1. Introduction

Overweight and obesity have become more common in recent years as a result of dietary and lifestyle changes. In the United States, more than 30% of the population is currently considered obese [

1,

2]. The frequency varies worldwide, but in industrialized countries, a sizable proportion of the population is afflicted. In America, around one-third of people have a BMI exceeding 30 kg/m² [

3]. Obesity is considered the second most important cause of death after smoking. According to Roland Sturm, healthcare costs associated to obesity outweigh those related to smoking [

4]. Obesity is observed not only in adults but also in younger ages, because of excessive sugary beverage intake and prolonged screen time [

5,

6].

Obesity is a complicated metabolic condition that has a substantial influence on reproductive health, especially in women. The disorder is linked to endocrine disruption, chronic inflammation, and vascular dysfunction, which impairs ovulation and endometrial receptivity [

7].

Although elevated leptin levels in obesity are supposed to lower food intake and increase energy expenditure, „leptin resistance” confuses this relationship. This resistance results from reduced leptin transport across the blood-brain barrier and altered intracellular signaling pathways, which are frequently exacerbated by chronic inflammation associated with obesity, emphasizing leptin’s complicated function in reproductive physiology [

8].In obesity, leptin dysregulation impairs not only gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion but also the production of fertility-related hormones, potentially leading to infertility [

9]. Furthermore, leptin receptors found in ovarian tissue directly influence follicular growth [

10]. At the molecular level, leptin has been found to activate the JAK-STAT and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways, which affect downstream targets such as the cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) neuropeptide in the central nervous system. This connection points to a considerable interplay between leptin and CART in the control of energy balance and reproductive function [

10].Obese individuals’ granulosa cells (GCs) have also been found to have elevated CART levels. Leptin signaling induces CART expression, which inhibits important enzymes such as aromatase via transcriptional repression mediated by intracellular signaling cascades such as the CREB and MAPK pathways. This inhibition decreases steroidogenesis, which further impairs ovarian function [

11]. These molecular interactions highlight the complex role of leptin-CART crosstalk in linking metabolic disorders and reproductive health.

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) has a major role in obesity-induced reproductive difficulties because it produces nitric oxide (NO), which is a fundamental regulator of vascular tone and cellular signaling. NO is a cellular messenger and effector molecule known for its simple structure, fast diffusion, and short biological half-life. As an inorganic free radical, NO acts as a unique biological signal molecule, impacting a variety of physiological and pathological processes [

12,

13].

In the reproductive system, NO is necessary for follicular development, oocyte maturation, ovulation, and embryo implantation[

14]. In men, it has an effect on spermatogenesis and sperm capacitation[

15]. However, with obesity, increasing oxidative stress depletes the necessary cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), causing eNOS”uncoupling,” resulting in the formation of superoxide (O2-) rather than NO [

16]. This shift produces damaging oxidative byproducts such as peroxynitrite (ONOO-), which causes cellular damage and reduces NO bioavailability[

17].

Elevated NO2 (nitrite) and NO3 (nitrate) levels indicate abnormal NO metabolism and decreased vascular function, affecting blood flow and cellular communication in the ovaries and uterus [

18]. These molecular alterations have a negative impact on folliculogenesis, oocyte quality, and embryo implantation, and are associated with disorders such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), which contributes to infertility [

19].Bariatric surgery increases NO bioavailability by lowering oxidative stress and restoring eNOS activity, with benefits for vascular health and reproductive outcomes.

The present study investigates the relationship between obesity, oxidative stress and infertility through the expression of CART, Leptin and eNOS genes focusing on the therapeutic potential of bariatric surgery in restoring reproductive health.

