1. Introduction

Refrigerator and air conditioner are the most significant energy consuming appliance in a typical household. To save the energy, a high efficiency refrigerator is needed to be developing. Magnetic Refrigeration (MR) [

1] at room temperature is a good alternative to replace a gas compression refrigeration system [

2], because it is environmentally friendly without using the global warm coolant gases, and much higher thermal efficiency can be achieved. The MR technology uses the magnetocaloric effect (MCE) to generate cooling capacity through a regenerative process via Active Magnetic Refrigeration (AMR) materials [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Although active magnetic refrigeration provides high energy efficiency without using gaseous refrigerant, the components, especially the magnet field source and the magnetocaloric regenerator, are still very expensive at present [

1,

2,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. During the thermal cycle, if a higher magnetic field can be applied on AMR material, the higher the cooling power will be achieved. Two parts of magnetic materials in the MR design should be considered, the magnetic field generator and the AMR materials. For generating applied magnetic field, permanent magnet using Nd-Fe-B, which possesses quite strong M-H loop is the best choice. However, it is an expansive material. Thus, it is of the utmost importance to carefully optimize the design of any device to minimize the waste of magnetic materials. For the selection of AMR material, there are many materials can be operated around room temperature [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], most of them are compounds and developing cracks due to million times of fatigue cycles. In practical, gadolinium (Gd) which is a single element and a most reliable AMR material with a reasonable MCE coefficient at room temperature. In this study, we select Gd as AMR material. Two types of MR machines, namely, the reciprocal type and a rotary type, were commonly used today. Usually, the rotary type is more energy saving due to the continuous mass flow without stopping and reversing the heavy magnet at the ends. Therefore, in this work, only the rotary type is considered here.

In the past few years, J.F. Beltran-Lopez et al. [

13] optimized the magnetic strength by arranging the design the magnetic poles. However, the thermal-hydraulic dynamics was not considered at the same time. The research group of D. Eriksen et al. [

14] took the heat transfer of the fluid flow into consideration and optimize the magnetic design. But, the design with dynamics of duty cycle in each magnetization/demagnetization was not thoroughly studied. In the rotating cooling refrigeration system, to understand the magnetic field distribution in each cycle is important. Since cooling water is circulated adjacent to the AMR material during the magnetization and de-magnetization interval in each cycle, the flow pattern must match this cycle to achieve the highest cooling power. For an ideal case of rotary type MR, the best cycle should be 50% from thermo-hydraulic point of view alone. However, to design a rotating cylindrical magnet with a 50% magnetization and 50% de-magnetization cycle without loss of magnetic field is difficult to achieve. Magnetic field loss at high duty cycle in a typical rotary type MR is inevitable. An optimal duty cycle to gain the highest cooling power is needed to be investigated, which is the major focus of this work.

2. Materials and Design of the Regenerator Material System

In this study, we choose Gd as the magnetocaloric material. The basic design of the rotary type magnetic refrigeration is following the work of R. Bjork et al., and T. Okamura et al., [

1,

4,

12]. A cylindrical magnet with stationary outer iron yoke and a rotating inner pole is used in the rotary type MR. A pile of equally spaced thin Gd sheets acted as AMR materials are inserted into the gap between rotating inner rotor and static yoke. Between the gaps of Gd sheets, the coolant flows through and transfers the heat from or to AMR materials. The AMR device is designed such that the magnet must provide two magnetization regions and two demagnetization regions in each circle. During the rotation, heat transferring fluid flowing between the plates is running in alternating directions to the inlet or outlet of the flow control system. The time of fluid flowing in and out are arranged so that the flow is in phase with the magnetization and demagnetization cycle of the Gd plates in the different regions of the magnet [

9].

