Inlet-1 and Inlet-2. After 1 second (t = 1 s), flow velocity and pressure distribution reflect the development of rotational flow within the chamber, driven by the propeller robot (

Figure 3-b). Velocity gradients in the mixing area suggest effective fluid mixing, while pressure differentials illustrate the influence of the rotating propeller on the overall flow dynamics.

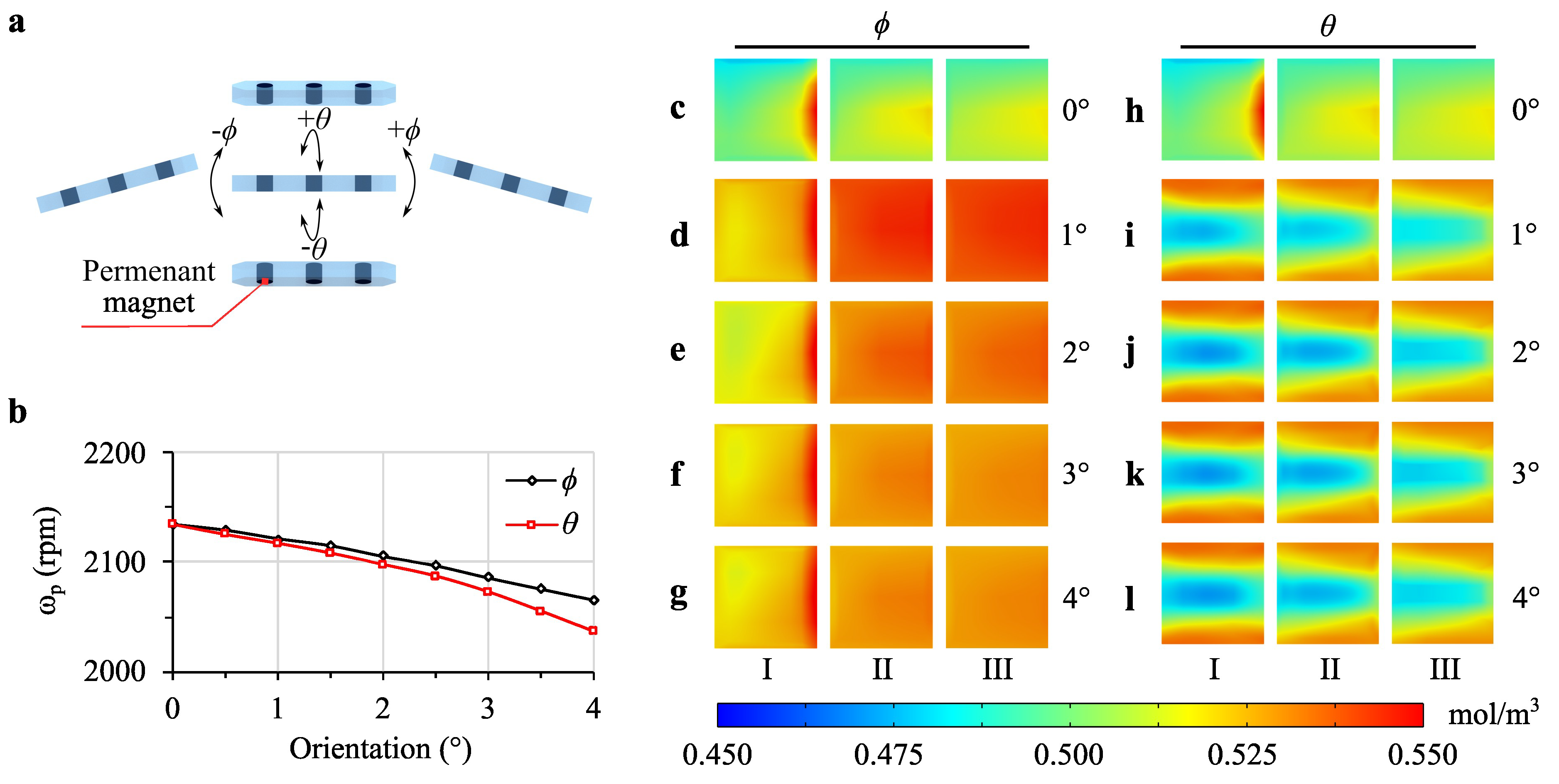

3.2. Levitation Height and Propeller Orientation

Figure 4 illustrates how levitation height affects the Mixing Index (MI) across sections I, II, and III. At lower levitation heights (e.g., 25 µm and 50 µm), the concentration profiles show a sharper gradient across the sections, indicating effective mixing due to the propeller robot’s proximity to the fluid. This close positioning increases fluid turbulence and interfacial area, thereby enhancing mixing efficiency. As the levitation height increases (e.g., 150 µm to 250 µm), the concentration gradients become more uniform, with MI values decreasing across the sections. This reduction in mixing efficiency at higher levitation heights suggests that the propeller’s influence on the fluid diminishes as it moves further from the mixing area, leading to lower turbulence and weaker fluid interactions.

Building on the observed effects of levitation height on MI, we next examined the impact of angled orientations of the propeller robot. To assess the effects of roll and pitch (phi) orientation on MI, the actuator robot was rotated around the yaw axis and tilted along the roll axis at an optimal levitation height of 150

m, chosen to minimize the risk of the robot contacting the channel surfaces. Simulations were conducted in

increments from

to

, totaling nine simulations over a 3-second duration. Initial conditions were calculated as in

Section 3.1 using a Frozen Rotor study. The same simulations for the roll axis orientation were replicated for the pitch axis to fully explore the effects of both orientations.

