Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

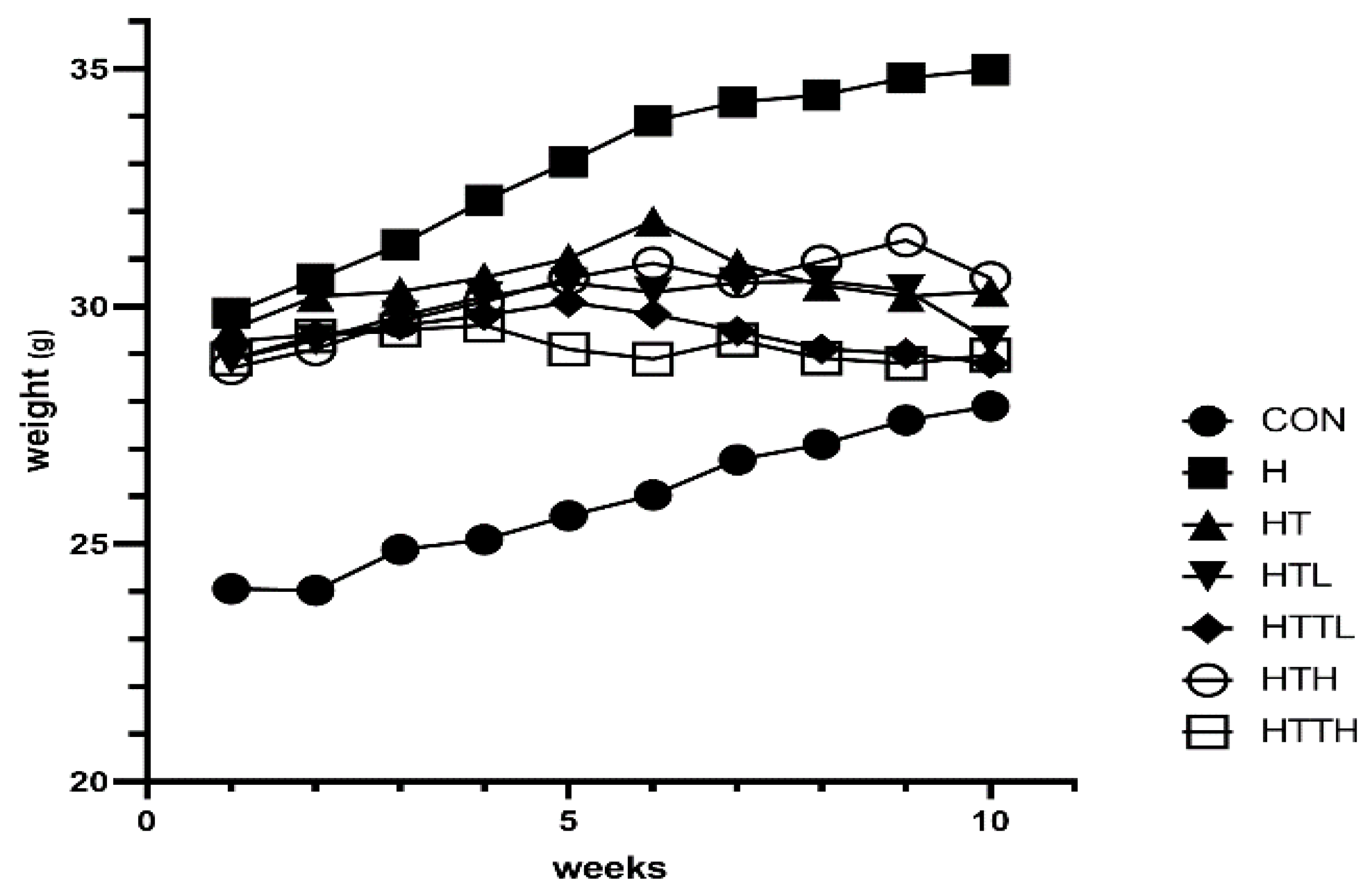

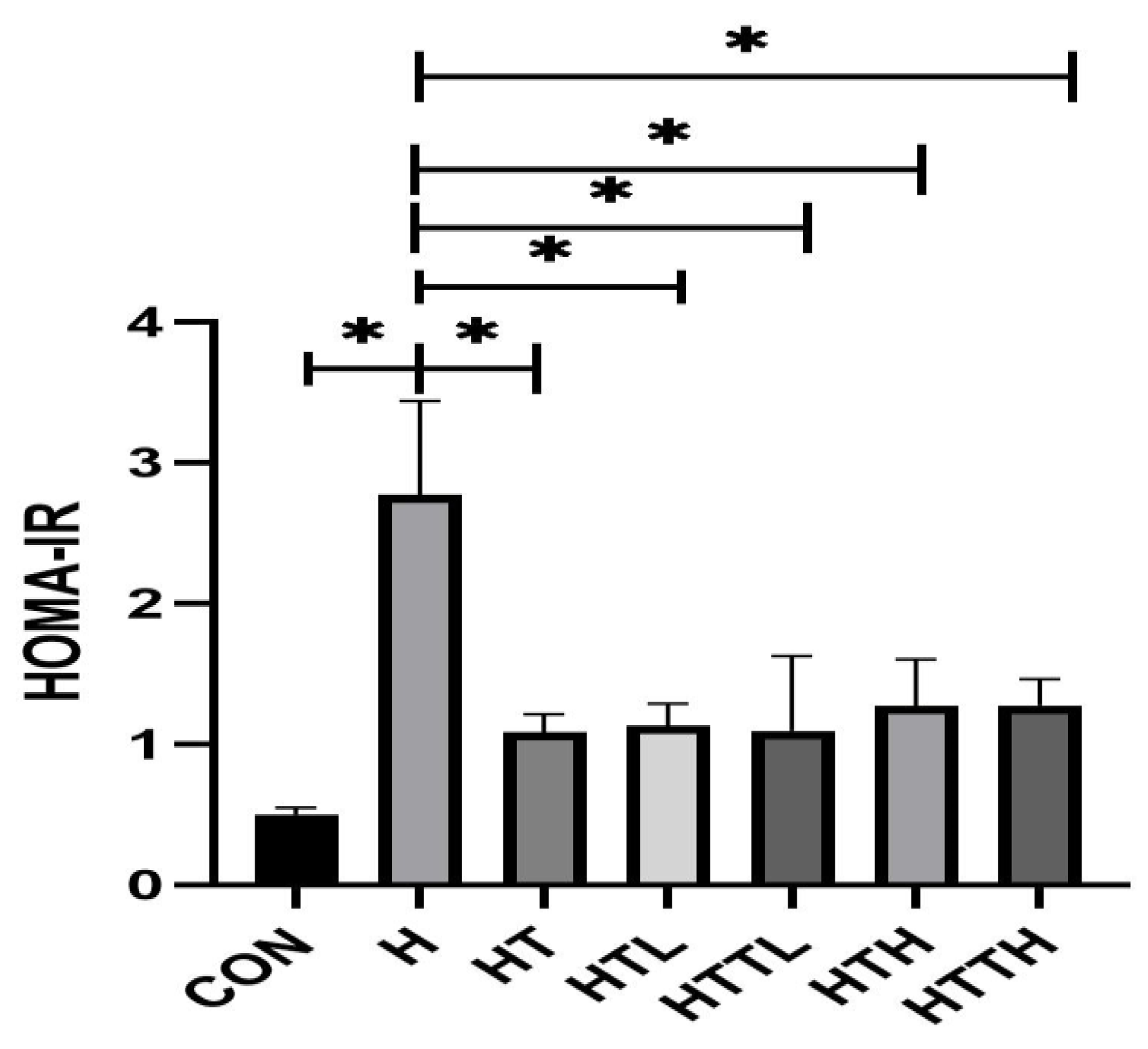

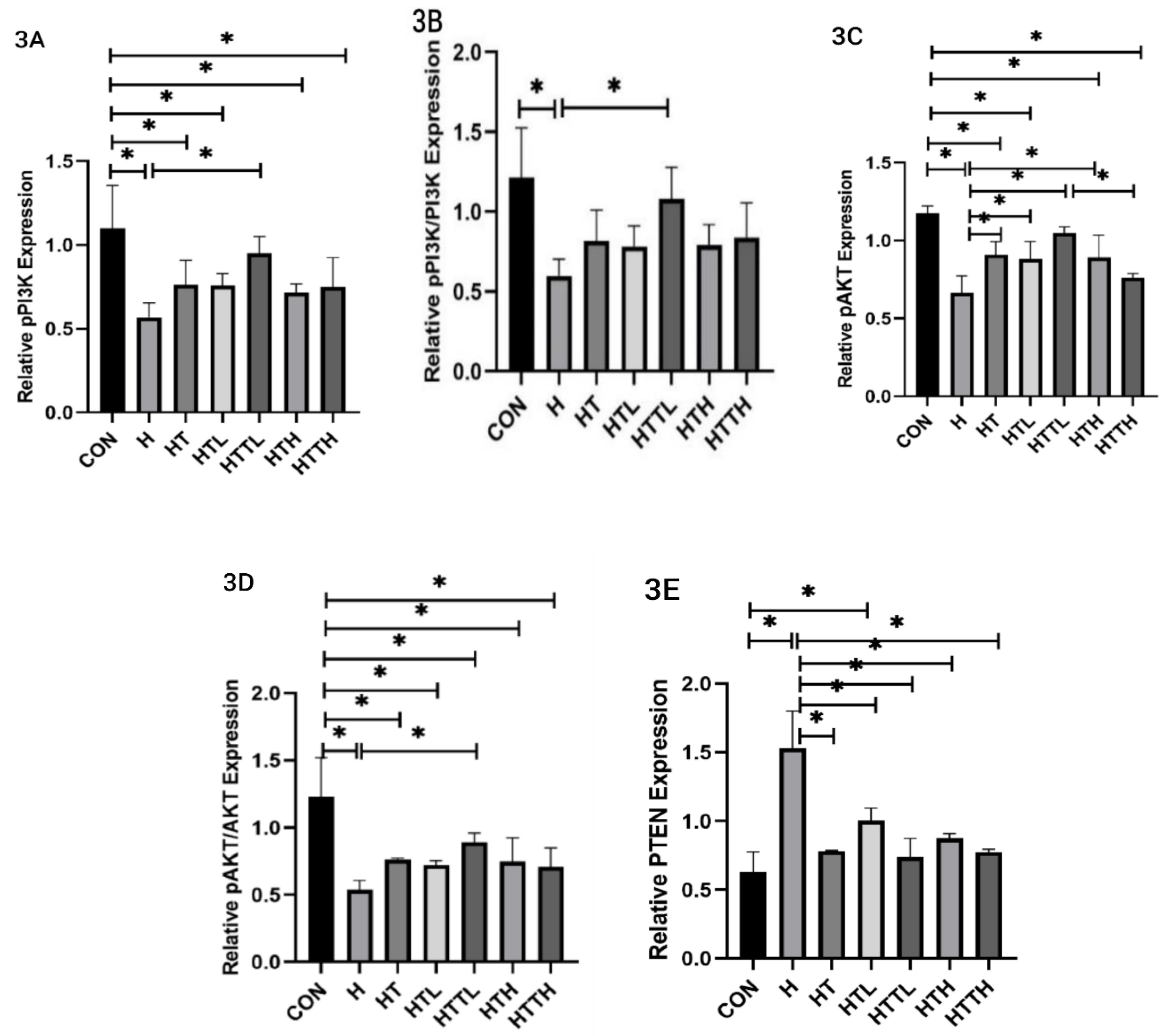

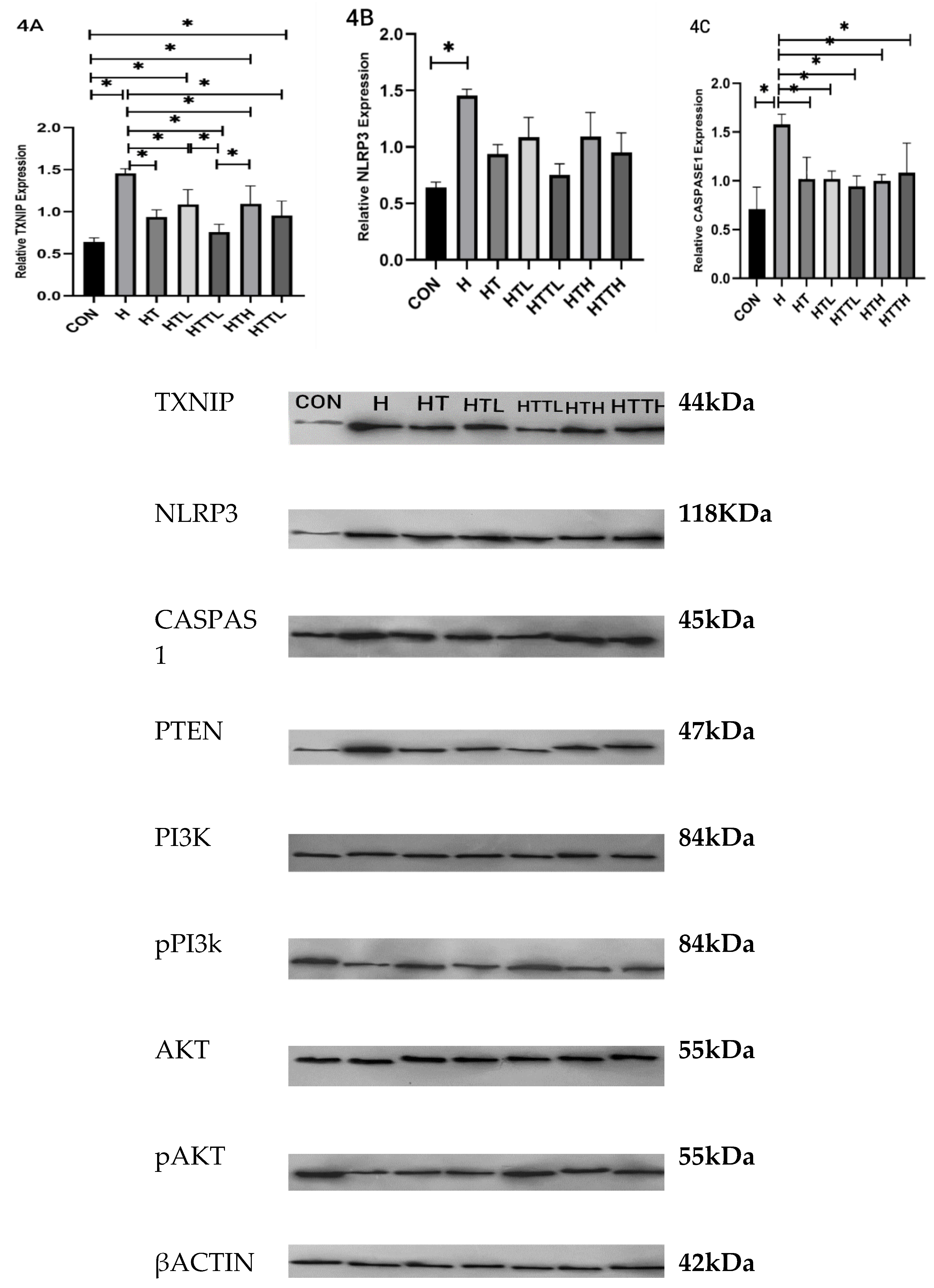

Background: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become one of the most prevalent diseases in recent decades, expanding alongside obesity in society. It typically begins with insulin resistance and progresses through the activation of inflammatory pathways.Purpose: The aim of this study was to explore the