1. Introduction

Pyoderma Gangrenosum (PG) is a rare inflammatory skin disease, classified within the group of neutrophilic dermatoses, clinically characterized by painful, rapidly evolving [

1] cutaneous ulcers with undermined, irregular, erythematous-violaceous borders and seropurulent exudate [

2]. Epidemiologically, it affects 6 individuals per 100,000 globally [

3]. Specifically, Peristomal Pyoderma Gangrenosum (PPG) occurs in the skin surrounding the stoma and accounts for 15% of PG cases, affecting approximately 0.5-1.5% of stoma patients, particularly those with ileostomies4. The etiology remains uncertain and may precede, coexist with, or follow various systemic diseases, such as Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). The low incidence complicates the definition of diagnostic and therapeutic approaches [

5]. Diagnosis relies on the patient's medical history, typical cutaneous presentation, histopathological findings (biopsy is indicative of edema, massive neutrophil infiltration in the dermis, and small vessel vasculitis) [

4,

6], and the exclusion of other etiologies [

7]. Treatment focuses on suppressing inflammatory disease activity, managing associated morbidities, promoting lesion healing, and alleviating pain, necessitating a multidisciplinary team approach for optimal care objectives [

8]. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) [

9] is one treatment option for PG, though evidence for its sole use in PPG is lacking. This case study discusses the management of a PPG lesion in an ileostomy patient using NPWT exclusively.

2. Materials and Methods

CASE

Background

This case report concerns a 43-year-old male with a significant past medical history of Hashimoto's thyroiditis, severe acquired aplastic anemia, superficial venous thrombosis of the right upper limb, and Crohn's Disease. Following the progression of chronic inflammatory pathology, the patient underwent total videolaparoscopic total colectomy with the formation of a likely permanent end ileostomy on September 15, 2022. A follow-up for Crohn's Disease was planned without indications for future restorative surgery.

Initial Assessment

Nearly two months post-surgery (November 12, 2022), the patient reported pain and burning in the skin near the stoma and was evaluated in the stoma care clinic for the emergence of a peristomal skin lesion. The enterostomal therapist diagnosed an ulcerative lesion with a S.A.C.S. (Multicenter Observational Study on Stomal Skin Disorders) [

