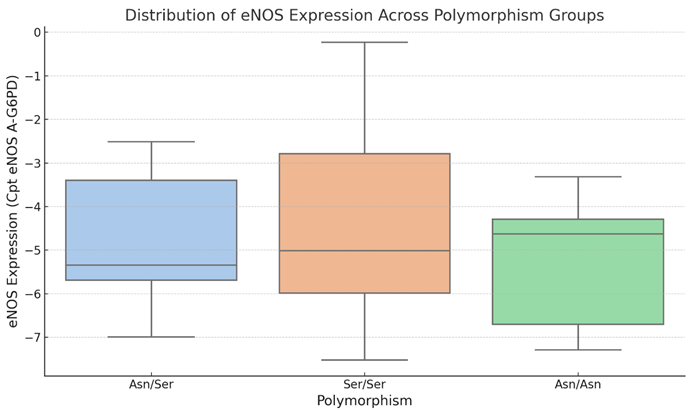

The boxplot 2 shows the distribution of eNOS gene expression (Cpt eNOS A-G6PD) for each FSHR polymorphism group (Asn/Asn, Asn/Ser, and Ser/Ser). The boxes reflect the interquartile range (IQR), the horizontal line within each box denotes the median, and the whiskers reach the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the IQR. Outliers outside of this range are not found in this dataset.

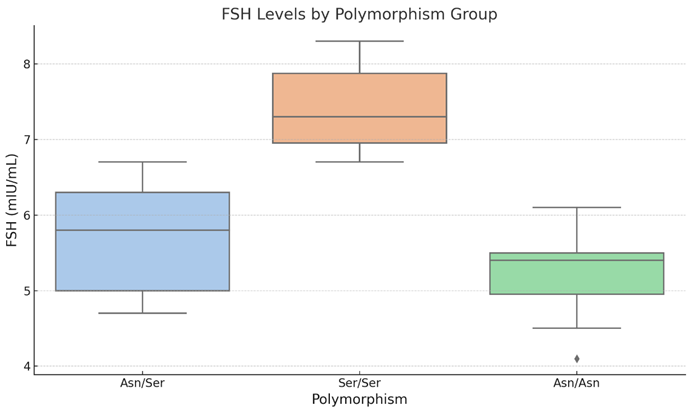

The boxplot 2 compares the amounts of eNOS expression among the three FSHR polymorphism groups. The Asn/Ser group has slightly more variability in eNOS expression, whereas the Asn/Asn group has a smaller range. The Ser/Ser group has a wider range of eNOS expression than Asn/Asn, although the median values for all groups are relatively similar. The overlapping interquartile ranges and lack of clear distinction in median values are consistent with the statistical findings, which demonstrate no significant differences in eNOS expression between the groups (p > 0.05). This shows that the FSHR polymorphism has no substantial impact on eNOS gene expression in this sample.

Post Surgery

Table 6 Post-Surgery Hormonal Parameters, Ovarian Reserve Markers, and BMI Across FSHR Polymorphism Groups.

The post-surgical research revealed significant differences in hormonal parameters, ovarian reserve indicators, and BMI across the three FSHR polymorphism groups. The Ser/Ser group had the highest mean FSH levels (9.45 ± 0.87) compared to the Asn/Asn (8.95 ± 0.79) and Asn/Ser groups (8.47 ± 0.61). LH levels were highest in the Ser/Ser group (9.28 ± 0.72) and lowest in the Asn/Ser group (8.28 ± 0.83).

The Asn/Ser group has the greatest mean E2 levels (50.23 ± 4.79), whereas the Asn/Asn group has the lowest (46.95 ± 4.07). SHBG levels are significantly greater in the Asn/Asn group (69.73 ± 11.59) than in the Ser/Ser group (58.83 ± 9.04), indicating probable differences in androgen metabolism or binding capacity between polymorphism groups. Free testosterone levels are highest in the Ser/Ser group (10.81± 3.25) and lowest in the Asn/Ser group (8.49 ± 1.62).