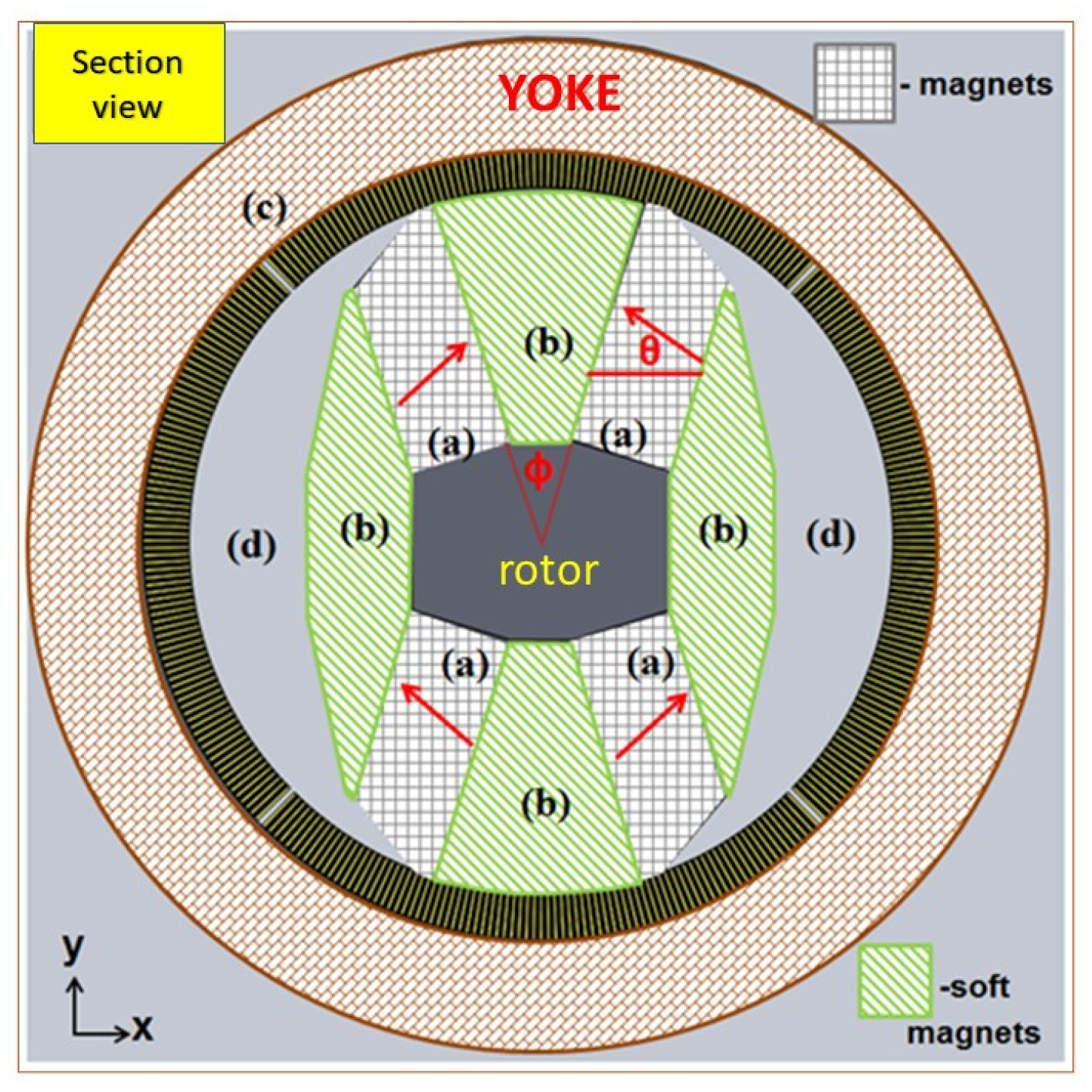

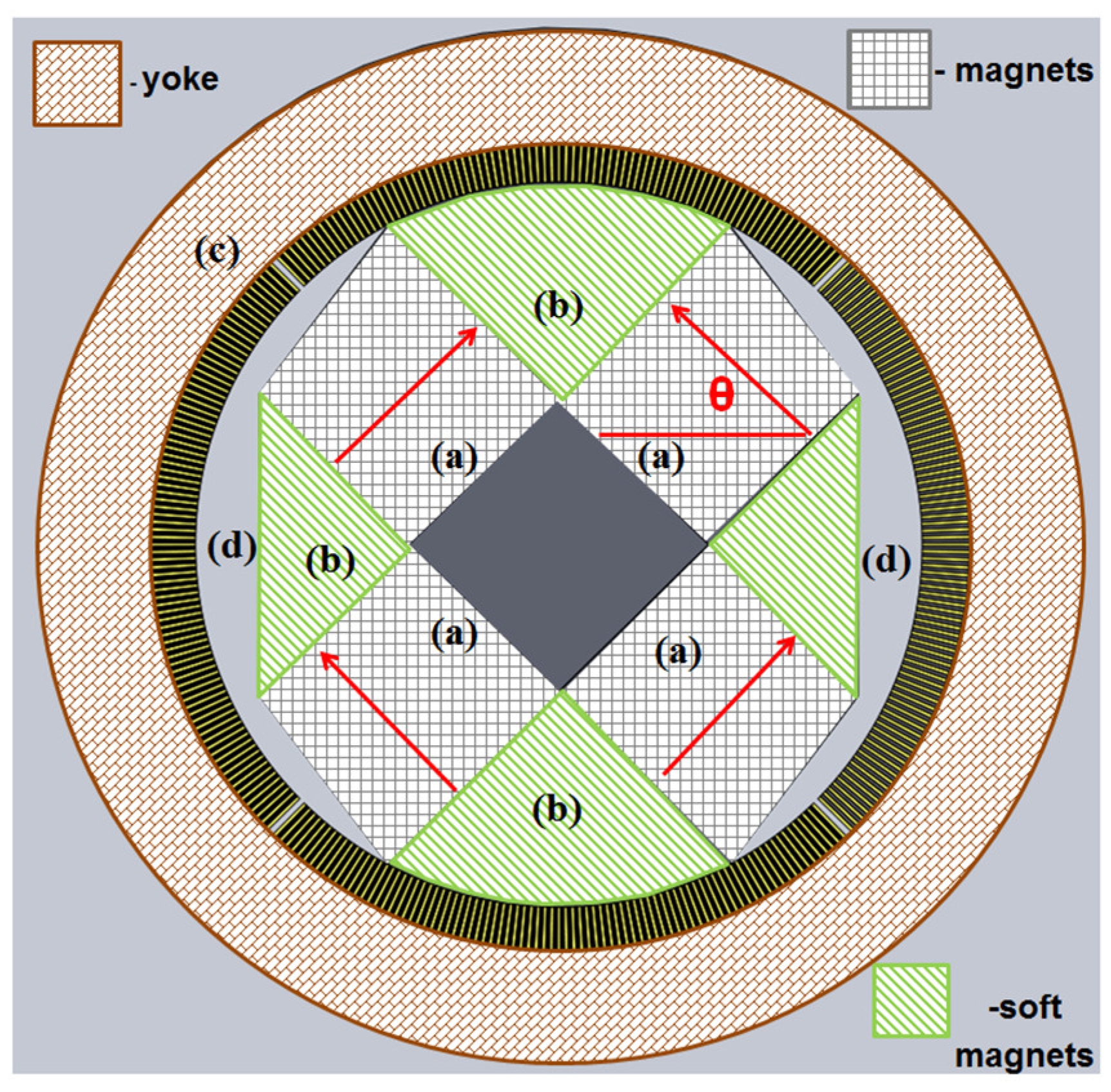

Figure 1 shows the cross-section of the modeling cylindrical magnet in detail. In this figure, the light gray regions (a) are Nd-Fe-B magnets; the light green regions (b) are steel poles (made of steel AISI 1008); the light brown region (c) is the iron yoke (AISI 1008); the yellow region (d) and other regions are air; the black stripe set between iron yoke and the steel pole is Gd. The dimension of cylindrical magnet studied here is 291 mm in diameter and 200 mm in length to mimic the original design of T. Okamura et al. [

12]. The rotating core consists of Nd-Fe-B (N52) magnets around the steel pole. The width of Nd-Fe-B is around 30 mm. the directions of Gd plates is placed axially, and the gap between iron yoke and inner magnet is 15 mm. The magnetization directions of NdFeB magnets are indicated by arrows in the figure. In

Figure 1, the AMR material is separated into four parts, defined as Gd

up, Gd

down, Gd

left and Gd

right around the circumference of cylindrical magnet. In this configuration, when the Gd

up and Gd

down are magnetized, the Gd

left and Gd

right are demagnetized. The cooling fluid (water) is flowing in the gap of Gd plates along the direction parallel to the axis of the cylindrical magnet. The rotation frequency of the rotor is 1 Hz and the water flow direction are switched every 0.5 s. In the first half part of the cycle, the hot water flowing in the gap of Gd plates when the Gd is in de-magnetization stage, while the cold water flows into the gap during the magnetization at the other part of cycle. A study of maximum magnetic field strength with a best magnetization time in a cycle was carried out to maximize the cooling power of this magnetic cooling system. As in

Figure 1, the magnetization directions of Nd-Fe-B magnets are labeled by arrows. We also define θ as magnetization angle and ϕ as the arc of pole face subtended angle (pole face angle). A study of magnetic field strength as a function of magnetization angles and pole face angles were carried out in order to achieve the best magnetic strength for the AMR material.