effects of taurine supplementation and high-intensity interval training (HIIT) on the TXNIP/NLRP3/CASPASE1 and PI3K/AKT/PTEN pathways in male miceC57BL/6 fed a high fat diet. Methods: Fifty-four male C57BL/6J mice were randomly divided into two groups: a control diet group (n=8) and a high-fat diet (HFD) group to induce NAFLD (n=48). After 12 weeks, HFD group further divided into six subgroups: HFD control (n=8), HFD+ HIIT (n=8), HFD+ 2.5%taurine supplementation (n=8), HFD+HIIT+ 2.5% taurine supplementation (n=8), HFD+ 5%taurine supplementation (n=8), and HFD+ HIIT+ 5%taurine supplementation (n=8). The exercise protocol consisted of 10 weeks of HIIT, five days per week, and taurine supplementation was administered in water solubility throughout the entire period.Results: There were significant differences between the control and HFD groups in terms of weight and liver enzymes levels. Additionally, a significant difference was observed in the HOMA2 index between HFD control and the other intervention groups. The HFD affected the PI3K/AKT/PTEN and TXNIP/NLRP3/CASPASE1 pathways. Taurine supplementation and HIIT had a positive impact on the phosphorylation of PI3K and AKT and expression of PTEN and also TXNIP and caspase1 reversing the effects of the HFD. results indicated that a lower dose of taurine had a stronger effect, particularly on the TXNIP pathway.Conclusion: In summary, combining HIIT with a lower dose of Taurine supplementation may be more effective than either intervention alone in mitigating the progression of NAFLD in male C57BL/6 mice.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Animal Models

Exercise Protocol

Blood Analysis

Histological Analysis of Liver Sections

Western Blot Analysis

Assessment of Insulin Sensitivity in Mice Subjects

Statistical Analysis

Results

Body Weight and Blood Samples

Effects of Different Doses of Taurine and HIIT on Fasting Blood Glucose, Insulin and Liver Glycogen and Insulin Sensitivity

Effects of Different Doses of Taurine and HIIT on PI3K, AKT, and PTEN Expression in the Liver

Effects of Different Doses of Taurine and HIIT on TXNIP, NLRP3, and Caspase-1 Expression in the Liver