Figure 5 shows a propeller robot parallel to the surface at its center, with three permanent magnets inside depicted in a semi-transparent robot body. The robot’s orientation changes along its short edge (longitudinal) and its long edge (lateral) were represented by the roll angle (

) and the pitch angle (

), respectively. The speed changes as shown in

Figure 5-b were calculated in the propeller robot resulting from these orientations, with black and diamond markers for

and red square markers for

. Additional pitch movement alters the surface area actively interacting with the fluid, resulting in a greater reduction in speed. Visual representations of concentrations at the 3. second for orientations

(

Figure 5-(c-g)) and

(

Figure 5-(h-l)) are shown for angles

-

, using a common color bar range of 0.450-0.550

.

4. Results and Discussion

The propeller robot was levitated and rotated through interactions between its permanent magnets and those in the actuator robot. The maximum torque exerted on the propeller robot increases as levitation height decreases at the same angle difference (

Figure 2-d). Beyond 250 µm, no significant torque was generated and the highest torque value was observed at a

12.7°, with a value of 0.09 mNmm at 100 µm. We observed a linear relationship between levitation height and both maximum torque and rotational speed up to 150 µm (

Figure 2-(e, f)). Beyond 150 µm, significant torque and rotational speeds were not observed. The highest torque and rotational speed values were obtained at a levitation height of 25 µm, with values of 0.1 mNmm and 8602.4 rpm, respectively. The maximum rotational speed was achieved as 7500 rpm at 100 µm, and the maximum torque was 0.09 mNmm.

4.1. MI and HI Importance

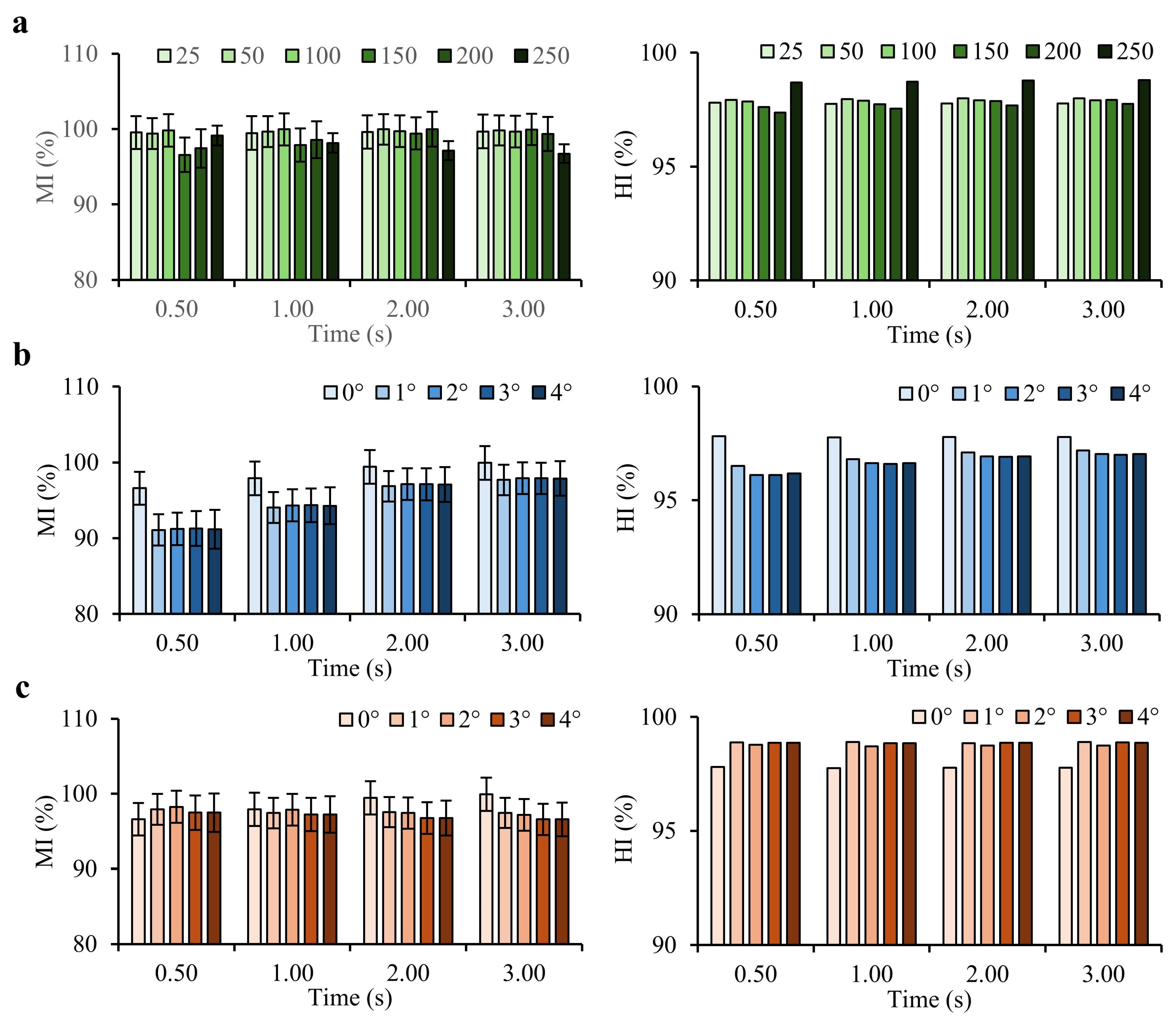

The Mixing Index (MI) and Homogeneity Index (HI) are key metrics for evaluating mixing performance in microfluidic systems. High MI indicates effective overall mixing, while high HI reflects uniformity in the distribution of mixed components. For example, a high Reynolds number (Re) can result in a high MI but a low HI because rapid flows might not provide sufficient time for uniform mixing, leading to uneven distribution. Conversely, specific orientation angles might yield a high HI but lower MI, showing uniform yet incomplete mixing. Achieving the best mixing performance requires both MI and HI indices to be high, ensuring thorough and uniform mixing throughout the system. To facilitate comparison of performance, we introduced a new parameter: the quality index, which is a composite measure of MI and HI (i.e., the mean of the sum of the mixing and homogeneity indexes). The quality index further supports these findings, achieving an overall quality index of 97.11% within 500 ms and 98.94% within 3 seconds at a rotational speed of 1500 rpm. At the outlet of the mixing chamber, the quality index reached 99.11% at 1 cm away and 99.16% at 2 cm away from the chamber after 3 seconds.