3. The Setting of Simulation

The numerical 3-dimensional calculation of the magnetic field of the rotary magnet structure is carried by the software COMSOL [

15]. In the calculation, the magnetic field distribution in each domain is determined by solving the Maxwell equations for the structure with proper magnetic properties. The operation point of Nd-Fe-B magnets are determined by a temperature-dependent load in the magnetic circuit. During the magnetic field analysis, the cylindrical magnet is placed in a three- dimensional air box. The boundary condition of this air box is to make the magnetic flux conservation. A typical calculating result based on the configuration of

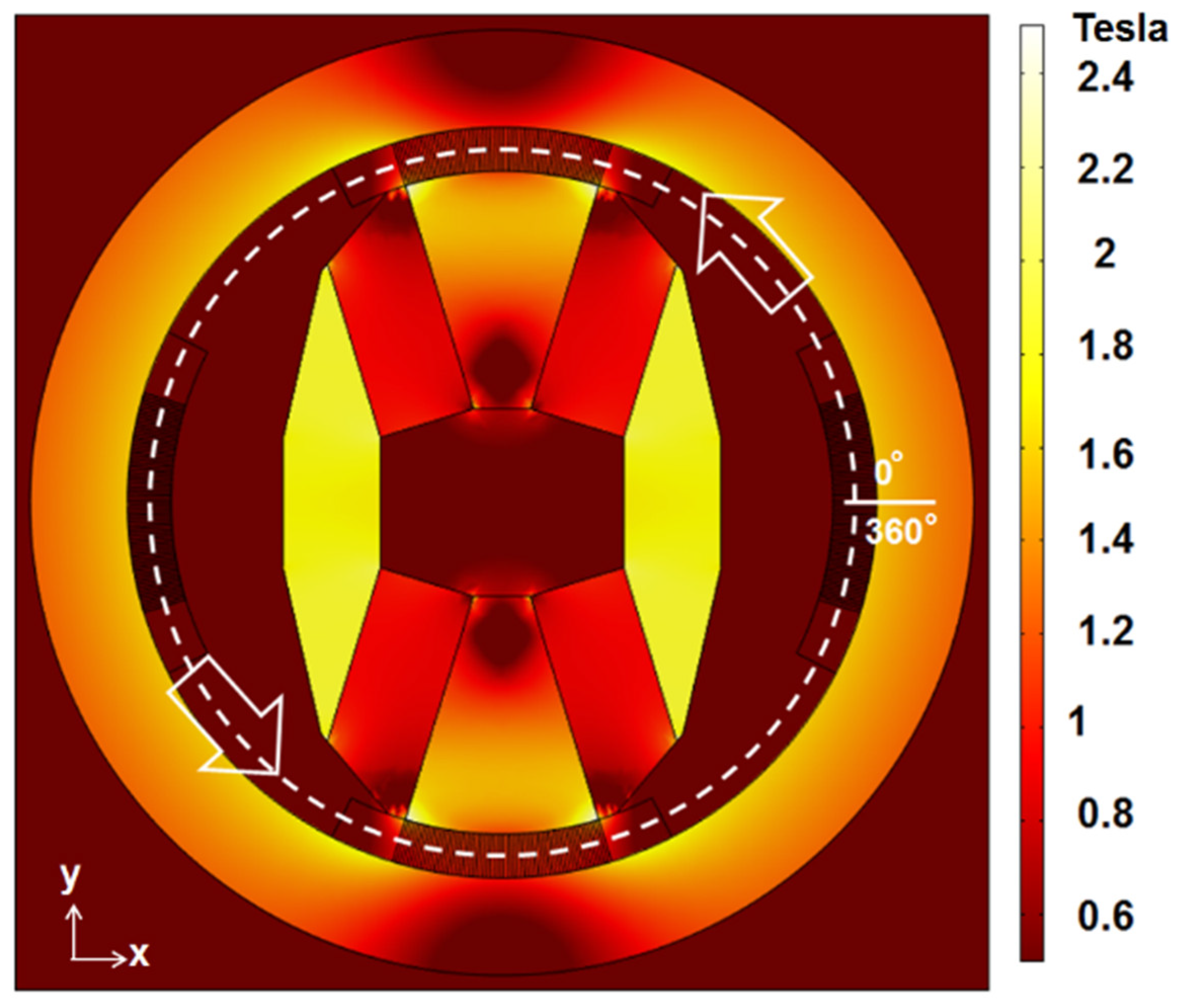

Figure 1 is shown in

Figure 2. Furthermore, the magnetic field distributions as functions of θ and ϕ, were determined.