Discussions

Conclusions

Abbreviation

References

- Abdollahi M, Marandi SM, Ghaedi K. ; et al. Insulin-Related Liver Pathways and the Therapeutic Effects of Aerobic Training, Green Coffee, and Chlorogenic Acid Supplementation in Prediabetic Mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 5318245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berná, G.; Romero-Gomez, M. The role of nutrition in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathophysiology and management. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunt EM, Wong VW, Nobili V. ; et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015, 1, 15080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao Z, Fang Y, Lu Y. ; et al. Melatonin alleviates cadmium-induced liver injury by inhibiting the TXNIP-NLRP3 inflammasome. J Pineal Res. 2017, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli AP, Zoppi CC, Barbosa-Sampaio HC. ; et al. Taurine-induced insulin signalling improvement of obese malnourished mice is associated with redox balance and protein phosphatases activity modulation. Liver Int. 2014, 34, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Abaydula, Y.; Li, D.; Tan, H.; Ma, X. Taurine ameliorates oxidative stress by regulating PI3K/Akt/GLUT4 pathway in HepG2 cells and diabetic rats. Journal of Functional Foods. 2021, 85, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai B, Wu Q, Zeng C. ; et al. The effect of Liuwei Dihuang decoction on PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in liver of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) rats with insulin resistance. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 192, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding C, Zhao Y, Shi X. ; et al. New insights into salvianolic acid A action: Regulation of the TXNIP/NLRP3 and TXNIP/ChREBP pathways ameliorates HFD-induced NAFLD in rats. Scientific Reports. 2016, 6, 28734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Xu, X. Effects of regular exercise on inflammasome activation-related inflammatory cytokine levels in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 2338–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farese, R.V.; Jr Zechner, R.; Newgard, C.B.; Walther, T.C. The problem of establishing relationships between hepatic steatosis and hepatic insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng J, Qiu S, Zhou S. ; et al. mTOR: A Potential New Target in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022, 23, 9196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile CL, Nivala AM, Gonzales JC. ; et al. Experimental evidence for therapeutic potential of taurine in the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011, 301, R1710–R1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, H.M.A.; Sahar, N.E.; ZhuGe, D.L.; Huh, J.Y. Exercise Inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Obese Mice via the Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Meteorin-like. Cells. 2021, 10, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khakroo Abkenar, I.; Rahmani-Nia, F.; Lombardi, G. The Effects of Acute and Chronic Aerobic Activity on the Signaling Pathway of the Inflammasome NLRP3 Complex in Young Men. Medicina 2019, 55, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Chen, W.T.; Chen, S.Y.; Lee, T.M. Taurine Alleviates Sympathetic Innervation by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome in Postinfarcted Rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2021, 77, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R.; Mohanty, S.R. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a review and update. Dig Dis Sci. 2010, 55, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Xu P, Wang Y. ; et al. Different Intensity Exercise Preconditions Affect Cardiac Function of Exhausted Rats through Regulating TXNIP/TRX/NF-ĸB(p65)/NLRP3 Inflammatory Pathways. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020, 2020, 5809298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Zhang YR, Cai C.; et al. Taurine Alleviates Schistosoma-Induced Liver Injury by Inhibiting the TXNIP/NLRP3 Inflammasome Signal Pathway and Pyroptosis. Infect Immun. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, I.N.; Hafez, S.S.; Fairaq, A.; Ergul, A.; Imig, J.D.; El-Remessy, A.B. Thioredoxin-interacting protein is required for endothelial NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death in a rat model of high-fat diet. Diabetologia. 2014, 57, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, I.N.; Sarhan, N.R.; Eladl, M.A.; El-Remessy, A.B.; El-Sherbiny, M. Deletion of Thioredoxin-interacting protein ameliorates high fat diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis through modulation of Toll-like receptor 2-NLRP3-inflammasome axis: Histological and immunohistochemical study. Acta Histochem. 2018, 120, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S. Role of taurine in the pathogenesis of obesity. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2015, 59, 1353–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S.; Ono, A.; Kawasaki, A.; Takenaga, T.; Ito, T. Taurine attenuates the development of hepatic steatosis through the inhibition of oxidative stress in a model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in vivo and in vitro. Amino Acids. 2018, 50, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrou M, Bourgoin L, Foti M. PTEN in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease/Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis and Cancer. Digestive Diseases. 