4.2. Levitation Height Effect

Figure 6-a illustrates the relationship between levitation height and both Mixing Index (MI) and Homogeneity Index (HI) over time (Supplementary Table 1). A levitation height of 100 µm achieves the highest average MI, indicating an optimal balance between torque generation and mixing efficiency. At lower heights (25 and 50 µm), higher initial mixing efficiencies are observed, likely due to the closer proximity of the propeller robot to the chamber floor, which enhances turbulence and fluid interaction. However, these lower heights may risk increased physical interaction with the chamber floor, potentially impacting the long-term stability of the mixing process.

As levitation height increases beyond 100 µm (up to 250 µm), MI and HI values decline. This reduction can be attributed to the increased distance between the propeller robot and the lower fluid layers, reducing the robot’s influence on fluid motion and shear force generation. The diminished fluid interaction at these greater heights results in decreased mixing efficiency, as indicated by the lower MI and HI values. This shows the important role of levitation height optimization in achieving effective mixing while maintaining operational stability. These results identify 100 µm as an optimal levitation height, where the propeller is positioned close enough to induce sufficient turbulence and fluid movement without risking collision or excessive drag forces.

4.3. Theta () and Phi () Effect

Figure 6-b shows the effect of propeller orientations with pitch angle (

) from 0° to 4° at 1° intervals (Supplementary Table 2). The 0° orientation shows the best results for

. Rotational speed decreases with increasing pitch angle, with the most significant speed reduction observed for larger angles. This reduction in speed impacts MI negatively, as shown by the lower MI and HI values for higher

angles. These results suggest that minimizing the pitch angle is beneficial to achieve a higher MI. The larger pitch angles cause greater drag forces, reducing the rotational speed and consequently the MI.

Figure 6-c illustrates the effect of propeller orientations with roll angle (

) from 0° to 4° with 1° intervals (Supplementary Table 3). Similar to the pitch angle, the 0° orientation provides the best MI. However, the impact of increasing the roll angle is less pronounced than that of the pitch angle. This suggests that while both angles affect MI, adjustments in pitch angle have a more significant impact than roll angle changes.

