1. Introduction

In materials science, the study of new materials with functional properties is relevant. Polymers that have one or more functional properties that change under the influence of external factors are classified as «smart» materials or so-called intelligent. «Smart» materials do not require automatic control and monitoring. These materials are able to change their properties depending on any environmental conditions (temperature, pressure, humidity, light, etc.). Often, polymer composites with carbon materials have conductive properties due to which they effectively change their properties [

1,

2]. At the same time, it is noted that one of the functional features of conductive polymer composites is their ability to switch between insulating and conducting states as a result of changing their own resistance, depending on the temperature of the composite [

3,

4]. These composites are characterized by an increase in resistance with increasing temperature, especially near the melting point (T

m) of the polymer, a phenomenon known as the effect of the positive temperature coefficient of resistance (PTC) [

5,

6].

The optimal choice of the polymer matrix and the conductive dispersed additive allows achieving the desired mechanical, electrical and thermal properties, which in turn determine the scope of application of the composite, for example, the thermal interface in heat exchange equipment, electric heaters with adaptive heating modes for energy-efficient technologies, thermal insulation coatings, etc. [

7,

8]. Therefore, to obtain a composite with the specified characteristics, a certain concentration of the conductive component and a more detailed study of the interaction of the conductive phase with the dielectric (polymer) are required. Traditional methods of obtaining polymer composites, such as melt mixing, have limitations associated with their rheological properties, which makes it difficult to achieve the desired results. The addition of carbon nanomaterials to the polymer allows obtaining composites with new or improved properties. The content of CNTs in the polymer matrix increases: conductivity by several orders of magnitude or more; strength, elasticity, impact strength and durability from 5 to 30% [

8].

The objective of the review study is to determine the prospects for using various nanomaterials as additives to polymers to impart conductive properties necessary for creating functional composites with a self-regulating temperature effect. To achieve this objective, the following tasks were formulated:

- -

To study various polymers used as a basis for creating composites containing conductive nanomaterials;

- -

To study various types of dispersed fillers for polymers;

- -

To study polymer composites used as heating elements, including “smart” polymers with a self-regulating temperature effect;

- -

To analyze the possibility of using polymer heaters for various technological applications.

- -

To analyze possible aspects of using neural networks to obtain model parameters necessary for creating polymer composites.

2. Research of Polymers

2.1. Thermosets

Thermosets are obtained from the liquid phase with subsequent hardening [

9]. In this case, an organic solvent is used to form the liquid phase, further distribute dispersed particles in it, and mix this solvent with epoxy resin [

10]. Dispersion of the conductive filler occurs directly in the solvent with the formation of a stable dispersion [

11].

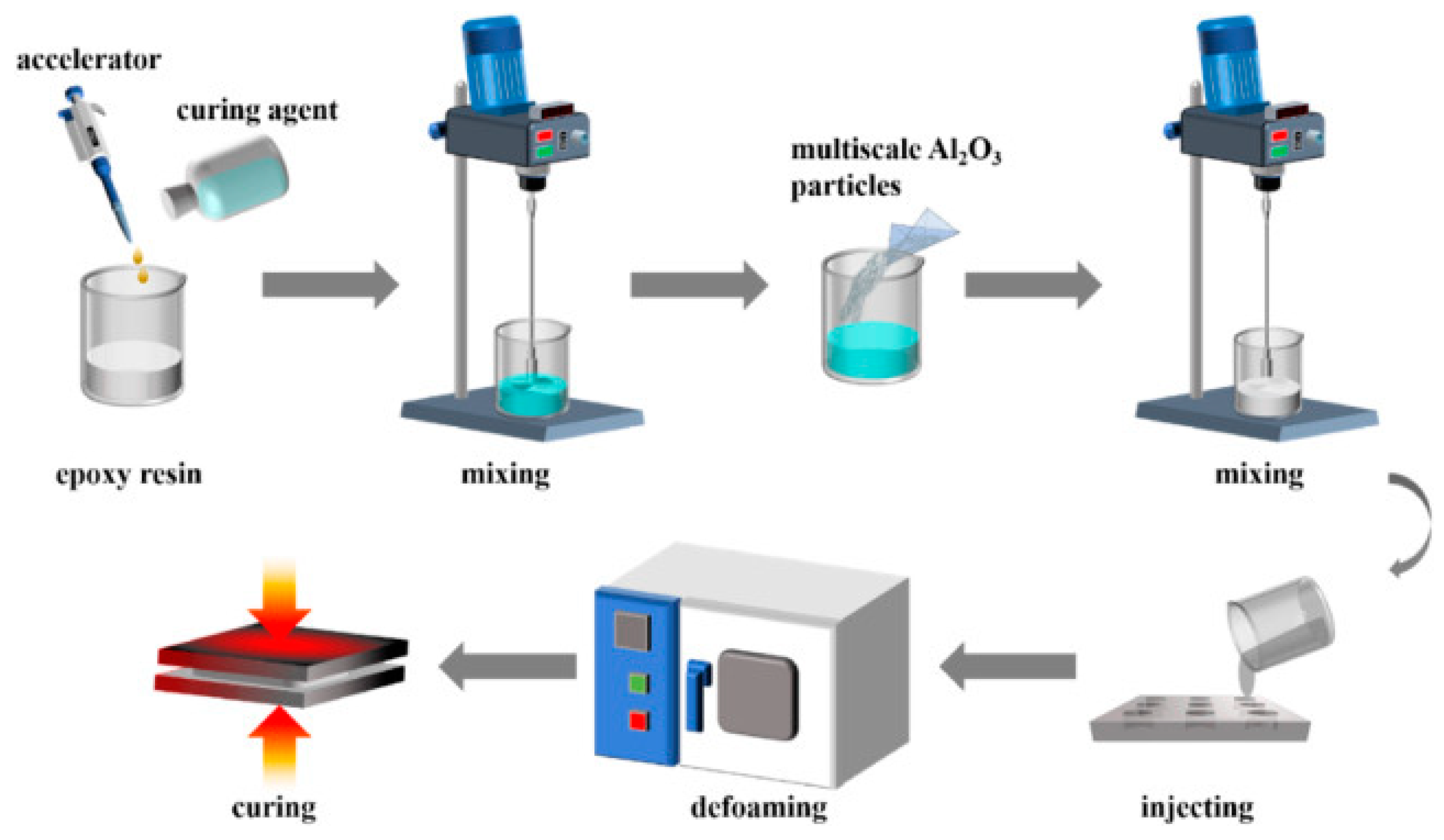

Figure 1 shows a diagram of the production of a composite based on epoxy resin with the addition of microsized Al

2O

3 particles [

12]

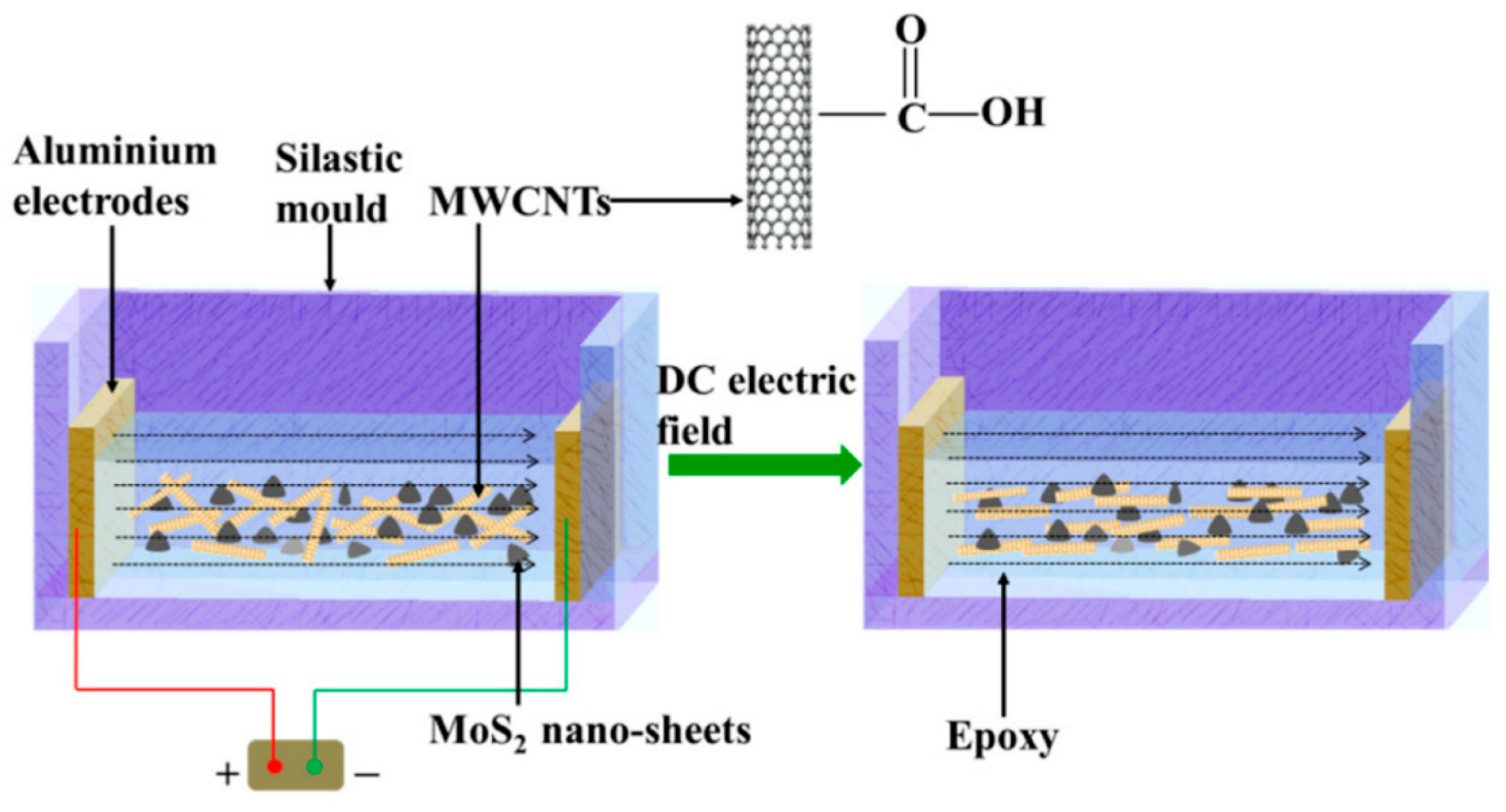

Composites manufactured using solution technology provide better dispersion of nanofillers in the polymer matrix and, consequently, a lower percolation threshold value, compared to composites obtained from the melt. This is explained by the fact that when manufacturing a composite using solution technology, intermediate solutions containing CNTs and the base are often subjected to ultrasound exposure together with an electric field, which makes the distribution of CNTs more uniform (

Figure 2) [

13].

