Introduction

The cosmetics industry is currently one of the most rapidly developing branches of industry in the world. The global cosmetics market value in 2021 amounted to 425.5 billion euros, and a 5% average annual growth is forecasted for the years 2023–2026 [

1]. In Poland, there are over 600 cosmetics manufacturers—large corporations with global brands as well as small producers—and the value of the Polish cosmetics market in 2023 amounted to 25.4 billion PLN, placing it fifth in Europe. In 2023, Poland was the ninth largest exporter of cosmetics in the world (3.8% share of exports) and fifth in the European Union (8%). Cosmetics from Poland are exported to over 160 countries, both within the European Union (including Germany, France, Spain, the United Kingdom) and to distant countries such as the United States, Canada, Mexico, Indonesia, and Australia [

2]. This development translates into an increasingly wide range of cosmetics and cosmetic products on the market. Manufacturers offer products with more or less complicated compositions, containing well-known or completely new active substances, of natural or synthetic origin, dedicated to specific consumer needs. It is estimated that the average woman uses 12 cosmetic products daily, containing a total of up to 168 ingredients, while the average man uses 6 cosmetic products containing a total of approximately 85 ingredients [

3].

The quality of a cosmetic product entering the market is a key factor determining the safety of its users; therefore, it must meet the requirements specified in relevant legal acts. In the European Union countries, the requirements for cosmetic products have been specified in Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009, with subsequent amendments. According to its content, “a ‘cosmetic product’ means any substance or mixture intended to be placed in contact with the external parts of the human body (...), with a view exclusively or mainly to cleaning them, perfuming them, changing their appearance, protecting them, keeping them in good condition or correcting body odours.” Moreover, this document standardized the regulations and guidelines regarding control, safety, liability, and documentation related to the production and distribution of cosmetics, detailing prohibited substances in cosmetics (Annex II covering 1,730 entries), substances that may be included in cosmetics in limited amounts (Annex III covering 378 entries), permitted colorants (Annex IV covering 153 entries), preservatives (Annex V covering 60 entries), and UV filters (Annex VI covering 34 entries). This regulation is also in force in Poland, and it is complemented by a number of national regulations concerning detailed guidelines for the trade of cosmetic products (Journal of Laws 2018 item 2227, Journal of Laws 2019 item 350, Journal of Laws 2019 item 417). The Regulation of the Minister of Health of March 19, 2020 (Journal of Laws 2020 item 931) presents detailed requirements for the analysis of selected cosmetic ingredients, taking into account the sample preparation stage, analytical techniques, and methods of analysis.

EU regulations impose on manufacturers and importers the obligation to conduct detailed testing of the raw materials used and the cosmetic products offered. While large corporations have their own analytical laboratories, small enterprises and individual consumers use external laboratory services. Year by year, the number of commercial research laboratories offering detailed quality assessments of cosmetic raw materials and cosmetics is increasing, based on determining their basic quality parameters, microbiological purity, or chemical composition. The tests performed in these laboratories are based on methodologies described in relevant standards indicated by the Polish Committee for Standardization, regulations, or their own methods—developed based on scientific research or application notes from equipment manufacturers, e.g., [

4].

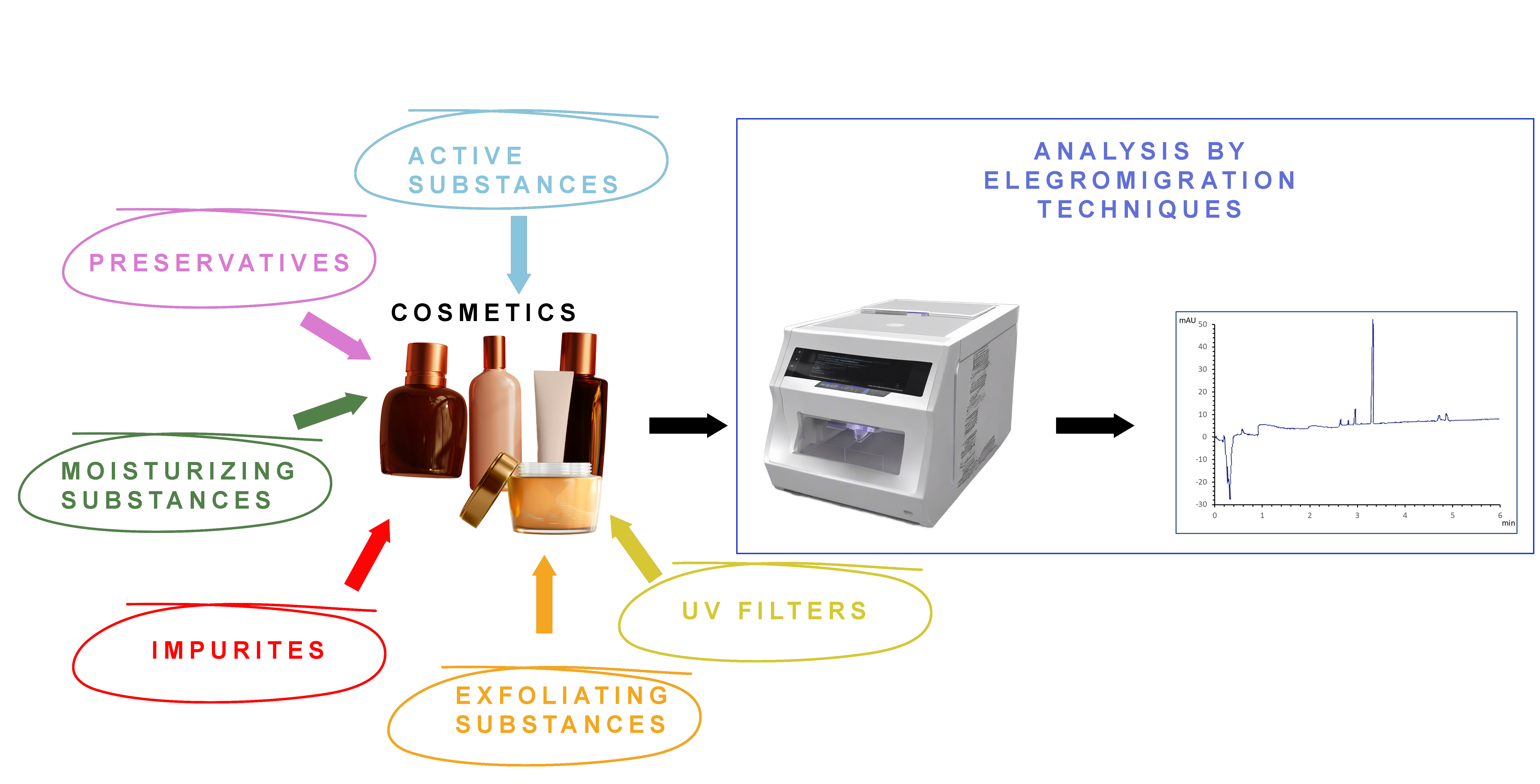

Cosmetic formulations are created to meet consumer expectations and a range of rigorous requirements regarding safety, application properties, and effectiveness. A cosmetic contains base substances (e.g., water, alcohols), form-stabilizing agents (e.g., preservatives, antioxidants), active ingredients (e.g., surfactants, UV filters), or auxiliary substances (e.g., coloring agents, fragrances). Many of them have limitations regarding their percentage content in the final product. An example is preservatives (e.g., sodium benzoate, phenoxyethanol, potassium sorbate, benzyl alcohol, esters of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid), whose presence is essential in cosmetics containing water. Preservatives provide protection of the cosmetic product against the development of bacteria and fungi, thereby ensuring the safety of the product throughout its shelf life [

5]. On the other hand, coloring substances are intended exclusively or mainly for coloring the cosmetic product (mainly for aesthetic purposes), the entire body (e.g., self-tanners), or certain parts of it (lipsticks, powders, pencils, mascaras). They are used in the form of dyes, which permanently bind to the colored surface, or coloring substances that are applied to the surface temporarily. On cosmetic product labels, in the list of ingredients, dyes and pigments, with the exception of hair dyes, are listed under the CI (Color Index) identification number of the given dye [

6]. Substances absorbing UV light serve as UVA and UVB filters. Among them are physical filters, known as mineral filters, such as zinc oxide (ZnO), titanium dioxide (TiO₂), and chemical filters, which include organic compounds: benzophenones, cinnamates, derivatives of p-aminobenzoic acid, and salicylates. The use of UV filters in cosmetic products is strictly regulated by law. Furthermore, all UV filters allowed for use in cosmetic products have been positively evaluated in terms of safety by the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [

7].