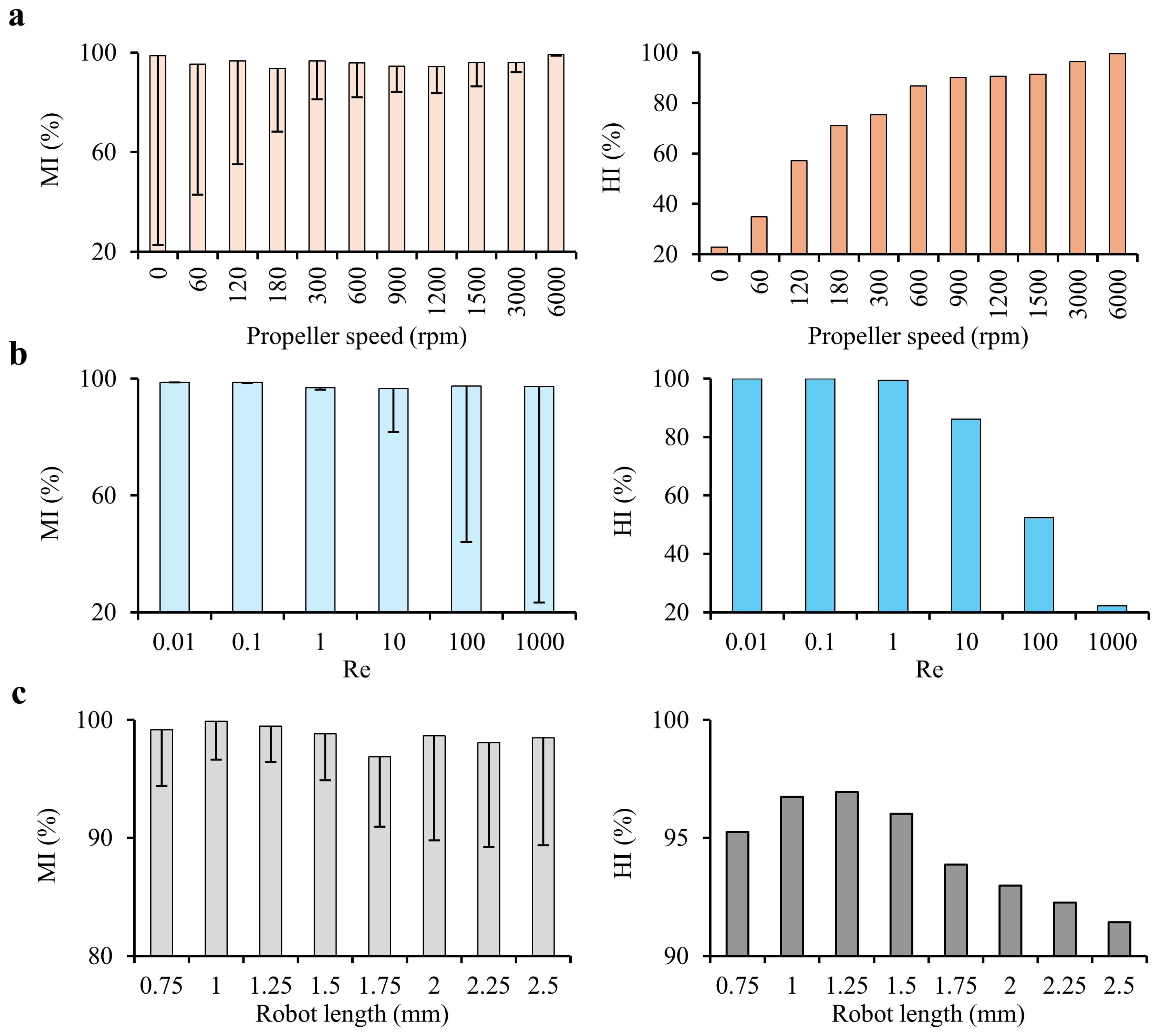

4.4. Propeller Speed and Inlet Flow Rate

As shown in

Figure 7-a, increasing the propeller speed from 0 to 6000 rpm enhances MI and HI while simultaneously reducing the standard deviation in MI, indicating more consistent and efficient mixing. At the maximum tested speed of 6000 rpm, the highest MI and HI values were achieved, reaching 99.219% and 99.509%, respectively. This trend underscores the direct correlation between rotational speed and mixing efficiency. Higher speeds improve fluid turbulence and interfacial area interactions, which facilitate better homogenization. In contrast, lower speeds are less effective in maintaining consistent mixing across the chamber, as indicated by the higher standard deviation. This analysis highlights the importance of optimizing rotational speed to maximize MI and HI, as faster rpm promotes more uniform concentration distribution throughout the system.

Figure 7-b explores the impact of Re, ranging from 0.01 to 1000, on MI and HI. At lower Re values, such as 0.01, the system achieves an MI of 98.767% and an HI of 100%, reflecting nearly ideal mixing conditions. This high efficiency at low Re is likely due to the slower fluid velocity, which allows for sufficient residence time within the mixing chamber for diffusion and advection processes to thoroughly mix the fluids. However, as Re increases, there is a marked decline in both MI and HI. For instance, at Re = 1000, MI falls to 97.264% and HI drastically decreases to 22.276%, indicating incomplete mixing. This decline at higher Re can be attributed to the rapid flow rate, which reduces the time available for fluids to interact and homogenize, causing them to pass through the chamber with insufficient mixing. Consequently, balancing the flow rate (and hence the Re) is essential in achieving effective mixing, especially in applications where precise control over concentration gradients is critical.

Together, the results indicate that both high rotational speed and controlled Re are essential for maximizing mixing efficiency in microfluidic systems. While increasing propeller speed enhances MI and HI by promoting turbulence and consistent fluid interaction, keeping Re at lower levels (e.g., Re = 0.01) ensures that fluids remain within the chamber long enough for complete mixing. The optimal configuration, therefore, involves a high propeller speed (close to 6000 rpm) combined with a low Re, which leverages both enhanced turbulence and adequate residence time. Deviations from this balance, such as excessively high Re, result in a trade-off where rapid fluid motion outpaces the mixer’s ability to homogenize the contents, as reflected in the drop in MI and HI at higher flow rates.

4.5. Robot Length Effect

Figure 7-c shows the Mixing Index (MI) and Homogeneity Index (HI) as functions of robot length, tested from 0.75 mm to 2.5 mm in a mixing chamber with a fixed diameter of 3 mm. The distance between the robot and the chamber wall is an essential factor affecting fluid dynamics and mixing performance, with corresponding robot-to-chamber ratios highlighting the relative size of the robot within the chamber.

At the smallest robot length of 0.75 mm, the wall clearance is 1.125 mm on each side, yielding a robot-to-chamber ratio of 0.25. This substantial clearance allows for ample fluid flow around the robot, but the smaller surface area limits the generation of effective mixing forces. In contrast, the maximum robot length of 2.5 mm leaves only 0.25 mm of clearance on each side, with a robot-to-chamber ratio of 0.83. This minimal clearance restricts fluid flow and limits mixing efficiency, even though the larger robot surface could theoretically enhance mixing through increased interaction area. An intermediate length of 1.25 mm, which provides a 0.875 mm clearance on each side and a robot-to-chamber ratio of 0.42, demonstrates the highest mixing performance, achieving MI and HI values of 99.486% and 96.943%, respectively. This balance in robot size and clearance optimizes fluid flow around the robot while maintaining adequate surface area to enhance mixing forces.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of magnetically levitated, untethered propeller robots in enhancing fluid mixing within microfluidic systems. By achieving rotational speeds up to 8602.4 rpm, the proposed system allows for rapid and efficient mixing over short distances, presenting a significant advantage over traditional microfluidic mixers. This enhanced control over mixing dynamics is made possible by independently adjusting the propeller’s orientation and velocity through magnetic interactions, making the approach particularly advantageous for lab-on-a-chip applications. Such systems often require precise and efficient mixing for applications like biological sample analysis, where the ability to achieve homogeneity quickly is crucial for reliable results.

A key strength of this system lies in its ability to introduce strong longitudinal forces and torques on the propeller robot, facilitated by its orientation capabilities. These forces enable rapid sample homogenization at the nano-level, addressing a common limitation in passive micromixing strategies. The optimal orientation of the propeller in the roll direction has been shown to increase mixing performance, reaching up to 98.94% efficiency (and up to 99.36% at 6000 rpm) with a low diffusion coefficient and a relatively small output port, demonstrating the method’s potential effectiveness in practical applications.