There are two types of thermosetting plastics: epoxy [

14,

15] and polyester resins [

16]. Composites based on epoxy resin are usually hard and rigid and lack flexibility and elasticity. Direct electrical action was used to cure carbon fiber reinforced polymers (CFRP) [

17]. In particular, work [

17] showed that the energy consumption for curing is significantly reduced under optimal curing conditions and electrode placement. In [

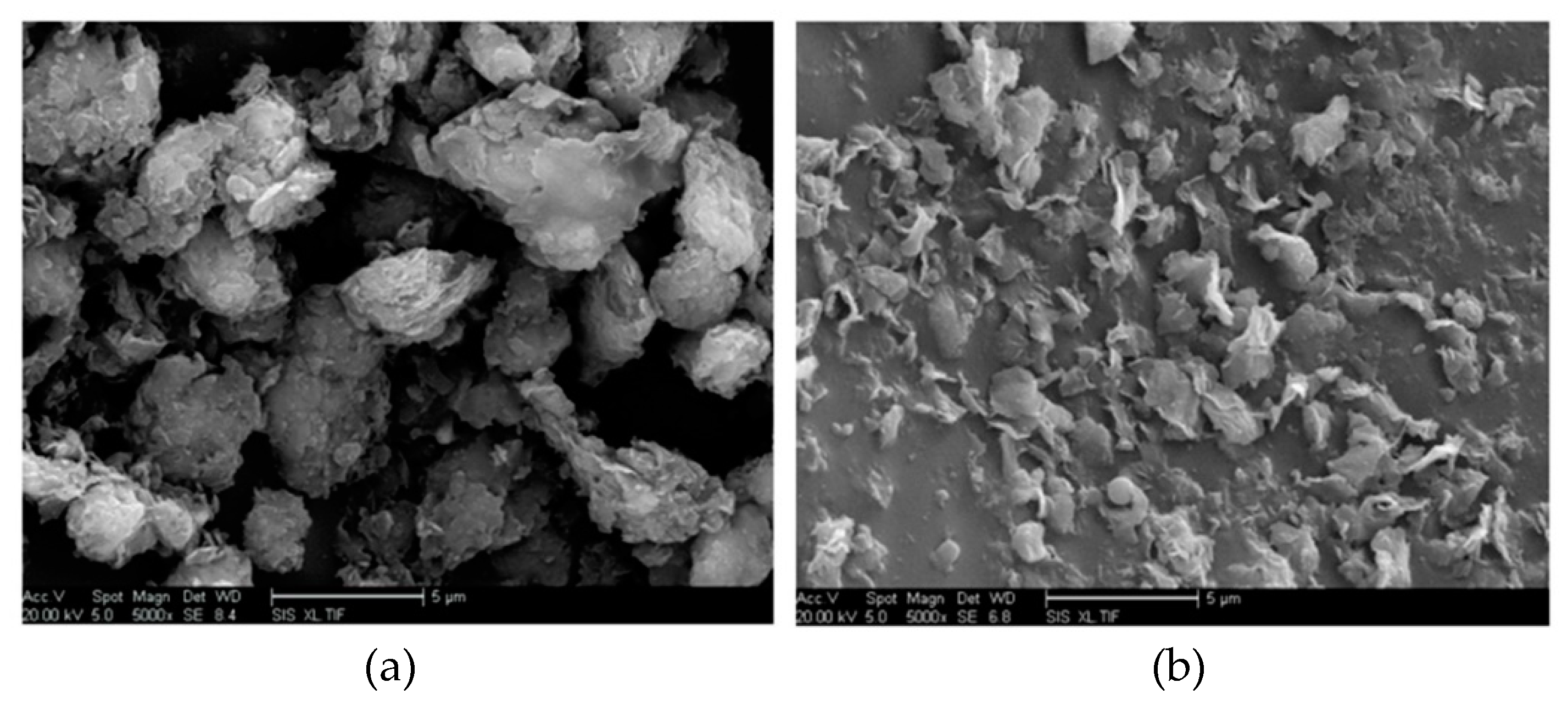

18], it was shown that MMT (nano-montmorillonoid) nanoparticles dispersed in the resin matrix retained their inherent configuration (Figure 3a).

Figure 3b demonstrates the layered structure of MMT nanoparticles [

18].

2.2. Thermoplastics

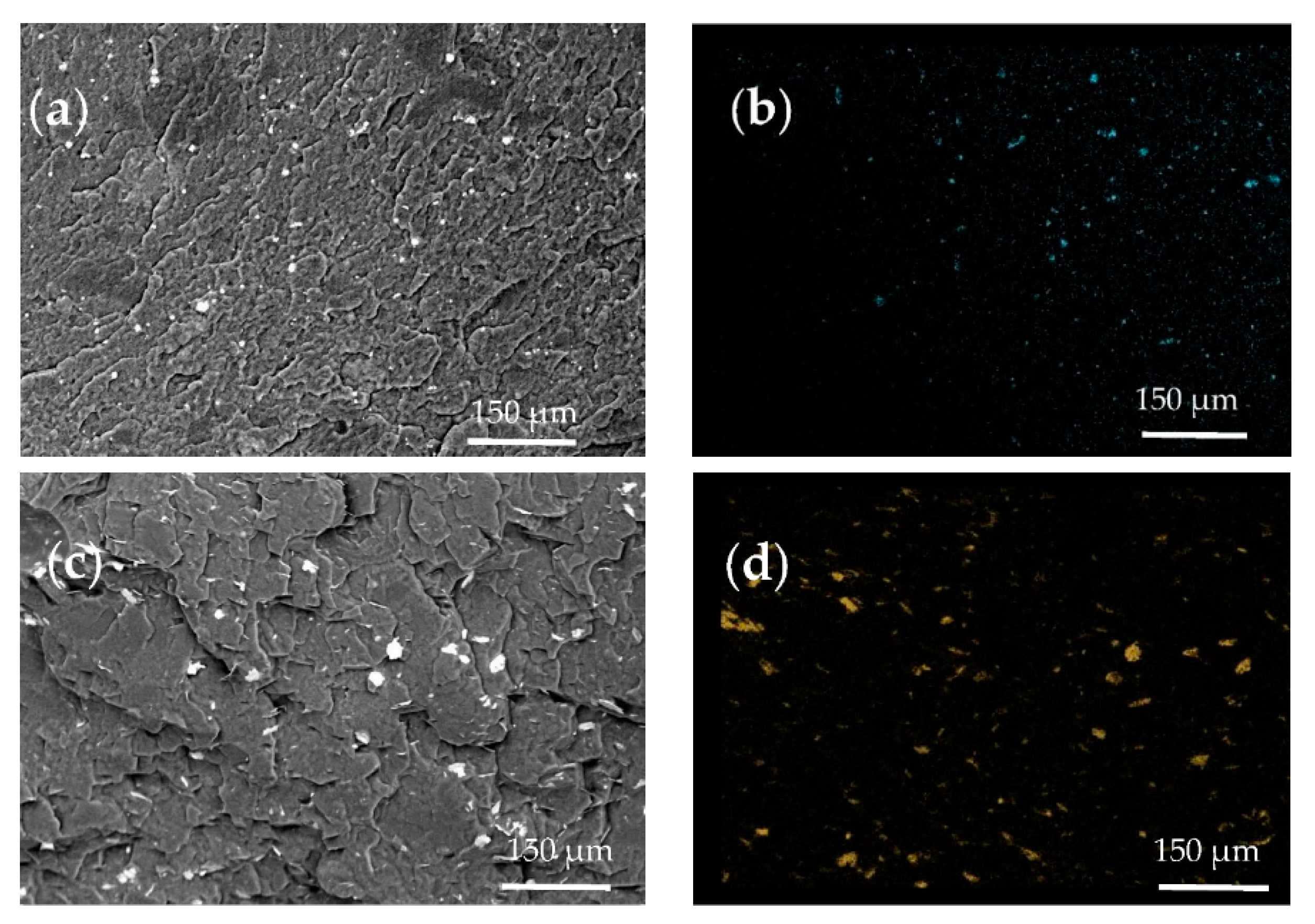

In [

19], composites with carbon black (CB) or hybrid filler (CB and graphite) and a linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE) matrix were investigated. LLDPE is a (co)polymer with low crystallinity but high structural regularity, which has been less studied for applications as positive temperature coefficient (PTC) heaters, but is of interest due to its higher flexibility compared to high-density polyethylene (HDPE). The structural and morphological characteristics of the LLDPE-based composite are presented in

Figure 4.

In [

20], electrical percolation by alternating current in a two-phase polyethylene/graphite composite immersed in an aqueous KCl solution (

Figure 5) with different contents of graphite microparticles was investigated.

Mixtures of different types of thermoplastics have become widespread, such as a mixture of polyethylene/polyoxymethylene (PE/POM), and iron-conducting reinforcing particles. Thermoplastics have certain advantages, but there are also disadvantages associated with the possible occurrence of cracks. The study of fatigue crack growth (FGG) in fiber-reinforced polymer composites is based on the Simple-Scaling method and the Hartmann-Schijwe crack growth equation, which is based on the relationship between the FCG rate and the driving force of the Schwalbe crack [

21].

2.3. Elastomers

Elastomers have high elasticity, flexibility and stretchability, which determine their use as a matrix for various types of sensors [

23]. In this regard, organosilicon elastomers are also promising materials [

24].