In order to confirm the presence of a given ingredient in a cosmetic product and its quantity, an appropriate method of analysis should be applied to ensure good quality control. Frequently, due to the high complexity of the matrix, it is required to properly prepare the tested cosmetic sample prior to the analysis. Many analytical techniques are used for the analysis of cosmetics, including chromatographic (high-performance liquid chromatography - HPLC [

8,

9], gas chromatography - GC [

9,

10], ion chromatography - IC [

11]), electromigration (capillary electrophoresis - CE [

12], micellar electrokinetic chromatography - MEKC [

13]), spectrometric (infrared spectrometry - IR [

14], atomic absorption spectrometry - AAS [

15], coupled with inductively coupled plasma: optical emission spectrometry - ICP-OES or mass spectrometry - ICP-MS [

16]), while the technique selection depends on the type and nature of the analyte [

17,

18].

The aim of this study was to review the literature on electromigration techniques and the possibility of their application for the qualitative and quantitative determination of cosmetic ingredients.

Electromigration Techniques

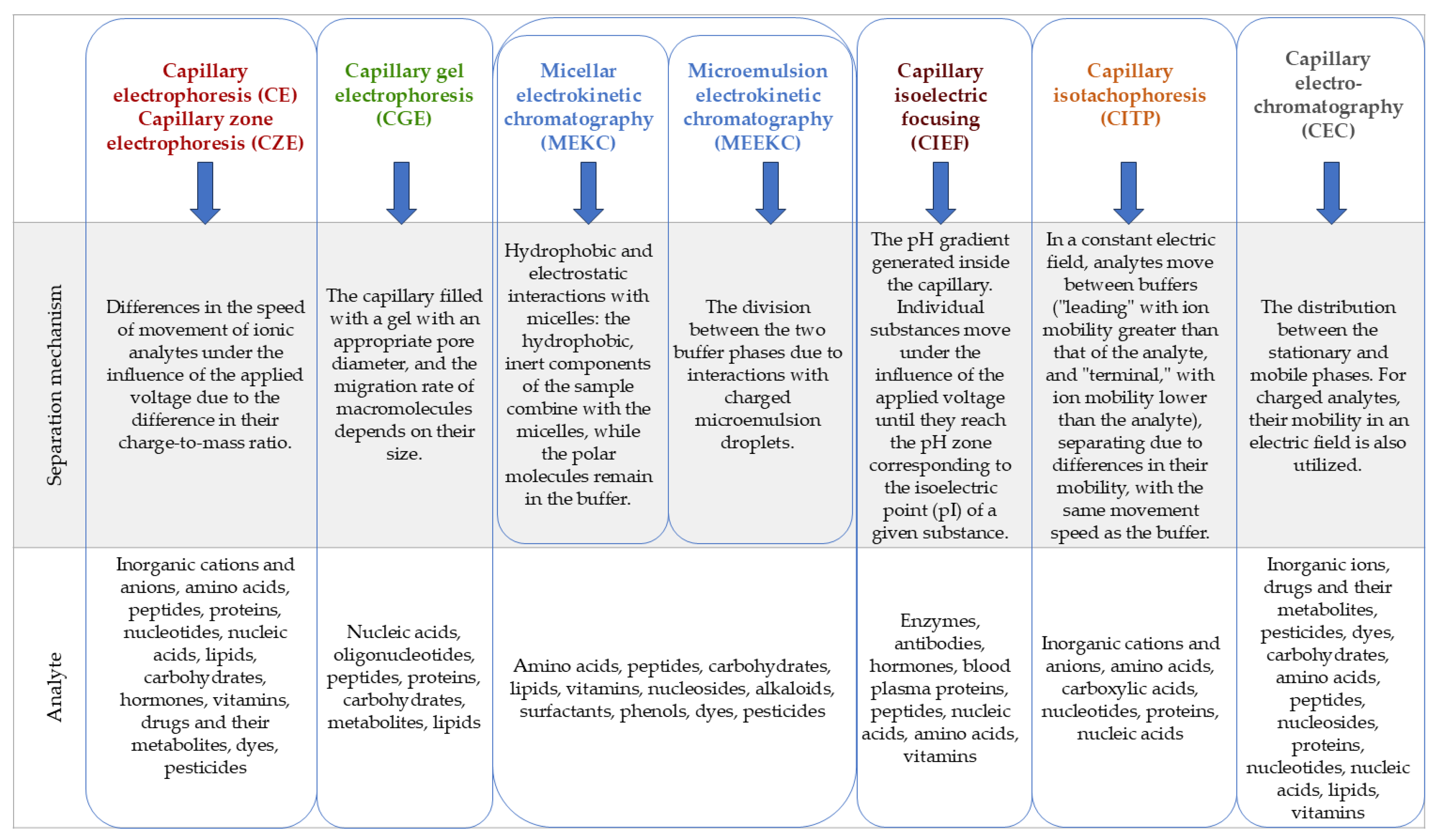

Separation Mechanism

Electromigration techniques are techniques for qualitative and quantitative analysis of multicomponent samples, based on the phenomenon of particle migration through a capillary filled with a conductive liquid medium called a buffer or electrolyte (often referred to as BGE -

Background Electrolyte), in an electric field [

19]. Due to the method of conducting the separation process, several types of electromigration techniques can be distinguished, according to the scheme presented in

Figure 1.

Since the introduction of modern capillary electrophoresis (called high-performance capillary electrophoresis) by Jorgernson and Lukacs in 1981 [

20], this technique has gradually evolved to eventually become a comprehensive analytical technique of interest to scientists, which is confirmed by numerous scientific works on both theoretical issues, new technical solutions, including miniaturization [

21,

22], and its applications in various areas of life, such as medicine, pharmacy, cosmetology, the food industry and environmental protection [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

The determination and separation of analytes in capillary electrophoresis is the result of two electrokinetic processes caused by the application of an electric field: 1) electrophoresis, i.e. the phenomenon occurring in the electrolyte volume, in which molecules with an unbalanced electric charge move under the influence of an applied electric field towards the oppositely charged electrode; and 2) electroosmosis, which causes a volumetric flow of liquid in the capillary tube. The basis for the separation of analytes in this technique are differences in electrophoretic mobility of marked particles that move at different speeds in an electric field with intensity which is the ratio of the applied voltage to the length of the applied capillary. The second phenomenon that occurs in the capillary during the analysis of electromigration techniques is electroosmotic flow (EOF), i.e. the movement of all the liquid filling the capillary caused by the potential difference. Obtaining the optimal EOF velocity ensures the best resolution and repeatability with the shortest possible analysis time. The EOF velocity of the buffer in the capillary is equal to the movement speed of the chemical compound soluble in the applied buffer, the molecules of which, under given process conditions, do not have an electric charge, do not interact with the inner surface of the capillary and are detectable by the used detector. These can be, for example, organic compounds such as acetone, benzene, phenol, pyridine or dimethylsulfoxide [

19,

22,

28].

Figure 1.

Division and characterization of electromigration techniques .

Figure 1.

Division and characterization of electromigration techniques .

Electromigration Techniques and Liquid Chromatography—A Comparison

Due to the complex chemical composition of cosmetics, which often complicates the correct identification and quantitative analysis of specific ingredients or potential contaminants, as well as legal requirements, it is important that the analytical method used meets certain criteria. In this context, it is essential to compare electromigration techniques with more commonly used chromatographic methods. Both types of methods have unique features and capabilities that determine their application in cosmetic analysis; however, they also have certain limitations that should be considered when choosing the appropriate method.

Capillary electrophoresis (CE) and ion chromatography (IC) are two powerful analytical techniques used for the separation and detection of ionic components. Due to their similar application areas, these methods were initially the subject of comparative studies in ion determination [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Currently, ion chromatography is recognized as a reference method for determining basic inorganic cations and anions in drinking water and wastewater [

33,

34]. This has led to its more frequent use in determining ionic components in other matrices, including studies on the quality of cosmetic raw materials and the ionic composition of cosmetics [

35,

36,

37]. Although CE and IC have some similarities, they differ significantly in terms of fundamental operating principles and performance characteristics (

Table 1), which makes the scope of their application possibilities different.

Both CE and IC aim to separate ions in a mixture, but this separation results from different mechanisms. CE separates ions based on their differential migration time in an electric field, while IC relies on differences in ion affinity to the stationary ion-exchange phase), leading to different profiles of analysis efficiency. CE is characterized by excellent separation efficiency of analytes and shorter analysis times, while consuming a small amount of sample and reagents, making it a more environmentally friendly technique and, in terms of laboratory and industrial research, more economical. On the other hand, IC, although slower and requiring larger sample volumes, exhibits higher sensitivity, especially for anion analysis, and can be easily used for analyzing high-conductivity samples. CE is more versatile and generally cheaper, but its sensitivity, especially for anions, is lower, and its application is limited to low-conductivity samples. Additionally, temperature fluctuations significantly affect CE, whereas IC remains relatively unaffected by these changes.

