Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. International Item Pool Revised for BIS/BAS Personality [BIS-BAS IPIP-R]

2.2.2. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [PANAS]

2.2.3. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale [DERS]

2.2.4. The Anger Rumination Scale [ARS]

2.2.5. The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II [AAQ-II]

2.2.6. Reactive-Proactive Aggression Questionnaire [RPQ]

2.2.7. Normative Deviance Scale [NDS]

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Data Analysis

2.3.2. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

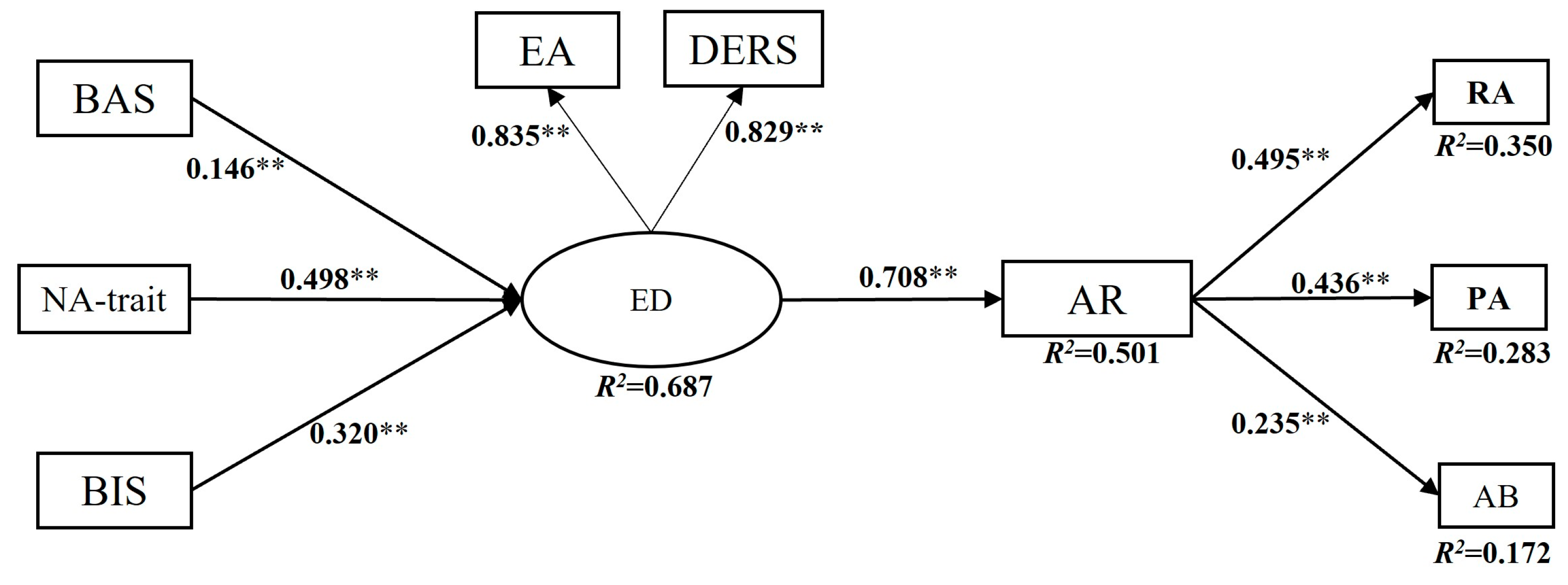

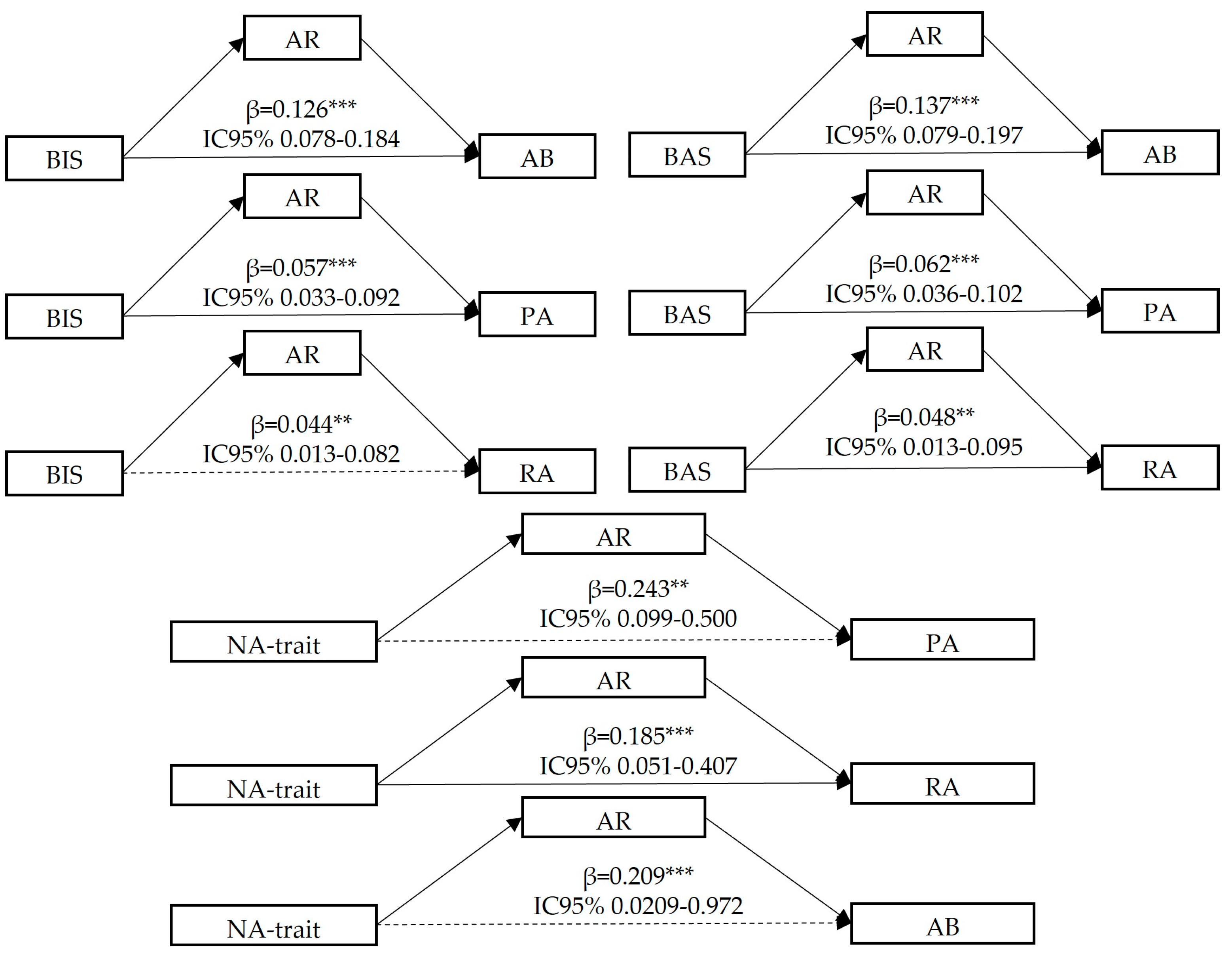

3.2. Structural Transdiagnostic Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krueger, R.F.; Markon, K.E.; Patrick, C.J.; Iacono, W.G. Externalizing Psychopathology in Adulthood: A Dimensional-Spectrum Conceptualization and Its Implications for DSM–V. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2005, 114(4), 537–550. [CrossRef]

- Wygant, D.B.; Sellbom, M.; Sleep, C.E.; Wall, T.D.; Applegate, K.C.; Krueger, R.F.; Patrick, C.J. Examining the DSM–5 Alternative Personality Disorder Model Operationalization of Antisocial Personality Disorder and Psychopathy in a Male Correctional Sample. Pers. Disord. Theory Res. Treat. 2016, 7(3), 229–239. [CrossRef]

- Penado, M.; Andreu, J.M.; Peña, E. Agresividad Reactiva, Proactiva y Mixta: Análisis de los Factores de Riesgo Individual. Anu. Psicol. Jurídica 2014, 24, 37–42. [CrossRef]

- Mansell, W.; Harvey, A.; Watkins, E.; Shafran, R. Conceptual Foundations of the Transdiagnostic Approach to CBT. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2009, 23(1), 6–19. [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.A. The Psychophysiological Basis of Introversion–Extraversion. Behav. Res. Ther. 1970, 8(3), 249–266. [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.A.; McNaughton, N. The Neuropsychology of Anxiety; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2000.