In the study [

25], thermally conductive and elastic polyurethane composites obtained by constructing a three-branched polymer network were developed. Polyurethane composites demonstrate ultra-high stretchability (2000%), low Young's modulus (640 kPa) and low thermal resistance (0.11 K cm2 W-1).

In the work [

26], the poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) matrix was reinforced with aluminum oxide particles with MWCNTs to improve thermal and electrical conductivity. The concentration of MWCNTs was increased to 10 wt. % for PDMS with a fixed amount of aluminum oxide of 200 and 300 wt. %, respectively. Since alumina particles help to disperse MWCNTs in the PDMS matrix, the thermal and electrical conductivity of the composites was increased with increasing alumina concentration.

3. Fillers

3.1. Metals

Metallic nanoparticles are widely used to improve the electrical properties of polymers [

27]. Cu dispersed powder is an alternative to Ag as a conductive nanomaterial [

28]. Metallic particles, particularly Ni and Au, can be used to enhance the performance of carbon black (CB). Ni-modified CB reduces the room temperature resistivity to a lower value than that of PTC composites obtained with unmodified CB [

29]. Metallic fillers combine well with carbon nanomaterials, such as CNTs (

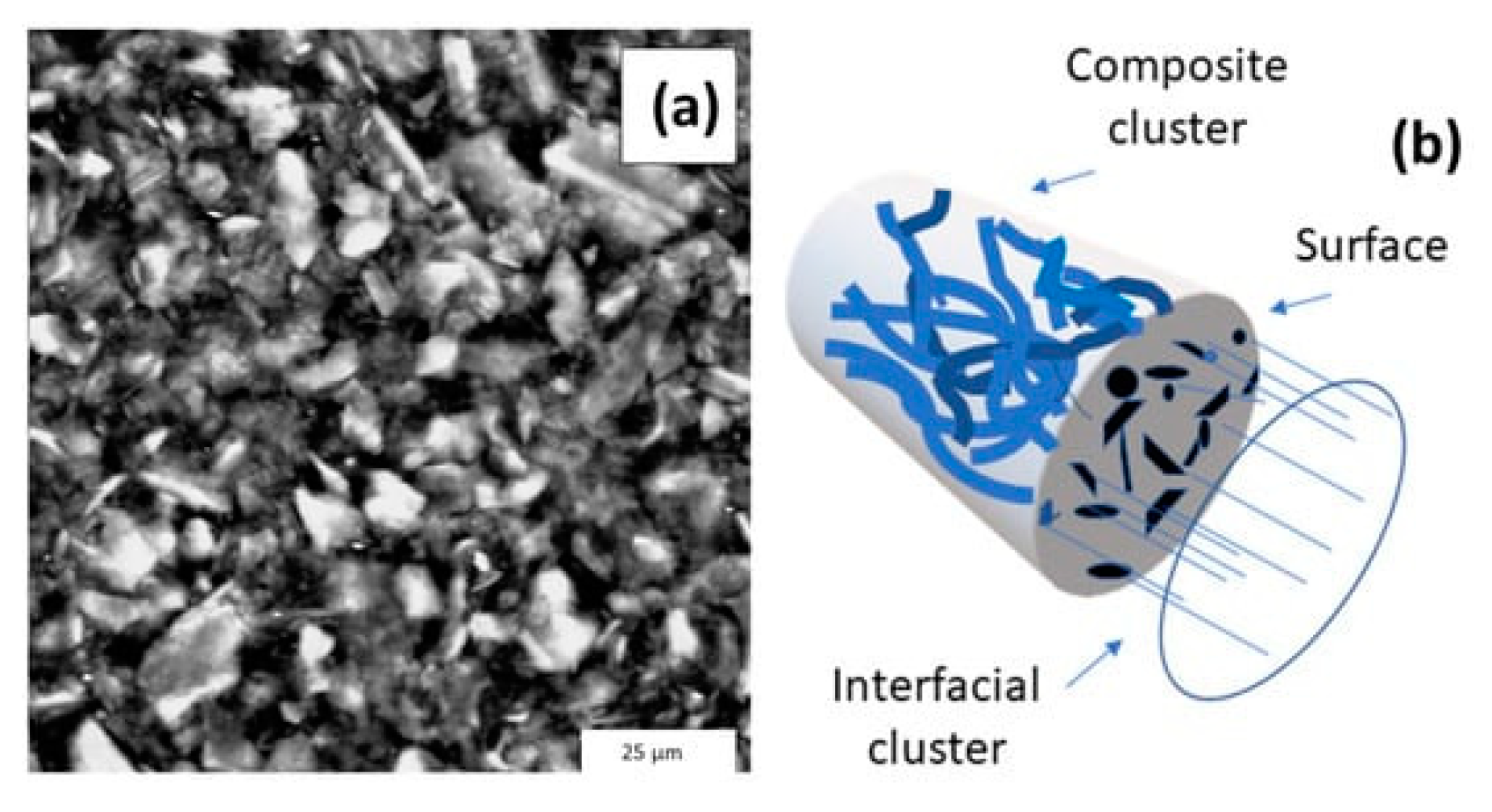

Figure 6) [

30].

Another variant of dispersed metal structures are iron particles, which can be used to create a conductive composite with functional properties [

31,

32]. The use of a composite consisting of PEDOT:PSS, PVA and NiMP is known [

33].

3.2. Carbon Dispersed Fillers

Carbon materials such as graphene and its derivatives [

37], carbon nanotubes [

35], fullerenes [

36], etc. are often used as nanosized dispersed additives for polymer composites [

34]. The use of carbon nanomaterials is associated with their morphology, which interacts best with various polymer matrices, such as multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). MWCNTs and CNTs are characterized by the best, compared to metals, optimal combination of morphological and physicochemical properties - optimal for a large class of polymers [

38]. Carbon nanomaterials are characterized by a variety of nanostructures, differing in the number and shape of graphene layers, the distance between the layers and the morphology of the outer layer. In this case, CNTs can be short and ultra-long [

39], and also have both metallic [

40] and semiconductor properties, and in some cases combine metallic and semiconductor properties. The range of electrical and thermal characteristics of nanocomposites reinforced with CNTs is wide [

41]. For example, CNTs are used as a reinforcing additive in rubber production technologies [

42], and are also widely used as additives in the production of heat-conducting materials [

43]. The structure of CNTs is determined by cylindrical and geometric parameters. In combination with excellent dispersibility and optimal specific surface area, CNTs allow for the efficient creation of both anisotropic and isotropic thermal and electrical conductivity in nanocomposites [

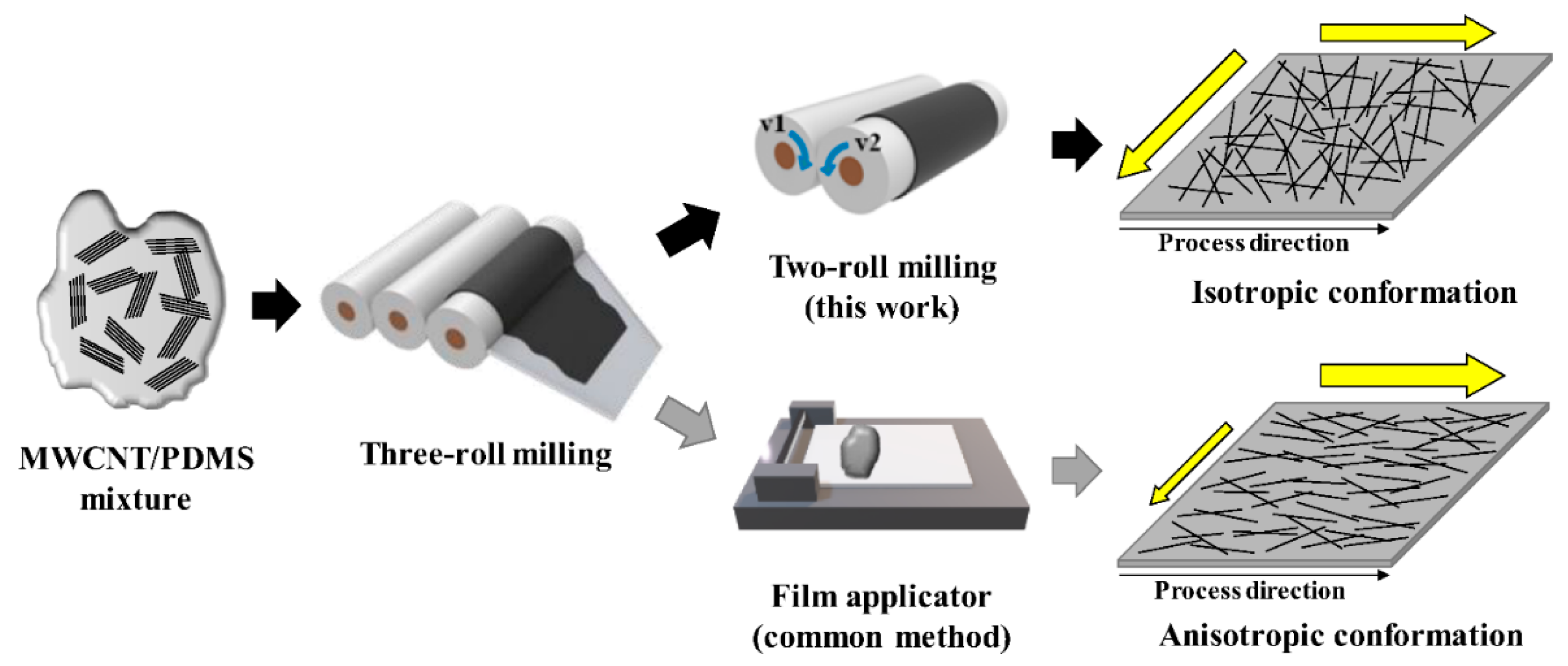

43]. It should be noted that for the production of PDMS films with a high mass concentration of MWCNTs, the two-roll method of obtaining a composite with increased PDMS viscosity is effective [