AMH levels in ovarian reserve markers vary little between groups, with averages ranging from 2.90 to 2.98. AFC values for both right and left ovaries are comparable, with slightly higher values in the Asn/Asn group for the right ovary (7.75 ± 1.75) and the Ser/Ser group for the left ovary (6.80 ± 1.24).

BMI varies slightly between polymorphism groups, with averages ranging from 25.72 ± 1.42 in the Asn/Ser group to 26.38 ± 1.29 in the Asn/Asn group. These findings indicate that, while certain hormones such as FSH, LH, and SHBG show significant fluctuations, other measures such as AMH, AFC, and BMI stay largely steady between polymorphism groups. More research may be required to investigate the clinical consequences of these hormones and metabolic variations

Table 7 presents the ANOVA results that compare hormonal parameters and ovarian reserve indicators among FSHR polymorphism groups (Asn/Asn, Asn/Ser, and Ser/Ser) after surgery. The columns provide the parameter examined, the F-statistic, and the related p-value. A p-value < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences between polymorphism groups.

Following surgery, in

Table 7, the research indicates significant differences in FSH and LH levels among the FSHR polymorphism groups. FSH levels exhibited the highest correlation (F-statistic = 4.27, p = 0.0249), followed by LH levels (F-statistic = 4.01, p = 0.0302), implying that genetic differences in FSHR may influence these hormone levels after surgery. However, no significant differences were found for estradiol (E2), sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), or free testosterone (p-values of 0.252, 0.219, and 0.120, respectively). These findings suggest that, whereas FSHR polymorphisms have a measurable effect on FSH and LH regulation, their impact on other hormonal and metabolic parameters after surgery is limited. Further research could look into the therapeutic significance of these variances in terms of ovarian function and recovery after surgery.

Table 8: Relationship investigation of Cpt eNOS and other clinical indicators following bariatric surgery. The table shows the mean values, standard deviations, Pearson correlation coefficients, and p-values for each parameter.

Table 8 shows the relationship between eNOS gene expression and many clinical markers following bariatric surgery. Following surgery, the mean AFC in the left ovary was 6.76 (SD = 1.24), with a Pearson correlation of -0.149 (p = 0.439), and in the right ovary, 7.38 (SD = 1.64), with a correlation of 0.037 (p = 0.849). Following surgery, AMH levels averaged 2.96 ng/mL (SD = 0.15), with a correlation value of 0.102 (p = 0.597). Six months following surgery, the average BMI was 25.98 (SD = 1.38), with a -0.248 correlation (p = 0.194). Estradiol (E2) levels averaged 49.23 pg/mL (SD = 4.54) with a correlation of -0.156 (p = 0.42), but FSH levels after surgery averaged 8.88 mIU/mL (SD = 0.08) with a weak correlation of 0.08 (p = 0.677). Free testosterone levels were 9.42 ng/dL (SD = 2.52), with a weak negative correlation of -0.151 (p = 0.436). LH levels after surgery averaged 8.83 mIU/mL (SD = 1.03), with a correlation of -0.121 (p = 0.532). SHBG had the strongest association (-0.365, p = 0.049), indicating a minor but statistically significant negative correlation with Cpt eNOS. Overall, only SHBG appears to be associated with gene expression after surgery.

Table 9 shows pairwise comparisons of mean differences (meandiff) in FSH levels following surgery among FSHR polymorphism groups (Asn/Asn, Asn/Ser, Ser/Ser), as well as adjusted p-values (p-adj). A p-adj < 0.05 shows a statistically significant difference among groups.

Table 9 shows pairwise comparisons show that FSH levels differ significantly between the Asn/Ser and Ser/Ser groups (mean difference = 0.9731, p-adj = 0.0197). However, tests between Asn/Asn and Asn/Ser (-0.4731, p-adj = 0.3498) and Asn/Asn and Ser/Ser (0.5000, p-adj = 0.3861) revealed no statistically significant differences. These findings indicate that the Ser/Ser polymorphism may be associated with higher FSH levels after surgery than the Asn/Ser group, although differences between the Asn/Asn groups are not significant.