Similar to IC, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) also exhibits versatility and precision in analyzing components of varying polarity and molecular weight (

Table 2). The versatility of HPLC lies in its ability to identify and quantitatively analyze a wide range of compounds, from small organic molecules to large polymer compounds, making it invaluable in the analysis of cosmetics with complex matrices [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Although slower compared to CE, the HPLC technique is highly sensitive, and the use of various detectors enhances its analytical capabilities.

Electromigration techniques, inherently more environmentally friendly and economical due to low solvent and reagent consumption, are ideal for rapid separation analyses and preliminary sample cleaning. On the other hand, analyses requiring high precision and the ability to separate more complex mixtures and non-volatile components are better conducted using chromatographic techniques. Furthermore, chromatography is often more useful in routine analyses due to better-defined standards, protocols, and greater equipment availability in industrial laboratories. When comparing both groups of techniques, it should be emphasized that the choice between them should be closely related to the specific requirements of the analysis (type of analyte, type of matrix, required sensitivity, complexity of sample preparation, costs, analysis time, and result processing). Validation parameters obtained during HPLC and CE analyses of hexachlorophene content in cosmetics conducted by Li et al. [

38] indicate a slight advantage of the HPLC method over CE (quantification limits (LOQ) are 0.19 µg/mL and 0.15 µg/mL, average recoveries – 92.3% and 102.2%, and average relative standard deviations (RSD) – 1.7% and 0.32% respectively for CE and HPLC), and the nearly three times shorter analysis time of CE (5 and 14 minutes, respectively for CE and HPLC) suggests choosing this technique as more economically advantageous. Although the HPLC analysis of parabens in cosmetics [

39] required almost twice the analysis time, in this case, the chromatographic method was characterized by, depending on the analyte, a 4 to 8 times lower detection limit than CE. In turn, the advantage of ITP compared to HPLC is the lack of necessity for preliminary sample preparation and derivatization, which makes the analysis costs using this method lower. However, a disadvantage of ITP is the relatively high detection limit values [

43].

The limitations of electromigration techniques can be mitigated by using chromatographic techniques or vice versa. Such synergy used in complex analytical studies allows for obtaining the full chemical composition of the tested cosmetic, including information about its purity and safety, and indirectly also on the correctness of the technological process conducted.

Application of Electromigration Techniques in Cosmetic Analysis

Every year, new works on the analysis of the composition of cosmetics using electromigration techniques, mainly capillary zone electrophoresis (marked in the literature with the abbreviation CE or CZE) and micellar electrokinetic chromatography (MEKC) appear in the scientific literature databases (

Figure 1). Although it is not as impressive a figure as that of liquid chromatography (over 2,000 articles in the past 10 years), the existence of these works highlights the need to employ electrophoretic techniques in areas where HPLC chromatography encounters certain limitations.

Figure 1.

The number of publications from 2003, according to the Scopus database (keywords: for CE - cosmetics AND "capillary electrophoresis"; for MEKC - cosmetics AND "micellar electrokinetic chromatography").

Figure 1.

The number of publications from 2003, according to the Scopus database (keywords: for CE - cosmetics AND "capillary electrophoresis"; for MEKC - cosmetics AND "micellar electrokinetic chromatography").

Preservatives

The most commonly used preservatives in cosmetics are parabens, which are alkyl esters of 4-hydrocybenzoic acid, especially methylparaben (MP), ethylparaben (EP), propylparaben (PP), butylparaben (BP), isobutylparaben (iBP) or benzylparaben (BZP). These are substances with a broad antimicrobial effect, good stability over a wide pH range and low volatility. Due to synergistic effects, cosmetics often contain two or more parabens. Recent studies indicate the harmful effect of parabens on the human body (allergies, disorders of the endocrine system); therefore, the applicable law allows for the use of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, its salts and esters in limited amounts - not exceeding 0.4 wt% for a single paraben and 0.8 wt%. - for a mixture of parabens, expressed as acid concentration.

There is a lot of research in the literature on the possibility of using electromigration techniques for the identification and concentration analysis of parabens in cosmetic products [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. Some of them along with the used methodologies are listed in

Table 3.

The most common method for determining parabens was capillary electrophoresis with spectrophotometric detection in a variable wavelength detector (UV) [

44,

45,

46] or a diode array detector (DAD) [

47,

48] at wavelengths ranging from 200 to 298 nm, at a temperature of 20 or 25

0C, in quartz capillaries with an internal diameter of 50 µm. Optimization of the composition of buffers BGE used for the analyses allowed for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of both parabens and several other preservatives, such as: sorbic acid (SOA), benzoic acid (BA), salicylic acid (SA), p-hydroxybenzoic acid (HBZA) and dehydroacetic acid (DHOA). The micellar electrokinetic chromatography technique MEKC with borate buffer (BB) [

49,

50,

51] or phosphoric acid buffer [

13] modified with sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), and capillary electrochromatography (CEC/DAD), with a capillary filled with 5 µm Lichrospher 100 C18 phase [

52] was also successfully used for the analysis of parabens.

Cosmetics in the form of cream, toner, lotion, gel, shampoo, powder or paste are samples with complex matrices that require appropriate preparation for analysis. Cabaleiro et al. in their work [

53] reviewed the methods of preparing samples containing parabens for their analysis using various techniques, including electromigration. In turn, Maijo et al. [

54] determined the effect of the type of analyte concentration technique used on the values of the validation parameters of the method used (CE or MEKC), using the following strategies: large volume sample stacking (LVSS), field amplified stacking injection (FASI), sweeping and in-line solid-phase extraction–capillary electrophoresis (in-line SPE-CE). In the case of electrophoretic concentration, the obtained limit of detection (LOD) values ranged from 18 to 27; from 3 to 4 and were equal to 2 ng/mL, respectively for sweeping, LVSS and FASI, while for the in-line SPE-CE method, these limits were significantly lower (from 0.01 to 0.02 ng/mL). Classic ultrasonic extraction of parabens from shampoo foam using an ether-acetic acid mixture [

39] allowed for a quantitative, quick (10 minutes) and accurate analysis of MP, EP and PP parabens; however, under the applied analysis conditions, it was impossible to separate the isomeric forms of butyl-paraben (BP and IBP). The analysis of the same samples by means of HPLC allowed for the separation of these isomers, and the analysis time was 2 times longer. The obtained LOD values for the HPLC technique were significantly lower (from 20 to 50 ng/mL) than those obtained for the CE (160 - 210 ng/mL), but nevertheless higher than those obtained with the FASI-CE technique [

54]. Ye et al. [

44] proposed the sorption of parabens using graphene as a SPE sorbent, and then their desorption from the sorbent with methanol. This method of sample preparation allowed to obtain LOD values in the range from 100 to 150 ng/mL, slightly lower compared to the ultrasonic extraction proposed by Labat et al. [

39]. The CE technique with simultaneous stacking with a large sample zone and sweeping made it possible to determine the parabens extracted from the cream with methanol [

46]. Using BGE buffer containing 50 mM phosphate buffer (PB) with pH 3.0; 80 mM SDS and 30% methanol it was also possible to separate butylparaben from isobutylparaben.

The method used by Xue et al. [

45] based on dispersive liquid-liquid micro extraction coupled with capillary electrophoresis (DLLME-CE) turned out to be a fast, cheap and effective method of analysing both hydrophobic preservatives, such as parabens: MP, EP, BP and PP, and hydrophilic preservatives such as acids: sorbic (SOA), benzoic (BA) and salicylic (SA) in creams and lotions. Compared to high-performance liquid chromatography combined with microwave assisted extraction (MAE-HPLC), DLLME-CE allowed for obtaining 10 times lower LOD values (0.2 mg/kg for EP and BA and 0.375 mg/kg for other analytes, with two times shorter extraction time (18 minutes).

The use of the LVSS technique in MEKC made it possible to achieve a much higher sensitivity and resolution of paraben analysis compared to the classic MEKC analysis [

13]. On the other hand, MEKC combined with the sweeping technique, under optimal analysis conditions, turned out to be useful for determining the concentration of parabens next to the whitening ingredients of cosmetics (hydroquinone, arbutin, kojic acid, resorcinol and salicylic acid), with detection limits lower than the maximum concentration level for the tested compounds determined by applicable legal acts [

50]. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of parabens in cosmetics is also possible using microemulsion electrokinetic chromatography [

51] and capillary electrochromatography [

52]. Nevertheless, to achieve high sensitivity, repeatability and resolution of the analysis, the conditions for its conduct should be carefully selected.