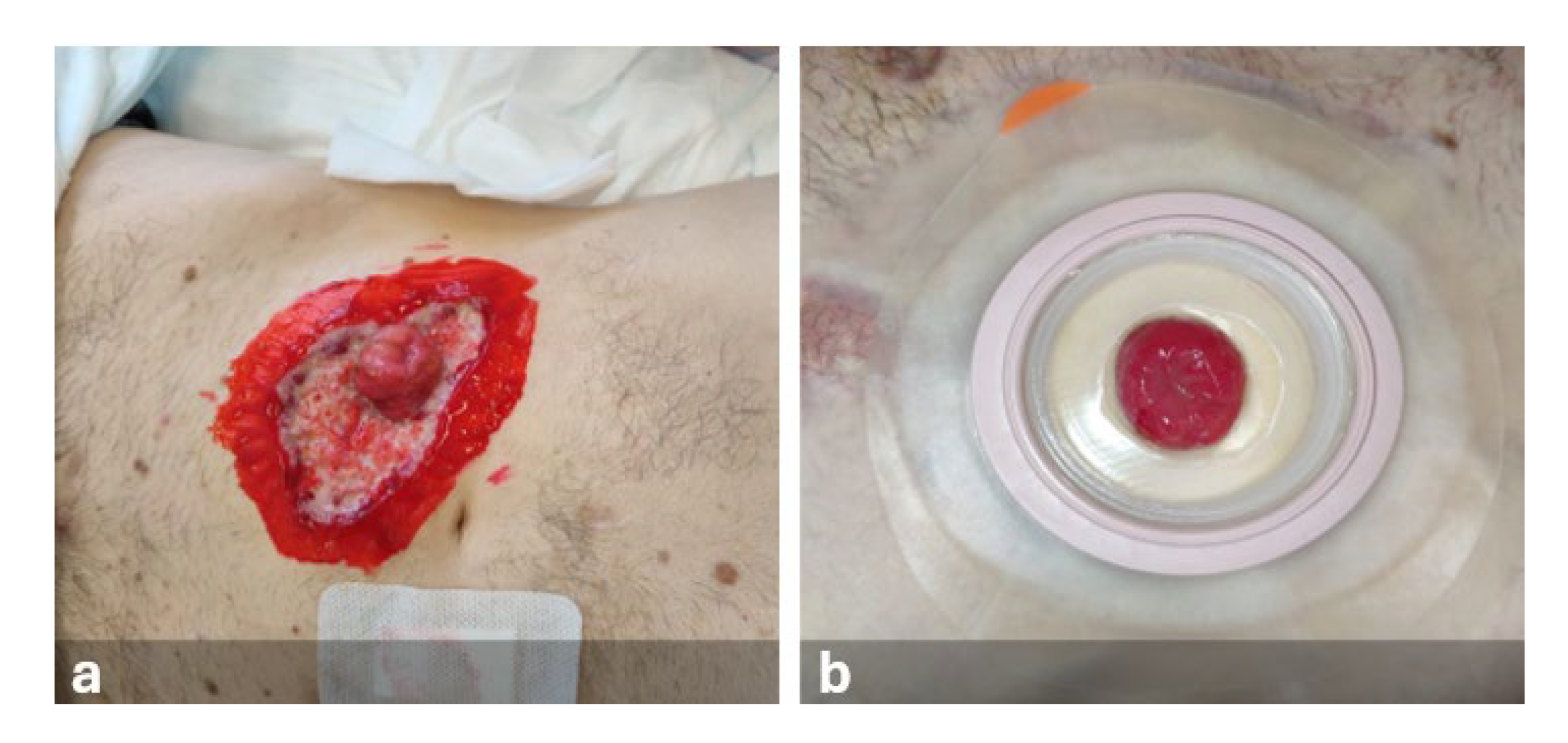

10] classification of L3-TIV. Upon reevaluation, the lesion showed rapid substance loss evolution, with undermined, irregular, erythematous-violaceous margins and the presence of exudate (

Figure 1).

A dermatology consultation was requested, leading to a suspected diagnosis of septic ulcer or probable PPG. Surgical consultation with a biopsy of the lesion was performed. Ten days after the lesion's appearance, a definitive diagnosis of PPG was made, confirmed by the stoma therapist's assessment and the surgical biopsy report. Gastroenterology consultation allowed the patient to immediately start systemic therapy in a hospital setting, and topical therapy with 2% Aqueous Eosin solution was prescribed by the dermatologist. In this condition, stoma accessories were used, and the stoma was managed with a two-piece appliance (flat plate and open-ended bag) (

Figure 2).

The enterostomal therapist, after reviewing the relevant literature, organized a multidisciplinary meeting, highlighting the importance of using Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT), although no prior experience in treating PPG with this method was reported.