- Mowlaie, M.; Abolghasemi, A.; Aghababaei, N. Pathological Narcissism, Brain Behavioral Systems and Tendency to Substance Abuse: The Mediating Role of Self-Control. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 88, 247–250. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.K.; Sellbom, M.; Phillips, T.R. Elucidating the Associations between Psychopathy, Gray’s Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory Constructs, and Externalizing Behavior. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2014, 71, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Purnamaningsih, E.H. Personality and Emotion Regulation Strategies. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2017, 10(1), 53–60. [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Conceptual and Empirical Foundations. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Gross, J.J., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 13–21.

- Wills, T.A.; Simons, J.S.; Sussman, S.; Knight, R. Emotional self-control and dysregulation: A dual-process analysis of pathways to externalizing/internalizing symptomatology and positive well-being in younger adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 163, S37-S45. [CrossRef]

- Verona, E.; Bresin, K. Aggression proneness: Transdiagnostic processes involving negative valence and cognitive systems. Int J Psychophysiol. 2015, 98(2), 321-329. [CrossRef]

- Modecki, E.M.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M. Emotion regulation, coping, and decision making: Three linked skills for preventing externalizing problems in adolescence. Child Dev. 2017, 88(2), 417-426. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press: New York, 1999.

- Wolgast, M.; Lundh, L.; Viborg, G. Experiential Avoidance as an Emotion Regulatory Function: An Empirical Analysis of Experiential Avoidance in Relation to Behavioral Avoidance, Cognitive Reappraisal, and Response Suppression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2013, 42(3), 224–232. [CrossRef]

- Shorey, R.C.; Elmquist, J.; Zucosky, H.; Febres, J.; Brasfield, H.; Stuart, G.L. Experiential Avoidance and Male Dating Violence Perpetration: An Initial Investigation. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2014, 3(2), 117–123. [CrossRef]

- Denson, T.F. The Multiple Systems Model of Angry Rumination. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 17(2), 103–123. [CrossRef]

- Sukhodolsky, D.G.; Golub, A.; Cromwell, E.N. Development and Validation of the Anger Rumination Scale. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2001, 31(5), 689–700. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Gao, L.; Zhao, F.; Xie, X.; Lei, L. Trait Anger and Aggression: A Moderated Mediation Model of Anger Rumination and Moral Disengagement. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2018, 125, 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Martino, F.; Caselli, G.; Berardi, D.; Fiore, F.; Marino, E.; Menchetti, M.; Sassaroli, S. Anger Rumination and Aggressive Behaviour in Borderline Personality Disorder. Pers. Ment. Health 2015, 9(4), 277–287. [CrossRef]

- Guerra, R.C.; White, B.A. Psychopathy and Functions of Aggression in Emerging Adulthood: Moderation by Anger Rumination and Gender. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2017, 39(1), 35–45. [CrossRef]

- du Pont, A.; Rhee, S.H.; Corley, R.P.; Hewitt, J.K.; Friedman, N.P. Rumination and Psychopathology: Are Anger and Depressive Rumination Differentially Associated with Internalizing and Externalizing Psychopathology? Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 6(1), 18–31. [CrossRef]

- Shankman, S.A.; Gorka, S.M. Psychopathology Research in the RDoC Era: Unanswered Questions and the Importance of the Psychophysiological Unit of Analysis. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2015, 98(2 Pt 2), 330–337. [CrossRef]