Exfoliating and Moisturizing Substances

One of the groups of chemical compounds appearing in a cosmetic as an exfoliating agent is α-hydroxy acids, called fruit acids (AHA), i.e. organic acids with hydroxyl groups attached to the carbon atom adjacent to the carboxyl group, found naturally in most fruits, milk, sugar cane juice, wine or beer. For the production of cosmetics, lactic, malic, glycolic, citric, almond or tartaric acids are most frequently used [

55,

56]. In cosmetic products, these acids are usually present in concentrations from 4 to 10%, with the exception of chemical peeling, in which they are present in concentrations even above 20%. The recommended daily AHA use limit that does not threaten the consumer is 10%; therefore, it is required to control the content of these compounds in cosmetic products.

Among electromigration techniques, capillary electrophoresis with UV [

12,

57] or DAD detection was most frequently used for qualitative and quantitative confirmation of the presence of these compounds in cosmetic products (

Table 4).

In order to achieve a better separation of AHA acids, Liu et al. [

58] and Chen et al. [

59] applied an additive to the buffer in the form of γ-cyclodextrin (γ-CD), which changes the mobility of the analytes due to the formation of AHA-CD complexes.

Among the numerous ingredients of moisturizing cosmetics, two groups can be distinguished: 1) hydrophilic compounds, e.g. collagen, hyaluronic acid, sorbitol, urea, and 2) hydrophobic compounds, which include, among others, fatty acids and ceramides. Literature reports indicate the possibility of using electromigration techniques to analyze the content of selected compounds from both groups. Selected examples of such analyses are presented in

Table 4.

Hyaluronic acid, which is a linear polysaccharide composed of alternately repeating units of D-glucuronic acid and

N-acetyl-D-glucosamine linked by β-1,4 and β-1,3-glycosidic bonds, respectively, was the subject of research by Lin et al. [

60] on the selection of MEKC analysis conditions, enabling the simultaneous analysis of low-molecular and high-molecular hyaluronic acid in a cosmetic matrix using Olivem 1000. Under the optimal analysis conditions presented in

Table 4, it was possible to separate the peaks of the tested analytes within 10 minutes, with 98.2% and 95.3% analyte recovery, and detection limits of 2 and 10 µg/mL, for low and high molecular acid, respectively. In turn, Chindaphan et al. [

61] proposed CE with a large volume sample stacking using the electro-osmotic flow pump (LVSEP), with a detection limit of 3 µg/mL to determine the content of this acid in cosmetics.

Examples of the use of electromigration techniques for the determination of moisturizing substances of a hydrophobic nature are the tests described in the works [

62,

63] presenting the possibilities of capillary electrophoresis for the analysis of fatty acids: palmitic, stearic, oleic, linoleic. Considering the fact that the fatty acids used in cosmetics come mainly from vegetable oils, the analysis of their composition should be the first step in the preliminary assessment of the quality of such raw material and its suitability for the production of a cosmetic [

62]. The methodology for detecting and separating enantiomers of panthenol (L-panthenol and dexpanthenol) using cyclodextrin electrokinetic chromatography (CD-EKC) was developed by Jiménez et al. [

64]. Under optimal analytical conditions—25 mM (2-carboxyethyl)-β-CD (CE-β-CD) in 100 mM borate buffer (pH 9.0), a voltage of 30 kV, and a temperature of 30 °C—the analytes were separated within 4.2 minutes, achieving a resolution of 2.0, with LOQs of 1 mg/L and 4 mg/L for the L- and Dex-enantiomers, respectively. This demonstrates that the developed method meets the requirements of the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) for detecting contaminating L-panthenol (0.1% relative to the predominant enantiomer).

Substances Absorbing UV Light

Sunscreen cosmetics contain substances that act as filters of, harmful to the skin, ultraviolet radiation. Benzophenones, phenylbenzotriazoles, as well as p-aminobenzoic, p-methoxycinnamic, salicylic acids and their derivatives are used as chemical UV absorbents [

65]. Examples of the methodologies for analyzing this group of cosmetic ingredients are presented in

Table 5.

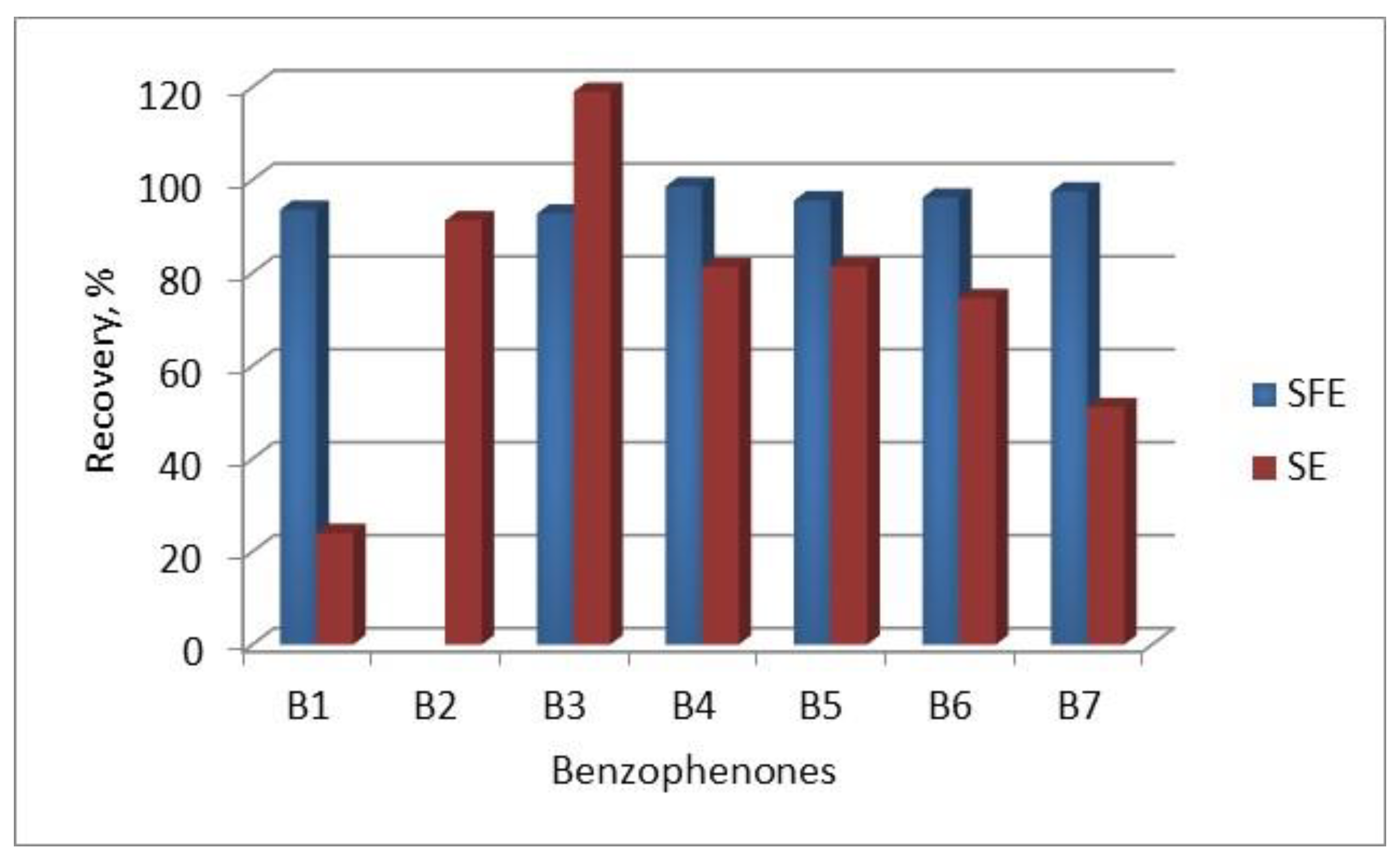

Electromigration techniques such as CE, MEKC and MEEKC have been successfully applied to the analysis of benzophenones [

40,

66,

67], p-aminobenzoic acid and 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenophenone-5-sulfonic acid [

40]. Wang et al. [

66] analyzed seven benzophenones in commercially available sunscreen cosmetics using CE with sample pretreatment by supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) using CO

2 with 2.5% modifier in the form of a mixture of 10% phosphoric acid and methanol (1 : 1). Although SFE failed to extract 2,2',4,4'-tetrahydroxybenzophenone (B2), this technique allowed for extracting larger amounts of the remaining six benzophenones from cosmetics compared to the classic SE solvent extraction (

Figure 2), and their CE analysis was possible in less time than HPLC analysis. It was also found that adding the non-ionic surfactant Tween 20 to the buffer increases the peak resolution of the analyzed benzophenones.