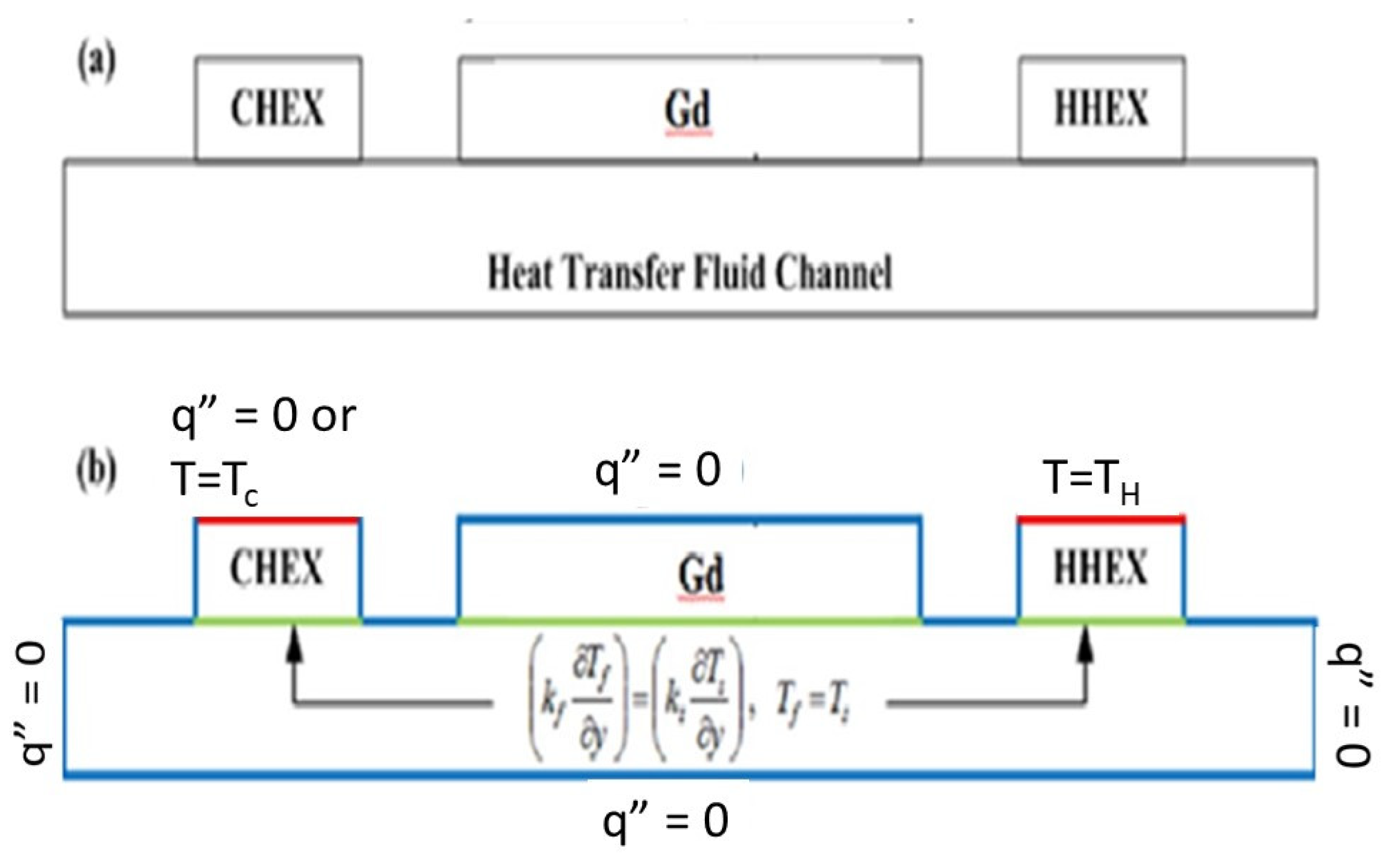

The thermal-hydraulic analysis of the system is also conducted using the COMSOL software. The geometry and heat transfer boundary conditions are illustrated in

Figure 3.

Figure 3(a) shows the simplified 2-D geometry considered in this study. The structure is axisymmetric, with the bottom boundary representing the centerline of the water channel. HHEX and CHEX refer to the heat exchangers on the hot and cold sides, respectively.

Figure 3(b) shows the boundary conditions considered in the thermal-hydraulic analysis. This is a time-dependent analysis that involves the coupling of (1) the magnetocaloric effects in the regenerator, (2) the heat transfer between the regenerator and the water in the channel, (3) the flow of water in the channel, and (4) the heat transfer between the water in the channel and the heat exchangers. All steps of the AMR refrigeration cycle are simulated, and the thermodynamic performance is evaluated in terms of cooling capacity and the temperature span between the two heat exchangers. The simulation process begins by determining the velocity profile of the water in the channel, followed by modeling the magnetization and de-magnetization effects in the regenerator. Next, the heat transfer between the regenerator and the water in the channel, as well as the heat transfer between the water and the heat exchangers, is analyzed. Finally, the thermodynamic performance of the AMR refrigeration cycle is calculated. The velocity profile of the water in the channel is determined by solving the momentum and continuity equations for an incompressible fluid with constant properties. The volume of water flowing past the regenerator during both the magnetization and demagnetization steps remains the same. Meanwhile, the temperature distribution in the channel is determined by solving the coupled heat transfer equations. For a detailed simulation process of the thermal-hydraulic analysis, please refer to the work of T. F. Petersen et al. [

16]

4. Results and Discussions

Table 1 summarizes the results of the maximum magnetization and the duty cycles can be achieved. Here, the magnetic duty cycle is defined by the percentage of time interval that magnetic field reach 90% of the maximum magnetic field. The duty cycle is related to the pole face angle ϕ in

Figure 1. At beginning of calculation, we keep the amount of Nd-Fe-B material fixed to find the maximum magnetic field as functions of ϕ and θ. A typical result of magnetic field strength under the configuration of