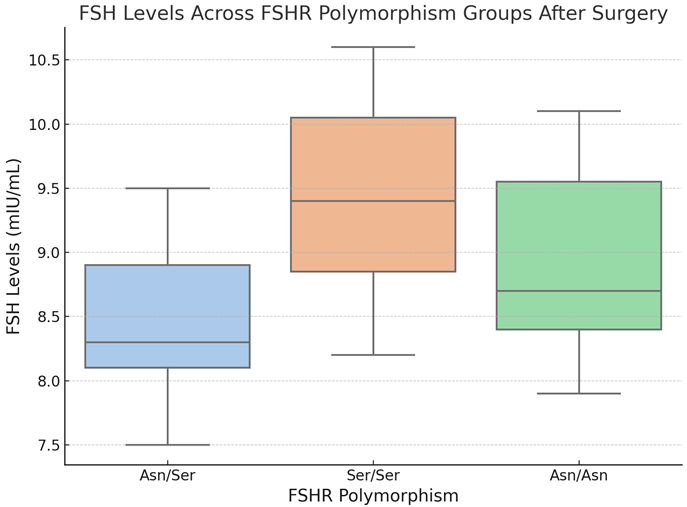

Boxplot 3. FSH Levels Across FSHR Polymorphism Groups After Surgery.

The boxplot 3 depicts the distribution of FSH levels (mIU/mL) following surgery across the FSHR polymorphism groups (Asn/Asn, Asn/Ser, and Ser/Ser). The box represents the interquartile range (IQR), the line within the box denotes the median, and the whiskers extend 1.5 times the IQR. Outliers are represented as isolated points beyond the whiskers.

The visualization, boxplot 3, shows how FSH levels vary between the three polymorphism groups. The Ser/Ser group has the highest median and a wider range of FSH levels than the Asn/Ser and Asn/Asn groups. The Asn/Ser group has the lowest median and narrowest range. This supports the pairwise comparison results that show substantial variations in FSH levels between the Ser/Ser and Asn/Ser groups (p-adj < 0.05). These findings imply that FSH levels after surgery are regulated by the FSHR polymorphism, with the Ser/Ser variant related with greater FSH levels.

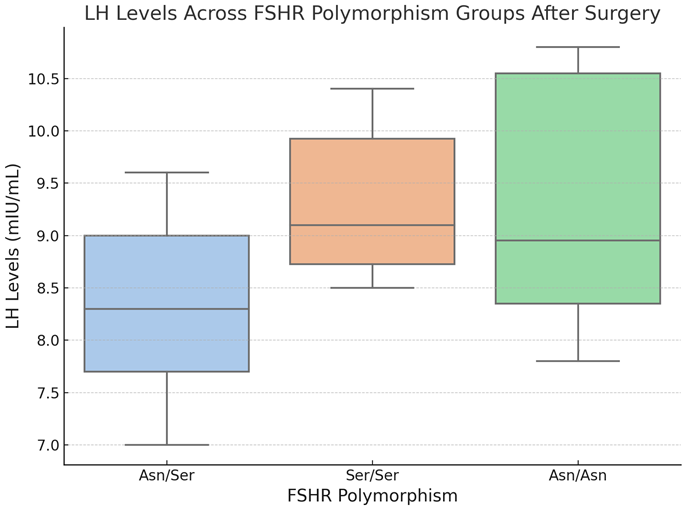

Boxplot 4. LH Levels Across FSHR Polymorphism Groups After Surgery.

The boxplot 4 depicts the distribution of luteinizing hormone (LH) levels (mIU/mL) following surgery among FSHR polymorphism groups (Asn/Asn, Asn/Ser, and Ser/Ser). The central line in each box reflects the median LH level, while the box margins denote the interquartile range (IQR). Whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the IQR; any points outside of this range are considered outliers.