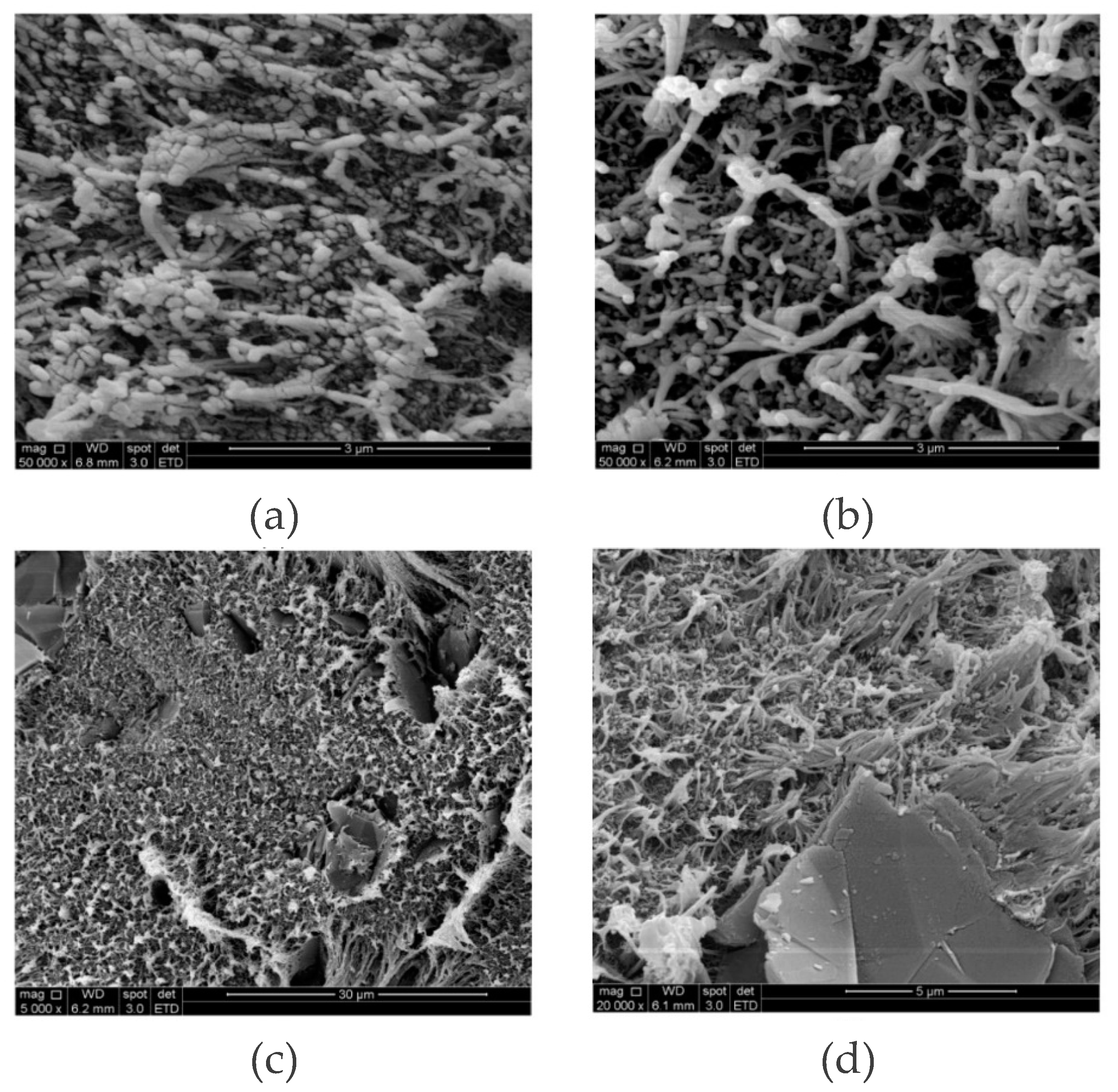

44]. In addition, the composite film formed by the twin-roll process has a relatively planar isotropic alignment of MWCNTs (

Figure 7) [

44].

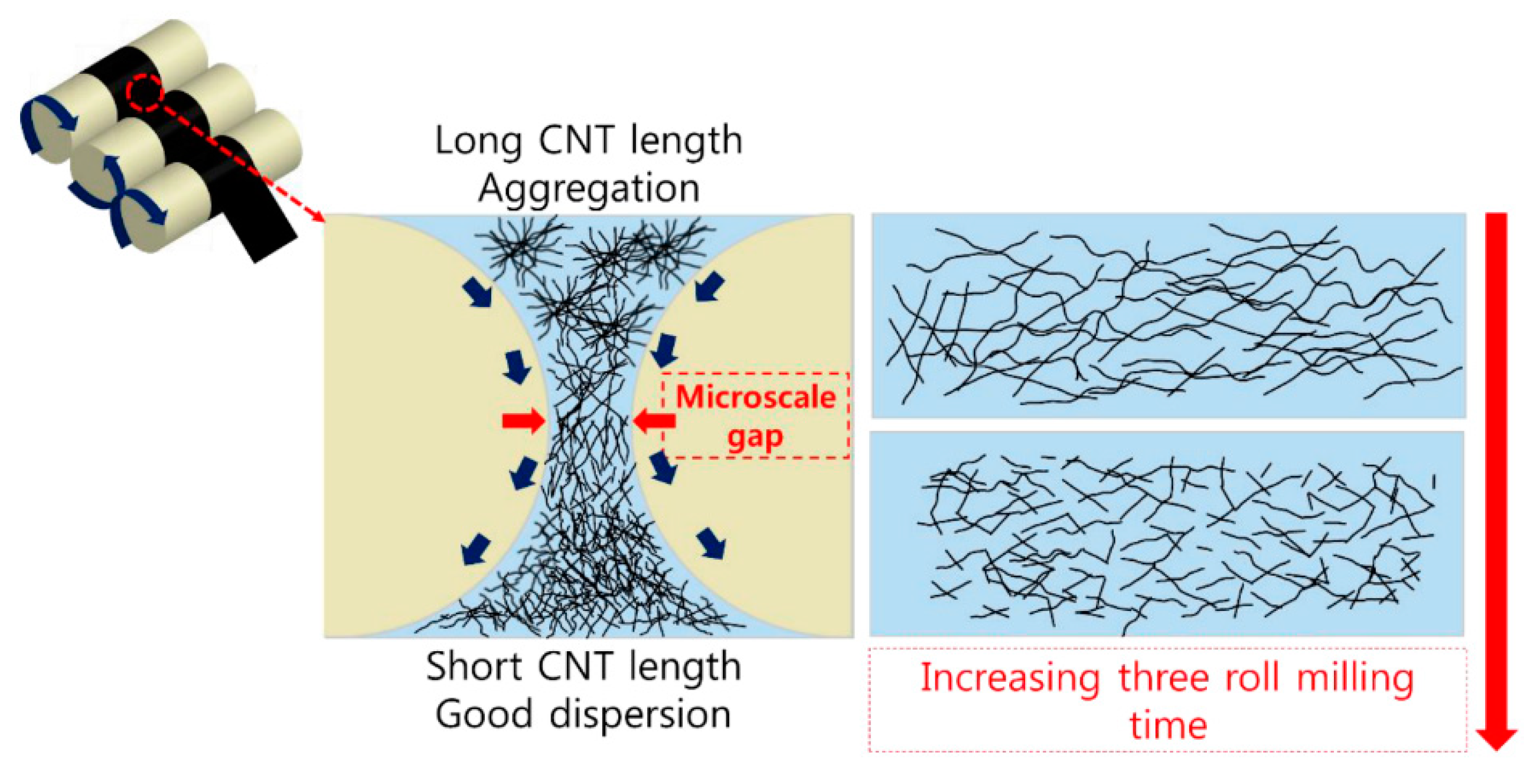

In [

45], the effect of three-roll milling time (

Figure 8) on the CNT length and electrical properties of a CNT/polydimethylsiloxane composite film containing 10 wt.% CNT was investigated.

Figure 8 schematically shows the dispersion mechanism using a three-roll mill. The work notes that during milling, the CNT length decreases from 10 to 1–4 μm due to mechanical shear forces. At the same time, the electrical conductivity increases after 1.5 min of milling due to better dispersion of CNTs, but decreases with increasing milling time due to a decrease in the CNT length.

4. Composites

4.1. Self-Assembly of Conductive Structures in Polymer Composite

In [

46], an electrostatic self-assembly method was used to obtain the composite, which works with negatively charged MWCNT-COOH and positively charged polydimethyldiallylammonium chloride (PDDA) solution, filling the structure with polyethylene glycol PCM (PEG) and incorporating (magnesium hydrate) Mg(OH)2. The thermal conductivity of the obtained composites was significantly improved from 0.25 W/m K to 1.183 W/m K, while maintaining the phase transition enthalpy of 135.1 J/g.

[

47] utilized the electrostatic self-assembly between negatively charged graphene-silver (GNs-Ag) and positively charged cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) functionalized fMWCNTs to construct a unique three-dimensional (3D) structure in PVDF. The AgNPs are uniformly loaded onto the graphene nanosheets, and the well-dispersed fMWCNTs act as bridges connecting adjacent AgNPs and GNs to form a more efficient heat transfer path, thereby obtaining polymer nanocomposites with higher thermal conductivity (λ). The thermal conductivity of GNs-Ag/fMWCNTs/PVDF composites reaches 9.24 W/(m∙K) with 25 wt% GNs-Ag/fMWCNTs fillers, which is 3495% higher than that of pure PVDF.

Through the host template effect, oxidized cellulose nanocrystal (OCNC), boron nitride nanosheet (BNNS) and OCNC self-assemble to form an artificial layered nacreous structure, where OCNC combined with epoxy adhesive agent (AA) serves as a solution to form a rigid and dense structure. The obtained BNNS-OCNC-AA composite at a relatively low BNNS loading of 11.6 vol% exhibits a high thermal conductivity of 10.9 W/mK as well as an excellent tensile strength of 197.3 MPa, which stand out compared to other composites prepared by various currently established methods at higher filler loadings (13.4 ~ 95 vol%) [

48].

In [

49], π–π bonds between CNTs and graphene oxide (GO) are used to disperse conductive but non-polar CNTs with amphiphilic GO sheets to form a stable aqueous colloidal solution. Then, water-dispersible latex-polystyrene microspheres are added to enable the self-assembly processes of anchoring CNTs on GO and wrapping the GO-stabilized CNT microspheres to form a 3D hierarchical multi-scale structure.