Three times shorter analysis time for CE compared to HPLC was achieved by Juang et al. [

40] for eight UV absorbers, with simultaneously good reproducibility of the proposed method, expressed through RSD in the range of 1.65–3.55%, and LODs of individual analytes from 0.23 to 1.86 µg/ml. Optimization of conditions for MEKC and MEEKC also allowed for the separation and detection of benzophenones in cosmetic samples [

67]. It was found that the concentration of SDS added to the buffer and the column temperature do not significantly affect the resolution of benzophenones separation in the case of MEEKC, but they are important in the case of MEKC. In addition, the buffer pH and the presence of ethanol as an organic modifier significantly affect the separation selectivity for both techniques, and increasing the applied electric voltage improves the separation efficiency, while reducing the separation resolution for MEKC, without a noticeable reduction in separation resolution for MEEKC.

The use in MEEKC of a buffer containing two surfactants: anionic SDS and neutral Brij 35 and an organic modifier in the form of 2-propanol, allowed for qualitative and quantitative analysis (with LOD ranging from 0.8 to 6.0 µg/ml) also of other cosmetic ingredients absorbing UV light, included in the group of absorbers under the trade name Eusolex: Eusolex 4360 (ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate), Eusolex 6300 (butyl methoxydibenzoylmethane, Eusolex OCR (octocrylene); Eusolex 2292 (ethylhexyl salicylate); Eusolex 6007 (diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate, Eusolex 9020 (ethylhexyl triazone), Eusolex HMS (bis-ethylhexyloxyphenol methoxyphenyl triazine), Eusolex OS: (ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate), Eusolex 232 (octyl salicylate) [

68].

Antioxidants

Antioxidants, often regarded as a "miracle" ingredient in cosmetics for their ability to rejuvenate cells and prevent skin cancer, can pose potential health risks when used in excess. For this reason, alongside the need for tests to exclude prohibited antioxidants, the quantity of permitted ones should also be monitored.

Table 6 presents selected examples of antioxidant analyses in cosmetics using electrophoretic techniques.

Many synthetic antioxidants such as propyl gallate (PG), tert-butyl hydroquinone (TBHQ), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) are used in the manufacture of skin care products. To determine PG and TBHQ in cosmetic samples, the CE technique with amperometric detection (CE-EC) was proposed, using a porous connection that eliminates the influence of high-voltage electrophoretic field on the EC detector with a three-electrode system (carbon fibre electrode/platinum electrode/silver chloride electrode) and the analysis conditions listed in

Table 6 [

69]. Electrochemical detector has also been successfully used for the simultaneous analysis of all four of the above-mentioned antioxidants, carried out using the MEKC technique [

70]. To achieve effective quantitative determination of carnosine and niacinamide in cosmetic formulations (whitening essence sample and an antiglycation pill), Chen et al. [

71] utilized CE with microchips made from cyclic olefin copolymer (COC) featuring dynamic and static coatings. The static coating was developed through the adsorption, immobilization, and closure of active sites of bovine serum albumin, which enhanced the hydrophilicity of the COC surface and minimized nonspecific peptide adsorption. Meanwhile, the dynamic coating was formed by adding a surfactant to the buffer, playing a key role in regulating flow rate and improving column efficiency in the separation channel. The analyses were performed using a 0.1 mM sodium tetraborate buffer with 0.03% SDS, achieving analyte separation within 30 minutes, with recoveries ranging from 80.9% to 112.6% and detection limits of 0.09 mg/kg for carnosine and 0.17 mg/kg for niacinamide. In turn, L-ascorbic acid and its derivatives, magnesium salt of ascorbic acid-2-phosphate and ascorbic acid-6 palmitate, were simultaneously determined using MEKC [

72]. Optimization of the analysis parameters and buffer composition allowed for the separation and quantitative analysis of these whitening agents in cosmetics in less than 15 minutes, achieving good precision and accuracy of the applied method (RSD < 3%).

Dyes

A large group of cosmetics available on the market are the so-called color cosmetics (nail polishes, powders, shadows, lipsticks, blushes, etc.) and cosmetics with coloring properties (hair dyes, mousses and gels for dyeing hair), whose color is due to the presence of numerous coloring substances in them in the amounts regulated by relevant legal acts. Details of exemplary analyses of this group of cosmetics ingredients are presented in

Table 6. The CE technique with a buffer with the optimized composition: 100 mM acetate buffer + 90% vol. methanol (pH = 6.6) was used to determine five basic dyes from the group of the so-called Arianols present in hair dyes, and the results of this method validation (%RSD: 3.7 - 5.9%; LOQ: 2.3 - 14.8 µg/mL; % recovery: 93.3 - 111.2%) indicate a sensitivity, precision and accuracy sufficient to be used to control the quality of hair care products [

73]. It was noted that washing the entrance end of the capillary with 90% (v/v) methanol immediately after injecting the sample prevented the peaks from tailing.

Gładysz et al. [

74] proposed the MEKC analysis methodology with DAD detection, sample preparation by ultrasound-assisted extraction and a repeatable procedure of taking small amounts of the sample using a specially designed and constructed device for the identification of 8 dyes present in red lipsticks from different manufacturers. In turn, Sun et al. [

75] proposed a novel approach to open-tubular capillary electrophoresis (OT-CEC) using the diblock copolymer poly(butyl methacrylate)

71-block-poly(glycidyl methacrylate)

9 (P(BMA)

71-b-P(GMA)

9 for separating aromatic amines in nail polishes. Compared to traditional capillaries, this innovative coating material significantly enhanced separation performance, with detection limits of 13.6 µM for aniline, 7.2 µM for p-nitrylaniline, and 9.9 µM for α-naphthylamine.

Other Cosmetics Ingredients and Contaminants

In addition to the applications of electromigration techniques for analyzing cosmetic compositions mentioned in the previous chapters, the literature also proposes the use of CE with different detectors, MEEKC, and CITP for analyzing specific cosmetic ingredients and impurities. The conditions for conducting such analyses are presented in

Table 7. CE systems with UV detection with borate buffer (BB) were successfully utilized for determination of hexachlorofene [

38], anionic, cationic, and amphoteric surfactants [

41] and chelating agents such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, ethylenediamine-disuccinic acid and iminodisuccinic acid [

42]in different cosmetics. In turn, CE-DAD technique with MES/MOPSO/TTAB buffer were most useful for silver nanoparticles analysis in face cream [

76].

In addition to the applications of electromigration techniques for analyzing cosmetic compositions mentioned in the previous chapters, the literature also suggests the use of CE with various detectors, MEEKC, and CITP for examining specific cosmetic ingredients and impurities. The conditions for performing such analyses are summarized in

Table 7. CE systems with UV detection using borate buffer (BB) have been successfully employed for the determination of hexachlorophene [

37], anionic, cationic, and amphoteric surfactants [

40], as well as chelating agents such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, ethylenediamine-disuccinic acid, and iminodisuccinic acid [

41] in different cosmetics. Meanwhile, the CE-DAD technique with MES/MOPSO/TTAB buffer proved most effective for analyzing silver nanoparticles in face cream [

75].

Martínez-Girón et al. [

77] analyzed perfumes for the presence of polycyclic musks: galaxolide, tonalide, traseolide, and phantolide, using a MEKC system with chiral cyclodextrin selectors (CD-MEKC) and a 2-[N-cyclohexylamino]ethane sulfonic acid (CHES) buffer supplemented with SDS. Through method optimization, separation of the analytes in under 10 minutes for tonalide, 13 minutes for traseolide and phantolide, and 17 minutes for galaxolide was achieved. Furthermore, a sweeping injection strategy was employed to enhance the method's sensitivity, enabling a concentration factor increase of up to 12 times compared to the conventional injection method.

Capillary electrophoresis coupled with tandem mass spectrometry with inductively coupled plasma (ICP-MS/MS) allowed Zajda et al. [

78] to investigate the encapsulation of a copper tripeptide complex (GHK–Cu) in liposomes. This analytical setup provided effective separation of all sample components, which were then detected using isotope-specific ICP-MS/MS, enabling simultaneous analysis of copper as a marker of the active cosmetic ingredient and phosphorus as a marker of the liposome. In addition to the intended ingredients of cosmetics, their composition may also include impurities, the source of which may be the cosmetic raw material with insufficient purity used in production, a production device from which they are released, or deliberately adding them to the cosmetic.