However, there are limitations to this study that future work should address. Firstly, the model operates under isothermal conditions, excluding potential temperature effects. In microfluidic systems, temperature gradients can significantly affect fluid properties such as viscosity and diffusivity, which, in turn, influence mixing efficiency. Future studies should consider incorporating temperature as a variable to simulate conditions more realistically aligned with experimental setups. Secondly, the assumption of Newtonian fluid behavior, while convenient, may limit the applicability of the model to non-Newtonian fluids, such as many biological samples, which exhibit complex flow characteristics that can alter mixing dynamics. Expanding the model to account for non-Newtonian properties would make it more versatile for applications involving a wider variety of fluids.

Furthermore, while this study models magnetic field effects as uniform and idealized, real-world magnetic fields are often non-uniform, especially when interacting with other magnetic materials. This non-uniformity can impact the stability and control of the microrobots’ motion. Future research could improve the model by including more realistic magnetic field distributions and considering potential distortions, thereby increasing the robustness and reliability of the system in experimental environments. Additionally, while we explored a range of Reynolds numbers, propeller speeds, and levitation heights, the study’s conditions were limited to a specific microchannel geometry and fluid flow configuration. Investigating different channel geometries, propeller shapes, and multiple interacting robots would provide further insights into scalability and adaptability in complex microfluidic networks.

As a result of this work, magnetically levitated microrobots can be used as efficient mixers in microfluidic systems, achieving high efficiencies with rapid mixing rates. Future research should focus on refining the operational dynamics through variations in influential parameters, such as channel size, propeller geometry, and a wider range of Reynolds numbers, to enable simulations across different flow regimes, including creeping, laminar, transition, and turbulent flows. Such advancements would broaden the applicability of this micromixing approach, potentially transforming the design and functionality of microfluidic mixers for diverse lab-on-a-chip and biomedical applications. Furthermore, integrating adaptive sensing mechanisms to dynamically control microrobot movement could enhance the system’s real-time adaptability and mixing efficiency in a wide array of microfluidic scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.D.; methodology, A.A.D.; software, A.A.D.; validation, A.A.D., A.Y., and H.U.; formal analysis, A.A.D.; investigation, A.A.D.; resources, A.Y. and H.U.; data curation, A.A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.D., and A.Y.; writing—review and editing, A.Y. and H.U.; visualization, A.A.D.; supervision, H.U.; project administration, H.U.; funding acquisition, A.Y. and H.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Council of Higher Education (YOK) of Turkey under project code FBA-2022-5328, titled "Imaging and Laser-Guided Energy Harvesting for In-Body Microrobot Manipulation".

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Supporting information is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