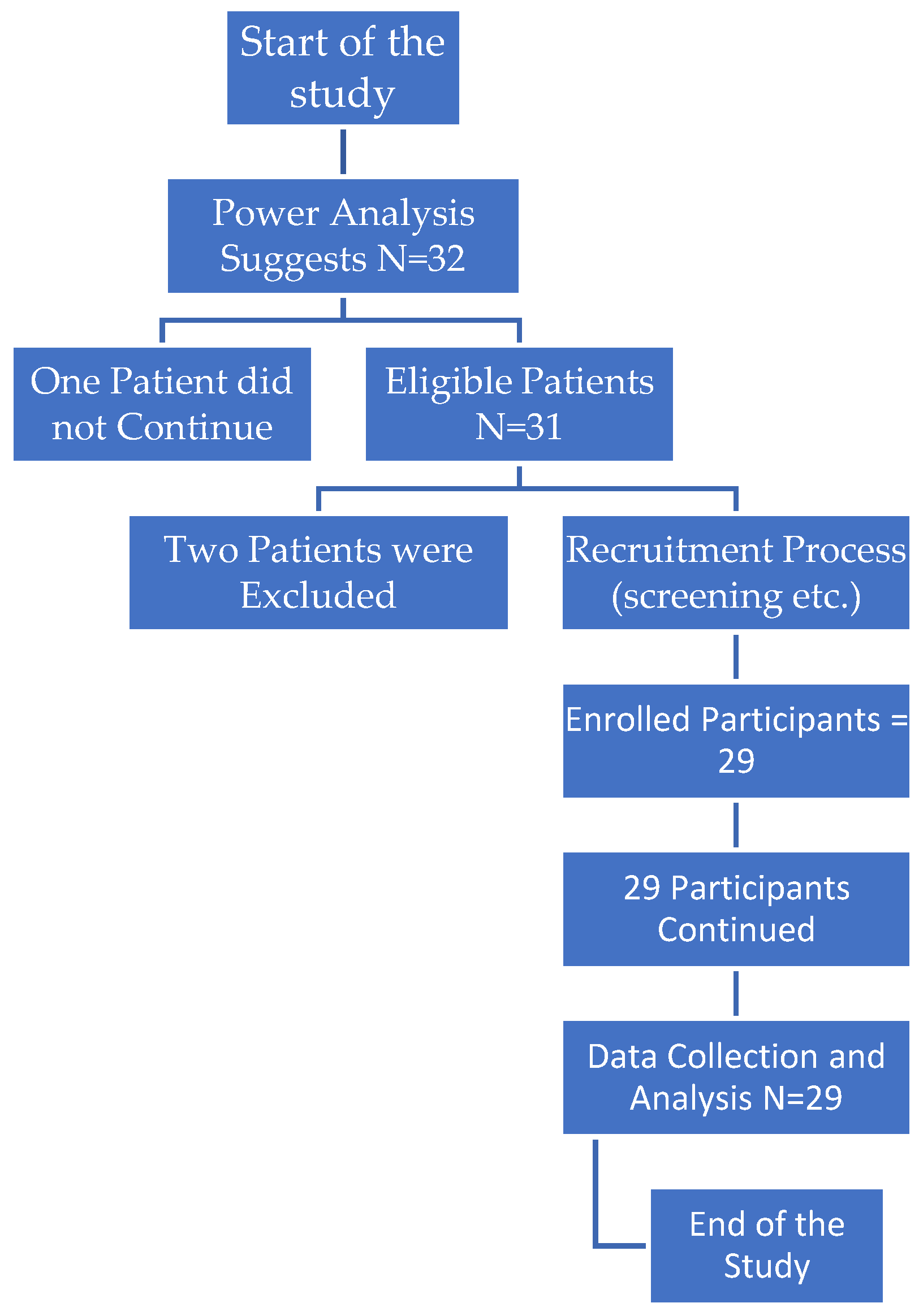

5. Results

Table 1 shows acorrelation analysis between eNOS and several clinical indicators was examined prior to bariatric surgery. Mean age was 33.03 years (SD = 4.08), with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.111 (p = 0.565). For hormonal parameters, FSH had a mean of 6.03 mIU/mL (SD = 1.09) and a correlation of 0.188 (p = 0.328), whereas LH had a mean of 6.87 mIU/mL (SD = 1.01) and an insignificant correlation of 0 (p = 0.997). Estradiol (E2) levels averaged 30.75 pg/mL (SD = 3.80), with a minor correlation of 0.249 (p = 0.193), whereas SHBG levels averaged 36.24 nmol/L (SD = 7.58), with a slight negative correlation of -0.076 (p = 0.696).Free testosterone exhibited the greatest variability (mean = 28.72 ng/dL, SD = 9.35) and a slight positive correlation of 0.285 (p = 0.133). AMH levels averaged 2.14 ng/mL (SD = 0.24), with a correlation coefficient of 0.115 (p = 0.552). For ovarian reserve markers, AFC in the right ovary (mean = 10.31, SD = 2.51) and left ovary (mean = 9.28, SD = 2.59) had associations of 0.095 (p = 0.623) and 0.063 (p = 0.746), respectively. Finally, the mean BMI before surgery was 41.12 (SD = 3.28), with a negative correlation of -0.266 (p = 0.162). Overall, none of these relationships was statistically significant (all p > 0.05), indicating that eNOS gene expression is not linearly linked with these clinical indicators prior to bariatric surgery.