4.2. Composites with Positive Temperature Coefficient of Resistance

The technology of obtaining polymer composites for heaters is based on the technology of dispersed fillers distribution in the structure of the polymer matrix [

50].

The use of polymer composites as heating elements opens up new perspectives in the field of energy-efficient technologies both in housing and industry, as well as in motor vehicles [

50]. This is due to the optimal choice of polymer matrix and filler, as well as the precise selection of temperature regimes [

51]. It should be noted that polymer composites can work due to Joule heat release, i.e. heating does not depend on the surrounding conditions, and with adaptive heat release, i.e. have the effect of temperature self-regulation [

52,

53]. Polymer composites with the effect of temperature self-regulation are referred to the class of "smart" materials or so-called intelligent materials [

54]. The effect of temperature self-regulation is realized due to the positive temperature coefficient of resistance (PTCR). In this case, the resistance can increase sharply with increasing temperature, which follows from the interconnection of the composite with the external environment. Often, this is due to the phase transition of the polymer (melting or glass transition). Composites based on high-pressure polyethylene (HDPE) reinforced with dispersed carbon black (CB) are characterized by energy-consuming extrusion, complex mixing at high concentrations of CB more than 25 wt.% to obtain electrical resistance of about 10 Ohm; low thermal stability as a result of easy oxidation of amorphous CB particles at elevated temperatures [

55].

It is reported in [

56] that the presence of wax and CB and CB/Zn filler resulted in improved electrical conductivity. Thermal expansion in the composites did not affect the high PTCR value. The presence of a small amount of paraffin wax significantly increased the PTCR coefficients of the LDPE-based conductive composite. At the same time, the crosslinking induced by γ-radiation provides thermomechanical stability of amorphous regions in HDPE, which is necessary to obtain high PTCR intensity.

In [

57], aspects of obtaining two-step positive temperature coefficient (PTCR) in filled immiscible semi-crystalline polymer blends are presented. In [

58], high density polyethylene (HDPE)/polypropylene (PP) based composites filled with carbon black (CB) and a blend of CB and carbon fiber (CF). It was found that CB first accumulated in the PE phase and then started to localize at the PE/PP interface when the CB content in the PR phase approached the saturation limit.

In [

59], the relationship between the resistance and dynamic rheological properties of CB-filled high-density polyethylene (CB/HDPE) composites was investigated. The change in resistance ρ is related to the dynamic modulus up to the positive temperature coefficient/negative temperature coefficient (PTCR/ NTCR) transition temperature.

To improve the parameters of PTCR composites, various technological approaches have been used related to filler modification, crosslinking of polymer matrix, use of filler hybrids and use of binary polymer matrix [

60].

In [

61], linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE)/high-density polyethylene (HDPE) blends were filled with dispersed graphite. The results showed that the resistivity at room temperature gradually decreased, and the PTC effect was significantly enhanced by adjusting the graphite content or the LLDPE/HDPE ratio. A dual PTC effect was found to be due to the volumetric expansion of the co-crystallization or their fractions.

Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) composites filled with carbon black (CB) and carbon fiber (CF) were prepared by melt blending method. The effects of the mixture of CB on the PTCR effect and negative NTCR effect, as well as the percolation threshold, were investigated [

62]. PTC -materials are characterized by operating modes with switching temperatures in the range of 50-400 °C [

63].

In order to improve PTCR composites, it is necessary to provide a decrease in electrical resistance at room temperature and an increase in resistance near the melt temperature of the polymer [

64]. In [

65], PTCR composite by blending a semi-crystalline EVA polymer with low melting point (Tm) with an amorphous polymer (PS or PVAc) with low glass transition temperature (Tg), while inexpensive graphite is selected as a conductive filler. PTCR materials were obtained with low switching temperature (<30 °C) and low resistivity at room temperature (102 Ohm·m).

To overcome these intrinsic disadvantages, PTCR composites based on CF - CNTs have been utilized as novel conductive fillers in polymer matrices due to their large aspect ratio (length-to-diameter ratio), integrated graphite microstructure, high electrical conductivity and high thermal stability [

66,

67].

The dispersed particles in the polymer matrix have an effect on the PTCR [

68]. This was revealed for CNT/polypropylene (PP) composites with a partitioned microstructure. For the conductive properties of CNT/PP composites, the percolation threshold decreased from 1.32 vol% to 0.44 vol% when the matrix particle size increased from 20 to 1200 μm, which showed an inverse correlation effect. The controlled characteristics of PTCR in resistance relate to the formation of conductive pathway microstructure and thermal volumetric expansion of polymer matrix particles.

Elastomers allow increasing the temperature regime and obtaining a more flexible heater [

69]. A composite based on amorphous polystyrene/polyurethane and MWCNTs (PS/PU- MWCNTs) was presented in [

70]. The ultra-low percolation threshold (about 0.01 wt.%) and high electrical conductivity were achieved due to the conductive networks of MWCNTs in the interconnected "island chain" of PU.

In [

71], a multicomponent material (silicone rubber/ paraffin/ graphite/ carbon nanotubes) with PTCR (intensity 6.3) and resistivity of only 400 Ohm-cm in the temperature region from -20 °C to 120 °C was used. In this work, a material with PTC and low Curie point in the conducting region of the composite (based on hydroxyl-terminated polydimethylsiloxane) is considered. When the mass fraction of n-tetradecane/HTPDMS (hydroxyl-terminated polydimethylsiloxane) is 1:1 and the mass fraction of PDMS/HTPDMS is 1:2, the low Curie point PTCR material exhibits a Curie temperature of 1 °C with a low-temperature resistivity of only 5.37 Ohm cm and a PTCR intensity of 2.99 [

72].

In [

73], a new PTCR composite material with a Curie temperature of 34 °C was prepared and a thermal control method combining the PTCR material with a proportional-integral-differential (PID) control algorithm was proposed.

5. Practice of Using Heaters

At the initial stage of development and introduction of electric technologies, metal heaters with high electrical resistance (the first generation of electric heating means) were widely used. However, having a number of indisputable advantages, such as cheapness and simplicity of manufacturing, there was a serious disadvantage - low service life and the need for the use of automatic regulation. In connection with this circumstance, a new type of ceramic-based electric heaters (second generation) was developed, for which, due to the selection of different types of materials, a special functional dependence between electrical resistance and ambient temperature was formed [

74].

BaTiO

3 doped (BT) [

75] (third generation) was used as materials for ceramic heaters with PTCR. For BT, the phase transition temperature was about 120 °C. To increase the upper temperature threshold, PbTiO3 (PT) was introduced into BaTiO

3 .

However, in the presence of undeniable advantages associated with the self-regulation effect, such materials have significant disadvantages, including the presence of PT lead in their composition, which made the operation and production of such materials environmentally hazardous. The rejection of lead led to the development of new technologies with lanthanum and manganese additives [

76].

Lanthanum and manganese additives act as donor-acceptor alloying additives to BT [

77]. Heating elements with PTCR based on BT and alloying additives are produced by screen printing in the form of rods or disks with subsequent high-temperature sintering.

The next milestone in the development of electrically heated technologies was the appearance of polymer composites with electrically conductive fillers. The PTCR effect in them can occur for several reasons. One of the main ones are: the presence of a phase transition in the polymer, occurring before the melting temperature of the polymer, and the difference in the coefficients of thermal expansion between the polymer matrix (fourth generation) [

78]. Silicone can also be used as a matrix for electric heaters [

79].

Such heaters can be used to heat large areas, which include pipelines, stormwater pipes, floor and ceiling structures, or aircraft de-icing systems [

80]. A composite film [

81] containing MWCNT/graphene with a weight ratio of 9/1 showed the lowest specific electrical resistance of ∼73 Ohm·cm. The maximum temperatures of the composite films can be precisely controlled by tuning the ratio of hybrid carbon filler with thermal stability up to ∼250 °C.

A simple CNT-based heater [

82] achieves a maximum temperature of 95.0 °C, whereas the AgNP/CNT hybrid heater achieves a higher maximum temperature of 118.6 °C when powered by an 8 V supply.

Nanocomposites with dispersed metals and MWCNTs were presented in [

83]. Elongated aluminum inclusions (60 μm in size) and spherical bronze inclusions (12-30 μm) were observed in the nanocomposites. The composites containing MWCNT, Co-Mo/Al

2O

3 - MgO and bronze (3 wt%) had the maximum thermal and electrical conductivity. The obtained nanocomposites were used to fabricate heaters. The heaters were heated by applying a voltage of 12-24 V.

In [

84], MWCNTs were synthesized by microwave method. MWCNTs were filamentous (10 μm) and were interwoven into bundles (40-60 nm in diameter). The MWCNTs synthesized by microwave method showed high stability at a potential of 250 V in an electrical resistance heater due to the presence of Fe on the surface of MWCNTs. The developed heater can operate efficiently at 220 V.

6. Using Neural Networks to Form Conductive Composites

The need for the application of AI in composite materials technology is due to AI's self-learning ability, faster computer processing time for large datasets, and potential for high-precision results [

85].

In order to mimic human reasoning decision-making options, AI seeks to program machine intelligence, encouraging them to learn from experience and adapt to changes in the environment [

86,

87].

In [

88], carbon black (CB), carbon nanotubes (CNT) and expanded graphite (EG) with different weight percentages are added to epoxy resin as input factors and the electrical conductivity of the samples is measured as a response factor. The input factors are analyzed and Taguchi method, Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) are developed and used to predict the response factor. In [

89], a methodology for electrical potential based fault detection using an artificial neural network is presented.