Ni et al. [

79] developed a quick and simple method for the analysis of MEEKC of seven structurally similar corticosteroids (prednisone, hydrocortisone, prednisolone, hydrocortisone acetate, cortisone acetate, prednisolone acetate, and triamcinolone acetonide) in samples of selected cosmetics, using the ionic liquid 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate (BmimBF

4). A synergistic effect was observed between the ionic liquid and the surfactant SDS, resulting in a reduction of the concentration of surfactants above which micelles are spontaneously formed. It was possible to separate the analyzed corticosteroids in approximately 28 minutes, with the following validation parameters: recoveries ranging from 86 to 114%, RSD below 4.8%, and LODs from 1.9 mg/L for prednisolone to 3.5 mg/L for hydrocortisone acetate.

The presence of such substances in the cosmetic as toxic heavy metals (e.g. Cd, Pb and Hg) or phenolic compounds (bisphenol A, α- and β-naphthol, 2,4-dichlorophenol), may have a very negative effect on the human body, therefore, the scope of cosmetic quality control should also include these substances. An example of the use of electromigration techniques for the analysis of heavy metals in cosmetics is the research of Chen et al. [

80]. They developed a technique of sample preconcentration by sweeping through dynamic chelation before the actual Pb, Hg and Cd analysis with CZE. The result of the application of such methodology was the quantitative analysis of lead, cadmium and mercury ions in cosmetics with the detection limits of 15, 50 and 100 ng/mL for Pb, Hg and Cd, respectively. In turn, Zhou et al. [

81] proposed CZE/UV with a two-stage sample preparation consisting of dispersive microextraction of analytes in a mixture of ionic liquid and acetone (IL-DLLME) and their re-extraction into sodium hydroxide solution for the determination of phenolic compounds in aqueous cosmetics. Under the optimal conditions of the experiment, the concentration coefficients and detection limits were respectively 60.1 and 5 ng/ml for bisphenol A, 52.7 and 5 ng/ml for β-naphthol, 49.2 and 8 ng/ml for α-naphthol, and 18.0 and 100 ng/ml for 2,4-dichlorophenol.

Summary

Although capillary electrophoresis is often considered inferior to other analytical techniques, particularly high-performance liquid chromatography, due to its lower sensitivity—primarily caused by the use of less sensitive detectors (typically UV-Vis)—reduced repeatability attributed to the small sample injection volume, and the "ageing" of the capillary's inner surface leading to variations in electroosmotic flow, studies in the literature demonstrate that these criticisms are not entirely justified and that the mentioned issues can be resolved. In recent years, the use of modern solutions in the construction of the CE apparatus and the replacement of spectrophotometric detection with more sensitive and/or selective detectors, e.g. electrochemical, conductometric, mass spectrometry, laser-induced fluorescence, or appropriate preparation of the sample before analysis, allow for obtaining a satisfactory sensitivity and reproducibility at the same level or sometimes better than the values obtained for the HPLC analysis.

Electromigration techniques are characterized by high efficiency and selectivity, short analysis times and low consumption of reagents. The advantage of CE is also the possibility of analyzing substances of both low and high molecular weights, charged and neutral, with the most often uncomplicated stage of sample preparation. Moreover, the used capillaries are more durable and less susceptible to damage compared to the columns used in HPLC (introducing a sample with a complex matrix into the HPLC column carries a high risk of damaging the column), which is important considering the costs of the analysis.

Based on the literature review, it can be concluded that, despite the fact that electromigration techniques are less popular and less frequently, compared to HPLC, used in routine laboratory analyses, they can be successfully applied to determine a wide range of substances, both ionic and neutral, included in cosmetics. The use of an appropriate technique and optimization of the process conditions allows for obtaining good sensitivity, repeatability and resolution of the analysis, with the limits of quantification of analytes at a level sufficient to achieve values below those indicated in the regulations in force.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K..; writing—review and editing, M.M.-N., R.M.; reference collection, J.K., R.M.; tables and figures J.K., M.M.-N., K.J.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of the Abbreviations Used

For methods: CGE – capillary gel electrophoresis; CIEF – capillary isoelectric focusing; CE – capillary electrophoresis; CEC – capillary electrochromatography; CGE – capillary gel electrophoresis; CITP – capillary isotachophoresis; CZE – capillary zone electrophoresis; DAD – diode array detector; FASI – field amplified stacking injection; HPLC – high performance liquid chromatography; IC – ion chromatography; LVSS – large volume sample stacking; DLLME – dispersive liquid-liquid micro extraction; MAE – microwave assisted extraction; LVSEP – large volume sample stacking using the electro-osmotic flow pump; IL-DLLME – dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction; MEKC - micellar electrokinetic chromatography; MEEKC – microemulsion electrokinetic chromatography; SFE – supercritical fluid extraction; SE – solvent extraction; UV – ultraviolet detector; Vis – visible detector

For chemicals: ACN – acetonitrile; AF – ammonium formate; BA – benzoic acid; BB – borate buffer; BGE – background electrolyte; BP – butylparaben; BZP – benzylparaben; CAPS - 3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid; ; CE- β-CD – (2-carboxyethyl)- β-cyclodextrin; CHES – 2-[N-cyclohexylamino]ethane sulfonic acid; ; CE- β-CD – (2-carboxyethyl)- β-cyclodextrin; CTAB – cetyltrimethylammonium bromide; DHA – dehydroacetic acid; EP – ethylparaben; HIBA – 2-hydroxyisobutyric acid; HMB – hexane-1,6-bis(trimethylammonium) bromide; HP-γ-CD – 2-hydroxylpropyl-γ-cyclodextrin; iBP – isobutylparaben; MeOH – methanol; MES – 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid monohydrate; MOPSO – 3-morpholino-2-hydroxypropane-sulfonic acid; MP – methylparaben; PB – phosphate buffer; PEO – poly(ethylene oxide); PP – propylparaben; SA – salicylic acid; SDBS – sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate; SDS – dodecyl sulfate sodium salt; SOA – sorbic acid; TTAB – tetradecyltrimethylammonium bromide

References

-

Cosmetic Industry. The International Position of Polish Manufacturers and Market Development Forecasts until 2026 (in Polish).Department of Economic Analysis. PKO Bank Polski S.A.; 2023;

-

Cosmetic Poland. Report on the State of the Cosmetics Industry (in Polish). Polish Cosmetic Industry Association.; 2024;

- Hamilton, T.; de Gannes, G.C. Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Preservatives and Fragrances in Cosmetics. Skin Therapy Lett 2011, 16, 1–4.

- Cosmetics and Personal Care Application Notebook Analytical Testing Solutions for Cosmetics and Personal Care Products. Aplication Note, Waters Corporation, USA, 2016.

- Halla, N.; Fernandes, I.P.; Heleno, S.A.; Costa, P.; Boucherit-Otmani, Z.; Boucherit, K.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Barreiro, M.F. Cosmetics Preservation: A Review on Present Strategies. Molecules 2018, 23.

- Vigneshwaran, L.V.; Amritha, P.P.; Khaseera Farsana; Khairunnisa, T.; Sebastian, V.; Ajith Babu, T.K. A Review on Natural Colourants Used in Cosmetics. Current Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 13, 83–92.

- Babarus, I.; Lungu, I.-I.; Stefanache, A. Babarus 2023. International Journal of Development Research 2023, 13, 63654–63659.

- Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Werner, J.; Jeszka-Skowron, M.; Czarczyńska-Goślińska, B. Determination of Parabens in Cosmetic Products Using High Performance Liquid Chromatography with Fluorescence Detection. Analytical Methods 2016, 8, 3903–3909. [CrossRef]

- Rico, F.; Mazabel, A.; Egurrola, G.; Pulido, J.; Barrios, N.; Marquez, R.; García, J. Meta-Analysis and Analytical Methods in Cosmetics Formulation: A Review. Cosmetics 2024, 11.

- Ezegbogu, M.O.; Osadolor, H.B. Comparative Forensic Analysis of Lipsticks Using Thin Layer Chromatography and Gas Chromatography. International Journal of Chemical and Molecular Engineering 2019, 13, 231–235.