Table 2 indicates the association of eNOS gene expression and several clinical indicators following bariatric surgery. The mean AFC in the left ovary after surgery was 6.76 (SD = 1.24), with a Pearson correlation of -0.149 (p = 0.439), and in the right ovary, 7.38 (SD = 1.64), with a correlation of 0.037 (p = 0.849). AMH levels after surgery averaged 2.96 ng/mL (SD = 0.15), with a correlation coefficient of 0.102 (p = 0.597). Six months after surgery, BMI averaged 25.98 (SD = 1.38) with a negative correlation of -0.248 (p = 0.194).Estradiol (E2) levels averaged 49.23 pg/mL (SD = 4.54) with a correlation of -0.156 (p = 0.42), whereas FSH levels post-surgery averaged 8.88 mIU/mL (SD = 0.08) with a weak correlation of 0.08 (p = 0.677). Free testosterone levels averaged 9.42 ng/dL (SD = 2.52) and showed a weak negative correlation of -0.151 (p = 0.436). LH levels after surgery averaged 8.83 mIU/mL (SD = 1.03), with a -0.121 correlation (p = 0.532). SHBG had the strongest connection (-0.365, p = 0.049), demonstrating a small but statistically significant negative link with Cpt eNOS. Overall, only SHBG shows a possible association with gene expression post surgery.

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics and the correlation analysis of gene expression parameters prior to surgery. The mean expression of eNOS was -4.85 (SD = 1.75), with values ranging from -7.52 to -0.23, whereas CART had a mean of 0.27 (SD = 4.43) and ranged from -4.1 to 10.72, indicating greater variability. Leptin had a mean of -1.87 (SD = 1.75) with a range of -5.5 to 1.09.

Regarding

Table 4, the connection between eNOS and CART (r = 0.038, p = 0.848), indicate no significant link. Similarly, the connection between Cpt eNOS A and Cpt0 Leptin was negative and modest (r = -0.301), but not statistically significant (p = 0.12).The correlation between Cpt0 CART and Cpt0 Leptin was equally minimal (r = 0.077, p = 0.697). Overall, none of the relationships were statistically significant (all p-values more than 0.05), indicating that these gene expressions are not linearly related prior to surgery.

Following surgery in

Table 5, descriptive statistics and correlation analysis of gene expression characteristics reveal modest relationships between Cpt1eNOS, Cpt1 CART, and Cpt1 Leptin. The average expression of Cpt1eNOS was 1.18 (SD = 2.31), with values ranging from -2.07 to 6.77. Cpt1 CART had a mean of -3.4 (SD = 1.12) and ranged from -5.78 to -0.74, whereas Cpt1 Leptin had a mean of -0.07 (SD = 1.55) and ranged from -3.34 to 2.64.

Table 6 indicates the relationship between eNOS and CART was minimal (r = 0.16) and not statistically significant (p = 0.40), indicating no relevant relationship. Similarly, the correlation between Cpt1eNOS and Cpt1 Leptin was modest (r = 0.039) and had a high p-value (p = 0.838), indicating no meaningful relationship. Cpt1 CART and Cpt1 Leptin showed a weak positive connection (r = 0.282), however it was not statistically significant (p = 0.136). Overall, none of the correlations were statistically significant (all p-values > 0.05), indicating that there are no substantial linear connections between these gene expressions following surgery.

Table 7 summarizes the changes in gene expression for CART, Leptin, and eNOS before and after bariatric surgery, including mean values, standard deviations, correlations, and statistical significance. The mean expression of CART fell considerably from 0.273 (SD = 4.43) before surgery to -3.42 (SD = 1.14) after surgery, with a t-statistic of 4.52 and a highly significant p-value of < 0.001. Leptin expression decreased significantly from -1.87 (SD = 1.75) before surgery to -0.130 (SD = 1.55) after surgery, with a t-statistic of -7.35 and a p-value of < 0.001.Following surgery, eNOS expression increased from a mean of -4.87 (SD = 1.7) to 1.18 (SD = 2.31), with a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.529) and a statistically significant p-value (p = 0.003), indicating a substantial relationship in expression changes before and after surgery.

6. Discussion

Obesity treatment options include both nonsurgical and surgical procedures. Among surgical techniques, bariatric surgery stands out for its ability to improve metabolic health, lower cardiovascular risks, and resolve obesity-induced infertility[

20,

21,

22]. This study focused on sleeve gastrectomy, a bariatric surgical technique that involves removing a major section of the stomach, leaving behind a smaller, tube-shaped stomach. This modification not only limits food intake, but it also causes hormonal changes that play an important role in hunger, metabolism, and energy balance. Sleeve gastrectomy has been found to contribute to significant weight loss and metabolic benefits by reducing the synthesis of hunger-stimulating hormones such as ghrelin and increasing the release of satiety-related hormones, making it a common treatment for obesity and associated comorbidities[

23,

24].Despite advances in ART, the impact of obesity on IVF outcomeremains a major source of concern.