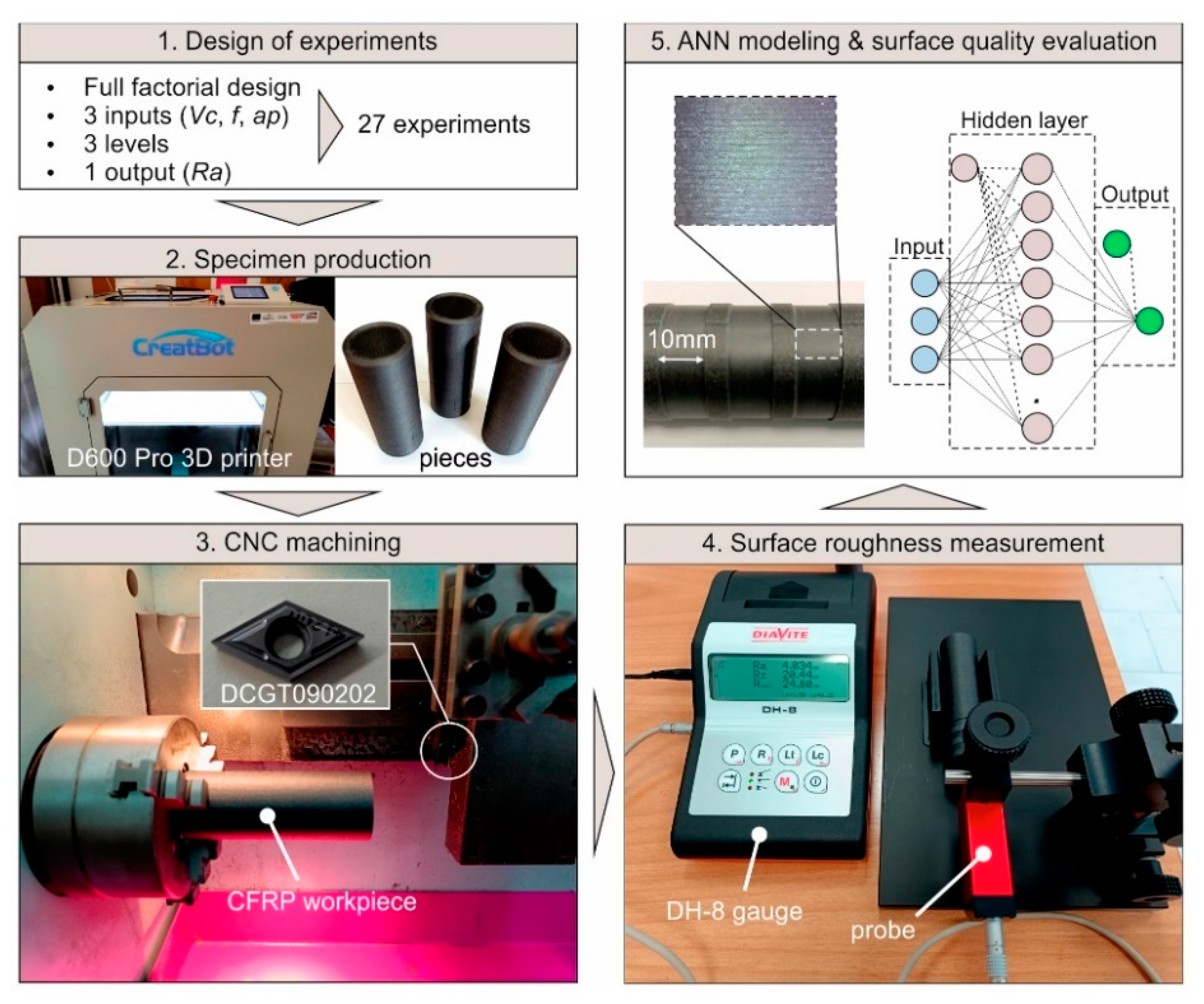

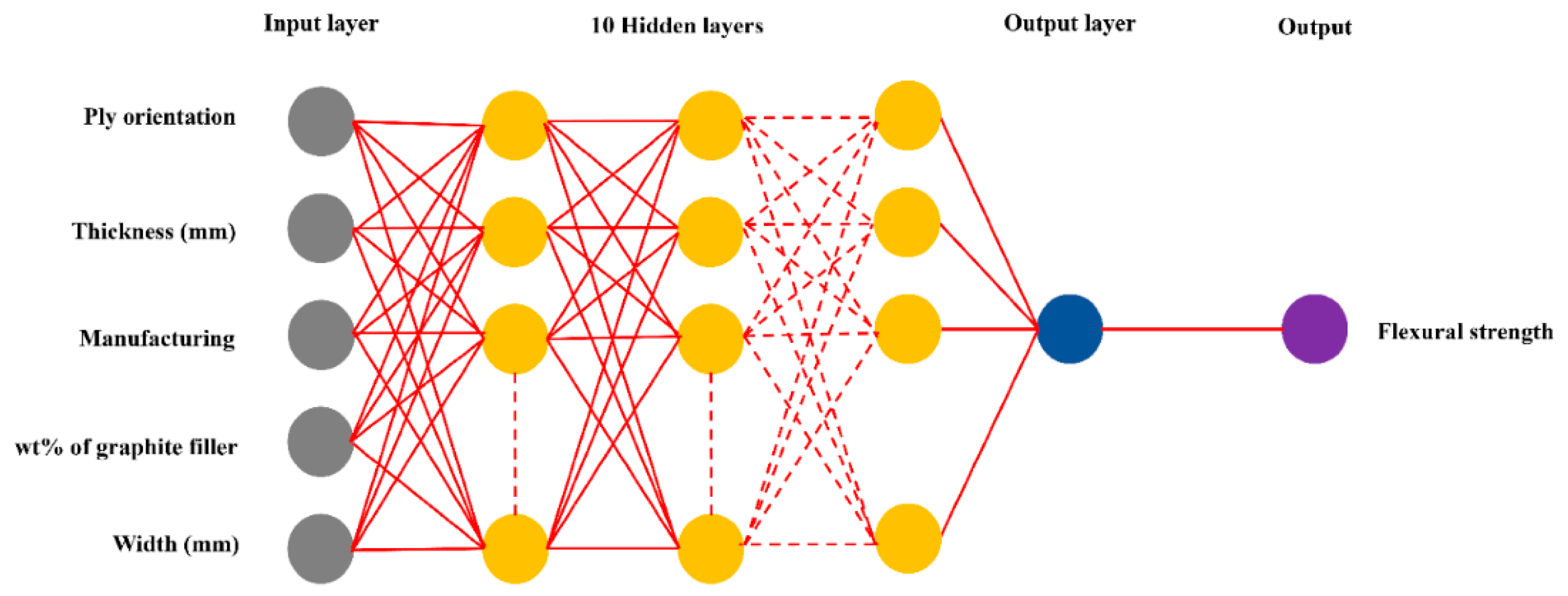

Figure 9 shows the methodology of using machine learning techniques for polymers [

90].

Deep learning allows for fast processing of information as well as self-learning capabilities and the potential to produce highly accurate results [

91].

In [

92] artificial neural network (ANN) model was selected and optimized in the architecture based on parametric study the proposed AI method performs well for nanocomposites (performance in both training and testing phase where the correlation coefficient is 0.986 for training part and 0.978 for testing part).

In [

93], a supervised deep learning predictor was developed for direct, intelligent and instantaneous inference of conductive heat transfer topologies. The architecture of the proposed supervised predictor consists of an encoder to reduce the dimensionality of the input data and a decoder.

A conditional generative-adversarial neural network model was developed to model the high-dimensional and nonlinear mapping between surface profile and surface temperature of a series of effusion-cooled plates. The change in surface temperature of the porous plates was reduced by about 50% compared to a structure with a conventional array of holes. [

94].

7. Conclusions

The paper presents a review of electrically conductive polymer composites based on reactoplastics, thermoplastics and elastomers. The use of dispersed conductive structures in polymer mattresses makes it possible to form a whole class of composites - conductive polymer composites. Different combinations of polymers and dispersed fillers influence the formation of positive temperature coefficient of resistance, which allows to realize the effect of temperature self-regulation. An effective option for creating a conductive composite used for electric heating is carbon nanotubes. This is due to the fact that CNTs at low concentrations allow to achieve high electrical conductivity. It should be noted that carbon nanotubes with surface metallization allow to create effective heaters with the possibility of working at 220V. All types of matrices have certain advantages and disadvantages, but their application is associated with the need to realize certain physical and mechanical properties. Neural networks can be used to improve the properties of conductive composites, which provide fundamentally new opportunities.

- -

Consider dispersed conductive fillers for polymer composites, which can be metal or carbon based;

- -

PTCs can be two-stage, which is due to the use of two types of conductive structures (blends of CU with carbon fiber (CF)). In PC, two-stage PTC can be formed in filled immiscible semi-crystalline polymer blends. Binary polymer matrices, also have an effect on PTC. In some cases it is effective to combine different types of polymers (silicone rubber/paraffin) and dispersed fillers (graphite/CNTs), which makes it possible to work at temperatures up to 120 °C. CNTs make it possible to form PTCs in PCs at lower concentrations, which allows maintaining mechanical strength and using more efficient heat release modes.

- -

The practice of polymer heaters application shows that the heaters can be designed for various voltages from 2 to 220 V. The use of metallised CNTs allows to significantly increase the stability of heaters during operation.