2010, 28, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyzos, S.A.; Kountouras, J.; Mantzoros, C.S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From pathophysiology to therapeutics. Metabolism 2019, 92, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, E.E.; Wong, V.W.; Rinella, M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 2212–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, N.; Haseeb, M.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, S. Role of Thioredoxin-Interacting Protein in Diseases and Its Therapeutic Outlook. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.; Nazarali, P.; Alizadeh, R.; rezaeinezhad, N. Effects of Aerobic Interval Training with Citrus aurantium Consumption on Gene Expression of AMPK and PI3K in Liver Tissues of Elderly Rats. Research. Iranian Journal of Nutrition Sciences and Food Technology 2022, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, L.M.; Porter, R.R.; Durstine, J.L. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) for patients with chronic diseases. J Sport Health Sci. 2016, 5, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Sil, P.C. Taurine protects murine hepatocytes against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis by tert-butyl hydroperoxide via PI3K/Akt and mitochondrial-dependent pathways. Food Chemistry. 2012, 131, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satsu H, Gondo Y, Shimanaka H. ; et al. Signaling Pathway of Taurine-Induced Upregulation of TXNIP. Metabolites. 2022, 12, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, S.; Kim, H.W. Effects and Mechanisms of Taurine as a Therapeutic Agent. Biomol Ther. 2018, 26, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsan E, Almezgagi M, Gamah M. ; et al. The role of PI3k/AKT signaling pathway in attenuating liver fibrosis: a comprehensive review. Review. Frontiers in Medicine. 2024, 11, 1389329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shykholeslami, Z.; Abdi, A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Barari, A. Effect of Continuous Aerobic Training with Citrus Aurantium L. on Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinases Gene Expression in the Liver Tissue of the Elderly Rats. Research. Journal title. 2021, 29, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surai, P.F.; Earle-Payne, K.; Kidd, M.T. Taurine as a Natural Antioxidant: From Direct Antioxidant Effects to Protective Action in Various Toxicological Models. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Pang, X. Thioredoxin-interacting Protein as a Common Regulation Target for Multiple Drugs in Clinical Therapy/Application. Cancer Translational Medicine. 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandanmagsar B, Youm YH, Ravussin A. ; et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2011, 17, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, H.; Lu, Y. Effects of Different Intensity Exercise on Glucose Metabolism and Hepatic IRS/PI3K/AKT Pathway in SD Rats Exposed with TCDD. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 13141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wen, D. High-intensity interval versus moderate-intensity continuous training: Superior metabolic benefits in diet-induced obesity mice. Life Sci. 2017, 191, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Hu J, Liu Y. ; et al. Aerobic Exercise Improves Synaptic-Related Proteins of Diabetic Rats by Inhibiting FOXO1/NF-κB/NLRP3 Inflammatory Signaling Pathway and Ameliorating PI3K/Akt Insulin Signaling Pathway. J Mol Neurosci. 2019, 69, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Guo Y, Xu Y. ; et al. HIIT Ameliorates Inflammation and Lipid Metabolism by Regulating Macrophage Polarization and Mitochondrial Dynamics in the Liver of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Mice. Metabolites 2022, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong VW, Wong GL, Tsang SW. ; et al. Metabolic and histological features of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients with different serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009, 29, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang W, Liu L, Wei Y. ; et al. Exercise suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation in mice with diet-induced NASH: a plausible role of adropin. Lab Invest. 2021, 101, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang M, Shi X, Luo M. ; et al. Taurine ameliorates axonal damage in sciatic nerve of diabetic rats and high glucose exposed DRG neuron by PI3K/Akt/mTOR-dependent pathway. Amino Acids. 2021, 53, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Ding, S.; Wang, R. Research Progress of Mitochondrial Mechanism in NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Exercise Regulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 10866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng T, Yang X, Li W. ; et al. Salidroside Attenuates High-Fat Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via AMPK-Dependent TXNIP/NLRP3 Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 8597897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | ALT (U/L) | AST (U/L) | Blood Glucose (mg/dl) | Fasting Insulin (µlu/ml) | Liver Glycogen (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | 62.33±5.78 | 159.66±40.70 | 125±19.20 | 3.55±0.39 | 26.94±4.43 |

| H | 209.66±85.54 | 326.16±57.56 | 382.25±22.21 | 6.51±.37 | 11.83±3.47 |

| HT | 134.50±30.07 | 253.66±90.77 | 233.50±39.07 | 6.43±0.22 | 15.02±1.03 |

| HTL | 146.83±37.60 | 278.66±91.78 | 237.50±45.80 | 6.55±0.42 | 19.91±2.20 |

| HTTL | 119.16±37.99 | 217.50±84.09 | 255.5±56.03 | 5.65±1.84 | 21.72±1.92 |

| HTH | 157.16±34.12 | 290.66±89.66 | 194.25±56.93 | 7.96±1.13 | 14.11±1.35 |

| HTTH | 153.16±33.03 | 284.00±83.63 | 281.50±40.35 | 6.38±0.15 | 15.72±1.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).