First NPWT Application

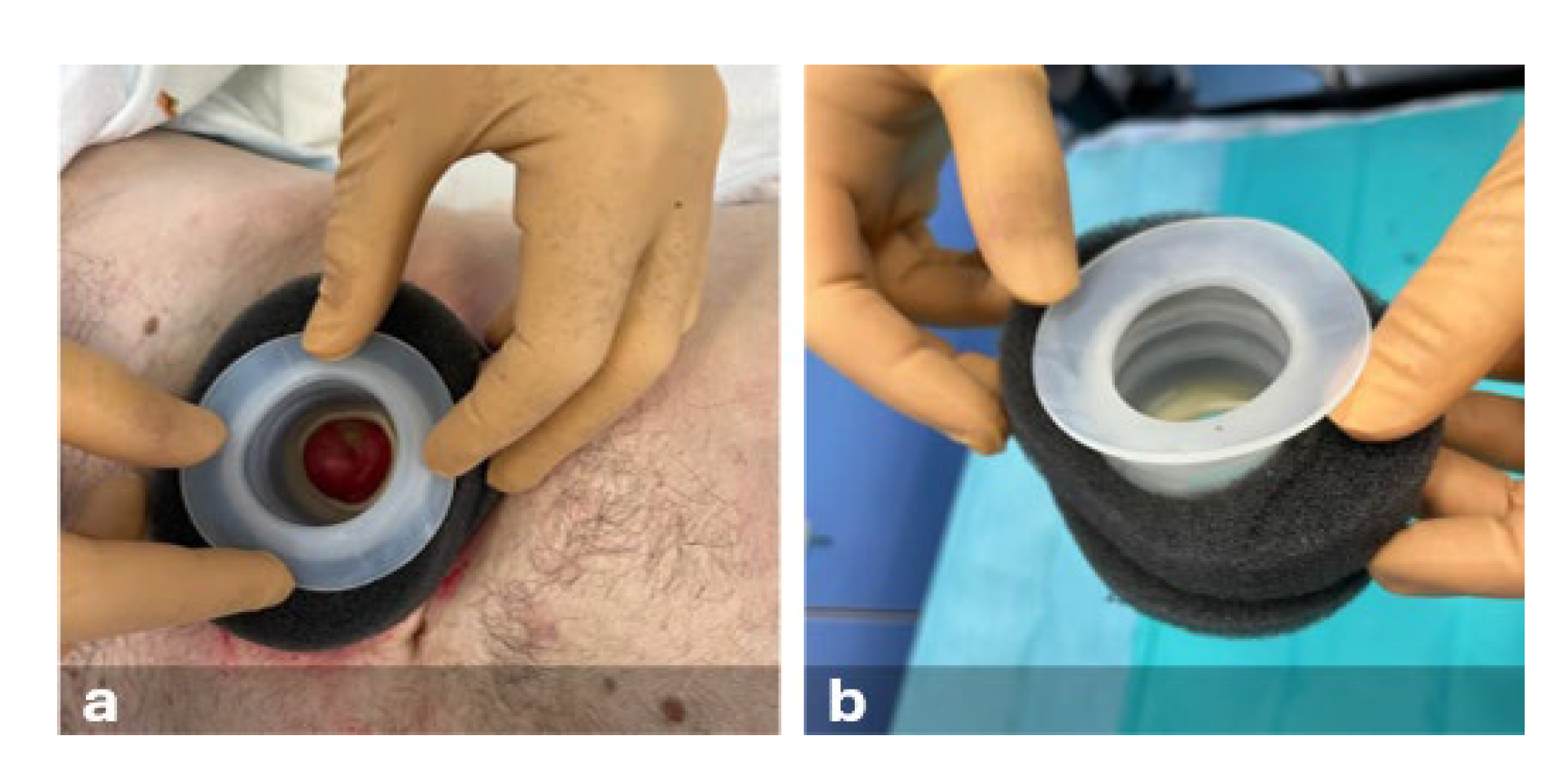

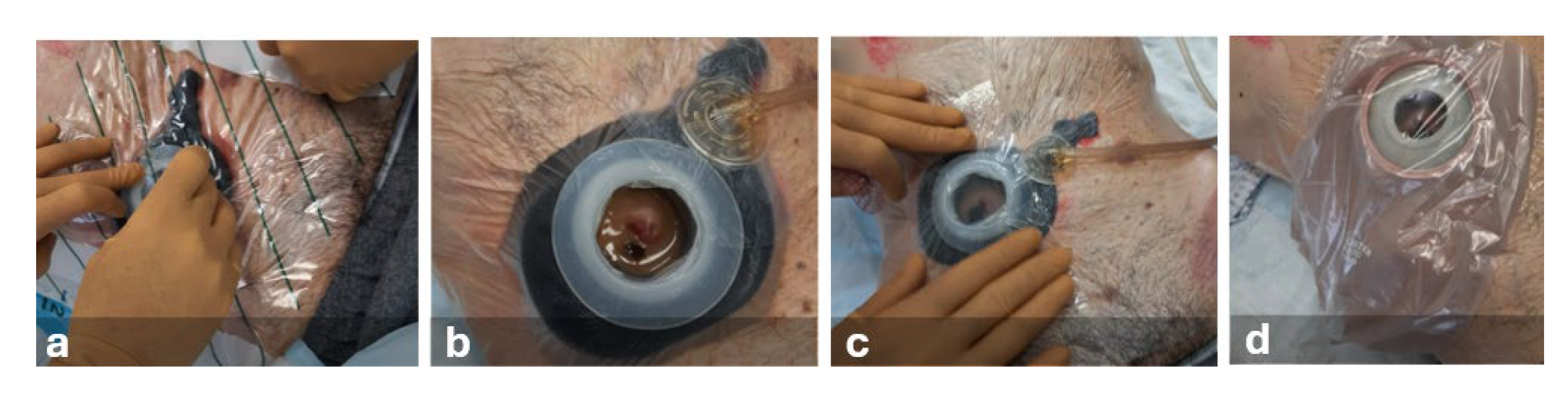

During hospitalization, Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) was applied to the lesion 35 days after its onset (

Figure 3).