- Kang, E.K.; Lee, S.; Park, J.H.; Joo, K.M.; Jeong, H.J.; Chang, I.S. Determination of Hexavalent Chromium in Cosmetic Products by Ion Chromatography and Postcolumn Derivatization. Contact Dermatitis 2006, 54, 244–248. [CrossRef]

- Dutra, E.A.; Santoro, M.I.R.M.; Micke, G.A.; Tavares, M.F.M.; Kedor-Hackmann, E.R.M. Determination of α-Hydroxy Acids in Cosmetic Products by Capillary Electrophoresis. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2006, 40, 242–248. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, M.; Shao, Y.; Zhuang, Q. Comparative Study for the Analysis of Parabens by Micellar Electrokinetic Capillary Chromatography with and without Large-Volume Sample Stacking Technique. Talanta 2006, 69, 166–171. [CrossRef]

- Salvador, A.; Chisvert, A. Analysis of Cosmetic Products Using Different IR Spectroscopy Techniques. Analysis of Cosmetic Products 2007, LXVIII, 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Massadeh, A.M.; El-khateeb, M.Y.; Ibrahim, S.M. Evaluation of Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, and Pb in Selected Cosmetic Products from Jordanian, Sudanese, and Syrian Markets. Public Health 2017, 149, 130–137. [CrossRef]

- Farrag, E.; Abu-se’leek, M. Study of Heavy Metals Concentration in Cosmetics Purchased from Jordan Markets by ICP-MS and ICP-OES. International Journal of Applied Environmental Sciences 2015, 7, 383–393. [CrossRef]

- Lores, M.; Llompart, M.; Alvarez-Rivera, G.; Guerra, E.; Vila, M.; Celeiro, M.; Lamas, J.P.; Garcia-Jares, C. Positive Lists of Cosmetic Ingredients: Analytical Methodology for Regulatory and Safety Controls - A Review. Anal Chim Acta 2016, 915, 1–26.

- Abedi, G.; Talebpour, Z.; Jamechenarboo, F. Trends in Analytical Chemistry The Survey of Analytical Methods for Sample Preparation and Analysis of Fragrances in Cosmetics and Personal Care Products. Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2018, 102, 41–59. [CrossRef]

- Buszewski, B.; Dziubakiewicz, E.; Szumski, M. Electromigration Techniques. Theory and Practise; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2013; Vol. 105;

- Jorgenson, James, L.K. Zone Electrophoresis in Open-Tubular Glass Capillaries, ., 53(1981) 1298-1302. Anal Chem 1981, 53, 1298–1302.

- Gao, Z.; Zhong, W. Recent (2018-2020) Development in Capillary Electrophoresis. Anal Bioanal Chem 2022, 414, 115–130. [CrossRef]

- Jaywant, S.A.; Singh, H.; Arif, K.M. Capillary Zone Electrophoresis: Opportunities and Challenges in Miniaturization for Environmental Monitoring. Sens Biosensing Res 2024, 43.

- Tavares, M.F.M.; Jager, A. V; Da Silva, C.L.; Moraes, E.P.; Pereira, E.A.; De Lima, E.C.; Fonseca, F.N.; Tonin, F.G.; Micke, G.A.; Santos, M.R.; et al. Applications of Capillary Electrophoresis to the Analysis of Compounds of Clinical, Forensic, Cosmetological, Environmental, Nutritional and Pharmaceutical Importance. J Braz Chem Soc 2003, 14, 281–290. [CrossRef]

- Kubáň, P.; Dvořák, M.; Kubáň, P. Capillary Electrophoresis of Small Ions and Molecules in Less Conventional Human Body Fluid Samples: A Review. Anal Chim Acta 2019, 1075, 1–26.

- Wang, M.; Gong, Q.; Liu, W.; Tan, S.; Xiao, J.; Chen, C. Applications of Capillary Electrophoresis in the Fields of Environmental, Pharmaceutical, Clinical, and Food Analysis (2019–2021). J Sep Sci 2022, 45, 1918–1941.

- Gackowski, M.; Przybylska, A.; Kruszewski, S.; Koba, M.; Mądra-Gackowska, K.; Bogacz, A. Recent Applications of Capillary Electrophoresis in the Determination of Active Compounds in Medicinal Plants and Pharmaceutical Formulations. Molecules 2021, 26.

- Poboży, E.; Trojanowicz, M. Application of Capillary Electrophoresis for Determination of Inorganic Analytes in Waters. Molecules 2021, 26.

- Kuhn, R.; Hoffstetter-Kuhn, S. Capillary Electrophoresis: Principles and Practice; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1993;

- Pantsar-Kallio, M.; Manninen, P.K.G. Determination of Sodium, Potassium, Calcium and Magnesium Cations by Capillary Electrophoresis Compared with Ion Chromatography. Anal Chim Acta 1995, 314, 67–75.

- Haddad, P.R. Comparison of Ion Chromatography and Capillary Electrophoresis for the Determination of Inorganic Ions. J Chromatogr A 1997, 770, 281–290.

- Klimaszewska, K.; Konieczka, P.; Polkowska, Ż.; Górecki, T.; Namieśnik, J. Comparison of Ion Chromatography and Isotachophoresis for the Determination of Selected Anions in Atmospheric Wet Deposition Samples. Pol J Environ Stud 2010, 19, 93–99.

- Pacakova, V.; Stulık, K. Capillary Electrophoresis of Inorganic Anions and Its Comparison with Ion Chromatography. J Chromatogr A 1997, 789, 169–180.

- Kończyk, J.; Muntean, E.; Gega, J.; Frymus, A.; Michalski, R. Major Inorganic Anions and Cations in Selected European Bottled Waters. J Geochem Explor 2019, 197, 27–36. [CrossRef]

- Michalski, R. Applications of Ion Chromatography in Environmental Analysis. In Ion-Exchange Chromatography and Related Techniques; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 333–349.

- Muntean, E. Applications of Ion Chromatography in Food Analysis. In Ion-Exchange Chromatography and Related Techniques; Poole, C.F., Ed.; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 351–369.

- Michalski, R. Application of Ion Chromatography in Clinical Studies and Pharmaceutical Industry. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 2014, 14, 862–872. [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, F.; Senofonte, O. Determination of Cr(vi) in Cosmetic Products Using Ion Chromatography with Dynamic Reaction Cell-Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (DRC-ICP-MS). Analytical Methods 2015, 7, 5269–5274. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, F.; Liu, H.; Gao, Y. Determination of Hexachlorophene in Cosmetics by Capillary Electrophoresis Compared with High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Acta Chromatogr 2021, 33, 44–50. [CrossRef]

- Labat, L.; Kummer, E.; Dallet, P.; Dubost, J.P. Comparison of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Capillary Zone Electrophoresis for the Determination of Parabens in a Cosmetic Product. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2000, 23, 763–769. [CrossRef]

- Juang, L.J.; Wang, B. Sen; Tai, H.M.; Hung, W.J.; Huang, M.H. Simultaneous Identification of Eight Sunscreen Compounds in Cosmetic Products Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Capillary Electrophoresis. J Food Drug Anal 2008, 16, 22–28.

- Lin, W.C.; Lin, S.T.; Shu, S.L. Comparison of Analyses of Surfactants in Cosmetics Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and High-Performance Capillary Electrophoresis. J Surfactants Deterg 2000, 3, 67–72. [CrossRef]

- Katata, L.; Nagaraju, V.; Crouch, A.M. Determination of Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid , Ethylenediaminedisuccinic Acid and Iminodisuccinic Acid in Cosmetic Products by Capillary Electrophoresis and High Performance Liquid Chromatography. 2006, 579, 177–184. [CrossRef]

- Janečková, M.; Bartoš, M.; Lenčová, J. Isotachophoretic Determination of Triethanolamine in Cosmetic Products. Monatsh Chem 2019, 150, 387–390. [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.; Shi, P.; Li, J.; Wang, Q. Application of Graphene as Solid Phase Extraction Absorbent for the Determination of Parabens in Cosmetic Products by Capillary Electrophoresis. Anal Lett 2013, 46, 1991–2000. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Chen, N.; Luo, C.; Wang, X.; Sun, C. Simultaneous Determination of Seven Preservatives in Cosmetics by Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction Coupled with High Performance Capillary Electrophoresis. Analytical Methods 2013, 5, 2391–2397. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.C.; Wang, C.C.; Chen, Y.L.; Wu, S.M. Large Volume Sample Stacking with EOF and Sweeping in CE for Determination of Common Preservatives in Cosmetic Products by Chemometric Experimental Design. Electrophoresis 2012, 33, 1443–1448. [CrossRef]

- Uysal, U.D.; Güray, T. Determination of Parabens in Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Products by Capillary Electrophoresis. Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2008, 63, 982–986. [CrossRef]

- Dolzan, M.D.; Spudeit, D.A.; Azevedo, M.S.; Costa, A.C.O.; De Oliveira, M.A.L.; Micke, G.A. A Fast Method for Simultaneous Analysis of Methyl, Ethyl, Propyl and Butylparaben in Cosmetics and Pharmaceutical Formulations Using Capillary Zone Electrophoresis with UV Detection. Analytical Methods 2013, 5, 6023–6029. [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; He, Y.Z.; Yu, C.Z. On-Line Pretreatment and Determination of Parabens in Cosmetic Products by Combination of Flow Injection Analysis, Solid-Phase Extraction and Micellar Electrokinetic Chromatography. Talanta 2008, 74, 1371–1377. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, I.C.; Su, C.Y.; Hu, C.C.; Chiu, T.C. Simultaneous Determination of Whitening Agents and Parabens in Cosmetic Products by Capillary Electrophoresis with On-Line Sweeping Enhancement. Analytical Methods 2014, 6, 7615–7620. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Lai, Y.C.; Chiu, C.W.; Yeh, J.M. Comparing Micellar Electrokinetic Chromatography and Microemulsion Electrokinetic Chromatography for the Analysis of Preservatives in Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Products. J Chromatogr A 2003, 993, 153–164. [CrossRef]