Abdurrahim Yilmaz has been funded by the President’s PhD Scholarships of Imperial College London. The Imperial College London Open Access Fund paid the open access fee.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Whitesides, G.M. The origins and the future of microfluidics. nature 2006, 442, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, G.S.; Chung, S.; Kim, C.B.; Lee, S.H. Applications of micromixing technology. Analyst 2010, 135, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demircali, A.A.; Uvet, H. Stabilization of microrobot motion characteristics in liquid media. Micromachines 2018, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tang, H.; Zong, N.; Jiang, X. Microfluidics for biomedical analysis. Small methods 2020, 4, 1900451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nette, J.; Howes, P.D.; deMello, A.J. Microfluidic synthesis of luminescent and plasmonic nanoparticles: fast, efficient, and data-rich. Advanced Materials Technologies 2020, 5, 2000060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, K.; Boyle, N.; Flaman, G.; Ramaswami, B.; van den Berg, A.; van der Stam, W.; Burgess, I.; Odijk, M. In situ spatiotemporal characterization and analysis of chemical reactions using an ATR-integrated microfluidic reactor. Lab on a Chip 2023, 23, 4690–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, M.; Jalali, N. Design and fabrication of an effective micromixer through passive method. Journal of Computational & Applied Research in Mechanical Engineering (JCARME) 2020, 9, 371–383. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, Y. Numerical study on stagger Koch fractal baffles micromixer. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2019, 133, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, B.; Mehta, S.K.; Patowari, P.K.; Pati, S. Numerical study of mixing in wavy micromixers: comparison between raccoon and serpentine mixer. Chemical Engineering and Processing-Process Intensification 2019, 136, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.; Kaufman, M.; Fodor, P.S. Mixing enhancement in serpentine micromixers with a non-rectangular cross-section. Micromachines 2018, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, T. A novel passive micromixer designed by applying an optimization algorithm to the zigzag microchannel. Chemical Engineering Journal 2017, 313, 1406–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, R.A.; Goodarzi, V.; Allahverdi, A. Mixing performance of a cost-effective split-and-recombine 3D micromixer fabricated by xurographic method. Micromachines 2019, 10, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Huang, X. Mixing in microchannels based on hydrodynamic focusing and time-interleaved segmentation: modelling and experiment. Lab on a Chip 2005, 5, 1320–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arockiam, S.; Cheng, Y.H.; Armenante, P.M.; Basuray, S. Experimental determination and computational prediction of the mixing efficiency of a simple, continuous, serpentine-channel microdevice. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2021, 167, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokas, S.; Zunaid, M.; Ansari, M.A. Non-Newtonian fluid mixing in a Three-Dimensional spiral passive micromixer. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 47, 3947–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampalli, S.; Dundi, T.M.; Chandrasekhar, S.; Raju, V.; Chandramohan, V. Numerical evaluation of liquid mixing in a serpentine square convergent-divergent passive micromixer. Chemical Product and Process Modeling 2020, 15, 20190071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubin, J.; Ferrando, M.; Jiricny, V. Current methods for characterising mixing and flow in microchannels. Chemical Engineering Science 2010, 65, 2065–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, V.; Löwe, H.; Schönfeld, F. Micromixers—a review on passive and active mixing principles. Chemical engineering science 2005, 60, 2479–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antognoli, M.; Stoecklein, D.; Galletti, C.; Brunazzi, E.; Di Carlo, D. Optimized design of obstacle sequences for microfluidic mixing in an inertial regime. Lab on a Chip 2021, 21, 3910–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunegatto, E.H.T.; Zinani, F.S.F.; Biserni, C.; Rocha, L.A.O. Constructal design of passive micromixers with multiple obstacles via computational fluid dynamics. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2023, 215, 124519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, G.; Lim, C.; Seong, G.H.; Choo, J.; Lee, E.K.; Kang, S.H.; Song, J.M. Evaluation of passive mixing behaviors in a pillar obstruction poly (dimethylsiloxane) microfluidic mixer using fluorescence microscopy. Microfluidics and nanofluidics 2009, 7, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, L.; Li, F. Numerical analysis of passive micromixer with novel obstacle design. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 2021, 42, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, B.; Mehta, S.K.; Pati, S.; Patowari, P.K. Numerical analysis of electroosmotic mixing in a heterogeneous charged micromixer with obstacles. Chemical Engineering and Processing-Process Intensification 2021, 168, 108585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.; Al-Rawahi, N.; Al-Azri, N.; Zunaid, M.; Ansari, M.Z. Mixing performance enhancement and parametric investigation of swirl-inlets split-and-recombine micromixer with pulsatile flow. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.; Mao, X.; Shi, J.; Juluri, B.K.; Huang, T.J. A millisecond micromixer via single-bubble-based acoustic streaming. Lab on a Chip 2009, 9, 2738–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.H.; Yang, J.; Pindera, M.Z.; Athavale, M.; Grodzinski, P. Bubble-induced acoustic micromixing. Lab on a Chip 2002, 2, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhao, X.; Ma, X.; Huang, L.; Qiu, Y.; Wei, J.; Hao, N. Acoustofluidic bubble-driven micromixers for the rational engineering of multifunctional ZnO nanoarray. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 450, 138273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, M.; Green, R.; Ohlin, M. Acoustofluidics 14: Applications of acoustic streaming in microfluidic devices. Lab on a Chip 2012, 12, 2438–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, A.; Karavelioglu, Z.; Aydemir, G.; Demircali, A.A.; Varol, R.; Kosar, A.; Uvet, H. Microfluidic wound scratching platform based on an untethered microrobot with magnetic actuation. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 373, 132643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayareh, M.; Usefian, A.; Ahmadi Nadooshan, A. Rapid mixing of Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids in a three-dimensional micro-mixer using non-uniform magnetic field. Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer Research 2019, 6, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Usefian, A.; Bayareh, M.; Shateri, A.; Taheri, N. Numerical study of electro-osmotic micro-mixing of Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering 2019, 41, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaher, A.; Ali, K.K.; Mekheimer, K.S. Electroosmosis forces EOF driven boundary layer flow for a non-Newtonian fluid with planktonic microorganism: Darcy Forchheimer model. International Journal of Numerical Methods for Heat & Fluid Flow 2021, 31, 2534–2559. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Yu, L.; Li, D.; Jagdale, P.P.; Xuan, X. Elastic instabilities in the electroosmotic flow of non-Newtonian fluids through T-shaped microchannels. Electrophoresis 2020, 41, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usefian, A.; Bayareh, M. Numerical and experimental study on mixing performance of a novel electro-osmotic micro-mixer. Meccanica 2019, 54, 1149–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.H.; Ryu, K.S.; Liu, C. A magnetic microstirrer and array for microfluidic mixing. Journal of microelectromechanical systems 2002, 11, 462–469. [Google Scholar]

- Nouri, D.; Zabihi-Hesari, A.; Passandideh-Fard, M. Rapid mixing in micromixers using magnetic field. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2017, 255, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Tsai, C.; Leong, K.; Wen, C. Rapid micromixer via ferrofluids. Physics Procedia 2010, 9, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.J.; Hou, H.H.; Wang, Y.N.; Fu, L.M. Micro-magnetofluidics in microfluidic systems: A review. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2016, 224, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.; Ballard, M.; Alexeev, A.; Hesketh, P.J. Rapid microfluidic mixing via rotating magnetic microbeads. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2016, 251, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircali, A.; Varol, R.; Aydemir, G.; Saruhan, E.N.; Erkan, K.; Uvet, H. Longitudinal Motion Modeling and Experimental Verification of a Microrobot Subject to Liquid Laminar Flow. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircali, A.A.; Varol, R.; Erkan, K.; Uvet, H. Untethered Microrobot Motion Mechanism With Increased Longitudinal Force. Journal of Mechanisms and Robotics 2021, 13, 061005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, B.; Mahajan, G.; Fodor, P.S.; Kaufman, M.; Kothapalli, C.R. Evolution of mixing in a microfluidic reverse-staggered herringbone micromixer. Microfluidics and Nanofluidics 2018, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, R.T.; Wu, C.Y. An efficient micromixer based on multidirectional vortices due to baffles and channel curvature. Biomicrofluidics 2011, 5, 014103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demircali, A.; Erkan, K.; Uvet, H. A study on finding optimum parameters of a diamagnetically driven untethered microrobot. Journal of Magnetics 2017, 22, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COMSOL Multiphysics® v. 6.0. www.comsol.com. COMSOL AB,: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020.