Following peristomal skin cleansing, protective film, barrier paste, moldable hydrocolloid ring, and a non-adherent dressing (composed of rayon-viscose filament fabric impregnated with petrolatum) were used. Subsequently, a thermoplastic elastomer device was placed around the stoma to isolate the lesion from fecal matter. To ensure an airtight seal, a polyurethane foam dressing and acrylic silicone film were applied. The pad was positioned in situ and connected to the NPWT device set to continuous pressure (-50 mmHg). A two-piece stoma appliance with a flat plate and an open-ended bag was used (

Figure 4).

During hospitalization, dressing changes were carried out every 3 days, following intravenous administration of an analgesic (Ketorolac tromethamine) to minimize procedure-related discomfort. Confident in the integrity of the collection appliance and dressing, the patient was able to mobilize with the NPWT device and independently manage fecal bag emptying.

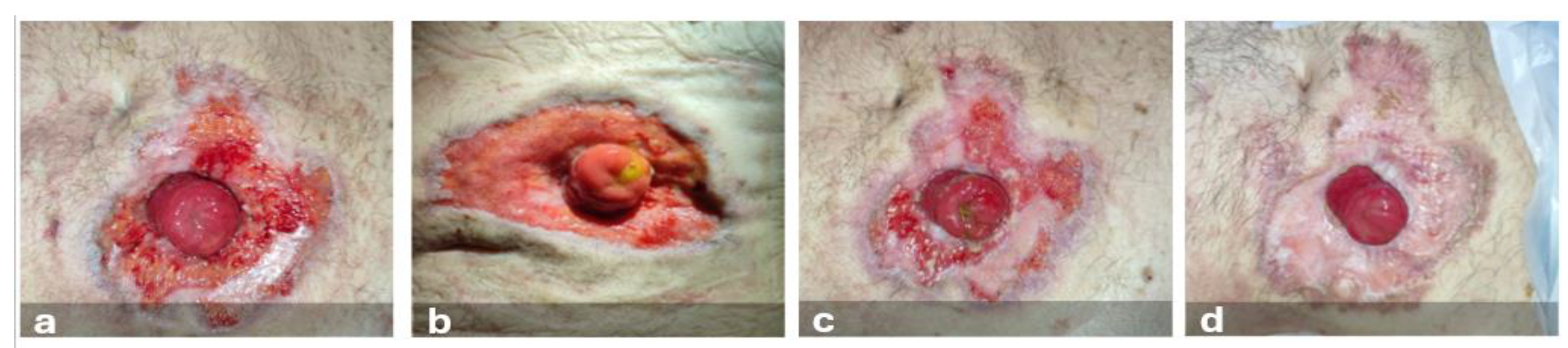

Post-Discharge

The patient's discharge was facilitated by the use of a portable homecare device, allowing daily activities to be performed. Dressing changes were conducted every 6 days at the stoma clinic, with continuous negative pressure set at -100 mmHg. Three months post-lesion onset, skin integrity was restored with scarring-related heterogeneity. The stoma appeared pink, round, functional, vital, and prolapsed above the skin level (

Figure 5).

The patient independently resumed managing the stoma complex with protective film, barrier paste, hydrocolloid ring, and a two-piece appliance with a soft convexity plate and an open-ended bag.

3. Results

The treatment weeks were both challenging and rewarding. It was the first experience using NPWT for PPG, with uncertain outcomes. Therapy and care objectives were achieved, thanks in part to the patient's compliance, the professional development outcome, and the exchange and discussion within the multidisciplinary team. Through scientific literature review, the team gained clearer insights on NPWT's benefits for patients, despite the lack of specific documentation on PPG treatment.

This treatment was selected for its mechanism of action, which increases local blood flow in the skin, reduces interstitial edema, and controls exudate. It also promotes granulation tissue formation, cellular proliferation (fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle), and wound edge approximation. Advantages include ease of use, effectiveness, cost-efficiency, and bacterial load reduction [

11,

12].

NPWT treatment and the use of a device to isolate the stoma from effluents allowed stoma preservation, maintaining its functionality and protrusion throughout the treatment, despite literature describing numerous cases resolved through surgical intervention and stoma re-siting.