- -

Analyze the application of neural networks in polymer composite technologies. These attempts to implement deep learning in external cooling in this study were successful, and future work can further focus on generalizing the simulation and improving the robustness of the optimization approach

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Aleksei V. S. and Alexander.V. S.; software, M.A.K.; validation, V.V.K. and M.A.K.; formal analysis, M.A.K.; investigation, Aleksei V. S.; resources, Alexander.V. S.; data curation, M.A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Aleksei V. S.; writing—review and editing, Aleksei V. S.; visualization, Aleksei V. S.; supervision, V.V.K.; project administration, Alexander.V. S.; funding acquisition, Aleksei V. S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (Grant No. 24-29-00855, https://rscf.ru/project/24-29-00855/).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| TCR |

temperature coefficient of resistance; |

| NTR |

negative temperature coefficient of resistance; |

| PTR |

positive temperature coefficient of resistance; |

| CNT |

carbon nanotubes; |

| MWCNTs |

multiwalled carbon nanotubes; |

| PDMS |

polydimethylsiloxane; |

| PU |

polyurethane; |

| TPU |

thermoplastic polyurethane; |

| AI |

artificial intelligence |

References

- Roy, N.; Sengupta, R.; Bhowmick, A.K. Modifications of carbon for polymer composites and nanocomposites. Progress in Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 781–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sobrado, O.; Rodriguez, D.; Losada, R.; Rodriguez, E. Evaluation of conductive smart composite polymeric materials for potential applicationsin structural health monitoring and strain detection. Func.Compos. Mater. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cen, F.; Yu, X.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, S.; Yu, Y. Polymer positive temperature coefficient composites with room-temperature Curie point and superior flexibility for self-regulating heating devices. Polym. 2022, 265, 125587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, D.; Jin, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Li, S.; Li, C. Preparation and PTC properties of multilayer graphene/CB/HDPE conductive composites with different cross-linking systems. Mater. Sci. in Semiconductor Processing 2024, 173, 108124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenta, E.W.; Mebratie, B.A. Advancements in Carbon Nanotube-Polymer Composites: Enhancing Properties and Applications through Advanced Manufacturing Techniques. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiar, S.U.H.; Dong, T.; Xue, B.; Ali, S.; Sattar, H.; Dong, W.; Fu, Q. Positive temperature coefficient materials for intelligent overload protection in the new energy era. Mater.Today 2023, 71, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnaoui, M.E.; Graça, M.P.F.; Achour, M.E.; Costa, L.C.; Outzourhit, A.; Oueriagli, A.; Harfi, A.E. Effect of temperature on the electrical properties of copolymer/carbon black mixtures. J. of Non-Crystalline Solids 2010, 356, 1536–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J. Review of polymers in the prevention of thermal runaway in lithium-ion batteries. Energy Reports 2020, 6, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Zhao, F.; Wang, F.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, S.; Cui, J.; Yan, Y. Highly conductive and light-weight acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene copolymer/reduced graphene nanocomposites with segregated conductive structure. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. and Manufacturing. 2019, 122, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahryari, Z.; Gheisari, K.; Yeganeh, M.; Ramezanzadeh, B. Designing a dual barrier-self-healable functional epoxy nano-composite using 2D-carbon based nano-flakes functionalized with active corrosion inhibitors. J.of Mater. Res. and Technology 2022, 22, 2746–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Han, J. Effect of hydroxylated carbon nanotubes on the thermal and electrical properties of derived epoxy composite materials. Results in Phys. 2020, 18, 103246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.-K.; Liu, C.; Zhang, D.-L.; Song, Y.-H.; Sun, K.; Xu, H.-P.; Dang, Z.-M. Particle packing theory guided multiscale alumina filled epoxy resin with excellent thermal and dielectric performances. J. of Materiomics 2022, 8, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Du, J.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Yan, C.; Lei, W. Fabrication and Tribological Properties of Epoxy Nanocomposites Reinforced by MoS2 Nanosheets and Aligned MWCNTs. Mater. 2024, 17, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Q.M.; Li, J.B.; Wang, L.F.; Zhu, J.W.; Zheng, M. Electrically conductive epoxy resin composites containing polyaniline with different morphologies. Mater. Sci. and Eng. A 2006, 448, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.-H.; Yin, G.-Z.; Prolongo, S.G. Review of thermal conductivity in epoxy thermosets and composites: Mechanisms, parameters, and filler influences. Adv. Industrial and Eng. Polym. Res. 2023, 7, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, K. Fractal characterization of electrical conductivity and mechanical properties of copper particulate polyester matrix composites using image processing. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 3309–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Fairclough, J.P.A. Electrical curing of carbon fibre composites with conductive epoxy resins. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 185, 108296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Yu, G. Effects of Varying Nano-Montmorillonoid Content on the Epoxy Dielectric Conductivity. Molecules. 2024, 29, 4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungulescu, E.-M.; Stancu, C.; Setnescu, R.; Notingher, P.V.; Badea, T.-A. Electrical and Electro-Thermal Characteristics of (Carbon Black-Graphite)/LLDPE Composites with PTC Effect. Mater. 2024, 17, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Laboulais, J.; García-Jareño, J.J.; Agrisuelas, J.; Vicente, F. EIS Behavior of Polyethylene + Graphite Composite Considered as an Approximation to an Ensemble of Microelectrodes. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Kinloch, A.J.; Ang, A.S.M. Modelling Fatigue Crack Growth in High-Density Polyethylene and Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene Polymers. Polym. 2024, 16, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zois, H.; Mamunya, Y.P.; Apekis, L. Structure and dielectric properties of a thermoplastic blend containing dispersed metal. Macromolecular Symposia 2003, 198, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.A.U.; Chang, S.H. Flexible strain sensors for wearable applications fabricated using novel functional nanocomposites: A review. Compos. Structures 2022, 284, 115214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.M.; Athawale, A.A. Electrically conductive Silicone/Organic Polymer composites. Silicon 2013, 6, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhou, W.; Wen, Z.; Wang, W.; Zeng, X.; Sun, R.; Ren, L. Thermally conductive and compliant polyurethane elastomer composites by constructing a tri-branched polymer network. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Lee, J.; Jung, D.; Shim, S.E. Thermal and electrical conduction behavior of alumina and multiwalled carbon nanotube incorporated poly(dimethyl siloxane). Thermochimica Acta 2010, 512, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Z.; Cheng, X.; Islam, M.S.; Sangkarat, P.; Chang, W.; Brown, S.A.; Wu, S.; Zhang, J.; Han, Z.; Peng, S.; Wang, C.H. Synergistically enhancing the electrical conductivity of carbon fibre reinforced polymers by vertical graphene and silver nanowires. Composites Part a Appl. Sci. and Manufacturing 2023, 168, 107463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehvari, S.; Sanchez-Vicente, Y.; González, S.; Lafdi, K. Conductivity Behaviour under Pressure of Copper Micro-Additive/Polyurethane Composites (Experiment and Modelling). Polym. 2022, 14, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourabbas, B.; Peighambardoust, S.J. PTC effect in HDPE filled with carbon blacks modified by NI and AU metallic particles. J. of Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 105, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchegolkov, A.V.; Shchegolkov, A.V.; Zemtsova, N.V.; Vetcher, A.A.; Stanishevskiy, Y.M. Properties of Organosilicon Elastomers Modified with Multilayer Carbon Nanotubes and Metallic (Cu or Ni) Microparticles. Polym. 2024, 16, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanapitsas, A.; Tsonos, C.; Logakis, E.; Pandis, C.; Pissis, P.; Kontou, E.; Mamunya, Y.P.; Lebedev, E.V.; Delides, C.G. PTC Effect and Structure of Polymer Composites Based on Polypropylene/Co-Polyamide Blend Filled with Dispersed Iron. 25th International Conference on Microelectronics 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamunya, Y.P.; Muzychenko, Y.V.; Lebedev, E.V.; Boiteux, G.; Seytre, G.; Boullanger, C.; Pissis, P. PTC effect and structure of polymer composites based on polyethylene/polyoxymethylene blend filled with dispersed iron. Polym. Eng. and Sci. 2006, 47, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, R.; Martín-Palma, R.J. Enhancing piezoresistive sensitivity of PEDOT:PSS-based strain sensors through nickel microparticles incorporation. J.of Mater. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacem, A.; Modi, S.; Yadav, V.K.; Islam, S.; Patel, A.; Dawane, V.; Jameel, M.; Inwati, G.K.; Piplode, S.; Solanki, V.S.; Basnet, A. Recent Advances in Methods for Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes and Carbon Nanocomposite and their Emerging Applications: A Descriptive Review. J. of Nanomaterials 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhakeem, M.R.H. Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Composites and its Application; A Review. Brilliance Res. of Artificial Intelligence 2022, 2, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Takeuchi, A.; Ozawa, M.; Li, X.; Saigo, K.; Kitazawa, K. C60 fullerol formation catalysed by quaternary ammonium hydroxides. J. of the Chem. Society, Chem. Comm. 1993, 23, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Suárez, A.; Prolongo, S.G. Graphene nanoplatelets. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, Z.T.; Major, A.Á. A review on MWCNTS: the effect of its addition on the polymer matrix. Gradus 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, F.; Jiang, Q.; Zhu, P.; Leu, K.; Zhang, R. Controlled synthesis, properties, and applications of ultralong carbon nanotubes. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 4504–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambraparni, M.; & Wang, S. Separation of Metallic and Semiconducting Carbon Nanotubes. Recent Patents on Nanotechnology. 2010, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sonkar, P.K.; Narvdeshwar, N.; Gupta, P.K. Characteristics of carbon nanotubes and their nanocomposites. In Elsevier eBooks; 2021; 99–118. [CrossRef]