- De Rossi, A.; Desiderio, C. Fast Capillary Electrochromatographic Analysis of Parabens and 4-Hydroxybenzoic Acid in Drugs and Cosmetics. Electrophoresis 2002, 23, 3410–3417. [CrossRef]

- Cabaleiro, N.; De la Calle, I.; Bendicho, C.; Lavilla, I. An Overview of Sample Preparation for the Determination of Parabens in Cosmetics. TrAC - Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2014, 57, 34–46. [CrossRef]

- Maijó, I.; Borrull, F.; Aguilar, C.; Calull, M. Different Strategies for the Preconcentration and Separation of Parabens by Capillary Electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 2013, 34, 363–373. [CrossRef]

- Babilas, P.; Knie, U.; Abels, C. Cosmetic and Dermatologic Use of Alpha Hydroxy Acids. JDDG - Journal of the German Society of Dermatology 2012, 10, 488–491.

- Karwal, K.; Mukovozov, I. Topical AHA in Dermatology: Formulations, Mechanisms of Action, Efficacy, and Future Perspectives. Cosmetics 2023, 10.

- Wang, H.; Sun, M.; Qu, F. Simultaneous Analysis of Five Organic Acids in Aqueousm Lotion, and Cream Cosmetics by Capillary Electrophoresis. Chinese Journal of Chromatography 2019, 37, 773–777.

- Liu, P.Y.; Lin, Y.H.; Feng, C.H.; Chen, Y.L. Determination of Hydroxy Acids in Cosmetics by Chemometric Experimental Design and Cyclodextrin-Modified Capillary Electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 2012, 33, 3079–3086. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Jiang, S.J.; Feng, C.H.; Wang, S.W.; Lin, Y.H.; Liu, P.Y. Application of Central Composite Design for the Determination of Exfoliating Agents in Cosmetics by Capillary Electrophoresis with Electroosmotic Flow Modulation. Anal Lett 2014, 47, 1670–1682. [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Kou, H.; Lin, Y.; Wang, C. The Matrix of SDS Integrated with Linear Hydrophilic Polymer for Resolution of High- and Low-Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acids in MEKC. J Food Drug Anal 2019, 28, 159–166. [CrossRef]

- Chindaphan, K.; Wongravee, K.; Nhujak, T.; Dissayabutra, T.; Srisa-Art, M. Online Preconcentration and Determination of Chondroitin Sulfate, Dermatan Sulfate and Hyaluronic Acid in Biological and Cosmetic Samples Using Capillary Electrophoresis. J Sep Sci 2019, 42, 2867–2874. [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.R.R.C.; López-García, P.; Tavares, V.F.; Almeida, M.M.; Zanolini, C.; Aurora-Prado, M.S.; Santoro, M.I.R.M.; Kedor-Hackamnn, E.R.M. Separation and Identification of Fatty Acids in Cosmetic Formulations Containing Brazil Nut Oil by Capillary Electrophoresis. Revista de Ciencias Farmaceuticas Basica e Aplicada 2011, 32, 341–348.

- Amorim, T.L.; Pena, M.G.D.R.; Costa, F.F.; De Oliveira, M.A.L.; Chellini, P.R. A Fast and Validated Capillary Zone Electrophoresis Method for the Determination of Selected Fatty Acids Applied to Food and Cosmetic Purposes. Analytical Methods 2019, 11, 5607–5612. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, S.; Amariei, G.; Boltes, K.; García, M.Á.; Marina, M.L. Enantiomeric Separation of Panthenol by Capillary Electrophoresis. Analysis of Commercial Formulations and Toxicity Evaluation on Non-Target Organisms. J Chromatogr A 2021, 1639. [CrossRef]

- Bojarowicz, H.; Bartnikowska, N. Sunscreen Cosmetics. Part I. UV Filters and Their Properties. Probl Hig Epidemiol 2014, 5, 596–601.

- Wang, S.P.; Lee, W.T. Determination of Benzophenones in a Cosmetic Matrix by Supercritical Fluid Extraction and Capillary Electrophoresis. J Chromatogr A 2003, 987, 269–275. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Chiu, C.W.; Chen, Y.C.; Yeh, J.M. Comparison of Microemulsion Electrokinetic Chromatography and Micellar Electrokinetic Chromatography as Methods for the Analysis of Ten Benzophenones. Electrophoresis 2005, 26, 895–902. [CrossRef]

- Klampfl, C.W.; Leitner, T.; Hilder, E.F. Development and Optimization of an Analytical Method for the Determination of UV Filters in Suntan Lotions Based on Microemulsion Electrokinetic Chromatography. Electrophoresis 2002, 23, 2424–2429. [CrossRef]

- Sha, B.B.; Yin, X.B.; Zhang, X.H.; He, X.W.; Yang, W.L. Capillary Electrophoresis Coupled with Electrochemical Detection Using Porous Etched Joint for Determination of Antioxidants. J Chromatogr A 2007, 1167, 109–115. [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Chu, Q.; Fu, L.; Ye, J. Determination of Antioxidants in Cosmetics by Micellar Electrokinetic Capillary Chromatography with Electrochemical Detection. J Chromatogr A 2005, 1074, 201–204. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xia, L.; Xiao, X.; Li, G. Enhanced Capillary Zone Electrophoresis in Cyclic Olefin Copolymer Microchannels Using the Combination of Dynamic and Static Coatings for Rapid Analysis of Carnosine and Niacinamide in Cosmetics. J Sep Sci 2022, 45, 2045–2054. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Wu, S.M. Simultaneous Determination of L-Ascorbic Acid, Ascorbic Acid-2-Phosphate Magnesium Salt, and Ascorbic Acid-6-Palmitate in Commercial Cosmetics by Micellar Electrokinetic Capillary Electrophoresis. Anal Chim Acta 2006, 576, 124–129. [CrossRef]

- Masukawa, Y. Separation and Determination of Basic Dyes Formulated in Hair Care Products by Capillary Electrophoresis. J Chromatogr A 2006, 1108, 140–144. [CrossRef]

- Gładysz, M.; Król, M.; Mystek, K.; Kościelniak, P. Application of Micellar Electrokinetic Capillary Chromatography to the Discrimination of Red Lipstick Samples. Forensic Sci Int 2019, 299, 49–58. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Qi, L.; Li, Y.; Qiao, J.; Wang, M. Separation of Aromatic Amines by an Open-Tubular Capillary Electrochromatography Method. J Sep Sci 2013, 36, 3629–3634. [CrossRef]

- Soriano, M.L.; Ruiz-Palomero, C.; Valcárcel, M. Ionic-Liquid-Based Microextraction Method for the Determination of Silver Nanoparticles in Consumer Products. Anal Bioanal Chem 2019, 411, 5023–5031. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Girón, A.B.; Crego, A.L.; González, M.J.; Marina, M.L. Enantiomeric Separation of Chiral Polycyclic Musks by Capillary Electrophoresis: Application to the Analysis of Cosmetic Samples. J Chromatogr A 2010, 1217, 1157–1165. [CrossRef]

- Zajda, J.; Wadych, E.; Ogórek, K.; Drozd, M.; Matczuk, M. Novel Applications of CE-ICP-MS/MS: Monitoring of Antiaging GHK–Cu Cosmetic Component Encapsulation in Liposomes. Electrophoresis 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Yu, M.; Cao, Y.; Cao, G. Microstructure of Microemulsion Modified with Ionic Liquids in Microemulsion Electrokinetic Chromatography and Analysis of Seven Corticosteroids. Electrophoresis 2013, 34, 2568–2576. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.L.; Jiang, S.J.; Chen, Y.L. Determining Lead, Cadmium and Mercury in Cosmetics Using Sweeping via Dynamic Chelation by Capillary Electrophoresis. Anal Bioanal Chem 2017, 409, 2461–2469. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Tong, S.; Chang, Y.; Jia, Q.; Zhou, W. Ionic Liquid-Based Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction with Back-Extraction Coupled with Capillary Electrophoresis to Determine Phenolic Compounds. Electrophoresis 2012, 33, 1331–1338. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).