Figure 1 is shown in

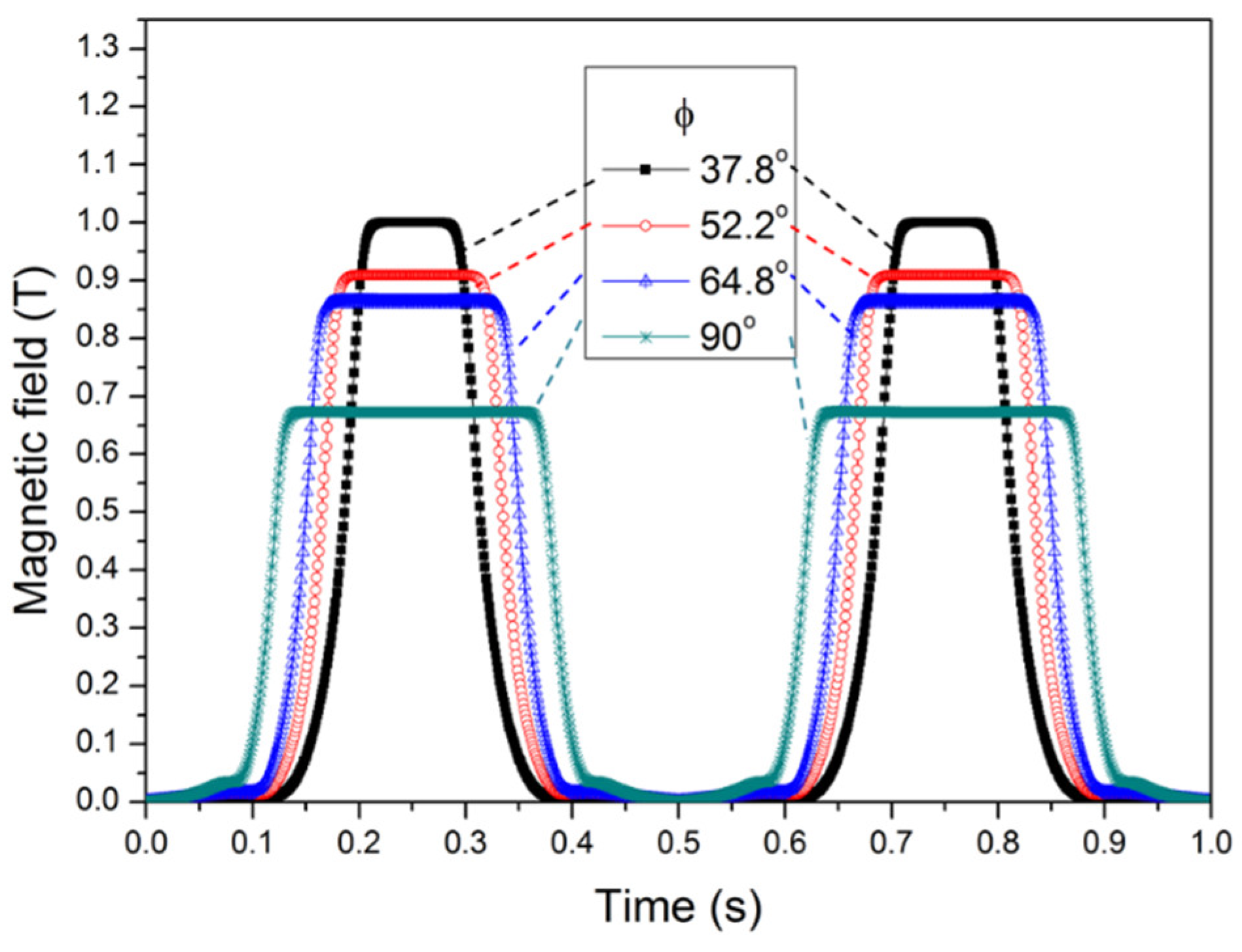

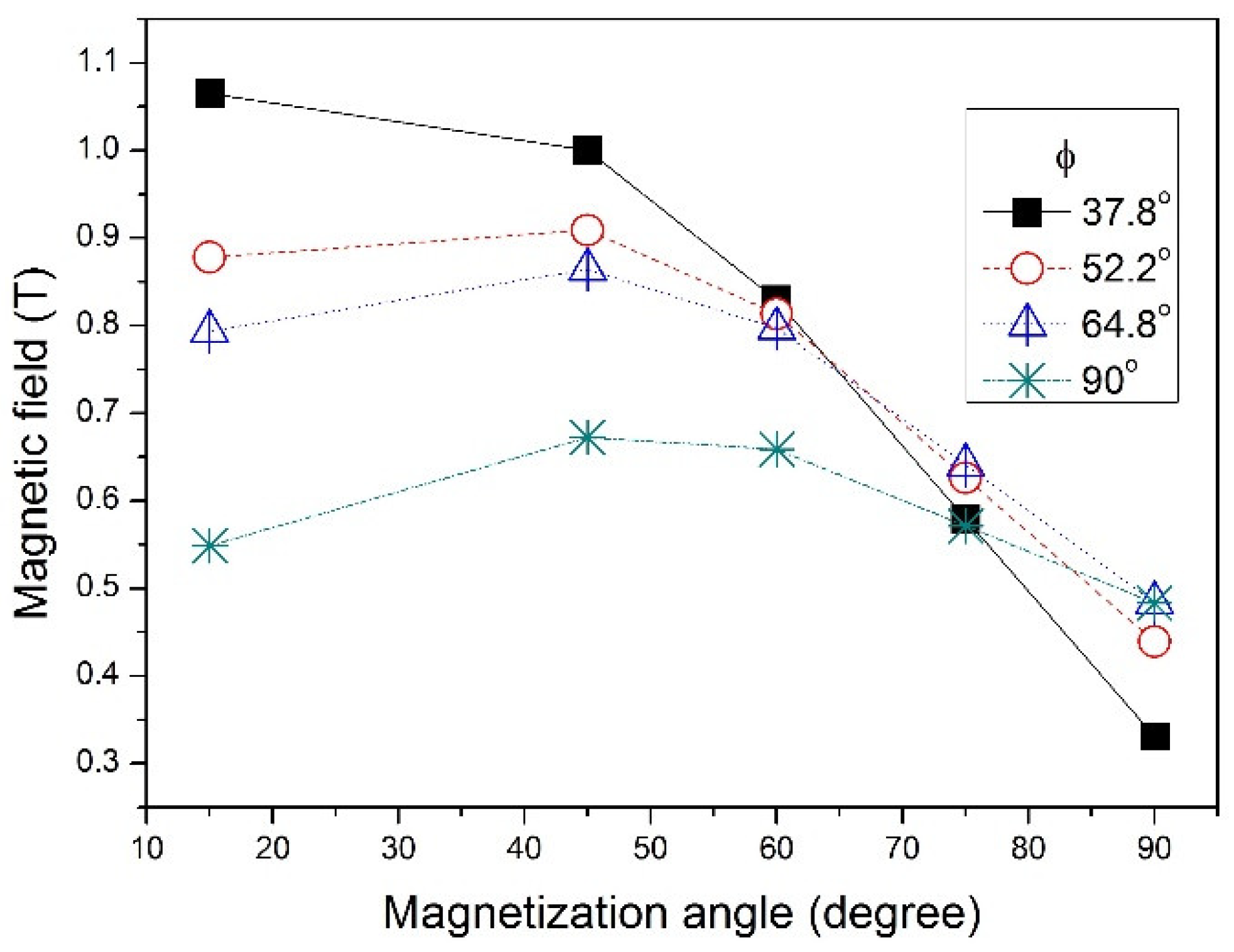

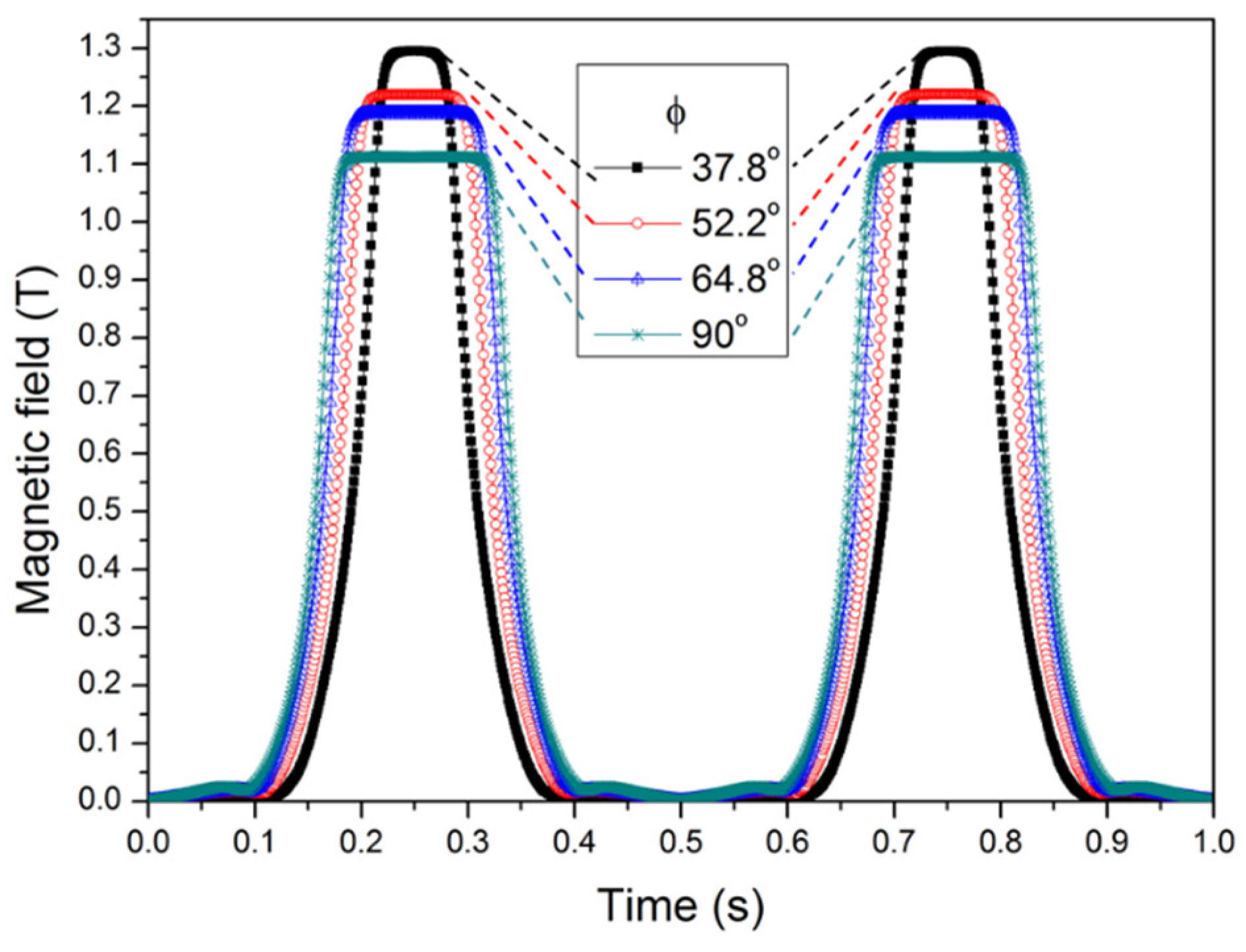

Figure 4.

Figure 4 plots out the magnetic field distribution in the middle of the gap as function of rotation angles around the circumference (the white dash line in

Figure 2) with four different ϕ angles at 37.8°, 52.2°, 64.8° and 90° at θ = 45°. If the rotation speed is 1 Hz, the horizontal axis of

Figure 4 rotates 360 degrees in 1 s.

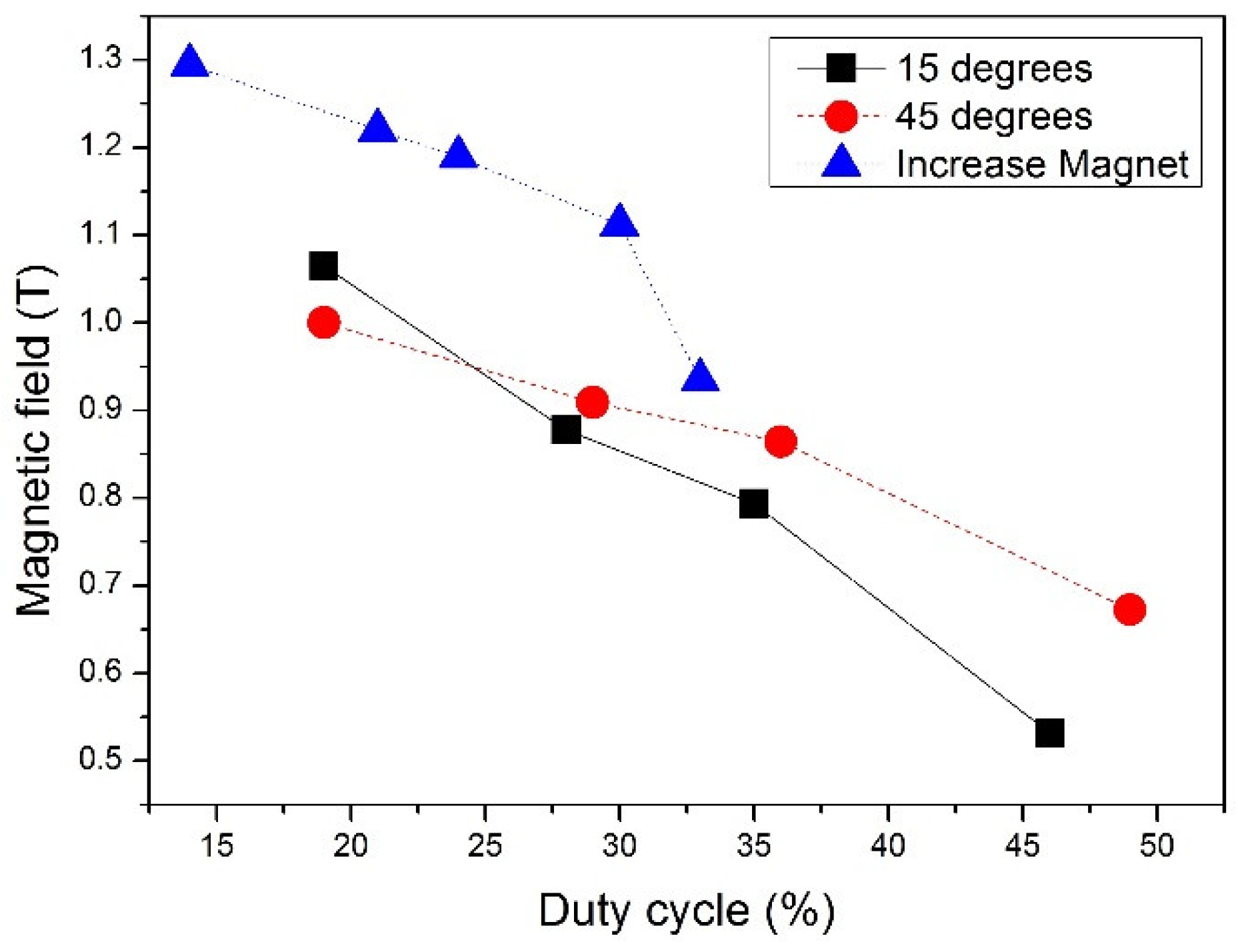

Figure 5 shows a summary of maximum magnetic fields as functions of θ with the fixed amount of Nd-Fe-B. The result indicates that for the magnet design with larger pole face angles, to achieve a higher magnetic field, smaller magnetization angles are needed. However, with the fixed amount of Nd-Fe-B material, only when the duty cycle is smaller than 20%, the maximum magnetic field can be larger than 1 T. The magnetic field decrease significantly as the duty cycle approaches 50% (see

Table 1). In order to increase the magnetic field as high as possible, more amount of Nd-Fe-B is added with a sacrifice of the steel material as the schematic shown in

Figure 6 and the corresponding magnetic field result is shown in

Figure 7. Although the magnetic field in

Figure 7 is stronger than the one in

Figure 4 owing to the addition of 29% and more Nd-Fe-B materials, the maximum magnetic field decreases significantly as the duty cycle of magnetization increases.