The visualization shows post-surgery patterns in LH levels among the three FSHR polymorphism groups. The Asn/Ser group had the lowest median LH levels, with a very narrow range compared to the other groups. The Ser/Ser group has somewhat higher median LH levels and a comparable range to the Asn/Ser group, whereas the Asn/Asn group has the most variability in LH levels, with a larger interquartile range. Despite these findings, statistical analysis revealed no significant pairwise differences in LH levels across the groups (all p-adj > 0.05). These findings indicate that, while minor differences in LH levels may exist, FSHR polymorphisms may not have a major effect on LH levels after surgery. Further research could determine whether these changes are clinically relevant in specific subgroups.

The

Table 10 compares pairwise mean differences (meandiff) in LH levels (mIU/mL) between FSHR polymorphism groups (Asn/Asn, Asn/Ser, and Ser/Ser) following surgery. The table also contains adjusted p-values (p-adj) and 95% confidence interval lower and upper boundaries for each comparison. A p-value of < 0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference.

The pairwise comparisons in

Table 10 show patterns in LH levels among the FSHR polymorphism groups, however none are statistically significant. The comparison of Asn/Asn and Asn/Ser revealed a mean difference of -0.9779 (p-adj = 0.07), indicating that the Asn/Ser group may have lower LH levels than the Asn/Asn group. Similarly, the difference between Asn/Ser and Ser/Ser (mean difference = 1.0029, p-adj = 0.0619) approached significant, showing that Ser/Ser had somewhat higher LH levels than Asn/Ser. In contrast, the comparison of Asn/Asn and Ser/Ser indicated minimal variations in LH levels (mean difference = 25, p-adj = 0.9984), indicating no significant difference between these groups. Overall, these results imply that the FSHR polymorphism has only a marginal effect on LH levels following surgery, with no statistically significant changes observed in this cohort. Further studies with larger sample sizes may help clarify these trends.

The

Table 11 compares the mean differences (meandiff) in eNOS expression levels between the FSHR polymorphism groups (Asn/Asn, Asn/Ser, and Ser/Ser) following surgery. The table shows adjusted p-values (p-adj), 95% confidence interval lower and upper bounds, and whether the difference is statistically significant (reject). A p-value of <0.05 shows statistical significance.

Pairwise assessments in

Table 11 of eNOS expression among FSHR polymorphism groups after surgery indicated no statistically significant differences. The comparison of Asn/Asn and Asn/Ser revealed a mean difference of 0.3898 (p-adj = 0.9255), with the confidence interval ranging from -2.1917 to 2.9713. Similarly, the mean difference between Asn/Asn and Ser/Ser was 1.5950 (p-adj = 0.3658), which was not statistically significant. The difference between Asn/Ser and Ser/Ser was somewhat less (mean difference = 1.2052, p-adj = 0.4869), with no statistical significance found. These findings imply that the FSHR polymorphism has no substantial affect on eNOS expression levels after surgery. Additional research with a bigger cohort could help elucidate these tendencies and investigate potential biological ramifications.

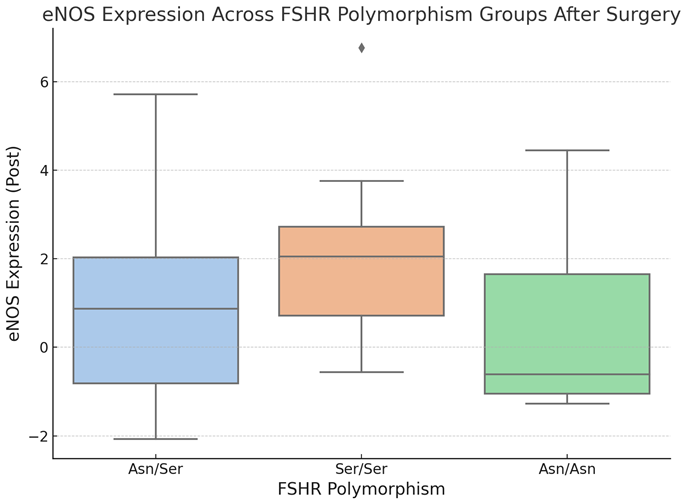

Boxplot 5. eNOS Expression Across FSHR Polymorphism Groups After Surgery.