The PPG diagnosis was not immediate but followed the rapid lesion evolution, highlighting PPG's diagnostic features (substance loss, undermined, irregular, erythematous-violaceous margins, presence of exudate), specialist consultations, biopsy report, and patient history; PPG is often associated with IBD [

13].

Resolution typically occurs within 9 months, and literature recommends skin grafting for complete healing [

1,

14], whereas, in our case study, this outcome was achieved in 3 months solely with NPWT.

5. Conclusions

Outpatient management led to reduced hospitalization times, optimizing nursing time and resource use. It also significantly impacted the patient's and their family's quality of life. Restoring skin integrity required synergy among the multidisciplinary team professionals, coordinated by the enterostomal therapist case manager, who adopted a holistic nursing approach in case management. Complete healing allowed the patient to resume their daily routine in stoma care and peristomal skin care, following the stoma therapist's advice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at Preprints.org, Supplementary Materials 1—interview guide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization (RNZB and CIAG); methodology (RNZB, CIAG); formal analysis (CIAG); investigation (RNZB, and CIAG); data curation (and CIAG); writing—original draft (CIAG); writing—review and editing (RNZB, and CIAG); visualization (RNZB); supervision (CIAG); project administration (CIAG). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Committee of the Cagliari University Hospital (date of approval 20/07/2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was written following the recommendations of the COREQ guide for qualitative research reporting (Tong, 2007).

Use of Artificial Intelligence

ChatGPT4O and Grammarly has been used for language translation, language and grammar editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

SUMMARY

Our experience advocates for the use of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) in treating Peristomal Pyoderma Gangrenosum skin lesions.

KEY POINTS

Management by a multidisciplinary team ensures effective and safe patient care.

Negative pressure therapy accelerates the healing of peristomal skin lesions.

Knowledge of specialized stoma devices is crucial in cases of peristomal lesions with substance loss.

References

- Toh JWT, Young CJ, Rickard MJFX, Keshava A, Stewart P, Whiteley I. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: 12-year experience in a single tertiary referral centre. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88(10). [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Prenner J, Wang W, et al. Risk factors and treatment outcomes of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51(12):1365-1372. [CrossRef]

- Rick J, Gould LJ, Marzano AV, et al. The “Understanding Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Review and Assessment of Disease Effects (UPGRADE)” Project: a protocol for the development of the core outcome domain set for trials in pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Derm Res. 2022;315(4):983-988. [CrossRef]

- Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Matsuoka H, et al. Clinical features and management of parastomal pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 2012;85(4):295-301. [CrossRef]

- Barton VR, Le ST, Wang JZ, Toussi A, Sood A, Maverakis E. Peristomal ulcers misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum: a common error. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(2). [CrossRef]

- Afifi L, Sanchez IM, Wallace MM, Braswell SF, Ortega-Loayza AG, Shinkai K. Diagnosis and management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(6):1195-1204.e1. [CrossRef]

- Janowska A, Oranges T, Fissi A, Davini G, Romanelli M, Dini V. PG-TIME : A practical approach to the clinical management of pyoderma gangrenosum. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(3). [CrossRef]

- O’Brien SJ, Ellis CT. The management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum in IBD. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(7):881-884. [CrossRef]

- DeFilippis EM, Feldman SR, Huang WW. The genetics of pyoderma gangrenosum and implications for treatment: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(6):1487-1497. [CrossRef]

- Bosio G, Pisani F, Lucibello L, et al. A proposal for classifying peristomal skin disorders: results of a multicenter observational study. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2007;53(9):38-43.

- Maculotti D, Dassenno. Management of peristomal skin complications with negative pressure wound therapy: A case study. Anat Physiol. 2016;06(03). [CrossRef]

- Normandin S, Safran T, Winocour S, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy: Mechanism of action and clinical applications. Semin Plast Surg. 2021;35(3):164-170. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa NS, Tolkachjov SN, el-Azhary RA, et al. Clinical features, causes, treatments, and outcomes of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) in 44 patients: The Mayo Clinic experience, 1996 through 2013. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(5):931-939. [CrossRef]

- Maronese CA, Pimentel MA, Li MM, Genovese G, Ortega-Loayza AG, Marzano AV. Pyoderma gangrenosum: An updated literature review on established and emerging pharmacological treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(5):615-634. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).