- Hundt, N.E.; Brown, L.H.; Kimbrel, N.A.; Walsh, M.A.; Nelson-Gray, R.; Kwapil, T.R. Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory Predicts Positive and Negative Affect in Daily Life. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2013, 54(3), 350–354. [CrossRef]

- Pederson, C.A.; Fite, P.J.; Bortolato, M. The Role of Functions of Aggression in Associations between Behavioral Inhibition and Activation and Mental Health Outcomes. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2018, 27(8), 811–830. [CrossRef]

- Merchán-Clavellino, A.; Alameda-Bailén, J.R.; Zayas-García, A.; Guil, R. Mediating Effect of Trait Emotional Intelligence between the Behavioral Activation System (BAS)/Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) and Positive and Negative Affect. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 424. [CrossRef]

- Donahue, J.J.; Goranson, A.C.; McClure, K.S.; Van Male, L.M. Emotion Dysregulation, Negative Affect, and Aggression: A Moderated, Multiple Mediator Analysis. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2014, 70, 23–28. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R. A Broad-Bandwidth, Public Domain, Personality Inventory Measuring the Lower Level Facets of Several Five-Factor Models. In Personality Psychology in Europe; Mervielde, I., Deary, I., De Fruyt, F., Ostendorf, F., Eds.; Tilburg University Press: Tilburg, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 7, pp. 7–28. Retrieved from https://ipip.ori.org/A%20broad-bandwidth%20inventory.pdf.

- Martínez, M.V.; Zalazar-Jaime, M.F.; Pilatti, A.; Cupani, M. Adaptación del Cuestionario de Personalidad BIS BAS IPIP a una Muestra de Estudiantes Argentinos y su Relación con Patrones de Consumo de Alcohol. Av. Psicol. Latinoam. 2012, 30(2), 304–316. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/apl/v30n2/v30n2a07.pdf.

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.; Tellegen, A. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [CrossRef]

- Robles, R.; Páez, F. Estudio sobre la Traducción al Español y las Propiedades Psicométricas de las Escalas de Afecto Positivo y Negativo (PANAS). Salud Ment. 2003, 26(1), 69–75. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=58212608.

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26(1), 41–54. [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.; Robles, R.; González, C.; Andrade, P. Propiedades Psicométricas de la Escala “Dificultades en la Regulación Emocional” en Español (DERS-E) para Adolescentes Mexicanos. Salud Ment. 2012, 35(6), 521–526. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/sm/v35n6/v35n6a10.pdf.

- Ortega-Andrade, N.; Alcázar-Olán, R.; Matías, O.M.; Rivera-Guerrero, A.; Domínguez-Espinosa, A. Anger Rumination Scale: Validation in Mexico. Span. J. Psychol. 2017, 20(e1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary Psychometric Properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A Revised Measure of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42(4), 676–688. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, F.J.; Suárez-Falcón, J.C.; Cárdenas-Sierra, S.; Durán, Y.; Guerrero, K.; Riaño-Hernández, D. Psychometric Properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II in Colombia. Psychol. Rec. 2016, 66(3), 429–437. [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Dodge, H.; Loeber, R.; Gatzke-Kopp, L.; Lynam, D.; Reynolds, C.; Liu, J. The Reactive-Proactive Aggression Questionnaire: Differential Correlates of Reactive and Proactive Aggression in Adolescent Boys. Aggress. Behav. 2006, 32(2), 159–171. [CrossRef]

- Andreu, J.; Peña, M.; Ramírez, J. Cuestionario de Agresión Reactiva y Proactiva: Un Instrumento de Medida de la Agresión en Adolescentes. Rev. Psicopatol. Psicol. Clín. 2009, 14(1), 37–49. Retrieved from http://www.aepcp.net/arc/(4)_2009(1)_Andreu_Pena_Ramirez.pdf.

- Vazsonyi, A.T.; Pickering, L.E.; Junger, M.; Hessing, D. An Empirical Test of a General Theory of Crime: A Four-Nation Comparative Study of Self-Control and the Prediction of Deviance. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2001, 38(2), 91–131. [CrossRef]

- Frías, M.; Ramírez, J.M.; Soto, R.; Castell, I.; Corral, V. Repercusiones del Castigo Corporal en Niños: Un Estudio con Grupos de Alto Riesgo. In Asociación Mexicana de Psicología Social (AMEPSO), Eds.; La Psicología Social en México; Vol. VI, México: AMEPSO, 2000.