The boxplot 5 depicts the distribution of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression levels among FSHR polymorphism groups (Asn/Asn, Asn/Ser, Ser/Ser) following surgery. The central line in each box reflects the median eNOS expression, whereas the box margins denote the interquartile range (IQR). Whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the IQR; any points outside of this range are considered outliers.

The graphic, boxplot 5, depicts differences in eNOS expression levels among the FSHR polymorphism groups following surgery. The Ser/Ser group has the greatest median eNOS expression and the widest range, indicating more variability within this group. The Asn/Ser group has a somewhat lower median and a narrower distribution than the Ser/Ser group. In contrast, the Asn/Asn group has the lowest median eNOS expression and a more concentrated distribution.Despite these variations, statistical analysis indicated no significant pairwise differences in eNOS expression levels across polymorphism groups. These data suggest that, whereas eNOS expression varies by group, FSHR polymorphisms may not have a significant impact on its expression after surgery. More study with bigger cohorts is needed to confirm these findings and determine their clinical importance.

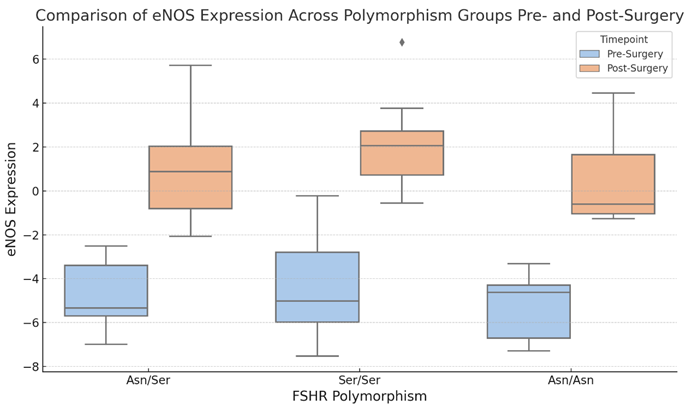

Boxplot 6. Comparison of eNOS Expression Across Polymorphism Groups Pre- and Post-Surgery.

The boxplot 6 compares eNOS expression levels among FSHR polymorphism groups (Asn/Asn, Asn/Ser, Ser/Ser) at two time points: before and after surgery. The central line in each box reflects the median eNOS expression, whereas the box margins denote the interquartile range (IQR). Whiskers extend to the minimum and highest values of 1.5 times the IQR. Pre-surgery data is shown in blue, while post-surgery data is in orange.

The visualization, boxplot 6, shows significant variations in eNOS expression levels among FSHR polymorphism groups from before to after surgery. eNOS expression appeared to rise in all groups following surgery, with the Ser/Ser group exhibiting the greatest range and highest variability. The Asn/Ser group likewise shows a change toward greater eNOS levels after surgery, while the range is less than the other groups. In contrast, the Asn/Asn group exhibits a mild increase in eNOS levels over a slightly larger range. These results show that surgical intervention may modify eNOS expression, with the impact potentially differing depending on the FSHR polymorphism. Further statistical research could provide light on the significance of these changes, as well as their biological implications.

The

Table 12 shows the paired t-test findings comparing eNOS expression levels before and after surgery for each FSHR polymorphism group (Asn/Asn, Asn/Ser, and Ser/Ser). The t-statistic and p-value columns show the size of change, with p-values < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

In the

Table 12 the paired t-test analysis demonstrates substantial changes in eNOS expression levels from pre- to post-surgery for all FSHR polymorphism groups. The Asn/Ser group showed the most significant difference (t-statistic = -10.39, p < 0.000001), followed by the Ser/Ser group (t-statistic = -9.07, p < 0.00005) and the Asn/Asn group (t-statistic = -7.64, p < 0.0002).

The extremely significant p-values (< 0.05) across all groups show that surgical intervention consistently affects eNOS expression, regardless of the individual polymorphism. The negative t-statistics indicate that eNOS expression levels increased after surgery in all polymorphism groups. These findings highlight the potential importance of surgical intervention in regulating eNOS activity, which has consequences for endothelial function and ovarian physiology.