- Uvet, H.; Demircali, A.A.; Kahraman, Y.; Varol, R.; Kose, T.; Erkan, K. Micro-UFO (untethered floating object): A highly accurate microrobot manipulation technique. Micromachines 2018, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, R.W.; McDonald, A.T.; Mitchell, J.W. Fox and McDonald’s introduction to fluid mechanics; John Wiley & Sons, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Gao, Y.; Ghaznavi, A.; Zhao, W.; Xu, J. AC electroosmosis micromixing on a lab-on-a-foil electric microfluidic device. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 359, 131611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic of the active mixing system with design parameters. (a) Overview of the system setup, where two identical microrobots are positioned within a spherical air domain enclosed by an Infinite Element (IE) boundary. The Y-shaped channel has a square cross-section, featuring two inlets and one outlet, and a single propeller robot at the center that rotates to mix incoming fluids. (b) Top view of the Y-shaped channel, highlighting the mixing chamber (3.0 mm diameter), rotating domain (2.8 mm diameter), and outlet sections I, II, and III, each spaced 1 mm apart. (c) Mesh node distribution in a 0.5 mm × 0.5 mm cross-section of the channel, with detailed views of center (red) and corner (blue) nodes in 20 µm × 20 µm regions.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the active mixing system with design parameters. (a) Overview of the system setup, where two identical microrobots are positioned within a spherical air domain enclosed by an Infinite Element (IE) boundary. The Y-shaped channel has a square cross-section, featuring two inlets and one outlet, and a single propeller robot at the center that rotates to mix incoming fluids. (b) Top view of the Y-shaped channel, highlighting the mixing chamber (3.0 mm diameter), rotating domain (2.8 mm diameter), and outlet sections I, II, and III, each spaced 1 mm apart. (c) Mesh node distribution in a 0.5 mm × 0.5 mm cross-section of the channel, with detailed views of center (red) and corner (blue) nodes in 20 µm × 20 µm regions.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the active mixing system with design parameters. (a) The magnetic field distribution generated around two identical microrobots within the mixing system. The inset shows a close-up view of the concentrated field lines between the actuator and propeller robots, illustrating the magnetic interactions that facilitate mixing. (b) Close frontal view of the robots with magnetic field force lines. (c) The angular difference, , between the actuator and propeller robots during rotation, varies with fluid and actuator speeds. (d) Torque, , on the propeller robot as a function of . (e) Relationship between maximum torque and levitation height, , showing an exponential decrease in torque with increasing . (f) Maximum propeller speeds, , indicating a range of 1501.4-8602.4 rpm.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the active mixing system with design parameters. (a) The magnetic field distribution generated around two identical microrobots within the mixing system. The inset shows a close-up view of the concentrated field lines between the actuator and propeller robots, illustrating the magnetic interactions that facilitate mixing. (b) Close frontal view of the robots with magnetic field force lines. (c) The angular difference, , between the actuator and propeller robots during rotation, varies with fluid and actuator speeds. (d) Torque, , on the propeller robot as a function of . (e) Relationship between maximum torque and levitation height, , showing an exponential decrease in torque with increasing . (f) Maximum propeller speeds, , indicating a range of 1501.4-8602.4 rpm.

Figure 3.

Flow velocity and pressure distribution in the mixing chamber at different times. (a) Initial state (t = 0 s) showing velocity magnitude and pressure distribution as fluid enters through Inlet-1 and Inlet-2. The velocity plot (left) indicates initial flow patterns with high speeds near the inlets, while the pressure plot (right) displays a symmetric pressure distribution. (b) After 1 second (t = 1 s), flow velocity (left) and pressure distribution (right) reflect the development of rotational flow within the chamber, driven by the propeller robot. Velocity gradients in the mixing area indicate effective fluid mixing, and pressure differentials illustrate the dynamic impact of rotation.

Figure 3.

Flow velocity and pressure distribution in the mixing chamber at different times. (a) Initial state (t = 0 s) showing velocity magnitude and pressure distribution as fluid enters through Inlet-1 and Inlet-2. The velocity plot (left) indicates initial flow patterns with high speeds near the inlets, while the pressure plot (right) displays a symmetric pressure distribution. (b) After 1 second (t = 1 s), flow velocity (left) and pressure distribution (right) reflect the development of rotational flow within the chamber, driven by the propeller robot. Velocity gradients in the mixing area indicate effective fluid mixing, and pressure differentials illustrate the dynamic impact of rotation.

Figure 4.

Mixing Index (MI) distributions at different levitation heights of the propeller robot, showing concentration profiles across three sections (I, II, III) at the outlet. Each row (a-f) corresponds to a specific levitation height (25, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 µm, respectively) and demonstrates the concentration distribution from the inlet toward the outlet. The color bar (0.45–0.55 mol/m3) represents concentration levels, where red indicates higher mixing efficiency and blue represents lower mixing efficiency. As levitation height increases, the mixing efficiency generally decreases, as indicated by lower concentration gradients across sections I, II, and III.

Figure 4.

Mixing Index (MI) distributions at different levitation heights of the propeller robot, showing concentration profiles across three sections (I, II, III) at the outlet. Each row (a-f) corresponds to a specific levitation height (25, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 µm, respectively) and demonstrates the concentration distribution from the inlet toward the outlet. The color bar (0.45–0.55 mol/m3) represents concentration levels, where red indicates higher mixing efficiency and blue represents lower mixing efficiency. As levitation height increases, the mixing efficiency generally decreases, as indicated by lower concentration gradients across sections I, II, and III.

Figure 5.