Nitric oxide (NO) is involved in several reproductive processes in female animals, including follicular development, ovulation, oocyte maturation, and luteal function[

14]. The enzyme nitric oxide synthase (NOS) produces NO, and its expression in ovarian follicles varies by species and stage of development[

25].

This study focused on the connection between BMI changes after bariatric surgery, with hormone profiles, and genetic features in infertile women. Our findings showed considerable changes in gene expression following surgery, as well as poor correlations between gene expression and clinical findings.

Prior to surgery, correlation analysis of eNOS gene expression and clinical parameters revealed no statistically significant linear associations, as evidenced by non-significant p-values for all clinical variables, including age, BMI, and hormonal levels such as FSH, LH, and estradiol. This lack of association implies that, prior to surgical intervention, eNOS expression may function independently of these clinical parameters.After surgery, the correlation analysis of eNOS gene expression with clinical measurements revealed a similar trend, with the majority of associations being non-significant. However, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), had a statistically significant negative connection with eNOS expression (r = -0.365, p = 0.049) showing that the corresponding protein may be associated with hormonal regulatory mechanisms involving SHBG following metabolic changes caused by bariatric surgery. Consequently,more research onto how SHBG and eNOS interactions affect the hormonal milieu following surgery could be of major interest.

Further analysis of gene expression levels of eNOS , CART, and Leptin prior to surgery revealed no significant relationships, with all p-values greater than 0.05 suggesting that the corresponding proteins may function independently.A similar trend emerged in the post-surgery correlations of the studied genes, with no significant linear associations. The lack of significant post-surgical connections among these genes shows that, while each of them may respond to physiological changes following bariatric surgery, there are no strong interdependencies in their expression patterns.

Conversely, eNOS expression increased significantly after surgery, from a mean of -4.87 (SD = 1.7) to 1.18 (SD = 2.31), with a moderate positive correlation between pre- and post-surgery levels (r = 0.529, p = 0.003). This rise in eNOS expression may indicate an improvement in endothelial function following surgery, which could be connected to improved vascular health and metabolic regulation. The increase of eNOS is noteworthy because it indicates a favorable adaptation in response to the lowered oxidative stress and inflammation that are commonly associated with obesity.The most surprising findings were from comparing CART, Leptin, and eNOS gene expression levels before and after surgery. Bariatric surgery significantly reduced the expression of CART and Leptin, with t-statistics of 4.52 and -7.35, respectively, and very significant p-values (both < 0.001). This significant drop shows that bariatric surgery may inhibit pathways involving CART and Leptin, most likely due to the significant changes in metabolic and inflammatory states associated with weight loss. Given that CART regulates hunger and Leptin regulates energy homeostasis, the observed decreases may be a response to the lower caloric intake and changed energy balance following surgery.

Adipose tissue is no longer thought of as a passive storage location for free fatty acids (FFA), but rather as a dynamic endocrine organ that secretes a variety of mediators known as adipokines. These proteins include TNF-α, resistin, IL-6, ASP, AGT, PAI-1, leptin, and adiponectin. They are involved in several metabolic processes, including energy balance, food intake, fat metabolism, vascular tone modulation, and insulin sensitivity [

26,

27]. Although leptin and adiponectin help regulate energy and metabolism, other variables such as TNF-α, IL-6, and resistin can worsen insulin resistance. Angiotensinogen and PAI-1 are linked to vascular problems associated with obesity [

28].

Leptin, a 16-kDa hormone largely generated in adipose tissue, is critical in hunger control. Obesity has been associated to mutations in the leptin and leptin receptor genes [

28,

29]. In obesity, oxidative stress can be caused by a variety of factors, including hyperglycemia, hyperleptinemia, insufficient antioxidant defenses, increased lipid levels in muscle, increased muscle activity, elevated free radical production rates, mitochondrial dysfunction, endothelial impairment, and chronic inflammation[

30,

31].