- Kostagiannakopoulou, C.; Fiamegkou, E.; Sotiriadis, G.; Kostopoulos, V. Thermal conductivity of carbon nanoreinforced epoxy composites. J. of Nanomaterials 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostagiannakopoulou, C.; Fiamegkou, E.; Sotiriadis, G.; Kostopoulos, V. ; Thermal Conductivity of Carbon Nanoreinforced Epoxy Composites. J. of Nanomaterials. 2016, 1847325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.K.; Eom, T.; Kim, H.; Kang, D.; Lee, S.-E. Independent Heating Performances in the Sub-Zero Environment of MWCNT/PDMS Composite with Low Electron-Tunneling Energy. Polym. 2023, 15, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J.H.; Lee, S.E.; Park, S.H. Effect of Dispersion by Three‐Roll Milling on Electrical Properties and Filler Length of Carbon Nanotube Composites. Mater. 2019, 12, 3823. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Xu, D.; Ding, H.; Xie, J.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, C.; Huang, Q. Multifunctional composite phase change material with electrostatic self-assembly structure based on carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Carbon 2024, 231, 119763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.-H.; Liu, X.-P.; Chen, J.; Wu, M.; Mao, C.-J. Highly thermally conductive PVDF-based composites with well-dispersed carbon nanotubes/graphene-Ag 3D interconnected frame via electrostatic self-assembly. Comp. Comm. 2024, 48, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Wu, J.; Pei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Liao, Y.; Xie, X. Highly thermally conductive yet mechanically robust composites with nacre-mimetic structure prepared by evaporation-induced self-assembly approach. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 405, 126865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Long, G.; Hu, X.; Wong, K.-W.; Lau, W.-M.; Fan, M.; Mei, J.; Xu, T.; Wang, B.; Hui, D. Conductive polymer nanocomposites with hierarchical multi-scale structures via self-assembly of carbon-nanotubes on graphene on polymer-microspheres. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 7877–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, N.J.Y.; Suhaimi, M.F.B.; Ju, D.; Lee, H. Design and development of electric radiant heaters for local heating inside the cabin of electric vehicles. Appl. Thermal Eng. 2024, 256, 124087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk, M.O.; Ahmed, A.; Jalil, M.A.; Islam, M.T.; Shamim, A.M.; Adak, B.; Hossain, M.M.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Functional textiles and composite based wearable thermal devices for Joule heating: progress and perspectives. Appl. Mater.Today. 2021, 23, 101025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.-W.; Wu, D.-H.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.-H.; Li, R.K.Y.; Dang, Z.-M. Enhanced positive temperature coefficient behavior of the high-density polyethylene composites with multi-dimensional carbon fillers and their use for temperature-sensing resistors. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 11338–11344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Liang, X.; Yin, Z.; Xia, K.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Weft-Knitted Fabric for a Highly Stretchable and Low-Voltage Wearable Heater. Adv. Electronic Mater. 2017, 3, 1700193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Lou, H.; Shi, X.; Peng, H. A smart, stretchable resistive heater textile. J. of Mater. Chem. C. 2017, 5, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.-S. Resistivity and Thermal Reproducibility of High-Density Polyethylene Heaters Filled With Carbon Black. Macromolecular Mater. and Eng. 2006, 291, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motloung, B.T.; Dudić, D.; Mofokeng, J.P.; et al. Properties and thermo-switch behaviour of LDPE mixed with carbon black, zinc metal and paraffin wax. 2017, J. Polym Res. 24, 43. [CrossRef]

- Di, W.; Zhang, G.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, Z. Two-step PTC effect in immiscible polymer blends filled with carbon black. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Di, G., Y. Zhang, Z. Peng, Z. Zhao, J. of Mater Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 695–697.

- Zheng, Q.; Song, Y.; Wu, G.; Song, X. Relationship between the positive temperature coefficient of resistivity and dynamic rheological behavior for carbon black-filled high-density polyethylene. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 2003, 41, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, J. Designs of conductive polymer composites with exceptional reproducibility of positive temperature coefficient effect: A review. J. of Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 49677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, B. Positive temperature coefficient effect and mechanism of compatible LLDPE/HDPE composites doping conductive graphite powders. J. of Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 46453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, W.; Zhang, G.; Xu, J.; Peng, Y.; Wang, X.; Xie, Z. Positive-temperature-coefficient/negative-temperature-coefficient effect of low-density polyethylene filled with a mixture of carbon black and carbon fiber. J. of Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 2003, 41, 3094–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevananda, T.; Kim, N.H.; Lee, J.H.; Basavarajaiah, S.; Urs, M.D.; Ranganathaiah, C. Investigation of multi-walled carbon nanotube-reinforced high-density polyethylene/carbon black nanocomposites using electrical, DSC and positron lifetime spectroscopy techniques. Polym. Inter. 2009, 58, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoxiang, H.; Ou, D.; Wu, S.; Luo, Y.; Ma, Y.; Sun, J. A mini review on factors affecting network in thermally enhanced polymer composites: filler content, shape, size, and tailoring methods. Adv. Compos. and Hybrid Mater. 2022, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cen, F.; Yu, X.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, S.; Yu, Y. Polymer positive temperature coefficient composites with room-temperature Curie point and superior flexibility for self-regulating heating devices. Polym. 2022, 265, 125587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Zhu, Z.H.; Li, Z. Electron tunnelling and hopping effects on the temperature coefficient of resistance of carbon nanotube/polymer nanocomposites. Phys.Chem. Chem.Phys. 2017, 19, 5113–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.-P.; Dang, Z.-M.; Shi, D.-H.; Bai, J.-B. Remarkable selective localization of modified nanoscaled carbon black and positive temperature coefficient effect in binary-polymer matrix composites. J. of Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hu, C.; Zhai, W.; Zhao, S.; Zheng, G.; Dai, K.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Particle size induced tunable positive temperature coefficient characteristics in electrically conductive carbon nanotubes/polypropylene composites. Mater. Lett. 2016, 182, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Porwal, H.; Tu, W.; Evans, J.; Newton, M.; Busfield, J.J.C.; Peijs, T.; Bilotti, E. Universal control on pyroresistive behavior of flexible Self-Regulating heating devices. Adv. Functional Mater. 2017, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.; Zhao, L.; Zou, J.; Zhang, P. High positive temperature coefficient effect of resistivity in conductive polystyrene/polyurethane composites with ultralow percolation threshold of MWCNTs via interpenetrating structure. Reactive and Functional Polym. 2020, 151, 104562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.-M.; Yang, Y.-F.; Shen, Y.-T.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, W.; Chen, H.; Cheng, W.-L. Positive temperature coefficient material based on silicone rubber/ paraffin/ graphite/ carbon nanotubes for wearable thermal management devices. Chemical Engineering J. 2024, 493, 152427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jiang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, F.; Li, T. Study on the low Curie point positive temperature coefficient (PTC) material based on the conductive model. Materials Chemistry and Physics. 2023, 312, 128676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-L.; Cheng, W.-L.; Xu, Z.-M.; Yuan, S.; Liu, M.-H. Study on PID temperature control performance of a novel PTC material with room temperature Curie point. International J. of Heat and Mass Transfer. 2016, 95, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G.G. Harman Electrical properties of BaTiO3 containing samarium. Phys Rev, 1957. 106, 1159-1358.

- M. Nakahara, T. Murakami Electronic states of Mn ions in Ba0.97Sr0. 03TiO3 single crystals. J. Appl. Phys 1974, 45, 3795–3800.

- Mächler, D.; Schmidt, R.; Töpfer, J. Synthesis, doping and electrical bulk response of (Bi 1/2 Na 1/2 ) x Ba 1-x TiO 3 + CaO –based ceramics with positive temperature coefficient of resistivity (PTCR). J. of Alloys and Compounds. 2018, 762, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.M.V.; Bobić, J.D.; Grigalaitis, R.; Stojanović, B.D.; Banys, J. LA-doped and LA/MN-co-doped Barium Titanate Ceramics. Acta Physica Polonica A 2013, 124, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.P. Bao, G.D. Liang, S.C. Tjong Positive temperature coefficient effect of polypropylene/carbon nanotube/montmorillonite hybrid nanocomposites. IEEE Trans Nanotechnol. 2009, 8, 729–736.

- Raza, M.A.; Westwood, A.; Brown, A.; Hondow, N.; Stirling, Ch. Characterisation of graphite nanoplatelets and the physical properties of graphite nanoplatelet/silicone composites for thermal interface application. Carbon. 2011, 49, 13–4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, O.; Prolongo, S. G.; Campo, M.; Sbarufatti, C.; Giglio, M. Anti-icing and de-icing coatings based Joule’s heating of graphene nanoplatelets. Composites Science and Technology. 2018, 164, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Jeong, Y.G. Synergistic effect of hybrid carbon fillers on electric heating behavior of flexible polydimethylsiloxane-based composite films. Compos. Sci. and Tech. 2014, 106, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusak, N.; Virtanen, J.; Kangas, V.; Promarak, V.; Yotprayoonsak, P. Enhanced Joule heating performance of flexible transparent conductive double-walled carbon nanotube films on sparked Ag nanoparticles. Thin Solid Films 2022, 750, 139201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Imanova, G.; Shchegolkov, A.V.; Chumak, M.A.; Shchegolkov, A.V.; Kaminskii, V.V.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Habila, M.A. Organosilicon elastomers of MWCNTs and nano-sized metals for heating purposes. Fullerenes Nanotubes and Carbon Nanostructures 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Shchegolkov, A.; Shchegolkov, A.; Chumak, M.A.; Viktorovich, N.A.; Vasilievich, L.K.; Imanova, G.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Habila, M.A. Facile microwave synthesis of multi-walled carbon nanotubes for modification of elastomer used as heaters. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 3975–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Soutis, C.; Ando, D.; Sutou, Y.; Narita, F. Application of deep neural network learning in composites design. European, J.of Mater. 2022, 2, 117–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibrete, F.; Trzepieciński, T.; Gebremedhen, H.S.; Woldemichael, D.E. Artificial Intelligence in Predicting Mechanical Properties of Composite Materials. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishnan, N.; Maleki, F.; Ovens, K.; Reinhold, C.; Forghani, B.; Forghani, R. Brief history of artificial intelligence. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America 2020, 30, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.M.; Sadollah, A.; Al-Shamiri, A.K. Prediction and optimization of electrical conductivity for polymer-based composites using design of experiment and artificial neural networks. Neural Comput & Applic. 2022, 34, 7653–7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Lemoine, G.; Ambur, D. An artificial neural network based damage detection scheme for electrically conductive composite structures. 44th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference 2003. [CrossRef]

- Phunpeng, V.; Saensuriwong, K.; Kerdphol, T.; Uangpairoj, P. The Flexural Strength Prediction of Carbon Fiber/Epoxy Composite Using Artificial Neural Network Approach. Mater. 2023, 16, 5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanullah, M.A.; Habeeb, R.A.A.; Nasaruddin, F.H.; Gani, A.; Ahmed, E.; Nainar Imran, A.S.M. Deep learning and big data technologies for IoT security. Computer Communications. 2020, 151, 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, N.X.; Le, T.-T.; Le, M.V. Development of artificial intelligence based model for the prediction of Young’s modulus of polymer/carbon-nanotubes composites. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2021, 29, 5965–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Liu, Z.; Hong, J. Method for directly and instantaneously predicting conductive heat transfer topologies by using supervised deep learning. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 109, 104368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Dai, W.; Rao, Y.; & Chyu, M.K. (2019). Optimization of the hole distribution of an effusively cooled surface facing non-uniform incoming temperature using deep learning approaches. International J. of Heat and Mass Transfer. 2019, 145, 118749. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).