- Lei, M.; Lomax, R.G. The Effect of Varying Degrees of Nonnormality in Structural Equation Modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2005, 12(1), 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989.

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6(1), 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Satorra, A.; Bentler, P.M. Ensuring Positiveness of the Scaled Difference Chi-square Test Statistic. Psychometrika 2010, 75(2), 243–248. [CrossRef]

- Biesanz, J.C.; Falk, C.F.; Savalei, V. Assessing Mediational Models: Testing and Interval Estimation for Indirect Effects. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2010, 45(4), 661–701. [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48(2), 1–36. [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.11.1.0) [Computer software]. 2019. Retrieved from https://jasp-stats.org/.

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79(4), 373–374. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/268312.

- Santos, W.; Holanda, L.; Meneses, G.; Luengo, M.; Gomez-Fraguela, J. Conducta Antisocial: ¿Un Constructo Unidimensional o Multidimensional?. Av. Psicol. Latinoam. 2019, 37(1), 13–27. [CrossRef]

- Lobbestael, J.; Cima, M.; Arntz, A. The Relationship between Adult Reactive and Proactive Aggression, Hostile Interpretation Bias, and Antisocial Personality Disorder. J. Pers. Disord. 2013, 27(1), 53–66. [CrossRef]

- Whipp, A.M.; Korhonen, T.; Raevuori, A.; Heikkilä, K.; Pulkkinen, L.; Rose, R.J.; Vuoksimaa, E. Early Adolescent Aggression Predicts Antisocial Personality Disorder in Young Adults: A Population-Based Study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28(3), 341–350. [CrossRef]

- Taubitz, L.E.; Pedersen, W.S.; Larson, C.L. BAS Reward Responsiveness: A Unique Predictor of Positive Psychological Functioning. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 80, 107–112. [CrossRef]

- Leone, L.; Russo, P.M. Components of the Behavioral Activation System and Functional Impulsivity: A Test of Discriminant Hypotheses. J. Res. Pers. 2009, 43(6), 1101–1104. [CrossRef]

- Madole, J.W.; Johnson, S.L.; Carver, C.S. A Model of Aggressive Behavior: Early Adversity, Impulsivity, and Response Inhibition. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2019, Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Johnson, S.L. Impulsive Reactivity to Emotion and Vulnerability to Psychopathology. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73(9), 1067–1078. [CrossRef]

- Broerman, R.L.; Ross, S.R.; Corr, P.J. Throwing More Light on the Dark Side of Psychopathy: An Extension of Previous Findings for the Revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2014, 68, 165–169. [CrossRef]

- Schramm, A.T.; Venta, A.; Sharp, C. The Role of Experiential Avoidance in the Association between Borderline Features and Emotion Regulation in Adolescents. Pers. Disord. Theory Res. Treat. 2013, 4(2), 138–144. [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Penner, F.; Schramm, A.T.; Sharp, C. Experiential Avoidance in Adolescents with Borderline Personality Disorder: Comparison with a Non-BPD Psychiatric Group and Healthy Controls. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2019, 48(4), 622–632. [CrossRef]

- du Pont, A.; Rhee, S.H.; Corley, R.P.; Hewitt, J.K.; Friedman, N.P. Rumination and Executive Functions: Understanding Cognitive Vulnerability for Psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 256, 550–559. [CrossRef]

- Harmon, S.L.; Stephens, H.F.; Repper, K.K.; Driscoll, K.A.; Kistner, J.A. Children’s Rumination to Sadness and Anger: Implications for the Development of Depression and Aggression. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2017, 48(4), 622–632. [CrossRef]

- White, B.A.; Turner, K.A. Anger Rumination and Effortful Control: Mediation Effects on Reactive but not Proactive Aggression. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2014, 56, 186–189. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N.P.; Miyake, A. Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions: Individual Differences as a Window on Cognitive Structure. Cortex 2017, 86, 186–204. [CrossRef]