CART expression is important in morbid obesity and is closely linked to hormonal pathways, as evidenced by animal research. Asnicar et al. studied CART-deficient mice and discovered that they were more prone to obesity when fed a high-fat diet [

23]. Similarly, Lee et al. found that injecting CART into the nucleus tractus solitarii reduced food consumption in obese rats [

32]. Kristensen et al. demonstrated that CART peptides inhibited feeding behavior even in the presence of neuropeptide Y (NPY), a powerful appetite stimulant in the central nervous system[

10].Furthermore, Okumura et al. and Asakawa et al. found that CART injection into the fourth ventricle delayed stomach emptying, similar to the effects of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and cholecystokinin [

33,

34]. Patkar et al. investigated the link between bariatric surgery and CART expression in a mouse model of morbid obesity. Mice were separated into four groups based on the intervention: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), sleeve gastrectomy, calorie restriction, and a control group receiving no intervention. The study found no statistically significant differences in CART mRNA expression among the groups. Furthermore, the findings indicated that RYGB had distinct effects on hypothalamic gene regulation in comparison to calorie restriction or weight loss alone [

35].Grayson et al. and Cavin et al. found no significant changes in CART expression following bariatric surgery in obese rats, which supports these findings [

36,

37]. Patkar et al. confirmed these findings, revealing no quantifiable changes in CART levels before and after RYGB, nor any variations in CART mRNA expression between chow-fed and RYGB-treated mice [

35]. Muñoz-Rodríguez et al. found that obese patients had higher CART levels before bariatric surgery than those with normal weight, but there was no significant difference one year later [

38]. In their 2021 assessment, Singh et al. suggested that the CART peptide has potential as a treatment agent for morbid obesity [

39].

In cattle, eNOS is present in granulosa cells at all stages of follicular development[

40].In porcine, eNOS is expressed in big follicles (7-10 mm), but not in medium-sized follicles (3-6 mm)[

41]. These findings highlight the species-specific expression patterns of NOS and point to a distinct functional role of NO in ovarian physiology.

NO also regulates the growth and development of preantral follicles. NO levels vary throughout follicular development, indicating that it influences follicular expansion and atresia [

42]. In preantral follicle investigations, enhanced eNOS expression was detected in response to gonadotropins such as human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), emphasizing its role in follicular development and differentiation [

43,

44]. The dual role of NO in follicular development may be due to its vasodilatory impact, which influences follicular blood flow and nutrientdelivery[

45].

Experiments involving mice treated with NOS inhibitors or eNOS mutant animals demonstrate that NO plays a function in oocyte maturation [

46]. These oocyte meiosis defects indicate that the cumulus-oocyte complex development is dependent on the NO/NOS system [

47]. Furthermore, NO has a concentration-dependent effect, with low levels encouraging oocyte maturation and high levels inhibiting it via decreasing estradiol (E2) production [

48]. This underscores the need of precisely regulating NO levels in order to ensure optimum oocyte maturation.

During ovulation, NO is involved in vascular remodeling and follicular rupture. Non-specific NOS inhibitors, such as aminoguanidine (AG) and L-NAME, have been demonstrated in studies to drastically lower ovulation rates, which may be reversed by NO donors such sodium nitroprusside (SNP) [

49]. The control of NO during ovulation involves complicated hormonal interactions, such as increasing luteinizing hormone (LH) production to stimulate preovulatory processes [

50]. Furthermore, NO has been demonstrated to influence the synthesis of E2, which governs ovulation and follicular development.

NO also regulates follicular atresia by inhibiting granulosa cell death. It has been shown that iNOS-derived NO inhibits apoptosis in rat granulosa cells via autocrine and paracrine signaling, preventing early follicular atresia [

40,

51]. High NO levels, on the other hand, can induce apoptosis in well-differentiated granulosa cells, demonstrating a dual regulatory role dependent on concentration and follicular stage [

52]. NO regulates apoptosis through mechanisms such as the Fas/FasL system and the modulation of pro- and anti-apoptotic gene expression[

53].

In fertilization, NO regulates oocyte activation by affecting intracellular calcium (Ca2+) signaling and sperm capacitation [

54]. NO’s role in these activities is critical for proper fertilization and early embryo development. Furthermore, NO regulates embryo implantation and pregnancy maintenance by creating a favorable uterine environment, as well as modulating uterine contractility and placental blood flow [

55,

56]. NO also helps to maintain vascular resistance and promote nutrient exchange, both of which are necessary for fetal growth and development [

57].

Although an association between eNOS, CART and Leptin are not established, they should be considered as putative biomarkers for fertility outcome in obese women. Additionally it could be of great interest, to further examine a possible parallel action of miRNAs, regulating the expression of the aforementioned genes. Both regulation of oxidative stress and of metabolic disorders through the creation of a related to them genetic profile may be of great value to fertility reestablishment after bariatric surgery.