The effect of different orientation and angle values of the propeller robot at a levitation height of 150 on mixing is illustrated. (a) The orientation capabilities of a propeller robot positioned parallel to the surface, expressed as the roll angle, and pitch angle, , controlled by the actuator robot. (b) Speed values during the robot’s orientation at different angles, with the speed values corresponding to - for (in black) and (in red). Visuals of the concentrations at the 3. second for angle are shown from (c-g), and for angle from (h-l), respectively, for angles to with a interval. A common color bar with limits of 0.450-0.550 is used for both groups.

Figure 5.

The effect of different orientation and angle values of the propeller robot at a levitation height of 150 on mixing is illustrated. (a) The orientation capabilities of a propeller robot positioned parallel to the surface, expressed as the roll angle, and pitch angle, , controlled by the actuator robot. (b) Speed values during the robot’s orientation at different angles, with the speed values corresponding to - for (in black) and (in red). Visuals of the concentrations at the 3. second for angle are shown from (c-g), and for angle from (h-l), respectively, for angles to with a interval. A common color bar with limits of 0.450-0.550 is used for both groups.

Figure 6.

Mixing Index (MI) and Homogeneity Index (HI) as functions of time for different conditions. (a) Different levitation heights from 25 to 250 µm at time intervals of 0.5 s, 1 s, 2 s, and 3 s. Initial conditions (0 s) have non-uniform mixing, with data for finer intervals (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3 s) provided in the Supporting Information. (b) Propeller orientations with pitch angle () from to with intervals. (c) Propeller orientations with roll angle () from to with intervals. The orientation shows the best results for both and parameters.

Figure 6.

Mixing Index (MI) and Homogeneity Index (HI) as functions of time for different conditions. (a) Different levitation heights from 25 to 250 µm at time intervals of 0.5 s, 1 s, 2 s, and 3 s. Initial conditions (0 s) have non-uniform mixing, with data for finer intervals (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3 s) provided in the Supporting Information. (b) Propeller orientations with pitch angle () from to with intervals. (c) Propeller orientations with roll angle () from to with intervals. The orientation shows the best results for both and parameters.

Figure 7.

Mixing Index (MI) and Homogeneity Index (HI) for various conditions. (a) MI and HI as functions of propeller speed, ranging from 0 to 6000 rpm. Faster rpm reduces the standard deviation (SD%) in MI% and increases HI%, indicating improved MI with higher rotational speeds. (b) MI and HI as functions of Reynolds number (Re), ranging from 0.01 to 1000. Higher Re increases SD% as the liquids move too quickly through the channel length, not allowing enough time for effective mixing, resulting in reduced HI%. (c) MI and HI as functions of robot length, ranging from 0.75 mm to 2.5 mm. A length of 1.25 mm gives the best result, showing the highest MI, but has limited space for three magnets in the chamber with a diameter of 3 mm.

Figure 7.

Mixing Index (MI) and Homogeneity Index (HI) for various conditions. (a) MI and HI as functions of propeller speed, ranging from 0 to 6000 rpm. Faster rpm reduces the standard deviation (SD%) in MI% and increases HI%, indicating improved MI with higher rotational speeds. (b) MI and HI as functions of Reynolds number (Re), ranging from 0.01 to 1000. Higher Re increases SD% as the liquids move too quickly through the channel length, not allowing enough time for effective mixing, resulting in reduced HI%. (c) MI and HI as functions of robot length, ranging from 0.75 mm to 2.5 mm. A length of 1.25 mm gives the best result, showing the highest MI, but has limited space for three magnets in the chamber with a diameter of 3 mm.

Table 1.

Summary of Boundary Conditions and Key Parameter Settings Used in COMSOL Simulations

Table 1.

Summary of Boundary Conditions and Key Parameter Settings Used in COMSOL Simulations

| Parameter |

Value(s) |

Unit |

| Inlet concentration |

= 0, = 1 |

mol/m3

|

| Wall effects |

No slip; = 0 |

mm/s |

| Outlet pressure |

= 0 |

Pa |

| Species flow rate ratio |

= 1 |

- |

| Remanent flux density |

B = 1.4 |

T |

| Reynolds numbers (Re) |

0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 1000 |

- |

| Propeller speeds |

0, 60, 120, 180, 300, 600, 900, 1200, 1500, 3000, 6000 |

rpm |

| Robot lengths |

0.75, 1, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, 2, 2.25, 2.5 |

mm |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Short Biography of Authors

|

Ali Anil Demircali received the B.S., M.S., and Ph.D. degrees in Mechatronics Engineering from Yildiz Technical University, Turkey, in 2015, 2017, and 2021, respectively. He is currently employed as a KTP Associate in the Mechanical Engineering Department at the University of Bath. His primary research interests encompass Micro-Nano Robotics, Control System Design, Sensory Systems, and Fiber Robotics. |

|

Abdurrahim Yilmaz received the B.S., M.S. degrees in Mechatronics Engineering from Yildiz Technical University, Turkey, in 2020 and 2022, respectively. He is a PhD student at Imperial College London. His primary research interests encompass Artificial Intelligence and Robotic Systems. |

|

Huseyin Uvet received the B.S. degree in computer science from Istanbul Kultur University, Istanbul, Turkey, in 2004, and the M.S./Ph.D. degrees from Osaka University Systems Science and Applied Informatics, Osaka, Japan, in 2007 and 2010, respectively, with the focus on micro/nano-robotics and lab-on-a-chip systems. He is currently an Assistant Professor with Department of Mechatronics Engineer, Yildiz Technical University. His research interests include micro/nano-robotics, lab-on-a-chip devices, biomedical robotics, and micro-nano air vehicles. He is an Expert System Innovation Engineer with a diverse ability in mechatronics device engineering and assembly process automation. He received numerous prizes and awards from prestigious international and national competitions, conferences. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).