- van Vugt, M.K.; van der Velde, M. How Does Rumination Impact Cognition? A First Mechanistic Model. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2018, 10(1), 175–191. [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, E.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Brose, A.; Schmiedek, F.; Muthén, B. At the Frontiers of Modeling Intensive Longitudinal Data: Dynamic Structural Equation Models for the Affective Measurements from the COGITO Study. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2018, 53(6), 820–841. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.; Newman, J. RST and Psychopathy: Associations between Psychopathy and the Behavioral Activation and Inhibition Systems. In The Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory of Personality; Corr, P., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 398–414. [CrossRef]

- Toro, R.; García-García, J.; Zaldívar-Basurto, F. Antisocial Disorders in Adolescence and Youth, According to Structural, Emotional, and Cognitive Transdiagnostic Variables: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17(9), 3036. [CrossRef]

- Rosel, J.; Plewis, I. Longitudinal Data Analysis with Structural Equations. Methodology 2008, 4(1), 37–50. [CrossRef]

| Variable (total sample) |

Institutionalized (sample 1) | Students (sample 2) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age n = 351 M = 17.811 years, SD = 3.11, minimum 14 and maximum 25 years. |

n = 167 M = 19.16, SD = 3.09, minimum 14 y maximum 25 years |

n = 184 M = 16.58, SD = 2.59 minimum 14 y maximum 25 years |

|

Scholarship Without studies n = 3, 0.85% Elementary n = 32, 9.11% Middle n = 90, 25.64% High School n = 187, 53.27% College n = 39, 11.11% Total n = 351, 100% |

n = 3, 1.79% n = 32, 19.16% n = 87, 52.09% n = 44, 26.34% n = 1, 0.59% n = 167, 47.58% |

n = 0, 0% n = 0, 0% n = 3, 1.63% n = 143, 77.71% n = 38, 20.65% n = 184, 52.42% |

| Vble | M | SD | sk | k | Min | Max | ω (α) | T-tests* | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIS | 23.69 | 6.96 | 0.12 | -0.43 | 8 | 40 | .808 (.805) | -1.42 | 0.157 | -0.15 |

| BAS | 25.18 | 6.77 | -0.13 | -0.56 | 9 | 40 | .822 (.820) | -1.92 | 0.055 | -0.20 |

| NA-trait | 19.58 | 6.66 | 0.81 | 0.57 | 10 | 43 | .793 (.791) | -1.45 | 0.147 | -0.15 |

| DERS | 53.08 | 15.30 | 0.94 | 0.70 | 25 | 103 | .890 (.881) | -2.78 | 0.006 | -0.29 |

| AR | 36.50 | 11.34 | 0.92 | 0.68 | 19 | 74 | .907 (.906) | -3.17 | 0.002 | -0.33 |

| EA | 18.29 | 10.11 | 0.87 | -0.10 | 7 | 49 | .903 (.903) | -3.60 | < .001 | -0.38 |

| RA | 8.92 | 4.10 | 0.44 | 0.23 | 0 | 22 | .798 (.796) | -4.49 | < .001 | -0.48 |

| PA | 5.69 | 4.95 | 0.94 | 0.34 | 0 | 24 | .882 (.879) | -9.31 | < .001 | -0.99 |

| AB | 30.38 | 32.67 | 1.50 | 1.60 | 0 | 156 | .965 (.964) | -10.79 | < .001 | -1.15 |

| Model | χ² | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | IC95% RMSEA |

p close RMSEA |

SRMR | ΔS-Bχ² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag and AB | 23749* | 9 | 0.987 | 0.951 | 0.068 | 0.037-0.101 | 0.150 | 0.028 | - |

| Only AB | 22081* | 7 | 0.978 | 0.943 | 0.078 | 0.046-0.113 | 0.074 | 0.027 | 0.4539 |

| Only Ag | 23743* | 8 | 0.984 | 0.951 | 0.075 | 0.043-0.109 | 0.094 | 0.029 | 0.0685 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).