Figure 8 is a summary of the calculation result of maximum magnetic field as function of the duration of magnetic duty cycles. In order to achieve the best 50% of magnetic duty cycle to match the best thermo-hydraulic period, the maximum magnetic field is only 0.67 T, which gives rise to a serious reduction of the magnetic cooling capability.

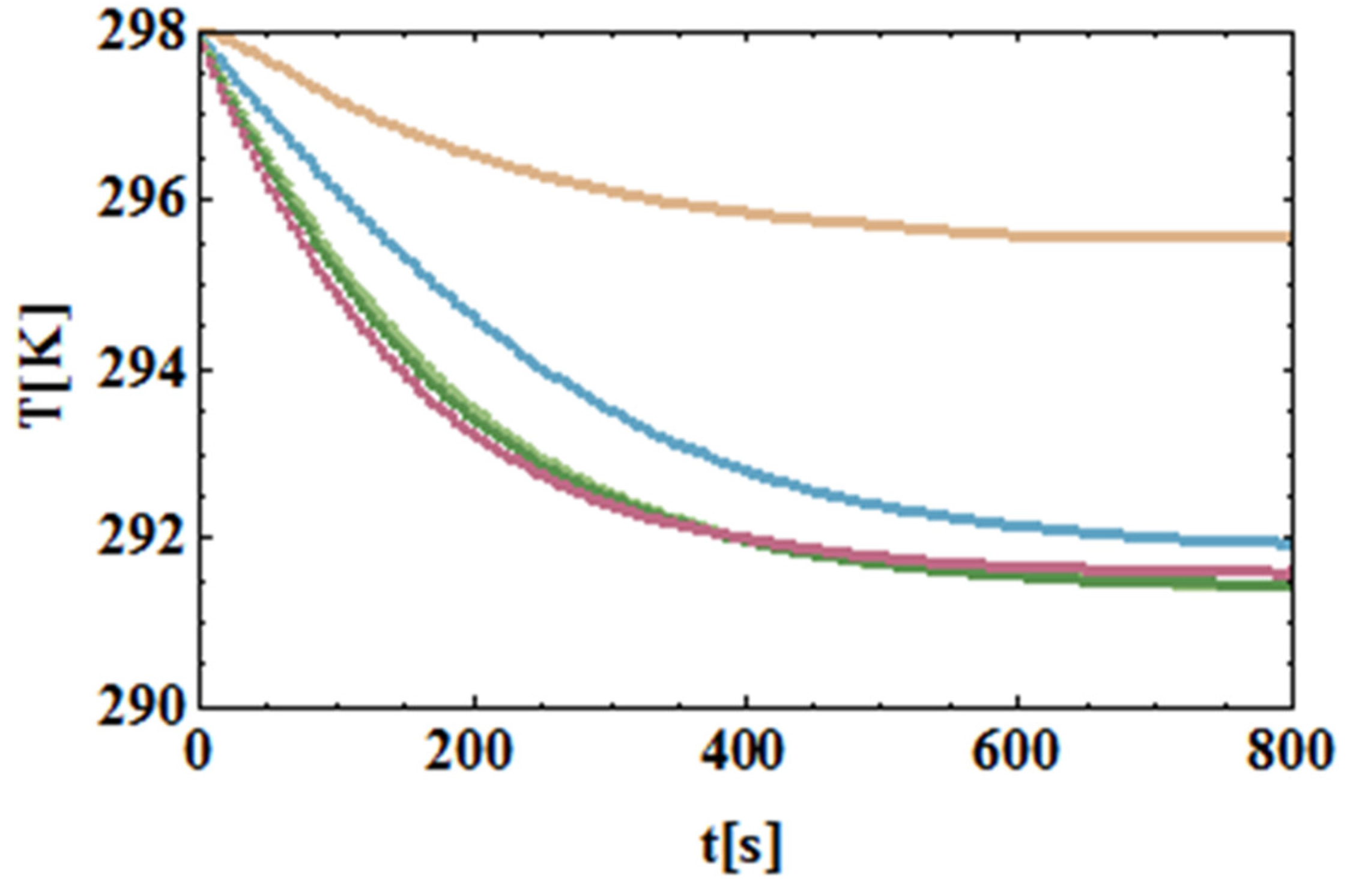

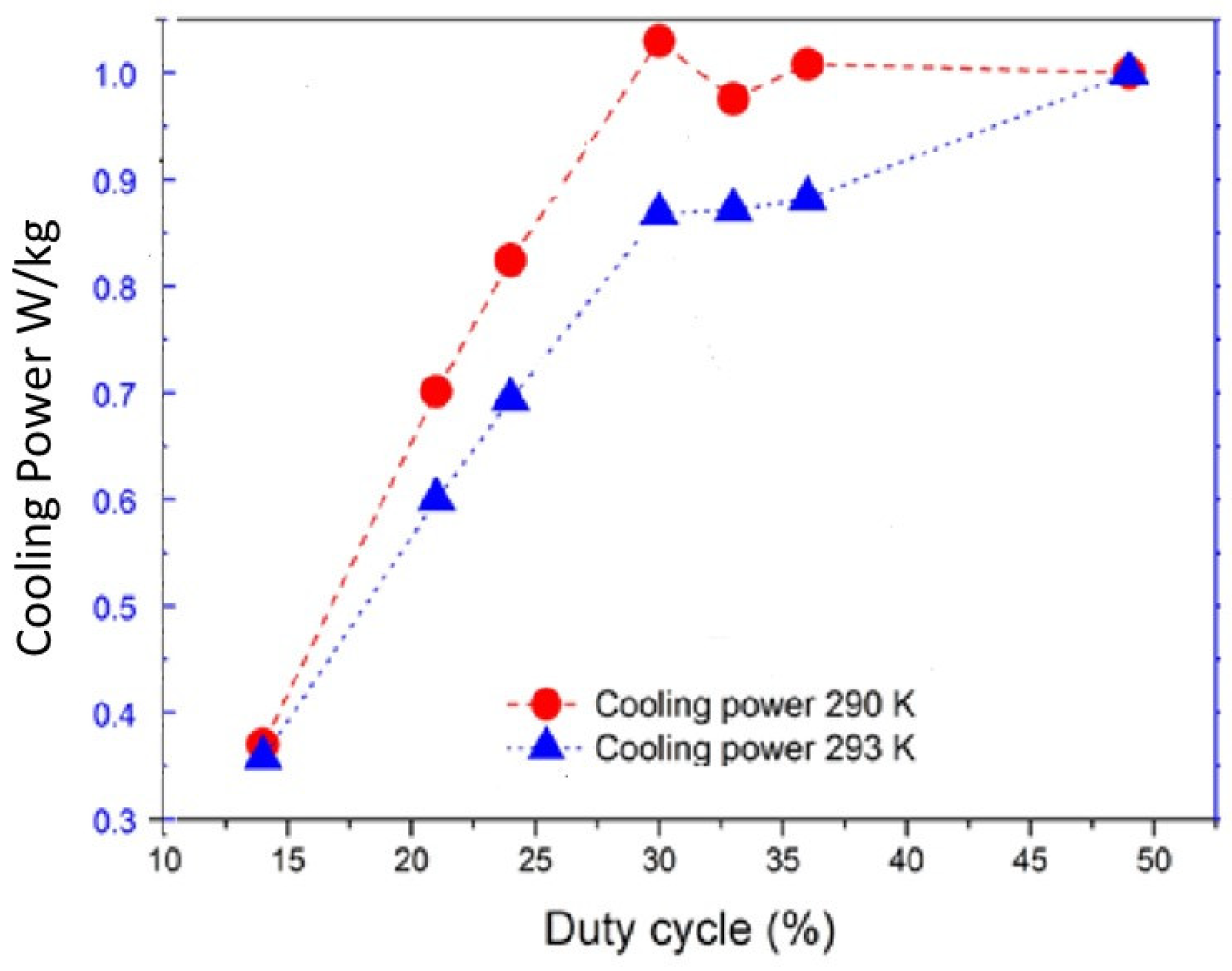

By taking the highest magnetic field in each duty cycle as the input to do the thermo-hydraulic calculation,

Figure 9 shows the average temperature at cold side as the time goes under different duty cycles of magnetization and demagnetization. It seems that the temperature at cold side decreases faster when the duty cycle is around 21%-36%. The cooling power obtained as functions of duty cycles is shown in

Figure 10. In this thermo-hydraulic calculation, two cases with different temperatures (290 K and 293 K) at cooling side (

Tc in

Figure 3b) are performed. In both cases, the initial system temperatures and the temperatures at the hot side (T

H in

Figure 3b) are kept at 298 K. In general, the cooling power increases as the temperature at cooling side decreases. By select the highest cooling power and lower magnetic duty cycle with less magnetic materials needed, the best duty cycle is about 49% when the temperature at cold side is at 293 K with the temperature span of 5 K, while the best duty cycle is around 30% for the case of

Tc=290 K with temperature span of 8 K. The lower duty cycle can reduce significantly the amount of magnetic materials (NdFeB and Gd) to cutdown the cost, while keep the cooling power still high.

5. Conclusions

A rotary cylindrical magnet was designed for magnetic refrigerator. For the rotary type magnetic cooling system, the best duty cycle of this magnet should be 50% if the magnetic field can be kept at high magnetic field at higher duty cycles. However, the calculation shows a serious reduction of the magnetic field strength at higher duty cycles. The optimized duty cycle of the cylindrical magnet design, which can reduce the amount of permanent magnet AMR materials, is around 30% for the temperature span of 8 K between hot and cold ends of a rotary type magnetic cooling system after considering a thermohydraulic calculation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CH Lee.; methodology, KC Leou.; software, PH Cheng and CM Hsieh.; validation, YC Su, CH Lee and KC Leou; formal analysis; investigation, KC Leou, CH Lee and YC Su.; resources, KC Leou; data curation, PH Cheng and CM Hsieh.; writing—original draft preparation, PH Cheng and CM Hsieh; writing—review and editing, CH Lee; supervision, KC Leou, CH Lee and YC Su; funding acquisition, CH Lee, KC Leou and YC Su. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan under the contract number of NSC102-ET-E007-004-ET. Th APC was supported by the Professor CH Lee of National Tsing Hua University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Professor CC Chien initiated this magnetic refrigerator project and part of financial support from Delta company (Taiwan) are acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bjork, R.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Smith, A.; Pryds, N. Review and comparison of magnet designs for magnetic refrigeration. Int. J. Refrig 2010, 33, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmer, A.; Al-Amayreh, M.; Mostafa, A.O.; Al-Dabbas, M.; Rezk, H. Magnetic Refrigeration Design Technologies: State of the Art and General Perspectives. energies 2021, 14, 4662–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocanegra, J.A.; Scarpa, F.; Fanghella, P.; Marchitto, A.; Tagliafco, L.A. Optimization and development of a new rotary magnetic refrigerator. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.G.; Yu, H.Y.; Zhong, X.C.; Zeng, D.C.; Liu, Z.W. Design and Performance Study of the Active Magnetic Refrigerator for Room-Temperature Application. Int. J. Refrig. 2009, 32, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.F.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, B.; Meng, X.Z.; Chen, Z. Review on research of room temperature magnetic refrigeration. Int. J. Refrig 2003, 26, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.M.; Su, Y.C.; Lee, C.H.; Cheng, P.H.; Leou, K.C. Modeling of graded active magnetic regenerator for room-temperature, energy-efficient refrigeration. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 4002904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayas, A.O.; Akça, G.O.; Akyol, M.; Ekicibil, A. Magnetic refrigeration: Current progress in magnetocaloric properties of perovskite manganite materials. Mater. Today Comm. 2023, 35, 105988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Liu, M.; Egolf, P.W.; Kitanovski, A. A review of magnetic refrigerator and heat pump prototypes built before the year 2010. Int. J. Refrig 2010, 33, 1029–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, C.R.H.; Engelbrecht, K.; Bjork, R.; Eriksen, D.; Smith, A.; Pryds, N. Design concepts for a continuously rotating active magnetic regenerator “ International Conference on Magnetic Refrigeration at Room Temperature pp. 1–7, 23-28 August 2010.

- Xia, D.; Xia, L. A novel permanent magnet system for magnetic refrigerator and its magnetic field analysis. International Conference on Electrical and Control Engineering, pp. 4928–4931, 2010.

- Bjork, R.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Smith, A.; Christensen, D.V.; Pryds, N. An optimized magnet for magnetic refrigeration. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2010, 322, 3324–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, T. Improvement of 100 W Class Room Temperature Magnetic Refrigerator. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Magnetic Refrigeration at Room Temperature, Portoroz, Slovenia, 11–13 April 2007; pp. 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán-López, J.F.; Palacios, E.; Velázquez, D.; Burriel, R. Design and optimization of a magnet for magnetocaloric refrigeration. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 126, 164502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, D.; Engelbrecht, K.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Bjørk, R.; Nielsen, K.K.; Insinga, A.R.; Pryds, N. Design and experimental tests of a rotary active magnetic regenerator prototype, Int. J. Refrig 2015, 58, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COMSOL, a multi-physics program. https//www.comsol.com/.

- Petersen, T.F.; Pryds, N.; Smith, A.; Hattel, J.; Schmidt, H.; Knudsen, H.-J. H. Two-dimensional mathematical model of a reciprocating room-temperature active magnetic regenerator, Int. J. Refrig 2008, 31, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).